Abstract

Recent advancements in nanotechnology have improved our understanding of cancer treatment and allowed the opportunity to develop novel delivery systems for cancer therapy. The biological complexities of cancer and tumour micro-environments have been shown to be highly challenging when treated with a single therapeutic approach. Current co-delivery systems which involve delivering small molecule drugs and short-interfering RNA (siRNA) have demonstrated the potential of effective suppression of tumour growth. It is worth noting that a considerable number of studies have demonstrated the synergistic effect of co-delivery systems combining siRNA and small molecule drugs, with promising results when compared to single-drug approaches. This review focuses on the recent advances in co-delivery of siRNA and small molecule drugs. The co-delivery systems are categorized based on the material classes of drug carriers. We discuss the critical properties of materials that enable co-delivery of two distinct anti-tumour agents with different properties. Key examples of co-delivery of drug/siRNA from the recent literature are highlighted and discussed. We summarize the current and emerging issues in this rapidly changing field of research in biomaterials for cancer treatments.

Keywords: cancer treatment, drug-siRNA co-delivery systems, multifunctional nanocarrier, siRNA delivery

1. Introduction

Cancer is a large group of dreaded diseases in which abnormal cells proliferate at an uncontrolled rate. Metastasis is the invasion of malignant tumour cells to adjacent parts or other organs [1]. Globally, cancer is the major leading cause of premature deaths. In 2020 alone, 19.3 million new cancer cases were reported worldwide, with over 10 million deaths. A significant rise in cancer incidence of 47% is expected in 2040 [2]. Critically, provision of cancer care is one-half of a two-pronged global effort to reduce the overall burden of cancer [1,2].

Current cancer therapies include radiation, surgery, chemotherapy, targeted therapy or personalized medicine, as well as immunotherapy. Cancer is caused by mutations of genes that lead to activation of proto-oncogenes or inactivation of tumour suppressor genes [3]. Biomarker testing is a profiling of the tumour genetics, which enables treatments which target tumours with genetic changes in particular genes [4].

Chemotherapy drugs are commonly delivered directly through the oral, intravenous, or topical routes as well as through direct injections to the cancer site [4]. However, current chemotherapy targets only a limited subset of tumour-related molecules and pathways such as kinases, and DNA damage. Targeted therapy involves deploying small molecule drugs and monoclonal antibodies which targets the molecules which regulate tumour growth.

Recent advances in drug delivery systems have improved the efficacy of existing chemotherapy drugs by increasing their bioavailability to tumour sites. However, the fact remains that these drugs only target a few tumour-related factors but exclude tumour transcription factors. The majority of the signalling molecules in cancer is regulated by transcription factors (e.g., kRAS, p53, cJUN). Although drug molecules are unable to target these transcription factors, small- or short-interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNA) is able to interfere with their function.

siRNA has proven to be a useful tool to inhibit specific targets within tumour cells [5,6,7,8]. However, there are two significant issues with the use of siRNA alone for cancer treatment. Firstly, due to the specificity of siRNA, there is a high chance of tumour cells developing acquired resistance through further mutation. Secondly, as tumours are heterogenous in nature, even with the successful delivery of siRNA to a tumour, this alone does not guarantee the reduction of the tumour [8,9,10].

A viable solution for cancer treatment, therefore, consists of a combination of chemotherapy drugs and siRNA. A chemotherapy drug targets the bulk of a tumour (based on tumour-related phenotypes such as cell proliferation, DNA repair, etc.), whereas siRNA targets a specific mutation in a tumour. This justifies further development into co-delivery systems integrating small molecule chemotherapy drugs (molecular weight < 500 according to the National Cancer Institute) and siRNA.

Currently, various co-delivery systems are in various developmental stages. They consist of various classes of materials, including liposomes, dendrimers, as well as nanoparticles of polymeric, inorganic and metallic origins [11,12]. This review paper will summarize the desirable properties of these co-delivery systems, followed by a detailed report of different classes of co-delivery systems which host a combination of small molecule drugs and siRNA. A discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of each class of co-delivery system is presented as well. We also discuss current challenges faced in the systemic co-delivery of small molecule drugs-siRNA, and the strategies employed to overcome them. Finally, concluding remarks are provided to comment on the state of the art in this highly evolving and multidisciplinary field.

2. Desirable Properties of Co-Delivery Systems

A co-delivery system is a system which allows the concurrent delivery of more than one therapeutic substance. The therapeutic substances include chemotherapy drugs, deoxyribonucleic acids (DNAs), ribonucleic acids (RNAs), antibodies, etc.

Drug delivery systems enable the manipulation of drug properties, for instance, pharmaco-kinetics, pharmaco-dynamics, therapeutic index, biodistribution and cellular uptake of therapeutic agents. Various chemotherapeutics with poor water solubility, including Paclitaxel, require suitable delivery vehicles with high loading efficiency in order to successfully reach tumour cells [13].

In order to construct an effective and successful drug delivery system, several fundamental prerequisites are required: (i) the vehicles should be biocompatible, biodegradable, non-immunogenic, (ii) high loading capacity of and preservation of guest molecules, (iii) zero premature release before reaching and optimal uptake at the target site, (iv) effective endosomal escape, (v) controllable release rate, and (vi) active targeting of cells and tissues [5,14].

However, the requirements of a co-delivery system extend beyond the criteria listed above, as two agents with different physicochemical properties are incorporated in one drug carrier.

The vehicle for gene-delivery systems has additional criteria: (i) it must be capable of evading reticuloendothelial uptake [6,8], (ii) it must not engage in interaction with vascular endothelial cells and blood components, i.e., possess good stability or persistence in blood [5,6], and (iii) the system must be compact and stable enough to penetrate through the cell membrane and not degrade before reaching the nucleus [6,8,15]. The release mechanism from the vehicle is contingent on the types of oligonucleotides being transported. For instance, antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotides (ODNs) and siRNA should be targeted to be released in the cytosol to inhibit mRNA expression, while delivery of plasmid DNA should reach the nucleus as ectopic DNA [16]. In this review, the focus will be on the co-delivery of small molecule drugs and siRNA.

As cancer belongs to the category of genetic diseases, siRNA-employed cancer treatment was reported to have significant results; however, the inherent characteristics of siRNA have elevated the difficulty of this type of therapy. Nucleic acid has an anionic hydrophilic structure with ~38 to 50 phosphate groups, which renders them impermeable through biological membranes [5,6,8]. Systemic delivered, unmodified naked siRNA is vulnerable to degradation through enzymatic digestion [17]. Besides that, siRNA has a molecular weight of ~13 kDa which is small enough for it to be easily removed through the kidney. However, its molecular weight is comparatively larger than small molecule drugs; this difference eventually affects the co-delivery system in terms of biodistribution and pharmacokinetics [7,8].

3. Classes of Co-Delivery Systems

Various combinations of small molecule drug-siRNA pairs have been reported in the literature to combat the highly heterogeneous and extremely complicated microtumour environment. There are strategies to formulate small molecule drug-siRNA combinations to improve the therapeutic efficacy of anticancer drugs: (i) to synergize the efficacy of anticancer drugs through synthetic lethality, (ii) to overcome multidrug resistance (MDR) silencing drug efflux pump-related gene, (iii) to enhance efficiency of cancer treatment by promoting apoptosis in cancer cells, and (iv) to promote anti-tumour therapy by targeting metastasis and angiogenesis [7].

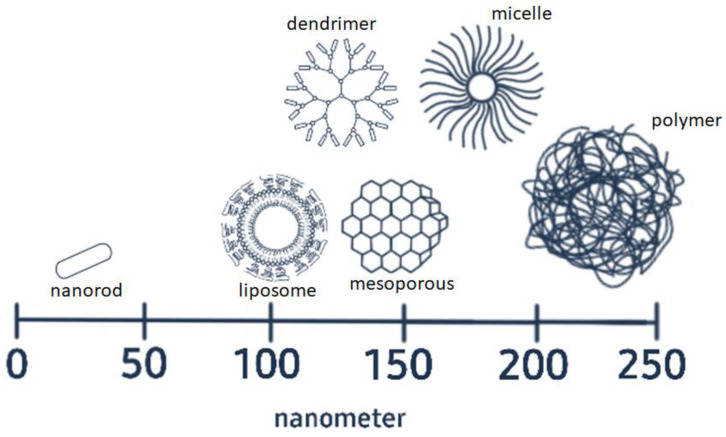

The emerging technology in nanomaterials development has introduced various options of drug carriers to be employed in co-delivery systems. Each class of materials has their own unique properties, conferring advantages as well as disadvantages for co-delivery. Figure 1 shows the structure and size range of various classes of materials commonly used in co-delivery applications. Each vehicle possesses distinctive structural features and morphology, which promote various advantages for co-delivery applications. Hollow or porous structures have better capability to encapsulate drugs, while surface modification of structures enables the surface attachment of drugs or siRNA. However, a common characteristic of all these structures is high surface-area-to-volume ratio.

Figure 1.

The structures and size range of vehicles used to co-deliver drug molecules and siRNA (not drawn to scale).

