Abstract

Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii lives in association with certain species of eucalyptus trees and is a causative agent of cryptococcosis. It exists as two mating types, MATα and MATa, which is determined by a single-locus, two-allele system. In the closely related C. neoformans var. neoformans, the α mating type has been found to outnumber its a counterpart by at least 30:1, but there have been very limited data on the proportions of each mating type in C. neoformans var. gattii. In the present study, specific PCR primers were designed to amplify two separate α-mating-type genes from C. neoformans var. gattii strains. These were used to survey for the presence of the two mating types in clinical and environmental collections of C. neoformans var. gattii strains from Australia. Sixty-eight of 69 clinical isolates produced both α mating type-specific bands and were assumed to be of the α mating type. The majority of environmental isolates were also of the α mating type, but the a mating type was located in two separate areas. In one area, the a mating type outnumbered the α mating type by 27:2, but in the second area, the ratio of the two mating types was close to the 50:50 ratio expected for sexual recombination.

Cryptococcus neoformans is an encapsulated, basidiomycetous yeast and is the causative agent of cryptococcosis, a rare but potentially serious disease of humans and animals (5). Two varieties of C. neoformans exist, and these differ biochemically, genetically, ecologically, and epidemiologically (13). C. neoformans var. neoformans has a worldwide distribution and has been associated with a variety of environmental sources, in particular, bird excreta (8) and decaying wood, forming hollows in a number of tree species (18). C. neoformans var. gattii has a more restricted global distribution, occurring in tropical and subtropical climates. Since 1989, C. neoformans var. gattii has been shown to have a specific ecological association with a number of eucalyptus species; Eucalyptus camaldulensis (river red gum), Eucalyptus tereticornis (forest red gum), Eucalyptus rudis (West Australian flooded gum), Eucalyptus gomphocephala (tuart) (4, 21, 22), Eucalyptus grandis (flooded gum), Eucalyptus blakelyi (Blakely’s red gum), and Angophora costata (smooth-barked apple) (unpublished data). These trees are native to Australia, where a relatively high incidence of cryptococcosis due to C. neoformans var. gattii occurs in some native animals and indigenous human populations (6). They have also been exported to other tropical parts of the world, and C. neoformans var. gattii infections are also found in these regions (4). However, the role that the tree plays in the life cycle of this fungus and the nature of the infectious propagule are not well understood. Viable C. neoformans var. gattii cells have been found in the woody debris and detritus associated with the Eucalyptus species, and there appears to be a correlation between the flowering of the trees and the dispersal of the fungus (3). However, it is not known whether the fungus completes its life cycle on the tree to be shed as basidiospores or whether it propagates asexually and disperses as desiccated yeast cells. Basidiospores are favored as the infectious propagule, as they are small (<2 μm), can penetrate into the lung alveoli, and are more resistant to desiccation than yeast cells (13).

C. neoformans exists as two mating types, mating types α and a, with the mating type determined by a single locus with two idiomorphic alleles (10). In laboratory crosses, equal numbers of offspring of the a and α mating types are produced (10). However, surveys of C. neoformans var. neoformans isolates from clinical and environmental sources have shown that the α mating type outnumbers its a counterpart by ratios of 30:1 and 40:1, respectively (12, 19). In addition, population genetic studies of C. neoformans var. neoformans have indicated a clonal structure which may either influence or be influenced by this imbalance of mating types (7). The limited data available for C. neoformans var. gattii isolates found 84% of the clinical isolates to be of the α mating type, but no data are available for the mating type frequencies of C. neoformans var. gattii isolates in the environment (19).

C. neoformans var. neoformans strains of the α mating type have been associated with increased virulence in mice, which has prompted studies into the mating type locus (MATα) (15). Molecular studies have estimated MATα to be at least 75 kb in size (30). Within this locus, two α-mating-type genes have been identified: MFα and STE12α. The MFα gene contains a 114-bp open reading frame that encodes a pheromone precursor and that has homology to other fungal mating factors (20). STE12α is a homologue of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae STE12 gene and is predicted to encode an 855-amino-acid protein. Between amino acids 85 to 201 lies a homeodomain with a high degree of identity to the STE12 homeodomains of other fungal species (30). All molecular work on the mating-type locus of C. neoformans done to date has used C. neoformans var. neoformans. However, hybridization studies with C. neoformans var. gattii DNA have indicated the presence of similar or identical MFα and STE12α genes in strains of the α mating type (30, 32).

The current study was undertaken to survey for the presence of the two mating types, mating types α and a, in clinical and environmental collections of C. neoformans var. gattii from different regions of Australia. As mating between isolates of C. neoformans var. gattii was difficult to induce, we used a molecular approach, using specific PCR primers to selectively amplify the MFα and STE12α sequences from α-mating-type strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection of C. neoformans var. gattii isolates.

