Abstract

Background: We present immunogenicity data 6 months after the first dose of BNT162b2 in correlation with age, gender, BMI, comorbidities and previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. Methods: An immunogenicity evaluation was carried out among health care workers (HCW) vaccinated at the Istituti Fisioterapici Ospitalieri (IFO). All HCW were asked to be vaccine by the national vaccine campaign at the beginning of 2021. Serum samples were collected on day 1 just prior to the first dose of the vaccine and on day 21 just prior to the second vaccination dose. Thereafter sera samples were collected 28, 49, 84 and 168 days after the first dose of BNT162b2. Quantitative measurement of IgG antibodies against S1/S2 antigens of SARS-CoV-2 was performed with a commercial chemiluminescent immunoassay. Results: Two hundred seventy-four HWCs were analyzed, 175 women (63.9%) and 99 men (36.1%). The maximum antibody geometric mean concentration (AbGMC) was reached at T2 (299.89 AU/mL; 95% CI: 263.53–339.52) with a significant increase compared to baseline (p < 0.0001). Thereafter, a progressive decrease was observed. At T5, a median decrease of 59.6% in COVID-19 negative, and of 67.8% in COVID-19 positive individuals were identified with respect to the highest antibody response. At T1, age and previous COVID-19 were associated with differences in antibody response, while at T2 and T3 differences in immune response were associated with age, gender and previous COVID-19. At T4 and T5, only COVID-19 positive participants demonstrated a greater antibody response, whereas no other variables seemed to influence antibody levels. Conclusions: Overall our study clearly shows antibody persistence at 6 months, albeit with a certain decline. Thus, the use of this vaccine in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic is supported by our results that in turn open debate about the need for further boosts.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, mRNA vaccine, BNT162b2, antibody response

1. Introduction

Among vaccines against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines represent great promise for the decrease in the spread of infection. However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency approved the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination program in an emergency, and presently there is a lack of data on the length of the immune response. An optimal COVID-19 vaccine should provide a long-lasting antibody response and would stimulate sterilizing immunity to avoid disease and forward transmission [1]. Notwithstanding rigorous research, it is not usually predictable the kinetics, and evolution of immune memory to infection or vaccine based on the initial effector phase [2].

Therefore, a longer follow-up is needed to assess the antibody kinetics in individuals after a two-dose regimen of BNT162b2. These data are important to program future vaccination campaigns. We present the experience with BNT162b2 vaccination in 274 participants, an ongoing longitudinal observational study of health-care workers (HCWs) in Istituti Fisioterapici Ospitalieri of Rome [3,4]. Here, we update immunogenicity data 6 months after the first vaccine dose in correlation with age, gender, BMI, comorbidities and previous SARS-CoV-2 infection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

A collaborative team carried out an immunogenicity evaluation among HCWs having received two doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine at the Istituti Fisioterapici Ospitalieri (IFO). Briefly, the study protocol complied with the tenets of the Helsinki declaration and was approved by the institutional scientific ethics committee (protocol RS1463/21) and registered to a Clinical Trial registry ISRCTN55371988. Participants were requested to provide written informed consent. All the enrolled participants met the following inclusion criteria: (1) provided written informed consent; (2) age between 18–75 years; (3) health workers employed at the Istituti Fisioterapici Ospitalieri (IFO); (4) vaccinated at the Istituti Fisioterapici Ospitalieri (IFO). Key exclusion criteria included: (1) treatment with immunosuppressive therapy; (2) immunosuppression-associated pathology; and (3) pregnancy.

The mRNA vaccine was administered as a 30 microgram/0.3 mL intramuscular injection into the deltoid muscle on days 1 and 21 of the study. A questionnaire to collect socio-demographic and health data was administered to participants at baseline. Serum samples were collected on day 1 just prior to the first dose of vaccine and on day 21 just prior to the second dose vaccination. Thereafter sera samples were collected 28, 49, 84 and 168 days after the first dose of BNT162b2. Collected sera were stored at +4 °C until use and analyzed within 6 h after collection. Aliquots of sera were stored frozen at −20 °C for further analyses. Quantitative measurement of IgG antibodies against S1/S2 antigens of SARS-CoV-2 was performed with a commercial chemiluminescent immunoassay (The LIAISON® SARS-CoV-2 S1/S2 IgG test, Diasorin, Italy) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The concentration of <3.8 AU/mL was adopted as a cut-off to define negative humoral responses, as reported in the manufacturer instruction.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

