Abstract

Background

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is characterized by the inability to control opioid use despite attempts to stop use and negative consequences to oneself and others. The burden of opioid misuse and OUD is a national crisis in the United States with substantial public health, social, and economic implications. Although medication-assisted treatment (MAT) has demonstrated efficacy in the management of OUD, access to effective counseling and psychosocial support is a limiting factor and a significant problem for many patients and physicians. Digital therapeutics are an innovative class of interventions that help prevent, manage, or treat diseases by delivering therapy using software programs. These applications can circumvent barriers to uptake, improve treatment adherence, and enable broad delivery of evidence-based management strategies to meet service gaps. However, few digital therapeutics specifically targeting OUD are available, and additional options are needed.

Objective

To this end, we describe the development of the novel digital therapeutic MODIA.

Methods

MODIA was developed by an international, multidisciplinary team that aims to provide effective, accessible, and sustainable management for patients with OUD. Although MODIA is aligned with principles of cognitive behavioral therapy, it was not designed to present any 1 specific treatment and uses a broad range of evidence-based behavior change techniques drawn from cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness, acceptance and commitment therapy, and motivational interviewing.

Results

MODIA uses proprietary software that dynamically tailors content to the users’ responses. The MODIA program comprises 24 modules or “chats” that patients are instructed to work through independently. Patient responses dictate subsequent content, creating a “simulated dialogue” experience between the patient and program. MODIA also includes brief motivational text messages that are sent regularly to prompt patients to use the program and help them transfer therapeutic techniques into their daily routines. Thus, MODIA offers individuals with OUD a custom-tailored, interactive digital psychotherapy intervention that maximizes the personal relevance and emotional impact of the interaction.

Conclusions

As part of a clinician-supervised MAT program, MODIA will allow more patients to begin psychotherapy concurrently with opioid maintenance treatment. We expect access to MODIA will improve the OUD management experience and provide sustainable positive outcomes for patients.

Keywords: MODIA, opioid use disorder, digital therapeutic, cognitive behavioral therapy, medication-assisted treatment, Broca

Introduction

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is characterized by loss of control of opioid use; recurrent opioid use despite efforts to cut down and despite having persistent physical, psychological, social, or interpersonal problems associated with opioid use; impaired social functioning; craving; tolerance; and withdrawal [1]. Despite attempts in recent years to combat the situation in the United States, the burden of opioid misuse and OUD is a national crisis with substantial public health, social, and economic implications [2]. A 2019 report from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration found that in the past year, 9.5 million American adults misused opioids [3]. The same report found that 1.5 million American adults had OUD in the past year [3]. The opioid crisis has led to significant loss of life, with 63%-82% of drug overdose deaths involving 1 or more opioids [4-6]. Drug overdose deaths involving prescription opioids have risen steadily over the past 2 decades, reaching 17,029 in 2017 [7]. Meanwhile, deaths from nonprescription synthetic opioids such as fentanyl have increased exponentially in recent years, from fewer than 5000 in 2013 to 28,466 in 2017 [7]. The opioid crisis also comes with debilitating financial costs. In 2015, the overall economic burden of the opioid crisis was estimated to be US $504 billion [4].

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is the current standard treatment for opioid addiction and involves the use of medications, in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies, to provide a “whole-patient” approach to the treatment of OUD [8]. MAT has been demonstrated to reduce illicit opioid use and opioid craving, improve treatment retention, and help sustain recovery [9-11]. One modality of therapy used in the MAT population is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), an evidenced-based type of psychotherapy built on the idea that cognitions (eg, thoughts, beliefs, and schemas) and behaviors play a central role in the etiology and maintenance of psychopathology [12]. CBT is considered an evidenced-based approach for the treatment of many psychiatric conditions [12] and has demonstrated added benefit when combined with OUD pharmacotherapies [13-17]. In addition, CBT alone has demonstrated preliminary efficacy in relation to other forms of drug counseling and psychosocial support in patients with OUD [18,19]. Multiple OUD medications—namely methadone, extended-release naltrexone, buprenorphine monotherapy, and buprenorphine/naloxone combination product—are available as part of an MAT program. These drugs are indicated for use as part of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes counseling conducted by a mental health professional and psychosocial support [20-25].

Despite these indications and the demonstrated efficacy of MAT, access to effective counseling, psychotherapy, and psychosocial support is a limiting factor in the treatment of OUD and a significant problem for many patients and physicians. There are an insufficient number of addiction psychiatrists and counselors in the United States, and many clinicians lack the proper training to provide adequate, evidence-based counseling or psychotherapy such as CBT for patients with OUD [26,27]. In a survey of physicians actively prescribing buprenorphine, 93% thought most patients would benefit from counseling, but only 36% reported an adequate number of counselors in their area [28]. Medical providers also lack the financial incentives and training to deliver and coordinate psychological interventions. Current reimbursement models are disproportionately focused on the pharmacotherapy aspect of OUD treatment, with the behavioral component significantly underfunded [29]. Moreover, many reimbursement models do not support care coordination and psychosocial services, and development of models to support MAT delivery are needed [30].

