Abstract

Initial biochemical signaling originating from high-affinity immunoglobulin E receptor (FcɛRI) has been ascribed to Src family kinases. To understand the mechanisms by which individual kinases drive the signaling, we conducted reconstitution experiments: FcɛRI signaling in RBL2H3 cells was first suppressed by a membrane-anchored, gain-of-function C-terminal Src kinase and then reconstructed with Src family kinases whose C-terminal negative regulatory sequence was replaced with a c-myc epitope. Those constructs derived from Lyn and Fyn, which are associated with detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs), physically interacted with resting FcɛRI and reconstructed clustering-induced signaling that leads to calcium mobilization and ERK1 and -2 activation. c-Src-derived construct, which was excluded from DRMs, failed to interact with FcɛRI and to restore the signaling, whereas creation of palmitoylatable Cys3 enabled it to interact with DRMs and with FcɛRI and to restore the signaling. Deletion of Src homology 3 (SH3) domain from the Lyn-derived construct did not alter its ability to transduce the series of signaling. Deletion of SH2 domain did not affect its association with DRMs and with FcɛRI nor clustering-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of FcɛRI β and γ subunits, but it almost abrogated the next step of tyrosine phosphorylation of Syk and its recruitment to FcɛRI. These findings suggest that Lyn and Fyn could, but c-Src could not, drive FcɛRI signaling and that N-terminal palmitoylation and SH2 domain are required in sequence for the initial interaction with FcɛRI and for the signal progression to the molecular assembly.

Stimulation of Fc receptors and T-cell and B-cell antigen receptors induces a rapid increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular proteins. This biochemical signaling plays crucial roles in inflammatory functions, including phagocytosis, cytokine synthesis, and inflammatory mediator release (4, 6, 17, 59, 74, 84). The majority of Fc receptors, together with T-cell and B-cell antigen receptors, have hetero-oligomeric structures: they are composed of ligand-binding subunits and associating signal transduction subunits (17, 35, 59, 74). The high-affinity immunoglobulin E (IgE) receptor (FcɛRI) has a tetrameric structure composed of an IgE binding α subunit, a β subunit, and a disulfide-bonded γ dimer (8, 45, 58). Aggregation of IgE is converted to protein tyrosine phosphorylation (71) by the action of the β and γ subunits (4, 6, 17, 36, 57). These signaling modules have not been shown to possess catalytic activity but instead possess tyrosine-based cell activation motifs (ITAM [immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif]) (30, 62, 84). Upon receptor clustering, ITAM tyrosine is rapidly phosphorylated and creates sites for the assembly of SH2 domain-containing proteins, including Syk protein tyrosine kinase (5, 75). Association of Syk with tyrosine phosphorylated γ and subsequent phosphorylation of Syk on activation loop tyrosine further trigger the downstream signaling cascade leading to cell activation (29, 37, 68, 83).

The initial activation step of ITAM tyrosine phosphorylation is ascribed to the action of Src family protein tyrosine kinases. This concept is in part based on the observations that several of Src family members physically associate with Fc receptors under resting conditions and that their kinase activities are rapidly increased after receptor engagement (18, 64, 79, 81, 87). To obtain more confirmative evidence, targeted disruption of single, or multiple Src family genes were conducted (15, 40, 41, 51). Crowley et al. showed that Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis is delayed but well preserved in macrophages derived from Lyn−/− Hck−/− Fgr−/− mice (15). One of our laboratories demonstrated that FcɛRI-induced calcium mobilization and degranulation is preserved in Lyn−/− murine bone marrow-derived mast cells, albeit tyrosine phosphorylation of Syk and Bruton's tyrosine kinase were reduced (51). These findings have provided the important information that Src family kinases possess complementary roles in Fc receptor functions (40), but the functional redundancy itself generates a difficulty in ascertaining the requirement or the specificity of Src family kinases. In addition, wide distribution of FcɛRI in monocytes, eosinophils and Langerhans cells, besides basophils and mast cells (23, 43, 66, 82), raised the possibility that FcɛRI may utilize different set of Src family kinases depending on cell species.

As an alternative approach, C-terminal Src kinase (Csk) (28, 49, 50, 53) has been used as a negative regulator of Src family kinases (11, 12, 27, 73). In hematopoietic cells, Src family kinases are assumed to be in an equilibrium between C-terminal tyrosine-phosphorylated (inactive) and dephosphorylated (partially active) forms (27, 74). The balance is regulated by the opposite actions of Csk and CD45 tyrosine phosphatase (13, 48, 74). When C-terminal tyrosine is phosphorylated by Csk, catalytic activity of Src family kinases are suppressed by an intramolecular interaction between the C-terminal tyrosine-based sequence and the SH2 domain (13, 14). Recently, another intramolecular interaction that negatively regulates kinase activity was found between the SH3 domain and the N-terminal linker segment of the catalytic domain (69, 86). By variously modulating the Csk activity in RBL2H3 cells through the overexpression of Csk, a gain-of-function Csk mutant possessing N-myristoylation signal (mCsk) (13) and a kinase-dead mCsk [mCsk(−)] (27), we previously showed that Src family kinases are upstream regulator of FcɛRI-mediated biochemical signaling (27).

The current study was undertaken to further evaluate the roles of individual Src family kinase and its submolecular structures in early FcɛRI signaling. To this end, we utilized mCsk-overexpressing RBL2H3 cells in which basal Lyn activity and FcɛRI signaling were suppressed. C-terminal tyrosine-deleted Src (termed a-Src) family kinases were reconstituted in the cells. We show herein that (i) FcɛRI signaling is transduced by selective Src family kinases, (ii) palmitoylatable Cys in SH4 domain is required for initial interaction with FcɛRI, and (iii) SH2 domain is required for signal progression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

cDNA construction.

Murine cDNAs for Csk, a membrane-anchored Csk mutant (mCsk) possessing N-terminal myristoylation signal of rat c-Src, and a kinase-dead mCsk [mCsk(−)] were described previously (27, 49, 73). c-Myc epitope-tagged rat c-Src and human p56lyn lacking C-terminal tyrosine (termed a-Src and a-Lyn, respectively), whose corresponding C-terminal amino acids (EPQYQPGENL for c-Src and EGQYQQQP for p56lyn, with the negative regulatory tyrosine indicated in boldface) were replaced with 9E10 c-myc epitope sequence (TSVDEQKLISEEDLN), were described previously (25, 73). C-terminal amino acids of human p59fyn (EPQYQPGENL) were also replaced with the c-myc epitope tag through the same procedures, thus generating a-Fyn. To create deletion mutants of a-Lyn lacking the SH3 (amino acids 68 to 117 of human p56lyn) or SH2 (amino acids 130 to 222 of human p56lyn) domains (termed ΔSH3 a-Lyn and ΔSH2 a-Lyn, respectively), a pair of AatII sites and EcoRI sites flanking SH3 and SH2 domains of a-Lyn, respectively, were introduced by PCR-based techniques using QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). The mutagenesis primers used for SH3 deletion were 5′-GGA-ACA-AGG-AGA-CGT-CGT-GGT-AGC-CTT-GTA-C-3′ and 5′-CAT-CCC-CAG-CAA-CGA-CGT-CGC-CAA-ACT-CAA-C-3′ encompass ing nucleotides 186 to 216 and 336 to 366 of human p56lyn coding region, respectively. Those for SH2 deletion were 5′-CAC-CTT-AGA-AAC-AGA-AGA-ATT-CTT-TTT-CAA-GGA-TAT-AAC-C-3′ and 5′-GAT-GGC-TTG- TGC-AGA-GAA-TTC-GAG-AAG-GCT-TG-3′ encompassing nucleotides 366 to 405 and 646 to 677 of human p56lyn coding region, respectively. The resultant cDNAs were digested with AatII or EcoRI and then self-ligated. Ser3 to Cys mutation in a-Src (a-Src S3C) was introduced through the same procedures, by using a mismatch primer (5′-CCA-GGA-CCA-TGG-GCT-GCA-ACA-AGA-GCA-AGC-CC-3′). a-Fyn, ΔSH3 a-Lyn, ΔSH2 a-Lyn, and a-Src S3C cDNAs without misincorporation of nucleotides were selected and subcloned into an expression vector, pCAGGS (46, 52).

Cells.

RBL2H3 cells and its sublines were cultured as a monolayer in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Nissui, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Equitech-Bio, Ingram, Tex.). RBL2H3 clones stably expressing mCsk, or mCsk(−) cDNA subcloned into neomycin-resistant pCXN2 vector (46, 52) were described previously (27, 73). As a vector control, RBL2H3 clones stably expressing an unrelated cDNA (human PAF receptor [26]) cloned into pCXN2 were also created. RBL2H3 cells overexpressing mCsk were next transfected with a puromycin-resistant vector alone or the vector in combination with a-Lyn, a-Fyn, a-Src, ΔSH3 a-Lyn, ΔSH2 a-Lyn, or a-Src S3C cDNA subcloned into pCAGGS by electroporation, as described elsewhere (73). Clones resistant to puromycin were selected and tested for the expression of the mutated Src family kinases and mCsk by Western blotting with anti-c-myc and anti-Csk polyclonal antibodies. Cells expressing both the molecules were further subcloned by limiting dilution, and independent clones were established for each construct.

Cell stimulation and cell lysis.

Cells at subconfluence in 10-cm dishes were detached by brief trypsinization as described earlier (73) and harvested into DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS. Cells were washed once with DMEM buffered with 10 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.4) and supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (HEPES-DMEM), the cell concentration was adjusted to 107/ml, and the cells were sensitized with 2.5 μg of anti-trinitrophenyl (anti-TNP) mouse monoclonal IgE (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml for 1 h on ice under constant agitation. To remove excess antibody, cells were pelleted, washed once with HEPES-DMEM, and resuspended at 107/ml in the same medium. Then, 0.75 ml of the cell suspension was prewarmed for 5 min at 30°C and stimulated with 100 ng of dinitrophenylated BSA (DNP-BSA) (LSL, Tokyo, Tokyo) per ml for the indicated periods at 30°C. The reaction was terminated by a brief centrifugation (5,000 rpm, 30 s), followed by immediate lysis of the cell pellet with 500 μl of ice-cold Triton X-100 lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 0.5% Triton X-100; 1 mM EDTA; 1 mM vanadate; 20 mM β-glycerophosphate) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (5 μg of leupeptin, 10 μg of pepstatin, and 10 μg of aprotinin per ml and 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The cell lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were subjected to immunoprecipitation.

For in vitro kinase assay of ERK1 and -2 and a-Src kinases, 2 × 106 cells were cultured in 6-cm dishes for 24 h in DMEM containing 10% FCS and then serum starved for another 24 h in HEPES-DMEM. In the case of a-Src kinase assay, cells were lyzed with 500 μl of ice-cold Triton X-100 lysis buffer containing the protease inhibitor cocktail after the serum starvation. In ERK1 and -2 assays, cells were sensitized with 2 ml of 1-μg/ml anti-TNP IgE in HEPES-DMEM for 1 h, washed twice with HEPES-DMEM, and stimulated or not with 100 ng of DNP-BSA per ml in 2 ml of the same medium at 37°C. After 5 min, the medium was aspirated, and the cells were lysed as described above. The cell lysates were centrifuged as described above, and the supernatants were subjected to immunoprecipitation.

Immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting, and in vitro kinase assay.

The supernatants were incubated at 4°C for 1 h with 1 μg of anti-FcɛRI β subunit monoclonal antibody (JRK) (53), 20 μg of anti-Syk (LR) polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, Calif.) directed to linker region of human Syk, 10 μg of anti-ERK1 and -2 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz), or 20 μg of anti-c-myc polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz) and then with 15 μl of 50% protein G-Sepharose slurry (Pharmacia-LKB, Bromma, Sweden) for another 30 min under constant rotation. Then, the beads were washed twice with 500 μl of ice-cold Triton X-100 lysis buffer.

For immunoblotting, beads or 25 μl of total cell lysates were mixed with 25 μl of 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer, and boiled. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and immunoblotting were conducted as described elsewhere (27, 73). For the analysis of β and γ subunits, 10 to 20% gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gels were used and run in SDS Tris-tricine buffer for better resolution of low-molecular-weight proteins. Separated proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Proteins of interest were probed with antiphosphotyrosine monoclonal antibody, 4G10, JRK, anti-c-myc polyclonal antibody, or anti-Syk (N19) polyclonal antibody directed against the amino terminus of human Syk (Santa Cruz). The first antibodies were probed with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase, and signal was detected by the enhanced chemiluminescence method (Amersham). Films were scanned by Epson GT-9600 scanner, and the intensity of the signal was quantified by using NIH Image version 1.62 image analysis system.

For in vitro kinase assay, beads were washed again with kinase buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 10 mM MgCl2; 0.1 mM vanadate; 5 mM β-glycerophosphate; 1 mM dithiothreitol and resuspended in 20 μl of the same buffer. ERK1 and -2 assay was initiated by the addition of 5 μl of substrate solution {125 mM ATP (185 kBq of [γ-32P]ATP), 1.6 μg of Elk-1}, and proceeded at 30°C for 25 min. a-Src kinase autophosphorylation assay was conducted by incubating immunoprecipitates with 5 μl of 125 mM ATP (185 kBq of [γ-32P]ATP) at 30°C for 5 min (27). Reactions were terminated by the addition of 25 μl of 2% SDS sample buffer, samples were boiled and centrifuged, and the supernatant was subjected to SDS-PAGE. 32P incorporation into proteins was visualized and measured by using Fuji image analyzer BAS 2000.

Sucrose density gradient centrifugation.

Protein association with detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs) was analyzed by solubilizing RBL cells with low-concentration Triton X-100 followed by ultracentrifugation of cell lysates on sucrose density gradients according to the methods of Field et al. (19). In brief, 4 × 106/ml cell suspension was solubilized with 0.05% Triton X-100, cell lysate was layered onto 80 to 10% discontinuous sucrose gradients made in Hitachi 13 PA tube (1.5 × 9.6 cm) and centrifuged at 35,000 rpm at 4°C for 18 h (19). Then, 1-ml aliquots of the gradients were collected, proteins were extracted according to the method of Wessel and Flugge (85), and the sample was subjected to immunoblotting as described above.

Staining of cell surface FcɛRI.

To analyze surface expression of FcɛRI, cell suspensions at 106/ml in HEPES-DMEM were sensitized or not (control) with 1.0 μg of anti-TNP IgE per ml for 1 h on ice, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% FCS, and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgE (Southern Biotechnology Associates) in the same buffer for 30 min on ice. After two washes with the buffer, the cells were resuspended in PBS, and surface fluorescence was analyzed by EPIX-XL flow cytometer (Coulter).

Fluorometric imaging of [Ca2+]i.

Measurement of intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) was performed as described previously (27). In brief, cells were cultured on glass coverslips for 24 h and incubated in HEPES-DMEM containing 1 μg of anti-DNP IgE per ml and 5 μM Fura-2 AM (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) for sensitization and Fura-2 loading at 37°C for 1 h. Cells were washed twice with HEPES-Tyrode buffer (25 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.4; 140 mM NaCl; 2.7 mM KCl; 1.8 mM CaCl2; 12 mM NaHCO3; 5.6 mM d-glucose; 0.49 mM MgCl2; 0.37 mM NaH2PO4) containing 0.1% BSA and incubated in the same buffer. Fluorometric images of cells (340 nm/380 nm) were recorded at every 30 s before and after the addition of 100 ng of DNP-BSA per ml under room temperature (20 to 25°C) with an iced charged-coupled device camera-image analysis system (Argus-50; Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). To show time-dependent changes in [Ca2+]i, seven cells in a field were randomly assigned, and the calculated average of [Ca2+]i within the cell area was expressed as line graphs.

RESULTS

Creation of RBL2H3 cell lines expressing mCsk, mCsk(−), or mCsk in combination with epitope-tagged Src family kinase mutants.

In a previous work, we showed that overexpression of mCsk, a gain-of-function Csk mutant possessing a membrane-anchoring signal, profoundly delayed FcɛRI-mediated [Ca2+]i elevation in RBL2H3 cells (27). In the current study, we selected a subclone exhibiting more apparent suppressive phenotypes, in which FcɛRI-mediated calcium mobilization was almost negligible under optimal stimulation conditions (see below and Fig. 2A). The mCsk clone was used as a background in which mutated Src family kinases were coexpressed. Of the Src family kinases, Lyn, Fyn, and c-Src were selected and tested for their abilities to restore FcɛRI signaling downregulated by mCsk. Lyn has been implicated as a major Src family kinase functioning in FcɛRI signaling (4, 18, 65). Fyn was chosen as a molecule distributed in a wide range of hematopoietic cells (13, 48). c-Src is a kinase expressed as abundantly as Lyn in RBL2H3 cells and is presumed to complement Lyn in FcɛRI signaling. In addition, c-Src is structurally different from Lyn and Fyn in that c-Src is devoid of palmitoylatable Cys3 conserved in a majority of Src family kinases (see below) (60, 61). Constructs created on the backbone of the Src family kinases are illustrated in Fig. 1A. a-Src, a-Lyn, and a-Fyn were derived from rat c-Src, human p56lyn, and human p59fyn, respectively. In these constructs, C-terminal 8 to 10 amino acids containing negative regulatory tyrosine were deleted and replaced with a c-myc tag epitope sequence (Fig. 1A).

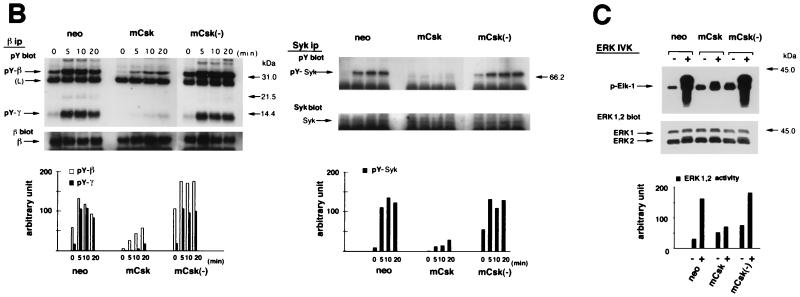

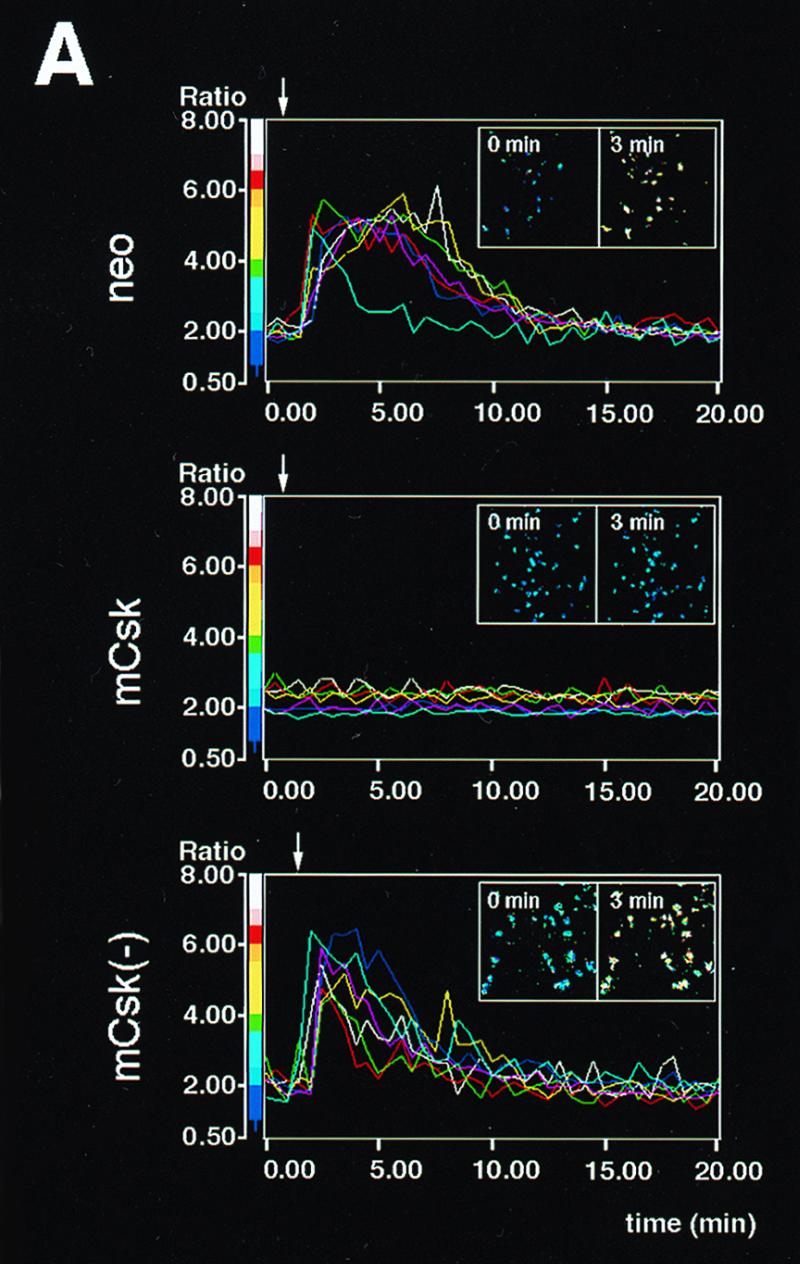

FIG. 2.