One hundred thirty-one environmental isolates were obtained from various trees in three Australian states: South Australia (SA), New South Wales (NSW), and Queensland (QLD). The isolates were collected either from a single tree or from a number of trees (in close proximity). In addition, a few of the environmental isolates came from dead branches used as perches within a koala enclosure in a wildlife park. The details about these isolates are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Environmental isolates of C. neoformans var. gattii

| Isolate no.; source | Geographical location | Tree type | Isolate source | Date (mo/yr) isolated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bal 1 to Bal 30; tree B1a | Balranald, NSW | E. camaldulensis | Woody debris | 2/1996 |

| 401 Bal 2, 402 Bal 6, 402/1, 403 Bal 8, 405 Bal 2c, 406 Bal 2d, 407 Bal 2f, 408 B1, 409 B2, 410 B5a | Balranald, NSW | E. camaldulensis | Bark, woody debris, soil | 12/1989 to 1/1990 |

| 404 H22ba | Hay, NSW | E. camaldulensis | Soil, wood nuts | 12/1989 to 1/1990 |

| Ad 1 to Ad 26, tree A1a | Adelaide, SA | E. camaldulensis | Woody debris | 1/1996 |

| GC 1 to GC8, GC 10 to GC 12, GC 15 to GC 18, GC 21 to GC 30; tree GC1a | Gold Coast, QLD | E. tereticornis | Woody debris | 1/1996 |

| E 268, tree R1; E 275, tree R1; E 276, tree R2; E 278, tree R2; E 280, tree R2; E 281, tree R2; E 283, tree R3; E 286, tree R4; E 287, tree R4; E 296, tree R6; E 297, tree R6; E 306, tree R9; E 307, tree R9; E 310, tree R9; E 312, tree R10; E 316, tree R14 | Renmark, SA | E. camaldulensis | Woody debris | 7/1998 |

| E 1, E 1a, E 2, and E 3; tree Stl1 | St Ives, Sydney, NSW | A. costata | Wood, detritus | 10/1997 to 12/1997 |

| E 444 (1 to 6); tree Stl1 | St Ives, Sydney, NSW | A. costata | Woody debris | 11/1998 |

| E 7 | ||||

| E 22, E 216, E 218, E 361, E 442 | Coffs Harbour, NSW | Tree perch of koalas at zoo | 12/1997 | |

| 7/1998 | ||||

| 9/1998 | ||||

| 10/1998 | ||||

| E 71 | Pilliga, NSW | Leaf litter | 1/1998 | |

| E 147 | Breza, NSW | Leaf litter | 3/1998 | |

| E 238, E 383, E 388, E 389 | Port Macquarie, NSW | Tree perch or ground of koalas at zoo | 7/1998 | |

| 10/1998 | ||||

| E 258 | Port Macquarie, NSW | E. grandis | Woody debris | 7/1998 |

Supplied by D. Ellis and T. Pfeiffer, Mycology Unit, Women’s & Children’s Hospital, Adelaide, SA, Australia.

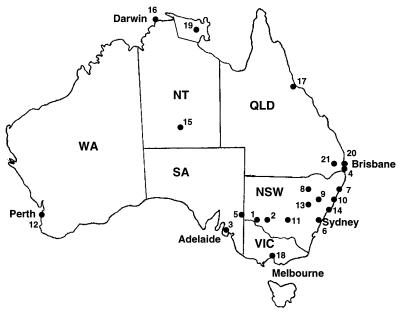

Thirty-nine isolates were obtained from animals with cryptococcosis within NSW and Western Australia (WA) (Table 2), and 30 clinical isolates from humans came from patients in the Northern Territory (NT), Victoria (VIC), SA, NSW, WA, and QLD, and were obtained from the culture collection of Westmead Hospital, Sydney, NSW (Table 3). For the isolates from animals, the month and year of infection were determined from the time when symptoms first became evident rather than from the time when the animal was presented to the veterinarian and C. neoformans var. gattii was cultured. The geographical locations of all environmental and clinical isolates are illustrated in Fig. 1.

TABLE 2.

