Abstract

Progranulin (PGRN) is a key regulator of lysosomes and its deficiency has been linked to various lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs), including Gaucher disease (GD), one of the most common LSD. Here, we report that PGRN plays a previously unrecognized role in autophagy within the context of GD. PGRN deficiency is associated with the accumulation of LC3-II and p62 in autophagosomes of GD animal model and patient fibroblasts, resulting from the impaired fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes. PGRN physically interacted with Rab2, a critical molecule in autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Additionally, a fragment of PGRN containing the Grn E domain was required and sufficient for binding to Rab2. Further, this fragment significantly ameliorated PGRN-deficiency associated impairment of autophagosome-lysosome fusion and autophagic flux. These findings not only demonstrate that PGRN is a crucial mediator of autophagosome-lysosome fusion but also provide new evidence indicating PGRN’s candidacy as a molecular target for modulating autophagy in GD and other LSDs in general.

Keywords: Autophagosome-lysosome fusion, Gaucher disease, Progranulin, autophagy, Rab2

Introduction

The autophagy-lysosomal system is responsible for catabolic, degradative processing of unwanted materials and is crucial to the maintenance of cellular and tissue homeostasis. Autophagy-lysosomal processing occurs in several stages; the successful progression through these stages depends on the integrated function of lysosomes and autophagosomes [1]. Therefore, it is not unexpected that autophagic dysfunction is a prominent feature of several lysosomal storage disorders [2–4]. Gaucher disease (GD), one of the most common genetic lysosomal storage diseases (LSD), is caused by mutations in the GBA1 gene encoding β-glucocerebrosidase (GCase or GBA1), which consequently lead to the accumulation of β-glucosylceramide (β-GlcCer) in macrophages and other cell types [5–7]. Accumulation of β-GlcCer leads to lysosomal dysfunction and subsequent defects in autophagy [3, 8]. Several studies have reported observations of autophagy-lysosomal system impairment in the neuronopathic GD mouse model [3, 9]. Moreover, GBA1 mutations can also trigger mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy defects [10, 11].

Progranulin (PGRN) is a widely expressed glycoprotein linked to a variety of physiologic and disease processes, including early embryogenesis, wound healing, host defense, autoimmune disease, and cancer [12–18]. PGRN exerts its pleiotropic functionality through multiple mechanisms. As a neurotrophic factor, mutations in GRN gene associate with some neuropathic diseases, such as frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL) [19–23]. PGRN also imparts anti-inflammatory effects in various conditions through targeting TNF receptors [24–27]. Recent reports further reveal an emergent link between PGRN and autophagy, however, the exact mechanism of how PGRN regulates the autophagic pathway is unclear and controversial. PGRN deficient neurons display reduced autophagic flux and enhanced accumulation of pathological forms of TDP-43 [28]. In murine models, PGRN treatment may contribute to adipose insulin resistance via increased autophagy or autophagic imbalance [29, 30], whereas some other reports indicate a controversial effect of PGRN with a reduction in hepatic insulin signaling and autophagy [31].

Recent studies from several laboratories, including ours, have revealed associations between PGRN deficiency and lysosomal storage diseases, such as GD and Tay-Sachs disease [32, 33]. Jian et al. reported that PGRN was a co-chaperone for lysosomal localization of GCase through linking GCase to heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) [14]. Given that impairment of the autophagy pathway is a feature of GD pathology and PGRN is a novel important regulator of autophagosomes [9, 10, 28, 34], we set out to investigate the role of PGRN in autophagy, particularly in PGRN deficiency associated GD. In this study, we found that PGRN interacted with Rab2, and its deficiency impaired the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes. More importantly, an approximately 15-kDa PGRN-derived protein, ND7, which was responsible for binding to Rab2, could effectively ameliorate the impaired autophagosome-lysosome fusion.

Materials and methods

Reagents and materials

WT fibroblasts and type 2 GD patients’ L444P fibroblasts were purchased from Coriell Cell Repositories (Camden, NJ). Antibodies against ATG5 (sc-133158), p62/SQSTM1 (sc-28359), His-tag (sc-57598), GFP (sc-9996), and GAPDH (sc-25778) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Texas, USA). Antibody against PCDGF (40–3400) was purchased from Invitrogen (Waltham, MA, USA). Antibodies against LC3B (2775S) and LAMP1 (9091) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibodies against Rab2 (ab154729) and Bcl2-L13 (ab25895) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Fluorescence labeled secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. (West Grove, PA, USA). 4-Methylumbelliferyl β-D-glucopyranoside (4-MUG, M3633) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Natick, MA, USA). LysoTracker Red DND99 (L7528), HisPur™ Ni-NTA Resin (88221), and Pierce High-Capacity Endotoxin Removal Resin (2162373.3), Hign Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (01096151), SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (2103610), and LysoSensor™ Yellow/Blue DND-160 (L7545), were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Bridgewater, NJ, USA). DAPI (H-1200) was purchased from VECTOR Laboratories (Burlingame, CA, USA). The plasmid FUW mCherry-GFP-LC3 (110060) was purchased from Addgene (Watertown, MA, USA). Recombinant His-tag PGRN protein was purified from HEK293T stable cell lines as described previously [14]. Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; 11965–118) and fetal bovine serum (FBS; 16000–044) were purchased from Gibco-BRL (Waltham, MA, USA). Progranulin (human) ELISA Kit (AG-45A-0018YEK-KI01) was purchased from AdipoGen Life Sciences (San Diego, CA, USA). Bafilomycin A1 (1334/100U) was purchased from Tocris (UK).

PGRN deficient GD model

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of New York University School of Medicine. Mice were group-housed within the rodent barrier facility at the Skirball Institute of Biomolecular Medicine with ad libitum access to food and water in a specific pathogen-free room under controlled temperature and humidity on a 12 hour light/dark cycle. C57BL6/J background wild-type (WT) and PGRN KO mice were acquired from Jackson Laboratory and maintained within the animal housing facility. 8 week-old mice were induced with chronic lung inflammation by intraperitoneal (I.P.) injection of Ovalbumin (OVA)-Alum at Day 1 and Day 15, followed by intranasal challenge with 1% OVA, beginning at Day 29 and administered at a frequency of every three days for four weeks. In PGRN and ND7 rescue experiments, the frequency of intranasal challenge with OVA was increased to three times a week, recombinant PGRN or ND7 were I.P. injected at 4 mg/kg body weight per week starting from the first week of the intranasal challenge until to the end of this experiment and another group of mice were treated with PBS as a negative control. The mice were sacrificed and the tissues of interest were collected.

Cell culture

WT fibroblasts, GD patient L444P fibroblasts, HEK293T, and C28i2 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

Generation knockout cell lines for PGRN or Rab2

CRISPR-Cas9 technology was used to delete PGRN or Rab2 genes. The sgRNA that targets human PGRN or Rab2 genomic sequence was subcloned into the lentiCRISPR lentiviral plasmid (Addgene, 49535; deposited by Dr. Feng Zhang) following the manufacturer’s instruction. For the preparation of lentivirus, human PGRN sgRNA or Rab2 sgRNA subcloned lentiCRISPR plasmids were cotransfected with lentiviral packaging plasmids (psPAX2 and pMD2.G plasmid) into the HEK293T cells, respectively. 48 h post-transfection, supernatants containing indicated lentivirus particles were harvested. L444P fibroblasts were infected with the indicated lentivirus and selected with 1 μg/ml of puromycin for 5–7 days. The PGRN or Rab2 knockout efficiency in these selected cells was analyzed by western blotting.

Western blotting

Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE. The samples were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane after gel electrophoresis. Nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1hr and the membrane was probed with the primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The membrane was washed with TBST before incubation with the secondary antibody for 2 hrs at room temperature and repeated washing. The bands were developed using ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (Amersham Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Preparation of lipid extraction

Mouse brain tissues were used as a source of lipid mixture. Briefly, one mouse brain was dissected under sterile conditions. The brain tissues were homogenized in 50 ml PBS. The bicinchoninic acid assay was used to determine the protein level in the brain lysates.

