Abstract

Background:

A variety of complications after injection of nonpermanent fillers for facial rejuvenation have been reported so far. However, to date, the overall complication rate is still a matter of debate. The aim of this study was to perform a systematic review of literature to assess the type and severity of associated complications following injections in different anatomical regions of the face.

Methods:

The entire PubMed/Medline database was screened to identify case reports and clinical studies describing complications that have occurred after injection of nonpermanent fillers in the face. These complications have been reviewed and analyzed according to their occurrence in different anatomical regions of the face.

Results:

Forty-six articles including a total of 164 patients reported on a total of 436 complications during the time period between January 2003 and February 2020. The majority of the complications were reported after injections to the nose and the nasolabial fold (n = 230), the forehead and the eyebrows (n = 53), and the glabellar region (n = 36). Out of 436 complications, 163 have been classified as severe or permanent including skin necrosis (n = 46), loss of vision (n = 35), or encephalitis (n = 1), whereas 273 complications were classified as mild or transient, such as local edema (n = 74), skin erythema (n = 69), and filler migration (n = 2). The most severe complications were observed in treatments of nose, glabella, and forehead.

Conclusions:

Nonpermanent facial fillers are associated with rare but potentially severe complications. Severity and impact of complications depend on the anatomical region of the face and eventually require profound knowledge of facial anatomy.

INTRODUCTION

Nonpermanent fillers, including hyaluronic acid (HA) were officially introduced on the market in 1996 in Europe and 3 years later in the United States. Ever since, a massive diffusion has been observed to treat soft-tissue volume loss. One of the reasons for this success is, among other things, a relatively easy access to the substance. Furthermore, nonpermanent fillers are relatively safe in terms of local immunological reaction, and are absorbable and presumably simple to administer.

HA is as polysaccharide naturally present in the human body as a component of the skin, the central nervous system, and blood vessels. It represents the ideal filler to counteract consequences of aging, including dermal atrophy, wrinkle formation, and volume loss.1 HA acts through stabilization, lubrication, hydration, and increase of the viscoelastic properties of the extracellular matrix.2 Administered alone or in combination with other substances, it is considered to be the “gold standard” for rejuvenation treatments of the upper third of the face.3

Calcium hydroxyapatite (CaHa) is another nonpermanent filler used for aesthetic purposes in the face. CaHa is composed of millimetric spheres that are suspended in a carboxymethylcellulose carrier that stimulates the fibroblast’s activity and eventually induces the formation of new collagen and elastin fibers. CaHa is thicker than HA and has a longer lasting effect, due to its viscoelastic characteristics in the nondiluted form. Therefore, CaHa is considered a valuable alternative to HA to offer nonsurgical treatments that include contour improvement and volume increase of the aged face.3,4

Despite the benefits of these nonpermanent fillers, the overall rate of adverse effects or complications of the filler itself or its administration seems to be low. Nevertheless, recently, there is an increasing concern regarding presumably rare but serious complications.5–8 So far, no studies have investigated the overall complication rate following the use of nonpermanent fillers in different areas of the face. Although a variety of articles refer to the complications of permanent fillers for cosmetic purposes, there is currently a lack of well-structured evidence reporting on the complications of nonpermanent fillers. The aim of this study was to investigate the existing literature reporting on complications following the use of nonpermanent fillers injected to the face and ideally propose strategies to minimize the risk of recurrence and severity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

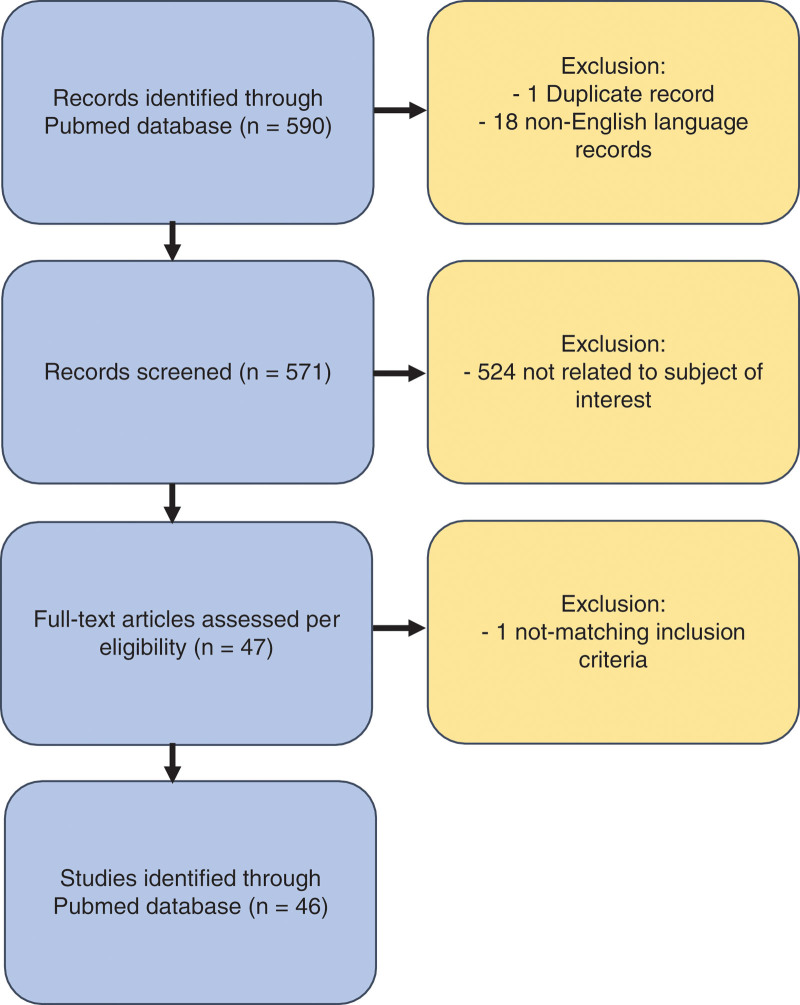

A systematic literature review has been conducted using the PubMed/Medline database. The search included publications from January 2003 to February 2020. The following search algorithm has been applied: [(Filler) AND (Facial) AND (Complications)] without restrictions on time of publication. Clinical studies of all types have been included, such as clinical trials, prospective case series, retrospective reviews, and case reports with a full text available in English, independent from their level of evidence. Two independent investigators (D.B. and C.M.O.) screened manually and selected the articles only if the complication occurred after the use of a nonpermanent filler (ie, resorbable and biodegradable) for cosmetic purposes in the face of healthy patients. A third reviewer (Y.H.) has been involved in the case of discrepancy while interpreting the literature. After initial selection, the authors excluded articles describing the use of a permanent filler, autologous fat transfer or grafting (“lipofilling”), literature reviews, and duplicate nonoriginal material (details are listed in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of search strategy.

Each identified article has been listed as follows: name of first author, year of publication, study design, number of patients included, gender, age, geographic origin of the study, type of filler, area of injection, timing of onset of the complication following injection, type and treatment of complication (conservative/surgical), outcome, and eventually level of evidence (LoE) of the article according to the Oxford level of evidence scale.9–11 Although the majority of the reviews classified the complications according to their time of onset (early versus late onset), the authors decided to further categorize the complications as mild (transient) and severe (permanent).12 Immediate pain, bleeding, and isolated bruising were not counted as complications in this article because of probable underreporting due to their frequency after cosmetic injective treatments to the face.

