Significance

Despite the success of anti–PD-1 cancer therapy, whether and how T cells with different antigen specificity and affinity are differentially regulated by PD-1 remain vaguely understood. By analyzing T cell receptors (TCRs) with different affinities to peptide–MHC complexes (pMHC) and pMHCs with different affinities to TCR, we show that PD-1 signaling specifically inhibits transcription of genes that are inducible by less efficient TCR signals through low TCR:pMHC affinity interactions. Accordingly, T cells with low-affinity to tumor-antigen were preferentially expanded in PD-1–deficient mice. Thus, PD-1 imposes qualitative control of T cell responses by preferentially suppressing low-affinity T cells. Precise and deeper understandings of the functional characteristics of PD-1 will support the development of effective and safe immunotherapies.

Keywords: T cell activation, coreceptor, PD-1, affinity, EC50

Abstract

Anti–PD-1 therapies can activate tumor-specific T cells to destroy tumors. However, whether and how T cells with different antigen specificity and affinity are differentially regulated by PD-1 remain vaguely understood. Upon antigen stimulation, a variety of genes is induced in T cells. Recently, we found that T cell receptor (TCR) signal strength required for the induction of genes varies across different genes and PD-1 preferentially inhibits the induction of genes that require stronger TCR signal. As each T cell has its own response characteristics, inducibility of genes likely differs across different T cells. Accordingly, the inhibitory effects of PD-1 are also expected to differ across different T cells. In the current study, we investigated whether and how factors that modulate T cell responsiveness to antigenic stimuli influence PD-1 function. By analyzing TCRs with different affinities to peptide–MHC complexes (pMHC) and pMHCs with different affinities to TCR, we demonstrated that PD-1 inhibits the expression of TCR-inducible genes efficiently when TCR:pMHC affinity is low. In contrast, affinities of peptides to MHC and MHC expression levels did not affect PD-1 sensitivity of TCR-inducible genes although they markedly altered the dose responsiveness of T cells by changing the efficiency of pMHC formation, suggesting that the strength of individual TCR signal is the key determinant of PD-1 sensitivity. Accordingly, we observed a preferential expansion of T cells with low-affinity to tumor-antigen in PD-1–deficient mice upon inoculation of tumor cells. These results demonstrate that PD-1 imposes qualitative control of T cell responses by preferentially suppressing low-affinity T cells.

T cell activation initiated by antigen-dependent signals through T cell receptors (TCRs) is tightly controlled by antigen-independent signals through a variety of stimulatory and inhibitory coreceptors (1–4). Inhibitory coreceptors play especially important roles in the development of self-tolerance as the immune cells learn not to attack host cells. However, such inhibitory coreceptors can be hijacked by tumors and pathogens to escape from the immune system. Anti–PD-1 therapies that aim to activate tumor-specific T cells to destroy cancer by banning such immune escape of tumor cells significantly improved the outcomes of patients with diverse cancer types and revolutionized cancer treatment (5, 6). Nevertheless, response rates are rather low and immune-related adverse events (irAEs) are observed in substantial proportion of patients (7, 8), indicative of the continued need to decipher the complex biology of PD-1 as well as T cell activation.

Diversity and antigen specificity are the hallmarks of T cell responses. Each T cell expresses TCRs of a unique amino acid sequence and responds to major histocompatibility complexes presenting cognate peptides (pMHCs) on antigen-presenting cells (APCs). As the antigen specificities of T cells and the amino acid sequences of peptides are diverse, the affinities of TCR:pMHC vary depending on their combinations. A plethora of studies demonstrated that the response characteristics of T cells including the strength of TCR:pMHC affinity qualitatively affect the TCR signal, T cell activation, and ensuing biological outcomes (9, 10). Especially, the affinities of self-reactive TCRs are generally lower compared with those of TCRs reactive to foreign antigens (11), which can partly be explained by the negative selection of highly self-reactive T cells in the thymus. Thus, self-reactive T cells are supposed to have different response characteristics from T cells reactive to foreign antigens. However, it remains to be elucidated whether and how T cells with such diverse response characteristics are differentially regulated.

Engagement of PD-1 with either of its two ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, during antigen stimulation leads to the recruitment of the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2, which dephosphorylates signaling molecules including CD3ζ, ZAP70, and CD28 (12–14). PD-1 has been postulated to lower the responsiveness of T cells to antigen stimulation and suppress TCR-induced events uniformly because PD-1 inhibits TCR-proximal signaling. However, we have recently found that the suppressive effects of PD-1 on TCR-induced gene expression differ across different genes (15). By quantifying the half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of antigen as the relationship between change in gene expression and TCR signal strength, we demonstrated that TCR signal strength required for the induction of genes varies across different genes and that PD-1 preferentially inhibits the up-regulations of genes that require stronger TCR signal (15). As each T cell has its own response characteristics, inducibility of genes likely differs across different T cells. Accordingly, the inhibitory effects of PD-1 are also expected to differ across different T cells.

In this study, we investigated whether and how factors that alter the responsiveness of T cells to antigenic stimuli influence the inhibitory effects of PD-1. By comparing T cells bearing TCRs with different affinities to pMHC, we demonstrated that PD-1 inhibits the expression of TCR-inducible genes more efficiently in the activation of T cells expressing TCRs with lower affinity to pMHC. We also tested peptides with different affinities to TCR and found that PD-1 inhibits the expression of TCR-inducible genes more efficiently when T cells are stimulated by peptides with lower affinity to TCR. In contrast, the manipulation of the affinity of peptides to MHC and the expression level of MHC did not affect the PD-1 sensitivity at all, although they markedly altered the dose responsiveness of T cells by changing the efficiency of pMHC formation. These results suggest that the strength of individual TCR signal is the critical determinant of PD-1 sensitivity. We further demonstrated that T cells with low-affinity to tumor-antigen were preferentially expanded in PD-1–deficient mice upon inoculation of tumor cells. Our current findings indicate that PD-1 regulates the quality of T cell responses by preferentially suppressing low-affinity T cells.

Results

PD-1 Preferentially Suppresses the Activation of T Cells with Lower Affinity to Antigens.

Each TCR recognizes a corresponding cognate peptide presented on the MHC molecule. The TCR that recognizes the cognate pMHC is not necessarily limited to a single TCR of a unique amino acid sequence, but a variety of TCRs can recognize the same pMHC (16, 17). These TCRs differ in their affinities to pMHC, and T cells with higher-affinity TCRs respond to pMHC predominantly over those with lower-affinity TCRs in theory. To elucidate whether and how T cells expressing TCRs with different affinities to pMHC are differentially regulated by PD-1, we employed the 1MOG9 TCR that recognizes the peptide of myeline oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (amino acids 35 through 55, pMOG35–55) in the context of I-Ab, murine MHC class II (18). Introduction of certain amino acid substitutions in the complementarity-determining region of 1MOG9 TCR β-chain has been reported to result in the changes in its affinity to pMOG35–55/I-Ab complex (19, 20). MethA murine fibrosarcoma cells transduced with I-Ab were used as APCs to stimulate BW1100.129.237 murine T lymphoma cells reconstituted with 1MOG9 TCR variants (E100S, E100T, G107A/E100S, G107S/E100S, G107A/E100T, and G107S/E100T) that recognize pMOG35–55/I-Ab with different affinities (Fig. 1A). T cells expressing TCRs with higher affinity to pMHC were confirmed to produce higher amount of IL-2 upon stimulation (Fig. 1B). We stimulated these T cells with the varying concentrations of pMOG35–55 in the presence or absence of anti–PD-L1 blocking Ab to evaluate the EC50 and PD-1 sensitivity of TCR-inducible genes. We selected test genes that are moderately and weakly sensitive to PD-1 yet inducible in the activation of low-affinity T cells based on our former analyses (15). T cells stimulated for 2, 4, and 8 h were pooled for the quantification of messenger RNA (mRNA) of test genes to preclude possible effects resulting from differences in expression kinetics.

