Abstract

The fungus-like microorganism Pythium insidiosum causes pythiosis, a life-threatening infectious disease increasingly reported worldwide. Antimicrobial drugs are ineffective. Radical surgery is an essential treatment. Pythiosis can resume post-surgically. Immunotherapy using P. insidiosum antigens (PIA) has emerged as an alternative treatment. This review aims at providing up-to-date information of the immunotherapeutic PIA, with the focus on its history, preparation, clinical application, outcome, mechanism, and recent advances, in order to promote the proper use and future development of this treatment modality. P. insidiosum crude extract is the primary source of immunotherapeutic antigens. Based on 967 documented human and animal (mainly horses) pythiosis cases, PIA immunotherapy reduced disease morbidity and mortality. Concerning clinical outcomes, 19.4% of PIA-immunized human patients succumbed to vascular pythiosis instead of 41.0% in unimmunized cases. PIA immunotherapy may not provide an advantage in a local P. insidiosum infection of the eye. Both PIA-immunized and unimmunized horses with pythiosis showed a similar survival rate of ~70%; however, demands for surgical intervention were much lesser in the immunized cases (22.8% vs. 75.2%). The proposed PIA action involves switching the non-protective T-helper-2 to protective T-helper-1 mediated immunity. By exploring the available P. insidiosum genome data, synthetic peptides, recombinant proteins, and nucleic acids are potential sources of the immunotherapeutic antigens worth investigating. The PIA therapeutic property needs improvement for a better prognosis of pythiosis patients.

Keywords: pythiosis, Pythium insidiosum, antigen, treatment, immunotherapy

1. Introduction

Pythiosis is a life-threatening infectious disease [1,2,3,4,5,6,7] that has been increasingly reported in humans [8,9,10,11,12,13], horses [14,15,16,17,18,19], dogs [20,21,22,23], cats [24,25,26,27], camels [28,29], and some other animals [30,31,32,33,34] living in tropical and subtropical areas worldwide. The causative agent is the oomycete microorganism Pythium insidiosum, which inhabits water and moist soil [35,36,37,38,39,40]. Biflagellate zoospore is an infective stage of P. insidiosum that shows strong tropism to animal hairs and tissues [41,42]. Direct exposure to the pathogen habitat (i.e., stagnant water, rice field, pond) could increase the risk of the infection [43,44,45,46,47]. Patients with pythiosis usually manifest with clinical features associated with an infection of the skin [11,23,48,49], artery [13,50,51], eye [47,52,53,54], gastrointestinal tract [28,55,56,57], or another internal organ [5,12,58,59,60]. Diagnostic methods have been established for pythiosis [61], such as culture identification [62,63,64], histopathological examination [65,66,67,68], serological assays [69,70,71,72,73,74,75], molecular techniques [76,77,78,79,80,81,82], and proteomic analysis [83,84].

Prompt and effective treatment improves the patient’s prognosis [56,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94]. The use of conventional antifungal drugs provides limited efficacy in treating pythiosis because P. insidiosum lacks the drug-target sterol biosynthesis enzymes [95]. A few antibacterial drugs demonstrate a favorable outcome in some pythiosis patients [53,90,96,97]. However, several in vitro and in vivo studies show that these antimicrobial agents exhibit diverse inhibitory effects among different strains of P. insidiosum [98,99,100,101,102,103,104]. Therefore, radical surgery to remove all infected tissues is the primary treatment option for pythiosis [44,50,60,105,106]. However, the surgical procedure could be challenging and complex in some pythiosis patients with disseminated [12,43,58], cerebral [2,107,108], or complicated vascular infection [90,109,110]. Besides, pythiosis can recur post-surgically. New management tools to treat the infections caused by P. insidiosum are needed.

Alternative treatment options for pythiosis, i.e., biogenic silver nanoparticles (Ag-NP), photodynamic therapy (PDT), and ozone have been explored [111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118]. Valente et al. show that Ag-NP inhibits P. insidiosum in the rabbit model of pythiosis [112]. Pires et al. reveal that the photosensitizer-based PDT reduces the growth of P. insidiosum [114,115]. Ozone gas and ozonated sunflower oil inhibit the growth of P. insidiosum and cure some horses with pythiosis [116,117,118]. More studies are required to demonstrate the in vivo effectiveness and safety of Ag-NP, PDT, and ozone application against P. insidiosum. The P. insidiosum antigen (PIA) immunotherapy had been used for decades to cure pythiosis in different species [119,120,121,122,123]. The immunomodulating PIA is usually administered in combination with other therapeutic approaches (i.e., surgery and antimicrobial drugs) [13,106,109,121,124,125,126,127] and shows a favorable response in many pythiosis patients [13,119,128,129,130,131,132]. Nevertheless, the true therapeutic efficacy of PIA alone is unknown.

This review aims at providing up-to-date information of the immunotherapeutic PIA, with a focus on its history, preparation, clinical application, outcome, mechanism, and recent advances, in order to promote the proper use and future development of this treatment modality. The keywords “pythiosis” and “Pythium insidiosum” were used to search the literature (i.e., PubMed, SciELO, and Google Scholar) up until June 2021 for compiling relevant PIA information. Furthermore, the information relating to PIA was obtained from the Google patent database browser (https://patents.google.com/; accessed on 29 May 2021) and the United States Patent and Trademark Office website (https://www.uspto.gov/; accessed on 29 May 2021). In the last part, we prospected the future development for improving the effectiveness of the PIA immunotherapy.

2. History of the Immunotherapy Using P. insidiosum Antigens

The use of PIA in pythiosis immunotherapy was first reported in Australia in 1981 by Miller et al., who applied this treatment modality in affected animals since 1977 [119]. The PIA formulation containing cytoplasmic antigens (prepared by sonication of P. insidiosum hyphae) showed a cure rate of 53% (21 out of 40 affected horses) [119]. However, a calf with pythiosis was treated with the same PIA but showed no response [133]. Limitations of this antigen formulation include short shelf life (up to 8 weeks), unresponsiveness in cases with a long history of the P. insidiosum infection (i.e., 3.5 and 7 months), and skin reaction or sterile abscess at the injection site in 30–70% of the horses [119,126].

In 1986, Mendoza et al. reported a different PIA formulation for treating five horses with cutaneous pythiosis in Costa Rica [120]. Their formulation contains culture filtrate antigens (CFA; representing exoantigens or extracellular proteins) prepared by ether precipitation of P. insidiosum hyphae-removed culture broth [120]. It cured three out of five horses with pythiosis (60%), exhibited a relatively long shelf life (~8 months), and demonstrated minimal skin reaction with no sterile abscess at the injection site. However, it did not show any favorable response in the horses with chronic P. insidiosum infection [120].

In 1992, Mendoza et al. described two new PIA formulations for immunotherapy of equine pythiosis, so-called: (i) soluble concentrated antigen vaccine (SCAV) and (ii) cell mass vaccine (CMV) [123]. SCAV contains CFA from acetone precipitation of P. insidiosum hyphae-removed culture broth, whereas CMV contains antigens from homogenized P. insidiosum hyphae [123]. Compared with CMV, SCAV showed a higher cure rate [29 of 41 affected horses (71%) vs. 18 of 30 affected horses (60%)] and longer shelf life (18 months vs. 2–3 weeks). In addition, SCAV exhibited less skin reaction at the injection site than did CMV. Besides, sterile abscesses were noted in about half of 30 CMV-immunized horses [123]. Although SCAV improved the treatment outcome, it did not cure the horses with chronic pythiosis (a prolonged infection of more than 2 months) [123].

Western blot analysis of the cytoplasmic proteins of P. insidiosum, so-called soluble antigens from broken hyphae (SABH; prepared by sonication of hyphae), showed 3 major immunodominant antigens at the molecular weights of 28, 30, and 32 kDa [134,135]. Mendoza et al. added these antigens into SCAV (containing exoantigens) [135,136]. All antigens were prepared from the P. insidiosum isolate ATCC 74446 (also known as the isolate ATCC 58643 or CBS 574.85) [106,136]. The resulting PIA formulation showed enhanced efficacy, as it cured 13 out of 18 horses with cutaneous pythiosis (72%), including 5 horses with a chronic skin lesion of at least 4 months [121], and a human patient with vascular pythiosis [107]. From 6 dogs with cutaneous and intestinal pythiosis, it cured 2 cases (33%) while exhibited no favorable response in 4 cases (67%; including 4 dogs with a chronic lesion longer than 2 months) [121]. It cannot cure cutaneous pythiosis in a cat [137]. This PIA formulation, during its development, had been sequentially patented in 1999, 2001, 2004, and 2010 under the U.S. patent numbers 5948413, 6287573B1, 6833136B2, and 7846458B1, respectively [136,137,138], and was made commercially available in the United States by Pan American Veterinary Laboratories, Texas, USA [125,139,140,141].

In 2003, Santurio et al. developed and compared the efficacy of three PIA formulations, containing (i) vortexed (or macerated) [142,143], (ii) sonicated, or (iii) mixed (vortexed and sonicated) hyphal antigens of P. insidiosum, in the rabbit model of pythiosis [122]. The method used to prepare the sonicated antigens of Santurio et al. is similar to Miller’s, except the former lyophilized the extracted proteins to prolong the shelf life at room temperature [119,122]. The vortexed hyphal antigens were obtained by vortexing P. insidiosum hyphae in the presence of sulfuric ether [122]. After lyophilization, the vortex-derived PIA was stable for more than one year [122]. Using the rabbit model of pythiosis in a case-control study (four groups of five rabbits), the PIA formulation containing the vortexed hyphal antigens outperformed the placebo, and the PIA formulation containing sonicated or mixed hyphal antigens [122]. The rabbit group that received the vortexed antigens showed a 72% reduction in lesion size (compared with the lesion size before treatment), and 2 rabbits of this group were considered clinically and histologically cured. In contrast, the other groups of rabbits treated with placebo and other antigens had an enlarged lesion (up to 212% increase than the lesion size before treatment). Besides, the use of vortexed antigens was evaluated in 35 horses with pythiosis [144]. It showed no disease-prevention property while demonstrating a curative property in 74% of the affected horses with a recent or chronic lesion [144]. The PIA formulation containing vortexed antigens is commercially available by the Laboratório de Pesquisas Micológicas-Universidade Federal de Santa Maria (LAPEMI-UFSM), Brazil.

