Abstract

The general transcription factor TFIID, which is composed of TATA-binding protein (TBP) and an array of TBP-associated factors (TAFs), has been shown to play a crucial role in recognition of the core promoters of eukaryotic genes. We isolated Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast TAF145 (yTAF145) temperature-sensitive mutants in which transcription of a specific subset of genes was impaired at restrictive temperatures. The set of genes affected in these mutants overlapped with but was not identical to the set of genes affected by a previously reported yTAF145 mutant (W.-C. Shen and M. R. Green, Cell 90:615–624, 1997). To identify sequences which rendered transcription yTAF145 dependent, we conducted deletion analysis of the TUB2 promoter using a novel mini-CLN2 hybrid gene reporter system. The results showed that the yTAF145 mutations we isolated impaired core promoter recognition but did not affect activation by any of the transcriptional activators we tested. These observations are consistent with the reported yTAF145 dependence of the CLN2 core promoter in the mutant isolated by Shen and Green, although the CLN2 core promoter functioned normally in the mutants we report here. These results suggest that different promoters require different yTAF145 functions for efficient transcription. Interestingly, insertion of a canonical TATA element into the TATA-less TUB2 promoter rescued impaired transcription in the yTAF145 mutants we studied. It therefore appears that strong binding of TBP to the core promoter can alleviate the requirement for at least one yTAF145 function.

In eukaryotes, transcriptional initiation by RNA polymerase II requires a set of general transcriptional factors (TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIID, TFIIE, TFIIF, and TFIIH) (reviewed in references 16, 72, and 78) and the SRB-MED complex associated with the carboxy-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II (reviewed in references 65 and 66). These factors nucleate on the core promoter of eukaryotic class II genes to form a preinitiation complex in an ordered stepwise fashion (reviewed in references 9, 23, and 78) or are recruited in a simpler sequence involving a small number of preassembled units (reviewed in references 43 and 73). In either case, the first step, which is the sequence-specific binding of TFIID (76), is thought to be a major rate-limiting step during transcription and a focal point for the activity of transcriptional activators (14, 40, 54).

TFIID is a multiprotein complex composed of TATA-binding protein (TBP) and an array of TBP-associated factors (TAFs); in total, the complex includes 8 to 12 molecules ranging in size from 15 to 250 kDa (reviewed in references 11, 51, 91, and 93). Almost all of these TAFs are conserved among evolutionarily divergent organisms (humans, Drosophila melanogaster, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae), albeit with a few exceptions (for instance, no orthologue of Drosophila TAF110 or human TAF130 (dTAF110/hTAF130) is found in yeast). This level of conservation suggests that TAFs play a fundamental role in eukaryotic transcription (reviewed in references 5, 11, 81, and 91). Earlier biochemical studies in vitro demonstrated that TAFs are obligatory cofactors for activation, since TBP alone can mediate basal transcription but, unlike TFIID, cannot support activated transcription (reviewed in references 11, 20, and 42). However, the concept of an absolute requirement for TAFs in activation has been challenged by a number of recent studies. First, several groups reported that activation can be successfully reconstituted in an in vitro transcription system using yeast or human components that include TBP but no detectable amounts of TAFs (24, 39, 44, 69, 103). Second, in vivo depletion of functional TAFs in yeast cells demonstrated that the absence of certain TAFs had little effect on the activation mediated by a variety of activators, including Gcn4, Ace1, Gal4, and Hsf (63, 98).

However, TAFs do play important roles in TFIID recognition of core promoter elements. TFIID requires TAFs for core promoter binding, especially when the canonical TATA element is absent (reviewed in references 11, 21, and 97). TAF-DNA interactions appear to compensate for the lack of direct TBP-TATA interactions on TATA-less promoters (58, 74). Indeed, a number of TAFs have been identified which recognize sequence elements near or downstream of the initiation site (10, 13, 38, 68, 96). Moreover, TAFs were also shown to mediate transcriptional synergism between TATA and initiator elements along with TFIIA and TAFII- and initiator-dependent cofactors (TICs) (21, 56). The requirement for TAFs in core promoter recognition has been further demonstrated by genetic studies. In vivo TAF depletion experiments demonstrated that Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast TAF145 (yTAF145) is not generally required for transcriptional activation (63, 98) but is essential for a subset of genes (84, 99). Importantly, promoter-swapping experiments provided evidence that yTAF145 dependence is conferred by sequences within the core promoter region rather than upstream activating sequences (UAS) (84). These observations argue that the principal role of TAFs is to recognize core promoter elements.

Recently, several TAFs were reported to be integral components not only of TFIID but also of large histone acetyltransferase (HAT) complexes (reviewed in reference 88), including yeast SAGA (26) and mammalian PCAF complex (71), TFTC (8, 102), and STAGA (57). Earlier genetic studies in yeast demonstrated that several components of these complexes (such as ADAs and SPTs) are involved in transcriptional regulation (reviewed in reference 27), and more recent in vitro studies clearly show that SAGA stimulates activator-induced transcription on chromatin templates in an acetyl coenzyme A-dependent manner (36, 95). Additionally, mammalian TFTC can substitute for TFIID in transcriptional initiation from TATA-containing and TATA-less promoters as well as in activation by GAL4-VP16 in vitro (102). These observations raise the intriguing possibility that the HAT complexes described above and TFIID may function redundantly in vivo. In this respect, it is notable that TFIID also has HAT activity (62). In yeast, five TAFs (yTAF90, -60, -17/20, -25, and -68/61) are components of both TFIID and SAGA (26). Of these, histone-like TAFs, such as yTAF68/61 (histone H2B-like), yTAF60 (histone H4-like), and yTAF17/20 (histone H3-like), and the non-histone-like yTAF25 were reported to be required for transcription of a broader range of genes than other TAFs (1, 29, 34, 61, 64, 67, 80). More importantly, unlike yTAF145, these histone-like TAFs are apparently involved in transcriptional activation as well (1). The observation that shared TAFs appear to be more crucial for in vivo transcription and activation than TFIID-specific TAFs supports the notion that TFIID and SAGA are functionally redundant.

In mammalian cells, a point mutation in TAF250 (an orthologue of yTAF145) was shown to cause late G1 cell cycle arrest in temperature-sensitive ts13 cells (31, 33, 79, 83). Interestingly, only a subset of genes, including cyclin D1 and cyclin A, were affected in these cells (55, 82, 90, 100). This parallels the phenotype of yTAF145 mutant cells, which are also arrested in G1 phase (98) and do not show general transcriptional defects at restrictive temperatures (99). However, the region that renders the cyclin A gene promoter TAF250 dependent in ts13 cells was mapped to UAS in addition to core promoter sequences (101). This suggests that specific activator function is impaired in ts13 cells, in contrast to the yTAF145 mutant, in which core promoter recognition does not operate normally (84). Recently, however, yTAF145 has also been shown to be required for specific activator function (45). The transactivation domain IV (TADIV) of ADR1, a yeast activator that regulates transcription of the ADH2 gene (17), functions much less efficiently in a yTAF145 mutant (45). Meanwhile, it has been demonstrated that Drosophila TAF110 and TAF60 are important for activation by dorsal, a transcription factor that regulates twist and snail in embryos (104). Despite these observations, the full extent to which TAFs are required for activation in vivo remains unclear.

To further investigate TAF function in vivo, we isolated a number of novel yTAF145 temperature-sensitive (TS) mutants. Interestingly, the expression profiles of some genes in these mutants were not identical to those in a previously reported yTAF145 mutant (84, 99). Deletion analysis of the TUB2 promoter demonstrated that core promoter elements rather than UAS are responsible for yTAF145 dependency in our mutants. Various activation domains activated a reporter construct normally when directed by the CYC1 core promoter but not when controlled by the TUB2 core promoter. Thus, transcriptional activators appear to be unable to compensate for the loss of yTAF145 function in core promoter recognition. Interestingly, in contrast to the earlier yTAF145 mutant (84), insertion of a canonical TATA element restored transcription directed by the TUB2 promoter in our mutants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of a mutated plasmid library by error-prone PCR.

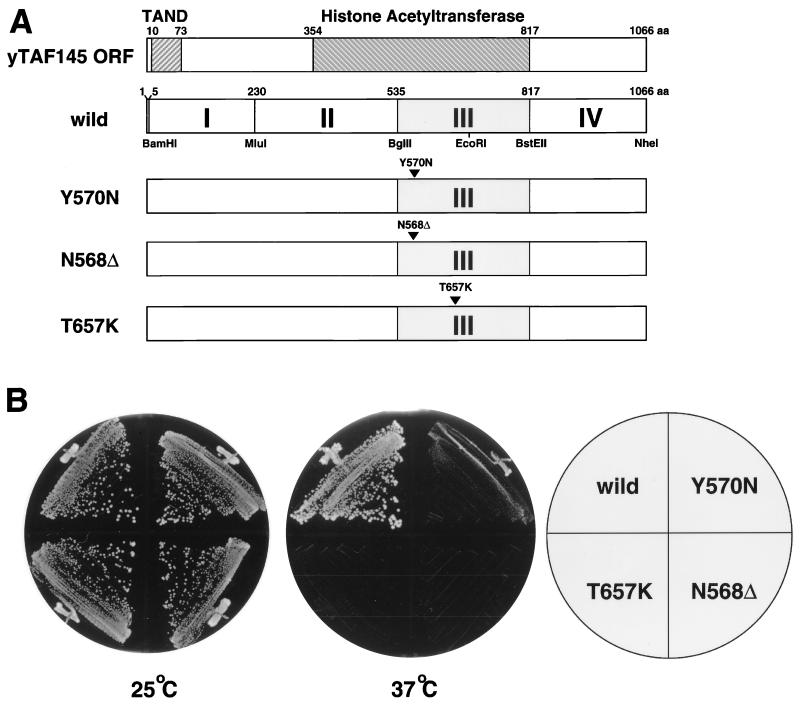

To generate randomly mutated yTAF145 libraries, we divided the entire open reading frame (ORF) of the yTAF145 gene into four regions, denoted I (amino acids [aa] 5 to 230), II (aa 231 to 535), III (aa 536 to 817), and IV (aa 818 to 1066), flanked by a set of unique restriction enzyme recognition sequences (Fig. 1A). An MluI site at the junction between regions I and II and an NheI site at the end of region IV were inserted into template pYN2 (41) by site-directed mutagenesis (49) using primers TK65 and TK3. Oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 1. We designated the resulting plasmid pM34. The sequence of region III, flanked by BglII and BstEII sites, was amplified by error-prone PCR (12) using primers TK66 and TK67. A random mutant library was generated by replacing the BglII/BstEII fragment of pM34 with the resulting error-prone PCR products. The plasmid library was transformed into yeast to isolate conditional alleles of the yTAF145 gene as described below.

