Abstract

Africa has a high burden of tuberculosis, which is the most important risk factor for chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA). Our goal was to systematically evaluate the burden of CPA in Africa and map it by country. We conducted an extensive literature search for publications on CPA in Africa using the online databases. We reviewed a total of 41 studies published between 1976 and 2021, including a total of 1247 CPA cases from 14 African countries. Most of the cases came from Morocco (n = 764, 62.3%), followed by South Africa (n = 122, 9.9%) and Senegal (n = 99, 8.1%). Seventeen (41.5%) studies were retrospective, 12 (29.3%) were case reports, 5 case series (12.2%), 5 prospective cohorts, and 2 cross-sectional studies. The majority of the cases (67.1%, n = 645) were diagnosed in men, with a median age of 41 years (interquartile range: 36–45). Active/previously treated pulmonary tuberculosis (n = 764, 61.3%), human immunodeficiency virus infection (n = 29, 2.3%), diabetes mellitus (n = 19, 1.5%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 10, 0.8%) were the common co-morbidities. Haemoptysis was the most frequent presenting symptom, reported in up to 717 (57%) cases. Smoking (n = 69, 5.5%), recurrent lung infections (n = 41, 3%) and bronchorrhea (n = 33, 3%) were noted. This study confirms that CPA is common in Africa, with pulmonary tuberculosis being the most important risk factor.

Keywords: chronic pulmonary aspergillosis, Aspergillus, tuberculosis, Africa

1. Introduction

Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) is an uncommon, slowly progressive pulmonary disease, most commonly caused by Aspergillus fumigatus, which presents with prominent respiratory and systemic symptoms associated with significant morbidity and mortality [1,2]. The diagnosis of CPA requires a combination of characteristics: chest imaging evidence of one or more cavities with or without a fungal ball present or nodules on thoracic imaging, direct microscopy/histopathology evidence of Aspergillus infection or an immunological response to Aspergillus spp., compatible symptoms present for at least three months and exclusion of alternative diagnoses [3,4].

CPA is increasingly being recognised as a global public health problem [5], with an estimated three million people affected, particularly those with underlying structural lung disease such as tuberculosis (TB), sarcoidosis, previous atypical mycobacterial infection, emphysema or those who have experienced a previous pneumothorax [6,7]. Of these, current or previous pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) is the most common with prevalence ranging between 15% and 90% of patients with CPA [5,6]. CPA can mimic PTB and is often misdiagnosed, occurs during treatment of active PTB, or most often complicates PTB, especially in patients left with residual cavities [5,8].

Despite the high mortality associated with untreated CPA, that is, a 1-year mortality of ~20% and a 5-year mortality of ~75% [2,9], it is not currently considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) [10] since its burden is not well described. Africa has a high burden of TB and is therefore likely to have a high burden of CPA, but there are limited epidemiological studies to support this claim. Therefore, this study aimed to systematically review published cases of CPA and map its burden by country to inform policy, clinical care, and public health strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We conducted this systematic review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis [11]. All databases were searched from inception to 31 July 2021.

2.2. Search Strategy

With the help of an experienced medical librarian, a comprehensive literature search was performed for publications on CPA cases or series in Africa using online databases Medline (via PubMed), Embase, African Journals Online, Google Scholar and gray literature papers. The search engine used the key words and the detailed medical subject heading (MeSH) terms to identify all published papers: “chronic pulmonary aspergillosis,” “CPA,” “pulmonary aspergilloma,” “post-tuberculosis lung disease,” “pulmonary mycetoma,” “Africa,” or the individual names of each of the country in Africa. The Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were used to combine 2 or 3 terms.

2.3. Selection Criteria

We included all published studies, including case reports, case series, epidemiological and other observational study designs reporting on primary data from across Africa. We did not apply any language restriction. No date limitation or any other search criteria were applied to avoid missing papers published in Africa.

We excluded review articles and cases with grossly missing data, such as demographic characteristic and how the diagnosis of CPA was made.

2.4. Data Extraction

Data on study authors, study location (country and region in Africa), study period, age, sex, clinical presentation, underlying comorbidities, or risk factors were extracted. Data extraction was performed independently by two authors (RO and IIO) and any discrepancies solved by discussions.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 365 and STATA 16.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). Categorical characteristics of studies (e.g., country, study design, gender) were summarised as frequencies and percentages. Age from respective studies was summarised as median and interquartile range. Individual cases of CPA were summed up to give an overall number of patients diagnosed with CPA in Africa. CPA cases were stratified by country, region, and sex.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

