Abstract

Transcriptional activation by nuclear hormone receptors is mediated by the 160-kDa family of nuclear receptor coactivators. These coactivators associate with DNA-bound nuclear receptors and transmit activating signals to the transcription machinery through two activation domains. In screening for mammalian proteins that bind the C-terminal activation domain of the nuclear receptor coactivator GRIP1, we identified a new variant of mouse Zac1 which we call mZac1b. Zac1 was previously discovered as a putative transcriptional activator involved in regulation of apoptosis and the cell cycle. In yeast two-hybrid assays and in vitro, mZac1b bound to GRIP1, to CREB-binding protein (CBP) and p300 (which are coactivators for nuclear receptors and other transcriptional activators), and to nuclear receptors themselves in a hormone-independent manner. In transient-transfection assays mZac1b exhibited a transcriptional activation activity when fused with the Gal4 DNA binding domain, and it enhanced transcriptional activation by the Gal4 DNA binding domain fused to GRIP1 or CBP fragments. More importantly, mZac1b was a powerful coactivator for the hormone-dependent activity of nuclear receptors, including androgen, estrogen, glucocorticoid, and thyroid hormone receptors. However, with some reporter genes and in some cell lines mZac1b acted as a repressor rather than a coactivator of nuclear receptor activity. Thus, mZac1b can interact with nuclear receptors and their coactivators and play both positive and negative roles in regulating nuclear receptor function.

The nuclear receptors (NRs) are a large family of structurally and functionally related transcriptional regulators; members include the receptors for steroid, thyroid, retinoid, and vitamin D hormones, which activate transcription in response to their ligands by binding to enhancer elements in the promoters of target genes (4, 15, 42, 57). Flanking the centrally located DNA binding domains (DBD) of these receptors are two transcriptional activation domains (10, 13, 23, 37). Activation function 2 (AF-2), which is highly conserved among all NRs that function as transcriptional activators, is an integral part of the C-terminal hormone binding domain (HBD), and its activity is hormone dependent. AF-1, located in the N-terminal region, has no apparent sequence homology among different NRs. AF-1 regions can function in a hormone-independent manner if separated from the HBD, but in the context of the full-length receptor their activity is controlled by the hormonal status of the HBD and AF-1 and AF-2 act synergistically. Direct physical interactions between AF-1 and AF-2 have been implicated as the mechanism of this synergy for some steroid receptors, including androgen receptor (AR) (12, 29, 36) and estrogen receptor α (ERα) (35, 43).

The mechanism of transcriptional activation by the DNA-bound NRs and their activation functions appears to involve their ability to recruit a variety of coactivator proteins, which modify local chromatin structure by catalyzing covalent histone modifications and direct assembly and/or stabilization of the transcription preinitiation complex (9, 27, 55, 63). A growing list of putative coactivators have been identified by their abilities to bind and/or enhance the activity of NRs (18, 27, 63). Among these, a group of three protein families may function in a coactivator complex associated with the DNA-bound NR: the p160 coactivators (63), CREB-binding protein (CBP) and p300 (31, 63, 65), and p/CAF (5, 9, 34, 63). The p160 coactivators include SRC-1 (48), GRIP1 (25, 26) (also called TIF2 [60, 61]), and p/CIP (56) (also called ACTR [9], RAC3 [38], AIB1 [3], and TRAM1 [54]). They bind directly to the conserved AF-2 functions of NRs and enhance AF-2 activity. The same coactivators bind the AF-1 regions of some (progesterone receptor, ER, and AR) but not other (thyroid hormone receptor [TR]) NRs and thereby enhance AF-1 function (41, 47, 62). The two other classes of coactivators have been shown to bind directly both to the NR and to the p160 coactivators (5, 9, 31, 34, 56, 60, 65). These coactivators, CBP, p300, and p/CAF, can acetylate histones, some transcriptional activators, and some components of the transcription preinitiation complex (21, 30, 34, 46, 64). Histone acetylation causes changes in nucleosome structure and internucleosomal interactions that are associated with active gene transcription (39, 40, 52). CBP and p300 can also bind TATA-binding protein and TFIIB, components of the transcription preinitiation complex (53). The ability of these two proteins to bind to many different transcriptional activators, signal transduction pathway components, and even basal transcription factors has led to the proposal that CBP and p300 serve as platforms to integrate the effects of multiple signaling pathways on many different transcriptional activator proteins (55).

In this study we searched for additional components of the p160 coactivator complex. The p160 coactivators have two activation domains, AD1 and AD2, which transmit the activating signal from the NR to the chromatin and/or transcription machinery (9, 41, 60). The function of AD1, located near amino acid 1000 of these ∼1,400-amino-acid proteins, is due to its ability to bind CBP or p300. AD2, located near the C terminus, functions by an unknown mechanism that is independent of CBP and p300. To study the role of AD2 and its associated proteins, we screened a mouse cDNA library to identify proteins that bind to the C-terminal region of GRIP1. Here we report the identification of a new GRIP1-binding protein which is a variant of a previously identified zinc finger transcription factor, Zac1 (zinc finger protein which regulates apoptosis and cell cycle arrest) (51, 59), which binds the C-terminal region of p160 coactivators. We named the new isoform mZac1b and we refer to the original isoform as mZac1a. We found that mZac1b can be a potent coactivator or a repressor of NR activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of mZac1b cDNA clones.

Partial mZac1b cDNA clones were isolated by using the yeast two-hybrid system as described previously (8) to screen a mouse 17-day embryo cDNA library for clones encoding proteins that bind to the C-terminal region (amino acids 1121 to 1462) of GRIP1. Together three distinct but overlapping partial cDNA clones had a complete 3′ coding sequence identical to that of mZac1a (51, 59), except that the mZac1b sequence had a 33-bp insert (see Results) and lacked a complete 5′ coding region. The full-length coding region of mZac1b was synthesized by PCR, using the same mouse embryo library as a template, a 5′ sense primer (5′-TTGAATTCATGGCTCCATTCCGCTGTC-3′ [underlined translation start codon]) representing the 5′ end of the mZac1a-coding sequence (GenBank accession numbers X95503 and X95504), and a 3′ antisense primer (5′-TTCTCGAGTTATCTAAATGCGTGATGG-3′ [underlined translation stop codon]) representing the 3′ end of the coding region from the partial mZac1b clones isolated from our two-hybrid screen. All cDNA clones were sequenced by using the dideoxy chain termination method with a Sequenase, version 2.0, DNA sequencing kit (United States Biochemicals) or by an ABI automatic sequencer in the University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center Microchemical Core Facility.

Plasmids.

The complete mZac1b-coding region (codons 1 to 704) was cloned into the EcoRI and XhoI sites of vector pSG5.HA (8), which has promoters for expression in vitro and in mammalian cells and provides an N-terminal hemagglutinin tag for the expressed protein. The pSG5.HA vector, coding for full-length GRIP1, was described previously (8). Other DNA fragments cloned into pSG5.HA include a XhoI-BglII fragment encoding human AR542–919 (DBD plus HBD) and an EcoRI-XhoI fragment encoding human AR1–671 (AF-1 plus DBD). Vectors encoding the Gal4 DBD fused to various fragments of mZac1b were constructed by inserting EcoRI-XhoI fragments of the appropriate PCR-amplified mZac1b cDNA into the EcoRI and SalI sites of the pM vector (Clontech). A Gal4 DBD-GRIP1 (full length) expression vector was constructed by inserting an EcoRI-SalI fragment encoding GRIP15–1462 into pM. Reporter genes MMTV-LUC, MMTV(ERE)-LUC, MMTV(TRE)-LUC, EREII-LUC(GL45), and GK1 were described previously (49, 58). HSVtk-LUC with no enhancer element was constructed by deleting a HindIII fragment containing the estrogen-responsive element (ERE) from EREII-LUC(GL45). For expression of NRs in mammalian cells and/or in vitro, vectors pSVAR0 (6) and pCMV.AR0 (7) for human AR, pHE0 (20) for human ERα, pKSX (44) for mouse glucocorticoid receptor (GR), and pCMX.hTRβ1 (16) for human TRβ1 were described previously, as were pM-ARAF1 and pM-ARAF2 (41), coding for the Gal4 DBD fused to the N-terminal AF-1 activation domain or the C-terminal HBD, respectively, of human AR. pOS7/MRΔN encoding rat mineralocorticoid (MR) DBD-HBD (amino acid 596 to the C terminus) was kindly provided by David Pearce (University of California, San Francisco). The expression vector for the Gal4 DBD fused to CBP2041–2240 was described previously (53).

Bacterial expression vectors for glutathione S-transferase (GST) fused to GRIP1 and CBP fragments were constructed by inserting the appropriate PCR fragments into pGEX-4T1 (Pharmacia) as follows: GRIP15–479 into the EcoRI-BamHI sites; GRIP15–765, CBP2041–2240, and CBP1594–2441 into the EcoRI-XhoI sites; and GRIP11305–1462 into the SmaI-SalI sites. A vector encoding GST fused with full-length mZac1b was constructed by inserting an mZac1b-encoding PCR fragment into the BamHI and XhoI sites of pGEX-2TK. Other vectors encoding GST-GRIP1 (26, 41) and GST-p3001571–2414 (33) fusion proteins were described previously.