FIG. 1.

Structure of and growth properties conferred by conditional alleles of the yTAF145 gene obtained by error-prone PCR. (A) Schematic diagram of wild-type and three TS alleles of yTAF145. The entire yTAF145 ORF was divided into four regions flanked by a set of unique restriction enzyme sites. Region III was randomly mutagenized by error-prone PCR, and screening of the resulting plasmid library yielded the TS alleles Y570N, N568Δ, and T657K. The TAND and the HAT domain of yTAF145 are hatched at the top of panel A. (B) Comparison of TS phenotypes. Strains carrying wild-type or mutant alleles were grown on YPD (yeast extract-peptone-dextrose) plates at 25 and 37°C for 3 days.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| TK3 | 5′-AGGACGACGATGACAAGCTAGCCTAGTAGGCATGCTCGCGATGTATTGATCGAAT-3′ |

| TK65 | 5′-ACAAGCTGATTTATAGACGCGTTGTTCCTTATCATTGGC-3′ |

| TK66 | 5′-CACACAAGATCTAACCATCGGGGA-3′ |

| TK67 | 5′-ACACACGGTCACCAACACCATGTA-3′ |

| TK175 | 5′-AAATTAATTAATTATAATCGGAAAGCCAATG-3′ |

| TK176 | 5′-GCCAATAAATTAATTTATTATCGGAAAGCC-3′ |

| TK178 | 5′-TTAACCATCTTTTTAAGGTTGGACAAACTTT-3′ |

| TK184 | 5′-CACACAGAATTCTCCCATAATAGCCCAGAG-3′ |

| TK185 | 5′-CACACAGGATCCTTATTCTGTTGTCTCAAAAAT-3′ |

| TK187 | 5′-CACACAGGATCCTTACCCCCCAAAGTCGTCAAT-3′ |

| TK189 | 5′-CACACAGAATTCGGAATGACCCACGACCCC-3′ |

| TK202 | 5′-CACACACTGCAGTTAGGCACCTTCATCCCCGCC-3′ |

| TK208 | 5′-CACACAGAATTCATGTTTGAGTATGAAAAC-3′ |

| TK209 | 5′-CACACAGGATCCTTAGGATTCAATTGCCTTATC-3′ |

| TK212 | 5′-CACACAGAATTCGACCAAACTGCGTATAAT-3′ |

| TK213 | 5′-CACACAGGATCCTTAGGTATCTTCATCATCGAA-3′ |

| TK249 | 5′-ATGGATTCTGGTATGTTCTAG-3′ |

| TK250 | 5′-GTGTTCTTCTGGGGCAACTCT-3′ |

| TK477 | 5′-CCCCAGTTAAATCCCAAGAAT-3′ |

| TK478 | 5′-TTAAGCCAAGGTGGTCAAGAT-3′ |

| TK489 | 5′-ATGAACCACTCAGAAGTGAAA-3′ |

| TK490 | 5′-AAACCTACCACCTGTGGGGAT-3′ |

| TK491 | 5′-ATGGCTAGTGCTGAACCAAGA-3′ |

| TK492 | 5′-CCAGAGACAAGTAGCGACAAC-3′ |

| TK493 | 5′-ATGTCTGACACCGAAGCTCCA-3′ |

| TK494 | 5′-TTAACGGTTAGACTTGGCAAC-3′ |

| TK521 | 5′-CTAGACGGAGGACTGTCCTCCGA-3′ |

| TK522 | 5′-CTAGTCGGAGGACAGTCCTCCGT-3′ |

| TK531 | 5′-TTCACTATCGAAGCAGCATCA-3′ |

| TK532 | 5′-AATAACATCCATGACGCTGTC-3′ |

| TK860 | 5′-TAGGATCCCATTGTCTGTCGTTAAATTTAA-3′ |

| TK937 | 5′-CACGGATCCGTGATCTTTTCAAGAATAAT-3′ |

| TK938 | 5′-CACCTGCAGTTACAAGATTTGATAGTGCTC-3′ |

| TK962 | 5′-CACGCATGCGCGAACTAAAGCAACTAT-3′ |

| TK1052 | 5′-CACGCATGCTTCTGAGTGGTTTCGTTC-3′ |

| TK1053 | 5′-CACCTCGAGCATTGAAATCCAAACCGT-3′ |

| TK1078 | 5′-CACGCATGCGGAATTTGGCGCCGGGTC-3′ |

| TK1105 | 5′-CACGCATGCCCACAAGGAAAAAGGAAA-3′ |

| TK1130 | 5′-CACGAATTCCATAACAATTCGTCGAGA-3′ |

| TK1131 | 5′-CACCTGCAGCTATTGACCTCTTAATTC-3′ |

| TK1136 | 5′-CACACTAGTCAGATCCGCCAGGCGTGT-3′ |

| TK1137 | 5′-CACCTCGAGCCTTATGTGGGCCACCCT-3′ |

| TK1165 | 5′-ATGTCACGATCCCTTTTGGTA-3′ |

| TK1166 | 5′-AGTCGAATTCGTATGAAAAGA-3′ |

| TK1167 | 5′-ATGTCCAACCCAATAGAAAAC-3′ |

| TK1168 | 5′-TTGCAGGCAGCTCAGCTCTCC-3′ |

| TK1169 | 5′-ATGGCTGAACTGAGCGAACAA-3′ |

| TK1170 | 5′-CATCGTAGTTATCGAAGTTAA-3′ |

| TK1186 | 5′-ATGTCTATCCCAGAAACTCAA-3′ |

| TK1187 | 5′-GGTGTAACCAGACAAGTCAGC-3′ |

| TK1188 | 5′-ATGGGAGAGAACCACGACCAT-3′ |

| TK1189 | 5′-TTCACTATCGAAGCAGCATCA-3′ |

| TK1194 | 5′-ATGGCCATATTGAAGGATACC-3′ |

| TK1195 | 5′-GTCTTGTGTGACAGTACATGA-3′ |

| TK1224 | 5′-ATGTCTTTATCTTCAAAGTT-3′ |

| TK1225 | 5′-TCGATGTGGTAACGCAAGTT-3′ |

| TK1231 | 5′-GCTAAAGTTCATGGTTCTCTA-3′ |

| TK1232 | 5′-TTATTGGACGGATGGACCTGG-3′ |

| T844 | 5′-CACACAGGATCCGTACCAACTTGGCCAACGAAGAT-3′ |

Yeast strains, genetic analyses, and isolation of conditional alleles.

Standard techniques were used for yeast growth and transformation (2, 28). Yeast strains were derived from Y22.1, which carries a deletion of the chromosomal yTAF145 coding region and the wild-type yTAF145 gene on a URA3-based low-copy-number vector (41). To isolate conditional alleles of yTAF145 from the randomly mutated plasmid library, a plasmid shuffling technique was used (7). 5-Fluoroorotic acid-resistant colonies harboring mutant yTAF145 genes on plasmids derived from pM34 were incubated on synthetic dextrose (SD) plates for 3 days at 30 or 37°C to compare their growth properties. Plasmid DNA was isolated from candidate TS clones and retransformed to confirm the plasmid linkage of the TS phenotype. The BglII/EcoRI (464-bp) and EcoRI/BstEII (380-bp) fragments of pM34 (wild type), which between them contain the entire sequence of region III (Fig. 1A), were individually replaced with the corresponding regions of candidate plasmids to determine which fragment conferred the TS phenotype. The amino acid residue(s) responsible for the TS phenotype was finally determined by sequencing and site-directed mutagenesis (49). Yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Y22.1 | MATα ura3-52 trp1-63 leu2,3-112 Δtaf145 pYN1/TAF145 | T. Kokubo et al. (41) |

| YTK3002 | MATα ura3-52 trp1-63 leu2,3-112 Δtaf145 pTM25/TAF145 (Y570N) | This study |

| YTK3003 | MATα ura3-52 trp1-63 leu2,3-112 Δtaf145 pTM32/TAF145 (N568Δ) | This study |

| YTK3005 | MATα ura3-52 trp1-63 leu2,3-112 Δtaf145 pTM43/TAF145 (T657K) | This study |

| Z676 | MATa ura3-52 his3-200 leu2,3-112 rpb1Δ187::HIS3 RY2522/rpb1-1 | C. M. Thompson and R. A. Young (92) |

| Z294 | MATa ura3-52 his3-200 leu2,3-112 rpb1Δ187::HIS3 pRP112/RPB1 | C. M. Thompson and R. A. Young (92) |

Plasmids encoding conditional alleles of yTAF145 gene.

pM34 was subjected to site-specific mutagenesis (49) to recreate the conditional yTAF145 alleles. Oligonucleotides TK175, TK176, and TK178 were used to generate the plasmids pTM25 (Y570N), pTM32 (N568Δ), and pTM43 (T657K), respectively.

Construction of mini-CLN2 hybrid reporter gene.

For construction of mini-CLN2 reporter plasmids, the parental plasmid encoding CLN2 was obtained by screening yeast genomic libraries. pM1450 was constructed by ligating the 2.8-kb SphI/XbaI fragment including the entire CLN2 gene from the parental plasmid into the SphI/XbaI sites of YEplac181 (25). pM1451 was constructed by exchanging the PvuII fragment of pRS315 (86) with the PvuII fragment from pM1450, which included the CLN2 gene, to enable site-directed mutagenesis (49). pM1452 was created by digesting pM1451 with SpeI and NcoI to remove a 1,047-bp internal fragment from the CLN2 ORF, blunt ending the linearized vector, and religating (pM1452 is shown as ΔCLN2 in Fig. 4A). pM1453 was constructed by ligating a 216-bp SphI fragment containing the UAS of CLN2 into the SphI site of pM1452 (pM1453 is shown as UASCLN2+ΔCLN2 in Fig. 4A); the UAS-containing fragment was amplified by PCR using primers TK962 and TK860.