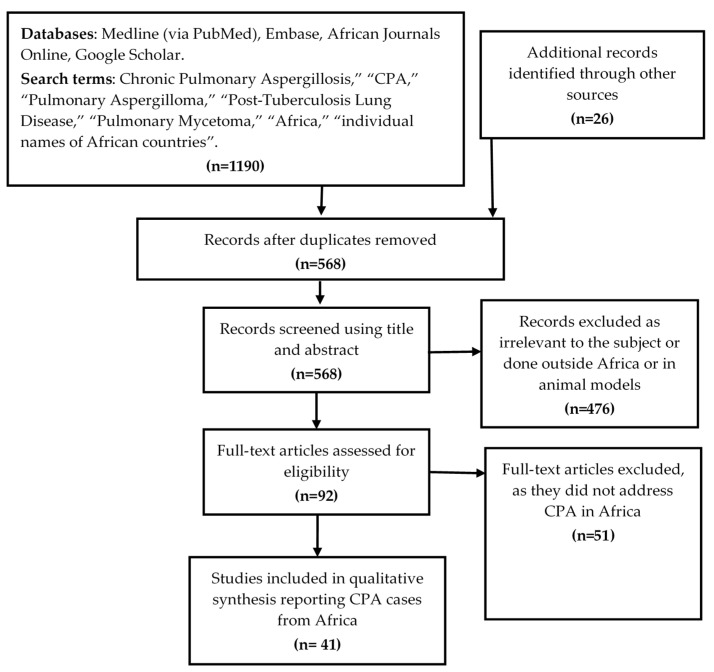

Our initial database search retrieved 1190 publications and 26 identified from references of eligible studies. We then removed duplicates and 568 citations remained from which relevant studies were selected for review. Their potential relevance was examined using a title and abstract screening to remove studies that were clearly not related to scope of this review. A total of 476 citations were excluded as irrelevant to the subject. The full papers of the remaining 92 citations were assessed to select those that included primary data about CPA cases in any African country. These criteria excluded 51 studies and left 41 studies that were included in the final analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Citation selection process for the systematic review. Forty-one articles were found describing CPA cases in Africa.

3.2. Summary of Studies

We reviewed a total of 41 studies reporting CPA in 14 of the 54 African countries. (Table 1). Seventeen (41.5%) studies were retrospective chart reviews [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], 12 (29.3%) were case reports [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40], 5 case series (12.2%) [8,41,42,43,44], 5 prospective cohorts [45,46,47,48,49], and 2 cross-sectional studies [50,51]. The majority of the studies were from East (n = 11) and West (n = 10) Africa. All studies were conducted between 1972 to 2019 and published between 1976 to 2021. Table 2 summarises the characteristics of the studies included in the review.

Table 1.

Distribution of the studies included in the review.

| Country | Region | Number of Publications | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morocco [13,16,18,23,26,37,38,41] | North Africa | 8 | 19.5 |

| South Africa [15,22,27,35,47,48,49] | Southern Africa | 7 | 17.1 |

| Nigeria [14,28,32,34,50] | West Africa | 5 | 12.2 |

| Senegal [17,19,25,44] | West Africa | 4 | 9.8 |

| Uganda [8,29,30,51] | East Africa | 4 | 9.8 |

| Ethiopia [12,20,39] | East Africa | 3 | 7.3 |

| Cameroon [31,45] | Central Africa | 2 | 4.9 |

| Tanzania [24,36] | East Africa | 2 | 4.9 |

| Egypt [21] | North Africa | 1 | 2.4 |

| Ghana [33] | West Africa | 1 | 2.4 |

| Madagascar [46] | East Africa | 1 | 2.4 |

| Mozambique/Somalia [43] | East Africa | 1 | 2.4 |

| Somalia [42] | East Africa | 1 | 2.4 |

| Sudan [40] | North Africa | 1 | 2.4 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies reviewed.

| Study Type | Country | Region | Study Period | CPA Cases | Mean Age (Years) | Male: n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kwizera et al. (2021) [8] | Case Series | Uganda | East Africa | - | 3 | 38.7 | 0 (0) |

| Alemu et al. (2020) [12] | Retrospective | Ethiopia | East Africa | 2014–2019 | 72 | 35.2 | 46 (63.9) |

| Kwizera et al. (2020) [29] | Case Report | Uganda | East Africa | - | 1 | 40.0 | 0 (0) |

| Harmouchi et al. (2019) [13] | Retrospective | Morocco | North Africa | 2009–2018 | 79 | 40.5 | 57 (72.2) |

| Bongomin et al. (2019) [30] | Case Report | Uganda | East Africa | 2018 | 1 | 45.0 | 1 (100) |

| Nonga et al. (2018) [31] | Case Report | Cameroon | Central Africa | - | 1 | 47.0 | 1 (100) |

| Nonga et al. (2018) [45] | Prospective | Cameroon | Central Africa | 2012–2015 | 20 | 30.0 | 17 (85) |

| Gbaja-Biamila et al. (2018) [32] | Case Report | Nigeria | West Africa | 2016 | 1 | 35.0 | 1 (100) |

| Salami et al. (2018) [14] | Retrospective | Nigeria | West Africa | 2014–2017 | 2 | 32.0 | 1 (50) |

| Masoud et al. (2017) [15] | Retrospective | South Africa | Southern Africa | 2013–2015 | 59 | 46.6 | 36 (61) |

| Oladele et al. (2017) [50] | Cross sectional | Nigeria | West Africa | 2014–2015 | 18 | - | - |

| Page et al. (2019) [51] | Cross sectional | Uganda | East Africa | 2012–2013 | 18 | - | 11 (80.0) |

| Issoufoua et al. (2016) [41] | Case Series | Morocco | North Africa | 2009–2014 | 6 | 38.8 | - |

| Ofori et al. (2016) [33] | Case Report | Ghana | West Africa | 2013 | 1 | 38.0 | 1 (100) |

| Ekwueme et al. (2016) [34] | Case Report | Nigeria | West Africa | - | 1 | 56.0 | 0 (0) |