Influence of mCsk and mCsk(−) expression on FcɛRI-mediated early signaling. (A) Calcium mobilization in control cells (neo), mCsk-expressing cells (mCsk) and mCsk(−)-expressing cells [mCsk(−)]. Arrows indicate the time of antigen addition. The line graphs represent time courses of changes in [Ca2+]i in seven single cell areas randomly assigned. Insets represent pseudocolor images of [Ca2+]i at 0 min and at 3 min (2 min after antigen addition). Control neo cells rapidly responded to the antigen addition, and the signals subsided within 10 to 20 min. The mCsk subline exhibited almost negligible calcium response. Calcium signaling was preserved in mCsk(−) cells. (B) Time-dependent changes in tyrosine phosphorylation of FcɛRI β and γ subunits (left panel) and in Syk tyrosine phosphorylation (right panel). Cells were stimulated and solubilized at the indicated periods as described in Materials and Methods. In the analysis of β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation (left panel), FcɛRI was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates with anti-β monoclonal antibody (JRK) (denoted as β ip) and subjected to immunoblotting with 4G10 antiphosphotyrosine antibody (pY blot), and the membrane was reprobed with JRK (β blot). Migration positions of tyrosine phosphorylated β (pY-β) and g (pY-γ) subunit and reprobed β subunit (β) are indicated on the left. “(L)” represents the IgG light chain. Molecular mass markers are on the right. Films were scanned, and the intensity of the signal of tyrosine phosphorylated β (pY-β) and γ (pY-γ) were expressed as a bar graph (lower panel). In the control neo cells, pY-β was detectable before FcɛRI clustering and β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation increased, peaked within 5 min of stimulation, and then decreased. In mCsk cells, basal and clustering-induced signals were profoundly suppressed, while these were preserved in mCsk(−) cells. In the analysis of Syk tyrosine phosphorylation (right panel), Syk was immunoprecipitated with anti-Syk antibody (Syk ip), followed by immunoblotting with 4G10 (pY blot). The membrane was reprobed with anti-Syk antibody (Syk blot). Tyrosine-phosphorylated Syk (pY-Syk) and reprobed Syk (Syk) are indicated by arrows on the left. Molecular mass markers are on the right. Intensity of pY-Syk was shown as a bar graph (lower panel). Clustering-induced Syk tyrosine phosphorylation was clearly detectable in neo cells and was markedly suppressed in mCsk cells, whereas it was preserved in mCsk(−) cells. (C) ERK1 and -2 MAP kinase activation in neo, mCsk, and mCsk(−) cells. Cells were sensitized and lysed before (−) and 5 min after (+) FcɛRI clustering. ERK1 and -2 were immunoprecipitated and subjected to in vitro kinase assay (ERK IVK) by using Elk-1 as a substrate. Elk-1 phosphorylation was measured and visualized by using Fuji image analyzer BAS 2000. ERK1 and -2 content in total cell lysates (and mobility shift of ERK2) was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-ERK1 and -2 antibody (ERK1, 2 blot). Positions of phosphorylated Elk-1 (p-Elk-1) and ERK1 and -2 are indicated by arrows on the left. Molecular mass markers are on the right. ERK1 and -2 activity was markedly increased after FcɛRI clustering in neo cells. mCsk expression suppressed it but mCsk(−) did not.

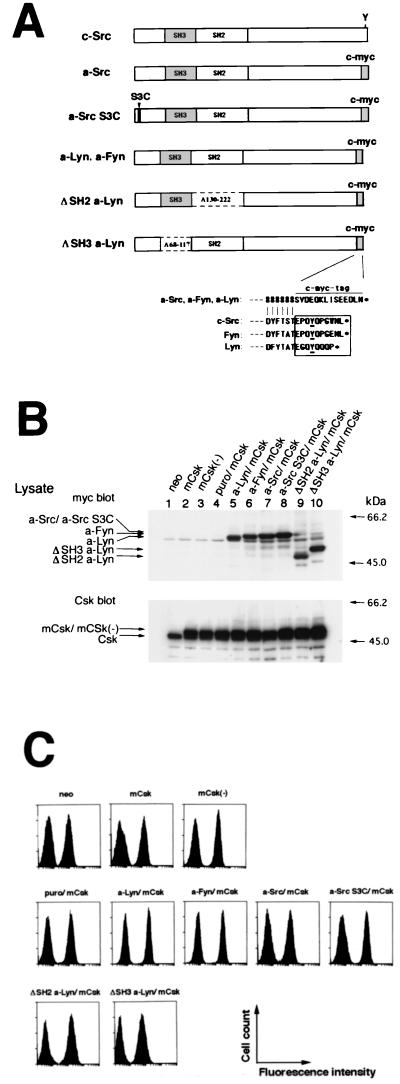

FIG. 1.

Creation of RBL2H3 cells expressing mCsk in combination with Src family kinases whose C-terminal sequences were replaced with a c-myc epitope. (A) Schematic representation of the constructs derived from c-Src, Lyn, and Fyn. To create C-terminal tyrosine-deleted, c-myc-tagged Src family kinases, the conserved 8 to 10 amino acids at the C termini of c-Src, p56lyn, and p59fyn (see boxed amino acids in the sequence alignment) containing negative regulatory tyrosine (underlined) were replaced with the c-myc epitope sequence. “#” indicates the identical amino acid to that of wild-type kinases. The mutated kinases derived from c-Src, p56lyn, and p59fyn were named a-Src, a-Lyn, and a-Fyn, respectively. In a-Src S3C, Ser3 in a-Src was replaced with Cys. ΔSH2 a-Lyn and ΔSH3 a-Lyn were created by deleting the SH2 (amino acids 130 to 222) and SH3 (amino acids 68 to 117) domains from a-Lyn, respectively. (B) Representative immunoblots of cell lines expressing mCsk, mCsk(−), or mCsk in combination with mutated Src family kinases. Cells were lysed with Triton X-100 solubilization buffer as described in Materials and Methods; 10 μg of protein at each lane was then separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblots with anti-c-myc antibody (upper panel) to detect the mutated Src (a-Src) kinases and with anti-Csk antibody (lower panel). Cells expressing Neor control (lane 1), mCsk (lane 2), and a kinase-dead mCsk, mCsk(−) (lane 3) are shown. Cells expressing mCsk with Puror control (lane 4), a-Lyn (lane 5), a-Fyn (lane 6), a-Src (lane 7), a-Src S3C (lane 8), ΔSH2 a-Lyn (lane 9), and ΔSH3 a-Lyn (lane 10) are also shown. Migration positions of the expressed proteins are indicated on the left, and molecular mass markers are given on the right. (C) Analysis of surface expression of FcɛRI in the cell lines. Cells were sensitized or not (control) with mouse IgE and then stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgE. Surface fluorescence was analyzed by EPICS-XL flow cytometer. All of the cell lines exhibited levels of FcɛRI expression almost comparable to that of the neo control.

The first ∼10 amino acids are conserved in Src family kinases (SH4 domain) (60) and contain several fatty acylation sites. Of these, Gly2 responsible for myristoylation is found in all the members, while Cys3, a putative palmitoylation site, was not found in c-Src or Blk. Dual palmitoylation sites in Lck are required to correctly sort Lck to plasma membrane or to more confined functional membrane subdomains, called detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs) or sphingolipid-cholesterol rafts (7, 19, 31, 70). To investigate the roles of palmitoylation, a-Src S3C in which Ser3 of a-Src was changed to Cys was created. SH3 and SH2 domains of Lyn potentially function as docking sites for various signaling molecules (1–3, 34, 55). To examine their roles, a-Lyn lacking SH3 domain (ΔSH3 a-Lyn) or SH2 domain (ΔSH2 a-Lyn) was created. These deletions removed amino acids 68 to 117 and 130 to 222 of p56lyn, respectively.

These constructs were subcloned into an expression vector pCAGGS (46, 52). Prior to creating stable transformants, these plasmids were transiently expressed in Cos7 cells, and the presence of autophosphorylation activity was confirmed by immunoblotting with 4G10 (not shown). The plasmids were then stably transfected into the mCsk clone with the aid of a puromycin-resistant vector, and multiple independent clones were established for each construct. Immunoblots with anti-c-myc or with anti-Csk antibody of representative cell lines expressing mCsk, mCsk(−), or mCsk in combination with the mutated Src family kinases (a-Src kinases) were shown in Fig. 1B. mCsk and mCsk(−) exhibited retarded electrophoretic mobilities compared to intrinsic Csk due to N-terminal additional amino acids (compare lane 1 with lanes 2 and 3). As seen in lanes 5 to 10, almost comparable amounts of a-Src kinases were expressed in mCsk-overexpressing cells, and these kinases were detected at expected migration positions.

Recently D'Oro et al. reported that surface expression of T-cell receptor (TCR) is downregulated by internalization in T cells expressing Lck505F lacking C-terminal tyrosine (16). We thus tested surface expression of FcɛRI and RBL2H3 cells expressing a-Src kinases by flow cytometry. As seen in Fig. 1C, expression of mCsk, mCsk(−), or mCsk in combination with various a-Src kinases did not significantly alter the surface expression of FcɛRI.

Influence of mCsk on FcɛRI-mediated signaling.

Figure 2A shows time-dependent changes in [Ca2+]i. Vector control (neo), mCsk-expressing cells, and mCsk(−)-expressing cells were sensitized with a saturable concentration of anti-TNP IgE (1.0 μg/ml) and stimulated with an optimal concentration of DNP-BSA (100 ng/ml) (27). Control cells and mCsk(−) cells clearly responded to the addition of DNP-BSA. The mCsk-overexpressing clone did not exhibit detectable [Ca2+]i response within a 20-min incubation period.

We next tested time-dependent changes in FcɛRI-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of FcɛRI β and γ subunits and Syk. FcɛRI and Syk were immunoprecipitated with JRK anti-β monoclonal antibody (54) or with anti-Syk antibody, and then immunoprecipitated proteins were subjected to immunoblotting with 4G10 antiphosphotyrosine antibody. The β subunit associates with disulfide-bonded γ subunits via hydrophobic interaction, and JRK antibody is able to coimmunoprecipitate γ subunit under low-detergent conditions (34, 89). As seen in Fig. 2B (β ip), β tyrosine phosphorylation was detectable in control neo cells under resting conditions. Tyrosine phosphorylation of β and γ subunits increased and peaked within 5 min of receptor clustering and gradually declined thereafter. In mCsk cells, tyrosine phosphorylation of resting β subunit was significantly suppressed, and triggering-induced β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation was profoundly decreased and delayed. In the cells expressing mCsk(−), basal β and triggering-induced β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation was well preserved. Clustering-induced Syk tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 2B, Syk ip) was detected within 5 min of stimulation in control neo cells, and it peaked at 10 to 20 min. These signals were profoundly suppressed in mCSk cells, but not in mCsk(−) cells. The potent suppressive effects of mCsk on these upstream biochemical events were consistent with the negligible calcium mobilization in mCsk-overexpressing cells. Activation of ERK1 and -2 mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinases is downstream of Syk and links Fc receptor clustering to eicosanoid release and to tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) synthesis (63, 78). To examine the effects of mCsk on the key intermediate signaling, ERK1 and -2 were immunoprecipitated before and 5 min after FcɛRI clustering and subjected to in vitro kinase assay by using Elk-1 as a substrate (42). As seen in Fig. 2C, receptor clustering resulted in clear increase in the kinase activity in control neo cells. Clustering-dependent upregulation of ERK1 and -2 activity was profoundly suppressed in mCsk cells, while it was preserved in mCsk(−) cells. These observations showed that mCsk downregulated the series of FcɛRI signaling in a kinase-dependent manner. The suppressive effects of mCsk were thus not due to nonspecific effects of overexpression but most likely to negative regulation of Src family kinases via phosphorylation of C-terminal tyrosine.

Differential abilities of a-Src kinases to restore FcɛRI-signaling in mCsk cells.

