Abstract

Background

Efficacy and safety data of COVID-19 vaccines among cancer populations have been limited; however, preliminary data from recent studies have emerged regarding their immunogenicity and safety in this population. In this review, we examined current peer-reviewed publications containing serological and safety data after COVID-19 vaccination of patients with cancer.

Methods

This analysis examined 21 studies with a total of 5012 patients with cancer, of which 2676 (53%) had haematological malignancies, 2309 (46%) had solid cancers and 739 were healthy controls. Serological responses by anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1/S2 immunoglobulin G antibody levels and post-vaccination patient questionnaires regarding vaccine-related side-effects after the first and second dose were collected and analysed.

Results

In general, a single dose of the COVID-19 vaccine yields weaker and heterogeneous serological responses in both patients with haematological and solid malignancies. On receiving a second dose, serological response rates indicate a substantial increase in seropositivity to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in all cancer cohorts, but antibody titres remain reduced in comparison with healthy controls. Furthermore, seroconversion in patients with haematological malignancies was significantly lower than that in patients with solid tumours. COVID-19 vaccines are safe and well-tolerated in patients with cancer based on current data of local and systemic effects.

Conclusion

Together, these data support the prioritisation of patients with cancer to receive their first and second doses to minimise the risk of COVID-19 infection and severe complications in this vulnerable population. Additional prophylactic measures must be considered for high-risk patients where current vaccination programs may not mount sufficient protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Keywords: COVID-19 vaccines, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Neoplasms, Immunity, Seroconversion

1. Introduction

COVID-19, which is caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, first emerged in December 2019 and has since led to over 150 million infections worldwide and over four million deaths to date [1]. There is substantial evidence that patients with cancer are at a greater risk of contracting and suffering from severe complications due to viral infections, including COVID-19 [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]. Although safety, tolerability and efficacy data from clinical trials of several vaccines targeting the SARS-CoV-2 virus have been published, limited data are available among patients with active malignancies because of their ineligibility in most studies [13]. Furthermore, a major part of vaccine hesitancy in patients with cancer is caused by the lack of efficacy and safety data available for their disease population [14]. Given the widespread immunisation of approved COVID-19 vaccines in some countries, safety and immunogenicity data are now emerging for patients with cancer. There is an urgent need to inform the recommendations and guidelines for the expedited procurement and delivery of COVID-19 vaccines in vulnerable populations, such as immunocompromised patients with cancer, with the most relevant evidence available. Importantly, this information is critical to aid in the informed decision-making of patients with cancer and their family members, along with members of the medical community [15]. In this review, we explore the current evaluation of the immunogenicity and safety of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer.

2. Methods

We searched PubMed for publications from inception to 14th July 2021, using the search terms (‘covid 19 vaccines’ [MeSH Terms] OR (‘covid 19’ [All Fields] AND ‘vaccines’ [All Fields]) OR ‘covid 19 vaccines’ [All Fields] OR ‘covid 19 vaccine’ [All Fields]) AND (‘cancers’ [All Fields] OR ‘neoplasms’ [MeSH Terms] OR ‘neoplasms’ [All Fields] OR ‘cancer’ [All Fields]) AND (‘patients’ [MeSH Terms] OR ‘patients’ [All Fields] OR ‘patient’ [All Fields]). We reviewed only articles published in English investigating serological and toxicity responses to COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer. The final reference list was generated on the basis of their relevance to the scope of this review. Continuous variables were compared using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U independent samples test.

3. Results

This review included 21 studies containing serological and/or toxicity data after COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancer. A total of 5012 patients with active malignancies, of which 2676 (53%) had haematological malignancies and 2309 (46%) had solid cancers, and 739 healthy control subjects were analysed. Clinical characteristics of the patients with cancer and healthy controls are amalgamated and presented in Table 1 . Overall, the median age of the patients with cancer ranged from 40 to 75.5 years, and the majority were men (2619 [53%]). Among healthy controls, the median age ranged between 40 and 81 years. Nineteen of 21 studies specified patients undergoing cancer-directed therapies, and their treatment types are described (Table 1). Patients with suspected COVID-19 exposure before vaccination were excluded. In general, serological responses were acquired through blood sampling after the first (partial) or second (complete) dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and quantified by anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1/S2 immunoglobulin G (IgG) (anti-S IgG) antibody levels. The detection methods for anti-S IgG varied across studies and are described in Table 2, Table 3 .

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with cancer and healthy control subjects included in this review.

| Study | Country | n | Age (years, median) (IQR/range) | Sex |

Type of malignancy |

Cancer staging |

Undergoing treatment |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F |

M |

HEM |

SOL |

Unk |

LOC |

MET |

Yes |

No |

||||||||||

| CT |

IM |

RD |

TT |

OTH |

CS |

CR/PR |

NT |

|||||||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||||||||||||

| Addeo 2021 [16] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mixed cancer | Switzerland, US | 131 | 63 (55–69) | 59 (45) | 72 (55) | 25 (19) | 106 (81) | ·· | ·· | ·· | 30 (23) | 14 (11) | ·· | 15 (11) | 1 (1) | 49 (37) | ·· | ·· |

| Barrière 2021 [17] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Solid cancer | France | 122 | 40 (44–90) | 58 (48) | 64 (53) | ·· | 122 (100) | ·· | ·· | ·· | 105 (86) | ·· | ·· | 105 (86) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Healthy control | 29 | 53 (21–81) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | |

| Bird 2021 [18] | ||||||||||||||||||

| MM | UK | 93 | 67 (59–73) | 38 (41) | 55 (59) | 93 (100) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 19 (27) | 44 (67) | ·· | 21 (32) | 52 (79) | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Chowdhury 2021 [19] | ||||||||||||||||||

| CMN | UK | 59 | 62 (52–73) | 32 (54) | 27 (46) | 59 (100) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 12 (20) | ·· | ·· | 18 (31) | 15 (25) | ·· | ·· | 17 (29) |

| Healthy control | 232 | 62 (60–76) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | |

| Fong 2021 [20] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Haematological cancer | Italy | 56 | 68 (31–85) | 74 (48) | 80 (52) | 56 (36) | 98 (64) | ·· | ·· | ·· | 20 (36) | 10 (18) | ·· | 6 (11) | 2 (4) | 18 (33) | ·· | ·· |

| Solid cancer | 98 | 37 (38) | 9 (9) | ·· | 28 (29) | 17 (17) | 7 (7) | ·· | ·· | |||||||||

| Goshen-Lago 2021 [21] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Solid cancer | Israel | 232 | 68 (25–88) | 100 (43) | 132 (57) | ·· | 232 (100) | ·· | 60 (26) | 172 (74) | 134 (58) | 83 (36) | ·· | ·· | 81 (35) | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Herishanu 2021 [22] | ||||||||||||||||||

| CLL | Israel | 167 | 71 (63–76) | 55 (33) | 112 (67) | 167 (100) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 50 (30) | 22 (13) | ·· | 22 (13) | 3 (2) | ·· | 24 (14) | 58 (35) |

| Healthy control | 52 | 68 (64–74) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | |

| Harrington 2021 [23] | ||||||||||||||||||

| MPN | UK | 21 | 58 (45–63) | 14 (67) | 7 (33) | 21 (100) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 4 (19) | 4 (19) | ·· | 6 (29) | ·· | 7 (33) | ·· | ·· |

| Heudel 2021 [24] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mixed cancer | France | 1503 | 64.8 (16.7–95.4) | 735 (49) | 768 (51) | 300 (20) | 1203 (80) | ·· | 422 (28) | 1081 (72) | 1003 (67) | 60 (4) | 245 (16) | ·· | 189 (13) | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Maneikis 2021 [25] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Haematological cancer | Lithuania | 857 | 65 (54–72) | 453 (53) | 404 (47) | 857 (100) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 156 (18) | 333 (39) | ·· | 111 (13) | 393 (46) | ·· | ·· | 53 (6) |

| Healthy control | 68 | 40 (32–53) | 56 (82) | 12 (18) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | |

| Massarweh 2021 [26] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Solid cancer | Israel | 102 | 66 (56–72) | 44 (43) | 58 (57) | ·· | 102 (100) | ·· | 26 (25) | 76 (75) | 30 (29) | 22 (22) | ·· | ·· | 50 (50) | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Healthy control | 78 | 62 (49–70) | 53 (68) | 25 (32) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | |

| Monin 2021 [27] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mixed cancer | UK | 151 | 73 (64.5–79.5) | 73 (48) | 78 (52) | 56 (37) | 95 (63) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Healthy control | 54 | 40.5 (31.3–50) | 26 (48) | 28 (52) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | |

| Palich 2021 [28] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Solid cancer | France | 110a | 66 (54–74) | 66 (60) | 44 (40) | ·· | 109 (97) | 3 (3) | 47 (43) | 63 (57) | 38 (35) | 17 (16) | 6 (6) | 26 (24) | 34 (31) | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Healthy control | 25 | 55 (38–62) | 18 (72) | 7 (28) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | |

| Pimpinelli 2021 [29] | ||||||||||||||||||

| MM | Italy | 42 | 73 (47–78) | 19 (45) | 23 (55) | 42 (100) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 23 (55) | 19 (45) | ·· | 6 (14) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| MPN | 50 | 70 (28–80) | 24 (48) | 26 (52) | 50 (100) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 20 (40) | 2 (4) | ·· | 26 (52) | 2 (4) | ·· | ·· | ·· | |

| Healthy control | 36 | 81 (79–87) | 18 (50) | 18 (50) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | |

| Re 2021 [30] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Haematological cancer | France | 102 | 75.5 (33–93) | 35 (34) | 67 (66) | 102 (100) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 16 (16) | 39 (38) | ·· | 36 (35) | ·· | 47 (46) | ·· | 9 (9) |

| Roeker 2021 [31] | ||||||||||||||||||

| CLL | US | 44 | 71 (37–89) | 21 (48) | 23 (52) | 44 (100) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 14 (32) | 14 (32) | ·· | 7 (16) | ·· | ·· | 26 (59) | 18 (41) |

| Stampfer 2021 [32] | ||||||||||||||||||

| MM | US | 103 | 68 (35–88) | 42 (41) | 61 (59) | 103 (100) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 84 (82) | 69 (67) | ·· | ·· | 87 (84) | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Healthy control | 31 | 61 (26–85) | 19 (61) | 12 (39) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | |

| Thakkar 2021 [33] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mixed cancer | US | 200 | 67 (27–90) | 116 (58) | 84 (42) | 66 (33) | 134 (67) | ·· | ·· | ·· | 112 (56) | 56 (29) | 55 (28) | 62 (32) | ·· | ·· | ·· | 11 (6) |

| Healthy control | 26 | 64 (37–82) | 16 (62) | 10 (38) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | |

| Tzarfati 2021 [34] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Haematological cancer | Israel | 315 | 71 (61–78) | 139 (44) | 176 (56) | 315 (100) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 66 (21) | 65 (21) | ·· | 41 (13) | 40 (13) | ·· | ·· | 151 (48) |

| Healthy control | 108 | 69 (58–74) | 61 (56) | 47 (44) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | |

| Van Oekelen 2021 [35] | ||||||||||||||||||

| MM | US | 320 | 68 (38–93) | 135 (42) | 185 (58) | 320 (100) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 149 (47) | ·· | 127 (40) | 175 (55) | ·· | ·· | 59 (18) |

| Waissengrin 2021 [36] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Solid cancer | Israel | 134 | 72 (29–93) | 61 (44) | 73 (55) | ·· | 108 (81) | 27 (19) | 27 (19) | 107 (80) | 37 (28) | 134 (100) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

IQR, interquartile range; HEM, haematological; SOL, solid; Unk, unknown; LOC, local; MET, metastatic; CT, chemotherapy; IM, immunotherapy; RD, radiotherapy; TT, targeted therapy; OTH, other; CS, clinical surveillance; CR/PR, complete remission/partial remission; NT, not treated; CML, chronic myeloid leukaemia; CMN, chronic myeloid neoplasms; CLL, chronic lymphoid leukaemia; MM, multiple myeloma; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms.

Two patients had synchronous cancers.

Table 2.

Results from anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike IgG seroconversion studies after partial (single dose) vaccination in patients with cancer.

| Study | n | Vaccine(s) administered | Days after the first dose (days, median) (IQR) | Serological response |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-S IgG antibody test platform | Seroconversion n (%) | Titre of anti-S IgG (UA/mL, median) (IQR) | ||||

| Addeo 2021 [16] | ||||||

| Mixed cancer | ||||||

| BNT162b2 cohort | 45 | BNT162b2 | 21 | Elecsysa | 24 (83) | 29 (2–103) |

| mRNA-1273 cohort | 48 | mRNA-1273 | 28 | 74 (80) | 34 (3–106) | |

| Haematological cancer | 25 | BNT162b2/mRNA-1273 | ·· | 18 (72) | 6 (0–33) | |

| Solid cancer | 96 | ·· | 80 (83) | 44 (4–137) | ||

| Barrière 2021 [17] | ||||||

| Solid cancer | 122 | BNT162b2 | 21–28 | Elecsysa | 58 (48) | 0.52 (0–1962) |

| Healthy control | 13 | 13 (100) | 21.6 (3.26–723.2) | |||

| Bird 2021 [18] | ||||||

| MM | 45 | AZD1222 | 33 (28–38) | Ortho Clinical Diagnosticsb | 26 (58) | ·· |

| 25 | BNT162b2 | 26 (54) | ·· | |||

| Chowdhury 2021 [19] | ||||||

| CMN | 37 | BNT162b2 | 34 (28–56) | Abbottc | 22 (59) | 75 (19–328) |

| 22 | AZD1222 | 12 (55) | ||||

| Healthy control | 169 | BNT162b2 | >14 | 166 (98) | 630 (284–1328) | |

| 63 | AZD1222 | 58 (92) | ||||

| Fong 2021 [20] | ||||||

| Haematological cancer | 56 | BNT162b2 | 21 | Abbottc | 94 (61) | 101.2 (0–38,727) |

| Solid cancer | 98 | |||||

| Goshen-Lago 2021 [21] | ||||||

| Solid cancer | 86 | BNT162b2 | 17 (10–30) | Liaisond | 25 (29) | 42.3 |

| Healthy control | 261 | 220 (84) | 72 | |||

| Harrington 2021 [23] | ||||||

| MPN | 21 | BNT162b2 | 21 (21–21) | In-house ELISA | 16 (76) | 239 (25–4544) |

| Heudel 2021 [24] | ||||||

| Mixed cancer | 96 | BNT162b2/mRNA-1273/AZD1222 | 55 | Unspecified | 61 (63) | ·· |

| Monin 2021 [27] | ||||||

| Haematological cancer | 151 | BNT162b2 | 22 (17–27) | In-house ELISAe | 8/44 (18) | ·· |

| 37 (32–42) | 4/36 (11) | ·· | ||||

| Solid cancer | 22 (17–27) | 21/56 (38) | ·· | |||

| 37 (31.5–43.5) | 10/33 (30) | ·· | ||||

| Healthy control | 54 | 21 | 32/34 (94) | ·· | ||

| 35 | 18/21 (86) | ·· | ||||

| Palich 2021 [28] | ||||||

| Solid cancer | 110 | BNT162b2 | 21 | Abbottc | 52 (55) | 315 (140–748) |

| Healthy control | 25 | 25 (100) | 680 (360–930) | |||

| Pimpinelli 2021 [29] | ||||||

| MM | 42 | BNT162b2 | 21 | Liaisond | 9 (21) | 7.5 (5.6–10.4)f |

| MPN | 50 | 26 (52) | 16.2 (11.7–22.3)f | |||

| Healthy control | 36 | 19 (53) | 17.1 (12.0–24.1)f | |||

| Re 2021 [30] | ||||||

| Haematological cancer | 102 | BNT162b2 (n = 95, 93%); mRNA-1273 (n = 7, 7%) | 42–56 | Unspecified | 63 (62) | 16.8 (0–17,000) |

| Stampfer 2021 [32] | ||||||

| MM | 96 | BNT162b2/mRNA-1273 | 12–21 | In-house ELISAg | 20 (21) | 11.6 (SD = 297.3) |

| Thakkar 2021 [33] | ||||||

| Mixed cancer | ||||||

| Ad26.COV2.S cohort | 20 | Ad26.COV2.S | 30 (19–53) | Abbottc | 17 (85) | 1121 (SD = 17,571) |

anti-S IgG, anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1/S2 immunoglobulin G; SD, standard deviation; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IQR, interquartile range; CMN, chronic myeloid neoplasms; MM, multiple myeloma; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms.