| Hammoumi et al. (2015) [16] | Retrospective | Morocco | North Africa | 2006–2014 | 274 | 37.8 | 93 (33.9) |

| Ba et al. (2015) [17] | Retrospective | Senegal | West Africa | 2004–2008 | 35 | 43.4 | 28 (80) |

| Benjelloun et al. (2015) [18] | Retrospective | Morocco | West Africa | 2003–2014 | 81 | 51.0 | 48 (59.3) |

| Koegelenberg et al. (2014) [35] | Case Report | South Africa | Southern Africa | - | 1 | 30.0 | 1 (100) |

| Pohl et al. (2013) [36] | Case Report | Tanzania | East Africa | 2011 | 1 | 68.0 | 1 (100) |

| Hammoumi et al. (2013) [37] | Case Report | Morocco | North Africa | - | 3 | 47.7 | 3 (100) |

| Ade et al. (2011) [19] | Retrospective | Senegal | West Africa | 2004–2008 | 35 | 43.4 | 28 (80) |

| Rakotoson et al. (2011) [46] | Prospective | Madagascar | East Africa | 2006–2010 | 37 | 43.0 | 29 (78.4) |

| Smahi et al. (2011) [38] | Case Report | Morocco | North Africa | 1991–2000 | 1 | 60.0 | 1 (100) |

| Gross et al. (2009) [47] | Prospective | South Africa | Southern Africa | - | 10 | 41.4 | - |

| Bekele et al. (2009) [20] | Retrospective | Ethiopia | East Africa | 2005–2008 | 11 | 38.9 | 9 (81.8) |

| Brik et al. (2008) [21] | Retrospective | Egypt | North Africa | 2001–2008 | 42 | 44.0 | 28 (66.7) |

| van den Heuvel et al. (2007) [22] | Retrospective | South Africa | Southern Africa | 2001–2003 | 13 | - | - |

| Hassan et al. (2004a) [42] | Case Series | Somalia | East Africa | 2000–2003 | 1 | - | - |

| Corr (2006) [48] | Prospective | South Africa | Southern Africa | 2002–2003 | 12 | 36.0 | 9 (75) |

| Caidi et al. (2006) * [23] | Retrospective | Morocco | North Africa | 1982–2004 | 320 | 32.0 | 161 (57.9) |

| Hassan et al. (2004b) [43] | Case Series | Mozambique /Somalia | East Africa | - | 8 | 30.0 | 6 (75) |

| Falkson et al. (2002) [49] | Prospective | South Africa | Southern Africa | 1989–1994 | 5 | 45.0 | 5 (100) |

| Mbembati et al. (2001) [24] | Retrospective | Tanzania | East Africa | 1986–2000 | 10 | - | 8 (80) |

| Ba et al. (2000) [25] | Retrospective | Senegal | West Africa | 1991–1998 | 24 | - | - |

| Kabiri et al. (1999) * [26] | Retrospective | Morocco | North Africa | 1982–1998 | - | - | - |

| Aderaye et al. (1996) [39] | Case Report | Ethiopia | East Africa | - | 1 | 25.0 | 0 (0) |

| Conlan et al. (1987) [27] | Retrospective | South Africa | Southern Africa | 1982–1984 | 22 | - | 7 (31.8) |

| Adebayo et al. (1984) [28] | Retrospective | Nigeria | West Africa | 1977–1983 | 11 | 42.2 | 7 (63.6) |

| Kane et al. (1976) [44] | Case Series | Senegal | West Africa | - | 5 | - | - |

| Mahgoub et al. (1972) [40] | Case Report | Sudan | North Africa | 1968–1971 | 1 | 45.0 | 1 (100) |