The Geometric Mean of AU/mL and its 95% confidence interval was described for the total series and for each subgroup. A generalized linear model using the logarithm of titer as a dependent variable was implemented to assess the correlation between gender, age and BMI, comorbidities and seropositive patients with serum concentration. Age was then categorized through quartiles and BMI subgroups were created according to WHO classes as follows: underweight (BMI > 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI ≥ 18.5 = 24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI ≥ 25 = 29.9 kg/m2) and obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) [5]. However, age and BMI were considered as continuous variables in statistical analysis. The half-life was obtained from the one-compartment modeling which permitted the calculation of the elimination rate of the antibody response.

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS Statistics software version 21. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Two hundred seventy-four HWCs were analyzed, 175 women (63.9%) and 99 men (36.1%) and all participants were of Caucasian ethnicity. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the HCW population are represented in Table 1. Of these, 15 (5.4%) were categorized as SARS-CoV-2 positive because they reported positive nasopharyngeal swabs for SARS-CoV-2 in previous months. Infections took place between March and November 2020. Too few patients (only 4) reported diabetes and therefore this variable was not further analyzed. Age and BMI were considered as continuous variables in statistical analysis.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the HCW.

| Characteristic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 |

| Total Patients | 274 | 271 | 270 | 251 | 250 | 232 |

| Age | ||||||

| Median (rage) | 46.1 (23–69) | 46.1 (23–69) | 46.1 (23–69) | 45.8 (23–69) | 45.8 (23–69) | 45.4 (23–69) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 174 | 173 | 170 | 169 | 164 | 156 |

| Male | 100 | 98 | 100 | 82 | 86 | 76 |

| Bmi | ||||||

| Under-Weight | 20 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 18 |

| Normal-Weight | 162 | 161 | 160 | 150 | 154 | 141 |

| Pre-Obesity | 66 | 64 | 64 | 58 | 54 | 52 |

| Obesity | 26 | 26 | 26 | 24 | 23 | 21 |

| Hypertension | ||||||

| NO | 243 | 240 | 239 | 222 | 223 | 202 |

| YES | 31 | 31 | 31 | 29 | 27 | 30 |

| Hypothyroidism | ||||||

| NO | 256 | 253 | 252 | 233 | 232 | 214 |

| YES | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| NO | 270 | 267 | 266 | 249 | 248 | 230 |

| YES | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Previous COVID-19 | ||||||

| NO | 259 | 256 | 255 | 239 | 236 | 218 |

| YES | 15 | 15 | 15 | 12 | 14 | 14 |

All participants still had measurable anti-SARS-CoV-2 S antibodies until day 168.

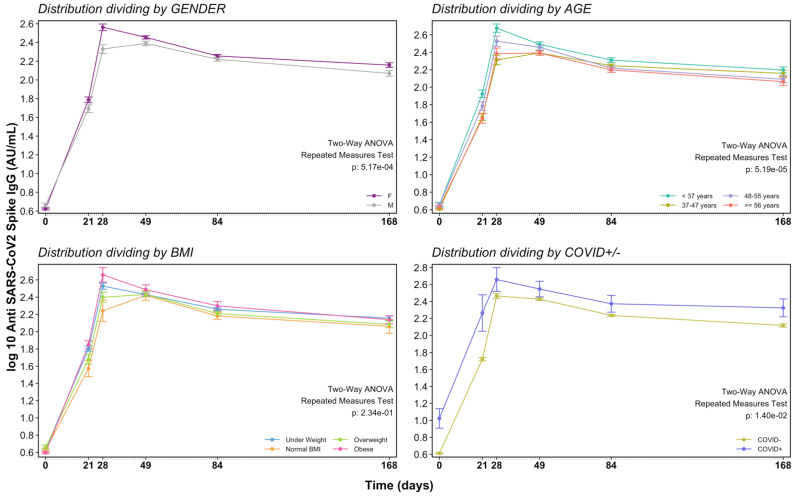

At T1, when just one vaccine dose was injected, we already detected a humoral response with AbGMC of 56.69 AU/mL, above the cut-off value. The maximum AbGMC was reached at T2 (299.89 AU/mL; 95% CI: 263.53–339.52) with a significant increase compared to baseline (p < 0.0001). Thereafter, a progressive decrease was observed at T3 (271.09 AU/mL; 95% CI: 254.71–289.26), T4 (175.37 AU/mL; 95% CI: 165.51–186.06), and T5 (134.64 AU/mL; 95% CI: 123.25–146.54) (Table 2). At T5, a median decrease of 59.6% in COVID-19 negative, and of 67.8% in COVID-19 positive individuals were identified with respect to the highest antibody response (Figure 1). The estimated half-life of antibodies from data collected until 168 days post-vaccination was 275 days as calculated by the one-compartmental model.

