Abstract

Since 2015 the gravitational-wave observations of LIGO and Virgo have transformed our understanding of compact-object binaries. In the years to come, ground-based gravitational-wave observatories such as LIGO, Virgo, and their successors will increase in sensitivity, discovering thousands of stellar-mass binaries. In the 2030s, the space-based LISA will provide gravitational-wave observations of massive black holes binaries. Between the –103 Hz band of ground-based observatories and the –10− 1 Hz band of LISA lies the uncharted decihertz gravitational-wave band. We propose a Decihertz Observatory to study this frequency range, and to complement observations made by other detectors. Decihertz observatories are well suited to observation of intermediate-mass (–104M⊙) black holes; they will be able to detect stellar-mass binaries days to years before they merge, providing early warning of nearby binary neutron star mergers and measurements of the eccentricity of binary black holes, and they will enable new tests of general relativity and the Standard Model of particle physics. Here we summarise how a Decihertz Observatory could provide unique insights into how black holes form and evolve across cosmic time, improve prospects for both multimessenger astronomy and multiband gravitational-wave astronomy, and enable new probes of gravity, particle physics and cosmology.

Keywords: Gravitational waves, Decihertz observatories, Multiband gravitational-wave astronomy, Multimessenger astronomy, Space-based detectors, Black holes, Neutron stars, White dwarfs, Stochastic backgrounds, Binary evolution, Intermediate-mass black holes, Tests of general relativity, Voyage 2050

The gravitational-wave spectrum

When new frequency ranges of the electromagnetic spectrum became open to astronomy, our understanding of the Universe expanded as we gained fresh insights and discovered new phenomena [1]. Equivalent breakthroughs are awaiting gravitational-wave (GW) astronomy [2, 3]. Here, we summarise the scientific potential of exploring the –1Hz GW spectrum.

The first observation of a GW signal was made in 2015 by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) [3]. Ground-based detectors such as LIGO [4], Virgo [5], and KAGRA [6] observe over a frequency spectrum –103 Hz. This is well tailored to the detection of merging stellar-mass black hole (BH) and neutron star (NS) binaries [7]. Next-generation ground-based detectors, like Cosmic Explorer [8] or the Einstein Telescope [9, 10] may observe down to a few hertz. Only a small part of the GW spectrum can thus be observed by ground-based detectors, and extending to lower frequencies requires space-based observatories.

Lower frequency GW signals originate from coalescences of more massive binaries, and stellar-mass binaries earlier in their inspirals. Due for launch in 2034, the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) will observe across frequencies –10− 1 Hz [11], optimal for mergers of binaries with massive BHs [12–14]. LISA will be able to observe nearby stellar-mass binary BHs (BBHs) years–days prior to merger [15], when they could be observed by ground-based detectors. Multiband observations of BBHs would provide improved measurements of source properties [16–18], new constraints on their formation channels [19, 20], and enable precision tests of general relativity (GR) [16, 21].

Pulsar timing arrays are sensitive to even lower frequency GWs of –10− 7 Hz [22], permitting observation of supermassive BHs [23]. Combining LISA and pulsar timing observations will produce new insights into the evolution of (super)massive BHs [24, 25].

The case for extending the accessible GW spectrum with an observatory that can observe in the –1 Hz decihertz range is explained in [26], based upon a White Paper that we submitted in response to ESA’s Voyage 2050 call, and here we summarise the highlights. Decihertz observations would:

Reveal the formation channels of stellar-mass binaries, complementing ground-based observations with deep multiband observations.

Complete our census of the population of BHs by enabling unrivaled measurements of intermediate-mass BHs (IMBHs), which may be the missing step in the evolution of (super)massive BHs.

Provide a new laboratory for tests of fundamental physics.

Decihertz observatories (DOs) have the capability to resolve outstanding questions about the intricate physics of binary stellar evolution, the formation of astrophysical BHs at all scales across cosmic time, and whether extensions to GR or the Standard Model of particle physics are required.

The potential of decihertz observatories

Decihertz observations would bridge space-based low-frequency detectors and ground-based detectors, giving us access to a wide variety of astrophysical systems:

Stellar-mass binaries comprised of compact stellar objects—white dwarfs (WDs), NSs, and stellar-mass BHs. Since BH and NS mergers are observable with ground-based detectors, a DO would allow multiband observations of these populations. WDs are inaccessible to ground-based detectors [27], and so can only be studied with space-based detectors. While the current-generation of ground-based detectors will detect stellar-mass BBHs to redshifts –2, next-generation detectors will discover them out to , enabling them to chart the evolution of the binary population across the history of the Universe [28]; a DO could match this range, far surpassing LISA. Furthermore, decihertz observations of compact-object mergers would provide valuable forewarning of multimessenger emission associated with merger events. If detected, multimessenger observations reveal details about the equation of state of nuclear density matter [29–33], the production of heavy elements [34–38], and provide a unique laboratory for testing gravity [39–42], as well as potentially identifying the progenitors of Type Ia supernovae [43–45]. Even without finding a counterpart, correlation with galaxy catalogues can provide standard siren cosmological measurements [46–53]. Following their detection by LIGO and Virgo, BHs and NSs are a guaranteed class of GW source [3, 7, 54]. With a large number of observations, we can infer the formation channels for compact-object binaries, and the physics that governs them [28, 55–62]. Eccentricity is a strong indicator of formation mechanism [19, 20, 63–66]; however, residual eccentricity is expected to be small in the regime observable with ground-based detectors [67–70] while in some cases, BBHs formed with the highest eccentricities will emit GWs of frequencies too high for LISA [65, 71–76]. Hence DOs could provide unique insights into binary evolution.