3.3. Cases of CPA in Africa

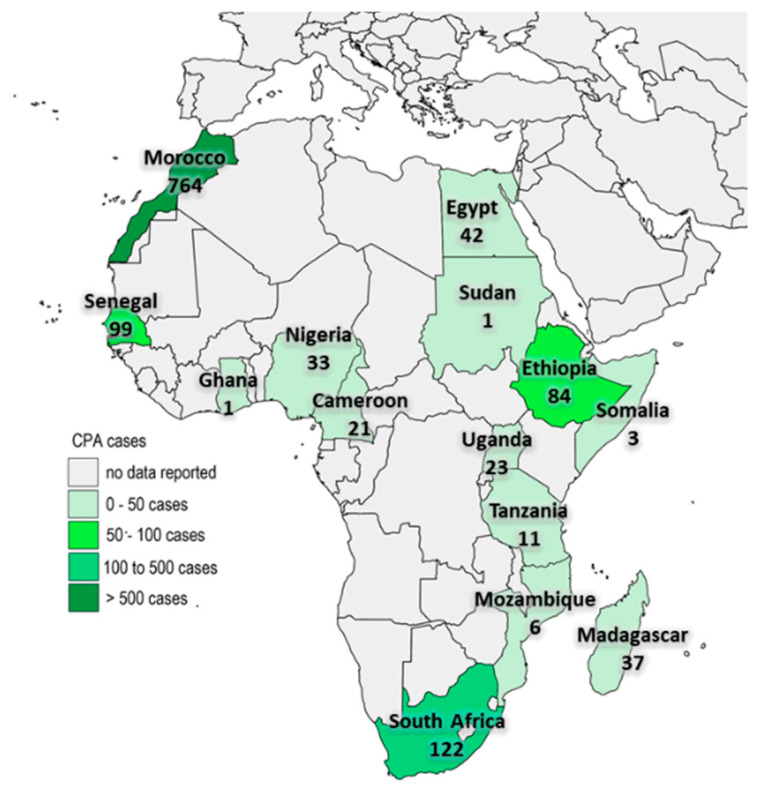

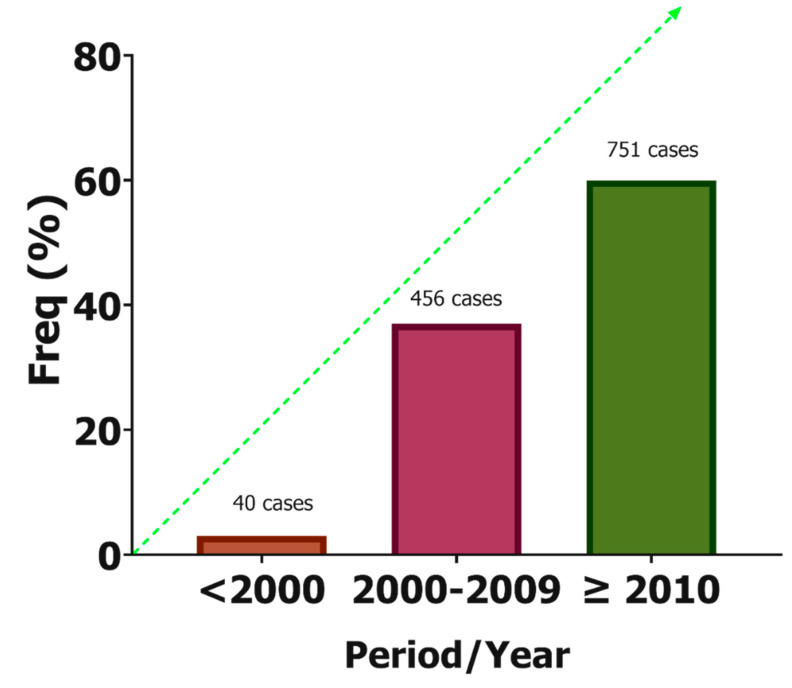

During the period of the review, 1247 cases of CPA were reported in Africa. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the reported cases in Africa. About one-third (67.1%, n = 645) were men and the median age was 41 years (interquartile range: 36–45 years). The majority of the reported cases were from Morocco (n = 764, 62.3%), followed by South Africa (n = 122, 9.9%) and Senegal (n = 99, 8.1%). When stratified by year of publication (≤1999, 2000–2009, and ≥2010), there has been an increase in the number of CPA reported in the literature over the past five decades (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

A map of Africa showing the distribution of CPA cases.

Figure 3.

Trends in the report of CPA cases in Africa.

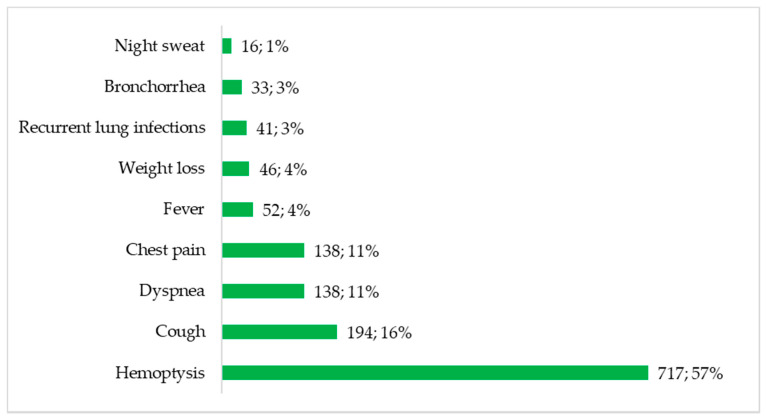

Figure 4 summarises the presenting complaints documented in the eligible studies. Haemoptysis was the most frequent presenting symptom/complaint, reported in up to 717 cases (57%). Cough (16%), difficulty in breathing (11%) and chest pain (11%) were also common symptoms. Recurrent lung infections (n = 41, 3%) and bronchorrhea (n = 33, 3%) were also noted.

Figure 4.

Presenting complaints of patients with CPA in Africa.

3.4. Underlying Comorbidities

The most frequent underlying risk factors were active/previous tuberculosis (n = 764, 61.3%), smoking (n = 69, 5.5%) and HIV (n = 29, 2.3%). In fact, CPA was misdiagnosed as tuberculosis in two studies [8,32]. Other common comorbidities included bronchiectasis (n = 48, 3.8%), hydatid cysts (n = 19, 1.5%), diabetes mellitus (n = 19, 1.5%), lung abscess (n = 16, 1.3%), and COPD (n = 10, 0.8%). Pulmonary fibrosis (n = 1) [27] and lung malignancies (n = 2) [38,46] were infrequently reported.

4. Discussion

We present the first comprehensive attempt to enumerate all published CPA cases in Africa. Over 1200 CPA cases have been published over a 45-year period, with over 93% of the cases published after 2003—the year Denning and colleagues first described a set of diagnostic criteria for CPA [1]. In previous estimates of the burden of CPA, Agarwal and colleagues reported an annual incidence of CPA that varied between 27,000 and 0.17 million cases in the Indian sub-continent [52]. In addition, the global burden of CPA as a consequence of treated PTB has been estimated at 1.2 million cases [53] and approximately 72,000 cases as a sequela of sarcoidosis [54].