The shortage of counselors likely translates to deficits in psychological intervention because in a survey of 400 patients who were taking buprenorphine, 41% reported not receiving counseling in their first 30 days of treatment [31]. The limited access and use of psychological interventions are likely to continue in the future. Under one scenario analyzed by the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, multiple provider types, including psychiatrists and substance abuse and behavioral disorder counselors, are predicting a shortage of more than 10,000 full-time equivalent positions by 2025 [32].

In addition to the limited availability of effective counseling services, attitudinal barriers such as stigma can also prevent individuals from seeking or receiving counseling or psychotherapy [33-35]. Patients often worry about how their doctor will react to a disclosure of substance use and potential consequences of having this information in their medical records [34]. These concerns appear somewhat warranted because negative attitudes toward patients with OUD among providers limit access to treatment, harm reduction services, and may lead to the receipt of suboptimal care [33]. Logistical issues, such as busy lifestyles and difficulty traveling, can also complicate access to counseling and prescriptions [36]. Furthermore, barriers to MAT are exacerbated for vulnerable populations, including older people, racial minorities, people who live in rural communities, and those who are homeless, unemployed, or require payment assistance for treatment [33,36-38].

The opioid crisis has placed an enormous burden on the US health care system and has prompted significant support for new and innovative treatment alternatives. One such alternative is digital therapeutics (also discussed under labels such as internet-based interventions, web-based self-help, web-based psychological intervention, and computerized or electronic CBT, among others), an innovative new category of medical mobile apps that help prevent, manage, or treat diseases by delivering therapy through the use of software programs [39]. Digital therapeutics can circumvent barriers to uptake, improve treatment adherence, and enable broad delivery of evidence-based management strategies to meet service gaps [40,41]. Digital therapeutics have been shown to be effective across a broad range of psychiatric conditions, including depression, anxiety, and addictive disorders [42-45]. However, few digital therapeutics have thus far specifically targeted OUD.

A notable digital therapeutics platform for OUD that has been described in the literature is reSET-O, a prescription CBT digital therapeutic intended to be used as an adjunct to outpatient buprenorphine treatment that encompasses contingency management (CM). In an unblinded, controlled clinical trial, addition of reSET-O significantly increased retention in a 12-week treatment program. Although patients were generally compliant with the program, addition of reSET-O did not decrease illicit drug use in comparison with buprenorphine plus CM alone [44]. reSET-O was cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2018 [46] for use by patients who are currently under the supervision of a clinician as an adjunct to outpatient treatment that includes transmucosal buprenorphine and CM, validating the potential of digital therapeutics for OUD [47].

Because there is only 1 FDA-cleared digital therapeutic for OUD currently on the market, additional options are needed, especially those that maximize the personal relevance and emotional impact of the interaction to potentially increase learning effects and enhance overall treatment effectiveness. Multiple studies suggest that individually tailored digital interventions tend to be more effective than their nontailored counterparts, possibly because tailoring increases perceived personal relevance, which then leads to more elaborated cognitive processing and greater therapeutic impact [48-50]. MODIA is a novel digital therapeutic that aims to engage patients with OUD in a series of “simulated dialogues” in which a broad range of CBT skills and exercises are conveyed and practiced. The program is designed to tailor the content and style of these CBT skills, as described below, to maximize the relevance to individual patients’ needs and preferences. Here, we describe the development of MODIA with the aim of providing effective, accessible, and sustainable management for patients with OUD.

Methods

MODIA is a digital therapeutic for the treatment of OUD, which is rooted in evidence-based treatment techniques that are consistent with a CBT framework. It is intended to be used as part of a clinician-supervised MAT program. MODIA tailors content to the individual user, providing a personalized and interactive psychotherapy intervention that engages end users in CBT exercises and aims to empower them with skills to cope with cravings, withdrawal symptoms, potential trigger situations, and emotional symptoms accompanying OUD (eg, anxiety and depression). MODIA also allows users to develop a customized relapse prevention plan that encompasses risk behaviors, triggers, cravings, and coping strategies on the basis of patient inputs collected throughout the module exercises.

