Abstract

Dry tubers of Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Breit are used in traditional Chinese medicine. Commonly known as “banxia” in China, the tubers contain valuable compounds, including alkaloids and polysaccharides that are widely used in pharmaceuticals. The quantity and quality of these important compounds are affected by whether P. ternata is grown as a sole crop or as an intercrop, and P. ternata cultivation has become challenging in recent years. By intercropping P. ternata, its maximum yield, as well as large numbers of chemical components, can be realized. Here, a large data set derived from next-generation sequencing was used to compare changes in the bacterial communities in rhizosphere soils of P. ternata and maize grown as sole crops and as intercrops. The overall microbial population in the rhizosphere of intercropped P. ternata was significantly larger than that of sole-cropped P. ternata, whereas the numbers of distinct microbial genera, ranging from 552 to 559 among treatments, were not significantly different between the two rhizospheres. The relative abundances of the genera differed. Specifically, the numbers of Acidobacteria and Anaerolineaceae species were significantly greater, and those of Bacillus were significantly lower, in the intercropped P. ternata rhizosphere than in the sole-cropped rhizosphere.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-021-03011-3.

Keywords: Pinellia ternata, Intercropping, Rhizosphere microorganisms, Microbial diversity, Alpha diversity, Beta diversity

Introduction

Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Breit, which belongs to the family Arceae, is a perennial herb with medicinal uses that is found in East Asia and commonly cultivated in China (Zhang et al. 2013; Moon et al. 2016). The main medicinal part is the dried tuber, “banxia” in Chinese, which has been widely used over centuries in traditional Chinese medicine (Iwasa et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2015). Major constituents of P. ternata are organic acids, polysaccharides, and alkaloids (Gombodorj et al. 2017; Xu et al. 2018), with the latter, which have anticancer properties, being considered the principle biologically active ingredients (Gombodorj et al. 2017). The herb is used as a sedative with analgesic and antiemetic properties (Zhang et al. 2016). In addition to its antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, immune-boosting, antibacterial, anti-obesity (Ji et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2020), and bacteriostatic (Ji et al. 2014) properties, it has been used for treating convulsive disorders, vomiting, and coughing for decades. Worthwhile uses of P. ternata in traditional Chinese medicine are as an antitussive and anxiolytic (Gombodorj et al. 2017; Xu et al. 2018; Lin et al. 2019).

Pinellia ternata is susceptible to intense light and high temperatures during its growth period. The plant withers quickly under high temperatures and strong sunlight, and it develops a “sprout tumble” (Juneidi et al. 2020; Ma et al. 2020). Although P. ternata prefers warm, or hot, and humid weather, intense sunshine, high temperatures, and waterlogging are not conducive to growth. The demand for this herb continues to increase but cannot be met because it is not cultivated on a large scale. “Sprout tumbles” occur in hot weather and immediately restrict the formation of tubers, further increasing the gap between supply and demand (Xue et al. 2019). Xue et al. (2019) showed that reducing “sprout tumbles” was crucial for increasing tuber yield. The rate of “sprout tumble” formation can be decreased, and the date of “sprout tumble” onset advanced, by maintaining low temperatures or by providing shade during the plant’s regenerative developmental cycle (Zhang et al. 2021).

Monocropping, or sole cropping, poses a challenge to the cultivation of traditional medicinal plants. The production of P. ternata decreases by 60–80% within 2 to 4 years of monocropping. Xihe County in China’s Gansu Province is well known for the production of this herb. However, in that region, P. ternata production declined from about 1665 ha in 2000 to approximately 535 ha in 2015. Recently, monocropping has become a particularly severe constraint to the cultivation of P. ternata (He et al. 2019), with several biotic and abiotic factors acting as barriers. The abiotic factors lower the quality of the soil and hamper efficient field management, whereas biotic factors lead to autotoxicity, pathogen infection, and changes in the microbial community composition of the rhizosphere (Vargas Gil et al. 2009), with the latter being the main barrier to the monoculturing of other crops as well (González-Chávez et al. 2010; Bernard et al. 2012; Larkin et al. 2012). Protecting crops from intense sunlight by building shelters is expensive in terms of human and material resources, and it also hampers cultural operations. However, higher yields of P. ternata can be obtained by intercropping it with other crops, such as maize, soybean, and wheat. These crops, owing to their vigorous growth, shelter P. ternata from direct sunlight. The allelochemicals produced by P. ternata are preserved mainly in the underground tubers, which influence the photosynthetic efficiency and viability of neighbouring crops through their antioxidative systems. Maize has been proven to be particularly suitable as an intercrop or as a rotational crop with P. ternata.

The rhizosphere, a zone of soil affected by root secretions, may harbour as many as 1011 units of microorganisms for every gram of roots (Hakim et al. 2021), and plants are closely connected to the microbes present in the soil. These soil microbes represent the world’s largest source of biological diversity known to date (Gams 2007; Ho et al. 2017; Jacoby et al. 2017). Beneficial rhizosphere microorganisms can promote plant growth through organic mineralization, biological nitrogen fixation (Van Der Heijden et al. 2008; Luo et al. 2016), host-immunity modulation (Dang et al. 2020), and pathogen suppression, thereby helping plants to distinguish between beneficial and harmful entities (Zamioudis and Pieterse 2012). Bacterial communities are the largest complex communities of soil microbes, accounting for as many as 104 communities for every gram of soil (Weinert et al. 2011; Xu et al. 2019). Intercropping increases the number of soil microorganisms in the rhizosphere, as well as their diversity level (Dariush et al. 2006; Dang et al. 2020).