Elecsys Anti-SARS-CoV-2S assay, with a detection threshold of 0.80 U/mL for anti-S IgG.

Ortho Clinical Diagnostics Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG test, with a detection threshold of ≥1 s/c (signal/cut-off).

Abbott SARS-CoV-2 IgG chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA), with a detection threshold of 50 UA/mL for anti-S IgG.

LIAISON SARS-CoV-2 S1/S2 IgG test, with a detection threshold of 15 AU/mL for anti-S IgG.

Evaluated via ELISA, with a detection threshold of OD 4-fold above background at 405 nM where EC50 was not reached at 1:25, and a value of 25 was assigned.

Evaluated via ELISA, methods and detection threshold as described in Ref. [32].

Geometric mean concentration.

Table 3.

Results from anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike IgG seroconversion studies after complete (second dose) vaccination in patients with cancer.

| Study | n | Vaccine(s) administered | Days after the second dose (days, median) (IQR) | Serological response |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-S IgG antibody test platform | Seroconversion n (%) | Titre of anti-S IgG (UA/mL, median) (IQR) | ||||

| Addeo 2021 [16] | ||||||

| Mixed cancer | ||||||

| BNT162b2 cohort | 30 | BNT162b2 | 29 | Elecsysa | 28 (93) | 1232 (258–2500) |

| mRNA-1273 cohort | 93 | mRNA-1273 | 22 | 88 (95) | 2500 (442–2500) | |

| Haematological cancer | 22 | BNT162b2/mRNA-1273 | ·· | 17 (77) | 832 (24–2500) | |

| Solid cancer | 101 | ·· | 99 (98) | 2500 (514–2500) | ||

| Barrière 2021 [17] | ||||||

| Solid cancer | 42 | BNT162b2 | 15–27 | Elecsysa | 40 (95) | 245.2 (0–5467) |

| Healthy control | 24 | 24 (100) | 2517 (157.6–6318) | |||

| Fong 2021 [20] | ||||||

| Haematological cancer | 56 | BNT162b2 | 21 | Abbottb | 132 (86) | ·· |

| Solid cancer | 98 | |||||

| Goshen-Lago 2021 [21] | ||||||

| Solid cancer | 218 | BNT162b2 | 16 (2–54) | Liaisonc | 187 (86) | ·· |

| Herishanu 2021 [22] | ||||||

| CLL | 167 | BNT162b2 | 15 (14–17) | Elecsysa | 66 (40) | ·· |

| 52 | 27 (52) | 155 (7.6–490.3) | ||||

| Healthy control | 52 | 52 (100) | 1084 (128.9–1879) | |||

| Massarweh 2021 [26] | ||||||

| Solid cancer | 102 | BNT162b2 | 38 (32–43) | Abbottb | 92 (90) | 1931 (509–4386) |

| Healthy control | 78 | 40 (32–44) | 78 (100) | 7160 (3129–11,241) | ||

| Monin 2021 [27] | ||||||

| Haematological cancer | 5 | BNT162b2 | 37 (35–40) | In-house ELISAd | 3 (60) | ·· |

| Solid cancer | 19 | 37 (35–42) | 18 (95) | ·· | ||

| Healthy control | 12 | 40 (36–42) | 12 (100) | ·· | ||

| Pimpinelli 2021 [29] | ||||||

| MM | 42 | BNT162b2 | 14 | Liaisonc | 33 (79) | 106.7 (62.3–179.7)e |

| MPN | 50 | 44 (88) | 172.9 (106.5–257.0)e | |||

| Healthy control | 36 | 36 (100) | 353.3 (255.6–470.0)e | |||

| Roeker 2021 [31] | ||||||

| CLL | 44 | BNT162b2 | 21 (14–48) | Liaisonc | 23 (52) | ·· |

| Stampfer 2021 [32] | ||||||

| MM | 96 | BNT162b2/mRNA-1273 | 14–21 | In-house ELISAf | 64 (67) | 173.7 (SD = 1653.3) |

| Thakkar 2021 [33] | ||||||

| Mixed cancer | ||||||

| BNT162b2 cohort | 115 | BNT162b2 | 30 (19–53) | Abbottb | 110 (95) | 5173 (SD = 16,699) |

| mRNA-1273 cohort | 62 | mRNA-1273 | 58 (94) | 11,963 (SD = 18,742) | ||

| Haematological cancer | 66 | BNT162b2 (n = 115, 54%); mRNA-1273 (n = 62, 31%); single dose Ad26.COV2.S (n = 20, 10%); unknown mRNA-based (n = 3, 2%) | 28.5 | 56 (85) | 2528 (SD = 12,338) | |

| Solid cancer | 134 | 31.5 | 131 (98) | 7858 (SD = 18,103) | ||

| Tzarfati 2021 [34] | ||||||

| Haematological cancer | 315 | BNT162b2 | 32 (29–40) | Liaisonc | 235 (75) | 85 (11–172) |

| Matched | 69 | ·· | 52 (75) | 90 (12–185) | ||

| Healthy control | 108 | 33.5 (28–39) | 107 (99) | 157 (130–221) | ||

| Matched | 69 | ·· | 68 (99) | 173 (133–232) | ||

| Van Oekelen 2021 [35] | ||||||

| MM | ||||||

| BNT162b2 cohort | 177 | BNT162b2 | 51 (11–118) | COVID-SeroKlirg | 144 (81) | 149 (5–7882) |

| mRNA-1273 cohort | 76 | mRNA-1273 | 68 (89) | |||

| Healthy control | 67 | BNT162b2/mRNA-1273 | 67 (100) | 300 (21–3335) | ||

anti-S IgG, anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1/S2 immunoglobulin G; SD, standard deviation; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IQR, interquartile range; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; MM, multiple myeloma; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms.

Elecsys Anti-SARS-CoV-2S assay, with a detection threshold of 0.80 U/mL for anti-S IgG.

LIAISON SARS-CoV-2 S1/S2 IgG test, with a detection threshold of 15 AU/mL for anti-S IgG.

Abbott SARS-CoV-2 IgG chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA), with a detection threshold of 50 UA/mL for anti-S IgG.

Evaluated via ELISA, with a detection threshold of OD 4-fold above background at 405 nM where EC50 was not reached at 1:25, and a value of 25 was assigned.

Geometric mean concentration.

Evaluated via ELISA, methods and detection threshold as described in Ref. [32].

COVID-SeroKlir, Kantaro SARS-CoV-2 IgG Ab kit, with a detection threshold of ≥5 AU/mL for anti-S IgG.

Single dose–response rates of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) were assessed in 13 studies [[16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21],23,24,[27], [28], [29], [30],32], mRNA-1273 (Moderna) in four studies [16,24,30,32], AZD1222 (Oxford-AstraZeneca) in three studies [18,19,24] and Ad26.COV2.S (Janssen) in one study [33]. Of these, 12 studies classified their patient cohorts with cancer (11 cohorts with haematological malignancies, of which three were primarily patients with multiple myeloma [MM], two of patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms [MPNs], one study containing patients with chronic myeloid neoplasms and five cohorts with solid tumours) in addition to seven studies with data from healthy control subjects. The results from these studies are described in Table 2, including positive serological response rates (seroconversion) and anti-S IgG antibody titre after partial vaccination. Seroconversion and antibody titre data varied between studies and based on the type of malignancy (Fig. 1 A). After partial COVID-19 vaccination, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) seroconversion rate across all patient cohorts with cancer was 55% (41–63%; N = 18), which was significantly lower than that of healthy controls (median [IQR]: 94% [88–99%]; N = 7; p = 0.002). Seroconversion of patient cohorts with haematological malignancies (median [IQR]: 55% [37–61%]; N = 11; p = 0.005) or solid cancers (48% [38–55%]; N = 5; p = 0.0147) was significantly reduced in comparison with healthy controls.

Fig. 1.

Boxplots of positive serological response rates (%) by disease group (A) after partial COVID-19 vaccination (first dose) or (B) after complete COVID-19 vaccination (second dose). The detection thresholds for positive anti-S IgG antibodies are dependent on the biochemical assay used in each study, which are indicated in Table 2, Table 3. Each point indicates a study cohort where data were available. Pairwise comparisons are based on the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U independent-samples test. anti-S IgG, anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1/S2 immunoglobulin G.

