Summary

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major human pathogen that must adapt to unique nutritional environments in several host niches. The pneumococcus can metabolize a range of carbohydrates that feed into glycolysis ending in pyruvate, which is catabolized by several enzymes. We investigated how the pneumococcus utilizes these enzymes to metabolize different carbohydrates and how this impacts survival in the host. Loss of ldh decreased bacterial burden in the nasopharynx and enhanced bacteremia in mice. Loss of spxB, pdhC, or pfl2 decreased bacteremia and increased host survival. In glucose or galactose, loss of ldh increased capsule production, whereas loss of spxB and pdhC reduced capsule production. The pfl2 mutant exhibited reduced capsule production only in galactose. In glucose, pyruvate was metabolized primarily by LDH to generate lactate and NAD+ and by SpxB and PDHc to generate acetyl-CoA. In galactose, pyruvate metabolism was shunted towards acetyl-CoA production. The majority of acetyl-CoA generated by PFL was used to regenerate NAD+ with a subset used in capsule production, while the acetyl-CoA generated by SpxB and PDHc was utilized primarily for capsule biosynthesis. These data suggest that the pneumococcus can alter flux of pyruvate metabolism dependent on the carbohydrate present to succeed in distinct host niches.

Keywords: Streptococcus pneumoniae, capsule production, carbohydrate metabolism, pyruvate, virulence

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major human pathogen that survives in several host niches. While the pneumococcus can colonize the nasopharynx asymptomatically, translocation from the nasal passage to other host tissues can manifest into a variety of diseases, including pneumonia, otitis media, sinusitis, and meningitis (Henriques-Normark & Tuomanen, 2013). S. pneumoniae cannot perform aerobic respiration as it lacks both the respiratory electron transport chain and a complete tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (Hoskins et al., 2001). As such, it is reliant upon fermentation to generate the energy required for survival and replication. While it is somewhat limited in the pathways to generate ATP, the pneumococcus, unlike many other respiratory pathogens, can metabolize a diverse range (>30) of carbohydrates and complex glycans (Hobbs, Pluvinage, & Boraston, 2018). This ability to catabolize a variety of sugars provides the pneumococcus with an advantage to survive in distinct host niches with different prevailing carbohydrates, such as the mucosal lining glycans found in the nasopharynx or free glucose present in the bloodstream. The ability of S. pneumoniae to transport and use these carbohydrates is directly tied to its virulence potential (Chen et al., 2007; Hardy, Caimano, & Yother, 2000; Hava & Camilli, 2002; Paixao, Oliveiraet, et al., 2015). Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of how the pneumococcus metabolizes these different carbohydrates will provide insight into the strategies employed by the pneumococcus to succeed in disparate host niches.

Many of the carbohydrates catabolized by S. pneumoniae feed directly into the glycolytic pathway. In glycolysis, glucose and many other carbohydrates are converted to pyruvate. Pyruvate can then be metabolized in a homolactic or mixed-acid fermentation fashion via several enzymes—a branched metabolic pathway termed the pyruvate node (Cheng et al., 2018). In homolactic fermentation, pyruvate is primarily converted to lactate via lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), restoring NAD+, which is necessary for glycolysis. When glucose concentration diminishes and lactate levels increase, lactate oxidase (LctO) converts lactate to pyruvate, generating hydrogen peroxide in the process. During mixed-acid fermentation, pyruvate is catabolized to lactate, along with several other end products that are excreted (e.g. formate, ethanol, hydrogen peroxide, and acetate) or used in downstream processes (e.g. acetyl-phosphate, acetyl-CoA, and NADH). Both pyruvate formate lyase (PFL) and the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc) catabolize pyruvate into acetyl-CoA; however, only PFL generates formate as well. Pyruvate oxidase (SpxB) converts pyruvate to acetyl-phosphate, which can be converted to acetyl-CoA via phosphotransacetylase (PTA) in a reversible manner. Acetyl-CoA can be further catabolized to acetate via acetate kinase, generating ATP, or can be used in other processes, including acetylation of capsular polysaccharides. Hydrogen peroxide is also generated from SpxB enzymatic activity.

Although the genes encoding these enzymes are present in the pneumococcal genome, the activity of each enzyme under different nutritional environments is debated. Prior studies have indicated that LDH is the primary active enzyme when cells are grown in glucose (Gaspar, Al-Bayati, Andrew, Neves, & Yesilkaya, 2014) and that PFL is the primary active enzyme when cells are grown in galactose (Al-Bayati et al., 2017; Yesilkaya et al., 2009). Other studies have demonstrated activities for PDHc when cells are grown in glucose or galactose (Lisher et al., 2017; Smith, Roche, Trombe, Briles, & Hakansson, 2002) and for LctO and SpxB when cells are grown in glucose (Carvalho et al., 2013; Lisher et al., 2017; Taniai et al., 2008) but did not address the activity of LctO and SpxB during growth in galactose. While disruptions in the pyruvate node affect pneumococcal metabolism, less is understood about how these disruptions affect adaptation and survival of the pneumococcus in the distinct nutrient environments associated with host niches. S. pneumoniae has reduced survival in the blood and nasopharynx with loss of PFL (Yesilkaya et al., 2009) and SpxB (Echlin et al., 2016; Orihuela, Gao, Francis, Yu, & Tuomanen, 2004; Ramos-Montanez et al., 2008; Regev-Yochay, Trzcinski, Thompson, Lipsitch, & Malley, 2007). The pneumococcus also has reduced survival in the blood with loss of LDH (Gaspar et al., 2014) and PDHc subunit E3 (Smith et al., 2002); the contribution of these enzymes to nasopharyngeal colonization was not determined. In addition, the role these enzymes play in adaptation and survival in the host may be strain dependent, as is the case for SpxB (Echlin et al., 2016).

Loss of many of the enzymes in the pyruvate node can alter pneumococcal metabolism and virulence. However, a systematic investigation of the role each enzyme plays in carbohydrate metabolism and how this affects pneumococcal colonization and virulence would afford a better understanding of how these enzymes work together to best take advantage of available nutrients in distinct host niches. Here, we determined the effect of disruption of individual enzymes in the pyruvate node on pneumococcal pathogenesis and adaptation to a host niche, resulting from altered metabolism of glucose or galactose.

