Abstract

The decision to use adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) after surgical resection for stage II colon cancer remains an area of clinical uncertainty. Many patients diagnosed with stage II colon cancer receive ACT, despite inconclusive evidence of long-term clinical benefit. This study investigates patient experiences and perceptions of treatment decision-making and shared decision making (SDM) for ACT among patients diagnosed with stage II colon cancer. Stage II colon cancer patients engaged in treatment or follow-up care aged >18 years were recruited from two large NYC health systems. Patients participated in 30–60-min semi-structured interviews. All interviews were transcribed, translated, coded, and analyzed using a thematic analysis approach. We interviewed 31 patients, of which 42% received ACT. Overall, patient perspectives indicate provider inconsistency in communicating ACT harms, benefits, and uncertainties, and poor elicitation of patient preferences and values. Patients reported varying perceptions and understanding of personal risk and clinical benefits of ACT. For many patients, receiving a clear treatment recommendation from the provider limited their participation in the decision-making process, whether it aligned with their decisional support preferences or not. Findings advance understanding of perceived roles and preferences of patients in SDM processes for cancer treatment under heightened clinical uncertainty, and indicate a notable gap in understanding for decisions made using SDM models in the context of clinical uncertainty. Educational and communication strategies and training are needed to support providers in communicating uncertainty, risk, treatment options, and implementing clinical guidelines to support patient awareness and informed decisions.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Colon cancer, Shared decision making, Patient decision making, Clinical practice guidelines, Guideline implementation

Patients with stage II colon cancer weigh provider recommendations, the balance of risks and benefits, and their personal preferences when making decisions about chemotherapy treatment.

Implications.

Practice: Practitioners and providers may benefit from eliciting patient understanding and preferences for involvement in the decision-making process for stage II colon cancer treatment.

Policy: Health systems have the opportunity to support the implementation of clinical guidelines to facilitate informed treatment decisions among cancer patients.

Research: Future research should develop interventions to support patient decision-making for cancer treatment, particularly where there is uncertain evidence about the harms and benefits.

INTRODUCTION

The decision to use adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) after surgical resection for stage II colon cancer is complex and remains an area of uncertainty. Uncertainty often arises from complexity, unpredictability, and lack of information, and commonly refers to the inability to predict patient response to a certain treatment due to incomplete scientific data [1–3]. In this context, uncertainty relates to the challenges of determining the benefits of ACT for stage II colon cancer patients, which continues to be debated due to limited and inconclusive evidence [4–9]. Published national guidelines by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) support the use of ACT for patients with high-risk features (e.g. presence of invasion, T4 primary tumors, or close to indeterminate margins) [4, 10], but recent studies among higher-risk patients found that ACT following surgical resection demonstrated little to no benefits for disease-free or overall survival, emphasizing the need to weigh these minimal benefits with the serious risk of morbidity or fatal complications [4, 10–13]. Despite the limited and mixed evidence [4–9], many patients diagnosed with stage II colon cancer, with or without high-risk features [13], routinely receive ACT.

Growing efforts to make healthcare more patient centered, including the emphasis on and use of shared decision making (SDM) in clinical practice, highlights the need for providers to educate and support patients in dealing with uncertainty when making medical decisions [14]. A previous publication from the National Cancer Institute identifies the management of uncertainty as a core function of patient-centered communication [15]. SDM and SDM processes are integral to the delivery of patient-centered care and patient engagement, and require that the patient and provider actively engage in the decision-making process together [16, 17]. Despite the benefits of SDM, including increased knowledge and satisfaction with care among patients [18, 19], SDM is not commonly achieved in the context of cancer care, and studies show that the level of involvement in SDM varies widely across cancer patients [20]. In situations where evidence is limited or inconclusive, SDM may be more difficult to achieve due to increased uncertainty, including in the context of the decision to routinely use ACT among stage II colon cancer patients.

Consistent with models of SDM [17, 21, 22], professional guidelines and experts recommend that providers estimate the risk of recurrence and cancer-related death with and without ACT, discuss both the risks and benefits associated with ACT, and elicit patient preferences to help patients make an informed decision [4, 10, 13]. It is also recommended that providers elicit patient preferences and discuss whether the potential benefits outweigh the potential risks [4].

It is well-established in research on cancer treatment decision-making that provider communication plays an influential role in patient decisions [17, 21–23]. However, results from in-depth interviews with oncologists and surgeons found they many lack the knowledge and training to discuss uncertain evidence, which may result in inconsistent or insufficient communication with stage II colon cancer patients about the risks and benefits of ACT [23]. Risk communication experts recommend that patients be fully informed about risks and benefits, and thus, that they should also be informed about uncertainties as well [24]. Despite this, research has also found that providers are hesitant to acknowledge uncertainty to patients [25], which may be influenced by both providers’ personal tolerance of risk and uncertainty, and concern that disclosing uncertainty to patients may result in anxiety, emotional distress, or loss of trust [1]. This is concerning because patient involvement in treatment decision making may be more limited when providers fail to fully communicate treatment benefits and risks, uncertainty of evidence, and elicit patient preferences [26–28]. This highlights the need to explore and better understand stage II colon cancer patient perspectives and their decision-making experiences.