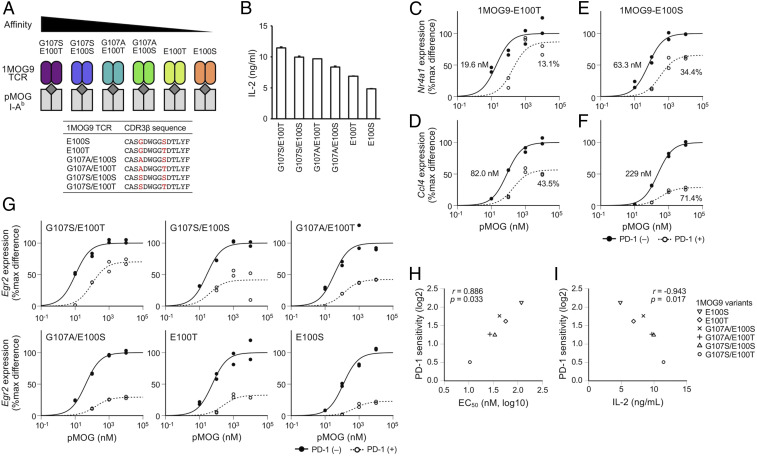

Fig. 1.

Preferential inhibition of TCR-induced gene expression in T cells expressing TCRs with lower affinity to pMHC by PD-1. (A) Schematic representations of 1MOG9 TCR variants that have different affinities to I-Ab presenting pMOG35–55. BW1100.129.237 T cells expressing each 1MOG9 TCR variants were stimulated by coculturing with APCs pulsed with pMOG35–55. Amino acid sequences of the complementarity-determining region 3 of TCR β chain (CDR3β) are shown for 1MOG9 TCR variants. (B) IL-2 production from T cells expressing 1MOG9 TCR variants upon stimulation with pMOG35–55 (10 μM). Data indicate the mean + SD of technical duplicates in one representative experiment. (C–F) Dose–response curves of Nr4a1 (C and E) and Ccl4 (D and F) in the activation of T cells expressing 1MOG9-E100T TCR (C and D) or 1MOG9-E100S TCR (E and F) in the presence or absence of PD-1 engagement. EC50 and %inhibition values are indicated. (G) Dose–response curves of Egr2 in the activation of T cells expressing six different 1MOG9 TCR variants with or without PD-1 engagement. (H and I) Scatterplots showing the correlations between PD-1 sensitivity and EC50 of Egr2 (H) and between the IL-2 producing capacity and PD-1 sensitivity of Egr2 (I) in the activation of T cells expressing six different 1MOG9 TCR variants. Representative data of two (B and I) and four (C–H) independent experiments are shown.

When we stimulated T cells expressing 1MOG9-E100T TCR (BW-1MOG9-E100T), which has the second-lowest affinity to pMOG35–55/I-Ab among tested variants, the EC50 values of Nr4a1 and Ccl4 were 19.6 and 82.0 nM, respectively. In accordance with our former observation that PD-1 preferentially inhibits the expression of high-EC50 genes (15), Ccl4 expression was substantially suppressed by PD-1 (%inhibition, 43.5; PD-1 sensitivity, 20.82), while Nr4a1 expression was resistant to PD-1 (%inhibition, 13.1; PD-1 sensitivity, 20.20) (Fig. 1 C and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). On the other hand, Nr4a1 expression was considerably inhibited by PD-1 (%inhibition, 34.4; PD-1 sensitivity, 20.61) when T cells expressing 1MOG9-E100S TCR were used (Fig. 1E). In addition, Ccl4 expression was more robustly inhibited by PD-1 (%inhibition, 71.4; PD-1 sensitivity, 21.81) in the activation of BW-1MOG9-E100S cells (Fig. 1F). Thus, the inhibitory effect of PD-1 on TCR-induced gene expression was found to vary between T cells with different affinities to antigen.

As the affinity of 1MOG9-E100S TCR to pMOG35–55/I-Ab is lower than that of 1MOG9-E100T TCR, Nr4a1 and Ccl4 expression required higher doses of pMOG35–55 in the activation of BW-1MOG9-E100S cells. Accordingly, the EC50 values of pMOG35–55 for Nr4a1 and Ccl4 expression were higher in the activation of BW-1MOG9-E100S cells compared with BW-1MOG9-E100T cells (Nr4a1, 63.3 versus 19.6 nM; Ccl4, 229 versus 82.0 nM) (Fig. 1 C–F). These results suggest that the stronger PD-1 effect is due to the less efficient expression of TCR-inducible genes in the activation of BW-1MOG9-E100S cells.

Then, we tested six different 1MOG9 TCR variants and found that PD-1 inhibited Egr2 expression to variable degrees in T cells with different 1MOG9 TCR variants (Fig. 1G). We also found that the EC50 of Egr2 was higher in the activation of T cells expressing lower-affinity 1MOG9 TCR variants (Fig. 1G). Remarkably, PD-1 sensitivity of Egr2 showed strong positive and negative correlations to EC50 of Egr2 and the IL-2–producing capacity, respectively, in the activation of these T cells (Fig. 1 H and I). When we analyzed the TCR-induced expression of 4–1BB protein at a later time point (24 h after the initiation of stimulation), a strong positive correlation was also observed between PD-1 sensitivity and EC50 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Besides, we confirmed that MHC class I–restricted T cells also have a similar tendency by comparing BW-OT-1 and BW-B3 cells whose TCRs recognize the same antigen (SAINFEKL) with high and low affinity, respectively, in an MHC class I–restricted manner (SI Appendix, Fig. S3) (21).

Collectively, genes with low EC50 such as Nr4a1 mostly resist PD-1–mediated inhibition in high-affinity T cells, whereas they become sensitive to PD-1 in low-affinity T cells. On the other hand, genes with high EC50 such as Ccl4 show a substantial sensitivity to PD-1 even in high-affinity T cells, and their PD-1 sensitivity is further increased in low-affinity T cells. Thus, PD-1 inhibits the expression of TCR-inducible genes more strongly in T cells with lower-affinity TCRs.

PD-1 Preferentially Suppresses T Cell Responses against Low-Affinity Peptides.

As multiple TCRs can recognize a single peptide, a single TCR can recognize multiple peptides (22, 23). Accordingly, multiple cognate peptides with different affinities can be generated for each TCR by introducing amino acid substitutions on the known cognate peptide, which are collectively termed as altered peptide ligands (APLs) (24). APLs differ in their affinities to TCRs, MHCs, or both. Peptides with higher affinities to TCRs activate T cells at smaller doses compared with those with lower affinity to TCRs in theory. Based on the results obtained with TCR variants (Fig. 1), we hypothesized that PD-1 may inhibit T cell activation more efficiently when T cells are stimulated with peptides with lower affinities to TCRs. To test this hypothesis, we utilized the OT-1 TCR that recognizes the peptide of chicken ovalbumin (amino acids 257 through 264, pOVA257–264) in the context of H-2Kb, murine MHC class I (25). We selected six APLs of pOVA257–264 (N4, A2, Y3, Q4, T4, and V4 peptides), which differ in their affinities to OT-1 TCR but not to H-2Kb (Fig. 2A) (26, 27). BW-OT-1 cells were confirmed to produce higher amount of IL-2 upon stimulation with higher-affinity APLs (Fig. 2B).