Cell culture, transient-transfection assays, and immunoblotting.

For functional assays HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium–F-12 supplemented with 10% charcoal-dextran-treated fetal bovine serum. CV-1 cells (19) and 1471.1 cells (17) were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with the same serum. Transient transfections and luciferase assays were performed as described previously (41) in six-well (3.3-cm-diameter wells) culture dishes. Total DNA was adjusted to 2 μg by adding the necessary amount of vector pSG5.HA. Luciferase activity of the transfected cell extracts is presented as relative light units, and values are the means and standard deviations for three transfected cultures. Since the expression of many control vectors that are used to monitor transfection efficiency is influenced by coactivators, internal controls were not used. Instead, reproducibility of observed effects was determined in multiple independent transfection experiments. Immunoblotting of transiently transfected COS7 cells (19) was performed as previously described (41), using 10% of the extract from a well of a six-well culture dish and monoclonal antibodies 3F10 (Roche) against the hemagglutinin epitope and RK5C1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) against the Gal4 DBD.

Protein-protein interaction assays.

Radioactively labeled proteins were translated in vitro, incubated with immobilized GST fusion proteins, eluted, and analyzed by gel electrophoresis as previously described (41). Radioactive proteins in gels were detected in a PhosphorImager 445SI and quantified by ImageQuaNT software (Molecular Dynamics). Quantitative yeast two-hybrid assays were performed as described previously (11).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence for mZac1b has been deposited in GenBank under accession number AF147785.

RESULTS

Isolation of a new mZac1 variant.

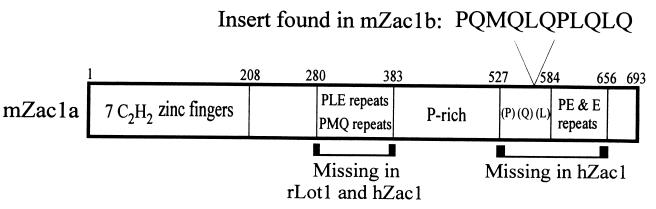

The C-terminal region of GRIP1 (amino acids 1121 to 1462), containing AD2 (9, 41, 60), was used as bait to screen a mouse 17-day embryo cDNA library by the yeast two-hybrid method. Three nonidentical positive clones with partially overlapping sequences, representing a total of 1,612 unique nucleotides, were found to be identical to the sequence reported in GenBank under accession numbers X95503 and X95504, coding for mZac1 (51), with two exceptions. Our sequence extended the 3′ untranslated region of the previously reported sequence by 50 nucleotides and also contained a 33-nucleotide insert, coding for the amino acids PQMQLQPLQLQ, located after codon 567 of the previously reported mZac1 sequences. The insert was found in all three of the nonidentical, overlapping clones that we isolated. Since the combined 1,612-nucleotide sequence of our three clones lacked a complete 5′ coding region, we employed PCR to isolate the missing coding sequences from the same mouse 17-day embryo cDNA library; the upstream primer was designed from the 5′ end of the previously reported mZac1-coding region (51), and the downstream primer represented the 3′ end of the coding region of our newly isolated clones. The PCR product contained a 704-codon open reading frame which was identical to that of the previously reported mZac1 sequence, except for the 11-codon insertion in our clone (Fig. 1). We named this new mZac1 variant mZac1b, and we refer to the original isoform (51, 59) as mZac1a. Note that the coding region of the originally isolated mZac1a cDNA (51) was subsequently reinterpreted as a 693-codon open reading frame (59). An additional PCR product representing the 5′ untranslated and 5′ coding region of mZac1b was generated from the same mouse embryo library by using an upstream primer representing the mZac1a sequence beginning at nucleotide −248 (relative to the translation start codon) and a downstream primer beginning at nucleotide +300 of mZac1b. The sequence of the proximal 248 bp of the 5′ untranslated region of mZac1b was identical to that of mZac1a, suggesting that the two transcripts come from the same promoter.

FIG. 1.

Domains of mouse Zac1. Sequence motifs in mouse Zac1 are indicated. The 11 amino acids at the top are found in mZac1b but not mZac1a. The brackets at the bottom indicate regions missing in the homologous human and rat proteins hZac1 and rLot1. Numbers are amino acid numbers of mZac1a (51, 59).

Binding of mZac1b to NRs and their coactivators in vitro.

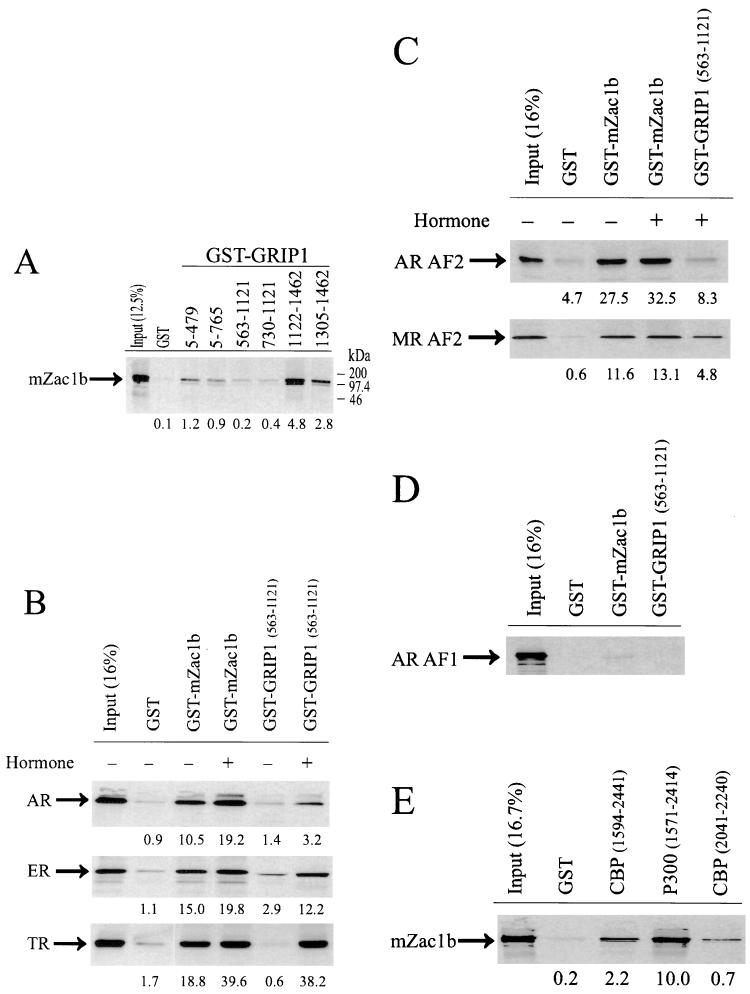

mZac1b, synthesized in vitro, bound to the C-terminal region of GRIP1 (amino acids 1122 to 1462) fused to GST and immobilized on agarose beads (Fig. 2A), confirming the results from the two-hybrid screen. mZac1b also bound somewhat more weakly to an N-terminal fragment of GRIP1 containing the basic helix-loop-helix and PAS (Per/Arnt/Sim) sequences (GRIP15–479) but failed to bind to GST fusion proteins representing central regions of the GRIP1 polypeptide (GRIP1563–1121) which contain the CBP and p300 binding site and the NR boxes that efficiently bind NR HBDs (Fig. 2B) (24). Similar results were obtained in quantitative yeast two-hybrid assays (data not shown). Note that the migration of mZac1b in sodium dodecyl sulfate gels was equivalent to that of a protein of about 100 kDa (Fig. 2A), although its sequence indicates an open reading frame of only 704 amino acids. This slower-than-expected migration may be due to the unusual repeats of glutamic acid (Fig. 1), since a C-terminal mZac1b fragment containing the glutamic acid repeats also migrated more slowly than the length of its coding region would suggest (Fig. 3, compare the predicted length and actual migration of Gal4-mZac1b fusion protein 9 with those of proteins 4 and 8). Similar anomalous slow migration of mZac1a was also evident in previous studies (51, 59).

FIG. 2.

Binding of mZac1b to NRs and NR coactivators. The proteins indicated at the left of each panel were translated in vitro and incubated with bead-bound GST fusion proteins (indicated at the top of each panel along with amino acid numbers for protein fragments fused to GST); bound proteins were eluted, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and visualized by autoradiography. The percentage of labeled protein bound, as determined by phosphorimager analysis, is shown below each lane. For comparison, the leftmost lane of each panel shows the indicated percentage of input protein used in the binding reaction. In panels B and C, the following hormones were included where indicated: for AR, 1 μM DHT; for ER, 1 μM estradiol; for TR, 1 μM T3; and for MR, 1 μM corticosterone.

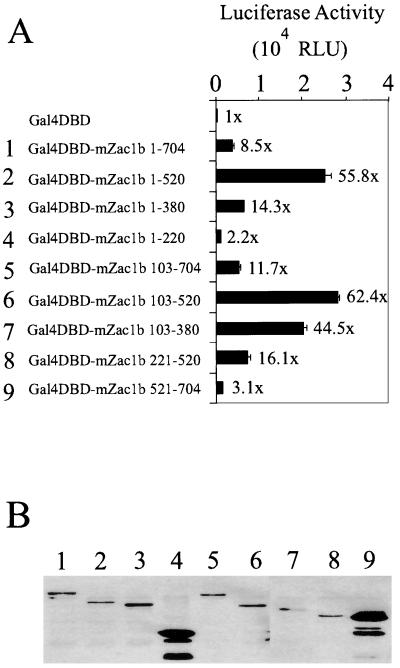

FIG. 3.