The diversity and heterogeneity of cancer cells has made a tailored combination of chemotherapy drug-siRNA a highly promising treatment option. However, an appropriate vehicle is vital to a successful co-delivery system. Recent material choices for small molecule drug-siRNA co-delivery are reviewed in the following sections. A summary of the advantages and disadvantages of each co-delivery system is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of advantages and disadvantages of various systems used for co-delivery of small molecule drugs and siRNA.

| Delivery System | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles |

|

|

| Polymeric Materials |

|

|

| Liposomes |

|

|

| Dendrimers |

|

|

| Gold nanoparticles |

|

|

3.1. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles

3.1.1. General Properties

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNPs) are solid materials, in which hundreds of empty nanoscale channels are arranged in a two-dimensional network where the mesoporous structure is described as honeycomb-like [18,19]. By definition, the pores of mesoporous materials have a narrow pore size distribution ranging between 2–50 nm [20]. For instance, the MCM-41 mesoporous silica has a diameter of approximately 20 nm [21]. MSNPs have a manipulatable mesoporous structure, large pore volume, high specific surface area, and dual-functionality on the exterior and interior surfaces [19,22,23,24,25,26]. Their mesoporous inner structure provides for high drug loading capacity and enable control over drug release behaviour [19,25,26,27]. The unique properties of MSNPs enable the encapsulation of a wide range of therapeutic agents for targeted delivery, while preventing their premature release and degradation.

Silica is an abundant natural mineral having good biological compatibility. It is declared as “Generally Recognized As Safe” (GRAS) by the United States Food and Drug Authority (FDA). Silica materials are conventionally employed in industries such as cosmetics and food additives owing to their good biocompatibility [28]. Surface modification of the silica structure assists bioavailability and cellular uptake of the platform, avoids unwanted biological interactions, and bypasses monitoring by the immune system [22,27]. The theory of immune surveillance describes a patrol system to recognize and destroy invading pathogens as well as potential cancerous host cells [22,29,30].

Generally, the high surface-area-to-volume ratio and well-ordered mesoporous structure of MSNPs has been shown to facilitate improved drug loading capacity, biocompatibility and biodegradability [31,32,33]. The easily-functionalized surface properties of MSNPs allow their surfaces to be functionalized with siRNA to impart excellent colloidal stability [31,32]. These properties make MSNPs a promising vehicle for small molecule drug and siRNA co-delivery.

3.1.2. Applications in Cancer Treatment

MSNPs offer the possibility of carrying drugs to the target site without degradation. However, it has been found that the drug released from the mesopores of unmodified MSNPs are often distributed off-target, an undesirable outcome for targeted drug delivery systems. Hence, the potential of MSNPs as co-delivery platforms have been expanded by the introduction of various surface modifications. The functionality of MSNPS has been enhanced from static drug vehicles into multifunctional delivery systems [18,19,25,26]. The ease of functionalizing the surfaces of MSNPs has resulted in MSNP-based systems which demonstrate properties such as sensitivity to pH, heat and enzymes, capability to undergo redox reactions, and responsiveness to magnetic fields. For instance, Yu et al. reported integrating superparamagnetic iron oxide nanocrystals in the core of MSNPs for magnetic hyperthermia cancer therapy applications [34].

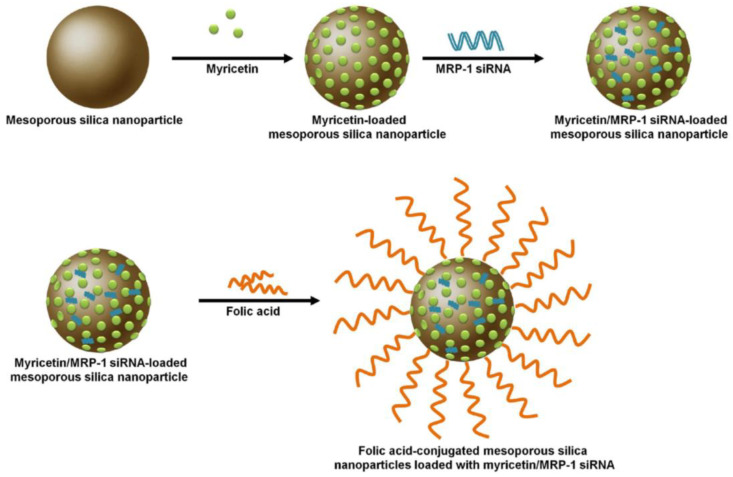

Song et al. [31] developed an MSNP vehicle loaded with myricetin (Myr) and MRP1-siRNA (Figure 2). The MSNP which was conjugated with folic acid (FA) showed increased specificity of Myr towards non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) compared with a non-targeted siRNA control. Sustained release of therapeutics was observed in the FA-conjugated vehicle compared with free Myr and the non-FA conjugated co-delivery system. Furthermore, the FA-conjugated co-delivery system caused increased apoptosis of lung cancer cells.

Figure 2.

The preparation of folic acid-conjugated mesoporous silica nanoparticles loaded with myricetin and MRP-1 siRNA Note: MRP1 is equivalent to ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 1 (ABCC1). The MRP subfamily of genes is involved in multi-drug resistance. Reprinted from [31].

Wang and co-workers [10] prepared an MSNP co-delivery platform with doxorubicin and MDR1-siRNA and conducted in vivo studies on the impacts of the polyethylenimine (PEI)-coated MSNPs on oral cancer cells. They observed decreases in tumour size by 58.67 ± 2.37% when treated with the PEI-coated MSNPs loaded with doxorubicin alone and greater tumour reduction of 81.64 ± 3.17% when treated with the co-delivery system of drug and siRNA when compared to the control specimen. Their result suggested the effective inhibition of tumour growth in vivo when a co-delivery approach was applied.

Zhao et al. [32] found that an MSNP co-delivery system was able to improve tumour targeting efficiency of breast cancers. Their MSNP vehicle was modified with a disulfide group and loaded with doxorubicin and siRNA targeting BCL2 protein. It was reported that the doxorubicin content in tumour tissue after the co-delivery treatment was approximately 2.6-times greater than that of the free doxorubicin treatment. This indicated the potential of co-delivery systems in improving the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in breast tumour tissues. EPR describes a preferred accumulation of therapeutic agents in tumour cells [35,36].

However, Park et al. [36] stated that the heterogenous nature of tumours remain a challenge in targeted cancer therapy, even for nanoscale co-delivery platforms. Crucial factors that can enhance the EPR effect of cancer therapies include the application of molecular markers and enzymes that are specific to the tumour microenvironment (TME), as well as physical transformation of the TME.

Zhou et al. [37] reported a greater apoptotic rate (36.88%) when breast cancer cells were treated with an MSNP co-delivery system of doxorubicin and BCL2 siRNA, when compared with approximately 14% of apoptotic cells observed for the group treated with only doxorubicin loaded in the delivery system. The MSNP delivery system was modified with a copolymer of polyethylenimine-polylysine (PEI-PLL). The disulfide bonds on the copolymer were conjugated with a folate-linked poly(ethylene glycol) (FA-PEG). The resulting positively charged vehicle was able to bind with the negatively charged siRNA while encapsulating doxorubicin within the MSNP mesopores. Their results show that the co-delivery of doxorubicin and BCL2 siRNA offered synergistic cell apoptotic impacts on MDA-MB-231cells [37]. Table 2 shows various other examples of using MSNPs for co-delivery of small molecule drug and siRNA for the treatment of different types of cancer.

Table 2.

Summary of co-delivery of small molecule drug and siRNA by mesoporous silica nanoparticles for cancer therapy.

| Delivery System | Small Molecule Drug | siRNA Target |

Type of Cancer | Cell Line | Testing Stage | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesoporous silica nanoparticles modified with polyethylenimine | Doxorubicin | ABCB1 (or MDR1) | Oral squamous carcinoma | KBV |

In vitro

In vivo |

[10] |

| Folic acid (FA)-conjugated mesoporous silica nanoparticles | Myricetin | ABCC1 (or MRP1) | Non-small cell lung cancer | A594 NCI-H1299 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[31] |

| Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNPs) | Doxorubicin | BCL2 | Breast Cancer | MCF-7 HEK 293 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[32] |

| Acid-sensitive calcium phosphate/silica dioxide (CAP/SiO2) composite | Doxorubicin | ABCB1 (or MDR1) | Leukaemia | K562/ADR | In vitro | [33] |

| Mesoporous silica nanoparticles modified with polyethylenimine− polylysine and folate-linked poly(ethylene glycol) | Doxorubicin | BCL2 | Breast Cancer | MDA-MB-231 RAW 264.7 | In vitro | [37] |

Note: ABCB1, ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 1; ABCC1, ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 1; BCL2, BCL2 apoptosis regulator; MDR1, multidrug resistance protein 1; MRP1, multidrug resistance associated protein 1.

3.2. Polymeric Materials

3.2.1. General Properties

Polymers are a large class of natural as well as synthetic materials, with a wide range of properties, which are directly related to their molecular weight, molecular structure and elemental composition. These macromolecules are made up of multiple repeating sub-units (mers). Polymer-based delivery systems are one of the most well-established platforms used to deliver therapeutic agents [38]. Their success is due to their versatility and tuneable characteristics in order to achieve the desired pharmaceutical and biomedical requirements [39].

