Abstract

The aim of this research is to analyse the way young people perceive the food waste process, as well as the determinants and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the responsible behaviour of young people towards food waste. The research design involves a study on a sample of 375 students from Romanian universities and the development and validation of a model using SEM-PLS. Our findings show that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has led to more people exhibiting food waste reduction behaviour, an increased awareness for the ethics of food waste among young people, and increased awareness of the environmental consequences of food waste. The limits of the paper refer to non-probability sampling technique and sampling structure that is limited to a single country. The practical implications of the study highlight that this pandemic is a good moment to raise awareness among young people about food waste and we discuss possible strategies on this matter. Our research offers a new perspective on food waste in the conditions of current health crisis, and possible anticipated economic recession, in the future.

Keywords: Food waste, Food management, Covid-19, Consumer behaviour, Young people

1. Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has been the main concern and challenge for humanity, and will probably continue to be so for a long time. This pandemic, which started in China in 2019, has led, by November 2020 (WHO, 2020), to 45,968,799 infected people and 1,192,911 deaths. The end of this pandemic is difficult to predict and its effects, beyond those on public health, are disruptive and affect the industry, transportation, tourism and financial markets. The Covid-19 pandemic has severely influenced the labour market and jobs, education, family and social relations, as well as the politics and environment (Pourdehnad et al., 2020).

The evolution of the pandemic has also brought forward the issue of food security. Although no major food shortages were reported, some disturbances were felt, under the influence of restrictions on the movement of people, closure of certain businesses, restrictions on imports and exports, impairment of transport activities. According to Laborde et al. (2020), the pandemic affects all the four pillars of food security: availability, access (with the most direct and important impact), utilization (utilization of adequate nutrients) and stability (the possibility to permanently access food).

The rapid evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic, the lockdown imposed in many states and the arrival of the second wave in the autumn of 2020 had a significant impact on people’s lives. The insecurity, the unknown and fear intertwined to create a mix of new feelings and behaviours, different from those before. Under those circumstances, connected with the issue of food security, the issue of food waste in certain countries/certain social categories comes to public debate.

Initially, in March 2020, under the impulse of the alarmist messages of the authorities and the media, which presented empty shelves in supermarkets, but also due to the survival instinct, in many countries, people stocked up food, a behaviour that usually leads to food waste (Porpino et al., 2016).

After this first stage, there were premises to reduce food waste: the diminished income in many families, due to lockdown unemployment (both temporary and permanent); certain foods recorded a raise in prices; frequent family cooking, due to more time spent at home and restaurants being closed. The net effect of the pandemic on food waste will depend on its longevity, on the impact on the global economy, on the agri-food supply chain and on households (Lusk and Ellison, 2020), on measures taken by local authorities, regional, national and global pandemic management.

Food waste along with food loss have significant repercussions on food security, on the environment, but also on the global, regional and national economy (Abiad and Meho, 2018). Given its implications, food waste is a major challenge for responsible business and consumer behaviours (Grainger et al., 2018). Being a concept that can be studied from many perspectives, the literature presents different approaches to the determinants of food waste (Canali et al., 2016). Food waste studies showed that young people had a higher propensity to food waste (Lyndhurst, 2007; WRAP, 2014; Principato et al., 2015; Secondi et al., 2015; WRAP, 2019; Bravi et al., 2020).

An important category is represented by students, which unlike other young people, possess several characteristics which influence their food waste behaviour, such as education, lifestyle, buying habits, eating and storing food (especially when studying away from home).

In specialized literature, there is not much research on how students perceive food waste. Previous research on food waste among students falls into one of two categories. First, the direct research, aimed at investigating the psychological or social causes that govern the process of food waste. These studies include two features: on one hand, the sample was entirely composed of students (Mondéjar-Jiménez et al., 2016; Zepeda and Balaine, 2017; Heidari et al., 2018; Acheson, 2019; Aydın and Yildirim, 2020; Islam, 2020); on the other hand, the sample, while including students, was not fully represented by students (Graham-Rowe, 2014; Stancu et al., 2016; Nikolaus et al., 2018). Second, the indirect research, aimed at investigating forms of food waste among students, being focused on food waste in the social spaces of university campuses (Evangelinos et al., 2009; Kim and Freedman, 2010; Ahmed et al., 2018; Pinto et al., 2018; Abdelaal et al., 2019; Kasavan et al., 2021).

Our study will fill a gap in the theoretical and practical research. Its purpose is to investigate responsible behaviour of young people towards food waste in Romania and to identify the factors that determine such behaviour. The necessity of the study comes from the fact that Romania ranks 9th in Europe in terms of food waste, throwing 2.55 million tons of food annually, given that 4.5 million citizens face serious problems in the process of providing their daily food (CNEPSS, 2019). Most of the food waste comes from households (49%), the food industry being responsible for 37% (CNEPSS, 2019).

The rest of our paper is organised as follows: the next section is dedicated to a critical analysis of the state of the art in this field, based on which, we develop the research model and related hypotheses. In the third section, we unfold the methodology and in the subsequent section, we analyse the results. In section five, we discuss the theoretical and practical contributions, as well as, the limits of the research and at the end, we formulate the conclusions.

2. Theoretical background and hypotheses development

Food waste is a concept analysed in many studies, from multiple angles, by specialists in different fields. Many researchers studying food waste concluded that young people aged 18–34 are the age group that wastes food the most, compared to other age groups (WRAP, 2014). Young adults and especially young professionals waste significant amounts of food (Bio Intelligence Service, 2010).

Our research analyses the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the young people’s responsible behaviour to food waste.

We propose a conceptual model based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991), one of the most frequently used constructs in studies on the investigation of the causes of food waste behaviour and solutions to prevent it (Graham-Rowe et al., 2015; Mondéjar-Jiménez et al., 2016; Russell et al., 2017). The model considers action as a form of materialization of behaviour, the results of both motivation and willingness (Ajzen, 1991). The intention to perform the behaviour is determined by three other variables: the attitude in favour of performing the behaviour (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975), subjective norms and perceived behavioural control (Ajzen and Fishbein, 2000).

Attitude is considered as a favourable or unfavourable predisposition, or, we would add, as indifference, which is very common in food waste studies, towards a product, service or any other aspect of social life. Studies have shown three drivers that may be at the basis of individuals’ concern about food waste, drivers that differ from author to author: financial-waste of money, moral-guilt and a waste of good food (Lyndhurst, 2007); financial, health and environmental status (Visschers et al., 2016); financial, health and social (Schanes et al., 2018).

Subjective norms refer to the influence induced by the need to comply with social norms and customs, and the opinions of other people valued by the individual. Studies have shown that this construct does not have such a large impact on food waste behaviour (Graham-Rowe et al., 2015; Stefan et al., 2013), as explained by Quested et al. (2013) in that food waste is not a phenomenon observable by other individuals.

Perceived behavioural control includes the elements over which the individual has to have control in order to be able to manifest his behaviour. The possibility to plan the meals or to make a shopping list is an example of such factors (Visschers et al., 2016; Graham-Rowe et al., 2015).

In shaping the conceptual model, we also considered approaches that looked into food waste to be influenced by food related routines (Ș;tefan et al., 2013; Stancu et al., 2016; Hebrok and Boks, 2017). Food related routines that impact food waste may refer to the following: shopping routines (Ș;tefan et al., 2013; Ganglbauer et al., 2013; Ponis et al., 2017), reuse of leftovers (Koivupuro et al., 2012; Stancu et al., 2016); meal planning (Ș;tefan et al., 2013; Stancu et al., 2016); storage (Ganglbauer et al., 2013; Hebrok and Boks, 2017); checking inventories (Ș;tefan et al., 2013); cooking (Koivupuro et al., 2012; Ganglebauer et al., 2013; Stancu et al., 2016).