Clinical isolates of C. neoformans var. gattii from animals

| Isolate | Location | Animal source | Date (mo/yr) isolated |

|---|---|---|---|

| 571 123 | Windsor, Sydney | Alpaca | 9–10/1995 |

| 571 118 | Engadine, Sydney | Cat | 1–02/1995 |

| 571 073 | Coogee, Sydney | Cat | 9–10/1992 |

| 571 015 | Cobbity, Sydney | Cat | 1–2/1990 |

| 571 058 | Chiswick, Sydney | Cat | 9–10/1991 |

| 571 111 | Beacon Hill, Sydney | Cat | 9–10/1994 |

| 571 115 | Bondi Junction, Sydney | Cat | 2/1995 |

| 571 108 | Bayview, Sydney | Cat | 7–8/1994 |

| 571 067 | The Oaks, Sydney | Cat | 3–4/1992 |

| 571 043 | Hornsby Heights, Sydney | Cat | 1–2/1991 |

| 571 112 | Woollahra, Sydney | Cat | 8/1994 |

| 571 093 | Carlingford, Sydney | Dog | 7–8/1982 |

| 571 116 | Camden, Sydney | Dog | 1–2/1995 |

| 571 094 | West Wyalong, NSW | Dog | 9–10/1995 |

| 571 098 | Port Macquarie, NSW | Koala | 3/1994 |

| 571 100 | Taronga Zoo, Sydney | Koala | 4/1994 |

| 571 146 | Wentworthville, Sydney | Cat | 1–2/1996 |

| 1408a | Perth, WA | Sheep | |

| 1410a | Perth, WA | Sheep | |

| 571 147 | Rosemeadow, Sydney | Cat | 5–6/1996 |

| 494a | Perth, WA | Horse | |

| WA 861 | Perth, WA | Dog | 4/1996 |

| 1409a | Perth, WA | Sheep | |

| 571 170 | Tamworth, NSW | Cat | 5/1997 |

| 571 169 | Fairfield, Sydney | Dog | 4/1997 |

| 571 178 | Rose Bay, Sydney | Cat | 8/1997 |

| 571 171 | Coffs Harbour, NSW | Koala | 2/1997 |

| 571 172 | Dubbo, NSW | Koala | 3/1997 |

| 447/98 | Newcastle, NSW | Cat | 1998 |

| Pilliga 1 to 10b | Pilliga, NSW | Koala | 5/1998 |

Supplied by D. Ellis and T. Pfeiffer, Mycology Unit, Women’s & Children’s Hospital, Adelaide, SA, Australia.

Ten isolates.

TABLE 3.

Clinical isolates of C. neoformans var. gattii from humans

| Isolatea | Location | Clinical source | Date (mo/yr) isolated |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Adelaide, SA | CSFb | 9/1990 |

| H2 | Adelaide, SA | CSF | 6/1990 |

| H3 | Alice Springs, NT | CSF | |

| H4 | Alice Springs, NT | CSF | 9/1994 |

| H5 | WA | ||

| H6 | WA | ||

| H7 | WA | ||

| H8 | Alice Springs, NT | CSF | |

| H9 | WA | ||

| H10 | WA | ||

| H11 | Darwin, NT | ||

| H12 | Townsville, QLD | CSF | 8/1996 |

| H13 | Melbourne, VIC | Skin | 12/1995 |

| H14 | Townsville, QLD | CSF | 5/1997 |

| H15 | Townsville, QLD | CSF | 7/1997 |

| H16 | Arnhem Land, NT | Lung | 4/1996 |

| H17 | Alice Springs, NT | CSF | |

| H18 | Newcastle, QLD | Skin | 12/1994 |

| H19 | WA | ||

| H20 | Brisbane, QLD | CSF | 5/1994 |

| H21 | Brisbane, QLD | Lung | 12/1995 |

| H22 | Arnhem Land, NT | Lung | 2/1994 |

| H23 | Brisbane, QLD | Lung | 4/1994 |

| H24 | Brisbane, QLD | Lung | 6/1995 |

| H25 | Sydney, NSW | CSF | 5/1994 |

| H26 | Darwin, NT | CSF | 1/1994 |

| H27 | Toowomba, QLD | CSF | 12/1994 |

| H28 | Sydney, NSW | Lung | 12/1994 |

| H29 | Melbourne, VIC | Blood | 1991 |

| H30 | Melbourne, VIC | Lung | 1988 |

All isolates supplied by W. Meyer and H. Daniel, Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology, Westmead Hospital, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of environmental and clinical isolates used in the study: 1, Balranald; 2, Hay; 3, Adelaide; 4, Gold Coast; 5, Renmark; 6, Sydney; 7, Coffs Harbour; 8, Pilliga; 9, Breza/Tamworth; 10, Port Macquarie; 11, West Wyalong; 12, Perth; 13, Dubbo; 14, Newcastle; 15, Alice Springs; 16, Darwin; 17, Townsville; 18, Melbourne; 19, Arnhem Land; 20, Brisbane; 21, Toowomba.

All isolates were subcultured onto Sabouraud dextrose agar (Amyl medium) and were incubated for 48 h at 25°C for DNA extraction.

Mating type crosses.