LysoTracker assay

Type 2 GD L444P patient fibroblasts were cultured on black wall-clear bottom 96-well microplates or coverslips in 24-well plates and challenged with lipid lysate (50 μg/ml) for 24 hrs. The next day, a fresh medium containing 300 nM LysoTracker® Red was added for 1 h. After washing with PBS, the fluorescence intensity was read by SpectraMax i3x plate reader at 647/668 nm excitation/emission, alternatively live images were taken by fluorescence microscopy.

GCase activity measurement

For testing the effect of PGRN knockout on GCase (β-glucocerebrosidase/GBA) activity, fluorescent substrate: 4-MUG was used to determine GCase activity in cell lysate. Briefly, 20 μg cell lysate from WT, L444P, or L444P/PGRN KO fibroblasts were incubated with 4-MUG in 0.1 M citrate buffer (0.8% w/v sodium taurocholate, pH 5.2) for 1 hour at 37°C. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of released 4-methylumbelliferone, indicative of GCase activity, was measured with SpectraMax i3x plate reader at 340nm/460nm excitation/emission.

pH measurement of lysosomes

The lysosomal pH was measured as described using the dye LysoSensor Yellow/Blue DND-160 [35]. Briefly, when cells reached 90% confluence, media was removed and replenished with fresh growth media containing a 2μM LysoSensor Yellow/Blue DND-160 working solution. After a 2hr incubation, medium containing dye was removed and replaced with fresh growth medium. Fluorescence was observed using fluorescence microscopy with 329/440 nm excitation/emission (green) and 384/540 nm excitation/emission (red). The lysosomal pH was determined by the ratio of green and red fluorescence readings.

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscope

Frozen lung sections, cover-slip cultured L444P/PGRN KO, or PGRN KO C28i2, were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 5 min and washed with PBS twice. The cells were permeabilized by 0.1% TritonX-100 PBS for 5 min and washed with PBS. The tissues were blocked with 1:50 dilution of normal donkey serum for 30 min. Primary antibodies were probed on the slides at 4°C overnight. The next day, slides were washed with PBS, indicated fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies were added for 1 hour and followed by a wash with PBS. The tissues or cells were mounted on an anti-fade medium containing DAPI. The images were taken by Leica TCS SP5 confocal system.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted by RNeasy plus mini kit and cDNA was synthesized using Hign Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcriptase. SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix was used to perform quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) on a StepOnePlusTM real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The mRNA expression level of the target gene was calculated by ΔΔCT and fold changes of mRNA levels were normalized to GAPDH. The following primer sequences were used for the qRT-PCR: LC3 forward: 5’-TTCGAGAGCAGCATCCAACC-3’, reverse: 5’-GATTGGTGTGGAGACGCTGA-3’; p62 forward: 5’-CATCGGAGGATCCGAGTGTG-3’, reverse: 5’-TTCTTTTCCCTCCGTGCTCC-3’; ATG12 forward: 5’-GCGAACACGAACCATCCAAG-3’, reverse: 5’-CACGCCTGAGACTTGCAGTA-3’.

Construction of expression plasmids

cDNAs encoding either full-length human PGRN or its serial N-terminal or Grn E deletion mutant ΔND7 were cloned into pEGFP-N1 vectors by using EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites. The amino acid number encoded by N-terminal Deletions (ND) constructs: full-length PGRN (aa 1–593), ND1 (aa 45–593), ND2 (aa 113–593), ND3 (aa 179–593), ND4 (aa 261–593), ND5 (aa 336–593), ND6 (aa 416–593), and ND7 (aa 496–593). The amino acid number encoded by Grn E Deletion construct: ΔND7 (aa 1–521). All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequence.

Immunoprecipitation

Plasmids of GFP-tagged PGRN and its N-terminal deletion mutants or Grn E deletion mutant ΔND7, or GFP-vector, were transfected in HEK293T cells over 48 hours. Cells were lysed by RIPA lysis and a total of 1 mg protein was used to conduct co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) in each sample. Anti-GFP antibody was used to perform immunoprecipitation and Rab2 antibody was used to probe the protein complex.

Co-localization analysis

To determine the colocalization of PGRN and Rab2, L444P fibroblasts were grown in glass-bottom microwell dishes. When the cell confluency reached 80%, the cells were then fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 5 min at RT. After washing steps, the cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. After further washing steps, the cells were blocked in the 1% (w/v) BSA/PBS at 4°C for 1 hour. Then the cells were incubated with PGRN monoclonal antibody (1:200) and Rab2 polyclonal antibody (1:200) together at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:200) and Cy5-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:200) at room temperature for 1 hour. The cells were then counterstained with 100 ng/mL DAPI for 10 min. Confocal images were taken on a Zeiss LSM710-UV Confocal Microscope.

Measurement of the secreted level of PGRN by ELISA

To determine whether Rab2 deficiency affects the secretion level of PGRN, growth media was removed from cells at 90% confluence and replaced with serum-free medium for 48hrs incubation. The cells and the supernatant were collected separately. The cell lysate was used for western blot, and the supernatant was used to perform ELISA according to the manufacturer of ELISA Kit.

Expression and purification of ND7

The sequence encoding ND7 was inserted into the pD444 expression vector with a His-tag (from DNA2.0, Menlo Park, CA). ND7 was expressed in the BL21(DE3) E. coli strain after induction by 1 mM IPTG. After a 3 h culture, cells were pelleted and sonicated to release the fusion protein. His-tagged ND7 was purified by using His-Select Nickel Affinity Gel (Sigma-Aldrich, Natick, MA, USA). Briefly, E. coli cell lysate were incubated with affinity beads overnight and washed with washing buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 200 mM NaCl, 50 mM Imidazole, pH 8.0) six times. ND7 was eluted from beads with elution buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 200 mM NaCl, 250 mM Imidazole, pH 8.0). After dialysis with PBS, endotoxin removal using Pierce High-Capacity Endotoxin Removal Resin (Cat. No. 2162373.3) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bridgewater, NJ, USA), and 0.2 μm filter sterilization, recombinant ND7 protein was ready to be used.

Autophagic flux analysis

To determine how PGRN KO and Rab2 KO affected autophagic flux, the tandem mCherry-GFP-LC3 assay was used. This assay takes advantage of the differential sensitivity of fluorescence to lysosomal acidity. The GFP fluorescence will be quenched in lysosomes as these are acidic compartments (pH 4–5), whereas the fluorescence of mCherry is relatively stable and retained within lysosomes. When the protein localizes to autophagosomes, mCherry-GFP-LC3 emits both green and red fluorescence signals generating an overall yellow signal. Additionally, the fluorescence of GFP, but not of mCherry, will be quenched within autolysosomes, making autolysosomes appear red. In this way, mCherry-GFP-LC3 tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3 can be used to visualize the transition from neutral autophagosomes to acidic autolysosomes. Briefly, the indicated knockout stable cell lines (PGRN KO or Rab2 KO) were transfected with GFP-mCherry-LC3, 24 h post-transfection, the cells were treated with rapamycin at 37°C overnight and the fluorescence images were taken by confocal microscope. Red and green puncta were counted by manually. Autophagic flux was calculated by the ratio of red/yellow puncta, as described previously [36, 37].

Transmission electron microscope (TEM)

After OVA treatment, WT and PGRN KO mice were anesthetized and the lung was perfused with a fixative containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) for 2 hrs. After washing, the samples were postfixed in 1% OsO4 for 1 hour, followed by block staining with 1% uranyl acetate for 1 hour. Samples were dehydrated and embedded in Embed 812 (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). 60 nm sections were cutted and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate by standard methods. Stained grids were examined under Philips CM-12 electron microscope (FEI; Eindhoven, Netherlands) and photographed with a Gatan (4 k × 2.7 k) digital camera (Gatan, Inc., Pleasanton, CA). The preparation of the cell samples for TEM was done with the assistance of Dr. Fengxia Liang at NYU Medical School OCS Microscopy Core.