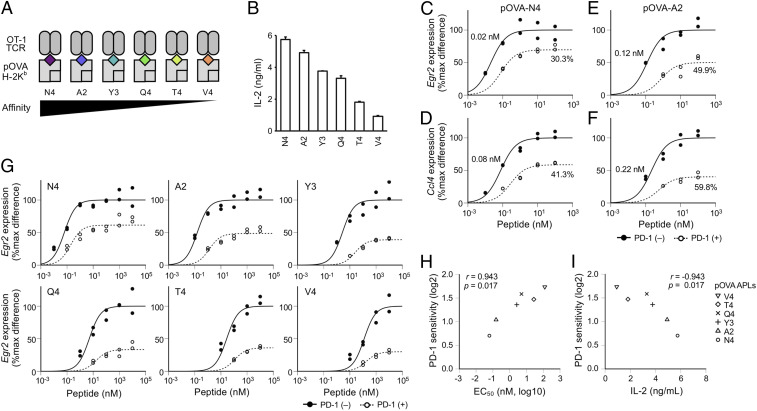

Fig. 2.

Preferential inhibition of TCR-induced gene expression upon stimulation with low-affinity peptides by PD-1. (A) Schematic representations of pOVA257–264 APLs that have different affinities to OT-1 TCR. BW-OT-1 cells were stimulated by coculturing with APCs pulsed with each pOVA257–264 APL. (B) IL-2 production from BW-OT-1 cells upon stimulation with pOVA257–264 APLs (10 μM). Data indicate the mean + SD of technical duplicates in one representative experiment. (C–F) Dose–response curves of Egr2 (C and E) and Ccl4 (D and F) in the activation of BW-OT-1 cells with N4 (C and D) or A2 (E and F) in the presence or absence of PD-1 engagement. EC50 and %inhibition values are indicated. (G) Dose–response curves of Egr2 in the activation of BW-OT-1 cells with six different pOVA257–264 APLs in the presence or absence of PD-1 engagement. (H and I) Scatterplots showing the correlations between PD-1 sensitivity and EC50 of Egr2 (H) and between the IL-2 producing capacity and PD-1 sensitivity of Egr2 (I) in the activation of BW-OT-1 cells with six different pOVA257–264 APLs. Representative data of two (B and I) and four (C–H) independent experiments are shown.

We stimulated BW-OT-1 cells with N4 and A2 peptides that have the highest and the second-highest affinities to OT-1 TCR, respectively, and evaluated the PD-1 sensitivities of high- (Ccl4) and low- (Egr2) EC50 genes (15). When BW-OT-1 cells were stimulated with N4 peptide, Ccl4 expression was substantially inhibited by PD-1 while the inhibition of Egr2 was limited (Fig. 2 C and D). The inhibitory effect of PD-1 on Egr2 expression was markedly increased when A2 peptide was used to stimulate BW-OT-1 cells (Fig. 2E). In addition, the PD-1 sensitivity of Ccl4 was also higher in the activation of BW-OT-1 cells with A2 peptide compared with N4 peptide (Fig. 2F). Thus, the inhibitory effect of PD-1 on TCR-induced gene expression was found to differ when T cells were stimulated with peptides with different affinities to TCRs.

As the affinity of A2 peptide to OT-1 TCR is lower than that of N4 peptide, Egr2 and Ccl4 expression required higher doses of A2 peptide in the activation of BW-OT-1 cells. Accordingly, the EC50 values of A2 peptide for Egr2 and Ccl4 expression were higher than those of N4 peptide in the activation of BW-OT-1 cells (Egr2, 0.12 versus 0.02 nM; Ccl4, 0.22 versus 0.08 nM) (Fig. 2 C–F). These results suggest that the stronger inhibitory effect of PD-1 is due to the less efficient expression of TCR-inducible genes in the activation of BW-OT-1 cells with A2 peptide.

Then, we tested six different APLs and found that PD-1 inhibited Egr2 expression to variable degrees in the activation of BW-OT-1 cells with different APLs (Fig. 2G). We also found that the EC50 of Egr2 was higher in the activation of T cells with lower-affinity APLs (Fig. 2G). As is the case with TCR variants, PD-1 sensitivity of Egr2 showed strong positive and negative correlations to EC50 of Egr2 and the IL-2–producing capacity, respectively, in the activation of T cells with different APLs (Fig. 2 H and I). A strong positive correlation was also observed between PD-1 sensitivity and EC50 of 4–1BB expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). In addition, we confirmed that MHC class II–restricted T cells also have a similar tendency by stimulating 2B4.11 T hybridoma cells whose TCR recognizes the peptide of moth cytochrome c (amino acids 88 through 103, pMCC88–103) in the context of I-Ek (28) with high- and low-affinity APLs (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) (29).

These results indicate that the inducibility of genes in individual T cells varies depending on the TCR affinities of peptides to which T cells respond and that PD-1 inhibits TCR-induced gene expression more efficiently when T cells were stimulated with lower-affinity peptides.

The Stability of pMHC Affects the EC50 but Not the PD-1 Sensitivity of TCR-Inducible Genes.

In addition to TCR:pMHC affinity, various factors can affect EC50 of genes. We next investigated the possible effects of the affinity between peptides and MHC that affects EC50 of genes by altering the stability of pMHC. Because peptides with lower affinity to MHC form less stable complexes with MHC compared to peptides with higher affinity to MHC, larger amounts of peptides are required to supply the equivalent amounts of pMHC to T cells compared with peptides with higher affinity to MHC. Therefore, the EC50 of TCR-inducible genes likely increases as the affinity of peptides to MHC decreases.

In addition to above-mentioned APLs that differ in their affinities to the TCR of 2B4.11 T cells, a series of APLs with different affinities to I-Ek has been reported (30). We used six APLs that differ in their affinities to I-Ek but retain amino acid residues at TCR contact position, P3, P5, and P8 (23, 29). We stimulated 2B4.11 T cells with the varying concentrations of these APLs and calculated the EC50 and the PD-1 sensitivity of Egr2 (Fig. 3A). As predicted, the EC50 of these APLs for Egr2 expression was substantially varied. In contrast, PD-1 sensitivity was comparable across T cell activation with these APLs (Fig. 3 A and B). A comparable PD-1 sensitivity was also observed when 4–1BB expression was used as a readout (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). In addition, we confirmed that MHC class I–restricted T cells also have a similar tendency by stimulating BW-OT-1 cells with APLs having high and low affinities to H-2Kb (SI Appendix, Fig. S7) (31).

