Abstract

Sleep monitoring may provide markers for future Alzheimer’s disease; however, the relationship between sleep and cognitive function in preclinical and early symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease is not well understood. Multiple studies have associated short and long sleep times with future cognitive impairment. Since sleep and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease change with age, a greater understanding of how the relationship between sleep and cognition changes over time is needed. In this study, we hypothesized that longitudinal changes in cognitive function will have a non-linear relationship with total sleep time, time spent in non-REM and REM sleep, sleep efficiency and non-REM slow wave activity.

To test this hypothesis, we monitored sleep-wake activity over 4–6 nights in 100 participants who underwent standardized cognitive testing longitudinally, APOE genotyping, and measurement of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers, total tau and amyloid-β42 in the CSF. To assess cognitive function, individuals completed a neuropsychological testing battery at each clinical visit that included the Free and Cued Selective Reminding test, the Logical Memory Delayed Recall assessment, the Digit Symbol Substitution test and the Mini-Mental State Examination. Performance on each of these four tests was Z-scored within the cohort and averaged to calculate a preclinical Alzheimer cognitive composite score. We estimated the effect of cross-sectional sleep parameters on longitudinal cognitive performance using generalized additive mixed effects models. Generalized additive models allow for non-parametric and non-linear model fitting and are simply generalized linear mixed effects models; however, the linear predictors are not constant values but rather a sum of spline fits.

We found that longitudinal changes in cognitive function measured by the cognitive composite decreased at low and high values of total sleep time (P < 0.001), time in non-REM (P < 0.001) and REM sleep (P < 0.001), sleep efficiency (P < 0.01) and <1 Hz and 1–4.5 Hz non-REM slow wave activity (P < 0.001) even after adjusting for age, CSF total tau/amyloid-β42 ratio, APOE ε4 carrier status, years of education and sex. Cognitive function was stable over time within a middle range of total sleep time, time in non-REM and REM sleep and <1 Hz slow wave activity, suggesting that certain levels of sleep are important for maintaining cognitive function.

Although longitudinal and interventional studies are needed, diagnosing and treating sleep disturbances to optimize sleep time and slow wave activity may have a stabilizing effect on cognition in preclinical or early symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, EEG, memory, mild cognitive impairment, biomarkers

Lucey et al. investigate associations between sleep and longitudinal cognitive function in impaired and unimpaired older adults. The results show that sleep duration, sleep efficiency, and slow wave activity are all predictive of cognitive decline in a non-linear inverse ‘U-shaped’ relationship.

See Coulthard and Blackman (doi:10.1093/brain/awab315) for a scientific commentary on this article.

Introduction

Deposition of amyloid-β as insoluble parenchymal plaques and intracellular accumulation of aggregated, hyperphosphorylated tau as neurofibrillary tangles throughout the neuropil are key steps in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease that lead to synaptic and neuronal loss, cognitive dysfunction and eventual dementia.1,2 Tau hyperphosphorylation (p-tau) is an early step in tau-mediated neurodegeneration. Amyloid PET scans show deposition of amyloid as insoluble fibrillar amyloid-β deposits (i.e. amyloid-positive). The concentration of amyloid-β42 in the CSF decreases with amyloid deposition and is also a marker of amyloid status.3 Amyloid PET scans show increasing amounts of amyloid deposition while an individual is still cognitively normal, although CSF total tau (t-tau) begins to increase.4-6 Tau PET scans, which show paired helical filament pathology, only become positive many years after amyloid PET scans become positive, and there are already decreases in CSF amyloid-β42 and increases in t-tau and p-tau around the time that clinical symptoms appear.7,8 Although soluble amyloid-β42, p-tau and t-tau in human CSF are biomarkers for early (amyloid-β42) and increasing (t-tau and p-tau) amyloid deposition, the CSF t-tau/amyloid-β42 ratio is associated with increased amyloid deposition in the brain4 and is superior to single biomarkers at predicting the risk of clinical decline and conversion to dementia.9

Recent work supports a role for sleep disturbances as markers for and/or potential cause(s) of Alzheimer’s disease pathology.10 The risk of developing both Alzheimer’s disease and sleep disturbance increases with age.11,12 During normal ageing, multiple measures of sleep change, including decreased sleep efficiency, increased night-time awakenings, decreased sleep spindles and increased time in non-REM (NREM) sleep stage 1 or drowsiness.13 Furthermore, sleep measures, such as time spent in NREM stage 3 sleep, change with age and sex,13 making their relationships to future Alzheimer’s disease risk difficult to define. Sleep disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnoea and restless legs syndrome, result in sleep disturbance and are age-associated.14,15 Although controlling for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease markedly attenuates the commonly held notion of diminishing cognitive performance as a function of age alone,16 poor sleep has been associated with worse cognitive performance in older adults.17

Prior work delving into the relationship between sleep duration and future risk of cognitive performance have shown inconsistent results.18–20 For instance, a study of 1844 females aged 70–81 years who completed baseline cognitive assessments and were retested 2 years later were found to have worse cognitive decline over time if their self-reported sleep duration was ≤5 h/night compared to 7 h/night; females who reported sleeping ≥9 h/night did not experience cognitive decline.21 In contrast, a cross-sectional study of 3212 individuals aged ≥60 years found that those individuals who self-reported sleeping ≥11 h/night were found to have poor cognitive function compared to participants who reported sleeping 7 h/night.22 Multiple studies have also shown that both shorter and longer sleep duration are associated with decreased cognitive performance.23,24 For example, a cross-sectional study of 1115 individuals aged ≥60 years found that both self-reported short (<6 h/night) and long (>8 h/night) sleep durations were associated with cognitive impairment.25 These studies were performed in older adults with <10 years of follow-up. Recent work in middle-aged adults followed for up to 25 years found that short sleep duration was associated with an increased risk of dementia.26

There is an increasing recognition that the relationship between cognition, Alzheimer’s disease risk factors and biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease is non-linear. For instance, rates of amyloid and tau accumulation in the brain change with both age and apolipoprotein E4 (APOE ε4) allele carrier status. CSF p-tau levels increase in APOE ε4 non-carriers from an age of ∼55 years and plateau at ∼75 years, whereas APOE ε4 carriers show a linear increase in CSF p-tau starting at an age of ∼50 years.27 Another study reported that the relationship between longitudinal memory performance and blood pressure is non-linear and varies with age, depending on the baseline blood pressure.28

The differing results from studies of sleep duration and risk of cognitive impairment may be due to a non-linear relationship between total sleep time and cognition. A meta-analysis of nine cohort studies involving 22 187 participants with longitudinal cognitive assessments and both self-reported sleep duration and that objectively measured with actigraphy found that the relationship between sleep duration and the risk of cognitive dysfunction showed a U-shaped dose-response relationship with the lowest risk of cognitive impairment occurring in those with a sleep duration of 7–8 h/day.29 A second meta-analysis of 11 cross-sectional and seven prospective cohort studies of 97 264 participants also found that both short and long self-reported sleep durations were associated with increased cognitive impairment.30