Among the natural polymers which have been reported for use in drug delivery include derivatives of arginine, chitosan, cyclodextrin, polyglycolic acid (PGA), polylactic acid (PLA), and polysaccharides. These are generally favourable options due to their nontoxicity, biocompatibility and biodegradability [40,41]. PGA, PLA, polycaprolactone and polydioxanone are used as polymeric implant materials due to their biodegradable and bioabsorbable qualities [42].

On the other hand, man-made polymers such as poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (PHEMA) hydrogel, poly(n-isoproply acrylamide, polyethyleimine (PEI), and poly(n-(2-hydropropyl) methacrylamide) are preferred over the natural polymers as drug delivery systems due to their immunogenicity [42].

Amphiphilic block copolymers are a versatile class of self-assembling structures which can be formulated to produce polymeric nanoparticles such as. micelles and polymersomes [43]. Nanopolymeric delivery systems in micellar form alleviate the adverse effects of drugs, in which their hydrophobic core enables effective encapsulation of multiple anticancer agents including hydrophobic drugs [44,45]. The use of micelles was reported to lengthen drug retention time in the blood circulation and selectively accumulated in tumour tissue through the EPR effect [44,46].

Polymers bearing a positive charge or containing cationic functional groups in their structure are termed polycationic polymers. They have been extensively studied as a form of injectable, nonviral delivery agent for nucleic acid and drugs [40,47]. They also have wide application in biomedical areas, for instance as antimicrobial agents due to their affinity for the negatively-charged membrane of microorganisms, hence causing lysis of cell walls [48]. The most well-investigated synthetic linear cationic polymers include PEI, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), and poly-L-lysine (PLL).

As a transfection agent, polycationic polymers are able to compress nucleic acid to form polyplexes for gene therapy. In general, to encapsulate and deliver a higher concentration of siRNA, polycations are engineered with greater charge densities, which are often associated with carrier-induced toxicity [49]. The toxicity of polymeric cation-mediated gene therapy is strongly linked to their chemical structure [50]. For instance, PEI with a low molecular weight (11.9 kDa) and a moderately branched structure showed about 100 times higher delivery efficiency, coupled with low toxicity, in comparison to a higher molecular weight PEI vector [51]. After delivery of the genetic payload, PEI is liberated of their cargo and has the potential to negatively interact with cellular components. Hence, an appropriate and suitable design of the polymeric drug carrier is vital. One solution to address delayed polymer toxicity issues is by incorporating PEG [50].

Copolymers of PLL-PEG are another example of thoughtful polymeric nanocarrier design. PLL are biodegradable, linear polypeptides in which the repeating unit is the amino acid lysine. PLL-nucleic acid polyplexes require the addition of chloroquine in order to improve their gene delivery efficiency. However, this results in increased cytotoxicity. With the use of higher molecular weight PLL, there is a trade-off between greater transfection efficiency and the accompanying higher cytotoxicity [52]. It has been shown that grafting of PEG to PLL can reduce cytotoxicity without reduction of transfection efficiency [53].

3.2.2. Applications in Cancer Treatment

An emerging set of polymer-based drug delivery systems are being designed with moieties that are sensitive to changes in pH, temperature, the presence of glutathione, reactive oxygen species, and enzymes [54]. In the absence of disease, the bodily pH level is homeostatically maintained within a range of 7.35–7.45 [55]. Polymeric delivery systems can be designed to control the release of their therapeutic cargo by sensing the slightly acidic-pH levels linked to tumour microenvironments (pH 6.5–6.8) [44,46,56]. This particular property has gained popularity in the design of a controlled and targeted anticancer therapy system.

For instance, Suo et al. [56] applied a reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization to obtain a triblock copolymer nanocarrier to mediate the delivery of doxorubicin and Bcl-2 siRNA to target breast cancer cells (MCF-7). Apart from offering a carrier for the delivery of the hydrophobic drug doxorubicin and siRNA, this synthetic method imparts excellent control of the nanocarrier physical properties, including uniformity in size, molecular weight, structure and reproducibility. The nanopolymeric carriers were able to achieve dual-release of its cargo in a reducing and acidic environment [56]. Their results demonstrated that a higher cellular uptake (51.6%) was noted in the cells treated with folate-modified co-delivery system, compared with the unmodified co-delivery system with only a 9.2% uptake. It was deduced that the targeted co-delivery promoted cellular uptake while anticancer effects were synergistically achieved by co-delivering two types of therapeutic agents.

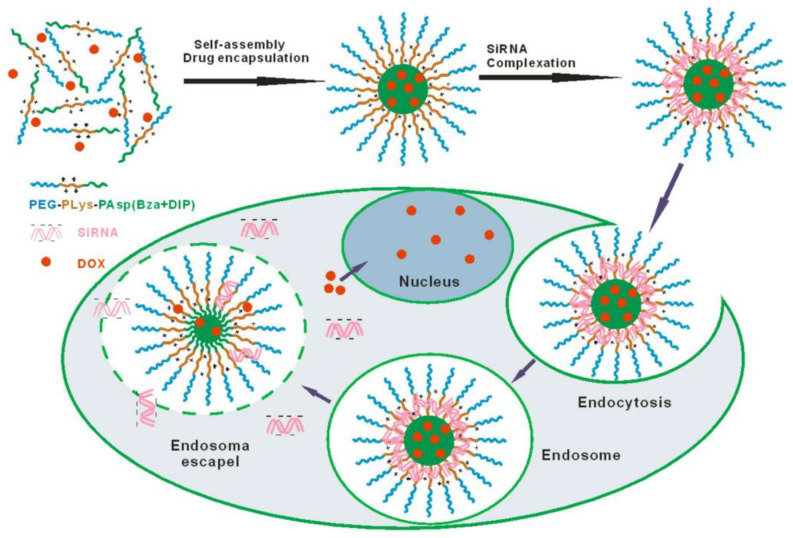

Li et al. [46] also reported a triblock copolymer delivery system in which the micelle size is controlled by changes in pH values; at acidic levels, the therapeutic agents are released in the tumour target. A schematic of the process of the self-assembly and therapeutics release of the co-delivery system designed by Li et al. [46] is shown in Figure 3. The triblock copolymer consisted of a PEG shell, a cationic PLL intermediate layer, and a pH-sensitive core of poly(aspartyl) (Benzylamine-co-(Diisopropylamino)ethylamine.

Figure 3.

Illustration of self-assembly at pH 7.4 and intracellular releasing behaviour of amphiphilic block copolymer of monomethoxylpoly(ethylene glycol), poly(l-lysine), and poly(aspartyl(Benzylamine-co-(Diisopropylamino)ethylamine))mPEG-PLLys-PLAsp(BzA-co-DIP), abbreviated as PELABD micelles, for combinatorial delivery of hydrophobic anticancer drugs (Doxorubicin) and siRNA. Reprinted with permission from [46]. Copyright 2020 Springer Nature.

Additionally, Wu et al. [57] had constructed a type of co-delivering drug carrier with the use of triblock copolymer nanomicelles. The nanomicelles consisted of polyethylene glycol (PEG), polycaprolactone (PCL), and polyethylenimine (PEI). These core-shell nanomicelles were functionalized with folic acid (FA), then loaded with doxorubicin and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) siRNA to induce cell apoptosis in breast cancer cells. In vitro studies were carried out on MCF-7/ADR cell line. The flow cytometry results showed that the co-delivery system had increased the apoptosis level by 69.6% compared to the cells treated with free doxorubicin (85.3% vs. 15.7%) while 44% of increment in apoptosis level when compared to cells treated without the presence of P-gp siRNA (85.3% vs. 41.3%). These results confirm that this co-delivery system is able to deliver small molecule drug synchronously with siRNA. Furthermore, the release of siRNA was effective and able to interfere with the targeted expression [57].

In experiments conducted by Norouzi et al. [58], the best apoptosis induction was observed in dual functional polymeric micelles containing NF-κB (RELA) siRNA and gemcitabine (GemC18). Apoptosis was induced in 78% of MCF-7 cell lines and 95.4% in AsPC-1 cancer cells, illustrating co-delivery as the optimum delivery system for synergistic anticancer effects [58]. In another study, Yan et al. [44] developed a pH-responsive, chitosan-based polymer co-delivery system that delivered doxorubicin and Bcl-2 siRNA to actively target liver hepatocellular carcinoma cells, HepG2.

Table 3 shows a summary of the current combination of small molecule drug and siRNA co-delivery by using polymer-based nanomaterials for different types of cancer treatment.

Table 3.

