Abstract

Devil’s claw is the vernacular name for a genus of medicinal plants that occur in the Kalahari Desert and Namibia Steppes. The genus comprises two distinct species: Harpagophytum procumbens and H. zeyheri. Although the European pharmacopeia considers the species interchangeable, recent studies have demonstrated that H. procumbens and H. zeyheri are chemically distinct and should not be treated as the same species. Further, the sale of H. zeyheri as an herbal supplement is not legal in the United States. Four markers were tested for their ability to distinguish H. procumbens from H. zeyheri: rbcL, matK, nrITS2, and psbA-trnH. Of these, only psbA-trnH was successful. A novel DNA mini-barcode assay that produces a 178-base amplicon in Harpagophytum (specificity = 1.00 [95% confidence interval = 0.80–1.00]; sensitivity = 1.00 [95% confidence interval = 0.75–1.00]) was used to estimate mislabeling frequency in a sample of 23 devil’s claw supplements purchased in the United States. PCR amplification failed in 13% of cases. Among the 20 fully-analyzable supplements: H. procumbens was not detected in 75%; 25% contained both H. procumbens and H. zeyheri; none contained only H. procumbens. We recommend this novel mini-barcode region as a standard method of quality control in the manufacture of devil’s claw supplements.

Keywords: Harpagophytum procumbens, Harpagophytum zeyheri, mini-barcode, Pedaliaceae, psbA-trnH

1. Introduction

Harpagophytum (Pedaliaceae) is a genus of tuberous plants from the Kalahari Desert and Namibia Steppes that is commonly known as devil’s claw due to its hooked fruits [1]. The genus comprises two distinct species—H. procumbens and H. zeyheri—that have been separated on the basis of morphology [2,3,4] and chemistry [5]. Harpagophytum procumbens consists of two subspecies [3], H. procumbens subsp. procumbens, which occurs across Namibia, Botswana, and Northern South Africa, and H. procumbens subsp. transvaalense, which occurs only in the Limpopo region of South Africa. Harpagophytum zeyheri comprises three subspecies [3], H. zeyheri subsp. zeyheri, which is restricted in distribution to northeastern South Africa, and H. zeyheri subsp. schijffii and H. zeyheri subsp. sublobatum, which are both widely distributed across regions of Angola, Zambia, and Zimbabwe and the northern regions of Namibia and Botswana.

There are unsubstantiated reports of possible hybridization in the few places where H. procumbens and H. zeyheri are sympatric [4,6,7]. Although purporting to demonstrate hybridization, RAPD and ISSR data [7] are, at best, inconclusive: no species-specific genotype groups were detected [7], thus a definitive pattern of hybridization cannot possibly be observed; the published Principal Component Analysis [7]—which is inappropriate for detecting hybridization [8,9]—identifies five putative hybrids, but only one individual is truly intermediate while several non-hybrid samples are equally or more intermediate than the putative hybrids; and the published UPGMA dendrogram [7] refutes the hypothesis of hybridization because it nests the putative hybrids well within the two parental clusters rather than at the cluster base where hybrids are expected to appear [10].

In addition, morphological data [4] purportedly demonstrate hybridization, but they are not statistically significant: the published Discriminant Function Analysis (DFA) [4] improperly implemented DFA such that hybrids were assumed to be present rather than using DFA to test that supposition. In addition, measurements that violate the Gaussian distribution assumed by DFA [11] were included. If DFA is conducted on the five characteristics that do not deviate [12] significantly (p > 0.01) from the Gaussian distribution (arm width, seed column height, fruit length, fruit width, and fruit circumference), the putative hybrids [4] are classified without evidence of intermediacy (pp ≥ 0.99999). Independent of the improperly implemented DFA, no statistical test was conducted to determine if the putative hybrids were truly intermediate [4]: the character count procedure [9] employing the sign [13] and Scheffé [14] tests (p = 0.05) does not indicate intermediacy for any characters and thus no trace of hybridity was detected (p = 1.0).

Given this critical review, there are no published data showing evidence of hybridization between Harpagophytum species and further study of additional specimens and characteristics is needed to determine if hybridization does indeed occur.

Devil’s claw has traditionally been used to treat dyspepsia, fever, constipation, hypertension, and venereal disease [1]. Commercial preparations of H. procumbens are sold to treat arthritis in both the European and United States markets [15]. Harpagophytum zeyheri cannot be legally sold as an herbal supplement in the United States [16] but it was appended to the European Pharmacopeia [17]. Both species are wild sourced—primarily from Namibia [18].

Although clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of H. procumbens for musculoskeletal pain relief [19,20,21,22], animal and in vitro studies have produced conflicting results [23,24,25,26,27]. The suspected active compounds—harpagoside, harpagide, 8-p-coumaroyl-harpagide, and acteoside—inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 and 2 [28,29,30] and the pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-Iβ (IL-Iβ), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [31,32]. Harpagoside is the main anti-inflammatory agent, but it is less effective in isolation [31] and thus the constituents of H. procumbens are thought to have synergistic effects [33].

Commercial herbal supplements are most frequently sold as dry fragments or powders. As a result, the authentication of these materials has traditionally relied upon macro- and microscopic morphological examination along with chemical assays for specific compounds or classes of compounds [34]. In the last two decades, DNA-based assays have become more common with assays for specific plants (e.g., molecular marker-based methods that utilize simple sequence repeats (SSR) or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP)) and general untargeted analysis techniques (e.g., short fragment sequencing methods such as whole metagenome analysis and metabarcoding) now being prominently used [35,36,37]. DNA barcoding has emerged as a preferred method of herbal supplement authentication due to the fact that it generally works well with highly fragmented DNA from high-copy regions (e.g., plastid), can detect multiple species at once, and is relatively inexpensive. These characteristics make the method ideal for assaying the DNA in highly degraded herbal products.

Devil’s claw supplements are sold mainly in capsule or tablet form [38]. Thus, it is impossible to determine which species they contain without additional analysis. A reliable identification method to ensure correct labeling is needed. We aim to create and test a DNA mini-barcode assay for both Harpagophytum species.

