Abstract

Bacillus licheniformis is a multi-metal tolerant bacteria, isolated from the paddy rhizospheric soil sample. Upon the multiple metal toxicity, B. licheniformis altered their phenotypic/morphogenesis. Here we examined the effects of cadmium (Cd2+), chromium (Cr2+), and mercury (Hg2+) on the morphogenesis of B. licheniformis in comparison to control. We found that the ability of bacteria to grow effectively in presence of cadmium and chromium comes at a cost of acquiring cell density-driven mobility and reformation of filamentous to donut shape respectively. In particular, when bacteria grown on mercury it showed the bacteriostatic strategy to resist mercury. Furthermore, the findings suggest a large variation in the production of exo-polysaccharides (EPS) and suggest the possible role of EPS in gaining resistance to cadmium and chromium. Together this study identifies previously unknown characteristics of B. licheniformis to participate in bioremediation and provides the first evidence on positive effects of bacterial morphogenesis and the involvement of EPS in bacteria to resisting metal toxicity.

Keywords: Bacillus licheniformis, Multicellularity of bacteria, Colonial dynamics, Exopolysaccharides, Heavy metal-resistant bacteria

Microbes develop resistance as a result of a natural Darwinian process [1]. When a microbial community is disrupted by biological or chemical means, the community adapts to survive or recover [2] and understanding bacteria’s ability to survive in harsh environments would improve the feasibility of using them in biotechnological applications [3]. In case of bacterial resistance to metals, it’s remarkable that studies all over the world have identified altered efflux mechanisms [4], intercellular bioaccumulation [5], bio-precipitation [6], biofilm mediated immobilization [7], methylation, and enzymatic transformation. Despite a general understanding of bacteria’s regulatory mechanisms for resistance to various metals [8–11], no research has been done to date on metal-specific interactive dynamics and the bacterial community’s system approach to metal resistance. For the first time, the findings of this study demonstrate the importance of different morphological phenotypes in bacterial resistance to metal toxicity.

Bacteria was isolated from paddy rhizospheric soil sample from the field irrigated with wastewater (13° 54′ 05.8″ N 75° 36′ 59.4″ E), the strain was identified as B. licheniformis based on sequence homology of 16 s rDNA. The gene sequence of the bacteria has been deposited in GenBank (accession No. KP877534). For culturing the bacteria Luria Bertani (LB) agar medium was used. To evaluate bacterial morphological variability sterilized LB agar was used. The plates were modified with 1 mM concentrations of cadmium chloride (CdCl2), potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7), and 0.2 mM of mercury and thoroughly mixed; a loop full of B. licheniformis colony was then point-inoculated at the center of the plates and constantly observed for morphological variations. The experiments were done in triplicates, and results were recorded and photographed with Nikon D3400 camera. Further for the quantitative estimation exopolysaccharides, the inoculum concentration was spectrophotometrically adjusted to 1.0 at A600 nm before being transferred to 50 ml of LB broth containing various metals such as cadmium, chromium, and mercury at 1.0 mM, 1.0 mM, and 0.2 mM respectively. The supernatant was collected when turbidity of culture reached 1.5 OD at A600 nm by centrifugation (11,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C). The clear supernatant was gathered, and EPSs was precipitated with minimal modulation in protocol described by [12] to evaluate the involvement of exocellular polysaccharide in acquiring metal resistance.

‘Bioremediation’ highlights the significance and feasibility in practical implication of microbes in wastewater treatment [13, 14]. It is well known that wastewater irrigation is used in urban agriculture to alleviate water scarcity. The main goal of this study was to use microbes’ adaptive abilities in harsh environment. Paddy rhizospheric soils were collected to isolate metal-resistant bacteria as it demands large amount of water compared to other cropping systems [15–17] and offers long-term interaction for microbial consortia, helps in acquiring abilities to survive and multiply. In this study, bacteria from the paddy rhizospheric soil were isolated and characterized as B. licheniformis using 16s rDNA sequencing and nucleotide blast analysis. Further, the evolutionary history was analyzed by Clustal W alignments through Neighbor-Joining method (Fig. 1) in Mega X software with Tamura-Nei Model having the 1000 bootstrap values [18].