Sleep has been proposed as a potential marker for Alzheimer’s disease pathology that could be non-invasively monitored to assess the risk of future Alzheimer’s disease or track responses to interventions during clinical trials. Since both sleep and Alzheimer’s disease risk change with age and potentially interact, a greater understanding of how sleep and cognition change with age and at different stages of Alzheimer’s disease pathology is needed. Previous studies have primarily relied on self-reported total sleep time and other sleep measures. Furthermore, measures of sleep quality such as sleep efficiency and NREM slow wave activity (SWA) have been associated with Alzheimer’s disease pathology31–33 and cognitive function.34–36

Participants in previous studies of sleep and cognition have not been well characterized for Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers or genetic risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease such as their APOE ε4 carrier status. In this study, we hypothesized that longitudinal changes in cognitive function will have a non-linear relationship with total sleep time, time spent in NREM and REM sleep, sleep efficiency, and NREM SWA. To test this hypothesis, we objectively monitored sleep-wake activity with a single-channel EEG device over 4–6 nights in 100 participants who also underwent standardized annual cognitive testing, genotyping for APOE ε4 status and measurement of CSF Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers.

Materials and methods

Participants

Data from 100 community-living participants enrolled in longitudinal studies at the Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center (ADRC), Washington University in St. Louis, were used. Participants were included if they had completed at least 4 nights of single-channel EEG monitoring, one lumbar puncture for CSF analysis, genotyping for APOE ε4 status and two or more neuropsychological testing visits. All individuals participating in Knight ADRC studies undergo annual clinical and cognitive assessments by a clinician. Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) is used in longitudinal studies and clinical trials for staging dementia in general and in dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease.37 For this analysis, participants were either classified as cognitively normal (CDR 0), or cognitively impaired (CDR > 0). All but one of the cognitively impaired participants were only mildly impaired (CDR 0.5). At the Knight ADRC, the standard protocol is to access the CDR annually. The CDR and other neuropsychological tests have been very stable tools for assessing the stage and degree of impairment in dementia over many years in our cohort.38 This study was approved by the Washington University in St. Louis Institutional Review Board and each participant provided signed informed consent.

Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite

Individuals completed a neuropsychological testing battery at each clinical visit that included the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT), the Logical Memory Delayed Recall Test from the Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised, the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). These tests were administered and scored by experienced psychometrists. Performance on each of these four tests was Z-scored within the cohort and averaged in order to calculate a Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite (PACC) score.39

Sleep monitoring and EEG power analysis

Sleep monitoring was performed as previously described.40 To briefly review, sleep was recorded longitudinally in all participants at home for up to 6 nights using sleep logs, actigraphy (Actiwatch 2, Philips Respironics) and a single-channel EEG device worn on the forehead (Sleep Profiler, Advanced Brain Monitoring). Average total sleep time, time in NREM sleep stages 2 and 3 (time in NREM), time in REM sleep, sleep efficiency and <1 Hz and 1–4.5 Hz NREM SWA were used in all analyses. Sleep efficiency was calculated based on the lights off and lights on times for the single-channel EEG studies and were corroborated with sleep logs. Single-channel EEG sleep studies were visually scored by registered polysomnographic technologists using criteria adapted from the standard American Academy of Sleep Medicine criteria.41 Nights were excluded if >10% of the recording was artefactual or if the bed and rise times did not match the sleep log and/or actigraphy. All participants needed at least 4 nights of single-channel EEG monitoring that met these criteria to be included. Time in NREM sleep stages 2 and 3 were combined, because we found this has a higher level of agreement with polysomnography.41 NREM SWA was calculated for each single-channel EEG study using MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA), and the average NREM SWA was used in the analysis. As previously described,41 a band-pass (two-way least-squares finite impulse response) filter between 0.5 and 40 Hz was applied to the single-channel EEG data. Spectral analysis was performed in consecutive 5-s epochs (Welch method, Hamming window, no overlap). SWA power was calculated by averaging the power in the frequency bins of 0.5–1.0 Hz and 1.0–4.5 Hz. To semi-automatically remove artefactual epochs, power in the 20–30 and 0.5–4.5 Hz bands for each electrode across all epochs of a recording were displayed. The operator (B.P.L.) then selected a threshold between the 95 and 99.5% threshold of power to remove artefactual epochs. The data were then natural log-transformed to normalize the data.

CSF biomarkers

CSF was collected under a standardized protocol.42 After fasting overnight, participants underwent a lumbar puncture at 8 a.m., when 20–30 ml of CSF was collected by gravity drip into a 50-ml conical tube using a 22-gauge atraumatic Sprotte spinal needle, gently inverted to disrupt potential gradient effects and centrifuged at low speed to pellet any cellular debris. Samples were aliquoted (500 μl) in polypropylene tubes and stored at −80°C until analysis. CSF amyloid-β42, t-tau and p-tau 181 were measured as previously described using an automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Elecsys on the cobas e 601 analyzer, Roche).42

Statistical analysis

For demographic variables at the time of sleep monitoring, group differences between cognitively normal (CDR 0) and impaired (CDR > 0) participants were compared using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. We then used generalized additive mixed effects models43,44 to estimate the effect of cross-sectional total sleep time, sleep efficiency, time in NREM sleep, time in REM sleep and <1 Hz and 1–4.5 Hz NREM SWA on longitudinal cognitive performance measured by the PACC scores. Generalized additive models are powerful tools that allow for non-parametric and non-linear model fitting in the context of frequentist statistics. A generalized additive model is simply a generalized linear mixed effects model; however, the linear predictors are not constant values but rather a sum of spline fits. Generalized additive models have been used in sample sizes ≤ 10045–47 and 100–20048–50 to study non-linear relationships in neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases. We included an individual participant identifier as a random effect since these were longitudinal data. Generalized additive models implemented in the R Package mgcv44 apply basis functions as predictors.

