Abstract

COVID-19 has profound direct health consequences, however secondary effects were much broader as rates of hospital visits steeply declined for non-COVID-19 concerns, including myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke, with patients choosing to wait longer before symptoms convince them to seek medical attention. Thus, patients where ischemia leads to tissue loss should be a major concern.

Methods

The months of March to June 2019 and 2020 were compared to each other at 4 Denver area hospitals. Reduction in overall ED visits and an increase in patient refusal for emergency transport were clear in the data collected. During this period in 2019, 49 MI and 90 stroke patients were admitted. In 2020 this was 40 and 90 respectively. All were matched for age and gender. For MI patients ejection fraction and door to EKG and intervention times were measured. For stroke patients last known well time, time to evaluation, and modified Rankin scores were measured.

Results

254 (8.12%) patients refused emergency services transportation before the pandemic compared to 479 (18.35%) during the pandemic (p-value <0.001, chi square test). In the MI cohort, no significant difference was detected in measured ejection fraction (48% vs 49% p-value = 0.682). Additionally, no significant difference was detected between door to EKG time or door to MI intervention time. During the pandemic 8 (22%) expired with an MI prior to discharge, compared to 2 (4%) before the pandemic. The stroke cohort Door to Evaluation Time, Time since last well known, and modified Rankin scores were all found to have insignificant differences.

Discussion

ED volume was significantly lower during the early stages of the pandemic. During this time however only death from cardiac events increased, in spite of similar ejection fractions at discharge. The cause of this remains unclear as ejection fraction similarities make it less attributable to loss of tissue than to other factors. Patient behavior significantly changed during the pandemic, making this a likely source of the increase in mortality seen.

Keywords: COVID-19, Myocardial infarction, Stroke, Emergency service, Hospital, Public health

1. Introduction/background

In December 2019, the infectious respiratory disease COVID-19 emerged [[1], [2]]. COVID-19 is able to produce profound adverse health effects in infected individuals, however, less is known about the effects the COVID-19 pandemic has had on non-infected individuals.

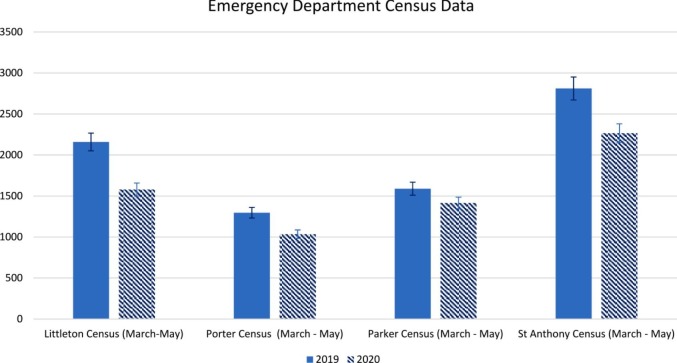

Several studies have shown that pandemic-related but infection-independent effects have led to broadly reduced patient visits to healthcare facilities for non-COVID-19 concerns. Myocardial infarction (MI) and ischemic stroke visits have declined compared to years prior [[3], [4], [5]]. Subsequent surveys sampling patient behavior have indicated fears surrounding COVID-19 as reasoning for this avoidance and delay in seeking care, with up to 12% avoiding urgent or emergent care [6]. Anecdotal reports from ED physicians consulted during study development suggest that while patient visits for non-COVID-19 events have gone down, the acuity of those visits has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Preliminary data gathered from four hospitals in the greater Denver area demonstrate this trend (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Emergency department overall census data from Littleton Adventist Hospital, Parker Adventist Hospital, Castle Rock Adventist Hospital, and St Anthony Hospital with 5% error bars.

Previous studies have demonstrated clear correlations between increased morbidity and mortality and delays in care [7]. This is especially true in ischemic pathologies where “time is tissue”. MIs and ischemic strokes were chosen to examine because any delays in care should reflect worse outcomes in these patient populations. The purpose of this study is to examine potential differences in care for MI and ischemic stroke during the pandemic compared to the year prior, specifically whether delays in care were occurring that may be deleterious to patient outcomes.

The first hypothesis was that there were delays in care during the pandemic, which was investigated by looking at Door to EKG Time, Door to Intervention Time, and Last Known Well Time (LKWT).