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree analysis based on 16 S rDNA gene sequences

The metal toxicity-driven morphological variations in B. licheniformis were purely coincidental findings. The available literature strongly supports role of bacterial multicellularity in complex biochemical processes and stresses bacteria’s inability to perform similar functions as effectively as a well-organized group Ben-Jacob et al., (1998). Studies were carried out to assess the morphological behaviour of B. licheniformis against cadmium, chromium, and mercury based on interest. LB agar was prepared as per the manufacturer’s instructions to ensure an equal concentration of agar, which is known to affect bacterial morphogenesis [19]. In experiments to investigate B. licheniformis multicellularity, spectacular variations in morphological behavior were observed in presence of chromium and cadmium (Figs. 2 and 3). Starting on the first day, bacteria grown on LB agar modified with chromium showed wide range of variations compared to the control plate. Colonies with indentations initially emerged from the point of inoculation and quickly covered the plate with dense colonies (Fig. 2b). Surprisingly, after 48 h, the colonies’ patterns showed significant differences Fig. 2e, f), by the production of wetting extracellular fluid at the centre, as well as the formation of donut-shaped colonies lubricated and emerging from the centre. The reason for the production of the wetting fluid is related to cell–cell signalling exerted by a wide range of chemical interactions, which was observed until the tenth day of the incubation period [20]. As a result, the role of the wetting fluid in the formation of donut-shaped colonies can be suspected, and future research into the role of morphological variations in achieving resistance to metals will be a better issue.

Fig. 2.

B. licheniformis morphogenesis induced by chromium a Colony grown on LB agar with marginal indentations (control). b Culture challenged with chromium, the colony with central indentations from the point of inoculation. c Culture growth curve control (blue) and culture challenged with chromium (red). d showing pale whitish-yellow lubrication at the inoculation site, an extended period of incubation, resulted in restructured colonial morphology (e, f) Clear donut-shaped colony lubricated with whitish wetting fluid produced at the inoculation site (Color figure online)

Fig. 3.

Cell density mediated response of B. licheniformis to cadmium toxicity. a Culture on LB agar (control) with marginal indentations. b Culture challenged with cadmium observed after two days of incubation interval showing no growth. c, f Cells continued to grow and remained clumped together by avoiding spreading over the plate, d Colony on fourteenth fourteen days of incubation. e Growth curve shows a range of responses, with the control (blue) and culture challenged with cadmium (red) highlighting an extended lag phase (Color figure online)

In almost all biological systems, the division of labour remains a key feature. Several studies in recent years have primarily focused on defining microbial division of labour under various experimental conditions [21, 22]. This division of labour has been proven to be a bacterial cell’s collective response to environmental challenges [22]. When tested against cadmium, B. licheniformis showed similar, coordinated collective response of bacterial cell groups (Fig. 3). The bacteria were inoculated on agar plates with 1 mM cadmium and observed for 20 days. There was no growth until 5 days, which may be due to an extended lag phase (Fig. 3b). The colonies grew with a convex elevation, after extended period of incubation the production of an extracellular slimy lubricant was observed with the continued convex elevation (Fig. 3c, d, f), and the similar results were observed in the broth culture system (Fig. 3e) until fourteenth days. On the fifteenth day of incubation, grouped cells were found to scatter with a highly coordinated movement in pre-planned directions, creating an irregular web-like structure across the plate. Similar to the evidence points observed by Butler et al. [23], bacterial resistance to cadmium is found to be driven by cell density. For the first time, this study shows that metal-specific morphological variations in B. licheniformis (Figs. 3, 4).