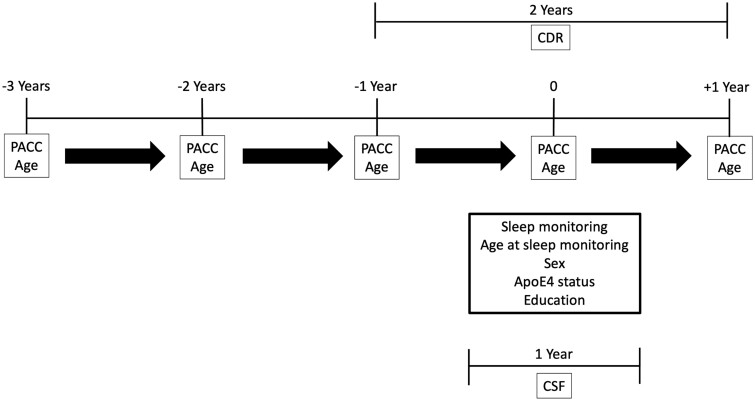

For each of the generalized additive models in this analysis, we fit splines to age at PACC score completion, the sleep parameter of interest (total sleep time, time in NREM sleep, time in REM sleep, sleep efficiency or NREM SWA) and the individual random effect where the PACC score was the dependent variable of interest. In these analyses, we included APOE ε4 status, sex (referenced to female), years of education, age at sleep study participation, estimated Alzheimer’s disease pathology measured by the CSF t-tau/CSF amyloid-β42 ratio within 1 year of sleep monitoring and CDR within 2 years of sleep monitoring as covariates. An overview of the timing of data collection is shown in Fig. 1. The CDR was included in the model, because it is the gold standard for overall clinical and cognitive status in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and allows for overall stage of Alzheimer’s disease to be controlled for in the models. Moreover, the CDR does not use cognitive scores and is the marker often used as the primary outcome in clinical trials. Although the CDR is the gold standard for clinical and cognitive status, the use of biomarkers and neuropsychological testing helps to supplement the diagnosis. The CSF t-tau/amyloid-β42 ratio is a marker for amyloid pathology and future risk of cognitive impairment, because once an individual starts to accumulate amyloid and the ratio increases, they will eventually progress to symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease.4,51 A generalized form of this model is shown as Equation 1, where s() indicates that a spline fit was applied. The distributions of both age at PACC and sleep parameter of interest were assumed to be Gaussian.

Figure 1.

Overview of data collection. Sleep monitoring was performed over 4–6 nights in all participants. CSF was collected within ≤1 year of sleep monitoring and CDR measured ≤2 years of sleep monitoring. Participants underwent annual cognitive assessments before and after sleep monitoring to generate PACC scores.

| (1) |

The maximum number of knots for each spline fit was limited to four to minimize overfitting. The number of knots specifies the dimension of the basis function used to represent the smoothing parameter and was selected using an iterative backfitting algorithm. Cyclic cubic regression splines were used for smoothing the age at PACC and sleep parameter predictors, and ridge penalties were used for smoothing random effects. We used generalized cross-validation for smoothing parameter estimation. We also performed generalized linear models with the same covariates as used in the generalized additive models: sleep parameter, CDR, CSF t-tau/amyloid-β42, age at sleep study, age at PACC, APOE ε4 status, sex and education. Generalized linear models account for the dependencies among the longitudinal measurements. All model variables were treated as fixed effects with random intercepts and slopes to accommodate individual variation. All analyses were performed using R.

Data and material availability

All of the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All code associated with this analysis is freely available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Participant characteristics

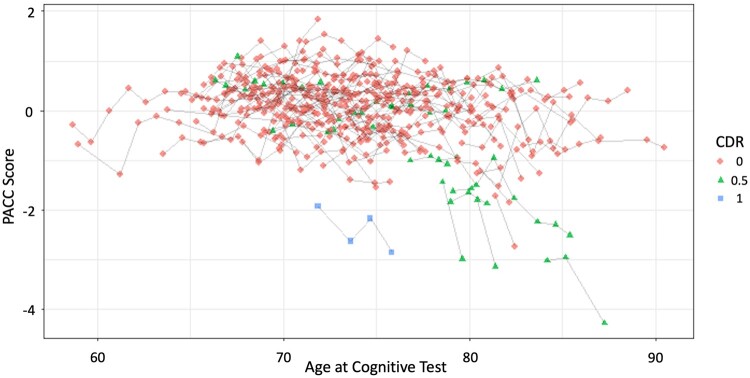

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of cognitively normal (CDR 0) and cognitively impaired (CDR > 0) participants at the time of sleep study monitoring. There were no significant differences in the CDR 0 and CDR > 0 groups with regard to age, sex, years of education, APOE ε4 status, race, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, NREM SWA, apnoea-hypopnoea index (measure of sleep apnoea), years between PACC assessments, number of PACC assessments, or years of follow-up. CDR > 0 participants had significantly more participants with a periodic limb movement index > 15 (measure of periodic leg movements during sleep) than CDR 0 participants. Twelve individuals (12%) had a baseline CDR of 0.5 or greater. A single individual had a baseline CDR of 1.0. No individuals progressed from CDR 0 to 0.5 or from 0.5 to 1.0 during the follow-up window, and participants had on average 4–5 years of follow-up (Table 1) with a range of 2–12 years (Supplementary Fig. 1). Most participants (78%) underwent cognitive assessments that crossed the date of sleep monitoring, 22% undertook these before the date of sleep monitoring, while none underwent them after the date of sleep monitoring. A detailed comparison between the baseline and final PACC scores, including individual component assessments, can be found in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. As expected, a greater percentage of CDR > 0 participants showed greater evidence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology as measured by the CSF t-tau/amyloid-β42 ratio. The unadjusted relationship between PACC scores and age is shown in Fig. 2. The change in longitudinal PACC scores was in the range −1 to 1 for the majority of participants, but a subset of participants >70 years of age showed greater decreases in PACC performance over time.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

|

Cognitively normal

CDR = 0 (n = 88) |

Cognitively impaired

CDR > 0 (n = 12) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at sleep study, years, mean (SD) | 75.23 (4.99) | 78.27 (5.61) | 0.054 |

| Sex, number of males (%) | 43 (48.9) | 6 (50.0) | 1.000 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 16.67 (2.36) | 16.58 (2.07) | 0.903 |

| APOE ε4 status: n APOE ε4+ (%) | 29 (33.0) | 5 (41.7) | 0.785 |

| Race | 0.431 | ||

| More than one (%) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| African American (%) | 10 (11.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Caucasian (%) | 77 (87.5) | 12 (100.0) | |

| Total sleep time, h, mean (SD) | 6.32 (0.77) | 6.47 (0.84) | 0.546 |

| Sleep efficiency, %, mean (SD) | 79.33 (8.50) | 76.40 (9.60) | 0.273 |

| <1 Hz NREM SWA, μV2/Hz, mean (SD) | 59.85 (46.4) | 66.57 (45.8) | 0.651 |

| 1–4.5 Hz NREM SWA, μV2/Hz, mean (SD) | 17.63 (10.80) | 18.70 (10.30) | 0.757 |

| AHI, number of respiratory events/h of monitoring time (%) | 0.156 | ||

| None (<5) | 33 (37.5) | 6 (50.00) | |

| Mild (5–15) | 39 (44.3) | 5 (41.7) | |

| Moderate (15–30) | 15 (17.0) | 0 | |

| Severe (>30) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (8.3) | |

| PLMI, number of leg movements/h of monitoring time (%) | 0.003 | ||

| None (<15) | 48 (54.5) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Low (15–45) | 17 (19.3) | 7 (58.3) | |

| High (>45) | 23 (26.1) | 4 (33.3) | |

| T-tau/amyloid-β42 ratio, n (%) | 0.007 | ||

| Amyloid-negativea | 55 (62.5) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Amyloid-positivea | 33 (37.5) | 10 (83.3) | |

| Years between PACC assessments | 1.15 | 1.12 | 0.725 |

| Number of PACC assessments (SD) | 5.89 (3.00) | 4.75 (3.77) | 0.236 |

| Years of follow-up (SD) | 5.49 (3.37) | 4.07 (3.80) | 0.180 |

Comparisons were made by unpaired t-test. AHI = apnoea-hypopnea index; APOE ε4+ = apolipoprotein E ε4-positive status; PLMI = periodic limb movement index; SD = standard deviation.

aT-tau/amyloid-β42 cut-point for amyloid status = 0.211.42

Figure 2.