2. Results

2.1. Reference Sequences

Reference sequences from four markers were generated from 39 morphologically identifiable specimens (Table 1). In total, 17 rbcL, 23 matK, 22 nrITS2, and 35 psbA-trnH barcodes were produced. Median sequence quality (B30 [39]) exceeds the requirements of the BARCODE data standard (version 2.3 [40]): 0.841 (IQR 0.682–0.936) for rbcL, 0.891 (IQR 0.649–0.941) for matK, 0.849 (IQR 0.682–0.879) for nrITS2, and 0.845 (IQR = 0.466–0.890) for psbA-trnH.

Table 1.

Morphologically identifiable reference samples used to generate rbcL, matK, nrITS2, psbA-trnH and/or psbA-trnH mini-barcode sequences and to validate the psbA-trnH mini-barcode. Standard herbarium codes are used [41]. Cultivated specimens are indicated, all others are presumed to be wild collected. All sequences except EU531713 [42] were produced for this study.

| Species | Voucher Specimen | Locality | Sample Type | GenBank Accession | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rbcL | matK | nrITS2 | psbA-trnH | ||||

| Dicerocaryum zanguebarium | Loeb and Koch 339 (NY) | Namibia: Oshikango | reference and validation | — | — | — | KT717163 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Allen 308 (M0) | Botswana: Orapa | reference and validation | — | KT717103 | KT717127 | KT717148 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Davidse and Loxton 6296 (MO) | Namibia: Keetmanshoop | reference and validation | KT717178 | KT717109 | KT717133 | KT717153 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | de Koning 8142 (MO) | Mozambique: Chigubo | reference | — | KT717110 | — | — |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Dinter 396 (MO) | Namibia: Okahandja | reference and validation | — | — | — | KT717150 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Grignon 239 (MO) | Botswana: Ghanzi | reference and validation | KT717174 | KT717104 | KT717128 | KT717149 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Hardy 6575 (MO) | Namibia: Aranos | reference and validation | KT717168 | KT717095 | KT717124 | KT717154 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Herman 1264 (MO) | South Africa: Blouberg Privaatnatuurreserwe | reference and validation | KT717176 | KT717107 | KT717131 | KT717151 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Lavranos and Bleck 22701 (MO) | Namibia: Otjiwarongo | reference and validation | KT717177 | KT717108 | KT717132 | KT717152 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Lavranos and Bleck 22703 (MO) | Namibia: Khorixas | reference and validation | KT717173 | KT717102 | KT717126 | KT717147 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Leach 10682 (MO) | Zimbabwe: Beit Bridge | reference | — | KT717099 | — | — |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Long and Rae 44 (MO) | Botswana: Jwaneng | reference and validation | KT717171 | KT717101 | KT717120 | KT717145 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Ngoni 257 (MO) | Botswana: Mosu | reference | — | KT717105 | KT717129 | KY706349 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Owens 19 (MO) | Botswana: Deception Valley | reference and validation | KT717172 | KT717096 | KT717125 | KT717146 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Rodin 3539 (NY) | South Africa: Vryburg | reference | — | — | — | KY706351 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Rogers s.n. (MO) | South Africa: Bellville | reference | — | KT717097 | — | KY706348 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Sidey 305 (MO) | South Africa: Fauresmith | reference and validation | KT717169 | KT717098 | KT717119 | KT717143 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Skarpe S-319 (MO) | Botswana: Hukuntsi | reference and validation | KT717170 | KT717100 | KT717123 | KT717144 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Smuts and Gillelt 2130 (MO) | South Africa: Rooikop | validation | — | — | — | — |

| Harpagophytum procumbens | Venter 9637 (MO, NY) | South Africa: Glen Agricultural College | reference | KT717175 | KT717106 | KT717130 | KY706350 |

| Harpagophytum zeyheri | Germishuizen 00733 (MO) | South Africa: Bamboeskloof | reference and validation | — | KT717114 | KT717122 | KT717159 |

| Harpagophytum zeyheri | Germishuizen 990 (MO) | South Africa: Vaalwater | reference and validation | KT717183 | — | KT717138 | KT717160 |

| Harpagophytum zeyheri | Luwiika et al. 335 (MO) | Zambia: Lukona Basic School | reference | — | KT717116 | KT717137 | — |

| Harpagophytum zeyheri | Mashasha 111 (MO) | Zimbabwe: Victoria Falls | reference and validation | KT717179 | KT717111 | KT717134 | KT717155 |

| Harpagophytum zeyheri | Mogg 37171 (MO) | South Africa: Sandsloot | reference and validation | KT717182 | KT717113 | KT717136 | KT717157 |

| Harpagophytum zeyheri | Moyo 7 (MO) | Zimbabwe: Victoria Falls | reference | — | — | KT717118 | — |

| Harpagophytum zeyheri | Norlindh and Weimarck 5234 (NY) | South Africa: Pietersburg | reference | — | — | — | KY706353 |

| Harpagophytum zeyheri | Rodin 9140 (MO) | Namibia: Rundu | reference and validation | KT717184 | KT717115 | KT717121 | KT717158 |

| Harpagophytum zeyheri | Rushworth 110 (MO) | Zimbabwe: Dina Pan | reference and validation | KT717180 | KT717094 | KT717135 | KT717156 |

| Harpagophytum zeyheri | Yalala 300 (MO) | Botswana: Mahalapye | reference | KT717181 | KT717112 | KT717117 | KY706352 |

| Josephinia euginiae | Michell and Boyce 3144 (MO) | Australia: Nitmiluk National Park | reference and validation | — | — | — | KT717162 |

| Pedaliodiscus macrocarpus | Luke et al. TPR 73 (MO) | Kenya: Tana River National Primate Reserve | reference and validation | — | — | — | KT717139 |

| Pedalium murex | Comanor 608 (NY) | Sri Lanka: Potuvil—Panama Road | reference and validation | — | — | — | KT717140 |

| Pterodiscus auranthacus | Seydel 4135 (NY) | Namibia: Windhoek | reference and validation | — | — | — | KT717141 |

| Pterodiscus speciosus | Zietsman 4079 (NY) | South Africa: Hoopstad | reference and validation | — | — | — | KT717142 |

| Rogeria adenophylla | Seydel 4368 (NY) | Namibia: Windhoek | reference and validation | — | — | — | KT717167 |

| Sesamum indicum | Donmez 9932 (NY) | Turkey: Kula | reference and validation | — | — | — | KT717164 |

| Sesamum indicum | Nesbitt 1939 (RNG) | — | reference | — | — | — | EU531713 |

| Sesamum radiatum | Thomas 10563 (NY) | Brazil: Ilhéus | reference and validation | — | — | — | KT717165 |

| Sesamum triphyllum | Zietsman and Peyper 4061 (NY) | South Africa: Petrusburg | reference and validation | — | — | — | KT717161 |

| Uncarina grandidieri | Falk 97001 (NY) | cultivated | reference and validation | — | — | — | KT717166 |