For second dose–response rates, mRNA vaccines BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 were assessed in 13 studies [16,17,[20], [21], [22],26,27,29,[31], [32], [33], [34], [35]] and in four studies [16,32,33,35], respectively. Within these studies, 17 patient cohorts with cancer were identified (11 of which were patients with haematological malignancies, where two were subclassified with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia [CLL], three with patients with MM and one with patients with MPN and six cohorts with solid tumours). Second dose COVID-19 vaccination data from healthy control subjects were included in six studies. Seroconversion and antibody titre response data are summarised in Table 3. After complete COVID-19 vaccination, median (IQR) seroconversion rates across all patient cohorts with cancer were 85% (75–90%; N = 17) versus 100% (100-100%; N = 6) in the healthy control group (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1B). Seropositivity was significantly reduced when compared with healthy controls in patient cohorts with haematological malignancies (median [IQR]: 77% [64–83%]; N = 11; p < 0.001) or solid cancers (95% [91–97%]; N = 6; p = 0.004). Furthermore, full-dose seroconversion in patients with haematological malignancies was significantly lower than that of patients with solid cancer (p = 0.002).

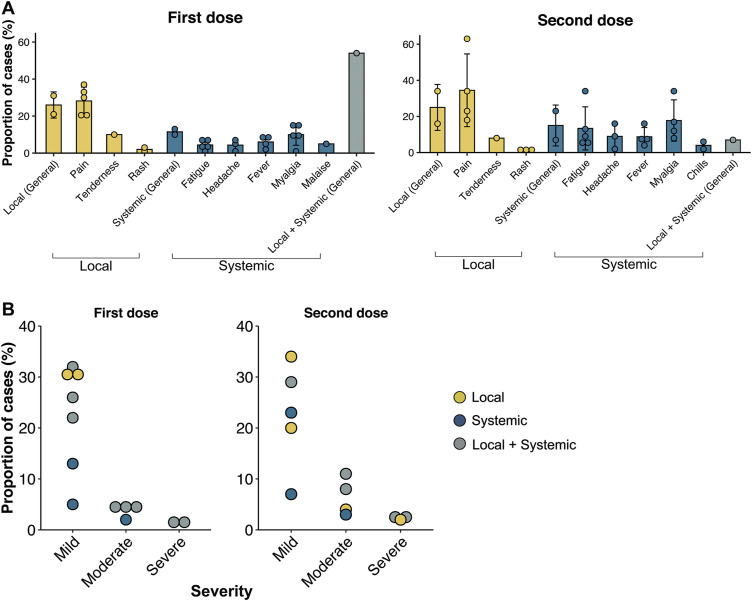

Toxicity data after vaccination with the BNT162b2 vaccine were available for seven studies [21,22,25,27,29,33,36], of which three studies contained patients with haematological malignancies [22,25,29] (CLL n = 167, MM/MPN n = 92), two studies with patients with solid tumour [21,36] (n = 366) and two studies with a mixed cancer population [21,27] (n = 351). One study included results from healthy controls (n = 54). Safety data of the mRNA-1273 and Ad26.COV.S vaccines were discussed in one study [33]. The safety profiles indicate similar experiences between patients with cancer and healthy controls with regard to local and systemic effects after partial and complete COVID-19 vaccination (Table 4 ). The overall local and systemic toxicities and severities after COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancer are shown (Fig. 2 ).

Table 4.

Local and systemic effects reported after partial (single dose) and complete (second dose) COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancer and healthy controls.

| Study | Vaccine(s) administered | Dose n | Toxicity |

Severity of toxicity |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local | Systemic | Local + systemic | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |||

| Goshen-Lago 2021 [21] | ||||||||

| Solid cancer | BNT162b2 | 1/2a | Pain (69%), warmness (9%), redness (8%) | Fatigue (24%), myalgia (13%), headache (10%) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Herishanu 2021 [22] | ||||||||

| CLL | BNT162b2 | 1 | 31% | 13%; fatigue (7%), headache (5%), fever (2%) | ·· | 31% (local), 13% (systemic) | ·· | ·· |

| 2 | 34% | 23%; fatigue (9%), fever (7%), chills (6%) | ·· | 34% (local), 23% (systemic) | ·· | ·· | ||

| Maneikis 2021 [25] | ||||||||

| Haematological cancer | BNT162b2 | 1 | ·· | Myalgia (10%), fatigue (7%), headache (7%) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| 2 | ·· | Fatigue (13%), headache (9%), myalgia (8%) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ||

| Monin 2021 [27] | ||||||||

| Mixed cancer | BNT162b2 | 1b | 21% | 10% | 54% | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| 2 | 16% | 7% | 7% | ·· | ·· | ·· | ||

| Healthy control | 1 | 30% | 10% | 22% | ·· | ·· | ·· | |

| 2 | 13% | 7% | 50% | ·· | ·· | ·· | ||

| Pimpinelli 2021 [29] | ||||||||

| MM/MPN | BNT162b2 | 1 | Pain (20%), tenderness (10%) | Malaise (5%), myalgia (1%), headache (1%) | ·· | 30% (local), 5% (systemic) | 2% (systemic) | ·· |

| 2 | Pain (18%), tenderness (8%) | Fever (4%), headache (2%), chills (2%) | ·· | 20% (local), 7% (systemic) | 4% (local), 3% (systemic) | 2% (local) | ||

| Thakkar 2021 [33] | ||||||||

| Mixed cancer | BNT162b2 | 1 | Pain (33%), rash (1%) | Myalgia (15%), fever (5%), fatigue (3%) | ·· | 26% | 5% | 2% |

| 2 | Pain (23%), rash (1%) | Myalgia (12%), fever (8%), fatigue (6%) | ·· | 29% | 8% | 2% | ||

| mRNA-1273 | 1 | Pain (37%), rash (3%) | Myalgia (15%), fever (8%), fatigue (1%) | ·· | 32% | 4% | 1% | |

| 2 | Pain (34%), rash (2%) | Myalgia (17%), fever (16%), fatigue (5%) | ·· | 23% | 11% | 3% | ||

| Ad26.COV2.S | 1 | Pain (30%) | Myalgia (9%), fever (9%), fatigue (4%) | ·· | 22% | 4% | ·· | |

| Waissengrin 2021 [36] | ||||||||

| Solid cancer | BNT162b2 | 1c | Pain (21%) | Fatigue (4%), headache (2%), myalgia (2%) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| 2d | Pain (63%), rash (2%) | Myalgia (34%), fatigue (34%), headache (16%) | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ||

CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; MM, multiple myeloma; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms.

Two patients were infected with COVID-19 immediately after the first dose. Twenty-four patients had elevated liver enzyme levels six weeks after the first dose. Five percent of patients undergoing computed tomography or positron emission tomography had newly documented regional lymphadenopathy.

One patient treated with checkpoint inhibitors was admitted to hospital with deranged liver function tests three weeks after the first dose.

Three patients (2%) died after the first dose, two due to disease progression and one due to COVID-19 infection.

Four patients (3%) were admitted to hospital, three for cancer-related complications and one due to fever; all were discharged after treatment.

Fig. 2.

Local and systemic toxicities reported after injection of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer. (A) Breakdown of specific local and systemic effects after partial (first dose) and complete (second dose) vaccination. (B) Breakdown of severity of side-effects exhibited after vaccination. Symptoms were assessed as per the following scale: mild (does not interfere with activity), moderate (interferes with activity) and severe (prevents daily activity). Each point indicates a study cohort where data were available; the error bars represent the SD of the mean for each category. SD, standard deviation.

4. Discussion

Currently, several COVID-19 vaccines have been granted emergency use authorisation by various national health agencies worldwide. Two mRNA-based vaccines, BNT162b2 produced by Pfizer-BioNTech (known as Comirnaty) and mRNA-1273 by Moderna (known as SpikeVax), have demonstrated significant effectiveness in enhancing immunogenicity against SARS-CoV-2 while maintaining an acceptable safety profile in the general population [37,38]. In addition, adenovirus-vector vaccines AZD1222 by Oxford-AstraZeneca (known as Vaxzevria) and Ad26.COV2.S by Janssen showed significant efficacy and safety based on ongoing clinical trials [39,40]. However, these data are unable to inform the unique responses in the cancer population, as most clinical trials have excluded immunocompromised people, including patients with active malignancies [13]. Thus, understanding the efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer is crucial to guide current vaccination programs.