The reference strains B-3501 (mating type α) and B-3502 (mating type a) of Filobasidiella neoformans var. neoformans (10) and strains CBS 6956 (mating type α) and CBS 6955 (mating type a) of F. neoformans var. bacillispora (16) were used in all mating-type crosses. The media used for the crosses included V8 juice agar (14), sucrose biotin agar (11), eucalyptus seed agar (50 g of E. camaldulensis seed, 1 g of glucose, 1 g of KH2PO4, 1 g of creatinine, 15 g of Bacto Agar, 1,000 ml of distilled H2O, 1 ml of penicillin G [20 U/ml], and 1 ml of gentamicin [80 mg/ml]), and moist autoclaved E. camaldulensis bark. A loopful of 2-day-old yeast cells of the strain being studied was mixed with a loopful of an α or a mating type tester strain in the center of the plate or bark (25), and the plate or bark was incubated at 25°C for 2 weeks. This was observed periodically for the development of the perfect state.

DNA isolation.

The chromosomal DNA extraction procedure was based on the Novozyme 234, dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide, and hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide method described by Wen et al. (29) with the following modifications: approximately 0.75 g of cells (wet weight) grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar were collected, the protoplasting solution was made with 10 mg of Novozyme 234 per ml of SCS buffer (20 mM sodium citrate, 1 M sorbitol), and all centrifugation steps were performed at 12,879 × g. The DNA pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8]) containing 10 μg of RNase A (Progen) per ml. DNA was diluted 1:10 for PCR amplification.

Primer design.

The MFα primers (primers MFαU and MFαL) were designed from within the open reading frame of the MFα pheromone gene (20) and were expected to amplify a 109-bp fragment from α-mating-type strains. The STE12α primers (primers STE12αU and STE12αL) were designed from within the homeodomain of the STE12α gene (30) and were expected to amplify a 150-bp fragment from MATα strains. Primers 660U and 660L were designed from an anonymous DNA fragment amplified by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis-PCR from a C. neoformans var. gattii strain. These primers were used in coamplifications with the MFα primers and were designed to amplify a 216-bp fragment from all C. neoformans var. gattii strains. Oligo 5.0 software was used to optimize the design of all primers. Primer sequences are listed in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Primers used in PCR amplifications

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Annealing temp (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| MFαU | TTCACTGCCATCTTCACCACC | 55 |

| MFαL | TCTAGGCGATGACACAAAGGG | 55 |

| 660U | TATTGGACTAAAACGGTATGCGG | 55 |

| 660L | CGACGACGAGGTATTCTTTTTCC | 55 |

| STE12αU | CAATCTCAAAGCGGGGACAG | 50 |

| STE12αL | CTTTGTTTCGGTCCTAATACAGCC | 50 |

PCR amplification and sequencing.

PCR amplifications were performed in 50-μl volumes containing 1× PCR buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 0.5 M KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 0.1% gelatin), 5% glycerol, 250 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 2.5 U of Taq polymerase, 1 μl of diluted template DNA, and either 30 pmol of primers MFαU and MFαL plus 25 pmol of primers 660U and 660L or 25 pmol of primers STE12αU and STE12αL. The reaction mixtures were overlaid with sterile mineral oil (Sigma). Amplification conditions for PCR were 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55 or 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. All amplifications were carried out in a Perkin-Elmer Cetus model 480 Thermal Cycler. A total of 10 μl of each amplification product was electrophoresed at 10 V/cm and 40 mA in 2% agarose gels containing 0.50 ng of ethidium bromide per ml. The gels were visualized by UV transillumination and were photographed.

The PCR products of selected C. neoformans var. gattii and C. neoformans var. neoformans isolates were purified by polyethylene glycol 8000 precipitation (23) and were sequenced in both directions with a Perkin-Elmer model 377 automated sequencer with dye terminators and the MFα or STE12α primers. The sequences were edited and merged by using the TED (9) and SEQASM programs and were aligned by using CLUSTAL W (27). These programs were accessed through the Australian National Genomic Information Service at The University of Sydney.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for the MFα sequences are AF 155335, AF 155336, AF 155337, AF 155338, AF 155339, AF 155340, and AF 155341. The GenBank accession numbers for the STE12α sequences are AF 155342, AF 155343, AF 155344, AF 155345, AF 155346, AF 155347, AF 155348, and AF 155349.

RESULTS

Mating-type crosses.

The α and a mating type test strains of F. neoformans var. neoformans were observed to mate only on the V8 juice agar, producing a dense white mycelial phase at the edge of the yeast colony. Basidium-producing chains of basidiospores and hyphae with clamp connections were observed under the microscope. These strains did not mate on any of the other media tested.

The α and a mating type test strains of F. neoformans var. bacillispora did not mate on any of the media. Likewise, none of the clinical or environmental isolates included in this study reacted with the α or a mating type test strains of either variety or with other isolates from the same collection.

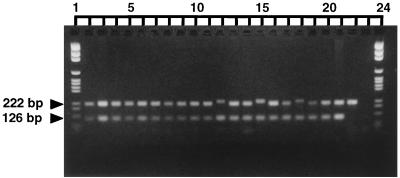

Coamplification with primers MFα and 660.