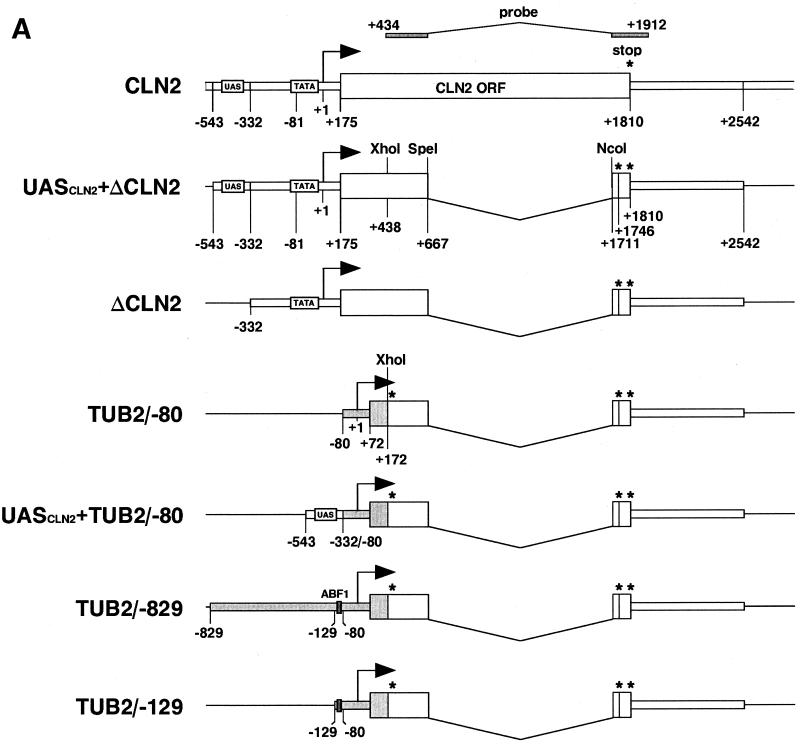

FIG. 4.

A novel mini-CLN2 hybrid gene reporter system. (A) Schematic representation of the reporter plasmids used in this experiment. The positions of the TATA element, transcriptional initiation site, ORF of the CLN2 gene, and probe for Northern analysis are shown in the top row. The ΔCLN2 reporter construct was generated by removing an internal SpeI/NcoI fragment from the intact CLN2 gene. Asterisks denote the positions of translational stop codons that were created during the construction process. Arrows indicate the initiation site and direction of transcription. Sequences derived from the TUB2 gene are shaded. (B to D) Northern blot analysis of mRNA with a CLN2-specific probe to test the validity of the reporter system. Wild-type (B to D) or T657K mutant (D) yeast into which the indicated reporter plasmids had been introduced were cultured at 25°C (B to D) or 37°C (D) as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Total RNA isolated from these cultures was analyzed by Northern blotting with a radioactive CLN2-specific probe shown in panel A. The upper band, marked with a black-and-white arrow, corresponds to mRNA derived from the endogenous CLN2 gene, whereas the lower band, marked with a solid black arrow, corresponds to mRNA derived from the mini-CLN2 gene on the reporter plasmid. (E and F) Northern blot analysis of mRNA with a CLN2-specific probe to delineate the region that confers yTAF145 dependence on the TUB2 promoter. Wild-type or mutant strains carrying the indicated reporter plasmids were cultured at 25 or 37°C. Total RNA isolated from these cultures was analyzed as described above.

For deletion analysis of the TUB2 promoter region, pM1583, pM1525, and pM1464 were constructed by replacing the 765-bp SphI/XhoI fragment of pM1452 (encompassing the CLN2 promoter) with DNA fragments encoding the −80∼+172 (fragment from −80 to +172), −129∼+172, and −829∼+172 fragments of the TUB2 promoter, respectively; these fragments were amplified by PCR using the primer pairs, TK1105 and TK1053, TK1078 and TK1053, and TK1052 and TK1053, respectively. pM1584 was constructed by ligating the 216-bp SphI fragment containing the UAS of the CLN2 gene from pM1453 into the SphI site of pM1583.

pM1586 was created by ligating four repeats of the GAL4 binding site, constructed by annealing two oligodeoxynucleotides, TK521 and TK522, into the SpeI site of pM1585 (which was constructed from pM1584 by linker insertion at the SphI site). The PvuII fragment of pM1586 containing the entire reporter gene was moved into pRS316 (86) to change the auxotrophic marker from LEU2 to URA3. The resulting plasmid pM1587 is shown as UASGAL+TUB2/−80 in Fig. 5A. pM1591 was created by replacing the 770-bp SpeI/XhoI fragment of pM1587 encompassing the TUB2 promoter with a DNA fragment encompassing the CYC1 promoter; the latter fragment was amplified as an SpeI/XhoI fragment by PCR with the primers TK1136 and TK1137 (pM1591 is shown as UASGAL+CYC1/−174 in Fig. 5A).

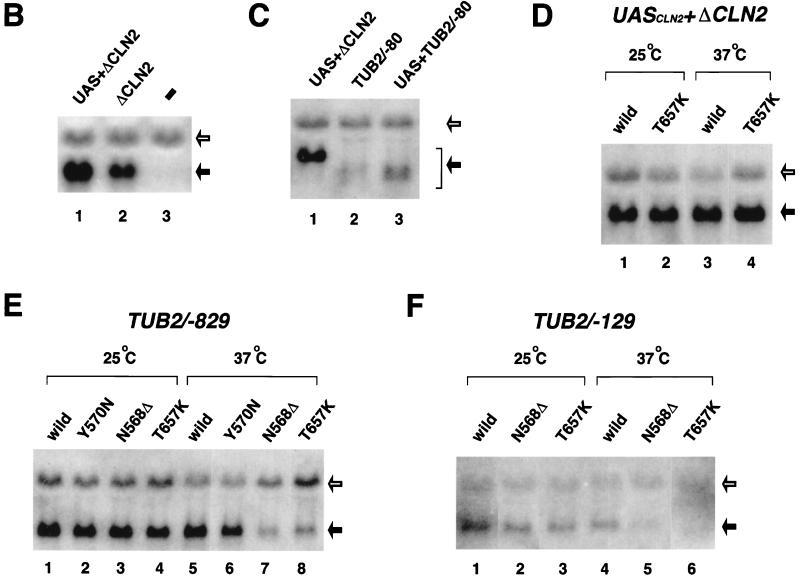

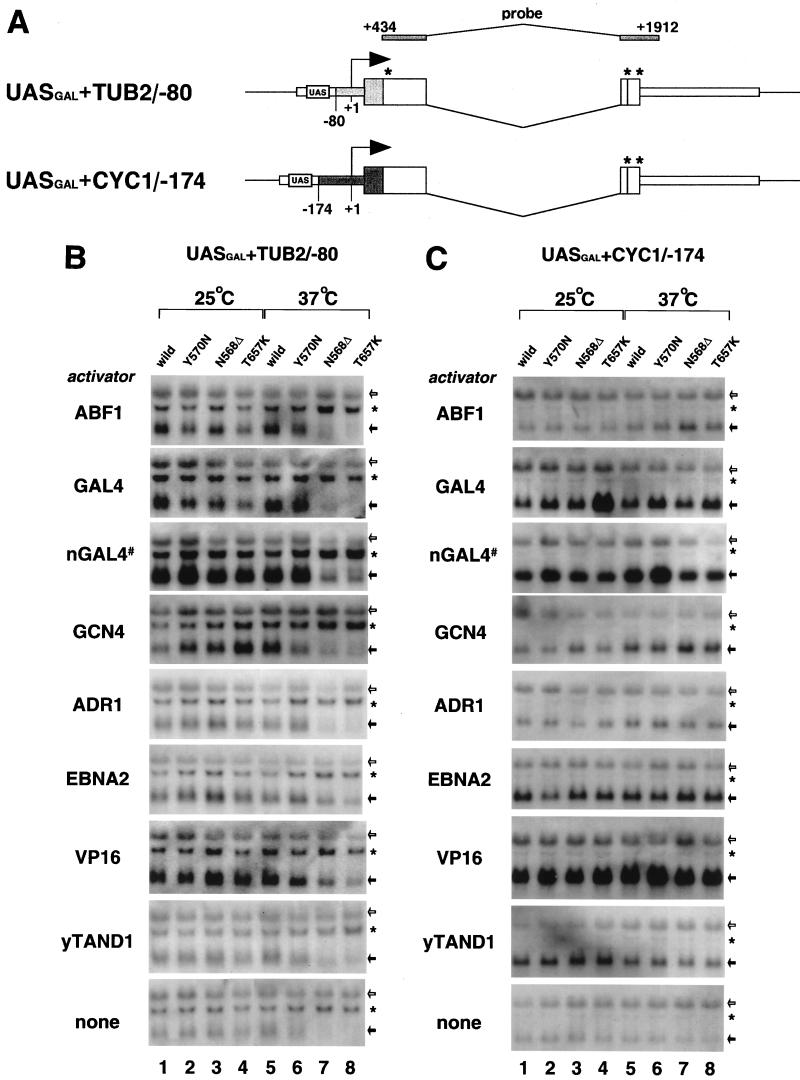

FIG. 5.

Promoter-specific transcriptional defects cannot be overcome by activators. (A) Schematic representation of the reporter plasmids used in this experiment. Synthetic binding sites for GAL4 fusion activators were linked upstream of the TUB2 and CYC1 promoters to generate UASGAL+TUB2/−80 and UASGAL+CYC1/−174 reporter plasmids, respectively. Other symbols are as described in the legend to Fig. 4A. (B) Northern blot analysis of mRNA with a CLN2-specific probe. Wild-type or TS mutant strains into which UASGAL+TUB2/−80 and activator expression plasmids had been introduced were cultured at 25 or 37°C as described in the legend to Fig. 2, except for nGAL4# (see below). Total RNA isolated from these cultures was analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 4B to F. Upper and lower bands marked with arrows are as described in the legend to Fig. 4. The middle band marked with an asterisk corresponds to transcripts presumably initiated from an unknown cryptic promoter on the reporter plasmid. Note that transcription from the putative cryptic promoter was not affected in our mutants. nGAL4# shows the results of activation by the endogenous GAL4 activator. Cells cultured in medium containing galactose instead of glucose were shifted from 25 to 37°C to show this effect. (C) All experiments were performed as described above for panel B, except that the UASGAL+CYC1/−174 reporter plasmid instead of UASGAL+TUB2/−80 was used.