Distribution of longitudinal PACC scores by age. Spaghetti plots of the PACC scores are shown for each participant at the age when testing was performed. Overall, cognitive performance on the PACC was relatively stable between −1 and 1 for the majority of participants. A subset of participants who were >70 years of age at baseline showed more rapid decline in PACC performance.

Sleep and longitudinal cognitive performance are non-linear

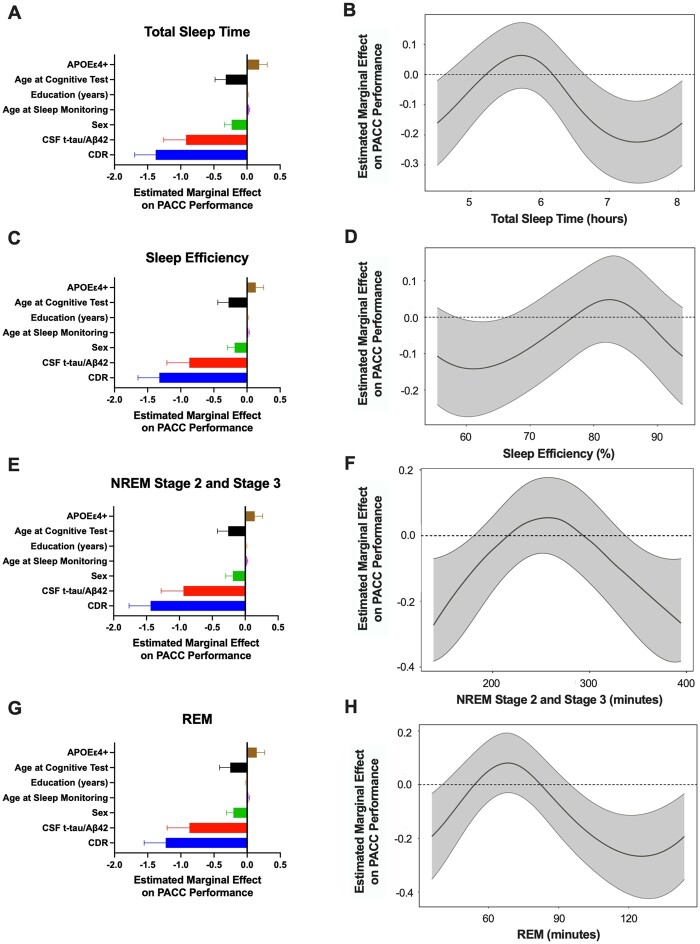

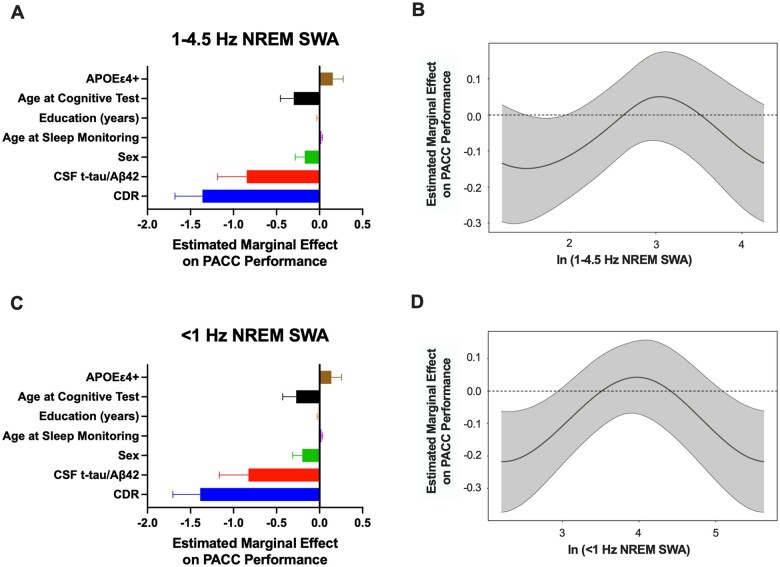

To assess the relationship between sleep and longitudinal changes in cognitive performance, we performed generalized additive models of total sleep time, sleep efficiency, time in NREM stage 2 and 3, time in REM, <1 Hz and 1–4.5 Hz NREM SWA with longitudinal PACC scores, age at the time of cognitive testing, age at the time of sleep monitoring, sex, CDR score within 2 years of sleep monitoring, APOE ε4 status, CSF t-tau/amyloid-β42 ratio and years of education. We found that the longitudinal PACC performance varied with the value of each sleep parameter. For total sleep time, sleep efficiency, time in NREM stage 2 and 3, time in REM, and NREM SWA, both the sleep parameter and age at PACC were found to have significant spline fits in the fully adjusted model. CDR, CSF t-tau/amyloid-β42 ratio and sex (male effect) showed a significant inverse relationship with longitudinal PACC scores for all models. Age at the sleep study visit and APOE ε4+ status had positive linear relationships with PACC scores in all models. Years of education was not significant in any model (Tables 2 and 3, Figs 3A, C, E, F and 4A and C).

Table 2.

Generalized additive models of the relationship between longitudinal PACC scores and total sleep time, sleep efficiency, NREM stage 2 and stage 3 and REM sleep

| Generalized additive models | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sleep time | Sleep efficiency | NREM stages 2 and 3 | REM | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Spline fit | EDF | EDF | EDF | EDF | ||||

| Sleep parameter | 2.377*** | 2.808** | 2.6100674*** | 1.6478*** | ||||

| Age at PACC | 2.836*** | 2.821*** | 2.8406516*** | 2.7936*** | ||||

| Participant ID | 1.118 × 10−3 | 9.09 × 10−2 | 4.752 × 10−4 | 0.2533 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Covariate | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI |

|

| ||||||||

| CDR | −1.592*** | −1.903, −1.281 | −1.551*** | −1.880, −1.222 | −1.589*** | −1.913, −1.266 | −1.423*** | −1.744, −1.101 |

| CSF t-tau/amyloid-β42 | −1.171*** | −1.500, −0.843 | −1.047*** | −1.386, −0.708 | −1.140*** | −1.476, −0.804 | −1.108*** | −1.445, −0.770 |

| Age at sleep study | 0.038*** | 0.022, 0.055 | 0.025** | 0.008, 0.042 | 0.037*** | 0.019, 0.054 | 0.026** | 0.009, 0.042 |

| APOE ε4+ | 0.146* | 0.027, 0.266 | 0.135* | 0.011, 0.258 | 0.167** | 0.048, 0.287 | 0.179** | 0.059, 0.299 |

| Sex (male effect) | −0.236*** | −0.343, −0.129 | −0.181** | −0.290, −0.073 | −0.177** | −0.288, −0.066 | −0.231*** | −0.338, −0.123 |

| Education (years) | 0.006 | −0.018, 0.030 | 0.012 | −0.014, 0.038 | 0.007 | −0.018, 0.032 | 0.008 | −0.017, 0.033 |

| Intercept | −2.600*** | −3.938, −1.261 | −1.593* | −3.023, −0.163 | −2.537*** | −3.927, −1.147 | −1.658* | −3.033, −0.284 |

n = 100; dependent variable = PACC. EDF = effective degrees of freedom.