2.1. Responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste

Food waste will never be fully eliminated, because there will always be food that people forget in the fridge and they lose their organoleptic properties. Moreover, there will be situations in which we will buy unnecessary products, influenced by discounts and other marketing strategies. We define responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste as being the rational process of being aware of the possibility of food waste and the active actions that one takes in order to avoid food waste.

The issue of responsible behaviours towards food waste, to reduce and/or prevent food waste at the individual level, is quite little addressed in the literature (Quested et al., 2013; Mondéjar-Jiménez et al., 2016; Bravi et al., 2020). Food waste should not be seen as a single behaviour, but as the result of behaviours related to food’s journey into and through people’s home: planning, shopping, storage, preparation and consumption of food (Quested et al., 2013, p. 44). Given this fact, in order to reduce and/or prevent food waste at the individual and household level, it is necessary that each of these behaviours be approached responsibly.

A “positive” behaviour towards food waste can be obtained through three categories of activities: understand the date-labels on food, re-use of leftovers for new meals, a make a shopping list (Mondéjar-Jiménez et al., 2016).

An important condition for responsible behaviour is a well-informed and organized consumer. Given the fact that young people still live with their parents or have recently detached themselves from the “family nest”, we appreciate that they may not have consolidated certain food related routines, but it is also possible to show mimetic towards food routines in the family they come from. Through information, communication and awareness they can be oriented towards responsible behaviour of food waste. We must not lose sight of the fact that they have a certain food education, acquired in a formal or informal setting, a certain system of values already crystallized that may not be consonant with such responsible behaviour (Bravi et al., 2020).

2.2. Knowledge of food waste among young people

Knowledge of food waste among young people can be defined as the awareness, understanding, or information in relation to food waste, acquired by young people through experience or study. One of the main reasons of food waste behaviours in young people is a lack of awareness of the environmental and financial consequences of this phenomenon (Bio Intelligence Service, 2010).

The awareness and concern of young people in relation to food waste depend rather on economic motivations, than the environmental and health concerns. In order to be efficient, public campaigns to reduce food waste should be tailored to different young people groups, based on their knowledge, awareness and concern (Knezevic et al., 2019).

Wakefield and Axon (2020) consider that introducing the topic of food waste into school curricula could educate young people and raise their awareness of unsustainable food practices.

To be effective, institutionalized food waste education must start at a very young age, and countries such as France, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom understood and implemented such curricula at all levels of education (Priefer et al., 2016). School administrations must also ensure that children and young people do not come into contact with food waste within school. In many European countries, from an early age, children eat at the school canteen. Certain factors such as portion size, limited budgets and lack of motivation of service providers can lead to food waste in these school canteens (Priefer et al., 2016), with an obvious negative impact on the behaviour of young people.

Young people do not pay much attention to how they can optimize food consumption because they have limited knowledge about how to store food or how to prepare different types of food from the same ingredients (Acheson, 2019). At the same time, young people have little experience with cooking and thus, tend to cook portions that are too large to be eaten in one sitting and throw away the leftovers (Buzby and Hyman, 2012).

Parfitt et al. (2010) analysed food waste in several stages, from the pre-shop planning phase to the purchase of food products. The behaviour of young people is different at each stage and is influenced by various factors. Thus, in the buying process, the following factors are included: young people do not check their food stock (WRAP, 2007), do not make a shopping list (Lyndhurst, 2007) and they have a small proportion of their income allocated to food (Parfitt et al., 2010). In the food purchasing stage, young people do not usually follow their shopping list and tend to buy too much food in general or to impulse-buy items that they do not really need, at the same time failing to plan ahead their meals (Lyndhurst, 2007). Another factor that leads to food waste is that young people do not know how to store food correctly, which types of foods can be stored in cupboards, refrigerators and freezers and some of them do not even know how to operate their refrigerator correctly (WRAP, 2007).

Focusing on students, they tend to eat most, if not all, of their meals in university dining halls and thus, they do not have a lot of experience regarding grocery shopping for meals and at the same time, students living on university campuses might not have a refrigerator and are unable to store their food (Nikolaus et al., 2018). Deficiencies in food-related education of young people are revealed by many studies, starting from the misunderstanding of food labels (Principato et al., 2015). Thus, young people don’t have a clear understanding of “use by” and “best before” dates (Parfitt et al., 2010) and might unnecessarily throw away food (FAO, IFAD, WFP, 2014).

Food waste education, thou important, is not enough to produce real changes (Fοx et al., 2018). It represents the starting point of a complex anti-waste strategy, involving all food supply chain stakeholders (Annunziata et al., 2020).

We propose the following hypothesis:

H1

Knowledge of food waste among young people has a direct and positive influence on responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste.

2.3. Ethics of food waste among young people

Ethics of food waste among young people involves young people’s acceptance of food waste by referring to their own system of values, principles and social norms.

Food waste can be approached, as we have already pointed out, from multiple angles, including from an ethical point of view. The degree of awareness, understanding and embracing the ethical attitudes related to food waste can lead to a change in behaviours; respectively can lead to a transition to a sustainable, socially responsible behaviour.

From the religious perspective, food is considered a “sacrament” and food waste as a “sacrilege” (Gjerris and Gaiani, 2013). Food waste is defined as “edible food thrown out from private households” (Gjerris and Gaiani, 2013, p. 14). Starting from this definition, two main reasons that generate ethical issues were identified: food waste is seen as a waste of resources, which could be used to alleviate the hunger problem facing hundreds of millions of people globally; food waste produces negative effects in terms of limited resources, biodiversity, climate change (Gjerris and Gaiani, 2013). In addition to these two considerations, cultural memory has retained, even in very rich societies, the remembrance of the times when finding the necessary food was a real problem.

People that associate food waste with ethical values, think about people that suffer from hunger (Hebrok and Boks, 2017). Food waste is an ethical issue if we consider that hundreds of millions of people in the world suffer from chronic malnutrition. Reducing food waste would alleviate this global problem (Bravi et al., 2020).

Lehtokunnas et al. (2020) analyse four dimensions of ethical work related to food waste reduction practices as following: ethical substance (unsustainable consumption practices and the emotions generated by them); mode of subjectivation (observing behaviour and education from family or others; awareness that many people face a lack of food; environmental considerations); self-forming activity (changing consumption behaviour to eliminate habits that lead to waste, changing the attitude towards food through various remedies offered by friends, family, online); telos (creating a balanced relationship with oneself, others and the environment).

Evans (2011, p. 552) considers that the orientation towards responsible consumption can be achieved by returning to frugality, a solid moral dimension. He states, “to be frugal is to be moderate or sparing in the use of money, goods and resources with a particular emphasis on careful consumption and the avoidance of waste”. The article differentiates between frugality and thrift, starting from the specific context of the 2007–2009 financial crisis. Periods of crisis can lead to restraint, but not implicitly a return to frugality. Evans (2011) shows that such a period is unlikely to irreversibly change consumption patterns and lead to a stable orientation towards frugality, in the absence of social, political, economic, cultural and technological changes.

Next, we will briefly present the results of studies that analyse the ethical aspects related to food waste on samples of young people who also included students. One such study, conducted by Graham-Rowe et al. (2014), interviewed 15 subjects, students and non-students. One of the motivations identified to minimize waste is to do the “right” thing. The interviewees presented food waste as wrong thing, from several points of view, including: a point of view from a past in which waste was not tolerated, accepted or possible, another transmitted by family or friends; a more recent point of view, resulting from the awareness of the negative impact of food waste on the environment and resources depletion.

Stancu et al. (2016) analyse the factors influencing food waste, using a sample of 1062 respondents, including students. One of the results of the study was that moral norms do not make a major contribution to food waste behaviour. However, the authors treat this result with reservations, and addressing the issue from a different perspective is proposed as a future research direction.