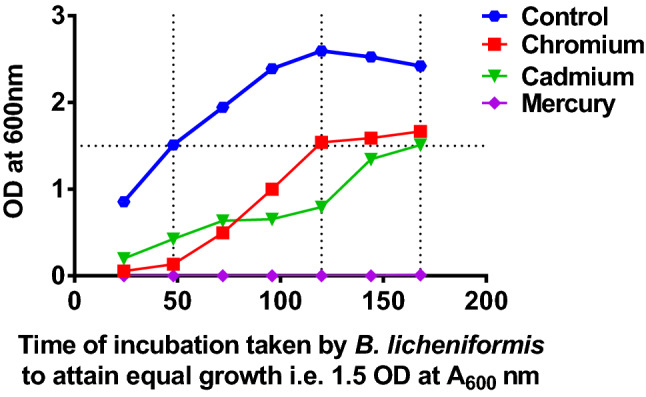

Fig. 4.

Indicates turbidometric measurement of B. licheniformis inoculated to LB broth with no metal amendment (blue) LB broth with 1 mM chromium (red), LB broth with 1 mM cadmium (green) and LB broth with 0.2 mM mercury (purple) (Color figure online)

The effect of metals on production of exopolysaccharides was used to determine variation in extracellular components in response to metals (Fig. 5). And results shown the substantial differences in exopolysaccharide concentrations against cadmium and chromium (Fig. 5), as reported earlier [24]. Furthermore, bacteriostatic strategy by B. licheniformis is found to be exclusive to acquire resistance to mercury, thus offers new insights towards understanding the prominence of metal specific behaviour in bacteria.

Fig. 5.

Graphical representation of amount of exo-polysaccharides produced by B. licheniformis against various metal-induced stress

This study provides the first insight on metal-specific phenotype to withstand toxicity in bacteria, and advocates the importance of uncovering metabolic and molecular imprints involved in selection of metal-specific morphological variance. However, understanding molecular and proteomic figure-prints involved in xenobiotics driven multicellularity in bacteria might provide researchers and pharma companies an innovative and alternative strategies to investigate possible and effective targets to combat bacterial antibiotic resistance [25, 26], and for repurposing biomolecules in designing effective antimicrobials [27] by aligning with metabolic and genomic databases [28].

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledges the support by the Department of Studies in Biotechnology, University of Mysore. The Treasurer, Global Association of Scientific Young Minds, Pradeep Kumar P. M. for his assistance in soil sample collection and for the financial support under GASYM research grant. SCR also acknowledges MMK and SDM, College for Women, Mysuru for the facilities.

Funding

This work is partially supported by University Grant Commission File No. F. 41–525/2012 (SR).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare No Conflict of Interest with this present research report. (The formulation including bacteria and other component is filled for US patent, with SEED Health Pvt. Ltd. California, USA)

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Channarayapatna-Ramesh Sunilkumar, Email: sunil.channarayapatna.ramesh@gmail.com.

Nagaraja Geetha, Email: geetha@appbot.uni-mysore.ac.in.