Results

Metabolic flexibility is required for pneumococcal virulence

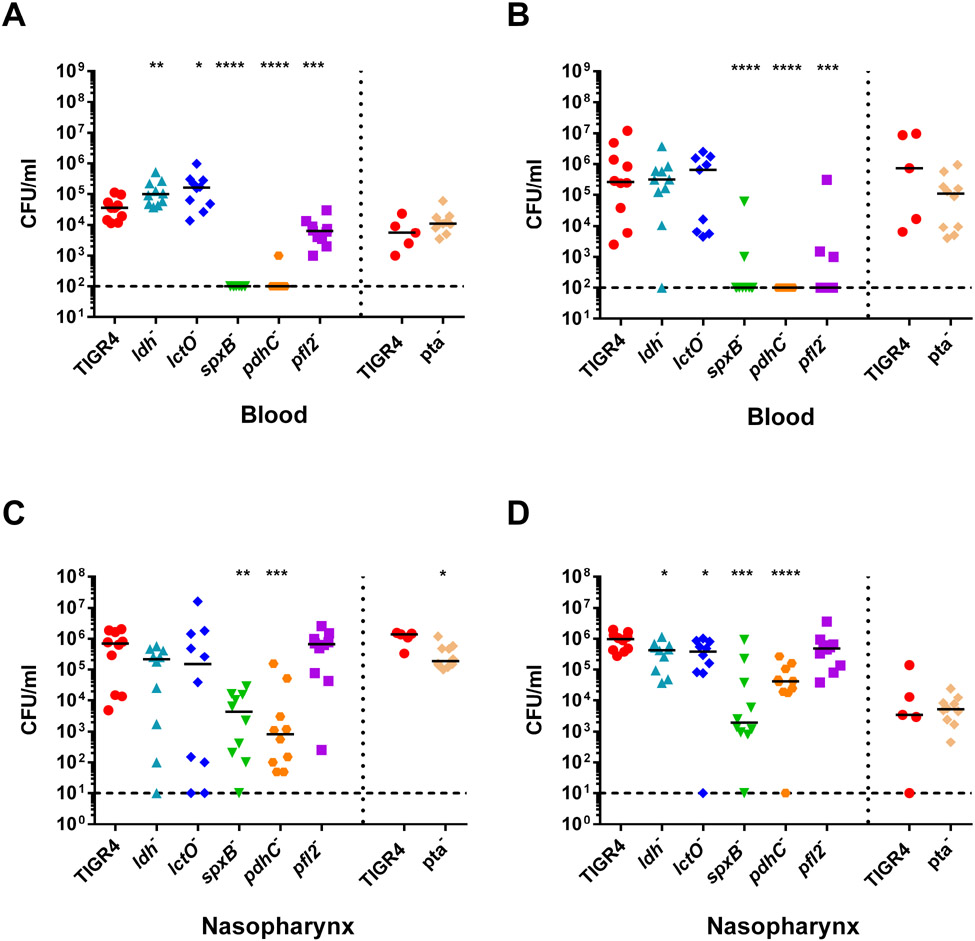

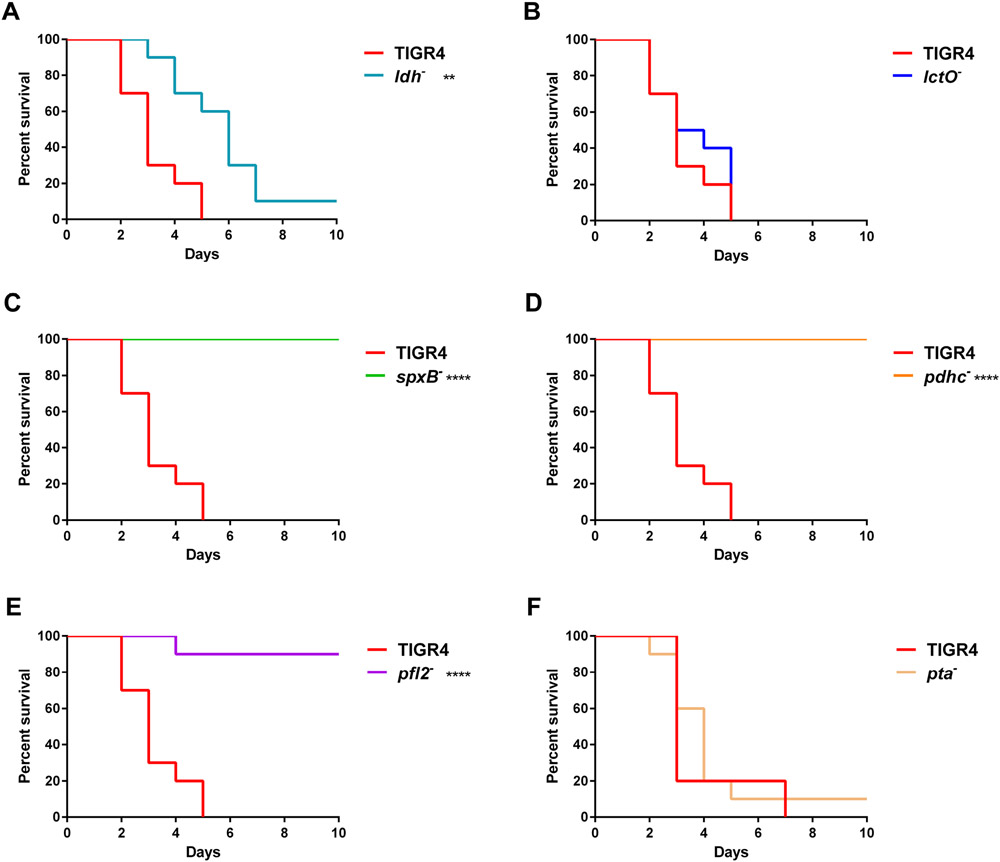

To explore the role of each enzyme of the pyruvate node in disparate host niches, we investigated the virulence of S. pneumoniae TIGR4 mutants with deletions of the genes encoding pyruvate node enzymes (Supplemental Fig. S1) in an intranasal infection mouse model. We generated individual gene deletions of six of the enzymes involved in pyruvate metabolism—ldh, lctO, spxB, pdhC, pfl2, and pta. Each of these enzymes convert pyruvate into different end products: lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and lactate oxidase (LctO) interchange pyruvate and lactate generating NAD+ or hydrogen peroxide, respectively; pyruvate oxidase (SpxB) converts pyruvate to acetyl-phosphate, producing hydrogen peroxide; both pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc) and pyruvate formate lyase (PFL) catabolize pyruvate to acetyl-CoA, but only PFL also yields formate; phosphotransacetylase (PTA) reversibly converts acetyl-phosphate to acetyl-CoA. Acetate kinase (AckA), which converts acetyl-phosphate to acetate, was excluded from this study because ackA deletion is unstable and leads to spontaneous mutations (Ramos-Montanez, Kazmierczak, Hentchel, & Winkler, 2010). Ethanol dehydrogenase, which generates ethanol from acetyl-CoA, was also excluded because of genetic redundancy. After 24 hours post-challenge, mice infected with ldh− and lctO− had significantly higher bacterial burden in the blood compared to mice infected with parental TIGR4 (Fig. 1A). Conversely, mice infected with spxB−, pdhC−, or pfl2− had reduced burden in the blood compared to TIGR4 at both 24- and 48-hours post-infection (Fig. 1A and B). Blood titers did not significantly differ for infection with pta−. The bacterial burden of ldh− and lctO− in the nasopharynx was reduced after 48 hours (Fig. 1D). As seen previously in infections with TIGR4 spxB− (Echlin et al., 2016), mice infected with spxB− had reduced burden in the nasopharynx. Similarly, mice infected with pdhC− had reduced burden in the nasopharynx. Interestingly, mice infected with pfl2− had similar nasopharyngeal burden to those infected with TIGR4 (Fig. 1C and D), although bacterial burden in the blood was reduced. To further characterize the effects of loss of pyruvate node enzymes on pneumococcal pathogenesis, we followed the survival of the infected mice for 10 days (Fig. 2). Mice infected with ldh− initially staved off morbidity, but ultimately succumbed to infection similar to TIGR4 infection (Fig. 2A). Mice infected with spxB−, pdhC−, and pfl2− had a significant increase in survival (Fig. 2C-E), reflecting the bacterial burden in the blood (Fig. 1). Loss of lctO (Fig. 2B) and pta (Fig. 2F) did not significantly alter mouse survival in comparison with the parental TIGR4 strain. The effect of loss of ldh and pfl2 on mouse survival were consistent with earlier reports of the S. pneumoniae D39 strain (Gaspar et al., 2014; Yesilkaya et al., 2009).

Fig. 1. Mice infected with ldh and lctO mutants had increased blood titers and mice infected with spxB, pdhC, and pfl2 mutants had reduced blood titers.

BALB/c mice were infected IN with 1 x 107 cells of TIGR4 and the ldh, lctO, spxB, pdhC, and pfl2 mutants, n=10. Mice were infected in the same manner with TIGR4, n=5, and pta−, n=10, separately. Bacterial presence in the blood (A,B) and nasopharynx (C,D) were determined at 24 hours (A,C), and 48 hours (B,D) by detection of colony forming units (CFU/mL). For each time-point of bacterial titers, mutant strains were compared to wild type using nonparametric Mann-Whitney t test; * p=0.05-0.01, ** p=0.01-0.001, *** p=0.001-0.0001, **** p<0.0001.

Fig. 2. spxB, pdhC, and pfl2 mutants were attenuated in a IN mouse model.

BALB/c mice were infected IN with 1 x 107 cells of TIGR4 and ldh− (A), lctO− (B), spxB− (C), pdhC− (D), and pfl2− (E), n=10. Mice were infected in the same manner with TIGR4, n=5, and pta−, n=10, separately (F). Survival of mice was followed for 10 days. Survival data were analyzed using the Mantel-Cox log rank test; ** p=0.01-0.001, **** p<0.0001.

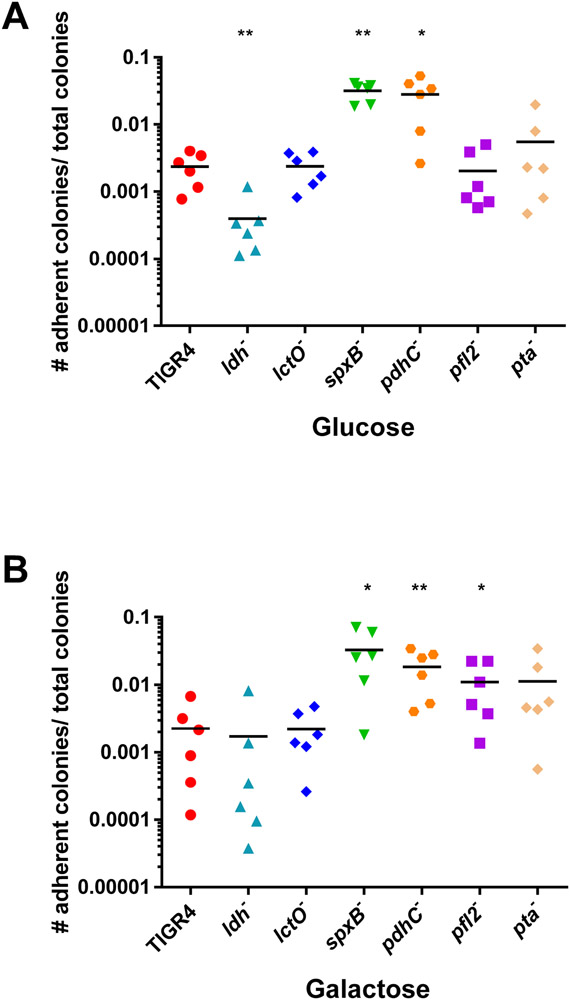

The previous results suggest that reduced or increased virulence due to loss of the pyruvate node enzymes depends on the host niche. One key difference between host niches is the bioavailability of carbohydrates. To thrive in these different environments, S. pneumoniae must be able to adapt to fluctuations in both type and amount of carbon source. Indeed, the pneumococcus can utilize at least 32 different substrates, which is essential for both pneumococcal colonization and pathogenesis (Buckwalter & King, 2012; Paixao, Oliveira, et al., 2015). We hypothesized that the observed variances in pathogenesis could be due to changes in the metabolic flux of pyruvate metabolism depending on carbohydrate availability. In order to cause invasive disease, the pneumococcus must first adhere to the nasopharynx. Free carbohydrates are limited in the nasopharynx and it is likely that the pneumococcus can metabolize the glycans in the respiratory tract (Al-Bayati et al., 2017; Buckwalter & King, 2012; Paixao, Oliveira, et al., 2015; Terra, Homer, Rao, Andrew, & Yesilkaya, 2010). To determine how availability of two of the more abundant monosaccharides in the human host affect pneumococcal adherence, we measured the ability of the pyruvate node mutants to adhere to epithelial cells in the presence of glucose or galactose (Fig. 3). The ldh mutant had reduced adherence compared to TIGR4 only in glucose. While the spxB and pdhC mutants had increased adherence when either glucose or galactose was present, the pfl2 mutant only had increased adherence in galactose.

Fig 3. Loss of ldh in glucose reduced adherence, while loss of pfl2 in galactose and loss of spxB and pdhC in both carbohydrates increased adherence.

S. pneumoniae TIGR4 and each of the pyruvate node mutants-ldh, lctO, spxB, pdhC, pfl2, and pta- were grown in media with glucose (A) or galactose (B) as the sole carbon source and adherence to A549 epithelial cells was determined. Reported values are calculated as the number of adherent bacteria per the total number of bacterial cells present at the time of plating. Each strain was measured in duplicate, with three biological replicates. Mutants were compared to TIGR4 using nonparametric Mann-Whitney t test; * p=0.05-0.01, ** p=0.01-0.001. P= 0.5587 for TIGR4 in galactose compared to TIGR4 in glucose.

These results suggest that exploitation of the different pathways of pyruvate metabolism in the presence of different carbohydrates is critical for pneumococcal disease progression. LDH and LctO may play a role in restricting translocation from the nasal passages, as loss of ldh− and lctO− resulted in increased bacterial blood titers, reduced burden in the nasal passage, and reduced adherence to epithelial cells when glucose was present. Conversely, SpxB, PDHc, and PFL were factors contributing to pneumococcal virulence since all three had reduced bacterial burden in the blood. It is likely that the attenuation resulting from loss of these three enzymes occurs through different mechanisms as the bacterial burden in the nasal passage of pfl2− remained similar to that of TIGR4 but was greatly reduced for both spxB− and pdhC−. Indeed, loss of pfl2 resulted in increased adherence to epithelial cells only in the presence of galactose, while loss of spxB and pdhC altered adherence regardless of carbohydrate. Of note, the spxB and pdhC mutants demonstrated increased adherence to epithelial cells, but reduced burden in the nasal passages. An abrogation of capsule in the spxB and pdhC mutants (Echlin et al., 2016) could explain the discrepancy between adherence of the mutants in vitro and the bacterial burden in the nasal passages. It is possible that these two mutants have a heightened ability to stick to epithelial cells not embedded in a mucus layer, as seen with other unencapsulated strains (Novick et al., 2017). However, these mutants may lack the ability to progress through the mucin in the host to gain access to the epithelial receptors for long-term adherence as observed for an unencapsulated TIGR4 (Nelson et al., 2007).