Aydın and Yildirim (2020), conducting a study on a sample of 328 students from Turkey, found that: moral attitudes have a direct effect on food waste behaviour and eating habits, shopping habits, knowledge about food conservation; shopping habits mediate the relationship between moral attitudes and food waste behaviour; knowledge of food conservation mediates the relationship between moral attitudes and shopping habits. We posit the following hypotheses:

H2

Knowledge of food waste among young people has a direct and positive influence on ethics of food waste among young people.

H3

Ethics of food waste among young people has a direct and positive influence on responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste.

2.4. Young people’s perception of food waste’s impact on the environment

We focus on the issue of young people’s perception of food waste’s impact on the environment, considering that, recently, some researchers have concluded that young people are becoming increasingly concerned about the impact of food waste on environment (Bhatti et al., 2019).

Young people are more aware of the extent to which food waste affects the natural environment; they represent the generation that will intensify efforts to adapt their behaviours to the needs of environmental conservation and will create new solutions to mitigate the negative impact that the habits of the population cause to the environment.

Based on focus group research on young Americans regarding the wasted food, Nikolaus et al. (2018) conclude that the perceptions, beliefs and behaviours of young students between 18 and 24 years vary depending on the subjective aspects, but also the type of residence in which they live. These criteria alter young people’s perception of the interdependence between the two variables, wasteful behaviour and environmental quality.

Regarding the recent lockdown situation, Principato et al. (2020) conducted a survey to highlight that young Italians who have introduced good food management actions, succeeded to significantly decrease food waste, reducing its negative effect on the environment through a number of good practices (e.g. lists of pre-prepared purchases, constant checking of supply reserves, improving the planning of cooking operations). Obviously, the changes in food consumption behaviour have changed the quantities and the food assortment, changing also the impact that the food waste has on the environment. The conclusion is that the lockdown period positively influenced the behaviours of young people, generating a lower environmental impact in large cities and places perceived as dirty (Principato et al., 2020).

Regardless of the factors highlighted by the literature review, changing the behaviours of young people in the direction of reducing food waste and its impact on the environment can be achieved only with the help of retailers and marketing managers (Bravi et al., 2019).

However, consumers are still concerned about reducing food waste by being stimulated mainly by the economic implications in terms of costs and benefits and less by the awareness of environmental protection (Baker et al., 2009) or environmental values (Barr, 2007).

The COVID-19 crisis may be a wake-up call on the potential impact of food waste on the environment (Sarkar et al., 2020). Young people are called to contribute to a cleaner environment by reducing food waste. As a result, we predict the following hypotheses:

H4

Knowledge of food waste among young people has a direct and positive influence on young people’s perception of food waste’s impact on the environment.

H5

Young people’s perception of food waste’s impact on the environment positively influences the responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste.

2.5. The influence of COVID-19 crisis on food shopping and food consumption of young people

The influence of COVID-19 crisis on food shopping takes into account the food shopping behaviour of young people as a consequence of COVID-19 crisis. Until the COVID-19 crisis, shopping routines for food were somehow an automatic process. The crisis prompted a process of reflection and behavioural changes that we try to evoke in our variable. The pandemic led to impulsive shopping, overstocking, and travel restrictions, all affecting the shopping routines.

As we have already pointed out, the pandemic crisis generated by COVID-19 caused fluctuations and short-term changes in food consumption habits. On one side, some of these changes tend to exacerbate food waste: overcooked food, exceeding long-term storage in the freezer, overbuying (Borsellino et al., 2020). On the other side, the pandemics favoured the reduction of food waste: less frequent shopping, more carefully planned meals, consumption of the food left in the cupboard for a long time (Borsellino et al., 2020).

Certain changes in the food consumption were documented in the literature. First, increased consumption of food prepared at home to the detriment of that consumed in/from the city, which led to waste, since the household units do not have the means to measure and standardize portions (Aldaco et al., 2020). As access to some products was restricted by overstocking or travel restrictions during the quarantine period (e.g. market access for traders), stock up food increased, which might contributed to food waste, by discarding the expired products. Another problem documented was the impact of COVID-19 on food supply. On the short term, prices increased and the lack of products might occurred due to logistical restrictions. In the end, we can expect new ways of online shopping and products adaptation for a longer shelf life (Richards and Rickard, 2020).

Calories intake during lock-down periods tend to go up, which also contributes to a greater impact on the environment and natural resources (Batlle-Bayer et al., 2020). On the other hand, concerns about maintaining health and strong immunity can determine an increase in the consumption of organic products, fruits and vegetables, and other healthy products (Ben Hassen et al., 2020).

Hence, we developed the following hypotheses:

H6

The influence of COVID-19 crisis on food shopping of young people has a direct and positive influence on responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste.

H7

The influence of COVID-19 crisis on food shopping of young people has a direct and positive influence on ethics of food waste among young people.

H8

The influence of COVID-19 crisis on food shopping of young people has a direct and positive influence on young people’s perception of food waste’s impact on the environment.

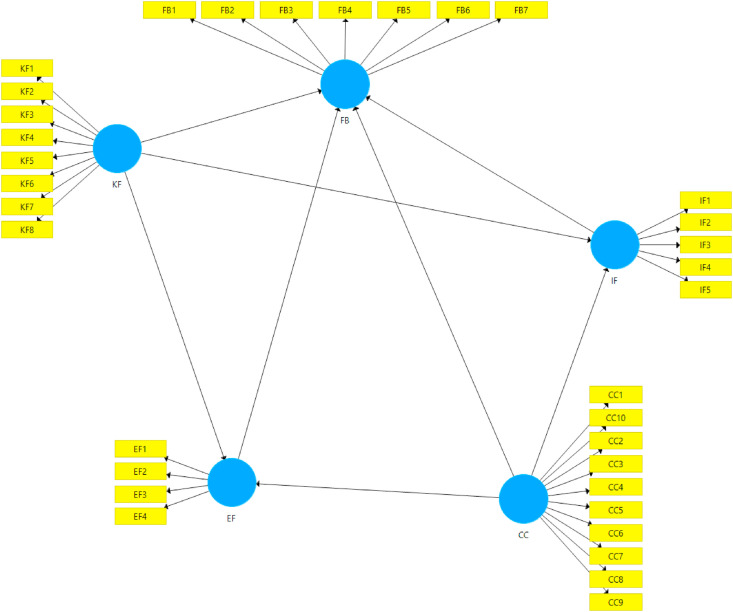

Our theoretical model is presented in Fig. 1 .

Source: Authors’ contribution using SmartPLS3software

∗ FB: Responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste; KF: Knowledge of food waste among young; EF: Ethics of food waste among young people; IF: Young people’s perception of food waste’s impact on the environment; CC: The influence of COVID-19 crisis on food shopping of young people.

Fig. 1.

The proposed theoretical model.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Sample

The sample was selected from the students of several Romanian universities. We sent an email invitation to a number of 483 students, inquiring about the possibility to participate in a study about food waste. Students were requested to complete an online form and extra credit courses were offered as incentive. We received a number of 461 questionnaires; out of each, we deducted those 86 that had incomplete answers. The final sample size is 375 respondents, age 18–40, most of them under 35 years old, enrolled at bachelor, master and PhD studies. The main category, by educational level is Bachelor students (41.86%) and by gender, the females (59.73%) are predominate (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

The structure of the sample.

| Gender |

Study |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Bachelor | Master | PhD |

| 151 | 224 | 157 | 128 | 90 |

| 375 | 375 | |||

University students are suitable for academic research to analyse food waste. They have the potential to answer self-reported questions, to evaluate complex behaviour and to provide reliable data (Knezevic et al., 2019). Previous representative studies used samples of students (Principato et al., 2015; Islam, 2020; Aydın and Yildirim, 2021).

