Abstract

Introduction

Health Sector Development Plans (HSDPs) aim to accelerate movement towards achieving sustainable development goals for health, reducing inequalities, and ending poverty. Reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health (RMNCH) services are vulnerable to economic imbalances, including health insecurity, unmet need for healthcare, and low health expenditure. The same vulnerability influences the potential of a country to combat global outbreaks such as the COVID-19. We aimed to provide some important insights into the impacts of COVID-19 on RMNCH indicators and outcomes of the HSDP in Uganda.

Methods

We conducted a descriptive study of secondary data obtained from the Ugandan government-led portals, supplemented by analyses of relevant articles published up to 06 May 2021 and deposited in PubMed.

Results

Through synthesizing actionable and relevant evidence, we realized that RMNCH in Uganda is highly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown measures. The impact was across immunization, antenatal, sexual and reproductive health, emergency and obstetric, and postnatal care services. There was a decline sharply by 9.6% for under-five vitamin A coverage, 9% for DPT3HibHeb3 coverage, 6.8% for measles vaccination coverage, 6% for isoniazid preventive therapy coverage, and 3% for facility-based deliveries. Maternal and under-five deaths increased by 7.6% and 4%, respectively. Outreaches were rarely conducted in the lockdown period.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a multitude of questions regarding the optimal policies to mitigate the disease while minimizing the unintended detrimental consequences of RMNCH. The lockdown restrictions threatened to reverse the progress made on the national HSDP for RMNCH. In Uganda, where young women are vulnerable to early marriage, unintended pregnancies, and unsafe abortion, access to RMNCH services should continue regardless of the COVID-19 status in the country. We urge that Uganda and other African countries should build resilient and sustainable health systems that can withstand emerging diseases like the COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health, Health Sector Development Plan, Africa, Uganda

Background

Health Sector Development Plans (HSDPs) aim to accelerate movement towards achieving sustainable development goals for health, reducing inequalities, and ending poverty. Many countries in Africa have set ambitious HSDPs to improve equitable access to health services and strengthen health systems in line with their national health policy and overall country strategy.1–4 Reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health (RMNCH) services have been one of their top priorities.5–11 RMNCH services are vulnerable to economic imbalances, including health insecurity, unmet need for healthcare, and low health expenditure.12–14 The same vulnerability influences the potential of a country to combat global outbreaks such as the COVID-19. There were global concerns that COVID-19 would severely disrupt the healthcare system and threaten the already overburdened healthcare system, particularly in countries with limited resources.15–17 The Ebola outbreak was declared a public health emergency of international concern as it might result in an unprecedented outbreak, and the lessons learned from the Ebola outbreaks were crucial to developing the COVID-19 responses in Africa.18,19

In Uganda, a nationwide lockdown due to COVID-19 entailed closing down the normal running of the business and was declared between 25 March and 30 June 2020,20 as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic and concern of the spread of cases. The lockdown closed all international borders and restricted population movement, interrupting activities of hospitals, public transport, businesses, and other public gatherings.20,21 The lockdown restrictions have been progressively eased since 04 May 2020.

The COVID-19 lockdown in Uganda had severe impacts on the life of the people; it evoked food insecurity among underprivileged households and older people,22,23 scaled-down patient care services,24,25 and increased child abuse.26 Some of the preventive measures such as travel restrictions, self-isolation and social distances are modifying health-seeking behaviors and undermining the delivery of health services in the required manner.22

Studies reported that RMNCH and related HSDP indicators were challenged in Africa during the COVID-19. In Kenya, home deliveries27 and sexual violence against adult and child survivors28 increased during the COVID-19 time, signifying the need for targeted measures to alleviate the issue.28 In Rwanda, the pandemic significantly affected the access to and utilization of MCH services.29 In Ethiopia, the pandemic affected RMNCH services and maternal and perinatal outcomes30 and increased unintended pregnancy.31

The vulnerability of women and children in Uganda due to the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated containment measures has so far been understated in the literature and policy makings. Such weak attention may erode the efforts that the Ugandan government has made in the last two decades to improve RMNCH services in the country.

Thus, we aimed to provide some important insights into the impacts of COVID-19 on RMNCH indicators and outcomes of the HSDP in Uganda.