Capsule production and acetyl-CoA steady-state levels in pyruvate node mutants reflect virulence phenotype

The pneumococcus has an extensive arsenal of virulence factors, including a polysaccharide capsule on the cell surface, which is involved in tissue tropism and evasion of host immune defenses. With over 90 serotypes, the saccharides comprising the capsule can vary in type, number, and linkage (Bentley et al., 2006; Geno et al., 2015). Although the capsule is required to evade phagocytic clearance by host innate immune cells, it is an energetically expensive structure to produce, using sugars that otherwise could be catabolized for ATP generation as well as sequestering other metabolites to modify those sugars (Hathaway et al., 2012). Hence, capsule biosynthesis and metabolism are intrinsically linked in pneumococcal biology.

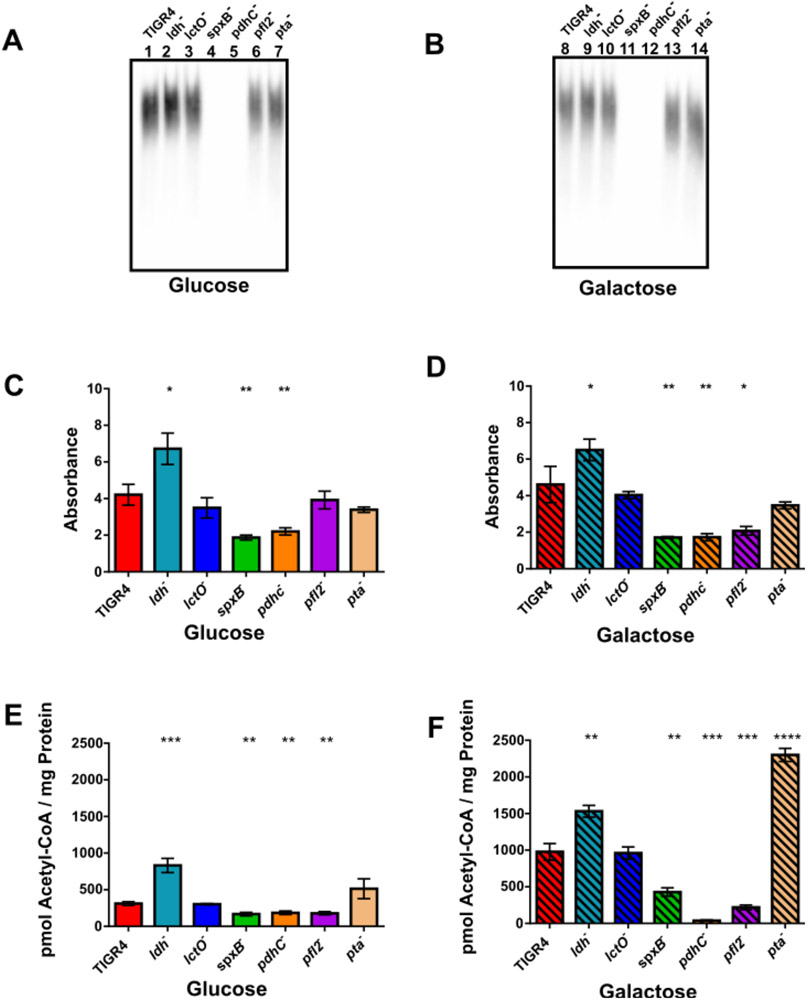

Since the polysaccharide capsule plays an important role in both colonization and survival, we next determined how availability of different carbohydrates affected the production of capsule in TIGR4 and the pyruvate node mutants. The strains were grown in media supplemented with glucose or galactose as the sole carbon source and production of capsule was measured via capsule blot and ELISA (Fig. 4). The ldh mutant exhibited increased capsule production when grown in glucose and in galactose compared to TIGR4. Loss of spxB and pdhC resulted in decreased capsule formation when the strains were grown in glucose or galactose (Fig. 4A-D). Capsule production was reduced in the pfl2 mutant, but only when grown in galactose, as observed by ELISA (Fig. 4C-D). The lctO and pta mutants exhibited no observable changes in capsule production compared to TIGR4. The increased capsule production in ldh− and reduced capsule production in spxB−, pdhC−, and pfl2− recapitulated their individual capacity to survive in blood (Fig. 1A and B).

Fig. 4. Capsule production and steady-state acetyl-CoA levels were increased in ldh− and reduced in spxB−, pdhC−, and pfl2−.

Capsule production was determined by capsule blot (A,B) and ELISA (C,D). Acetyl-CoA levels (E,F) were measured by GC/MS in triplicate. S. pneumoniae wild type (TIGR4) and each of the pyruvate node mutants-ldh, lctO, spxB, pdhC, pfl2, and pta- were grown in media with glucose (A,C,E) or galactose (B,D,F) as the sole carbon source. For ELISA, absorbance at 405 was measured for each strain in triplicate, with three biological replicates. Acetyl-CoA levels were reported as pmoles of acetyl-CoA per mg of cellular protein. Mutants were compared to the wild type using unpaired parametric t test; * p=0.05-0.01, ** p=0.01-0.001, *** p=0.001-0.0001, **** p<0.0001. For ELISA, there was no significant difference between TIGR4 grown in galactose compared to growth in glucose. For acetyl-CoA, P= 0.0006 for TIGR4 in galactose compared to TIGR4 in glucose.

The quantity of capsule production is linked to acetyl-CoA availability in type 4 serotypes (Echlin et al., 2016). Because acetyl-CoA is a product of several pyruvate node enzymes, we hypothesized that acetyl-CoA levels are altered in the pyruvate node mutants. To determine this, strains were grown in either glucose or galactose as the sole carbon source and steady-state acetyl-CoA levels were determined by mass spectrometry (Fig. 4E and F). TIGR4 exhibited greater acetyl-CoA levels when grown in galactose than in glucose (Supplemental Fig. S2A), suggesting that more pyruvate is converted to acetyl-CoA under growth in galactose than in glucose. Loss of ldh significantly increased acetyl-CoA levels in either glucose or galactose. Conversely, acetyl-CoA levels were reduced in spxB−, pdhC−, and pfl2− in either glucose or galactose, particularly in pdhC− and pfl2− grown in galactose.

These data suggest that, under glucose, LDH plays a major role in utilizing pyruvate, reducing the amount available for use by SpxB, PDHc, and PFL that would generate acetyl-CoA. As loss of spxB, pdhC, and pfl2 all reduced acetyl-CoA levels to a similar degree, it is possible that, in glucose, these enzymes equally utilize the remaining pyruvate. Since more pyruvate was converted to acetyl-CoA in galactose compared to glucose, LDH likely plays less of a role under galactose metabolism and the increased acetyl-CoA is generated through SpxB, PDHc, and PFL; however, the contribution of each of these enzymes is unequal. Of note is the observation that acetyl-CoA was greatly increased with loss of pta when galactose was the sole carbon source. Since the reaction catalyzed by pta is reversible, the elevated level of acetyl-CoA in pta− could be due to changes in enzyme kinetics between its two substrates (Pelroy & Whiteley, 1972). The pattern of acetyl-CoA levels was similar to that of capsule production in ldh−, spxB−, and pdhC− (Fig. 4A-D), where both acetyl-CoA levels and capsule production were markedly increased in ldh− and reduced in spxB− and pdhC− when grown in glucose and in galactose compared to TIGR4. Interestingly, while acetyl-CoA was reduced in pfl2− in glucose and in galactose (Fig. 4E-F), a defect in capsule production only occurred under growth in galactose (Fig. 4D). Since, acetyl-CoA is a key metabolic intermediate of several cellular macromolecules (Krivoruchko, Zhang, Siewers, Chen, & Nielsen, 2015), it is possible that downstream metabolic shunting of acetyl-CoA generated by SpxB, PDHc, and PFL is not equal.

These data suggest that pneumococcal virulence is tied to changes in pyruvate metabolism flux through different pyruvate node enzymes based on the nutrient availability of the host niche. The attenuation of spxB−, pdhC−, and pfl2− and the heightened bacterial burden in the blood of ldh− were associated with altered capsule production, which was reflected by changes in acetyl-CoA levels and was, in turn, dependent on the carbohydrate source that feeds into the pyruvate node.

Metabolism of carbon sources through glycolysis is influenced by pyruvate node enzymes