References

- 1.Howard SJ, Hopwood S, Davies SC. Antimicrobial resistance: A global challenge. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:1–2. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meredith HR, Andreani V, Ma HR et al (2018) Applying ecological resistance and resilience to dissect bacterial antibiotic responses. Sci Adv 4:eaau1873. 10.1126/sciadv.aau1873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Kumar P, Patel SKS, Lee J-K, Kalia VC. Extending the limits of Bacillus for novel biotechnological applications. Biotechnol Adv. 2013;31:1543–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naik T, Vanitha SC, Rajvanshi PK, et al. Novel Microbial Sources of Tropane Alkaloids: First Report of Production by Endophytic Fungi Isolated from Datura metel L. Curr Microbiol. 2018;75:206–212. doi: 10.1007/s00284-017-1367-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blindauer CA, Harrison MD, Robinson AK, et al. Multiple bacteria encode metallothioneins and SmtA-like zinc fingers. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:1421–1432. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kulkarni S, Ballal A, Apte SK. Bioprecipitation of uranium from alkaline waste solutions using recombinant Deinococcus radiodurans. J Hazard Mater. 2013;262:853–861. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalia VC, Prakash J, Koul S, Ray S. Simple and rapid method for detecting biofilm forming bacteria. Indian J Microbiol. 2017;57:109–111. doi: 10.1007/s12088-016-0616-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dell’Amico E, Mazzocchi M, Cavalca L, et al. Assessment of bacterial community structure in a long-term copper-polluted ex-vineyard soil. Microbiol Res. 2008;163:671–683. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Das S, Dash HR, Chakraborty J. Genetic basis and importance of metal resistant genes in bacteria for bioremediation of contaminated environments with toxic metal pollutants. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100:2967–2984. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waldron KJ, Robinson NJ. How do bacterial cells ensure that metalloproteins get the correct metal? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:25–35. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chauhan NS, Ranjan R, Purohit HJ, et al. Identification of genes conferring arsenic resistance to Escherichia coli from an effluent treatment plant sludge metagenomic library. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2009;67:130–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narancic T, Djokic L, Kenny ST, et al. Metabolic versatility of Gram-positive microbial isolates from contaminated river sediments. J Hazard Mater. 2012;215–216:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalia VC, Jain SR, Kumar A, Joshi AP. Frementation of biowaste to H 2 by Bacillus licheniformis. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 1994;10:224–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00360893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandrashekar MA, Soumya Pai K, Ramesh SKC, Geetha N, Puttaraju HR, Raju NS. Biodegradation of organophosphorous pesticide, Chlorpyrifos by soil bacterium - Bacillus Megaterium Rc 88. Asian J Microbiol Biotechnol Environ Sci. 2017;19:146–152. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sunil KCR, Swati K, Bhavya G, et al. Streptomyces flavomacrosporus, A multi-metal tolerant potential bioremediation candidate isolated from paddy field irrigated with industrial effluents. Int J Life Sci. 2015;3:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhavya G, Kumar C-RS, Swati K, Geetha N. In Search of Industrial Clean-up Clients; Evaluation of Heavy Metal Tolerability of Rhizospheric Trichoderma. Int J Innov Sci Eng Technol. 2015;2:948–952. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlos FS, dos Santos BL, Andreazza R, et al. Irrigation of paddy soil with industrial landfill leachate: impacts in rice productivity, plant nutrition, and chemical characteristics of soil. Paddy Water Environ. 2017;15:133–144. doi: 10.1007/s10333-016-0535-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porwal S, Lal S, Cheema S, Kalia VC. Phylogeny in aid of the present and novel microbial lineages: diversity in Bacillus. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawasaki K, Mochizuki a, Matsushita M, et al. Modeling spatio-temporal patterns generated by Bacillus subtilis. J Theor Biol. 1997;188:177–185. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1997.0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ben-Jacob E, Cohen I, Gutnick DL. Cooperative organization of bacterial colonies: from genotype to morphotype. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:779–806. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West SA, Cooper GA. Division of labour in microorganisms: an evolutionary perspective. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:716. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim W, Levy SB, Foster KR. Rapid radiation in bacteria leads to a division of labour. Nat Commun. 2008;354:1395–1405. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butler MT, Wang Q, Harshey RM. Cell density and mobility protect swarming bacteria against antibiotics. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:3776–3781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910934107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar C-RS, Bhavya G, Kini R, Geetha N. Practiced gram negative bacteria from dyeing industry effluents snub metal toxicity to survive. J Appl Biol Biotechnol Vol. 2017;5:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arora G, Sajid A, Kalia VC (2017) Drug resistance in bacteria, fungi, malaria, and cancer. Springer, Switzerland. 10.1007/978-3-319-48683-3

- 26.Kalia VC (2014) Microbes, antimicrobials and resistance: the battle goes on. Indian J Microbiol 54:1–2. 10.1007/s12088-013-0443-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Patel SKS, Kim J-H, Kalia VC, Lee J-K. Antimicrobial activity of amino-derivatized cationic polysaccharides. Indian J Microbiol. 2019;59:96–99. doi: 10.1007/s12088-018-0764-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalia VC, Rani A, Lal S, et al. Combing databases reveals potential antibiotic producers. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2007;2:211–224. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]