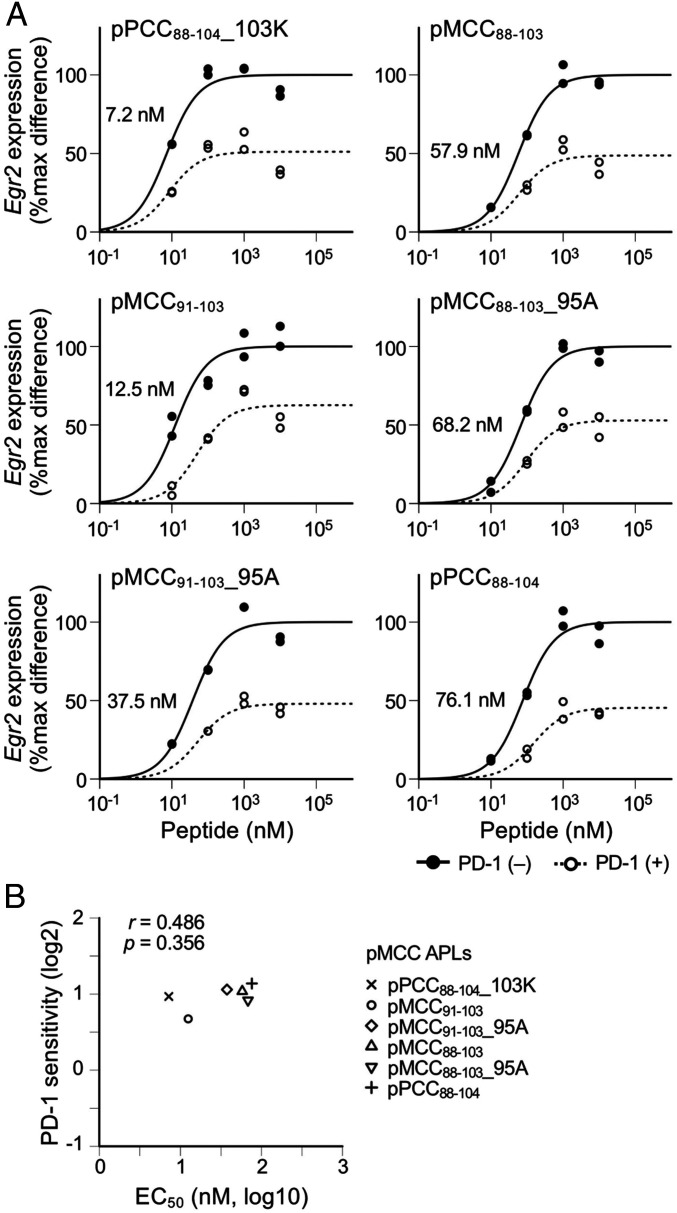

Fig. 3.

No substantial effect of pMHC stability on the inhibitory effects of PD-1 on TCR-induced gene expression. (A) Dose–response curves of Egr2 expression in the activation of 2B4.11 T cells with six different pMCC88–103 APLs in the presence or absence of PD-1 engagement. EC50 values are indicated. (B) Scatterplot showing the correlation between PD-1 sensitivity and EC50 of Egr2 in the activation of 2B4.11 T cells with six different pMCC88–103 APLs. Representative data of two independent experiments are shown.

These results clearly indicate that the signal strength through individual TCR but not the stability of pMHC is the key determinant of PD-1 sensitivity. Since changes in EC50 of genes directly dictate the changes in the strength of TCR required for their expression in the activation of T cells with different TCR:pMHC affinities (Figs. 1 and 2), EC50 of genes reasonably correlated with PD-1 sensitivity in such experimental conditions. On the other hand, the affinity of peptides to MHC affects the occupancy of MHC with cognate peptides but not the strength of individual TCR signal, which accounts for the lack of correlation between EC50 and PD-1 sensitivity of genes in the comparison of peptides with different affinities to MHC (Fig. 3B).

MHC Expression Level Affects the EC50 but Not the PD-1 Sensitivity of TCR-Inducible Genes.

In addition to the affinity between peptides and MHCs, the amounts of MHCs on APCs can also affect the efficiency of pMHC formation. The expression levels of both MHC class I and MHC class II are variable and serve as critical determinants of immune responses (32). APCs such as dendritic cells and B cells augment their expression of MHC class II upon activation and cytokines such as IFN-γ augment MHC class I on tumor cells to enhance the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy (33, 34). When APCs with lower MHC expression were used, larger amounts of peptides are required to supply the equivalent amounts of pMHC to T cells compared with APCs with higher MHC expression. Therefore, the EC50 of TCR-inducible genes likely increases as the MHC expression level decreases.

To investigate the possible effects of MHC expression level on PD-1 function, we prepared MethA cells expressing MHC to variable degrees and used them as APCs to stimulate DO11.10 T hybridoma cells that respond to the peptide of chicken ovalbumin (amino acids 323 through 339, pOVA323–339) in the context of I-Ad (Fig. 4A). As expected, the EC50 of Egr2 showed a clear negative correlation to the expression levels of MHC (Fig. 4 B and C). In contrast, PD-1 sensitivity was comparable across T cell activation with APCs expressing MHC to different degrees (Fig. 4 B and D). We introduced the IL-2-EGFP reporter construct into DO11.10 T cells and evaluated the EC50 and PD-1 sensitivity of the reporter in each condition (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 A and B). Again, PD-1 sensitivity of the reporter was comparable across T cell activation with APCs expressing MHC to different degrees, whereas the EC50 of the reporter showed a clear negative correlation to the expression levels of MHC (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 C and D). In addition, we confirmed that MHC class I–restricted T cells also have a similar tendency by stimulating BW-OT-1 cells with APCs expressing high and low levels of H-2Kb (SI Appendix, Fig. S9).

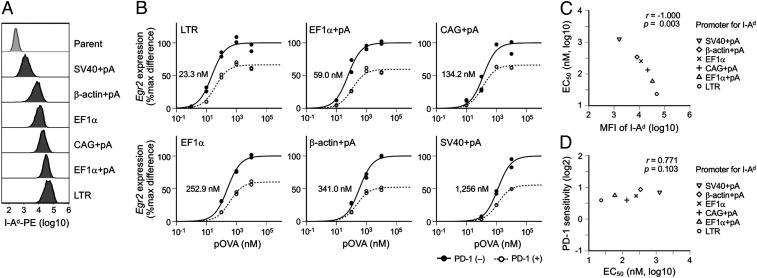

Fig. 4.

No substantial effect of MHC expression level on the inhibitory effects of PD-1 on TCR-induced gene expression. (A) Representative histogram plots showing the expression levels of I-Ad on APCs introduced with I-Ad by using retroviral vectors with indicated promoters with or without polyadenylation (pA) signal. (B) Dose–response curves of Egr2 expression in the activation of DO11.10 T cells with pOVA323–339 using MethA cells expressing I-Ad at six different levels as APCs in the presence or absence of PD-1 engagement. EC50 values are indicated. (C and D) Scatterplots showing the correlations between the EC50 of Egr2 and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of I-Ad (C) and between EC50 and PD-1 sensitivity of Egr2 (D) in the activation of DO11.10 T cells using APCs expressing I-Ad at six different levels. Representative data of two independent experiments are shown.

Thus, the MHC expression level of APCs affects EC50 but not PD-1 sensitivity of TCR-inducible genes. These results further support the idea that the strength of individual TCR signal but not the efficiency of pMHC formation is the key determinant of PD-1 sensitivity.

PD-1 Preferentially Suppresses Low-Affinity T Cells In Vivo.

The aforementioned results of in vitro experiments clearly demonstrate that PD-1 per se inhibits the activation-induced gene expression more efficiently in T cells with lower affinities to antigens. We tested whether this preference can also be observed in T cell responses in vivo or not.