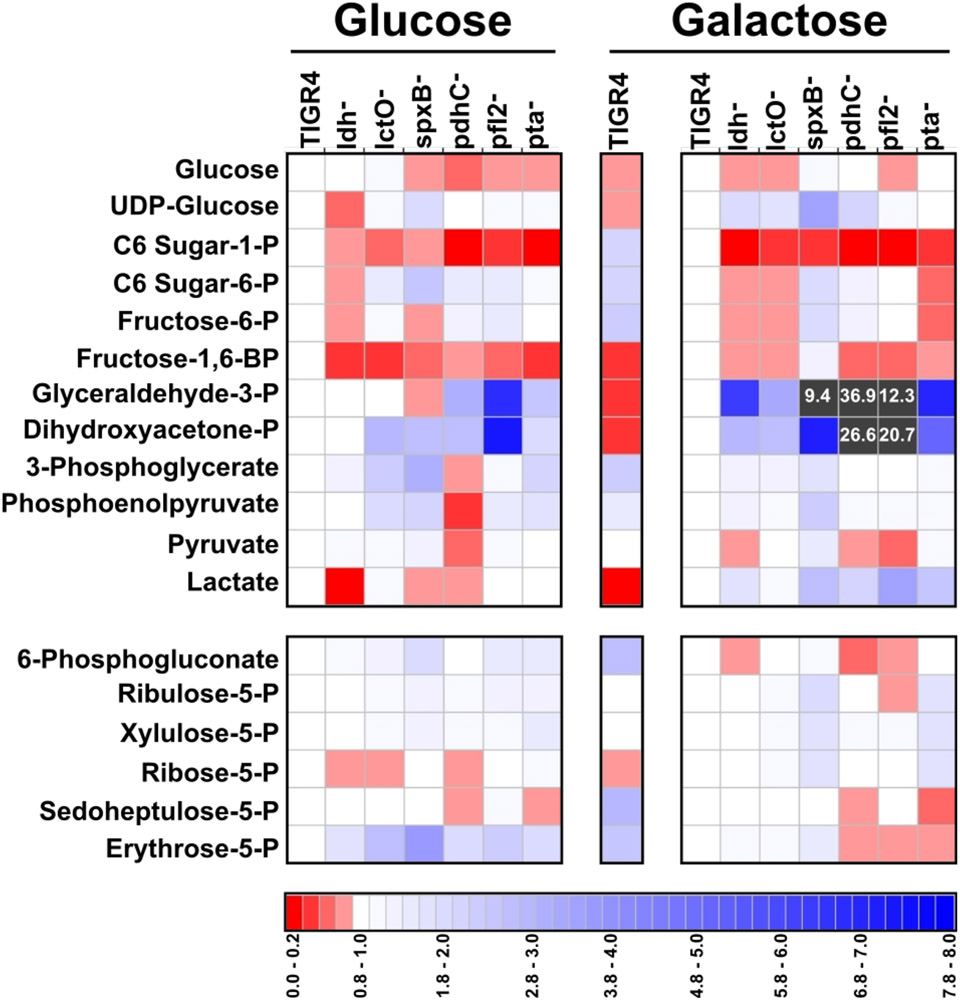

We next explored the mechanism by which acetyl-CoA levels were altered, depending on carbon availability and the enzymes active in the pyruvate node. Galactose metabolism is similar to glucose metabolism in that both carbon sources are catabolized through glycolysis. However, galactose can enter glycolysis either at the beginning (i.e. Leloir pathway) or at the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP)/dihydroxyacetone-phosphate (DHAP) intermediate (i.e. tagatose-6-phosphate pathway) (Neves et al., 2010; Thomas, Turner, & Crow, 1980). GAP and DHAP are isomers generated from fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP; a metabolic product of glucose or galactose via the Leloir pathway) or from tagatose-diphosphate (i.e. galactose metabolism via tagatose-6-phosphate pathway). Moreover, GAP and DHAP can be interconverted via an aldolase. To determine whether changes in acetyl-CoA levels were influenced by shifts in glycolysis, we investigated how specific carbon sources and loss of pyruvate node enzymes affect glycolytic metabolites (Fig. 5 and Supplemental Fig. S3 and File S1). FBP, GAP, and DHAP were moderately reduced in TIGR4 grown in galactose compared to growth in glucose (Fig. 5, center panel). This result suggests that early galactose catabolism occurs at a slower rate than does glucose catabolism, possibly because galactose catabolism is split through both pathways. Indeed, previous reports are in agreement with this proposed interpretation (Carvalho, Kloosterman, Kuipers, & Neves, 2011; Paixao, Oliveira, et al., 2015). In the pyruvate node mutants, the relative abundance of C6 sugar-1-phosphate, FBP, GAP, and DHAP were markedly altered. C6 sugar-1-phosphate and FBP decreased in all deletion mutants grown in glucose and in galactose, particularly in ldh−, lctO−, and pta− in glucose (Fig. 5, left panel). GAP and DHAP were greatly increased in galactose in the mutants, particularly in spxB−, pdhC−, and pfl2− (Fig. 5, right panel). As GAP/DHAP were reduced in TIGR4 grown in galactose compared to glucose, GAP/DHAP levels in the deletion mutants grown in galactose resembled that of TIGR4 growth in glucose rather than in galactose. This result indicates that SpxB, PDHc, and PFL play a role in the rate of galactose catabolism or the flux of galactose between the Leloir and tagatose-6 phosphate pathways.

Figure 5. Loss of pyruvate node enzymes impacted the levels of key glycolytic metabolites.

Streptococcus pneumoniae TIGR4 and each of the pyruvate node mutants—ldh, lctO, spxB, pdhC, pfl2, and pta- were grown in media with glucose or galactose as the sole carbon source and intracellular metabolites were measured by GC/MS in triplicate. Values of each metabolite were normalized back to total cellular protein. For each metabolite, the ratio of the mutant to TIGR4 grown in either glucose or galactose was plotted as a heat map, where ratios of less than 1 are depicted as darkening shades of red and ratios of greater than 1 are depicted as darkening shades of blue. Ratios that were greater than 8 are depicted as grey squares and the value is indicated. The center vertical bar represents the ratio of TIGR4 grown in galactose to TIGR4 grown in glucose. Metabolites were grouped by pathway: glycolysis (top) and pentose phosphate pathway (bottom). “P” in the metabolite name represents phosphate. “C6” represents six-carbon sugars, including glucose and galactose. For complete relative abundance values, see File S1.

We observed metabolic changes in pathways other than glycolysis in the pyruvate node mutants (Supplemental Fig. S3). High-energy phosphate donors were reduced in all the deletion mutants grown in galactose, particularly in spxB−, pdhC−, and pfl2− (Supplemental Fig. S3A). The availability of amino acids was slightly reduced, particularly for arginine and tyrosine (Supplemental Fig. S3B), and several derivative metabolites were greatly increased, including citrate in pdhC− in glucose, carbamoyl-l-aspartate in spxB− in galactose, and flavin mononucleotide in pfl2− in galactose (Supplemental Fig. S3C).

The markedly increased abundance of GAP/DHAP in spxB−, pdhC−, and pfl2− grown in galactose (Fig. 5, right panel) were inversely proportional to the decreased levels of acetyl-CoA (Fig. 4F). This indicates a link between GAP/DHAP and acetyl-CoA levels, and, thereby, capsule production and virulence. As GAP/DHAP are the substrates for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, it is possible that flux between a homolactic and a mixed-acid fermentation is determined through regulation of this enzyme; this regulation may occur by a multitude of means, including allosteric inhibition by other glycolytic metabolites (i.e. NAD+, FBP) (Neves, Pool, Kok, Kuipers, & Santos, 2005; Neves et al., 2002; Paixao, Caldas, et al., 2015), acetylation (Liu et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2010), coAlation (Tsuchiya et al., 2018), or transcriptional (Carvalho et al., 2011). It is unclear if changes in the glycolytic flux in the pyruvate node mutants led to changes in acetyl-CoA levels or whether the altered acetyl-CoA levels fed back into glycolytic flux.

Flux through the pyruvate node is controlled by enzyme activity based on nutrient availability

It is possible that the changes in glycolytic metabolites resulted from altered production of acetyl-CoA and other end products and that these end products were influenced by carbohydrate availability and the activity of pyruvate node enzymes. Indeed, growth of the pneumococcus in different carbon sources can change the metabolic end products produced (Al-Bayati et al., 2017; Paixao, Oliveira, et al., 2015; Yesilkaya et al., 2009). To gain a better understanding of the flux of pyruvate metabolism in the pyruvate node mutants grown in different carbohydrates, we determined the concentration of metabolites generated through the enzymatic activity of the pyruvate node enzymes during pneumococcal growth in glucose or in galactose.

Several intracellular metabolites other than acetyl-CoA are generated by pyruvate metabolism, including hydrogen peroxide through the actions of SpxB and LctO (Pericone, Park, Imlay, & Weiser, 2003; Taniai et al., 2008). We determined the extracellular hydrogen peroxide levels produced by the pyruvate node mutants grown in glucose or galactose (Supplemental Fig. S4). In glucose, hydrogen peroxide was reduced in ldh− and lctO− and even more so in spxB−. In galactose, only loss of spxB resulted in reduced hydrogen peroxide production. Hydrogen peroxide production in TIGR4 grown in glucose did not significantly differ from that grown in galactose (Supplemental Fig. S2B). These data suggest that both SpxB and LctO are active in glucose, but only SpxB is active when galactose is the sole carbon source. This is most likely due to reduced activity of LDH when TIGR4 is grown in galactose, which would result in a decreased amount of lactate (the substrate of LctO). Similarly, the reduced hydrogen peroxide observed in ldh− grown in glucose most likely stems from reduced LctO activity.

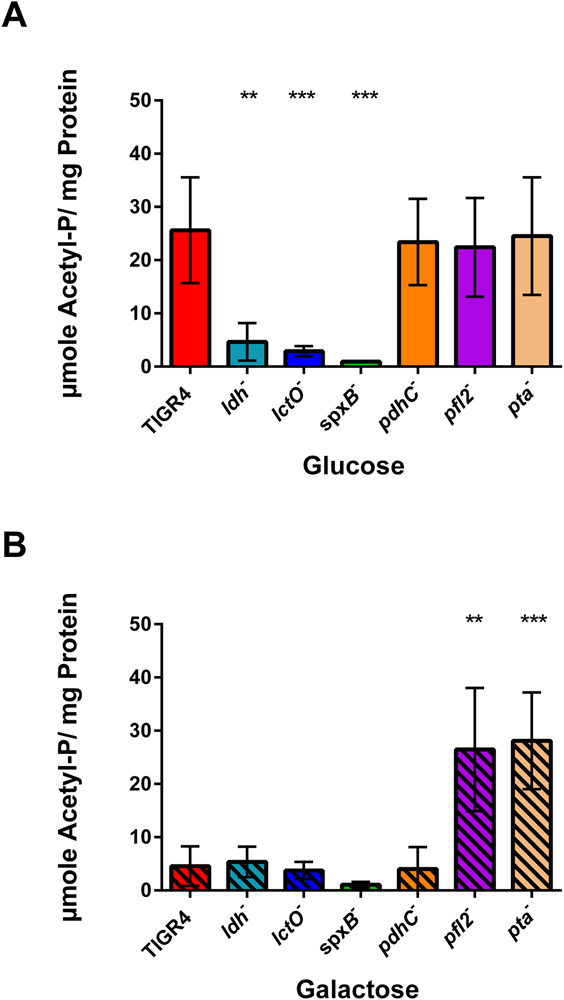

Acetyl-phosphate is another intracellular metabolite generated by the pyruvate node enzymes—namely, SpxB and PTA. We measured acetyl-phosphate levels in TIGR4 and in the pyruvate node mutants grown in glucose or galactose. Acetyl-phosphate levels were greatly decreased in TIGR4 grown in galactose, as compared to that of TIGR4 grown in glucose (Supplemental Fig. S2C). The ldh and lctO mutants had reduced acetyl-phosphate levels in glucose, but not in galactose, when compared to that of TIGR4 (Fig. 6). The spxB mutant had significantly reduced acetyl-phosphate levels in glucose and, to a lesser extent, in galactose (P = 0.07), which was observed previously in other strains (Marx, Meiers, & Bruckner, 2014; Pericone et al., 2003; Ramos-Montanez et al., 2010; Ramos-Montanez et al., 2008). In contrast, loss of pfl2 resulted in greatly increased levels of acetyl-phosphate in galactose (Fig. 6B). Intriguingly, acetyl-phosphate levels inversely mirrored acetyl-CoA levels. In ldh− grown in glucose, acetyl-phosphate was greatly reduced (Fig. 6A), while acetyl-CoA was increased (Fig. 4E). Conversely, acetyl-phosphate was markedly increased in pfl2− in galactose (Fig. 6B), yet acetyl-CoA was decreased (Fig. 4F). Because acetyl-phosphate is generated by SpxB activity, loss of spxB resulted in decreased acetyl-phosphate and acetyl-CoA in either glucose or galactose. Of note, both acetyl-phosphate and acetyl-CoA levels were elevated in pta− grown in galactose. This may be due to the inability of the pneumococcus to adapt to the requirements of acetyl-phosphate or acetyl-CoA, suggesting that the direction and magnitude of PTA to convert acetyl-phosphate to acetyl-CoA and vice versa can change according to carbohydrate and substrate availability (Lawrence & Ferry, 2006; Shi, Stansbury, & Kuzminov, 2005).

Figure 6. Acetyl-phosphate levels inversely mirrored acetyl-CoA levels in pyruvate node mutants.