For immunogold labeling, the mice lung tissue sections were incubated with antibodies against p62, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies labeled with 5 nm gold particles. Sections were observed under electron microscopy.

Statistical analysis

For comparison of treatment groups, we performed unpaired t-tests, paired t-tests, or one-way ANOVA (where appropriate). All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7 Software. Data are shown as mean ± SD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Results

PGRN deficiency leads to accumulation of autophagosomes in OVA-challenged PGRN null GD model

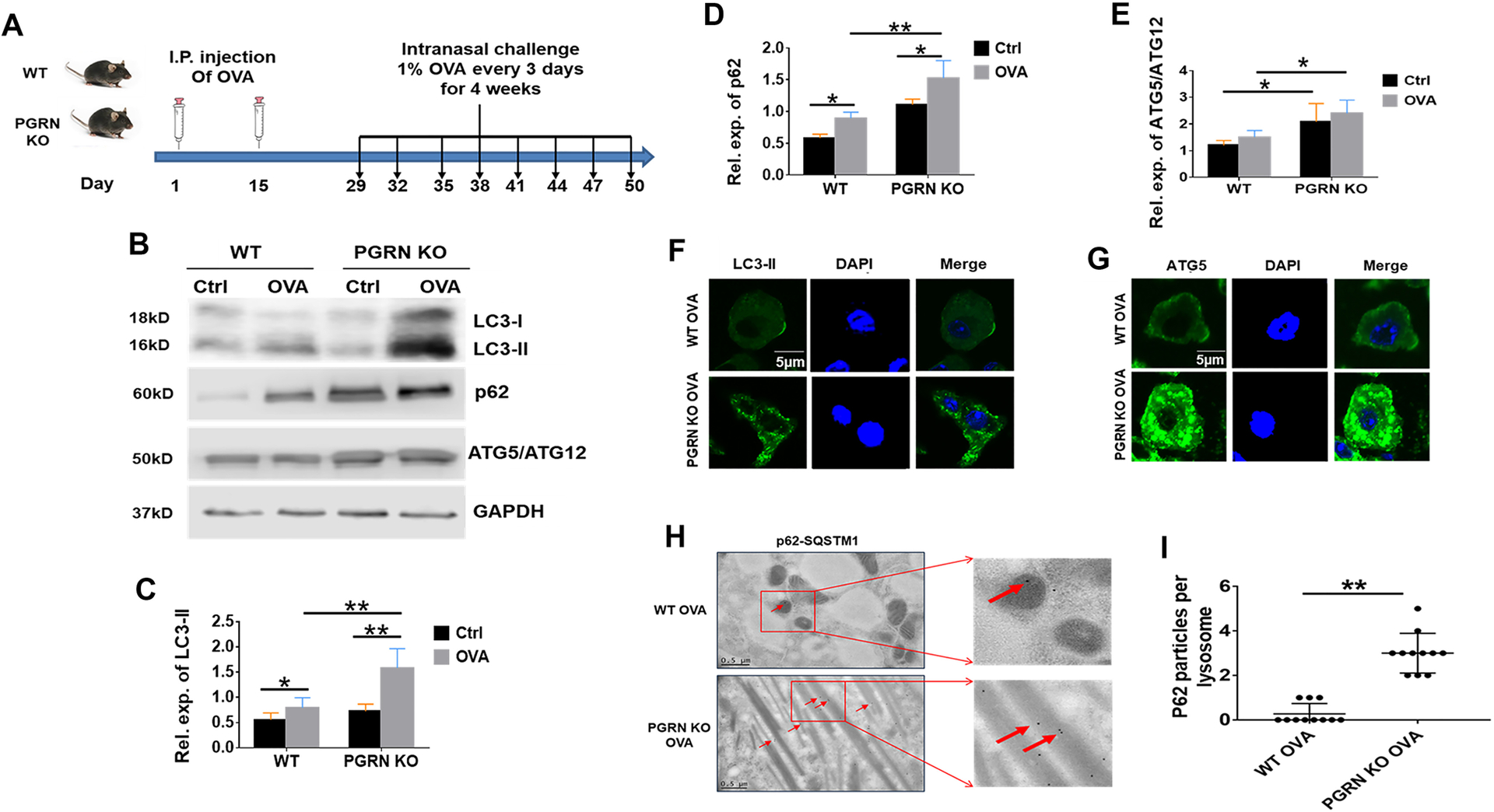

We previously reported that PGRN deficient (PGRN KO) mice developed a typical GD cellular phenotype following ovalbumin (OVA) challenge, as evidenced by enlarged macrophages reminiscent of classic Gaucher-like cells and tubular lysosomes [14]. Leveraging this GD animal model (Fig. 1A), we first examined the levels of autophagy-associated molecules. One of the typical autophagosome markers is LC3, a microtubule-associated protein existing as two isoforms: LC3-I and LC3-II. A post-translational modification converts LC3-I into LC3-II, which is specifically associated with autophagosome membranes and is widely used as an autophagic marker [38, 39]. The level of LC3-II in PGRN KO OVA mice was significantly higher than that in WT OVA mice, suggesting the accumulation of autophagosomes in PGRN KO OVA mice (Fig. 1B, C).

Figure 1. OVA-challenged PGRN KO mice exhibit autophagosome accumulation.

(A) Diagram of the protocol for establishing the mouse model of chronic lung inflammation. WT and PGRN KO mice received I.P. injection of OVA at Day 1 and 15, followed by an intranasal challenge of 1% OVA beginning at Day 29 and administrated thereafter at three times a week for another four weeks. (B) Western blot analysis of LC3, p62, and ATG5/ATG12 complex levels in lung tissues extracted from WT or PGRN KO mice challenged with or without OVA. (C-E) Quantification analysis of LC3-II (C), ATG5/ATG12 complex(D), and LC3 (E) expression level. (F) Immunofluorescence staining of LC3 in lung tissues from WT and PGRN KO mice after OVA challenge. (G) Immunofluorescence staining of ATG5 in lung tissues from WT and PGRN KO mice after OVA challenge. (H) p62-SQSTM1 (arrows) levels assayed by immunogold labeling TEM of lung tissue from WT and PGRN KO mice after OVA challenge. (I) Quantification analysis of H. C, D, E and I, data are mean ± SD; n = 6 mice per group; * p< 0.05 or ** p < 0.01.

Autophagy-related proteins 5 and 12 (ATG5 and ATG12) are two proteins that form a 50 kDa complex which is also involved in the formation of the autophagosome. Therefore, this dimer can be used as a detector of the presence of autophagosomes in an advanced stage of maturation of autophagosomes and its accumulation is directly proportional to the accumulation of non-degraded autophagosomes [40, 41]. As shown in Fig. 1B and D, the two proteins can be observed as a complex (50 kDa) and are accumulated in tissues in PGRN KO OVA mice as compared to WT OVA mice. In addition, immunofluorescence staining of lung tissues from WT and PGRN KO mice challenged with OVA revealed much higher levels of LC3-II and ATG5 in PGRN KO OVA lungs relative to WT controls (Fig. 1F, G).

During autophagy, damaged or misfolded proteins are ubiquitinated, and then colocalize with p62-SQSTM1 followed by delivered to the proteasome for degradation [42]. p62 binds to LC3-II and acts as a bridge between the substrate and the inner membrane of the autophagosome [43, 44]. p62 level is directly proportional to blockade of the autophagic flux since p62 is degraded with the cargo when the autophagic flux is completed, and p62 accumulation indicates the absence of autophagosome degradation [45]. We found that the expression level of p62 was markedly higher in tissues from PGRN KO OVA mice as compared to those from WT OVA mice (Fig. 1B, E). Electron microscopy (EM) images of p62 immunogold labeling of Gaucher cells derived from lung tissues exhibited significant accumulation of p62 in PGRN KO OVA mice as well, further indicative of defective autophagic flux in PGRN KO OVA mice relative to WT counterparts (Fig. 1H, I).