P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Table 3.

Generalized additive models of the relationship between longitudinal PACC scores and <1 Hz NREM SWA and 1–4.5 Hz NREM SWA

| Generalized additive models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ln (<1 Hz NREM SWA) | Ln (1–4.5 Hz NREM SWA) | |||

| Spline fit | EDF | EDF | ||

| Sleep parameter | 2.55368** | 2.8279655** | ||

| Age at PACC | 2.84824*** | 2.8507198*** | ||

|

Participant ID |

0.06847 |

2.473 × 10−4 |

||

| Covariate | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI |

|

| ||||

| CDR | −1.384*** | −1.702, −1.065 | −1.365*** | −1.681, −1.048 |

| CSF t-tau/amyloid-β42 | −0.879*** | −1.224, −0.534 | −0.925*** | −1.269, −0.581 |

| Age at sleep study | 0.026** | 0.009, 0.043 | 0.023** | 0.006, 0.040 |

| APOE ε4+ | 0.131* | 0.011, 0.252 | 0.155* | 0.035, 0.274 |

| Sex (male effect) | −0.240*** | −0.360, −0.121 | −0.223*** | −0.343, −0.103 |

| Education, years | 0.001 | −0.024, 0.026 | −0.007 | −0.032, 0.018 |

| Intercept | −1.635* | −3.006, −0.263 | −1.272 | −2.639, 0.094 |

n = 100; dependent variable = PACC. EDF = effective degrees of freedom.

P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Longitudinal PACC performance and sleep time are non-linearly related. In 100 participants, generalized additive models found that the association of longitudinal PACC performance with total sleep time, sleep efficiency, time in NREM stage 2 and stage 3 sleep, and REM sleep was non-linear after adjusting for APOE ε4-positive status, age at cognitive test, age at sleep monitoring, education, sex (male effect), CSF t-tau/amyloid-β42 and CDR. For the models of total sleep time (A), sleep efficiency (C), time in NREM stage 2 and 3 sleep (E), and time in REM sleep (G), the estimated marginal effect on longitudinal PACC performance (i.e. change in PACC score over time) is shown for each of the covariates. The estimated smoothed spline function of total sleep time in the fully adjusted model shows that a total sleep time <4.5 h and >6.5 h was associated with worse PACC performance over time (B). For sleep efficiency (D), PACC performance was generally unchanged over time. Time spent in NREM stage 2 and 3 (F) and in REM sleep (H) showed inverse U-shaped relationships with longitudinal PACC performance.

Figure 4.

Longitudinal PACC performance and NREM SWA are non-linearly related. In 100 participants, generalized additive models found that the association of longitudinal PACC performance with NREM SWA was non-linear after adjusting for APOE ε4-positive status, age at cognitive test, age at sleep monitoring, education, sex (male effect), CSF t-tau/amyloid-β42 and CDR. For the models of 1–4.5 Hz NREM SWA (A) and <1 Hz NREM SWA (C), the estimated marginal effect on longitudinal PACC performance (i.e. change in PACC score over time) is shown for each of the covariates. The estimated smoothed spline function of ln (1–4.5 Hz NREM SWA) in the fully adjusted model shows a non-linear relationship with PACC performance generally unchanged over time (B). Ln (<1 Hz NREM SWA) showed inverse U-shaped relationships with longitudinal PACC performance (D).

The estimated spline functions for total sleep time, sleep efficiency, time in NREM, time in REM, and NREM SWA showed bimodal distributions. For instance, total sleep times of <4.5 h and >6.5 h were associated with worse cognitive performance over time (Fig. 3B). However, there was no change in PACC after adjusting for the model covariates in between these total sleep durations (i.e. the 95% confidence intervals are not above or below zero change in PACC performance over time). Although sleep efficiency was non-linearly related to longitudinal PACC performance, the 95% confidence intervals crossed zero (i.e. no significant change in PACC scores over time) except between 60–65% where PACC performance decreased ∼−0.1 (Fig. 3D). Both time in NREM and time in REM sleep showed an inverse U-shaped relationship with change in PACC scores over time (Fig. 3F and H). NREM SWA (1–4.5 Hz) was similar to sleep efficiency with 95% confidence intervals crossing zero, but low and high <1 Hz NREM SWA was related with worsening PACC performance of ∼−0.2 (Fig. 4B and D). These findings suggest that total sleep time, time in NREM, time in REM, and <1 Hz NREM SWA are more sensitive measures for longitudinal PACC performance than sleep efficiency or 1–4.5 Hz NREM SWA.

To test if generalized additive models best fit our data, we used linear mixed effects models adjusted for the same covariates to test if a linear function describes the relationship between longitudinal PACC and total sleep time, sleep efficiency, time in NREM stage 2 and 3, time in REM, and <1 Hz and 1–4.5 Hz NREM SWA. Total sleep time was found to have an inverse relationship with longitudinal PACC (Supplementary Table 3). In addition to total sleep time, CDR, CSF t-tau/amyloid-β42 ratio, and sex (male effect) were also significant. Sleep efficiency, time in NREM stage 2 and 3, time in REM, <1 Hz NREM SWA, and 1–4.5 Hz NREM SWA, however, were not significant using a generalized linear model although CDR, CSF t-tau/amyloid-β42 ratio, and sex remained significant (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

To understand how each of the four cognitive tests that comprise the PACC change with two representative sleep measures (total sleep time and <1 Hz NREM SWA), we included the MMSE, FCSRT, DSST, and Logical Memory tests as the dependent variable in our generalized additive models (Supplementary Tables 5–8). Total sleep time showed a similar association with the MMSE, FCSRT, and Logical Memory Test as with the PACC, but the DSST did not. NREM SWA <1 Hz was also significantly related to the FCSRT, DSST, and Logical Memory Test but not the MMSE. To test if the four cognitive tests that make up the PACC are linearly associated with sleep, we included the MMSE, FCSRT, DSST, and Logical Memory tests as the dependent variable in our generalized linear models (Supplementary Tables 9–12). We found that the total sleep time was inversely related to FCSRT and Logical Memory tests, but not MMSE or DSST; <1 Hz NREM SWA was not linearly associated any individual cognitive test.