RESULTS

Five hundred ninety articles could be identified in the PubMed database, of which 46 matched the above-mentioned search criteria: 37 case reports and nine retrospective studies have been published during the time period evaluated. The LoE of the identified articles were either 5 or 4 (case reports/case series without the use of comparison or a control group). These 46 articles reported a total of 164 patients having complications after injection of nonpermanent fillers to the face. Almost all patients were female (96.9%) with the exception of five males (3.1%). The mean age of patients was 41.4 years (range 20–72 years). Details are listed in Table 1. A total of 436 complications have been described in these patients, 63% (n = 273) of which have been classified as mild (transient) and 37% (n = 163) as severe (permanent), as shown in Tables 2 and 3.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Studies with Complications of Facial Fillers

| Author (First Listed), Year | Study Design | No. of Patients (Gender) | Age (Mean) | Geographic Location | Type of Filler | Area of Injection | Timing of Onset | Type of Complication | Therapy (Medical/Surgical) | Outcome | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hönig et al, 20032 | Case report | 1 (F) | 54 | Germany | HA | Nasolabial fold | Several days | Redness and intermittent swelling of the nasolabial folds. Development of palpable and painful erythematous nodular papule-cystic which evolved into severe bilateral abscesses | Drainage of the abscesses; excision of the recurrences of granulomatous allergic tissue reactions; surgical correction of the nasolabial fold | Complete healing without recurrences after surgery | 5 |

| Arron and Neuhaus 200713 | Case report | 1 (F) | 59 | United States | HA (Matridur and Matrigel) | Glabella, nasolabial fold, lips | 2 d; 5 d hospitalization | Facial edema, erythema of the glabella and nasolabial folds and beyond | Azathioprine and methylprednisolone. The patient refused the treatment with hyaluronidase | Signs completely resolved by 1 y after the injections | 5 |

| Sires et al, 200814 | Case report | 1 (F) | 57 | United States | CaHa (Radiesse) | Glabella, nasolabial fold | Immediate | Herpetic appearing skin lesions, tenderness and tingling along with redness and bumps. Vesicles along the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve | Ciprofloxacin, after 3 d worsening of the lesions. Acyclovir 800 mg 5 times a day for 10 d | After 1-month, complete resolution of the lesions | 5 |

| Kwon et al, 201315 | Case report | 1 (F) | 20 | Korea | HA | Nasal dorsum | Immediate | Ischemic oculomotor nerve palsy and glabellar skin necrosis. Blepharoptosis, strabismus. Intermittent diplopia | Aspirin, nicegorlin, corticosteroids, Epidermal growth factor spray, sodium hyaluronate gel, antibacterial ointment | 6 mo from the event full recovery | 5 |

| Oh et al, 201416 | Case report | 1 (F) | 33 | Korea | HA | Glabella, asal ala | Immediate | Vision loss in the right eye without light perception | 700 units of hyaluronidase and 20,000 units of urokinase into the ophthalmic artery. Next, 800 units of hyaluronidase were infused into the branches of the right ECA | No visual improvement at 1-mo control | 5 |

| Tracy et al, 20144 | Case report | 1 (F) | 41 | United States | CaHa | Nasolabial fold | 1–11 d | Swelling and skin changes to her left alar crease. Later on, necrosis of the injected area due to a local herpes zoster reactivation | Valaciclovir; daily local wound care regimen with daily wound debridement | Acceptable aesthetic result with minimal residual scar | 5 |

| Rongioletti et al, 201417 | Case report | 3 (F) | 61.3 | Italy | HA (n = 3) | Glabella, cheeks, nasolabial fold, perioral (n = 2); Lips (n = 1) | Few months | Firm, nodular swellings involving the facial areas of the injection | Minocycline 200 mg (3 mo) (n = 1). Excision of the granulomas (n = 2) | Slight (n = 1) to good (n = 2) aesthetic result | 4 |

| Hsieh et al, 201518 | Case report | 2 (F) | 40 | Taiwan | CaHa | Glabellar area (n = 2) | Immediate | Central retinal artery occlusion, ophthalmoplegia, glabellar skin necrosis, monolateral blindness (n = 1) Bilateral anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and chorioretinal vascular occlusion over the left eye with visual impairment and visual field defect (n = 1) |

Anterior chamber paracentesis, timolol, acetazolamide, oral antiplatelet, topical betamethasone(n = 1) Hyperbaric oxygen therapy, systemic low-dose steroids, antiaggregant, topical and oral antiglaucomatous agents (n = 1) |

Blindness left eye at the control (n = 1) Altitudinal visual field defects in both eyes and generalized depression in the visual field of the left eye (n = 1) |

4 |

| Sun et al, 201519 | Retrospective review | 20 (F, n = 19; M, n = 1) | 29 | China | HA | Nasal dorsum (n = 15); nasolabial fold (n = 6) | 1 d | Erythema, swelling, skin necrosis (n = 20) | Injection of ovine testicular hyaluronidase in the soft tissues, antibiotics, tanshinone, papaverine, topical magnesium sulphate, infrared irradiation, hyperbaric oxygen | After treatment, 65% (n = 13) recovered fully and the remaining 35% (n = 7) developed full skin necrosis and scar formation | 4 |

| Chou et al, 201520 | Case report | 1 (F) | 35 | Taiwan | CaHa (Radiesse) | Nasal dorsum, nasal tip | Immediate | Choroid vascular occlusion leading to left ischemic optic neuropathy, blurred vision and glabellar skin necrosis | Alprostadil, dextran to improve blood supply; hyperbaric oxygen therapy (10×) | Visual acuity to 6/60 on the left eye after 1 mo | 5 |

| Schuster, 201521 | Retrospective review | 7 (F, n = 6; M, n = 1) | Not reported | Germany | CaHa (n = 7) | Nasal dorsum (n = 6); nasal tip (n = 1) | Not reported | Filler dislocation (n = 1), visible hematoma (n = 2), subcutaneous nodules persisting for up to 8 wks after injection (n = 1), painless red nasal tip (n = 1), local infection at the injection site (n = 1), subdermal abscess with skin necrosis (n = 1) | Topical corticosteroids, systemic antibiotics (n = 3), local antibiotic ointment (n = 1), incision of the abscess (n = 1) | Complete resolution of the symptoms (n = 6); no information on the follow-up (n = 1). | 4 |

| Andre and Haneke, 201622 | Case report | 6 (F) | 37.5 | France, Switzerland | HA (n = 6) (Restylane) | Nasolabial fold (n = 4); nasal tip (n = 1); lips (n = 1) | Immediate | Nicolau Syndrome (immediate pain, livedoid pattern, scabs and skin necrosis) | Hyaluronidase, aspirin, topical antiseptic (n = 6) | Full recovery in few weeks | 4 |

| Fan et al, 201623 | Case report | 2 (F) | 26 | China | HA | Temporal region, lacrimal through, cheeks, nasal dorsum, chin (n = 1); forehead (n = 1) | 2–3 d | Anaphylactic reaction with bilateral edema on upper eyelids and itchy milia pimples around center of the face (n = 1); pronounced redness, ulcer, and pustules in the glabellar region (n = 1) | Loratadine 10 mg tablets to take orally once a day, topical tacrolimus ointment (0.03%) for 5 d (n = 1); dexamethasone 20 mg intravenously, hyperbaric oxygen once a day for 6 sessions, amoxicillin capsules 0.5g 3 times a day, aescuven forte tablets 300 mg twice a day, topical recombinant human epidermal growth factor gel on the lesions for 10 d | Complete resolution in both cases at the control | 4 |

| Kang et al, 201624 | Case report | 1 (F) | 46 | Korea | HA | Glabella, forehead, nasal dorsum | 2 d | Inflammatory symptoms with redness, swelling, numerous pustules, and dark regional necrosis | Hyaluronidase, oral antibiotics, prednisolone 15mg, debridement and injected PRP intradermally and topically with a dressing. After 2 wks additional PRP with topical fucidic acid, carbon dioxide laser for the scar | On the 10th day, the wound was completely re-epithelialized with residual erythema and a depressed scar. After 10 mo the scar had improved with satisfactory results and only a slightly noticeable scar remained | 5 |