Although a recent study found that colorectal cancer patients prefer to play an active role in the cancer treatment decision-making process [20], the extent to which patients are involved in the decision to use ACT in real-world practice is unclear. To date, no study has solicited patient perceptions of the role of providers in influencing ACT decisions in this context of uncertainty, what is communicated during clinical consultations, how they are involved in the decision-making process, and which factors influence their treatment decision. To address these gaps, this study investigates patient perspectives and experiences in treatment decisions for ACT under clinical uncertainty, using semi-structured qualitative interviews among patients diagnosed with stage II colon cancer.

METHODS

Recruitment

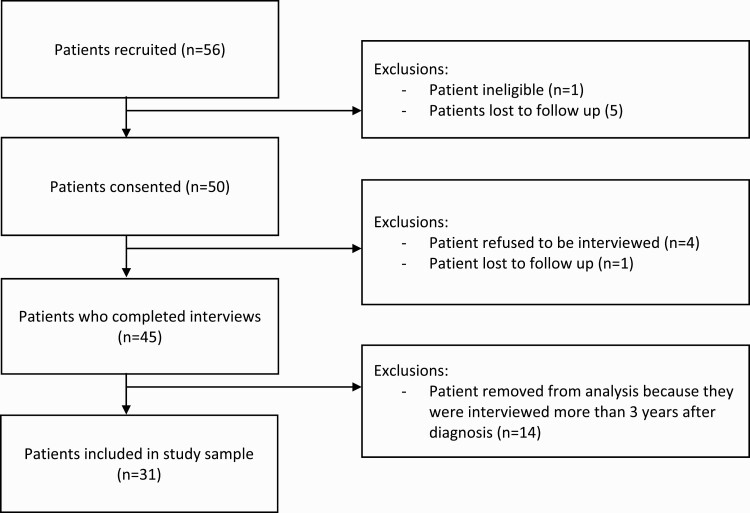

We recruited a purposeful sample of patients engaged in treatment or follow-up monitoring for stage II colon cancer from two healthcare systems (Columbia University and Mount Sinai Health System) in New York City between 2011 and 2016. To be eligible for participation, patients had to be diagnosed with stage II colon cancer within 3 years of study recruitment, over the age of 18, with the ability to speak English or Spanish. Eligibility criteria were confirmed by medical record by the study team. Eligible participants were approached during in-person appointments with oncologists or surgeons (e.g. appointments regarding treatment or for long-term follow-up) and told about the purpose of the study. Patients who expressed interest then met with a recruiter onsite to confirm eligibility and to obtain written consent. See Fig. 1. To better understand differences in factors influencing treatment decision-making, we recruited stage II colon cancer patients who received ACT and who did not receive ACT. The study was approved by Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health (Protocol #AAAI1206) and the Mount Sinai Health System (HS#: 12-00031) Institutional Review Board (IRB), and all procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the IRB.

Fig 1.

Patient recruitment and enrollment flow diagram.

Data collection and analysis

We completed 31 phone and in-person semi-structured qualitative interviews. Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 min and were conducted in English by a Research Assistant with a Master’s in Public Health and trained in qualitative research (D.M.C), or in Spanish by a native, bilingual speaker trained in qualitative research. Both interviewers were female and had no relationship or engagement with study participants prior to study commencement. The semi-structured interview guide was informed in part by the National Comprehensive Care Network guidelines for communicating treatment options to stage II colon cancer patients (Table 1) [10]. Specifically, we were interested in exploring if patient-provider communication guidelines [10] were met and in identifying factors influencing the patients’ decision to receive ACT, as well as patients experiences and preferences in making ACT treatment decisions. Participants received $20 after completing the interview in appreciation of their time. It was not necessary that any interviews be repeated or recorded a second time. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and translated from Spanish to English (when relevant). While it was not feasible to return transcripts to participants for comment or correction, we did share thematic results and findings from qualitative interviews for accuracy among members of our research team (including those who conducted interviews) as part of an internal “member check.”

Table 1.