Discussion

In this study, we observed that the relationship between cross-sectional measures of total sleep time, time in NREM stage 2 and 3, time in REM, and <1 Hz NREM SWA and cognitive function over time, as assessed by the PACC, was non-linear. This relationship was seen even after adjusting for multiple potential confounders that can affect sleep and cognition, including age, CSF markers of Alzheimer’s disease pathology, APOE ε4 allele carrier status, years of education and sex. These findings have important implications for using sleep to track the risk of developing cognitive impairment in the clinic or in response to an intervention in a clinical trial. Furthermore, these results support the suggestion that sleep measures have an optimal middle range where PACC scores are stable and suggest targets for sleep interventions to help maintain cognitive function in individuals at risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. We also found that the Logical Memory Test, a story memory test, was significantly associated with both total sleep time and <1 Hz NREM SWA. The MMSE, a general cognitive test, was associated with total sleep time while the DSST, a test of multiple cognitive functions, was associated with <1 Hz NREM SWA. The FCSRT, a word list test of episodic memory, was associated with both total sleep time and <1 Hz NREM SWA. Further research is needed to determine if specific sleep measures are associated with longitudinal changes on specific neuropsychological tests.

Our study supports previously reported associations between increased risk of cognitive impairment and both short and long total sleep time. Furthermore, time spent in both NREM and REM sleep showed similar non-linear relationships suggesting that the relationship between total sleep time and cognitive function is not due to increases or decreases in specific sleep stages. However, future studies are needed to test this hypothesis. Unlike prior studies that used self-reported total sleep time, we objectively assessed total sleep time over multiple nights using a single-channel EEG device that compares favourably to polysomnography.41 Comparing our findings to previous work for cut-offs of short and long total sleep time must account for different methods used to measure sleep duration. We have recently shown in our cohort that self-reported total sleep time is ∼1 h longer than that measured by the single-channel EEG device on the same night.52 Fewer studies have investigated the relationship between cognitive performance and sleep duration measured by polysomnography.53–55 In those studies, participants were monitored with polysomnography for only 1 night in either a sleep lab or at home, which may not have represented a typical night of sleep. In contrast, all participants in our study had sleep-wake activity measured by single-channel EEG for 4–6 nights at home, which more likely represented how each participant typically sleeps. The single-channel EEG is recorded from electrodes placed on the forehead, however, and provides more limited monitoring of sleep-wake activity compared with polysomnography.

The estimated marginal effect of total sleep time, time in NREM, and time in REM on PACC performance was approximately −0.2 to −0.3 at the shortest and longest sleep times. In the generalized additive model, this was less than the estimated marginal effect of CDR and CSF t-tau/amyloid-β42 (−1.0 to −1.5), greater than the effects of APOE ε4 status and education, but similar to age and sex. Although longitudinal PACC scores and total sleep time had a significant inverse relationship with the simpler linear model, we think a non-linear model better explains findings reported in the literature.

The estimated marginal effect of low and high <1 Hz NREM SWA on longitudinal PACC performance was approximately −0.2, less than the effect of CDR (−1.5) and CSF t-tau/amyloid-β42 (−0.5 to −1.0) in our model but comparable to age and sex. Longitudinal PACC scores and NREM SWA were not significantly associated in the linear model, suggesting that the non-linear model more accurately represents these relationships. The 1–4.5 Hz NREM SWA had a smaller marginal effect on PACC performance than the <1 Hz NREM SWA, supporting the suggestion that <1 Hz slow oscillations as a critical marker of cognitive function.

Decreased NREM SWA is correlated with poor cognitive performance34 and Alzheimer’s disease pathology.32,33 Increased SWA may be a marker of cortical dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Disturbed neuronal activity in early preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, resulting in excitation/inhibition imbalance with neuronal hyperexcitability and hypersynchrony, is hypothesized to connect structural Alzheimer’s disease brain pathology with cognitive dysfunction.56–58 For instance, resting EEG studies have shown increases in SWA within individuals with cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease59,60 and resting state theta-delta hypersynchrony has also been correlated with both amyloid and tau pathology.61 Although our participants showed no evidence of seizure activity, clinically silent focal interictal discharges and seizures in the hippocampus have been reported in mildly impaired patients with Alzheimer’s disease.62 Patients with focal epilepsy and evidence of neuronal hyperexcitability (e.g. interictal spikes, seizures) have increased NREM SWA and reduced daytime learning compared to control participants.63 This example suggests how occult hyperexcitability may increase NREM SWA and decrease cognitive performance. Moreover, individuals with REM sleep behaviour disorder, a parasomnia that predicts later occurrence of synucleinopathies such as Parkinson’s disease, have increased NREM SWA compared to controls,64 suggesting that similar findings may be seen in the early stages of other neurodegenerative diseases. Future studies with high density EEG are needed in individuals at different stages of Alzheimer’s disease to characterize sleep’s effect on longitudinal cognitive performance, including assessment of sleep spindles, <1 Hz NREM slow waves, slow oscillation-spindle coupling that have been shown to decouple with age65 and Alzheimer’s disease66 and regional differences.

Decreased sleep efficiency is a marker of poor sleep quality and is associated with worse cognitive function.35,36 Higher sleep efficiency is consistent with higher sleep quality. The estimated marginal effect of sleep efficiency on longitudinal PACC scores was minimal and suggested that sleep efficiency <65% was associated with minimally decreased cognitive performance. These are minor effects compared to total sleep time and NREM SWA. Longitudinal PACC scores and sleep efficiency were not significantly associated in the linear model.

Our cohort is richly characterized for genetic risk factors and biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease that were not available for previous studies and thus allow us to compare the effect of total sleep time, sleep efficiency, time in NREM stage 2 and 3, time in REM, <1 Hz and 1–4.5 Hz NREM SWA on cognitive performance relative to other factors such as CDR or CSF t-tau/amyloid-β42. These results suggest that a certain range of total sleep time and <1 Hz NREM SWA are important for maintaining cognitive function. Participant cognitive performance on the PACC decreased outside of this middle or optimal range. The clinical significance of this cognitive change is unclear. A recent paper compared PACC performance in amyloid-negative and amyloid-positive cognitively normal participants enrolled in three large Alzheimer’s disease cohort studies.67 Based on the separation between cognitively unimpaired individuals and early mild cognitive impairment, the authors concluded that 1 SD on the PACC (i.e. one point of additional decline in amyloid-positive participants compared to amyloid-negative participants) could be taken as an approximate benchmark for clinically meaningful decline for interventional trials involving preclinical or presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease (e.g. cognitively normal amyloid-positive). Given that our cohort is 88% cognitively unimpaired and there are known practice effects with the PACC,68 a marginal effect of sleep on PACC performance ranging from −0.2 to −0.3 is clinically significant; further, this estimated marginal effect is comparable to age in our models, the greatest risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. The effect of sleep efficiency is small, however, and is likely not clinically significant. An exciting possibility from this study is that diagnosing and treating sleep disturbances, such as sleep apnoea or insomnia, to optimize sleep duration and NREM SWA may have a stabilizing effect on cognition in preclinical or early symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease.