Summary of co-delivery of small molecule drug and siRNA mediated by polymer-based nanomaterials for cancer therapy.

| Delivery System | Small Molecule Drug | siRNA Target |

Type of Cancer | Cell Line | Testing Stage | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan based pH-responsive polymeric prodrug vector (GA-CS-PEI-HBA-DOX) where GA-CS-PEI-HBA-DOX is prodrug chitosan-polyethylenimine-4-hydrazino-benzoic acid doxorubicin |

Doxorubicin | BCL2 | Liver cancer | HUVEC, HepG2 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[44] |

| Amphiphilic block copolymer of monomethoxylpoly(ethylene glycol), poly(l-lysine), and poly(aspartyl(Benzylamine-co-(Diisopropylamino)ethylamine)) mPEG-PLLys-PLAsp(BzA-co-DIP), abbreviated as PELABD micelles | Doxorubicin | siRNA | Ovarian cancer | SKOV3 | In vitro | [46] |

| Triblock copolymer nanocarrier of PAH-b-PDMAPMA-b-PAH where PAH-b-PDMAPMA-b-PAH is poly(acrylhydrazine)-block-poly(3-dimethylaminopropyl methacrylamide)-block-poly(acrylhydrazine) (PAH-b-PDMAPMA-b-PAH) |

Doxorubicin | BCL2 | Breast cancer | MCF-7 | In vitro | [56] |

| PEG-PCL-PEI triblock copolymer nanomicelle functionalized with folic acid | Doxorubicin | (P-gp) siRNA | Breast cancer | MCF-7/ADR | In vitro | [57] |

| Poly(ε-caprolactone), polyethylenimine and polyethylene glycol (PCL-PEI-PEG) copolymers | 4-(N)-stearoyl gemcitabine | RELA | Pancreatic cancer and breast cancer | AsPC-1, MCF-7 | In vitro | [58] |

| Lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles where cationic ε-polylysine co-polymer nanoparticles (ENPs) are coated with PEGylated lipid bilayer resulted formation of LENPs, with reversed surface charge |

Gemcitabine | HIF1A | Pancreatic cancer | Panc-1 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[59] |

| pH/redox dual-sensitive polymeric materials (cPCPL) where cPCPL is poly(ethylene glycol))x-(chitosan-polymine)y-(lipoic acid)z grafted with cRGDyC-PEG-NHS, cRGDyC is a kind of peptide, PEG is poly(ethylene glycol) and NHS is hydroxysuccinimide. |

Etoposide | EZH2 | Orthotopic non-small-cell lung tumour | luc-A549 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[60] |

| Self-assembled polyjuglanin nanoparticles (PJAD-PEG) where PJAD-PEG is poly(juglanin (Jug) dithiodipropionic acid (DA))-b-poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) |

Doxorubicin | KRAS | Lung cancer | A549, H69 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[61] |

| Cationic polyethylenimine-block-polylactic acid (PEI-PLA) | Paclitaxel | BIRC5 | Lung Adenocarcinoma | 4T1, A549 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[62] |

| Lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) nanoparticles | Paclitaxel | SPDYE7P | Cervical cancer | HeLa |

In vitro

In vivo |

[63] |

| FeCo-polyethylenimine (FeCo-PEI) nanoparticles and polylactic acid-polyethylene glycol (PLA-PEG) | Paclitaxel | FAM group | Breast cancer | MCF-7, BT-474 | In vitro | [64] |

| Hypoxia-sensitive PEG-azobenzene-PEI-DOPE (PAPD) nanoparticles | Doxorubicin | ABCB1 | Ovarian cancer and breast cancer | A2780 ADR, MCF7 ADR | In vitro | [65] |

| Chondroitin sulfate (CS)-coated β-cyclodextrin polyethylenemine polymer | Paclitaxel | MCAM | Breast Cancer | MDA-MB-231, MCF-7 | In vitro | [66] |

| Targeted multifunctional polymeric micelle (TMPM) where TMPM is made up of triblock copolymer poly(ε-caprolactone)-polyethyleneglycol-poly(L-histidine) (PCL-PEGPHIS) |

Paclitaxel | VEGF group | Breast Cancer | HUVECs, MCF-7 | In vitro | [67] |

Note: BCL2, BCL2 apoptosis regulator; HIF1A, hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha; EZH2, enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit; KRAS, KRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase; BIRC5, baculoviral IAP repeat containing 5; SPDYE7P, speedy/RINGO cell cycle regulator family member E7 pseudogene; FAM group, long non-coding family with sequence group; ABCB1, ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 1; MCAM, melanoma cell adhesion molecule; VEGF group, vascular endothelial growth factor group; RELA, RELA proto-oncogene, NF-kB subunit.

3.3. Liposomes

3.3.1. General Properties

Liposomes are soft spherical vesicles that are built mainly from phospholipid layers. They can be formed by one or more phospholipid layers where the layers are also called lamellae [68,69,70]. Phospholipids are under the class of lipids and can be found naturally in egg yolks (cholesterol) [70], vegetable oils, and can also be created synthetically [68]. Variations in phospholipids variations are mostly based on the modifications of head group or bondings formed; these are generally categorized according to the backbone groups–glycerol (glycerophospholipids) and sphingosine (sphingomyelins) [68]. These unique lipids are able to encapsulate a wide range of agents owing to their basic molecular structure which is composed of a hydrophilic head (polar head) and two hydrophilic tails (hydrocarbon chains) [68,70,71]. Liposomes are used as carriers for active agents with differing properties in a wide range of applications, such as cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, food, and farming. The wide-ranging applications of liposomes are attributed to their biocompatibility, encapsulation capability and modifiable formulation for the desired purpose [68,69,70,71,72].

The liposomal delivery system has attracted considerable attention in cancer therapy due to its unique properties to incorporate dissimilar therapeutic agents [59,73,74,75,76]. There are four main types of liposomes: (i) conventional liposomes, which includes cationic, anionic, phospholipids (neutral) and cholesterol, (ii) steric-stable liposomes, (iii) ligand targeting liposomes, and (iv) a combination of the first three types of liposomes [69]. The conventional liposomes are basic shields that are capable of protecting the payload (chemotherapy drugs), and also act as barriers to reduce the toxicity of the compounds in vivo [69]. The encapsulation property of liposomes is expected to mitigate the side effects of chemotherapy drugs. Besides that, its structure which resembles the plasma membrane of cells, plays a vital role in improving the cellular uptake of the compounds [68,72]. Furthermore, it was reported that with the use of liposome delivery systems, retention time in circulation is prolonged, alongside higher drug stability. Other benefits include a better controlled release profile when compared to the effect of using free chemical drugs alone [59,75,76].

However, the therapeutic efficacy of conventional liposomes is restricted by rapid clearance from the bloodstream in the reticuloendothelial system (RES), specifically through the liver and spleen [69]. The formulation can be modified with the use of hydrophilic polymers, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), to obtain steric-stable liposomes, which are able to reduce in vivo opsonization and prolong circulation time in the bloodstream [69]. These liposomes are also reported to preferentially accumulate in the pathological sites and tumour regions by the EPR effect [69,74]

Liposomal delivery systems are not limited to drug delivery; they have been adopted for the incorporation of nucleic acid delivery, as well as in co-delivery of drugs and siRNA hybrid combinations. In using cationic liposomes (CLs), siRNA is protected from degradation by nuclease accumulation in the tumour, one of the key concerns in siRNA delivery. Anionic siRNA can be electrostatically bound to CLs to form a stable complex and improve the cellular uptake of target cells [69,77].

For advanced applications, site-specific or targeted-delivery can be achieved by attachment of ligands onto liposomes [69,70]. The ligand selections are based on the specific over-expression of ligands or specifically expressed ligands at the target cells, organs or tumours. Antibodies, peptides, proteins and carbohydrates are the general types of ligands that are commonly involved in the formulation of ligand-targeted liposomes [69]. Based on this fundamental concept, various types of liposomes have been developed. For instance, imaging agents can be attached onto liposomes to incorporate imaging properties. This conceptual theory has triggered the development of the “smart liposome”, in which the structure changes according to in vivo stimuli such as pH, temperature, enzyme, and magnetic field [77].

In general, all liposomes possess the fundamental properties required of delivery systems, such as, good biocompatibility, biodegradability, and low immunogenicity [59,76]. Liposome-based delivery systems also exhibit efficient loading of both hydrophobic drugs and genes, making them a promising candidate for co-delivery systems [76].

Liposomes were also reported as efficient in reducing cardiotoxicity of chemotherapy drugs such as doxorubicin, which damages heart muscle and function [75]. Besides that, liposomes are capable of penetrating the stratum corneum (outermost layer of skin) at different depths, compared to other nanocarriers [73,78]. The upper stratum corneum layer is the most penetrated layer while dioleoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE)-based liposomes are able to achieve a deeper penetration [78]. Liposomes have been modified to improve their skin penetration ability for dermal drug delivery [79]. Deep penetration in the skin membrane is achievable via the use of transferosomes (liposomes with edge activators) or ethosomes (liposomes comprised of ethanol) [73]. These properties have made liposomes a great candidate for derma-related cancer treatment.

3.3.2. Applications in Cancer Treatment

Jose et al. used a cationic liposome, 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium propane (DOTAP), for the co-delivery of curcumin and STAT3 siRNA to treat skin cancer [73]. The results showed the highest cell growth inhibition (76.3 ± 4.0%) in mouse melanoma cells (B16F10) compared to either curcumin-loaded liposomes or free STAT3 siRNA. This result suggested that this form of co-delivery was effective in curbing melanoma tumour progression.

Oh et al. studied galactosylated liposomes as a co-delivery vehicle to target hepatocellular carcinoma by loading it with doxorubicin and siRNA (Gal-DOX/siRNA-L). The Gal-DOX/siRNA-L system showed better doxorubicin uptake than free doxorubicin [75]. Besides that, the accumulated Gal-DOX/siRNA-L in tumour tissues was 4.8 times higher than that of free doxorubicin.