A number of studies have indicated that patients with cancer are at a greater risk of COVID-19 infection and are more likely to develop severe or fatal complications as a result [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]. These might be due to a greater likelihood of comorbidities, disease-related immune dysregulation or treatment-induced immunosuppressive factors, which have also been shown to negatively affect immunogenicity among patients receiving vaccines, such as for seasonal influenza [[41], [42], [43]]. It is important to better understand the biological and clinical factors of patients with cancer affecting immunological responses to vaccines, especially for COVID-19 (see Table 5 ). These data may be critical in informing the clinical guidelines for the priority vaccination of patients with cancer against this disease [[44], [45], [46], [47]]. In the present review, we highlight clinical factors that affect seroconversion and indicate that the short-term safety profile of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer is safe, well-tolerated and consistent with the general population.

Table 5.

Summary of significant clinical factors affecting seroconversion outcomes after COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancer.

| Positive predictors for seroconversion | Negative predictors for seroconversion |

|---|---|

| Favourable disease-related factors | Older age |

| Naïve or time lapsed from active treatment [18,22,34] | Haematological malignancies [16,27,33] |

| Higher serum immunoglobulin levels at the time of vaccination [17,21,34] | Cytotoxic chemotherapy [16,17,26,28]

|

| Hormonal therapy [33] | Immunotherapy [26]

|

| Targeted therapy | |

| Active or progressive disease status [18,34] | |

| Immunoparesis [18,32] | |

| Lymphopenia [35] | |

| Increasing lines of treatment [34,35] | |

| Heightened pre-vaccination lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels [34] |

IgG, immunoglobulin G; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor-modified; HSCT, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation; BCL2, B-cell lymphoma 2; BTK, Bruton tyrosine kinase; JAK1/JAK2, Janus kinase 1/2; BCMA, B-cell maturation antigen.

4.1. Clinical factors associated with serological response to COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancer

4.1.1. Type of malignancy

Based on our analysis, serological response to COVID-19 vaccines within the patient population with cancer is significantly reduced in comparison with the healthy population. However, significant differences in response to vaccines are also observed based on the type of malignancy. In prospective studies that include both patients with haematologic and solid cancer, patients with haematological malignancies experience disproportionately lower seroconversion for anti-S IgG and reduced antibody titre relative to patients with solid tumours after COVID-19 vaccination. Addeo et al. [16] observed that 98% of patients with solid tumour were seropositive after completed two-dose series of the BNT162b2/mRNA-1273 vaccines, compared with 77% of patients with haematological malignancies (p = 0.002). Anti-S IgG antibody titre was also reduced after the first dose in patients with haematological cancer (median: 6 AU/mL) compared with that of patients with solid tumour (44 AU/mL; p = 0.018) and after the second dose (832 AU/mL in haematological malignancies versus 2500 AU/mL in solid cancers; p = 0.029). These observations are supported by findings from the study by Thakkar et al. [33], which highlighted blunted seropositivity in patients with haematological cancer (85%) compared with patients with solid tumour (98%; p = 0.001) and reduced IgG titres (median: 2528 AU/mL versus 7858 AU/mL; p = 0.013) after complete vaccination with the BNT162b2/mRNA-1273 vaccines. These data supporting differential immunological responses based on malignancy type are consistent with the outcomes after inoculation against seasonal influenza [42]. In general, patients with haematologic cancer experience greater immunosuppression, due in part to intrinsic frailty, disease-related immune dysregulation or by undergoing therapies that can lead to severe myelosuppression and lymphodepletion. These factors contribute to an increased risk of infection and mortality, in addition to poorer immunological responses to vaccination, suggesting that patients with haematological malignancies remain a high-risk patient population until effective vaccination or treatment strategies are available [9,48,49].

4.1.2. Cytotoxic chemotherapy

Cytotoxic chemotherapies can interfere with DNA replication, synthesis and cell cycle progression of rapidly proliferating lymphocytes during immune activation, leading to subsequent impairment of the host immune system [50]. Chemotherapy was identified as a significant confounder for poor seroconversion in the study by Palich et al. [28] of patients with solid tumour who were on active treatment after a single dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine (odds ratio [OR]: 4.34, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.67–11.30; p = 0.003). These observations are supported by findings from Barrière et al. [17], where patients with solid cancer undergoing chemotherapy experienced lower seroconversion (43%; p = 0.016) than patients who were chemotherapy-naïve (77%), after the first dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine. Reduced seroconversion was also noted in the study by Addeo et al. [16], where anti-S IgG titre was significantly lower in patients who received cytotoxic chemotherapy within six months of their first vaccination (median: 611 AU/mL; p = 0.019) than that in patients on clinical surveillance (2500 AU/mL) after a single dose of the BNT162b2/mRNA-1273 vaccines. Hydroxycarbamide treatment was also shown to blunt antibody response in patients with haematologic cancer (p = 0.018) in the study by Maneikis et al. [25] after two doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine. Given concerns of immunosuppression in patients undergoing chemotherapy affecting seropositivity, current challenges in the optimal timing of COVID-19 vaccination relative to chemotherapy regimens require further analysis to preserve efficacy and reduce risks in such patients [44]. Based on current data, it is recommended that patients scheduled for chemotherapy should receive vaccinations at least three weeks before the start of therapy or between treatment cycles [51,52].

4.1.3. Immunotherapy

Anti-CD20 (rituximab) therapy causes depletion of peripheral B-cells for at least four months after treatment [53] and has been shown to impair vaccination response against influenza or Streptococcus pneumoniae in patients with cancer [54]. Accordingly, Herishanu et al. [22] observed that none of 22 patients with CLL (0%) under anti-CD20 therapy within the last 12 months were seropositive after completed two-dose series with the BNT162b2 vaccine, whereas 46% of patients with CLL 12 months or greater post-anti-CD20 therapy showed response (adjusted OR: 37.6, 95% CI 2.2–651.3; p ≤ 0.001). Importantly, 18 of the 22 patients with CLL (82%) who were treated with anti-CD20 within 12 months from the study received it in combination with venetoclax. These observations are supported by the study by Re et al. [30], which found median anti-S IgG titre increase from 0 UI/mL in patients with haematologic cancer who underwent anti-CD20 therapy within 12 months to 6.7 UI/mL in patients who were 12 months post-anti-CD20 therapy (p = 0.002). Antibody response of the latter was not statistically significant from anti-CD20–naïve patients (16.8 UL/mL; p = 0.36) after a single dose of the BNT162b2/mRNA-1273 vaccines. In another study of patients with CLL, Roeker et al. [31] identified anti-CD20 treatment within 12 months as a significant clinical factor for poor antibody response post-second dose inoculation with the BNT162b2 vaccine (OR: 0.071, 95% CI 0.013–0.39; p = 0.002). Furthermore, Maneikis et al. [25] showed that active anti-CD20 therapy resulted in reduced median anti-S IgG antibody response to two doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine (median: 17 AU/mL; p < 0.001) compared with untreated patients with haematologic cancer (5761 AU/mL). Together, these findings indicate that recent anti-CD20 therapy (within 12 months of inoculation) is associated with poorer serological response after COVID-19 vaccination.

Plasma cell depleting anti-CD38 (daratumumab) therapy against MM has been previously associated with immunosuppression and heightened susceptibility to infections in treated patients [55]. This is due to a reduction in normal plasma cells after anti-CD38 treatment which leads to a decrease in polyclonal immunoglobulin levels essential for humoural immunity. In the study by Van Oekelen et al. [35], anti-CD38 treatment in patients with MM was associated with poor seroconversion after two doses of the BNT162b2/mRNA-1273 vaccines based on multivariate analysis with corrections (OR: 4.258; p = 0.005). Pimpinelli et al. [29] identified active anti-CD38–based therapy in patients with MM with reduced response (50%; p = 0.003) compared with anti-CD38–naïve patients with MM (93%) after inoculation with the BNT162b2 vaccine. Although these observations suggest that anti-CD38–based therapy may negatively affect humoural responses in the context of vaccination against SARS-CoV-2, it has been demonstrated that protective antibody induction remains intact for anti-CD38–treated patients with MM after inoculations for S. pneumoniae and influenza [56]. Further analysis is needed to identify potential causes for these observed differences, possibly due to biological variabilities produced by the different vaccine platforms (i.e. protein-based versus mRNA-based), by disease- or patient-specific factors or by differences in therapy regime during vaccine administration.