3.2. Measures

To measure the variables, we identified in the literature reliable items and we adapted the items to our research purpose. Where we could not find adequate items in the literature, we used a two-step approach to develop the measures (Langerak et al., 2004). First, we proposed a set of items, through repeated discussion and negotiation among the authors. In the second stage, the potential items were tested among ten subjects of the studied population to ensure clarity and concision. For all items, we used a five-point Likert scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). The variables and the items were adapted from the literature as following:

FB: Responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste was adapted from Stefan et al. (2013), Mondéjar-Jiménez et al. (2016).

KF: Knowledge of food waste among young people was adapted from Principato et al. (2015).

EF: Ethics of food waste among young people was adapted from Visschers et al. (2016), Aydın and Yildirim (2021).

IF: Young people’s perception of food waste’s impact on the environment was adapted from Stancu et al. (2016).

CC: The influence of COVID-19 crisis on food shopping of young people is own scale.

To test our model we used structural equation modelling with SmartPLS3 software (Ringle et al., 2015). We chose to use the SEM-PLS model because it is flexible and can handle many independent variables at the same time (Hair et al., 2016). The SEM-PLS relies on both primary and secondary data and it does not require large sample size (Chin and Newsted, 1999). Moreover, as an exploratory methodology, it offers data screening, and reflective and formative indicators to construct. The bootstrapped method can be used to evaluate the overall model fit (e.g. R2 values and relationships among constructs) as recommended by Dijkstra, and Henseler (2015). Finally, the arguments of Ramli et al. (2018) are in consensus with the objective of our study, to handle problems of multi-collinearity and to minimize the problem of co-linearity or redundancy among the predictor variables.

In Table 2 , we evaluated the reliability values (outer loading) which, according to Hair et al. (2017), must be greater than 0.70.

Table 2.

Loadings values.

| Variables/Items | Loadings | Observations |

|---|---|---|

| FB: Responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste | ||

| FB1. When I don’t consume entirely a food product, I pack it and store it in the fridge to eat later | 0.783 | >0.7 |

| FB2. When I don’t consume entirely a food product, I donate it to charity | 0.203 | <0.7 → Deleted |

| FB3. In the family, I eat food that is not prepared on the same day | −0.150 | <0.7 → Deleted |

| FB4. When I have perishable foods that I can’t eat, I look for solutions to share them with loved ones (friends, other family members, neighbours) | 0.716 | >0.7 |

| FB5. When I don’t like a food product, I don’t throw it away | 0.155 | <0.7 → Deleted |

| FB6. I usually buy food for current consumption on discounts and I consume it completely | 0.145 | <0.7 → Deleted |

| FB 7. I usually buy occasional food on offer and I try to consume it completely | 0.792 | >0.7 |

| KF: Knowledge of food waste among young people | ||

| KF1 Food waste is a topic analysed in the disciplines studied in college | 0.389 | <0.7 → Deleted |

| KF2. I’m concerned about food waste | 0.381 | <0.7 → Deleted |

| KF3. I learned about food waste and the importance of preventing it at school | 0.830 | >0.7 |

| KF4. In my family, I was educated to avoid food waste | 0.828 | >0.7 |

| KF5. I get involved in reducing food waste in my family | 0.877 | >0.7 |

| KF6. I talk to friends and colleagues about reducing food waste | 0.740 | >0.7 |

| KF7. Food waste cannot be avoided | 0.144 | <0.7 → Deleted |

| KF8. I am not aware of any concerns about reducing food waste ∗ Reverse | 0.162 | <0.7 → Deleted |

| EF: Ethics of food waste among young people | ||

| EF1. Food waste is a phenomenon that is a matter of ethics | 0.757 | >0.7 |

| EF2. Buying food on a regular basis that exceeds one’s own needs reflects a lack of ethical values | 0.794 | >0.7 |

| EF3. My moral principles do not allow me to throw away food | 0.857 | >0.7 |

| EF4. The level of culture and education of each individual influences food waste | 0.788 | >0.7 |

| IF: Young people’s perception of food waste’s impact on the environment | ||

| IF1. Food waste has a negative impact on the environment | 0.819 | >0.7 |

| IF2. To reduce waste products, we must reduce food waste | 0.733 | >0.7 |

| IF3. Packaging must be used to allow long-term preservation of food products | 0.882 | >0.7 |

| IF4. In order to reduce the impact of food waste on the environment, individuals should be required to selectively sort their waste | 0.906 | >0.7 |

| IF5. The role of the education system is to make young people aware of the negative impact that food waste has on the environment | 0.703 | >0.7 |

| CC: The influence of COVID-19 pandemic on food shopping | ||

| CC1. During the COVID-19 pandemic, my purchasing behaviour concerning the reduction of food waste became more thoughtful. | 0.739 | >0.7 |

| CC2. When I go shopping I buy more products in order to reduce the activities related to the buying process | 0.709 | >0.7 |

| CC3. When I go shopping I buy more products in order to create a stock | 0.333 | <0.7 → Deleted |

| CC4. When I go shopping I buy the necessary products for a short period of time, maximum 3 days | 0.427 | <0.7 → Deleted |

| CC5. The purchases I make are based on the available budget | 0.711 | >0.7 |

| CC6. The purchases I make are based on the current needs | 0.781 | >0.7 |

| CC7. I shop in the big retail stores | 0.705 | >0.7 |

| CC8. I shop in stores close to home to avoid contact with many people | 0.402 | <0.7 → Deleted |

| CC9. I shop online because they are more convenient and avoid contamination with COVID-19 | 0.211 | <0.7 → Deleted |

| CC10. I have wasted food during the COVID-19 pandemic | 0.024 | <0.7 → Deleted |

Analysing the results depicted in Table 2, we notice that a series of items have a value of less than 0.7 and for the validation of the evaluation scale, we have eliminated them.

Next, we proceeded to evaluate the reliability and validity of the latent variables using the indicator Cronbach’s Alpha (CA), composite reliability (CR) and the Dijkstra-Henseler (2015) statistics (rho_A) (Table 3 ). To assess whether the indicators of a variable are positively correlated, the Average Variance Extract must be greater than 0.5 (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017).

Table 3.

Construct reliability and validity.

| Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | 0.811 | 0.823 | 0.868 | 0.568 |

| EF | 0.811 | 0.814 | 0.876 | 0.640 |

| IF | 0.868 | 0.874 | 0.906 | 0.660 |

| KF | 0.846 | 0.867 | 0.896 | 0.684 |

| FB | 0.667 | 0.679 | 0.816 | 0.598 |

Analysing the data in Table 3, we notice that for every variable, AVE it is higher than 0.5, which supports the existence of a convergent validity between the variables. Values higher than 0.7 are also recorded for rho_A and composite reliability indicator Cronbach Alpha’s score is higher than 0.7 for four variables, the only variable that has a score below 0.7 is FB with a value close to 0.7 and 0.667, respectively. To strengthen the validity of the model it is necessary to analyse the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) which must have values below 0.85 (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017), as presented in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT).

| CBC | EF | IF | KF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | ||||

| EF | 0.577 | |||

| IF | 0.738 | 0.876 | ||

| KF | 0.503 | 0.775 | 0.671 | |

| FB | 0.590 | 0.900 | 0.817 | 0.826 |

The analysis of Table 4 shows that, if we consider the threshold of 0.85 suggested by Clark and Watson (1995) and Kline (2011) there are potential discriminant validity problems in this model between IF-EF variables and between FB-EF variables. If we take into consideration the research of Gold et al. (2001); Teo et al. (2008) and Henseler et al. (2015) the threshold for HTMT is 0.90 and in this case the all values are under or equal with this threshold. Therefore, there are no discriminant validity problems.

Our research continues with the evaluation of the structural model by calculating the R Square indicator, which has values from 0.467 to 0.575 (moderate to good).

The model fits the sample data fairly well as NFI (normed fit index) is well above 0.7, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.079, the model is significant (Table 5 ).

Table 5.