Our limited capacity to analyse soil environments in real time is part of the challenge in examining the structures of soil microbial communities. Research using PCR extractions of genetic materials (Rastogi and Sani 2011) offers fresh insights into the immense diversity of bacterial strains in the soil ecosystem. However, few studies have explored the variety and composition of bacterial communities in the rhizosphere of P. ternata or compared their characteristics between sole-cropped and intercropped P. ternata. Consequently, we analysed the diversity, composition, and structures of bacterial communities from the rhizospheres of P. ternata and maize grown separately as monocrops and together as intercrops.

Materials and methods

The field trial design

The experiment was conducted in 2018 and 2019 in China at Hubei Jingheyuan Ecological Agriculture Co., Ltd., Shayang County, Jingmen City, Hubei Province (30° 38′ 19.55″ N, 112° 34′ 15.82″ E). The average annual temperature at the site was 15.6–16.3 °C, the duration of sunshine was 1997–2100 h a year, and the average annual precipitation was 804–1067 mm. The soil at the experimental site was sandy but highly fertile. Tubers of P. ternata, collected from Jingmen City and 6–8 mm in diameter, were planted on March 20 in 2018 and 2019. The crop was sown for two consecutive years, with two harvests a year, on July 1 and in mid-November. Maize seeds (Zea mays L., ‘Huimin 302’) were purchased from the Hubei Huimin Agricultural Technology Co., Ltd., sown on April 10 and harvested on July 20 in both years.

For the experiment, a two-factorial randomized block design was adopted. Factor 1 was designed as the maize single-line planting on the same side. Factor 2 was the distance between the rows of maize and P. ternata, which was maintained at 35, 50, or 65 cm. Two controls were maintained, maize grown as a sole crop and P. ternata grown as a sole crop. The experiment had 5 treatments, repeated over 15 blocks, each with 3 plots. Each plot was 1.1 m wide and 7.5 m long, containing a 0.4-m-wide trench. The seed rate for P. ternata was 3,750 kg hm−2 of tubers. During monocropping, whether maize or P. ternata, the plant-to-plant and row-to-row distances were 35 cm and 50 cm, respectively.

Sampling of rhizosphere soil

The plants were gently uprooted and excess soil was removed by shaking the roots. The soil clinging to the roots, forming a layer of approximately 1 mm, was retained. It was then removed using a sterilized brush, and the roots were stored in dry ice. The intact root system was placed in a 50-mL test tube filled with sterilized phosphate-buffered saline solution, and the root surface was removed using sterilized forceps. The washed soil along with the phosphate-buffered saline solution was poured into a series of 50-mL sterilized test tubes and centrifuged. The supernatant was discarded, whereas the pellet, the rhizosphere soil, was rapidly frozen using liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C for analysing the microbial diversity.

DNA extraction and MiSeq sequencing

A PowerSoil kit (MO BIO Lab., Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used for extracting genomic DNA from the soil samples (each weighing 0.5 g, dry weight). The extracted DNA was stored at − 80 °C, and its concentration was measured using a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop 2000C, Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). The V4–V3 region of the 16S rRNA bacterial gene was amplified with the primers 338F (5ʹ-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3ʹ) and 806R (5ʹ-GGACTACHVGGTWTCTAAT-3ʹ) using the following PCR amplification protocol: 3 min of denaturation at 95 °C, 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C for annealing, and 45 s at 72 °C for elongation, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The following mixture (final volume 20 μL) was used for the PCR reactions: 4 μL of 5 FastPfu buffer, 2 μL of 2.5-mM dNTPs, 0.8 μL of each primer (5 μM), 0.4 μL of FastPfu polymerase, 0.2 μL of bovine serum albumin, and 10 ng of the DNA template.

Sequence processing and analysis

Purified amplicons in equimolar and paired-end sequences (2 × 300) were obtained on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using the standard protocols stipulated by the company. Illumina sequencing was used to generate raw gene-sequence data, and the data were modified using Trimmonmatic and FLASH. The sequences were grouped into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) after 97% pair recognition by QIIME using Usearch ver. 7.1 (http:/qiime.org/). The Ribosomal Database Project classifier (Release 11.1 http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/) was used for the taxonomic categorization of the representative sequences of bacteria against the Greengenes 16S rRNA (Release 13.5; greengenes.secondgenome.com/) and Silva (Release 115; arb-silva.de) databases.

Statistical analyses

The treatments were compared using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s test of honestly significant differences. All the analyses of alpha diversity relied on the OTU clusters with a 3% dissimilarity as the cut-off point. Five indexes, phylogenetic diversity (Pd), Simpson, amount of observed species (Sobs), Chao, and Shannon, of the richness and diversity of the bacterial community associated with each treatment were computed. We compared the levels of diversity of bacterial OTUs across the soil samples from P. ternata to the rarefaction curves provided by Mothur and further evaluated the similarity between the community memberships using a principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) with weighted and unweighted distance metrics of UniFrac (based on the phylogenetic structure). Lastly, Venn diagrams were constructed to examine the similarity and dissimilarity levels among species in the samples.