Later in 2011, Mendoza et al. modified their PIA formulation by using the P. insidiosum isolate MTPI-04 (type isolate: ATCC PTA-12166) as the antigen source and introducing a cryogenic method to disrupt the hyphal elements (i.e., grinding the hyphae in a mortar in the presence of liquid nitrogen) [145,146]. Western blot analysis showed that this PIA preparation contains the additional 124 kDa protein and a greater quantity of the 28 kDa protein [145,146]. In 2015, Permpalung et al. compared the efficacies of 2 PIA formulations prepared from different P. insidiosum isolates (MTPI-04 vs. ATCC 58643) in human patients with pythiosis [106]. Both PIA formulations, comprising CFA (extracellular antigens) and SABH (intracellular antigens), showed no significant differences in clinical outcomes for patients with vascular or ocular infection.

3. Preparation of P. insidiosum Antigens for Pythiosis Immunotherapy

Although the PIA formulations for pythiosis immunotherapy vary, all contain either extracellular proteins (so-called CFA, exoantigens, or secretory antigens) [43,61,107,121,131,135,136,137,138] and/or intracellular proteins (so-called cytoplasmic antigens or endoplasmic antigens) [43,61,121,136,137,138], extracted from a selected isolate of P. insidiosum, using a protocol of choice. In brief, the organism is cultured in a liquid medium (i.e., Sabouraud dextrose or nutrient broth), with or without shaking (100–150 rpm), at 37 °C for 5–10 days [119,120,122,123,136]. Growing P. insidiosum hyphae are harvested from the liquid culture by discarding the fluid [119] or filtrating through a membrane [123] to prepare cytoplasmic antigens. The remaining cell-free culture broth is collected for the preparation of exoantigens. The harvested P. insidiosum hyphae are ruptured to release the cytoplasmic antigens by using one of the following tools: cell homogenizer [123], sonicator [119,122,136], or vortex shaker [122]. The hyphal cell lysate (resuspended in water, saline, or phosphate-buffered saline pH 7.2) is centrifuged to collect the supernatant containing soluble cytoplasmic antigens [119,122,136,138]. As a part of exoantigen preparation, an appropriate amount of ether (i.e., an ether-to-broth ratio of 1:1) or acetone (i.e., an acetone-to-broth ratio of 1:1 or 2:1) is added to the cell-free culture broth to precipitate the extracellular proteins of P. insidiosum [120,123,136,138]. The precipitated exoantigens are collected by centrifugation.

Some investigators combined different antigens to formulate a new PIA. For example, Santurio et al. mixed the cytoplasmic antigens prepared by different methods (i.e., vortex and sonication) [122], whereas Mendoza et al. merged the cytoplasmic antigens and exoantigens extracted from the same isolate [136,138]. Inactivation of P. insidiosum, before or after the protein extraction, can be achieved using 0.02% thiomersal or 0.5% phenol [119,122,123,136]. Microbial contamination is checked by spreading 100 µL of the crude extracted proteins onto Sabouraud dextrose and blood agar plates before incubation at 37 °C for one week [119,123,136]. The obtained PIA can be kept at 4 °C for short-term storage (i.e., several weeks to months) or at freezing temperature (i.e., −21 or −80 °C) for a longer period [106,119,120,123,127,131,135,136]. Lyophilization can preserve the extracted antigens at room temperature for at least one year [122].

4. Clinical Application of Immunotherapy in Human Pythiosis

Primary clinical forms of human pythiosis include vascular pythiosis (an infection of a medium-to-large artery) and ocular pythiosis (an eye infection). A few patients come with cutaneous pythiosis (an infection of the skin) [43,147,148] or disseminated pythiosis (an infection of multiple organs) [12,43,60]. Surgical intervention is the primary treatment of pythiosis [13,61,106,109,127,132,149,150]. The therapeutic goal is to remove all infected tissues to achieve an organism-free surgical margin [13,90,106,109,151,152]. The first use of PIA immunotherapy in a human patient with pythiosis was reported in 1998 [107]. After being treated with PIA immunotherapy, this patient has recovered from the P. insidiosum infection of external and internal carotid arteries, where radical surgery is impossible. After excluding potentially-overlapping or clinical data-lacking cases (i.e., no treatment outcome), the literature search identified 108 patients with vascular pythiosis (Table 1), 35 patients with ocular pythiosis (Table 2), and 2 patients with a periorbital infection that received the PIA immunotherapy as an adjunctive treatment, together with antimicrobial drugs or surgery [2,7,13,43,90,106,107,108,109,131,132,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160]. The PIA formulation used in these patients contained both extracellular and intracellular proteins of P. insidiosum [136,137,138]. The final clinical outcomes of these 145 PIA-immunized patients were “cured” in 84.1% of cases (with or without losing an affected organ; n = 122) and “dead” in 15.9% of cases (n = 23).

Table 1.

Vascular pythiosis patients (147 cases) with or without the P. insidiosum antigen (PIA) immunotherapy, reported in the literature during 1989–2021.

| Authors | Year of Publication | Country | Study Period | Number of Vascular Cases | PIA-Immunized Cases | PIA-Unimmunized Cases | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Survived | Dead | Number | Survived | Dead | ||||||

| Sathapatayavongs et al. and Tanphaichitra et al. | 1989 | Thailand | (unknown) | 5 | - | - | - | 5 | 3 | 2 | [161,162] * |

| Chetchotisakd et al. | 1992 | Thailand | 1988–1989 | 4 | - | - | - | 4 | 2 | 2 | [163] |

| Wanachiwanawin et al. | 1993 | Thailand | 1983–1989 | 6 | - | - | - | 6 | 2 | 4 | [110] |

| Thitithanyanont et al. | 1998 | Thailand | 1995 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | [107] |

| Prasertwitayakij et al. | 2003 | Thailand | (unknown) | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | [51] |

| Wanachiwanawin et al. | 2004 | Thailand | 1998–2002 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 2 | - | - | - | [131] |

| Pupaibool et al. | 2006 | Thailand | (unknown) | 2 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | [154] |

| Laohapensang et al. | 2009, 2005 | Thailand | 2001–2004 | 7 | 1 | 1 | - | 6 | 5 | 1 | [50,153] * |

| Narkwiboonwong et al. | 2011 | Thailand | (unknown) | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | [108] |

| Salipante et al. | 2012 | USA | (unknown) | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | [155] |

| Keoprasom et al. | 2013 | Thailand | (unknown) | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | [157] |

| Schloemer et al. | 2013 | USA | (unknown) | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | [156] |

| Hahtapornsawan et al. | 2014 | Thailand | (unknown) | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | [158] |

| Pan et al. | 2014 | USA | (unknown) | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | [7] |

| Reanpang et al. and Sudjaritruk et al. | 2015, 2011 | Thailand | 2004–2014 | 22 | 18 | 14 | 4 | 4 | - | 4 | [149,152] * |

| Sermsathanasawadi et al. | 2016 | Thailand | 2005–2015 | 11 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 1 | - | 1 | [109] |

| Worasilchai et al. | 2018 | Thailand | 2010–2016 | 50 | 50 | 45 | 5 | - | - | - | [151] |

| Chitasombat et al. and Khunkhet et al. | 2018, 2015 | Thailand | 2006–2016 | 13 | 11 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | [2,13,159] * |

| Susaengrat et al. | 2019 | Thailand | (unknown) | 2 | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | - | [90] |

| Torvorapanit et al. | 2021 | Thailand | 2019–2020 | 9 | - | - | - | 9 | 8 | 1 | [164] |

| Total (%) | 147 | 108 (100%) |

87 (80.6%) |

21 (19.4%) |

39 (100%) |

23 (59.0%) |

16 (41.0%) |

||||

* These references contain overlapped cases.

Table 2.

Ocular pythiosis patients (168 cases) with or without the P. insidiosum antigen (PIA) immunotherapy, reported in the literature during 1993–2021.