Model_Fit - fit summary.

| Saturated Model | Estimated Model | |

|---|---|---|

| SRMR | 0.079 | 0.080 |

| d_ULS | 1.512 | 1.831 |

| d_G | 0.509 | 0.568 |

| Chi-Square | 1036.647 | 1102.856 |

| NFI | 0.770 | 0.755 |

We continue our analysis with the latent variables correlations (Table 6 ).

Table 6.

Latent variable correlations.

| CC | EF | IF | KF | FB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | 1.000 | 0.479 | 0.628 | 0.436 | 0.449 |

| EF | 0.479 | 1.000 | 0.741 | 0.648 | 0.681 |

| IF | 0.628 | 0.741 | 1.000 | 0.589 | 0.632 |

| KF | 0.436 | 0.648 | 0.589 | 1.000 | 0.633 |

| FB | 0.449 | 0.681 | 0.632 | 0.633 | 1.000 |

From the analysis of Table 6 we see that the strongest correlation is between EF and IF (0.741) demonstrating that the ethics of food waste among young people is associated with the young people’s perception of food waste’s impact on the environment. This correlation emphasizes the responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste and their desire to help reduce the negative impact of food waste on the environment by adhering to ethical principles.

Another strong correlation is that between EF and FB (0.681) which comes to strengthen the positive association of the ethics of food waste among young people with the responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste.

The degree of knowledge of food waste among young people is positively associated with the responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste, which suggests that an increase in the knowledge about the food waste issues can lead to an increase in responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste (KF-FB = 0.633).

The lowest correlation was recorded regarding the association of the crisis generated by COVID-19 on the buying behaviour of young people with the degree of Knowledge of food waste among young people (CC-KF = 0.436).

The inner model is used to show, in a preliminary phase, the level of significance in hypothesis testing. In our case, the inner model includes all five variables and (Hair et al., 2014) and their values are 1 that prove the significance of the model.

4. Findings and hypotheses testing

Next step, in order to measure the level of significance in hypothesis testing, is to analyse the significance of relationship between constructs (Table 7 ) using t-test analysis and p-values from path coefficients.

Table 7.

Path coefficients - mean, STDEV, T-Values, P-Values.

| Hypotheses | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KF -> FB =H1 | 0.307 | 0.305 | 0.051 | 5.992 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| KF -> EF =H2 | 0.542 | 0.546 | 0.037 | 14.719 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| EF -> FB =H3 | 0.430 | 0.432 | 0.052 | 8.216 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| KF -> IF =H4 | 0.216 | 0.216 | 0.049 | 4.396 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| IF -> FB =H5 | 0.321 | 0.322 | 0.051 | 6.250 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| CC -> FB =H6 | 0.109 | 0.109 | 0.044 | 2.473 | 0.014 | Accepted |

| CC -> EF =H7 | 0.243 | 0.244 | 0.043 | 5.706 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| CC -> IF =H8 | 0.390 | 0.387 | 0.046 | 8.417 | 0.000 | Accepted |

We notice that for all hypotheses the values of t-test analysis are higher than 2.4 and the values of p-values are within normal limits (less than 0.05 - Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017), which leads to the validation of all hypotheses.

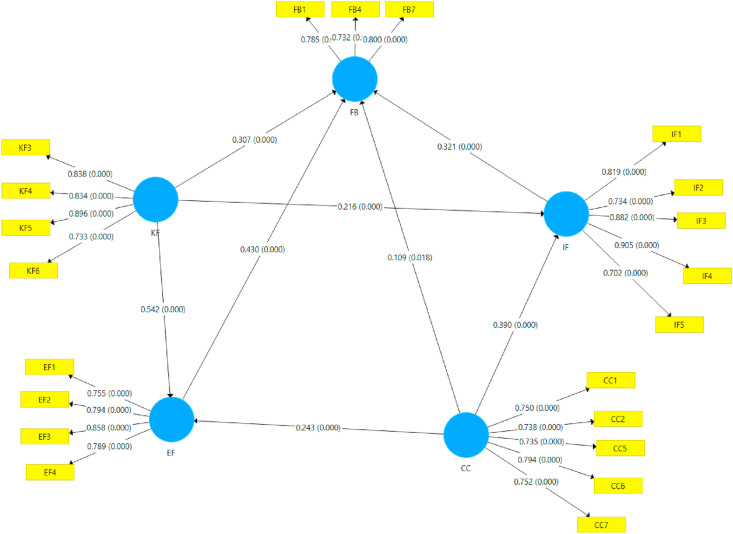

Fig. 2 shows Bootstrapping results and it reflects the significance of relationship between constructs.

Hypothesis 1

is validated (t = 5.992, p = 0.000). Our research showed that food waste cannot be avoided, but the more knowledge about food waste young people have, the more they tend to change their behaviour and pay more attention to the manifestations of this phenomenon. Sources of information and knowledge among young people are diversified and include families observed behaviours and discussions; schools transmitted information and peer-to-peer conversations.

Nikolaus et al. (2018) considered that the students tend to change their perception regarding food waste when they start to manage their own budget and buying their own groceries, as opposed to eating in a dining hall where the food provisioning and management are being taken care by others. Therefore, another source of knowledge formation is through experience and trial and error, because the illusion of knowledge and a good-deal perspective lead sometimes to undesired outcomes. For example, young people are sensitive to special offers and sales promotions, which may generate overconsumption (Mondéjar-Jiménez et al., 2016; Ghinea and Ghiuta, 2019). Brook Lyndhurst (2007) and Williams et al. (2012), found out that high sensitivity to food hygiene and a poor understanding of best before and use by dates on food labels are predictors for inadequate shopping planning, thus, leading to food wasting behaviour.

Hypothesis 2

is validated (t = 14.719, p = 0.000). A particular attitude can be influenced if an individual gains knowledge about this issue (Visschers et al., 2016). The ethics of food waste is positively influenced by the knowledge about food waste. Our findings showed that family has a high degree of influence on this matter. In this respect, we showed that family, colleagues and friends influenced students’ perception and intention regarding food waste. The more young people are aware and gain knowledge about food waste, the more they internalize this matter into their own moral system of beliefs and convictions (Aydın and Yildirim, 2021). Moreover, Principato et al. (2015, p.733) assume that “a greater awareness concerning food waste can be positively linked to a rationalization of purchases”.

Hypothesis 3

is validated (t = 8.216, p = 0.000). The COVID-19 pandemic emphasized the relationship between the ethics of food waste among young people and the responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste, contributing to raising awareness of the importance of food waste reduction. Moral norms have begun to be recognized as those mechanisms that can influence the responsible behaviour of young people regarding the reduction of food waste, which is in line with recent research conducted during the pandemic crisis by Aydin and Yildirim (2021).

Hypothesis 4

is validated (t = 4.396, p = 0.000). The more knowledge young people have about food waste, the more they realize that it affects not only their personal budget, but also has a negative impact on the environment. The COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to the individual responsibility of young people to maintain a clean and healthy environment (Principato et al., 2020). Knowing the causes of environmental destruction and identifying food waste among them, might determine higher levels of awareness among young people. Knowledge influence responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste both directly and indirectly. An increase in knowledge about responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste triggers positive associations with ethical norms and environmental concerns that brings about less food waste. Williams et al. (2012), Parfitt et al. (2010) and Barr (2007) concluded that young people who care about their environment and their community are less likely to waste food.

Hypothesis 5

is validated (t = 6.250, p = 0.000). This confutes previous studies that did not find a link between the two variables (Stefan et al., 2013). Regarding the implications of the relationship between environmental quality and food waste habits, among the beliefs of young people, the most robust are the awareness of the need to selective waste collection and the promotion of food packaging solutions that allow long-term preservation. Confirmation of this positive relationship between young people’s perception of food waste’s impact on the environment and their responsible behaviour regarding food waste is not at all surprising if we take into consideration that young people are connected to online mobilizing movements and react very well to the messages of influential leaders (for example, Greta Thunberg), adhering to civic initiatives. Our findings are supported by the more recent studies of Stancu et al. (2016) and Principiato et al. (2020). It seems that in the light of changes caused by the COVID-19, young people became aware that food waste has a negative impact on the environment.