Results

Sequencing of DNA

The sequenced data (OTUs, sequence numbers, base numbers, and mean lengths) showed the overall structure of our study (Table 1). We observed that in all the trials, the OTUs were nearly equal. The maximum number of sequences (103,527 sequences) was retrieved from P. ternata planted 65 cm away from maize as an intercrop, whereas the sequence numbers in the other treatment samples did not differ significantly. The maximum number of bases was also recorded for sequences from intercropped P. ternata, whereas the base numbers in the other treatment samples were similar. The mean lengths of the sequences were equal in all the cropping system samples.

Table 1.

Sequenced data for all the cropping systems

| Sample | OTUs | Seq No. | Base No. | Mean length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ac | 20427 | 34572.33 | 15164406.67 | 438.63 |

| Aa | 24491 | 40401 | 17707564.33 | 438.24 |

| Ab | 22500 | 103527 | 45412416 | 438.64 |

| CK | 21452.67 | 35806.33 | 15701947.67 | 438.50 |

| YM | 22001.33 | 32372.67 | 14240639.33 | 439.91 |

Aa, Ab, and Ac indicate P. ternata intercropped at 35, 50, and 65 cm away from maize, respectively, CK represents P. ternata monocropping and YM represents maize monocropping OTU, operational taxonomic unit

Alpha diversity

The treatments showed no significant differences in Pd (Table 2), whereas the Simpson index of the monocropped maize sample was substantially higher than that of the other treatment samples.

Table 2.

Alpha diversity index of rhizosphere soil microorganisms under P. ternata–maize intercropping conditions

| Treatments | Pd | Simpson | Sobs | Chao | Shannon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aa | 153.6 ± 9.8a | 0.0028 ± 0.0002b | 2171.0 ± 16.3a | 2516.3 ± 12b | 6.72 ± 0.02a |

| Ab | 148.1 ± 8.1a | 0.0027 ± 0.0005b | 2185.0 ± 21.5a | 2594.8 ± 15.3a | 6.75 ± 0.05a |

| Ac | 147.2 ± 7.2a | 0.0024 ± 0.0003b | 2204.3 ± 15.0a | 2587.9 ± 11.2a | 6.80 ± 0.01a |

| CK | 142.7 ± 8.3a | 0.0037 ± 0.0001b | 2136.6 ± 15.7a | 2497.2 ± 7.3b | 6.62 ± 0.07a |

| YM | 139.6 ± 9.2a | 0.0100 ± 0.0004a | 1880.0 ± 24.4b | 2268.7 ± 23.0c | 6.13 ± 0.17b |

The variance in alpha diversity across samples is shown

Aa, Ab, and Ac indicate P. ternata intercropped at 35, 50, and 65 cm away from maize, respectively, CK represents P. ternata monocropping and YM represents maize monocropping

ashows significant

ashows the non significant value (p < 5%)

Pd phylogenetic diversity; Sobs amount of observed species

The Chao index measures species richness, and the higher its value, the greater the community richness (t). The Chao index of monocropped maize, at 2,268.7, was significantly lower than those of other treatment samples, and the Chao index of monocropped P. ternata was significantly lower than that of intercropped P. ternata, indicating that intercropping increases the richness of rhizosphere soil microorganisms. Similarly, Sobs and Shannon indexes of monocropped maize were significantly lower than those of the other treatment samples, indicating that there was no significant difference in the species richness of the rhizosphere soils between monocropped and intercropped P. ternata. Thus, using P. ternata as an intercrop did not change the microorganism diversity level in the rhizosphere soil.

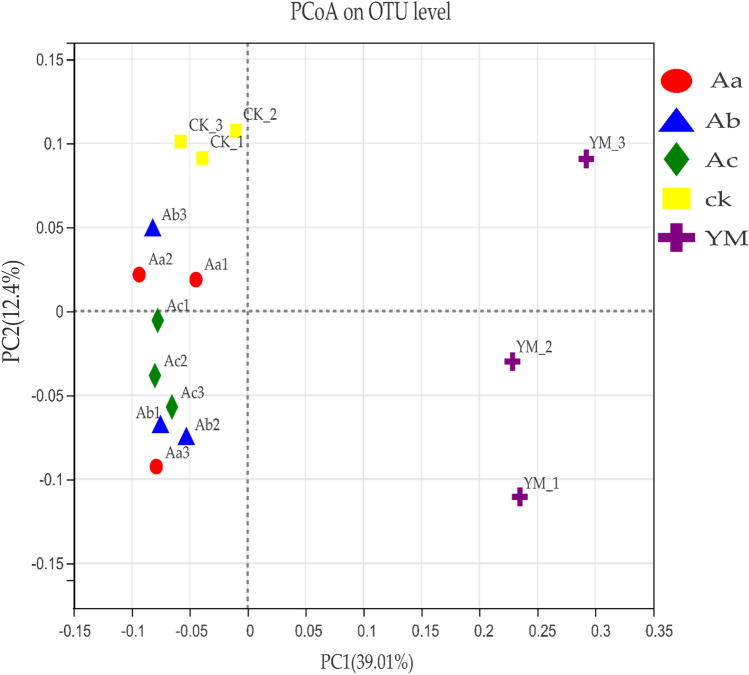

Beta diversity

As shown by the PCoA based on UniFrac distances, unweighted and weighted, microbial communities in the rhizosphere of P. ternata differed, depending on whether P. ternata was monocropped or intercropped. Microbial communities in the first principal coordinate component (PC1) (39.01% contribution) and second principal coordinate component (PC2) (12.4% contribution) represent the two axes in Fig. 1. The bacterial communities in intercropped P. ternata, irrespective of its distance from maize, 35, 50, or 65 cm, and those in monocropped P. ternata were more similar to each other than to the bacterial communities from monocropped maize, and they clustered along different axes.