The MFα primers successfully amplified a 109-bp fragment from all culture collection strains of both varieties known to be of the α mating type but did not produce a fragment from any of the strains of the a mating type. Coamplification with the MFα and 660 primers was performed with DNAs from all of the environmental and clinical isolates listed in Tables 1, 2, and 3. The CBS strains characterized as being of the α and a mating types were included in each PCR run to act as positive controls. Representative profiles are shown in Fig. 2 and 3a, and a complete summary of the ratio of α mating types:a mating types is given in Table 5.

FIG. 2.

Representative gel of DNA from clinical and environmental C. neoformans var. gattii isolates coamplified with the MFα and 660 primers. Lanes: 1 and 24, pGEM size marker (Promega); 2, GC5; 3, GC12; 4, GC17; 5, GC22; 6, GC27; 7, Ad5; 8, Ad12; 9, Ad17; 10, Ad22; 11, Ad26; 12, 1408; 13, 571 146; 14, 571 067; 15, 1409; 16, 571 178; 17, H28; 18, H23; 19, H13; 20, H8; 21, CBS 5757 (α); 22, CBS 6998 (a); 23, negative control for PCR amplification. The upper band of 216 bpl of 109 bp was amplified by the 660 primers; the lower band was amplified by the MFα primers. Primer dimer can be seen below many of the amplified fragments. Lanes 12, 15, and 18 show slight variation in size of 660 fragment.

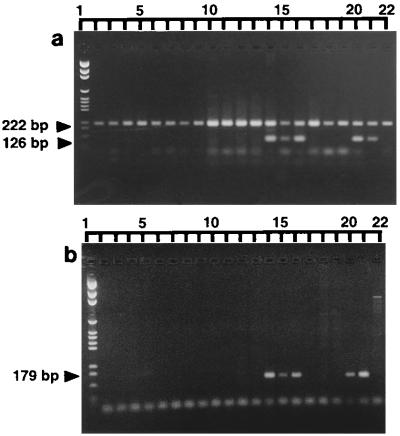

FIG. 3.

Representative gel of DNA from Balranald isolates coamplified by the MFα and 660 primers (a) and the STE12α primers (b). Lanes 1: pGEM size marker; 2, Bal 23; 3, Bal 24; 4, Bal 25; 5, Bal 26; 6, Bal 27; 7, Bal 28; 8, Bal 29; 9, Bal 30; 10, 401 Bal 2; 11, 402 Bal 6; 12, 402/1; 13, 403 Bal 8; 14, 405 Bal 2c; 15, 406 Bal 2d; 16, 407 Bal 2f; 17, 408 B1; 18, 409 B2; 19, 410 B5; 20, 404 H22b; 21, CBS 5757 (α); 22, CBS 6998 (a). Primer dimers can be seen in many of the lanes.

TABLE 5.

Summary of mating types among 130 environmental and 69 clinical isolates of C. neoformans var. gattii

| Source | α mating type:a mating type | % α mating type |

|---|---|---|

| Single tree | ||

| Adelaide | 26:0 | 100 |

| Balranald, 1989–1990 | 3:7 | 30 |

| Balranald, 1996 | 2:27 | 7 |

| Gold Coast | 25:0 | 100 |

| Separate trees | ||

| Breza | 1:0 | 100 |

| E 7 | 1:0 | 100 |

| Hay | 1:0 | 100 |

| Pilliga | 1:0 | 100 |

| Port Macquarie | 1:0 | 100 |

| Renmark | 10:6 | 62.5 |

| St Ives | 10:0 | 100 |

| Animal cage | ||

| Coffs Harbour | 5:0 | 100 |

| Port Macquarie | 4:0 | 100 |

| Clinical isolates | ||

| Animal | 38:1 | 97.4 |

| Human | 30:0 | 100 |

Of the 69 clinical isolates coamplified by the MFα and 660 primers, one (571 093; Table 2) did not produce the MFα fragment. All clinical isolates produced the 660 fragment, although a slight variation in the size of this fragment was seen in some strains (Fig. 2). In contrast, 40 of the 131 environmental isolates did not produce the MFα band. These isolates were obtained from two of the nine locations sampled: Balranald (NSW) and Renmark (SA). Isolates Bal 3 (Table 1) and H26 (Table 3) did not produce the 660 band but did produce the MFα band.