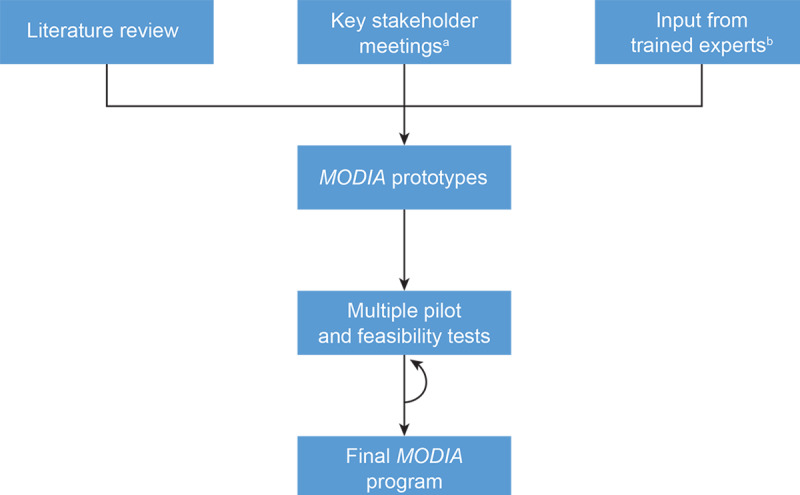

MODIA was developed by a multidisciplinary, international development team associated with GAIA AG in Hamburg, Germany. The development process followed a framework developed by GAIA over the course of more than a decade and is generally consistent with models such as the patient-focused, person-centered approach described by Yardley et al [51-54]. The MODIA development team included several licensed clinical psychologists and CBT therapists, software engineers, creative writers, graphic artists, and professional speakers. Prior to the development of the program, relevant treatment manuals, intervention descriptions, guidelines, patient reports, and trial results were reviewed by the development team (Figure 1). Several members of the development team (including BM and GU) also met in person on several occasions with experienced physicians, OUD treatment specialists, and patients at various stages of recovery. Some of these meetings took place in areas that are most severely affected by the current opioid crisis, including the Kensington neighborhood in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In the spirit of participant observation [55], members of the development team also attended a Narcotics Anonymous meeting in this neighborhood and had informal conversations with a variety of patients and MAT providers. Throughout the development process, several small pilot and feasibility evaluations were conducted with prototypes of the program, and results were used to refine and improve the program. Because these evaluations were part of the commercial product development process rather than academic studies, their specific results are not reported here; however, brief summaries are available upon request from the authors. On the basis of the findings of the development team, a broad range of behavior change techniques were incorporated into MODIA and are described in Table 1 [56].

Figure 1.

MODIA Development Process (September 2019 to January 2021). a: Key stakeholders included experienced physicians, OUD treatment specialists, and patients at various stages of recovery. b: Trained experts included clinical psychologists, CBT therapists, software engineers, experienced physicians, and OUD treatment specialists. OUD, opioid use disorder; CBT cognitive behavioral therapy.

Table 1.

Behavior change techniques included in MODIA.

| Technique | Representative examples |

| Action planning and mental contrasting |

|

| Avoidance |

|

| Behavioral substitution |

|

| Credible source |

|

| Decisional balance exercises |

|

| Direct therapeutic advice |

|

| Functional analysis |

|

| Goal setting and progress review |

|

| Homework |

|

| Humor |

|

| Mental imagery |

|

| Metaphors and images |

|

| Problem solving |

|

| Psychoeducation |

|

| Reward |

|

| Simulated role-plays |

|

| Self-monitoring and feedback |

|

| Self-talk |

|

| Storytelling |

|

| Therapeutic writing |

|

| Validation |

|

Results

MODIA uses proprietary software technology (Broca) that dynamically tailors content to the users’ responses. This software is the basis for several other digital therapeutic programs developed by this group and has been shown to be effective in multiple clinical trials [42,52-54,57-59]. Broca-based programs utilize an interactive approach in which the patient selects at least 1 option from predetermined menus within the program. Patients’ responses dictate what content is subsequently presented, creating a “simulated dialogue” experience between the patient and program. On the basis of patients’ responses, various aspects of the intervention are customized to match individual needs and preferences; for example, content is conveyed in either a more empathic/warmer style or a more directive/irreverent style; patients can choose to skip certain sections or case examples; and they are offered brief exercises relevant to their situation (eg, a brief exercise on coping with shame is offered only to patients who indicate that they have felt a sense of shame and would like to learn how to cope with it). MODIA uses simple, colloquial language to enhance user engagement. The purpose of presenting therapeutic content in an informal, dialogical fashion is to simulate key characteristics of human therapeutic interactions, such as responsiveness to patient requirements, personal relevance, empathy, and the therapeutic alliance. Consistent with this approach, evidence has shown that the quality of the therapeutic alliance with a Broca-based digital therapeutic predicts therapeutic improvement [60] and that individually tailored digital interventions tend to outperform their nontailored counterparts [49].

Before using MODIA, patients receive a 12-digit personal registration code. After entering this code and accepting the program’s terms and conditions, patients are asked to enter their email and set a password, which they can use to access the program for 180 days on any suitable device, including smartphones and desktop, laptop, or tablet computers. The MODIA program comprises 24 modules or “chats.” The term “chat” is used to be consistent with the idea that the program engages in a simulated therapeutic dialogue with the patient, which is a central metaphor guiding the patient’s experience. Patients are instructed to work independently by completing 1 to 2 chats per week. Each chat can be completed in approximately 15 to 30 minutes, depending on factors such as reading speed, selection of optional audio recordings, and individual response options or paths through the program. In addition to these chats, MODIA also includes brief motivational text messages that are sent regularly to prompt patients to use the program and help them transfer therapeutic techniques into their daily routines. Screenshots that convey the look and feel of MODIA are shown in Figures 2-6.