Fig. 1.

Principal coordinate analysis: YM, maize as a sole crop; ML, P. ternata as a sole crop (control); Aa, Ab, and Ac, P. ternata planted 35, 50, and 65 cm away from maize, respectively

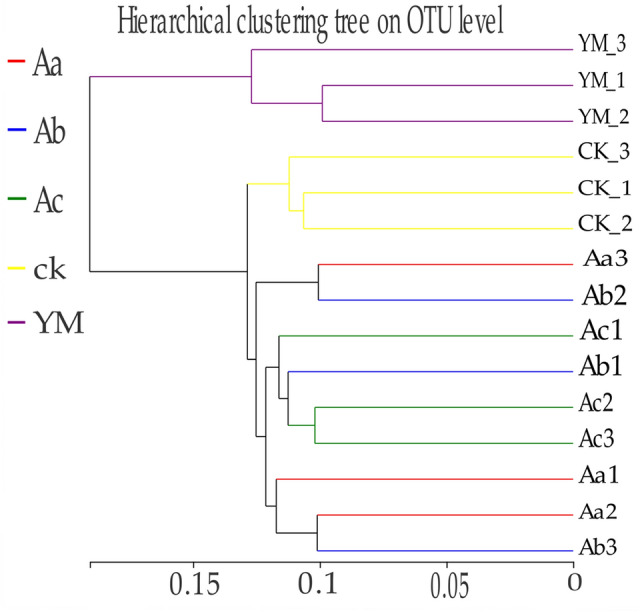

The beta diversity, using the Bray–Curtis distance matrix, revealed that bacterial communities in soil samples collected from the same fields were more similar to each other than to those in the corresponding soil samples from different fields. For example, bacterial communities from the rhizosphere of monocropped maize clustered differently from those of monocropped and intercropped P. ternata planted at varying distances, 35, 50, or 65 cm, from maize (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Bray–Curtis dissimilarity hierarchical cluster tree of the soil bacterial community: YM, maize as a sole crop; ML, P. ternata as a sole crop (control); Aa, Ab, and Ac, P. ternata planted 35, 50, and 65 cm away from maize, respectively

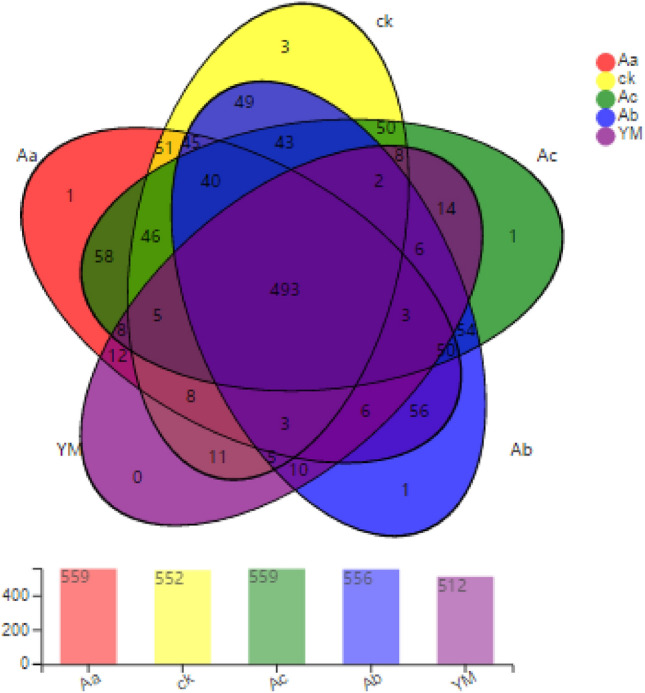

Bacterial community compositions

A rarefaction curve is used to confirm that the amount of sample sequencing data is sufficient. A flat curve indicates that the amount of data is adequate and that more data will add only a limited number of new species, whereas a steeper curve indicates that adding more sequences to the data will reveal many new species. The rarefaction curve of the sequencing data from the present experiment is shown in the supplementary data (Figure S1). We used a Venn diagram to determine the number of unique species and their relative proportions in the samples. A Venn diagram of the bacterial communities, at the genus level, in the rhizospheres of treatments is shown in Fig. 3. The numbers of genera varied with the treatment, as follows: 559 genera were represented in the samples from P. ternata planted 35 cm or 65 cm away from maize; whereas there were 556 genera in samples from P. ternata planted 50 cm away from maize. As sole crops, there were 552 and 521 from P. ternata and maize samples, respectively. Across these treatments, there were 493 common genera (found in every treatment). Each of the treatments in which P. ternata was planted a different distance from maize showed one unique genus. Additionally, P. ternata as a monocrop yielded three unique genera; whereas maize as a monocrop yielded no unique genera.

Fig. 3.

