Abstract

TB PNA FISH is a new fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) method using peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probes for differentiation between species of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTC) and nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) in acid-fast bacillus-positive (AFB+) cultures is described. The test is based on fluorescein-labelled PNA probes that target the rRNA of MTC or NTM species applied to smears of AFB+ cultures for microscopic examination. Parallel testing with the two probes serves as an internal control for each sample such that a valid test result is based on one positive and one negative reaction. TB PNA FISH was evaluated with 30 AFB+ cultures from Denmark and 42 AFB+ cultures from Thailand. The MTC-specific PNA probe showed diagnostic sensitivities of 84 and 97%, respectively, and a diagnostic specificity of 100% in both studies, whereas the NTM-specific PNA probe showed diagnostic sensitivities of 91 and 64%, respectively, and a diagnostic specificity of 100% in both studies. The low sensitivity of the NTM-specific PNA probe in the Thai study was due to a relatively high prevalence of Mycobacterium fortuitum, which is not identified by the probe. In total, 63 (87%) of the cultures were correctly identified as MTC (n = 46) or NTM (n = 17), whereas the remaining 9 were negative with both probes and thus the results were inconclusive. None of the samples were incorrectly identified as MTC or NTM; thus, the predictive value of a valid test result obtained with TB PNA FISH was 100%.

Tuberculosis (TB) is caused by infection with species of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTC), in particular, M. tuberculosis, and is globally the most important cause of death from a single pathogen (11, 12). Laboratory diagnosis of TB relies on initial microscopic examination of sputum smears stained for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), the presence of which (AFB+) is the first indication of a possible M. tuberculosis infection (9). Patients with pulmonary TB in whom AFB are detected by sputum smear microscopy require priority attention and are immediately started on antituberculosis therapy (5). The final diagnosis of tuberculosis requires differentiation of species of MTC from nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM). Traditionally, this has been done by biochemical tests with cultures, which often take 4 to 6 weeks for a definitive identification. More recently, molecular technologies (8) have been implemented in an attempt to significantly shorten the identification time.

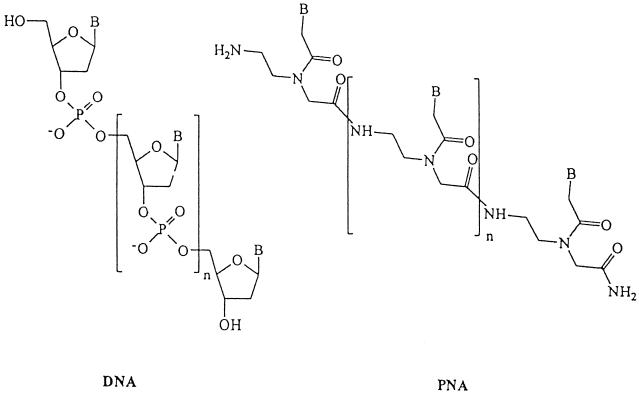

Peptide nucleic acid (PNA) molecules are pseudopeptides with DNA-binding capabilities. These compounds were first reported earlier in the 1990s in connection with a series of attempts to design nucleic acid analogues capable of hybridizing, in a sequence-specific fashion, to DNA and RNA (3, 4). In PNA, the counterpart of the sugar phosphate backbone of DNA and RNA is a polyamide formed by repetitive units of N-(2-aminoethyl) glycine. Bases are attached to this backbone to provide a molecular design that allows PNA to hybridize (e.g., by specific base pairing) to complementary DNA or RNA sequences. The structure of PNA is shown in Fig. 1. The relative hydrophobic character of PNA (7, 10) compared to that of DNA makes PNA probes able to diffuse through the hydrophobic cell wall of mycobacteria under conditions which do not lead to disruption of the bacterial morphology (15). DNA probes have been described for in situ detection of mycobacterium species but have never been applied in a practical diagnostic test (2, 16).

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of DNA and PNA. The PNAs consist of a polyamide backbone of N-(2-aminoethyl) glycine units to which nucleobases are covalently attached. B indicates a nucleobase (adenine, cytosine, guanine, or thymine).

This paper describes a new molecular method (TB PNA FISH) based on PNA probes for concomitant detection of MTC and NTM by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). The method combines the advantages of microscopy for derivation of morphological information with the target specificity provided by molecular technologies in a way which is easily adaptable to current microscopic techniques routinely used in the majority of clinical microbiological laboratories.