IMBHs of –104M⊙. IMBHs could be formed via repeated mergers of stars and compact stellar remnants in dense star clusters [77–80]. Using GWs, IMBHs could be observed in a binary with a compact stellar remnant as an intermediate mass-ratio inspiral (IMRI) [81–84], or in a coalescing binary with another IMBH. A DO would enhance the prospects of IMRI detection to tens of events per year, with observations extending out to high redshift. Mergers involving a WD or a NS can lead to tidal disruption events with a bright electromagnetic counterpart [85, 86]. IMBHs binaries could be studied across the entire history of the Universe, charting the properties of this population and constraining the upper end of the pair-instability mass gap [87], while also providing a detailed picture of the connection (or lack thereof) between IMBHs and the seeds of massive black holes [88]. The connection between massive BHs and their lower-mass counterparts could be further explored through observations of binaries orbiting massive BHs in galactic centres, or around IMBHs in smaller clusters [76, 89–97]. BBH–IMBH systems are a target for DO–ground-based multiband observation because they emit both 1–102 Hz GWs and simultaneously 0.01–1 Hz GWs.

Cosmological sources as part of a stochastic GW background (SGWB). Both this and the other astrophysical sources serve as probes of new physics, enabling tests of deviations from GR and the Standard Model. A first-order phase transition in the early Universe can generate a SGWB [98–103]; a DO would be sensitive to first-order phase transitions occurring at higher temperature, or with a shorter duration, compared to LISA. A DO would be sensitive to a SGWB from a source at and beyond: TeV-scale phenomena have been consider to resolve with the hierarchy problem or the question of dark matter [104–109], while 100 TeV-scale phenomena appear in new solutions to the hierarchy problem such as the relaxion [110, 111]. Furthermore, SGWB (non-)detection could constrain the properties of cosmic strings [112, 113] down to string tensions of , while LISA would reach [114] and pulsar timing array observations currently constrain tensions to be [115, 116].

Decihertz observations provide a unique insight into the physics of each of these sources, and observations would answer questions on diverse topics ranging from the dynamics of globular clusters to the nature of dark matter.