Figure 2.

MODIA screenshot 1.

Figure 6.

MODIA screenshot 5.

The chats are grouped into 4 clusters. Table 2 shows the chat topics, goals, and content outlines for clusters 1 and 2 as examples of the content found within a cluster; content outlines for all 4 clusters are presented in Multimedia Appendix 1. In brief, the first cluster is “Basic Techniques and Principles,” in which patients are oriented to the program, learn about the neurobiology of opioid dependence, and acquire basic CBT skills. In the “Learning Psychological Flexibility Skills” cluster, patients are taught 6 core skills to increase “psychological flexibility” or the capacity to tolerate distress [61,62]. In the third cluster, “Applying Therapeutic Skills to Important Life Domains,” patients learn to apply the techniques they have learned to various relevant life domains such as interpersonal relationships, coping with depression or anxiety/worries, anger management, and insomnia. Finally, the “Facilitating Personal Growth and Development: Solidifying Your Healthy Self-Identity” cluster emphasizes the strengths, talents, and personal resources of the patient. Patients are taught to practice compassion, engage in exercises that build self-esteem and confidence, discover personal strengths, and cope successfully with slips and relapses. Building life skills such as these can help patients manage stressful situations and environmental cues that may trigger cravings and relapse. Furthermore, skills that patients develop through CBT are likely to remain even after treatment has ceased [63]. Patient-friendly language (ie, lay terms rather than medical jargon) is used in the program to describe the clusters and chats.

Table 2.

Content outline of MODIA clusters 1 and 2.

| Topic (chat title)a | Main goal of the chat | Content outlineb | |||

|

Cluster 1: “Basic techniques and principles”

| |||||

|

|

1. Introduction to MODIA (“Meet and greet”) | Orient and engage patients; provide basic education and motivation to continue using MODIA. |

|

||

|

|

2. Enhancing motivation (“Taking the measurements”) | Build motivation by encouraging patients to reflect on the advantages of abstaining and the disadvantages of continuing to use opioids. |

|

||

|

|

3. Functional analysis (“The bird’s eye view”) | Empower patients to gain greater clarity on trigger situations and teach simple techniques to improve their ability to resist urges to use opioids. |

|

||

|

|

4. Behavioral coping with triggers (“Look over there!”) | Empower patients by teaching them how to identify and avoid high-risk situations and use simple behavioral techniques to cope with such situations. |

|

||

|

|

5. Cognitive coping with triggers (“The stranger in the mirror”) | Empower patients by teaching them simple methods targeting cognitions that increase risk for opioid use. |

|

||

|

|

6. Review of first cluster (“Let’s get physical”) | Review previously learned CBTc techniques and educate patients on role of healthy lifestyle in recovery. |

|

||

| Cluster 2: “Learning psychological flexibility skills” | |||||

|

|

7. Defusion and emotional distancing (“The defusion solution”) | Teach patients to learn “defusion” techniques to distance themselves from unhelpful thoughts and feelings. |

|

||

|

|

8. Acceptance and distress tolerance (“The acceptance conundrum”) | Teach patients acceptance skills to improve distress tolerance while remaining committed to recovery-related goals. |

|

||

|

|

9. Mindfulness and presence (“Enter the Buddha”) | Teach patients mindfulness techniques to reduce stress and improve coping with cravings, urges to use, and other aversive mental and emotional experiences. |

|

||

|

|

10. Self-discovery (“Who am I?”) | Teach patients self-discovery skills to help them cope with high-risk situations and improve their general ability to remain committed towards healthy life goals. |

|

||

|

|

11. Values clarification (“The best values”) | Teach patients to clarify valued life directions to orient them toward a healthy life “beyond opioid dependence” and thereby support their recovery goals. |

|

||

|

|

12. Commitment to healthy actions (“Do it!”) | Teach patients “behavioral commitment” techniques to support their efforts to achieve healthy recovery goals. |

|

||

aPlease see Multimedia Appendix 1 for a full outline of all 4 MODIA content clusters.

bMost “chats” also include a brief review of the patients’ emotional state, a review quiz, and homework assignment.

cCBT: cognitive behavioral therapy.

dPF: psychological flexibility.

Figure 3.

MODIA screenshot 2.

Figure 4.

MODIA screenshot 3.

Figure 5.

MODIA screenshot 4.