Methods

We conducted a descriptive study of secondary data obtained from the Ugandan government-led portals, supplemented by analyses of relevant articles published up to May 2021 and deposited in PubMed. The data from the Ugandan government-led portals included the Uganda Ministry of Health annual health sector performance report for the financial year 2019/20.8 For the review, a search was conducted using the keywords (Uganda) AND (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR “Severe acute respiratory syndrome 2”). Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and Title/Abstract terms were searched. The search was limited to full-text articles published in English, and the articles were selected based on the title, appropriate abstract, and then full-text by two reviewers (MGA, TM) independently. There were no restrictions on the study design but only studies carried out in Uganda. The reference lists of the selected studies were checked further to retrieve relevant publications that were not found with the initial search.

Results

The study selection strategy is summarized in Figure 1, and characteristics of the included publications are provided in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram outlining the search process.

Table 1.

Summary of Articles Reviewed

| SN | Author/Year | Title | Sample Size | Eligibility | Study Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bar-Zeev et al: August 19, 2020 | UNFPA; Supporting midwives at Heart of COVID-19 Response, Documentary | NA | NA | As of this writing, Uganda reported no COVID-19 Death, 7 deaths related to childbirth were reported |

| 2 | Mambo et al 2020 | Factors that Influence Access and Utilization of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services among Ugandan Youths during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: An online Cross-sectional survey | 724 | NA | Access to SRH information and Services for Ugandan Youths was restricted |

| 3 | Uganda MOH | Annual Sector Performance Report 2019–2020 | NA | NA | Decrease in output of MOH indicators |

The Burden of COVID-19 in Uganda

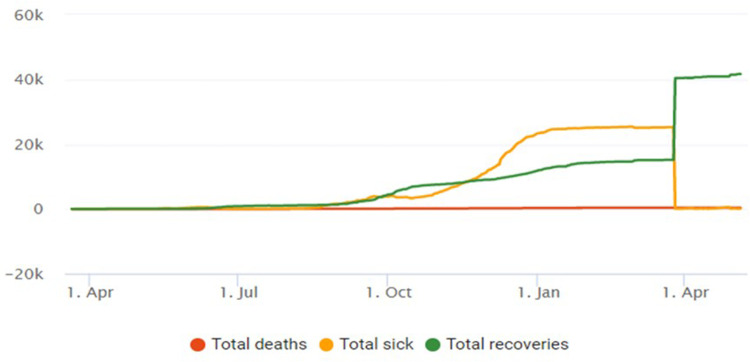

In Uganda, as of 06 May 2021, a total of 42,102 people have been diagnosed with COVID-19, with 0.25% sick, 98.93% recovered, and 0.81% died.33 There has been an increasing trend of the disease over time but remain consistent in recent times (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

COVID-19 statistics of Uganda, 06 May 2021.33

Impact on Immunization

The immunization program in Uganda was affected by the COVID pandemic (Table 2). According to the Uganda Ministry of Health’s annual health sector performance report for the fiscal year 2019/20 (July 2019–June 2020),32 under-five vitamin A coverage for the year was 21.4%; a decline by 9.6% from 30% in 2018/19. The report for both was far below the HSDP target of 66%.

Table 2.

Uganda RMNCH-Related Performance Trend and Comparison Against HSDP Targets

| Indicator | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 | HSDP Target | %Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPT2 doses coverage for pregnant women | 55% | 54.4% | 63.2% | 66% | 60% | 93% | −9.0% |

| Under-five vitamin A second dose coverage | 28% | 25.3% | 35.3% | 30% | 21.4% | 66% | −2.9% |

