Abstract

Molecular surveillance studies have documented the extensive spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) clones. Studies carried out by Centro de Epidemiologia Molecular-Network for Tracking Gram-Positive Pathogenic Bacteria (CEM/NET) led to the identification of two international multidrug-resistant strains, which were designated as the Iberian and Brazilian MRSA clones and which were defined by multiple genomic typing methods; these included ClaI restriction digests hybridized with mecA- and Tn554-specific DNA probes and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). The genotypic characteristics of these clones are distinct: the Iberian clone is defined as mecA type I, Tn554 type E (or its variants), and PFGE pattern A (I:E:A), whereas the Brazilian clone is defined as mecA type XI (or its variants), Tn554 type B, and PFGE pattern B (XI:B:B). In this study, we characterized 59 single-patient isolates of MRSA collected during 1996 and 1997 at seven hospitals located in Prague and five other cities in the Czech Republic by using the methodologies mentioned above and by using ribotyping of EcoRI and HindIII digests hybridized with a 16S-23S DNA probe. The Brazilian MRSA clone (XI:B:B) was the major clone (80%) spread in two hospitals located in Prague and one located in Brno; the Iberian MRSA clone (I:E:A or its variant I:DD:A), although less representative (12%), was detected in two hospitals, one in Prague and the other in Plzen. Almost all the strains belonging to clone XI:B:B (45 of 47) corresponded to a unique ribotype, E1H1, whereas most strains of the I:E:A and I:DD:A clonal types (6 of 7) corresponded to ribotype E2H2.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has become one of the most prevalent nosocomial pathogens throughout the world, capable of causing a wide range of hospital infections. The emergence of MRSA as a nosocomial pathogen in the Czech Republic has been documented by reports of routine oxacillin MIC data collected from 13 to 18 Czech hospitals between 1989 and 1994 (35). Oxacillin resistance levels in S. aureus in those years were 9, 15, 8, 7, 9, and 5%. No molecular typing studies were performed.

Ribotyping has been used in several laboratories as a classification and typing method for many microorganisms, including MRSA clinical isolates (3, 10, 12). However, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) is considered more discriminatory, reproducible, and applicable to all bacteria (15, 20, 28–30, 32).

The hybridization of ClaI restriction digests with the mecA- and Tn554-specific DNA probes, a method first used by Kreiswirth et al. (13) and later combined with PFGE, was shown to be a successful method for typing MRSA (6) and for tracking the spread of MRSA clones (11, 26, 31). Previous studies documented the emergence of two particularly widely disseminated multiresistant clones of MRSA. One of these, the Iberian MRSA clone, first identified as the dominant clone in a major outbreak of MRSA disease in the Bellvitge Hospital in Barcelona, Spain, in 1989 (11), was subsequently detected in at least eight Portuguese hospitals (2, 19, 25, 26), hospitals in Scotland, Italy, Belgium, and Germany (16), and one hospital in New York (21). A second and distinct multiresistant clone (Brazilian MRSA clone) was shown to be widely spread in Brazilian hospitals separated from one another by several thousand kilometers (31) and to be disseminated in Portugal (1, 19) and Argentina (4). More recently, a third international MRSA clone was defined and seen as characteristic of pediatric populations (23).

Monitoring the geographic expansion of such epidemic clones is important for understanding why certain MRSA clones are spread over considerable distances, whereas others are limited to a single country, city, or hospital (7–9, 14, 22). In this paper, we describe the characterization by molecular typing techniques of a collection of strains recovered from seven hospitals located in Prague, northern and eastern Bohemia, and northern and eastern Moravia in the Czech Republic. Our molecular data clearly document the presence of the two internationally spread Brazilian and Iberian MRSA clones in the Czech Republic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hospitals.

Seven large (more than 1,000-bed) hospitals of the Czech Republic, including four teaching hospitals (two in Prague, one in Olomouc, and one in Plzen, designated KV and KR, OL, and PL, respectively) and three regional hospitals (in Brno, Ostrava, and Ústí nad Labem, designated BB, OV, and UL, respectively), participated in this study (Table 1). One of the Prague hospitals and the Brno and Ostrava hospitals (KV, BB, and OV) have burn departments. The central burn department is located in hospital KV. The codes, locations, and numbers of beds for the hospitals, as well as the number of S. aureus strains and the number and percentage of MRSA strains recovered from each hospital, are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Hospital data and S. aureus isolates from the Czech Republic for 1996 and 1997a

| Yr and hospital | City | No. of beds | No. of S. aureus isolates | No. (%) of MRSA isolates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | ||||