PTB was the most frequent underlying disease among the published cases. This is consistent with previously published cases from the rest of the world [6,9,55]. PTB and CPA share several important features—both being progressive parenchymal diseases with overlapping risk factors, symptoms and radiological findings that often lead to misdiagnosis of both disease [5,8,56]. In fact, in most low- and middle-income countries where the index of clinical suspicion and diagnostic capabilities are still low, CPA is managed as smear negative-TB.

Most CPA cases experienced haemoptysis and cough, which are also common symptoms in patients with PTB. This could explain why misdiagnosis for PTB was also common among these patients. The African patients were young and mostly men, findings which are consistent with reports from the United Kingdom [1], Europe [57], and Asia [55,58,59]. Therefore, across the world, CPA predominantly affects middle-aged men in the prime of their lives, and this is likely to have a negative impact on the global economy.

Recently, there has been tremendous advances in the diagnostics horizon for CPA, particularly the development of the Aspergillus IgG/IgM lateral flow assay for the serological diagnosis of CPA [60,61]. This has revolutionised the diagnosis of CPA in some low- and middle-income countries like Uganda [29], Mozambique [62] and Indonesia [63]. However, access to essential diagnostics for most fungal diseases and CPA in particular remains a challenge in many countries across Africa [64]. This could explain why only 14 of the 54 countries in Africa reported at least 1 case of CPA. The Global Action Fund for Fungal Infections (GAFFI) working together with its ambassadors globally, continues to advocate for increased access to and availability of essential diagnostics and drugs for major fungal diseases [65,66].

In this report, the prevalence of HIV infection (2.3%), and diabetes mellitus (1.5%) were both low. HIV does not appear to increase the predisposition to or prevalence of CPA among patients with active TB or those previously treated for TB in Africa [32,51]. Whether or not diabetes mellitus influences the incidence or prevalence of CPA in Africa remains unknown. In a recent study from Indonesia, 30% of patients with CPA had diabetes mellitus and patients with diabetes mellitus had a 6.7-fold the risk of developing CPA compared to non-diabetic populations [64]. Diabetes mellitus and HIV are also independent risk factors for sub-acute invasive aspergillosis and invasive aspergillosis which have poorer prognosis compared to CPA [67,68,69].

Untreated CPA can lead to progressive pulmonary fibrosis [70], progressive symptoms such as haemoptysis which may lead to high mortality [2], and a significant deterioration in the quality of life of those affected [71]. Early diagnosis of CPA, would allow an early start of antifungal treatment, usually given for at least 6 months, typically with oral itraconazole or voriconazole [3]. Follow up of TB patients for development of CPA is advocated and surveillance for CPA using point of care test should be built into the national TB control programmes for each African country to encourage early diagnosis and treatment [33].

Through advocacy by GAFFI, the point of care Aspergillus lateral flow assay was added to the WHO essential diagnostics list and should be able to help ease diagnosis of CPA in resource limited settings [66]. Oral itraconazole, the preferred antifungal for CPA, is available in at least 43% of African countries, but costly [72]. The cost varies widely from less than $1 in Uganda to $19 in Nigeria for a 400 mg/day dose. However, the WHO also recently added itraconazole on the “2017 Model List of Essential Medicines” for adults for management of selected fungal infections [73]. These efforts could reduce the cost of the diagnostics and treatment so thus encouraging screening and treatment programmes complemented with research studies in TB endemic areas.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we report substantial cases of CPA in Africa, especially in patients with currently active or previously treated PTB. Most of the patients are young and men. Therefore, CPA is an important, yet neglected disease that is significantly affecting economically dynamic people in Africa. Future research should focus on active screening for CPA in the most vulnerable populations.