Sample interview questions related to clinical guidelines

| Issue guiding discussion with stage II patients | NCCN patient/provider discussion recommendation [10] | Interview question |

|---|---|---|

| Was ACT discussed as an option? | Discussion about ACT between all stage II patients and provider | After your surgery, tell me about whether and how the option to have chemotherapy discussed with you? |

| What did the provider recommend and why? | Evidence supporting treatment | What information about chemotherapy was discussed with you and to what extent were uncertainties communicated? |

| High-risk characteristics | Probes: | |

| Assumption of ACT benefit from indirect evidence | • Did the doctor explain why he or she did recommend it? | |

| • To what extent did they talk you about the impact on survival and recurrence and risk and benefits? | ||

| • To what extent did they discuss uncertainties with you about chemotherapy? | ||

| What were the risks? | Morbidity associated with treatment | Tell me about some of the harms and risks of ACT that were discussed with you. |

| How well did you understand the risk information that was presented by the provider? Why or why not? | ||

| What did the patient want? | Patient preferences | How were your preferences, values, needs and emotions considered by the provider in making this decision? |

| How well did your provider make an effort to understand your social and life circumstances in helping you make this decision? Tell me more about this. | ||

| How was the decision made? | Shared decision-making | To what extent do you feel like that decision was made by the two of you together, you alone, the provider alone or some combination? |

| Probes: | ||

| • Were you involved in that decision to the extent you wanted to be? Why or why not? | ||

| • How well did you feel listened to and understood by the providers? |

Analyses were guided by the thematic content analysis approach [29, 30]. Dedoose software [31] was used to facilitate data management, coding, and collaborative analysis. We used an iterative process whereby a group of five to seven transcripts were independently reviewed line-by-line by coders (L.E.B., R.C.S.) trained in qualitative methods and applied an initial deductive code structure to generate a list of domains and codes based broadly on interview topics (e.g., national recommendations for patient-provider discussions, provider recommendation, decision-making involvement [4, 10]; see Table 1). Team-based codebook development guidelines were followed [32]. Next, the team used an inductive data-driven approach to identify new codes, allowing the codebook to evolve as a result of team meetings and discussion where new findings and categories were discussed. Following this process, the final code structure was applied to all transcripts independently by the coders (L.E.B., R.C.S.) to facilitate the reliability of the coding process. The study team reviewed all inconsistencies and discrepancies were resolved by the principal investigator. Data collection and analysis continued until saturation of new ideas and themes was reached. Four overarching qualitative themes were identified through coding and analysis and are presented in this paper. Participants were not asked to provide feedback on the data analysis or study findings.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

We interviewed 31 patients (see Table 2) within 3 years of diagnosis. Most patients were male (55%) and white (71%), with a mean of 63 years. A total of 35% of patients identified as Hispanic. Most patients had a college level or higher education (61%), but ranged from less than eighth grade education to postgraduate education. While we did seek to understand the range of patient experiences, including both patients who did and did not receive ACT, this study did not aim to equally sample patients based on whether or not they received ACT. Across the sample, 42% of patients interviewed received ACT, and 58% did not.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of patient sample (N = 31)

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | ACT | No ACT | ||

| Gender | Males | 17 (55) | 7 (54) | 10 (56) |

| Females | 14 (44) | 6 (46) | 8 (44) | |

| Race | White or Caucasian | 21 (71) | 9 (69) | 13 (72) |

| Black or African American | 2 (6) | 1 (8) | 1 (6) | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1 (3) | 1 (8) | − | |

| Native American or American Indian | 1 (3) | − | 1 (6) | |

| Other | 4 (13) | 2 (15) | 2 (11) | |

| Unknown | 1 (3) | − | 1 (6) | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 11 (35) | 3 (23) | 8 (44) |

| Not Hispanic | 20 (65) | 10 (77) | 10 (56) | |

| Age (years) | 20–39 | 1 (3) | 1 (8) | − |

| Range: 26–89 | 40–59 | 12 (39) | 6 (46) | 6 (33) |

| Mean: 63 | 60–79 | 12 (39) | 5 (38) | 7 (39) |

| 80–99 | 6 (19) | 1 (8) | 5 (28) | |

| Education | Less than High School | 2 (6) | − | 2 (11) |

| High School or equivalent | 10 (32) | 3 (23) | 7 (39) | |

| College and above | 19 (61) | 10 (77) | 9 (50) | |

| Marital status | Single | 5 (16) | 5 (38) | − |

| Married | 17 (55) | 5 (38) | 12 (67) | |

| Divorced | 5 (16) | 1 (8) | 4 (22) | |

| Widowed | 3 (10) | 1 (8) | 2 (11) | |

| Unknown | 1 (3) | 1 (8) | − | |

| Recruitment site | Columbia | 20 (65) | 6 (46) | 14 (78) |

| Mount Sinai | 11 (35) | 7 (54) | 4 (22) |

Qualitative themes

We identified four overarching themes. Initially, we aimed to explore if there were thematic differences by receipt of ACT. However, due to limited differences in themes across patients who did or did not receive ACT, results are presented in aggregate by theme alongside representative quotes and text. The data presented are consistent with the overall study findings, and additional quotes reflective of each theme are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Additional illustrative quotes by theme