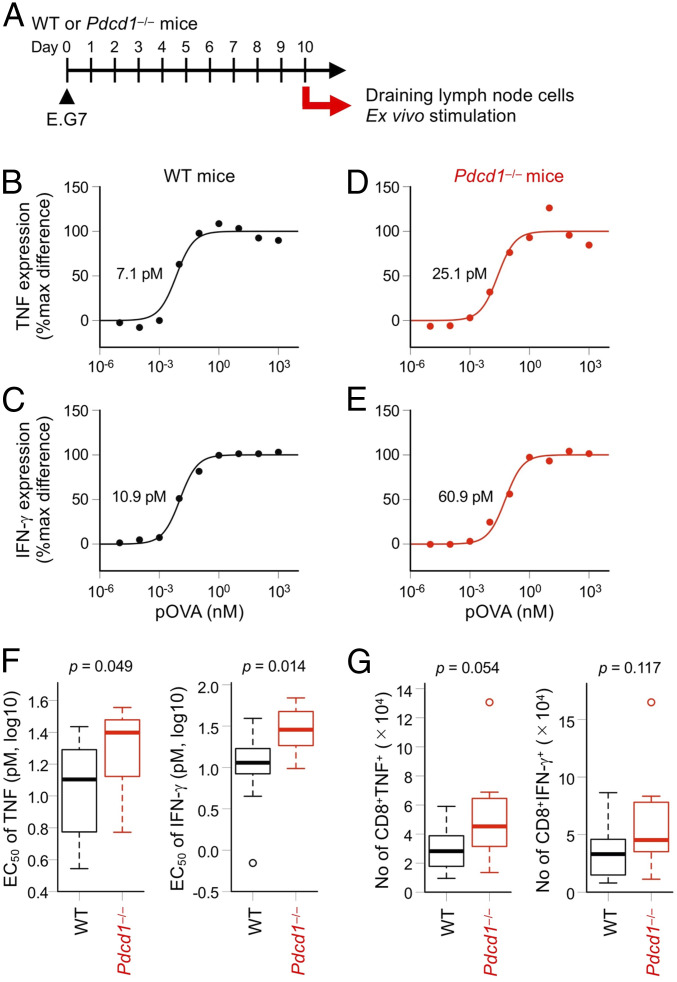

If PD-1 preferentially inhibits the activation of lower-affinity T cells, lower-affinity T cells are expected to expand preferentially in the absence of PD-1 compared to higher-affinity T cells. We inoculated E.G7 mouse thymoma cells that express OVA in C57BL/6N wild-type (WT) and PD-1–deficient (Pdcd1−/−) mice and collected the draining lymph node (dLN) cells 10 d later. The dLN cells from each mouse were stimulated with varying doses of H-2Kb–restricted OVA peptide (pOVA257–264) ex vivo to evaluate the EC50 of TNF and IFN-γ expression (Fig. 5 A–E and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). The EC50 of TNF and IFN-γ was significantly higher in T cells from Pdcd1−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 5F). The numbers of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells with TNF- and IFN-γ–producing capacities also showed the tendency to be higher in Pdcd1−/− mice (Fig. 5G). Since the expression levels of other inhibitory coreceptors such as LAG-3, TIM-3, KLRG1, and CD160 were not increased in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells from Pdcd1−/− mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S11), the higher EC50 of TNF and IFN-γ in Pdcd1−/− T cells was not due to the augmented expression of other inhibitory coreceptors in the absence of PD-1. These results strongly suggest that the larger number of lower-affinity T cells are allowed to be activated in the dLNs of Pdcd1−/− mice, resulting in the decrease of the overall affinity of T cells to the antigen. Thus, PD-1 likely suppresses low-affinity T cells preferentially in vivo.

Fig. 5.

Preferential suppression of low-affinity T cells by PD-1 in vivo. (A) Experimental design. WT and Pdcd1−/− mice (n = 11 each) were subcutaneously inoculated with OVA-expressing E.G7 thymoma cells. dLN cells were collected 10 d later and stimulated with the varying doses of pOVA257–264 for 6 h. CD8+ T cells expressing TNF and IFN-γ were detected by flow cytometry. (B–E) Representative dose–response curves of TNF (B and D) and IFN-γ (C and E) in the ex vivo activation of tumor-specific T cells collected from WT (B and C) and Pdcd1−/− (D and E) mice. EC50 values are indicated. (F) EC50 of TNF (Left) and IFN-γ (Right) of tumor-specific T cells collected from WT and Pdcd1−/− mice. (G) Absolute numbers of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells that can produce TNF (Left) and IFN-γ (Right) calculated by the frequency of cells expressing each molecule at the highest dose of pOVA257–264. Thick horizontal lines denote median values, boxes extend from the 25th to the 75th percentile of each group's distribution of values, dashed vertical lines denote adjacent values within 1.5 interquartile range, and open circles denote observations outside the range of adjacent values (F and G). Representative data of three independent experiments are shown.

Discussion

The antigen specificity of T cells is exceedingly diverse, and T cells that respond to a variety of peptides with varying affinities exist in our body. The antigen specificity and affinity of T cells need to be strictly regulated for the rapid clearance of pathogens and the avoidance of tissue damage due to cross-reactivity. However, it remains largely unknown how T cells with different antigen specificity and affinity are differentially regulated. We have recently found that PD-1 preferentially inhibits low-inducible genes in T cell activation (15), which suggests that PD-1 may inhibit the expression of TCR-inducible genes differently in high- and low-affinity T cells. However, whether and to what degree TCR:pMHC affinity really affects inducibility and PD-1 sensitivity of genes in the activation of T cells remained uncertain. By analyzing inducibility and PD-1 sensitivity of genes in various conditions, we demonstrated here that subtle changes in TCR:pMHC affinity directly influence the inducibility and PD-1 sensitivity of genes in T cell activation. Accordingly, preferential expansion of T cells with low-affinity to tumor-antigen were observed in Pdcd1−/− mice. Despite intensive studies, properties of T cells that are activated to destroy tumor cells or self-tissues in anti–PD-1 therapy are only vaguely understood. Evaluation of the affinities of T cells and the accurate quantification of PD-1–sensitive and –resistant genes in each T cell may facilitate the identification of the T cells that are responsible for the eradication of tumors in cancer immunotherapy or destruction of self-tissues in autoimmunity.

Self-reactive TCRs generally have lower affinities to pMHC compared with TCRs reactive to foreign antigens (11). Therefore, self-reactive T cells can be more liable to PD-1–mediated suppression, which may account for the frequent development of irAEs in human patients receiving anti–PD-1 therapy (7, 8) and the spontaneous development of autoimmune diseases in Pdcd1−/− mice (35–38). The cross-reactivity of pathogen-specific T cells to self-antigens is one of the major triggers of autoimmune diseases (39). Because the affinity of such cross-reaction is generally lower than the original reaction, PD-1 may suppress such cross-reactivity to increase the specificity of the T cell responses and prevent autoimmunity. TCRs specific to tumor-associated antigens with the germline amino acid sequence are also expected to have lower affinities to pMHC (40) and thus are expected to be suppressed by PD-1 with high efficiency.