Plasmids encoding activation domains fused with the GAL4 DNA binding domain.

pM471 was constructed by replacing the 1,240-bp SphI fragment of pGAD424 (Clontech) that contains the GAL4 activation domain, expression of which is regulated by an ADH1 promoter and terminator, with the corresponding 1,094-bp SphI fragment from pGBT9 (Clontech) that contains the GAL4 DNA binding domain under the control of the same regulatory sequences. For expression of various activators in yeast cells, pM1594, pM1569, pM967, pM1440, pM1570, pM524, and pM468 were constructed by ligating DNA fragments encoding ABF1 (aa 600 to 731), GAL4 (aa 842 to 874), GCN4 (aa 107 to 144), ADR1 (aa 642 to 704), EBNA2 (aa 426 to 462), VP16 (aa 457 to 490), and yTANDI (aa 10 to 42) activation domains, respectively, into pM471. The activation domains were amplified by PCR using the primer pairs TK1130 and TK1131, TK212 and TK213, TK208 and TK209, TK937 and TK938, TK184 and TK185, TK189 and TK187, and T844 and TK202, respectively.

Northern and slot blot analyses.

Cells were grown to log phase at 25°C, a portion of each culture was shifted to 37°C, and incubation was continued for 2 h. Cell density was determined, and equal numbers of cells were harvested from 25 and 37°C cultures. Total RNA was isolated as described previously (37). Briefly, cells were washed once in water, resuspended in 400 μl of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]), mixed with 400 μl of unbuffered phenol by vortexing, and then incubated at 65°C for 1 h. The tubes were placed on ice for 10 min and centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min. The aqueous phase was reextracted with phenol-chloroform and then precipitated with ethanol. RNA pellets were washed with 70% ethanol and resuspended in water. DNA was removed by treatment with RNase-free DNase (Boehringer Mannheim) at 37°C for 1 h. For Northern analysis, total RNA (20 μg) was resolved on 1% denaturing agarose gels, transferred to GeneScreen Plus (NEN Research Products) membranes according to the manufacturer's instructions, and fixed to the membranes by UV cross-linking using a Stratalinker (Stratagene). Blots were hybridized overnight at 42°C with the appropriate radioactive probes in a buffer containing 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), 50% formamide, 5× Denhardt's solution, 0.5% SDS, and 0.2 mg of salmon sperm DNA per ml. The hybridized blots were washed three times in 1× SSC buffer at 65°C for 15 min and then autoradiographed.

Slot blot analysis was performed as described previously (48). Total RNA (2 μg in 1 μl) was incubated with 30 μl of denaturing solution (17.5 μl of formamide, 2 μl of formaldehyde, 1.75 μl of 10× morpholinepropanesulfonic acid [MOPS] buffer [0.2 M MOPS {pH 7.0}, 50 mM sodium acetate, 10 mM EDTA] 8.75 μl of deionized water) at 60°C for 15 min and then placed on ice. Cold Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (35 μl) was added to each sample, and the samples were applied to GeneScreen Plus (NEN Research Products) nylon membranes using a Bio-Dot microfiltration apparatus (Bio-Rad). The samples were washed twice with 2× SSC buffer, and RNA was fixed to the membranes by UV cross-linking. The blots were hybridized overnight at 37°C with a radioactive poly(dT) probe in a buffer containing 4× SSC, 10× Denhardt's solution, 0.5% SDS, and 0.1 mg of salmon sperm DNA per ml. The hybridized blots were washed several times with 1× SSC at 37°C for 10 min and then autoradiographed.

Probes for RNA analyses.

For Northern blot analysis of endogenous genes, DNA fragments surrounding the initiating methionine were amplified by PCR from yeast genomic DNA, purified, and 32P labeled using a random priming method. The PCR primers used were as follows: TK249 and TK250 for ACT1, TK1186 and TK1187 for ADH1, TK1224 and TK1225 for PGK1, TK1169 and TK1170 for DED1, TK489 and TK490 for CLN1, TK491 and TK492 for CLN2, TK1194 and TK1195 for CLN3, TK1165 and TK1166 for CLB1, TK1167 and TK1168 for CLB2, TK1188 and TK1189 for CLB5, TK531 and TK532 for TUB2, TK477 and TK478 for RPL32, TK1231 and TK1232 for RPS30, and TK493 and TK494 for RPS5.

For detection of mRNA derived from mini-CLN2 hybrid gene reporter constructs, the 411-bp XhoI/HindIII fragment was isolated from pM1452 and 32P labeled by random priming.

The poly(dT) probe was 32P labeled by incubating 50 ng of poly(rA)/poly(dT)12–18 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), 4 μl of 5× first-strand synthesis buffer (GIBCO BRL), 1 μl of 100 mM dithiothreitol, 1 μl of [α-32P]dTTP (400 Ci/mmol) and 1 μl (200 U) of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (GIBCO BRL), in a final volume of 20 μl at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction mixture was incubated at 70°C for 15 min, and then 80 μl of TE buffer was added. Unincorporated nucleotides were removed with a Sephadex G50 spin column.

Antibodies, immunoblot, and coimmunoprecipitation analyses.

Polyclonal antibodies directed against yTAF61 were raised in rabbits using a recombinant His-tagged yTAF61 polypeptide (aa 1 to 360), expressed in bacteria, and gel purified as an antigen. Polyclonal antibodies against yTAF145 and TBP were described previously (47).

Immunoblot and coimmunoprecipitation analyses were performed as described previously (47).

RESULTS

Isolation of yTAF145 conditional alleles.

It has been demonstrated that yTAF145 is not required for transcription of most genes (63, 98), but is essential for a subset of genes such as G1 or B-type cyclins and ribosomal proteins (84, 99). Interestingly, the sequences that confer yTAF145 dependency were mapped to the core promoter rather than UAS in these genes (84). More recently, genome-wide expression analysis using DNA microchip technology showed that the levels of mRNAs representing only about a third of the 5,441 genes analyzed are reduced by twofold or greater within 45 min after temperature shift in a TS yTAF145 mutant (34). Importantly, however, these observations were obtained using a limited number of conditional mutants that were originally isolated by S. S. Walker and colleagues (ts1 and ts2) (98). On the other hand, yTAF145 has been shown to possess multiple functions, including TAND (TAF N-terminal domain) activity, which negatively regulates TBP function (3, 41, 47), and HAT activity (62), both of which are thought to be involved in certain aspects of transcription. Thus, we believe that there remains a good chance of isolating additional yTA145 conditional alleles which affect transcription in different ways from ts1 and ts2 (98), by conducting more extensive screening.

To isolate conditional alleles showing a wide variety of phenotypes, we divided the entire yTAF145 ORF into four regions separated by unique restriction sites, each of which could be replaced with a corresponding PCR-amplified DNA fragment by digesting with the appropriate restriction enzymes and religating (Fig. 1A). In this study, we used error-prone PCR (12) to introduce random mutations into the most highly conserved section of yTAF145, region III, which overlaps the HAT domain. Three conditional alleles (plasmids 2, 50, and 51) were isolated from the mutated library by plasmid shuffling (7) and growth rate screening. Sequence analysis showed that plasmids 2 and 51 each contained two mutations in the yTAF145 ORF, encoding the amino acid changes N568Δ (deletion of N568) and R580G in plasmid 2 and K559I and Y570N in plasmid 51, while plasmid 50 had just one mutation site (encoding the amino acid change T657K). Single residue substitution or truncation by site-directed mutagenesis (49) demonstrated that the N568Δ, Y570N, and T657K mutations are chiefly responsible for the TS phenotypes of mutants 2, 51 and 50, respectively. The growth phenotypes of cells carrying wild-type or singly mutated alleles (Y570N, N568Δ, and T657K) at permissive (30°C) and nonpermissive (37°C) temperatures are shown in Fig. 1B. Note that the Y570N allele displayed a weaker TS phenotype than the others.

Transcription of a subset of genes is specifically reduced at restrictive temperatures.

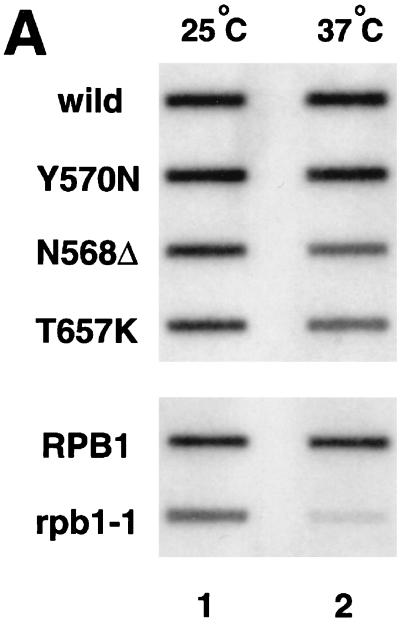

To test the specificity of the effects of these TS alleles on gene expression in vivo, total RNA was isolated from wild-type and mutant strains harvested 2 h after a temperature shift to 37°C and analyzed by slot blotting (Fig. 2A) and Northern blotting (Fig. 2B). Slot blot analysis using an oligo[d(T)] probe measured levels of poly(A)+ RNA in these mutants. The results were consistent with those of previous studies (99) and showed that there was no substantial reduction in the synthesis of poly(A)+ RNA in these mutants. However, careful inspection revealed that the N568Δ and T657K mutations caused slight decreases in total poly(A)+ RNA levels, although the reduction was much smaller than that induced by rpb1-1, a mutation of the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (92).

FIG. 2.

Transcription of a subset of genes is affected in TS mutants. (A) Total poly(A)+ RNA levels in strains carrying wild-type or mutant (Y570N, N568Δ, and T657K) alleles of yTAF145 (top gel) or a mutation in the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (bottom gel). Total RNA was isolated from wild-type or mutant strains 2 h after temperature shift to 37°C (lane 2) or continuously incubated at 25°C over the same time period (lane 1) and slot blotted for hybridization with a radioactive oligo(dT) probe. (B) Northern blotting analysis of specific mRNAs in wild-type (lanes 1 and 5) and TS mutant strains (lanes 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8). Total RNA isolated as described above was blotted to a nylon membrane and hybridized with the probes indicated.

To examine gene-specific transcriptional defects in these mutants, the expression levels of several genes were tested by Northern blot analysis 2 h after the temperature shift (Fig. 2B). The results were again consistent with previous studies (84, 99) and showed that mRNA levels of the RPS5, RPS30, and CLB5 genes were significantly reduced in the N568Δ and T657K mutants and slightly reduced in the Y570N mutant. These observations, together with the slot blot analysis results discussed above, suggest that N568Δ and T657K produce more severe defects than Y570N. Interestingly, CLN2 mRNA was expressed at the wild-type level in our mutants, in stark contrast to the ts2 mutant in which it is almost undetectable at 37°C (84, 99). In addition, the N568Δ and T657K mutations significantly affected transcription of mRNAs encoding CLB1, CLB2, TUB2, and RPL32 and partially reduced transcription of ACT1, DED1, CLN1, and CLN3 but had no effect on ADH1 or PGK1. Therefore, these novel conditional mutants exhibit gene expression profiles which are distinct from that of the ts2 mutant (84, 99), suggesting that different yTAF145 functions might be affected in our mutants.