Although MODIA is aligned with CBT principles, it was not designed to present any 1 specific CBT treatment in digital format; rather, it uses a broad range of evidence-based behavior change techniques drawn from CBT, mindfulness, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), and motivational interviewing (MI) (Table 2). Mindfulness and ACT encourage patients to observe and accept negative thoughts and emotions without judgment, and MI encourages patients to articulate their reasons to change [64-66]. Techniques learned from these therapeutic modalities focus on increasing patient psychological flexibility or distress tolerance to support patients’ efforts to achieve recovery from OUD, consistent with recent evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of such techniques for substance use disorders [62].

Discussion

Principal Findings

Innovative, effective, and evidence-based management strategies are needed to address the opioid crisis, the substantial burden of OUD, and the limitations in access to effective counseling and care for individuals with OUD. To this end, a multidisciplinary team developed MODIA on the basis of a review of the relevant literature and in-person meetings with key stakeholders to offer individuals with OUD a tailored, interactive digital psychotherapy intervention. The purpose of this custom-tailored individualization and personalization is to maximize the personal relevance and emotional impact of the interaction because these aspects may increase learning effects and enhance overall treatment effectiveness [49,67]. The content of MODIA is CBT-consistent but also unique and innovative, utilizing psychological flexibility-based techniques that may be particularly effective in the treatment of substance use disorders [62]. Moreover, MODIA integrates principles and techniques from MI, which encourage the patient to build awareness of personal reasons to change, to effectively direct them toward change [66], and to acquire skills for enhanced psychological flexibility, which can be regarded as a cornerstone of mental health [61]. Notably, MODIA does not use a financially based contingency management element because this may hinder product adoption at both a health care professional (HCP) level and an insurer level. In addition, contingency management may create perverse patient incentives if rewards are designed to reinforce program use rather than recovery.

MODIA is also unique in that it adapts content on the basis of user input, enabling the delivery of an individualized therapeutic experience. MODIA is intended to alleviate barriers to psychological interventions and enable ready access to effective counseling for those who may not have the opportunity to retain counseling services. The self-directed nature of MODIA allows patients to complete the program on their own time and at their own pace without additional oversight by a therapist or counselor. This aspect of MODIA is aided by self-rated questionnaires that are embedded throughout the program and allow for self-monitoring of symptoms and progress. Although MODIA is intended to be used under guidance from a MAT prescriber, MODIA respects patient privacy and is not designed to report symptoms to the patients’ HCPs.

Limitations

Although MODIA was developed with the intention of lowering barriers to psychological interventions, it is not without limitations. Like other digital therapeutics, MODIA requires an internet connection and a suitable device. Hence, those with limited access to the necessary technology may not be able to use the program. In addition, while multiple randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the clinical value of Broca-based programs using the simulated dialogue approach, some patients may require more intensive or other forms of psychological support.

MODIA is being brought to market under the FDA COVID guidance for industry. MODIA is intended to provide digital CBT for patients with OUD, 18 years of age or older, as a part of a clinician-supervised MAT program for OUD. MODIA is a prescription-only device to be ordered by a clinician. MODIA has not been clinically tested and may therefore have unknown benefits and risks.

Conclusions

A multidisciplinary team of experts developed MODIA—a fully automated, custom-tailored digital therapy for the management of OUD. As part of a clinician-supervised MAT program, MODIA will allow more patients to begin psychotherapy at the same time they start opioid maintenance treatment. We expect that access to MODIA will improve the MAT experience and provide sustainable positive outcomes for patients with OUD. A randomized controlled trial will be conducted in the future to evaluate the efficacy of MODIA. Additional future studies may evaluate the long-term effects of MODIA; impact on treatment engagement, adherence, and early termination; as well as intervention effects on secondary outcomes such as mental health–related quality of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the pilot and feasibility test participants, as well as the development team, key stakeholders, and trained experts who informed the development of MODIA. Medical writing support was provided by Isaac Dripps, PhD, and Andrew Gomes, PhD, both from Ashfield MedComms, an Ashfield Health Company. This publication was funded by Orexo US, Inc.

Abbreviations

- ACT

acceptance and commitment therapy

- CBT

cognitive behavioral therapy

- CM

contingency management

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- HCP

health care professional

- MAT

medication-assisted treatment

- MI

motivational interviewing

- OUD

opioid use disorder

Content outline of the 24 MODIA "chats."

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: BM is an employee of GAIA AG. GU is an employee of Orexo US, Inc. CH has no competing interests to disclose.

References

- 1.American PA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) Arlington, TX: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Opioid Overdose Crisis. National Institute on Drug Abuse. [2021-05-01]. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis .

- 3.Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2019. [2021-09-14]. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt29393/2019NSDUHFFRPDFWHTML/2019NSDUHFFR1PDFW090120.pdf .

- 4.The Underestimated Cost of the Opioid Crisis. The Council of Economic Advisers. 2017. Nov, [2021-09-14]. https://ncsbn.org/2017_Underestimated_Cost_of_Opioid_Crisis.pdf .