Progranulin deficiency aggravates the GD phenotype in GD patient fibroblasts

Coordination between the autophagic and lysosomal degradation pathways is critical for the cellular turnover of the proteins and organelles [2]. Accordingly, we next examined the effect of PGRN deficiency upon lysosomal storage in GD patient fibroblasts. PGRN was ablated in GD type 2 patient fibroblasts (L444P) using CRISPR-Cas9 technology (Fig. 2A) and knockout efficiency was confirmed by western blotting (Fig. 2B). We previously reported that PGRN binds directly to GCase, functioning as an indispensable adaptor for the formation of a complex between Hsp70 and GCase/LIMP2, which contributes to appropriate lysosomal localization of defective GCase in GD [14]. Approximately 70% of GCase activity was lost in L444P cells compared with WT fibroblasts, and PGRN deficiency led to a further 60% loss of GCase activity, as measured by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of released 4-methylumbelliferone (Fig. 2C). Accordingly, β-glucosylceramide (β-GlcCer), the substrate of GCase, was further accumulated in L444P/PGRN KO fibroblasts (Fig. 2D and E). In addition, as shown in Fig. 2F and G, fluorescence signal intensity, which is indicative of lysosomal storage content, was significantly higher in L444P/PGRN KO relative to L444P control cells, especially following lipid stimulation.

Figure 2. PGRN deficiency exacerbates the GD phenotype in GD patient fibroblasts.

(A) A diagram of the CRISPR/Cas9 technique for construction of human PGRN−/− GD type 2 L444P fibroblasts. (B) The levels of PGRN in PGRN KO (L444P/PGRN KO) and control L444P fibroblasts, assayed by Western blotting. (C) GCase activity in WT, L444P, or L444P/PGRN KO as assayed by release of 4-methylumbelliferone. (D) The distribution of β-glucosylceramide (β-GlcCer, green) in L444P or L444P/PGRN KO fibroblasts. (E) Quantification of (D). (F) Live fluorescence microscopy imaging of LysoTracker Red staining in L444P and L444P/PGRN KO fibroblasts with or without lipid (50μg/ml) stimulation. (G) Quantification of the fluorescence intensity at excitation/emission of 647/668 nm as shown in (F). Data are mean ± SD; * p < 0.05 or ** p < 0.01.

PGRN deficiency causes autophagosome accumulation in GD patient fibroblasts

Given that those autophagosome markers, such as LC3-II, ATG5-ATG12 complex, and p62, accumulate in PGRN KO mice with OVA challenge (Fig. 1), we next employed western blotting to measure these molecular markers of autophagy in L444P GD patient fibroblasts in the presence or absence of PGRN. As shown in Fig. 3A–D, the LC3-II and ATG5-ATG12 complex levels were significantly increased in L444P/PGRN KO in comparison with L444P cells. Elevated LC3-II level could result from early-stage initiation of autophagy or by blockade of autophagic flux at a late stage. Notably, p62, one of the molecular markers of autophagic flux, was also significantly increased in L444P/PGRN KO relative to control L444P fibroblasts, which strongly suggested accumulation of autophagic substrates. Moreover, immunofluorescence staining supported western blotting results (Fig. 3E–H). Additionally, we also examined the mRNA levels of LC3, p62, and Atg12 in L444P and L444P/PGRN KO cells. We found that PGRN deletion did not affect the mRNA levels of LC3, p62, and Atg12, indicating that the increased levels of these molecules associated with PGRN deficiency were due to posttranscriptional protein accumulation (Supplementary Fig. 1). In summary, the increased levels of LC3-II and p62 indicated that the late stage of autophagy was defective in PGRN deficient L444P patient fibroblasts.

Figure 3. PGRN deficiency leads to autophagosome accumulation in GD fibroblasts.

(A) Expression levels of autophagy markers LC3, p62, and ATG5/ATG12 complex in L444P or L444P/PGRN KO with rapamycin (100nM) stimulation, DMSO treatment used as a control. (B-D) Quantification of LC3-II (B), p62 (C), and ATG5/ATG12 complex (D) expression level. (E) ATG5 expression level in L444P or L444P/PGRN KO with or without rapamycin stimulation, assayed by immunofluorescence staining. (F) Quantification of E. (G) p62 expression level in L444P or L444P/PGRN KO with or without rapamycin stimulation or DMSO treatment, assayed by immunofluorescence staining. (H) Quantification of G. B, C, D, F and H, data are mean ± SD; * p < 0.05 or ** p < 0.01.

PGRN deficiency impairs autophagosome-lysosome fusion

The neoformed autophagosome goes through two stages of maturation before fusion and EM could be employed to distinguish the double-membrane of an immature autophagosome from the single-membrane of the lysosome-fused late autophagosome [46]. EM images acquired from WT OVA murine macrophages highlighted the predominance of singe-membraned autophagic vacuoles, while macrophages isolated from PGRN KO OVA mice highlighted the predominance of double-membraned initial autophagic vacuoles (Fig. 4A). These data demonstrated that the deficiency of PGRN resulted in defects in late-stage autophagy. Accordingly, visualization of L444P and L444P/PGRN KO cells using EM revealed a greater abundance of autophagosome initial vacuole in L444P/PGRN KO compared with L444P (Fig. 4B, C).

Figure 4. PGRN deficiency impairs the autophagosome-lysosome fusion.

(A) Initial autophagic or degradative autophagic vacuoles in WT or PGRN KO mice with OVA challenge. Red arrows: Avd (Degradative autophagic vacuole), White arrows: Avi (Initial autophagic vacuole). Scale bar: 1 μm. (B) Ultrastructure of autophagic vacuoles in L444P or L444P/PGRN KO fibroblasts viewed by transmission electron microscopy. Red arrows indicate Avd, white arrows indicate Avi. Scale bar: 200 nm. (C) Quantification of the ratio of Avi to Avd in different cell groups in (B). (D) Co-localization of LC3 and LAMP1 proteins in L444P or L444P/PGRN KO detected by confocal microscope. Red staining: LC3, green staining: LAMP1, rapamycin; 100nM, 24 hrs treatment. (E) Qualitative analysis of D. (F) Confocal microscope analysis of mCherry-GFP-LC3 in L444P or L444P/PGRN KO with or without rapamycin stimulation. Autophagic flux which was indicated by the ratio of red and yellow puncta was quantified and summarized in (G). E, C, G, data are mean ± SD; * p <0.05 or ** p < 0.01.

To further confirm the association between PGRN deficiency and a defect of autophagosome-lysosome fusion, the subcellular localization of the autophagic marker LC3 and the lysosomal protein LAMP1 were investigated with confocal microscope in L444P/PGRN KO fibroblasts [47]. As shown in Fig. 4D and E, co-localization of LC3 and LAMP1 was significantly lower in L444P/PGRN KO compared with L444P fibroblasts. PGRN KO C28i2 chondrocytes (Supplementary Fig. 2A) were also used to examine the co-localization of LC3 and LIMP2. Similarly, co-localization of LIMP2 and LC3 was significantly reduced in PGRN KO C28i2 cells as compared to control cells under rapamycin stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 2D). In addition, the LC3 accumulation was also observed in PGRN KO C28i2 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2B, C). These data suggested that PGRN regulation of autophagosome-lysosome fusion in autophagy may be a mechanism common across different cell types.