| Health facility deliveries | 55% | 58.1% | 60% | 63% | 59% | 89% | −6.3% |

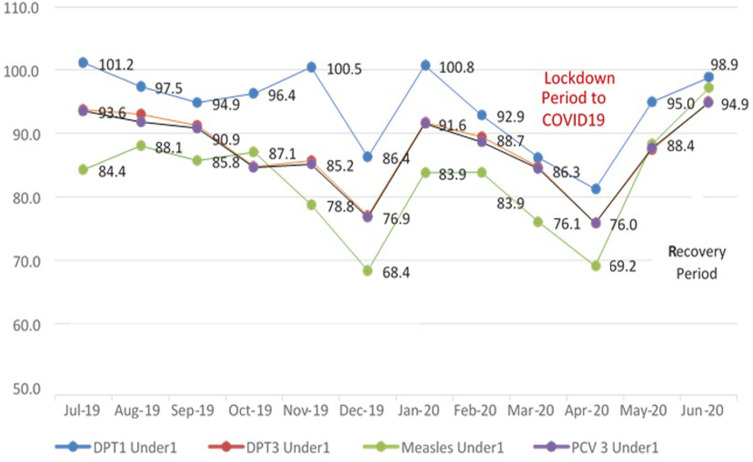

Comparing the RMNCH-related performance against the Ugandan HSDP targets, there were significant declines in the monthly trends of key performance indicators, including delivery in healthcare facilities (Figure 3). The DPT3HibHeb3 coverage declined by 9%, from 96% in 2018/19 to 87% in 2019/20, drawing back the achieved HSDP target of 95%. Measles coverage declined by 6.8%, from 88% to 82%.

Figure 3.

Uganda monthly trends in immunization coverage for the Financial year 2019/2020.

Abbreviations: DPT1, First dose of diphtheria–pertussis–tetanus toxoid combination vaccine; DPT3, Third dose of diphtheria–pertussis–tetanus toxoid combination vaccine; PCV3, Third dose pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

Impact on Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights

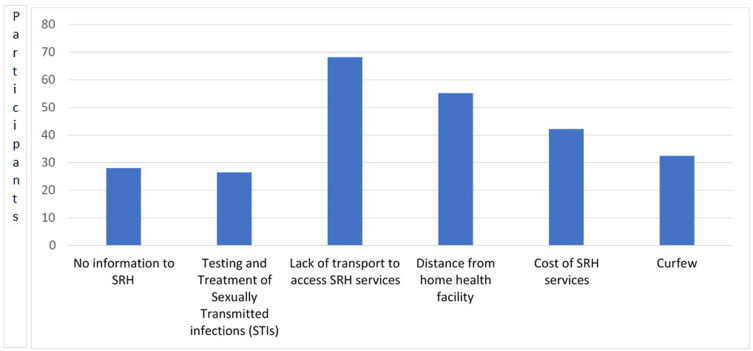

Lack of transport to healthcare facilities and distance from home to health facility were the major factors to access sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services in the COVID-19 lockdown period (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Factors limiting access to SRHR during the lockdown.

Abbreviations: SRH, Sexual and reproductive health; STI, Sexually transmitted diseases.

Failure to access the SRH services led 40.4% of the study participants in Uganda to contract sexually transmitted diseases, 32.2% unwanted pregnancies with 17.7% pregnancy complications, and 17.7% carried out unsafe abortions. Sexual abuses were noted to be at 32.2%, while 13.2% of the participants needed access to antiretroviral drugs.

Impact on Antenatal Care

Facility-based deliveries were affected by the pandemic and its containment measures, declining from 62% to 59% in the two financial years, and yet far below the HSDP target of 87%.8 Isoniazid preventive therapy coverage for pregnant women has also declined to 60% from 66% in 2018/19. Under-five deaths also increased by 4% in the COVID-19 outbreak, from 23 to 24 per 1000 admissions. It was yet unable to achieve the HSDP target of 16 per 1000.

Impact on Emergency, Obstetric and Postnatal Care

\The number of maternal deaths in the COVID-19 pandemic (2019/20) increased by 7.6%, from 92 to 99 per 100,000 when compared with 2018/19. Both years were falling short of the HSDP target of 98/100,000. The Health Management Information System (HMIS) data recorded 1192 maternal deaths, which is again higher than the 1083 recorded in the preceding pre-COVID-19 year.

Discussion

RMNCH in Uganda is highly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and its containment measures. There was a significant decline in immunization services from March to May 2020 where Uganda was on lockdown, and the impact was across all immunization services, including the First dose of Diphtheria and tetanus toxoid with the pertussis-containing vaccine (DPT1), Third dose of Diphtheria and tetanus toxoid with the pertussis-containing vaccine (DPT3), Measles, and Third dose pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV3).