Decihertz mission concepts

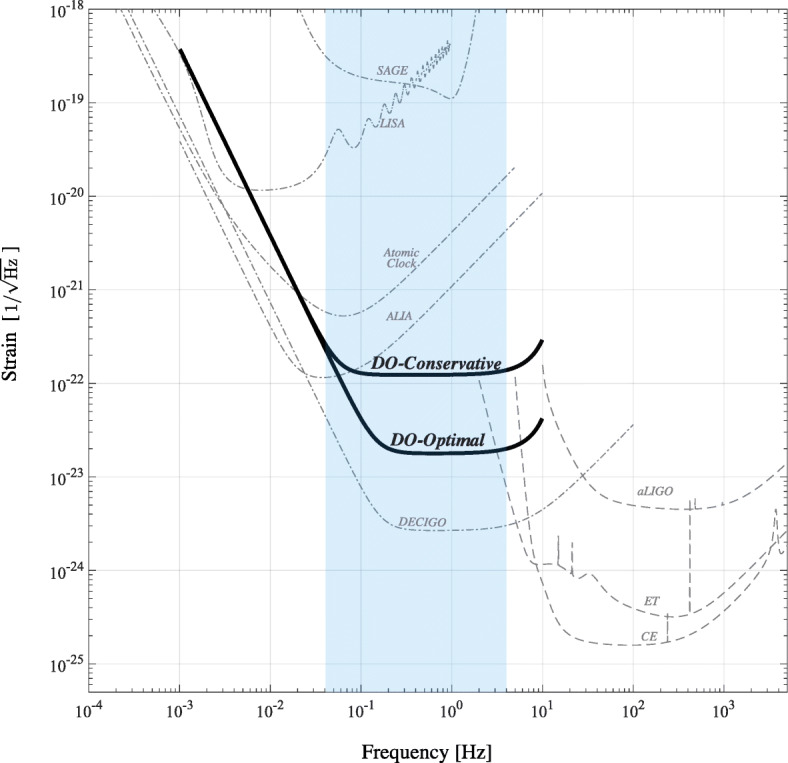

The scientific return of a DO will depend upon its design. There are multiple potential technologies and mission concepts for observing the 0.01–1 Hz GW spectrum. The Advanced Laser Interferometer Antenna (ALIA) [117, 118] is a heliocentric mission concept more sensitive than LISA in the 0.1–1 Hz range. Other heliocentric DO concepts are Taiji [119, 120], most sensitive around 0.01 Hz, and TianGo [121], most sensitive in the 0.1–10 Hz range. TianQin [122] is a Chinese geocentric mission concept. The DECi-hertz Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (DECIGO) [123, 124] is a more ambitious concept with 1000 km Fabry–Perot cavity arms in heliocentric orbit; its precursor B-DECIGO would be a 100 km triangular interferometer in a geocentric orbit. The Big Bang Observer (BBO) is a concept consisting of four LISA detectors in heliocentric orbits with combined peak sensitivity over 0.1–1 Hz range [125]. More modest designs are the Geostationary Antenna for Disturbance-Free Laser Interferometry (GADFLI) [126] and geosynchronous Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (gLISA) [127, 128] which are geocentric concepts. The SagnAc interferometer for Gravitational wavE (SAGE) [129, 130] consists of three identical CubeSats in geosynchronous orbit. These concepts are mostly variations on the classic LISA design of a laser interferometer. In addition to laser interferometry, atomic-clock-based [131, 132] and atom interferometer concepts are in development; for example, the Mid-band Atomic Gravitational Wave Interferometric Sensor (MAGIS) [133] and the Atomic Experiment for Dark Matter and Gravity Exploration in Space (AEDGE) [134] designs use atom interferometry. The range of technologies available mean that there are multiple possibilities for obtaining the necessary sensitivity in the decihertz range. Two illustrative LISA-like designs, the more ambitious DO-Optimal and the less challenging DO-Conservative, are presented in [26] to assess the potential range of science achievable with DOs. Potential sensitivity of DOs are illustrated in Fig. 1 in comparison to other gravitational-wave observatories.

Fig. 1.

Concept designs for Decihertz Observatories (DOs) fill the gap between LISA [11] and ground-based detectors like Advanced LIGO (aLIGO) [4], Cosmic Explorer (CE) [8] and the Einstein Telescope (ET) [10]. The example DO concepts SAGE [129, 130], Atomic Clock [26, 131], ALIA [117, 118], DO-Conservative, DO-Optimal [26, 135] and DECIGO [123, 124] span a diverse set of technologies and illustrate the potential range in sensitivities

Summary

Observing GWs in the decihertz range presents huge opportunities for advancing our understanding of both astrophysics and fundamental physics. The only prospect for decihertz observations is a space-based DO. Realising the rewards of these observations will require development of new detectors beyond LISA. There are many challenges in meeting the requirements of DO concepts; however, there are also many promising technologies that could be developed to meet these goals. A DO mission ready for launch in 2035–2050 is achievable, and the science payoff is worth the experimental effort.

Acknowledgements

This summary is derived from a White Paper submitted 4 August 2019 to ESA’s Voyage 2050 planning cycle on behalf of the LISA Consortium 2050 Task Force [135]. Further space-based GW observatories considered by the LISA Consortium 2050 Task Force include a microhertz observatory μAres [136]; a more sensitive millihertz observatory, the Advanced Millihertz Gravitational-wave Observatory (AMIGO) [137], and a high angular-resolution observatory consisting of multiple DOs [138].

The authors thanks Pete Bender for insightful comments, and Adam Burrows and David Vartanyan for further suggestions. MAS acknowledges financial support from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Project-ID 138713538 – SFB 881 (“The Milky Way System”). CPLB is supported by the CIERA Board of Visitors Research Professorship. PAS acknowledges support from the Ramón y Cajal Programme of the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness of Spain, as well as the COST Action GWverse CA16104. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFA0400702) and the National Science Foundation of China (11721303). TB is supported by The Royal Society (grant URF∖R1∖180009). EB is supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) Grants No. PHY-1912550 and AST-1841358, NASA ATP Grants No. 17-ATP17-0225 and 19-ATP19-0051, NSF-XSEDE Grant No. PHY-090003, and by the Amaldi Research Center, funded by the MIUR program “Dipartimento di Eccellenza” (CUP: B81I18001170001). This work has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 690904. DD acknowledges financial support via the Emmy Noether Research Group funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under grant no. DO 1771/1-1 and the Eliteprogramme for Postdocs funded by the Baden-Wurttemberg Stiftung. JME is supported by NASA through the NASA Hubble Fellowship grant HST-HF2-51435.001-A awarded by the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., for NASA, under contract NAS5-26555. MLK acknowledges support from the NSF under grant DGE-0948017 and the Chateaubriand Fellowship from the Office for Science & Technology of the Embassy of France in the United States. GN is partly supported by the ROMFORSK grant Project No. 302640 ‘‘Gravitational Wave Signals From Early Universe Phase Transitions''. IP acknowledges funding by Society in Science, The Branco Weiss Fellowship, administered by the ETH Zurich. AS is supported by the European Union’s H2020 ERC Consolidator Grant “Binary massive black hole astrophysics” (grant agreement no. 818691 – B Massive). LS was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11975027, 11991053, 11721303), the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by the China Association for Science and Technology (2018QNRC001), and the Max Planck Partner Group Program funded by the Max Planck Society. NW is supported by a Royal Society–Science Foundation Ireland University Research Fellowship (grant UF160093).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Longair M. The Cosmic Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sathyaprakash BS, Schutz BF. Physics, astrophysics and cosmology with gravitational waves. Living Rev. Rel. 2009;12:2. doi: 10.12942/lrr-2009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbott BP, et al. Observation of gravitational waves from a binary black hole merger. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016;116(6):061102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.061102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aasi J, et al. Advanced LIGO. Class. Quant. Grav. 2015;32:074001. doi: 10.1088/0264-9381/32/11/115012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acernese F, et al. Advanced Virgo: A second-generation interferometric gravitational wave detector. Class. Quant. Grav. 2015;32(2):024001. doi: 10.1088/0264-9381/32/2/024001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akutsu T, et al. KAGRA: 2.5 generation interferometric gravitational wave detector. Nature Astron. 2019;3(1):35. doi: 10.1038/s41550-018-0658-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbott BP, et al. GWTC-1: A gravitational-wave transient catalog of compact binary mergers observed by LIGO and Virgo during the first and second observing runs. Phys. Rev. 2019;x9(3):031040. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevX.9.031040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbott BP, et al. Exploring the sensitivity of next generation gravitational wave detectors. Class. Quant. Grav. 2017;34(4):044001. doi: 10.1088/1361-6382/aa51f4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sathyaprakash B, et al. Scientific objectives of einstein telescope. Class. Quant. Grav. 2012;29:124013. doi: 10.1088/0264-9381/29/12/124013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hild S, et al. Sensitivity studies for third-generation gravitational wave observatories. Class. Quant. Grav. 2011;28:094013. doi: 10.1088/0264-9381/28/9/094013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amaro-Seoane, P, et al.: Laser interferometer space antenna. arXiv:1702.00786 (2017)