Table 2.

GMC and 95% CI for all subjects, COVID-19 negative and COVID-19 positive at T0, T1, T2, T3 T4 and T5 (6 months after first dose).

| Characteristic | N. HCW T0 (Day 0) | GMC (95% CI) | N. HCW T1 (Day 21) | GMC (95% CI) | N. HCW T2 (Day 28) | GMC (95% CI) | N. HCW T3 (Day 49) | GMC (95% CI) | N. HCW T4 (Day 84) | GMC (95% CI) | N. HCW T5 (Day 168) | GMC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | ||||||

| All subjects | 274 | 4.32 (4.14–4.54) | 271 | 56.69 (50.90–63.15 | 270 | 299.89 (263.53–339.52) | 251 | 271.09 (254.71–289.26) | 250 | 175.37 (165.51–186.06) | 232 | 134.64 (123.25–146.54) |

| COVID-19 no | 259 | 4.11 (4.02–4.22) | 257 | 52.51 (47.90–57.67) | 256 | 290.77 (254.38–329.52) | 240 | 266.25 (250.33–283.53) | 237 | 171.47 (162.38–181.34) | 219 | 130.81 (120.45–143.14) |

| COVID-19 yes | 15 | 10.29 (5.93–17.87) | 15 | 209.13 (83.15–566.19) | 15 | 506.88 (271.74–957.86) | 12 | 388.13 (263.10–600.62) | 14 | 256.17 (166.94–422.14) | 14 | 211.14 (134.33–335.90) |

GMC: geometric mean concentration; CI: confidence interval.

Figure 1.

Time course of antibody response after vaccination by gender, age, BMI and previous COVID-19.

Univariate analysis (Table 3) considering age and BMI as continuous variables showed that at T1, antibody titer was greater in younger, lean, with no hypertension and with having had COVID-19 previously. At T2, a statistically significant difference in antibody levels was observed in the young, lean, female and no hypertension group. At T3, a difference in humoral response was observed only in the younger, in females and in those who had had COVID-19 previously. At T4, antibody titer was greater in the younger people and with those who had previously had COVID-19. Finally, at T5, only people who had previously had COVID-19 were associated with greater humoral response.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate linear regression of antibody levels (AU/mL) by age, BMI, gender, hypertension, hypothyroidism, and previous COVID-19.

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (95% CI) | p Value | Beta (95% CI) | p Value | ||

| T0 | Age (in years) | −0.004 (−0.008; 0.001) | 0.054 | −0.003 (−0.007; 0.001) | 0.092 |

| Bmi (kg/cm2) | 0.005 (−0.005; 0.016) | 0.299 | 0.003 (−0.006; 0.013) | 0.495 | |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 0.093 (0.000; 0.186) | 0.050 | 0.069 (−0.014; 0.149) | 0.104 | |

| Hypertension (yes vs. no) | −0.042 (−0.180; 0.096) | 0.552 | 0.037 (−0.086; 0.160) | 0.555 | |

| Hypothyroidism (yes vs. no) | −0.018 (−0.199; 0.164) | 0.850 | 0.068 (−0.083; 0.219) | 0.379 | |

| Previous COVID-19 (yes vs. no) | 0.917 (0.752; 1.083) | 0.0001 | 0.968 (0.799; 1.137) | 0.0001 | |

| T1 | Age (in years) | −0.023 (−0.032; −0.014) | 0.0001 | −0.016 (−0.026; −0.007) | 0.001 |

| Bmi (kg/cm2) | −0.037 (−0.062; −0.013) | 0.003 | −0.023 (−0.046; 0.001) | 0.062 | |

| Gender (male vs. female) | −0.220 (−0.444; 0.005) | 0.055 | −0.120 (−0.329; 0.090) | 0.263 | |

| Hypertension (no vs. yes) | −0.454 (−0.781; −0.127) | 0.006 | −0.065 (−0.379; 0.249) | 0.685 | |