In contrast to the affinity of TCR:pMHC, the affinity of peptides to MHC and the surface expression levels of MHC affected EC50 but not PD-1 sensitivity of TCR-inducible genes, which indicates that the strength of individual TCR signal but not the efficiency of pMHC formation is the key determinant of PD-1 sensitivity. Accumulating evidence indicates that neoantigens bearing tumor-associated somatic mutations are the preeminent targets of tumor-specific T cells in anti–PD-1 therapy (41–43). Some mutations affect the TCR:pMHC interaction while other mutations affect the affinity of peptides to MHC. Mutations that increase the affinity of peptides to MHC is expected to decrease the EC50 of peptides, whereas such mutations are expected not to affect the PD-1 sensitivity as seen above, which may explain the high efficacy of anti–PD-1 therapy on tumors with high mutation load. Riaz et al. reported the expansion of tumor-specific T cell clones in cancer patients receiving anti–PD-1 therapy (44). In the current study, we observed a preferential expansion of T cells with low-affinity to tumor-antigen in Pdcd1−/− mice. Further analyses are needed to evaluate the relative contributions of high- and low-affinity T cells in the eradication of tumors upon PD-1 blockade. Especially, effects of PD-1 on the acquisition of cytotoxic capacity, memory phenotype, exhausted phenotype, or regulatory function by high- and low-affinity T cells in the later phase of anti-tumor immune responses are of great interest.

In the present study, we investigated the effect of TCR:pMHC affinity on PD-1 function by using highly controlled experimental systems and demonstrated that PD-1 preferentially suppresses low-affinity T cells. In addition to TCR:pMHC affinity, a variety of factors affects the response characteristics of T cells as well as PD-1 function, which may limit the generalizability of the current findings. Especially, the expression levels of PD-1 and the other stimulatory and inhibitory coreceptors differ across different T cells, and the amount of PD-1 and the presence of the other coreceptors have been shown to influence the inhibitory efficiency of PD-1 considerably (45–50). Since PD-1 expression on T cells depends on antigen stimulation, PD-1 expression is induced more strongly when T cells are stimulated with higher doses of antigens or higher-affinity antigens under nonsaturating conditions. Thus, PD-1 expression levels need to be considered to understand its actual impact on high- and low-affinity T cells. However, the relationships between PD-1 expression and TCR affinity are rather controversial. Martínez-Usatorre et al. reported that OT-1 T cells express PD-1 more strongly upon stimulation with the high-affinity APL (N4) compared to low-affinity APL (T4) (51). However, they detected a comparable level of PD-1 expression on OT-1 and OT-3 T cells, although the affinity of OT-3 TCR to pOVA257–264/H-2Kb is lower than that of OT-1 TCR (51). Dougan et al. also observed a similar PD-1 expression on high- and low-affinity T cells specific to the same melanoma antigen (52). In contrast, Billeskov et al. reported that CD4+ T cells with higher functional avidity had lower PD-1 expression (53). Thus, PD-1 expression level is not necessarily high on high-affinity T cells, and further studies are needed for the deeper understanding of the regulatory mechanisms of PD-1 expression.

The successful eradication of tumors and the concomitant development of irAEs in human patients receiving anti–PD-1 therapies highlighted the significance of PD-1 in the regulation of tumor-specific as well as self-reactive T cells. However, it is largely unknown what determines the PD-1 sensitivity of T cells and what types of T cells actually expand to destroy tumor cells or self-tissues upon PD-1 blockade. In the current study, we demonstrated that the affinity of TCR:pMHC is the critical determinant of PD-1 sensitivity. In addition to the affinity of TCR:pMHC, various factors likely alter the responsiveness of T cells and thus PD-1 sensitivity of T cells. Precise and deeper understandings of the functional characteristics of PD-1 will support the future development of effective and safe immunotherapies.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

DO11.10 and 2B4.11 T hybridoma, PD-1–deficient BW1100.129.237 (BWdP) (50), C1498 (ATCC), MethA, and E.G7 cells were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium 1640 (Gibco), supplemented with 10% (volume/volume) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biowest), 0.5 mM Monothioglycerol (Wako), 2 mM L-alanyl-L-glutamine dipeptide (Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin (Nacalai Tesque), and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Nacalai Tesque). Plat-E and 293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Invitrogen) and supplemented with 10% (volume/volume) FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. PD-L1–deficient MethA (MethAdL) cells were generated as described (50). Briefly, the plasmid vector that expresses Cas9 and guide RNA (gRNA) was transfected into MethA cells by using FuGENE HD (Promega). Cells that have lost PD-L1 expression were sorted by using cell sorter (MoFlo XDP, Beckman Coulter). A clone of cells was obtained by limiting dilution, and the disruption of PD-L1 gene and the lack of PD-L1 expression were confirmed by sequencing and flow cytometry, respectively.

Mice.

C57BL/6N mice were purchased from Japan SLC. C57BL/6N-Pdcd1−/− mice were generated by introducing Cas9 mRNA and gRNA into C57BL/6N zygotes by electroporation as previously described (54). The nucleotide sequences of the gRNA and the Pdcd1 gene of the Pdcd1−/− mice are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S12. The first generation of mosaic mice was crossed with C57BL/6N WT mice to obtain heterozygous mice, and heterozygous mice were crossed to obtain homozygous mice. All mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in environmentally controlled clean rooms. Age (7 to 11 wk)- and sex-matched mice were used in each experiment. All mouse protocols were approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of the University of Tokyo. All experimental procedures complied with institutional regulations in accordance with the Act on Welfare and Management of Animals and related guidelines in Japan.

Retroviral Gene Transduction.

Fragments of complementary DNA (cDNA) were amplified by PCR and cloned into retroviral expression plasmid vectors with neomycin-resistant gene, puromycin-resistant gene, blasticidin-resistant gene, and Zeocin-resistant gene (55). To control the expression level of I-Ad, cDNA fragments encoding the α and β chains of I-Ad were cloned into the retroviral expression plasmid vectors with EF-1α promoter, CAG promoter, β-actin promoter, SV40 promoter, and MC1 promoter (56). IL2-EGFP reporter vector, pIL2Rmp-EGFP, was generated from pTRpuro-E2-crimson (15) by replacing the artificial TCR response element, E2-crimson, and puromycin resistance genes with the two sets of Il2 promoter sequence (55 to 302 bp upstream of the mouse Il2 transcription start site), EGFP, and mycophenolic acid-resistance genes, respectively.

Plasmids were transfected using the FuGENE HD (Promega) into Plat-E cells cultured in DMEM, high glucose (GIBCO) supplemented with 20% (volume/volume) FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and supernatants containing viruses were used to transduce genes into target cells. For the retroviral gene transduction into E.G7 cells, 293T cells were transfected with retroviral expression plasmids together with packaging plasmids (pN8epsilon-gag/pol and pN8epsilon-VSVG) (57), and supernatants containing viruses were used to transduce genes into target cells. Infected cells were selected with G418 (Wako), puromycin (Wako), Blasticidin S (InvivoGen), or Zeocin (InvivoGen) or by cell sorting (MoFlo XDP). BWdP cells were reconstituted with CD3δ, CD3ζ, CD28, PD-1, and indicated TCR together with CD8α and CD8β for BW-OT-1 and BW-B3 cells or CD4 for BW-1MOG9 variant cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). CD86, CD48, ICAM-1, and PD-L1 were introduced into MethAdL cells together with I-Ab (MethA-I-Ab), I-Ad (MethA-I-Ad), or I-Ek (MethA-I-Ek) and used for the stimulation of BW-1MOG9 variant, DO11.10 T, or 2B4.11 T cells, respectively. PD-L1 and CD86 were introduced into C1498 and used for the stimulation of BW-OT-1 and BW-B3 cells in Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Figs. S3, S4, and S7. CD86, PD-L1, and H-2Kb were introduced into MethAdL cells (MethA-H-2Kb) and used for the stimulation of BW-OT-1 cells in SI Appendix, Fig. S9. CD4, CD28, and IL2-EGFP reporter were introduced into DO11.10 T hybridoma cells and a high-responder clone was obtained by limiting dilution (SI Appendix, Fig. S13).