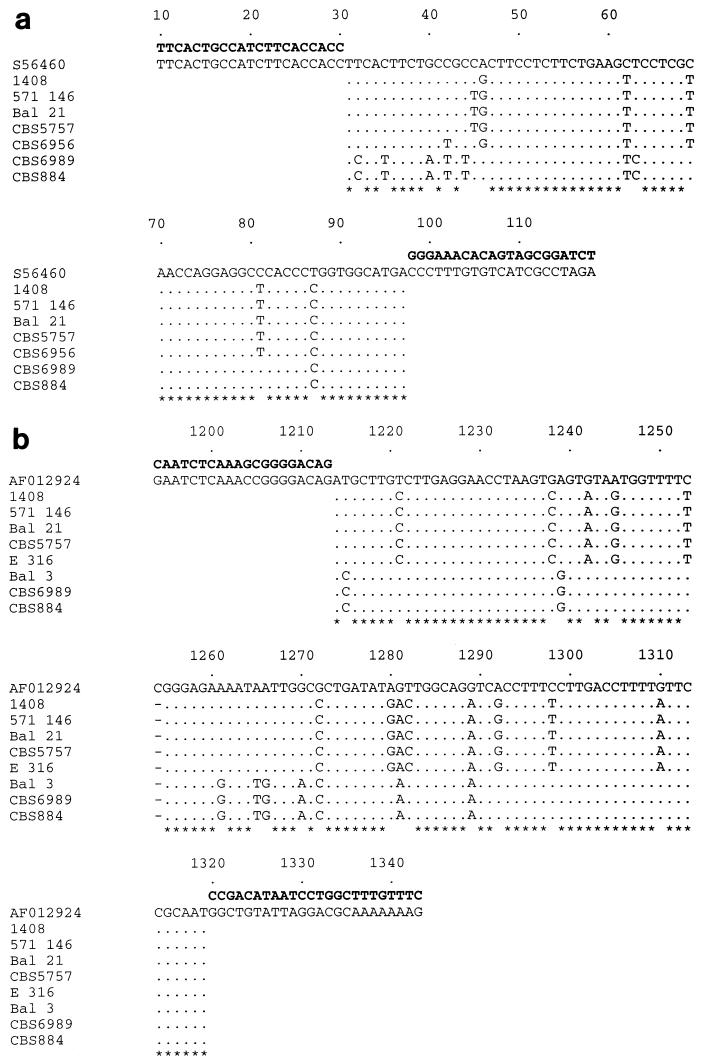

The MFα fragment was sequenced from five C. neoformans var. gattii isolates and two C. neoformans var. neoformans isolates and had greater than 90% identity to the corresponding segment from the published C. neoformans var. neoformans MFα pheromone gene (Fig. 4a) (20).

FIG. 4.

Sequence alignments of the 109-bp MFα fragment with the MFα gene (GenBank accession no. S56460), which covers nucleotide positions 10 to 118 (a), and the 149-bp STE12α fragment with the corresponding segment of the STE12α GenBank sequence (accession no. AF012924), which covers nucleotide positions 1194 to 1343 (b). Both GenBank sequences were from C. neoformans var. neoformans isolates. The primer sequences are shown in bold, and asterisks indicate positions which are identical in all isolates.

Amplification with STE12α primers.

The STE12α primers were designed to confirm the results already obtained from the MFα-660 coamplifications, as failure to produce the MFα band could also be due to a polymorphism(s) in the primer binding sites. Representative amplification profiles are shown in Fig. 3b. Previously characterized CBS strains of the α and a mating types were again included as positive controls. All isolates that did not produce the MFα band also failed to produce the STE12α band. All remaining isolates produced both bands. Direct sequencing of the STE12α PCR fragments from five C. neoformans var. gattii isolates and three C. neoformans var. neoformans isolates found that they had a high degree of homology to the corresponding segment of the published STE12α gene, with polymorphisms shared between isolates belonging to each variety (Fig. 4b) (30).

DISCUSSION

For more than a decade, C. neoformans var. gattii has been known to have a specific ecological association with a number of eucalyptus species. Epidemiological studies have supported the association between human clinical disease and the natural reservoir of the fungus (24). The current study was undertaken to survey for the presence of the α and a mating types in C. neoformans var. gattii strains isolated from the environment and from humans and animals with cryptococcosis. The eventual aim of this work will be to determine whether the fungus completes its life cycle in association with the eucalyptus host, undergoing sexual recombination and producing potentially infectious basidiospores.

Mating analyses failed to determine the mating type of any of the isolates used in this study, despite the use of a variety of different isolates and a range of conditions. Kwon-Chung and colleagues (17) experienced similar difficulties with inducing mating in four strains of C. neoformans var. gattii isolated from E. camaldulensis trees. We therefore used a molecular approach to determine mating type.

To date, only the α-mating-type locus has been isolated and sequenced, and we were able to assign the a mating type to an isolate only by failure to amplify the α-mating-type-specific sequences. A positive control was therefore included in the MFα amplifications to ensure that the absence of the MFα fragment was not due to inhibition of the PCR. Two isolates, isolates H26 and Bal 3, did not produce a band with the positive control 660 primers, but amplification was successful with the MFα primers. RAPD analysis-PCR has since shown Bal 3 to be C. neoformans var. neoformans (data not shown), but isolate H26 is definitely C. neoformans var. gattii as it is serotype B. It is therefore likely that this isolate has a polymorphism at one of the 660 primer binding sites. In addition, slight differences in the sizes of the product amplified by the 660 primers were seen between some of the clinical isolates (Fig. 2). These isolates have been found to be of the VGII type, a minor variant of C. neoformans var. gattii previously reported by Sorrell et al. (24).