| BB | Brno | 1,320 | 200 | 2 (1) |

| KR | Prague | 1,632 | 225 | 15 (7) |

| KV | Prague | 1,252 | 89 | 20 (22) |

| OL | Olomouc | 1,779 | 238 | 2 (1) |

| OV | Ostrava | 3,000 | 271 | 3 (1) |

| PL | Plzen | 1,500 | 200 | 6 (3) |

| UL | Ústí nad Labem | 1,270 | 92 | 0 (0) |

| Subtotal | 11,753 | 1,315 | 48 (4) | |

| 1997 | ||||

| KV | Prague | 1,252 | 719 | 11 (1.5) |

| Grand total | 2,034 | 59 (3) |

April to June 1996, September to October 1996, and April to July 1997. See text for details about hospitals.

Staphylococcal strains.

A total of 1,315 strains of S. aureus were collected at the seven participating hospitals during two periods of time in 1996 (April to June and September to October). The 1997 survey included 719 strains collected only at hospital KV in Prague from April to July. These isolates were from clinical specimens from individual patients and were mainly from superficial colonization or infection (burns or wounds), respiratory tract infections, pus and blood, and a few other sites.

The collected isolates were placed in mannitol salt agar medium and were sent to the National Institute of Public Health laboratory in Prague. All the isolates were tested by the API Staph (Biomerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France), clumping factor, and coagulase production tests. In addition, resistance to oxacillin was tested for all the isolates.

The frequency of MRSA strains in each hospital (Table 1) was low for most of the hospitals (0 to 7%), with the exception of hospital KV in Prague, which had a 22% frequency during 1996. The number of MRSA strains analyzed in this study was 59, corresponding to all the MRSA strains isolated at the seven participating hospitals during the study periods.

Control strains.

The reference strains for ClaI-mecA and ClaI-Tn554 restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis and PFGE were obtained from Instituto de Tecnologia Química e Biológica and The Rockefeller University strain collections. The positive and negative control strains used for mecA detection by PCR were S. aureus ATCC 27626 and ATCC 25923, respectively.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

The strains were tested against a panel of 14 antibiotics (penicillin, oxacillin, amikacin, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, fusidic acid, gentamicin, mupirocin, tetracycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, chloramphenicol, vancomycin, and teicoplanin) according to National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) guidelines (18). Inhibition zones were measured with Radius (Mast, Merseyside, United Kingdom) video equipment and interpreted according to NCCLS standards (18). The interpretative criterion for susceptibility to fusidic acid was a zone diameter smaller than 22 mm (5, 34). The production of β-lactamase was tested with a nitrocefin solution of 500 μg/ml (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) by rubbing a loopful of colonies taken from the edge of an inhibition zone onto filter paper soaked with nitrocefin.

Screening for oxacillin resistance.

Phenotypic oxacillin resistance, determined at the different hospital clinical laboratories, was confirmed by an agar screen test performed according to the NCCLS recommendations (18) with Mueller-Hinton agar containing 2% NaCl and 6 μg of oxacillin per ml. The MIC of oxacillin for all isolates was also examined by an agar dilution method according to NCCLS recommendations (18) with Mueller-Hinton agar containing 2% NaCl and oxacillin in concentrations ranging from 0.016 to 256 μg/ml.

Preparation of whole-cell DNA for PCR.

A previously described method with minor modifications (10) was used. Cells grown overnight on nutrient agar at 35°C for 24 h were harvested and centrifuged at 16,000 × g. The pellet (10 mg) was washed with 1.8 μl of saline, resuspended in 930 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA [pH 8])–10 μl of lysostaphin solution (450 U/ml; Sigma)–25 μl of lysozyme solution (20 mg/ml; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. A 25-μl volume of 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (final concentration, 0.5%) and 5 μl of proteinase K (10 mg/ml) (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) were added. The mixture was incubated for 1 h at 55°C. One milliliter of phenol was added, and the mixture was shaken gently at room temperature for 5 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube, 1 volume of phenol was added, and the mixture was centrifuged. The upper phase was collected and pipetted into 2 volumes of cold 95% ethanol. The tube contents were mixed, and the pellet was washed with 70% ethanol. After being dried, the pelleted DNA was dissolved in 50 μl of TE buffer by heating at 55°C for 30 min. The DNA was stored at −20°C.

Amplification of the mecA gene.