A recent risk–benefit analysis study warned that the deaths prevented by sustaining routine childhood immunization in Africa outweigh the excess risk of COVID-19 deaths associated with vaccination clinic visits in Africa,10 which Uganda needs to step in. The greater risk was that there was a 3% decline in the public health sector staffing level, from 76% in the pre-COVID-19 period, and this reverted the efforts made to meet the HSDP target of 80%. The percentage of health facilities having over 95% availability of a basket of commodities also declined by 7%, from 53% in the pre-COVID-19 year to 46%, and yet was far below the HSDP target of 75%. This is in agreement with a study conducted in low- and middle-income countries (Bangladesh, Nigeria and South Africa) that reported a reduction in utilization of essential MNCH amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.34

Though the Government of Uganda put in place public health emergency directives, access to essential sexual and reproductive health services such as contraceptives, condoms, menstrual health materials, and HIV testing had little attention.23,35 Ugandan women and girls were reported to have had less access to protective services in case of intimate need of a partner, and their lower level of education made them more vulnerable to identify and use alternative options. This highlights the strong need for maintaining essential resources and staff for sexual and reproductive health services. In Uganda, young women are vulnerable to early marriage, unintended pregnancies, and unsafe abortion, and pandemics like COVID-19 escalate the vulnerability.36 For reduction in maternal mortality as well as poverty and empowering women, SRH services are crucial to prevent unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortion. Harnessing knowledge and awareness about sexual and reproductive health through ongoing and sustainable platforms is important to ensure young women to cope with such unforeseen disease conditions.

The Ugandan government has encouraged labouring women to reach local community leaders to have access to ambulances to take to the nearby healthcare facility. However, a recent article reported that ambulances have not been readily available, and as a result, women are forced to visit traditional birth attendants.37 Current literature conducted in Uganda supports remote appointments if a face-to-face consultation is deemed unnecessary after a careful review of their needs through telephone consultation.38 Sustainable platforms are important to ensure young women can cope with such unforeseen disease conditions. One possibility has been the use of digital health to support the management of COVID-19. Some countries have integrated digital health solutions used in multiple approaches for COVID-19 containment and knowledge-sharing measures and found promising results.39–43

Postnatal is limited to neonatal care and the importance of not separating mothers and infants if COVID-19 infections are suspected and support for continuous breastfeeding. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) has released a technical brief for postnatal care during COVID-19 with the goal that all pregnant women, including those with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infections, have the right to high-quality care before, during and after childbirth.44 How local governments in Uganda can put such important policies and strategies into action remain a major concern as these need fertile ground, including health safety-assured infrastructure and human resource capacity.

The findings of this study provide important insights into the indirect impacts of the COVID-19 lockdown restrictions on RMNCH services. However, more primary studies with rigorous multivariate analyses that can account for potential confounders are needed to imply very strong causation between observed results and the lockdown.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a multitude of questions regarding the optimal policies to mitigate the disease while minimizing the unintended detrimental consequences of RMNCH. There was a reversal of priorities to COVID-19 in Uganda, and this had affected the accessibility of RMNCH services that threatened to reverse the progress made to meet national HSDP targets. In Uganda, where young women are vulnerable to early marriage, unintended pregnancies, and unsafe abortion, given the likelihood of periodic waves of the pandemic globally, COVID-19 extenuation plans therefore be integrated with the standard of care provision to enhance systems pliability to deal with all health needs, and access to RMNCH services should continue regardless of the COVID-19 status in the country. We urge the Government of Uganda should build resilient and sustainable health systems that can withstand future health challenges and pressures like the COVID-19. While a few studies have been conducted, early evidence from this perspective review indicates an indirect impact of the COVID-19 crisis on RMNCH care is evident. Rigorous epidemiological studies must document the health impact of COVID-19 infection on pregnancy and unborn babies.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to the Center for Innovative Drug Development and Therapeutic Trials for Africa (CDT-Africa), College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, for supporting this work.