| Hypothyroidism (yes vs. no) | 0.116 (−0.319; 0.551) | 0.603 | 0.157 (−0.229; 0.542) | 0.426 | |

| Previous COVID-19 (yes vs. no) | 1.382 (0.937; 1.826) | 0.0001 | 1.551 (1.120; 1.983) | 0.0001 | |

| T2 | Age (in years) | −0.030 (−0.040; −0.019) | 0.0001 | −0.023 (−0.035; −0.011) | 0.0001 |

| Bmi (kg/cm2) | −0.051 (−0.080; −0.022) | 0.001 | −0.017 (−0.048; 0.013) | 0.257 | |

| Gender (male vs. female) | −0.534 (−0.795; −0.272) | 0.0001 | −0.422 (−0.686; −0.157) | 0.002 | |

| Hypertension (yes vs. no) | −0.605 (−1.005; −0.205) | 0.003 | −0.123 (−0.533; 0.286) | 0.554 | |

| Hypothyroidism (yes vs. no) | 0.163 (−0.356; 0.683) | 0.538 | 0.063 (−0.425; 0.552) | 0.799 | |

| Previous COVID-19 (yes vs. no) | 0.556 (−0.007; 1.118) | 0.053 | 0.565 (0.018; 1.112) | 0.043 | |

| T3 | Age (in years) | −0.009 (−0.014; −0.003) | 0.002 | −0.009 (−0.015; −0.003) | 0.003 |

| Bmi (kg/cm2) | −0.004 (−0.019; 0.011) | 0.610 | 0.006 (−0.010; 0.021) | 0.480 | |

| Gender (male vs. female) | −0.148 (−0.282; −0.014) | 0.030 | −0.140 (−0.278; −0.003) | 0.046 | |

| Hypertension (yes vs. no) | −0.065 (−0.263; 0.133) | 0.521 | 0.087 (−0.118; 0.293) | 0.404 | |

| Hypothyroidism (yes vs. no) | 0.208 (−0.036; 0.452) | 0.095 | 0.216 (−0.022; 0.454) | 0.075 | |

| Previous COVID-19 (yes vs. no) | 0.377 (0.084; 0.670) | 0.012 | 0.470 (0.171; 0.768) | 0.002 | |

| T4 | Age (in years) | −0.006 (−0.010; −0.001) | 0.015 | −0.005 (−0.010; 0.001) | 0.101 |

| Bmi (kg/cm2) | −0.013 (−0.026; 0.001) | 0.064 | −0.009 (−0.024; 0.005) | 0.206 | |

| Gender (male vs. female) | −0.082 (−0.204; 0.039) | 0.186 | −0.050 (−0.176; 0.076) | 0.435 | |

| Hypertension (yes vs. no) | −0.083 (−0.270; 0.103) | 0.381 | 0.042 (−0.153; 0.237) | 0.674 | |

| Hypothyroidism (yes vs. no) | 0.036 (−0.188; 0.260) | 0.754 | 0.048 (−0.172; 0.267) | 0.670 | |

| Previous COVID-19 (yes vs. no) | 0.401 (0.154; 0.649) | 0.001 | 0.474 (0.221; 0.728) | 0.0001 | |

| T5 | Age (in years) | −0.007 (−0.014; 0.001) | 0.084 | −0.004 (−0.013; 0.004) | 0.309 |

| Bmi (kg/cm2) | −0.016 (−0.036; 0.004) | 0.116 | −0.010 (−0.032; 0.011) | 0.355 | |

| Gender (male vs. female) | −0.204 (−0.388; −0.020) | 0.031 | −0.185 (−0.378; 0.008) | 0.061 | |

| Hypertension (yes vs. no) | −0.118 (−0.374; 0.138) | 0.367 | 0.061 (−0.218; 0.340) | 0.668 | |

| Hypothyroidism (yes vs. no) | 0.189 (−0.136; 0.515) | 0.255 | 0.177 (−0.145; 0.499) | 0.281 | |

| Previous COVID-19 (yes vs. no) | 0.479 (0.117; 0.840) | 0.009 | 0.605 (0.230; 0.980) | 0.002 |

Multivariate analysis accounting for potential confounding elements was performed by the inclusion of covariates. Data on multivariate linear regression of AU/mL are reported in Table 3. This analysis demonstrated that at T1 age (p = 0.001) and previous COVID-19 (p < 0.0001) are statistically associated with differences in antibody response. At T2 and T3, the difference in immune response is associated with age (p = 0.0001, p = 0.003, respectively), gender (p = 0.002, p = 0.046, respectively) and previous COVID-19 (p = 0.043, p = 0.002, respectively). At T4 and T5 only previous COVID-19 is associated with a difference in antibody response (p = 0.0001, p = 0.002, respectively).