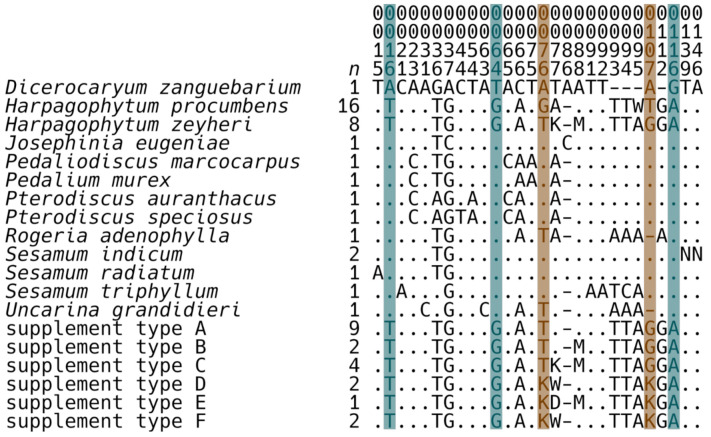

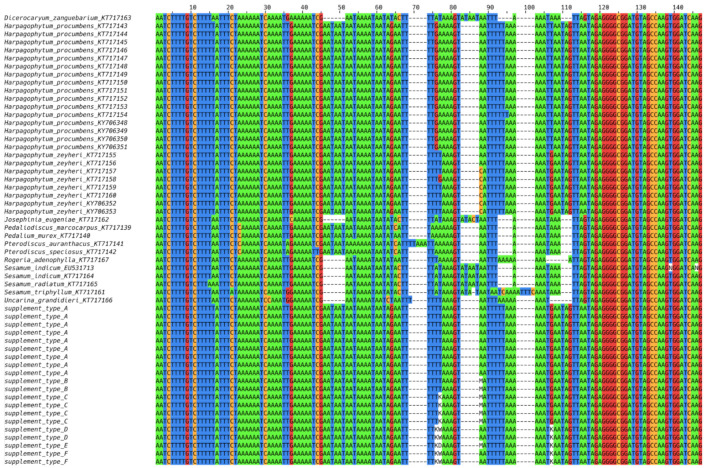

Within Harpagophytum, variation was only observed in psbA-trnH (Figure 1, Figure A1). Harpagophytum can be unambiguously distinguished from all other Pedaliaceae by alignment positions 16, 64, and 116. The two Harpagophytum species can be differentiated by alignment positions 76 and 107. Intraspecific variation was observed in reference samples of both H. procumbens (alignment position 95) and H. zeyheri (alignment positions 77 and 88). Only one of these variants is exactly correlated with geography or current taxonomy: position 77 distinguishes H. zeyheri subsp. suboblatum (sample from Namibia) from H. zeyheri subsp. zeyheri (samples from South Africa). No samples of H. zeyheri subsp. schijffii were available for examination.

Across Pedaliaceae, the psbA-trnH alignment is 427 columns and has 13 unique insertion/deletion (indel) events ranging from 1–13 bases (median 6; IQR 4–7). The unaligned sequences range from 367–394 bases (median 383; IQR 373–383). Within Harpagophytum, the psbA-trnH sequences are uniformly 383 bases without any evidence of indels.

2.2. Mini-Barcode Validation

Validation psbA-trnH mini-barcode (n = 30) median sequence quality was 0.569 (IQR 0.532–0.587). BRONX [43] was able to correctly identify all H. procumbens validation samples and exclude H. procumbens as a possible identification for all other validation samples (n = 13 H. procumbens; n = 17 other species; specificity = 1.00 [95% confidence interval = 0.80–1.00]; sensitivity = 1.00 [95% confidence interval = 0.75–1.00]; [44]). The absolute consistency of alignment positions 16, 64, 76, 107, and 116 prevent infraspecific variation from having any bearing on Harpagophytum species identification.

2.3. An Analysis of Herbal Supplements

Amplifiable DNA was extracted from 20 of 23 (87%) herbal supplements. Amplification success was significantly correlated with the reports of root extract on product labels (McNemar test [45]; p = 0.04331; Table 2). The failure rate for samples labeled as having root extract (17%) was nearly double that of samples without root extract (9%; Table 2).

Table 2.

Herbal dietary supplement label ingredients and psbA-trnH mini-barcode determination. Supplement sequence type corresponds to those in Figure 1. If Latin names were not provided on the product label, the Latin name was determined using [16]. Despite being noted on some labels, the sale of supplements containing H. zeyheri is not legal in the United States.

| Supplement Sequence Type | Label Species | Devil’s Claw Material Type | Contains H. procumbens | Contains H. zeyheri |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Harpagophytum procumbens, Curcuma longa, Crataegus oxyacantha, Arctium lappa, Smilax febrifuga, Yucca schidigera, Zingiber officinale, and Vaccinium myrtillus | root extract | no | yes |

| A | Harpagophytum procumbens | root | no | yes |

| A | Harpagophytum procumbens | root | no | yes |

| A | Boswellia serrata, Curcuma longa, and Harpagophytum procumbens | root extract | no | yes |

| A | Boswellia serrata, Uncaria tomentosa, Harpagophytum procumbens, Yucca schidigera, Gymnema sylvestre, Curcuma longa, Camellia sinensis, and Oryza sativa | root | no | yes |