- 12.Klein A, et al. Science with the space-based interferometer eLISA: Supermassive black hole binaries. Phys. Rev. 2016;d93(2):024003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Babak S, Gair J, Sesana A, Barausse E, Sopuerta CF, Berry CPL, Berti E, Amaro-Seoane P, Petiteau A, Klein A. Science with the space-based interferometer LISA. V: Extreme mass-ratio inspirals. Phys. Rev. 2017;d95(10):103012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berry CPL, Hughes SA, Sopuerta CF, Chua AJK, Heffernan A, Holley-Bockelmann K, Mihaylov DP, Miller MC, Sesana A. The unique potential of extreme mass-ratio inspirals for gravitational-wave astronomy. Bull. Am. Astron. Soc. 2019;51(3):42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sesana A. Prospects for Multiband gravitational-wave astronomy after GW150914. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016;116(23):231102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.231102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitale S. Multiband gravitational-wave astronomy: Parameter estimation and tests of general relativity with space- and ground-based detectors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016;117(5):051102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.051102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jani K, Shoemaker D, Cutler C. Detectability of intermediate-mass black holes in Multiband gravitational wave astronomy. Nature Astron. 2019;4(3):260. doi: 10.1038/s41550-019-0932-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu C, Shao L, Zhao J, Gao Y. Multiband observation of LIGO/Virgo binary black hole mergers in the gravitational-wave transient catalog GWTC-1. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2020;496:182. doi: 10.1093/mnras/staa1512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breivik K, Rodriguez CL, Larson SL, Kalogera V, Rasio FA. Distinguishing between formation channels for binary black holes with LISA. Astrophys. J. 2016;830(1):L18. doi: 10.3847/2041-8205/830/1/L18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishizawa A, Berti E, Klein A, Sesana A. eLISA eccentricity measurements as tracers of binary black hole formation. Phys. Rev. 2016;d94(6):064020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toubiana A, Marsat S, Babak S, Barausse E, Baker J. Tests of general relativity with stellar-mass black hole binaries observed by LISA. Phys. Rev. 2020;d101(10):104038. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manchester RN. The international pulsar timing array. Quant, Class. Grav. 2013;30:224010. doi: 10.1088/0264-9381/30/22/224010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mingarelli CMF, Lazio TJW, Sesana A, Greene JE, Ellis JA, Ma CP, Croft S, Burke-Spolaor S, Taylor SR. The local Nanohertz gravitational-wave landscape from supermassive black hole binaries. Nature Astron. 2017;1(12):886. doi: 10.1038/s41550-017-0299-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pitkin M, Clark J, Hendry MA, Heng IS, Messenger C, Toher J, Woan G, Phys J. Is there potential complementarity between LISA and pulsar timing? Conf. Ser. 2008;122:012004. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/122/1/012004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colpi M, et al. The gravitational wave view of massive black holes. Bull. Am. Astron. Soc. 2019;51(3):432. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sedda MA, et al. The missing link in gravitational-wave astronomy: Discoveries waiting in the decihertz range. Class. Quant. Grav. 2020;37(21):215011. doi: 10.1088/1361-6382/abb5c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Littenberg TB, Breivik K, Brown WR, Eracleous M, Hermes JJ, Holley-Bockelmann K, Kremer K, Kupfer T, Larson SL. Gravitational wave survey of galactic ultra compact binaries. Bull. Am. Astron. Soc. 2019;51(3):34. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalogera V, et al. Deeper, Wider, Sharper: Next-generation ground-based gravitational-wave observations of binary black holes. Bull. Am. Astron. Soc. 2019;51(3):242. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abbott BP, et al. GW170817: Measurements of neutron star radii and equation of state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018;121(16):161101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.161101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montana G, Tolos L, Hanauske M, Rezzolla L. Constraining twin stars with GW170817. Phys. Rev. 2019;d99(10):103009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Most ER, Weih LR, Rezzolla L, Schaffner-Bielich J. New constraints on radii and tidal deformabilities of neutron stars from GW170817. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018;120(26):261103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.261103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coughlin MW, Dietrich T, Margalit B, Metzger BD. Multimessenger Bayesian parameter inference of a binary neutron star merger. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2019;489(1):L91. doi: 10.1093/mnrasl/slz133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Margalit B, Metzger BD. The multi-messenger matrix: The future of neutron star merger constraints on the nuclear equation of state. Astrophys. J. 2019;880(1):L15. doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/ab2ae2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abbott BP, et al. Estimating the contribution of dynamical ejecta in the Kilonova associated with GW170817. Astrophys. J. 2017;850(2):L39. doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/aa9478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chornock R, et al. The electromagnetic counterpart of the binary neutron star merger LIGO/Virgo GW170817. IV. Detection of Near-infrared Signatures of r-process Nucleosynthesis with Gemini-South. Astrophys. J. 2017;848(2):L19. doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/aa905c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanvir NR, et al. The emergence of a Lanthanide-Rich Kilonova following the merger of two neutron stars. Astrophys. J. 2017;848(2):L27. doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/aa90b6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wanajo S. Physical conditions for the r-process I. radioactive energy sources of kilonovae. Astrophys. J. 2018;868(1):65. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aae0f2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siegel DM, Barnes J, Metzger BD. The neutron star merger GW170817 points to collapsars as the main r-process source. Nature. 2019;569(7755):241. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abbott BP, et al. Gravitational waves and gamma-rays from a binary neutron star merger: GW170817 and GRB 170817A. Astrophys. J. 2017;848(2):L13. doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/aa920c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abbott BP, et al. Tests of general relativity with GW170817. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019;123(1):011102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.123.011102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belgacem E, Dirian Y, Foffa S, Maggiore M. Modified gravitational-wave propagation and standard sirens. Phys. Rev. 2018;d98(2):023510. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belgacem E, et al. Testing modified gravity at cosmological distances with LISA standard sirens. JCAP. 2019;1907(07):024. doi: 10.1088/1475-7516/2019/07/024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hillebrandt W, Kromer M, Röpke FK, Ruiter AJ. Towards an understanding of Type Ia supernovae from a synthesis of theory and observations. Front. Phys. (Beijing) 2013;8:116. doi: 10.1007/s11467-013-0303-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maoz D, Mannucci F, Nelemans G. Observational clues to the progenitors of Type-Ia supernovae. Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2014;52:107. doi: 10.1146/annurev-astro-082812-141031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mandel I, Sesana A, Vecchio A. The astrophysical science case for a decihertz gravitational-wave detector. Class. Quant. Grav. 2018;35(5):054004. doi: 10.1088/1361-6382/aaa7e0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schutz BF. Determining the hubble constant from gravitational wave observations. Nature. 1986;323:310. doi: 10.1038/323310a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.MacLeod CL, Hogan CJ. Precision of Hubble constant derived using black hole binary absolute distances and statistical redshift information. Phys. Rev. 2008;D77:043512. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen HY, Fishbach M, Holz DE. A two per cent Hubble constant measurement from standard sirens within five years. Nature. 2018;562(7728):545. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abbott BP, et al. A gravitational-wave measurement of the Hubble constant following the second observing run of Advanced LIGO and Virgo. Astrophys. J. 2021;909(2):218. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/abdcb7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kyutoku K, Seto N. Gravitational-wave cosmography with LISA and the Hubble tension. Phys. Rev. 2017;d95(8):083525. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Del Pozzo W, Sesana A, Klein A. Stellar binary black holes in the LISA band: a new class of standard sirens. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2018;475(3):3485. doi: 10.1093/mnras/sty057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cutler C, Holz DE. Ultra-high precision cosmology from gravitational waves. Phys. Rev. 2009;D80:104009. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nishizawa A, Taruya A, Saito S. Tracing the redshift evolution of Hubble parameter with gravitational-wave standard sirens. Phys. Rev. 2011;D83:084045. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abbott, R., et al.: GWTC-2: Compact Binary Coalescences observed by LIGO and Virgo during the first half of the third observing run. arXiv:2010.14527 (2020)