| 1. Discussion of both harms and benefits |

| “I feel maybe that there should have been a little bit more time, you know, and a little bit more detail specifically about, what the benefits would be to [taking ACT]… it’s need-to- know information. So, in the decision-making process, there was a specific amount of information that I had to go in there and actually look up for myself.” (Female, age 26, ACT) |

| “[The doctor] explained some of the side effects that I would have if I needed treatment…nausea, he said I would feel tired. It is not pretty, it is not fun. Those are the words that I remember pretty good.” (Male, age 43, no ACT) |

| “They informed me about the benefits of chemotherapy, to eliminate malignant cells that had remained in the body, to prevent recurrence if they were not there. And the damage, apart from side effects I was told I would feel, and I’ve felt them, [but was] not [told] anything else. Just [the side effects of ACT].” (Male, age 77, ACT) |

| 2. Patient perceptions of personal risk and clinical benefit |

| “[The doctor] was clear that, there is no guarantee but I would probably gain a couple of percentage points… you know, having the chemotherapy.” (Female, age 61, ACT) |

| “He showed me what my, what the statistics were and I had to make up my mind, whether I wanted to go through [ACT] or not…My percentage of living was better with the treatment.” (Female, age 83, ACT) |

| “The difference between the two percentages, if I had the treatment or not have the treatment with regard to [reoccurrence] was so low that they decided treatment would be more damaging to my body.” (Female, age 53, no ACT) |

| “I was wanting statistics, if I [took ACT], what would it do to my survival statistics and my statistics of the cancer returning.” (Female, age 61, ACT) |

| “If it was something like 20% better chance with chemo we would have gone for it. But the fact it was only 5% why go through chemo?” (Male, age 76, no ACT) |

| 3. Patient involvement and preferences for decisional support |

| “I think medical decisions are hard because doctors give their opinions but you have to put your brain power into them. [The provider was] really recommending [ACT]. She let me know how she felt, [but] I had the option to opt out and it was very confusing.” (Female, age 61, ACT) |

| “I didn’t really have too much of information as far as like forms of treatments or alternative treatments and things like that…[but the doctor] explained everything and I thought [no ACT] was okay for me.” (Male, age 43, no ACT) |

| “I didn’t know of multiple [treatment] options I just knew that the chemotherapy was going to be given to me and I didn’t hear of any other options…..I was more or less told that you know, this is what has to be done.” (Female, age 68, ACT) |

| 4. Influence of provider recommendation amidst uncertainty |

| “I felt that he was an expert and a professional and he knew what he was talking about. I was in an extremely vulnerable position and I put my trust in him….It’s cancer and you don’t want to take any chances” (Female, age 67, ACT). |

| “The fact that he was so certain, that I needed chemotherapy, was what kept me from opting out.” (Female, age 61, ACT). |

| “I think I had ultimately a high degree of trust in the oncologist and he has been around a long time, he knew what he was doing.” (Male, age 52, ACT) |

| “Walking into those offices I thought it was critical that someone well versed in the field examine me…and give me their opinion [on treatment].” (Female, age 52, no ACT) |

| “[ACT] wasn’t recommended….I mean, why would I get it, if he’s not recommending it?” (Female, age 50, no ACT) |

Discussion of both harms and benefits associated with ACT

Most participants reported that their primary provider involved in making the ACT decision (predominantly oncologists) did not discuss the benefits, harms, or uncertainty around ACT use before deciding on the course of treatment: “No uncertainties were communicated to me at all” (Male, age 41, ACT). Only a few participants receiving ACT reported that their provider gave them detailed information, outlined their clinical recommendations, and gave them the option to take or not take ACT.

Several participants described how their provider mainly discussed the benefits of ACT (“Well, benefits [were discussed], nothing about harm. They just said that it’s my best option was to have chemo” (Female, age 83, no ACT). In contrast, a few other participants felt that the provider only discussed the harms of ACT to protect themselves, not necessarily to help the patient in making a decision about receiving the treatment: “[Doctors] will give you a whole big list of side effects that can occur, to protect themselves” (Male, age 81, no ACT). When asked what information was critical to making a decision, one participant emphasized: “Well the risk factors and knowing that if it wasn’t treated, I was probably going to die” (Female, age 67, ACT). Of note, a few participants reported no interest in having a discussion with the provider or hearing about evidence, or the harms and benefits. One participant stated:

I didn’t want to hear all that, I just wanted to get it done, so I kind of discouraged all that conversation… let’s get started, let’s get it done, let’s get over with. Let me move on with my life. I didn’t want to go through over that” (Female, age 59, ACT).