4. Discussion

Since the first cases of COVID-19 were described in December 2019 a health emergency with major social and economic disruptions has spread worldwide [6]. Thus, the research of the world scientific community was focused on the development of an effective vaccine.

Notwithstanding rigorous study in humans, kinetic, duration, and evolution of antibody response to immunization are not predictable based on the early effector phase. Therefore, measuring responses over a period of months is essential to determine the durability of the immune response [2,7]. Several recent reports indicate that after two doses of BNT162b2 antibodies persisted up to 3 months, however, a significant decrease in their serum levels could be observed during this period [8,9]. Currently, a longer follow-up after an mRNA vaccine is reported by Doria-Rose et al., showed persistence of antibodies 6 months after the second dose of the mRNA-1273 vaccine in 33 participants included in the phase 1 follow-up of the Moderna study without knowing their initial serological status before vaccination [10]. Our data represent an independent study on antibody levels against S1/S2 SARS-CoV-2 in HCWs 6 months after the first dose of BNT162b2. Notably at T5, 100% of participants demonstrated antigen-specific humoral response with respect to baseline level. At 6 months, a median antibody decreases of 59.6% and 67.8% in COVID-19 negative and COVID-19 positive individuals were identified from the highest antibody response. Favresse et al. reported similar results for COVID-19 negative vs. COVID-19 positive subjects, strengthening our data [9]. Interestingly we reported the correlation of antibody response with multiple variables, however, at present, we do not have a clear hypothesis to explain why different variables were affecting serum level according to time after vaccination. The analysis was performed with age and BMI calculated as continuous variables. Indeed, by aggregating these variables into groups, there is the possibility that valuable information is missing, and analysis findings could be misleading. Furthermore, multivariate linear regression of AU/mL, accounting for potential confounding data by the inclusion of covariates is more insightful and accurate than a univariate analysis. Our data demonstrated statically significant differences by age in antibody response at T1, T2 and T3. It is well recognized in the literature that aging and related immunosenescence may lead to a reduced humoral response to the vaccine [11]. In particular, qualitative differences were observed in the memory B cells and plasma compartment in older adults. This included class switch recombination and differentiation into plasma cells [12,13]. With immunosenescence, another modification is the increase in an inflammatory subset of B cells similar to age-associated B cells (ABCs) as described in mice [14,15]. It was shown that an increased level of CD27 + ABCs in the blood of the elderly was associated with a reduced titer of influenza-specific antibodies [16].

In addition, our observations also showed this difference in vaccine response at T2 and T3, in line with a recent meta-analysis [17] Literature reports advise that COVID-19 exhibits differences in morbidity and mortality between gender. Male patients have almost three times the odds of requiring intensive treatment unit admission and higher odds of death compared to females [18]. Women produce higher antibody titers in response to the trivalent inactivated seasonal influenza vaccination (TIV) [19,20]. More specifically, females achieve equivalent protective antibody titers to males at half the dose of TIV [20], with serum testosterone levels inversely correlating with TIV antibody titers [21]. Finally, several studies have already shown a correlation between the antibody response to the vaccine and the previous infection with SARS-CoV-2.

In the present article, we report that humoral response to the vaccine is statistically correlated with the previous infection in all observed times.

Although the role of Nabs to SARS-CoV-2 is under investigation, measurement of serum neutralizing activity was demonstrated to correlate with protection for other respiratory viruses, such as influenza [22] or respiratory syncytial virus [23]. In this study, we utilized a chemiluminescent immunoassay that detects S1/S2 specific antibodies, but it was not specifically designed to detect Nabs. However, the manufacturer indicates that with 80-AU/mL levels, the probabilities of having plaque reduction neutralization titers of 1:80 and 1:160 were 92% and 87%, respectively [24]. At T5, albeit declining, antibody levels were above >80 AU/mL in a consistent number of enrolled patients (80.7%, 80.5% and 85.8% of the total, COVID-19 negative, and COVID-19 positive participants, respectively), suggesting that a possible neutralizing activity is present 168 days after first vaccine dose.