Other immunosuppressive therapies include chimeric antigen receptor-modified (CAR) T-cell therapy and haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Patients treated with CAR T-cell therapy, in particular CD-19-targeting, experience significant B-cell depletion that can persist for at least six months or longer with resultant hypogammaglobulinemia and heightened risk of infection [57]. In the case of HSCT recipients, extensive immunosuppression and treatment-related complications due to graft-versus-host disease have been shown to disproportionately affect susceptibility for infection and mortality to COVID-19 [58]. Accordingly, Thakkar et al. [33] identified reduced seroconversion in patients with cancer who were treated with CAR T-cell therapy (none of three patients [0%] responded; p < 0.001) or underwent HSCT (73%; p < 0.001) after the two-dose series of the BNT162b2/mRNA-1273 vaccines.

In general, serological responses are positively correlated with time lapsed from immunotherapy after reconstitution of humoural and adaptive immunity. Vaccination guidance for patients with planned B-cell depleting treatments (i.e. monoclonal antibody therapy, CAR T-cell therapy or HSCT) suggests that vaccines be offered at least two weeks before beginning treatment or at least three months after CAR-T cell therapy or HSCT to ensure adequate immune function [44,51,52].

4.1.4. Targeted therapy

Cancer-directed targeted therapies are designed to act on specific molecular pathways to prevent tumour cell growth and survival, but some of these pathways are also involved in the development, activation, differentiation and functioning of immune cells, thus ‘off-target’ immunomodulatory effects can be observed by select targeted agents [59].

B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitors (venetoclax) have been associated with cytopenia, specifically lymphopenia and neutropenia, and potential myelosuppression after treatment in patients with leukaemia, posing an increased risk for infection during the COVID-19 pandemic [60,61]. In the context of vaccination against SARS-CoV-2, generally poor immunological responses were observed for patients who received venetoclax. In addition to the results from patients with CLL with anti-CD20 and venetoclax combination, Herishanu et al. [22] found that only two of five patients with CLL (40%) with venetoclax monotherapy responded after two doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine and mounted a relatively low IgG response (range: 2.19–4.5 U/mL). Furthermore, patients with haematologic cancer receiving venetoclax monotherapy showed consistent findings of poor serological response after complete vaccination with the BNT162b2 vaccine in studies by Maneikis et al. [25] (median IgG: 4 AU/mL; p < 0.001), Roeker et al. [31] (seropositivity: seven of 44 patients [16%]) and Tzarfati et al. [34] (seropositivity: one of four patients [25%]; median IgG: 1.9 AU/mL).

Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKis) are increasingly used in the treatment of CLL and B-cell malignancies, granted the well-defined role of BTK in B-cell receptor signalling for the development, proliferation and survival of B-cell populations [62]. During BTK inhibition, impairment of humoural immunity is observed because of treatment-induced reduction of normal B-cells followed by decrease in serum IgG levels after 12 months [63]. Herishanu et al. [22] observed that only eight of 50 patients with CLL (16%) under active BTKi therapy responded to two doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine. Furthermore, significantly blunted seroconversion in patients with haematologic cancer actively treated with BTKis was identified in the studies by Maneikis et al. [25], where none of 44 patients (0%) were seropositive (median IgG: 0 AU/mL; p < 0.001), and Roeker et al. [31], who found that only 32% of BTKi-treated patients with CLL seroconverted and identified active BTKi therapy at the time of vaccination as a poor clinical factor for vaccination response (OR: 0.14, 95% CI 0.031–0.60; p = 0.009).

Janus kinase 1/2 inhibitors (ruxolitinib) have been shown to exhibit immunosuppressive properties by blocking signalling pathways of cytokine receptors, in addition to impairing dendritic cell potentiation and activation of T-cells [64]. In patients with haematologic cancer who were actively treated with ruxolitinib, Maneikis et al. [25] observed that these patients mounted blunted serological responses after complete vaccination with the BNT162b2 vaccine (median IgG: 10 AU/mL; p < 0.001).

B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)–targeted therapy is an emerging treatment modality for MM by targeting the overexpression and hyperactivation of BCMA in B-cells of patients with MM [65]. Poor antibody response to completed two-dose series of the BNT162b2/mRNA-1273 vaccines in patients with MM was significantly correlated with BCMA-targeted therapy (p < 0.001) in the study by Van Oekelen et al. [35]. Despite this, little is known about the immunosuppressive properties of BCMA-targeted therapies. Given that anti-BCMA therapies use immunotherapeutic platforms, such as bispecific antibody constructs, antibody–drug conjugates and CAR T-cells, one could expect that BCMA-targeted therapies may influence immunological outcomes similarly to immunotherapies. More in-depth analysis is required on this topic to identify biological factors related to anti-BCMA therapy and immunological responses to vaccines.

Current vaccination guidance provides no specific timing consideration for patients undergoing targeted therapies and suggests that patients should receive their vaccine at the earliest opportunity available [44]. Based on our review, several anticancer targeted therapies negatively affect humoural responses mounted by COVID-19 vaccination in actively treated patients. It is suggested that patients undergoing targeted therapies be monitored for protective antibody titres after immunisation to ensure sufficient coverage.

4.2. Evaluation of serological outcomes and high-risk patients with cancer

The overall serological response of patients with cancer after COVID-19 vaccination is positive, especially for patients with solid tumours, who are younger (<65 years), who are not undergoing active therapy, who have favourable disease-related factors and who have higher baseline serum immunoglobulin levels at the time of vaccination. However, these findings also highlight the importance of alternative prophylactics for high-risk patient cohorts who may not benefit from current vaccination programs. Recommendations procured by the Infectious Disease Society of America suggest that vaccinations during immunosuppressive states, including those administered during active chemotherapy, should not be considered valid doses unless an antibody titre level sufficient for protection is demonstrated [66]. Thus, patients with suboptimal vaccine responses represent a need for prospective studies to establish additional immunisation strategies to enhance coverage [49] (i.e. herd immunity, using different vaccine types or booster vaccinations) or alternative pharmacological (i.e. neutralising monoclonal antibodies [67]) and non-pharmacological interventions (i.e. mask-wearing, physical distancing) to mitigate the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

4.3. Short-term safety of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer

It is important to consider the safety of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with active malignancies, given their exclusion from earlier clinical studies. Overall, the short-term safety profile of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer appears to be consistent with previous findings in healthy populations [37,38,40]. Most local and systemic effects reported were mild to moderate in severity, with localised pain at the injection site, myalgia and fatigue being the most commonly reported. Across the seven studies analysed, adverse events related to elevated liver enzyme levels were documented in 24 patients [21], deranged liver function tests of unknown cause in one patient [27] and newly documented regional cervical or axillary lymphadenopathy in 5% of patients undergoing computed tomography or positron emission tomography scans during routine care [21]. No differences in the safety profiles of patients with cancer with haematological or solid malignancies were observed [27]. Patients undergoing active treatment showed no difference in side-effects experienced compared with those who were treatment-naïve [22], and those treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) did not experience any serious adverse events or additional side-effects in combination with immunotherapy after vaccination [36]. We believe that these data provide a safety signal for patients with cancer to receive a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as possible. Continued safety monitoring of patients with cancer with COVID-19 vaccines is required to fully assess the long-term effects on safety, in addition to ongoing disease and treatment progression for this population.