- 55.Mandel I, O’Shaughnessy R. Compact binary Coalescences in the band of ground-based gravitational-wave detectors. Class. Quant. Grav. 2010;27:114007. doi: 10.1088/0264-9381/27/11/114007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stevenson S, Berry CPL, Mandel I. Hierarchical analysis of gravitational-wave measurements of binary black hole spinorbit misalignments. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2017;471(3):2801. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stx1764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Talbot C, Thrane E. Determining the population properties of spinning black holes. Phys. Rev. 2017;d96(2):023012. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zevin M, Pankow C, Rodriguez CL, Sampson L, Chase E, Kalogera V, Rasio FA. Constraining formation models of binary black holes with gravitational-wave observations. Astrophys. J. 2017;846(1):82. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aa8408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barrett JW, Gaebel SM, Neijssel CJ, Vigna-Gómez A, Stevenson S, Berry CPL, Farr WM, Mandel I. Accuracy of inference on the physics of binary evolution from gravitational-wave observations. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2018;477(4):4685. doi: 10.1093/mnras/sty908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arca Sedda M, Benacquista M. Using final black hole spins and masses to infer the formation history of the observed population of gravitational wave sources. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2019;482(3):2991. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arca Sedda M, Mapelli M, Spera M, Benacquista M, Giacobbo N. Fingerprints of binary black hole formation channels encoded in the mass and spin of merger remnants. Astrophys. J. 2020;894(2):133. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ab88b2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Farmer R, Renzo M, de Mink S, Fishbach M, Justham S. Constraints from gravitational wave detections of binary black hole mergers on the $^{12}\mathrm {C}\left (\alpha ,\gamma \right )^{16}\!\mathrm {O}$12C α,γ16O rate. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2020;902(2):L36. doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/abbadd. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nishizawa A, Sesana A, Berti E, Klein A. Constraining stellar binary black hole formation scenarios with eLISA eccentricity measurements. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2017;465(4):4375. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stw2993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Canuel B, et al. Exploring gravity with the MIGA large scale atom interferometer. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):14064. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32165-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kremer K, Chatterjee S, Breivik K, Rodriguez CL, Larson SL, Rasio FA. LISA sources in Milky Way globular clusters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018;120(19):191103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.191103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Randall, L., Xianyu, Z.Z.: Eccentricity without measuring eccentricity: Discriminating among stellar mass black hole binary formation channels. arXiv:1907.02283 (2019)