| Kim et al, 201622 | Case report | 4 (F) | Not reported | Korea | HA | Glabella; nasolabial fold (n = 4) | Immediate | Unilateral ophthalmoplegia with visual loss, total paralysis of infraduction and adduction (n = 4). Palsy of the superior oblique (n = 3). Limitations in supraduction (n = 2). Limitations in abduction (n = 1) | Intraarterial thrombolysis using hyaluronidase (n = 1) | At 8 mo control all the patients remained without light perception in the involved eye | 4 |

| Cohen et al, 201625 | Case report | 1 (F) | 24 | Israel | CaHa | Nasal dorsum | Immediate | Sudden ocular pain and lowering of visual acuity. At the examination marked periorbital edema and hematoma, ptosis, ocular movements limitation, infero-temporal branch retinal artery occlusion and multiple choroidal emboli | Enoxaparin sodium 60 mg 2xdie for 2 d; acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg/die; amoxicillin/clavulanate 875 mg 2xdie for 7 d and prednisone 60 mg/die gradually tapered down; topical antibiotics ofloxacin 0.3% eye drops and mupirocin ointment to the nose bridge and forehead area for 14 d | 18 mo visual acuity was 20/60, visual field examination was deteriorated in comparison with normal exam | 5 |

| Or et al, 201726 | Retrospective review | 7 (F) | 48.2 | United States | HA (n = 2); CaHa (n = 4) | Lower eyelid region (n = 7) | 12 mo (average) | In the lower eyelid comparison of a xanthelasma-like appear lesions: yellowish, flat, and soft plaques | Steroid injections, 5FU injections, ablative or fractionated CO2 laser, direct excision (n = 5); no treatment (n = 2) | Complete healing | 4 |

| Yu et al, 20171 | Case report | 1 (F) | 54 | United Kingdom | HA (Restylane and Teosyal) | Brow region | 21 mo | Chronic bilateral pitting upper eyelid edema lasting 6 y after multiples injections | Hyaluronidase 120 units, was injected into the subcutaneous brows | Healing within 2 d, 2 y-control without recurrences | 5 |

| Zhu et al, 201727 | Retrospective review | 4 (F) | 27 | China | HA | Nasal dorsum (n = 3); forehead (n = 1) | Immediate | Vision loss (n = 3); blurred vision (n = 1); blepharoptosis (n = 4); ophthalmoplegia with oculomotor nerve palsy (n = 2) | One or two retrobulbar injections of hyaluronidase (1500–3000 U) (n = 4); corticosteroids (n = 3) | No improvement after treatment in all patients | 4 |

| Lee et al, 201728 | Case report | 1 (F) | 25 | Korea | HA (Bellast) | Temporal area | Immediate | Ecchymosis on the left nasal ridge, ptosis of the left eye, a conjunctival injection, a dilated pupil in the left eye, diplopia in all directions | Systemic steroid injections (2 wks), broad-spectrum antibiotics (1 wk). The skin lesion was dressed twice per day with an epidermal growth factor spray and antibacterial ointment |

6 mo control showed improvement of the skin lesion with minimal residual scarring and persistent diplopia | 5 |

| Dagi Glass et al, 201729 | Case report | 1 (F) | 64 | United States | CaHa | Temples, cheeks, forehead, chin | Immediate | Horizontal diplopia and right upper eyelid ptosis | Oral steroids | At 2-mo follow-up, there was moderate clinical improvement | 5 |

| Kim et al, 201730 | Case report | 1 (F) | 41 | Korea | HA | Nasolabial fold | Immediate | Erythema, swelling, tenderness, multiple vesicle formations on the left side of face, skin necrosis in the area where she had a facial injury 8 y before, which potentially compromised her vascular network | Hyaluronidase, aspirin, ciprofloxacin and clarithromycin (10 d), and local bacitracin (16 d) Surgical remove of the wound 13 d after injection |

4 mo-control showed minimal asymmetry of nostrils lied to minimal skin defect in the left nostril and the alar base | 5 |

| Shin et al, 201731 | Case report | 1 (F) | 58 | Korea | HA | Cheeks, chin | 1 mo | Erythematous inflammatory nodules, colture positive to Aspergillus | Incision, drainage of the lesion, colture of the pus Voriconazole injection |

Complete healing | 5 |

| Vu et al, 201832 | Case report | 1 (F) | 51 | United States | CaHa | Glabella, nasal dorsum | Immediate – 1 h | Nausea, vomiting, headache, loss of vision of the right eye; necrosis of skin of the forehead and glabella | Retrobulbar hyaluronidase injection, ocular massage, prednisone and aspirin | One day later, visual acuity improved to light perception that remained stable at 3 mo; glabellar and forehead skin presented erythematous, depressed scars | 5 |

| Vidič and Bartenjev, 201833 | Case report | 1 (F) | 50 | Slovenia | HA | Upper lip, nasal dorsum, glabella, marionettes | 3 d | Erythematous, livedoid rash at the site of the injection in the glabellar region and from the nasal root to the scalp and left upper eyelid | Antibiotic (azithromycin 500 mg) for 6d p.o., corticosteroid (methylprednisolone 32 mg) p.o. for 5 d | 1 mo-control showed complete healing | 5 |

| Khoo et al, 201834 | Case report | 1 (F) | 27 | Malaysia | HA | Nasolabial fold | 1–5 wks | Fever, lethargy, headache. At 5 wks developing of encephalitis positive to HST-1 with altered mental state and seizures | Intubation for the status epilepticus, phenytoin 15 mg/kg, ceftriaxone 2 g and acyclovir 500 mg. After the diagnosis of HSVT-1, acyclovir IV (3 wks) and methylprednisolone (5 d). Levetiracetam for the seizures |

After 2 mo postencephalitic syndrome (hypomania, self-injury, hyperphagia), transfer in psychiatry department. 3 mo follow-up showed poor cognitive functions | 5 |

| Bae et al, 201835 | Case report | 1 (F) | 29 | Korea | HA (Elarvie) | Nasal tip | Immediate – 3 d | Severe pain, dizziness, and blurred vision. Visual disturbance and extraocular movements limitation. Later comparison of violaceous necrotic skin lesions on right periocular and glabellar area | Hyaluronidase subcutaneously, systemic steroid (methylprednisolone), vasodilator (nitroglycerin, alprostadil), prophylactic antibiotics, and daily dressing with LLLT (low-level laser therapy | After 2 wks, skin necrosis and ocular movement are gradually recovered, confirmed at 1-y control | 5 |

| Robati et al, 201836 | Retrospective review | 7 (F) | 33 | Iran | HA | Lips, nasolabial fold (n = 6); nasal dorsum (n = 1) | Immediate – 3 d | Vascular complications leading to severe pain, tenderness, firm swelling, cyanotic discoloration, pustule formation, necrosis | Hyaluronidase (100 to 300 UI) | Reversion of the symptoms | 4 |

| Alshaer et al, 201837 | Case report | 1 (F) | 56 | Saudi Arabia | HA | Cheeks | 17 y | Painful swelling of the right cheek after a failed trial of filler evacuation and intralesional corticosteroid injection. Isolation of Brucella cells at micro bacterial examination | Incision and drainage, colture, cefazolin (1 g every 8 h for 8 d) IV and paracetamol (1 g every 6 h for 2 d). Second incision and drainage, doxycycline 100 mg tablets (every 12 h for 42 d) and streptomycin 1 g IM injection for 14 d | All the symptoms resolved | 5 |