- 5.O'Donnell J, Gladden RM, Mattson CL, Hunter CT, Davis NL. Vital Signs: Characteristics of Drug Overdose Deaths Involving Opioids and Stimulants - 24 States and the District of Columbia, January-June 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Sep 04;69(35):1189–1197. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6935a1. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6935a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H, Davis NL. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2017-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Mar 20;69(11):290–297. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018 Jan 04;67(5152):1419–1427. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm675152e1. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm675152e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) US Department of Health and Human Services. [2021-05-01]. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment .

- 9.Substance AHSA. Medications for opioid use disorder. US Department of Health and Human Services. [2021-09-20]. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/SAMHSA_Digital_Download/PEP21-02-01-002.pdf .

- 10.Oesterle TS, Thusius NJ, Rummans TA, Gold MS. Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid-Use Disorder. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019 Oct;94(10):2072–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.03.029.S0025-6196(19)30393-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattick R, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD002207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Field T, Beeson E, Jones L. The new ABCs: a practitioner’s guide to neuroscience-informed cognitive-behavior therapy. J Ment Health Couns. 2015;37:220. doi: 10.17744/1040-2861-37.3.206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregory VL, Ellis RJB. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and buprenorphine for opioid use disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2020 Sep 02;46(5):520–530. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2020.1780602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dugosh K, Abraham A, Seymour B, McLoyd K, Chalk M, Festinger D. A Systematic Review on the Use of Psychosocial Interventions in Conjunction With Medications for the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. J Addict Med. 2016;10(2):93–103. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000193. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26808307 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan S, Jiang H, Du J, Chen H, Li Z, Ling W, Zhao M. Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Opiate Use and Retention in Methadone Maintenance Treatment in China: A Randomised Trial. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0127598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127598. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127598 .PONE-D-13-49405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pashaei T, Shojaeizadeh D, Rahimi Foroushani A, Ghazitabatabae M, Moeeni M, Rajati F, M Razzaghi E. Effectiveness of Relapse Prevention Cognitive-Behavioral Model in Opioid-Dependent Patients Participating in the Methadone Maintenance Treatment in Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2013 Aug;42(8):896–902. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26056645 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kouimtsidis C, Reynolds M, Coulton S, Drummond C. How does cognitive behaviour therapy work with opioid-dependent clients? Results of the UKCBTMM study. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 2011 Jun 23;19(3):253–258. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2011.579194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barry DT, Beitel M, Cutter CJ, Fiellin DA, Kerns RD, Moore BA, Oberleitner L, Madden LM, Liong C, Ginn J, Schottenfeld RS. An evaluation of the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for opioid use disorder and chronic pain. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019 Jan 01;194:460–467. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.10.015. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/30508769 .S0376-8716(18)30794-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stotts AL, Green C, Masuda A, Grabowski J, Wilson K, Northrup TF, Moeller FG, Schmitz JM. A stage I pilot study of acceptance and commitment therapy for methadone detoxification. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012 Oct 01;125(3):215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.02.015. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22425411 .S0376-8716(12)00067-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolophine Tablets. 2015. [2021-09-14]. https://docs.boehringer-ingelheim.com/Prescribing%20Information/PIs/Roxane/Dolophine/Dolophine%20Tablets.pdf .

- 21.Prescribing Information | SUBLOCADE®. [2021-09-14]. https://www.sublocade.com/Content/pdf/prescribing-information.pdf .

- 22.Prescribing Information | SUBOXONE®. [2021-09-14]. https://www.suboxone.com/pdfs/prescribing-information.pdf .

- 23.SUBUTEX (buprenorphine sublingual tablets) [2021-09-14]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/020732s018lbl.pdf .

- 24.Highlights of Prescribing Information - Vivitrol. [2021-09-14]. https://www.vivitrol.com/content/pdfs/prescribing-information.pdf .

- 25.Full Prescribing Information - ZUBSOLV. [2021-09-14]. https://www.zubsolv.com/prescribinginformation .

- 26.Chasek C, Kawata R. An Examination of Educational and Training Requirements in Addiction Counseling. Vistas Online. [2021-09-14]. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/vistas/article_86_2016.pdf?sfvrsn=4 .

- 27.Madras BK, Connery H. Psychiatry and the Opioid Overdose Crisis. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ) 2019 Apr;17(2):128–133. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20190003. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31975968 .FOC_20190003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin L, Lofwall MR, Walsh SL, Knudsen HK. Perceived need and availability of psychosocial interventions across buprenorphine prescriber specialties. Addict Behav. 2019 Jun;93:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.01.023. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/30690416 .S0306-4603(18)31158-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spas J, Buscemi J, Prasad R, Janke E, Nigg C. The Society of Behavioral Medicine supports an increase in funding for Medication-Assisted-Treatment (MAT) to address the opioid crisis. Transl Behav Med. 2020 May 20;10(2):486–488. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz004.5301288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korthuis PT, McCarty D, Weimer M, Bougatsos C, Blazina I, Zakher B, Grusing S, Devine B, Chou R. Primary Care-Based Models for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: A Scoping Review. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Feb 21;166(4):268–278. doi: 10.7326/M16-2149. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27919103 .2589794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiellin D. The first three years of buprenorphine in the United States: experience to date and future directions. J Addict Med. 2007 Jun;1(2):62–67. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3180473c11.01271255-200706000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Projections of Supply and Demand for Selected Behavioral Health Practitioners: 2013-2025. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2016. [2021-09-14]. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/data-research/behavioral-health-2013-2025.pdf .