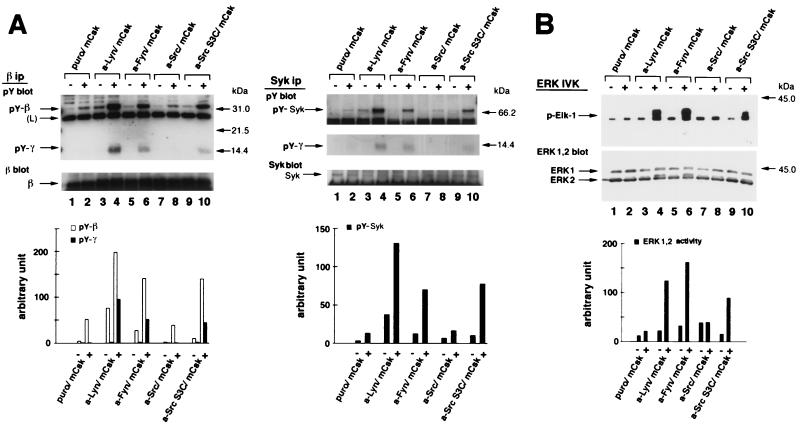

We expressed each of the a-Src kinases in an mCSk background in order to compare their abilities to restore FcɛRI signaling. mCSk cells transfected with vector alone (Puro/mCsk), a-Lyn (a-Lyn/mCsk), a-Fyn (a-Fyn/mCsk), a-Src (a-Src/mCsk), or a-Src S3C possessing N-terminal palmitoylation signal (a-Src S3C/mCsk) were prepared (see Fig. 1B). These cells were sensitized with IgE and stimulated by receptor clustering, and tyrosine phosphorylation of β and γ subunit and Syk was analyzed as described above. As seen in Fig. 3A (β ip), basal and clustering-induced β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation was again low in Puro/mCsk control cells (lanes 1 and 2). Expression of a-Lyn resulted in increased basal β tyrosine phosphorylation (compare lane 1 with lane 3) and intense clustering-induced β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation (compare lane 2 with lane 4). Expression of a-Fyn only modestly increased basal β tyrosine phosphorylation (compare lane 1 with lane 5) but clearly enhanced clustering-induced β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation (compare lane 2 with lane 6). a-Src expression did not appreciably increase basal β or clustering-dependent β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation above those in Puro/mCsk control (compare lanes 1 and 2 with lanes 7 and 8). In contrast, a-Src S3C expression induced clear increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of β and γ after FcɛRI-clustering (compare lane 2 with lane 10), although its effects on basal β phosphorylation was marginal (lane 1 with lane 9).

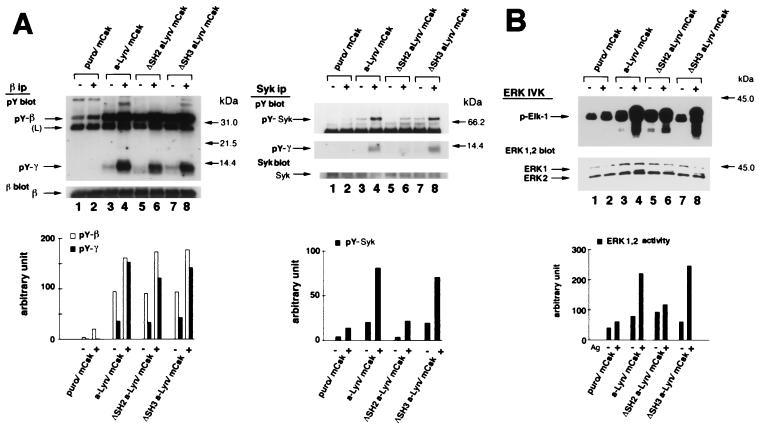

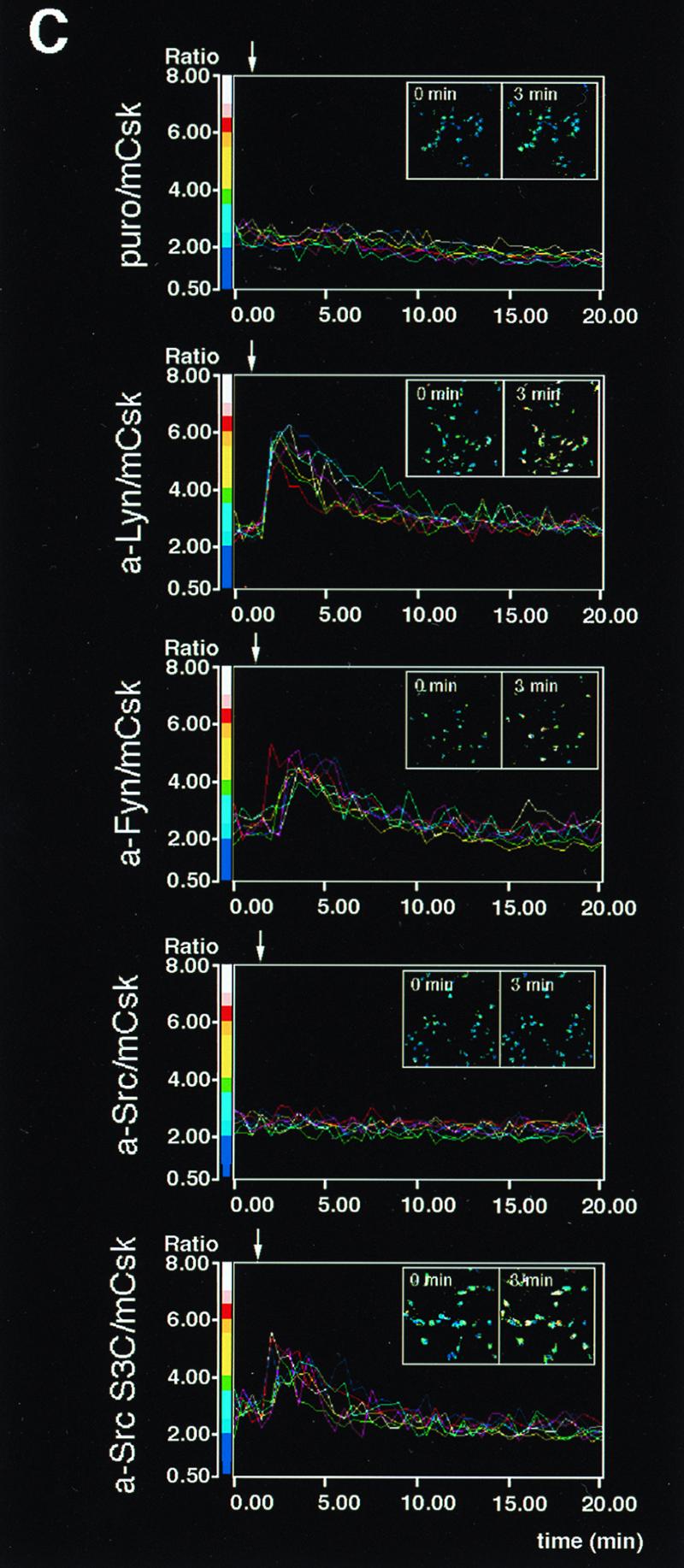

FIG. 3.

Differential abilities of a-Src kinases to restore FcɛRI signaling in mCsk cells. (A) Effects of the expression of a-Src kinases on FcɛRI β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation and Syk tyrosine phosphorylation. mCsk Cells transfected with Puror vector alone (Puro/mCsk) or with mCsk Cells stably expressing a-Lyn (a-Lyn/mCsk), a-Fyn (a-Fyn/mCsk), a-Src (a-Src/mCsk), or a-Src S3C (a-Src S3C/mCsk) were sensitized with IgE. Cells were lyzed before (−) or 5 min after FcɛRI clustering (+). Tyrosine phosphorylation of β and γ subunit and Syk was analyzed, and the data were expressed as described in the legends for Fig. 2B. Expression of a-Lyn, a-Fyn, and a-Src S3C enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation of β and γ subunit and Syk more than the Puro/mCsk control, but a-Src expression was ineffective. See the text for details. (B) ERK1 and -2 MAP kinase activation in mCsk cells coexpressing a-Src kinases. ERK1 and -2 activities before (−) and 5 min after (+) FcɛRI clustering were measured by in vitro kinase assay using Elk-1 as a substrate, as described in the legend for Fig. 2C. Clustering-induced ERK1 and -2 activation was clearly observed in a-Lyn/mCsk cells, a-Fyn/mCsk, and a-Src S3C/mCsk cells. Effects of FcɛRI clustering was only marginal in Puro/mCsk control cells and in a-Src/mCsk cells. (C) Calcium mobilization in mCsk cells coexpressing a-Src kinases. Single cell [Ca2+]i recording was conducted as described in Materials and Methods. See also the legend for Fig. 2A. FcɛRI-mediated calcium mobilization was restored by a-Lyn, a-Fyn, and a-Src S3C but not by a-Src. Data obtained from the functional analyses were reproducible in two independent cell lines.

The differential effects of a-Src kinases were also observed in Syk tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 3A, Syk ip). Expression of a-Lyn increased basal and clustering-induced Syk tyrosine phosphorylation (compare lanes 1 and 2 with lanes 3 and 4). Clustering-induced Syk tyrosine phosphorylation was also augmented to lesser extents by a-Fyn (compare lane 2 with lane 6) and by a-Src S3C expression (lane 2 versus lane 10), but not by a-Src expression (lane 2 versus lane 8). It was also noted that tyrosine phosphorylated γ subunit was coimmunoprecipitated with Syk after clustering in a-Lyn/mCsk cells, a-Fyn/mCsk cells, and a-Src S3C/mCsk cells (lanes 4, 6, and 10) but not in a-Src/mCsk cells (lane 8).

To further explore the relative effects of a-Src kinases, activation of ERK1 and -2 MAP kinases and calcium mobilization were examined. ERK1 and -2 activity was measured by Elk-1 phosphorylation activity. As seen in Fig. 3B, Clustering-induced ERK1 and -2 activation was minimal in Puro/mCsk cells (lanes 1 and 2). Expression of a-Lyn or a-Fyn potently upregulated clustering-induced ERK1 and -2 activation (compare lane 2 with lanes 4 or 6), and Src S3C expression also augmented it to a lesser degree (compare lane 2 with lane 10). Expression of a-Src appeared to increase FcɛRI-independent, basal ERK1 and -2 activity (compare lanes 1 with 7), but clustering-induced activation was marginal (lane 7 with lane 8). Figure 3C shows time-dependent changes in the intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i). Clustering-induced increase in [Ca2+]i was again reconstructed by the expression of a-Lyn, a-Fyn, and a-Src S3C, but not by a-Src. These results were reproducible in two independent clones. Taken together, these findings strongly indicated that FcɛRI signaling is catalyzed by selective Src family kinases and that palmitoylatable Cys3 is critical for kinases to participate in the signaling.

a-Src kinases that reconstitute FcɛRI signaling are physically associated with FcɛRI β subunit and localized at low-density DRMs.

It is postulated that clustering-induced β tyrosine phosphorylation is initiated by small amount of Lyn associated with resting β subunit (80). Therefore, we next tested physical association of a-Src kinases with β by coimmunoprecipitation procedures. Cells were solubilized before and 5 min after FcɛRI clustering and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-β monoclonal antibody. a-Src kinases were detected by immunoblotting with anti-c-myc antibody. As seen in Fig. 4A, a-Lyn, a-Fyn, and a-Src S3C were found to be coimmunoprecipitated with β subunit before and after receptor clustering, but a-Src was not detectably coimmunoprecipitated under either of the conditions. These findings strongly indicated that palmitoylation signal is required for Src family kinases to physically associate with β subunit.