Venn diagram of the composition of bacterial communities in rhizospheres of P. ternata intercropped with maize. Different colours represent different treatments; the numbers refer to the number of species common to multiple treatments in overlapping and non-overlapping sections

A Circos sample–species relationship diagram shows the correspondence between samples and species. The graph represents not only the proportions of dominant species in a sample but also the distribution ratio of each dominant species across samples. The composition of the bacterial community (at the genus level) in the rhizosphere of P. ternata intercropped with maize is shown in Figure S2. The community was dominated by 26 major genera: Acidobacteria, Bacillus, Fictibacillus, Nitrospira, Sphingomonas, Anaerolineaceae, KD4-96, Knoellia, Nocardioides, Pseudarthrobacter, H16, Nitrosomonadaceae, JG30-KF-Cm45, Actinobacteria, Rhodobiaceae, Gaiella, Microvirga, Gaiellales, Streptomyces, Gemmatimonadaceae, Xanthomonadales, Acidimicrobiales, Rhodospirillaceae, Roseiflexus, Rhizobium, and Pseudomonas. Among them, the relative abundances of three genera varied at treatment, as follows (the proportions listed in descending order). Acidobacteria: 25%, 24%, and 23% in P. ternata planted 65, 50, and 35 cm away from maize, respectively, and 14% in both crops as sole crops; Bacillus: 11%,12%, and 11% in P. ternata planted 65, 50, and 35 cm away from maize, respectively, and 43% and 22% in maize and P. ternata as sole crops, respectively; Fictibacillus: 7.4%, 6.5%, and 7.1% in P. ternata planted 65, 50, and 35 cm away from maize, respectively, and 68% and 11% in maize and P. ternata as sole crops, respectively. The species composition of the rhizosphere of P. ternata as a sole crop was the same as that of P. ternata as an intercrop, but the relative abundances of the species differed between the two treatments. The composition of the rhizosphere of maize was also different from that of the rhizosphere of P. ternata.

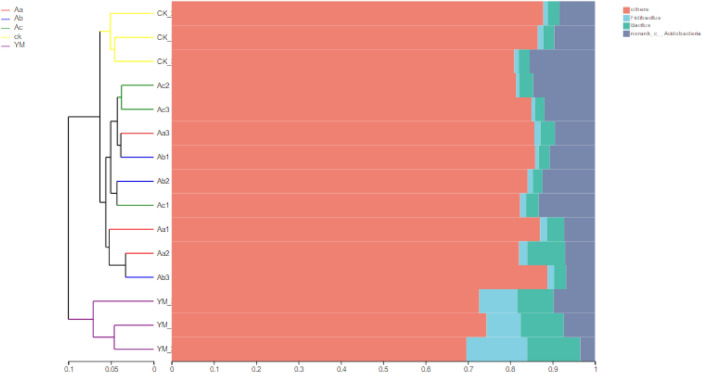

Sample comparisons

A sample hierarchical cluster on the basis of beta diversity, at the genus level, of the rhizosphere bacteria is shown in Fig. 4. Two genera, Fictibacillus and Bacillus, dominated every treatment, as did no-rank Acidobacteria. The bacterial communities of the maize rhizosphere differed from those of the P. ternata rhizosphere (whether as a sole crop or as an intercrop), which showed that the bacterial composition of the rhizosphere was influenced by the crop.

Fig. 4.

Hierarchical clustering tree at the genus level. The distances between branches represent the differences among treatments, and different colours represent different taxonomic categories. In the stacked column chart, the composition of the dominant species in each sample is shown on the right

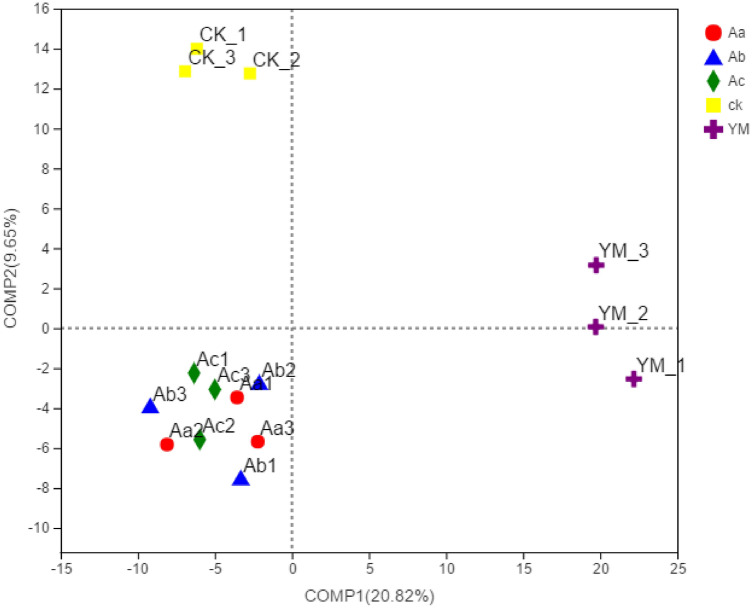

In Fig. 5, a PLS-DA analysis of the rhizosphere bacteria under each treatment at the genus level is shown. Here, the differences in the compositions of the bacterial communities were also evident, which again indicated the influence of the crop.

Fig. 5.