- 33.Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, Beletsky L, Keyes KM, McGinty EE, Smith LR, Strathdee SA, Wakeman SE, Venkataramani AS. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med. 2019 Nov;16(11):e1002969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002969. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002969 .PMEDICINE-D-19-02372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McNeely J, Kumar PC, Rieckmann T, Sedlander E, Farkas S, Chollak C, Kannry JL, Vega A, Waite EA, Peccoralo LA, Rosenthal RN, McCarty D, Rotrosen J. Barriers and facilitators affecting the implementation of substance use screening in primary care clinics: a qualitative study of patients, providers, and staff. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2018 Apr 09;13(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s13722-018-0110-8. https://ascpjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13722-018-0110-8 .10.1186/s13722-018-0110-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams J, Volkow N. Ethical Imperatives to Overcome Stigma Against People With Substance Use Disorders. AMA J Ethics. 2020 Aug 01;22(1):E702–708. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2020.702. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/ethical-imperatives-overcome-stigma-against-people-substance-use-disorders/2020-08 .amajethics.2020.702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Godersky ME, Saxon AJ, Merrill JO, Samet JH, Simoni JM, Tsui JI. Provider and patient perspectives on barriers to buprenorphine adherence and the acceptability of video directly observed therapy to enhance adherence. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2019 Mar 13;14(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s13722-019-0139-3. https://ascpjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13722-019-0139-3 .10.1186/s13722-019-0139-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santoro T, Santoro J. Racial Bias in the US Opioid Epidemic: A Review of the History of Systemic Bias and Implications for Care. Cureus. 2018 Dec 14;10(12):e3733. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3733. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/30800543 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang JC, Roman-Urrestarazu A, Brayne C. Responses among substance abuse treatment providers to the opioid epidemic in the USA: Variations in buprenorphine and methadone treatment by geography, operational, and payment characteristics, 2007-16. PLoS One. 2020;15(3):e0229787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229787. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229787 .PONE-D-19-08039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Understanding DTx: A New Category of Medicine. Digital Therapeutic Alliance. 2017. [2021-09-14]. https://dtxalliance.org/understanding-dtx .

- 40.Hollis C, Morriss R, Martin J, Amani S, Cotton R, Denis M, Lewis S. Technological innovations in mental healthcare: harnessing the digital revolution. Br J Psychiatry. 2015 Apr;206(4):263–265. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.142612.S0007125000278677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wright JH, Owen JJ, Richards D, Eells TD, Richardson T, Brown GK, Barrett M, Rasku MA, Polser G, Thase ME. Computer-Assisted Cognitive-Behavior Therapy for Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019 Mar 19;80(2):18r12188. doi: 10.4088/JCP.18r12188. http://www.psychiatrist.com/JCP/article/Pages/2019/v80/18r12188.aspx . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Twomey C, O'Reilly G, Bültmann O, Meyer B. Effectiveness of a tailored, integrative Internet intervention (deprexis) for depression: Updated meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0228100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228100. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228100 .PONE-D-19-25463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andersson G, Carlbring P, Titov N, Lindefors N. Internet Interventions for Adults with Anxiety and Mood Disorders: A Narrative Umbrella Review of Recent Meta-Analyses. Can J Psychiatry. 2019 Jul;64(7):465–470. doi: 10.1177/0706743719839381. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31096757 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christensen DR, Landes RD, Jackson L, Marsch LA, Mancino MJ, Chopra MP, Bickel WK. Adding an Internet-delivered treatment to an efficacious treatment package for opioid dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014 Dec;82(6):964–972. doi: 10.1037/a0037496. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25090043 .2014-31346-001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campbell AN, Nunes EV, Matthews AG, Stitzer M, Miele GM, Polsky D, Turrigiano E, Walters S, McClure EA, Kyle TL, Wahle A, Van Veldhuisen P, Goldman B, Babcock D, Stabile PQ, Winhusen T, Ghitza UE. Internet-delivered treatment for substance abuse: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2014 Jun;171(6):683–690. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13081055. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24700332 .1859474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.FDA clears mobile medical app to help those with opioid use disorder stay in recovery programs. US Food and Drug Administration. 2018. [2021-05-01]. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-clears-mobile-medical-app-help-those-opioid-use-disorder-stay-recovery-programs .