Patient perceptions and understanding of personal risk and clinical benefit in making treatment decision

Participants were asked what type of risk and clinical benefit information about ACT was discussed with them as they made treatment decisions. Many participants reported that their provider discussed personal risk and clinical benefit of ACT, but the specificity of the content varied (see Table 3). Most participants found it helpful to see information about their personal risk, such as survival or recurrence rates in similar patient populations.

I think one of the significant things that helped me was my understanding that when you look at recurrence rates and survival rates, for example let’s say five-year survival rates for stage II cancer which was I think 60 to 70% [for me]. In my own age bracket [survival rates] are considerably high. For people with stage IIA, it is higher. I think that this kind of information was very helpful for someone in my position to know.” (Male, age 52, ACT).

Additionally, participant perception, interpretation, and valuing of risk information and treatment benefit differed. For example, two participants reported discussing a marginal 5% improvement in risk of recurrence with ACT, and processed information about their risk differently:

It was just a small significant factor…If it was something like 20% better chance with chemo we would have gone for it. But the fact it was only 5% [improvement in disease-free survival] why go through chemo? (Male, age 76, no ACT).

It was like you know, if you take on the chemo, we feel like it is going to be [a 5% improvement]. And, you know what, I want to be that 5% on the table, that was significant [to me], so that’s what helped me make my decision” (Male, age 44, ACT).

Patient involvement and preferences for decisional support

We asked participants about their treatment decision-making process for ACT, and about their level of involvement in the process. Participants identified factors including information and support from providers as either facilitators or barriers to SDM for treatment. For instance, participants who reported that their provider was not involved in the decision, outside of providing written materials to review outside of their clinical consultation, more commonly reported frustration about having to make a decision about using ACT. One participant shared: “I didn’t want to have to make the decision … I wanted somebody to say to me, “this is the perfect, right answer to this.” [But] there wasn’t [a perfect answer]” (Female, age 61, ACT). In contrast, several other participants acknowledged that although it was difficult to make a decision, they appreciated the information and support they received from their providers during the consultation. According to a participant: “I think the thing that impressed me the most was that they were willing to trust my judgment and I got that feeling right at the beginning that they didn’t want the coerce me and they understood that it was a difficult decision” (Male, age 52, ACT).

A few participants did not feel it was important or appropriate for them to be involved in the decision-making process. For example, one woman shared: “There wasn’t any extent for me to be [involved]. I have no expertise in [cancer treatment] and I had no idea…the oncologists had to decide” (Female, age 52, no ACT). A few participants reported limited involvement in the decision-making process due to confusion about treatment options and what decisions needed to be evaluated or made. One man reported: “It was a little – you might call it frustrating. I thought we had already agreed that I wasn’t going to do the chemo... And as we were talking about it, they mentioned that I had the choice, and I had many decisions” (Male, age 81, no ACT).

Influence of provider recommendation in shaping ACT decisions amidst uncertainty

Most participants stated that the provider’s recommendation was the most important factor in the decision to receive or not receive ACT (See Table 3 for additional quotes). One man explained: “I mean, I felt very comfortable going with [the provider’s] opinion and it definitely played a big factor [in my decision]” (Male, age 44, ACT). Most participants described how they trusted their providers’ expertise and reputation, and few questioned their treatment recommendation: “He is a good oncologist, everything I heard about him. I felt whatever he was saying was good” (Female, age 53, no ACT). However, several participants reported that receiving a provider recommendation also meant there was no decision to be made by them: “If he had decided not to give [ACT] to me, I would just go along with [the provider’s recommendation], so I didn’t have to make a decision” (Female, age 53, no ACT).

Of note, only two participants made the decision to not receive ACT despite their providers’ recommendations because they did not feel the provider had their best interests in mind or they felt their provider did not adequately consider their preferences and values.

He’s very famous… lots of people praise him for his treatments, people with cancer and [he gave] them chemotherapy. Maybe he just didn’t understand our reluctance to have chemotherapy.” (Male, age 76, no ACT).

They presented to me that it would be my best interest to [take ACT]. However, the research that I have done and looking over what I was presented with in the report [from the provider], I decided [ACT] was not my best interest.” (Male, age 67, no ACT).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has solicited patient perceptions of the role of providers in influencing ACT decisions in the context of uncertainty regarding the benefits of receiving ACT among stage II colon cancer patients. These patient perspectives indicate that recommended clinical guidelines for stage II colon cancer patients (e.g., to have an in-depth discussion of harms, benefits, treatment options, and assumed clinical benefit) are not being consistently followed in practice. Participants reported variable perceptions and valuing of the same risk information; a 5% probability of improvement in risk of reoccurrence was reported as a reason to receive ACT for some patients, and a reason not to receive ACT for others. We also found that SDM for ACT was limited due to differing participant preferences for involvement and because participants were not always given enough information about the uncertainty inherent in this treatment decision. Additionally, consistent with prior literature, provider recommendations plays a central role in both the decision-making process, and whether or not patients ultimately receive ACT, and their opinion may be particularly important in circumstances like these where there is uncertainty about the best option from a clinical perspective.