Transcriptional activation domain of Zac1. (A) Expression vectors (1 μg) for the indicated fragments of mZac1b fused to the Gal4 DBD were transiently transfected into HeLa cells along with the GK1 reporter gene (1 μg), which encodes luciferase and is controlled by Gal4 response elements. Luciferase activities of the transfected cell extracts were determined. Numbers beside the bars indicate fold activation compared with that of the Gal4 DBD alone. RLU, relative light units. (B) The vectors encoding the Gal4 DBD-Zac1 fusion proteins (2 μg) listed in panel A were transiently transfected into COS7 cells and the cell extracts were subjected to immunoblot analysis using antibodies against the Gal4 DBD. Lane numbers correspond to the line numbers in panel A.

A GST-mZac1b fusion protein also bound strongly in vitro to full-length AR, ERα, and TRβ1 (Fig. 2B). The binding was largely hormone independent but was reproducibly enhanced by hormone. In contrast, binding of the same NRs to a GST-GRIP1 protein containing the NR HBD (AF-2) binding domain was highly hormone dependent, as found previously (11, 24). GST-mZac1b also bound to the HBDs of AR and MR in a hormone-independent manner (Fig. 2C), but it bound very weakly or not at all to the AR AF-1 region (Fig. 2D). Similarly, mZac1b bound the HBD of ERα in a hormone-independent manner but bound weakly or not at all to the ERα AF-1 region (data not shown).

mZac1b also bound in vitro to GST fusions with C-terminal fragments of CBP and p300 (Fig. 2E), two related coactivators that also help to mediate transcriptional activation by NRs as well as many other transcriptional activator proteins (9, 31, 34, 65). Binding of mZac1b to a C-terminal p300 fragment was also observed in yeast two-hybrid assays (data not shown). Thus, mZac1b bound to NRs and two different classes of NR coactivators.

Activation domain of mZac1b.

Since mZac1b can bind NRs and their coactivators, we tested whether mZac1b had another property expected of a coactivator, i.e., a putative activation domain. Fragments of mZac1b were fused to the Gal4 DBD and tested for their ability to activate a Gal4-responsive reporter gene in transiently transfected HeLa cells. The maximum activity was observed with mZac1b103–520, and a slightly lower level of activity was observed with a subfragment, amino acids 103 to 380 (Fig. 3A). The N-terminal (amino acids 1 to 102) and C-terminal (amino acids 521 to 704) regions of mZac1b had a negative effect on this activity, since their presence, even in full-length mZac1b, reduced the activity (e.g., compare fragments 1 and 2 and compare fragments 3 and 7). This suggests a possible regulatory role for the N-terminal and C-terminal domains that could be modulated by interaction of mZac1b with other proteins. Lack of activity in some fragments was not due to lack of expression, since most of the Gal4 fusion proteins were expressed at similar levels, according to immunoblot analyses conducted on extracts from transiently transfected COS7 cells (Fig. 3B). Fusion proteins 4 and 9 were expressed at elevated levels compared with the others. Thus, mZac1b has an activation domain in the central region of its polypeptide chain, which partially overlaps with the N-terminal zinc finger domain (compare Fig. 1 and 3).

Enhancement of AR function by mZac1b.

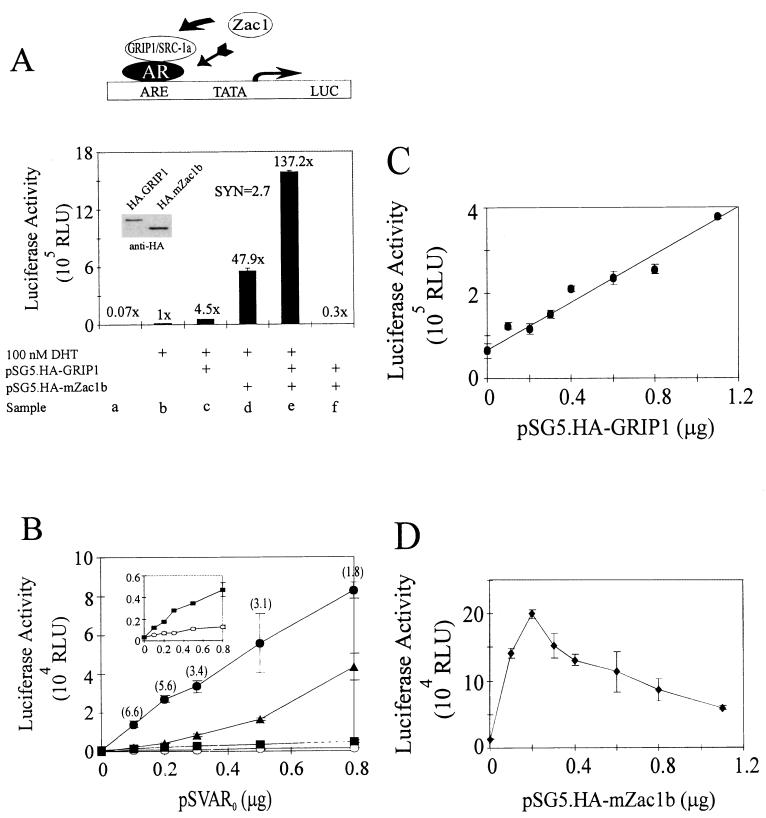

The findings that mZac1b bound NRs and their coactivators and contains a putative activation domain suggested that mZac1b might act as a coactivator for NRs. Transient transfections in HeLa cells were used to test the ability of mZac1b and GRIP1 to act separately and together as coactivators for AR with a reporter gene controlled by a mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter. GRIP1 enhanced hormone-activated AR function 4.5-fold (Fig. 4A, sample c), while mZac1b caused a 48-fold enhancement (sample d). Together GRIP1 and mZac1b caused a 137-fold enhancement (sample e), and this activity was completely hormone dependent (sample f). Thus, GRIP1 and mZac1b activated the reporter gene only in the presence of hormone-activated AR, consistent with the role of a coactivator. GRIP1 and mZac1b acted synergistically; the effect of the two together was 2.7-fold greater than the sum of their individual effects. This synergy ratio was calculated by dividing the extra activity observed when GRIP1 and mZac1b were added together (e − b in Fig. 4A) by the sum of the extra activity due to GRIP1 alone plus the extra activity due to mZac1b alone (c + d − 2b in Fig. 4A). Synergy was also observed when mZac1b was tested with SRC-1a, another member of the p160 coactivator family (data not shown). By immunoblot analysis, mZac1b and GRIP1 were expressed at similar levels when their expression plasmids were transfected into COS7 cells (Fig. 4A, inset), indicating that the stronger coactivator effect of mZac1b was not due to a higher level of expression. The higher relative coactivator effect of mZac1b than GRIP1 was maintained when the amount of AR expression vector was varied over an eightfold range, as was the synergistic effect of the two coactivators (Fig. 4B). However, the synergy (Fig. 4B) was more pronounced at lower AR levels; the activity was approximately sevenfold more than additive at 0.1 μg of AR vector and twofold more than additive at 0.8 μg of AR vector. The enhanced reporter gene activity observed with mZac1b and/or GRIP1 was completely dependent on the presence of AR. In the presence of mZac1b, the reporter gene activity was directly proportional to the amount of GRIP1 vector over a 10-fold range of GRIP1 vector amounts (Fig. 4C), indicating that the amount of GRIP1 vector used in the synergy studies (0.4 to 0.5 μg [Fig. 4A and B]) was nonsaturating. However, in the presence of GRIP1, 0.2 μg of mZac1b vector produced an optimum response, and increasing the amount of mZac1b vector above this level reduced but did not eliminate the positive coactivator effect due to mZac1b (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

Synergistic enhancement of AR function by mZac1b and GRIP1. (A) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with MMTV-LUC reporter gene (0.5 μg), pSVAR0 (0.5 μg) encoding AR, and either 0.5 μg of pSG5.HA-GRIP1, 0.5 μg of pSG5.HA-mZac1b, or both. Where indicated, transfected cultures were grown in 100 nM DHT. Luciferase activities of the transfected cell extracts were determined. Numbers above the bars indicate activity relative to that of hormone-activated AR with no added coactivators. A synergy ratio (SYN) was calculated as described in the text. The diagram at the top indicates the proposed mechanism of reporter gene activation: recruitment of mZac1b to the transcription complex could occur by mZac1b binding either to AR or to GRIP1. ARE, androgen-responsive elements in the MMTV promoter; TATA, TATA box of the MMTV promoter; LUC, luciferase-coding region; HA, hemagglutinin; rightward-pointing arrow, transcription start site. (B) HeLa cells were transfected as described above with the indicated amounts of pSVAR0 and 0.4 μg of the MMTV-LUC reporter gene. Four micrograms of pSG5.HA-mZac1b and/or 0.4 μg of pSG5.HA-GRIP1 was included or not as follows: open circles, no GRIP1 or mZac1b; closed squares, GRIP1; closed triangles, mZac1b; closed circles, GRIP1 and mZac1b. Transfected cells were grown with 100 nM DHT. The inset shows the lower two curves on an expanded scale. Synergy ratios calculated as for panel A are shown in parentheses. (C) HeLa cell transfections were performed with the indicated amounts of pSG5.HA-GRIP1 and 0.3 μg each of MMTV-LUC, pSVAR0, and pSG5.HA-mZac1b; transfected cells were grown with 100 nM DHT. (D) HeLa cell transfections were performed with the indicated amounts of pSG5.HA-mZac1b and 0.3 μg each of MMTV-LUC, pSVAR0, and pSG5.HA-GRIP1; transfected cells were grown with DHT. RLU, relative light units.