Funding Statement

There was no specific funding for the study.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declared no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sobtafo Nguefack CR. Effectiveness of official development assistance in the health sector in Africa: a case study of Uganda. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2021;41(3):231–240. doi: 10.1177/0272684X20918045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lakew S, Ankala A, Jemal F. Determinants of client satisfaction to skilled antenatal care services at southwest of Ethiopia: a cross-sectional facility based survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):479. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2121-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manyazewal T, Matlakala MC. Implementing health care reform: implications for performance of public hospitals in central Ethiopia. J Glob Health. 2018;8(1):010403. doi: 10.7189/jogh.08.010403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ludwick T, Endrias M, Morgan A, Kane S, McPake B. Moving from community-based to health-centre based management: impact on urban community health worker performance in Ethiopia. Health Policy Plan. 2021;czab112. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czab112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Posso A, De Silva Perera U, Mishra A. Community-level health programs and child labor: evidence from Ethiopia. Health Econ. 2021. doi: 10.1002/hec.4429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agiraembabazi G, Ogwal J, Tashobya C, Kananura RM, Boerma T, Waiswa P. Can routine health facility data be used to monitor subnational coverage of maternal, newborn and child health services in Uganda? BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):512. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06554-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mwanga-Amumpaire J, Kalyango JN, Källander K, et al. A qualitative study of the perspectives of health workers and policy makers on external support provided to low-level private health facilities in a Ugandan rural district, in management of childhood infections. Glob Health Action. 2021;14(1):1961398. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2021.1961398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matovelo D, Ndaki P, Yohani V, et al. Why don’t illiterate women in rural, Northern Tanzania, access maternal healthcare? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):452. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03906-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minnis AM, Krogstad E, Shapley-Quinn MK, et al. Giving voice to the end-user: input on multipurpose prevention technologies from the perspectives of young women in Kenya and South Africa. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2021;29(1):1927477. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2021.1927477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bain LE, Ahinkorah BO, Seidu AA, Budu E, Okyere J, Kongnyuy E. Beyond counting intended pregnancies among young women to understanding their associated factors in sub-Saharan Africa. Int Health. 2021;ihab056. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihab056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahinkorah BO, Budu E, Aboagye RG, et al. Factors associated with modern contraceptive use among women with no fertility intention in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from cross-sectional surveys of 29 countries. Contracept Reprod Med. 2021;6(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s40834-021-00165-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Majid F. Moving beyond standard RMNCH coverage indicators. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(9):e1210. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00305-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malembaka EB, Altare C, Bigirinama RN, et al. The use of health facility data to assess the effects of armed conflicts on maternal and child health: experience from the Kivu, DR Congo. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):195. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06143-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tigabu S, Demelew T, Seid A, Sime B, Manyazewal T. Socioeconomic and religious differentials in contraceptive uptake in western Ethiopia: a mixed-methods phenomenological study. BMC Women’s Health. 2018;18(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0580-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odey GO, Alawad AGA, Atieno OS, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: impacts on the achievements of sustainable development goals in Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;38:251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manyazewal T, Woldeamanuel Y, Blumberg HM, Fekadu A, Marconi VC. The fight to end tuberculosis must not be forgotten in the COVID-19 outbreak. Nat Med. 2020;26(6):811–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuja KH, Aqeel M, Jaffar A, Ahmed A. COVID-19 pandemic and impending global mental health implications. Psychiatr Danub. 2020;32(1):32–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan FMA, Hasan MM, Kazmi Z, et al. Ebola and COVID-19 in Democratic Republic of Congo: grappling with two plagues at once. Trop Med Health. 2021;49(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s41182-021-00356-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Impouma B, Williams GS, Moussana F, et al. The first eight months of COVID-19 pandemic in three West African countries: leveraging lessons learned from responses to the 2014-2016 Ebola virus disease outbreak. Epidemiol Infect. 2021;1-22. doi: 10.1017/S0950268821002053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz JI, Muddu M, Kimera I, et al. Impact of a COVID-19 national lockdown on integrated care for hypertension and HIV. Glob Heart. 2021;16(1):9. doi: 10.5334/gh.928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitara DL, Ikoona EN. COVID-19 pandemic, Uganda’s story. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35(Suppl 2):51. doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.23433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nathan I, Benon M. COVID-19 relief food distribution: impact and lessons for Uganda. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35(Suppl 2):142. doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.142.24214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawala BA, Kirui BK, Cumber SN. Why policy action should focus on the vulnerable commercial sex workers in Uganda during COVID-19 fight. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35(Suppl 2):102. doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.24664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanji RR, Arunga S. Changing ophthalmic practice during the COVID-19 pandemic in Uganda. Community Eye Health. 2020;33(109):42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abila DB, Ainembabazi P, Wabinga H. COVID-19 pandemic and the widening gap to access cancer services in Uganda. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35(Suppl 2):140. doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.140.25029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sserwanja Q, Kawuki J, Kim JH. Increased child abuse in Uganda amidst COVID-19 pandemic. J Paediatr Child Health. 2021;57(2):188–191. doi: 10.1111/jpc.15289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lusambili AM, Martini M, Abdirahman F, et al. “We have a lot of home deliveries” A qualitative study on the impact of COVID-19 on access to and utilization of reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health care among refugee women in urban Eastleigh, Kenya. J Migr Health. 2020;1-2:100025. doi: 10.1016/j.jmh.2020.100025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rockowitz S, Stevens LM, Rockey JC, et al. Patterns of sexual violence against adults and children during the COVID-19 pandemic in Kenya: a prospective cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e048636. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-048636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wanyana D, Wong R, Hakizimana D. Rapid assessment on the utilization of maternal and child health services during COVID-19 in Rwanda. Public Health Action. 2021;11(1):12–21. doi: 10.5588/pha.20.0057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kassie A, Wale A, Yismaw W. Impact of Coronavirus Diseases-2019 (COVID-19) on utilization and outcome of reproductive, maternal, and newborn health services at governmental health facilities in South West Ethiopia, 2020: comparative cross-sectional study. Int J Womens Health. 2021;13:479–488. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S309096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunie Asratie M. Unintended pregnancy during COVID-19 pandemic among women attending antenatal care in Northwest Ethiopia: magnitude and associated factors. Int J Womens Health. 2021;13:461–466. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S304540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Republic of Uganda Ministry of Health. Annual Health Sector Performance Report, Financial Year 2019/20. Kampala, Uganda: Ministry of Health; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corona Scanner. Realtime coronavirus statistics, Uganda. Available from: https://corona-scanner.com/country/uganda. Accessed October 9, 2021.