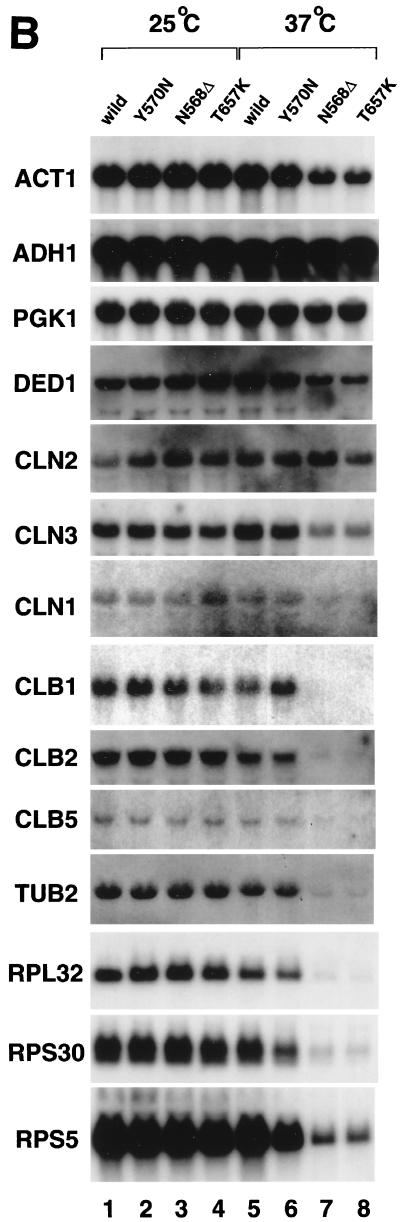

Expression of yTAF145 mutant proteins and stability of the TFIID complex.

Expression of mutant alleles under nonpermissive conditions was monitored by immunoblotting (Fig. 3A). The yTAF145 mutant proteins (Y570N, N568Δ, and T657K) were stably expressed for at least 4 h after the temperature shift to 37°C, after which the levels of these proteins gradually declined. This is another distinctive feature of our mutant alleles, since ts1 and ts2 mutant proteins were reported to be rapidly degraded and almost undetectable 2 h after the temperature shift to 37°C (98).

FIG. 3.

yTAF145 protein levels and integrity of the TFIID complex in TS mutants. (A) Whole-cell extracts (WCE) were prepared by sonication (47) from wild-type and TS mutant cells harvested from cultures grown at 37°C for the indicated time. Total WCE proteins were fractionated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with anti-yTAF145 polyclonal antibodies. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation analysis to test the integrity of the TFIID complex. WCE were prepared using glass beads (47) from wild-type and TS mutant cells cultured 2 h after temperature shift to 37°C (lanes 5 to 8 and 13 to 16) or continuously incubated at 25°C over the same time period (lanes 1 to 4 and 9 to 12). Aliquots of WCE proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-TBP (α-TBP) polyclonal antibodies. Proteins coprecipitating with TBP were fractionated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with the indicated polyclonal antibodies. The loading control (left gels) represents 5% of the input in the immunoprecipitation (IP) lanes (right gels). Note that the amount of total TS yTAF145 proteins was reduced more than the TS yTAF145 that coimmunoprecipitates with TBP. This may suggest that the TS yTAF145 assembled into a TFIID complex before the temperature shift is more stable than TS yTAF145 synthesized after the temperature shift.

To test the integrity of the TFIID protein complex, coimmunoprecipitation analysis was performed with anti-TBP polyclonal antibodies using whole-cell extracts prepared from wild-type and mutant strains (Fig. 3B) (3, 47). Similar amounts of yTAF145 and yTAF61 polypeptides were detected in the complex coprecipitated with TBP from both wild-type and mutant cell lysates, even under nonpermissive conditions. This suggests that the overall structure, including subunit composition and stoichiometry, of TFIID which contains yTAF145 mutant proteins may not be greatly affected by the mutations. However, given that transcriptional defects were clearly observed under the same conditions (Fig. 2B), mutant TFIID does appear to be defective in some specific but as-yet-unidentified function, such as the ability to undergo conformational change in response to activators and/or core promoter elements. In any case, the apparent structural integrity of TFIID once again distinguishes our mutants from ts1 and ts2, in which TFIID was altered in its subunit stoichiometry (98). This may explain why transcription of the CLN2 gene was inhibited in the ts2 mutant (98) but not in our mutants (Fig. 2B).

A novel reporter system using the mini-CLN2 hybrid gene.

The observation that our yTAF145 mutations affected transcription of TUB2 but not CLN2 prompted us to develop a novel reporter system to delineate the regions of the TUB2 promoter that are responsible for yTAF145 dependency. We used a portion of the CLN2 gene as a reporter, instead of the commonly used lacZ gene (84), so that a single probe could monitor the expression of reporter constructs and endogenous CLN2 simultaneously. Since the latter was not affected by our yTAF145 mutations, it could be used as an internal standard. To distinguish reporter gene mRNAs from those derived from the endogenous CLN2 gene, we shortened the CLN2 gene in the reporter plasmid by removing an internal SpeI/NcoI fragment (Fig. 4A). Since the deleted fragment encodes one of the essential α-helixes of the cyclin box (helix 5), the mini-CLN2 reporter constructs could be expected to produce nonfunctional (i.e., nontoxic) CLN2 proteins (35). Indeed, the mini-CLN2 gene driven by various promoters at different expression levels did not affect the growth rates of host yeast cells in any of our experiments (data not shown).

The mini-CLN2 gene directed by the CLN2 core promoter with (UASCLN2+ΔCLN2) or without (ΔCLN2) UAS (84) was introduced into yeast on a low-copy-number plasmid. Transcription of the mini-CLN2 gene on these reporter plasmids was monitored by Northern blot analysis using a CLN2-specific probe (Fig. 4B). As expected, two specific bands were detected, corresponding to mRNAs derived from endogenous CLN2 and from the mini-CLN2 reporter gene. Expression of the lower mini-CLN2 band was not detected when cells were transformed with the empty vector plasmid and was enhanced by UASCLN2 function.

We then tested whether this reporter system could be used to analyze the function of heterologous promoters. The core promoter of the TUB2 gene, including 100 bp of the coding region, was fused to the mini-CLN2 gene (TUB2/−80) and this construct was assayed for transcription in yeast cells (Fig. 4C). The band derived from TUB2/−80 migrated at the expected size relative to the UASCLN2+ΔCLN2 signal. Like the CLN2 core promoter, the TUB2 core promoter was also augmented by UASCLN2 (UASCLN2+TUB2/−80). These results indicate that the mini-CLN2 hybrid gene reporter system is a useful and convenient tool for analysis of heterologous promoter function, especially in our yTAF145 mutants.

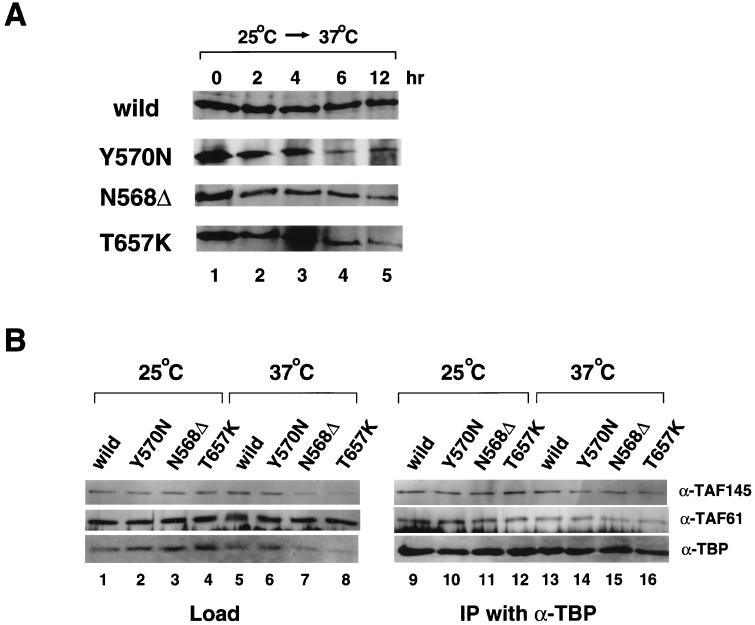

Impaired transcription of reporter constructs driven by TUB2 promoter.

Next, we wished to test whether gene-specific transcriptional defects could be reproduced in a plasmid background. We compared the functions of CLN2 and TUB2 promoters in wild-type and our mutant strains by using the mini-CLN2 hybrid gene reporter system. As expected, the CLN2 promoter (UASCLN2+ΔCLN) mediated efficient transcription under all conditions (Fig. 4D). In contrast, the TUB2 promoter (TUB2/−829) containing 829 bp upstream of the initiation site (Fig. 4A) (30) did not function normally in N568Δ or T657K mutants under nonpermissive conditions (Fig. 4E). Transcription of the endogenous CLN2 gene was normal in both of these mutants. These results demonstrate that the mini-CLN2 reporter system can produce gene-specific transcriptional defects originally observed in the chromosomal context. We therefore employed this system to delineate the sequences that confer yTAF145 dependency on the TUB2 promoter in N568Δ and T657K mutants.

We tested two other reporter plasmids, TUB2/−129 and TUB2/−80, that contained different portions of the TUB2 promoter (Fig. 4A). The TUB2/−129 insert contains the binding site for ABF1, which is important for constitutive expression of TUB2 (30), whereas the TUB2/−80 insert lacks this site. Transcription of both of these plasmids was similar to that of TUB2/−829 (Fig. 4G and 5B). It therefore appears that the core promoter, rather than UAS, of the TUB2 gene renders its expression yTAF145 dependent in our mutants, as was reported for the CLN2 promoter in the ts2 mutant (84).

Activators do not overcome transcriptional defects of TUB2 promoter in yTAF145 mutants.