The PNA probes target selected regions of mycobacterial 16S rRNA sequences which allows distinction between MTC and NTM. Each mycobacterium cell contains, depending on the growth rate (6), hundreds to thousands of rRNA molecules (17), facilitating the detection of single cells by FISH with PNA probes for diagnosis of TB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical specimens.

A total of 30 consecutive AFB+ BACTEC 12B cultures from routine testing at the Department of Mycobacteriology, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark, were included in this study. In addition, 42 AFB+ samples from a total of 200 sputum specimens consecutively received at the Department of Pathology, Clinical Microbiology Division, Ramathibodi Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand, were included. These specimens were cultured on Löwenstein-Jensen slants.

Mycobacterium reference strains.

The Mycobacterium reference strains M. tuberculosis ATCC 25177, M. bovis BCG ATCC 35734, M. avium ATCC 25292, M. intracellulare ATCC 13950, M. scrofulaceum ATCC 19981, M. gordonae ATCC 14470, M. kansasii ATCC 12479, M. abscessus ATCC 19977, M. marinum ATCC 927, M. simiae ATCC 25275, M. szulgai ATCC 35799, M. flavescens ATCC 23033, M. fortuitum ATCC 43266, and M. xenopi ATCC 19250 were used, and all strains except M. marinum were grown in Dubos broth at 37°C; M. marinum was grown at 30°C. Each strain was tested at least twice.

Clinical isolates of respiratory bacteria.

Corynebacterium spp., Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Propionibacterium acnes, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Branhamella catarrhalis, Escherichia coli, Neisseria spp., Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, Enterobacter spp., Proteus mirabilis, Xanthomonas maltophilia, and Nocardia asteroides were grown on rich medium (blood agar, brain-heart blood agar, or chocolate agar). Two clinical isolates of each species were tested.

Selection of probe sequences.

Sequence processing was done with computer software from DNASTAR (Madison, Wis.). Alignments of mycobacterial 16S rRNA gene (rDNA) sequences were done with the Megalign (version 3.12) alignment tool. Up to 100 sequences were aligned at a time.

PNA probes were designed with due regard to secondary structures. Probe sequences were optimized in this respect with the PrimerSelect (version 3.04) program (DNASTAR). As a control for sequence specificity, all probe sequences were subsequently matched with sequences in the GenBank and EMBL databases by using BLAST (1) to detect sequence similarity; the search was performed at the National Center for Biotechnology Information web site (9a).

Synthesis of labelled PNA probes.

PNA probes were synthesized at DAKO A/S on an Expedite 8909 Nucleic Acid Synthesis System (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, Mass.). The PNA oligomers were terminated with either two β-alanine molecules or one lysine molecule, and before cleavage from the resin the oligomers were labelled with 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein at the β-amino group of β-alanine or the ɛ-amino group of lysine. The probes were purified by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography at 50°C and were characterized with a G 2025 A MALDI-TOF MA instrument (Hewlett-Packard, San Fernando, Calif.). The molecular weights that were determined were within 0.1% of the calculated molecular weights.

FISH.

Smears were prepared by standard procedures (9) and were stored at 4°C in foil bags with desiccants for a maximum of 2 months before use. Prior to hybridization, smears were immersed in 80% (vol/vol) ethanol for 15 min and were subsequently air dried. Two smears of each sample were covered with approximately 20 μl of the fluorescein-labelled MTC-specific PNA probe (100 nM) or the fluorescein-labelled NTM-specific PNA probe (25 nM) in a hybridization solution containing 10% (wt/vol) dextran sulfate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), 10 mM NaCl (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), 30% (vol/vol) formamide (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.), 0.1% (wt/vol) sodium pyrophosphate (Merck), 0.2% (wt/vol) polyvinylpyrrolidone (Sigma Chemical Co.), 0.2% (wt/vol) Ficoll (Sigma Chemical Co.), 5 mM disodium EDTA (Merck), 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany), and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). To avoid unspecific binding of the labelled PNA probes, 1 μM nonlabelled, nontarget PNA probe was included in the hybridization solution. Samples were covered with coverslips (No. 1; Menzel, Braunschweig, Germany) in order to ensure an even coverage of the smears with the hybridization solution and to minimize evaporation. Finally, the slides were placed in a moist chamber and were incubated for 1.5 h at 55°C. Prior to use, the equipment and solutions that were used were treated so as to be RNase free (14).