4.4. Limitations and future considerations

First, the limited number of patients included in each study may have adversely affected the power to distinguish differential responses between cancer cohorts and within cancer subgroups. Certain predictors of response may have been statistically insignificant because of the lack of statistical power to resolve them. We encourage collaborative efforts between institutions for large-scale studies to overcome the bias issues related to low-powered analyses. Second, while antibody-mediated responses to the vaccines may play a crucial role in immunity [68], evaluations into cellular immunity towards SARS-CoV-2 should also be considered [69]. Only two studies [23,27] included in this review examined T-cell responses after immunisation, and none were able to observe further adaptive immune responses because of the short timeframe. Furthermore, certain immunomodulating cancer-directed therapies, such as ICIs, may confer advantageous responses in mediating cell-based immunogenicity after vaccination [70]. Immunological memory is a hallmark of protective immunity after vaccination, and studies describing the effects of COVID-19 vaccines on memory B-cells and CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells in patients with cancer, especially after immunomodulating treatments, should be forthcoming [71]. Third, experimental differences may have impacted the robustness of the findings in this review, as studies used different assay platforms to quantify antibody responses, samples were collected at varying time points and the recruited patients and healthy controls may have been affected by convenience sampling biases. Fourth, efficacy data of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer against emerging variants of concern are limited, and partial immunogenic escape of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern has been observed in vaccinated individuals [72]. Furthermore, breakthrough of SARS-CoV-2 infection in fully vaccinated patients, particularly those with haematological malignancies, has been documented [24,25], thus emphasising the urgent need for additional prophylactic measures against infection for these high-risk populations. Finally, the effects of COVID-19 vaccines on paediatric, adolescent and young adult patients with cancer have not been sufficiently elucidated [73] and should be importantly considered.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this review sought to capture the most current data on the safety and immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer, to urgently inform cancer and public health communities regarding this important topic. Encouragingly, a number of clinical trials are already underway to assess the outcomes of patients with cancer who are receiving vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04865133, NCT04715438, NCT04746092). Once these data are available, they may allow us to better understand the effects of cancer and cancer-directed therapies in relation to immunogenicity and safety towards current and future vaccines. Our interim findings reinforce significant considerations for patients with cancer to be a high-priority subgroup for COVID-19 vaccination and emphasise the need for longer-term data. For high-risk patients, alternative prophylactic measures are urgently needed and strategies to optimise vaccination coverage should be thoroughly explored [49]. Continued vigilance towards public health measures should be exercised by patients with cancer, their caregivers and the general population at large, to better protect vulnerable populations from infection.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

S.T. contributed to Conceptualisation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft, and Visualisation. T.H.T. contributed to Validation and Writing – Review & Editing. A.N. contributed to Supervision and Writing – Review & Editing.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the Kids Cancer Care Foundation of Alberta and the Alberta Children's Hospital Foundation.

References

- 1.WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard 2021. https://covid19.who.int/

- 2.Scarfò L., Chatzikonstantinou T., Rigolin G.M., Quaresmini G., Motta M., Vitale C., et al. COVID-19 severity and mortality in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a joint study by ERIC, the European Research Initiative on CLL, and CLL Campus. Leukemia. 2020;34:2354–2363. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0959-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook G., John Ashcroft A., Pratt G., Popat R., Ramasamy K., Kaiser M., et al. Real-world assessment of the clinical impact of symptomatic infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (COVID-19 disease) in patients with multiple myeloma receiving systemic anti-cancer therapy. Br J Haematol. 2020;190:e83–e86. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuderer N.M., Choueiri T.K., Shah D.P., Shyr Y., Rubinstein S.M., Rivera D.R., et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31187-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hultcrantz M., Richter J., Rosenbaum C.A., Patel D., Smith E.L., Korde N., et al. COVID-19 infections and clinical outcomes in patients with multiple myeloma in New York city: a cohort study from five academic centers. Blood Cancer Discov. 2020;1:234–243. doi: 10.1158/2643-3230.bcd-20-0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mato A.R., Roeker L.E., Lamanna N., Allan J.N., Leslie L., Pagel J.M., et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with CLL: a multicenter international experience. Blood. 2020;136:1134–1143. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinato D.J., Scotti L., Gennari A., Colomba-Blameble E., Dolly S., Loizidou A., et al. Determinants of enhanced vulnerability to coronavirus disease 2019 in UK patients with cancer: a European study. Eur J Cancer. 2021;150:190–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rugge M., Zorzi M., Guzzinati S. SARS-CoV-2 infection in the Italian Veneto region: adverse outcomes in patients with cancer. Nat Can. 2020;1:784–788. doi: 10.1038/s43018-020-0104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robilotti E.V., Babady N.E., Mead P.A., Rolling T., Perez-Johnston R., Bernardes M., et al. Determinants of COVID-19 disease severity in patients with cancer. Nat Med. 2020;26:1218–1223. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0979-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saini K.S., Tagliamento M., Lambertini M., McNally R., Romano M., Leone M., et al. Mortality in patients with cancer and coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and pooled analysis of 52 studies. Eur J Cancer. 2020;139:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desai A., Gupta R., Advani S., Ouellette L., Kuderer N.M., Lyman G.H., et al. Mortality in hospitalized patients with cancer and coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cancer. 2021;127:1459–1468. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang W., Guan W., Chen R., Wang W., Li J., Xu K., et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corti C., Curigliano G. Commentary: SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:569–571. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barrière J., Gal J., Hoch B., Cassuto O., Leysalle A., Chamorey E., et al. Acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among French patients with cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:673–674. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curigliano G., Eggermont A.M.M. Adherence to COVID-19 vaccines in cancer patients: promote it and make it happen. Eur J Cancer. 2021;153:257–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Addeo A., Shah P.K., Bordry N., Hudson R.D., Albracht B., Di Marco M., et al. Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA vaccines in patients with cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrière J., Chamorey E., Adjtoutah Z., Castelnau O., Mahamat A., Marco S., et al. Impaired immunogenicity of BNT162b2 anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in patients treated for solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1053–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bird S., Panopoulou A., Shea R.L., Tsui M., Saso R., Sud A., et al. Response to first vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with multiple myeloma. Lancet Haematol. 2021;3026:19–21. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chowdhury O., Bruguier H., Mallett G., Sousos N., Crozier K., Allman C., et al. Impaired antibody response to COVID-19 vaccination in patients with chronic myeloid neoplasms. Br J Haematol. 2021;44:2. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fong D., Mair M.J., Mitterer M. High levels of anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in previously infected patients with cancer after a single dose of BNT 162b2 vaccine. Eur J Cancer. 2021;154:4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goshen-Lago T., Waldhorn I., Holland R., Szwarcwort-Cohen M., Reiner-Benaim A., Shachor-Meyouhas Y., et al. Serologic status and toxic effects of the SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in patients undergoing treatment for cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herishanu Y., Avivi I., Aharon A., Shefer G., Levi S., Bronstein Y., et al. Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2021 doi: 10.1182/blood.2021011568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrington P., de Lavallade H., Doores K.J., O'Reilly A., Seow J., Graham C., et al. Single dose of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 induces high frequency of neutralising antibody and polyfunctional T-cell responses in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01300-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heudel P., Favier B., Assaad S., Zrounba P., Blay J.-Y. Reduced SARS-CoV-2 infection and death after two doses of COVID-19 vaccines in a series of 1503 cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2021:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maneikis K., Šablauskas K., Ringelevičiūtė U., Vaitekėnaitė V., Čekauskienė R., Kryžauskaitė L., et al. Immunogenicity of the BNT162b2 COVID-19 mRNA vaccine and early clinical outcomes in patients with haematological malignancies in Lithuania: a national prospective cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00169-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Massarweh A., Eliakim-Raz N., Stemmer A., Levy-Barda A., Yust-Katz S., Zer A., et al. Evaluation of seropositivity following BNT162b2 messenger RNA vaccination for SARS-CoV-2 in patients undergoing treatment for cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monin L., Laing A.G., Muñoz-Ruiz M., McKenzie D.R., Del Molino Del Barrio I., Alaguthurai T., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of one versus two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b2 for patients with cancer: interim analysis of a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2021:1–14. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00213-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palich R., Veyri M., Marot S., Vozy A., Gligorov J., Maingon P., et al. Weak immunogenicity after a single dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine in treated cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2021:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pimpinelli F., Marchesi F., Piaggio G., Giannarelli D., Papa E., Falcucci P., et al. Fifth-week immunogenicity and safety of anti-SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in patients with multiple myeloma and myeloproliferative malignancies on active treatment: preliminary data from a single institution. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:81. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Re D., Barrière J., Chamorey E., Delforge M., Gastaud L., Petit E., et al. Low rate of seroconversion after mRNA anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with hematological malignancies. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021:10–13. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2021.1957877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roeker L.E., Knorr D.A., Thompson M.C., Nivar M., Lebowitz S., Peters N., et al. COVID-19 vaccine efficacy in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2021:21–23. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01270-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stampfer S.D., Goldwater M.S., Jew S., Bujarski S., Regidor B., Daniely D., et al. Response to mRNA vaccination for COVID-19 among patients with multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01354-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thakkar A., Gonzalez-Lugo J.D., Goradia N., Gali R., Shapiro L.C., Pradhan K., et al. Seroconversion rates following COVID-19 vaccination among patients with cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herzog Tzarfati K., Gutwein O., Apel A., Rahimi-Levene N., Sadovnik M., Harel L., et al. BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine is significantly less effective in patients with hematologic malignancies. Am J Hematol. 2021:1–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Oekelen O., Gleason C.R., Agte S., Srivastava K., Beach K.F., Aleman A., et al. Highly variable SARS-CoV-2 spike antibody responses to two doses of COVID-19 RNA vaccination in patients with multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waissengrin B., Agbarya A., Safadi E., Padova H., Wolf I. Short-term safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Lancet Oncol. 2021;2045:581–583. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00155-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voysey M., Clemens S.A.C., Madhi S.A., Weckx L.Y., Folegatti P.M., Aley P.K., et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021;397:99–111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sadoff J., Le Gars M., Shukarev G., Heerwegh D., Truyers C., de Groot A.M., et al. Interim results of a phase 1–2a trial of Ad26.COV2.S covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1824–1835. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ortbals D.W., Liebhaber H., Presant C.A., Van Amburg A.L., Lee J.Y. Influenza immunization of adult patients with malignant diseases. Ann Intern Med. 1977;87:552–557. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-87-5-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blanchette P.S., Chung H., Pritchard K.I., Earle C.C., Campitelli M.A., Buchan S.A., et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness among patients with cancer: a population-based study using health administrative and laboratory testing data from Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:2795–2804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ganz P.A., Shanley J.D., Cherry J.D. Responses of patients with neoplastic diseases to influenza virus vaccine. Cancer. 1978;42:2244–2247. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197811)42:5<2244::AID-CNCR2820420523>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Desai A., Gainor J.F., Hegde A., Schram A.M., Curigliano G., Pal S., et al. COVID-19 vaccine guidance for patients with cancer participating in oncology clinical trials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:313–319. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00487-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ribas A., Sengupta R., Locke T., Zaidi S.K., Campbell K.M., Carethers J.M., et al. Priority COVID-19 vaccination for patients with cancer while vaccine supply is limited. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:233–236. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corti C., Crimini E., Tarantino P., Pravettoni G., Eggermont A.M.M., Delaloge S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines for cancer patients: a call to action. Eur J Cancer. 2021;148:316–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garassino M.C., Vyas M., de Vries E.G.E., Kanesvaran R., Giuliani R., Peters S. The ESMO Call to Action on COVID-19 vaccinations and patients with cancer: Vaccinate. Monitor. Educate. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2021;32:579–581. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.01.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Passamonti F., Cattaneo C., Arcaini L., Bruna R., Cavo M., Merli F., et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with COVID-19 severity in patients with haematological malignancies in Italy: a retrospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e737–e745. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30251-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barrière J., Re D., Peyrade F., Carles M. Current perspectives for SARS-CoV-2 vaccination efficacy improvement in patients with active treatment against cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2021;154:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ménétrier-Caux C., Ray-Coquard I., Blay J.Y., Caux C. Lymphopenia in cancer patients and its effects on response to immunotherapy: an opportunity for combination with cytokines? J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0549-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gauci M.L., Coutzac C., Houot R., Marabelle A., Lebbé C. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines for cancer patients treated with immunotherapies: recommendations from the French society for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer (FITC) Eur J Cancer. 2021;148:121–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.ASH-ASTCT COVID-19 vaccination for HCT and CAR T cell recipients 2021. https://www.hematology.org/covid-19/ash-astct-covid-19-vaccination-for-hct-and-car-t-cell-recipients