Hypothesis 6

is validated (t = 2.473, p = 0.014). The COVID-19 pandemic led to changes in the consumption behaviour of young people, in the sense of caution about food waste. Fear and concern for tomorrow, coupled with income insecurity have led to better allocation of available resources in all areas, including food. These findings are aligned with other studies (Principato et al., 2020; Miles, 2020) and are also in line with those of Stefan et al. (2013), who states that an individual’s level of concern regarding the economic consequences of food waste directly influences his/her food wasting behaviour. Many people have found themselves losing their jobs and facing a difficult economic situation (Nicola et al., 2020), which can contribute to the intensification of concerns about reducing food waste.

Hypothesis 7

is validated (t = 5.706, p = 0.000). Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on food shopping positively affects the ethics of food waste among young people. According to cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957), individuals might seek to adapt their attitudes to cope with the current behaviour. In time of crisis, action is essential, behaviour is the first, and then it follows the alignment of the attitudes. The COVID-19 pandemic has made us more responsible and made us return to moral values, both in the sphere of consumption and other aspects of human life (Jribi et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic determines changes in the attitudes, such as the ethics of food waste behaviour. By investing in continuing education, increasing the level of responsibility and understanding the role of the man on earth, individuals can strengthen the ethics of the buying and consuming process (van Gefen et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic contributed to a raise in the awareness toward the ethics of food waste among young people.

Hypothesis 8

is validated (t = 8.417, p = 0.000). Although the impact of COVID-19 on economic activity and society in general is negative, the impact on the natural environment and biodiversity is beneficial (Sarkar et al., 2020; Eroğlu, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic brought a growing concern among consumers, including young people, about environmental issues. This is supported by the suggestive graphic images with the reduction of pollution due to the decrease of economic activity (Sarkar et al., 2020; Khurana et al., 2021). Young people have understood that their actions have an impact on the environment; therefore, behavioural changes are necessary. The COVID-19 pandemic challenged the consumers to consider carefully the food waste’s impact on the environment.

Just like knowledge, the COVID-19 pandemic influenced responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste, both directly and indirectly, mediated by the ethics of food waste and by the perception of food waste’s impact on the environment. Despite its negative economic and societal impact, the raise in ethics and environmental concerns associated with the COVID-19 pandemic might lead to a reduction in food waste behaviour of young people and to actions that are more responsible.

Fig. 2.

SmartPLS Bootstrapping results.

Source: Data processed with SmartPLS3

5. Discussions

The theoretical implications of the research consist in filling the gap in literature about the way in which young people perceive the impact of food waste both on their consumer behaviour and on the environment. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food waste is mixed. If, on the one hand, in our study we identified a positive link between the COVID-19 pandemic and behaviours for rational consumption, environmental protection and for improving the ethics of food waste among young people. However, the insecurity associated with a crisis can lead to overconsumption and overstocking. Thus, we suggest that the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on food waste had an impact for just a short period, and then, as things began to converge to “normality”, the positive effects documented in the study would prevail.

One of the contributions of the research was to test the validity of the TPB model in relation with food waste in the context of a crisis triggered in the consumer environment. At origin, The TPB model is based on the factors proximal to consumers. However, the influence on behaviour of distal factors at the macro level cannot be ignored (Boulet et al., 2020). The characteristics of crises, such as COVID-19, completely turn around the consumer behaviour, which calls into question models developed and validated in regular consumption contexts. The magnitude of the crisis induced by the COVID-19 pandemic is indisputable. Our research showed that, despite an initial aggressive process of food shopping and storage, in order to cope with periods of quarantine and lockdown, young people preserved their attitude towards a responsible behaviour towards food waste. This proves that among young people, ethics and concern for environmental protection have prevailed over the survival instinct triggered by the crisis.

The practical implications of the research are multiple, and it provides useful information related to young people perception of food waste. This study contributes to the identification of those strategic action points that can contribute to raise awareness of food waste among young people.

At practical level, our paper has implications for individuals and policymakers. For young people, the influence of COVID-19 pandemic on food shopping contributes to re-alignment with internal values, ethical norms and leads to responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste. Food shopping under COVID-19 is a more thoughtful process, with high consideration to budget and needs. As the world stopped during the initial phases of COVID-19, this could have been a moment for self-reflection and revision of ethical and environmental attitudes.

5.1. Policies implications and guidelines

Our study developed a framework for understanding the factors that influence responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste. Policy makers can approach these factors as a tool to implement those actions that will lead to desired outcomes.

Knowledge of food waste among young people is at the base of the design of any actions plan. Two things are essential: what knowledge is acquired and how it is transmitted. A variety of curricula can be implemented including: nutrition courses, responsible consumption courses, financial educations, ethics, environmental protection, and others. There is a solution to combine responsible consumption courses with financial education courses. In this way, the development of financial knowledge is plausibly intertwined with knowledge about sustainable consumption, and the two ways of thinking are, in the end, mutually reinforcing. Saving is a pillar of financial education that involves eliminating any waste, including food waste. The financial dosage of a saving plan requires creative solutions to do more with less, including a food shopping and consumption plan. In order to obtain a responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste, efforts should be done to increase the knowledge of this sensitive issue among young people using multiple communications channels such as school classes, public media, social media and other informal channels (Principiato et al., 2015). Imperatives should be avoided; instead, influencers can contribute to knowledge dissemination based on their affective relationships with young people.

Young people’s perception of food waste’s impact on the environment can be enhanced in the same ways as the transmitted knowledge. Theoretical insights need to be combined with a hands-on approach. Young people need to participate in thematic visits in environmentally affected areas, where access to water and food is problematic. Their immersion, for a week or more, in these impaired areas will certainly lead to a change in thinking and an embrace of pro-sustainability attitude. Volunteer assignments, in which young people cook for disadvantaged groups under a given budget or design a menu with limited resources, will make them have a different perspective on food waste. Social marketing campaigns can address the environment protection theme and might do that along with popularization of the actions of recognized ecologists, such as young ecologist Greta Thunberg. This can contribute not only to strengthen pro-environmental attitudes, but also it can start to produce incremental behaviour changes. In order for good practices to be maintained after the pandemic, there is a need for awareness and information campaigns targeted on young people (Principato et al., 2020), highlighting the individual and cooperative benefits to act environmentally (Brizi and Biraglia, 2020).

Topics about the ethics of food waste among young people should be included in the multitude of ethical studies that students pursue across their school years. Non-lucrative bodies or religion organizations can also transmit ethical values. Concerted actions by socialization agents, such as family and the circle of friends, are required to induce and develop the moral values about food waste. For example, the WRAP study of young people in the UK found that approximately 42% of respondents had discussed food waste with friends, family and colleagues in the last 6 months (WRAP, 2019).

Our policy proposals are in line with The Farm to Fork Strategy, launched in the spring of 2020 by The European Commission, as part of “The European Green Deal”. One of the stakes of this strategy is the goal of halving per capita food waste by 2030: The European Commission (2020, p. 14) will set a baseline and propose legally binding targets to reduce food waste across the EU.

5.2. Limitations and future research

The Theory of Planned Behaviour has its own explanatory power when dealing with intentions that do not always transpose into actual behaviour (Stefan et al., 2016). The real behaviour mighty be subject to other possible influences that are not contained in our model, such as economic and budgetary constraints, number of household members, direct or indirect implication in shopping and cooking routines. Focusing on conscious attitudes and behaviour, The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) does not account for automatic, take for granted influences on behaviour (Visschers et al., 2016). Meta-analytical research has highlighted the wide application of the TPB model in the field of responsible behaviour (Bamberg and Möser 2007; Maki and Rothman 2017).