While clinical guidelines from NCCN and ASCO recommended patients and providers discuss all treatment options, the benefits and risks of taking ACT, and elicit patient preference before deciding on a course of treatment [4, 10], many participants reported that was not what happened in practice during their clinical consultations. This is consistent with previous qualitative research examining provider perspectives on ACT for stage II colon cancer patients [23]. Participant experiences from our sample indicate that providers vary in the amount, presentation, and specificity of information conveyed and clearly communicated regarding the uncertainty, harms and benefits of ACT. This was despite the fact that almost all participants in our sample reported that they wanted, and even needed, thorough and balanced information to decide on treatment. Inadequate or unclear provider communication and presentation of information resulted in confusion and feelings of frustration and worry for participants when it came time to make a decision. The amount and type of information that providers convey to their patients has a direct impact upon whether or not patients are able to make a fully informed decision [33]; consistent with recent research on informational support needs and preferences for colon cancer patients in clinical practice [34]. Additionally, it may be valuable to record and analyze clinical consultations and patient-provider communication during this decision-making process, to better understand communication patterns and the content of what is communicated. Previous research investigating disclosure of uncertainty during recorded breast cancer consultations found that uncertainty associated with prognostic estimates was conveyed in only half of patient consultations, but that patients were comfortable discussing uncertainty arising from the unpredictability of future events [35]. These findings suggest that further educational and intervention efforts such as development of treatment decision support tools for stage II colon cancer are needed to support provider implementation of clinical guidelines and discussion of uncertainty in practice.

Our findings indicate that providers may not be communicating or contextualizing risk probabilities (i.e., survival and reoccurrence rates based on patient profile) consistently or effectively to this patient population. Personal meaning and perceptions of risk and benefit concepts as they relate to medical decisions vary among patients and deserve more attention when clinical benefits are small and treatment decisions more value-laden. Risk communication literature suggests that even when presented with information and statistics about risk it is challenging for patients to understand and interpret the meaning if the risk information is not tailored to message patients’ specific informational needs [36]. Specifically, best practices for communicating risk in this clinical context suggest using absolute risk rather than relative risk formats, frequencies rather than percentages, and using visuals representations and pictographs to communicate risk and benefit information to improve patient understanding and decision-making [36, 37]. Additionally, research suggests that use of effective risk communication may be particularly important in contexts that require evaluating treatment options with marginal benefits or improvements [36, 37], as is the case of ACT use among stage II colon cancer patients. This study was not able to include or examine recorded conversations of clinical consultations, and while these participant perspectives offer some insight into the risk information discussed and how that information was used in the decision-making process, deeper investigation is needed. Future work should go beyond asking patients if risks were discussed with them and investigate the specific risk information needs (e.g., risk of reoccurrence with ACT, chance of survival without ACT) and risk communication preferences to support informed decisions about treatment, particularly due to the uncertainty of the balance between ACT benefits to stage II colon cancer patients and harms.

Our findings also highlight a potential gap in patient involvement in treatment decisions and the SDM process. As our findings support, providers often fall short of engaging patients and there is room for improvement in adequately eliciting patient preferences for information or discussing uncertainty around treatment options, including for ACT [38, 39]. Studies show that involving cancer patients in the decision-making process to the extent to which they want to be involved is associated with positive outcomes, as long as they perceive that their values and preferences are addressed [17–19]. Given the marginal clinical benefits of ACT in this patient population [4, 10–13], patient preferences and values may play an even more influential and prominent role when making decisions about treatment. Patient involvement and SDM is critical in cancer treatment decisions, and may be particularly so in cancer decisions involving conflicting evidence or with high degrees of uncertainty [23]. These findings further support the need for to elicit assessments of patient’s preferences, values, and informational needs (e.g., personal risk information, discussing all treatment options), and for treatment decision support tools and interventions aimed at developing provider’s skills for eliciting patient risk information and decisional support preferences to improve the SDM process [40–42].