Partial least squares discriminant analysis. In different environments or circumstances, different coloured dots or shapes represent different treatments. Measurements along the X- and Y-axes are relative distances and have no functional values. The presumed factors controlling changes in the microbial composition of the two sample groups areComp1 and Comp2, respectively

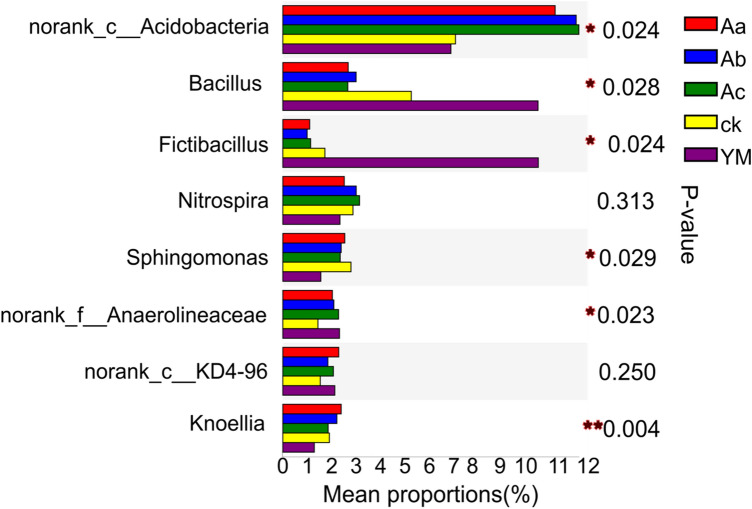

Analysis of differences in bacterial species

The relative abundance of no-rank Acidobacteria in intercropped P. ternata samples was significantly greater than in sole-cropped P. ternata and maize samples (Fig. 6). The relative abundances of Bacillus in sole-cropped P. ternata and maize samples were significantly greater than in intercropped P. ternata samples. However, Fictibacillus, was more abundant in sole-cropped maize samples than in any other treatment, and sole-cropped maize samples also had lower abundances of Sphingomonas and Knoellia than any of the other treatments. As a monocrop, P. ternata recorded a significantly lower relative abundance of no-rank Anaerolineaceae than any other treatment.

Fig. 6.

Variations in microbial communities of rhizospheres of P. ternata intercropped with maize. At a given taxonomic level, the Y-axis represents the species, the X-axis represents the average relative abundance of species in different treatments, and columns of different colours represent different treatments. *, **, and ***: differences significant at the 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 levels, respectively

Discussion

Pinellia ternata, an important medicinal herb distributed over most of China, cannot be cultivated continuously in north-western China, especially in Gansu Province; whereas, in southern China, the plant has been cultivated continually for more than 10 years. Wild P. ternata grows as a weed of dryland crops, such as soybean, maize, and cotton. Reports have indicated that diseases are more severe when a crop is grown continually than when it is rotated with other crops, and the soil microbial community is believed to contribute greatly to countering plant diseases. In the present study, although the P. ternata yield was greater when it was intercropped with maize, the species composition of its rhizosphere remained the same whether it was grown as a sole crop or as an intercrop. However, the bacterial species were more abundant in P. ternata’s rhizosphere than in that of maize. The difference was traced to carbon sources. Decomposing plants release sugars and amino acids into the rhizosphere, which act as carbon sources for soil microorganisms. However, monocropping relies more on chemical fertilizers and, therefore, releases smaller amounts of carbon sources than intercropping. As a result, the microbial diversity and activity levels may be lower under monocrop conditions (Welbaum et al. 2004). The growth rates of the microorganisms at each point in the soil were assumed to be controlled by the soluble organic substrate concentrations. The relative composition of rhizosphere bacteria also differed, as reported in another study (Zi et al. 2020), in which Acidobacteria was the more abundant genus under intercropping conditions, with a relative abundance of 21.61%. This finding was consistent with that of the present study, in which the relative abundance of no-rank Acidobacteria was significantly higher under intercropping conditions. Members of Acidobacteria degrade cellulose and other polysaccharides and are, therefore, important to the ecosystem’s carbon cycle (Eichorst et al. 2011). Growing the same crop year after year lowers the soil pH (Lauber et al. 2009), which is probably less conducive to microbial activity; therefore, the carbon cycle in the P. ternata–maize intercropping system may be more efficient. Bacillus is a facultative anaerobic autogenous nitrogen-fixing bacterium (McSpadden Gardener 2004), and its relative abundance under sole-cropped P. ternata conditions was greater than under intercropped P. ternata conditions, which are, therefore, more conducive to nitrogen fixation. The added nitrogen may be exploited by Anaerobacteria which, under anaerobic conditions, degrade carbohydrates and participate simultaneously in C, N, Fe, and S cycles, thereby interacting with nitrogen-fixing bacteria to make the soil more fertile (Zhang et al. 2019). Several soil factors are associated with unique bacterial communities, and the ammonium nitrogen (NH4-N) content of the soil may be the key factor affecting the diversity and distribution of bacterial communities (Zi et al. 2020). Thus, the P. ternata–maize intercropping system was more efficient in recycling nutrients than P. ternata monocropping.