Following hybridization, the coverslips were removed and the slides were submerged in freshly prepared, prewarmed 5 mM Tris–15 mM NaCl–0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (pH 10) in a water bath at 55°C and washed for 30 min. Subsequently, the slides were washed and cooled to room temperature by brief immersion in H2O and were air dried.

The smears were finally mounted with 1 drop of IMAGEN Mounting Fluid (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), covered with coverslips (No. 1; Menzel), and incubated for 30 min at 55°C. The slides were stored for a maximum of 2 weeks before microscopy.

Microscopic examinations were conducted with a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a ×100/1.30 oil immersion objective (Leica), an HBO 100-W bulb, and an FITC/Texas Red dual-band filter set (Chroma Technology Corp., Brattleboro, Vt.). Mycobacteria were detected on the basis of bright fluorescence and morphology (1- to 10-μm slender, rod-shaped bacilli). Mycobacteria of the NTM group may also appear to be pleomorphic, ranging in appearance from long rods to coccoid forms.

Smears of cultures from clinical specimens were prepared at Statens Serum Institut and Ramathibodi Hospital. Each culture was tested once. FISH and microscopic examinations were carried out at DAKO A/S, and FISH with smears of cultures of clinical respiratory isolates was carried out at Ramathibodi Hospital.

Interpretation of test results.

By using the two PNA probes in parallel hybridization reactions, the identification of the analyzed sample as MTC or NTM positive is recognized as a positive reaction with one probe and a negative reaction with the other probe. The results for double-negative samples as well as double-positive samples are inconclusive and should be reported as “not identified.” Thus, the final outcome of the test is reported as either MTC positive, NTM positive, or not identified.

Controls.

Smears of M. tuberculosis or M. bovis and of M. avium or M. kansasii grown in Dubos medium were included in every assay run as controls.

Identification of mycobacteria.

The AccuProbe Mycobacterium identification kits (Gen-Probe, San Diego, Calif.) were used for identification of MTC and NTM at the Department of Mycobacteriology, Statens Serum Institut. One isolate was identified by amplification of gene fragments coding for 16S rRNA and direct sequencing of the amplified DNA fragments (13).

Niacin strips (Difco) were used for the identification of M. tuberculosis at the Department of Pathology, Ramathibodi Hospital. M. fortuitum isolates were identified by biochemical analysis, including assays for arylsulfatase, nitrate reduction, and iron uptake.

RESULTS

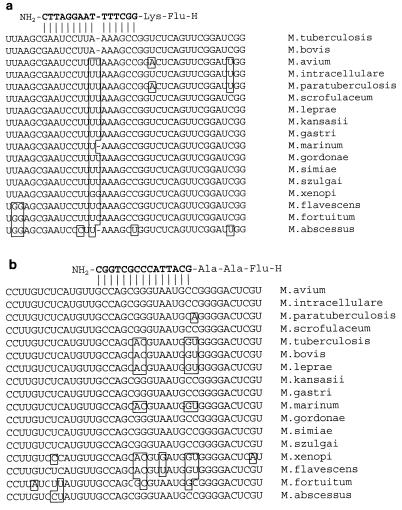

Published sequences of 16S rDNA from mycobacterium species were aligned in order to identify species-specific regions. An rDNA sequence distinctive for M. tuberculosis and M. bovis, both members of MTC, as well as an rDNA sequence distinctive for the majority of clinically relevant NTM species, were identified as described in Materials and Methods. Figures 2a and b show the alignments of sequences of representative species in the selected regions.

FIG. 2.

(a) Alignment of partial mycobacterium 16S rRNA sequences from the indicated species. The sequence of M. tuberculosis rRNA included in the figure corresponds to positions 1224 to 1262 of GenBank accession no. X52917. Above the alignments the antiparallel hybridization of the MTC-specific PNA probe is shown. (b) Alignment of partial mycobacterium 16S rRNA sequences from the indicated species. The sequence of M. avium corresponds to positions 1099 to 1138 of GenBank accession no. M61673. Above the alignments the antiparallel hybridization of the NTM-specific PNA probe is shown.