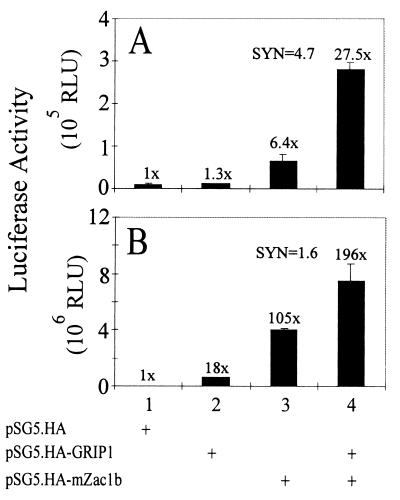

To determine which AR activation function was stimulated by mZac1b, the N-terminal domain of AR, containing AF-1, and the C-terminal AR HBD, containing AF-2, were each fused to the Gal4 DBD and expressed in HeLa cells with mZac1b and/or GRIP1. mZac1b enhanced AF-1 activity 6-fold (Fig. 5A) and AF-2 activity more than 100-fold (Fig. 5B). GRIP1 had little if any effect on AF-1 activity but enhanced AF-2 activity 18-fold. The two coactivators had synergistic effects on AF-1 and AF-2, but the synergy was more pronounced with AF-1 (synergy ratio = 4.7) than AF-2 (synergy ratio = 1.6). Neither GRIP1 nor mZac1b had any effect on reporter gene activity in the absence of the AR-Gal4 DBD fusion proteins (data not shown). Thus, although mZac1b bound AR AF-2 but not AR AF-1 (Fig. 2C and D), it enhanced the function of both activation domains.

FIG. 5.

Synergistic enhancement of AR AF-1 and AF-2 function by mZac1b and GRIP1. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with 0.5 μg of pM-ARAF1 (A) or pM-ARAF2 (B) and 0.5 μg of the GK1 reporter gene. Where indicated, 0.5 μg of pSG5.HA-mZac1b and/or 0.5 μg of pSG5.HA-GRIP1 was also included, and cells transfected with pM-ARAF2 were grown with 100 nM DHT. SYN, synergy ratio calculated as for Fig. 4A. Numbers above the bars indicate activity relative to that of AR AF-1 or AR AF-2 in the absence of added coactivators. RLU, relative light units.

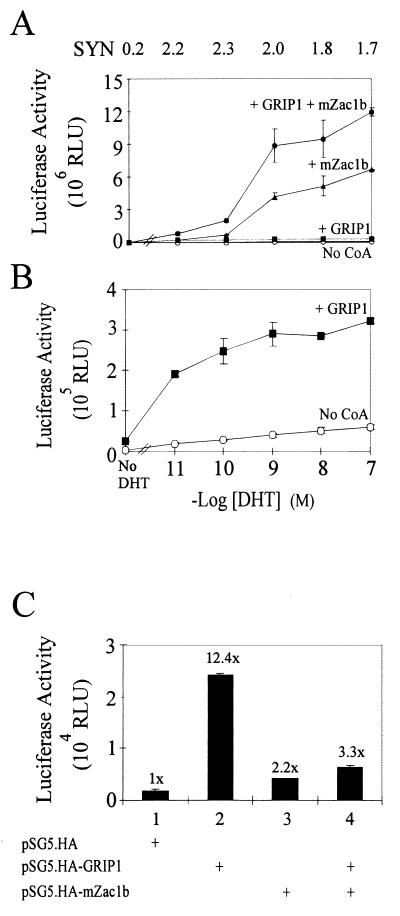

To examine whether mZac1b and GRIP1 had effects on hormone potency, various concentrations of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) were tested with full-length AR in the transient-transfection assays. The synergistic effects of GRIP1 and mZac1b were observed at subsaturating as well as saturating concentrations of DHT (Fig. 6A). However, the concentration of DHT required to elicit half-maximal activity (EC50) was affected by the coactivators. In the presence of GRIP1, the EC50 was 4 to 10 times lower than in the presence of mZac1b alone or mZac1b plus GRIP1 (Fig. 6A and B). GRIP1 and mZac1b also had different effects on the hormone-independent activity of AR. GRIP1 enhanced AR function even in the absence of hormone, whereas mZac1b had little if any effect by itself and even suppressed the hormone-independent activity caused by GRIP1 (Fig. 6C). In the absence of AR, neither GRIP1 nor mZac1b had any effect on the expression of the reporter gene (data not shown). Thus, in the presence of GRIP1, mZac1b altered the effects of DHT in two ways: mZac1b suppressed the hormone-independent activity of AR caused by GRIP1, and it increased the EC50 for DHT and thus had a more dramatic coactivator effect at higher DHT concentrations than at lower DHT concentrations. For example, when the activity of GRIP1 was compared with the activity of GRIP1 plus mZac1b, mZac1b was found to have caused a 4-fold enhancement at 10−11 M DHT, an 8-fold enhancement at 10−10 M DHT, and a 30-fold enhancement at 10−9 M and higher concentrations of DHT (calculated from Fig. 6A and B). These effects on EC50 and on the hormone-independent activity were observed in two independent experiments.

FIG. 6.

Relationship of AR activity to DHT concentration in the presence of mZac1b and/or GRIP1. (A) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with 0.5 μg of the MMTV-LUC reporter gene, 0.5 μg of pSVAR0, and, where indicated, 0.5 μg of pSG5.HA-mZac1b and/or 0.5 μg of pSG5.HA-GRIP1. Transfected cells were grown with the indicated concentrations of DHT. Synergy ratios (SYN), calculated as for Fig. 4A, are shown at the top. CoA, coactivator. (B) The two lower curves from panel A are shown on an expanded scale. (C) The activity from panel A in the absence of DHT is shown. Numbers above the bars indicate activity relative to that observed in the absence of mZac1b and GRIP1. RLU, relative light units.

Promoter-selective coactivator or repressor effects of mZac1b for ER.

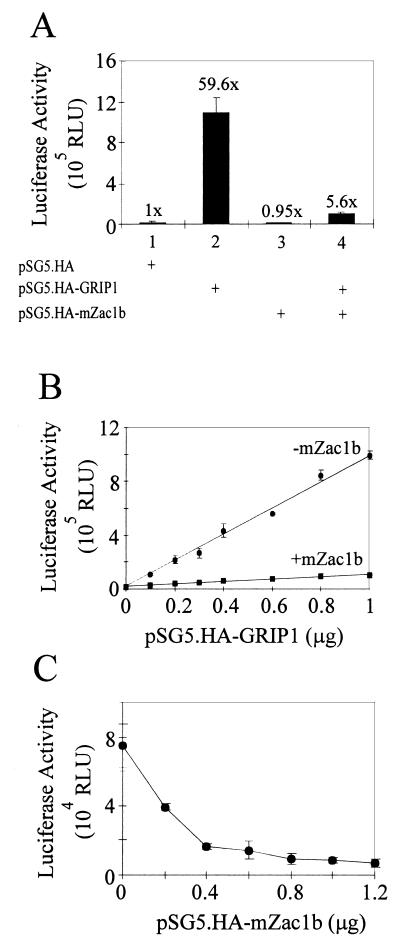

mZac1b also acted as a coactivator in HeLa cells for GR acting on the MMTV promoter and for TRβ1 acting on a modified MMTV promoter having the endogenous glucocorticoid-responsive elements (GREs) replaced by a single palindromic thyroid hormone-responsive element (data not shown). The enhancement of GR and TR function by mZac1b (5- to 12-fold) was less dramatic than the enhancement of AR function (up to 50-fold). In contrast, when estradiol-activated ERα was tested with a similarly modified MMTV promoter having the endogenous glucocorticoid-responsive elements replaced by a single ERE, mZac1b had little or no coactivator effect by itself (Fig. 7A). GRIP1 alone enhanced ER function as much as 60-fold (Fig. 7A and B), but mZac1b repressed the GRIP1-enhanced ER activity up to 10-fold (Fig. 7). The repression occurred at all amounts of GRIP1 and mZac1b expression vectors tested (Fig. 7B and C). The amounts of ER expression vector (0.04 to 0.1 μg) used in these experiments were just saturating or below saturating, because 0.1 to 0.2 μg of plasmid was determined to be just saturating in the presence of GRIP1 (data not shown). In the absence of ER, mZac1b had no effect on the expression of the reporter gene (data not shown). GRIP1 and mZac1b had similar patterns of effects on tamoxifen-bound ERα, although the reporter gene activity with tamoxifen was less than 5% that observed with estradiol (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Repression by mZac1b of ER function with the MMTV(ERE) promoter. (A) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with 0.5 μg of MMTV(ERE)-LUC reporter plasmid, 0.04 μg of pHE0 (encoding hERα), and, where indicated, 0.5 μg of pSG5.HA-mZac1b and/or 0.5 μg of pSG5.HA-GRIP1. Transfected cells were grown with 100 nM estradiol, and luciferase activities of the transfected cell extracts were determined. Numbers above the bars indicate activity relative to that of ER in the absence of GRIP1 and mZac1b vectors. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with 0.4 μg of MMTV(ERE)-LUC, 0.04 μg of pHE0, the indicated amounts of pSG5.HA-GRIP1, and, where indicated, 0.4 μg of pSG5.HA-mZac1b. Cells were grown with 100 nM estradiol. (C) HeLa cells were transfected with 0.4 μg of MMTV(ERE)-LUC, 0.1 μg of pHE0, 0.4 μg of pSG5.HA-GRIP1, and the indicated amounts of pSG5.HA-mZac1b. Transfected cells were grown with 100 nM estradiol. RLU, relative light units.