| Authors | Year of Publication | Country | Study Period | Number of Cases | PIA-Immunized Cases | Clinical Outcome | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eye Saved | Eye Removed | |||||||

| Virgile et al. | 1993 | USA | 1989 | 1 | - | 1 | - | [165] |

| Murdoch et al. | 1997 | New Zealand | 1984 | 1 | - | - | 1 | [9] |

| Badenoch et al. | 2001 | Australia | (unknown) | 1 | - | 1 | - | [166] |

| Krajaejun et al. | 2004 | Thailand | 1985–2003 | 11 | - | 1 | 10 | [167] |

| Badenoch et al. | 2009 | Australia | (unknown) | 1 | - | 1 | - | [168] |

| Lekhanont et al. | 2009 | Thailand | (unknown) | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | [150] |

| Tanhehco et al. | 2011 | USA | (unknown) | 1 | - | - | 1 | [169] |

| Barequet et al. | 2013 | Israel | (unknown) | 1 | - | 1 | - | [170] |

| del Castillo-Jiménez et al. | 2013 | Spain | 2009 | 1 | - | - | 1 | [171] |

| Thanathanee et al. | 2013 | Thailand | 2009 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | [132] |

| Hung et al. | 2014 | Canada | (unknown) | 1 | - | - | 1 | [8] |

| Sharma et al. | 2015 | India | 2010–2012, 2014 | 11 | - | 9 | 2 | [172] |

| Lelievre et al. | 2015 | France | (unknown) | 1 | - | 1 | - | [173] |

| Ramappa et al. | 2016 | India | 2016 | 1 | - | 1 | - | [97] |

| He et al. | 2016 | China | (unknown) | 1 | - | 1 | - | [54] |

| Ros Castellar et al. | 2017 | Spain | (unknown) | 1 | - | 1 | - | [174] |

| Raghavan et al. | 2018 | India | (unknown) | 1 | - | 1 | - | [175] |

| Agarwal et al. | 2018 | India | 2014–2016 | 10 | - | 8 | 2 | [176] |

| Chatterjee et al. | 2018 | India | 2017 | 1 | - | 1 | - | [96] |

| Anutarapongpan et al. | 2018 | Thailand | 2009–2015 | 21 | - | 6 | 15 | [177] |

| Neufeld et al. | 2018 | USA | (unknown) | 1 | - | - | 1 | [178] |

| Rathi et al. | 2018 | India | (unknown) | 1 | 1 | - | 1 * | [1] |

| Maeno et al. | 2019 | Japan | (unknown) | 1 | - | 1 | - | [53] |

| Bernheim et al. | 2019 | France | (unknown) | 1 | - | 1 | - | [47] |

| Permpalung et al. | 2019 | Thailand | 2010–2016 | 30 | 30 | 16 | 14 | [127] |

| Wang et al. | 2020 | China | 2008–2017 | 4 | - | 1 | 3 | [179] |

| Puangsricharern et al. | 2021 | Thailand | 2006–2019 | 9 | - | 3 | 6 | [180] |

| Gurnani et al. | 2021 | India | 2017–2020 | 26 | - | 26 | - | [181] |

| Vishwakarma et al. | 2021 | India | 2016–2018 | 18 | - | 15 | 3 | [182] |

| Nonpassopon et al. | 2021 | Thailand | 2009–2019 | 6 | - | 5 | 1 | [183] |

| Total (%) | 168 (100%) |

35 (20.8%) |

104 (61.9%) |

64 (38.1%) |

||||

* Deceased.

Among 39 vascular pythiosis patients who did not receive PIA immunotherapy, the majority (59.0%; n = 23) survived the disease, while the remaining (41.0%; n = 16) died from an advanced infection (Table 1). On the other hand, from 108 vascular pythiosis patients who received the PIA immunotherapy, most cases (80.6%; n = 87) survived, whereas the rest (19.4%; n = 21) died (Table 1). Regardless of clinical settings (i.e., infection site and disease severity), PIA immunotherapy seemingly improved the survival rate by ~20% in patients with vascular infection. Clinical details (i.e., ages, genders, underlying conditions, extents of an affected artery, and clinical outcomes) were available from 105 vascular pythiosis patients with (67 out of 108 cases; 62.0%) and without (38 out of 39 cases; 97.4%) PIA immunotherapy (Table 3). Both groups showed comparable ages (years: 40.9 vs. 41.4), underlying illnesses (hematological diseases: 91.0% vs. 100.0%), infection sites (legs: 92.5% vs. 100.0%), and morbidity (amputations: 61.2% vs. 57.9%). The overall mortality rate of the patients with PIA immunotherapy (29.9%) was lower than those without (42.1%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical details and treatment outcomes of vascular pythiosis patients with (67 cases) or without (38 cases) the P. insidiosum antigen (PIA) immunotherapy.

| Clinical Features Presented as % [Case Ratio] |

PIA-Immunized Cases (n = 67) |

PIA-Unimmunized Cases (n = 38) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Age (years) | 40.9 (range: 10–75) | 41.4 (range: 17–73) |

| 2. Male:Female | 5:1 | 2.4:1 |

| 3. Underlying hematologic disorder | 91.0 [61/67] | 100.0 [38/38] |

| 4. Infection site | ||

| Head and neck | 6.0 [4/67] | - |

| Upper limb | 1.5 [1/67] | - |

| Lower limb | 92.5 [62/67] | 100.0 [38/38] |

| Aorta/Iliac artery | 33.9 [21/62] | 44.7 [17/38] |

| Femoral/Popliteal artery | 53.2 [33/62] | 52.6 [20/38] |

| Tibial/Peroneal/Dorsalis pedis | 12.9 [8/62] | 2.6 [1/38] |

| 5. Limb amputation | ||

| Survived | 61.2 [41/67] | 57.9 [22/38] |

| Dead | 23.9 [16/67] | 31.6 [12/38] |

| 6. No surgical amputation | ||

| Survived | 9.0 [6/67] | 0.0 [0/38] |

| Dead | 6.0 [4/67] | 10.5 [4/38] |

| 7. Mortality rate based on infection site | ||

| Overall | 29.9 [20/67] | 42.1 [16/38] |

| Head and neck | 50.0 [2/4] | - |

| Upper limb | 0.0 [0/1] | - |

| Lower limb | 29.0 [18/62] | 42.1 [16/38] |

| Aorta/Iliac artery | 61.9 [13/21] | 88.2 [15/17] |

| Femoral/Popliteal artery | 15.2 [5/33] | 5.0 [1/20] |

| Tibial/Peroneal/Dorsalis pedis | 0.0 [0/8] | 0.0 [0/1] |

| 8. Disease duration before treatment | (n = 51) * | (n = 34) * |

| ≤2 months | 28.6 [6/21] | 25.0 [5/20] |

| >2 months | 33.3 [10/30] | 50.0 [7/14] |

* The number of cases whose data about disease duration before initiation of the treatment are available.

The P. insidiosum infection usually progresses along an affected artery from the distal to the proximal part of the leg. Pythiosis involving the aorta and iliac artery possessed a remarkably high mortality rate of 88.2% in the patients without PIA immunotherapy and a relatively lower rate of 61.9% in the patients with such treatment (Table 3). Regardless of PIA immunotherapy, the mortality rate appeared to be lower (up to 15.2%) in the pythiosis patients with an infection of a lower-level artery, such as femoral, popliteal, tibial, peroneal, and dorsalis pedis arteries. Six PIA-immunized patients survived vascular pythiosis without leg amputations [13,106,107,131] (Table 3).

Concerning the disease duration, up to 2 months before treatment, the PIA-immunized and PIA-unimmunized vascular pythiosis patients showed similar mortality rates (28.6% vs. 25.0%; Table 3). However, if the disease duration was longer than 2 months (described as chronic infection by Mendoza et al. [121]), the PIA-immunized patients had ~17% lower mortality rate than the PIA-unimmunized cases (33.3% vs. 50.0%; Table 3). Thus, a longer disease duration could lead to a higher mortality rate, and PIA immunotherapy could notably reduce disease mortality in patients with a chronic P. insidiosum infection.

Because the PIA-immunized patients usually obtained a combination treatment (including surgery and antimicrobial agents), the sole immunotherapy efficacy against P. insidiosum cannot be evaluated directly. The PIA-immunized patients with a marked inflammatory reaction (i.e., local swelling, pruritus, and erythema at the injection site and regional lymphadenopathy) showed a more favorable treatment outcome than patients with minimal or no such reaction [106,107,131,157]. Several serum markers, such as β-D-glucan (BDG), anti-P. insidiosum antibodies, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP), have been used to monitor the clinical course of some vascular pythiosis patients [90,151,164]. A declining level of BDG [90,151], ESR [164], or CRP [164] links with a recovery condition in the course of pythiosis treatment. Lower serum BDG and higher anti-P. insidiosum antibodies are associated with a better prognosis [151].

Similar to vascular pythiosis, surgical intervention is also the primary option for treating ocular pythiosis [132,150,167,177,180,181,184,185]. Topical or systemic antimicrobial agents (including linezolid, azithromycin, itraconazole, terbinafine, amphotericin B, natamycin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline) were administered in the ocular cases [97,106,174,180,181,182,186,187]. In addition, many ocular pythiosis patients underwent penetrating keratoplasty to save the affected eye [53,54,91,165,166,168,170,173,176,183]. Post-keratoplasty recurrent infection resulted in eye removal by evisceration or enucleation [66,91,150,176,184]. In addition to the surgical and medical treatments, PIA was administered to modulate the immune response in 35 out of 168 ocular pythiosis patients (20.8%; one of which had bilateral ocular infections) [1,106,127,132,150,180] and 2 out of 5 periorbital pythiosis patients (40.0%) [43,160] (Table 2). The affected eye was removed in 17 out of 35 PIA-immunized (48.6%) and 47 out of 133 PIA-unimmunized (35.3%) patients (Table 2). Regarding the patients with periorbital pythiosis (n = 5), one of the two cases with, and all three cases without, PIA immunotherapy survived the disease. One each of the ocular and periorbital pythiosis patients, who obtained PIA immunotherapy, died due to an invasive infection [1,43]. Based on these reports, the PIA immunotherapy may not provide an advantage in a local P. insidiosum infection of the eye.

Administration of the PIA immunotherapy for pythiosis patients (i.e., antigen concentration, injection site, number of doses, and duration between shots) can differ based on the clinician’s judgment and PIA availability. The immunotherapeutic PIA is generally prepared to the final concentration of 2 mg/mL [90,106,107,127,131,132,151,180]. Either 0.1–0.2 mL [43,106,107,131,132] or 1.0 mL [90,106,109,151,180] of PIA per dose is injected subcutaneously at least 2 times: initial and subsequent time points (i.e., 0.5, 1, 1.5, 3, 6, and 12 months) [13,43,61,106,107,109,127,131,132,149,151,180]. In some cases, the first PIA dose was provided intradermally [106,131]. Several patients with an aggressive P. insidiosum infection obtained a PIA injection once a week up to 7 weeks [7,106,156]. Sermsathanasawadi et al. describe the immunotherapy outcome of some patients with vascular pythiosis and recommend to provide an affected patient 3 PIA injections at days 0, 7, and 21 [109].