| Fang et al, 201838 | Case report | 1 (F) | 31 | Indonesia | HA (Juvederm) | Chin | Immediate – 2 d | Blanching of skin on the right side of chin and upper neck areas with severe pain in all the chin area and during the swallowing process. Later comparison of livedo reticularis/skin around the blanched skin patch extending from the mental crease to the upper cervical area. Later the development of multiple small pustules | Hyaluronidase 1000 U in the injected area and 1cm above the skin reaction immediately and after 1 h. Oral cefixime 200 mg (2/24H) and acetylsalicylic acid 75 mg (1/24H) and topical mupirocin ointment | After 4 wks all symptoms were gone | 5 |

| Henderson et al, 201839 | Case report | 1 (F) | 37 | United States | HA (Juvederm) | Temples | Immediate | Hearing loss in the left ear without vestibular symptoms, blanching over the left side of the face, severe pain | Immediate hyaluronidase, topical nitro paste, warm compresses. After 9 h enoxaparin, aspirin, dexamethasone 10 mg IV, piperacillin/tazobactam, and intradermal 1% lidocaine (0.1 ml per site) After 15 h hyperbaric oxygen treatments (6 in total, twice a day, the initial 2 at 3.0 atmospheres absolute for 90 min followed by 4 treatments at 2.4 ATA × 90 min) Sessions of PRP for residual erythema after discharge |

After 3 d, hearing back to the baseline subjectively, no hearing test were performed. At 1-y follow-up, complete resolution of the skin lesions |

5 |

| Thanasarnaksorn et al, 201840 | Case report | 6 (F, n = 5; M, n = 1) | 35.5 | Thailand, United States | HA | Nose (n = 4), forehead (n = 1); temple (n = 1) | Immediate | Ophthalmic artery occlusion (n = 2); Central retinal artery occlusion (n = 2) with nerve III palsy (n = 1); right peripheral retinal ischemia and choroidal ischemia (n = 1) | Hyaluronidase, methylprednisolone, antiplatelet drugs, oral antibiotic, antiepileptic drug, topical steroid eye drop, topical antibiotic eye drop, hyperbaric oxygen, anterior chamber paracentesis | Vision loss in the affected eye (n = 2); full recovery (n = 4) | 4 |

| Han et al, 201841 | Case report | 1 (F) | 42 | China | HA | Forehead | 2 d | Necrotic circular skin lesion of approximately 1 cm in the glabellar region with a thin overlaying scab. Persistent tenderness and pain extending from the right glabella to the top of the forehead | Combination of recombinant bovine basic fibroblast growth factor gel and antibiotic ointment | At 14 d-control the wound was re-epithelialized with residual erythema and a depressed scar | 5 |

| Wang et al, 201842 | Case report | 2 (F) | 33 | China | HA | Chin (n = 2) | Immediate – 1 d | Paleness evolved in red-black discoloration with formation of blisters in the anterior region of the chin and necrosis (n = 2) Numbness in the right side of the tongue, neck pain, and headache (n = 1) |

Hyaluronidase, hot compresses and a recombinant human epidermal growth factor gel | Skin necrosis gradually evolved in a superficial ulcer (n = 1) At 9 d-control mild atrophy and paraesthesia of the affected side of the tongue (n = 1) |

4 |

| Doerfler and Hanke, 201943 | Case report | 1 (F) | 34 | United States | HA (Juvederm) | Nasolabial fold | Few hours | Few hours later the injection, discoloration of the skin and tenderness of the nasolabial fold; the day after erythematous plaque with overlying pustules evolving in skin necrosis | Hyaluronidase (300 U) warm compresses, aspirin 80 mg, nitroglycerin ointment, cephalexin 500 mg, valaciclovir 1 g, methylprednisolone, mupirocin ointment, petrolatum | Excellent 7-mo outcome | 5 |

| Chauhan and Singh, 201944 | Case report | 1 (M) | 50 | India | HA | Cheeks, glabella, nasolabial | 2 d | Necrosed micro vesicles in the infraorbital artery territory with signs of impending skin necrosis and redness (livedo reticularis) extending from infraorbital region up to the nasolabial fold | Hyaluronidase (2000 U divided in 4 doses in 1 d) | At the end of 3 mo skin had completely healed without any residual scarring or pigmentation | 5 |

| Zhang et al, 201945 | Retrospective review | 3 (F) | 30 | China | HA | Nasal dorsum (n = 2); glabella (n = 1) | Immediate | Complete visual field loss of the left eye and ophthalmodynia (n = 1); visual defect on the upper side of the right eye, diplopia and limitation of medial motion (n = 1); complete visual field loss and ptosis of the right eye (n = 1) | Hyaluronidase injection in the sites of the filler injections; glucocorticoid; anticoagulant; hyperbaric oxygen (n = 3); hyaluronidase (retrobulbar injection) (n = 1) | No improvement in the visual acuity | 4 |

| Marusza et al, 201946 | Retrospective review | 22 (F) | 47.3 | Poland | HA | Nasolabial fold (n = 7); tear through (n = 6); cheeks (n = 5); corners of mouth (n = 4) | 1–18 mo | Symptoms of late bacterial infection) as induration, swelling, erythema, pain, and loss of function | Netsvyetayeva (M&N) scheme of comprehensive treatment (n = 17): Puncturing the lesion with an 18 G needle, followed by drainage of pus and fermented cross-linked HA twice a week, until complete resolution; Local administration of hyaluronidase directly onto the lesion twice a week for 14–21 d or until complete resolution of swelling and nodules; Moxioxacin 2400 mg and clarithromycin 2500 mg per os for 14–21 d. Probiotic formulation during the antibiotic therapy |

Resolution of local symptoms was achieved after treatment lasting 14–21 d, with no recurrences at 2-mo control After the 2-mo period, all patients underwent remedial therapy with cross-linked HA, with no infectious complications at the site of administration within the subsequent 2 y (n = 17) |

4 |

| Oh et al, 201947 | Case report | 1 (F) | 48 | United States | CaHa (Radiesse) | Glabellar region | Immediate | Vision loss: no light perception OD, and 20/20 OS | No feasible therapy was identified to restore visual function | 9-mo follow-up: no light perception in the right eye with ischemia and fibrosis on examination of the retina | 5 |

| Ciancio et al, 201948 | Case report | 2 (F) | 40.5 | Italy | HA | Nasolabial fold (n = 2) | 3 d | Skin suffering with erythematous and blister formation | Early infiltration of hyaluronidase in the treated areas (40 IU per cm2); acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg/24 h (10 d); prednisone 25 mg/24 h (4 d); levofloxacin 500 mg/24 h (4 d); topical cream with nitric oxide 2 times a day and compresses with gauze and warm | Good outcome; in both cases necrotic complications were avoided | 4 |

| Turkmani et al, 201949 | Retrospective review | 14 (F) | 40.5 | Saudi Arabia | HA (Juvederm, Teosyal, Belotero, Surgiderm, Restylane, Inamed) | Tear through (n = 8), lips (n = 3), cheeks (n = 9) | 2–10 mo | Localized redness and firm, painful swelling at the sites of previously injected fillers. Reactions started 3–5 d after patients had experienced influenza-like illness (fever, headache, sore throat, cough, and fatigue) | Oral prednisolone 20–30 mg or methylprednisolone 16–24 mg daily for 5 d, followed by tempering of the dose for another 5 d. Treatment with local hyaluronidase was needed in 4 patients after 2 wks | Complete resolutions of symptoms | 4 |

| Uittenbogaard et al, 201950 | Case report | 1 (F) | 46 | The Netherlands | CaHa | Temporal area | Immediate – 2 d | Dermal ischemia | Hyaluronidase, warm compresses, sildenafil, prednisolone, nifedipine for a week. Hyperbaric therapy (10×) | Excellent cosmetic outcome at 6-mo follow-up | 5 |