In addition, we tested the autophagic flux, which represented autophagosome-autolysosome formation and degradation, in GD fibroblasts using the mCherry-GFP-LC3 assay. Compartment-specific differential quenching of GFP and mRFP fluorescence signals allows the use of mCherry-GFP-LC3 for assessment of the number of autophagosomes and autolysosomes, and quantification of autophagic flux [45, 48, 49]. The numbers of red and yellow punta were quantified with normalization to cell count. The ratio of red puncta to yellow puncta was taken as indicative of the autophagic flux. As shown in Fig. 4 F and G, the autophagic flux was increased after rapamycin stimulation in L444P cells, however, no clear change was observed in L444P/PGRN KO cells with or without rapamycin stimulation, suggesting that autophagosome-autolysosome formation was defective in PGRN deficienct L444P cells.

Bafilomycin A1 (bafA1), an inhibitor of autophagy that disrupts autophagic flux through inhibiting V-ATPase function, was also used to further determine the effect of PGRN deficiency on autophagic flux. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, the LC3-II level was increased in L444P after bafA1 treatment, however, bafA1-associated increase in LC3-II was not observed in PGRN deficient L444P cells, which further indicated that the autophagic flux was defective under PGRN deficiency. Notably, PGRN was reported to affect the pH value of lysosome [50], we accordingly next examined whether deficiency of PGRN could alter lysosomal pH in GD using LysoSensor, and found that PGRN deficiency slightly increased the pH of lysosomes in L444P GD fibroblasts, but this alteration did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Progranulin binds to Rab2 and Grn E of PGRN is the major domain responsible for Rab2 interaction

After the maturation of the autophagosome, the autophagosome and lysosome move closer together and fuse. Once fusion is complete, the contents of the autophagosome are exposed to the lysosome and degraded by the lysosomal hydrolases [51, 52]. Various tethering factors contribute to autophagosome-lysosome fusion. SNAREs are reported to be the core machinery for fusion, the autophagosomal Q-soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) protein syntaxin 7 (STX17) interacts with endosomal/lysosomal R-SNARE VAMP8 to form a trans-SNARE complex, which mediates autophagosome-lysosome fusion [53]. Consecutive Rab-mediation is a critical tethering step for autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Rabs are small GTPases, which regulate autophagic membrane traffic [54, 56]. Rab7 is most widely assumed to regulate autophagosome-lysosome fusion by interacting with various tethering factors [56, 57]. However, a growing body of reports suggests that Rab2 is another critical GTPase mediator of autophagy [58–60]. In our present study, PGRN deficient cells presented with impaired autophagosome-lysosome fusion. We thus hypothesized that PGRN may associate with these aforementioned critical tethering factors including VAMP8, Rab7, or Rab2. To test this hypothesis, we used Nickel beads to pull down His-tagged PGRN, and then the precipitated His-tagged PGRN complex was immunoblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane followed by detection with antibodies against VAMP8, Rab7, or Rab2. As shown in Fig. 5A, Rab2 was co-purified with PGRN, indicating physical interaction between PGRN and Rab2. However, VAMP8 or Rab7 was not detectable in precipitated PGRN complexs. In addition, co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) further demonstrated the interaction between endogenous PGRN and Rab2 in L444P patient fibroblasts (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. PGRN binds to Rab2 and Grn E is the major binding domain for.

(A) Examination of the binding between PGRN and Rab2. Stable HEK293T cell lines expressing PGRN-His were established in our lab previously. PGRN-His protein was purified from the PGRN-His-expressing HEK293T cells using His-Select Nickel Affinity Gel (Sigma-Alrich). Proteins co-purified with His-tagged PGRN were probed with Rab2 antibody. Cell lysate was used as a control. (B) Co-IP assay to examine the binding between PGRN and Rab2 in GD patient fibroblasts. IgG was used as a negative control. (C) Scheme of constructs encoding serial GFP-tagged full-length PGRN (aa 1–593) and N-terminal deletion mutants of PGRN: ND1 (aa45–593), ND2 (aa113–593), ND3 (aa 179–593), ND4 (aa 261–593), ND5 (aa 336–593), ND6 (aa 416–593), ND7 (aa 496–593), and Grn E deletion mutant Δ-ND7. (D) Co-IP assay. HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids encoding GFP-fused full-length PGRN, or PGRN mutants as indicated, and the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with GFP antibody. The complexes were probed with Rab2 antibody. GFP-fused vector was used as a negative control. (E) Qualitative analysis of D. Data are mean ± SD. (F) Co-localization of PGRN and Rab2 by confocal microscope. The co-localization of PGRN and Rab2 was indicated by the white arrow in the merged image. Images were made at ×630 magnifications. (Scale bar, 5μm).

To identify the domain(s) of PGRN required for interacting with Rab2, serial GFP-tagged N-terminal deletions of PGRN were constructed (Fig. 5C). Co-IP was performed using equal loads of these mutants to examine their bindings to endogenous Rab2. As shown in Fig. 5D and E, the binding of PGRN with Rab2 became more pronounced following the deletion of Grn P (ND1); binding became weaker with further deletion of Grn F (ND3) and weakest following deletion of Grn B (ND2 and ND3, respectively). These results suggest that Grn P and F might act as regulatory domains for the binding to Rab2. The Grn E (ND7) fragment exhibited strong binding ability which is undistinguishable from that of full-length PGRN. Interestingly, our previous study found that the Grn E domain was also required and sufficient for PGRN binding to GCase [14]. To further determine whether this Grn E domain is similarly critical for binding with Rab2, a PGRN mutant with E domain deletion (ΔND7) was constructed; Co-IP revealed markedly reduced binding between ΔND7 and Rab2 relative to the interaction observed between full-length PGRN and Rab2 (Fig. 5D and E). Collectively, PGRN has more than one domain involved in the interactions with Rab2, but the C-terminal fragment of PGRN (amino acids 496–593), named ND7, is both required and sufficient for the full interaction with Rab2. In addition, the association of PGRN and Rab2 was further confirmed by their colocalization in L444P fibroblasts (Fig. 5F), which supported the interaction between PGRN and Rab2.

Rab2 deficiency accumulated autophagic markers and defected autophagic flux in L444P GD fibroblasts

Each stage of dynamic autophagic processing, including autophagosome formation, autolysosome formation, and lysosomal degradation intracellular membrane dynamics, is regulated by members of the Ras-like GTPase superfamily - primarily comprised of Rab proteins [54]. Several specific autophagic roles of individual Rab GTPases have been identified and Rab2 has been recognized as a crucial regulator in the formation of autophagosome and autolysosome [58, 61]. To clarify whether binding between Rab2 and PGRN contributes to the role of Rab2 in autophagosome-autolysosome formation in GD, we also established a stable Rab2 KO L444P fibroblast (L444P/Rab2 KO) using CRISPR-Cas9 technique (Supplementary Fig. 5A). Expression levels of autophagic markers LC3 and p62 were analyzed in L444P or L444P/Rab2 KO. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 5B–D, the levels of both LC3-II and p62 were increased in Rab2 KO deficiency L444P, which indicated that the Rab2 deficiency also leaded to the defect of the late stage of autophagy in L444P cells. Autophagic flux was also measured using the tandem mCherry-GFP-LC3 assay. The autophagic flux was significantly lower in L444P/Rab2 KO than that in control L444P cells under rapamycin stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 5E, F). These data revealed that autophagosome-autolysosome formation was blocked in L444P/Rab2 KO GD patient fibroblasts, consistent with previous reports using U2OS and HEK293 cell lines [56].

As Rab2 was identified as a binding partner of PGRN, we examined the potential effect of Rab2 deficiency on the protein and mRNA levels of PGRN. Interestingly, the protein level of PGRN was decreased in L444P/Rab2 KO (Supplementary Fig. 5G), however, the mRNA level of PGRN was not affected by Rab2 deficiency (Supplementary Fig. 5H). We also examined if the deficiency of Rab2 could affect the secretion of PGRN. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 5I, the secreted level of PGRN was not affected by Rab2 deficiency. These data suggested that Rab2 may regulate PGRN at post-transcriptional levels, such as translation and stability of PGRN, in addition to physical interactions with each other.