When a different reporter gene [EREII-LUC(GL45)] with a different promoter (herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase promoter) and two EREs was tested with ER in the same cells, mZac1b enhanced the activity about 26-fold (Fig. 8A). GRIP1 also enhanced activity 10-fold, and the enhancement caused by mZac1b and GRIP1 together was synergistic. In the absence of ER, GRIP1 and mZac1b each caused less than 3-fold enhancement of the low basal activity of this reporter gene (Fig. 8B). When similar reporter genes with the same thymidine kinase promoter and either one or two copies of an ERE from the Xenopus vitellogenin gene were tested with ER, mZac1b caused a similar enhancement of activity. mZac1b and GRIP1 together had additive or less than additive enhancing effects; i.e., no synergy was observed (data not shown). Thus, in the same cell line mZac1b acted as a coactivator for ER with some reporter genes and a repressor of ER function with other reporter genes. The nature of the basal promoter, but not the number of EREs, appeared to dictate whether mZac1b acted positively or negatively. The repressor function seen with the MMTV promoter was observed only when GRIP1 was coexpressed; in the absence of coexpressed GRIP1, mZac1b had no effect on this promoter.

FIG. 8.

Coactivator effect of mZac1b on ER function with the thymidine kinase promoter. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with 0.5 μg of the EREII-LUC(GL45) reporter gene in the presence (A) or absence (B) of 0.04 μg of pHE0; where indicated, 0.5 μg of pSG5.HA-mZac1b and/or 0.5 μg of pSG5.HA-GRIP1 was included. Transfected cells were grown with 100 nM estradiol. The number above each bar indicates activity relative to that in the absence of coactivators. RLU, relative light units.

The observation that mZac1b failed to enhance reporter gene expression unless both NR and the appropriate hormone were present (Fig. 4 and 8) indicates that mZac1b was acting as a coactivator of NR function and was not simply acting as a general activator of reporter gene expression or as an enhancer of transfection efficiency. However, the effects of mZac1b were not restricted solely to NRs. For example, the activity of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter in HeLa cells was also enhanced six- to eightfold by mZac1b (Table 1). In contrast, GRIP1 had little if any effect on the CMV promoter. The effect of mZac1b on the CMV promoter was independent of its effect on NR function (Table 1). This is illustrated by the fact that mZac1b enhanced AR activation of the MMTV-LUC reporter gene 77-fold, enhanced ER activation of the EREII(GL45)-LUC reporter gene 26-fold, but repressed ER and ER/GRIP1 activation of the MMTV(ERE)-LUC reporter gene; expression of CMV.β-gal, used as an internal control in all of these transfections, was enhanced 6- to 8-fold in each of these cases. The fact that mZac1b can, in the same cell line and even in the same assay, act as either a coactivator or repressor of reporter gene activity, depending on the reporter gene and transcriptional activators employed, indicates again that the effects of mZac1b are not simply due to general effects on reporter gene expression or transfection efficiency. Furthermore, mZac1b may act through multiple pathways to achieve these diverse effects.

TABLE 1.

The effects of mZac1b on the CMV promoter and on NR function are independenta

| Protein(s) | Fold activation

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR + MMTV- LUC

|

ER + MMTV (ERE)-LUC

|

ER + EREII (GL45)-LUC

|

||||

| LUC | β-Gal | LUC | β-Gal | LUC | β-Gal | |

| NR | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| NR + GRIP1 | 4 | 1.4 | 24.1 | 2.0 | 10 | 1.8 |

| NR + mZac1b | 77 | 8.4 | 0.5 | 6.6 | 25.6 | 8.0 |

| NR + GRIP1 + mZac1b | 116 | 6.6 | 1.4 | 6.6 | 66.2 | 9.6 |

HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids encoding NR (0.5 μg of AR or 0.04 μg of ER), GRIP1 (0.5 μg), or mZac1b (0.5 μg) or containing the luciferase reporter gene (0.5 μg) as indicated. pCMV.β-gal (0.1 μg) was also included in each transfection. Transfected cultures were grown with the appropriate hormone. Luciferase (LUC) and β-galactosidase (β-Gal) activities are expressed relative to those of samples containing NR but no GRIP1 or mZac1b.

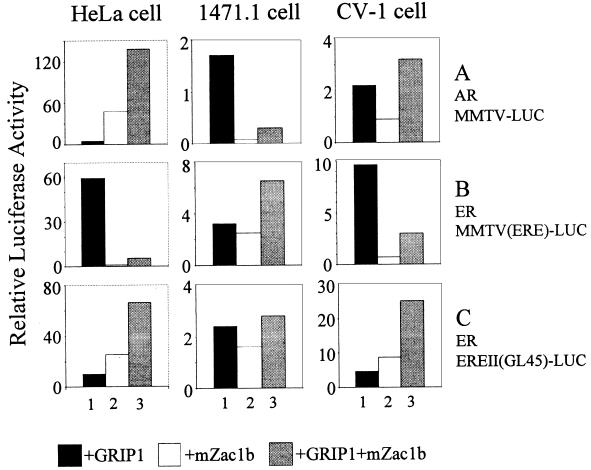

The positive or negative effect of mZac1b also depends on cell type.

To test whether cellular context can influence the ability of mZac1b to serve as a coactivator or repressor, two additional cell lines were transiently transfected with the AR expression vector, the MMTV-luciferase reporter gene, and expression vectors for GRIP1, mZac1b, or both. As shown previously (Fig. 4A), mZac1b was a powerful coactivator for AR with the MMTV promoter in HeLa cells, either in the presence or absence of GRIP1 (Fig. 9A). In contrast, mZac1b had a relatively minor, if any, effect on AR with the same reporter gene in CV-1 monkey kidney cells in either the presence or absence of GRIP1. In 1471.1 cells, a mouse mammary cell line, mZac1b repressed AR function on the MMTV promoter in both the presence and absence of GRIP1. Similar tests were conducted with ER and the MMTV(ERE)-luciferase reporter gene (Fig. 9B) or the EREII(GL45)-LUC reporter gene (Fig. 9C). In HeLa cells and CV-1 cells, mZac1b had little or no effect on ER activity with the MMTV promoter in the absence of GRIP1 but strongly repressed the GRIP1-enhanced function of ER; however, in 1471.1 cells, mZac1b modestly enhanced ER function on this promoter, either in the presence or in the absence of GRIP1. However, with the EREII(GL45)-LUC reporter gene, mZac1b strongly enhanced ER function in HeLa cells and CV-1 cells but had little if any effect on 1471.1 cells. While mZac1b was sometimes a coactivator and sometimes a repressor, GRIP1 enhanced AR and ER function, albeit to various degrees, in all of these tests. Thus, mZac1b exhibited a unique ability to act as either a coactivator or repressor of NR function, depending on the type of NR, promoter context, and cellular context.

FIG. 9.

Variable coactivator or repressor roles of mZac1b with AR and ER in three cell lines. The cell lines indicated at the top were transfected with the reporter plasmid (0.5 μg) and NR expression vector indicated on the right (0.5 μg of AR vector and 0.04 μg of ER vector). Expression vectors for GRIP1 (0.5 μg) and/or mZac1b (0.5 μg) were included as indicated. For each data set, the luciferase activities are expressed relative to that observed in the absence of mZac1b and GRIP1. The data for HeLa cells are from Fig. 4A, 7A, and 8A.

Enhancement of GRIP1 and CBP activity by mZac1b.