However, many unanswered questions remain. We need to understand if there are differences in the optimal characteristics of sleep needed to preserve cognitive function and the optimal characteristics of sleep needed to prevent Alzheimer’s disease pathology, and if these relationships change with stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Also, colinear or linked factors may affect both sleep and cognitive decline. We have already discussed that sleep changes with age and sex, but this is likely an issue with other Alzheimer’s disease risk factors. For example, APOE ε4 has been associated with increased duration of NREM stage 3 sleep in cognitively normal older adults.69 Yet, APOE ε4 is also associated with increased risk of amyloid pathology that is associated with decreased sleep efficiency.31 A major limitation of this study is that cognitive assessments were longitudinal and preceded the cross-sectional sleep monitoring in 22% of participants. Both interventional studies and observational studies with longitudinal sleep and cognitive assessments are needed to see how the trajectories of different sleep parameters, especially total sleep time and <1 Hz NREM SWA, are related to the trajectory of cognitive performance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the participants for their contributions to this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health: P01 AG03991, P01 AG026276, P30 AG066444, K76 AG054863, UL1 TR000448, KL2 TR000450, R01 AG052550, and R01 AG057680. A Physician Scientist Training Award from the American Sleep Medicine Foundation and support from the Roger and Paula Riney Fund and the Daniel J. Brennan, MD Fund. The funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection, management, analysis, interpretation of the data or manuscript preparation.

Competing interests

B.P.L. consults for Merck and Eli Lilly; J.W. is currently employed at Bayer; J.C.M. is funded by NIH grants P30 AG066444; P01AG003991; P01AG026276 and U19 AG032438. Neither J.C.M. nor his family owns stock or has equity interest (outside of mutual funds or other externally directed accounts) in any pharmaceutical or biotechnology company. D.M.H. co-founded and is on the scientific advisory board of C2N Diagnostics. D.M.H. consults for Genentech, Idoria, Merck and Denali. Washington University receives research grants to the laboratory of D.M.H. from C2N Diagnostics and NextCure. J.H. is an advisory board member for Roche, Lundbeck and Takeda. A.H.B., E.C.L., C.D.T., J.S.M., O.H.B. and B.M.A. declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