As a template for PCR amplification, 5 μl of purified DNA was diluted 10 times in deionized distilled water, denatured at 95°C for 5 min, and chilled on ice. The following primers (17) were used: RSM 2647 (5′-AAA ATC GAT GGT AAA GGT TGG C-3′) and RSM 2648 (5′-AGT TCT GCA GTA CCG GAT TTG C-3′). The reaction mixture contained 200 mM each nucleotide triphosphate, 0.25 mM each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, and 0.1% Triton. To a 100-μl reaction volume, 0.5 μl of Taq polymerase (5 U/ml) (Promega, Madison, Wis.) was added. Amplification was carried out by use of a thermal cycler with a model PTC100 programmable thermal controller (MJ Research Inc., Waltham, Mass.) under the following conditions: 40 cycles of amplification at −94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min were followed by 5 min at 72°C. A positive result was inferred by detection of a 533-bp band representing part of the mecA gene by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel for 1 h at 100 V.

mecA-Tn554 polymorphisms and PFGE.

Chromosomal DNA, conventional gels, and gels for PFGE were prepared as previously described (6). DNA fragments were transferred to Hybond N+ (Amersham International, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) nylon membranes (24) and hybridized with probes for mecA (6) and Tn554 (6, 13) by use of a nonradioactive labeling system (RPN3040; Amersham).

Ribotyping.

Chromosomal DNAs (5 μl) were digested for 4 h at 37°C with 40 U each of restriction endonucleases EcoRI and HindIII (MBI, Fermentas, Lithuania). Each digest was loaded on a 0.7% agarose gel and separated at 35 V for 16 h in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. Restriction fragments were transferred by vacuum blotting to a Zeta-probe membrane (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Prehybridization was performed with prehybridization solution (1 mM EDTA, 0.5 M NaH2PO4 [pH 7.2], 7% SDS) at 60°C for 10 min. Escherichia coli MRE600 was the source of 16S and 23S rRNA for transcription with digoxigenin-labeled cDNA (Boehringer). Hybridization was performed overnight at 60°C with prehybridization solution supplemented with 10 μl (20 ng/ml) of digoxigenin-labeled ribosomal probe and 5 μl (20 ng/ml) of digoxigenin-labeled lambda DNA per 10 μl and per membrane (15 by 15 cm). The membrane was washed twice with 1 mM EDTA–40 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 7.2)–5% SDS and twice with 1 mM EDTA–40 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 7.2)–1% SDS at 60°C for 15 min each time. The hybridization fragments were visualized by a colorimetric detection system (Boehringer) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Interpretation of genotypic results.

The mecA and Tn554 hybridization patterns were identified by single roman numerals and letters, respectively. A single band difference defined a different pattern (13). The PFGE types were assigned according to previously defined criteria (33) and were identified by uppercase letters, and subtypes (one to six band differences) were identified by numbers following the uppercase letters. PFGE patterns were compared by visual inspection followed by computer analysis with Whole Band Analyzer version 3.3 (BioImage) software for a UNIX SparcStation4 running SunOS version 5.5.1 (22). Ribotypes were identified by the letter E or H, corresponding to the EcoRI or HindIII fingerprints, followed by numerals. A single band difference defined a different pattern.

RESULTS

Resistance to oxacillin and presence of the mecA gene.

Of 1,315 S. aureus strains recovered during 1996 and 719 strains recovered during 1997, 48 and 11, respectively, were confirmed to be MRSA in the research laboratory. The strains were retested for coagulase production, oxacillin resistance phenotype, and presence of the mecA gene by PCR amplification or by DNA hybridization of ClaI digests with the mecA-specific probe.

Antimicrobial susceptibility.

The 48 MRSA strains from the two 1996 periods showed the following frequencies of resistance to the 14 antibiotics. All strains were resistant to penicillin and oxacillin. Some strains were resistant to erythromycin, gentamicin, and clindamycin (94%); trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (90%); ciprofloxacin (88%); tetracycline (85%); amikacin (75%); mupirocin (13%); chloramphenicol (6%); and fusidic acid (6%). All isolates were susceptible to vancomycin and teicoplanin (Table 2). The 11 MRSA strains from 1997 were all resistant to penicillin, oxacillin, erythromycin, clindamycin, gentamicin, and ciprofloxacin. Some strains were resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, and amikacin (91%) and to mupirocin (27%). All isolates were susceptible to chloramphenicol, fusidic acid, vancomycin, and teicoplanin (Table 2). The overwhelming majority (87%) of the isolates collected in 1996 and 1997 were susceptible to 500 μg of spectinomycin per ml.

TABLE 2.