| A | Harpagophytum procumbens and Oryza sativa | root extract | no | yes |

| A | Harpagophytum procumbens | root extract | no | yes |

| A | Harpagophytum procumbens | root | no | yes |

| A | Harpagophytum procumbens, Boswellia serrata, Curcuma longa, and Tanacetum parthenium | root extract | no | yes |

| B | Harpagophytum procumbens | root | no | yes |

| B | Harpagophytum procumbens | root extract | no | yes |

| C | Harpagophytum procumbens | root | no | yes |

| C | Harpagophytum procumbens and Oryza sativa | root extract | no | yes |

| C | Harpagophytum procumbens | root | no | yes |

| C | Harpagophytum procumbens | root | no | yes |

| D | Harpagophytum procumbens | root | yes | yes |

| D | Harpagophytum procumbens and/or Harpagophytum zeyheri | root extract | yes | yes |

| E | Harpagophytum procumbens | root and root extract | yes | yes |

| F | Harpagophytum procumbens | root | yes | yes |

| F | Harpagophytum procumbens and/or Harpagophytum zeyheri | root extract | yes | yes |

| — | Harpagophytum procumbens | root | unknown | unknown |

| — | Polygonum cuspidatum, Curcuma longa, Zingiber officinale, Camellia sinensis, Harpagophytum procumbens, and Salix alba | root extract | unknown | unknown |

| — | Harpagophytum procumbens | root extract | unknown | unknown |

PCR products were successfully sequenced for all 20 amplifiable supplements: mini-barcode median sequence quality was 0.561 (IQR 0.451–0.587)—very similar to the quality of the validation samples.

Harpagophytum zeyheri was found in all 20 fully-analyzable samples: all supplements contained either H. zeyheri (75%; 15/20; Types A, B, and C; a “T” at alignment position 76 and a “G” at alignment position 107; Figure 1, Table 2) or a combination of H. procumbens and H. zeyheri (25%; 5/20; Types D, E, and F; a “K” [“G” and “T”] at alignment positions 76 and 107; Figure 1, Table 2); no supplements contained only H. procumbens.

Figure 1.

Variable nucleotides within the psbA-trnH mini-barcode (voucher information is in Table 1; herbal dietary supplement information is in Table 2; the full alignment is in Figure A1). Alignment positions are numbered vertically. Bases identical to the first sequence are indicated with “.”. Variable bases are indicated with standard International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) codes: D = {AGT}, K = {GT}, M = {AC}, N = {ACGT}, and W = {AT}. The number of sequences summarized (n) for each species/supplement type is indicated. Alignment positions that unambiguously distinguish Harpagophytum from all other Pedaliaceae (16, 64, and 116) are highlighted in blue. The alignment positions 76 and 107—which distinguish between the two Harpagophytum species—are highlighted in orange.

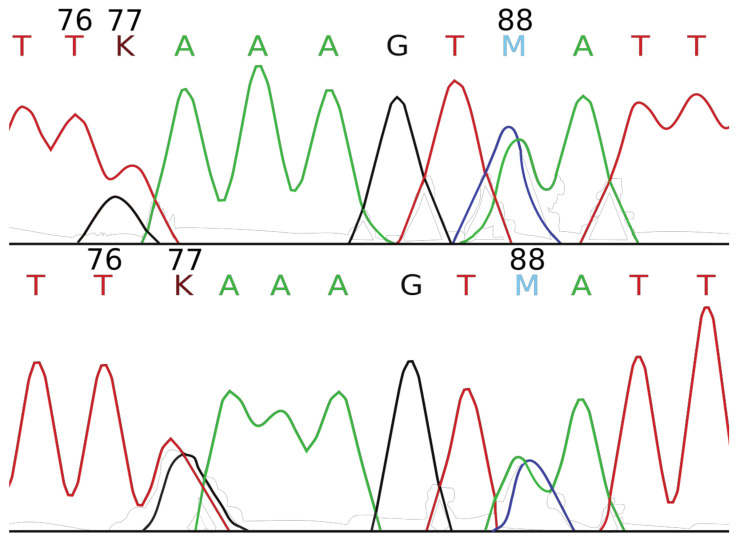

Types A, B, and C contain H. zeyheri haplotypes that exhibit the same variation found in the reference samples. Type A is composed of samples that contain only one H. zeyheri haplotype, while types B and C are mixtures of H. zeyheri haplotypes (e.g., Figure 2). In contrast, types D, E, and F are mixtures of H. procumbens and H. zeyheri haplotypes. Type E contains one H. procumbens haplotype and two H. zeyheri haplotypes (a “D” [“A”, “G” and “T”] at alignment position 77; Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Portions of forward (top) and reverse (bottom) Sanger sequencing chromatograms demonstrating polymorphic positions (alignment positions 77 and 88) in herbal supplement mini-barcode sequences of a Type C sequence. Diagnostic nucleotides (Figure 1) are indicated by their alignment position; “A” = green; “G” = black; “K” = maroon {GT}; “M” = indigo {AC}; “T” = red. Despite the supplement being labeled as containing only H. procumbens, alignment position 76 indicates that this sample is composed exclusively of H. zeyheri.

3. Discussion

The psbA-trnH mini-barcode absolutely differentiates Harpagophytum from all other Pedaliaceae (Figure 1: blue highlighted positions 16, 64, and 116) and in turn H. procumbens and H. zeyheri from one another (Figure 1: orange highlighted positions 76 and 107). Thus, the species have consistent character state differences and can be considered distinct phylogenetic species [46]. The absolute consistency of psbA-trnH mini-barcode alignment positions 16, 64, 76, 107, and 116 prevent infraspecific variation from having any bearing on repeatable Harpagophytum species identification (specificity = 1.00 [95% confidence interval = 0.80–1.00]; sensitivity = 1.00 [95% confidence interval = 0.75–1.00]). Although there are reports of possible interbreeding between the two Harpagophytum species [4,6,7], the pattern observed here is inconsistent with hybridization because the morphological and molecular species identifications exactly match. No intermediate morphological phenotypes have been confirmed either in the literature or in our research, suggesting that hybrids, if they exist, have retained strong morphological similarity to one of the parental species. Therefore, absolute rejection of the hybridization hypothesis would require the investigation of multiple biparentally inherited molecular markers. Given the lack of support for the supposition of hybridization in the data, the regulatory distinction between H. procumbens and H. zeyheri in the United States [16] can be enforced.