S. pneumoniae TIGR4 and each of the pyruvate node mutants-ldh, lctO, spxB, pdhC, pfl2, and pta- were grown in media with glucose (A) or galactose (B) as the sole carbon source and acetyl-phosphate levels were measured by Cell Titer Glo Assays in duplicate, with three biological repeats. Levels were reported as μmoles of acetyl-phosphate per mg of cellular protein. Mutants were compared to TIGR4 in the same growth condition using unpaired parametric t test; ** p=0.01-0.001, *** p=0.001-0.0001, **** p<0.0001. p= 0.0022 for TIGR4 in galactose compared to TIGR4 in glucose.

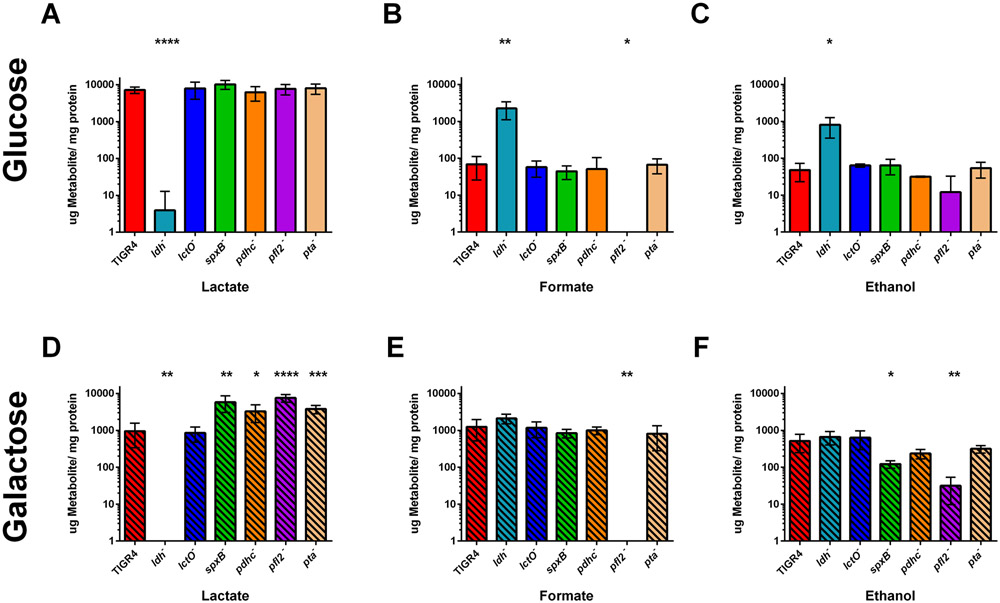

We next measured the other end products of pyruvate metabolism from the supernatant, as these metabolites are excreted. In glucose, a shift in end products was observed with loss of ldh, as compared with TIGR4, in which a primarily lactate fermentation changed to mixed-acid fermentation, generating lactate, formate, and ethanol as end products (Fig. 7A-C). Moreover, a slight increase in lactate occurred with loss of spxB (P= 0.062). A significant decrease in formate and slight decrease in ethanol (P=0.1) occurred with loss of pfl2. No significant changes were noted for the other deletion mutants grown in glucose. These results suggest that, in glucose, LDH is the primary enzyme that metabolizes pyruvate, with some pyruvate being available for utilization by SpxB and PFL. This is consistent with acetyl-CoA levels in the pyruvate node mutants (Fig. 4).

Figure 7. Loss of pyruvate node enzymes shifted flux from homolactic to mixed acid fermentation.

Streptococcus pneumoniae TIGR4 and each of the pyruvate node mutants—ldh, lctO, spxB, pdhC, pfl2, and pta- were grown in media with glucose (A-C) or galactose (D-F) as the sole carbon source and metabolites—including lactate (A,D) formate (B,E), and ethanol (C,F)—secreted by S. pneumoniae were determined using Megazyme kits. All three metabolites were measured concurrently, and the experiment was repeated five times. Levels were reported as μg of metabolite per mg of cellular protein. Mutants were compared to TIGR4 for each growth condition using unpaired parametric t test; * p=0.05-0.01, ** p=0.01-0.001, *** p=0.001-0.0001, **** p<0.0001.

When grown in galactose, TIGR4 metabolized pyruvate in a mixed-acid fermentation, generating similar amounts of lactate, formate, and ethanol—in contrast with homolactic fermentation observed in glucose (Supplemental Fig. S2D). Loss of ldh abolished lactate production and slightly increased formate production (P = 0.068) (Fig. 7D and E). In galactose, deletion of spxB, pdhC, pfl2, and pta greatly increased lactate levels, as compared with TIGR4, to levels similar to that of TIGR4 grown in glucose. Loss of pfl2 also abolished formate production. Ethanol levels were reduced with loss of spxB and pdhC (P = 0.134), although not to the extent as with loss of pfl2 (Fig. 7F). These changes in metabolic flux in the ldh− and pfl2− mutants are consistent with previous studies in S. pneumoniae strain D39 (Gaspar et al., 2014; Yesilkaya et al., 2009).

Discussion

Taken together, these data provide evidence that the flux of pyruvate metabolism via nutrient availability and activity of the pyruvate node enzymes can alter the progression of pneumococcal invasive disease (Supplemental Fig. S5). In galactose, loss of ldh shifts the paradigm to resemble galactose metabolism, whereby pyruvate is converted to more formate and acetyl-CoA, resulting in increased capsule production, decreased adhesion and nasal titers, and increased blood titers. Loss of spxB and pdhC resulted in more lactate produced and slightly reduced ethanol, while dramatically reducing acetyl-CoA and capsule production in either glucose or galactose, leading to increased adhesion to cells without mucin and decreased nasal and blood titers. Loss of pfl2 significantly reduced ethanol production, while slightly reducing capsule production in galactose. This suggests that, in glucose, the pneumococcus metabolizes pyruvate to lactate primarily via LDH, regenerating the NAD+ necessary for continuation of glycolysis, with some pyruvate converted to acetyl-CoA via SpxB and PDHc for utilization in other cellular components, including capsule production. Galactose metabolism occurs at a slower rate and the pneumococcus converts pyruvate to multiple end products-through LDH, SpxB, PDHc, and PFL activities. Acetyl-CoA generated by SpxB, PDHc, and PFL is either converted to ethanol to maintain redox balance by regenerating NAD+ through the secondary action of alcohol dehydrogenase or used in other downstream processes, including capsule production. It is likely that metabolic channeling occurs in that the acetyl-CoA generated through PFL is more dedicated to regenerating NAD+ and the acetyl-CoA generated from SpxB and PDHc activities is more committed to capsule production.

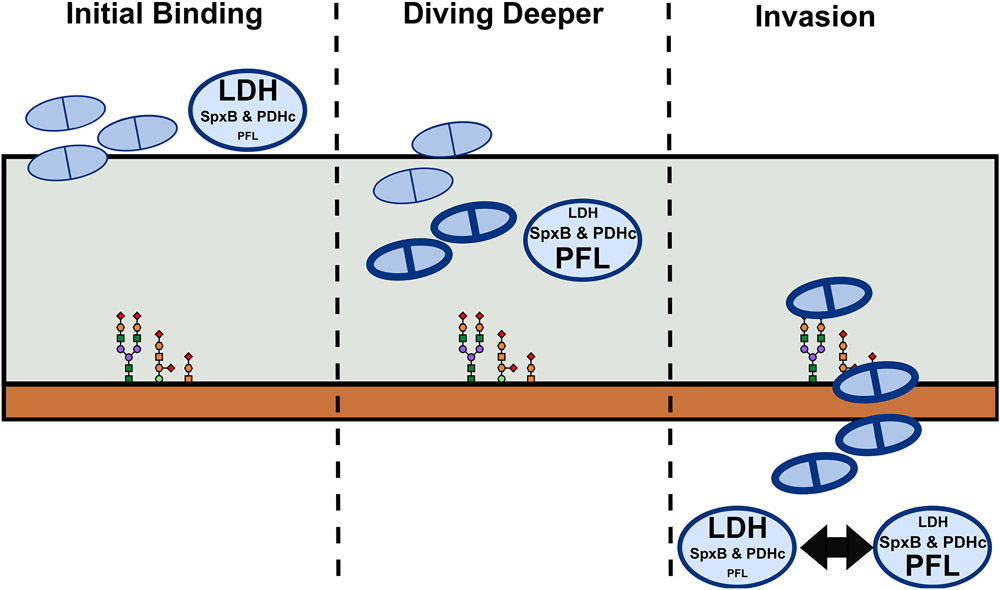

Dramatic metabolic changes occur depending on what carbohydrate is available for the pneumococcus to catabolize. Based on the changes in the steady state levels of metabolites in each of the pyruvate node mutants (Supplemental Fig. S6), we propose a model by which the pneumococcus adapts to the nutritional environment in the host niche that alters its ability to colonize or progress to invasive disease (Figure 8). The first step for pneumococcal infection is adherence to the nasal passages. As the pneumococcus contacts the mucus layer, sialidases remove the outermost sialic acid on the mucin. The pneumococcus can catabolize this sialic acid to GlcNAc, which feeds into the glycolytic pathway in a homolactic fermentation fashion (Bell et al., 2019; Marion, Burnaugh, Woodiga, & King, 2011; Paixao, Caldas, et al., 2015; Paixao, Oliveira, et al., 2015). Here, LDH would be the primary enzyme involved in pyruvate catabolism and acetyl-CoA and capsule production would be reduced, allowing for exposure of adhesins and better initial adherence (Thamadilok, Roche-Hakansson, Hakansson, & Ruhl, 2016). With the outer sialic acid cleaved away, the other sugars in the mucin are exposed. The pneumococcus senses these exposed glycans and sialidases, glycosidases, and genes involved in galactose metabolism are upregulated (Paixao, Oliveira, et al., 2015; Yesilkaya, Manco, Kadioglu, Terra, & Andrew, 2008). The cleavage of mucin sugars provides a source of nutrients and allows the pneumococcus to dive deeper into the nasal tissue (Burnaugh, Frantz, & King, 2008; Kahya, Andrew, & Yesilkaya, 2017; King, 2010). As the cells degrade more host glycans, which are laden with galactose (Blanchette et al., 2016), metabolic flux shifts from a homolactic to a mixed acid fermentation, where SpxB, and PDHc, and PFL become more active. This, in turn, generates more acetyl-CoA and capsule production, which then allows the pneumococcus to delve even deeper and develop a more stable adherence (Nelson et al., 2007). Once the pneumococcus has gained access to the epithelial layer, it can interact with host receptors through other adhesins and capsular shedding (Kietzman, Gao, Mann, Myers, & Tuomanen, 2016). This interaction then could lead to lobar pneumonia or translocation into the bloodstream (Henriques-Normark & Tuomanen, 2013; Weiser, Ferreira, & Paton, 2018). In a new host niche, the pneumococcus must adapt to a new nutritional environment. As the primary sugar available in the blood is glucose, LDH will be most active and homolactic fermentation will ensue. While this provides the pneumococcus with energy for replication, it may come at the cost of capsule production and protection against immune clearance. Thus, a balance between energy and defense must be maintained.