| Khalil et al, 202051 | Case report | 1 (F) | 54 | United States | HA | Brows, glabella | 2 mo | Edema of the upper eyelids, xerophthalmia, and dryness of her nasal mucous membranes | Hyaluronidase (20 U) were injected into the areas of filler placement immediately and after 3 wks (40U) | Almost instantaneous resolution of the edema | 5 |

| Kaczorowski et al, 202052 | Case report | 1 (F) | 52 | Poland | HA | Nasolabial fold, lips | 2 y | Solid, painless mass in the right buccal area interpreted as a delayed granulomatous reaction to HA associated with its migration from the injection site. Differential diagnosis with a malignancy was made | Excision, layer-by-layer suture with a temporary gauze compression was applied for 5 d | Good results; correction with lipotransfer was planned | 5 |

| Halepas et al, 202053 | Case report | 1 (F) | 52 | United States | HA | Marionettes lines, nasolabial folds | 12 h | Erythematous swelling of the facial skin on the left side in the area lateral and inferior to the lower lip | Warm compresses, 600 U of hyaluronidase, aspirin 325 mg, nitroglycerin paste | Day 9 control did not show ocular or facial disturbances | 5 |

| Zhang et al, 202054 | Retrospective review | 24 (F, n = 23; M, n = 1) | 26 | China | HA | Nasal dorsum (n = 12); temporal area (n = 1); forehead (n = 10); glabella (n = 1) | Immediate | Severe decrease in visual acuity or blindness combined with weakness in opening of their eyes, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, severe headache or ocular pain, and skin numbness, ptosis (n = 24); no light perception (n = 19) | Thrombolytic agents, hyaluronidase or hyaluronidase with urokinase were slowly injected into the ophthalmic artery, mechanical recanalization with micro guidewire (n = 24). Retrobulbar injection of tobramycin 20 mg and dexamethasone 2.5 mg; prednisolone acetate ophthalmic suspension eye drops, levofloxacin, sodium hyaluronate eye drops, and deproteinized calf blood extract eye gel | Only 42% (n = 10) of patients had improvements to visual acuity. The best treatment protocol was the hyaluronidase combined with urokinase. Facial skin necrosis restored to nearly normal appearance (n = 24). | 4 |

| Total articles: 46 | Case report: 37 Retrospective review: 9 |

Total patients: 164 (F, n = 159; M, n = 5) | Mean age: 41.4 |

F, female patients; IM, intramuscle; M, male patients; IV, intravenous; p.o., per os.

TABLE 2.

Rates of Mild or Transient Complications

| Mild or Transient Complications | N = 273 |

|---|---|

| Swelling and edema | 74 |

| Erythema | 69 |

| Headache | 26 |

| Skin paraesthesia | 24 |

| Local infection | 23 |

| Pustules/vesicles | 16 |

| Livedoid pattern | 9 |

| Xantelasma-like lesion | 7 |

| Nodules/granulomas | 7 |

| Scabs | 6 |

| Hematoma | 3 |

| Ulcer | 2 |

| Filler dislocation | 2 |

| Abscess | 2 |

| Hearing loss | 1 |

| Milia pimples | 1 |

| Xerophtalmia | 1 |

TABLE 3.

Rates of Severe or Permanent Complications

| Severe or Permanent Complications | N = 163 |

|---|---|

| Skin necrosis | 46 |

| Vision loss | 35 |

| Blepharoptosis | 31 |

| Decreased visual acuity | 25 |

| Ophthalmoplegia | 15 |

| Visual field defect | 4 |

| Blurred vision | 3 |

| Diplopia | 2 |

| Encephalitis | 1 |

| Paraesthesia of the tongue | 1 |

Hereinafter, the complications are briefly characterized according to their occurrence in the different facial areas. Details are listed in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Complication Rates (Mild or Transient, Severe or Permanent) per Anatomic Area

| Area | n Tot | % Tot | n Mild | % Mild | n Severe | % Severe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nose and nasolabial fold | 230 | 52.7 | 163 | 70.8 | 67 | 29.2 |

| Forehead and eyebrows | 53 | 12.1 | 39 | 73.6 | 14 | 26.4 |

| Glabellar region | 36 | 8.2 | 15 | 41.6 | 21 | 58.4 |

| Lower eyelid and tear trough | 31 | 7.1 | 31 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Cheeks | 31 | 7.1 | 31 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Lips | 27 | 6.2 | 27 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Temporal region | 16 | 3.6 | 8 | 50 | 8 | 50 |

| Perioral and marionette lines | 12 | 2.7 | 12 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Chin region | 11 | 2.5 | 7 | 63.6 | 4 | 36.4 |

Forehead and eyebrows: 12% of all complications (n = 53) occurred in this area, 74% (n = 39) of which were classified as mild or transient and 26% (n = 14) as severe or permanent, including occlusion of the retinal artery with no improvement in vision acuity after retrobulbar injection of hyaluronidase and palsy of the oculomotor nerve that partially responded to combined systemic therapy with hyaluronidase, methylprednisolone and hyperbaric oxygen.40 HA-based fillers were used in 94.4% (n = 50) of the cases, whereas CaHa was used in only 5.6% (n = 3).

Temporal region: 16 complications were reported after local use of HA (71%; n = 11) or CaHa (29%; n = 5%). Half of the complications were classified as severe or permanent (n = 8 each), the most serious of which included one case of dermal ischemia and one case of diplopia.28 Notably, one case of immediate unilateral hearing loss was reported among the mild and transient complications.39 Treatment included injection of hyaluronidase, hyperbaric oxygen, as well as systemic administration of steroids and broad-spectrum antibiotics.28,39

Glabellar region: 8% (n = 36) of all complications were reported in the area of the glabella, 42% (n = 15) of which were classified as mild or transient, including skin erythema of the glabella (n = 4). Fifty-eight percent (n = 21) were classified as severe, including vision loss due to arterial occlusion (36%, n = 13), palsy of the motor nerves of the eyes (17%, n = 6), and skin necrosis (11%, n = 4).18,24,44 Complications were observed with both local injection of HA (72.2%) and CaHa (17.8%). Specific treatment of complications involving the eye included direct injection of hyaluronidase and urokinase in the affected artery and in the retrobulbar space, retrobulbar injection of corticosteroids and antibiotics (tobramycin), as well as paracentesis of the anterior chamber, and eventually hyperbaric oxygen therapy.18

Nose and nasolabial fold: 53% (n = 230) of all complications occurred in this area. It has to be noted that injections of nonpermanent fillers to the nasal dorsum and the nasolabial fold were associated with the highest rate of complications, whereas only a few reactions were identified following injections to the nasal tip and nasal ala. The severity of these complications ranged from mild in 71% (n = 163) to severe in 29% (n = 67) of all cases. Transient reactions included edema in 15% (n = 35), vesicle and blister formation in 5% (n = 12), subcutaneous nodules in 3% (n = 8), and filler dislocation in 0.5% (n = 1).2,4,13,14,19,23,24,30,46,53 In contrast, severe complications were described as follows: skin necrosis in 13% (n = 31), immediate vision loss in 2% (n = 4),16,27 oculomotor nerve palsy in 1% (n = 3), ischemic optic neuropathy in 0.5% (n = 1), and positivity to herpes simplex type 1 encephalitis with altered mental status and seizures in 0.5% (n = 1). Complications occurred both after injection of HA (87.5%) and CaHa (12.5%). Complications following HA injection were treated using hyaluronidase in different modes of administration: local injection into the affected soft tissues; injection into the feeding artery of the affected area and direct injection into the retrobulbar space in the case of ophthalmological complications.4,15,19,20,24,30,36,44,55 In the case of established thromboembolic events affecting a branch of the ophthalmic artery, the slow injection of a combination of hyaluronidase and urokinase into the affected artery, eventually followed by mechanical recanalization with a microguidewire, showed partial improvement of visual acuity.54 Furthermore, hyperbaric oxygen was considered as an effective treatment in some cases.19,20,23,40,45

Lower eyelid and tear trough: All complications that occurred in this area (n = 31) were mild or transient and developed after injection of HA-based fillers. They included formation of a xanthelasma-like lesion (23%, n = 7), pain and erythema-formation (19%, n = 6), and itchy pustules in the injected area (3%, n = 1).23 Complete healing was observed after hyaluronidase injected into the lesion in combination with systemic steroids or direct excision.26

Cheeks: Similar to the eyelid and tear through area in the cheek region, all 31 complications were classified as mild or transient. The majority of the complications were redness and firm swelling in the injected region (55%; n = 17).17,37,46,49 Notably, one case each of itchy pustules and inflammatory nodules positive to Aspergillus successfully treated with systemic voriconazole were also reported.31 The complications occurred after injection of HA-based fillers and CaHa in 95% and 5%, respectively.