The variation within the psbA-trnH mini-barcode used to differentiate between the two Harpagophytum species could be assayed using molecular techniques other than the Sanger sequencing method demonstrated here. For instance, one could use PCR-RFLP with AseI (5′-ATTAAT-3′) to assay alignment position 107 (H. procumbens will cut, but H. zeyheri will not); RT-PCR with specific primers and/or probes targeted to alignment positions 16, 64, 76, 107, and/or 116; or short read genome skimming (e.g., Illumina) with appropriate bioinformatic postprocessing to find alignment positions 16, 64, 76, 107, and 116 in the output sequences. Depending upon the needs of the user, each of these techniques could be conducted in such a way as to quantify the relative or absolute amounts of DNA from each species present in the sample.

The observed mini-barcode PCR amplification failure rate from herbal supplements of 13% is a bit high compared to the 3–10% reported for similar studies [47,48,49]. Although the processing of plant materials for herbal supplement manufacturing frequently results in DNA fragmentation and destruction [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70] that can prevent amplification, the processing techniques used for devil’s claw may be more damaging than those used for other herbal supplements studied thus far—which is supported by the significant correlation between reports of root extract (a relatively damaging technique [70]) on product labels and PCR failure (McNemar test [45]; p = 0.04331; Table 2). It is also possible that some, or all, of the high rate of PCR failure can be attributed to the amount of recoverable DNA in devil’s claw tap roots being low and/or less enzymatically accessible in comparison to aerial parts as is the case in carrot (Daucus carota) tap roots [71,72].

Labels of only two of the 20 analyzable supplements (Table 2) list Harpagophytum zeyheri, but H. zeyheri was found in all 20 fully-analyzable samples. Somehow the two, predominantly allopatric [1], species were mixed. Although H. zeyheri can be legally sold in the European Union [17], it cannot be sold in the United States [16].

Bulk materials of devil’s claw are usually sold in a morphologically unidentifiable state [1,5]. Thus, a chemical test that measures the relative quantity of harpagoside and 8-p-coumaroyl-harpagide is often used to distinguish between bulk materials from the two species [73]. The data that purport to validate the assay were not analyzed statistically [73]. Unfortunately, the data do not statistically differentiate between the Harpagophytum species (Mann–Whitney test [74]; p = 0.1386)—perhaps due to the miniscule sample size (n = 5). Therefore, this chemical assay cannot be considered reliable. Revalidation with additional, morphologically identifiable and vouchered samples may redeem this assay for harpagoside and 8-p-coumaroyl-harpagide.

Due to the legal status of H. zeyheri in the United States, it is imperative that supplement manufacturers employ a robust method of quality control to evaluate all devil’s claw supplements sold. Because the mini-barcode presented here is reliable, cost-efficient, and simple to use, we recommend it as a standard method of quality control instead of the relative quantity of harpagoside and 8-p-coumaroyl-harpagide.

4. Materials and Methods

A barcode reference database of rbcL, matK, nrITS2, and psbA-trnH sequences was created from morphologically identifiable samples of Pedaliaceae. Specimen identifications followed standard references [3,6,75]. Sequences outside Harpagophytum were sampled from close (Pterodiscus, Pedaliodiscus, Pedalium, Uncarina, and Rogeria) and distant relatives (Dicerocaryum, Josephinia, and Sesamum; Table 1; [76]).

Validation samples were chosen arbitrarily (n = 30; Table 1). Herbal supplements (capsules and compression tablets) were purchased online.

A psbA-trnH mini-barcode was designed from all Pedaliaceae reference sequences. The mini-barcode is anchored within the intergenic spacer (alignment positions 1–122) and extends into trnH (alignment positions 123–147; Figure A1). This region was selected for its compactness and discriminatory power.

DNA was isolated [48] from leaves of reference and validation samples and powdered herbal supplements. Markers were amplified using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Each 15 µL reaction contained 1.5 µL PCR buffer (200 mM tris pH 8.8, 100 mM KCl, 100 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM MgSO4, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 50% (w/v) sucrose, 0.25% (w/v) cresol red, and 0.25 µg/µL BSA), 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 1.0 µM of each amplification primer, 0.5 units of Taq polymerase, and 0.5 µL DNA. Primer sequences and cycling conditions are given in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

PCR primers used for amplification and sequencing.

| Marker | Primer Name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| matK | 1R | ACCCAGTCCATCTGGAAATCTTGGTTC | K.J. Kim (pers. com.) |

| matK | 3F | CGTACAGTACTTTTGTGTTTACGAG | K.J. Kim (pers. com.) |

| nrITS2 | S2F | ATGCGATACTTGGTGTGAAT | [77] |

| nrITS2 | S3R | GACGCTTCTCCAGACTACAAT | [77] |

| psbA-trnH | psbAF | GTTATGCATGAACGTAATGCTC | [78] |

| psbA-trnH | trnHR | CGCGCATGGTGGATTCACAAATC | [78] |

| psbA-trnH mini-barcode | F | GAAGATAAATGAAATGATTGAAATGC | novel |

| psbA-trnH mini-barcode | R | TGGATTCACAAATCCACTGC | novel |

| rbcL | 32F | TTGGATTCAAAGCTGGTGTT | [79] |

| rbcL | a_F | ATGTCACCACAAACAGAGACTAAAGC | [80] |

| rbcL | ajf634R | GAAACGGTCTCTCCAACGCAT | [81] |

Table 4.