5. Immunotherapy Using P. insidiosum Antigen in Animals with Pythiosis

Initially, PIA was formulated and modified to increase its clinical efficacy in the immunotherapy of horses with pythiosis [119,120,121,122,123,188,189,190]. Besides, PIA has been used to treat the disease in other animals, such as dogs [121,125,129,140,141,191,192], camels [29,124], calves [130,133], sheep [193], cats [25,27,137,194], and a donkey [128] (Table 4). Several reports show that PIA immunotherapy, used as the primary treatment, can cure pythiosis in animals [128,130,192,193,195]. However, many affected animals required such immunotherapy combined with surgical and antimicrobial treatments [124,126,128,129,140]. In general, clinical outcomes can vary among the animals with pythiosis who received PIA immunotherapy, either alone or in combination with other treatments. In most cases, PIA (1.0–2.5 mL/dose) was injected subcutaneously, every 7–15 days, usually until the lesion resolved [25,118,124,128,129,130,140,193,195,196,197]. Some infected animals received the first dose of PIA intradermally and the subsequent doses subcutaneously [121,192]. The immunotherapeutic PIA can be injected at the pectoral muscle [119,123,126,198,199], neck [120,121,123,144,197], or shoulder [192] of an animal. A mild-to-extended inflammatory reaction can be noticed at the injection site [29,192,197,198,199].

Table 4.

Animals with pythiosis (270 cases) receiving the P. insidiosum antigen (PIA) immunotherapy during 1981–2021.

| Authors | Year of Publication | Country | Study Period | Affected Animal | Infected Tissue | PIA-Immunized Cases | Clinical Outcome | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cured | Unresponsive or Dead | ||||||||

| Miller RI. | 1981 | Australia | 1977–1981 | Horse | Skin | 40 | 33 | 7 | [119] |

| Miller et al. | 1983 | USA | (unknown) | Horse | Skin | 5 | 1 | 4 | [126] |

| Miller et al. | 1985 | USA | 1983 | Calf | Skin | 1 | - | 1 | [133] |

| Mendoza et al. | 1992 | Costa Rica | 1982–1988 | Horse | Skin | 71 | 47 | 24 | [123] |

| Duncan et al. | 1992 | USA | (unknown) | Cat | Skin | 1 | - | 1 | [27] |

| Eaton SA. | 1993 | USA | (unknown) | Horse | Skin, Bone | 1 | - | 1 | [198] |

| Thomas et al. | 1998 | USA | (unknown) | Cat | Skin | 1 | - | 1 | [194] |

| Dowling et al. | 1999 | Australia | (unknown) | Horse | Skin | 2 | 1 | 1 | [199] |

| Dykstra et al. | 1999 | USA | 1985–1995 | Dog | Skin | 2 | - | 2 | [191] |

| Santurio et al. | 2001 | Brazil | 1996–1997 | Horse | Skin | 35 | 26 | 9 | [144] |

| Reis et al. | 2003 | Brazil | 1996–1999 | Horse | Skin, Lung, Liver | 1 | - | 1 | [58] |

| Hensel et al. | 2003 | USA | (unknown) | Dog | Skin | 1 | 1 | - | [192] |

| Mendoza et al. | 2003 | USA | (unknown) | Horse | Skin | 18 | 13 | 5 | [121] |

| Dog | Skin | 5 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Dog | Intestine | 1 | - | 1 | |||||

| Wellehan et al. | 2004 | USA | (unknown) | Camel | Skin | 1 | - | 1 | [29] |

| Mendoza et al. | 2004 | USA | (unknown) | Cat | Skin | 1 | - | 1 | [137] |

| White et al. | 2008 | USA | (unknown) | Horse | Skin | 1 | - | 1 | [139] |

| de Faria Maciel et al. | 2008 | Brazil | 2006–2007 | Horse | Skin | 1 | - | 1 | [200] |

| Frey Jr. et al. | 2007 | Brazil | 2004–2005 | Horse | Skin, Bone | 10 | 5 | 5 | [201] |

| Bandeira et al. | 2009 | Brazil | (unknown) | Horse | Skin | 1 | - | 1 | [202] |

| dos Santos et al. | 2011 | Brazil | 2007–2009 | Donkey | Skin | 1 | - | 1 | [128] |

| de Avila et al. | 2011 | Brazil | 2010 | Horse | Skin | 1 | 1 | - | [197] |

| Schmiedt et al. | 2012 | USA | (unknown) | Dog | Intestine | 1 | 1 | - | [140] |

| Videla et al. | 2012 | USA | 2009 | Camel | Skin | 2 | 1 | 1 | [124] |

| Pereira et al. | 2013 | Brazil | (unknown) | Dog | Intestine | 1 | 1 | - | [129] |

| Carrera et al. | 2013 | Brazil | 2011 | Sheep | Nasal | 6 | 1 | 5 | [193] |

| dos Santos et al. | 2014 | Brazil | 2007–2010 | Horse | Skin | 47 | 38 | 9 | [46] |

| Oldenhoff et al. | 2014 | USA | 2012 | Dog | Skin | 1 | - | 1 | [141] |

| Grant et al. | 2016 | USA | (unknown) | Calf | Skin | 1 | 1 | - | [130] |

| Gaddis et al. | 2017 | USA | (unknown) | Dog | Skin | 1 | - | 1 | [125] |

| Silva et al. | 2018 | Brazil | (unknown) | Horse | Skin | 1 | - | 1 | [203] |

| Dowst et al. | 2019 | USA | (unknown) | Cat | Skin | 1 | - | 1 | [25] |

| Parambeth et al. | 2019 | USA | (unknown) | Dog | Intestine | 1 | - | 1 | [57] |

| Di Filippo et al. | 2020 | Brazil | (unknown) | Horse | Skin, Bone | 1 | - | 1 | [204] |

| Cridge, et al. | 2020 | USA | 2018–2019 | Dog | Intestine | 1 | 1 | - | [205] |

| da Paz et al. | 2021 | Brazil | 2018 | Horse | Skin | 3 | 2 | 1 | [118] |

| Total (%) | 270 (100%) |

176 (65.2%) |

94 (34.8%) |

||||||

By excluding overlapping and clinical data-lacking cases, a total of 270 animals with pythiosis (including 239 horses, 15 dogs, 6 sheep, 4 cats, 3 camels, 2 calves, and a donkey), who received the PIA immunotherapy, were identified in the literature (Table 4). The horse is the most affected species for pythiosis. All 239 horses immunized with PIA had a P. insidiosum infection of the skin (several cases had a co-infection of bone, lung, or liver) (Table 4 and Table 5), 167 of which (69.9%) were clinically cured with (38 from 167 cured cases; 22.8%) or without (129 from 167 cured cases; 77.2%) a surgical intervention. For comparison, of 170 PIA-unimmunized horses with pythiosis (Table 5), 125 (73.5%) were cured with (94 from 125 cured cases; 75.2%) or without (31 from 125 cured cases; 24.8%) surgery. Regarding dogs with cutaneous or gastrointestinal pythiosis, the clinical cure was observed in 6 out of 15 PIA-immunized cases (40.0%) and 17 out of 75 PIA-unimmunized cases (22.7%) (Table 4 and Table 5). Relatively low clinical efficacy of the PIA immunotherapy was observed in other animals (Table 4). For example, only 1 out of 6 sheep (16.7%) [193], 1 out of 3 camels (33.3%) [29,124], and 1 out of 2 calves (50.0%) [130,133] were cured of pythiosis. Besides, the PIA immunotherapy provided a negative response in 4 cats and a donkey with cutaneous pythiosis (Table 4). Notably, the clinical cure was observed in 127 out of 128 infected cows without PIA immunotherapy (99.2%) (Table 5). It should be noted that a recurrent P. insidiosum infection was observed in some PIA-immunized horses previously cured of pythiosis [128,206], suggesting that the natural infection and PIA may not induce adequate or sustainable protective immunity [144].

Table 5.

Treatment outcomes of pythiosis in animals with (270 cases) or without (377 cases) the P. insidiosum antigen (PIA) immunotherapy.

| Animal Species | PIA-Immunized Cases | PIA-Unimmunized Cases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Cases | Cured | Unresponsive or Dead | Number of Cases | Cured | Unresponsive or Dead | References | |

| Horses | 239 (100%) |

167 (69.9%) |

72 (30.1%) |

170 (100%) |

125 (73.5%) |

45 (26.5%) |

[19,46,49,58,87,89,92,93,94,105,118,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214] |

| Dogs | 15 (100%) |

6 (40.0%) |

9 (60.0%) |

75 (100%) |

17 (22.7%) |

58 (77.3%) |

[6,20,21,23,45,55,56,85,141,191,205,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224,225,226,227,228,229,230,231,232,233,234,235] |

| Cows | 2 (100%) |

1 (50.0%) |

1 (50.0%) |

128 (100%) |

127 (99.2%) |

1 (0.8%) |

[133,236,237,238,239,240,241] |

| Sheep | 6 (100%) |

1 (16.7%) |

5 (83.3%) |

1 (100%) |

- | 1 (100.0%) |

[193] |

| Cats | 4 (100%) |

- | 4 (100.0%) |

2 (100%) |

1 (50.0%) |

1 (50.0%) |

[48,194] |

| Donkeys | 1 (100%) |

- | 1 (100.0%) |

1 (100%) |

1 (100.0%) |

- | [44] |

| Camels | 3 (100%) |

1 (33.3%) |

2 (66.7%) |

- | - | - | [29,124] |

| Total | 270 (100%) |

176 (65.2%) |

94 (34.8%) |

377 (100%) |

271 (71.9%) |

106 (28.1%) |

|

Regardless of the clinical condition and management, the horses receiving PIA immunotherapy showed a slightly lower cure rate than those not receiving such treatment (69.9% vs. 73.5%) (Table 5). In contrast, the PIA-immunized dogs exhibited a markedly higher cure rate than the PIA-unimmunized cases (40.0% vs. 22.7%) (Table 5). Some animal species (i.e., sheep, camel, cat, and donkey), those that appeared to be less affected by P. insidiosum, had a relatively low favorable response (from none to 33.3%) to PIA immunotherapy. From 130 recruited cows with pythiosis, only 2 were treated with PIA, resulting in 1 cured case (Table 5). Notably, most infected cows (127 from 128 cases; 99.2%) were spontaneously recovered from pythiosis, suggesting a potent host immunity against P. insidiosum generated in this particular animal species. A question has arisen concerning the immunotherapy efficacy since the overall cure rate for the infected animals who received PIA (as a part of their treatments) was lower than those who did not receive the antigen: 65.2% (176 in 270 cases) vs. 71.9% (271 in 377 cases) (Table 5). However, it is uncertain whether the clinical conditions of the affected animals with PIA immunotherapy were more severe than those without it, resulting in a relatively worse prognosis. Nevertheless, among the horses who were cured of pythiosis, it appears that the surgical interventions took place in 75.2% of the PIA-unimmunized cases. The rate of such interventions dropped to 22.8% in the PIA-immunized horses, suggesting PIA immunotherapy could reduce disease morbidity. As with human pythiosis, unless there is a case-control study, the favorable efficacy of PIA immunotherapy in animals cannot be directly assessed due to the different clinical settings among the cases, such as underlying condition, disease onset, severity, lesion size, pathologic location, and choices of treatment.