The search with BLAST did not detect any other bacterial rDNA sequences with a 100% match to the sequence of the MTC-specific probe, but it revealed a 100% complementarity of the NTM-specific probe to the rDNAs of species of Actinomyces and Rickettsia as well as some species with neither phylogenetic nor clinical relevance, including Nitrospina gracilis and Shewanella alga.

The specificities of the PNA probes were tested by FISH with reference strains selected as phylogenetic representatives of the Mycobacterium genus and to cover the clinically most relevant species. The results shown in Table 1 are in agreement with the sequence data presented in Fig. 2. As predicted, the MTC-specific PNA probe does not cross-hybridize to rRNA of any of the NTM species tested, the only exception being a very weak cross-hybridization to M. marinum. The cross-hybridization is seen as a faint fluorescence in a few percent of the cells. As shown in the alignment in Fig. 2, there is only a single mismatch between the 16S rRNA sequence of M. marinum and the MTC-specific PNA probe. The NTM-specific PNA probe detected all mycobacterium species with complementary rRNA sequences tested, e.g., M. intracellulare, M. avium, M. kansasii, M. scrofulaceum, M. gordonae, M. abscessus, M. simiae, and M. szulgai, but not M. tuberculosis and M. bovis or M. fortuitum, M. flavescens, M. marinum, and M. xenopi, all of which have more than one mismatch in their rRNAs compared to the sequence of the NTM-specific PNA probe.

TABLE 1.

Results for control smears analyzed by FISH with MTC-specific and NTM-specific PNA probes

| Species | Result with the following probea:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| MTC-specific PNA probe | NTM-specific PNA probe | |

| M. tuberculosis | Pos. | Neg. |

| M. bovis | Pos. | Neg. |

| M. avium | Neg. | Pos. |

| M. intracellulare | Neg. | Pos. |

| M. scrofulaceum | Neg. | Pos. |

| M. gordonae | Neg. | Pos. |

| M. kansasii | Neg. | Pos. |

| M. abscessus | Neg. | Pos. |

| M. marinum | (Neg.) | Neg. |

| M. simiae | Neg. | Pos. |

| M. szulgai | Neg. | Pos. |

| M. flavescens | Neg. | Neg. |

| M. fortuitum | Neg. | Neg. |

| M. xenopi | Neg. | Neg. |

Pos., positive; Neg., negative. Parentheses indicate that very few bacteria with weak fluorescence were detected.

The specificities of the two probes were further examined by FISH with smears of clinical isolates representing a range of respiratory bacteria. FISH was performed as described in Materials and Methods, with the modification that a Zeiss Axioscope fluorescence microscope equipped with a 50-W HBO lamp and a standard fluorescein isothiocyanate filter was used. In addition, both probes were tested in a concentration of 1 μM and without the addition of nonlabelled, nontarget PNA probe to the hybridization solution. As shown in Table 2, no cross-hybridization to any of the species was found.

TABLE 2.

Cross-reactivity of the MTC-specific PNA probe and the NTM-specific PNA probe to clinically relevant respiratory bacteria as determined by a BLAST search and FISH

| Organism | Result with the following probe by the indicated methoda:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTC-specific PNA probe

|

NTM-specific PNA probe

|

|||

| BLAST search | FISH | BLAST search | FISH | |

| Corynebacterium spp. | − | − | − | − |

| Haemophilus influenzae | − | − | − | − |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | − | − | − | − |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | − | − | − | − |

| Propionibacterium acnes | − | − | − | − |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | − | − | − | − |

| Staphylococcus aureus | − | − | − | − |

| Branhamella catarrhalis | − | − | − | − |

| Escherichia coli | − | − | − | − |

| Neisseria spp. | − | − | − | − |

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus | − | − | − | − |

| Enterobacter spp. | NA | − | NA | − |

| Proteus mirabilis | NA | − | NA | − |

| Xanthomonas maltophilia | NA | − | NA | − |

| Nocardia asteroides | − | − | − | − |

−, negative result; NA, sequence not available.

Finally, the diagnostic applicability of TB PNA FISH for differentiation between MTC and NTM species in smears of AFB+ cultures was evaluated with clinical samples in two separate studies in Denmark and Thailand. The two sites were chosen to cover geographic areas with different prevalences of TB.