The principal limitations of the study are the following: (i) our study is a single-center study with a limited number of participants; (ii) all subjects were of Caucasian ethnicity; therefore, it cannot be assumed representative of the general population nor of the non-Caucasian population; (iii). We utilized a questionnaire to collect data on the participants’ socio-demographic and health characteristics, and the possibility of self-reporting bias should be considered; (iv) previous COVID-19 negative HCW did not take into account the possibility of asymptomatic cases; (v) finally, data about cellular immune response and neutralization antibodies are also lacking.

However, a subset of sera from our cohort (175 samples) was utilized as control group in a study on cancer patients and analysed for Nabs. Titre of Nabs and anti-S IgG more than 80 AU/mL were significantly associated (Spearman’s rho = 0.799, p < 0.0001). This suggesting that Nabs could be present in sera with a total antibody titer above 80 AU/m [25]. In addition, during follow-up, none of the vaccinee HCW referred any symptoms related to possible COVID-19 disease or positivity to nasopharyngeal swab test.

5. Conclusions

Overall, our study clearly shows antibody persistence at 6 months, albeit with a certain decline. Thus, the use of this vaccine in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic is supported by our results that in turn open debate about the need for further boosts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: R.P., A.V. (Aldo Venuti), F.C. (Flaminia Campo), A.M. and G.C.; methodology: F.P. (Fulvia Pimpinelli), M.P., E.A., E.G.D.D., C.M., F.D.M., F.E., G.B., B.V., G.P. (Giulia Piaggio), L.C. and S.D.M.; formal analysis: D.G., and E.S., investigation: S.M., B.P., F.M., G.P. (Gerardo Petruzzi), A.V. (Antonello Vidiri), A.D.V., V.R. and F.P. (Fabrizio Petrone); writing original draft: A.V. (Aldo Venuti), F.C. (Flaminia Campo), and R.P., writing—review and editing: A.V. (Aldo Venuti), R.P., V.D.N., F.C. (Francesco Cognetti) and F.C. (Flaminia Campo). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol complied with the tenets of the Helsinki declaration and was approved by the institutional scientific ethics committee (protocol RS1463/21) and registered to a Clinical Trial registry ISRCTN55371988.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are going to be added to the clinical trial registry (ISRCTN55371988) where they will be available.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sette A., Crotty S. Adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Cell. 2021;184:861–880. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dan J.M., Mateus J., Kato Y., Hastie K.M., Yu E.D., Faliti C.E., Grifoni A., Ramirez S.I., Haupt S., Frazier A., et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science. 2021;371 doi: 10.1126/science.abf4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pellini R., Venuti A., Pimpinelli F., Abril E., Blandino G., Campo F., Conti L., De Virgilio A., De Marco F., Di Domenico E.G., et al. Early Onset of SARS-Cov-2 Antibodies after First Dose of BNT162b2: Correlation with Age, Gender and BMI. Vaccines. 2021;9:685. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pellini R., Venuti A., Pimpinelli F., Abril E., Blandino G., Campo F., Conti L., De Virgilio A., De Marco F., Di Domenico E.G., et al. Initial observations on age, gender, BMI and hypertension in antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;36:100928. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weir C.B., Jan A. StatPearls [Internet] StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island, FL, USA: 2020. [(accessed on 4 May 2021)]. BMI Classification Percentile and Cut Off Points. [Updated 2020 Jul 10] Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ralli M., Candelori F., Cambria F., Greco A., Angeletti D., Lambiase A., Campo F., Minni A., Polimeni A., de Vincentiis M. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on otolaryngology, ophthalmology and dental clinical activity and future perspectives. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020;24:9705–9711. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202009_23062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amodio E., Capra G., Casuccio A., Grazia S., Genovese D., Pizzo S., Calamusa G., Ferraro D., Giammanco G.M., Vitale F., et al. Antibodies Responses to SARS-CoV-2 in a Large Cohort of Vaccinated Subjects and Seropositive Patients. Vaccines. 2021;9:714. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salvagno G.L., Henry B.M., Pighi L., De Nitto S., Gianfilippi G.L., Lippi G. Three-month analysis of total humoral response to Pfizer BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in healthcare workers. J. Infect. 2021;83:e4–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Favresse J., Bayart J.L., Mullier F., Elsen M., Eucher C., Van Eeckhoudt S., Roy T., Wieers G., Laurent C., Dogne J.M., et al. Antibody titres decline 3-month post-vaccination with BNT162b2. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021;10:1495–1498. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2021.1953403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doria-Rose N., Suthar M.S., Makowski M., O’Connell S., McDermott A.B., Flach B., Ledgerwood J.E., Mascola J.R., Graham B.S., Lin B.C., et al. Antibody Persistence through 6 Months after the Second Dose of mRNA-1273 Vaccine for COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:2259–2261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2103916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poland G.A., Ovsyannikova I.G., Kennedy R.B. Personalized vaccinology: A review. Vaccine. 2018;36:5350–5357. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frasca D., Diaz A., Romero M., Blomberg B.B. The generation of memory B cells is maintained, but the antibody response is not, in the elderly after repeated influenza immunizations. Vaccine. 2016;34:2834–2840. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frasca D., Diaz A., Romero M., Landin A.M., Phillips M., Lechner S.C., Ryan J.G., Blomberg B.B. Intrinsic defects in B cell response to seasonal influenza vaccination in elderly humans. Vaccine. 2010;28:8077–8084. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hao Y., O’Neill P., Naradikian M.S., Scholz J.L., Cancro M.P. A B-cell subset uniquely responsive to innate stimuli accumulates in aged mice. Blood. 2011;118:1294–1304. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-330530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubtsov A.V., Rubtsova K., Fischer A., Meehan R.T., Gillis J.Z., Kappler J.W., Marrack P. Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7)-driven accumulation of a novel CD11c(+) B-cell population is important for the development of autoimmunity. Blood. 2011;118:1305–1315. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-331462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nipper A.J., Smithey M.J., Shah R.C., Canaday D.H., Landay A.L. Diminished antibody response to influenza vaccination is characterized by expansion of an age-associated B-cell population with low PAX5. Clin. Immunol. 2018;193:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bignucolo A., Scarabel L., Mezzalira S., Polesel J., Cecchin E., Toffoli G. Sex Disparities in Efficacy in COVID-19 Vaccines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines. 2021;9:825. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peckham H., de Gruijter N.M., Raine C., Radziszewska A., Ciurtin C., Wedderburn L.R., Rosser E.C., Webb K., Deakin C.T. Male sex identified by global COVID-19 meta-analysis as a risk factor for death and ITU admission. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:6317. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19741-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voigt E.A., Ovsyannikova I.G., Kennedy R.B., Grill D.E., Goergen K.M., Schaid D.J., Poland G.A. Sex Differences in Older Adults’ Immune Responses to Seasonal Influenza Vaccination. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:180. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engler R.J., Nelson M.R., Klote M.M., Van Raden M.J., Huang C.Y., Cox N.J., Klimov A., Keitel W.A., Nichol K.L., Carr W.W., et al. Walter Reed Health Care System Influenza Vaccine, C. Half- vs full-dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (2004–2005): Age, dose, and sex effects on immune responses. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008;168:2405–2414. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furman D., Hejblum B.P., Simon N., Jojic V., Dekker C.L., Thiebaut R., Tibshirani R.J., Davis M.M. Systems analysis of sex differences reveals an immunosuppressive role for testosterone in the response to influenza vaccination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:869–874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321060111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verschoor C.P., Singh P., Russell M.L., Bowdish D.M., Brewer A., Cyr L., Ward B.J., Loeb M. Microneutralization assay titres correlate with protection against seasonal influenza H1N1 and H3N2 in children. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0131531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kulkarni P.S., Hurwitz J.L., Simoes E.A.F., Piedra P.A. Establishing Correlates of Protection for Vaccine Development: Considerations for the Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccine Field. Viral Immunol. 2018;31:195–203. doi: 10.1089/vim.2017.0147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonelli F., Sarasini A., Zierold C., Calleri M., Bonetti A., Vismara C., Blocki F.A., Pallavicini L., Chinali A., Campisi D., et al. Clinical and Analytical Performance of an Automated Serological Test That Identifies S1/S2-Neutralizing IgG in COVID-19 Patients Semiquantitatively. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58:e01224-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01224-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Noia V., Pimpinelli F., Renna D., Barberi V., Maccallini M.T., Gariazzo L. Immunogenicity and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccine BNT162b2 for Patients with Solid Cancer: A Large Cohort Prospective study from a Single Institution. [(accessed on 28 September 2021)]. Available online: https://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/early/2021/09/23/1078-0432.CCR-21-2439. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are going to be added to the clinical trial registry (ISRCTN55371988) where they will be available.