A total of 100% of the human and 97.4% of the animal clinical isolates produced both the MFα band and the STE12α band and can therefore be assumed to be of the α mating type. This imbalance is similar to that found in studies of clinical isolates of C. neoformans var. neoformans (12, 19, 26) and may indicate that, like C. neoformans var. neoformans, C. neoformans var. gattii α isolates are more virulent than a isolates and are therefore more likely to infect humans and animals (15). The only MATa clinical isolate, 571 093, came from a dog with respiratory failure from which C. neoformans var. gattii was cultured from the lower respiratory tract. No unusual or atypical symptoms were noted in this cryptococcal infection.

Of the 131 environmental isolates of C. neoformans that were collected to determine their mating types, 130 were C. neoformans var. gattii, and 91 (70%) of these were of the α mating type. This is substantially lower than the result of a similar study with C. neoformans var. neoformans, in which 97.5% of the isolates were of the α mating type (12); however, the current study may have been biased by the inclusion of many isolates from single trees. Of the 31 isolates taken from separate trees, 80.6% were of the α mating type. This is still less than the proportion for C. neoformans var. neoformans, although the α mating type remains predominant. In C. neoformans var. neoformans, the bias in mating type has been postulated to be due to haploid fruiting. In this process, haploid α cells form extensive hyphae in the absence of the opposite mating type, producing abundant blastospores and basidia bearing viable basidiospores that are all of the α mating type. This has also been observed in C. neoformans var. gattii strains, but the hyphae are less extensive, and while blastospores are produced, no basidiospores have been detected. Haploid fruiting apparently cannot occur in a-mating-type strains of either variety (31).

MATa isolates were found in collections from two areas, Renmark and Balranald, which lie less than 300 km apart and which share very similar geographies and floras. All the Balranald isolates came from two separate samplings from an individual tree. This tree was unique in that the C. neoformans var. gattii isolates obtained from it were overwhelmingly of the a mating type, especially those isolated in 1996 (27 of 29). These isolates came from a large amount of debris in a semihollow area located at the base of the tree. When isolates taken in 1989 and 1990 were examined, 7 of 10 isolates were of the a mating type, indicating that the predominance of a-mating-type isolates in 1996 may have been caused by sampling artifact. Alternatively, the a mating type may be becoming more predominant over time via clonal propagation. We are currently using RAPD analysis-PCR to assess the genetic diversity in this collection.

The results presented in this report indicate that, in contrast to C. neoformans var. neoformans, both mating types can be found in some populations of C. neoformans var. gattii. In particular, in the population from Renmark, the ratio of the two mating types (10 α:6 a) approximated the 50:50 ratio expected to result from sexual outcrossing. The ability of pathogens to recombine sexually is important for their ability to survive the host immune response and to adapt to novel environmental challenges, including antimicrobial therapy. The clonal population structure reported for C. neoformans var. neoformans (7) is unusual compared to those reported for other medically important fungi, in which a history of sexual exchange has been seen (1, 2). Our results suggest that C. neoformans var. gattii may also reproduce sexually, but further studies analyzing the association of molecular markers are necessary to test this hypothesis (28). The mating type survey indicates that Renmark will be a suitable region as a target for future studies of genetic recombination in C. neoformans var. gattii.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tania Pfeiffer for supplying many of the environmental isolates and Wieland Meyer and Heide-Marie Daniel for supplying the 30 human clinical isolates. Patricia Martin and Denise Wigney maintained the veterinary collection of C. neoformans strains.