In the Danish study, results obtained with 30 AFB+ BACTEC 12B cultures were compared with the results obtained by tests with AccuProbe (Table 3). Sixteen samples were identified as MTC and 10 samples were identified as NTM by TB PNA FISH (Table 3). All results were in agreement with the species identification results obtained by the reference methods. Four samples were negative with both PNA probes and thus were reported as not identified. Subsequent Ziehl-Neelsen staining of these smears revealed that smears of three of the four samples contained only sparse amounts of material. The reference methods showed that the 30 AFB+ BACTEC 12B cultures were divided into 19 MTC cultures and 11 NTM cultures. The performance specifications for each of the two probes and for the TB PNA FISH test are presented in Table 4.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of results of TB PNA FISH and results of test with AccuProbe in the Danish study with 30 AFB+ cultures from BACTEC 12B medium

| AccuProbe result | No. of cultures with the following TB PNA FISH result:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MTC | NTM | Not identified | |

| MTC | 16 | 0 | 3a |

| MAC | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| M. gordonae | 0 | 7 | 1b |

| Not identified | 0 | 1c | 0 |

On subsequent Ziehl-Neelsen staining, the result was ≤1+.

On subsequent Ziehl-Neelsen staining, the result was 3+.

The organism was M. abscessus, which was identified as described in Materials and Methods.

TABLE 4.

Performance specifications for MTC-specific PNA probe, NTM-specific PNA probe, and TB PNA FISH from the Danish study

| Probe or test | Diagnostic specificity (%) | Diagnostic sensitivity (%) | Inconclusive results (%) | Positive predictive value (%) | Negative predictive value (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTC-specific PNA probe | 100 (11/11)a | 84 (16/19) | 16 (3/19) | 100 (16/16) | 79 (11/14) |

| NTM-specific PNA probe | 100 (19/19) | 91 (10/11) | 9 (1/11) | 100 (10/10) | 95 (19/20) |

| TB PNA FISH | —b | 87 (26/30) | 13 (4/30) | 100 (26/26) | —c |

Values in parentheses are number of correct results/total number of cultures tested.

—, no negative samples were available for assessment of the diagnostic specificity of TB PNA FISH because all samples were mycobacterium positive.

—, TB PNA FISH results cannot be negative according to the definition (see interpretation of test results in Materials and Methods).

In the Thai study, 30 samples were identified as MTC and 7 samples were identified as NTM by TB PNA FISH, and all of these results were in agreement with those of the niacin strip test (Table 5). Five samples were double negative by TB PNA FISH and were reported as not identified. Subsequent Ziehl-Neelsen staining of smears of these samples showed that one sample did not contain mycobacteria in the smears. The remaining four samples had plenty of AFB+ bacteria on the smears. They were negative by the AccuProbe MTC test and were subsequently identified as M. fortuitum by biochemical tests. After resolution of these discrepant results, the 42 AFB+ Löwenstein-Jensen cultures could be divided into 31 MTC-positive cultures and 11 NTM-positive cultures, and the results were used for calculation of the performance specifications for each of the two PNA probes as well as for the combined TB PNA FISH test. The performance specifications are presented in Table 6.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of results of TB PNA FISH and tests with niacin strips from the Thai study with 42 AFB+ cultures from Löwenstein-Jensen slants

| Niacin strip test resulta | No. of cultures with the following TB PNA FISH result:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MTB | NTM | Not identified | |

| Pos. (TB) | 30 | 0 | 1b |

| Neg. (not TB) | 0 | 7 | 4c |

Pos., positive; Neg., negative.

On subsequent Ziehl-Neelsen staining, the result was ≤1+.

The organism was M. fortuitum according to biochemical analysis.

TABLE 6.

Performance specifications for MTC-specific PNA probe, NTM-specific PNA probe, and TB PNA FISH from the Thai study

| Probe or test | Diagnostic specificity (%) | Diagnostic sensitivity (%) | Inconclusive results (%) | Positive predictive value (%) | Negative predictive value (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTC-specific PNA probe | 100 (11/11)a | 97 (30/31) | 3 (1/31) | 100 (30/30) | 92 (11/12) |

| NTM-specific PNA probe | 100 (31/31) | 64 (7/11) | 36 (4/11) | 100 (7/7) | 89 (31/35) |

| TB PNA FISH | —b | 88 (37/42) | 12 (5/42) | 100 (37/37) | —c |

Values in parentheses are number of correct results/total number of cultures tested.