Lin et al. developed a co-delivery system from GE-11 peptide conjugated liposomes loaded with gemcitabine and siRNA as a formulation to target pancreatic cancer treatment [59]. They found that the co-delivery system displayed a 4-fold reduction in tumour weight compared to the control. When compared to GE-11 peptide conjugated liposome loaded with gemcitabine only (GE-GML), the tumour weight reduction was 2-fold.

Collectively, these results demonstrate the effectiveness of liposomal co-delivery system as an anticancer therapy. Table 4 shows the current combination of small molecule drug and siRNA co-delivery by using liposome nanomaterials for different types of cancer treatments.

Table 4.

Summary of co-delivery of small molecule drug and siRNA by liposomes for cancer therapy.

| Delivery System | Small Molecule Drug | siRNA Target | Types of Cancer | Cell Line | Testing Stage | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GE-11 peptide conjugated liposome | Gemcitabine | HIF1A | Pancreatic cancer | Panc-1 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[59] |

| 1,2-Dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium propane (DOTAP) -based cationic liposomes | Curcumin | STAT3 | Skin cancer | B16F10 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[73] |

| PEGylated liposomes | Docetaxel | BCL2 | Lung cancer | A549, H226 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[74] |

| Galactosylated Liposomes | Doxorubicin | VIM | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Huh7, A549 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[75] |

| Carbamate-linked cationic lipid (Cationic Liposome) | Paclitaxel | BIRC5 | Lung Cancer | NCI-H460 | In vitro | [76] |

Note: STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; BCL2, BCL2 apoptosis regulator; VIM, vimentin; HIF1A, hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha; BIRC5, baculoviral IAP repeat containing 5.

3.4. Dendrimers

3.4.1. General Properties

Dendrimers are a form of symmetrical, hyperbranched, low-molecular-weight polymers on the nanoscale, in which the architecture consists of a core, an inner shell, and an outer shell [80]. Its properties are dependent on functional groups which act as a capping agent on the outer shell [81]. The inner shell consists of several layers of repeating units (known as generations) built by a repetitive series of chemical reactions, while the outermost periphery contains multiple functional groups [82]. Polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers are one of the most well-studied dendrimers for delivery applications. Other types of dendrimers include peptide dendrimers (PPI), poly(l-lysine) dendrimers, and PAMAM-organosilicon dendrimers (PAMAMOS) [81].

Dendrimers are a versatile option as a vehicle for synergistic drug and gene combination therapy. Due to their unique and precise molecular structure, dendrimers can be used to deliver cancer drugs in any of the following ways: (1) cancer drugs can be covalently conjugated to the dendrimer outer shell to construct dendrimer prodrugs through direct coupling or cleavage linking, (2) encapsulating the drug within the central core to form a dendrimer-drug complex, and (3) exploiting the electrostatic interactions between functional groups on the dendrimer capping agent and the drug molecule [80,83].

Electrostatic interactions between the phosphate groups of siRNA and the cationic species on the dendrimer surface are crucial in the formation of complexes for effective delivery of gene therapy [84]. In comparison with conventional linear and branched polymers, dendrimers possess the following properties: (i) well-defined uniform spherical structure and manipulatable size in the nano-range, (ii) availability of numerous generations for different specific purposes [81,83], (iii) lipophilicity and suitable size enabling their diffusion through cell membranes [81], (iv) exceptional flexibility, and (v) low systemic toxicity [85,86]. Dendriplexes (dendrimers bound to nucleic acids) have an enhanced ability to evade endosomal entrapment due to the flexibility of dendrimers [81]. Endosomal escape is the process of siRNA exiting the endosome and entering the cytosol. This process is augmented by the “proton sponge” effect [81,85,87,88]. According to the “proton sponge” hypothesis, an influx of protons into the endosome results in increased buildup of osmotic pressure, causing destabilization of the endosomal membrane, leading to its rupture [88,89,90].

3.4.2. Applications in Cancer Treatment

Table 5 shows the current combination of small molecule drug and siRNA co-delivery by using dendrimer-based nanomaterials for different types of cancer treatment.

Table 5.

Summary of co-delivery of small molecule drug and siRNA by dendrimer-based nanomaterials for cancer therapy.

| Delivery System | Small Molecule Drug | siRNA Target |

Type of Cancer | Cell Line | Testing Stage | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphiphilic dendrimer engineered nanocarrier system (ADENS) modified by tumour microenvironment-sensitive polypeptides (TMSP) (TMSP-ADENS) | Paclitaxel | FAM and VEGF group | Melanoma, prostate cancer |

A375, PC-3, HT-1080 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[13] |

| PTP (plectin-1 targeted peptide, NH2-KTLLPTP-COOH), biomarker for pancreatic cancer, integrated with the PSPG vector to form peptide-conjugated PSPG (PSPGP) where PSPG is branched poly(ethylene glycol) with G2 dendrimers through disulfide linkages |

Paclitaxel | NR4A1 (or TR3) | Pancreatic Cancer | Panc-1 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[83] |

| Hyaluronic acid (HA) modified MDMs where MDMs is the PAMAM-PEG2k-DOPE co-polymer, together with mPEG2k-DOPE, was formulated into mixed dendrimer micelles, and PAMAM is the generation 4 polyamidoamine |

Doxorubicin | ABCB1 (or MDR1) | Ovarian cancer, colorectal carcinoma and breast cancer | A2780 ADR, HCT 116, MDA-MB-231 |

In vitro | [86] |

| PAMAM-OH derivative (PAMSPF) | Murine double minute 2 protein (MDM2) inhibitor RG7388 | TP53 | Breast cancer | P53-wild type MCF-7 cells (MCF-7/WT), MDA-MB-435 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[87] |

| Polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimer | Curcumin | BCL2 | Cervical cancer | HeLa | In vitro | [91] |

| Folate-polyethylene glycol appended dendrimer conjugate with glucuronylglucosyl-β cyclodextrin (Fol-PEG-GUG-β-CDE) (generation 3) | Doxorubicin | PLK1 | Cervical cancer | KB |

In vitro

In vivo |

[92] |

Note: BCL2, BCL2 apoptosis regulator; NR4A1, nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 1; TR3, thioredoxin reductase 3; ABCB1, ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 1; MDR1, multidrug resistance protein 1; FAM, long non-coding family with sequence group; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor group; TP53, tumour protein p53.

Ghaffari et al. [91] studied the apoptotic effects of curcumin (Cur) and BCL2 siRNA co-delivered using polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers on HeLa cells. BCL2 siRNA was grafted to the amine groups on the surface layer of PAMAM while Cur was enveloped within the core to form the co-delivery dendriplex. Cells treated with PAMAM-Cur/siRNA showed an improvement of 58.77% as compared to cells treated with free curcumin alone. Compared with various formulations, the PAMAM-Cur/siRNA co-delivery system had the highest percentage of apoptotic cells among all formulations [91].

Li et al. [13] developed a hollow core/shell amphiphilic dendrimer engineered nanocarrier system (also known as ADENS) to co-deliver the hydrophobic drug paclitaxel and the hydrophilic siRNA. siRNA was loaded in the polar hydrophilic cavity while the paclitaxel was grafted in the polylactic acid (PLA) interlayer. The outer layer was constructed of polyethylene glycol (PEG) to enhance the in vivo circulation time of the co-delivery system and to avoid uptake by the reticuloendothelial system. ADENS was further modified with polypeptides which respond to tumour signals from the surrounding microenvironment. Results revealed that the system inhibited up to 73% of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) at the mRNA level in A375 cell xenograft mice models when compared to controls; thus, demonstrating the synergistic effects of the co-delivery system.

3.5. Gold Nanoparticles

3.5.1. General Properties

Nanoparticles of noble metal elements such as gold, silver and palladium have widespread use in biomedical applications [93]. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) in particular, have been extensively studied due to their versatile properties. Gold is one of the least reactive chemical elements and this has contributed to the properties of biocompatibility and biodegradability [94,95,96,97,98]. AuNPs possess tuneable optical properties, such as light scattering, localized surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and photothermal effects, leading to the incorporation of AuNPs in numerous medical diagnostics including ultrasensitive bioimaging and photothermal therapy [95]. The antimicrobial properties of AuNPs combined with their non-immunogenic and biocompatible properties have led to potential applications in cancer diagnosis and therapy as well as treatment for HIV infection [93]. Nanoparticles have at least one dimension measuring <100 nm and are defined by their high specific surface area. Gold has been synthesized in a variety of morphologies including nanorods, nanospheres, nanocages, nanoshells nanostars, nanorattles, nanopopcorns and nanoaggregates [95,96,99].