Correlation between clonal types and phenotypes of resistance to antibiotics of MRSA strains from the Czech Republic for 1996 and 1997

| Yr | Clonal typea | Resistance tob:

|

No. (%) of strains | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEN | OXA | ERY | GEN | CLI | SXT | CIP | TET | AMI | MUP | FUS | CMP | |||

| 1996 | XI:B:B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | 31 (65) |

| I:DD:A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | 3 (7) | |

| I:DD:A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | 2 (4) | |

| XI:B:B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 1 (2) | |

| XI:B:B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | 1 (2) | |

| XI:B:B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 1 (2) | |

| I:E:A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | 1 (2) | |

| XI:B:B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | 1 (2) | |

| XI:B:B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | 1 (2) | |

| XI:B:B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | 1 (2) | |

| I:NH:E | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | 1 (2) | |

| IX:NH:E | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | 1 (2) | |

| II:NH:C | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | 1 (2) | |

| II:NH:C | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | 1 (2) | |

| II:NH:D | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | 1 (2) | |

| No. (%) of strains | 48 (100) | 48 (100) | 45 (94) | 45 (94) | 45 (94) | 43 (90) | 42 (88) | 41 (85) | 36 (75) | 6 (13) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) | 48 (100) | |

| 1997 | XI:B:B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | 7 (64) |

| XI:B:B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 2 (18) | |

| XI:B:B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | 1 (9) | |

| I:E:A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 1 (9) | |

| No. (%) of strains | 11 (100) | 11 (100) | 11 (100) | 11 (100) | 11 (100) | 10 (91) | 11 (100) | 10 (91) | 10 (91) | 3 (27) | 11 (100) | |||

Clonal types were defined on the basis of a combination of mecA and Tn554 polymorphisms and PFGE patterns (mecA, Tn554, and PFGE types).

PEN, penicillin; OXA, oxacillin; ERY, erythromycin; GEN, gentamicin; CLI, clindamycin; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; CIP, ciprofloxacin; TET, tetracycline; AMI, amikacin; MUP, mupirocin; FUS, fusidic acid; CMP, chloramphenicol. Y, yes; N, no.

The MICs of oxacillin for the MRSA isolates were 4 μg/ml (1 isolate), 16 μg/ml (2 isolates), 128 μg/ml (3 isolates), 256 μg/ml (11 isolates), 512 μg/ml (38 isolates), and 1,024 μg/ml (3 isolates); 1 isolate was not analyzed.

Clonal assignments. (i) mecA, Tn554, and PFGE types.

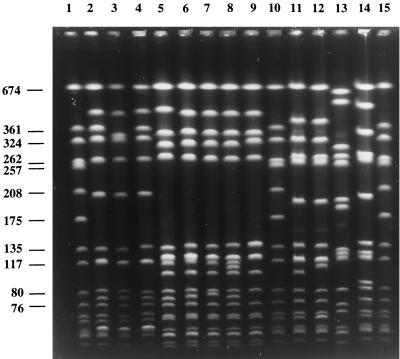

Strains were classified into clonal types on the basis of a combination of the mecA and Tn554 polymorphisms and PFGE patterns (mecA, Tn554, and PFGE types) as previously described (6). All the clonal types found in this study are shown in Table 3. The most surprising observation in this study was the high representation of a single PFGE pattern (designated B), which was shared by 47 of the 59 MRSA isolates recovered during 1996 and 1997 (80%). All isolates included in PFGE pattern B were subdivided into four subtypes (B1 to B4), with B1 being the most frequent (43 of 47 strains); the profile of these 43 strains was identical to the profile of strain HU25 (31), representative of the Brazilian MRSA clone except for one fragment difference (Fig. 1). All isolates included in PFGE pattern B were associated with a single ClaI-mecA polymorph (XI) and ClaI-Tn554 pattern (B). The clone with these molecular features was designated XI:B:B.

TABLE 3.

Clonal characterization of the 59 MRSA strains (48 from 1996 and 11 from 1997) recovered at seven hospitals in the Czech Republica

| Yr and hospital | No. of S. aureus isolates | City | No. of MRSA isolates | Clonal types