PGRN derived ND7 effectively ameliorates autophagy defects in GD patient fibroblasts

In our previous study, we found that Grn E is a critical domain for the binding of PGRN to GCase [14]. Interestingly, the Grn E domain is also required for PGRN-Rab2 interaction (Fig. 5). Accordingly, we expressed and purified this C-terminal 98 amino acid fragment of PGRN containing Grn E, termed ND7 (Fig. 6A, B), and tested whether it was sufficient for the mediation of autophagosome-lysosome fusion. First, L444P or L444P/PGRN KO fibroblasts were transfected with GFP-fused vector, or GFP-fused full-length PGRN, or GFP-fused ND7. 24 hrs later, the transfected cells were stimulated with rapamycin for another 24 hrs. Western blotting revealed reduced levels of LC3-II and p62 in full-length PGRN or ND7 transfected L444P/PGRN KO fibroblasts relative to GFP vector-transfected L444P/PGRN KO; moreover, the LC3-II and p62 expression were comparable between full-length PGRN or ND7-transfected L444P/PGRN KO fibroblasts and the control L444P (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. ND7 effectively ameliorates autophagy defects in PGRN deficient GD fibroblasts.

(A) Structure of ND7. (B) Expression and characterization of recombinant ND7. Purified ND7 was analyzed by Coomassie blue staining (left) and western blotting with His antibody (right). (C) Effect of ND7 treatment on autophagic markers LC3-II and p62. L444P/PGRN KO was treated with ND7 recombinant protein (5μg/ml) for 24 hours. (D) Ultrastructure of autophagic vacuoles in L444P. L444P/PGRN KO were treated with ND7 recombinant protein (5μg/ml) for 24 hours and then the ultrastructure of the control L444P, L444P/PGRN KO, or L444P/PGRN KO + ND7, was observed under transmission electron microscope. Red arrows indicate Avd, white arrows indicate Avi. Scale bar: 200nm. (E) Quantification of the ratio of Avi to Avd in different cell groups. (F) Confocal microscope analysis of mCherry-GFP-LC3 in L444P or L444P/PGRN KO with or without recombinant ND7 (5μg/ml) administration in the absence or presence of rapamycin. Autophagic flux which was indicated by the ratio of red and yellow puncta was quantified and summarized in (G). E, G, data are mean ± SD; * p < 0.05 or ** p < 0.01.

We next tested the effect of ND7 on the formation of autophagosomes using EM. As shown in Fig. 6D, E, L444P/PGRN KO fibroblasts treated with ND7 exhibited a shift toward the prevalence of advanced degradative vacuoles to a degree comparable with L444P. The mCherry-GFP-LC3 assay revealed that autophagic flux was significantly increased in ND7 treated L444P/PGRN KO compared with untreated L444P/PGRN KO under rapamycin stimulation (Fig. 6F, G). Moreover, autophagic flux was also increased in ND7 treated L444P/PGRN KO (Fig. 6F, G). Taken together, ND7 administration could rescue the autophagic defect in PGRN KO GD L444P fibroblasts. Moreover, in lung tissues of OVA-challenged PGRN KO mice, levels of LC3-II and p62 also decreased drastically after ND7 administration as assessed by western blotting (Supplementary Fig. 6A). In line with these results, immunofluorescence staining for LC3 revealed that ND7 could significantly decrease the levels of LC3-II and P62 (Supplementary Fig. 6B).

Discussion

Our previous studies demonstrated that PGRN KO mice presented with Gaucher cells, especially after the OVA challenge, and this GD cellular phenotype could be ameliorated by administration of recombinant PGRN and its derivative ND7, indicating a critical role of PGRN in GD pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention [14, 32]. It has been reported that PGRN deficiency associates with reduced autophagic flux in neurons and impaired autophagy in neuropathic diseases [28]. Moreover, screening for regulatory genes targeting neuronal PGRN expression has revealed enrichment of genes from the autophagy-lysosome pathway; in turn, modulating PGRN expression exerts regulatory effects upon the autophagy-lysosome pathway [34, 62]. In the current study, we observed elevated expressions of LC3-II, p62, and ATG5-ATG12 complex in PGRN KO tissues, especially after OVA challenge, indicating accumulation of autophagosomes in PGRN deficient mice (Fig. 1B–E). Notably, PGRN is capable of activating upstream modulators of the mechanistic targets of rapamycin and, in turn, mTOR signaling [30, 63]. mTOR signaling contributes to the regulation of various fundamental cell processes including autophagy, with stimulation of mTORC1, but not mTORC2, inhibitive of autophagy [34, 62, 64–66]. Accordingly, increased levels of LC3-II and ATG5/ATG12 complex in PGRN KO mice, particularly under stress associated with OVA challenge, may be reflective of reduced activation of the mTOR signaling pathway associated with PGRN deficiency. Interestingly, accumulated p62 was also observed in the tubular-like lysosomes of macrophages from PGRN KO mice after OVA challenge (Fig. 1H, I). Accumulated p62 suggests the absence of autophagosome degradation in PGRN deficient mice, which could be due to inhibition of the initial stage of autophagy or a defect in autophagosome-lysosome fusion [3]. The increased levels of LC3-II and ATG5/ATG12 complex, markers for initial stage of autophagy, indicated that the autophagosome-lysosome fusion, but not autophagy initiation, was defective in PGRN deficient cells and mice. This defect in autophagosome-lysosome fusion, in turn, led to impaired clearance of autophagosome proteins in PGRN KO cells/mice.

To complement our in vivo murine data, PGRN was knocked out in neuropathic type 2 GD L444P patient fibroblasts using CRISPR-Cas9 (Fig. 2A, B). Consistent with in vivo results, the levels of LC3-II, p62, and ATG5/ATG12 complex were increased in L444P/PGRN KO as compared with L444P cells (Fig. 3), indicating that PGRN dificiency resulted in the defective lysosome degradation in GD patient L444P fibroblasts. Although increased LC3-II level could be induced by either activated autophagy or inhibited autophagosome degradation [3], the observation of increased p62 levels without rapamycin stimulation bolsters the conclusion that autophagosome degradation is blocked in L444P/PGRN KO fibroblasts, which may slow the decay of LC3-II. PGRN is known to play an important role in GCase lysosomal localization through acting as a co-chaperone of GCase and HSP70 complex [14]. PGRN deficiency in L444P may worsen lysosome degradation defects in patient L444P fibroblasts. Rapamycin stimulation, which induces autophagy through inhibition of mTOR activity, did not affect the levels of LC3-II and p62 in L444P/PGRN KO fibroblasts. In L444P/PGRN KO, inhibition of the mTOR signaling pathway caused by PGRN deficiency may occlude observation of the effects of the rapamycin.

Autophagosome-autolysosome fusion is an obligatory step for the clearance of the autophagosomes in the late stage of autophagy [67]. We also evaluated fusion in the presence and absence of PGRN by visualization of differential morphology of autophagosomes and autolysosomes under EM [68]. In the GD-like macrophages from PGRN KO mice after OVA challenge, most of the autophagic vacuoles exhibited the double membrane characteristic of autophagosomes [69]; while in WT mice, most of the autophagic vacuoles were identifiable as single membraned autolysosomes, indicating that PGRN deficiency leads to a defect in fusion between autophagosome and lysosome. Defective autophagosome-lysosome fusion was further confirmed by the decreased co-localization of autophagosome marker LC3 and lysosome markers LAMP1 or LIMP2 in PGRN deficient cells, both in L444P GD fibroblasts and C28i2 cells (Figs. 4, Supplementary Fig. 2D). In addition, the defective autophagic flux under PGRN deficiency was also confirmed using additional approaches, including tandem mCherry-GFP-LC3 assay and application of autophagy inhibitor bafA1(Figs. 4, Supplementary Fig. 3).