3.5.2. Applications in Cancer Treatment

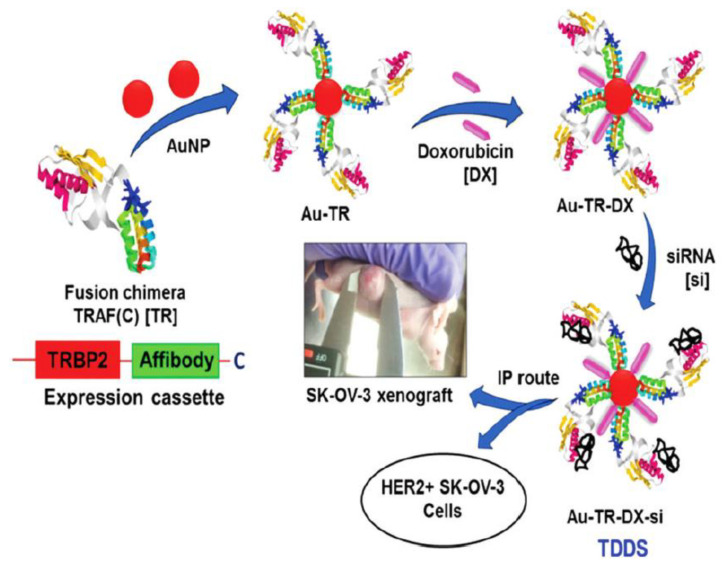

The surface of AuNPs can be modified with active targeting ligands or moieties for tumour-specific targeting [95,96,98]. Through this strategy, passive accumulation and preferential retention of AuNPs at the tumour sites were observed, due to the EPR effect [94,98]. Recently, the distinctive properties of AuNPs have been explored in drug-gene co-delivery systems in cancer treatment. Kotcherlakota and co-workers reported when human ovarian (SK-OV-3) cells were treated with an engineered bi-functional recombinant fusion protein TRAF(C) (TR) gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), loaded with doxorubicin and erbB2-siRNA, a 6-fold difference in the tumour volume was observed as compared to the untreated control [100]. The AuNPs were conjugated with the reactive moiety at the carboxyl-terminus of the tumour necrosis factor (TNF) receptor associated factors (TRAF) protein. The authors described the synergistic effects of co-delivered doxorubicin and siRNA in inhibition of cell proliferation and tumour suppression. Figure 4 shows the fabrication of their co-delivery system based on AuNPs. Table 6 shows the current combination of small molecule drug and siRNA co-delivery by using gold nanoparticles nanomaterials for different types of cancer treatment.

Figure 4.

Fabrication of the AuNP-based targeted drug delivery system (TDDS) with an engineered bi-functional recombinant fusion protein TRAF(C) (TR), loaded with doxorubicin and ERBB2-siRNA (Au-TR-DX-si). It was used for further studies in vitro and in vivo. Reprinted with permission from [100]. Copyright Royal Society of Chemistry 2012.

Table 6.

Summary of co-delivery of small molecule drug and siRNA by gold nanomaterials for cancer therapy.

| Delivery System | Small Molecule Drug | siRNA Target | Type of Cancer |

Cell Line | Testing Stage | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyelectrolyte polymers coated gold nanorods (AuNRs) |

Doxorubicin | KRAS | Pancreatic Cancer | Panc-1 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[95] |

| Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) combined with an engineered bi-functional recombinant fusion protein TRAF(C) (TR) | Doxorubicin | ERBB2 | Ovarian cancer | SK-OV-3, MDA-MB-231, A549, PANC-1, B16F10 |

In vitro

In vivo |

[100] |

| Layer-by-layer assembled gold nanoparticles (LbL-AuNP) | Imatinib mesylate | STAT3 | Melanoma cancer | B16F10 | In vivo | [101] |

Note: KRAS, KRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase; ERBB2, erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3.

4. Conclusions

There is an emerging trend in the use of combination therapy of drug-siRNA for cancer treatments. These experimental therapies rely increasingly on the use of nanostructured delivery vehicles to encapsulate and protect the therapeutics until it reaches the target. The most well-studied nanocarriers are mesoporous silica nanoparticles, dendrimers, polymers, liposomes and gold nanoparticles.

These structures fulfil the fundamental requirement of co-delivery systems of having low- or non-toxicity and biocompatibility. More complex challenges include tailoring their surface properties, designing suitable structures to entrap and protect the payload, prolonging their stability in the bloodstream, maximising targeted delivery and understanding their behaviour in the tumour environment. These are among the critical challenges and issues which need to be resolved before their successful implementation at the clinical level.

Given the advantage of co-delivering siRNA and drug simultaneously to achieve multi-target tumour therapy, there is a strong impetus for developing more materials that could improve the efficacy of these delivery systems. To conclude, the co-delivery of siRNA and small molecule drugs represent an emerging technology that warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgments

Chung, S.L. gratefully acknowledges the SEPRS scholarship from University of Nottingham Malaysia.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia (MOHE), grant number FRGS/1/2020/TK0/UNIM/03/3.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO Report on Cancer: Setting Priorities, Investing Wisely and Providing Care for All. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberts B., Johnson A., L. J. The Molecular Basis of Cancer-Cell Behavior. 4th ed. Garland Science; New York, NY, USA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute N.C. Types of Cancer Treatment. [(accessed on 28 August 2021)]; Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types.