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ribotype (n = 8)

|

mecA, Tn554, and PFGE subtypes (n = 12)

|

SmaI hybridization fragments (kb, approx)

|

|||||||

| Designation | No. of isolates | Designation | No. of isolates | mecA | Tn554b | ||||

| 1996 | |||||||||

| BB | 200 | Brno | 2 | E1H1 | 2 | XI:B:B1 | 2 | 108.6 | 614.7, 108.6, 85.9 |

| KR | 225 | Prague | 15 | E1H1 | 15 | XI:B:B1 | 12 | 108.6 | 614.7, 108.6, 85.9 |

| XI:B:B2 | 1 | 108.6 | 614.7, 108.6, 85.9 | ||||||

| XI:B:B3 | 1 | 108.6 | 614.7, 108.6, 85.9 | ||||||

| XI:B:B4 | 1 | 108.6 | 614.7, 108.6, 85.9 | ||||||

| KV | 89 | Prague | 20 | E1H1 | 20 | XI:B:B1 | 20 | 108.6 | 614.7, 108.6, 85.9 |

| OL | 238 | Olomouc | 2 | E3H2 | 1 | II:NH:C1 | 1 | 184.3 | NH |

| E5H2 | 1 | II:NH:C2 | 1 | 184.3 | NH | ||||

| OV | 271 | Ostrava | 3 | E2H2 | 2 | IX:NH:E | 1 | 184.3 | NH |

| I:NH:E | 1 | 206.3 | NH | ||||||

| E6H3 | 1 | II:NH:D | 1 | 172.5 | NH | ||||

| PL | 200 | Plzen | 6 | E2H2 | 6 | I:DD:A1 | 5 | 206.3 | 614.7, 396.7 |

| I:E:A1 | 1 | 206.3 | 614.4 | ||||||

| UL | 92 | Ústí nad Labem | 0 | ||||||

| 1997 | |||||||||

| KV | 719 | Prague | 11 | E1H1 | 8 | XI:B:B1 | 8 | 108.6 | 614.7, 108.6, 85.9 |

| E1H5 | 1 | XI:B:B4 | 1 | 108.6 | 614.7, 108.6, 85.9 | ||||

| E7H1 | 1 | XI:B:B1 | 1 | 108.6 | 614.7, 108.6, 85.9 | ||||

| E4H2 | 1 | I:E:A2 | 1 | 206.3 | 614.7 | ||||

See text for details about hospitals.

These insertions were previously mapped in equivalent SmaI fragments (25). NH, no homology with the probe.

FIG. 1.

PFGE of SmaI macrorestriction fragments of MRSA clinical isolates from the Czech Republic and representatives of international MRSA clones. Lanes 1, 10, and 15, reference strain NCTC 8325; lane 2, HPV107, representative of the Iberian clone (26) (pattern A); lane 3, RCH1 (pattern A2); lane 4, CR9 (pattern A1); lane 5, HU25, representative of the Brazilian clone (31) (pattern B); lane 6, CR3 (pattern B1); lane 7, CR2 (pattern B2); lane 8, CR13 (pattern B3); lane 9, CR21 (pattern B4); lane 11, CR1 (pattern C1); lane 12, CR45 (pattern C2); lane 13, CR44 (pattern D); lane 14, CR11 (pattern E). Numbers at left are in kilobases.

The second most prevalent PFGE pattern was found in seven isolates (12%). Six of the seven strains shared PFGE subtype A1; this profile was found to be indistinguishable from the profile of strain HPV107 (PFGE pattern A), representative of the Iberian MRSA clone (26) (Fig. 1). The remaining strain was included in PFGE subtype A2. PFGE subtypes A1 and A2 were associated with a unique ClaI-mecA type I and with ClaI-Tn554 patterns E (two isolates) and DD (five isolates). These isolates were assigned to two related clonal types, I:E:A and I:DD:A.

The remaining and distinct PFGE patterns (C, D, and E) were represented by five sporadic isolates included in ClaI-mecA polymorphs I, II, and IX and ClaI-Tn554 pattern NH (absence of the Tn554 transposon) (Table 3).

The locations of mecA and Tn554 in the SmaI fragments were established by hybridization with the appropriate probes (Table 3).

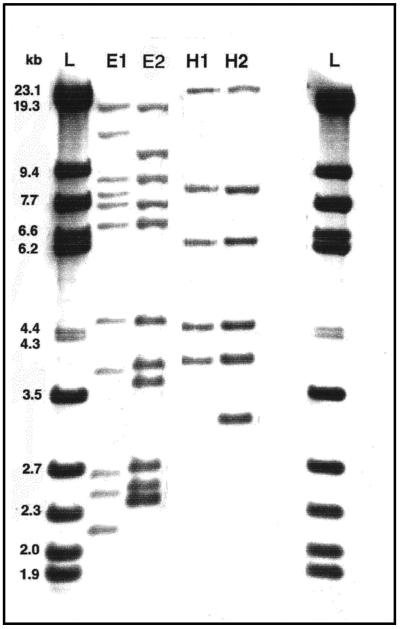

(ii) Ribotypes.