To investigate the mechanisms underlying impaired autophagosome and lysosome fusion in PGRN KO cells, we examined whether PGRN associated with several reported critical tethering factors: VAMP8, Rab7, and Rab2. Intriguingly, we found that PGRN selectively interacts with Rab2, and the Grn E domain is critical for this interaction (Fig. 5D, E). Recent studies have demonstrated that Rab2 plays an important role in autophagy by acting as a key factor for autophagic and endocytic cargo delivery and degradation in lysosomes [59, 61] and as a regulator of the formation of autophagosome and autolysosome in mammalian cells [58]. Consistently, the deficiency of Rab2 aggravated defective autophagy degradation in L444P patient fibroblasts. Furthtermore, autophagic flux was impaired alongside downregulation of PGRN protein expression in Rab2 KO L444P fibroblasts (Supplementary Fig. 5). Taken together, the findings in this study demonstrate that PGRN physically interacts with Rab2, and both proteins are needed to link autophagosomes and lysosomes together, i.e. fuse; and deficiency of either PGRN or Rab2 impairs autophagosome-lysosome fusion, which in turn leads to the accumulation of autophagosomes.

Mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) in response to changes in the intracellular environment. Increased ROS production, in turn, causes mitochondrial defects and the oxidative damage produced by free radicals is extensive in the lungs of mice treated with OVA [69]. Accumulation of damaged mitochondria is toxic and the cell has developed a type of specific autophagy, called mitophagy, as a defense mechanism to promote the removal of these organelles [70, 71]. Accordingly, we also monitored mitochondrial morphology and markers of mitophagy in GD macrophages of WT and PGRN KO mice after the OVA challenge. OVA-challenged PGRN KO mice exhibited consistent mitochondrial damage (Supplementary Fig. 7A). Bcl2-L13 is the mammalian homolog of mitophagy-specific gene Atg32, the protein product of which recognizes damaged mitochondria and accompanies them to degradation [72, 73]. Consistent with EM images, immunofluorescence imaging of Bcl2-L13 from PGRN KO OVA mice tissues illustrated significant accumulation of Bcl2-L13 relative to that observed in tissues extracted from WT OVA mice (Supplementary Fig. 7B). In addition, recombinant PGRN or ND7 administration restored Bcl2-L13 expression level, indicating that treatment favors the clearance of damaged mitochondria (Supplementary Fig. 7C). Prior work has noted defective mitochondrial function and mitophagy in association with GBA mutations [10, 11, 74, 75]. In our GD model, OVA-challenged PGRN KO mice developed a GD phenotype in a manner independent of GBA mutation; therefore, a disparate mechanism may underlie the accumulation of damaged mitochondria in OVA-challenged PGRN KO mice. While the accumulation of damaged mitochondria in PGRN KO mice after OVA challenge may be caused by impaired autophagosome-lysosome fusion, the effect of PGRN on mitophagy in GD warrants further investigation.

PGRN, particularly its derivative ND7, may be a new treatment for GD patients. However, additional investigations with additional GD models are needed to further test its therapeutic effect and safety. Moreover, it would be interesting to further investigate the role of PGRN in additional stages of autophagy in the context of GD and other lysosomal storage diseases. The identification of PGRN deficiency/insufficiency as a risk factor for GD is certainly a source of considerable excitement in the field, especially after the confirmation of its involvement in autophagy in GD. This study is the first to identify PGRN as a novel factor required for autophagosome-lysosome fusion, thus providing a solid foundation for future discoveries relating to this critical factor in autophagy and probably mitophagy as well. More importantly, this study yields the discovery of an approximately 15-kDa PGRN derivative, ND7, that effectively ameliorates PGRN deficiency associated defects in autophagy as well as GD phenotypes. In brief, this study carries the potential, not only for future advances in understanding autophagy in the pathogenesis of GD but also for the development of novel therapies to combat GD, particularly neuronopathic GD which currently lacks the drugs/treatments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Yan Deng and Fengxia Liang at NYU Medical School OCS Microscopy Core for their assistance with confocal and electronic microscope images. We also thank all lab members for the insightful discussions. All authors disclose no conflict of interest. Patents have been filed by NYU that claim PGRN and its derivatives for the diagnosis and treatment of Gaucher disease (PCT/US2015014364).

Funding

This work was supported partly by NIH research grants R01NS103931, R01AR062207, R01AR061484, and R01AR076900.

Footnotes

Ethics approval The full name of the Ethics Committee, from which written approval was obtained allowing to carry out the experiments, is stated in the “Materials and methods” section.

Conflict of interest The authors declare no competing interests.

Data transparency All authors confirm that all data and material support their published claims and comply with field standards.