—, no negative samples were available for assessment of the diagnostic specificity of TB PNA FISH because all samples were mycobacterium positive.

—, TB PNA FISH test results cannot be negative according to the definition (see interpretation of test results in Materials and Methods).

In summary, differentiation between MTC and NTM by TB PNA FISH was conducted with a predictive value of 100% for 63 of 72 samples, all of which gave a conclusive test result, whereas the results obtained with the remaining 9 samples (12.5%) were inconclusive.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that the MTC- and NTM-specific PNA probes used in this study for FISH are well-suited for differentiation between MTC and NTM species in smears of AFB+ cultures. The use of probes that target rRNA makes direct detection of single cells possible without amplification. This new diagnostic method provides a positive predictive value of 100%.

The two PNA probes used in the study provide internal controls so that only a combination of a positive result with one probe and a negative result with the other probe leads to a definite test result. False-positive test results are thus unlikely to occur, because both probes should give false reactions (one false negative and one false positive). In contrast, the majority of biochemical and molecular methods are “single-analyte” tests, which often require separate control samples and/or other methods to validate the test result. Usually, several individual tests are performed (either in parallel or sequentially in order to reduce the cost) before the clinician is provided with the result.

Besides the high degree of specificity offered by each of the PNA probes, the TB PNA FISH method has the advantages and the simplicity associated with microscopy, in which the morphology of the mycobacteria is further displayed. The test may also be used with less advanced laboratory facilities, provided that a fluorescence microscope and an incubator are available. Thus, this new test may allow clinical microbiology laboratories in developing countries to benefit from the advantages of molecular technologies for the swift differentiation between MTC and NTM. The very weak cross-hybridization with M. marinum is not expected to cause any diagnostic problems because (i) the very low fluorescence intensity and small number of bacteria detected with the MTC-specific PNA probe are not likely to be interpreted as positive reactions, (ii) M. marinum does not grow optimally at 37°C, and (iii) M. marinum is a skin pathogen, not a respiratory pathogen.

In both studies reported here, a small proportion of double-negative results, i.e., negative with both the MTC-specific and the NTM-specific PNA probes, was found. This may happen in cases in which smears contain only a small amount of material, as was seen for approximately 10% of the samples, or may be due to a less than 100% sensitivity, e.g., as in the case of one isolate of M. gordonae, which was not identified with the NTM-specific PNA probe in the Danish study. False-negative results will also occur for a few NTM species, e.g., M. xenopi, M. fortuitum, and M. flavescens, which are not identified with the NTM-specific PNA probe, as seen in the Thai study. Lack of hybridization to M. fortuitum may pose a problem in regions where this species is common. It is, however, important to stress that double-negative reactions will be reported as the inconclusive test result “not identified” and will indicate that further analyses by other methods are required.

Double-positive reactions are also inconclusive and are reported accordingly. However, double-positive reactions may be caused by mixed cultures. Confirmatory testing is then required, but microscopic examination of the TB PNA FISH result may be indicative of mixed cultures on the basis of differences in the morphologies of the mycobacteria detected with the MTC-specific probe and the NTM-specific probe. Background artifacts are seen only rarely and can be easily distinguished from true-positive signals on the basis of differences in structure.

The only DNA probe-based test for the identification of MTC which is commercially available is the AccuProbe Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex culture identification test. Both the TB PNA FISH test and the AccuProbe test have very high specificities. The prime advantages of the TB PNA FISH test are as follows. (i) Standard equipment available in most mycobacteriological laboratories is used. There is no need for specialized equipment such as a sonicator and a luminometer, which are required for the AccuProbe test. The only special requirement for the TB PNA FISH test is the dual-band filter on the fluorescence microscope. (ii) The combined use of the MTC-specific and the NTM-specific probes within one TB PNA FISH test gives a result regarding not only the MTC infection status but also the NTM infection status. (iii) The combined use of the MTC-specific and the NTM-specific probes provides internal controls for the probes, thus reducing the need for the inclusion of positive and negative controls in parallel in each run. (iv) The combined use of the two probes further ensures a very high positive predictive value of the TB PNA FISH assay. (v) Double infections with MTC and NTM species will be identified as double-positive results by the TB PNA FISH test. This is not assessed by single AccuProbe tests. (vi) The microscopic analysis of the TB PNA FISH test permits the use of morphology as an additional identification tool. This may support each individual analysis and is primarily of importance as an aid in the presumptive identification of NTM-positive reactions as well as in the case of analyses of double-positive results. (vii) The TB PNA FISH test is very simple to perform.