The 48 strains from 1996 and the 11 strains from 1997 were classified into ribotypes on the basis of fingerprints produced after hybridization of the EcoRI and HindIII digests with the 16S-23S DNA probe. All the ribotypes found in this study are shown in Table 3. The majority of the 1996 isolates were included in ribotype E1H1 (37 of 48, or 77%) and ribotype E2H2 (8 of 48, or 17%); three other ribotypes (E3H2, E5H2, and E6H3) were represented by single isolates only. Concerning the 11 isolates from 1997, most were also classified as E1H1 (8 of 11, or 72%); the additional patterns E1H5, E4H2, and E7H1 were found in single isolates only. The most representative ribotypes, E1H1 and E2H2, are shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Predominant ribotypes found among MRSA clinical isolates from the Czech Republic. Lanes L, molecular size standard (lambda digest obtained with StyI and HindIII); lanes E1, E2, H1, and H2, ribotypes E1, E2, H1, and H2, respectively. E, EcoRI; H, HindIII. The DNA probe consisted of a 16S-23S DNA fragment of E. coli MRE600 (Boehringer).

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of MRSA in Europe is known to vary drastically from country to country as well as among hospitals in the same country (36). The seven hospitals located in Prague, northern and eastern Bohemia, and northern and eastern Moravia in the Czech Republic also had different frequencies of MRSA; the frequency was very low (0 to 4%) in almost all the hospitals, particularly those in Ústí nad Labem, Ostrava, Brno, and Plzen, and higher (7 and 22%) in the two hospitals in Prague. One of these hospitals (KV) has a highly specialized central burn department, where most of the MRSA strains from 1996 and all of the MRSA strains from 1997 were recovered and where MRSA carriage or infection constitutes an important clinical problem. The higher frequency of MRSA observed at hospital KV during 1996 was probably due to the fact that there were more burned patients with longer hospitalization periods in 1996 than in 1997. Moreover, several new wards were opened in 1997, redistributing the number of beds per ward and therefore decreasing the risk of cross-infection and consequently the frequency of MRSA.

All 48 strains from 1996 but 1 were resistant to one or more antibiotics in addition to penicillin and oxacillin. About 94% of the strains were resistant to at least five antibiotics (penicillin, oxacillin, erythromycin, gentamicin, and clindamycin); 88% were resistant at least to seven antibiotics (penicillin, oxacillin, erythromycin, gentamicin, clindamycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ciprofloxacin). The most frequent profile among the isolates from 1996 and 1997 was resistance to penicillin, oxacillin, erythromycin, gentamicin, clindamycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, and amikacin. The phenotypes of resistance to the antimicrobial agents are shown in Table 2.

In this study, different molecular typing methods were used in order to establish the clonal types of all the MRSA strains recovered in 1996 and 1997 at the seven hospitals in the Czech Republic involved in this study.

The discriminatory powers of ribotyping and the combined PFGE, mecA, and Tn554 typing methodologies were compared. The majority of the isolates (77%) belonged to a clonal group defined as XI:B:B (mecA, Tn554, and PFGE types) and were associated with ribotype E1H1. This clonal group included all MRSA strains from the two hospitals in Prague (KR and KV) and from a third hospital (BB) located in Brno, 200 km from Prague, and was not spread elsewhere in the country.

The so-called Brazilian MRSA clone with these molecular properties (XI::B::B) (1) was previously seen as spread over large distances in Brazil (31), Argentina (4), and Uruguay (19a) and seemed to have been introduced into Portugal in 1995 (1, 19).

The next most important clones found among the Czech MRSA strains (I:E:A and its relative I:DD:A) were detected in 1996 in a unique hospital (PL) located in Plzen and in 1997 in the large teaching hospital (KV) in Prague. In this study, most I:E:A and I:DD:A strains were associated with a unique ribotype, E2H2, although this particular ribotype also included strains not related to these clones. Clone I:E:A is another international MRSA clone designated the Iberian clone, first described in Spain (11), later found in Portugal (2, 19, 25, 26) and Italy, Scotland, Belgium, and Germany (16), and more recently found in the United States (21).

In the present study, ribotyping was more effective in discriminating Brazilian clone isolates than in discriminating Iberian clone isolates.

The identification of epidemic clones by ribotyping may be extremely useful, particularly for clinical microbiologists who do not have the possibility of typing the strains by using PFGE. In this study, we found that ribotyping was able to detect the epidemic MRSA Brazilian clone, and the patterns produced by the two enzymes used (EcoRI and HindIII) were reproducible. In a previous study, a selection of isolates belonging to the Iberian and Brazilian clones could also be discriminated by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA-PCR (2), although the patterns obtained through this methodology were very difficult to reproduce in different experiments (2a).