Lips: 6% (n = 27) of all complications described occurred in this area. They were represented by severe pain, tenderness, discoloration of the skin, and incipient ischemic signs, yet fully recovered with local injection of hyaluronidase (n = 6).36 All these patients underwent injection of HA-based fillers. No severe complication occurred in the lip area.56

Perioral region including marionette lines: 12 (100%) mild or transient complications were noted using exclusively HA-based fillers. Notably, this included among other things, four cases (33%) of late bacterial infection treated with hyaluronidase and antibiotics (moxifloxacin and claritromicin) and one case (8%) of local erythema and swelling with complete resolution of symptoms after combined treatment with local hyaluronidase, nitroglycerin paste, and systemic aspirin.53

Chin region: Of the 11 complications observed in this area, 36% (n = 4) were severe, such as persisting unilateral paresthesia of the tongue, skin necrosis and progressive ulceration despite treatment with local hyaluronidase injection, local application of warm gauzes and the use of a recombinant human epidermal growth factor gel in two patients.42 Complications occurred after HA filler injection in 86% of the patients and in 14% after CaHa injection.

DISCUSSION

The demand of minimally invasive, nonsurgical procedures including dermal fillers to treat age-associated skin changes is constantly increasing in aesthetic medicine.57 Fillers can be grouped in permanent (nonresorbable and nonbiodegradable) and nonpermanent (resorbable and biodegradable) depending on their rheologic properties and duration of effects. Permanent fillers can last more than 5 years, whereas nonpermanent fillers last for approximately 6–18 months depending on cross-linking of the product and particle size.57,58 HA and CaHa are the most frequently used nonpermanent fillers in aesthetic medicine of the face. Treatment of superficial wrinkles is performed by the injection of fillers into the superficial papillary layer of the dermis, whereas the deep wrinkles are treated by filler injections into the deep reticular layer of the dermis. HA binds water particles by its hygroscopic effect that result in an immediate enhancement of volume, whereas CaHa directly induces the development of collagen and elastin fibers that increase facial volume.59,60 Both substances undergo enzymatic degradation, offering to the patient a safer but eventually only temporary effect.53 Despite these presumably safe properties of nonpermanent fillers, complications are increasingly described in the literature.

We did not find any study comparing complications between HA and CaHa. In our review, complications occurred in 142 patients (86.5%) after HA injection and in 22 (13.5%) after CaHA injection. The much higher incidence of HA-related complications in comparison to CaHa has to be correlated to its much more common use and to the later approval on the market for cosmetic purposes in comparison with HA fillers (eg, Radiesse approval only in 2009 in the United States).61 Moreover, CaHa is less used due to its more difficult handling and lack of reversing agents such as, for example, hyaluronidase for HA.3 The complications of nonpermanent fillers administered to the face have been typically classified on the base of their temporal onset in early (<14 d), late (>14 d, < 1 y) and delayed (>1 y), as proposed by Rohrich et al.62 Given the inhomogeneity of methods to classify the complications proposed by the different authors of the considered publications for this review, we preferred to redefine the transient complications as “mild,” and the permanent ones as “severe” in the evaluated literature.

Severity and incidence of these two types of complications seems to depend upon the anatomical region where the filler is injected. Complications classified as severe or permanent are mainly resulting from a vascular compromise, which can occur as a result of intraarterial injection of the filler causing partial or complete vascular occlusion or because of extrinsic vascular compression due to intradermal or either subcutaneous accumulation of the filler adjacent to the vessel.53

Nose and nasolabial fold area: The highest rate of complications has been observed in the nose and the nasolabial fold, with a total of 59% (67 of 114) of all severe complications. Ferneini and Ferneini7 demonstrated that the complex and dense vascular branching system of the external carotid artery finally arborizing among other things into the angular artery, the superior and inferior labial arteries causes the risk of iatrogenic injury in this region. Furthermore, the angular artery that runs alongside the nose connects via the dorsal nasal artery with the ophthalmic artery arising from the internal carotid artery vascular system. The ophthalmic artery perfuses the eye and the periorbital structures, supplying the retina via the central retinal artery and the lateral and medial posterior ciliary arteries, and all the accessory structures to the eye such as the eyelids and the extrinsic muscles.45,63 Consequently, injections of fillers into the nasal region are at a particular risk of complications concerning injuries to the eye, such as total or partial vision loss and diplopia. Eventually, the pathophysiology of ocular damage is determined by retrograde flow of the filler injected into the arterial system which causes a complete or partial occlusion of the ophthalmic artery or one of its branches.47 In general, for rhinofiller procedures, Helmy64 suggests an accurate syringe aspiration before injection and avoidance of high-pressure bolus injection to prevent intravascular unintended accidents. Specifically to this anatomic area, to best avoid this type of complications in the nasolabial fold, authors such as Halepas et al53 have suggested to inject the filler laterally to a vertical line extending from the medial chantus to the labial commissure, whereas Scheuer et al65 suggested treating the upper third of the fold deep injections into the preperiosteal layer using a kind of bolus or depot technique.45 For nasal augmentation, Rohrich et al66 have suggested the injection of an HA filler with a high elasticity (G’—elastic modulus of the substance) into the preperiosteal layer rather than into the subcutaneous layer of the dorsum of the nose to decrease the risk of severe vascular complications. Another ischemia-related complication is skin necrosis. This has been reported in 27% of all severe or permanent complications. It seems to be a consequence of the filler’s microembolization or external compression to the microvascular network supplying the skin resulting from overfilling.67,68 Cutaneous blanching and prolonged capillary refill, edema, erythema, and disproportionate pain are clinical signs that may indicate “over”-injection. Massage of the area and hydrolysis using hyaluronidase may reverse HA-overfilling and eventually avoid skin necrosis.19 In this regard, Sun et al19 proposed a single administration of 150 IU of hyaluronidase dissolved in saline solution and injected directly into the involved area. They have also shown that the benefit of hyaluronidase may be effective if administered until two days after the onset of symptoms indicating skin ischemia.19,67 Halepas et al53 proposed a specific protocol to best prevent skin necrosis after injection of fillers, including local application of warm gauzes and nitroglycerin paste to induce local vasodilatation, administration of filler reversal agent if present, administration of prednisone to reduce the swelling and inflammation, administration of acetylsalicylic acid (ASS) to reduce thrombocyte aggregation, administration of a cefalexin to prevent infection and, finally, hyperbaric O2 to optimize blood oxygenation.