- 67.Peters PC. Gravitational radiation and the motion of two point masses. Phys. Rev. 1964;136:B1224. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.136.B1224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abbott BP, et al. Astrophysical implications of the binary black-hole merger GW150914. Astrophys. J. 2016;818(2):L22. doi: 10.3847/2041-8205/818/2/L22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Samsing J, Ramirez-Ruiz E. On the assembly rate of highly eccentric binary black hole mergers. Astrophys. J. 2017;840(2):L14. doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/aa6f0b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rodriguez CL, Amaro-Seoane P, Chatterjee S, Kremer K, Rasio FA, Samsing J, Ye CS, Zevin M. Post-Newtonian dynamics in dense star clusters: Formation, Masses, and merger rates of highly-eccentric black hole binaries. Phys. Rev. 2018;d98(12):123005. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.151101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Randall L, Xianyu ZZ. A direct probe of mass density near inspiraling binary black holes. Astrophys. J. 2019;878(2):75. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ab20c6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.D’Orazio DJ, Samsing J. Black hole mergers from globular clusters observable by LISA II: Resolved eccentric sources and the gravitational wave background. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2018;481(4):4775. doi: 10.1093/mnras/sty2568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arca-Sedda, M., Li, G., Kocsis, B.: Ordering the chaos: stellar black hole mergers from non-hierarchical triples. arXiv:1805.06458 (2018)

- 74.Kremer K, et al. Post-Newtonian dynamics in dense star clusters: Binary black holes in the LISA Band. Phys. Rev. 2019;d99(6):063003. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zevin M, Samsing J, Rodriguez C, Haster CJ, Ramirez-Ruiz E. Eccentric black hole mergers in dense star clusters: The Role of Binary Encounters. Astrophys. J. 2019;871(1):91. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aaf6ec. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen X, Amaro-Seoane P. Revealing the formation of stellar-mass black hole binaries: The need for deci-Hertz gravitational wave observatories. Astrophys. J. 2017;842(1):L2. doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/aa74ce. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Portegies Zwart SF, McMillan S. Black hole mergers in the universe. Astrophys. J. 2000;528:L17. doi: 10.1086/312422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Giersz M, Leigh N, Hypki A, Lützgendorf N, Askar A. MOCCA code for star cluster simulations - IV. A new scenario for intermediate mass black hole formation in globular clusters. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2015;454(3):3150. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stv2162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Arca Sedda, M., Askar, A., Giersz, M.: MOCCA-SURVEY Database I. Intermediate mass black holes in Milky Way globular clusters and their connection to supermassive black holes. arXiv:1905.00902 (2019)