- 34.Ahmed T, Rahman AE, Amole TG, et al. The effect of COVID-19 on maternal newborn and child health (MNCH) services in Bangladesh, Nigeria and South Africa: call for a contextualised pandemic response in LMICs. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01414-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ponticiello M, Mwanga-Amumpaire J, Tushemereirwe P, Nuwagaba G, King R, Sundararajan R. “Everything is a mess”: how COVID-19 is impacting engagement with HIV testing services in rural Southwestern Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(11):3006–3009. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02935-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ariho P, Kabagenyi A. Age at first marriage, age at first sex, family size preferences, contraception and change in fertility among women in Uganda: analysis of the 2006-2016 period. BMC Women's Health. 2020;20(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12905-020-0881-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pallangyo E, Nakate MG, Maina R, Fleming V. The impact of covid-19 on midwives’ practice in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania: a reflective account. Midwifery. 2020;89:102775. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2020.102775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamulegeya LH, Bwanika JM, Musinguzi D, Bakibinga P. Continuity of health service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of digital health technologies in Uganda. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35(Suppl 2):43. doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.23115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El Otmani Dehbi Z, Sedrati H, Chaqsare S, et al. Moroccan digital health response to the COVID-19 crisis. Front Public Health. 2021;9:690462. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.690462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.NeJhaddadgar N, Ziapour A, Zakkipour G, Abbas J, Abolfathi M, Shabani M. Effectiveness of telephone-based screening and triage during COVID-19 outbreak in the promoted primary healthcare system: a case study in Ardabil Province, Iran. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2020;1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10389-020-01407-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manyazewal T, Woldeamanuel Y, Blumberg HM, Fekadu A, Marconi VC. The potential use of digital health technologies in the African context: a systematic review of evidence from Ethiopia. NPJ Digit Med. 2021;4(1):125. doi: 10.1038/s41746-021-00487-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tilahun B, Gashu KD, Mekonnen ZA, Endehabtu BF, Angaw DA. Mapping the role of digital health technologies in prevention and control of COVID-19 pandemic: review of the literature. Yearb Med Inform. 2021;30(1):26–37. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1726505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niakan R, Kalhori S, Bahaadinbeigy K, et al. Digital health solutions to control the COVID-19 pandemic in countries with high disease prevalence: literature review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(3):e19473. doi: 10.2196/19473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.UNFPA. COVID-19 Technical Brief for Postnatal Care Services. New York, USA: UNFPA; 2020. Available from: https://asiapacific.unfpa.org/en/publications/covid-19-technical-brief-postnatal-care-services. Accessed October 9, 2021. [Google Scholar]