Author Contributions

F.B. conceived the manuscript. R.O. and I.I.O. data abstraction. R.O. analysed the data. F.B., R.O., I.I.O., J.B.B., J.S., R.K. and F.B. participated in initial manuscript drafting. All authors participated in critical revisions for intellectual content and material support. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This is a secondary analysis of published literature and did not deal with individual patient data. Therefore, approval by a regulatory or ethics committee was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Denning D.W., Riniotis K., Dobrashian R., Sambatakou H. Chronic cavitary and fibrosing pulmonary and pleural aspergillosis: Case series, proposed nomenclature change, and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003;37:S265–S280. doi: 10.1086/376526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowes D., Al-Shair K., Newton P.J., Morris J., Harris C., Rautemaa-Richardson R., Denning D.W. Predictors of mortality in chronic pul-monary aspergillosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2017;49:1601062. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01062-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denning D.W., Cadranel J., Beigelman-Aubry C., Ader F., Chakrabarti A., Blot S., Ullmann A.J., Dimopoulos G., Lange C. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: Rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management. Eur. Respir. J. 2015;47:45–68. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00583-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denning D.W., Page I., Chakaya J., Jabeen K., Jude C.M., Cornet M., Alastruey-Izquierdo A., Bongomin F., Bowyer P., Chakrabarti A., et al. Case definition of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in resource-constrained settings. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018;24:e171312. doi: 10.3201/eid2408.171312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bongomin F. Post-tuberculosis chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: An emerging public health concern. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008742. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith N.L., Denning D.W. Underlying conditions in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis including simple aspergilloma. Eur. Respir. J. 2010;37:865–872. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00054810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bongomin F., Gago S., Oladele R.O., Denning D.W. Global and multi-national prevalence of fungal diseases—estimate precision. J. Fungi. 2017;3:57. doi: 10.3390/jof3040057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwizera R., Katende A., Bongomin F., Nakiyingi L., Kirenga B.J. Misdiagnosis of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis as pulmonary tuberculosis at a tertiary care center in Uganda: A case series. J. Med. Case Rep. 2021;15:140. doi: 10.1186/s13256-021-02721-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohba H., Miwa S., Shirai M., Kanai M., Eifuku T., Suda T., Hayakawa H., Chida K. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Respir. Med. 2012;106:724–729. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hay R., Denning D.W., Bonifaz A., Queiroz-Telles F., Beer K., Bustamante B., Chakrabarti A., Chavez-Lopez M.D.G., Chiller T., Cornet M., et al. The diagnosis of fungal neglected tropical diseases (fungal NTDs) and the role of investigation and laboratory tests: An expert consensus report. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019;4:122. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed4040122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D., PRISMA-P Group. Shamseer L., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., Shekelle P., Stewart L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alemu B.N. Surgical outcome of chronic pulmonary aspergilloma: An experience from two tertiary referral hos-pitals in addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2020;30:521–530. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v30i4.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harmouchi H., Lakranbi M., Issoufou I., Ouadnouni Y., Smahi M. Pulmonary aspergilloma: Surgical outcome of 79 patients in a Moroccan center. Asian Cardiovasc. Thorac. Ann. 2019;27:476–480. doi: 10.1177/0218492319855492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salami M.A., Sanusi A.A., Adegboye V.O. Current indications and outcome of pulmonary resections for tuberculosis complications in Ibadan, Nigeria. Med. Princ. Pract. 2017;27:80–85. doi: 10.1159/000485382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masoud S., Irusen E., Koegelenberg C., Du Preez L., Allwood B. Outcomes of resectable pulmonary aspergilloma and the per-formance gap in a high tuberculosis prevalence setting: A retrospective study. Afr. J. Thorac. Crit. Care Med. 2017;23:8–13. [Google Scholar]