- 80.Abbott R, et al. Properties and Astrophysical Implications of the 150 M⊙ Binary Black Hole Merger GW190521. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2020;900(1):L13. doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/aba493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Amaro-Seoane P, Gair JR, Freitag M, Coleman Miller M, Mandel I, Cutler CJ, Babak S. Astrophysics, detection and science applications of intermediate- and extreme mass-ratio inspirals. Class. Quant. Grav. 2007;24:R113. doi: 10.1088/0264-9381/24/17/R01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brown DA, Fang H, Gair JR, Li C, Lovelace G, Mandel I, Thorne KS. Prospects for detection of gravitational waves from intermediate-mass-ratio inspirals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;99:201102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.201102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rodriguez CL, Mandel I, Gair JR. Verifying the no-hair property of massive compact objects with intermediate-mass-ratio inspirals in advanced gravitational-wave detectors. Phys. Rev. 2012;D85:062002. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Haster CJ, Wang Z, Berry CPL, Stevenson S, Veitch J, Mandel I. Inference on gravitational waves from coalescences of stellar-mass compact objects and intermediate-mass black holes. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2016;457(4):4499. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stw233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen JH, Shen RF. Tidal disruption of a main-sequence star by an intermediate-mass black hole: A bright decade. Astrophys. J. 2018;867(1):20. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aadfda. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Eracleous M, Gezari S, Sesana A, Bogdanovic T, MacLeod M, Roth N, Dai L. An arena for multi-messenger astrophysics: Inspiral and tidal disruption of white dwarfs by massive black holes. Bull. Am. Astron. Soc. 2019;51(3):10. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ezquiaga JM, Holz DE. Jumping the gap: searching for LIGO’s biggest black holes. arXiv:http://arxiv.org/abs/2006.02211. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2020;909(2):L23. doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/abe638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Volonteri M, Natarajan P. Journey to the MBH − σ relation: the fate of low mass black holes in the Universe. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2009;400:1911. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15577.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McKernan B, Ford KES, Kocsis B, Lyra W, Winter LM. Intermediate-mass black holes in AGN discs II. Model predictions and observational constraints. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2014;441(1):900. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stu553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bartos I, Kocsis B, Haiman Z, Márka S. Rapid and bright stellar-mass binary black hole mergers in active galactic nuclei. Astrophys. J. 2017;835(2):165. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/835/2/165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stone NC, Metzger BD, Haiman Z. Assisted inspirals of stellar mass black holes embedded in AGN discs: solving the final au problem. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2017;464(1):946. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stw2260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McKernan B, et al. Constraining stellar-mass black hole mergers in AGN Disks detectable with LIGO. Astrophys. J. 2018;866(1):66. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aadae5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen X, Li S, Cao Z. Massaredshift degeneracy for the gravitational-wave sources in the vicinity of supermassive black holes. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2019;485(1):L141. doi: 10.1093/mnrasl/slz046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gondán L, Kocsis B, Raffai P, Frei Z. Eccentric black hole gravitational-wave capture sources in galactic nuclei: Distribution of binary parameters. Astrophys. J. 2018;860(1):5. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aabfee. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Secunda A, Bellovary J, Mac Low MM, Saavik Ford KE, McKernan B, Leigh N, Lyra W, Sándor Z. Orbital migration of interacting stellar mass black holes in disks around supermassive black holes. Astrophys. J. 2019;878(2):85. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ab20ca. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rasskazov A, Kocsis B. The rate of stellar mass black hole scattering in galactic nuclei. Astrophys. J. 2019;881:20. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ab2c74. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yang Y, Bartos I, Haiman Z, Kocsis B, Marka Z, Stone NC, Marka S. AGN disks harden the mass distribution of stellar-mass binary black hole mergers. Astrophys. J. 2019;876(2):122. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ab16e3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kosowsky A, Turner MS. Gravitational radiation from colliding vacuum bubbles: Envelope approximation to many bubble collisions. Phys. Rev. 1993;D47:4372. doi: 10.1103/physrevd.47.4372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kamionkowski M, Kosowsky A, Turner MS. Gravitational radiation from first order phase transitions. Phys. Rev. 1994;D49:2837. doi: 10.1103/physrevd.49.2837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gogoberidze G, Kahniashvili T, Kosowsky A. The spectrum of gravitational radiation from primordial turbulence. Phys. Rev. 2007;083002:D76. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.231301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Caprini C, Durrer R, Servant G. The stochastic gravitational wave background from turbulence and magnetic fields generated by a first-order phase transition. JCAP. 2009;0912:024. doi: 10.1088/1475-7516/2009/12/024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hindmarsh M, Huber SJ, Rummukainen K, Weir DJ. Gravitational waves from the sound of a first order phase transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014;112:041301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.041301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hindmarsh M, Huber SJ, Rummukainen K, Weir DJ. Numerical simulations of acoustically generated gravitational waves at a first order phase transition. Phys. Rev. 2015;d92(12):123009. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Randall L, Servant G. Gravitational waves from warped spacetime. JHEP. 2007;05:054. doi: 10.1088/1126-6708/2007/05/054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nardini G, Quiros M, Wulzer A. A confining strong first-order electroweak phase transition. JHEP. 2007;09:077. doi: 10.1088/1126-6708/2007/09/077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Konstandin T, Nardini G, Quiros M. Gravitational backreaction effects on the holographic phase transition. Phys. Rev. 2010;D82:083513. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Konstandin T, Servant G. Cosmological consequences of nearly conformal dynamics at the TeV scale. JCAP. 2011;1112:009. doi: 10.1088/1475-7516/2011/12/009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bruggisser S, Von Harling B, Matsedonskyi O, Servant G. Baryon asymmetry from a composite Higgs boson. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018;121(13):131801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.131801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Megías E, Nardini G, Quirós M. Cosmological phase transitions in warped space: Gravitational Waves and Collider Signatures. JHEP. 2018;09:095. doi: 10.1007/JHEP09(2018)095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Arkani-Hamed N, Han T, Mangano M, Wang LT. Physics opportunities of a 100 TeV protonaproton collider. Phys. Rept. 2016;652:1. doi: 10.1016/j.physrep.2016.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Graham PW, Kaplan DE, Mardon J, Rajendran S, Terrano WA. Dark matter direct detection with accelerometers. Phys. Rev. 2016;d93(7):075029. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vachaspati T, Vilenkin A. Gravitational radiation from cosmic strings. Phys. Rev. 1985;D31:3052. doi: 10.1103/physrevd.31.3052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Blanco-Pillado JJ, Olum KD, Shlaer B. The number of cosmic string loops. Phys. Rev. 2014;d89(2):023512. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Auclair P, et al. Probing the gravitational wave background from cosmic strings with LISA. JCAP. 2020;2004:034. doi: 10.1088/1475-7516/2020/04/034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sanidas SA, Battye RA, Stappers BW. Constraints on cosmic string tension imposed by the limit on the stochastic gravitational wave background from the European Pulsar Timing Array. Phys. Rev. 2012;D85:122003. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Blanco-Pillado JJ, Olum KD, Siemens X. New limits on cosmic strings from gravitational wave observation. Phys. Lett. 2018;B778:392. doi: 10.1016/j.physletb.2018.01.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bender PL, Begelman MC, Gair JR. Possible LISA follow-on mission scientific objectives. Class. Quant. Grav. 2013;30:165017. doi: 10.1088/0264-9381/30/16/165017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mueller G, Baker J, et al. Space based gravitational wave astronomy beyond LISA. Bull. Am. Astron. Soc. 2019;51(7):243. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hu WR, Wu YL. The Taiji Program in Space for gravitational wave physics and the nature of gravity. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2017;4(5):685. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwx116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ruan WH, Guo ZK, Cai RG, Zhang YZ. Taiji Program: Gravitational-wave sources. Int. J. Mod. Phys. 2020;a35(17):2050075. doi: 10.1142/S0217751X2050075X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kuns KA, Yu H, Chen Y, Adhikari RX. Astrophysics and cosmology with a decihertz gravitational-wave detector: TianGO. Phys. Rev. 2020;d102(4):043001. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Luo J, et al. TianQin: A space-borne gravitational wave detector. Class. Quant. Grav. 2016;33(3):035010. doi: 10.1088/0264-9381/33/3/035010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sato S, et al. The status of DECIGO. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017;840(1):012010. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/840/1/012010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kawamura, S., et al.: Current status of space gravitational wave antenna DECIGO and B-DECIGO. arXiv:2006.13545 (2020)