References

- 1.Glick D, Barth S, and Macleod KF, Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol, 2010. 221(1): p. 3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Settembre C, et al. , Lysosomal storage diseases as disorders of autophagy. Autophagy, 2008. 4(1): p. 113–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinghorn KJ, Asghari AM, and Castillo-Quan JI, The emerging role of autophagic-lysosomal dysfunction in Gaucher disease and Parkinson’s disease. Neural Regen Res, 2017. 12(3): p. 380–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seranova E, et al. , Dysregulation of autophagy as a common mechanism in lysosomal storage diseases. Essays Biochem, 2017. 61(6): p. 733–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Platt FM, Sphingolipid lysosomal storage disorders. Nature, 2014. 510(7503): p. 68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, et al. , Molecular regulations and therapeutic targets of Gaucher disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 2018. 41: p. 65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grabowski GA, Gaucher disease and other storage disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program, 2012. 2012: p. 13–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitcairn C, Wani WY, and Mazzulli JR, Dysregulation of the autophagic-lysosomal pathway in Gaucher and Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis, 2019. 122: p. 72–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun Y and Grabowski GA, Impaired autophagosomes and lysosomes in neuronopathic Gaucher disease. Autophagy, 2010. 6(5): p. 648–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H, et al. , Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy defect triggered by heterozygous GBA mutations. Autophagy, 2019. 15(1): p. 113–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moren C, et al. , GBA mutation promotes early mitochondrial dysfunction in 3D neurosphere models. Aging (Albany NY), 2019. 11(22): p. 10338–10355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li SS, et al. , Reduction of PGRN increased fibrosis during skin wound healing in mice. Histol Histopathol, 2019. 34(7): p. 765–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jian J, Konopka J, and Liu C, Insights into the role of progranulin in immunity, infection, and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol, 2013. 93(2): p. 199–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jian J, et al. , Progranulin Recruits HSP70 to beta-Glucocerebrosidase and Is Therapeutic Against Gaucher Disease. EBioMedicine, 2016. 13: p. 212–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jian J, et al. , Progranulin: A key player in autoimmune diseases. Cytokine, 2018. 101: p. 48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bateman A and Bennett HP, The granulin gene family: from cancer to dementia. Bioessays, 2009. 31(11): p. 1245–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui Y, Hettinghouse A, and Liu CJ, Progranulin: A conductor of receptors orchestra, a chaperone of lysosomal enzymes and a therapeutic target for multiple diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 2019. 45: p. 53–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bateman A, Cheung ST, and Bennett HPJ, A Brief Overview of Progranulin in Health and Disease. Methods Mol Biol, 2018. 1806: p. 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker M, et al. , Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature, 2006. 442(7105): p. 916–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arrant AE, et al. , Restoring neuronal progranulin reverses deficits in a mouse model of frontotemporal dementia. Brain, 2017. 140(5): p. 1447–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gotzl JK, et al. , Common pathobiochemical hallmarks of progranulin-associated frontotemporal lobar degeneration and neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Acta Neuropathol, 2014. 127(6): p. 845–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendsaikhan A, Tooyama I, and Walker DG, Microglial Progranulin: Involvement in Alzheimer’s Disease and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells, 2019. 8(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chitramuthu BP, Bennett HPJ, and Bateman A, Progranulin: a new avenue towards the understanding and treatment of neurodegenerative disease. Brain, 2017. 140(12): p. 3081–3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang W, et al. , The growth factor progranulin binds to TNF receptors and is therapeutic against inflammatory arthritis in mice. Science, 2011. 332(6028): p. 478–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jian J, et al. , Progranulin directly binds to the CRD2 and CRD3 of TNFR extracellular domains. FEBS Lett, 2013. 587(21): p. 3428–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu C, et al. , Progranulin-derived Atsttrin directly binds to TNFRSF25 (DR3) and inhibits TNF-like ligand 1A (TL1A) activity. PLoS One, 2014. 9(3): p. e92743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li M, et al. , Progranulin is required for proper ER stress response and inhibits ER stress-mediated apoptosis through TNFR2. Cell Signal, 2014. 26(7): p. 1539–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang MC, et al. , Progranulin deficiency causes impairment of autophagy and TDP-43 accumulation. J Exp Med, 2017. 214(9): p. 2611–2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo Q, et al. , Progranulin causes adipose insulin resistance via increased autophagy resulting from activated oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Lipids Health Dis, 2017. 16(1): p. 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 30.Zhou B, et al. , Progranulin induces adipose insulin resistance and autophagic imbalance via TNFR1 in mice. J Mol Endocrinol, 2015. 55(3): p. 231–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J, et al. , PGRN induces impaired insulin sensitivity and defective autophagy in hepatic insulin resistance. Mol Endocrinol, 2015. 29(4): p. 528–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jian J, et al. , Association Between Progranulin and Gaucher Disease. EBioMedicine, 2016. 11: p. 127–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Y, et al. , Progranulin associates with hexosaminidase A and ameliorates GM2 ganglioside accumulation and lysosomal storage in Tay-Sachs disease. J Mol Med (Berl), 2018. 96(12): p. 1359–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elia LP, et al. , Genetic Regulation of Neuronal Progranulin Reveals a Critical Role for the Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway. J Neurosci, 2019. 39(17): p. 3332–3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coffey EE, et al. , Lysosomal alkalization and dysfunction in human fibroblasts with the Alzheimer’s disease-linked presenilin 1 A246E mutation can be reversed with cAMP. Neuroscience, 2014. 263: p. 111–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castillo K, et al. , Measurement of autophagy flux in the nervous system in vivo. Cell Death and Disease, 2013, 4, e917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi Huiying, et al. , Na+/H+ Exchanger Regulates Amino Acid-Mediated Autophagy in Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2017; 42: 2418–2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tooze SA and Yoshimori T, The origin of the autophagosomal membrane. Nat Cell Biol, 2010. 12(9): p. 831–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parzych KR and Klionsky DJ, An overview of autophagy: morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2014. 20(3): p. 460–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mizushima N, The ATG conjugation systems in autophagy. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 2020. 63: p. 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romanov J, et al. , Mechanism and functions of membrane binding by the Atg5-Atg12/Atg16 complex during autophagosome formation. EMBO J, 2012. 31(22): p. 4304–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen M, et al. , TRIM14 Inhibits cGAS Degradation Mediated by Selective Autophagy Receptor p62 to Promote Innate Immune Responses. Mol Cell, 2016. 64(1): p. 105–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lamark T, Svenning S, and Johansen T, Regulation of selective autophagy: the p62/SQSTM1 paradigm. Essays Biochem, 2017. 61(6): p. 609–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Danieli A and Martens S, p62-mediated phase separation at the intersection of the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy. J Cell Sci, 2018. 131(19). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshii SR and Mizushima N, Monitoring and Measuring Autophagy. Int J Mol Sci, 2017. 18(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eskelinen EL, Maturation of autophagic vacuoles in Mammalian cells. Autophagy, 2005. 1(1): p. 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Settembre C, et al. , A block of autophagy in lysosomal storage disorders. Hum Mol Genet, 2008. 17(1): p. 119–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matus S, Valenzuela V, and Hetz C, A new method to measure autophagy flux in the nervous system. Autophagy, 2014. 10(4): p. 710–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.von Muhlinen N, Methods to Measure Autophagy in Cancer Metabolism. Methods Mol Biol, 2019. 1928: p. 149–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanaka Y, et al. , Progranulin regulates lysosomal function and biogenesis through acidification of lysosomes. Hum Mol Genet, 2017. 26(5): p. 969–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu L, Chen Y, and Tooze SA, Autophagy pathway: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Autophagy, 2018. 14(2): p. 207–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Y and Yu L, Development of Research into Autophagic Lysosome Reformation. Mol Cells, 2018. 41(1): p. 45–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Itakura E, Kishi-Itakura C, and Mizushima N, The hairpin-type tail-anchored SNARE syntaxin 17 targets to autophagosomes for fusion with endosomes/lysosomes. Cell, 2012. 151(6): p. 1256–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takats S, et al. , Small GTPases controlling autophagy-related membrane traffic in yeast and metazoans. Small GTPases, 2018. 9(6): p. 465–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakamura S and Yoshimori T, New insights into autophagosome-lysosome fusion. J Cell Sci, 2017. 130(7): p. 1209–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuchitsu Y and Fukuda M, Revisiting Rab7 Functions in Mammalian Autophagy: Rab7 Knockout Studies. Cells, 2018. 7(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jager S, et al. , Role for Rab7 in maturation of late autophagic vacuoles. J Cell Sci, 2004. 117(Pt 20): p. 4837–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ding X, et al. , RAB2 regulates the formation of autophagosome and autolysosome in mammalian cells. Autophagy, 2019. 15(10): p. 1774–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lorincz P, et al. , Rab2 promotes autophagic and endocytic lysosomal degradation. J Cell Biol, 2017. 216(7): p. 1937–1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lund VK, Madsen KL, and Kjaerulff O, Drosophila Rab2 controls endosome-lysosome fusion and LAMP delivery to late endosomes. Autophagy, 2018. 14(9): p. 1520–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fujita N, et al. , Genetic screen in Drosophila muscle identifies autophagy-mediated T-tubule remodeling and a Rab2 role in autophagy. Elife, 2017. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Altmann C, et al. , Progranulin overexpression in sensory neurons attenuates neuropathic pain in mice: Role of autophagy. Neurobiol Dis, 2016. 96: p. 294–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feng T, et al. , Growth factor progranulin promotes tumorigenesis of cervical cancer via PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Oncotarget, 2016. 7(36): p. 58381–58395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saxton RA and Sabatini DM, mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell, 2017. 168(6): p. 960–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Codogno P and Meijer AJ, Autophagy and signaling: their role in cell survival and cell death. Cell Death Differ, 2005. 12 Suppl 2: p. 1509–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Noda T, Regulation of Autophagy through TORC1 and mTORC1. Biomolecules, 2017. 7(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lorincz P and Juhasz G, Autophagosome-Lysosome Fusion. J Mol Biol, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eskelinen EL, To be or not to be? Examples of incorrect identification of autophagic compartments in conventional transmission electron microscopy of mammalian cells. Autophagy, 2008. 4(2): p. 257–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reddy PH, Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Asthma: Implications for Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant Therapeutics. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2011. 4(3): p. 429–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sachdeva K, et al. , Environmental Exposures and Asthma Development: Autophagy, Mitophagy, and Cellular Senescence. Front Immunol, 2019. 10: p. 2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Garza-Lombo C, et al. , Redox homeostasis, oxidative stress and mitophagy. Mitochondrion, 2020. 51: p. 105–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kanki T, et al. , Atg32 is a mitochondrial protein that confers selectivity during mitophagy. Dev Cell, 2009. 17(1): p. 98–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Otsu Kinya., e.a., BCL2L13 is a mammalian homolog of the yeast mitophagy receptorAtg32. Autophgy, 2015: p. 1932–-1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gegg ME and Schapira AH, Mitochondrial dysfunction associated with glucocerebrosidase deficiency. Neurobiol Dis, 2016. 90: p. 43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Osellame LD and Duchen MR, Defective quality control mechanisms and accumulation of damaged mitochondria link Gaucher and Parkinson diseases. Autophagy, 2013. 9(10): p. 1633–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.