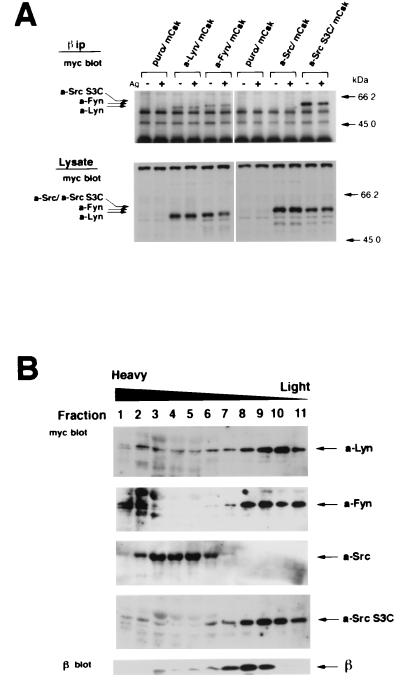

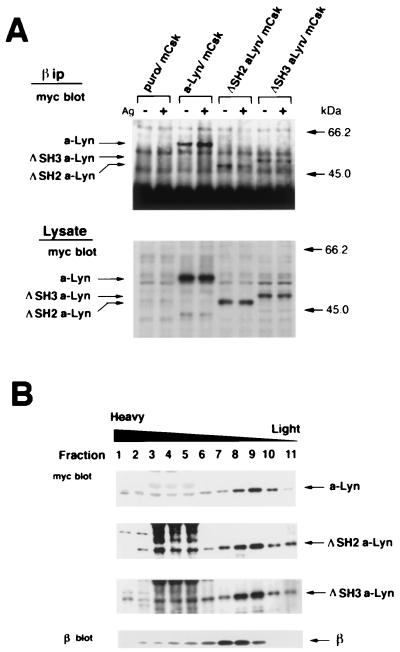

FIG. 4.

Coimmunoprecipitation of a-Src kinases with β subunit (A) and fractionation of a-Src kinases and β subunit by sucrose density gradient centrifugation (B). (A) mCsk cells transfected with Puror vector alone (Puro/mCsk) or mCsk cells stably expressing a-Lyn (a-Lyn/mCsk), a-Fyn (a-Fyn/mCsk), a-Src (a-Src/mCsk), or a-Src S3C (a-Src S3C/mCsk) were solubilized before (−) and 5 min after (+) FcɛRI clustering, and FcɛRI complex was immunoprecipitated with JRK anti-β monoclonal antibody. Immunoprecipitates (β ip) were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-c-myc antibody (myc blot) to detect a-Src kinases. Almost equal amounts of β subunits were recovered in the immunoprecipitates (not shown). An equal volume of aliquots of the total cell lysates (Lysate) was also analyzed by anti-c-myc immunoblotting (myc blot) to ascertain comparable solubilization of a-Src kinases. a-Lyn, a-Fyn, and a-Src S3C were detected in β immunoprecipitates before and after FcɛRI clustering, but a-Src was not detectable under either of the conditions. (B) Quiescent a-Src kinase-expressing mCsk cells were solubilized and subjected to discontinuous sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation as described in Materials and Methods. Protein was extracted and subjected to immunoblotting with anti-c-myc antibody (myc blot) or with JRK (β blot). a-Lyn, a-Fyn, and a-Src S3C possessing N-terminal palmitoylation signal were recovered at low-density fractions (fractions 8 to 11), and a-Src was recovered at high-density fractions (fractions 2 to 6). The β subunit was mainly found at intermediate fractions (fractions 7 to 9) and was codistributed with palmitoylatable a-Src kinases. The β immunoblotting was conducted by using a-Src/mCsk cells. Other cell lines exhibited almost identical β distributions (not shown).

Recent studies have revealed that palmitoylated Src family members are mainly localized at specialized low-density membrane domains, variously called DRMs, glycolipid-enriched membrane domains (GEMs), or sphingolipid-cholesterol rafts (7, 19, 31, 70). The data given above showed that FcɛRI signaling is mediated solely by palmitoylatable a-Src kinases and that the signal is also required for their physical association with β subunit. These findings suggested that localization at DRMs is critical for kinases to encounter FcɛRI β subunit. To test the hypothesis, We fractionated cell lysates from quiescent a-Src-expressing cells by sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation (19, 20), and distribution of a-Src kinases and β subunit was analyzed by immunoblotting. As seen in Fig. 4B, a-Lyn, a-Fyn, and a-Src S3C were mainly found in low-density fractions (fractions 8 to 10), which presumably correspond to DRMs (19). In contrast, a-Src was exclusively localized at high density fractions (fractions 2 to 6). Unexpectedly, β subunit was recovered from intermediate fractions (fractions 7 to 9). It was also found that β subunit was in part codistributed with a-Lyn, a-Fyn, and a-Src S3C (fractions 8 and 9). These two complementary analyses strongly indicated that palmitoylation and resultant DRM association are required for Src family kinases to interact with resting FcɛRI β subunit.

Roles of SH2 and SH3 domains of Lyn in FcɛRI signaling.

Noncatalytic SH2 and SH3 domains of Lyn potentially contribute to FcɛRI signaling through molecular assembly with β and γ subunits or with outer signaling molecules (1–3, 34, 55). However, it has not been determined if these domains are required for FcɛRI signaling. To investigate the roles of SH2 and SH3 domains, a-Lyn lacking the SH2 domain (ΔSH2 a-Lyn) and one lacking the SH3 domain (ΔSH3 a-Lyn) were created and tested for their abilities to restore FcɛRI signaling in mCsk cells. As seen in Fig. 5A (β ip), expression of a-Lyn again clearly enhanced basal β and triggering-induced β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation above control levels in Puro/mCsk cells (compare lanes 1 and 2 with lanes 3 and 4). Expression of ΔSH2 a-Lyn and ΔSH3 a-Lyn also resulted in marked increases in basal and triggering-induced signals (compare lanes 1 and 2 with lanes 5 and 6 or with lanes 7 and 8), and the extents were similar to those caused by a-Lyn expression (compare lanes 3 and 4 with lanes 5 and 6 or with lanes 7 and 8). In contrast, the abilities of ΔSH2 a-Lyn and by ΔSH3 a-Lyn to induce Syk tyrosine phosphorylation were considerably different. As seen in Fig. 5A (Syk ip), expression of a-Lyn again resulted in a moderate increase in basal Syk tyrosine phosphorylation and marked clustering-induced Syk tyrosine phosphorylation (compare lanes 1 and 2 with lanes 3 and 4). Expression of ΔSH2 a-Lyn did not have an influence on the basal signal and only slightly increased clustering-induced Syk tyrosine phosphorylation (compare lanes 1 and 2 with lanes 5 and 6). ΔSH3 a-Lyn expression clearly enhanced basal and triggering-induced signals (compare lanes 1 and 2 with lanes 7 and 8) as effectively as a-Lyn did (compare lanes 3 and 4 with lanes 7 and 8).

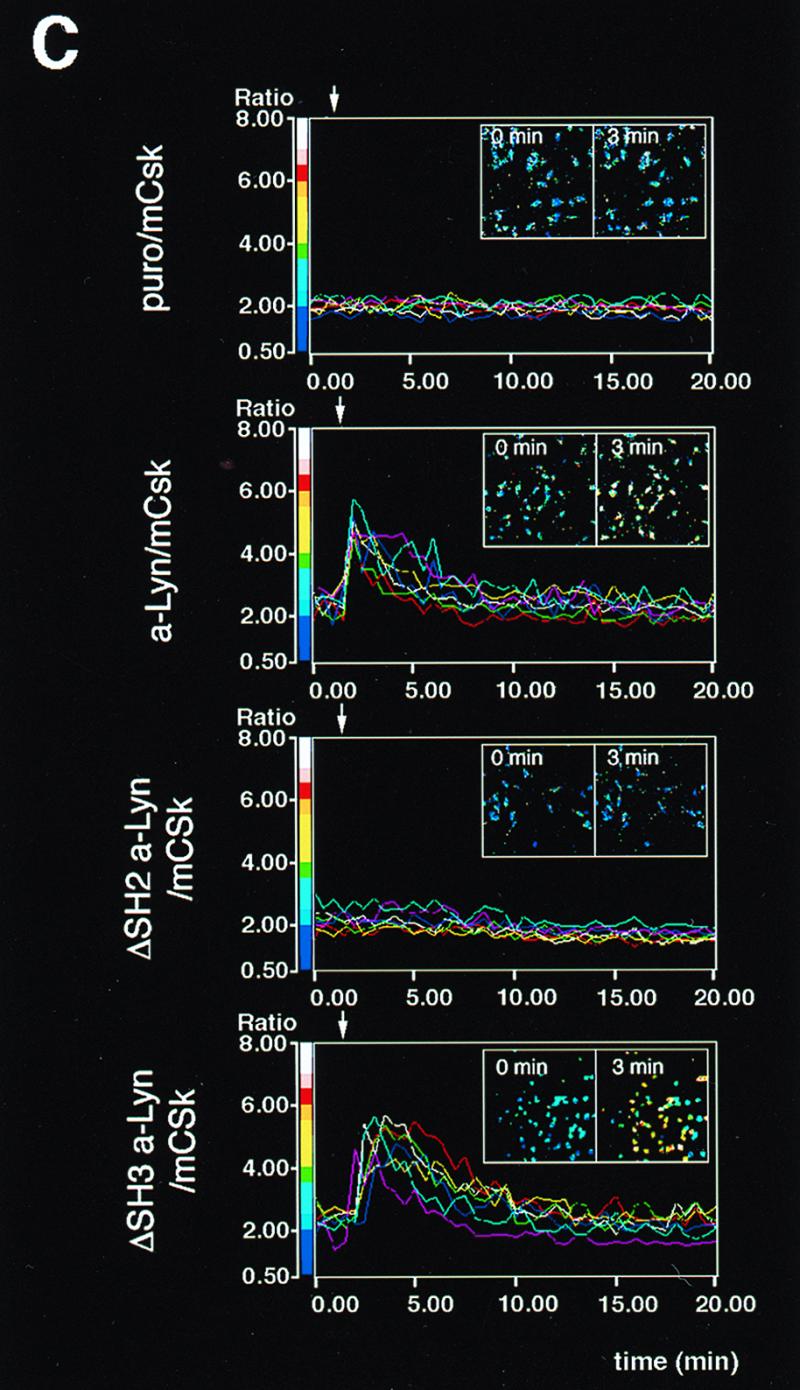

FIG. 5.