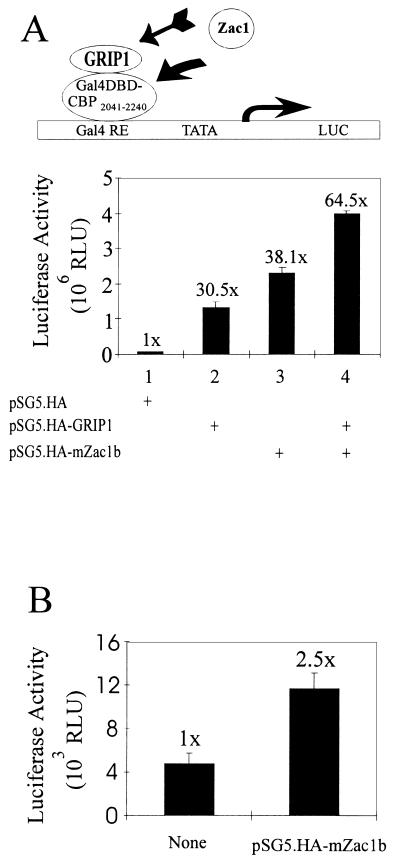

Since mZac1b bound to GRIP1 and CBP as well as directly to NRs, the coactivator and repressor effects of mZac1b on NRs could result from any of these physical interactions. To test the ability of mZac1b to enhance the function of CBP, the C-terminal region of CBP (amino acids 2041 to 2240), which binds to the AD1 region of GRIP1 (9, 60) and to mZac1b (Fig. 2E), was fused to the Gal4 DBD and tested in transiently transfected HeLa cells in the presence and absence of coexpressed mZac1b and/or GRIP1. By itself, the Gal4 DBD-CBP fusion protein activated a reporter gene with Gal4 binding sites. Coexpressed GRIP1 enhanced reporter gene activity 30-fold, mZac1b caused a 38-fold enhancement, and the effects of GRIP1 and mZac1b together were approximately additive (Fig. 10A). In a similar experiment, mZac1b enhanced the activity of full-length GRIP1 fused to the Gal4 DBD about 2.5-fold (Fig. 10B); the same degree of enhancement was obtained when the C-terminal region of GRIP1 was fused with the Gal4 DBD (data not shown). Thus, mZac1b dramatically enhanced the activity of a fragment of CBP that it binds to, but it only modestly enhanced the activity of the GRIP1 fragment that it binds to.

FIG. 10.

Coactivator effects of mZac1b with the Gal4 DBD fused to GRIP1 or a C-terminal fragment of CBP. (A) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with 0.5 μg of GK1 reporter plasmid, 0.5 μg of pM.CBP204–2240, and, where indicated, 0.5 μg of pSG5.HA-mZac1b and/or 0.5 μg of pSG5.HA-GRIP1. Numbers above the bars indicate activity relative to that of Gal4DBD-CBP2041–2240 in the absence of coactivators. The diagram at the top indicates the proposed mechanism of reporter gene activation; recruitment of mZac1b to the transcription complex could occur by mZac1b binding either to CBP or to GRIP1. Gal4 RE, Gal4-responsive elements in the GK1 promoter; TATA, the TATA box in the GK1 promoter; LUC, luciferase-coding region; rightward-pointing arrow, transcription start site. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of GK1 reporter plasmid, 0.5 μg of pM.GRIP1, and, where indicated, 0.5 μg of pSG5.HA-mZac1b. RLU, relative light units.

DISCUSSION

Diverse functions of Zac1.

The results presented here demonstrate that mZac1b can function as a powerful coactivator or repressor of NR function, depending on the specific NR, reporter gene promoter, and cell type employed. The cDNA sequence indicates that mZac1b is a new isoform of the originally discovered mouse Zac1 (here designated mZac1a); mZac1b is identical to mZac1a except for an additional 11 amino acids inserted after amino acid 567 of mZac1a. mZac1a was first identified in an expression cloning system as a protein that coupled with adenylate cyclase stimulation to activate a cyclic-AMP-responsive reporter gene (51). Zac1 has a number of unusual features. An N-terminal region containing seven C2H2 zinc fingers is followed by a central region composed of PLE and PMQ repeats and another proline-rich region; the C-terminal region contains a sequence rich in P, Q, and L followed by repeats of PE and E (Fig. 1).

Some functional attributes of Zac1 have been defined in studies conducted with the mouse, rat, and human Zac1 proteins. Zac1 has a sequence-specific DNA binding activity in the N-terminal zinc finger region, and its central regions act as a transcriptional activation domain when fused to the Gal4 DBD (Fig. 3) (32, 59). These findings suggest that Zac1 can function as a DNA-binding transcriptional activator protein. Specific target genes which are directly bound and activated by Zac1 have not been identified, but the type I PACAP receptor gene, which is activated by Zac1 expression, is one candidate (22). Induction of this receptor gene may account for the ability of Zac1 to stimulate cyclic-AMP-responsive reporter genes. Expression of Zac1 also induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in cell culture and prevented tumor growth in nude mice (51, 59).

The closest human homologue of mZac1, hZac1 (59), also called hLot1 (lost on transformation) (1, 2) and PLAGL1 (PLAG-like) (32), shares 69% amino acid identity with mZac1, but it lacks the central PLE and PMQ repeats as well as the C-terminal region containing the P-, Q-, and L-rich sequence and the PE and E repeats (Fig. 1). In spite of these differences hZac1 has similar functional attributes; it can also induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, and it has DNA binding and activation domains (59). The additional 11 amino acids found in mZac1b (amino acids 568 to 578) but not in mZac1a are located in the P-, Q-, and L-rich region of the originally reported mZac1a sequence; this region is missing in hZac1. Since mZac1a and hZac1 share similar functional attributes, we predict that mZac1a has coactivator properties similar to those reported here for mZac1b. In fact, a C-terminally truncated form of mZac1b consisting of amino acids 1 to 520 had a pattern of activity (data not shown) similar to that of full-length mZac1b (Fig. 9) in HeLa cells when tested with AR and the MMTV-LUC reporter gene and with ER and the EREII(GL45)-LUC and MMTV(ERE)-LUC reporter genes. Thus, neither the C-terminal region of Zac1 nor the 11-amino-acid insert of mZac1b is important for the specificity of Zac1 function as a coactivator or repressor.

Unlike mZac1, which was found to be highly expressed only in the pituitary gland (51), hZac1 is widely expressed (32, 59). A rat homologue, rLot1, which is 83% identical to mZac1, lacks the PLE and PMQ repeats in its central region, like hZac1, but retains the C-terminal P-, Q-, and L-rich sequence and the PE and E repeats that are missing from hZac1 (Fig. 1) (1). rLot1 is expressed in a limited number of normal rat tissues, including ovary, pancreas, testis, and uterus. The rather dramatic differences in the structure and range of expression of Zac1 in humans, mice, and rats are intriguing but remain unexplained. A wide range of expression would suggest the possibility that Zac1 may play an integral and ubiquitous role in regulating NR function. In contrast, a more tissue-specific expression pattern for Zac1 would suggest that Zac1 may be used more selectively as a modulator of NR function.

As the abilities of Zac1 to promote apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in cultured cells and to prevent tumor formation in nude mice might suggest, alterations in the Zac1 gene and its expression were found in association with several types of cancer. A marked decrease of rLot1 and hZac1 expression was observed in rat and human ovarian cancer cell lines (1, 2). The chromosomal location of the hZac1 genes is 6q25, a region that has been implicated in the formation of a wide variety of solid tumors (2, 59). A human gene called the PLAG1 gene (pleomorphic adenoma gene), which is related to the PLAGL1 gene (as noted above, PLAGL1 is the same as hZac1), is located at 8q12; two types of tumor-associated chromosomal translocations involving the PLAG1 gene result in ectopic expression of PLAG1 (32). Since PLAG1 is also a zinc finger protein that is presumed to be a DNA-binding transcriptional activator protein, ectopic expression of PLAG1 in tumors may be responsible for abnormal expression of other proteins that contribute to the transformed phenotype. Thus, increased or decreased expression of Zac1 and related proteins is connected with a wide variety of tumors in humans and other mammals. It will be interesting to investigate whether the effects of Zac1 on cell cycle, apoptosis, and tumor progression involve the protein's roles as a DNA-binding transcriptional activator, positively or negatively acting transcriptional cofactor, or both.

Mechanism of mZac1b coactivator and repressor function.

The enhancement or repression of reporter gene expression by mZac1b in the studies reported here depended completely on the presence of the NR and its hormone. These findings and the ability of mZac1b to bind the NRs and the NR coactivators suggest that mZac1b acts as a cofactor for NRs rather than as a DNA-binding transcription factor. However, since mZac1b interacts with NRs and two NR coactivators, the CBP and p160 coactivators, and since mZac1b enhanced (or in some cases repressed) transcriptional activation by NRs and the Gal4 DBD fused to GRIP1 or CBP, it is difficult to assess which of these interactions may be functionally important. In this regard, mZac1b is similar to the coactivator p/CAF, a histone acetyltransferase that enhances NR function and can also bind to NRs, p160 coactivators, and CBP (5, 9, 64).

While there is no direct evidence to indicate which protein binding activities of mZac1b are necessary for its cofactor activity with NRs, indirect evidence suggests that mZac1b may at least sometimes work through its direct contact with NR AF-2 domains. Expression of NRs in transient-transfection assays apparently makes the endogenous levels of coactivators, such as CBP and p160 coactivators, limiting for reporter gene activation by the NRs (8, 31). For example, cotransfection of expression vectors for the p160 coactivators in these assays enhanced reporter gene activity severalfold (Fig. 4A, 8A, and 9A) (41, 48, 60). However, mZac1b in some cases enhanced reporter gene activation by NRs, even in the absence of coexpressed GRIP1, 30- to 50-fold (Fig. 4A and 8A), suggesting that limiting levels of p160 coactivators did not prevent the action of mZac1b.