The results presented above indicate that the TUB2 core promoter is not recognized in the normal fashion by TFIID containing N568Δ or T657K mutant subunits. Furthermore, ABF1, a transcription factor that regulates TUB2 gene expression in vivo (30), does not overcome such transcriptional defects, since transcription of TUB2/−829, TUB2/−129, and TUB2/−80 reporter plasmids were comparably damaged (Fig. 4; also data not shown). However, it has been demonstrated that activator function depends on core promoter structures; for example, GAL4-VP16 requires the TATA element much more strongly than GAL4-Sp1 (22). In addition, there are several classes of activator which target different basal factors so as to stimulate different steps in transcription (6). We therefore tested a number of different activators for their ability to overcome the transcriptional defects in our mutants (Fig. 5). To measure the activator effects in the same background, we fused each activation domain (ABF1 [52], GAL4 [60], GCN4 [19], ADR1 [45], EBNA2 [15], VP16 [77], and yTAND1 [47]) to the GAL4 DNA binding domain, which binds to the multiple recognition sites linked to the TUB2 or CYC1 promoter in the mini-CLN2 reporter plasmids (UASGAL+TUB2/−80 and UASGAL+CYC1/−174, respectively, in Fig. 5A). In this experiment, UASGAL+CYC1/−174 functions as a control, since transcription driven by the CYC1 promoter was not affected in our mutants (Fig. 5C). We introduced effector and reporter plasmids together into wild-type or mutant strains and measured transcription of the mini-CLN2 gene under permissive and nonpermissive conditions (Fig. 5B and C). GAL4 and VP16 activated both promoters strongly, while the other activators displayed some preference for one promoter over the other. For instance, ABF1 activated the TUB2 promoter more strongly than the CYC1 promoter, but yTAND1 activated the CYC1 promoter more strongly than the TUB2 promoter. As expected, transcription driven by the CYC1 promoter was not affected by yTAF145 mutations under any conditions. However, all of the activators we tested failed to support normal levels of activated transcription from the TUB2 promoter at 37°C in N568Δ and T657K mutants (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that transcriptional activators cannot overcome the transcriptional defects in our mutants. Notably, TADIV of ADR1 activated transcription from the CYC1 promoter even under nonpermissive conditions in our mutants (Fig. 5C). In contrast, ADR1 TADIV displayed more than fourfold reduction in activation of transcription driven by the GAL1 promoter, even under permissive conditions, in the ts1 mutant (45). It has yet to be determined whether this discrepancy is due to the different core promoters (i.e., CYC1 versus GAL1) or directly caused by the yTAF145 mutations.

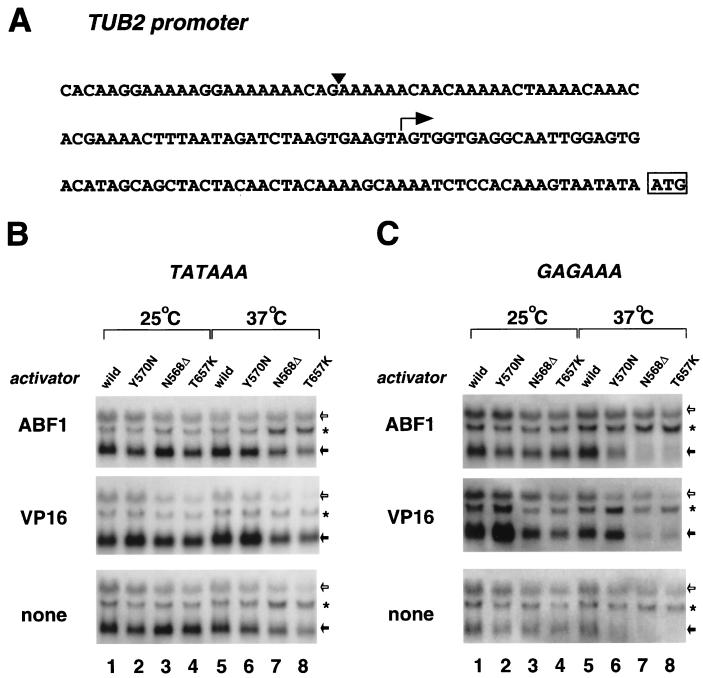

TATA element restores impaired transcription driven by TUB2 core promoter.

Previous double-shutoff experiments showed that, following in vivo depletion of yTAF145 protein, the TRP3 and HIS3 (+1) promoters ceased transcription much faster than the DED1 and HIS3 (+13) promoters (63). Since canonical TATA elements were found in the latter but not in the former promoters, it was suggested that a nonconsensus TATA element may be the determinant of yTAF145 dependency (63). However, more recent experiments delineating the region that confers yTAF145 dependency on the RPS5 promoter revealed that it overlaps with but does not consist entirely of the nonconsensus TATA element (84).

We examined the transcription levels of several endogenous genes in our mutants (Fig. 2B). While not all of these promoters are well characterized, we noticed a tendency for the affected genes to be driven by promoters lacking a canonical TATA element. For instance, the ADH1 (94), PGK1 (70), DED1 (87), and CLN2 (89) promoters, all of which contain canonical TATA elements, were much less affected by the yTAF145 mutations than the TUB2 (30), RPS30 (4), and RPS5 (85) promoters, which lack TATA elements. The ACT1 promoter was an exception, being somewhat affected even though it lacks the consensus TATA element (59); this is probably because ACT1 mRNA is quite stable, having a half-life greater than 25 min (32).

To verify directly whether the nonconsensus TATA element was a major determinant of yTAF145 dependency in our mutants, we created a canonical TATA element (TATAAA) at a position −55 bp from the initiation site of the TUB2 promoter in the mini-CLN2 reporter plasmid UASGAL+TUB2/−80. The modified reporter plasmid was introduced into wild-type and mutant yeast strains and tested for basal and activated transcription under permissive and nonpermissive conditions (Fig. 6A). The canonical TATA element partially but reproducibly restored transcription driven by the TUB2 promoter in N568Δ and T657K mutants at 37°C. Importantly, a nonspecific GAGA sequence similarly created at the same position did not restore the impaired transcription (Fig. 6B), indicating that the rescue effect was sequence specific. It appears that strong interaction between TBP and a canonical TATA element can partially compensate for the impaired function of yTAF145 protein in our mutants. This is yet another respect in which our mutants differ from the ts2 mutant (84).

FIG. 6.

Impaired transcription directed by the TUB2 promoter is restored by insertion of a canonical TATA element. (A) Nucleotide sequence of the TUB2 promoter. The initiating methionine is shown boxed, and the transcriptional start site is indicated by the arrow. (B) The canonical TATA element sequence TATAAA was created at the −55 bp position of the UASGAL+TUB2/−80 reporter plasmid by inserting a TATAT sequence between the G and A nucleotides marked with an inverted black triangle in panel A. (C) As a negative control, a GAGAAA sequence was also created at the same position by inserting a GAGAG sequence. Northern blotting analysis was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 5 but with these modified reporter plasmids in place of UASGAL+CYC1/−174 or UASGAL+TUB2/−80.

DISCUSSION

Novel conditional alleles, N568Δ and T657K, confer similar phenotypes.

In this study, we isolated three novel conditional alleles (Y570N, N568Δ, and T657K) of the yTAF145 gene. Several lines of evidence from analysis of transcription levels and growth rates suggested that N568Δ and T657K were more defective than Y570N (Fig. 1, 2, 4, and 5). The N568Δ and T657K mutants showed reduced growth rates even at 30°C and almost ceased to grow at 33°C, while the Y570N mutant grew well under the same conditions. More detailed analysis revealed that T657K causes a slightly stronger TS phenotype than N568Δ (data not shown).

N568Δ and T657K mutants displayed nearly the same transcriptional defects in our analyses (Fig. 2, 4, 5, and 6), suggesting that both mutations affect the same function of yTAF145. It has been clearly demonstrated that yTAF145 and its orthologs (e.g., dTAF230/250, hTAF250) carry out multiple functions, including TAND activity which negatively regulates TBP function (3, 41, 47), HAT activity (62), and serine/threonine kinase activity which autophosphorylates and transphosphorylates the large subunit of TFIIF (18). Only the HAT domain (62) overlaps with the mutation sites (Fig. 1), but it has yet to be determined whether our mutations affect HAT activity or other, as-yet-unknown functions. A dramatic loss of transcription caused by the yTAF17 or yTAF60 mutation was observed only when the conditional alleles were “tight” (61). Weaker or leaky alleles had much weaker effects on transcription even if they exhibited tight TS phenotypes on agar plates (61). Thus, Y570N might simply be a weaker allele that is slightly impaired in the same function as the two tighter alleles N568Δ and T657K. Alternatively, Y570N and N568Δ/T657K may be impaired in different yTAF145 functions. More extensive studies such as examination of genome-wide gene expression profiles will be required to clarify this point.

The novel conditional alleles reported here differ from ts1 and ts2.

Our conditional alleles, especially N568Δ and T657K, differ from previously reported yTAF145 alleles (98) in several respects. First, Y570N, N568Δ, and T657K mutant proteins are stably expressed for at least several hours after the shift to the restrictive temperature, and the structure of TFIID appears not to be strongly affected by our yTAF145 mutations (Fig. 2). In contrast, ts1 and ts2 mutant proteins were rapidly degraded within 1 h after the temperature shift and appeared to induce loss of some other TAFs (98), so that mutant TFIID containing ts1 or ts2 subunits would be expected to be present at very low levels, if at all, at the restrictive temperature.

Second, there was a striking difference in the impact of the various mutants on transcription of the endogenous CLN2 gene. In the ts2 mutant, transcription of CLN2 was dramatically reduced following inactivation of yTAF145 protein (99). However, in our mutants, transcription of the CLN2 gene was not affected, even under nonpermissive conditions under which the transcription of several other genes (e.g., B-type cyclin genes, ribosomal protein genes, and TUB2) was severely compromised (Fig. 2B). Since we did not investigate the expression profiles of an identical set of genes to those examined in earlier studies, it remains unclear whether the genes affected in our mutants are similarly affected in the ts2 mutant. However, it is clear that the N568Δ T657K and ts2 mutations impair the transcription of an overlappingly (ADH1, RPS5, RPS30, and CLB5) but not identical (CLN2) set of genes.

Third, another remarkable difference between the two sets of mutants is in the TATA dependency of transcription (Fig. 6). A previous study demonstrated that yTAF145 dependency was conferred on the CLN2, RPS5, and RPS30 genes by the core promoter sequence (84). Interestingly, the region downstream of the initiation site was not required for yTAF145-dependent transcription of the CLN2 gene (84). Furthermore, the determinant of yTAF145 dependency in the RPS5 gene was mapped to the region surrounding the nonconsensus TATA element (TAAAAT) but not the TAAAAT sequence itself. In our mutants, like ts2, the region of the TUB2 promoter responsible for yTAF145 dependency mapped to the core promoter rather than UAS (Fig. 4). Remarkably, however, the TUB2 core promoter could be converted into a yTAF145-independent (or less-dependent) promoter by creating a consensus TATA element upstream of the initiation site. It therefore appears that the absence of a canonical TATA sequence is one of the most important determinants of yTAF145 dependence in our mutants. However, further analysis of a range of core promoters would be essential to generalize such assumptions.