Reconstruction of FcɛRI signaling by a-Lyn, ΔSH2 a-Lyn, or by ΔSH3 a-Lyn. (A) Effects of the expression of a-Lyn, ΔSH2 a-Lyn, or ΔSH3 a-Lyn on FcɛRI β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation and Syk tyrosine phosphorylation. Puro/mCsk cells, a-Lyn/mCsk cells, ΔSH2 a-Lyn/mCsk cells, and ΔSH3 a-Lyn/mCsk cells were lyzed before (−) and 5 min after FcɛRI clustering (+). Tyrosine phosphorylation of β and γ subunits and Syk was analyzed, and the data are expressed as described in the legend for Fig. 2B. Expression of ΔSH2 a-Lyn and ΔSH3 a-Lyn enhanced basal-β and clustering-induced β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation as effectively as a-Lyn did. a-Lyn and ΔSH3 a-Lyn clearly augmented Syk tyrosine phosphorylation above control levels in Puro/mCsk cells, whereas the effects of ΔSH2 a-Lyn were marginal. See the text for details. (B) ERK1 and -2 MAP kinase activation in mCsk cells coexpressing a-Lyn, ΔSH2 a-Lyn, or ΔSH3 a-Lyn. ERK1 and -2 activities before (−) and 5 min after (+) FcɛRI clustering were analyzed as described in the legend for Fig. 2C. Clustering-induced ERK1 and -2 activation was restored in a-Lyn/mCsk cells and in ΔSH3 a-Lyn/mCsk cells. In ΔSH2 a-Lyn/mCsk cells, FcɛRI-independent, basal kinase activity was increased above that in Puro/mCsk cells, but the clustering-induced increase was considerably smaller than in a-Lyn/mCsk cells and ΔSH3 a-Lyn/mCsk cells. See the text for details. (C) Calcium mobilization in mCsk cells expressing a-Lyn, ΔSH2 a-Lyn, or ΔSH3 a-Lyn. Data are expressed as described the legend for Fig. 2A. FcɛRI-mediated calcium mobilization was restored by a-Lyn and by ΔSH3 a-Lyn but not by ΔSH2 a-Lyn. Data obtained from the functional analyses were reproducible in two independent cell lines.

Figure 5B shows ERK1 and -2 activation in these cells. Expression of a-Lyn resulted in increased basal activity (compare lane 1 with lane 3) and marked clustering-dependent ERK1 and -2 activation (compare lane 3 with lane 4; 2.8-fold activation). ΔSH2 a-Lyn expression also increased FcɛRI-independent, basal activity (compare lane 1 with lane 5), but its effects on clustering-dependent kinase activation was small (compare lane 5 with lane 6; 1.3-fold activation). ΔSH3 a-Lyn expression moderately increased basal activity (compare lane 1 with lane 7) and yielded intense clustering-dependent activation (compare lane 7 with lane 8; 4.0-fold activation). Figure 5C shows time-dependent calcium mobilization and pseudocolor imaging of [Ca2+]i. Expression of a-Lyn and ΔSH3 a-Lyn successfully restored calcium signaling in mCsk cells, while ΔSH2 a-Lyn did not. These results were reproducible in two independent clones.

Deletion of SH2 or SH3 domain did not abrogate a-Lyn association with FcɛRI β subunit or localization at DRMs.

The possible association of ΔSH2 a-Lyn and ΔSH3 a-Lyn with FcɛRI complex was tested by coimmunoprecipitation experiments with JRK anti-β antibody. As seen in Fig. 6A, ΔSH2 a-Lyn and ΔSH3 a-Lyn were coimmunoprecipitated with β subunit, before and after receptor clustering. We next tested the association of ΔSH2 a-Lyn and ΔSH3 a-Lyn with low-density, DRMs by sucrose density gradient centrifugation followed by immunoblotting. As seen in Fig. 6B, ΔSH2 a-Lyn and ΔSH3 a-Lyn were mainly localized at low-density fractions (fractions 8 to 11), and their distributions were almost identical to that of a-Lyn. The β subunit was again found mainly in slightly higher density fractions (fractions 7 to 9), and it was partially codistributed with ΔSH2 a-Lyn and with ΔSH3 a-Lyn (fractions 8 and 9). These findings indicated that those submolecular domains are not essential for Lyn to physically associate with β subunit or to be localized at DRMs.

FIG. 6.

Physical association of a-Lyn, ΔSH2 a-Lyn, or ΔSH3 a-Lyn with FcɛRI β subunit (A) and their distribution as analyzed by sucrose density gradient centrifugation (B). (A) Puro/mCsk cells, a-Lyn/mCsk cells, ΔSH2 a-Lyn/mCsk cells, and ΔSH3 a-Lyn/mCsk cells were solubilized before (−) and 5 min after (+) FcɛRI clustering and subjected to coimmunoprecipitation analysis by using JRK anti-β antibody as described in the legend for Fig. 4A. β Immunoprecipitates (β ip) were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-c-myc antibody (myc blot). Almost equal amounts of β subunits were recovered in the immunoprecipitates (not shown). An equal volume of aliquots of the total cell lysates (Lysate) was also analyzed by anti-c-myc immunoblotting (myc blot) to ascertain comparable solubilization efficiency. a-Lyn, ΔSH2 a-Lyn, or ΔSH3 a-Lyn were detected in β-immunoprecipitates before and after FcɛRI-clustering. (B) Quiescent a-Lyn/mCsk cells, ΔSH2 a-Lyn/mCsk cells, and ΔSH3 a-Lyn/mCsk cells were solubilized, and the distributions of a-Lyn-derived kinases and β subunit were analyzed by sucrose density gradient centrifugation, as described in the legend for Fig. 4B. a-Lyn, ΔSH2 a-Lyn, and ΔSH3 a-Lyn were found mainly at low-density fractions (fractions 7 to 11) and β subunit was mainly in the slightly higher density fractions (fractions 6 to 9) (see also Fig. 4B). The distribution of β subunit partly overlapped with those of a-Lyn-derived kinases. The β immunoblotting was conducted with a-Lyn/mCsk cells. Other cell lines exhibited almost identical β distributions (not shown).

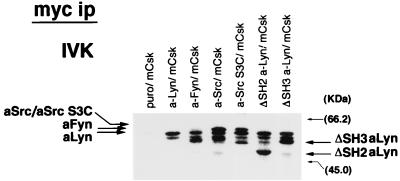

Catalytic activity of a-Src kinases.

The inability of a-Src or ΔSH2 a-Lyn to transmit FcɛRI signaling could be due to impaired catalytic activity of the constructs. To exclude the possibility, a-Src kinases were immunoprecipitated with anti-c-myc antibody and subjected to in vitro autophosphorylation assay. As seen in Fig. 7, in all of the immunoprecipitates from cells expressing a-Src kinases, kinase activity was detected, and autophosphorylation signals at expected migration positions were observed. Immunoprecipitates from Puro/mCsk cells did not contain kinase activity. In addition, autophosphorylation signals of a-Src and ΔSH2 a-Lyn were comparable to or even higher than those of a-Src S3C and a-Lyn, respectively. From these observations, it was concluded that the defective signal transduction by a-Src or ΔSH2 a-Lyn was not ascribed to reduced catalytic activities of these constructs.

FIG. 7.

In vitro kinase assay of a-Src kinases. Quiescent Puro/mCsk cells, a-Lyn/mCsk cells, a-Fyn/mCsk cells, a-Src/mCsk cells, a-Src S3C/mCsk cells, ΔSH2 a-Lyn/mCsk cells, and ΔSH3 a-Lyn/mCsk cells were solubilized, a-Src kinases were immunoprecipitated with anti-c-myc antibody, and autophosphorylation activities were assayed. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by using a Fuji image analyzer BAS 2000. Expected migration positions of autophosphorylated a-Src kinase are indicated by arrows. Molecular mass markers are on the right. Kinase activity was not recovered from Puro/mCsk cell lysate. Phosphorylated proteins with molecular masses identical to those of a-Src kinases and other species were detected in the samples from a-Src kinase-expressing cells.

DISCUSSION

Although the sequential biochemical signals following FcɛRI aggregation have been elucidated in increasing detail, the roles of individual Src family members and their submolecular domains in the initiation and progression of the signaling cascade have not been fully elucidated. To address these issues, we attempted to dissect the early signaling by reconstitution experiments. FcɛRI signaling in RBL2H3 cells was first suppressed by mCsk overexpression and then reconstituted with a-Src kinases lacking C-terminal regulatory tyrosine. To directly compare the expression levels of the kinases and, consequently, their relative abilities to restore the signaling, constructs were designed in which the C-terminal sequences were replaced with a c-myc tag. We utilized a-Lyn and a-Fyn as kinases containing palmitoylatable Cys3 in their SH4 domain and a-Src as one lacking the residue (61, 76). A mutated a-Src possessing Cys3 was also prepared to further ascertain the role of the palmitoylation site. To assess the roles of SH2 and SH3 domains, a-Lyn-derived constructs lacking either of the domains were created.

Through the initial comparison of control cells, mCsk- and mCsk(−)-overexpressing cells, it was observed that basal tyrosine phosphorylation of FcɛRI β subunit was suppressed by mCsk in a kinase-dependent manner. These findings supported the proposed concept that Src family kinase(s) associated with resting β subunit is in part in a C-terminal tyrosine-dephosphorylated open conformation (56, 74, 88). mCsk also potently downregulated clustering-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of β and γ subunits and Syk tyrosine kinase, calcium mobilization, and ERK1 and -2 MAP kinase activation in a kinase-dependent manner. mCsk suppressed the series of FcɛRI signaling most probably by decreasing the ratio of C-terminal tyrosine-dephosphorylated, open-conformation kinases. These findings also supported the physiological relevance of the current reconstitution experiments with C-terminal tyrosine-deleted a-Src kinases.

One of major findings in the current study is that FcɛRI signaling is restored by the expression of a-Src kinases possessing N-terminal palmitoylation signal. Expression of a-Lyn and a-Fyn, both of which possess palmitoylatable Cys3, effectively reconstructed the triggering-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of β, γ, and Syk, the Syk association with γ, the ERK1 and -2 activation and calcium signal; however, a-Src expression did not induce initial signal of β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation. Creation of Cys3 in a-Src (a-Src S3C) resulted in effective restoration of the series of signaling. The inability of a-Src to reconstruct the signals could not be ascribed to loss of catalytic activity in a-Src construct (see reference 25 and Fig. 7) or to accelerated downregulation of surface FcɛRI (see Fig. 1C). Although it should be taken into account that a-Src kinases are not in normal equilibrium, these findings strongly indicated that FcɛRI signaling is catalyzed by selected Src family kinases possessing N-terminal palmitoylation site. As an alternative explanation, it may be possible that overexpression of a-Src kinases compete for the inhibitory action of mCsk by titrating out mCsk molecule and that FcɛRI signal in a-Src-kinase-expressing cells are initiated by endogenous Src family kinases. These possibilities should be examined by further studies. However, differential abilities of a-Src kinases and a-Lyn-derived constructs to convey the signaling suggest that signal restoration by a-Src kinases is not solely due to the effects of overexpression.

It was also found that a-Lyn, a-Fyn, and a-Src S3C was physically associated with resting and aggregated β subunit but that a-Src was not. Based upon these two lines of evidence, it is strongly argued that N-terminal palmitoylation is required for Src family kinases to associate with resting FcɛRI and that this association is critical for kinases to initiate β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation after FcɛRI clustering. In accordance with our observations, Timson Gauen et al. have shown that N-terminal palmitoylation is required for Src family kinases to associate with ectopically expressed chimeric TCR ζ subunit (76). In the initial study that related Src family kinases with FcɛRI, c-Src was shown to be activated after FcɛRI clustering (18). The current data suggest that the c-Src activation is not the direct consequence of receptor aggregation but is a more downstream event.