In contrast, another recently discovered coactivator, CARM1 (coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase), could not enhance NR function when p160 coactivators were limiting (8). CARM1, like mZac1b, bound to the C-terminal region of p160 coactivators; however, CARM1 did not bind directly to NRs. While the coactivator activity of mZac1b for NRs occurred in the presence or absence of coexpressed p160 coactivators, CARM1 coactivator function completely depended on the presence of the p160 coactivators. Thus, CARM1 acts as a secondary coactivator, recruited to the transcription complex through its binding to the primary p160 coactivators; by comparison, mZac1b enhanced NR function independently of the p160 coactivator status of the cells and thus may be recruited to the transcription complex through its direct contact with NR AF-2 domains.

This conclusion was supported by results with individual AR AF-1 and AF-2 domains. mZac1b bound AR AF-2 directly (Fig. 2C), and its ability to enhance AR AF-2 activity in HeLa cells was relatively GRIP1 independent (Fig. 5B). In contrast, mZac1b did not bind AR AF-1 (Fig. 2D), and its ability to enhance AR AF-1 activity was relatively dependent on coexpression of GRIP1 (Fig. 5A). One attractive explanation for these results is that mZac1b enhanced AF-2 activity through direct physical interaction with AF-2, but its enhancement of AF-1 depended on mZac1b binding to GRIP1. While many coactivators for NRs (including p160 coactivators) use LXXLL motifs to bind to the AF-2 functions of NRs (63), mZac1b must use another binding mechanism; mZac1b has only one LXXLL motif, and this motif is located in the C-terminal region, which is not required for binding to NRs (data not shown).

The repressor activity of mZac1b sometimes required the presence of GRIP1 and sometimes was GRIP1 independent (Fig. 9). Further studies are required to determine whether this repressor function occurs via physical interactions with NRs, p160 coactivators, or another cellular component. It will also be interesting to determine whether the repressive activity of mZac1b involves known NR corepressors, such as NCoR or SMRT, or the protein deacetylases associated with these corepressors (63). A recently identified ER-interacting protein, called repressor of estrogen receptor activity (REA) (45), was found to repress activity of agonist-activated ERα and -β, reminiscent of the repressor activity of mZac1. However, unlike mZac1, REA had no effect on other NRs tested and was not found to function as a coactivator in any of the cellular contexts tested.

Selectivity of the coactivator or repressor function of mZac1b.

The most unusual aspect of mZac1b is the polarity of its function. mZac1b is one of the most powerful coactivators reported to date, enhancing NR function as much as 50-fold. However, it functioned selectively as a cofactor for NRs, acting sometimes as a coactivator and sometimes as a repressor of NR function and sometimes as a functionally neutral protein. The selectivity of mZac1b action depended on the specific NR, cell line, and reporter gene promoter used, as well as the coexpression of p160 coactivators. However, changing the number of hormone response elements from one to two did not cause a switch in the polarity of the mZac1b effect. The ability of mZac1b to either enhance or inhibit gene activation by a particular NR, depending on the promoter and cell context, suggests that in a physiological setting the positive or negative activity of mZac1b could be regulated by the relative concentrations or activities of the cellular components (unknown at this point) which are responsible for the promoter and cell-type-specific activities of mZac1b reported here.

Two other examples of cofactors with demonstrated or potential polarity of action have been reported. Another recently identified NR-interacting protein, NSD1 (28), was found to interact with two different NR sites, the hinge region site known to bind the NCoR corepressors and the C-terminal AF-2 coactivator binding site. NSD1 possessed intrinsic activation and repression domains, suggesting that it may be able to function as a coactivator or corepressor for NRs; this possibility awaits further testing. The ability of mZac1b to enhance or repress transcription is reminiscent of the actions of transcription factor YY1 (yin yang 1) (14, 50). Like mZac1b, YY1 is a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein and can either enhance or repress transcription in a manner that depends on cell type and promoter. YY1 can bind many other transcriptional activator proteins and cofactors, such as CBP and E1A; its association with these proteins can alter and even reverse YY1 function between positive and negative. The ability of mZac1b and YY1 to bind many different proteins as well as specific DNA sequences suggests that they may function in some cases as DNA-binding transcription factors and in other cases as cofactors that are recruited to the promoter through their protein-protein rather than their protein-DNA interactions.