These findings add depth to understanding the influential impact of a provider’s recommendation in the context of treatment decisions with high uncertainty, including the importance of trust, regardless of patient preferences for SDM or decisional support. Based on the perceptions of this patient sample, providers may not be presenting a balanced view of the benefits, risks, and uncertainty of ACT, when giving their treatment recommendation. In addition, many participants reported that their provider only discussed a single treatment option. As a result, participants perceived that there was no decision to be made by them when a provider provided a recommendation. It is possible that providers did not present ACT as a treatment option for some patients based on individual characteristics as outlined by national guidelines [4, 10]. Patients may also be reluctant to challenge a provider’s recommendation, even if they prefer a different option [33, 43]. Regardless, participants reported that they trusted their provider’s recommendation, and nearly all participant treatment decisions aligned with the recommendation they received from their provider. Future studies should continue to explore the role of provider recommendations in the context of heightened uncertainty given that provider influence and recommendation can be powerful in the absence of strong clinical evidence [23]. Future research should explore the role of provider recommendations, and the value and usefulness of traditional SDM models between patient and provider [44–46] in contexts of uncertainty where patients may expect, rely on, and even prefer, to receive a direct recommendation from their provider than truly share the decision.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The sample of participants limits our ability to generalize to all stage II colon cancer patients served in different clinical settings. In addition, we did not confirm through chart review or through provider interviews if the treatments received or recommended aligned with clinical guidelines. However, there were no substantial changes in clinical treatment guidelines or care delivery processes during the years the study was conducted. While we recognize there may be some bias in recalling prior discussions with providers, the research conducted here is qualitative in nature and meant to capture their ongoing perceptions and experiences with respect to treatment decisions. Perhaps given the critical importance of this decision with respect to their cancer survival and quality of life, we also found high levels of details and recall among patients with respect to this decision and the clinical consultation. Future studies should record clinical consultations and discussions about treatment decisions, and capture patient perspectives prospectively following the visit. Despite these limitations, our findings provide an in-depth understanding of a previously understudied topic and a highly understudied patient population in the cancer literature, including some diversity by ethnicity and age (e.g., 35 % were Hispanic and 19% were 80 years of age or older).

CONCLUSION

This study is one of the first to investigate in-depth patient perspectives on treatment decisions specifically among this population of stage II colon cancer patients, and sheds light on treatment decisions under high clinical uncertainty, which is increasingly common for a number of cancer-related contexts. These findings also contribute to research on the perceived role and preferences of patients in decision making processes for cancer treatment, and indicate a notable gap in SDM for decisions made in the context of clinical uncertainty. There are many opportunities to improve clinical risk communication and discussion of uncertainty to better support and inform treatment decisions for stage II colon cancer patients.

These findings have several important clinical and practice implications. First, it may be important for practitioners and providers to revisit assumptions about the perceived roles and involvement preferences for patients in the decision-making process, as dynamics and roles may differ in the context of high clinical uncertainty where cancer treatment decisions are increasingly being influenced by providers. Second, efforts are needed to improve provider communication of risk and clinical options for cancer treatment decisions. Providers and practitioners should consider and test multiple strategies for communicating individual risk and treatment options and eliciting patient involvement preferences during clinical consultation. Third, educational and training strategies are needed to educate and support providers in communicating uncertainty, risk, and implementing guideline-based recommendations for this patient population. Provider knowledge and communication is critical for ensuring patients derive meaningful information from clinical consultations, and make informed decision about their care, to the extent they prefer to be involved. Finally, additional research examining the longer-term impact of patient-provider communication on treatment decisions and patient psychosocial and health outcomes is needed. This is especially important for stage II colon cancer patients who lack strong clinical evidence to guide treatment decisions and rely heavily on providers for information, personal recommendations, and decisional support.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank recruiters at Mount Sinai and the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Funding: This work was supported by the American Cancer Society [grant number 124793-MRSG-13–152-01-CPPB] (PI: Shelton); the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health [grant numbers UL1 TR000040, UL1 RR024156]; and IMSD: National Institute of General Medical Sciences [grant number R25-GM062454].

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human Rights: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health Institutional Review Board (Protocol #AAAI1206) and the Mount Sinai Health System Institutional Review Board (HS#: 12-00031).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Welfare of Animals: This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Study Registration: This study was not formally registered.

Analytic Plan Pre-Registration: The analysis plan was not formally pre-registered.

Data Availability: De-identified data from this study are not available in a public archive. De-identified data from this study will be made available (as allowable according to institutional IRB standards) by emailing the corresponding author. There is not analytic code associated with this study. Materials used to conduct the study are not publicly available.