The series of observations including mCsk-mediated suppression of basal β and clustering-dependent β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation, physical association of coexpressed a-Lyn with resting FcɛRI, and the resultant recovery of triggering-induced β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation are reminiscent of the proposed concept that the early FcɛRI signaling relies upon receptor-associated kinase in open conformation (80, 88). It may be of note that a-Lyn expression enhanced clustering-independent, basal tyrosine phosphorylation of β subunit and Syk. Therefore, interaction of autoactive a-Lyn with β subunit partially mimicked FcɛRI signaling. However, receptor clustering was still required for full signaling. How receptor clustering facilitates the signal progression in a-Lyn/mCsk cells is an intriguing issue yet to be investigated. a-Lyn might be further activated after receptor clustering by SH3 domain displacement (86) and/or by phosphorylation of activation loop tyrosine, or it may be that entirely different signaling mechanisms are required in parallel to induce full signaling. Concerning the relative abilities of a-Src kinases to initiate FcɛRI signaling, basal β tyrosine phosphorylation was effectively increased by a-Lyn and to comparable levels by ΔSH2 a-Lyn and by ΔSH3 a-Lyn, whereas only moderately by a-Fyn and by a-Src S3C (see Fig. 3A and 5A, β ip). Clustering-induced β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation was also most effectively enhanced by the Lyn-derived constructs. These findings suggest the existence of structural characteristics of Lyn, apart from palmitoylation, SH2 domain, or SH3 domain, that are advantageous for FcɛRI signal triggering.

It has become increasingly clear that one of the roles of N-terminal palmitoylation is to sort Src family kinases into specialized low-density membrane fractions, DRMs, GEMs, or sphingolipid-cholesterol rafts (7, 31, 67, 70). Recent biochemical and fluorescence imaging analyses showed that FcɛRI is rapidly translocated to DRMs, in the vicinity of Src family kinases, and that FcɛRI subunits are then phosphorylated by DRM-associated kinases (19, 21). This concept that recruitment of FcɛRI to DRMs is required for FcɛRI to meet Src family kinases is somewhat different from our proposal that clustering-induced early signaling is catalyzed by Src family kinases already interacting with resting receptor. We thus examined the distribution of a-Src kinases and β subunit in resting RBL clones by sucrose density gradient centrifugation of the cell lysates (19, 21). Our data showed that a-Lyn, a-Fyn, and a-Src S3C are localized almost exclusively at low-density fractions that presumably correspond to DRMs and that a-Src was at clearly separated high density fractions (see Fig. 4B). Intriguingly, β subunit was found in intermediate-density fractions that are in part overlapped with those of DRM-associated a-Src family kinases. Although precise characterization of the β-associating, intermediate-density membrane domains should be elucidated by future studies, codistribution of resting β subunit with N-palmitoylatable kinases, together with their physical association (see Fig. 4C) and with increased basal β tyrosine phosphorylation in a-Lyn/mCsk cells (Fig. 3A and 5A), strongly argued that the interaction occurs before receptor clustering. Montixi et al. showed that PP1, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor relatively specific to Src family kinases, suppressed TCR recruitment to the DRMs (47). Therefore, it could be postulated that clustering-induced FcɛRI signaling is initiated by kinases associated with resting β subunit and that FcɛRI association with DRMs after receptor engagement is a signal amplification process.

The next major finding is that the SH2 domain of Lyn is not essential for tyrosine phosphorylation of FcɛRI subunits but is required for the progression of the signal: deletion of SH2 or SH3 domain from a-Lyn did not significantly alter its ability to associate with DRMs or with resting FcɛRI or to augment basal β and clustering-induced β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation, albeit that γ tyrosine phosphorylation by ΔSH2 a-Lyn is slightly less effective than those by a-Lyn or by ΔSH3 a-Lyn (see Fig. 5A, β ip). In contrast, SH2 deletion from a-Lyn profoundly decreased its ability to enhance clustering-induced Syk tyrosine phosphorylation and its association with γ subunit. In the TCR system, Straus et al. showed that Lck containing a mutation in the phosphotyrosine-binding pocket of the SH2 domain only marginally induced tyrosine phosphorylation of TCR ζ subunit, a homologue of FcɛRI γ subunit, in JCam1 T cells and proposed that SH2 domain is indispensable for the earliest signal of ζ phosphorylation (72). Our findings are in part consistent with these results, but the presence of the FcɛRI-specific β subunit, which lies upstream of γ (39) in our system, allowed more precise dissection of the early signaling. Our data indicated that SH2 domain is required to link initial β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation to recruitment of Syk to γ and its tyrosine phosphorylation. It may be worthy to note that the abortive signaling by ΔSH2 a-Lyn is quite similar to the interrupted signaling by antigen and Fc receptors stimulated with partial agonists: FcɛRI or TCR stimulated with agonists with low affinity or valence was shown to induce the tyrosine phosphorylation of ITAM-containing subunits, whereas they were unable to recruit or phosphorylate Syk or closely related Zap 70 tyrosine kinase (33, 38, 77). The signal interruption is ascribed to insufficient time for the agonist-receptor interaction to overcome the time-consuming step of signaling complex formation (kinetic proofreading model) (44). From the above data, it could be postulated that SH2 domain of Lyn is required to pass through the first proofreading step, presumably by stabilizing signaling molecule complex. The observed decrease in γ tyrosine phosphorylation could be due to different phosphorylation patterns from that in the full signaling as observed in partial agonist-stimulated TCR ζ subunit (32) or to the absence of γ-Syk association that is protective against rapid dephosphorylation of γ (66). Obviously, how SH2 domain of Lyn works in the signal progression should be elucidated by further studies. Associations of Lyn's SH2 domain with tyrosine phosphorylated β subunit (34) and with Syk (2, 3) are apparent candidates of the signal progression mechanisms.

It seemed that the SH3 domain of Lyn is not essential for early FcɛRI signaling leading to calcium mobilization and to ERK1 and -2 activation. The SH3 domain of Lyn potentially interacts with p85 subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase or with Bruton's tyrosine kinase (1, 55), both of which are required for calcium signaling, especially in its sustained phases (9, 22). We could not detect differences in [Ca2+]i elevation between a-Lyn cells and ΔSH3 a-Lyn cells. In addition, Bruton's tyrosine kinase was almost equally tyrosine phosphorylated after FcɛRI clustering in these cell lines (not shown). These data suggest that phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Bruton's tyrosine kinase are recruited to the membrane by interacting with more physiological ligands, such as c-Cbl (24) and phosphatidylinositol trisphosphate (9, 22), respectively. Caron et al. showed that Lck 505F lacking SH3 domain fully augments TCR-mediated early signaling, including protein tyrosine phosphorylation, but that it was unable to induce interleukin-2 production (10). We also examined FcɛRI-mediated TNF-α synthesis in RBL cell lines and found that mCsk expression did not significantly suppress TNF-α synthesis, in spite of effective downregulation of the upstream signal of ERK1 and -2 activation (see Fig. 2C). One of our laboratories also noted that FcɛRI-mediated cytokine production is preserved in Lyn−/− murine mast cells, in which protein tyrosine phosphorylation is profoundly suppressed (51). The apparent discrepancy between early and late signaling events might indicate unexpectedly low threshold of FcɛRI-mediated cytokine transcription.

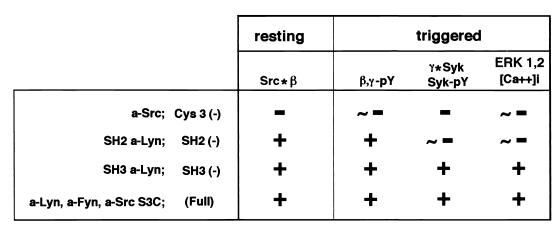

The current reconstitution study using the panel of mutated Src kinases finely dissected early FcɛRI signaling is summarized in Fig. 8. The Cys3 and SH2 domains of Src family kinases seem to function at two different steps in the pathway. First, Cys3 is required for the interaction of kinases with resting FcɛRI β and (designated as Src*β), as assessed by their coimmunoprecipitation and codistribution after sucrose density gradient centrifugation. a-Src kinases associated with resting FcɛRI β were able to reconstruct triggering-induced β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation (β,γ-pY), recruitment of Syk to phosphorylated γ (γ*Syk), Syk tyrosine phosphorylation (Syk-pY), and calcium mobilization ([Ca2+]i) and ERK1 and -2 activation (ERK1 and -2). The SH2 domain of Lyn is dispensable for its association with FcɛRI β (Src*β) or for triggering-dependent β and γ tyrosine phosphorylation (β,γ-pY), but is required to link the signal to the next step of Syk recruitment (γ*Syk) and its tyrosine phosphorylation (Syk-pY). These data may further the knowledge required for the understanding of the most fundamental issue of how receptor aggregation is translated into biochemical signaling.

FIG. 8.

Relative abilities of a-Src kinases to restore the sequential signaling steps. “∗” and “-pY” denote physical interaction and tyrosine phosphorylation, respectively. [Ca2+]i and “ERK1, 2” indicate the increase in intracellular calcium concentration and ERK1 and -2 MAP kinase activation. See the text for details.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture, by Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology from the Science and Technology Agency of the Japanese Government, and by grants from Ono Medical Research Foundation, Manabe Research Foundation, and Uehara Memorial Foundation.