- 53.Kneitz C., Wilhelm M., Tony H.P. Effective B cell depletion with rituximab in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Immunobiology. 2002;206:519–527. doi: 10.1078/0171-2985-00200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berglund Å., Willén L., Grödeberg L., Skattum L., Hagberg H., Pauksens K. The response to vaccination against influenza A(H1N1) 2009, seasonal influenza and Streptococcus pneumoniae in adult outpatients with ongoing treatment for cancer with and without rituximab. Acta Oncol (Madr) 2014;53:1212–1220. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.914243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nahi H., Chrobok M., Gran C., Lund J., Gruber A., Gahrton G., et al. Infectious complications and NK cell depletion following daratumumab treatment of multiple myeloma. PLoS One. 2019;14:1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frerichs K.A., Bosman P.W.C., Van Velzen J.F., Fraaij P.L.A., Koopmans M.P.G., Rimmelzwaan G.F., et al. Effect of daratumumab on normal plasma cells, polyclonal immunoglobulin levels, and vaccination responses in extensively pre-treated multiple myeloma patients. Haematologica. 2020;105:E302–E306. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.231860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hill J.A., Li D., Hay K.A., Green M.L., Cherian S., Chen X., et al. Infectious complications of CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell immunotherapy. Blood. 2018;131:121–130. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-07-793760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharma A., Bhatt N.S., St Martin A., Abid M.B., Bloomquist J., Chemaly R.F., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 in haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation recipients: an observational cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8:e185–e193. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30429-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vanneman M., Dranoff G. Combining immunotherapy and targeted therapies in cancer treatment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:237–251. doi: 10.1038/nrc3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Paul S., Rausch C.R., Jain N., Kadia T., Ravandi F., Dinardo C.D., et al. Treating leukemia in the time of COVID-19. Acta Haematol. 2021;144:132–144. doi: 10.1159/000508199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kumar S.K., Harrison S.J., Cavo M., de la Rubia J., Popat R., Gasparetto C., et al. Venetoclax or placebo in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (BELLINI): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1630–1642. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30525-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Good L., Benner B., Carson W.E. Bruton's tyrosine kinase: an emerging targeted therapy in myeloid cells within the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2021;70:2439–2451. doi: 10.1007/s00262-021-02908-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chong E.A., Roeker L.E., Shadman M., Davids M.S., Schuster S.J., Mato A.R. BTK inhibitors in cancer patients with COVID-19: “the winner will be the one who controls that chaos” (Napoleon Bonaparte) Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:3514–3517. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heine A., Held S.A.E., Daecke S.N., Wallner S., Yajnanarayana S.P., Kurts C., et al. The JAK-inhibitor ruxolitinib impairs dendritic cell function in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2013;122:1192–1202. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-484642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shah N., Chari A., Scott E., Mezzi K., Usmani S.Z. B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) in multiple myeloma: rationale for targeting and current therapeutic approaches. Leukemia. 2020;34:985–1005. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0734-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rubin L.G., Levin M.J., Ljungman P., Davies E.G., Avery R., Tomblyn M., et al. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58 doi: 10.1093/cid/cit684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taylor P.C., Adams A.C., Hufford M.M., de la Torre I., Winthrop K., Gottlieb R.L. Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies for treatment of COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:382–393. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00542-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hueso T., Pouderoux C., Péré H., Beaumont A.-L., Raillon L.-A., Ader F., et al. Convalescent plasma therapy for B-cell–depleted patients with protracted COVID-19. Blood. 2020;136:2290–2295. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020008423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sahin U., Muik A., Derhovanessian E., Vogler I., Kranz L.M., Vormehr M., et al. COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and TH1 T cell responses. Nature. 2020;586:594–599. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2814-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kang C.K., Bin Kim H.R.H., Song K.-H., Keam B., Choi S.J., Choe P.G., et al. Cell-mediated immunogenicity of influenza vaccination in patients with cancer receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:1902–1909. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dan J.M., Mateus J., Kato Y., Hastie K.M., Yu E.D., Faliti C.E., et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science. 2021;371:eabf4063. doi: 10.1126/science.abf4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Geers D., Shamier M.C., Bogers S., den Hartog G., Gommers L., Nieuwkoop N.N., et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern partially escape humoral but not T-cell responses in COVID-19 convalescent donors and vaccinees. Sci Immunol. 2021;6 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abj1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Revon-Riviere G., Ninove L., Min V., Rome A., Coze C., Verschuur A., et al. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in AYA with cancer: a monocentric experience. Eur J Cancer. 2021;154:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]