Other possible limitation is related to the non-probability sampling technique leading to a sample size that is limited to 375 respondents, all from the same country, Romania. Another limitation results from the fact that we appealed to remembrance and used self-reported questions, instead of other possible directly observed responsible behaviour toward food waste. Respondents had to answer delicate questions about food waste and ethical attitudes, therefore responses might be biased due to respondents’ impulse to hide the actual behaviour (Aydın and Yildirim, 2021). Causality relationships in the model need to be treated with caution, as correlations among variables allow for reversed directions. For example, responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste might be as well the result of ethical and environmental attitudes’ changes.

The complexity of food waste research requires further studies to gain more and valuable knowledge into the matter. Our paper open the avenue for future possible research directions. First, the newly introduced concept of responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste can be analysed in various contexts and models, for example across a different age span or different countries. Other studies might seek to confirm and to develop the explanatory power of this concept.

Second, the proposed model can be developed by adding other explanatory variables, which could influence the responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste (e.g. health risks, maintaining the city cleanness, compliance measures and others). Third, our study took into consideration the impact of COVID-19 shortly after its occurrence. Future studies are need to assess the impact of COVID-19 on the long run and weather the presently observed changes are stable. In line with this, further studies might analyse if the current changes in the behaviour and attitudes of the young people, will be present in their life for a longer time. Fourth, responsible behaviour of the young people towards food waste can have different valences and meanings across cultures and state of economic developments and these needs further appraisal. Fifth, in the light of current research, the evaluation of the social marketing campaigns proposed after COVID-19 in relationship with food waste, need to be approached. It is possible that, due to the multitude of campaigns associated with COVID-19, peoples’ resilience and willingness to cooperate to be at minimum, and therefore the campaigns can miss their goals.

6. Conclusions

The present study analysed the food waste behaviour of young people in the aftermath of COVID-19 pandemic. The findings suggest that responsible behaviour of young people towards food waste is positively influenced by the knowledge of food waste among young people, the ethics of food waste among young people, young people’s perception of food waste’s impact on the environment and the influence of COVID-19 crisis on food shopping of young people. Despite the initial crisis’s challenges and fear of the unknown, food shopping of young people did not lead to food waste. Contrarily, young people adapt their food shopping to reduce food waste. Ethical values and pro-environmental attitudes sustain the responsible behaviour of young people towards food waste. Therefore, initiatives are required to strengthen these attitudes of young people. The results show that a crisis is a moment in which positive attitudes and behaviours are reinforced. Policy makers should capture the momentum and design policies that take advantage of young people’s receptivity towards new information and knowledge. Knowledge of the causes, forms, and consequences of food waste is at the foundation of any responsible attitudes and behaviours of young people towards food waste. Formal and informal knowledge, transmitted to young people through a variety of channels, can contribute to raise awareness about food waste, to build attitudes and to shape behaviours.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Adriana Burlea-Schiopoiu: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Conception and design of study: analysis and/or interpretation of data: revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Radu Florin Ogarca: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Funding acquisition, Conception and design of study: acquisition of data: analysis and/or interpretation of data: Drafting the manuscript: revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Catalin Mihail Barbu: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Funding acquisition, Conception and design of study: acquisition of data: analysis and/or interpretation of data: Drafting the manuscript: revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Liviu Craciun: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Funding acquisition, Conception and design of study: acquisition of data: analysis and/or interpretation of data: Drafting the manuscript: revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Ionut Cosmin Baloi: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Funding acquisition, Conception and design of study: acquisition of data: analysis and/or interpretation of data: Drafting the manuscript: revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Laurentiu Stelian Mihai: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Funding acquisition, Conception and design of study: acquisition of data: analysis and/or interpretation of data: Drafting the manuscript: revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: Approval of the version of the manuscript to be published.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Handling editor: Dr Sandra Caeiro

References

- Abdelaal A.H., McKay G., Mackey H.R. Food waste from a university campus in the Middle East: drivers, composition, and resource recovery potential. Waste Manag. 2019;98:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2019.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abiad M.G., Meho L.I. Food loss and food waste research in the Arab world: a systematic review. Food security. 2018;10(2):311–322. [Google Scholar]

- Acheson C. Food waste: the student perspective. 2019. https://www.zerowastescotland.org.uk/sites/default/files/Food%20Waste%20-%20A%20Student%20Perspective.pdf

- Ahmed S., Byker Shanks C., Lewis M., Leitch A., Spencer C., Smith E.M., Hess D. Meeting the food waste challenge in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High Educ. 2018 doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-08-2017-0127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I., Fishbein M. In: Stroebe W., Hewstone M., editors. vol. 11. Wiley; Chichester: 2000. Attitudes and the attitude-behaviour relation: reasoned and automatic processes; pp. 1–33. (European Review of Social Psychology). [Google Scholar]

- Aldaco R., Hoehn D., Laso J., Margallo M., Ruiz-salmón J., Cristobal J., Kahhat R., Vilanueva-Rey P., Bala A., Batlle-Bayer L., Fullana-i-Palmer P., Irabien A., Vazquez-rowe I. Food waste management during the COVID-19 outbreak: a holistic climate, economic and nutritional approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;742:140524. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annunziata A., Agovino M., Ferraro A., Mariani A. Household food waste: a case study in southern Italy. Sustainability. 2020;12(4):1495. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın A.E., Yildirim P. Understanding food waste behavior: the role of morals, habits and knowledge. J. Clean. Prod. 2020:124250. [Google Scholar]

- Baker D., Fear J., Denniss R. The Australia Institute; 2009. What a Waste: an Analysis of Household Expenditure on Food. Policy Brief No. 6.http://www.tai.org.au/sites/defualt/files/PB%206%20What%20a%20waste%20final_7.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg S., Möser G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: a new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007;27(1):14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Barr S. Factors influencing environmental attitudes and behaviours: a UK case study of household waste management. Environ. Behav. 2007;39(4):435–473. doi: 10.1177/0013916505283421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batlle-Bayer L., Aldaco R., Bala A., Puig R., Laso J., Margallo M., Vázquez-Rowe I., Antó J.M., Fullana-i-Palmer P. Environmental and nutritional impacts of dietary changes in Spain during the COVID-19 lockdown. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;748 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141410. Article 141410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Hassen T., El Bilali H., Allahyari M.S. Impact of COVID-19 on food behavior and consumption in Qatar. Sustainability. 2020;12:6973. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti S.H., Saleem F., Zakariya R., Ahmad A. The determinants of food waste behaviour in young consumers in a developing country. Br. Food J. 2019 doi: 10.1108/BFJ-06-2019-0450. Vol. and No. - ahead-of-print. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bio Intelligence Service . European Commission, Directorate C, Industry; 2010. Preparatory Study on Food Waste across EU 27. Paris, France.https://ec.europa.eu/environment/eussd/pdf/bio_foodwaste_report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Borsellino V., Kaliji S.A., Schimmenti E. COVID-19 drives consumer behaviour and agro-food markets towards healthier and more sustainable patterns. Sustainability. 2020;12(20):8366. [Google Scholar]

- Boulet M., Hoek A.C., Raven R. Towards a multi-level framework of household food waste and consumer behaviour: untangling spaghetti soup. Appetite. 2020;156:104856. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravi L., Francioni B., Murmura F., Savelli E. Factors affecting household food waste among young consumers and actions to prevent it. A comparison among UK, Spain and Italy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020;153:104586. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104586. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bravi L., Murmura F., Savelli E., Viganò E. Motivations and actions to prevent food waste among young Italian consumers. Sustainability. 2019;11(4):1110. doi: 10.3390/su11041110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brizi A., Biraglia A. “Do I have enough food?” How need for cognitive closure and gender impact stockpiling and food waste during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-national study in India and the United States of America. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2020;168:110396. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzby J.C., Hyman J. Total and per capita value of food loss in the United States. Food Pol. 2012;37(5):561–570. [Google Scholar]