The prime disadvantage of the TB PNA FISH test, except for the need for a dual-band filter on the fluorescence microscope, is that the test may give rise to a few percent samples with double-negative results because the NTM probe does not hybridize to all NTM species. The actual percentage will depend on the region of the world from where the samples were derived.

A palette of PNA probes that target distinctive mycobacterium species in order to provide a system for subsequent identification of NTM species may supplement the test described here. Furthermore, PNA probes that target different species may be labelled with different fluorescent dyes, allowing differentiation by dual fluorescence on a single smear. The test is being optimized for differentiation between MTC and NTM directly with AFB+ sputum smears for the rapid diagnosis of TB.

In conclusion, the new molecular method for the laboratory diagnosis of TB is easily adaptable to current microscopic techniques routinely used in the majority of clinical microbiology laboratories, initially as an AFB+ culture identification method and, in the future, most likely as an AFB+ sputum identification method. FISH with specific PNA probes may thus, in future, become an invaluable method for the diagnosis of TB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The excellent technical assistance of Jani Hagemann, Ulla Søborg Larsen, Yrsa Pedersen, and Somjai Mateeyonpiriya is greatly acknowledged. Anne M. Maarbjerg is acknowledged for the synthesis of the PNA probes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnoldi J, Schlüter C, Duchrow M, Hübner L, Ernst M, Teske A, Flad H-D, Gerdes J, Böttger E C. Species-specific assessment of Mycobacterium leprae in skin biopsies by in-situ hybridization and polymerase chain reaction. Lab Invest. 1992;66:618–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchardt O, Egholm M, Nielsen P E, Berg R H. The use of nucleic acid analogues in diagnostics and analytical procedures. November 1992. PCT patent application WO 92/20703. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchardt O, Egholm M, Nielsen P E, Berg R H. Peptide nucleic acids. November 1992. PCT patent application WO 92/20702. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Initial therapy for tuberculosis in the era of multidrug resistance—recommendation of the Advisory Council for the Elimination of Tuberculosis. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1993;42(RR-7):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delong E F, Wickman G S, Pace N R. Phylogenetic strains: ribosomal RNA-based probes for the identification of single cells. Science. 1989;243:1360–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.2466341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egholm M, Buchardt O, Christensen L, Behrens C, Freier S M, Driver D A, Berg R H, Kim S K, Norden B, Nielsen P E. PNA hybridizes to complementary oligonucleotides obeying the Watson-Crick hydrogen-bonding rules. Nature. 1993;365:566–568. doi: 10.1038/365566a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heifets L. Mycobacteriology laboratory. Clin Chest Med. 1997;18:35–53. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kent P T, Kubica G P. Public health mycobacteriology. A guide for level III laboratories. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 9a.National Center for Biotechnology Information. Advanced BLAST (BLASTN 1.4.11). [Online.] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/blast.cgi?Jform=1. December 1998, last date accessed.

- 10.Nielsen P E, Egholm M, Berg R H, Buchardt O. Sequence-selective recognition of DNA by strand displacement with a thymine-substituted polyamide. Science. 1991;254:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1962210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raviglione M C, Speider D E, Kochi A. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis, morbidity, and mortality of a worldwide epidemic. JAMA. 1995;273:220–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reichman L B. Tuberculosis elimination—what’s to stop us? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1997;1:3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogall T, Wolters J, Flohr T, Böttger E C. Towards a phylogeny and definition of species at the molecular level within the genus Mycobacterium. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1990;40:323–330. doi: 10.1099/00207713-40-4-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stender, H., T. A. Mollerup, K. Lund, K. H. Petersen, P. Hongmanee, and S. E. Godtfredsen. Direct detection and identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in smear-positive sputum samples by fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) using peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probes. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis., in press. [PubMed]

- 16.Thompson C T. Detection of mycobacteria. December 1996. U.S. patent 5,582,985. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winder F G. Mode of action of the antimycobacterial agents and associated aspects of the molecular biology of mycobacteria. In: Ratledge C, Stanford J, editors. The biology of the mycobacteria. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1982. pp. 353–438. [Google Scholar]