The large capacity of certain MRSA clones to spread over enormous distances is still unexplained, but it is unlikely that it can be explained only by dispersal through patient transfer or health care facilities. Although the incidence of MRSA among healthy human populations seems to be very low (27), it is probable that the dissemination of epidemic MRSA clonal types over large distances is linked to long-term carriage and to the increasing mobility of populations all over the world. In fact, the spread of these two international MRSA clones in the Czech Republic might have been caused by the increasing number of tourists visiting the country since the early 1990s. Other routes of spread are, however, under investigation.

Contrasting situations were found in some countries, as in Hungary, where a single clone was spread in six hospitals located in towns hundreds of kilometers apart without dispersal to other countries (8), and Poland, where a recent study confirmed the existence of two main clusters of MRSA which are circulating in that country and which are unique MRSA clones not detected elsewhere (14).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by Project 2/2.1/BIO/1254/95 from PRAXIS XXI, CEM/NET; Project 31 from IBET; and a grant from Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, Portugal, awarded to H. de Lencastre. Support was also received from grant IGA 3500-3 awarded to J. Schindler by the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic. O. Melter was supported by Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian for his CEM/NET Training Program at ITQB/UNL, Oeiras, Portugal, from April to June 1998. M. Aires de Sousa received fellowships BTL6260/95 and BD13731/97 from PRAXIS XXI. R. Mato was supported by grant BPD/6077/95 from PRAXIS XXI.

We are grateful to E. Bendova, T. Bergerova, D. Burgetova, E. Chmelarova, M. Hatala, M. Kolar, and J. Stehlik from the Czech Republic for sending the staphylococcal isolates and to Sandra Cabo Verde from ITQB/UNL for DNA typing of the 1997 strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aires de Sousa M, Sanches I S, Ferro M L, Vaz M J, Saraiva Z, Tendeiro T, Serra J, de Lencastre H. Intercontinental spread of a multidrug-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2590–2596. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2590-2596.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aires de Sousa M, Sanches I S, van Belkum A, van Leeuwen W, Verbrugh H, de Lencastre H. Characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from Portuguese hospitals by multiple genotyping methods. Microb Drug Resist. 1996;2:331–341. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Aires de Sousa, M., et al. Unpublished results.

- 3.Blanc D S, Lugeon C, Wenger A, Siegrist H H, Francioli P. Quantitative antibiogram typing using inhibition zone diameters compared with ribotyping for epidemiological typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2505–2509. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2505-2509.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corso A, Santos Sanches I, Aires de Sousa M, Rossi A, de Lencastre H. Spread of a dominant methicillin-resistant multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) clone in Argentina. Microb Drug Resist. 1998;4:277–288. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1998.4.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coutant C, Olden D, Bell J, Turnidge J D. Disk diffusion interpretative criteria for fusidic acid susceptibility testing of staphylococci by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards methods. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;25:9–13. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(96)00070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Lencastre H, Couto I, Santos I, Melo-Cristino J, Torres-Pereira A, Tomasz A. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease in a Portuguese hospital: characterization of clonal types by a combination of DNA typing methods. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:64–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02026129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Lencastre H, de Lencastre A, Tomasz A. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates recovered from a New York City hospital: analysis by molecular fingerprinting techniques. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2121–2124. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2121-2124.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Lencastre H, Severina E P, Milch H, Konkoly Thege M, Tomasz A. Wide geographic distribution of a unique methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone in Hungarian hospitals. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1997;3:289–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Lencastre H, Severina E P, Roberts R B, Kreiswirth B N, Tomasz A BARG Initiative Pilot Study Group. Testing the efficacy of a molecular surveillance network: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VREF) genotypes in six hospitals in the metropolitan New York City area. Microb Drug Resist. 1996;2:343–351. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolzani L, Tonin E, Lagatolla C, Monti-Bragadin C. Typing of Staphylococcus aureus by amplification of the 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;119:167–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dominguez M A, de Lencastre H, Liñares J, Tomasz A. Spread and maintenance of a dominant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) clone during an outbreak of MRSA disease in a Spanish hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2081–2087. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.9.2081-2087.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiramatsu K. Molecular evolution of MRSA. Microbiol Immunol. 1995;39:531–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb02239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreiswirth B, Kornblum J, Arbeit R D, Eisner W, Maslow J, McGeer A, Low D E, Novick R. Evidence for a clonal origin of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 1993;259:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.8093647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lesky T, Oliveira D, Trzcinski K, Santos Sanches I, Aires de Sousa M, Hryniewicz W, de Lencastre H. Clonal distribution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Poland. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3532–3539. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3532-3539.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maslow J N, Mulligan M E, Arbeit R D. Molecular epidemiology: application of contemporary techniques to the typing of microorganisms. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:153–164. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mato R, Santos Sanches I, Venditti M, Platt D J, Brown A, de Lencastre H. Spread of the multiresistant Iberian clone of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) to Italy and Scotland. Microb Drug Resist. 1998;4:107–112. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1998.4.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murakami K, Minamide W, Wada K, Nakamura E, Teraoka H, Watanabe S. Identification of methicillin-resistant strains of staphylococci by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2240–2244. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2240-2244.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliveira D, Santos Sanches I, Mato R, Tamayo M, Ribeiro G, Costa D, de Lencastre H. Virtually all methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections in the largest Portuguese teaching hospital are caused by two internationally spread multiresistant strains: the “Iberian” and the “Brazilian” clones of MRSA. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1998;4:373–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1998.tb00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Palacio, R., et al. Unpublished results.