PCR cycling conditions used. Amplification reactions used an initial denaturation of 150 s at 95 °C and a final extension of 600 s at 72 °C (psbA-trnH used 64 °C). Primer names correspond to those in Table 3.

| Marker | Primers | Cycling |

|---|---|---|

| matK | 1R & 3F | 10 × {30 s, 95 °C; 30 s, 56 °C; 30 s, 72 °C}; 25 × {30 s, 88 °C; 30 s, 56 °C; 30 s, 72 °C} |

| nrITS2 | S2F & S3R | 35 × {30 s, 95 °C; 30 s, 56 °C; 30 s, 72 °C} |

| psbA-trnH | psbAF & trnHR | 10 × {30 s, 95 °C; 120 s, 55 °C}; 23 × {45 s, 90 °C; 120 s, 55 °C} |

| psbA-trnH mini-barcode | F & R | 35 × {30 s, 95 °C; 120 s, 58 °C} |

| rbcL | 32F & ajf634R | 35 × {30 s, 95 °C; 30 s, 58 °C; 30 s, 72 °C} |

| rbcL | a_F & ajf634R | 35 × {30 s, 95 °C; 30 s, 58 °C; 30 s, 72 °C} |

PCR products were treated with ExoSapIt (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA), and sequenced bidirectionally on a 3730 automated sequencer (ThermoFisher) using the amplification primers and BigDye 3.1 (ThermoFisher).

KB 1.4 (ThermoFisher) was used to generate base calls and quantity values from raw chromatograms. Contigs were assembled and edited with Sequencher (version 5.2.3; Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI). Sequence quality was determined using B (version 1.2; [39]) with expected coverage (x) set to the number of reads. Newly generated mini-barcode sequences were compared to reference sequences using BRONX (version 2.0; [43]). R version 3.3.1 (http://www.R-project.org, accessed on 21 August 2021) was used to calculate discriminant function analysis [11], the Mann–Whitney test [74], the McNemar test [45], the Scheffé [14] test, the Shapiro–Wilk test [12], the sign test [13], and specificity and sensitivity [44].

Acknowledgments

We thank Christian Schulz for translating reference material from the German.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Full psbA-trnH mini-barcode alignment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.P.L.; methodology, G.L.D.-S. and J.D.; writing—original draft preparation, G.L.D.-S. and D.P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Sequences were deposited in GenBank accessions KT717094–KT717184 and KY706348–KY706353.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stewart K.M., Cole D. The commercial harvest of Devil’s Claw (Harpagophytum spp.) in Southern Africa: The Devil’s in the details. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;100:225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Decaisne J. Revue du groupe des pedalinees. Ann. Sci. Nat. Bot. 1865;5:321–336. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ihlenfeldt H.-D., Hartmann H. Die gattung Harpagophytum (Burch.) DC. Ex Meissn. (Monographie Der Afrikanischen Pedaliaceae II) Mitt. Aus Dem Staatsinst. Fur Allg. Bot. Hambg. 1970;13:15–69. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muzila M., Setshogo M.P., Mpoloka S.W. Multivariate Analysis of Harpagophytum DC. Ex Meisn (Pedaliaceae) based on fruit characters. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. 2011;3:101–109. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mncwangi N.P., Viljoen A.M., Zhao J., Vermaak I., Chen W., Khan I. What the devil is in your phytomedicine? Exploring species substitution in Harpagophytum through chemometric modeling of 1H-NMR and UHPLC-MS datasets. Phytochemistry. 2014;106:104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ihlenfeldt H.-D. Flora Zambesiaca. Volume 8. Royal Botanic Gardens Kew; Richmond, Surrey, UK: 1988. Pedaliaceae; pp. 86–113. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muzila M., Werlemark G., Ortiz R., Sehic J., Fatih M., Setshogo M., Mpoloka W., Nybom H. Assessment of diversity in Harpagophytum with RAPD and ISSR markers provides evidence of introgression. Hereditas. 2014;151:91–101. doi: 10.1111/hrd2.00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pimental R.A. A comparative study of data and ordination techniques based on a hybrid swarm of sand verbenas (Abronia Juss.) Syst. Zool. 1981;30:250–267. doi: 10.2307/2413248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson P. On inferring hybridity from morphological intermediacy. Taxon. 1992;41:11–23. doi: 10.2307/1222481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDade L.A. Hybrids and phylogenetic systematics III. Comparison with distance methods. Syst. Bot. 1997;22:669–683. doi: 10.2307/2419434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher R.A. The use of multiple measurements in taxonomic problems. Ann. Eugen. 1936;7:179–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1936.tb02137.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapiro S.S., Wilk M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples) Biometrika. 1965;52:591–611. doi: 10.1093/biomet/52.3-4.591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arbuthnott J. An argument for divine providence, taken from the constant regularity observ’d in the births of both sexes. Philos. Trans. 1710;27:186–190. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheffé H. A method for judging all contrasts in the analysis of variance. Biometrika. 1953;40:87–104. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall N.T. Searching for a Cure: Conservation of Medicinal Wildlife Resources in East and Southern Africa. Traffic International; Cambridge, UK: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGuffin M., Kartesz J.T., Leung A.Y., Tucker A.O. 2nd ed. American Herbal Products Association; Silver Spring, MD, USA: 2000. Herbs of Commerce. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grote K. The Increased Harvest and Trade of Devil’s Claw (Harpagophytum procumbens) and Its Impacts on the Peoples and Environment of Namibia, Botswana and South Africa. Global Facilitation Unit for Underutilized Species; Maccarese, Italy: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raimondo D., Donaldson J. The Trade, Management and Biological Status of Harpagophytum Spp. in Southern African Range States. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora; Geneva, Switzerland: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chantre P., Cappelaere A., Leblan D., Guedon D., Vandermander J., Fournie B. Efficacy and tolerance of Harpagophytum procumbens versus diacerhein in treatment of osteoarthritis. Phytomedicine. 2000;7:177–183. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(00)80001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chrubasik S., Thanner J., Künzel O., Conradt C., Black A., Pollak S. Comparison of outcome measures during treatment with the proprietary Harpagophytum extract Doloteffin® in patients with pain in the lower back, knee or hip. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:181–194. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frerick H., Schmidt U. Stufenschema bei coxarthrose. Der Kassenarzt. 2001;5:34–41. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wegener T., Lüpke N. Treatment of patients with arthrosis of hip or knee with an aqueous extract of Devil’s Claw (Harpagophytum procumbens DC) Phytother. Res. 2003;17:1165–1172. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen M.L., Santos E.H.R., Maria de Lourdes V.S., da Silva A.A.B., Tufik S. Evaluation of acute and chronic treatments with Harpagophytum procumbens on Freund’s adjuvant–induced arthritis in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004;91:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baghdikian B., Lanhers M.C., Fleurentin J., Ollivier E., Maillard C., Balansard G., Mortier F. An analytical study and anti–inflammatory and analgesic effects of Harpagophytum procumbens and Harpagophytum zeyheri. Planta Med. 2007;63:171–176. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kundu J.K., Mossanda K.S., Na H.-K., Surh Y.-J. Inhibitory effects of the extracts of Sutherlandia frutescens (L.) R. Br. and Harpagophytum procumbens DC. on phorbol ester–Induced COX-2 expression in mouse skin: AP-1 and CREB as potential upstream targets. Cancer Lett. 2005;218:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLeod D.W., Revell P., Robinson B.V. Investigations of Harpagophytum procumbens (Devil’s Claw) in the treatment of experimental inflammation and arthritis in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1979;66:140P–141P. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitehouse L.W., Znamirowska M., Paul C.J. Devil’s Claw (Harpagophytum procumbens): No evidence for anti–inflammatory activity in the treatment of arthritic disease. Can. Med Assoc. J. 1983;129:249–251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdelouahab N., Heard C. Effect of the major glycosides of Harpagophytum procumbens (Devil’s Claw) on epidermal cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) Vitro. J. Nat. Prod. 2008;71:746–749. doi: 10.1021/np070204u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gyurkovska V., Alipieva K., Maciuk A., Dimitrova P., Ivanovska N., Haas C., Bley T., Georgiev M. Anti–inflammatory activity of Devil’s Claw in vitro systems and their active constituents. Food Chem. 2011;125:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.08.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jang M.-H., Lim S., Han S.-M., Park H.-J., Shin I., Kim J.-W., Kim N.-J., Lee J.-S., Kim K.-A., Kim C.-J. Harpagophytum procumbens suppresses lipopolysaccharide–stimulated expressions of cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase in fibroblast cell line L929. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2003;93:367–371. doi: 10.1254/jphs.93.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiebich B.L., Heinrich M., Hiller K.O., Kammerer N. Inhibition of TNF-α synthesis in LPS–stimulated primary human monocytes by Harpagophytum extract SteiHap 69. Phytomedicine. 2001;8:28–30. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inaba K., Murata K., Naruto S., Matsuda H. Inhibitory effects of Devil’s Claw (secondary root of Harpagophytum procumbens) extract and harpagoside on cytokine production in mouse macrophages. J. Nat. Med. 2010;64:219–222. doi: 10.1007/s11418-010-0395-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Georgiev M.I., Ivanovska N., Alipieva K., Dimitrova P., Verpoorte R. Harpagoside: From Kalahari Desert to pharmacy shelf. Phytochemistry. 2013;92:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ichim M.C., Häser A., Nick P. Microscopic authentication of commercial herbal products in the globalized market: Potential and limitations. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11:876. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grazina L., Amaral J.S., Mafra I. Botanical origin authentication of dietary supplements by DNA–based approaches. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020;19:1080–1109. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raclariu A.C., Heinrich M., Ichim M.C., Boer H. Benefits and limitations of DNA barcoding and metabarcoding in herbal product authentication. Phytochem. Anal. 2018;29:123–128. doi: 10.1002/pca.2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anantha Narayana D.B., Johnson S.T. DNA Barcoding in authentication of herbal raw materials, extracts and dietary supplements: A perspective. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2019;13:201–210. doi: 10.1007/s11816-019-00538-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grant L., McBean D.E., Fyfe L., Warnock A.M. A review of the biological and potential therapeutic actions of Harpagophytum procumbens. Phytother. Res. 2007;21:199–209. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Little D.P. A Unified index of sequence quality and contig overlap for DNA barcoding. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2780–2781. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanner R. Proposed Standards for BARCODE Records in INSDC (BRIs) Database Working Group, Consortium for the Barcode of Life; Washington, DC, USA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thiers B. Index Herbariorum: A Global Directory of Public Herbaria and Associated Staff. [(accessed on 25 August 2021)]. Available online: http://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/