- Canali M., Amani P., Aramyan L., Gheoldus M., Moates G., Östergren K., Kirsi Silvennoinen K., Waldron K., Vittuari M. Food waste drivers in Europe, from identification to possible interventions. Sustainability. 2016;9(1):1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Centrul Național de Evaluare și Promovare a Stării de Sănătate (Cnepss) Analiză de situație. 2019. https://insp.gov.ro/sites/cnepss/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Analiza-de-situatie-2019.pdf

- Chin W.W., Newsted P.R. Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research. 1999;1(1):307–341. [Google Scholar]

- Clark L.A., Watson D. Constructing validity: basic issues in objective scale development. Psychol. Assess. 1995;7(3):309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra T.K., Henseler J. Consistent and asymptotically normal PLS estimators for linear structural equations. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2015;81:10–23. [Google Scholar]

- Eroğlu H. Effects of Covid-19 outbreak on environment and renewable energy sector. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00837-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; Brussels: 2020. A Farm To Fork Strategy For a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System; Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament.https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/communication-annex-farm-fork-green-deal_en.pdf 20.5.2020. [Google Scholar]

- Evangelinos K.I., Jones N., Panoriou E.M. Challenges and opportunities for sustainability in regional universities: a case study in Mytilene, Greece. J. Clean. Prod. 2009;17:1154–1161. [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. Thrifty, green or frugal: reflections on sustainable consumption in a changing economic climate. Geoforum. 2011;42(5):550–557. [Google Scholar]

- Fao, Ifad, Wfp . FAO; Rome: 2014. The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2014. Strengthening the Enabling Environment for Food Security and Nutrition.http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4030e.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. Stanford University Press; 1957. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M., Ajzen I. Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA: 1975. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: an Introduction to Theory and Research. [Google Scholar]

- Fοx D., Ioannidi E., Sun Y.T., Jape V.W., Bawono W.R., Zhang S., Perez-Cueto F.J. Consumers with high education levels belonging to the millennial generation from Denmark, Greece, Indonesia and Taiwan differ in the level of knowledge on food waste. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science. 2018;11:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ganglbauer E., Fitzpatrick G., Comber R. Negotiating food waste: using a practice lens to inform design. ACM Trans. Comput. Hum. Interact. 2013;20(2):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ghinea C., Ghiuta O.-A. Household food waste generation: young consumers behaviour, habits and attitudes. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;16(5):2185–2200. doi: 10.1007/s13762-018-1853-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gjerris M., Gaiani S. Household food waste in Nordic countries: estimations and ethical implications. Etikk i praksis-Nordic Journal of Applied Ethics. 2013;(1):6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gold A.H., Malhotra A., Segars A.H. Knowledge management: an organizational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001;18(1):185–214. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Rowe E., Jessop D.C., Sparks P. Identifying motivations and barriers to minimising household food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014;84:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2013.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Rowe E., Jessop D.C., Sparks P. Predicting household food waste reduction using an extended theory of planned behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015;101:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger M.J., Aramyan L., Logatcheva K., Piras S., Righi S., Setti M., Vittuari M., Stewart G.B. The use of systems models to identify food waste drivers. Global food security. 2018;16:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Hult G.T.M., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. Sage Publications; 2016. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Sarstedt M., Hopkins L., Kuppelwieser V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): an emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014;26(2):106–121. [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Hult G.T.M., Ringle C., Sarstedt M. second ed. SAGE Publications; 2017. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) [Google Scholar]

- Hebrok M., Boks C. Household food waste: drivers and potential intervention points for design–An extensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017;151:380–392. [Google Scholar]

- Heidari A., Kolahi M., Behravesh N., Ghorbanyon M., Ehsanmansh F., Hashemolhosini N., Zanganeh F. Youth and sustainable waste management: a SEM approach and extended theory of planned behaviour. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2018;20(Part2) doi: 10.1007/s10163-018-0754-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in Variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2015;43:115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M. Are students really cautious about food waste? Korean students’ perception and understanding of food waste. Foods. 2020;9(4):410. doi: 10.3390/foods9040410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jribi S., Ben H., Doggui D., Debbabi H., et al. COVID-19 virus outbreak lockdown: what impacts on household food wastage? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020;22:3930–3955. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00740-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasavan S., Bin SharifAli S.S., Binti Masarudin S.A., Yusoff S.B. Quantification of food waste in school canteens: a mass flow analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021;156:105176. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana S., Haleem A., Luthra S., Huisingh D., Mannan B. Now is the time to press the reset button: helping India’s companiesto become more resilient and effective in overcoming the impacts of COVID-19, climate changes and other crises. J. Clean. Prod. 2021;280:124466. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T., Freedman M.R. Students reduce plate waste through education and trayless dining in an all-you-can-eat college dining facility. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 2010;110(9) A68. Suppl 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kline R.B. Guilford Press; New York: 2011. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. [Google Scholar]

- Knezevic B., Kurnoga N., Anic I.D. Typology of university students regarding attitudes towards food waste. Br. Food J. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- Koivupuro H.K., Hartikainen H., Silvennoinen K., Katajajuuri J.M., Heikintalo N., Reinikainen A., Jalkanen L. Influence of socio-demographical, behavioural and attitudinal factors on the amount of avoidable food waste generated in Finnish households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012;36(No. 2):183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Laborde D., Martin W., Swinnen J., Vos R. COVID-19 risks to global food security. Science. 2020;369(6503):500–502. doi: 10.1126/science.abc4765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langerak F., Hultink E.J., Robben H. The impact of market orientation, product advantage, and launch proficiency on new product performance and organizational performance. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2004;21(2):79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtokunnas T., Mattila M., Närvänen E., Mesiranta N. Towards a circular economy in food consumption: food waste reduction practices as ethical work. J. Consum. Cult. 2020 1469540520926252. [Google Scholar]

- Lusk J.L., Ellison B. Economics of household food waste. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue canadienne d’agroeconomie. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Lyndhurst B. WRAP; UK: 2007. Food Behaviour Consumer Research - Findings from the Quantitative Survey. Briefing Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Maki A., Rothman A.J. Understanding pro-environmental intentions and behaviors: the importance of considering both the behavior setting and the type of behavior. J. Soc. Psychol. 2017;157(5):517–531. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2016.1215968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles A. If we get food right, we get everything right: rethinking the food system in post-COVID-19 Hawai’i. 2020. http://hdl.handle.net/10790/5248

- Mondéjar-Jiménez J.A., Ferrari G., Secondi L., Principato L. From the table to waste: an exploratory study on behaviour towards food waste of Spanish and Italian youths. J. Clean. Prod. 2016;138:8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nicola M., Alsafi Z., Sohrabi C., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A., Iosifidis C., et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus and COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Int. J. Surg. 2020;78:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaus J.C., Nickols-Richardson M.S., Ellison B. Wasted food: a qualitative study of U.S. young adults’ perceptions, beliefs and behaviors. Appetite. 2018;130(1):70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt J.P., Barthel M., Macnaughton S. Food waste within food supply chains: quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society Biological Sciences. 2010;365:3065–3081. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto R.S., Santos Pinto R.M., Melo F.F.S., Campos S.S., Cordovil C.M. A simple awareness campaign to promote food waste reduction in a University canteen. Waste Manag. 2018;76:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2018.02.044. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porpino G., Wansink B., Parente J. Wasted positive intentions: the role of affection and abundance on household food waste. J. Food Prod. Market. 2016;22(7):733–751. [Google Scholar]

- Pourdehnad J., Starr L.M., Koerwer V.S., McCloskey H. Disruptive effects of the coronavirus–errors of commission and of omission? 2020. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=jscpscp

- Priefer C., Jörissen J., Bräutigam K.R. Food waste prevention in Europe–A cause-driven approach to identify the most relevant leverage points for action. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016;109:155–165. [Google Scholar]