- 125.Crowder J, Cornish NJ. Beyond LISA: Exploring future gravitational wave missions. Phys. Rev. 2005;D72:083005. [Google Scholar]

- 126.McWilliams, S.T: Geostationary antenna for disturbance-free laser interferometry (GADFLI). arXiv:1111.3708 (2011)

- 127.Tinto, M., de Araujo, J.C.N., Aguiar, O.D., da Silva Alves, M.E.: A geostationary gravitational wave interferometer (GEOGRAWI). arXiv:1111.2576 (2011)

- 128.Tinto M, DeBra D, Buchman S, Tilley S. gLISA: geosynchronous Laser Interferometer Space Antenna concepts with off-the-shelf satellites. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2015;86:014501. doi: 10.1063/1.4904862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lacour S, et al. SAGE: finding IMBH in the black hole desert. Class. Quant. Grav. 2019;36(19):195005. doi: 10.1088/1361-6382/ab3583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Tino GM, et al. SAGE: A proposal for a space atomic gravity explorer. Eur. Phys. J. 2019;D73(11):228. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kolkowitz S, Pikovski I, Langellier N, Lukin MD, Walsworth RL, Ye J. Gravitational wave detection with optical lattice atomic clocks. Phys. Rev. 2016;d94(12):124043. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Su J, Wang Q, Wang Q, Jetzer P. Low-frequency gravitational wave detection via double optical clocks in space. Class. Quant. Grav. 2018;35(8):085010. doi: 10.1088/1361-6382/aab2eb. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Graham, P.W., Hogan, J.M., Kasevich, M.A., Rajendran, S., Romani, R.W.: Mid-band gravitational wave detection with precision atomic sensors. arXiv:1711.02225 (2017) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 134.El-Neaj YA, et al. AEDGE: atomic experiment for dark matter and gravity exploration in space. EPJ Quant. Technol. 2020;7:6. doi: 10.1140/epjqt/s40507-020-0080-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Arca Sedda, M., et al.: The Missing Link in Gravitational-Wave Astronomy: Discoveries waiting in the decihertz range. arXiv:1908.11375v1(2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 136.Sesana, A, et al.: Unveiling the gravitational universe at μ-Hz Frequencies. arXiv:1908.11391 (2019)

- 137.Baibhav, V, et al.: Probing the nature of black holes: Deep in the mHz gravitational-wave sky. arXiv:1908.11390 (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 138.Baker, J, et al.: High angular resolution gravitational wave astronomy. arXiv:1908.11410 (2019)