While mZac1b functioned as a strong coactivator for the hormone-activated AR in HeLa cells at all concentrations of DHT tested, mZac1b reversed the activating effect of GRIP1 on AR in the absence of hormone and also increased the concentration of DHT required for half-maximal activation of AR. These effects of mZac1b suggest a potential physiological role of Zac1 to prevent activation by other coactivators in the absence of hormone and in effect narrow the physiologically effective range of hormone concentrations. The fact that mZac1b can bind well to NRs in either the presence or absence of hormone, while p160 coactivators bind efficiently only to the hormone-occupied NR, may be responsible for the dominant effect of mZac1b over p160 coactivators at low hormone concentrations and in the absence of hormone.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank P. Webb and P. J. Kushner, W. Feng, and D. Pearce (University of California) for expression vectors and reporter genes for ER, TR, and MR, respectively; T.-P. Yao (Duke University) for the plasmid encoding GST-p3001571–2414; A. O. Brinkmann (Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands) and R. L. Miesfeld (University of Arizona) for AR expression vectors; G. L. Hager (National Institutes of Health) for 1471.1 cells; H. Ma and X. F. Ding (University of Southern California) for AR AF-1 and AF-2 expression vectors and for pGBT9.GRIP11121–1462, respectively; H. Hong and D. Chen (University of Southern California) for performing the initial stages of the yeast two-hybrid screen; and D. L. Johnson (University of Southern California) for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant DK55274 from the National Institutes of Health. S.-M. H. was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the Defense Department, Taiwan, Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdollahi A, Godwin A K, Miller P D, Getts L A, Schultz D C, Taguchi T, Testa J R, Hamilton T C. Identification of a gene containing zinc-finger motifs based on lost expression in malignantly transformed rat ovarian surface epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2029–2034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdollahi A, Roberts D, Godwin A K, Schultz D C, Sonoda G, Testa J R, Hamilton T C. Identification of a zinc-finger gene at 6q25: a chromosomal region implicated in development of many solid tumors. Oncogene. 1997;14:1973–1979. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anzick S L, Kononen J, Walker R L, Azorsa D O, Tanner M M, Guan X-Y, Sauter G, Kallioniemi O-P, Trent J M, Meltzer P S. AIB1, a steroid receptor coactivator amplified in breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1997;277:965–968. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beato M, Herrlich P, Schütz G. Steroid hormone receptors: many actors in search of a plot. Cell. 1995;83:851–857. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco J C, Minucci S, Lu J, Yang X J, Walker K K, Chen H, Evans R M, Nakatani Y, Ozato K. The histone acetylase PCAF is a nuclear receptor coactivator. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1638–1651. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinkmann A O, Faber P W, van Rooij H C J, Kuiper G G J M, Ris C, Klaassen P, van der Korput J A G M, Voorhorst M M, van Laar J H, Mulder E, Trapman J. The human androgen receptor: domain structure, genomic organization and regulation of expression. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1989;34:307–310. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(89)90098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chamberlain N C, Driver E D, Miesfeld R L. The length and location of CAG trinucleotide repeats in the androgen receptor N-terminal domain affect transactivation function. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3181–3186. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.15.3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen D, Ma H, Hong H, Koh S S, Huang S-M, Schurter B T, Aswad D W, Stallcup M R. Regulation of transcription by a protein methyltransferase. Science. 1999;284:2174–2177. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H, Lin R J, Schiltz R L, Chakravarti D, Nash A, Nagy L, Privalsky M L, Nakatani Y, Evans R M. Nuclear receptor coactivator ACTR is a novel histone acetyltransferase and forms a multimeric activation complex with P/CAF and CBP/p300. Cell. 1997;90:569–580. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80516-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danielian P S, White R, Lees J A, Parker M G. Identification of a conserved region required for hormone dependent transcriptional activation by steroid hormone receptors. EMBO J. 1992;11:1025–1033. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding X F, Anderson C M, Ma H, Hong H, Uht R M, Kushner P J, Stallcup M R. Nuclear receptor-binding sites of coactivators glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein 1 (GRIP1) and steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC-1): multiple motifs with different binding specificities. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:302–313. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.2.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doesburg P, Kuil C W, Berrevoets C A, Steketee K, Faber P W, Mulder E, Brinkmann A O, Trapman J. Functional in vivo interaction between the amino-terminal, transactivation domain and the ligand binding domain of the androgen receptor. Biochemistry. 1997;36:1052–1064. doi: 10.1021/bi961775g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durand B, Saunders M, Gaudon C, Roy B, Losson R, Chambon P. Activation function 2 (AF-2) of retinoic acid receptor and 9-cis retinoic acid receptor: presence of a conserved autonomous constitutive activating domain and influence of the nature of the response element on AF-2 activity. EMBO J. 1994;13:5370–5382. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ericsson J, Usheva A, Edwards P A. YY1 is a negative regulator of transcription of three sterol regulatory element-binding protein-responsive genes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14508–14513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans R M. The steroid and thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1988;240:889–895. doi: 10.1126/science.3283939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng W, Ribeiro R C J, Wagner R L, Nguyen H, Apriletti J W, Fletterick R J, Baxter J D, Kushner P J, West B L. Hormone-dependent coactivator binding to a hydrophobic cleft on nuclear receptors. Science. 1998;280:1747–1749. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fragoso G, Pennie W D, John S, Hager G L. The position and length of the steroid-dependent hypersensitive region in the mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat are invariant despite multiple nucleosome B frames. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3633–3644. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freedman L P. Increasing the complexity of coactivation in nuclear receptor signaling. Cell. 1999;97:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80708-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gluzman Y. SV40-transformed simian cells support the replication of early SV40 mutants. Cell. 1981;23:175–182. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green S, Issemann I, Sheer E. A versatile in vivo and in vitro eukaryotic expression vector for protein engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:369. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.1.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu W, Shi X L, Roeder R G. Synergistic activation of transcription by CBP and p53. Nature. 1997;387:819–823. doi: 10.1038/42972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffmann A, Ciani E, Houssami S, Brabet P, Journot L, Spengler D. Induction of type I PACAP receptor expression by the new zinc finger protein Zac1 and p53. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;865:49–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb11162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollenberg S M, Evans R M. Multiple and cooperative transactivation domains of the human glucocorticoid receptor. Cell. 1988;55:899–906. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong H, Darimont B D, Ma H, Yang L, Yamamoto K R, Stallcup M R. An additional region of coactivator GRIP1 required for interaction with the hormone-binding domains of a subset of nuclear receptors. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3496–3502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong H, Kohli K, Garabedian M J, Stallcup M R. GRIP1, a transcriptional coactivator for the AF-2 transactivation domain of steroid, thyroid, retinoid, and vitamin D receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2735–2744. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong H, Kohli K, Trivedi A, Johnson D L, Stallcup M R. GRIP1, a novel mouse protein that serves as a transcriptional co-activator in yeast for the hormone binding domains of steroid receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4948–4952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horwitz K B, Jackson T A, Bain D L, Richer J K, Takimoto G S, Tung L. Nuclear receptor coactivators and corepressors. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1167–1177. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.10.9121485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang N, vom Baur E, Garnier J M, Lerouge T, Vonesch J L, Lutz Y, Chambon P, Losson R. Two distinct nuclear receptor interaction domains in NSD1, a novel SET protein that exhibits characteristics of both corepressors and coactivators. EMBO J. 1998;17:3398–3412. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ikonen T, Palvimo J J, Jänne O A. Interaction between the amino- and carboxy-terminal regions of the rat androgen receptor modulates transcriptional activity and is influenced by nuclear receptor coactivators. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29821–29828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imhof A, Yang X-J, Ogryzko V V, Nakatani Y, Wolffe A P, Ge H. Acetylation of general transcription factors by histone acetyltransferases. Curr Biol. 1997;7:689–692. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamei Y, Xu L, Heinzel T, Torchia J, Kurokawa R, Gloss B, Lin S-C, Heyman R A, Rose D W, Glass C K, Rosenfeld M G. A CBP integrator complex mediates transcriptional activation and AP-1 inhibition by nuclear receptors. Cell. 1996;85:403–414. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kas K, Voz M L, Hensen K, Meyen E, Van de Ven W J. Transcriptional activation capacity of the novel PLAG family of zinc finger proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23026–23032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawasaki H, Song J, Eckner R, Ugai H, Chiu R, Taira K, Shi Y, Jones N, Yokoyama K K. p300 and ATF-2 are components of the DRF complex, which regulates retinoic acid- and E1A-mediated transcription of the c-jun gene in F9 cells. Genes Dev. 1998;12:233–245. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korzus E, Torchia J, Rose D W, Xu L, Kurokawa R, McInerney E M, Mullen T-M, Glass C K, Rosenfeld M G. Transcription factor-specific requirements for coactivators and their acetyltransferase functions. Science. 1998;279:703–707. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5351.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraus W L, McInerney E M, Katzenellenbogen B S. Ligand-dependent, transcriptionally productive association of the amino- and carboxyl-terminal regions of a steroid hormone nuclear receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12314–12318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langley E, Zhou Z X, Wilson E M. Evidence for an anti-parallel orientation of the ligand-activated human androgen receptor dimer. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29983–29990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.29983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lees J A, Fawell S E, Parker M G. Identification of two transactivation domains in the mouse oestrogen receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:5477–5489. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.14.5477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, Gomes P J, Chen J D. RAC3, a steroid/nuclear receptor-associated coactivator that is related to SRC-1 and TIF2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8479–8484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luger K, Mäder A W, Richmond R K, Sargent D F, Richmond T J. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luger K, Richmond T J. The histone tails of the nucleosome. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:140–146. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma H, Hong H, Huang S-M, Irvine R A, Webb P, Kushner P J, Coetzee G A, Stallcup M R. Multiple signal input and output domains of the 160-kilodalton nuclear receptor coactivator proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6164–6173. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mangelsdorf D J, Evans R M. The RXR heterodimers and orphan receptors. Cell. 1995;83:841–850. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McInerney E M, Tsai M-J, O'Malley B W, Katzenellenbogen B S. Analysis of estrogen receptor transcriptional enhancement by a nuclear hormone receptor coactivator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10069–10073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Milhon J, Kohli K, Stallcup M R. Genetic analysis of the N-terminal end of the glucocorticoid receptor hormone binding domain. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1994;51:11–19. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(94)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Montano M M, Ekena K, Delage-Mourroux R, Chang W, Martini P, Katzenellenbogen B S. An estrogen receptor-selective coregulator that potentiates the effectiveness of antiestrogens and represses the activity of estrogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6947–6952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ogryzko V V, Schiltz R L, Russanova V, Howard B H, Nakatani Y. The transcriptional coactivators p300 and CBP are histone acetyltransferases. Cell. 1996;87:953–959. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)82001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oñate S A, Boonyaratanakornkit V, Spencer T E, Tsai S Y, Tsai M-J, Edwards D P, O'Malley B W. The steroid receptor coactivator-1 contains multiple receptor interacting and activation domains that cooperatively enhance the activation function 1 (AF1) and AF2 domains of steroid receptors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12101–12108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oñate S A, Tsai S Y, Tsai M-J, O'Malley B W. Sequence and characterization of a coactivator for the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1995;270:1354–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paech K, Webb P, Kuiper G G J M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson J-A, Kushner P J, Scanlan T S. Differential ligand activation of estrogen receptors ERα and ERβ at AP1 sites. Science. 1997;277:1508–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi Y, Lee J S, Galvin K M. Everything you have ever wanted to know about Yin Yang 1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1332:F49–F66. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(96)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spengler D, Villalba M, Hoffmann A, Pantaloni C, Houssami S, Bockaert J, Journot L. Regulation of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by Zac1, a novel zinc finger protein expressed in the pituitary gland and the brain. EMBO J. 1997;16:2814–2825. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Struhl K. Histone acetylation and transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. Genes Dev. 1998;12:599–606. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.5.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Swope D L, Mueller C L, Chrivia J C. CREB-binding protein activates transcription through multiple domains. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28138–28145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takeshita A, Cardona G R, Koibuchi N, Suen C-S, Chin W W. TRAM-1, a novel 160-kDa thyroid hormone receptor activator molecule, exhibits distinct properties from steroid receptor coactivator-1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27629–27634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Torchia J, Glass C, Rosenfeld M G. Co-activators and co-repressors in the integration of transcriptional responses. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Torchia J, Rose D W, Inostroza J, Kamei Y, Westin S, Glass C K, Rosenfeld M G. The transcriptional co-activator p/CIP binds CBP and mediates nuclear-receptor function. Nature. 1997;387:677–684. doi: 10.1038/42652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsai M-J, O'Malley B W. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:451–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Umesono K, Evans R M. Determinants of target gene specificity for steroid/thyroid hormone receptors. Cell. 1989;57:1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Varrault A, Ciani E, Apiou F, Bilanges B, Hoffmann A, Pantaloni C, Bockaert J, Spengler D, Journot L. hZAC encodes a zinc finger protein with antiproliferative properties and maps to a chromosomal region frequently lost in cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8835–8840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Voegel J J, Heine M J S, Tini M, Vivat V, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H. The coactivator TIF2 contains three nuclear receptor binding motifs and mediates transactivation through CBP binding-dependent and -independent pathways. EMBO J. 1998;17:507–519. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Voegel J J, Heine M J S, Zechel C, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H. TIF2, a 160 kDa transcriptional mediator for the ligand-dependent activation function AF-2 of nuclear receptors. EMBO J. 1996;15:3667–3675. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Webb P, Nguyen P, Shinsako J, Anderson C, Feng W, Nguyen M P, Chen D, Huang S-M, Subramanian S, McKinerney E, Katzenellenbogen B S, Stallcup M R, Kushner P J. Estrogen receptor activation function 1 works by binding p160 coactivator proteins. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:1605–1618. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.10.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu L, Glass C K, Rosenfeld M G. Coactivator and corepressor complexes in nuclear receptor function. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:140–147. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang X-J, Ogryzko V V, Nishikawa J, Howard B H, Nakatani Y. A p300/CBP-associated factor that competes with the adenoviral oncoprotein E1A. Nature. 1996;382:319–324. doi: 10.1038/382319a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yao T-P, Ku G, Zhou N, Scully R, Livingston D M. The nuclear hormone receptor coactivator SRC-1 is a specific target of p300. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10626–10631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]