Figure 8. Proposed model for pneumococcal adhesion and invasion.

Large ovals next to pneumococcal cells (light blue doublets) indicate the flux of pyruvate metabolism: LDH= lactate dehydrogenase; SpxB = pyruvate oxidase; PDHc= pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; PFL= pyruvate formate lyase. Size of the text within the oval represents the level of enzyme activity.

This balance is sustained through the activities of the pyruvate node enzymes. In the nasal passage, loss of ldh shifts the metabolic flux to mixed-acid fermentation, mimicking galactose catabolism, and more acetyl-CoA and capsule is produced. This gives the mutant an advantage on traversing the mucin layer and increases the chance of translocation, which is reflected in the increased blood titers. However, in the blood, it can no longer metabolize glucose efficiently without LDH and may struggle to replicate and be cleared by the host overtime, as seen by decreased mouse lethality. With loss of spxB and pdhC, metabolism is shifted towards lactate production, thereby reducing acetyl-CoA and capsule production. Although these mutants still maintain a functional PFL and can catabolize the galactose of the mucin (as evident by production of formate when grown in galactose), the reduction of capsule prevents the spxB and pdhC mutants from traversing the mucin efficiently and makes them more prone to clearance by the immune system if they were to translocate into the blood. Additionally, it is possible that loss of the end products of SpxB (i.e. hydrogen peroxide) diminishes the ability of the pneumococcus to reside in the nasopharynx (Shenoy et al., 2017; Spellerberg et al., 1996). Converse to the ldh mutant, the pfl2 mutant has difficulty metabolizing the glycans in the nasal passage. Because some capsule is produced through the action of SpxB and PdhC, the pfl2 mutant can gain access into the mucin layer but does not catabolize galactose as efficiently. Thus, loss of pfl2 traps the pneumococcus in the mucin layer, allowing it to survive in the nasopharynx but preventing it from accessing deeper tissue sites and translocating to the bloodstream. This results in negligible effect on bacterial burden in the nasal passage but reduced burden in the blood.

These data underscore the role of central metabolism in the context of host–pathogen interactions and suggest that the complex metabolic networks of the pyruvate node play important roles in pneumococcal pathogenesis. Proper balance of pyruvate node enzymes in utilizing the available carbohydrates allows the pneumococcus to prevail in the host and to progress to invasive disease. Moreover, the ability of the pneumococcal strain to adapt its metabolic state to catabolize the galactose in the nasopharynx may be an indicator of its likelihood to progress from colonization to invasive disease.

Experimental procedures

Media and growth conditions

Streptococcus pneumoniae was grown in 5% CO2 at 37°C on tryptic soy agar (EMD Chemicals) plates supplemented with 3% sheep blood and 20 μg ml−1 neomycin, in a semi-defined media C+Y (Lacks & Hotchkiss, 1960), or in defined media C−Y supplemented with either 0.2% glucose or 0.2% galactose until mid-logarithmic phase (OD620~ 0.4) was reached. C−Y media was generated by following the protocol for C+Y media without the addition of yeast extract, glucose, or sucrose. Cultures were inoculated from frozen stocks or from freshly streaked plates. The strains used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Bacterial constructs

Deletion mutants of the genes ldh (Sp_1220), pfl2 (Sp_0459), and pta (Sp_1100) in the TIGR4 background were generated by amplifying 1 kb regions upstream and downstream of the genes by using the following primer pairs: Ldh_Up_F/Ldh_Up_R, Ldh_Down_F/Ldh_Down_R, Pfl2_Up_F/Pfl2_Up_R, Pfl2_Down_F/Pfl2_Down_R, Pta_Up_F/Pta_Up_R, and Pta_Down_F/Pta_Down_R, respectively (Supplemental Table S2). For deletion of pyruvate formate lyase, the second homolog of pfl (Sp_0459) was chosen because the first homolog may be nonfunctional (Yesilkaya et al., 2009). The upstream and downstream fragments were spliced with a spectinomycin-resistance cassette by using splicing-by-extension (SOE) PCR. To transform S. pneumoniae, the resultant PCR fragments were introduced to TIGR4 grown to OD620~0.07, along with competence stimulating peptide 2. Knockout mutants were selected on TSA blood agar plates containing 20 μg ml−1 neomycin and 150 μg ml−1 spectinomycin. The deletion mutants were confirmed by PCR to verify insertion of the cassette and deletion of the gene. Deletion mutants of the genes lctO (Sp_0715), spxB (Sp_0730), and pdhC (Sp_1163-1164) were generated in a similar manner as previously described (Echlin et al., 2016).

Mouse studies

For bacterial burden and survival studies, TIGR4 and the deletion mutants were grown to mid-logarithmic phase (OD620~0.4) in 10 ml C+Y and diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), according to a previously determined standard curve. Bacteria were enumerated on TSA blood agar plates to confirm that the correct number was used for infection. 7-week-old female BALB/c (Jackson Laboratory) were infected with S. pneumoniae via intranasal (IN) instillation of 1 × 107 bacteria in 30 μl of PBS. Mice were monitored for disease progression and were euthanized via CO2 asphyxiation. Blood was collected at 24 and 48 hours post infection via tail snip. Bacterial burden in the blood was determined by serial dilution of the blood in PBS and subsequent plating. Bacterial colonization in the nasopharynx was determined at 24 and 48 hours post infection by serially diluting nasal washes that were collected by insertion and removal of PBS (20 μl) in the nasal cavity. Bacterial titers were compared with nonparametric Mann-Whitney t tests and survival data were analyzed with Mantel-Cox log rank tests in Prism 6 (GraphPad).

Ethics statement

All experiments involving animals were performed with prior approval of and in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (St. Jude) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #538-100013). The St. Jude laboratory animal research facilities are fully accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Laboratory animals were maintained in accordance with the applicable portions of the Animal Welfare Act and the guidelines prescribed in the DHHS publication Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All mice were maintained in BSL2 facilities, and all experiments were performed while the mice were under inhaled isoflurane (2.5%) anesthesia. Mice were monitored daily for signs of infection and disease progression.

Adhesion assay

Pneumococcal adherence to A549 lung epithelial cells was determined from a modified adhesion assay (Orihuela et al., 2009). A549 cells (ATCC) were seeded to ~95% confluency (2.9 x105 cells ml−1) in 24-well tissue-culture treated plates (Costar, Corning). Cells were treated for 2 hours prior to infection with TNF-α (10 ng ml−1) in F12K media (ATCC) with 10% FBS and 20 μg ml−1 gentamicin, followed by 2x rinse with PBS. Pneumococcal strains were grown in C−Y with 0.2% glucose or 0.2% galactose until mid-logarithmic phase (OD620~0.4) was reached, except for the pdhC mutant which failed to grow beyond OD620~0.3 during the experimental timeframe. The bacterial culture was diluted 1:10 into F12K with an additional 0.2% glucose or 0.2% galactose according to the original growth media. A459 cells were infected with 1 ml of the diluted bacterial culture (1.5 x107 cells) at a MOI of ~50:1, except for the pdhC mutant (MOI of 1:1). Bacteria were allowed to adhere to A549 cells for 100 minutes, followed by 2x wash with PBS. A549 cells with adherent bacteria were detached from the well via incubation with 100 μl of 0.1% Trypsin in PBS at 37°C for 5 minutes. An additional 900 μl of PBS was added to each well and the cell solution was mixed thoroughly. Adherent bacteria were determined by serial dilution of the cell solution in PBS and subsequent plating. Of note, the final bacterial titer after the incubation period increased from the initial titer used to infect the A549 cells; this increase varied depending on the strain and the carbohydrate present (Supplemental Table S3). To account for this, we calculated the number of adherent bacteria per the total number of bacterial cells present at the time of plating, which was determined by growing strains in the same media without A549 cells alongside the adhesion wells. Each strain was measured in duplicate in each plate, with three biological replicates for each sample. The number of adherent colonies/ total bacterial cells of each mutant was compared with that of TIGR4 in each growth condition with nonparametric Mann-Whitney t tests in Prism 6 (GraphPad).

Capsule blotting

Capsule production was determined as previously described (Kietzman et al., 2016). Briefly, the TIGR4 and deletion mutant strains were grown in 10 ml of C−Y with 0.2% glucose or 0.2% galactose until mid-logarithmic phase (OD620~0.4) and then lysed with deoxycholate (DOC)/sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in PBS to disrupt cellular membranes. The total cellular protein in the lysates was determined via the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce). Proteins were then removed by incubation with proteinase K. Cell lysates were diluted to 22.5 mg ml−1 cellular protein with PBS and subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis. The samples were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane overnight by standard capillary transfer with a high-salt buffer. The membranes were probed for capsule polysaccharides by using a serotype 4 antibody (Statens Serum Institute) and an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Bio-Rad), followed by detection with an HRP chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific).

ELISA

Whole-cell bacterial ELISA was performed as a quantitative measure of capsule polysaccharide production on the bacterial surface. Strains were grown in 10 ml of C−Y with 0.2% glucose or 0.2% galactose until mid-logarithmic phase (OD620~0.4). Cells were pelleted, diluted 1:50 in coating buffer (sodium carbonate), and bound to high-binding 96-well plates (Nunc) via centrifugation. The plates were allowed to dry at room temperature overnight and then subjected to blocking buffer (10% fetal bovine serum). Samples in the wells were probed with serotype 4 antibody (Statens Serum Institute) and alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated secondary antibody (Southern Biotech), followed by detection with AP yellow ELISA substrate (Sigma). Each strain was measured in triplicate in each plate, with three biological replicates for each sample. Immunoreactivity of the deletion mutants were compared with that of TIGR4 in each growth condition by using unpaired parametric t tests with Prism 6.

Acetyl-CoA measurement

Intracellular acetyl-CoA levels were determined by mass spectrometry, as previously described (Echlin et al., 2016). The TIGR4 and deletion mutant strains were grown in 30 ml of C−Y with 0.2% glucose or 0.2% galactose until mid-logarithmic phase (OD620~0.4) was reached. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and lysed with methanol/2% acetic acid, followed by treatment with chloroform. Metabolites were extracted from the aqueous layer via application on a 2-(2-pyridyl) ethyl column and elution with 95% ethanol/50 mM ammonium formate. After drying under nitrogen, the samples were resuspended in 90% methanol/15 mM ammonium hydroxide and subjected to mass spectrometry for analysis. Mass spectrometry was performed by using a Finnigan TSQ Quantum (Thermo Electron) triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer. The instrument was operated in positive mode with single-ion monitoring (SIM) and neutral-loss scanning corresponding to the loss of the phosphoadenosine diphosphate from CoA species. The ion source parameters were as follows: spray voltage, 4,000 V; capillary temperature, 250°C; capillary offset, −35 V; sheath gas pressure, 10; and auxiliary gas pressure, 5; tube lens offset was set by infusion of the polytyrosine tuning and calibration in electrospray mode. Acquisition parameters were as follows: scan time, 0.5 s; collision energy, 30 V; peak width Q1 and Q3, 0.7 FWHM; Q2 CID gas, 0.5 mTorr; source CID, 10 V; neutral loss, 507.0 m/z; and SIM mass of 810 m/z with a scan width of 8 m/z to capture the signal from light and heavy acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA was extracted from each strain in triplicate. Acetyl-CoA levels were reported as pmoles of acetyl-CoA per mg of cellular protein. Acetyl-CoA levels of the deletion mutants were compared with those of TIGR4 in each growth condition with unpaired parametric t tests with Prism 6.