Understanding the structure and diversity of bacterial communities in the rhizosphere provides novel insights into microorganisms that are potentially hostile to plant pathogens (Berendsen et al. 2012). The present study observed a significant decline in bacterial richness (Chao) under sole-cropped P. ternata conditions, but there were no significant effects on diversity (Pd) (Table 1). This result is consistent with those of several earlier studies. For example, in black pepper, the bacterial diversity decreases significantly after 55 years of monocropping (Xiong et al. 2015), and similar results have been observed for cucumber (Chen et al. 2012) and potato (Liu et al. 2014). The richness and diversity of soil bacteria play essential roles in soil quality and health, as well as in the sustainability of soil ecosystems (Kennedy and Smith 1995), whereas continued monocropping is detrimental to both richness and diversity. A decrease in the diversity level of soil microbes aids the development of soil borne plant diseases (Mazzola 2004). Overall, any reduction in the richness and diversity levels of a soil microbial community as a result of continual cropping may impair plant performance and make plants vulnerable to diseases and pests, as shown in Camellia sinensis. Moreover, the UniFrac-weighted PCoA (Fig. 1) showed marked variations in the structures of bacterial communities across the treatments, and this was consistent with the findings of Xiong et al. (2015), in that the long-term continual cropping of black pepper results in noticeable variations in the structure of the bacterial community. Li et al. (2014), using a 454-pyrosequencing analysis, also noted significant differences in the compositions and structures of soil microbial communities of three peanut fields, each having a different monoculture history, and the number of unique bacterial OTUs declined over time during vanilla monoculturing (Zhao et al. 2014).

To conclude, intercropping P. ternata with maize affected the relative abundances of the different genera in the microbial community of the rhizosphere more than the composition, and the former was greatly increased as a result of intercropping: no-rank Acidobacteria and no-rank Anaerolineaceae were significantly more abundant. Therefore, we believe that P. ternata–maize intercropping will use soil nutrients more efficiently. More generally, the diversity, function, and application of rhizosphere microorganisms to medicinal plants deserves greater attention, and associated research will provide valuable insights into the roles of microbes in promoting plant growth and increasing the accumulation of active compounds in plant tissues.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

HAN, ZZ, and SS designed the study; HAN wrote the MS; HAN, AHK, UA, MH, MA, and MMA helped create diagrams; HAN, MZ, UA, HB, AHK, MH, MMA, MH, and SS revised the MS; SS supervised All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project of China [No.2017YFC1700700].

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Hamza Armghan Noushahi and Zhenxing Zhu have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Hamza Armghan Noushahi, Email: hamzanaushahi143@gmail.com.

Zhenxing Zhu, Email: 842871151@qq.com.

Aamir Hamid Khan, Email: Passaban786@webmail.hzau.edu.cn.

Umair Ahmed, Email: umairhzau@outlook.com.

Muhammad Haroon, Email: muhammadharoon974@gmail.com.

Muhammad Asad, Email: ch.muhammadasad007@gmail.com.

Mubashar Hussain, Email: mubasharhussain947@gmail.com.

He Beibei, Email: 1156849213@qq.com.

Maimoona Zafar, Email: maimoonazaffar@gmail.com.

Mohammad Murtaza Alami, Email: murtazaalami@webmail.hzau.edu.cn.

Shaohua Shu, Email: shushaohua@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

References

- Berendsen RL, Pieterse CMJ, Bakker PAHM. The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard E, Larkin RP, Tavantzis S, et al. Compost, rapeseed rotation, and biocontrol agents significantly impact soil microbial communities in organic and conventional potato production systems. Appl Soil Ecol. 2012;52:29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L-H, Huang X-Q, Zhang F-G, et al. Application of Trichoderma harzianum SQR-T037 bio-organic fertiliser significantly controls Fusarium wilt and affects the microbial communities of continuously cropped soil of cucumber. J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92:2465–2470. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang K, Gong X, Zhao G, et al. Intercropping alters the soil microbial diversity and community to facilitate nitrogen assimilation: a potential mechanism for increasing proso millet grain yield. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:2975. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.601054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dariush M, Ahad M, Meysam O. Assessing the land equivalent ratio (LER) of two corn [Zea mays L.] varieties intercropping at various nitrogen levels in Karaj. Iran J Cen Europ Agri. 2006;7:359–364. [Google Scholar]

- del González-Chávez MCA, Aitkenhead-Peterson JA, Gentry TJ, et al. Soil microbial community, C, N, and P responses to long-term tillage and crop rotation. Soil Tillage Res. 2010;106:285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Eichorst SA, Kuske CR, Schmidt TM. Influence of plant polymers on the distribution and cultivation of bacteria in the phylum acidobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:586–596. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01080-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gams W. Biodiversity of soil-inhabiting fungi. Biodivers Conserv. 2007;16:69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gombodorj S, Yang MH, Shang ZC, et al. New phenalenone derivatives from Pinellia ternata tubers derived Aspergillus sp. Fitoterapia. 2017;120:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakim S, Naqqash T, Nawaz MS, et al. rhizosphere engineering with plant growth-promoting microorganisms for agriculture and ecological sustainability. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2021;5:16. [Google Scholar]