Glabella, forehead, eyebrow areas: Further critical anatomical regions are the area of the glabella as well as the forehead and eyebrows, where a total of 21 and 14 severe or permanent complications have been reported, respectively. They are strongly related to the anatomy of the supratrochlear and the supraorbital arteries that pierce the orbital bone and run through the corrugator supercilii muscle to finally end in the subcutaneous layer of the subfrontal space.69 These two arteries branch with the ophthalmic artery and are therefore associated with a significant risk of severe or permanent complications. Indeed, almost all of the complications reported in this area concerned the eye, potentially a consequence of retrograde flow of the filler into the ophthalmic artery. The remaining severe complications were related to skin ischemia, wherefore Scheuer et al65 have suggested the superficial placement of a low elasticity (G’) filler with a “serial puncture” technique with the periodical release of little bolus injections along the defect while compressing with digital pressure the supraorbital and supratrochlear vessels.66 Regarding the use of CaHA in the region of the glabella, the forehead and the eyebrows, Oh et al describe untreatable and irreversible vision loss following CaHa embolus to the ophthalmic artery, whereas Vu et al32 report partial improvement of visual acuity from blindness to light perception after three retrobulbar injections of hyaluronidase, prednisone, and ASS. Hyaluronidase injected locally after CaHa-induced ischemic complications was explained with some effect on the microcirculation and not directly as a result of its enzymatic degradation as observed after HA injections, but this is still uncertain and needs further research.32

Temporal area: Eight severe or permanent complications have been described following filler injection to the temporal area, all of which showed ophthalmological and periorbital consequences, such as total or partial vision loss, diplopia, and eyelid ptosis. These complications are all related to direct or indirect injury to the frontal branch of the superficial temporal artery and its ramification.66,70 To minimize risks in this area, Carruthers et al71 have suggested local application of ice to induce vasoconstriction before injecting the filler. The filler may be mixed at a 1:1 ratio with 0.5% lidocaine with epinephrine to avoid bleeding.65 They further recommend the use of blunt cannulas and small syringes to best control volume and pressure at injection.71 If an intravascular embolus of CaHa is suspected, the authors propose ocular massage and reduction of intraocular pressure to route the embolus to the periphery.71 The recommendation of Rohrich et al for this area is to perform superficial injections into the subdermal layer with a low elasticity (G’) HA filler avoiding the above-mentioned vascular structures, or deeper injections approximately 2.5 cm higher than the periorbital arch.66

Chin area: Four severe and permanent complications were recorded in the chin area including skin necrosis and unilateral paresthesia of the tongue.42 They most likely result from vascular injuries of side branches of the lingual and facial artery. The low rate of severe or permanent complications in this area may be the consequence of the dense and well collateralized and interconnecting vascular network that may compensate the occlusion of some side branches. Accordingly, Rohrich et al66 suggest that in chin augmentation, injections should be performed with a high G’ filler in the preperiosteal layer and should not extend beyond a vertical line defined by the medial cantus. Injection techniques for the mentioned anatomical area are summarized in Table 5. No severe or permanent complications have been described following the use of nonpermanent facial filler for cosmetic purposes in the region of the lower eyelid, the tear trough, the cheeks, the lips, the perioral, and the marionette lines in articles published in the examined period and with the search algorithm applied.

TABLE 5.

Injection Techniques per Anatomic Area

| Risk Area | Technique |

|---|---|

| Forehead and eyebrows | Low G’ filler dermal injections with “serial puncture” technique with the periodical release of little bolus injections along the defect while compressing with digital pressure the supraorbital and the supratrochlear vessels |

| Temporal region | Low G’ filler mixed at a 1:1 ratio with 0.5% lidocaine with epinephrine, injecting lateral to medial below the dermal layer. Deeper injections may be performed approximately 2.5 cm higher than the periorbital arch. The use of small cannulas and small syringes is suggested |

| Glabellar region | Low G’ filler dermal injections with “serial puncture” technique |

| Nose | High G’ filler injected into the preperiosteal layer. Concomitant digital compression of the dorsal nasal and angular artery is suggested |

| Nasolabial fold | High G’ filler injected into the preperiosteal layer along the pyriform opening when treating the upper third of the nasolabial fold. Alternatively, one can inject laterally to a vertical line extending from the medial canthus to the labial commissure of the mouth. The use of cannulas is suggested in this area |

| Chin region | High G’ filler injected into the preperiosteal layer. Injections should not extend beyond a vertical line defined by the medial canthus |

CONCLUSIONS

The injection of nonpermanent fillers to the face for cosmetic purposes might cause severe and permanent complications, particularly affecting the eye and the palpebral region. The risk is correlated to the complex vascular anatomy of the face interconnecting the extracranial and intracranial vascular network of the carotid artery.

Adequate knowledge of the anatomy of the face is therefore mandatory. Adherence to appropriate technical recommendations is required, including the use of correct needles or cannulas and injection to the appropriate soft-tissue layer depending on the area to be treated. Close clinical follow-up early after injection and inspection for potential complication-associated symptoms are strongly recommended and collection of detailed patient history is needed. The use of fillers that have antidotes such as hyaluronidase for HA have to be preferred.

Footnotes

Published online 22 October 2021.