Metabolite measurements by HPLC/MS/MS

Intracellular metabolite levels were determined by HPLC/MS/MS. The TIGR4 and deletion mutant strains were grown in C−Y with 0.2% glucose or 0.2% galactose until mid-logarithmic phase (OD620~0.4) was reached. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 80% methanol. Metabolites were extracted from each strain in triplicate and were analyzed using a Shimadzu Prominence UFLC attached to a QTrap 4500 equipped with a Turbo V ion source (Sciex). Samples were injected onto an XSelect® HSS C18, 2.5 μm, 3.0 x 150 mm column using a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. Solvent A was 100 mM ammonium formate, pH 5.0 + 2% acetonitrile + 0.1% TBA, and Solvent B was 95% acetonitrile + 50 mM ammonium formate, pH 6.3 + 0.1% TBA. There were three HPLC/MS/MS programs used to analyze the metabolites.

Program 1 was the following: starting solvent mixture of 0% B, 0 to 2 min isocratic with 0% B; 2 to 12 min linear gradient to 5% B; 12 to 17 min linear gradient to 90% B; 17 to 25 min isocratic with 90% B; 25 to 27 min linear gradient to 0% B; 27 to 30 min isocratic with 0% B. The QTrap 4500 was operated in the negative mode, and the ion source parameters were: ion spray voltage, −4500 V; curtain gas, 40 psi; temperature, 500 °C; collision gas, medium; ion source gas 1, 50 psi; and ion source gas 2, 50 psi.

Program 2 was the following: starting solvent mixture of 0% B, 0 to 3 min isocratic with 0% B; 3 to 16 min linear gradient to 10% B; 16 to 21 min linear gradient to 100% B; 21 to 26 min isocratic with 100% B; 26 to 28 min linear gradient to 0% B; 28 to 30 min isocratic with 0% B. The QTrap 4500 was operated in the positive mode, and the ion source parameters were: ion spray voltage, 5500 V; curtain gas, 20 psi; temperature, 400 °C; collision gas, medium; ion source gas 1, 25 psi; and ion source gas 2, 40 psi.

Program 3 was the following: starting solvent mixture of 4% B, 0 to 1 min isocratic with 4% B; 1 to 12 min linear gradient to 100% B; 12 to 20 min isocratic with 100% B; 20 to 22 min linear gradient to 4% B; 22 to 25 min isocratic with 4% B. The QTrap 4500 was operated in the negative mode, and the ion source parameters were: ion spray voltage, −4500 V; curtain gas, 30 psi; temperature, 450 °C; collision gas, medium; ion source gas 1, 25 psi; and ion source gas 2, 40 psi.

Supplemental File S2 lists the program and the MRM for each metabolite analyzed (Bajad et al., 2006). The HPLC/MS/MS was controlled by the Analyst® software (Sciex) and analyzed with MultiQuant™ 3.0.2 software (Sciex). Samples were normalized to warfarin and total cellular protein determined via the BCA assay.

Acetyl-phosphate measurement

Pneumococcal strains were grown to mid-logarithmic phase (OD620~0.4) in 20 ml of C−Y with 0.2% glucose or 0.2% galactose. Cells were pelleted and lysed in PBS via mechanical disruption with silica beads in a Fast Prep technique (MP Biomedicals). The total cellular protein was determined by BCA assay. The remaining supernatant was subjected to removal of cellular debris via Amicon 10K filtration (EMD Millipore). Endogenous ATP in the purified lysates was removed by incubation with activated charcoal (Sigma). Acetyl-phosphate was then converted to ATP by using acetate kinase and an ADP cofactor, as described previously (Ramos-Montanez et al., 2010). ATP generated from acetyl-phosphate was measured by using Cell-Titer Glo assays (Promega). Standards of known acetyl-phosphate concentrations were converted to ATP by using the same conditions as those used for the unknown samples. Acetyl-phosphate levels were determined in triplicate, with each sample plated in duplicate. Acetyl-phosphate levels were reported as μmoles of acetyl-phosphate per mg of cellular protein. Acetyl-phosphate levels of the deletion mutants were compared to with those of TIGR4 in each growth condition with unpaired parametric t tests with Prism 6.

Extracellular metabolite measurement

Extracellular metabolites were measured by using kits from Megazyme, including lactate (K-LATE), formate (K-FORM), and ethanol (K-ETOH) kits. The TIGR4 and deletion mutant strains were grown in 10 ml of C−Y with 0.2% glucose or 0.2% galactose. The cell suspension (1 ml) was pelleted via centrifugation and lysed via disruption of the membrane via DOC/SDS. The total cellular protein in the lysates was determined with the BCA assay. The remaining culture was pelleted via centrifugation (6,000 × g, 5 min), and the supernatant was applied undiluted and diluted 1:10 into black 96-well plates with clear bottoms for analysis. Kit instructions were followed per microplate assay procedure. A linear standard was established by using serial dilutions of the provided standards (21–0.021 μg for formate, 24–0.024 μg for lactate, and 10.5–0.010 μg for ethanol). The samples with values that fell within this linear range were included for analysis. All three metabolites were measured concurrently, and the experiment was repeated five times. Lactate, formate, and ethanol levels were reported as μg of metabolite per mg of cellular protein. Metabolites of the deletion mutants were compared with those of TIGR4 in each growth condition with unpaired parametric t tests with Prism 6.

Hydrogen peroxide production

Hydrogen peroxide production was determined using the Amplex Red kit (Thermo Scientific). The strains were grown in 10 ml of C−Y with 0.2% glucose or 0.2% galactose until mid-logarithmic phase (OD620~0.4) was reached. The cell suspension (1 ml) was pelleted via centrifugation and lysed by disruption of membranes via DOC/SDS. The total cellular protein in the lysates was determined by the BCA assay. At the same time, 1 ml of cell suspension was pelleted and resuspended in PBS. After a 30-minute incubation at room temperature, cells were pelleted again, and the supernatant was serially diluted 1:2 in PBS. The hydrogen peroxide produced was determined by following the kit instructions for 96-well plates. Hydrogen peroxide production was measured in duplicate, and the experiment was repeated four times. Hydrogen peroxide levels were reported as μmoles of hydrogen peroxide per mg of cellular protein. Hydrogen peroxide levels of the deletion mutants were compared with those of TIGR4 in each growth condition by using unpaired parametric t tests with Prism 6.