- He Z, Mao R, Dong JE, et al. Remediation of deterioration in microbial structure in continuous Pinellia ternata cropping soil by crop rotation. Can J Microbiol. 2019;65:282–295. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2018-0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y-N, Mathew DC, Huang C-C. Plant Ecology-Traditional Approaches to Recent Trends. InTech; 2017. Plant-microbe ecology: interactions of plants and symbiotic microbial communities; pp. 93–119. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasa M, Iwasaki T, Ono T, Miyazawa M. Chemical composition and major odor-active compounds of essential oil from PINELLIA TUBER (dried rhizome of Pinellia ternata) as crude drug. J Oleo Sci. 2014;63:127–135. doi: 10.5650/jos.ess13092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby R, Peukert M, Succurro A, et al. The role of soil microorganisms in plant mineral nutrition—current knowledge and future directions. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1617. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X, Huang B, Wang G, Zhang C. The ethnobotanical, phytochemical and pharmacological profile of the genus Pinellia. Fitoterapia. 2014;93:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juneidi S, Gao Z, Yin H, et al. Breaking the summer dormancy of Pinellia ternata by introducing a heat tolerance receptor-like kinase ERECTA gene. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:780. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy AC, Smith KL. Soil microbial diversity and the sustainability of agricultural soils. Plant Soil. 1995;170:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y-G, Komakech R, Choi JE, et al. Mass production of Pinellia ternata multiple egg-shaped micro-tubers (MESMT) through optimized growth conditions for use in ethnomedicine. Plant Cell, Tissue Organ Cult. 2020;140:173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Larkin RP, Honeycutt CW, Olanya OM, et al. Sustainable Potato Production: Global Case Studies. Dordrecht: Springer; 2012. Impacts of crop rotation and irrigation on soilborne diseases and soil microbial communities; pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lauber CL, Hamady M, Knight R, Fierer N. Pyrosequencing-Based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:5111–5120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00335-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Ding C, Zhang T, Wang X. Fungal pathogen accumulation at the expense of plant-beneficial fungi as a consequence of consecutive peanut monoculturing. Soil Biol Biochem. 2014;72:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Nie B, Yao G, et al. Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) makino preparation promotes sleep by increasing REM sleep. Nat Prod Res. 2019;33:3326–3329. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2018.1474466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zhang J, Gu T, et al. Microbial community diversities and taxa abundances in soils along a seven-year gradient of potato monoculture using high throughput pyrosequencing approach. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S, Yu L, Liu Y, et al. Effects of reduced nitrogen input on productivity and N2O emissions in a sugarcane/soybean intercropping system. Eur J Agron. 2016;81:78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ma G, Zhang M, Xu J, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of short-term heat stress response in Pinellia ternata provided novel insights into the improved thermotolerance by spermidine and melatonin. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;202:110877. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzola M. Assessment and management of soil microbial community structure for disease suppression. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2004;42:35–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.42.040803.140408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSpadden Gardener BB. Ecology of Bacillus and Paenibacillus spp. in agricultural systems. Phytopathology. 2004;94:1252–1258. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.11.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon BC, Kim WJ, Ji Y, et al. Molecular identification of the traditional herbal medicines, Arisaematis Rhizoma and Pinelliae Tuber, and common adulterants via universal DNA barcode sequences. Genet Mol Res. 2016;15:1–14. doi: 10.4238/gmr.15017064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi G, Sani RK. Microbes and Microbial Technology. New York: Springer; 2011. Molecular techniques to assess microbial community structure, function, and dynamics in the environment; pp. 29–57. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Heijden MGA, Bardgett RD, Van Straalen NM. The unseen majority: soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol Lett. 2008;11:296–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Gil S, Meriles J, Conforto C, et al. Field assessment of soil biological and chemical quality in response to crop management practices. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;25:439–448. [Google Scholar]

- Weinert N, Piceno Y, Ding GC, et al. PhyloChip hybridization uncovered an enormous bacterial diversity in the rhizosphere of different potato cultivars: Many common and few cultivar-dependent taxa. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2011;75:497–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welbaum GE, Sturz AV, Dong Z, Nowak J. Managing soil microorganisms to improve productivity of agro-ecosystems. CRC Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2004;23:175–193. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W, Li Z, Liu H, et al. The effect of long-term continuous cropping of black pepper on soil bacterial communities as determined by 454 pyrosequencing. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JY, Dai C, Shan JJ, et al. Determination of the effect of Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Breit. on nervous system development by proteomics. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;213:221–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Wang T, Li H, et al. Variations of soil nitrogen-fixing microorganism communities and nitrogen fractions in a Robinia pseudoacacia chronosequence on the Loess Plateau of China. CATENA. 2019;174:316–323. [Google Scholar]

- Xue T, Zhang H, Zhang Y, et al. Full-length transcriptome analysis of shade-induced promotion of tuber production in Pinellia ternata. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:565. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-2197-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamioudis C, Pieterse CMJ. Modulation of host immunity by beneficial microbes. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2012;25:139–150. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-11-0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JY, Guo QS, Zheng DS. Genetic diversity analysis of Pinellia ternata based on SRAP and TRAP markers. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2013;50:258–265. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Cai Y, Wang L, et al. Optimization of processing technology of Rhizoma Pinelliae Praeparatum and its anti-tumor effect. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15:101–106. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v15i1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang GH, Jiang NH, Song WL, et al. De novo sequencing and transcriptome analysis of Pinellia ternata identify the candidate genes involved in the biosynthesis of benzoic acid and ephedrine. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Li Q, Chen Y, et al. Dynamic change in enzyme activity and bacterial community with long-term rice cultivation in mudflats. Curr Microbiol. 2019;76:361–369. doi: 10.1007/s00284-019-01636-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Zhang Z, Xiong Y, et al. Stearic acid desaturase gene negatively regulates the thermotolerance of Pinellia ternata by modifying the saturated levels of fatty acids. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;166:113490. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Ni T, Li Y, et al. Responses of bacterial communities in arable soils in a rice-wheat cropping system to different fertilizer regimes and sampling times. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zi H, Jiang Y, Cheng X, et al. Change of rhizospheric bacterial community of the ancient wild tea along elevational gradients in Ailao mountain, China. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.