Function of yTAF145 protein in vivo.

There is still some controversy over the in vivo function of TAFs (reviewed in reference 29). At present, two classes of TAFs are recognized: TFIID-specific and -nonspecific TAFs, the latter being common to TFIID and SAGA (or homologous complexes, such as mammalian TFTC, PCAF complex, and STAGA) (reviewed in reference 88). Interestingly, it seems that the latter class of TAFs are more generally required for transcription than the former class. For instance, genome-wide transcription analysis showed that 67% of yeast genes displayed a significant dependence on yTAF17, whereas only 16% were dependent on yTAF145, as judged by comparing kinetics of total mRNA reduction for 45 min after temperature shift with that of the rpb1-1 mutant (34). There are several possible explanations for such biases in TAF requirements (reviewed in reference 29), of which the most likely is that TFIID and SAGA function redundantly in transcription. Specific malfunctions of TFIID (e.g., yTAF145 or yTAF67 mutations) (34, 61) or SAGA (e.g., GCN5 or SPT20 mutations) (29, 34) are much less detrimental to general transcription than disorders simultaneously affecting both TFIID and SAGA (e.g., yTAF61, yTAF60, yTAF17, or yTAF25 mutations) (1, 34, 61, 64, 67, 80). Indeed, such functional redundancy has been demonstrated between mammalian TFIID and TFTC, at least in in vitro transcription experiments (102). If this were the case, mutations of the TFIID-specific factor yTAF145 would be expected to abrogate TFIID-specific functions. Alternatively, the difference in TAF requirements for general transcription might be simply due to the difference of taf alleles that were tested, since TFIID-specific yTAF40 inactivation results in TFIID depletion (SAGA remains largely unaffected) and a rapid loss of PolII-driven transcription (46). However, it is still possible that yTAF40 might be shared by TFIID and other unknown and redundant transcription factor complex besides SAGA. In any case, it should be emphasized that without knowing the real kinetics of loss of TAF function in TFIID following the temperature shift, we cannot make any accurate interpretations regarding the requirement for TFIID function for transcription of genes where no effect was seen.

Although the intrinsic function of TFIID is not yet entirely revealed, accumulating in vitro evidence indicates that TFIID is involved in transcriptional activation and the recognition of core promoter elements, such as the TATA box, initiator sequences, and downstream promoter elements (reviewed in references 10 and 11). A limited number of in vivo experiments using conditional TAF knockout strains suggest that common TAFs are involved in activation (1, 67), whereas TFIID-specific TAFs are involved in both activation (45) and core promoter recognition (Fig. 4) (84). More extensive in vivo studies may clarify whether common TAFs are also involved in both aspects of TFIID function. In any case, it is clear that TFIID is widely but not universally required for activation as well as core promoter recognition in vivo.

Different yTAF145 conditional alleles have been shown to have different effects on transcription. ts1 mutants (98) were shown to be impaired in activation by TADIV of ADR1 (45), whereas ts2 mutants (98) showed a defect in recognition of the core promoter of the CLN2 gene (84). N568Δ and T657K mutants responded to TADIV of ADR1 and recognized the CLN2 promoter normally but failed to transcribe genes under the control of the TUB2 promoter unless a canonical TATA element was provided near the initiation site. It has yet to be determined whether these apparent differences are due to the mutation site per se or to the specific core promoter and activation domains tested.

TATA-dependent transcription in our mutants.

Recent experiments using DNA cross-linking–immunoprecipitation assays have shown that TBP binding to the promoter is stringently controlled in vivo and stimulated by concerted action of activators and RNA polymerase II holoenzyme (50, 53). Interestingly, TBP binding to the RPS5 promoter was specifically compromised in the ts1 mutant, suggesting that yTAF145 facilitates TBP binding in a promoter-specific manner (53). Given that the canonical TATA element failed to restore transcription driven by the RPS5 promoter in the ts2 mutant, it is likely that TBP alone cannot bind to the TATA element in vivo without the aid of yTAF145 and/or other TAFs that were codegraded under nonpermissive conditions (98). Consistent with this idea is the observation that mutations of TBP which removed most of the TAFs from TFIID also produced promoter-specific transcriptional defects (75). In N568Δ and T657K mutants, transcriptional defects were restored by creating a canonical TATA element (Fig. 6). It therefore appears that TBP can be positioned properly on a canonical TATA element even by yTAF145 mutant proteins. In other words, the molecular defects in our mutants are apparently confined to the yTAF145 function that supports TBP function on TATA-less promoters. In vivo DNA cross-linking–immunoprecipitation analysis will help to clarify this point.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. G. Hinnebusch, K. Kasahara, and Y. Nakatani for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank A. Kobayashi for yTAF61 antibodies and plasmids, T. Kotani and K. Kasahara for plasmids, and Richard A. Young for RPB1 and rpb1-1 yeast strains.