6. Proposed Mechanism of P. insidiosum Antigen-Based Immunotherapy

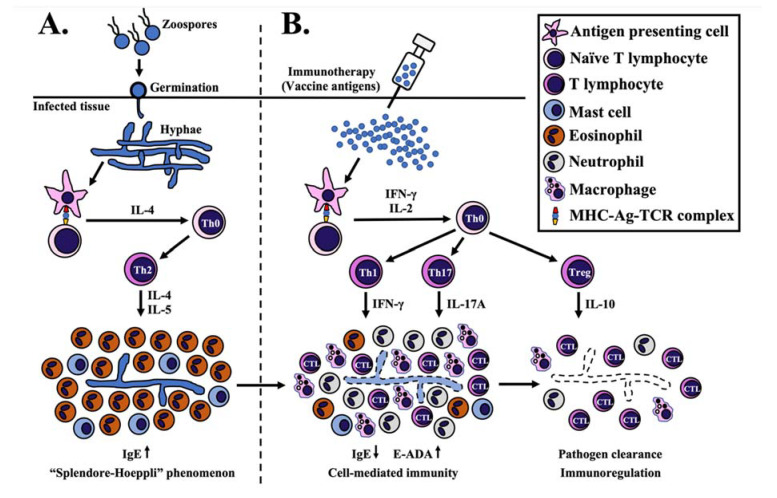

During the P. insidiosum infection, an antigen-presenting cell (APC), such as a dendritic cell, could process and present a pathogen antigenic epitope (via major histocompatibility complex or MHC) to a naïve T cell (through T-cell receptor or TCR). Such APC-T cell interaction induces differentiation and clonal proliferation of a naïve CD4+ T (Th0) cell to T helper-2 (Th2) cells [142,242,243,244]. An elevated level of IL-4 is responsible for the differentiation and proliferation of Th2 cells, which, in turn, secretes IL-5 for activating eosinophils [131,142,245,246]. This process leads to the non-protective Th2-mediated immunity, where eosinophils are predominantly recruited, together with other cell types, such as mast cells, neutrophils, giant cells, and plasma cells, into the infection area [18,28,66,160,199,217,247]. The eosinophils surround the P. insidiosum hyphae inside necrotic tissues, producing the histological phenomenon called “Splendore-Hoeppli” [49,105,248,249,250]. P. insidiosum might employ the accumulated eosinophilic materials as a protective shield against host immunity [122].

The PIA immunotherapy shows a favorable response in some humans and animals with pythiosis [46,106,129,130,131,180]. The mechanism of PIA action in pythiosis treatment is not clearly understood. However, recovery of the PIA-immunized humans and animals from pythiosis is associated with switching Th2 to T helper-1 (Th1) mediated immunity [131,142,244,251,252]. An APC should process an immunomodulating antigen of P. insidiosum, such as (1,3)(1,6)-β-glucan, which is a main cell wall component [251,253,254], before priming a resulting antigenic epitope to a naïve T cell (via MHC-TCR complex) [242,243]. This cellular interaction might trigger the release of IFN-γ and IL-2 for enhancing the differentiation of Th0 to Th1 cell and Th0 to regulatory T (Treg) cell, respectively [242,246,251,252,255,256]. The Th1 cell produces IFN-γ to activate the macrophages and cytotoxic T lymphocytes [131,142,242,244,246,251,253,256]. The PIA raises the T helper-17 (Th17) cells, which secrete IL-17A to recruit neutrophils and macrophages into the infected tissue [242,243,246,251,252,253]. The PIA could also promote the release of the IL-10 cytokine, which relates to the anti-inflammatory and immunoregulation activity of Treg cells [242,246,251,252,253,256]. In the rabbit model of pythiosis, the PIA elevates ecto-adenosine deaminase (E-ADA), which could stimulate the purinergic signaling system and promote the Th1-mediated immunity [257,258,259]. After PIA immunotherapy, histological findings at the infection site include the recruitment of lymphocytes, the gradual absence of eosinophils, and the reduced tissue burden of P. insidiosum hyphae [121,122,250,257]. The immunoglobulin E (IgE), which is increased during the P. insidiosum infection, is then decreased following the immunotherapy [121,131,244]. Taken together, the proposed P. insidiosum clearance mechanism of PIA immunotherapy is summarized in Figure 1 [131,142,242,244,251,253,259]. The in-depth mechanism of the immunomodulating PIA action in pythiosis treatment needs further investigation.

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanism of P. insidiosum antigen (PIA) immunotherapy. (A) P. insidiosum’s zoospores (asexual stage) attach and germinate as hyphae into the host tissue during natural infection. Antigen-presenting cells (APC) process and present the P. insidiosum antigens to naïve T lymphocytes via major histocompatibility complex-antigen-T cell receptor complex (MHC-Ag-TCR). This interaction elevates some cytokines (mainly IL-4) to differentiate and clonally proliferate a naïve CD4+ T (Th0) to T helper-2 (Th2) cell, which, in turn, produces IL-4 and IL-5 to attract and activate eosinophils and mast cells. The eosinophils surround the P. insidiosum, creating the histological phenomenon called “Splendore-Hoeppli”. (B) Processed antigens (prepared from the crude extract of P. insidiosum) lead to forming the MHC-Ag-TCR complex that induces the release of some cytokines, mainly IFN-ϒ and IL-2. IFN-ϒ promotes differentiation and clonal proliferation of a Th0 to T helper-1 (Th1) cell. Th1 cell-produced IFN-ϒ attracts macrophages and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) to the infection site for eliminating the pathogen. The MHC-Ag-TCR complex also facilitates the differentiation of a Th0 to T helper 17 (Th17) cell to produce IL-17A and accumulate more macrophages and neutrophils at the infection area. On the other hand, IL-2 promotes the differentiation of a Th0 to regulatory T (Treg) cell to regulate or suppress an excessive immune response through the release of IL-10. See the text for the details and the references to the proposed mechanism of PIA immunotherapy.

The PIA immunotherapy can cure many affected human and animal patients with pythiosis [13,106,149]. However, several pieces of evidence indicate that the host immunity induced by PIA could not prevent the P. insidiosum infection [46,121,122,144]. For example, Santurio et al. demonstrate no difference in the incidences of pythiosis between PIA-immunized and PIA-unimmunized horses [144]. Besides, several reports show that pythiosis can recur in recovered patients with or without PIA immunotherapy [45,123,125,188,206]. These findings suggest that the host immunity, induced by either immunotherapy or natural infection, may be inadequate in preventing another episode of P. insidiosum infection. Nevertheless, P. insidiosum reinfection could induce a stronger host immune response (i.e., a higher level of IgG antibodies) than the previous infection [206]. In patients with a persistent infection, the immunotherapy-induced antibody level could be affected by several factors, including host immune status, underlying diseases, and severity of the infection [2,106,201,204]. Although a high level of the anti-P. insidiosum antibodies generated by immunotherapy or natural infection is associated with the ability to eliminate the pathogen, the antibodies can be gradually decreased over time to a low or undetectable level [107,131,134,206], explaining the limited protective immunity against reinfection.

7. Future Perspective

Pythiosis has high mortality and morbidity. For decades several immunotherapeutic antigen formulations, prepared from crude extracts of P. insidiosum, have been used in the management of human and animal pythiosis [1,25,29,106,107,109,119,129,130,131,132,149,180,188,189,190,193,239,260]. However, a prophylactic approach to prevent the infection has yet to be developed. Clinical pieces of evidence show that the PIA immunotherapy can cure some, but not all, humans and animals with pythiosis [13,131,149,151]. The PIA immunotherapy, mostly in conjunction with surgery and antimicrobial drugs, demonstrates different clinical outcomes from study to study, likely depending on the severity of the P. insidiosum infection, host immune status, PIA formulations, the strain used for antigen preparation, and affected host species (i.e., human, horse, dog, cat, and cattle). Understanding how the PIA modulates the host immune responses to eliminate P. insidiosum could lead to developing more effective immunotherapy and, therefore, improving pythiosis patients’ clinical outcomes.