- 20.Prevost G, Jaulhac B, Piemont Y. DNA fingerprinting by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis is more effective than ribotyping in distinguishing among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:967–973. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.4.967-973.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts R B, Tennenberg A M, Eisner W, Hargrave J, Drusin L M, Yurt R, Kreiswirth B N. Outbreak in a New York City teaching hospital caused by the Iberian epidemic clone of MRSA. Microb Drug Resist. 1998;4:175–183. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1998.4.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts R B, de Lencastre A, Eisner W, Severina E, Shopsin B, Kreiswirth B N, Tomasz A the MRSA Collaborative Study Group. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in twelve New York hospitals. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:164–171. doi: 10.1086/515610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sá-Leão R, Santos Sanches I, Dias D, Peres I, Barros R M, de Lencastre H. Detection of an archaic clone of Staphylococcus aureus with low level resistance to methicillin in a pediatric hospital in Portugal and in international samples: relics of a formerly widely disseminated strain? J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1913–1920. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1913-1920.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanches I S, Aires de Sousa M, Cleto L, Baeta de Campos M, de Lencastre H. Tracing the origin of an outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in a Portuguese hospital by molecular fingerprinting methods. Microb Drug Resist. 1995;2:319–329. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanches I S, Ramirez M, Troni H, Abecassis M, Padua M, Tomasz A, de Lencastre H. Evidence for the geographic spread of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone between Portugal and Spain. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1243–1246. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1243-1246.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanches I S, Leão R S, Bonfim I, Oliveira D, Mato R, Aires de Sousa M, Brito Avô A, Saldanha J, Pereira A, Olim G A, de Lencastre H. Program and abstracts of the 20th International Congress of Chemotherapy. 1997. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant staphylococci among healthy carriers in Portugal, abstr. 4317. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saulnier P, Bourneix C, Prevost G, Andremont A. Random amplified polymorphic DNA assay is less discriminant than pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for typing strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:982–985. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.4.982-985.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmitz F J, Steiert M, Tichy H V, Hofmann B, Verhoef J, Heinz H P, Kohrer K, Jones M E. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from Dusseldorf by six genotypic methods. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:341–351. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-4-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Struelens M J, Deplano A, Godard C, Maes N, Serruys E. Epidemiologic typing and delineation of genetic relatedness of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by macrorestriction analysis of genomic DNA by using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 1992;92:377–391. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.10.2599-2605.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teixeira L, Resende C A, Ormonde L R, Rosenbaum R, Figueiredo A M S, de Lencastre H, Tomasz A. Geographic spread of epidemic multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus clone in Brazil. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2400–2404. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2400-2404.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tenover F C, Arbeit R, Archer G, Biddle J, Byrne S, Goering R, Hancock G, Hébert G A, Hill B, Hollis R, Jarvis W R, Kreiswirth B, Eisner W, Maslow J, McDougal L K, Miller J M, Mulligan M, Pfaller M A. Comparison of traditional and molecular methods of typing isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:407–415. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.407-415.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Michelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toma E, Barriault D. Antimicrobial activity testing of fusidic acid and disk diffusion susceptibility testing criteria for gram-positive cocci. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1712–1715. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1712-1715.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urbaskova P, Schindler J. Antibiotic resistance of bacteria. Prague, Czech Republic: Czech Republic National Reference Laboratory, National Institute of Public Health; 1994. pp. 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voss A, Milatovic D, Wallrauch-Schwartz C, Rosdahl V T, Braveny I. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Europe. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:50–55. doi: 10.1007/BF02026127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]