Supplementary Material

References

- Al-Bayati FA, Kahya HF, Damianou A, Shafeeq S, Kuipers OP, Andrew PW, & Yesilkaya H (2017). Pneumococcal galactose catabolism is controlled by multiple regulators acting on pyruvate formate lyase. Sci Rep, 7, 43587. doi: 10.1038/srep43587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajad SU, Lu W, Kimball EH, Yuan J, Peterson C, & Rabinowitz JD (2006). Separation and quantitation of water soluble cellular metabolites by hydrophilic interaction chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A, 1125(1), 76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell A, Brunt J, Crost E, Vaux L, Nepravishta R, Owen CD, … Juge N (2019). Elucidation of a sialic acid metabolism pathway in mucus-foraging Ruminococcus gnavus unravels mechanisms of bacterial adaptation to the gut. Nat Microbiol, 4(12), 2393–2404. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0590-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley SD, Aanensen DM, Mavroidi A, Saunders D, Rabbinowitsch E, Collins M, … Spratt BG (2006). Genetic analysis of the capsular biosynthetic locus from all 90 pneumococcal serotypes. PLoS Genet, 2(3), e31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette KA, Shenoy AT, Milner J 2nd, Gilley RP, McClure E, Hinojosa CA, … Orihuela CJ (2016). Neuraminidase A-Exposed Galactose Promotes Streptococcus pneumoniae Biofilm Formation during Colonization. Infect Immun, 84(10), 2922–2932. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00277-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JS, Sublett JE, Freyer D, Mitchell TJ, Cleveland JL, Tuomanen EI, & Weber JR (2002). Pneumococcal pneumolysin and H(2)O(2) mediate brain cell apoptosis during meningitis. J Clin Invest, 109(1), 19–27. doi: 10.1172/JCI12035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter CM, & King SJ (2012). Pneumococcal carbohydrate transport: food for thought. Trends Microbiol, 20(11), 517–522. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnaugh AM, Frantz LJ, & King SJ (2008). Growth of Streptococcus pneumoniae on human glycoconjugates is dependent upon the sequential activity of bacterial exoglycosidases. J Bacteriol, 190(1), 221–230. doi: 10.1128/JB.01251-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho SM, Farshchi Andisi V, Gradstedt H, Neef J, Kuipers OP, Neves AR, & Bijlsma JJ (2013). Pyruvate oxidase influences the sugar utilization pattern and capsule production in Streptococcus pneumoniae. PLoS One, 8(7), e68277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho SM, Kloosterman TG, Kuipers OP, & Neves AR (2011). CcpA ensures optimal metabolic fitness of Streptococcus pneumoniae. PLoS One, 6(10), e26707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Ma Y, Yang J, O'Brien CJ, Lee SL, Mazurkiewicz JE, … Zhang JR (2007). Genetic requirement for pneumococcal ear infection. PLoS One, 3(8), e2950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Redanz S, Cullin N, Zhou X, Xu X, Joshi V, … Kreth J (2018). Plasticity of the Pyruvate Node Modulates Hydrogen Peroxide Production and Acid Tolerance in Multiple Oral Streptococci. Appl Environ Microbiol, 84(2). doi: 10.1128/AEM.01697-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echlin H, Frank MW, Iverson A, Chang TC, Johnson MD, Rock CO, & Rosch JW (2016). Pyruvate Oxidase as a Critical Link between Metabolism and Capsule Biosynthesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae. PLoS Pathog, 12(10), e1005951. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar P, Al-Bayati FA, Andrew PW, Neves AR, & Yesilkaya H (2014). Lactate dehydrogenase is the key enzyme for pneumococcal pyruvate metabolism and pneumococcal survival in blood. Infect Immun, 82(12), 5099–5109. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02005-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geno KA, Gilbert GL, Song JY, Skovsted IC, Klugman KP, Jones C, … Nahm MH (2015). Pneumococcal Capsules and Their Types: Past, Present, and Future. Clin Microbiol Rev, 28(3), 871–899. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00024-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy GG, Caimano MJ, & Yother J (2000). Capsule biosynthesis and basic metabolism in Streptococcus pneumoniae are linked through the cellular phosphoglucomutase. J Bacteriol, 182(7), 1854–1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway LJ, Brugger SD, Morand B, Bangert M, Rotzetter JU, Hauser C, … Muhlemann K (2012). Capsule type of Streptococcus pneumoniae determines growth phenotype. PLoS Pathog, 8(3), e1002574. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hava DL, & Camilli A (2002). Large-scale identification of serotype 4 Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors. Mol Microbiol, 45(5), 1389–1406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques-Normark B, & Tuomanen EI (2013). The pneumococcus: epidemiology, microbiology, and pathogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 3(7). doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentrich K, Lofling J, Pathak A, Nizet V, Varki A, & Henriques-Normark B (2016). Streptococcus pneumoniae Senses a Human-like Sialic Acid Profile via the Response Regulator CiaR. Cell Host Microbe, 20(3), 307–317. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs JK, Pluvinage B, & Boraston AB (2018). Glycan-metabolizing enzymes in microbe-host interactions: the Streptococcus pneumoniae paradigm. FEBS Lett, 592(23), 3865–3897. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins J, Alborn WE Jr., Arnold J, Blaszczak LC, Burgett S, DeHoff BS, … Glass JI (2001). Genome of the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae strain R6. J Bacteriol, 183(19), 5709–5717. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.19.5709-5717.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer R, Baliga NS, & Camilli A (2005). Catabolite control protein A (CcpA) contributes to virulence and regulation of sugar metabolism in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol, 187(24), 8340–8349. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.24.8340-8349.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahya HF, Andrew PW, & Yesilkaya H (2017). Deacetylation of sialic acid by esterases potentiates pneumococcal neuraminidase activity for mucin utilization, colonization and virulence. PLoS Pathog, 13(3), e1006263. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kietzman CC, Gao G, Mann B, Myers L, & Tuomanen EI (2016). Dynamic capsule restructuring by the main pneumococcal autolysin LytA in response to the epithelium. Nat Commun, 7, 10859. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SJ (2010). Pneumococcal modification of host sugars: a major contributor to colonization of the human airway? Mol Oral Microbiol, 25(1), 15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2009.00564.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivoruchko A, Zhang Y, Siewers V, Chen Y, & Nielsen J (2015). Microbial acetyl-CoA metabolism and metabolic engineering. Metab Eng, 28, 28–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacks S, & Hotchkiss RD (1960). A study of the genetic material determining enzyme in the pneumococcus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 39, 508–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence SH, & Ferry JG (2006). Steady-state kinetic analysis of phosphotransacetylase from Methanosarcina thermophila. J Bacteriol, 188(3), 1155–1158. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.3.1155-1158.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisher JP, Tsui HT, Ramos-Montanez S, Hentchel KL, Martin JE, Trinidad JC, … Giedroc DP (2017). Biological and Chemical Adaptation to Endogenous Hydrogen Peroxide Production in Streptococcus pneumoniae D39. mSphere, 2(1). doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00291-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YT, Pan Y, Lai F, Yin XF, Ge R, He QY, & Sun X (2018). Comprehensive analysis of the lysine acetylome and its potential regulatory roles in the virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Proteomics, 176, 46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2018.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann B, Thornton J, Heath R, Wade KR, Tweten RK, Gao G, … Tuomanen EI (2014). Broadly protective protein-based pneumococcal vaccine composed of pneumolysin toxoid-CbpA peptide recombinant fusion protein. J Infect Dis, 209(7), 1116–1125. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion C, Burnaugh AM, Woodiga SA, & King SJ (2011). Sialic acid transport contributes to pneumococcal colonization. Infect Immun, 79(3), 1262–1269. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00832-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx P, Meiers M, & Bruckner R (2014). Activity of the response regulator CiaR in mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae R6 altered in acetyl phosphate production. Front Microbiol, 5, 772. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AL, Roche AM, Gould JM, Chim K, Ratner AJ, & Weiser JN (2007). Capsule enhances pneumococcal colonization by limiting mucus-mediated clearance. Infect Immun, 75(1), 83–90. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01475-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves AR, Pool WA, Kok J, Kuipers OP, & Santos H (2005). Overview on sugar metabolism and its control in Lactococcus lactis - the input from in vivo NMR. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 29(3), 531–554. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2005.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves AR, Pool WA, Solopova A, Kok J, Santos H, & Kuipers OP (2010). Towards enhanced galactose utilization by Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol, 76(21), 7048–7060. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01195-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves AR, Ventura R, Mansour N, Shearman C, Gasson MJ, Maycock C, … Santos H (2002). Is the glycolytic flux in Lactococcus lactis primarily controlled by the redox charge? Kinetics of NAD(+) and NADH pools determined in vivo by 13C NMR. J Biol Chem, 277(31), 28088–28098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202573200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick S, Shagan M, Blau K, Lifshitz S, Givon-Lavi N, Grossman N, … Mizrachi Nebenzahl Y (2017). Adhesion and invasion of Streptococcus pneumoniae to primary and secondary respiratory epithelial cells. Mol Med Rep, 15(1), 65–74. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orihuela CJ, Gao G, Francis KP, Yu J, & Tuomanen EI (2004). Tissue-specific contributions of pneumococcal virulence factors to pathogenesis. J Infect Dis, 190(9), 1661–1669. doi: 10.1086/424596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orihuela CJ, Mahdavi J, Thornton J, Mann B, Wooldridge KG, Abouseada N, … Tuomanen EI (2009). Laminin receptor initiates bacterial contact with the blood brain barrier in experimental meningitis models. J Clin Invest, 119(6), 1638–1646. doi: 10.1172/JCI36759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paixao L, Caldas J, Kloosterman TG, Kuipers OP, Vinga S, & Neves AR (2015). Transcriptional and metabolic effects of glucose on Streptococcus pneumoniae sugar metabolism. Front Microbiol, 6, 1041. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paixao L, Oliveira J, Verissimo A, Vinga S, Lourenco EC, Ventura MR, … Neves AR (2015). Host glycan sugar-specific pathways in Streptococcus pneumoniae: galactose as a key sugar in colonisation and infection [corrected]. PLoS One, 10(3), e0121042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelroy RA, & Whiteley HR (1972). Kinetic properties of phosphotransacetylase from Veillonella alcalescens. J Bacteriol, 111(1), 47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pericone CD, Park S, Imlay JA, & Weiser JN (2003). Factors contributing to hydrogen peroxide resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae include pyruvate oxidase (SpxB) and avoidance of the toxic effects of the fenton reaction. J Bacteriol, 185(23), 6815–6825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Montanez S, Kazmierczak KM, Hentchel KL, & Winkler ME (2010). Instability of ackA (acetate kinase) mutations and their effects on acetyl phosphate and ATP amounts in Streptococcus pneumoniae D39. J Bacteriol, 192(24), 6390–6400. doi: 10.1128/JB.00995-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Montanez S, Tsui HC, Wayne KJ, Morris JL, Peters LE, Zhang F, … Winkler ME (2008). Polymorphism and regulation of the spxB (pyruvate oxidase) virulence factor gene by a CBS-HotDog domain protein (SpxR) in serotype 2 Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol, 67(4), 729–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06082.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regev-Yochay G, Trzcinski K, Thompson CM, Lipsitch M, & Malley R (2007). SpxB is a suicide gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae and confers a selective advantage in an in vivo competitive colonization model. J Bacteriol, 189(18), 6532–6539. doi: 10.1128/JB.00813-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosch JW, Mann B, Thornton J, Sublett J, & Tuomanen E (2008). Convergence of regulatory networks on the pilus locus of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun, 76(7), 3187–3196. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00054-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelburne SA, Davenport MT, Keith DB, & Musser JM (2008). The role of complex carbohydrate catabolism in the pathogenesis of invasive streptococci. Trends Microbiol, 16(7), 318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy AT, Brissac T, Gilley RP, Kumar N, Wang Y, Gonzalez-Juarbe N, … Orihuela CJ (2017). Streptococcus pneumoniae in the heart subvert the host response through biofilm-mediated resident macrophage killing. PLoS Pathog, 13(8), e1006582. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi IY, Stansbury J, & Kuzminov A (2005). A defect in the acetyl coenzyme A<-->acetate pathway poisons recombinational repair-deficient mutants of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol, 187(4), 1266–1275. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.4.1266-1275.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AW, Roche H, Trombe MC, Briles DE, & Hakansson A (2002). Characterization of the dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase from Streptococcus pneumoniae and its role in pneumococcal infection. Mol Microbiol, 44(2), 431–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellerberg B, Cundell DR, Sandros J, Pearce BJ, Idanpaan-Heikkila I, Rosenow C, & Masure HR (1996). Pyruvate oxidase, as a determinant of virulence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol, 19(4), 803–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniai H, Iida K, Seki M, Saito M, Shiota S, Nakayama H, & Yoshida S (2008). Concerted action of lactate oxidase and pyruvate oxidase in aerobic growth of Streptococcus pneumoniae: role of lactate as an energy source. J Bacteriol, 190(10), 3572–3579. doi: 10.1128/JB.01882-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terra VS, Homer KA, Rao SG, Andrew PW, & Yesilkaya H (2010). Characterization of novel beta-galactosidase activity that contributes to glycoprotein degradation and virulence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun, 78(1), 348–357. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00721-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thamadilok S, Roche-Hakansson H, Hakansson AP, & Ruhl S (2016). Absence of capsule reveals glycan-mediated binding and recognition of salivary mucin MUC7 by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Oral Microbiol, 31(2), 175–188. doi: 10.1111/omi.12113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas TD, Turner KW, & Crow VL (1980). Galactose fermentation by Streptococcus lactis and Streptococcus cremoris: pathways, products, and regulation. J Bacteriol, 144(2), 672–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya Y, Zhyvoloup A, Bakovic J, Thomas N, Yu BYK, Das S, … Gout I (2018). Protein CoAlation and antioxidant function of coenzyme A in prokaryotic cells. Biochem J, 475(11), 1909–1937. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20180043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Zhang Y, Yang C, Xiong H, Lin Y, Yao J, … Zhao GP (2010). Acetylation of metabolic enzymes coordinates carbon source utilization and metabolic flux. Science, 327(5968), 1004–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1179687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser JN, Ferreira DM, & Paton JC (2018). Streptococcus pneumoniae: transmission, colonization and invasion. Nat Rev Microbiol, 16(6), 355–367. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0001-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesilkaya H, Manco S, Kadioglu A, Terra VS, & Andrew PW (2008). The ability to utilize mucin affects the regulation of virulence gene expression in Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 278(2), 231–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.01003.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesilkaya H, Spissu F, Carvalho SM, Terra VS, Homer KA, Benisty R, … Andrew PW (2009). Pyruvate formate lyase is required for pneumococcal fermentative metabolism and virulence. Infect Immun, 77(12), 5418–5427. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00178-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.