- 47.Clinician information - Pear Therapeutics. 2019. [2021-05-01]. https://2kw3qa2w17x12whtqxlb6sjc-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/PEAR-MKT-025-reSET-O-Clin-Brief-Sum_Dec2019.pdf .

- 48.Lustria MLA, Noar SM, Cortese J, Van Stee SK, Glueckauf RL, Lee J. A meta-analysis of web-delivered tailored health behavior change interventions. J Health Commun. 2013;18(9):1039–1069. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.768727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krebs P, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS. A meta-analysis of computer-tailored interventions for health behavior change. Prev Med. 2010;51(3-4):214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.004. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20558196 .S0091-7435(10)00231-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rimer B, Kreuter M. Advancing Tailored Health Communication: A Persuasion and Message Effects Perspective. J Commun. 2006;56:201. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00289.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yardley L, Morrison L, Bradbury K, Muller I. The person-based approach to intervention development: application to digital health-related behavior change interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2015 Jan 30;17(1):e30. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4055. https://www.jmir.org/2015/1/e30/ v17i1e30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zill J, Christalle E, Meyer B, Härter M, Dirmaier J. The Effectiveness of an Internet Intervention Aimed at Reducing Alcohol Consumption in Adults. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019 Feb 22;116(8):127–133. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0127. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0127.arztebl.2019.0127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meyer B, Weiss M, Holtkamp M, Arnold S, Brückner K, Schröder J, Scheibe F, Nestoriuc Y. Effects of an epilepsy-specific Internet intervention (Emyna) on depression: Results of the ENCODE randomized controlled trial. Epilepsia. 2019 Apr;60(4):656–668. doi: 10.1111/epi.14673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berger T, Urech A, Krieger T, Stolz T, Schulz A, Vincent A, Moser CT, Moritz S, Meyer B. Effects of a transdiagnostic unguided Internet intervention ('velibra') for anxiety disorders in primary care: results of a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2017 Jan;47(1):67–80. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716002270.S0033291716002270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Musante K, DeWalt B. Participant Observation: A Guide for Fieldworkers (2nd Edition) Lanham, MD: Rowman AltaMira Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles MP, Cane J, Wood CE. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013 Aug;46(1):81–95. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meyer B, Berger T, Caspar F, Beevers CG, Andersson G, Weiss M. Effectiveness of a novel integrative online treatment for depression (Deprexis): randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2009 May 11;11(2):e15. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1151. https://www.jmir.org/2009/2/e15/ v11i2e15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jacob GA, Hauer A, Köhne S, Assmann N, Schaich A, Schweiger U, Fassbinder E. A Schema Therapy-Based eHealth Program for Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder (priovi): Naturalistic Single-Arm Observational Study. JMIR Ment Health. 2018 Dec 17;5(4):e10983. doi: 10.2196/10983. https://mental.jmir.org/2018/4/e10983/ v5i4e10983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pöttgen J, Moss-Morris R, Wendebourg J, Feddersen L, Lau S, Köpke S, Meyer B, Friede T, Penner I, Heesen C, Gold SM. Randomised controlled trial of a self-guided online fatigue intervention in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep;89(9):970–976. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317463.jnnp-2017-317463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gómez Penedo JM, Babl AM, Grosse Holtforth M, Hohagen F, Krieger T, Lutz W, Meyer B, Moritz S, Klein JP, Berger T. The Association of Therapeutic Alliance With Long-Term Outcome in a Guided Internet Intervention for Depression: Secondary Analysis From a Randomized Control Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Mar 24;22(3):e15824. doi: 10.2196/15824. https://www.jmir.org/2020/3/e15824/ v22i3e15824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kashdan TB, Rottenberg J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010 Nov;30(7):865–878. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21151705 .S0272-7358(10)00041-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ii T, Sato H, Watanabe N, Kondo M, Masuda A, Hayes SC, Akechi T. Psychological flexibility-based interventions versus first-line psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2019 Jul;13:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide (Third Edition) National Institute on Drug Abuse. 2018. [2021-05-01]. https://www.drugabuse.gov/download/675/principles-drug-addiction-treatment-research-based-guide-third-edition.pdf .

- 64.Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1982 Apr;4(1):33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3.0163-8343(82)90026-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dindo L, Van Liew JR, Arch JJ. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: A Transdiagnostic Behavioral Intervention for Mental Health and Medical Conditions. Neurotherapeutics. 2017 Jul;14(3):546–553. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0521-3. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28271287 .10.1007/s13311-017-0521-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Crawley A, Murphy L, Regier L, McKee N. Tapering opioids using motivational interviewing. Can Fam Physician. 2018 Aug;64(8):584–587. http://www.cfp.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=30108077 .64/8/584 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kreuter MW, Wray RJ. Tailored and targeted health communication: strategies for enhancing information relevance. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27 Suppl 3:S227–S232. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Content outline of the 24 MODIA "chats."