- 5.Jin J.O., Kim G., Hwang J., Han K.H., Kwak M., Lee P.C.W. Nucleic acid nanotechnology for cancer treatment. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Rev. Cancer. 2020;1874:188377. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S.J., Kim M.J., Kwon I.C., Roberts T.M. Delivery strategies and potential targets for siRNA in major cancer types. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016;104:2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J., Wang Y., Zhu Y., Oupický D. Recent advances in delivery of drug-nucleic acid combinations for cancer treatment. J. Control. Release. 2013;172:589–600. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong Y., Siegwart D.J., Anderson D.G. Strategies, design, and chemistry in siRNA delivery systems. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019;144:133–147. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oh Y.K., Park T.G. siRNA delivery systems for cancer treatment. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009;61:850–862. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang D., Xu X., Zhang K., Sun B., Wang L., Meng L., Liu Q., Zheng C., Yang B., Sun H. Codelivery of doxorubicin and MDR1-siRNA by mesoporous silica nanoparticles-polymerpolyethylenimine to improve oral squamous carcinoma treatment. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018;13:187–198. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S150610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang M., Wang J., Li B., Meng L., Tian Z. Recent advances in mechanism-based chemotherapy drug-siRNA pairs in co-delivery systems for cancer: A review. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2017;157:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carvalho B.G., Vit F.F., Carvalho H.F., Han S.W., de la Torre L.G. Recent advances in co-delivery nanosystems for synergistic action in cancer treatment. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2021;9:1208–1237. doi: 10.1039/D0TB02168G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X., Sun A.N., Liu Y.J., Zhang W.J., Pang N., Cheng S.X., Qi X.R. Amphiphilic dendrimer engineered nanocarrier systems for co-delivery of siRNA and paclitaxel to matrix metalloproteinase-rich tumors for synergistic therapy. NPG Asia Mater. 2018;10:238–254. doi: 10.1038/s41427-018-0027-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malhotra M., Tomaro-Duchesneau C., Saha S., Prakash S. Intranasal Delivery of Chitosan—siRNA Nanoparticle Formulation to the Brain. In: Jain K.K., editor. Drug Delivery System. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2014. pp. 233–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ibraheem D., Elaissari A., Fessi H. Gene therapy and DNA delivery systems. Int. J. Pharm. 2014;459:70–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scholz C., Wagner E. Therapeutic plasmid DNA versus siRNA delivery: Common and different tasks for synthetic carriers. J. Control. Release. 2012;161:554–565. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sajid M.I., Moazzam M., Tiwari R.K., Kato S., Cho K.Y. Overcoming barriers for siRNA therapeutics: From bench to bedside. Pharmaceuticals. 2020;13:294. doi: 10.3390/ph13100294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsiao I.L., Fritsch-Decker S., Leidner A., Al-Rawi M., Hug V., Diabaté S., Grage S.L., Meffert M., Stoeger T., Gerthsen D., et al. Biocompatibility of Amine-Functionalized Silica Nanoparticles: The Role of Surface Coverage. Small. 2019;15:1805400. doi: 10.1002/smll.201805400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreira A.F., Dias D.R., Correia I.J. Stimuli-responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles for cancer therapy: A review. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016;236:141–157. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2016.08.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holban A.M., Grumezescu A.M., Andronescu E. Inorganic Nanoarchitectonics Designed for Drug Delivery and Anti-Infective Surfaces. Elsevier Inc.; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holban A.M., Grumezescu A. Nanoarchitectonics for Smart Delivery and Drug Targeting. William Andrew; Norwich, NY, USA: 2016. Nanocomposite Drug Carriers; pp. 261–284. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mamaeva V., Sahlgren C., Lindén M. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in medicine-Recent advances. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013;65:689–702. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He Y., Liang S., Long M., Xu H. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as potential carriers for enhanced drug solubility of paclitaxel. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2017;78:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santoso A.V., Susanto A., Irawaty W., Hadisoewignyo L., Hartono S.B. Chitosan modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a versatile drug carrier with pH dependent properties. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019;2114:020011. doi: 10.1063/1.5112395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar P., Tambe P., Paknikar K.M., Gajbhiye V. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as cutting-edge theranostics: Advancement from merely a carrier to tailor-made smart delivery platform. J. Control. Release. 2018;287:35–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elbialy N.S., Aboushoushah S.F., Sofi B.F., Noorwali A. Multifunctional curcumin-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles for cancer chemoprevention and therapy. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020;291:109540. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2019.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qi S.S., Sun J.H., Yu H.H., Yu S.Q. Co-delivery nanoparticles of anti-cancer drugs for improving chemotherapy efficacy. Drug Deliv. 2017;24:1909–1926. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2017.1410256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun B., Wang X., Liao Y.P., Ji Z., Chang C.H., Pokhrel S., Ku J., Liu X., Wang M., Dunphy D.R., et al. Repetitive Dosing of Fumed Silica Leads to Profibrogenic Effects through Unique Structure-Activity Relationships and Biopersistence in the Lung. ACS Nano. 2016;10:8054–8066. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b04143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hegde S., Krisnawan V.E., Herzog B.H., Zuo C., Breden M.A., Knolhoff B.L., Hogg G.D., Tang J.P., Baer J.M., Mpoy C., et al. Dendritic Cell Paucity Leads to Dysfunctional Immune Surveillance in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:289–307.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seelige R., Searles S., Bui J.D. Mechanisms regulating immune surveillance of cellular stress in cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018;75:225–240. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2597-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song Y., Zhou B., Du X., Wang Y., Zhang J., Ai Y., Xia Z., Zhao G. Folic acid (FA)-conjugated mesoporous silica nanoparticles combined with MRP-1 siRNA improves the suppressive effects of myricetin on non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020;125:109561. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao S., Xu M., Cao C., Yu Q., Zhou Y., Liu J. A redox-responsive strategy using mesoporous silica nanoparticles for co-delivery of siRNA and doxorubicin. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2017;5:6908–6919. doi: 10.1039/C7TB00613F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai Z., Chen Y., Zhang Y., He Z., Wu X., Jiang L.P. PH-sensitive CAP/SiO2 composite for efficient co-delivery of doxorubicin and siRNA to overcome multiple drug resistance. RSC Adv. 2020;10:4251–4257. doi: 10.1039/C9RA07894K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu X., Zhu Y. Preparation of magnetic mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a multifunctional platform for potential drug delivery and hyperthermia. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2016;17:229–238. doi: 10.1080/14686996.2016.1178055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maeda H. Polymer therapeutics and the EPR effect. J. Drug Target. 2017;25:781–785. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2017.1365878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park J., Choi Y., Chang H., Um W., Ryu J.H., Kwon I.C. Alliance with EPR effect: Combined strategies to improve the EPR effect in the tumor microenvironment. Theranostics. 2019;9:8073–8090. doi: 10.7150/thno.37198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou X., Chen L., Nie W., Wang W., Qin M., Mo X., Wang H., He C. Dual-responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles mediated codelivery of doxorubicin and Bcl-2 SiRNA for targeted treatment of breast cancer. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016;120:22375–22387. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b06759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pandey S.P., Shukla T., Dhote V.K., Mishra D.K., Maheshwari R., Tekade R.K. Basic Fundamentals of Drug Delivery. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA, USA: 2019. Use of Polymers in Controlled Release of Active Agents; pp. 113–172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deb P.K., Kokaz S.F., Abed S.N., Paradkar A., Tekade R.K. Basic Fundamentals of Drug Delivery. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA, USA: 2019. Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications of Polymers; pp. 203–267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wechsler M.E., Clegg J.R., Peppas N.A. The Interface of Drug Delivery and Regenerative Medicine. Volume 1–3. Elsevier Inc.; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 41.dos Santos Rodrigues B., Lakkadwala S., Sharma D., Singh J. Chitosan for Gene, DNA Vaccines, and Drug Delivery. Elsevier Inc.; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sung Y.K., Kim S.W. Recent advances in the development of gene delivery systems. Biomater. Res. 2019;23:8. doi: 10.1186/s40824-019-0156-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo X., Wang L., Wei X., Zhou S. Polymer-based drug delivery systems for cancer treatment. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2016;54:3525–3550. doi: 10.1002/pola.28252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yan T., Zhu S., Hui W., He J., Liu Z., Cheng J. Chitosan based pH-responsive polymeric prodrug vector for enhanced tumor targeted co-delivery of doxorubicin and siRNA. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020;250:116781. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu C., Chen Z., Wu S., Han Y., Wang H., Sun H., Kong D., Leng X., Wang C., Zhang L., et al. Micelle or polymersome formation by PCL-PEG-PCL copolymers as drug delivery systems. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2017;28:1905–1909. doi: 10.1016/j.cclet.2017.07.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Z., Feng H., Jin L., Zhang Y., Tian X., Li J. Polymeric micelle with pH-induced variable size and doxorubicin and siRNA co-delivery for synergistic cancer therapy. Appl. Nanosci. 2020;10:1903–1913. doi: 10.1007/s13204-020-01263-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arote R.B., Jere D., Jiang H.-L., Kim Y.-K., Choi Y.-J., Cho M.-H., Cho C.-S. Injectable Biomaterials. Woodhead Publishing; Cambridge, UK: 2011. Injectable polymeric carriers for gene delivery systems; pp. 235–259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gardini D., Lüscher C.J., Struve C., Krogfelt K.A. Tailored Nanomaterials for Antimicrobial Applications. Elsevier Inc.; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao X., Li F., Li Y., Wang H., Ren H., Chen J., Nie G., Hao J. Co-delivery of HIF1α siRNA and gemcitabine via biocompatible lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles for effective treatment of pancreatic cancer. Biomaterials. 2015;46:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lv H., Zhang S., Wang B., Cui S., Yan J. Toxicity of cationic lipids and cationic polymers in gene delivery. J. Control. Release. 2006;114:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fischer D., Bieber T., Li Y., Elsässer H.P., Kissel T. A novel non-viral vector for DNA delivery based on low molecular weight, branched polyethylenimine: Effect of molecular weight on transfection efficiency and cytotoxicity. Pharm. Res. 1999;16:1273–1279. doi: 10.1023/A:1014861900478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alinejad-Mofrad E., Malaekeh-Nikouei B., Gholami L., Mousavi S.H., Sadeghnia H.R., Mohajeri M., Darroudi M., Oskuee R.K. Evaluation and comparison of cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, and apoptotic effects of poly-l-lysine/plasmid DNA micro- and nanoparticles. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2019;38:983–991. doi: 10.1177/0960327119846924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rimann M., Lühmann T., Textor M., Guerino B., Ogier J., Hall H. Characterization of PLL-g-PEG-DNA nanoparticles for the delivery of therapeutic DNA. Bioconjug. Chem. 2008;19:548–557. doi: 10.1021/bc7003439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hershberger K.K., Gauger A.J., Bronstein L.M. Utilizing Stimuli Responsive Linkages to Engineer and Enhance Polymer Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Platforms. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021;4:4720–4736. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.1c00351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hopkins E., Sanvictores T., Sharma S. Urolithiasis. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island, FL, USA: 2020. Physiology, Acid Base Balance; pp. 19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suo A., Qian J., Xu M., Xu W., Zhang Y., Yao Y. Folate-decorated PEGylated triblock copolymer as a pH/reduction dual-responsive nanovehicle for targeted intracellular co-delivery of doxorubicin and Bcl-2 siRNA. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2017;76:659–672. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.03.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu Y., Zhang Y., Zhang W., Sun C., Wu J., Tang J. Reversing of multidrug resistance breast cancer by co-delivery of P-gp siRNA and doxorubicin via folic acid-modified core-shell nanomicelles. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2016;138:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Norouzi P., Amini M., Dinarvand R., Arefian E., Seyedjafari E., Atyabi F. Co-delivery of gemcitabine prodrug along with anti NF-κB siRNA by tri-layer micelles can increase cytotoxicity, uptake and accumulation of the system in the cancers. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2020;116:111161. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2020.111161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin C., Hu Z., Yuan G., Su H., Zeng Y., Guo Z., Zhong F., Jiang K., He S. HIF1α-siRNA and gemcitabine combination-based GE-11 peptide antibody-targeted nanomedicine for enhanced therapeutic efficacy in pancreatic cancers. J. Drug Target. 2019;27:797–805. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2018.1552276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yuan Z.Q., Chen W.L., You B.G., Liu Y., Li J.Z., Zhu W.J., Zhou X.F., Liu C., Zhang X.N. Multifunctional nanoparticles co-delivering EZH2 siRNA and etoposide for synergistic therapy of orthotopic non-small-cell lung tumor. J. Control. Release. 2017;268:198–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wen Z.M., Jie J., Zhang Y., Liu H., Peng L.P. A self-assembled polyjuglanin nanoparticle loaded with doxorubicin and anti-Kras siRNA for attenuating multidrug resistance in human lung cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;493:1430–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.09.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jin M., Jin G., Kang L., Chen L., Gao Z., Huang W. Smart polymeric nanoparticles with pH-responsive and PEG-detachable properties for co-delivering paclitaxel and survivin siRNA to enhance antitumor outcomes. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018;13:2405–2426. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S161426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu C., Liu W., Hu Y., Li W., Di W. Bioinspired tumor-homing nanoplatform for co-delivery of paclitaxel and siRNA-E7 to HPV-related cervical malignancies for synergistic therapy. Theranostics. 2020;10:3325–3339. doi: 10.7150/thno.41228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nasab S.H., Amani A., Ebrahimi H.A., Hamidi A.A. Design and preparation of a new multi-targeted drug delivery system using multifunctional nanoparticles for co-delivery of siRNA and paclitaxel. J. Pharm. Anal. 2021;11:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Joshi U., Filipczak N., Khan M.M., Attia S.A., Torchilin V. Hypoxia-sensitive micellar nanoparticles for co-delivery of siRNA and chemotherapeutics to overcome multi-drug resistance in tumor cells. Int. J. Pharm. 2020;590:119915. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen Y., Li B., Chen X., Wu M., Ji Y., Tang G., Ping Y. A supramolecular co-delivery strategy for combined breast cancer treatment and metastasis prevention. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2020;31:1153–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.cclet.2019.06.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang Y., Meng Y., Ye J., Xia X., Wang H., Li L., Dong W., Jin D., Liu Y. Sequential delivery of VEGF siRNA and paclitaxel for PVN destruction, anti-angiogenesis, and tumor cell apoptosis procedurally via a multi-functional polymer micelle. J. Control. Release. 2018;287:103–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ahmed K.S., Hussein S.A., Ali A.H., Korma S.A., Lipeng Q., Jinghua C. Liposome: Composition, characterisation, preparation, and recent innovation in clinical applications. J. Drug Target. 2019;27:742–761. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2018.1527337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sercombe L., Veerati T., Moheimani F., Wu S.Y., Sood A.K., Hua S. Advances and challenges of liposome assisted drug delivery. Front. Pharmacol. 2015;6:286. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Akbarzadeh A., Rezaei-sadabady R., Davaran S., Joo S.W., Zarghami N. Liposome: Classification, prepNew aspects of liposomesaration, and applications. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013;8:102. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-8-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kiaie S.H., Mojarad-Jabali S., Khaleseh F., Allahyari S., Taheri E., Zakeri-Milani P., Valizadeh H. Axial pharmaceutical properties of liposome in cancer therapy: Recent advances and perspectives. Int. J. Pharm. 2020;581:119269. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Filipczak N., Pan J., Yalamarty S.S.K., Torchilin V.P. Recent advancements in liposome technology. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020;156:4–22. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jose A., Labala S., Ninave K.M., Gade S.K., Venuganti V.V.K. Effective Skin Cancer Treatment by Topical Co-delivery of Curcumin and STAT3 siRNA Using Cationic Liposomes. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2018;19:166–175. doi: 10.1208/s12249-017-0833-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Qu M.H., Zeng R.F., Fang S., Dai Q.S., Li H.P., Long J.T. Liposome-based co-delivery of siRNA and docetaxel for the synergistic treatment of lung cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2014;474:112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oh H.R., Jo H.Y., Park J.S., Kim D.E., Cho J.Y., Kim P.H., Kim K.S. Galactosylated liposomes for targeted co-delivery of doxorubicin/vimentin sirna to hepatocellular carcinoma. Nanomaterials. 2016;6:141. doi: 10.3390/nano6080141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang C., Zhang S., Zhi D., Zhao Y., Cui S., Cui J. Co-delivery of paclitaxel and survivin siRNA with cationic liposome for lung cancer therapy. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020;585:124054. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2019.124054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yao Y., Su Z., Liang Y., Zhang N. pH-Sensitive carboxymethyl chitosan-modified cationic liposomes for sorafenib and siRNa co-delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015;10:6185–6198. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S90524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lymberopoulos A., Demopoulou C., Kyriazi M., Katsarou M., Demertzis N., Hatziandoniou S., Maswadeh H., Papaioanou G., Demetzos C., Maibach H., et al. Liposome percutaneous penetration in vivo. Toxicol. Res. Appl. 2017;1:239784731772319. doi: 10.1177/2397847317723196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Subongkot T., Ngawhirunpat T., Opanasopit P. Development of ultradeformable liposomes with fatty acids for enhanced dermal rosmarinic acid delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:404. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13030404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jiang T., Jin K., Liu X., Pang Z. Nanoparticles for Tumor Targeting. Elsevier Ltd.; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Abedi-Gaballu F., Dehghan G., Ghaffari M., Yekta R., Abbaspour-Ravasjani S., Baradaran B., Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J., Hamblin M.R. PAMAM dendrimers as efficient drug and gene delivery nanosystems for cancer therapy. Appl. Mater. Today. 2018;12:177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.apmt.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Thakore S.I., Solanki A., Das M. Exploring Potential of Polymers in Cancer Management. Elsevier Inc.; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li Y., Wang H., Wang K., Hu Q., Yao Q., Shen Y., Yu G., Tang G. Targeted Co-delivery of PTX and TR3 siRNA by PTP Peptide Modified Dendrimer for the Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer. Small. 2017;13:1602697. doi: 10.1002/smll.201602697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jain K. Dendrimers: Smart Nanoengineered Polymers for Bioinspired Applications in Drug Delivery. Elsevier Ltd.; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li J., Liang H., Liu J., Wang Z. Poly (amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimer mediated delivery of drug and pDNA/siRNA for cancer therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2018;546:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang X., Pan J., Yao M., Palmerston Mendes L., Sarisozen C., Mao S., Torchilin V.P. Charge reversible hyaluronic acid-modified dendrimer-based nanoparticles for siMDR-1 and doxorubicin co-delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020;154:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2020.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen K., Xin X., Qiu L., Li W., Guan G., Li G., Qiao M., Zhao X., Hu H., Chen D. Co-delivery of p53 and MDM2 inhibitor RG7388 using a hydroxyl terminal PAMAM dendrimer derivative for synergistic cancer therapy. Acta Biomater. 2019;100:118–131. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Du Rietz H., Hedlund H., Wilhelmson S., Nordenfelt P., Wittrup A. Imaging small molecule-induced endosomal escape of siRNA. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1–17. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15300-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bus T., Traeger A., Schubert U.S. The great escape: How cationic polyplexes overcome the endosomal barrier. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2018;6:6904–6918. doi: 10.1039/C8TB00967H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vermeulen L.M.P., Brans T., Samal S.K., Dubruel P., Demeester J., De Smedt S.C., Remaut K., Braeckmans K. Endosomal Size and Membrane Leakiness Influence Proton Sponge-Based Rupture of Endosomal Vesicles. ACS Nano. 2018;12:2332–2345. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b07583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ghaffari M., Dehghan G., Baradaran B., Zarebkohan A., Mansoori B., Soleymani J., Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J., Hamblin M.R. Co-delivery of curcumin and Bcl-2 siRNA by PAMAM dendrimers for enhancement of the therapeutic efficacy in HeLa cancer cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2020;188:110762. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.110762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mohammed A.F.A., Higashi T., Motoyama K., Ohyama A., Onodera R., Khaled K.A., Sarhan H.A., Hussein A.K., Arima H. In Vitro and In Vivo Co-delivery of siRNA and Doxorubicin by Folate-PEG-Appended Dendrimer/Glucuronylglucosyl-β-Cyclodextrin Conjugate. AAPS J. 2019;21:54. doi: 10.1208/s12248-019-0327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yaqoob S.B., Adnan R., Rameez Khan R.M., Rashid M. Gold, Silver, and Palladium Nanoparticles: A Chemical Tool for Biomedical Applications. Front. Chem. 2020;8:376. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sztandera K., Gorzkiewicz M., Klajnert-Maculewicz B. Gold Nanoparticles in Cancer Treatment. Mol. Pharm. 2019;16:1–23. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yin F., Yang C., Wang Q., Zeng S., Hu R., Lin G., Tian J., Hu S., Lan R.F., Yoon H.S., et al. A light-driven therapy of pancreatic adenocarcinoma using gold nanorods-based nanocarriers for co-delivery of doxorubicin and siRNA. Theranostics. 2015;5:818–833. doi: 10.7150/thno.11335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Beik J., Khateri M., Khosravi Z., Kamrava S.K., Kooranifar S., Ghaznavi H., Shakeri-Zadeh A. Gold nanoparticles in combinatorial cancer therapy strategies. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019;387:299–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2019.02.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dykman L.A., Khlebtsov N.G. Immunological properties of gold nanoparticles. Chem. Sci. 2017;8:1719–1735. doi: 10.1039/C6SC03631G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yafout M., Ousaid A., Khayati Y., El Otmani I.S. Gold nanoparticles as a drug delivery system for standard chemotherapeutics: A new lead for targeted pharmacological cancer treatments. Sci. Afr. 2021;11:e00685. doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2020.e00685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Singh S., Maurya P.K. Nanotechnology in Modern Animal Biotechnology: Recent Trends and Future Perspectives. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2019. pp. 29–65. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kotcherlakota R., Srinivasan D.J., Mukherjee S., Haroon M.M., Dar G.H., Venkatraman U., Patra C.R., Gopal V. Engineered fusion protein-loaded gold nanocarriers for targeted co-delivery of doxorubicin and erbB2-siRNA in human epidermal growth factor receptor-2+ ovarian cancer. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2017;5:7082–7098. doi: 10.1039/C7TB01587A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Labala S., Jose A., Chawla S.R., Khan M.S., Bhatnagar S., Kulkarni O.P., Venuganti V.V.K. Effective melanoma cancer suppression by iontophoretic co-delivery of STAT3 siRNA and imatinib using gold nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2017;525:407–417. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.03.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]