Information on the efficacy of PIA immunotherapy against pythiosis has been obtained, based mainly on clinical observation of the affected patients. However, no case-control clinical trial study has been conducted to comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of such a treatment modality, partly because pythiosis is a relatively rare disease. Therefore, a multicentric prospective clinical study should be performed to gain insights into the pharmacologic properties of PIA, such as efficacy, adverse effect, optimal dose, and antigen administration. The rabbit model of pythiosis has been established to investigate PIA immunotherapeutic properties [122,250,255,261]. Such an animal model shows atypical manifestations (i.e., cutaneous nodules) compared with pythiosis in the natural hosts (i.e., humans and various animals) [50,97,122,216,224,262,263,264]. Besides, housing the experimental rabbits comes at a high cost, demanding space, facilities, and skilled personnel. These drawbacks impede the use of this model in the evaluation of PIA immunotherapy. On the other hand, the mouse is a well-studied model for the immunological study of many infectious diseases [265,266,267]. Reproduction of the P. insidiosum infection in mice is possible but requires pre-treatment with an immunosuppressive agent (i.e., cyclophosphamide) [251,268,269], making this versatile animal model less suitable for the PIA assessment. A murine model of Leishmaniasis (rather than pythiosis) has been developed to evaluate the immunomodulatory properties of PIA, but it does not demonstrate a direct immunological effect of PIA on P. insidiosum clearance [256]. Finding a clinically relevant, and cost-effective, animal model would advance our understanding of the properties of the immunotherapeutic PIA.

In the fight against fungal pathogens, several sources of antigens have been under development and assessment, such as live-attenuated or killed organisms, crude fungal extracts, purified or recombinant antigens (i.e., proteins, peptides, carbohydrates, and lipids), and nucleic acids (i.e., DNA and RNA) [242,270]. Regarding the P. insidiosum infection, only the crude extract antigens, prepared in several different formulations (i.e., CFA and SABH), are available for immunotherapy of pythiosis. The heat-inactivated organism (i.e., P. insidiosum zoospores) has been explored for its in vitro property to stimulate host immunity [252]. A handful of antigens that induce the host immune responses to P. insidiosum (so-called immunogens or immunodominant antigens) have been identified by many investigators [37,134,145,271,272,273,274,275,276,277,278,279,280,281]. Reported immunogen profiles are generally inconsistent because different techniques, P. insidiosum isolates, and serum samples, were employed (Table 6). Identities, functions, and cellular locations of most immunogens have not been characterized. Recently, Chechi et al. used two-dimensional immunoblotting and mass spectrometry to identify several immunogens (i.e., HSC70, HSP70, exo-1,3-ß-glucanase, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, and aconitate hydratase) recognized by sera from humans and horses with pythiosis [278]. The P. insidiosum genome data [282,283,284,285,286,287] makes it possible to clone the coding sequence for recombinant protein production or synthesize an immunoreactive peptide of the identified immunogens. Several P. insidiosum proteins, such as exo-1,3-beta-glucanase (Exo1), elicitin (ELI025), and OPEL-like protein (I06), have been successfully cloned, expressed, and purified from bacterium-based, and cell-free, protein biosynthesis systems [275,277,279,288]. These recombinant proteins could serve as unlimited reproducible antigen sources for the future development of a protein subunit for preventing and treating pythiosis.

Table 6.

Immunodominant antigens identified in P. insidiosum by Western blot analysis.

| Authors | Year of Report | Type of Antigen * | Source of Antigen or Isolate (Number, Country) ** | Source of Pythiosis Sera (Number; Country) *** | The Molecular Weight of Immunogen (kDa) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mendoza et al. | 1992 | SABH | Horses (4, Australia, Costa Rica, Japan, USA); Human (1, Thailand) |

Horses (5, Costa Rica) | 28, 30, 32 | [134] |

| Vanittanakom et al. | 2004 | CFA | Human (1, Thailand) | Human (1, Thailand); Rabbit (1, unknown) | 23, 26, 28–30, 42–35, 56, 73, 110 | [276] |

| Leal et al. | 2005 | SABH | Horse (1, Brazil) | Horses (3, Brazil); Cows (2, Brazil); Rabbits (2, unknown) | 33.5, 35, 38, 39, 40, 70, 80 | [273] |

| Perez et al. | 2005 | SABH | Horse (1, Costa Rica) | Calves (57, Venezuela) | 30–32, 51–203 | [274] |

| Krajaejun et al. | 2006 | CFA, SABH | Humans (16, Thailand) | Humans (12, Thailand) | 34–43, 74 | [271] |

| Supabandhu et al. | 2008 | CFA | Environment (7, Thailand) | Rabbit (1, unknown) | 35–40, 70 | [37] |

| Chindamporn et al. | 2009 | SABH | Horses (4, New Guinea, Australia, Costa Rica, USA); Humans (2, Thailand) |

Human (1, USA); Humans (2, Thailand); Horses (2, USA); Horse (1, Costa Rica); Dogs (3, USA); Cows (3, Venezuela); Cats (3, USA) |

23, 28, 30, 32, 34, 41, 46, 49, 51, 60, 74, 76, 78, 80, 124, 209 | [145] |

| Lerksuthirat et al. | 2015 | Recombinant ELI025 protein |

E. coli-based protein synthesis |

Humans (3, Thailand); Rabbit (1, unknown) |

12.4 | [279] |

| Keeratijarut et al. | 2013, 2015 | Exo1 peptides | Peptide synthesis (Peptide-A and -B) |

Humans (34, Thailand) | (14, 15 amino acids) | [280,281] |

| Dal Ben et al. | 2018 | SABH | Horses (20, Brazil); Dogs (2, Brazil) |

Horse (1, Brazil); Dog (1, Brazil); Cow (1, Brazil); Rabbit (1, unknown) |

24, 34, 50–55, 60 | [272] |

| Sae-Chew et al. | 2020 | Synthesized I06 protein | Cell-free protein synthesis |

Humans (21, Thailand) | 55 | [275] |

| Rotchanapreeda et al. | 2020 | Recombinant Exo1 protein |

E. coli-based protein synthesis |

Humans (12, Thailand) | 82 | [277] |

| Chechi et al. | 2021 | SABH | Horse (1, Brazil) | Horses (22, Brazil); Humans (10, Thailand) |

25, 28, 31, 35, 37, 38, 43, 48, 53, 57, 63, 68, 69, 86, 88 | [278] |

* CFA (culture filtrate antigens) represents extracellular proteins; SABH (soluble antigens from broken hyphae) represents intracellular proteins. ** Number and geographic distribution (countries) of P. insidiosum isolated from humans and animals with pythiosis and used to prepare CFA and SABH for Western blot and ELISA analyses. *** Number and geographic distribution (countries) of pythiosis sera, derived from humans and animals with pythiosis, and used for Western blot and ELISA analyses.

Because pythiosis has been increasingly reported worldwide, the disease has become a global healthcare concern. The causative agent, P. insidiosum, colonizes ubiquitously on a water plant in the environment [36,37,41]. Once an individual comes in contact with the organism in its habitat, the infection can be initiated, causing a difficult-to-treat disease. The pathological structure called “kunker” formed in P. insidiosum-infected animal tissue can give rise to a propagating organism upon exposure to water [42]. Outbreaks of pythiosis have been reported in animals [118,239,240,274] due to the interplay between humans, animals, plants, and their environment. One Health-based approach (as described by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/; accessed on 22 August 2021) should be incorporated into preventive and control measures to promote an optimal health outcome for patients with pythiosis.

Pythiosis is a neglected tropical disease with high morbidity and mortality, in which clinical information on the disease and availability of the preventive, diagnostic, and therapeutic tools are limited. The disease can be considered a part of the Sustainable Developments Goals (SDGs) defined in the United Nations Development Program (https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals/; accessed on 22 August 2021). This review article presents the up-to-date information of the immunotherapeutic PIA for the proper use and future development of this treatment measure, aiming to promote good health and well-being of affected patients. The current formulation of PIA can mitigate morbidity and mortality in humans and animals with pythiosis by reducing surgical intervention and increasing the cure rate. However, more work needs to be done to improve the PIA efficacy in the prevention and treatment of pythiosis.

8. Conclusions

The fungus-like organism P. insidiosum causes pythiosis, a high morbidity and mortality disease, in humans and animals worldwide. As a part of the treatment, many pythiosis patients received the immunotherapeutic PIA. Only the PIA formulation containing the crude antigenic extracts of P. insidiosum has been clinically used over the past decades. Based on 967 documented human and animal pythiosis cases, PIA immunotherapy reduced disease morbidity and mortality. As the final clinical outcomes, 19.4% of PIA-immunized human patients succumbed to vascular pythiosis instead of 41.0% in unimmunized cases. PIA immunotherapy may not provide an advantage in a local P. insidiosum infection of the eye. Both PIA-immunized and unimmunized horses with pythiosis showed a similar survival rate of ~70%; however, demands for surgical intervention were much lesser in the immunized cases who were cured (22.8% vs. 75.2%). A case-control clinical trial study should be conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of immunotherapy for pythiosis. The proposed mechanism of the PIA action involves switching the non-protective Th2 to curative Th1 mediated immunity against P. insidiosum. Finding a clinically relevant, and cost-effective, animal model of pythiosis is necessary to advance our understanding of the underlying mechanism and the required component of the immunotherapeutic PIA. By exploring the available P. insidiosum genome data, synthetic peptides, recombinant proteins, and nucleic acids are potential sources of the immunomodulating antigens worth investigating. The PIA therapeutic property needs improvement for a better prognosis of pythiosis patients.