Glossary

- CDR

Clinical Dementia Rating

- DSST

Digit Symbol Substitution Test

- FCSRT

Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test

- MMSE

Mini- Mental State Examination

- NREM

non-REM

- PACC

preclinical Alzheimer cognitive composite

- p-tau

phosphorylated tau

- SWA

slow wave activity

- t-tau

total tau

References

- 1. Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, et al. ; Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: An updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, et al. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Amyloid-beta-42 in humans. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(3):512–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Shah AR, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau and ptau(181) increase with cortical amyloid deposition in cognitively normal individuals: Implications for future clinical trials of Alzheimer's disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1(8-9):371–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fagan AM, Shaw LM, Xiong C, et al. Comparison of analytical platforms for cerebrospinal fluid measures of β-amyloid 1-42, total tau, and p-tau181 for identifying Alzheimer disease amyloid plaque pathology. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(9):1137–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barthélemy NR, Li Y, Joseph-Mathurin N, et al. ; Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network. A soluble phosphorylated tau signature links tau, amyloid and the evolution of stages of dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2020;26(3):398–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mattsson-Carlgren N, Andersson E, Janelidze S, et al. Aβ deposition is associated with increases in soluble and phosphorylated tau that precede a positive Tau PET in Alzheimer's disease. Sci Adv. 2020;6(16):eaaz2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gordon BA, Blazey TM, Christensen J, et al. Tau PET in autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease: Relationship with cognition, dementia and other biomarkers. Brain. 2019;142(4):1063–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blennow K, Shaw LM, Stomrud E, et al. Predicting clinical decline and conversion to Alzheimer's disease or dementia using novel Elecsys Aβ(1-42), pTau and tTau CSF immunoassays. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):19024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lucey BP. It's complicated: The relationship between sleep and Alzheimer's disease in humans. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;144:105031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA.. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010-2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80(19):1778–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smagula SF, Stone KL, Fabio A, Cauley JA.. Risk factors for sleep disturbances in older adults: Evidence from prospective studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;25:21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Redline S, Kirchner HL, Quan SF, Gottlieb DJ, Kapur V, Newman A.. The effects of age, sex, ethnicity, and sleep-disordered breathing on sleep architecture. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(4):406–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Phillips B, Young T, Finn L, Asher K, Hening WA, Purvis C.. Epidemiology of restless legs symptoms in adults. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2137–2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hoch CC, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, et al. Comparison of sleep-disordered breathing among healthy elderly in the seventh, eighth, and ninth decades of life. Sleep. 1990;13(6):502–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johnson DK, Storandt M, Morris JC, Galvin JE.. Longitudinal study of the transition from healthy aging to Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(10):1254–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scullin MK, Bliwise DL.. Sleep, cognition, and normal aging: Integrating a half century of multidisciplinary research. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(1):97–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ramos AR, Tarraf W, Wu B, et al. Sleep and neurocognitive decline in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(2):305–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Potvin O, Lorrain D, Forget H, et al. Sleep quality and 1-year incident cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults. Sleep. 2012;35(4):491–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xu L, Jiang CQ, Lam TH, et al. Short or long sleep duration is associated with memory impairment in older Chinese: The Guangzhou biobank cohort study. Sleep. 2011;34(5):575–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tworoger SS, Lee S, Schernhammer ES, Grodstein F.. The association of self-reported sleep duration, difficulty sleeping, and snoring with cognitive function in older women. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(1):41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Faubel R, López-García E, Guallar-Castillón P, Graciani A, Banegas JR, Rodríguez-Artalejo F.. Usual sleep duration and cognitive function in older adults in Spain. J Sleep Res. 2009;18(4):427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mohlenhoff BS, Insel PS, Mackin RS, et al. Total sleep time interacts with age to predict cognitive performance among adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(9):1587–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kronholm E, Sallinen M, Suutama T, Sulkava R, Era P, Partonen T.. Self-reported sleep duration and cognitive functioning in the general population. J Sleep Res. 2009;18(4):436–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ding G, Li J, Lian Z.. Both short and long sleep durations are associated with cognitive impairment among community-dwelling Chinese older adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(13):e19667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sabia S, Fayosse A, Dumurgier J, et al. Association of sleep duration in middle and old age with incidence of dementia. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koychev I, Vaci N, Bilgel M, et al. Prediction of rapid amyloid and phospotylated-Tau accumulation in cognitively healthy individuals. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12(1):e12019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu A, Sun Z, McDade EM, Hughes TF, Ganguli M, Chang CH.. Blood pressure and memory: Novel approaches to modeling nonlinear effects in longitudinal studies. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2019;33(4):291–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wu L, Sun D, Tan Y.. A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of sleep duration and the occurrence of cognitive disorders. Sleep Breath. 2018;22(3):805–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lo JC, Groeger JA, Cheng GH, Dijk DJ, Chee MW.. Self-reported sleep duration and cognitive performance in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2016;17:87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ju Y-E, McLeland JS, Toedebusch CD, et al. Sleep quality and preclinical Alzheimer's disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(5):587–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mander BA, Marks SM, Vogel JW, et al. β-amyloid deposition in the human brain disrupts NREM slow wave sleep and associated hippocampus-dependent long-term memory. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(7):1051–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lucey BP, McCullough A, Landsness EC, et al. Reduced non-rapid eye movement sleep is associated with tau pathology in early Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11(474):eaau6550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. . Taillard J, Sagaspe P, Berthomier C, et al. Non-REM sleep characteristics predict early cognitive impairment in an aging population. Front Neurol. 2019;10:197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Blackwell T, Yaffe K, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. ; for the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Group. Poor sleep is associated with impaired cognitive function in older women: The study of osteoporotic fractures. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(4):405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Diem SJ, Blackwell TL, Stone KL, et al. Measures of sleep-wake patterns and risk of mild cognitive impairment or dementia in older women. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(3):248–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Williams MM, Roe CM, Morris JC.. Stability of the clinical dementia rating, 1979-2007. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(6):773–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Donohue MC, Sperling RA, Salmon DP, et al. The preclinical Alzheimer cognitive composite: Measuring amyloid-related decline. JAMA Neurol. Aug 2014;71(8):961–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Toedebusch CD, McLeland JS, Schaibley CM, et al. Multi-modal home sleep monitoring in older adults. J Vis Exp. 2019;143:e58823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lucey BP, McLeland JS, Toedebusch CD, et al. Comparison of a single-channel EEG sleep study to polysomnography. J Sleep Res. 2016;25(6):625–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schindler SE, Gray JD, Gordon BA, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers measured by Elecsys assays compared to amyloid imaging. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(11):1460–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wood SN. Modelling and smoothing parameter estimation with multiple quadratic penalties. J R Statist Soc B. 2000;62(2):413–428. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wood SN. Generalized additive models: An introduction with R. 2nd ed.Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Riphagen JM, Schmiedek L, Gronenschild E, et al. Associations between pattern separation and hippocampal subfield structure and function vary along the lifespan: A 7 T imaging study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):7572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Foreman B, Albers D, Schmidt JM, et al. Intracortical electrophysiological correlates of blood flow after severe SAH: A multimodality monitoring study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38(3):506–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mala S, Potockova V, Hoskovcova L, et al. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy may play a role in pathogenesis of atherosclerosis in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;134:139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nedelska Z, Schwarz CG, Lesnick TG, et al. Association of longitudinal β-amyloid accumulation determined by positron emission tomography with clinical and cognitive decline in adults with probable Lewy body dementia. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1916439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jirsaraie RJ, Kaczkurkin AN, Rush S, et al. Accelerated cortical thinning within structural brain networks is associated with irritability in youth. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(13):2254–2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chiu HC, Lin YH, Lo MT, et al. Complexity of cardiac signals for predicting changes in alpha-waves after stress in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13315- [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fagan AM, Roe CM, Xiong C, Mintun MA, Morris JC, Holtzman DM.. Cerebrospinal fluid tau/beta-amyloid(42) ratio as a prediction of cognitive decline in nondemented older adults. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(3):343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chou CA, Toedebusch CD, Redrick T, et al. Comparison of single-channel EEG, actigraphy, and sleep diary in cognitively normal and mildly impaired older adults. Sleep Adv. 2020;1(1):zpaa006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fernandez-Mendoza J, He F, Calhoun SL, Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Bixler EO.. Objective short sleep duration increases the risk of all-cause mortality associated with possible vascular cognitive impairment. Sleep Health. 2020;6(1):71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Suh SW, Han JW, Lee JR, et al. Short average duration of NREM/REM cycle is related to cognitive decline in an elderly cohort: An exploratory investigation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;70(4):1123–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lutsey PL, Misialek JR, Mosley TH, et al. Sleep characteristics and risk of dementia and Alzheimer's disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(2):157–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Maestú F, de Haan W, Busche MA, DeFelipe J.. Neuronal Excitation/Inhibition imbalance: A core element of a translational perspective on Alzheimer pathophysiology. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;69:101372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Babiloni C, Arakaki X, Azami H, et al. Measures of resting state EEG rhythms for clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations of an expert panel. Alzheimers Dement. Published online 15 April 2021. doi:10.1002/alz.12311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pasquini L, Rahmani F, Maleki-Balajoo S, et al. Medial temporal lobe disconnection and hyperexcitability across Alzheimer's disease stages. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2019;3(1):103–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Babiloni C, Lizio R, Del Percio C, et al. Cortical sources of resting state EEG rhythms are sensitive to the progression of early stage Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34(4):1015–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gaubert S, Raimondo F, Houot M, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. EEG evidence of compensatory mechanisms in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2019;142(7):2096–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ranasinghe KG, Cha J, Iaccarino L, et al. Neurophysiological signatures in Alzheimer's disease are distinctly associated with TAU, amyloid-β accumulation, and cognitive decline. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12(534). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lam AD, Deck G, Goldman A, Eskandar EN, Noebels J, Cole AJ.. Silent hippocampal seizures and spikes identified by foramen ovale electrodes in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med. 2017;23(6):678–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Boly M, Jones B, Findlay G, et al. Altered sleep homeostasis correlates with cognitive impairment in patients with focal epilepsy. Brain. 2017;140(4):1026–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Valomon A, Riedner BA, Jones SG, et al. A high-density electroencephalography study reveals abnormal sleep homeostasis in patients with rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):4758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Helfrich RF, Mander BA, Jagust WJ, Knight RT, Walker MP.. Old brains come uncoupled in sleep: Slow wave-spindle synchrony, brain atrophy, and forgetting. Neuron. 2018;97(1):221–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Winer JR, Mander BA, Helfrich RF, et al. Sleep as a potential biomarker of tau and β-amyloid burden in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2019;39(32):6315–6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Insel PS, Weiner M, Mackin RS, et al. Determining clinically meaningful decline in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2019;93(4):e322–e333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mormino EC, Betensky RA, Hedden T, et al. Synergistic effect of β-amyloid and neurodegeneration on cognitive decline in clinically normal individuals. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(11):1379–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tranah GJ, Yaffe K, Nievergelt CM, et al. ; the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study (MrOS) Research Group. APOEε4 and slow wave sleep in older adults. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0191281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.