Antigen Stimulation of T Cells.

T cells were stimulated by coculturing with APCs pulsed with the corresponding peptides (>95% purity) as described previously (15). BW-1MOG9 variant, BW-B3, 2B4.11 T, and DO11.10 T cells were stimulated by using MethA-I-Ab, C1498, MethA-I-Ek, and MethA-I-Ad cells as APCs, respectively. For the stimulation of BW-OT-1 cells, we used MethA-H-2Kb cells in SI Appendix, Fig. S9 and C1498 cells in Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Figs. S3, S4, and S7 as APCs. Amino acid sequences of peptides are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1. Anti–PD-L1 Ab (0.5 μg/mL, clone 1-111A) (58) or its isotype control Ig (rat IgG2a, clone RTK2758, Biolegend) was added to stimulate T cells in the absence or presence of PD-1 engagement, respectively. For qPCR analyses, T cells stimulated for 2, 4, and 8 h were mixed. The expression levels of 4–1BB and EGFP were analyzed 24 h after the initiation of the stimulation. The concentration of IL-2 in the culture supernatant was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Biolegend).

qPCR.

Cells collected at 2, 4, and 8 h after the initiation of coculture were mixed, and T cells were purified by automated magnetic-activated cell sorting system (autoMACS, Miltenyi) according to the manufacture’s instruction. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and subjected to reverse transcription using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Expression of gene was evaluated by qPCR using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on a 7900-HT Fast Real-Time PCR (Applied Biosystems) and normalized to the amount of Cd3e mRNA, as described before (15).

Flow Cytometric Analysis.

Single-cell suspensions were stained with indicated Abs, and data were obtained with Gallios (Beckman Coulter) and analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star, Inc.). Abs used in this study are listed in SI Appendix, Table S2. For the intracellular staining of TNF and IFN-γ, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Wako) and permeabilized with 0.1% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich) in phosphate-buffered saline (Nacalai Tesque). Dead cells were distinguished by using propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) and Ghost Dye Violet 510 (Tonbo Biosciences) for the analyses of nonfixed and fixed cells, respectively.

Calculation of EC50, PD-1 Sensitivity, %inhibition, and %max difference.

Dose–response curves obtained from the qPCR or flow cytometry were fitted to the following equation:

where [x] is dose of peptide, E is expression level at the dose of peptide, Emax is estimated maximal expression level, E0 is expression level without peptide, and EC50 is half of maximal effective dose of peptide. Emax and EC50 were estimated by using R-function nls.lm (59).

PD-1 sensitivity, %inhibition, and %max difference were calculated using the following formulae (SI Appendix, Fig. S1):

EC50 of Tumor-Specific T cells.

EC50 of TNF and IFN-γ in tumor-specific T cells was measured according to the previous report (53). CD40L was introduced into E.G7 cells to enhance the immunogenicity (60). Each mouse was subcutaneously inoculated with a total of 4 × 106 E.G7-CD40L cells at two different sites on hind flank. Brachial, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes were collected 10 d later. Lymph node cells (1 × 106 cells/well) were stimulated with the indicated dose of pOVA257–264 in the presence of anti–PD-L1 Ab (0.5 μg/mL, 1-111A) in tissue culture–treated 96-well round-bottom plates. Brefeldin A (Biolegend) was added at 1 h after the initiation of the stimulation, and cells were analyzed by flow cytometry 5 h after the addition of brefeldin A. The data of one Pdcd1−/− mouse that did not show pOVA dose-dependent expression of TNF and IFN-γ was excluded.

To evaluate the expression levels of inhibitory coreceptors on tumor-reactive T cells, we first purified CD8+ T cells from dLN of tumor-inoculated mice by autoMACS using biotinylated Abs against CD4, B220, and CD11b (Biolegend) and anti-Biotin MicroBeads (Miltenyi). Purified CD8+ T cells were stained with pOVA257–264/H-2Kb-tetramer (MBL) and Abs against inhibitory coreceptors (SI Appendix, Table S2) and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis.