- 16.El Hammoumi M.M., Slaoui O., El Oueriachi F., Kabiri E.H. Lung resection in pulmonary aspergilloma: Experience of a Moroccan center vascular and thoracic surgery. BMC Surg. 2015;15:114. doi: 10.1186/s12893-015-0103-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ba P., Ndiaye A.R., Diatta S., Ciss A., Dieng P., Gaye M., Fall M., Ndiaye M. Results of surgical treatment for pulmonary aspergilloma. Med. Sante Trop. 2015;25:92–96. doi: 10.1684/mst.2014.0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benjelloun H., Zaghba N., Yassine N., Bakhatar A., Karkouri M., Ridai M., Bahlaoui A. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: A frequent and potentially severe disease. Méd. Mal. Infect. 2015;45:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ade S.S., Touré N.O., Ndiaye A., Diarra O., Dia Kane Y., Diatta A., Ndiayeb M., Hanea A.A. Aspects épidémiologiques, cliniques, thérapeutiques et évolutifs de l’aspergillome pulmonaire à Dakar. Rev. Mal. Respir. 2011;28:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2010.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bekele A., Gulilat D., Kassa S., Ali A. Aspergilloma of the lungs: Operative experience from Tikur Anbessa Hospital, Ethiopia. East Cent. Afr. J. Surg. 2009;14:44–49. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brik A., Salem A.M., Kamal A.R., Abdel-Sadek M., Essa M., El Sharawy M., Deebes A., Bary K.A. Surgical outcome of pulmonary aspergilloma. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2008;34:882–885. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Den Heuvel M.M., Els Z., Koegelenberg C.F., Naidu K.M., Bolliger C.T., Diacon A.H. Risk factors for recurrence of haemoptysis following bronchial artery embolisation for life-threatening haemoptysis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2007;11:909–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caidi M., Kabiri H., Al Aziz S., El Maslout A., Benosman A. Chirurgie des aspergillomes pulmonaires. La Presse Med. 2006;35:1819–1824. doi: 10.1016/S0755-4982(06)74907-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mbembati N.A.A., Lema L.E.K. Pulmonary aspergilloma: A 15 years experience in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. [(accessed on 17 September 2021)];East Cent. Afr. J. Surg. 2001 6 Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ecajs/article/view/136632. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ba M., Ciss G., Diarra O., Kane O., Ndiaye M. Surgical aspects of pulmonary aspergilloma in 24 patients. Dakar Med. 2000;45:144–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kabiri E.H., Lahlou K., Achir A., Al Aziz S., El Meslout A., Benosman A. Les aspergillomes pulmonaires: Résultats du traitement chirurgical. À propos d’une série de 206 cas. Chirurgie. 1999;124:655–660. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4001(99)00077-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conlan A., Abramor E., Moyes D.G. Pulmonary aspergilloma-indications for surgical intervention. An analysis of 22 cases. S. Afr. Med. J. 1987;71:285–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adeyemo A.O., Odelowo E.O., Makanjuola D.I. Management of pulmonary aspergilloma in the presence of active tuberculosis. Thorax. 1984;39:862–867. doi: 10.1136/thx.39.11.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwizera R., Katende A., Teu A., Apolot D., Worodria W., Kirenga B.J., Bongomin F. Algorithm-aided diagnosis of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in low- and middle-income countries by use of a lateral flow device. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019;39:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03782-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bongomin F., Kwizera R., Atukunda A., Kirenga B.J. Cor pulmonale complicating chronic pulmonary aspergillosis with fatal consequences: Experience from Uganda. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2019;25:22–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nonga B.N., Jemea B., Pondy A.O., Handy Eone D., Bitchong M.C., Fola O., Nkolaka A., Londji G.M. Unusual Life-Threatening Pneumothorax Com-plicating a Ruptured Complex Aspergilloma in an Immunocompetent Patient in Cameroon. Case Rep. Surg. 2018;2018:8648732. doi: 10.1155/2018/8648732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gbaja-Biamila T., Bongomin F., Irurhe N., Nwosu A., Oladele R. Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis Misdiagnosed as Smear-Negative Pulmonary Tuberculosis in a TB Clinic in Nigeria. J. Adv. Med. Med. Res. 2018;26:41816. doi: 10.9734/JAMMR/2018/41816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ofori A., Steinmetz A.R., Akaasi J., Frimpong G.A., Norman B.R., Obeng-Baah J., Bedu-Addo G., Phillips R.O. Pulmonary aspergilloma: An evasive disease. Int. J. Mycobacteriol. 2016;5:235–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmyco.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ekwueme C., Otu A.A., Chinenye S., Unachukwu C., Oputa R.N., Korubo I., Enang O.E. Haemoptysis in a female with diabetes mellitus: A unique presentation of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis, pulmonary tuberculosis, and Klebsiella peumoniae co-infection. Clin. Case Rep. 2016;4:432–436. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koegelenberg C.F., Bruwer J.W., Bolliger C.T. Endobronchial valves in the management of recurrent haemoptysis. Respiration. 2014;87:84–88. doi: 10.1159/000355198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pohl C., Jugheli L., Haraka F., Mfinanga E., Said K., Reither K. Pulmonary aspergilloma: A treatment challenge in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013;7:e2352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El Hammoumi M., Traibi A., El Oueriachi F., Arsalane A., Kabiri E. Surgical treatment of aspergilloma grafted in hydatid cyst cavity. Rev. Port. Pneumol. 2013;19:281–283. doi: 10.1016/j.rppneu.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smahi M., Serraj M., Ouadnouni Y., Chbani L., Znati K., Amarti A. Aspergilloma in combination with adenocarcinoma of the lung. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2011;9:27. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aderaye G., Jajaw A. Bilateral pulmonary aspergilloma: Case report. East Afr. Med. J. 1996;73:487–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahgoub E.S., El Hassan A.M. Pulmonary aspergillosis caused by Aspergillus flavus. Thorax. 1972;27:33–37. doi: 10.1136/thx.27.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Issoufou I., Sani R., Belliraj L., Ammor F.Z., Moussa Ounteini A., Ghalimi J., Lakranbi M., Ouadnouni Y., Smahi M. Pneumonectomie pour poumon détruit post-tuberculeux: Une série de 26 cas opérés. Rev. Pneumol. Clin. 2016;72:288–292. doi: 10.1016/j.pneumo.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hassan M.Y., Hospital M., Elmi M.-S.A.M., Surgeon S., Baldan M.-S.M. Experience of Thoracic Surgery Performed Under Difficult Conditions in Somalia. Introduction Patients and Methods. [(accessed on 17 September 2021)];East Cent. Afr. J. Surg. 2004 9 Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ecajs/article/view/137294. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hassan M.Y., Baldan M. Aspergillus of the Lung with Haemoptysis: A surgical emergency. East Cent. Afr. J. Surg. 2004;9:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kane P.A., Sarr A.M., Courbil J.L., Derrien J.C., Coly D., Diop B., Nadio A., Sankalé M. Pulmonary aspergillosis. The 1st case in Dakar. Bull. Soc. Med. Afr. Noire Lang. Fr. 1976;21:157–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ngo Nonga B., Bang G.A., Jemea B., Savom E., Yone P., Mbatchou N., Ze J.J. Complex Pulmonary Aspergilloma: Surgical Challenges in a Third World Setting. Surg. Res. Pract. 2018;2018:6570741. doi: 10.1155/2018/6570741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rakotoson J.L., Razafindramaro N., Rakotomizao J.R., Vololontiana H.M.D., Andrianasolo R.L., Ravahatra K., Tiaray M., Rajaoarifetra J., Rakotoharivelo H., Andrianarisoa A.C.F. Les aspergillomes pulmonaires: À propos de 37 cas à Nadagascar. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2011;10:1–7. doi: 10.4314/pamj.v10i0.72209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gross A.M., Diacon A.H., Heuvel M.M.V.D., Van Rensburg J., Harris D., Bolliger C.T. Management of life-threatening haemoptysis in an area of high tuberculosis incidence. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2009;13:875–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corr P. Management of severe hemoptysis from pulmonary aspergilloma using endovascular embolization. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2006;29:807–810. doi: 10.1007/s00270-005-0329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Falkson C., Sur R., Pacella J. External beam radiotherapy: A treatment option for massive haemoptysis caused by mycetoma. Clin. Oncol. 2002;14:233–235. doi: 10.1053/clon.2002.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oladele R.O., Irurhe N.K., Foden P., Akanmu A.S., Gbaja-Biamila T., Nwosu A., Ekundayo H.A., Ogunsola F.T., Richardson M.D., Denning D.W. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis as a cause of smear-negative TB and/or TB treatment failure in Nigerians. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2017;21:1056–1061. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.17.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Page I.D., Byanyima R., Hosmane S., Onyachi N., Opira C., Richardson M., Sawyer R., Sharman A., Denning D.W. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis commonly complicates treated pulmonary tuberculosis with residual cavitation. Eur. Respir. J. 2019;53:1801184. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01184-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agarwal R., Denning D., Chakrabarti A. Estimation of the burden of chronic and allergic pulmonary aspergillosis in India. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e114745. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Denning D.W., Pleuvry A., Cole D. Global burden of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis as a sequel to pulmonary tuberculosis. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011;89:864–872. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.089441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Denning D.W., Pleuvry A., Cole D. Global burden of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis complicating sarcoidosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2012;41:621–626. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00226911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jhun B.W., Jung W.J., Hwang N.Y., Park H.Y., Jeon K., Kang E.S., Koh W.G. Risk factors for the development of chronic pulmonary as-pergillosis in patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0188716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baluku J.B., Nuwagira E., Bongomin F., Denning D.W. Pulmonary TB and chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: Clinical differences and similarities. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2021;25:537–546. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.21.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cadranel J., Philippe B., Hennequin C., Bergeron A., Bergot E., Bourdin A., Cottin V., Jeanfaivre T., Godet C., Pineau M., et al. Voriconazole for chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: A prospective multicenter trial. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012;31:3231–3239. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1690-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Agarwal R., Vishwanath G., Aggarwal A.N., Garg M., Gupta D., Chakrabarti A. Itraconazole in chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis: A randomised controlled trial and systematic review of literature. Mycoses. 2013;56:559–570. doi: 10.1111/myc.12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Izumikawa K., Ohtsu Y., Kawabata M., Takaya H., Miyamoto A., Sakamoto S., Kishi K., Tsuboi E., Homma S., Yoshimura K. Clinical efficacy of micafungin for chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Sabouraudia. 2007;45:273–278. doi: 10.1080/13693780701278386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Denning D.W. Diagnosing pulmonary aspergillosis is much easier than it used to be: A new diagnostic landscape. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2021;25:525–536. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.21.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hunter E.S., Richardson M.D., Denning D.W. Evaluation of LDBio aspergillus ICT lateral flow assay for IgG and IgM antibody detection in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019;57:e00538-19. doi: 10.1128/jcm.00538-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salzer H.J.F., Massango I., Bhatt N., Machonisse E., Reimann M., Heldt S., Lange C., Hoelscher M., Khosa C., Rachow A. Seroprevalence of aspergillus-specific IgG antibody among mozambican tuberculosis patients. J. Fungi. 2021;7:595. doi: 10.3390/jof7080595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rozaliyani A., Rosianawati H., Handayani D., Agustin H., Zaini J., Syam R., Adawiyah R., Tugiran M., Setianingrum F., Burhan E., et al. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in post tuberculosis patients in indonesia and the role of LDBio aspergillus ICT as part of the diagnosis scheme. J. Fungi. 2020;6:318. doi: 10.3390/jof6040318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Orefuwa E., Gangneux J.P., Denning D.W. The challenge of access to refined fungal diagnosis: An investment case for low- and middle-income countries. J. Med. Mycol. 2021;31:101140. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2021.101140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Denning D.W. The ambitious ’95-95 by 2025’ roadmap for the diagnosis and management of fungal diseases. Thorax. 2015;70:613–614. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bongomin F., Govender N.P., Chakrabarti A., Robert-Gangneux F., Boulware D., Zafar A., Oladele R.O., Richardson M.D., Gangneux J.-P., Alastruey-Izquierdo A., et al. Essential in vitro diagnostics for advanced HIV and serious fungal diseases: International experts’ consensus recommendations. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019;38:1581–1584. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03600-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kosmidis C., Denning D.W. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Thorax. 2014;70:270–277. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gao Y., Soubani A. Advances in the diagnosis and management of pulmonary aspergillosis. Adv. Respir. Med. 2020;87:231–243. doi: 10.5603/ARM.2019.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kousha M., Tadi R., Soubani A.O. Pulmonary aspergillosis: A clinical review. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2011;20:156–174. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00001011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kosmidis C., Newton P., Muldoon E.G., Denning D.W. Chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis: A cause of ‘destroyed lung’ syndrome. Infect. Dis. 2016;49:296–301. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2016.1232861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bongomin F., Otu A. Utility of St. George’s respiratory questionnaire in predicting clinical recurrence in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2021;8:204993612110346. doi: 10.1177/20499361211034643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kneale M., Bartholomew J.S., Davies E., Denning D.W. Global access to antifungal therapy and its variable cost. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016;71:3599–3606. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.World Health Organization . WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, 20th List (March 2017, Amended August 2017) World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2017. [(accessed on 17 September 2021)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/eml-20. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.