Author Contributions

H.Y., T.K.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Visualization; T.K.: Supervision; H.Y.: Writing—original draft; T.K.: Writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Faculty of Graduate Studies, Mahidol University, Thailand (H.Y.); Section for Translational Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand (H.Y.); School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia, Indonesia (H.Y.); Thailand Research Fund, Thailand (Grant numbers: RSA6280092; T.K.); and Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand (Grant number: CF_63008; T.K.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This work was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University (approval number: MURA2021/136).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rathi A., Chakrabarti A., Agarwal T., Pushker N., Patil M., Kamble H., Titiyal J.S., Mohan R., Kashyap S., Sharma S., et al. Pythium Keratitis Leading to Fatal Cavernous Sinus Thrombophlebitis. Cornea. 2018;37:519–522. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chitasombat M.N., Petchkum P., Horsirimanont S., Sornmayura P., Chindamporn A., Krajaejun T. Vascular Pythiosis of Carotid Artery with Meningitis and Cerebral Septic Emboli: A Case Report and Literature Review. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2018;21:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Souto E., Maia L., Olinda R., Galiza G., Kommers G., Miranda-Neto E., Dantas A., Riet-Correa F. Pythiosis in the Nasal Cavity of Horses. J. Comp. Pathol. 2016;155:126–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santurio J., Argenta J., Schwendler S., Cavalheiro A., Pereira D., Zanette R., Alves S., Dutra V., Silva M., Arruda L., et al. Granulomatous Rhinitis Associated with Pythium Insidiosum Infection in Sheep. Vet. Rec. 2008;163:276. doi: 10.1136/vr.163.9.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alfaro A., Mendoza L. Four Cases of Equine Bone Lesions Caused by Pythium Insidiosum. Equine Vet. J. 1990;22:295–297. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1990.tb04273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berryessa N., Marks S., Pesavento P., Krasnansky T., Yoshimoto S., Johnson E., Grooters A.M. Gastrointestinal Pythiosis in 10 Dogs from California. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2008;22:1065–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2008.0123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan J.H., Kerkar S.P., Siegenthaler M.P., Hughes M., Pandalai P.K. A Complicated Case of Vascular Pythium Insidiosum Infection Treated with Limb-Sparing Surgery. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2014;5:677–680. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hung C., Leddin D. Keratitis Caused by Pythium Insidiosum in an Immunosuppressed Patient with Crohn’s Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;12:A21–A22. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murdoch D., Parr D. Pythium Insidiosum Keratitis. Aust. N. Z. J. Ophthalmol. 1997;25:177–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1997.tb01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Permpalung N., Worasilchai N., Chindamporn A. Human Pythiosis: Emergence of Fungal-like Organism. Mycopathologia. 2020;185:801–812. doi: 10.1007/s11046-019-00412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marques S.A., Bagagli E., Bosco S.M.G., Camargo R.M.P., Marques M.E.A. Pythium Insidiosum: Report of the First Case of Human Infection in Brazil. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2006;81:483–485. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962006000500012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franco D.M., Aronson J.F., Hawkins H.K., Gallagher J.J., Mendoza L., McGinnis M.R., Williams-Bouyer N. Systemic Pythium Insidiosum in a Pediatric Burn Patient. Burns. 2010;36:e68–e71. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chitasombat M.N., Larbcharoensub N., Chindamporn A., Krajaejun T. Clinicopathological Features and Outcomes of Pythiosis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018;71:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Purcell K., Johnson P., Kreeger J., Wilson D. Jejunal Obstruction Caused by a Pythium Insidiosum Granuloma in a Mare. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1994;205:337–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kepler D., Cole R., Lee-Fowler T., Koehler J., Shrader S., Newton J. Pulmonary Pythiosis in a Canine Patient. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound. 2019;60:E20–E23. doi: 10.1111/vru.12516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossato C., Fiss L., Sperotto V., Cardona R., Silva R. Pythiosis with Atypical Location in the Soft Palate in a Horse in Southern Brazil. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2018;70:641–643. doi: 10.1590/1678-4162-9568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salas Y., Márquez A., Canelón J., Perazzo Y., Colmenárez V., López J. Equine Pythiosis: Report in Crossed Bred (Criole Venezuelan) Horses. Mycopathologia. 2012;174:511–517. doi: 10.1007/s11046-012-9562-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Souto E.P.F., Maia L.Â., Assis D.M., de Miranda Neto E.G., Kommers G.D., de Galiza G.J.N., Riet-Correa F., Dantas A.F.M. Mastitis by Pythium Insidiosum in Mares. Acta Sci. Vet. 2019;47:387. doi: 10.22456/1679-9216.91877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cardona-Álvarez J., Vargas-Vilória M., Patarroyo-Salcedo J. Cutaneous Pythiosis in Horses Treated with Triamcinolone Acetonide. Part 1. Clinical Characterization. Rev. MVZ Córdoba. 2016;21:5511–5524. doi: 10.21897/rmvz.825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rivierre C., Laprie C., Guiard-Marigny O., Bergeaud P., Berthelemy M., Guillot J. Pythiosis in Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005;11:479–481. doi: 10.3201/eid1103.040697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krockenberger M., Swinney G., Martin P., Rothwell T., Malik R. Sequential Opportunistic Infections in Two German Shepherd Dogs. Aust. Vet. J. 2011;89:9–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2010.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sohn Y.S., Kim D.Y., Kweon O.K., Seo I. bok Enteric Pythiosis in a Jindo Dog. Korean J. Vet. Res. 1996;36:447–451. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chindamporn A., Kammarnjessadakul P., Kesdangsakonwut S., Banlunara W. A Case of Canine Cutaneous Pythiosis in Thailand. Access Microbiol. 2020;2:acmi000109. doi: 10.1099/acmi.0.000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fortin J.S., Calcutt M.J., Kim D.Y. Sublingual Pythiosis in a Cat. Acta Vet. Scand. 2017;59:63. doi: 10.1186/s13028-017-0330-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dowst M., Pavuk A., Vilela R., Vilela C., Mendoza L. An Unusual Case of Cutaneous Feline Pythiosis. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2019;26:57–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Souto E., Maia L., Virgínio J., Carneiro R., Kommers G., Riet-Correa F., Galiza G., Dantas A. Pythiosis in Cats in Northeastern Brazil. J. Mycol. Med. 2020;30:101005. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2020.101005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duncan D., Hodgin C., Bauer R., Brignac M. Cutaneous Pythiosis in Four Cats. [(accessed on 10 September 2021)];Proceedings of the 43rd Meeting of the American College of Veterinary Pathologists. 1992 Volume 29:429. Available online: https://www.acvp.org/page/Past_Annual_Meetings. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heck L.C., Bianchi M.V., Pereira P.R., Lorenzett M.P., de Lorenzo C., Pavarini S.P., Driemeier D., Sonne L. Gastric Pythiosis in a Bactrian Camel (Bactrianus Camelus) J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2018;49:784–787. doi: 10.1638/2017-0195.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wellehan J.F., Farina L.L., Keoughan C.G., Lafortune M., Grooters A.M., Mendoza L., Brown M., Terrell S.P., Jacobson E.R., Heard D.J. Pythiosis in a Dromedary Camel (Camelus Dromedarius) J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2004;35:564–568. doi: 10.1638/03-098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pesavento P., Barr B., Riggs S., Eigenheer A., Pamma R., Walker R. Cutaneous Pythiosis in a Nestling White-Faced Ibis. Vet. Pathol. 2008;45:538–541. doi: 10.1354/vp.45-4-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Souto E., Pessoa C., Pessoa A., Trost M., Kommers G., Correa F., Dantas A. Esophageal Pythiosis in an Ostrich (Struthio Camelus) Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2019;71:1081–1084. doi: 10.1590/1678-4162-10666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vilela R., Montalva C., Luz C., Humber R.A., Mendoza L. Pythium Insidiosum Isolated from Infected Mosquito Larvae in Central Brazil. Acta Trop. 2018;185:344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Camus A.C., Grooters A.M., Aquilar R.F. Granulomatous Pneumonia Caused by Pythium Insidiosum in a Central American Jaguar, Panthera Onca. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2004;16:567–571. doi: 10.1177/104063870401600612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otta S.K., Praveena P.E., Raj R.A., Saravanan P., Priya M.S., Amarnath C.B., Bhuvaneswari T., Panigrahi A., Ravichandran P. Pythium Insidiosum as a New Opportunistic Fungal Pathogen for Pacific White Shrimp, Litopenaeus Vannamei. Indian J. Geo Mar. Sci. 2018;47:1036–1041. [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Cock A., Mendoza L., Padhye A., Ajello L., Kaufman L. Pythium Insidiosum Sp. Nov., the Etiologic Agent of Pythiosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1987;25:344. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.2.344-349.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaastra W., Lipman L.J., De Cock A.W., Exel T.K., Pegge R.B., Scheurwater J., Vilela R., Mendoza L. Pythium Insidiosum: An Overview. Vet. Microbiol. 2010;146:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Supabandhu J., Fisher M.C., Mendoza L., Vanittanakom N. Isolation and Identification of the Human Pathogen Pythium Insidiosum from Environmental Samples Collected in Thai Agricultural Areas. Med. Mycol. 2008;46:41–52. doi: 10.1080/13693780701513840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vanittanakom N., Szekely J., Khanthawong S., Sawutdeechaikul P., Vanittanakom P., Fisher M.C. Molecular Detection of Pythium Insidiosum from Soil in Thai Agricultural Areas. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2014;304:321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Presser J.W., Goss E.M. Environmental Sampling Reveals That Pythium Insidiosum Is Ubiquitous and Genetically Diverse in North Central Florida. Med. Mycol. 2015;53:674–683. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myv054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Htun Z.M., Laikul A., Pathomsakulwong W., Yurayart C., Lohnoo T., Yingyong W., Kumsang Y., Payattikul P., Sae-Chew P., Rujirawat T., et al. Identification and Biotyping of Pythium Insidiosum Isolated from Urban and Rural Areas of Thailand by Multiplex PCR, DNA Barcode, and Proteomic Analyses. J. Fungi. 2021;7:242. doi: 10.3390/jof7040242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendoza L., Hernandez F., Ajello L. Life Cycle of the Human and Animal Oomycete Pathogen Pythium Insidiosum. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993;31:2967–2973. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2967-2973.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Da Silva Fonseca A.O., de Avila Botton S., Nogueira C.E.W., Corrêa B.F., de Souza Silveira J., de Azevedo M.I., Maroneze B.P., Santurio J.M., Pereira D.I.B. In Vitro Reproduction of the Life Cycle of Pythium Insidiosum from Kunkers’ Equine and Their Role in the Epidemiology of Pythiosis. Mycopathologia. 2014;177:123–127. doi: 10.1007/s11046-013-9720-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krajaejun T., Sathapatayavongs B., Pracharktam R., Nitiyanant P., Leelachaikul P., Wanachiwanawin W., Chaiprasert A., Assanasen P., Saipetch M., Mootsikapun P., et al. Clinical and Epidemiological Analyses of Human Pythiosis in Thailand. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006;43:569–576. doi: 10.1086/506353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maia L.A., Olinda R.G., Araújo T.F., Firmino P.R., Nakazato L., Neto E.G.M., Riet-Correa F., Dantas A.F. Cutaneous Pythiosis in a Donkey (Equus Asinus) in Brazil. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2016;28:436–439. doi: 10.1177/1040638716651467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thieman K.M., Kirkby K.A., Flynn-Lurie A., Grooters A.M., Bacon N.J. Diagnosis and Treatment of Truncal Cutaneous Pythiosis in a Dog. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2011;239:1232–1235. doi: 10.2460/javma.239.9.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dos Santos C.E., Ubiali D.G., Pescador C.A., Zanette R.A., Santurio J.M., Marques L.C. Epidemiological Survey of Equine Pythiosis in the Brazilian Pantanal and Nearby Areas: Results of 76 Cases. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2014;34:270–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2013.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernheim D., Dupont D., Aptel F., Dard C., Chiquet C., Normand A.C., Piarroux R., Cornet M., Maubon D. Pythiosis: Case Report Leading to New Features in Clinical and Diagnostic Management of This Fungal-like Infection. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;86:40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soares L.M.C., Schenkel D.M., Rosa J.M.A., Azevedo L.S., Tineli T.R., Dutra V., Colodel E.M., Pescador C.A. Feline Subcutaneous Pythiosis. Cienc. Rural. 2019;49:e20180448. doi: 10.1590/0103-8478cr20180448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elkhenany H., Nabil S., Abu-Ahmed H., Mahmoud H., Korritum A., Khalifa H. Treeatment and Outcome of Horses with Cutaneous Pythiosis, and Meta-Analysis of Similar Reports. Slov. Vet. Res. 2019;56:281–291. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laohapensang K., Rutherford R.B., Supabandhu J., Vanittanakom N. Vascular Pythiosis in a Thalassemic Patient. Vascular. 2009;17:234–238. doi: 10.2310/6670.2008.00073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prasertwitayakij N., Louthrenoo W., Kasitanon N., Thamprasert K., Vanittanakom N. Human Pythiosis, a Rare Cause of Arteritis: Case Report and Literature Review. Semin. Arthritis. Rheum. 2003;33:204–214. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dhirachaikulpanich D., Soraprajum K., Boonsopon S., Pinitpuwadol W., Lourthai P., Punyayingyong N., Tesavibul N., Choopong P. Epidemiology of Keratitis/Scleritis-Related Endophthalmitis in a University Hospital in Thailand. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:11217. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90815-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maeno S., Oie Y., Sunada A., Tanibuchi H., Hagiwara S., Makimura K., Nishida K. Successful Medical Management of Pythium Insidiosum Keratitis Using a Combination of Minocycline, Linezolid, and Chloramphenicol. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2019;15:100498. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2019.100498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He H., Liu H., Chen X., Wu J., He M., Zhong X. Diagnosis and Treatment of Pythium Insidiosum Corneal Ulcer in a Chinese Child: A Case Report and Literature Review. Am. J. Case Rep. 2016;17:982–988. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.901158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Manço M.H., Ferreira S.K., Perossi I.F.S., Klein M., Pelógia M.E.S., Carra G.J.U., de Souza C.D.D., Costa M.T., Bosco S., Moraes P.C., et al. Metastatic Calcification and Granulomatous Grastroenteritis Associated to Pythium Insidiosum in a Dog. Braz. J. Vet. Pathol. 2021;14:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hummel J., Grooters A., Davidson G., Jennings S., Nicklas J., Birkenheuer A. Successful Management of Gastrointestinal Pythiosis in a Dog Using Itraconazole, Terbinafine, and Mefenoxam. Med. Mycol. 2011;49:539–542. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.543705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parambeth J.C., Lawhon S.D., Mansell J., Wu J., Clark S.D., Sutton D., Gibas C., Wiederhold N.P., Myers A.N., Johnson M.C., et al. Gastrointestinal Pythiosis with Concurrent Presumptive Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis in a Boxer Dog. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2019;48:83–88. doi: 10.1111/vcp.12720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reis J.L., Jr., de Carvalho E.C.Q., Nogueira R.H.G., Lemos L.S., Mendoza L. Disseminated Pythiosis in Three Horses. Vet. Microbiol. 2003;96:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jaeger G.H., Rotstein D.S., Law J.M. Prostatic Pythiosis in a Dog. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2002;16:598–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2002.tb02394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heath J.A., Kiehn T.E., Brown A.E., LaQuaglia M.P., Steinherz L.J., Bearman G., Wong M., Steinherz P.G. Pythium Insidiosum Pleuropericarditis Complicating Pneumonia in a Child with Leukemia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002;35:e60–e64. doi: 10.1086/342303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chitasombat M.N., Jongkhajornpong P., Lekhanont K., Krajaejun T. Recent Update in Diagnosis and Treatment of Human Pythiosis. PeerJ. 2020;8:e8555. doi: 10.7717/peerj.8555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grooters A.M., Whittington A., Lopez M.K., Boroughs M.N., Roy A.F. Evaluation of Microbial Culture Techniques for the Isolation of Pythium Insidiosum from Equine Tissues. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2002;14:288–294. doi: 10.1177/104063870201400403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krajaejun T., Chongtrakool P., Angkananukul K., Brandhorst T.T. Effect of Temperature on Growth of the Pathogenic Oomycete Pythium Insidiosum. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health. 2010;41:1462–1466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tondolo J.S.M., Loreto É.S., Denardi L.B., Mario D.A.N., Alves S.H., Santurio J.M. A Simple, Rapid and Inexpensive Screening Method for the Identification of Pythium Insidiosum. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2013;93:52–54. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martins T., Kommers G., Trost M., Inkelmann M., Fighera R., Schild A. A Comparative Study of the Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry of Pythiosis in Horses, Dogs and Cattle. J. Comp. Pathol. 2012;146:122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mittal R., Jena S.K., Desai A., Agarwal S. Pythium Insidiosum Keratitis: Histopathology and Rapid Novel Diagnostic Staining Technique. Cornea. 2017;36:1124–1132. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Inkomlue R., Larbcharoensub N., Karnsombut P., Lerksuthirat T., Aroonroch R., Lohnoo T., Yingyong W., Santanirand P., Sansopha L., Krajaejun T. Development of an Anti-Elicitin Antibody-Based Immunohistochemical Assay for Diagnosis of Pythiosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016;54:43–48. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02113-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Keeratijarut A., Karnsombut P., Aroonroch R., Srimuang S., Sangruchi T., Sansopha L., Mootsikapun P., Larbcharoensub N., Krajaejun T. Evaluation of an In-House Immunoperoxidase Staining Assay for Histodiagnosis of Human Pythiosis. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health. 2009;40:1298–1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jaturapaktrarak C., Payattikul P., Lohnoo T., Kumsang Y., Laikul A., Pathomsakulwong W., Yurayart C., Tonpitak W., Krajaejun T. Protein A/G-Based Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay for Detection of Anti-Pythium Insidiosum Antibodies in Human and Animal Subjects. BMC Res. Notes. 2020;13:135. doi: 10.1186/s13104-020-04981-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Intaramat A., Sornprachum T., Chantrathonkul B., Chaisuriya P., Lohnoo T., Yingyong W., Jongruja N., Kumsang Y., Sandee A., Chaiprasert A., et al. Protein A/G-Based Immunochromatographic Test for Serodiagnosis of Pythiosis in Human and Animal Subjects from Asia and Americas. Sabouraudia. 2016;54:641–647. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myw018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Worasilchai N., Leelahavanichkul A., Permpalung N., Kuityo C., Phaisanchatchawan T., Palaga T., Reantragoon R., Chindamporn A. Antigen Host Response Differences between the Animal-Type Strain and Human-Clinical Pythium Insidiosum Isolates Used for Serological Diagnosis in Thailand. Med. Mycol. 2019;57:519–522. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chareonsirisuthigul T., Khositnithikul R., Intaramat A., Inkomlue R., Sriwanichrak K., Piromsontikorn S., Kitiwanwanich S., Lowhnoo T., Yingyong W., Chaiprasert A., et al. Performance Comparison of Immunodiffusion, Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay, Immunochromatography and Hemagglutination for Serodiagnosis of Human Pythiosis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013;76:42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jindayok T., Piromsontikorn S., Srimuang S., Khupulsup K., Krajaejun T. Hemagglutination Test for Rapid Serodiagnosis of Human Pythiosis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:1047–1051. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00113-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Krajaejun T., Imkhieo S., Intaramat A., Ratanabanangkoon K. Development of an Immunochromatographic Test for Rapid Serodiagnosis of Human Pythiosis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:506–509. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00276-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Krajaejun T., Kunakorn M., Niemhom S., Chongtrakool P., Pracharktam R. Development and Evaluation of an In-House Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay for Early Diagnosis and Monitoring of Human Pythiosis. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2002;9:378–382. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.2.378-382.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kulandai L., Lakshmipathy D., Sargunam J. Novel Duplex Polymerase Chain Reaction for the Rapid Detection of Pythium Insidiosum Directly from Corneal Specimens of Patients with Ocular Pythiosis. Cornea. 2020;39:775–778. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]