We thank H. Ota-Ichijo, and M. Saka for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexandropoulos K, Cheng G, Baltimore D. Proline-rich sequences that bind to Src homology 3 domains with individual specificities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3110–3114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amoui M, Draberova L, Tolar P, Draber P. Direct interaction of Syk and Lyn protein tyrosine kinases in rat basophilic leukemia cells activated via type I Fcɛ receptors. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:321–328. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aoki Y, Kim Y T, Stillwell R, Kim T J, Pillai S. The SH2 domains of Src family kinases associate with Syk. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15658–15663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaven M A, Metzger H. Signal transduction by Fc receptors: the FcɛRI case. Immunol Today. 1993;14:222–226. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90167-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benhamou M, Ryba N J, Kihara H, Nishikata H, Siraganian R P. Protein-tyrosine kinase p72syk in high affinity IgE receptor signaling. Identification as a component of pp72 and association with the receptor γ chain after receptor aggregation. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23318–23324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benhamou M, Siraganian R P. Protein-tyrosine phosphorylation: an essential component of FcɛRI signaling. Immunol Today. 1992;13:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90152-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bijlmakers M J, Isobe-Nakamura M, Ruddock L J, Marsh M. Intrinsic signals in the unique domain target p56lck to the plasma membrane independently of CD4. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1029–1040. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.5.1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blank U, Ra C, Miller L, White K, Metzger H, Kinet J P. Complete structure and expression in transfected cells of high affinity IgE receptor. Nature. 1989;337:187–189. doi: 10.1038/337187a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolland S, Pearse R N, Kurosaki T, Ravetch J V. SHIP modulates immune receptor responses by regulating membrane association of Btk. Immunity. 1998;8:509–516. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80555-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caron L, Abraham N, Pawson T, Veillette A. Structural requirements for enhancement T-cell responsiveness by the lymphocyte-specific tyrosine protein kinase p56lck. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2720–2729. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.6.2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chow L M, Fournel M, Davidson D, Veillette A. Negative regulation of T-cell receptor signalling by tyrosine protein kinase p50csk. Nature. 1993;365:156–60. doi: 10.1038/365156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cloutier J F, Chow L M, Veillette A. Requirement of the SH3 and SH2 domains for the inhibitory function of tyrosine protein kinase p50csk in T lymphocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5937–44. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.5937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper J A, Howell B. The when and how of Src regulation. Cell. 1993;73:1051–1054. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper J A, King C S. Dephosphorylation or antibody binding to the carboxy terminus stimulates pp60c-src. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:4467–4477. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.12.4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crowley M T, Costello P S, Fitzer-Attas C J, Turner M, Meng F, Lowell C, Tybulewicz V L, DeFranco A L. A critical role for Syk in signal transduction and phagocytosis mediated by Fcγ receptors on macrophages. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1027–1039. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D'Oro U, Vacchio M S, Weissman A M, Ashwell J D. Activation of the Lck tyrosine kinase targets cell surface T cell antigen receptors for lysosomal degradation. Immunity. 1997;7:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80383-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daeron M. Fc receptor biology. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:203–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eiseman E, Bolen J B. Engagement of the high-affinity IgE receptor activates src protein-related tyrosine kinases. Nature. 1992;355:78–80. doi: 10.1038/355078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Field K A, Holowka D, Baird B. Compartmentalized activation of the high affinity immunoglobulin E receptor within membrane domains. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4276–4280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Field K A, Holowka D, Baird B. FcɛRI-mediated recruitment of p53/56lyn to detergent-resistant membrane domains accompanies cellular signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9201–9205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Field K A, Holowka D, Baird B. Structural aspects of the association of FcɛRI with detergent-resistant membranes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1753–1758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fluckiger A C, Li Z, Kato R M, Wahl M I, Ochs H D, Longnecker R, Kinet J P, Witte O N, Scharenberg A M, Rawlings D J. Btk/Tec kinases regulate sustained increases in intracellular Ca2+ following B-cell receptor activation. EMBO J. 1998;17:1973–1985. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gounni A S, Lamkhioued B, Ochiai K, Tanaka Y, Delaporte E, Capron A, Kinet J P, Capron M. High-affinity IgE receptor on eosinophils is involved in defence against parasites. Nature. 1994;367:183–186. doi: 10.1038/367183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartley D, Corvera S. Formation of c-Cbl: phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase complexes on lymphocyte membranes by a p56lck-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21939–21943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.21939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honda H, Oda H, Nakamoto T, Honda Z, Sakai R, Suzuki T, Saito T, Nakamura K, Nakao K, Ishikawa T, Katsuki M, Yazaki Y, Hirai H. Cardiovascular anomaly, impaired actin bundling and resistance to Src-induced transformation in mice lacking p130Cas. Nat Genet. 1998;19:361–365. doi: 10.1038/1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honda Z, Nakamura M, Miki I, Minami M, Watanabe T, Seyama Y, Okado H, Toh H, Ito K, Miyamoto T, et al. Cloning by functional expression of platelet-activating factor receptor from guinea-pig lung. Nature. 1991;349:342–346. doi: 10.1038/349342a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honda Z, Suzuki T, Hirose N, Aihara M, Shimizu T, Nada S, Okada M, Ra C, Morita Y, Ito K. Roles of C-terminal Src kinase in the initiation and the termination of the high affinity IgE receptor-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25753–25760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imamoto A, Soriano P. Disruption of the csk gene, encoding a negative regulator of Src family tyrosine kinases, leads to neural tube defects and embryonic lethality in mice. Cell. 1993;73:1117–1124. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90641-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwashima M, Irving B A, van Oers N S, Chan A C, Weiss A. Sequential interactions of the TCR with two distinct cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases. Science. 1994;263:1136–1139. doi: 10.1126/science.7509083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jouvin M H, Numerof R P, Kinet J P. Signal transduction through the conserved motifs of the high affinity IgE receptor FcɛRI. Semin Immunol. 1995;7:29–35. doi: 10.1016/1044-5323(95)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabouridis P S, Magee A I, Ley S C. S-Acylation of LCK protein tyrosine kinase is essential for its signalling function in T lymphocytes. EMBO J. 1997;16:4983–4998. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kersh E N, Shaw A S, Allen P M. Fidelity of T cell activation through multistep T cell receptor ζ phosphorylation. Science. 1998;281:572–575. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5376.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kersh G J, Allen P M. Essential flexibility in the T-cell recognition of antigen. Nature. 1996;380:495–498. doi: 10.1038/380495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kihara H, Siraganian R P. Src homology 2 domains of Syk and Lyn bind to tyrosine-phosphorylated subunits of the high affinity IgE receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22427–22432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinet J P. The gamma-ζ dimers of Fc receptors as connectors to signal transduction. Curr Opin Immunol. 1992;4:43–48. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(92)90122-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinet J P, Blank U, Ra C, White K, Metzger H, Kochan J. Isolation and characterization of cDNAs coding for the beta subunit of the high-affinity receptor for immunoglobulin E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6483–6487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurosaki T, Takata M, Yamanashi Y, Inazu T, Taniguchi T, Yamamoto T, Yamamura H. Syk activation by the Src-family tyrosine kinase in the B cell receptor signaling. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1725–1729. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lanzavecchia A, Lezzi G, Viola A. From TCR engagement to T cell activation: a kinetic view of T cell behavior. Cell. 1999;96:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80952-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin S, Cicala C, Scharenberg A M, Kinet J P. The FcɛRI β subunit functions as an amplifier of FcɛRI γ-mediated cell activation signals. Cell. 1996;85:985–995. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lowell C A, Soriano P. Knockouts of Src-family kinases: stiff bones, wimpy T cells, and bad memories. Gen Dev. 1996;10:1845–1857. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.15.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lowell C A, Soriano P, Varmus H E. Functional overlap in the src gene family: inactivation of hck and fgr impairs natural immunity. Genes Dev. 1994;8:387–398. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marais R, Wynne J, Treisman R. The SRF accessory protein Elk-1 contains a growth factor-regulated transcriptional activation domain. Cell. 1993;73:381–393. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90237-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maurer D, Fiebiger E, Reininger B, Wolff-Winiski B, Jouvin M H, Kilgus O, Kinet J P, Stingl G. Expression of functional high affinity immunoglobulin E receptors (FcɛRI) on monocytes of atopic individuals. J Exp Med. 1994;179:745–750. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKeithan T W. Kinetic proofreading in T-cell receptor signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5042–5046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Metzger H. The receptor with high affinity for IgE. Immunol Rev. 1992;125:37–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1992.tb00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyazaki J, Takaki S, Araki K, Tashiro F, Tominaga A, Takatsu K, Yamamura K. Expression vector system based on the chicken β-actin promoter directs efficient production of interleukin-5. Gene. 1989;79:269–277. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montixi C, Langlet C, Bernard A M, Thimonier J, Dubois C, Wurbel M A, Chauvin J P, Pierres M, He H T. Engagement of T cell receptor triggers its recruitment to low-density detergent-insoluble membrane domains. EMBO J. 1998;17:5334–5348. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mustelin T, Burn P. Regulation of Src family tyrosine kinases in lymphocytes. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:215–220. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90192-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nada S, Okada M, MacAuley A, Cooper J A, Nakagawa H. Cloning of a complementary DNA for a protein-tyrosine kinase that specifically phosphorylates a negative regulatory site of p60c-src. Nature. 1991;351:69–72. doi: 10.1038/351069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nada S, Yagi T, Takeda H, Tokunaga T, Nakagawa H, Ikawa Y, Okada M, Aizawa S. Constitutive activation of Src family kinases in mouse embryos that lack Csk. Cell. 1993;73:1125–1135. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90642-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nishizumi H, Yamamoto T. Impaired tyrosine phosphorylation and Ca2+ mobilization, but not degranulation, in lyn-deficient bone marrow-derived mast cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:2350–2355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene. 1991;108:193–199. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okada M, Nada S, Yamanashi Y, Yamamoto T, Nakagawa H. CSK: a protein-tyrosine kinase involved in regulation of src family kinases. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:24249–24252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paolini R, Jouvin M H, Kinet J P. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the high-affinity receptor for immunoglobulin E immediately after receptor engagement and disengagement. Nature. 1991;353:855–858. doi: 10.1038/353855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pleiman C M, Hertz W M, Cambier J C. Activation of phosphatidylinositol-3′ kinase by Src-family kinase SH3 binding to the p85 subunit. Science. 1994;263:1609–1612. doi: 10.1126/science.8128248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pribluda V S, Pribluda C, Metzger H. Transphosphorylation as the mechanism by which the high-affinity receptor for IgE is phosphorylated upon aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11246–11250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ra C, Jouvin M H, Blank U, Kinet J P. A macrophage Fcγ receptor and the mast cell receptor for IgE share an identical subunit. Nature. 1989;341:752–754. doi: 10.1038/341752a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ra C, Jouvin M H, Kinet J P. Complete structure of the mouse mast cell receptor for IgE (FcɛRI) and surface expression of chimeric receptors (rat-mouse-human) on transfected cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:15323–15327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ravetch J V, Kinet J P. Fc receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:457–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.002325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Resh M D. Interaction of tyrosine kinase oncoproteins with cellular membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1155:307–322. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(93)90012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Resh M D. Myristylation and palmitylation of Src family members: the fats of the matter. Cell. 1994;76:411–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reth M. Antigen receptor tail clue. Nature. 1989;338:383–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rider L G, Hirasawa N, Santini F, Beaven M A. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade is suppressed by low concentrations of dexamethasone in mast cells. J Immunol. 1996;157:2374–2380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Samelson L E, Phillips A F, Luong E T, Klausner R D. Association of the Fyn protein-tyrosine kinase with the T-cell antigen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4358–4362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scharenberg A M, Kinet J P. Initial events in Fc epsilon RI signal transduction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1994;94:1142–1146. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(94)90323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scharenberg A M, Lin S, Cuenod B, Yamamura H, Kinet J P. Reconstitution of interactions between tyrosine kinases and the high affinity IgE receptor which are controlled by receptor clustering. EMBO J. 1995;14:3385–3394. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07344.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shenoy-Scaria A M, Gauen L K, Kwong J, Shaw A S, Lublin D M. Palmitylation of an amino-terminal cysteine motif of protein tyrosine kinases p56lck and p59fyn mediates interaction with glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6385–6392. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shiue L, Green J, Green O M, Karas J L, Morgenstern J P, Ram M K, Taylor M K, Zoller M J, Zydowsky L D, Bolen J B. Interaction of p72syk with the γ and β subunits of the high-affinity receptor for immunoglobulin E, FcɛRI. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:272–281. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sicheri F, Moarefi I, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the Src family tyrosine kinase Hck. Nature. 1997;385:602–609. doi: 10.1038/385602a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Simons K, Ikonen E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature. 1997;387:569–572. doi: 10.1038/42408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stephan V, Benhamou M, Gutkind J S, Robbins K C, Siraganian R P. Fc epsilon RI-induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation of pp72 in rat basophilic leukemia cells (RBL-2H3). Evidence for a novel signal transduction pathway unrelated to G protein activation and phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5434–5441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Straus D B, Chan A C, Patai B, Weiss A. SH2 domain function is essential for the role of the Lck tyrosine kinase in T cell receptor signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9976–9981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.9976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Suzuki T, Shoji S, Yamamoto K, Nada S, Okada M, Yamamoto T, Honda Z. Essential roles of Lyn in fibronectin-mediated filamentous actin assembly and cell motility in mast cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:3694–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tamir I, Cambier J C. Antigen receptor signaling: integration of protein tyrosine kinase functions. Oncogene. 1998;17:1353–1364. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]