References

- 1. Dhawale T, Steuten LM, Deeg HJ. Uncertainty of physicians and patients in medical decision making. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(6):865–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seely AJ. Embracing the certainty of uncertainty: Implications for health care and research. Perspect Biol Med. 2013;56(1):65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beresford EB. Uncertainty and the shaping of medical decisions. Hastings Cent Rep. 1991;21(4):6–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Benson AB 3rd, Schrag D, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(16):3408–3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carrato A. Adjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2008;2(4 Suppl):S42–S46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Gramont A, Tournigand C, André T, Larsen AK, Louvet C. Adjuvant therapy for stage II and III colorectal cancer. Semin Oncol. 2007;34(2 Suppl 1):S37–S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wolmark N, Rockett E, Mamounas E, et al.. Clinical trial to assess the relative efficacy of fluorouracil and leucovorin, fluorouracil and levamisole, and fluorouracil, leucovorin, and levamisole in patients with Dukes’ B and C carcinoma of the colon: Results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project C-04. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(11):3553–3559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mamounas E, Wieand S, Wolmark N, et al.. Comparative efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with Dukes’ B versus Dukes’ C colon cancer: results from four National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project adjuvant studies (C-01, C-02, C-03, and C-04). J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(5):1349–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marshall JL. Risk assessment in Stage II colorectal cancer. Oncology. 2010;24(1 Suppl 1):9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Benson AB 3rd, Venook AP, Cederquist L, et al. Colon cancer, version 1.2017, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(3):370–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Figueredo A, Coombes ME, Mukherjee S. Adjuvant therapy for completely resected Stage II Colon Cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O’Connor ES, Greenblatt DY, LoConte NK, et al.. Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer with poor prognostic features. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3381–3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Varghese A. Chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2015;28(4):256–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baker A. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Vol. 323. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Epstein RM, Street RL. Jr. Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16. O’Connor AM, Stacey D, Entwistle V, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beers E, Lee Nilsen M, Johnson JT. The role of patients: Shared decision-making. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2017;50(4):689–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Oshima Lee E, Emanuel EJ. Shared decision making to improve care and reduce costs. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4(4):1–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Damm K, Vogel A, Prenzler A. Preferences of colorectal cancer patients for treatment and decision-making: A systematic literature review. Eur J Cancer Care. 2014;23(6):762–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Arora NK, et al.. Association of actual and preferred decision roles with patient-reported quality of care: Shared decision making in cancer care. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(1):50–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Singh JA, Sloan JA, Atherton PJ, et al.. Preferred roles in treatment decision making among patients with cancer: A pooled analysis of studies using the Control Preferences Scale. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(9):688–696. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shelton RC, Brotzman LE, Crookes DM, Robles P, Neugut AI. Decision-making under clinical uncertainty: An in-depth examination of provider perspectives on adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(2):284–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kennedy BR, Mathis CC, Woods AK. African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: Healthcare for diverse populations. J Cult Divers. 2007;14(2):56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Etkind SN, Bristowe K, Bailey K, Selman LE, Murtagh FE. How does uncertainty shape patient experience in advanced illness? A secondary analysis of qualitative data. Palliat Med. 2017;31(2):171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tamirisa NP, Goodwin JS, Kandalam A, et al. Patient and physician views of shared decision making in cancer. Health Expect. 2017;20(6):1248–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Couper MP, Fagerlin A. Disparities in patient reports of communications to inform decision making in the DECISIONS survey. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(2):198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mahmoodi N, Sargeant S. Shared decision-making - Rhetoric and reality: Women’s experiences and perceptions of adjuvant treatment decision-making for breast cancer. J Health Psychol. 2019;24(8):1082–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J.. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Method Sourcebook. CA, USA: SAGE Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dedoose, Dedoose. Web Application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data. LLC Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32. MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, et al.. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. CAM J. 1998;10(2):31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Frongillo M, Feibelmann S, Belkora J, Lee C, Sepucha K. Is there shared decision making when the provider makes a recommendation? Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90(1):69–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Islind AS, Johansson V, Vallo Hult H, et al.. Individualized blended care for patients with colorectal cancer: The patient’s view on informational support. Support Care Cancer. 2020:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Engelhardt EG, Pieterse AH, Han PJ, et al.. Disclosing the uncertainty associated with prognostic estimates in breast cancer: Current practices and patients’ perceptions of uncertainty. Med Decis Making. 2017;37(3):179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zikmund-Fisher BJ. The right tool is what they need, not what we have: A taxonomy of appropriate levels of precision in patient risk communication. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(1 Suppl):37S–49S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA. Helping patients decide: Ten steps to better risk communication. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(19):1436–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Singh S, Butow P, Charles M, Tattersall MH. Shared decision making in oncology: Assessing oncologist behaviour in consultations in which adjuvant therapy is considered after primary surgical treatment. Health Expect. 2010;13(3):244–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kane HL, Halpern MT, Squiers LB, Treiman KA, McCormack LA. Implementing and evaluating shared decision making in oncology practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(6):377–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bieber C, Nicolai J, Gschwendtner K, et al. How does a shared decision-making (SDM) intervention for oncologists affect participation style and preference matching in patients with breast and colon cancer? J Cancer Educ. 2018;33(3):708–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fisher KA, Tan ASL, Matlock DD, Saver B, Mazor KM, Pieterse AH. Keeping the patient in the center: Common challenges in the practice of shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(12):2195–2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Légaré F, Adekpedjou R, Stacey D, et al.. Interventions for increasing the use of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):14–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Frosch DL, May SG, Rendle KAS, et al.. Authoritarian physicians and patients’ fear of being labeled “difficult”among key obstacles to shared decision making. Health Aff. 2012;31(5):1030–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]