Drs. Oranges and Brucato contributed equally to this work.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yu JTS, Peng L, Ataullah S. Chronic eyelid edema following periocular hyaluronic acid filler treatment. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33:e139–e140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hönig JF, Brink U, Korabiowska M. Severe granulomatous allergic tissue reaction after hyaluronic acid injection in the treatment of facial lines and its surgical correction. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Loghem JAJ. Use of calcium hydroxylapatite in the upper third of the face: retrospective analysis of techniques, dilutions and adverse events. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:1025–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tracy L, Ridgway J, Nelson JS, et al. Calcium hydroxylapatite associated soft tissue necrosis: a case report and treatment guideline. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:564–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urdiales-Gálvez F, Delgado NE, Figueiredo V, et al. Preventing the complications associated with the use of dermal fillers in facial aesthetic procedures: an expert group consensus report. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41:667–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Boulle K, Heydenrych I. Patient factors influencing dermal filler complications: prevention, assessment, and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:205–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferneini EM, Ferneini AM. An overview of vascular adverse events associated with facial soft tissue fillers: recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74:1630–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiang YZ, Pierone G, Al-Niaimi F. Dermal fillers: pathophysiology, prevention and treatment of complications. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oranges CM, Sisti A, Sisti G. Labia minora reduction techniques: a comprehensive literature review. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35:419–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oranges CM, Tremp M, di Summa PG, et al. Gluteal augmentation techniques: a comprehensive literature review. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37:560–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oranges CM, Haug M, Schaefer DJ. Body contouring. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:944e–945e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Plast Surg Nurs. 2015;35:13–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arron ST, Neuhaus IM. Persistent delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to injectable non-animal-stabilized hyaluronic acid. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6:167–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sires B, Laukaitis S, Whitehouse P. Radiesse-induced herpes zoster. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:218–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwon SG, Hong JW, Roh TS, et al. Ischemic oculomotor nerve palsy and skin necrosis caused by vascular embolization after hyaluronic acid filler injection: a case report. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;71:333–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oh BL, Jung C, Park KH, et al. Therapeutic intra-arterial hyaluronidase infusion for ophthalmic artery occlusion following cosmetic facial filler (hyaluronic acid) injection. Neuroophthalmology. 2014;38:39–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rongioletti F, Atzori L, Ferreli C, et al. Granulomatous reactions after injections of multiple aesthetic micro-implants in temporal combinations: a complication of filler addiction. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1188–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh YH, Lin CW, Huang JS, et al. Severe ocular complications following facial calcium hydroxylapatite injections: two case reports. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2015;5:36–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun ZS, Zhu GZ, Wang HB, et al. Clinical outcomes of impending nasal skin necrosis related to nose and nasolabial fold augmentation with hyaluronic acid fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136:434e–441e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chou CC, Chen HH, Tsai YY, et al. Choroid vascular occlusion and ischemic optic neuropathy after facial calcium hydroxyapatite injection- a case report. BMC Surg. 2015;15:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuster B. Injection rhinoplasty with hyaluronic acid and calcium hydroxyapatite: a retrospective survey investigating outcome and complication rates. Facial Plast Surg 2015;31:301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim A, Kim SH, Kim HJ, et al. Ophthalmoplegia as a complication of cosmetic facial filler injection. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94:e377–e379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan X, Dong M, Li T, et al. Two cases of adverse reactions of hyaluronic acid-based filler injections. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4:e1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang BK, Kang IJ, Jeong KH, et al. Treatment of glabella skin necrosis following injection of hyaluronic acid filler using platelet-rich plasma. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:111–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen E, Yatziv Y, Leibovitch I, et al. A case report of ophthalmic artery emboli secondary to calcium hydroxylapatite filler injection for nose augmentation- long-term outcome. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016;16:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Or L, Eviatar JA, Massry GG, et al. Xanthelasma-like reaction to filler injection. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33:244–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu GZ, Sun ZS, Liao WX, et al. Efficacy of retrobulbar hyaluronidase injection for vision loss resulting from hyaluronic acid filler embolization. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;38:12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JI, Kang SJ, Sun H. Skin necrosis with oculomotor nerve palsy due to a hyaluronic acid filler injection. Arch Plast Surg. 2017;44:340–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dagi Glass LR, Choi CJ, Lee NG. Orbital complication following calcium hydroxylapatite filler injection. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33:S16–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JL, Shin JY, Roh SG, et al. Demarcative necrosis along previous laceration line after filler injection. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28:e481–e482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shin JY, An MY, Roh SG, et al. Unusual aspergillus infection after dermal filler injection. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28:2066–2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vu PQ, Grob SR, Tao JP. Light perception vision recovery after treatment for calcium hydroxylapatite cosmetic filler-induced blindness. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34:e189–e192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vidič M, Bartenjev I. An adverse reaction after hyaluronic acid filler application: a case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adria. 2018;27:165–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khoo CS, Tan HJ, Sharis Osman S. A case of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) encephalitis as a possible complication of cosmetic nasal dermal filler injection. Am J Case Rep. 2018;19:825–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bae IH, Kim MS, Choi H, et al. Ischemic oculomotor nerve palsy due to hyaluronic acid filler injection. J Cosmet Dermatol 2018:17;1016–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robati RM, Moeineddin F, Almasi-Nasrabadi M. The risk of skin necrosis following hyaluronic acid filler injection in patients with a history of cosmetic rhinoplasty. Aesthet Surg J. 2018;38:883–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alshaer Z, Alsaadi Y, Mrad MA. Successful management of infected facial filler with brucella. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42:1388–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fang M, Rahman E, Kapoor KM. Managing complications of submental artery involvement after hyaluronic acid filler injection in Chin region. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018:6:e1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henderson R, Reilly DA, Cooper JS. Hyperbaric oxygen for ischemia due to injection of cosmetic fillers: case report and issues. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6:e1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thanasarnaksorn W, Cotofana S, Rudolph C, et al. Severe vision loss caused by cosmetic filler augmentation: case series with review of cause and therapy. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:712–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han J, He Y, Liu K, et al. Necrosis of the glabella after injection with hyaluronic acid into the forehead. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29:e726–e727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Q, Zhao Y, Li H, et al. Vascular complications after chin augmentation using hyaluronic acid. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42:553–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doerfler L, Hanke CW. Arterial occlusion and necrosis following hyaluronic acid injection and a review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chauhan A, Singh S. Management of delayed skin necrosis following hyaluronic acid filler injection using pulsed hyaluronidase. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2019;12:183–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang L, Pan L, Xu H, et al. Clinical observations and the anatomical basis of blindness after facial hyaluronic acid injection. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019;43:1054–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marusza W, Olszanski R, Sierdzinski J, et al. Treatment of late bacterial infections resulting from soft-tissue filler injections. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:469–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oh DJ, Jiang Y, Mieler WF. Ophthalmic artery occlusion and subsequent retinal fibrosis from a calcium hydroxylapatite filler injection. J Vitreoretin Dis. 2019;3:190–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ciancio F, Tarico MS, Giudice G, et al. Early hyaluronidase use in preventing skin necrosis after treatment with dermal fillers: Report of two cases. F1000Res. 2018;7:1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turkmani MG, De Boulle K, Philipp-Dormston WG. Delayed hypersensitivity reaction to hyaluronic acid dermal filler following influenza-like illness. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:277–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uittenbogaard D, Lansdorp CA, Bauland CG, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for dermal ischemia after dermal filler injection with calcium hydroxylapatite: a case report. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2019;46:207–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khalil K, Arnold N, Seiger E. Chronic eyelid edema and xerophthalmia secondary to periorbital hyaluronic acid filler injection. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:824–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaczorowski M, Nelke K, Łuczak K, et al. Filler migration and florid granulomatous reaction to hyaluronic acid mimicking a buccal tumor. J Craniofac Surg. 2020;31:e78–e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Halepas S, Peters SM, Goldsmith JL, et al. Vascular compromise after soft tissue facial fillers: case report and review of current treatment protocols. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;78:440–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang LX, Lai LY, Zhou GW, et al. Evaluation of intraarterial thrombolysis in treatment of cosmetic facial filler-related ophthalmic artery occlusion. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145:42e–50e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andre P, Haneke E. Nicolau syndrome due to hyaluronic acid injections. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stojanovič L, Majdič N. Effectiveness and safety of hyaluronic acid fillers used to enhance overall lip fullness: A systematic review of clinical studies. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fallacara A, Manfredini S, Durini E, et al. Hyaluronic acid fillers in soft tissue regeneration. Facial Plast Surg. 2017;33:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Narins RS, Brandt FS, Lorenc ZP, et al. Twelve-month persistency of a novel ribose-cross-linked collagen dermal filler. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34 Suppl 1:S31–S39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johl SS, Burgett RA. Dermal filler agents: a practical review. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:471–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hotta T. Dermal fillers. The next generation. Plast Surg Nurs. 2004;24:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Attenello NH, Maas CS. Injectable fillers: review of material and properties. Facial Plast Surg. 2015;31:29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rohrich RJ, Nguyen AT, Kenkel JM. Lexicon for soft tissue implants. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35 Suppl 2:1605–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cotofana S, Lachman N. Arteries of the face and their relevance for minimally invasive facial procedures: an anatomical review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:416–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Helmy Y. Non-surgical rhinoplasty using filler, Botox, and thread remodeling: retro analysis of 332 cases. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scheuer JF, Sieber DA, Pezeshk RA, et al. Anatomy of the facial danger zones: maximizing safety during soft-tissue filler injections. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:50e–58e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rohrich RJ, Bartlett EL, Dayan E. Practical approach and safety of hyaluronic acid fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7:e2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ozturk CN, Li Y, Tung R, et al. Complications following injection of soft-tissue fillers. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:862–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Humphrey CD, Arkins JP, Dayan SH. Soft tissue fillers in the nose. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29:477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Berchtold V, Stofferin H, Moriggl B, et al. The supraorbital region revisited: an anatomic exploration of the neuro-vascular bundle with regard to frontal migraine headache. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:1171–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O’Brien JX, Ashton MW, Rozen WM, et al. New perspectives on the surgical anatomy and nomenclature of the temporal region: literature review and dissection study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:461e–463e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carruthers JDA, Fagien S, Rohrich RJ, et al. Blindness caused by cosmetic filler injection: a review of cause and therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:1197–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]