This work was supported by a project grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (grant 970648). The Clive and Vera Ramaciotti Foundation financed the purchase of the thermocycler. Catriona Halliday thanks the Faculty of Agriculture at The University of Sydney for financial support through the Alexander Hugh Thurburn Scholarship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burt A, Carter D A, Koenig G L, White T J, Taylor J W. Molecular markers reveal cryptic sex in the human pathogen Coccidioides immitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:770–773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter D A, Burt A, Taylor J W, Koenig G L, White T J. Clinical isolates of Histoplasma capsulatum from Indianapolis, Indiana, have a recombining population structure. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2577–2584. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2577-2584.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis D H, Pfeiffer T J. Ecology, life cycle and infectious propagule of Cryptococcus neoformans. Lancet. 1990;336:923–925. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92283-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis D H, Pfeiffer T J. Natural habitat of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1642–1644. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.7.1642-1644.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis D H, Pfeiffer T J. The ecology of Cryptococcus neoformans. Eur J Epidemiol. 1992;8:321–325. doi: 10.1007/BF00158562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher D, Burrows J, Lo D, Currie B. Cryptococcus neoformans in tropical northern Australia: predominantly variant gattii with good outcomes. Aust NZ J Med. 1993;23:678–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1993.tb04726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franzot S P, Hamdan J S, Currie B P, Casadevall A. Molecular epidemiology of Cryptococcus neoformans in Brazil and the United States: evidence of both local genetic differences and a global clonal population structure. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2243–2251. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2243-2251.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Hermoso D, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, Couprie B, Ronin O, Dupont B, Dromer F. DNA typing suggests pigeon droppings as a source of pathogenic Cryptococcus neoformans serotype D. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2683–2685. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2683-2685.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gleeson T J, Staden R. An X Windows and UNIX implementation of our sequence analysis package. Comput Appl Biosci. 1991;7:398. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/7.3.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon-Chung K J. Morphogenesis of Filobasidiella neoformans, the sexual state of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mycologia. 1976;68:821–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon-Chung K J. A new species of Filobasidiella, the sexual state of Cryptococcus neoformans B and C serotypes. Mycologia. 1976;68:942–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon-Chung K J, Bennett J E. Distribution of α and a mating types of Cryptococcus neoformans among natural and clinical isolates. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108:337–340. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon-Chung K J, Bennett J E. Cryptococcosis. In: Kwon-Chung K J, Bennett J E, editors. Medical mycology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lea & Febiger; 1992. pp. 397–446. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon-Chung K J, Bennett J E, Rhodes J C. Taxonomic studies of Filobasidiella species and their anamorphs. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1982;48:25–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00399484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwon-Chung K J, Edman J C, Wickes B L. Genetic association of mating types and virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1992;60:602–605. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.602-605.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon-Chung K J, Fell J W. Filobasidiella. In: Kreger-van Rij N J W, editor. The yeasts: a taxonomic study. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1984. pp. 472–482. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon-Chung K J, Wickes B L, Stockman L, Roberts G D, Ellis D, Howard D H. Virulence, serotype and molecular characteristics of environmental strains of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1869–1874. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.1869-1874.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazera M S, Pires F D A, Camillo-Coura L, Nishikawa M M, Bezerra C C F, Trilles L, Wanke B. Natural habitat of Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans in decaying wood forming hollows in living trees. J Med Vet Mycol. 1996;34:127–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madrenys N, De Vroey C, Raes Wuytack C, Torres-Rodriguez J M. Identification of the perfect state of Cryptococcus neoformans from 195 clinical isolates including 84 from AIDS patients. Mycopathologia. 1993;123:65–68. doi: 10.1007/BF01365081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore T D E, Edman J C. The α-mating type locus of Cryptococcus neoformans contains a peptide pheromone gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1962–1970. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.3.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeiffer T J, Ellis D H. Environmental isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii from Eucalyptus tereticornis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1992;30:407–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfeiffer T J, Ellis D H. Abstracts of the International Meeting and Exhibition of Australian and New Zealand Societies for Microbiology. 1996. Additional eucalypt hosts of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii, abstr. P5.6; p. A53. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenthal A, Coutelle O, Craxton M. Large-scale production of DNA sequencing templates by microtitre format PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:173–174. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorrell T C, Chen S C A, Ruma P, Meyer W, Pfeiffer T J, Ellis D H, Brownlee A G. Concordance of clinical and environmental isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii by random amplification of polymorphic DNA analysis and PCR fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1253–1260. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1253-1260.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swinne D, Bauwens L, Desmet P. More information about the natural habitat of Cryptococcus neoformans. ISHAM Newsl. 1992;60:4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeo K, Tanaka R, Taguchi H, Nishimura K. Analysis of ploidy and sexual characteristics of natural isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans. Can J Microbiol. 1993;39:958–963. doi: 10.1139/m93-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tibayrenc M, Kjellberg F, Arnaud J, Oury B, Breniere S F, Darde M, Ayala F J. Are eukaryotic micro-organisms clonal or sexual? A population genetics vantage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5129–5133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wen H, Caldarelli-Stefano R, Tortorano A M, Ferrante P, Viviani M A. A simplified method to extract high-quality DNA from Cryptococcus neoformans. J Mycol Med. 1996;6:136–138. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wickes B L, Edman U, Edman J C. The Cryptococcus neoformans STE12α gene: a putative Saccharomyces cerevisiae STE12 homologue that is mating type specific. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:951–960. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6322001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wickes B L, Mayorga M E, Edman U, Edman J C. Dimorphism and haploid fruiting in Cryptococcus neoformans: association with the α-mating type. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7327–7331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wickes B L, Moore T D E, Kwon-Chung K J. Comparison of the electrophoretic karyotypes and chromosomal location of 10 genes in the 2 varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Microbiology. 1994;140:543–550. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-3-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]