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan, the CREST Japan Science and Technology Corporation, the Uehara Memorial Foundation, the Asahi Glass Foundation, and the NOVARTIS Foundation (Japan) for the Promotion of Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apone L M, Virbasius C A, Holstege F C, Wang J, Young R A, Green M R. Broad, but not universal, transcriptional requirement for yTAFII17, a histone H3-like TAFII present in TFIID and SAGA. Mol Cell. 1998;2:653–661. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai Y, Perez G M, Beechem J M, Weil P A. Structure-function analysis of TAF130: identification and characterization of a high-affinity TATA-binding protein interaction domain in the N terminus of yeast TAFII130. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3081–3093. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker R T, Williamson N A, Wettenhall R. The yeast homolog of mammalian ribosomal protein S30 is expressed from a duplicated gene without a ubiquitin-like protein fusion sequence. Evolutionary implications. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13549–13555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjorklund S, Almouzni G, Davidson I, Nightingale K P, Weiss K. Global transcription regulators of eukaryotes. Cell. 1999;96:759–767. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80586-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blau J, Xiao H, McCracken S, O'Hare P, Greenblatt J, Bentley D. Three functional classes of transcriptional activation domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2044–2055. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boeke J D, Trueheart J, Natsoulis G, Fink G R. 5-Fluoroorotic acid as a selective agent in yeast molecular genetics. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:164–175. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brand M, Yamamoto K, Staub A, Tora L. Identification of TATA-binding protein-free TAFII-containing complex subunits suggests a role in nucleosome acetylation and signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18285–18289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buratowski S, Hahn S, Guarente L, Sharp P A. Five intermediate complexes in transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II. Cell. 1989;56:549–561. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90578-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke T W, Kadonaga J T. The downstream core promoter element, DPE, is conserved from Drosophila to humans and is recognized by TAFII60 of Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3020–3031. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burley S K, Roeder R G. Biochemistry and structural biology of transcription factor IID (TFIID) Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:769–799. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cadwell R C, Joyce G F. Randomization of genes by PCR mutagenesis. PCR Methods Appl. 1992;2:28–33. doi: 10.1101/gr.2.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chalkley G E, Verrijzer C P. DNA binding site selection by RNA polymerase II TAFs: a TAFII250-TAFII150 complex recognizes the initiator. EMBO J. 1999;18:4835–4845. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chi T, Carey M. Assembly of the isomerized TFIIA-TFIID-TATA ternary complex is necessary and sufficient for gene activation. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2540–2550. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen J I. A region of herpes simplex virus VP16 can substitute for a transforming domain of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8030–8034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conaway R C, Conaway J W. General transcription factors for RNA polymerase II. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1997;56:327–346. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)61009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denis C L, Ciriacy M, Young E T. A positive regulatory gene is required for accumulation of the functional messenger RNA for the glucose-repressible alcohol dehydrogenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Mol Biol. 1981;148:355–368. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dikstein R, Ruppert S, Tjian R. TAFII250 is a bipartite protein kinase that phosphorylates the base transcription factor RAP74. Cell. 1996;84:781–790. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drysdale C M, Duenas E, Jackson B M, Reusser U, Braus G H, Hinnebusch A G. The transcriptional activator GCN4 contains multiple activation domains that are critically dependent on hydrophobic amino acids. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1220–1233. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dynlacht B D, Hoey T, Tjian R. Isolation of coactivators associated with the TATA-binding protein that mediate transcriptional activation. Cell. 1991;66:563–576. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emami K H, Jain A, Smale S T. Mechanism of synergy between TATA and initiator: synergistic binding of TFIID following a putative TFIIA-induced isomerization. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3007–3019. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emami K H, Navarre W W, Smale S T. Core promoter specificities of the Sp1 and VP16 transcriptional activation domains. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5906–5916. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flores O, Lu H, Reinberg D. Factors involved in specific transcription by mammalian RNA polymerase II. Identification and characterization of factor IIH. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2786–2793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fondell J D, Guermah M, Malik S, Roeder R G. Thyroid hormone receptor-associated proteins and general positive cofactors mediate thyroid hormone receptor function in the absence of the TATA box-binding protein-associated factors of TFIID. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1959–1964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gietz R D, Sugino A. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant P A, Schieltz D, Pray-Grant M G, Steger D J, Reese J C, Yates III J R, Workman J L. A subset of TAFIIs are integral components of the SAGA complex required for nucleosome acetylation and transcriptional stimulation. Cell. 1998;94:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grant P A, Sterner D E, Duggan L J, Workman J L, Berger S L. The SAGA unfolds: convergence of transcription regulators in chromatin-modifying complexes. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:193–197. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guthrie C, Fink G R, editors. Methods in Enzymology. 194. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hahn S. The role of TAFs in RNA polymerase II transcription. Cell. 1998;95:579–582. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81625-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halfter H, Muller U, Winnacker E L, Gallwitz D. Isolation and DNA-binding characteristics of a protein involved in transcription activation of two divergently transcribed, essential yeast genes. EMBO J. 1989;8:3029–3037. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayashida T, Sekiguchi T, Noguchi E, Sunamoto H, Ohba T, Nishimoto T. The CCG1/TAFII250 gene is mutated in thermosensitive G1 mutants of the BHK21 cell line derived from golden hamster. Gene. 1994;141:267–270. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90583-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herrick D, Parker R, Jacobson A. Identification and comparison of stable and unstable mRNAs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:2269–2284. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.5.2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hisatake K, Hasegawa S, Takada R, Nakatani Y, Horikoshi M, Roeder R G. The p250 subunit of native TATA box-binding factor TFIID is the cell-cycle regulatory protein CCG1. Nature. 1993;362:179–181. doi: 10.1038/362179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holstege F C, Jennings E G, Wyrick J J, Lee T I, Hengartner C J, Green M R, Golub T R, Lander E S, Young R A. Dissecting the regulatory circuitry of a eukaryotic genome. Cell. 1998;95:717–728. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang K N, Odinsky S A, Cross F R. Structure-function analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae G1 cyclin Cln2. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4654–4666. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ikeda K, Steger D J, Eberharter A, Workman J L. Activation domain-specific and general transcription stimulation by native histone acetyltransferase complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:855–863. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iyer V, Struhl K. Absolute mRNA levels and transcriptional initiation rates in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5208–5212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaufmann J, Ahrens K, Koop R, Smale S T, Muller R. CIF150, a human cofactor for transcription factor IID-dependent initiator function. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:233–239. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim Y-J, Bjorklund S, Li Y, Sayre M H, Kornberg R D. A multiprotein mediator of transcriptional activation and its interaction with the C-terminal repeat domain of RNA polymerase II. Cell. 1994;77:599–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klein C, Struhl K. Increased recruitment of TATA-binding protein to the promoter by transcriptional activation domains in vivo. Science. 1994;266:280–282. doi: 10.1126/science.7939664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kokubo T, Swanson M J, Nishikawa J I, Hinnebusch A G, Nakatani Y. The yeast TAF145 inhibitory domain and TFIIA competitively bind to TATA-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1003–1012. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kokubo T, Takada R, Yamashita S, Gong D-W, Roeder R G, Horikoshi M, Nakatani Y. Identification of TFIID components required for transcriptional activation by upstream stimulatory factor. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:17554–17558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koleske A J, Young R A. The RNA polymerase II holoenzyme and its implications for gene regulation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:113–116. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88977-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koleske A J, Young R A. An RNA polymerase II holoenzyme responsive to activators. Nature. 1994;368:466–469. doi: 10.1038/368466a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Komarnitsky P B, Klebanow E R, Weil P A, Denis C L. ADR1-mediated transcriptional activation requires the presence of an intact TFIID complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5861–5867. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Komarnitsky P B, Michel B, Buratowski S. TFIID-specific yeast TAF40 is essential for the majority of RNA polymerase II-mediated transcription in vivo. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2484–2489. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kotani T, Miyake T, Tsukihashi Y, Hinnebusch A G, Nakatani Y, Kawaichi M, Kokubo T. Identification of highly conserved amino-terminal segments of dTAFII230 and yTAFII145 that are functionally interchangeable for inhibiting TBP-DNA interactions in vitro and in promoting yeast cell growth in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32254–32264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuldell N H, Buratowski S. Genetic analysis of the large subunit of yeast transcription factor IIE reveals two regions with distinct functions. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5288–5298. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kunkel T A, Roberts J D, Zakour R A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuras L, Struhl K. Binding of TBP to promoters in vivo is stimulated by activators and requires Pol II holoenzyme. Nature. 1999;399:609–613. doi: 10.1038/21239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee T I, Young R A. Regulation of gene expression by TBP-associated proteins. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1398–1408. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li R, Yu D S, Tanaka M, Zheng L, Berger S L, Stillman B. Activation of chromosomal DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by acidic transcriptional activation domains. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1296–1302. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li X Y, Virbasius A, Zhu X, Green M R. Enhancement of TBP binding by activators and general transcription factors. Nature. 1999;399:605–609. doi: 10.1038/21232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lieberman P M, Berk A J. A mechanism for TAFs in transcriptional activation: activation domain enhancement of TFIID-TFIIA-promoter DNA complex formation. Genes Dev. 1994;8:995–1006. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu H T, Gibson C W, Hirschhorn R R, Rittling S, Baserga R, Mercer W E. Expression of thymidine kinase and dihydrofolate reductase genes in mammalian ts mutants of the cell cycle. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3269–3274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martinez E, Ge H, Tao Y, Yuan C X, Palhan V, Roeder R G. Novel cofactors and TFIIA mediate functional core promoter selectivity by the human TAFII150-containing TFIID complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6571–6583. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martinez E, Kundu T K, Fu J, Roeder R G. A human SPT3-TAFII31-GCN5-L acetylase complex distinct from transcription factor IID. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23781–23785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martinez E, Zhou Q, L'Etoile N D, Oelgeschlager T, Berk A J, Roeder R G. Core promoter-specific function of a mutant transcription factor TFIID defective in TATA-box binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11864–11868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McLean M, Hubberstey A V, Bouman D J, Pece N, Mastrangelo P, Wildeman A G. Organization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae actin gene UAS: functional significance of reiterated REB1 binding sites and AT-rich elements. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:605–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18040605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Melcher K, Johnston S A. GAL4 interacts with TATA-binding protein and coactivators. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2839–2848. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Michel B, Komarnitsky P, Buratowski S. Histone-like TAFs are essential for transcription in vivo. Mol Cell. 1998;2:663–673. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mizzen C A, Yang X J, Kokubo T, Brownell J E, Bannister A J, Owen-Hughes T, Workman J, Wang L, Berger S L, Kouzarides T, Nakatani Y, Allis C D. The TAFII250 subunit of TFIID has histone acetyltransferase activity. Cell. 1996;87:1261–1270. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81821-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moqtaderi Z, Bai Y, Poon D, Weil P A, Struhl K. TBP-associated factors are not generally required for transcriptional activation in yeast. Nature. 1996;383:188–191. doi: 10.1038/383188a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moqtaderi Z, Keaveney M, Struhl K. The histone H3-like TAF is broadly required for transcription in yeast. Mol Cell. 1998;2:675–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Myer V E, Young R A. RNA polymerase II holoenzymes and subcomplexes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27757–27760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.27757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Myers L C, Gustafsson C M, Bushnell D A, Lui M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Kornberg R D. The Med proteins of yeast and their function through the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain. Genes Dev. 1998;12:45–54. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Natarajan K, Jackson B M, Rhee E, Hinnebusch A G. yTAFII61 has a general role in RNA polymerase II transcription and is required by Gcn4p to recruit the SAGA coactivator complex. Mol Cell. 1998;2:683–692. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oelgeschlager T, Chiang C M, Roeder R G. Topology and reorganization of a human TFIID-promoter complex. Nature. 1996;382:735–738. doi: 10.1038/382735a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oelgeschlager T, Tao Y, Kang Y K, Roeder R G. Transcription activation via enhanced preinitiation complex assembly in a human cell-free system lacking TAFIIs. Mol Cell. 1998;1:925–931. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ogden J E, Stanway C, Kim S, Mellor J, Kingsman A J, Kingsman S M. Efficient expression of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae PGK gene depends on an upstream activation sequence but does not require TATA sequences. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:4335–4343. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.12.4335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ogryzko V V, Kotani T, Zhang X, Schlitz R L, Howard T, Yang X J, Howard B H, Qin J, Nakatani Y. Histone-like TAFs within the PCAF histone acetylase complex. Cell. 1998;94:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Orphanides G, Lagrange T, Reinberg D. The general transcription factors of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2657–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ptashne M, Gann A. Transcriptional activation by recruitment. Nature. 1997;386:569–577. doi: 10.1038/386569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Purnell B A, Emanuel P A, Gilmour D S. TFIID sequence recognition of the initiator and sequences farther downstream in Drosophila class II genes. Genes Dev. 1994;8:830–842. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ranallo R T, Struhl K, Stargell L A. A TATA-binding protein mutant defective for TFIID complex formation in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3951–3957. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ranish J A, Yudkovsky N, Hahn S. Intermediates in formation and activity of the RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex: holoenzyme recruitment and a postrecruitment role for the TATA box and TFIIB. Genes Dev. 1999;13:49–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Regier J L, Shen F, Triezenberg S J. Pattern of aromatic and hydrophobic amino acids critical for one of two subdomains of the VP16 transcriptional activator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:883–887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Roeder R G. The role of general initiation factors in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:327–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ruppert S, Wang E H, Tjian R. Cloning and expression of human TAFII250: a TBP-associated factor implicated in cell-cycle regulation. Nature. 1993;362:175–179. doi: 10.1038/362175a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sanders S L, Klebanow E R, Weil P A. TAF25p, a non-histone-like subunit of TFIID and SAGA complexes, is essential for total mRNA gene transcription in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18847–18850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sauer F, Tjian R. Mechanisms of transcriptional activation: differences and similarities between yeast, Drosophila, and man. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:176–181. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sekiguchi T, Noguchi E, Hayashida T, Nakashima T, Toyoshima H, Nishimoto T, Hunter T. D-type cyclin expression is decreased and p21 and p27 CDK inhibitor expression is increased when tsBN462 CCG1/TAFII250 mutant cells arrest in G1 at the restrictive temperature. Genes Cells. 1996;1:687–705. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sekiguchi T, Nohiro Y, Nakamura Y, Hisamoto N, Nishimoto T. The human CCG1 gene, essential for progression of the G1 phase, encodes a 210-kilodalton nuclear DNA-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3317–3325. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.6.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shen W-C, Green M R. Yeast TAFII145 functions as a core promoter selectivity factor, not a general coactivator. Cell. 1997;90:615–624. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80523-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shore D. RAP1: a protean regulator in yeast. Trends Genet. 1994;10:408–412. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sikorski R S, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Struhl K. Naturally occurring poly(dA-dT) sequences are upstream promoter elements for constitutive transcription in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:8419–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Struhl K, Moqtaderi Z. The TAFs in the HAT. Cell. 1998;94:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stuart D, Wittenberg C. Cell cycle-dependent transcription of CLN2 is conferred by multiple distinct cis-acting regulatory elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4788–4801. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Suzuki-Yagawa Y, Guermah M, Roeder R G. The ts13 mutation in the TAF(II)250 subunit (CCG1) of TFIID directly affects transcription of D-type cyclin genes in cells arrested in G1 at the nonpermissive temperature. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3284–3294. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tansey W P, Herr W. TAFs: guilt by association? Cell. 1997;88:729–732. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81916-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Thompson C M, Young R A. General requirement for RNA polymerase II holoenzymes in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4587–4590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]