The strength of a monotonic relationship between two variables was calculated as Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r). For multiple comparisons, P values were adjusted by Bonferroni correction. Unpaired Student’s t tests were used for comparisons between two groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. T. Kitamura (Plat-E cells), L. Ignatowicz (BW1100.129.237 cells), T. Honjo (DO11.10 T, 2B4.11 T, MethA, E.G7, and 293T cells), and T. Era (retroviral packaging plasmids) for kindly providing experimental materials; J. Tsueda, A. Mikuniya, Y. Okamoto, M. Aoki, H. Tsuduki, M. Saito, and R. Matsumura for technical and secretarial assistance; and the other members of our laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported in part by the Basic Science and Platform Technology Program for Innovative Biological Medicine of the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (T.O., JP18am0301007), Grant-in-Aid by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (T.O., JP18H05417; T.O., JP19H01029; K.S., JP16J08600; K.S., JP19K16522; and K.S., JP21K15359), Joint Usage and Joint Research Programs by the Institute of Advanced Medical Sciences of Tokushima University, the Uehara Memorial Foundation (T.O.), and the Sasakawa Scientific Research Grant from The Japan Science Society (K.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. E.S.H. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2107141118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Chen L., Flies D. B., Molecular mechanisms of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 227–242 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okazaki T., Chikuma S., Iwai Y., Fagarasan S., Honjo T., A rheostat for immune responses: The unique properties of PD-1 and their advantages for clinical application. Nat. Immunol. 14, 1212–1218 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnell A., Bod L., Madi A., Kuchroo V. K., The yin and yang of co-inhibitory receptors: Toward anti-tumor immunity without autoimmunity. Cell Res. 30, 285–299 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharpe A. H., Pauken K. E., The diverse functions of the PD1 inhibitory pathway. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 153–167 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brahmer J. R., et al., Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: Safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 3167–3175 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ribas A., Wolchok J. D., Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science 359, 1350–1355 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michot J. M., et al., Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: A comprehensive review. Eur. J. Cancer 54, 139–148 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okazaki T., Okazaki I. M., Stimulatory and inhibitory co-signals in autoimmunity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1189, 213–232 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corse E., Gottschalk R. A., Allison J. P., Strength of TCR-peptide/MHC interactions and in vivo T cell responses. J. Immunol. 186, 5039–5045 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viganò S., et al., Functional avidity: A measure to predict the efficacy of effector T cells? Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 153863 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zehn D., Bevan M. J., T cells with low avidity for a tissue-restricted antigen routinely evade central and peripheral tolerance and cause autoimmunity. Immunity 25, 261–270 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hui E., et al., T cell costimulatory receptor CD28 is a primary target for PD-1-mediated inhibition. Science 355, 1428–1433 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okazaki T., Maeda A., Nishimura H., Kurosaki T., Honjo T., PD-1 immunoreceptor inhibits B cell receptor-mediated signaling by recruiting src homology 2-domain-containing tyrosine phosphatase 2 to phosphotyrosine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 13866–13871 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokosuka T., et al., Programmed cell death 1 forms negative costimulatory microclusters that directly inhibit T cell receptor signaling by recruiting phosphatase SHP2. J. Exp. Med. 209, 1201–1217 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimizu K., et al., PD-1 imposes qualitative control of cellular transcriptomes in response to T cell activation. Mol. Cell 77, 937–950.e6 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dash P., et al., Paired analysis of TCRα and TCRβ chains at the single-cell level in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 288–295 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fink P. J., Matis L. A., McElligott D. L., Bookman M., Hedrick S. M., Correlations between T-cell specificity and the structure of the antigen receptor. Nature 321, 219–226 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alli R., Nguyen P., Geiger T. L., Retrogenic modeling of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis associates T cell frequency but not TCR functional affinity with pathogenicity. J. Immunol. 181, 136–145 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alli R., Zhang Z. M., Nguyen P., Zheng J. J., Geiger T. L., Rational design of T cell receptors with enhanced sensitivity for antigen. PLoS One 6, e18027 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Udyavar A., Alli R., Nguyen P., Baker L., Geiger T. L., Subtle affinity-enhancing mutations in a myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-specific TCR alter specificity and generate new self-reactivity. J. Immunol. 182, 4439–4447 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikolić-Zugić J., Carbone F. R., The effect of mutations in the MHC class I peptide binding groove on the cytotoxic T lymphocyte recognition of the Kb-restricted ovalbumin determinant. Eur. J. Immunol. 20, 2431–2437 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evavold B. D., Allen P. M., Separation of IL-4 production from Th cell proliferation by an altered T cell receptor ligand. Science 252, 1308–1310 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joglekar A. V., Li G., T cell antigen discovery. Nat. Methods 10.1038/s41592-020-0867-z. (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Candia M., Kratzer B., Pickl W. F., On peptides and altered peptide ligands: From origin, mode of action and design to clinical application (immunotherapy). Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 170, 211–233 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alam S. M., et al., Qualitative and quantitative differences in T cell receptor binding of agonist and antagonist ligands. Immunity 10, 227–237 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daniels M. A., et al., Thymic selection threshold defined by compartmentalization of Ras/MAPK signalling. Nature 444, 724–729 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zehn D., Lee S. Y., Bevan M. J., Complete but curtailed T-cell response to very low-affinity antigen. Nature 458, 211–214 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashwell J. D., DeFranco A. L., Paul W. E., Schwartz R. H., Antigen presentation by resting B cells. Radiosensitivity of the antigen-presentation function and two distinct pathways of T cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 159, 881–905 (1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reay P. A., Kantor R. M., Davis M. M., Use of global amino acid replacements to define the requirements for MHC binding and T cell recognition of moth cytochrome c (93-103). J. Immunol. 152, 3946–3957 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baumgartner C. K., Ferrante A., Nagaoka M., Gorski J., Malherbe L. P., Peptide-MHC class II complex stability governs CD4 T cell clonal selection. J. Immunol. 184, 573–581 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zahm C. D., Colluru V. T., McNeel D. G., Vaccination with high-affinity epitopes impairs antitumor efficacy by increasing PD-1 expression on CD8+ T cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 5, 630–641 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carey B. S., Poulton K. V., Poles A., Factors affecting HLA expression: A review. Int. J. Immunogenet. 46, 307–320 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ting J. P., Trowsdale J., Genetic control of MHC class II expression. Cell 109 (suppl. 1), S21–S33 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou F., Molecular mechanisms of IFN-gamma to up-regulate MHC class I antigen processing and presentation. Int. Rev. Immunol. 28, 239–260 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishimura H., Nose M., Hiai H., Minato N., Honjo T., Development of lupus-like autoimmune diseases by disruption of the PD-1 gene encoding an ITIM motif-carrying immunoreceptor. Immunity 11, 141–151 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishimura H., et al., Autoimmune dilated cardiomyopathy in PD-1 receptor-deficient mice. Science 291, 319–322 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okazaki T., et al., Hydronephrosis associated with antiurothelial and antinuclear autoantibodies in BALB/c-Fcgr2b−/−Pdcd1−/− mice. J. Exp. Med. 202, 1643–1648 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J., et al., PD-1 deficiency results in the development of fatal myocarditis in MRL mice. Int. Immunol. 22, 443–452 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wucherpfennig K. W., Sethi D., T cell receptor recognition of self and foreign antigens in the induction of autoimmunity. Semin. Immunol. 23, 84–91 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aleksic M., et al., Different affinity windows for virus and cancer-specific T-cell receptors: Implications for therapeutic strategies. Eur. J. Immunol. 42, 3174–3179 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rizvi N. A., et al., Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 348, 124–128 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yadav M., et al., Predicting immunogenic tumour mutations by combining mass spectrometry and exome sequencing. Nature 515, 572–576 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yi M., et al., The role of neoantigen in immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 7, 28 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riaz N., et al., Tumor and microenvironment evolution during immunotherapy with nivolumab. Cell 171, 934–949.e16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maeda N., et al., Glucocorticoids potentiate the inhibitory capacity of programmed cell death 1 by up-regulating its expression on T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 19896–19906 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mizuno R., et al., PD-1 efficiently inhibits T cell activation even in the presence of co-stimulation through CD27 and GITR. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 511, 491–497 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mizuno R., et al., PD-1 primarily targets TCR signal in the inhibition of functional T cell activation. Front. Immunol. 10, 630 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okazaki T., et al., PD-1 and LAG-3 inhibitory co-receptors act synergistically to prevent autoimmunity in mice. J. Exp. Med. 208, 395–407 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wei F., et al., Strength of PD-1 signaling differentially affects T-cell effector functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E2480–E2489 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sugiura D., et al., Restriction of PD-1 function by cis-PD-L1/CD80 interactions is required for optimal T cell responses. Science 364, 558–566 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martínez-Usatorre A., Donda A., Zehn D., Romero P., PD-1 blockade unleashes effector potential of both high- and low-affinity tumor-infiltrating T cells. J. Immunol. 201, 792–803 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dougan S. K., et al., Transnuclear TRP1-specific CD8 T cells with high or low affinity TCRs show equivalent antitumor activity. Cancer Immunol. Res. 1, 99–111 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Billeskov R., et al., Low antigen dose in adjuvant-based vaccination selectively induces CD4 T cells with enhanced functional avidity and protective efficacy. J. Immunol. 198, 3494–3506 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hashimoto M., Takemoto T., Electroporation enables the efficient mRNA delivery into the mouse zygotes and facilitates CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing. Sci. Rep. 5, 11315 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maruhashi T., et al., LAG-3 inhibits the activation of CD4+ T cells that recognize stable pMHCII through its conformation-dependent recognition of pMHCII. Nat. Immunol. 19, 1415–1426 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maeda T. K., Sugiura D., Okazaki I. M., Maruhashi T., Okazaki T., Atypical motifs in the cytoplasmic region of the inhibitory immune co-receptor LAG-3 inhibit T cell activation. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 6017–6026 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanaka Y., Era T., Nishikawa S., Kawamata S., Forced expression of Nanog in hematopoietic stem cells results in a gammadeltaT-cell disorder. Blood 110, 107–115 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ishida M., et al., Differential expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2, ligands for an inhibitory receptor PD-1, in the cells of lymphohematopoietic tissues. Immunol. Lett. 84, 57–62 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elzhov T. V., Mullen K. M., Spiess A.-N., Bolker B., Title R Interface to the Levenberg-Marquardt Nonlinear Least-Squares Algorithm Found in MINPACK, Plus Support for Bounds, Version 1.2.1. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/minpack.lm/minpack.lm.pdf. Accessed 2 July 2021.

- 60.Nakajima A., et al., Antitumor effect of CD40 ligand: Elicitation of local and systemic antitumor responses by IL-12 and B7. J. Immunol. 161, 1901–1907 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.