- 42.Kool A., de Boer H.J., Krüger Å., Rydberg A., Abbad A., Björk L., Martin G. Molecular identification of commercialized medicinal plants in Southern Morocco. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Little D.P. DNA Barcode sequence identification incorporating taxonomic hierarchy and within taxon variability. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e20552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thorner R.M., Remein Q.R. Principals and Procedures in the Evaluation of Screening for Disease. United States Public Health Service; Washington, DC, USA: 1961. p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McNemar Q. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika. 1947;12:153–157. doi: 10.1007/BF02295996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nixon K.C., Wheeler Q.D. An amplification of the phylogenetic species concept. Cladistics. 1990;6:211–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1990.tb00541.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker D.A., Stevenson D.W., Little D.P. DNA barcode identification of black cohosh herbal dietary supplements. J. AOAC Int. 2012;95:1023–1034. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.11-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Little D.P. Authentication of Ginkgo biloba herbal dietary supplements using DNA barcoding. Genome. 2014;57:513–516. doi: 10.1139/gen-2014-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Little D.P., Jeanson M.L. DNA barcode authentication of saw palmetto herbal dietary supplements. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1–6. doi: 10.1038/srep03518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Busconi M., Foroni C., Corradi M., Bongiorni C., Cattapan F., Fogher C. DNA Extraction from olive oil and its use in the identification of the production cultivar. Food Chem. 2003;83:127–134. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(03)00218-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fernandes T.J.R., Oliveira M.B.P.P., Mafra I. Tracing transgenic maize as affected by breadmaking process and raw material for the production of a traditional maize bread, broa. Food Chem. 2013;138:687–692. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gryson N., Messens K., Dewettinck K. PCR detection of soy ingredients in bread. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008;227:345–351. doi: 10.1007/s00217-007-0727-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hellebrand M., Nagy M., Morsel J.T. Determination of DNA traces in rapeseed oil. Z. Lebensm. Forsch. A. 1998;206:237–242. doi: 10.1007/s002170050250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meyer R. Development and application of DNA analytical methods for the detection of GMOs in food. Food Control. 1999;10:391–399. doi: 10.1016/S0956-7135(99)00081-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murray S.R., Butler R.C., Hardacre A.K., Timmerman–Vaughan G.M. Use of quantitative real-time PCR to estimate maize endogenous DNA degradation after cooking and extrusion or in food products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:2231–2239. doi: 10.1021/jf0636061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oguchi T., Onishi M., Chikagawa Y., Kodama T., Suzuki E., Kasahara M., Akiyama H., Teshima R., Futo S., Hino A., et al. Investigation of residual DNAs in sugar from sugar beet (Beta vulgaris, L.) Food Hyg. Saf. Sci. 2009;50:41–46. doi: 10.3358/shokueishi.50.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Staats M., Cuenca A., Richardson J.E., Vrielink–van Ginkel R., Petersen G., Seberg O., Bakker F.T. DNA damage in plant herbarium tissue. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tilley M. PCR amplification of wheat sequences from DNA extracted during milling and baking. Cereal Chem. 2004;81:44–47. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM.2004.81.1.44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bryan G.J., Dixon A., Gale M.D., Wiseman G. A PCR–based method for the detection of hexaploid bread wheat adulteration of durum wheat and pasta. J. Cereal Sci. 1998;28:135–145. doi: 10.1006/jcrs.1998.0182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hupfer C., Hotzel H., Sachse K., Engel K.-H. Detection of the genetic modification in heat–treated products of Bt maize by polymerase chain reaction. Z. Lebensm. Forsch. A. 1998;206:203–207. doi: 10.1007/s002170050243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Straub J.A., Hertel C., Hammes W.P. Limits of a PCR–based detection method for genetically modified soya beans in wheat bread production. Z. Lebensm. Forsch. A. 1999;208:77–82. doi: 10.1007/s002170050380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bauer T., Weller P., Hammes W.P., Hertel C. The effect of processing parameters on DNA degradation in food. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2003;217:338–343. doi: 10.1007/s00217-003-0743-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Duggan P.S., Chambers P.A., Heritage J., Forbes J.M. Fate of genetically modified maize DNA in the oral cavity and rumen of sheep. Br. J. Nutr. 2003;89:159–166. doi: 10.1079/BJN2002764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sandberg M., Lundberg L., Ferm M., Malmheden Yman I. Real time PCR for the detection and discrimination of cereal contamination in gluten free foods. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2003;217:344–349. doi: 10.1007/s00217-003-0758-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen Y., Wang Y., Ge Y., Xu B. Degradation of endogenous and exogenous genes of roundup–ready soybean during food processing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53:10239–10243. doi: 10.1021/jf0519820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bergerová E., Godalova Z., Siekel P. Combined effects of temperature, pressure and low pH on the amplification of DNA of plant derived foods. Czech J. Food Sci. 2011;29:337–345. doi: 10.17221/217/2010-CJFS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bergerová E., Hrncirova Z., Stankovska M., Lopasovska M., Siekel P. Effect of thermal treatment on the amplification and quantification of transgenic and non–transgenic soybean and maize DNA. Food Anal. Methods. 2010;3:211–218. doi: 10.1007/s12161-009-9115-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Costa J., Mafra I., Amaral J.S., Oliveira M.B.P.P. Monitoring genetically modified soybean along the industrial soybean oil extraction and refining processes by polymerase chain reaction techniques. Food Res. Int. 2010;43:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2009.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Särkinen T., Staats M., Richardson J.E., Cowan R.S., Bakker F.T. How to open the treasure chest? Optimising DNA extraction from herbarium specimens. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lu Z., Rubinsky M., Babajanian S., Zhang Y., Chang P., Swanson G. Visualization of DNA in highly processed botanical materials. Food Chem. 2018;245:1042–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boiteux L.S., Fonseca M.E.N., Simon P.W. Effects of plant tissue and DNA purification method on randomly amplified polymorphic DNA-based genetic fingerprinting analysis in carrot. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1999;124:32–38. doi: 10.21273/JASHS.124.1.32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bowman M.J., Simon P.W. Quantification of the relative abundance of plastome to nuclear genome in leaf and root tissues of carrot (Daucus carota, L.) using quantitative PCR. Plant. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013;31:1040–1047. doi: 10.1007/s11105-012-0539-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schmidt A.H. Validation of a fast–HPLC method for the separation of iridoid glycosides to distinguish between the Harpagophytum species. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2005;28:2339–2347. doi: 10.1080/10826070500187525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mann H.B., Whitney D.R. On a Test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947;18:50–60. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177730491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ihlenfeldt H.-D. Pedaliaceae. In: Kadereit J.W., editor. The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants VII: Flowering Plants; Dicotyledons: Lamiales (except Acanthaceae including Avicenniaceae) Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2004. pp. 307–322. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gormley I.C., Bedigian D., Olmstead R.G. Phylogeny of Pedaliaceae and Martyniaceae and the placement of Trapella in Plantaginaceae s. l. Syst. Bot. 2015;40:259–268. doi: 10.1600/036364415X686558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen S., Yao H., Han J., Liu C., Song J., Shi L., Zhu Y., Ma X., Gao T., Pang X., et al. Validation of the ITS2 region as a novel DNA barcode for identifying medicinal plant species. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sang T., Crawford D.J., Stuessy T.F. Chloroplast DNA phylogeny, reticulate evolution, and biogeography of Paeonia (Paeoniaceae) Am. J. Bot. 1997;84:1120–1136. doi: 10.2307/2446155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lledo M.D., Crespo M.B., Cameron K.M., Fay M.F., Chase M.W. Systematics of Plumbaginaceae based upon cladistic analysis of rbcL sequence data. Syst. Bot. 1998;23:21–29. doi: 10.2307/2419571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Levin R.A., Wagner W.L., Hoch P.C., Nepokroeff M., Pires J.C., Zimmer E.A., Sytsma K.J. Family–level relationships of Onagraceae based on chloroplast rbcL and ndhF data. Am. J. Bot. 2003;90:107–115. doi: 10.3732/ajb.90.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fazekas A.J., Burgess K.S., Kesanakurti P.R., Graham S.W., Newmaster S.G., Husband B.C., Percy D.M., Hajibabaei M., Barrett S.C.H. Multiple multilocus DNA barcodes from the plastid genome discriminate plant species equally well. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Sequences were deposited in GenBank accessions KT717094–KT717184 and KY706348–KY706353.