The second hypothesis was that delays in care during the pandemic contributed to worse outcomes for MI and ischemic stroke patients, as demonstrated by lower Ejection Fraction (EF) and Modified Rankin scores (mRS), respectively, as well as by higher rates of mortality.

2. Methods

This retrospective cohort observational study was conducted using patient data from four Centura Health Colorado hospitals (Littleton Adventist Hospital, Parker Adventist Hospital, Castle Rock Adventist Hospital, and St. Anthony's Hospital). The Institutional Review Board for Centura Health, the Catholic Health Initiatives Institute for Research and Innovation Institutional Review Board, approved the study protocol (IRB # 1649863–1). All patient information was de-identified before being provided to the investigators.

The population selected to analyze the effect of the pandemic on myocardial infarction (MI) and ischemic strokes were split into patients presenting in 2020 during the pandemic (between March 19th, 2020 to June 11th 2020) and a comparable 2019 pre-pandemic control group (between March 19th, 2019 and June 11th, 2019). The study sample was gathered through reports from EPIC generated for cardiac alerts and stroke alerts. Cardiac alert is defined as patients that meet the criteria for a STEMI with confirmed ST elevation and positive troponin. The protocols of the EMS department involved in this study is to transport any cardiac alert to the emergency department regardless of etiology. This includes both ACS and rhythm disturbances. Any patient that is transported to the emergency department is considered viable by ACLS criteria. Additionally, resuscitation efforts are not terminated during transport.

A stroke alert is patients that meet criteria for a potential stroke using the Cincinnati Stroke Scale. The inclusion criteria contained patients that were over the age of 18 with a final diagnosis of MI or ischemic stroke based on the final diagnosis report from EPIC. Patients excluded from the cohort were patients without adequate outcome measure data or who were concurrently COVID-19 positive.

To analyze patient behavior prior to arrival at a hospital, emergency medical service data from South Metro Fire Rescue was analyzed. Two measures were assessed to determine the differences between 2019 and 2020 patient activities, patient refusal to transportation to the hospital and time of transportation. The number of refusals were defined as patients for whom transportation to the hospital was recommended and the patient declined. The transportation times were defined as the time from initial patient contact to arrival at a hospital. The times were split into MI alerts and Stroke alerts, and the two measures were analyzed through two sample unequal variance t-tests.

For patients with MI the primary outcomes investigated were mortality and ejection fraction upon discharge. Additional measures analyzed included door to EKG time and door to primary intervention time. For patients with ischemic stroke, the primary outcomes investigated were mortality and Modified Rankin Scores (mRS) upon discharge. Additionally, door to stroke evaluation (NIHSS) time and last known well time (LKWT) to presentation time were calculated. The time since LKWT was calculated by comparing the time of admission with the estimated LKWT provided to emergency services by the caretakers of the patients. Mortality was determined through the final deposition column from the EPIC report.

MI and ischemic stroke mortality were analyzed through a calculated relative risk and direct comparison through fisher's exact test between cases that resulted in mortality versus survival. Measurable outcomes were compared using two sample unequal variance t-tests for direct comparison.

For the MI sample, 40 patients in 2020 and 49 patients in 2019 were examined for initial eligibility based on a cardiac alert. Two patients in 2020 were excluded from the sample due to a different final diagnosis, and one patient was excluded due to a COVID-19 diagnosis, resulting in 37 patients used in the final analysis. No patients were excluded from the 2019 sample as all met the inclusion criteria.

For the ischemic stroke analysis, 90 patients in 2020 and 90 patients in 2019 were initially examined for eligibility based on a stroke alert. 18 patients from the 2020 sample were excluded from analysis due to a different final diagnosis than ischemic stroke, and 23 patients from 2019 were excluded based on the same criteria. This resulted in a final sample size of 59 patients for 2020 and 52 patients for 2019.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

The final sample selected for MI analysis in the pre-pandemic control group had a mean age of 66 (size = 49, standard deviation = 13.2, 30 males and 19 females) and are comparable to the pandemic experimental group with a mean age of 67 (size = 37, standard deviation = 14, 26 males and 11 females). The final sample selected for ischemic stroke analysis pre-pandemic had a mean age of 74 (size = 52, standard deviation = 15.3, 23 males and 29 females) and are comparable to pandemic experimental group with a mean age of 69 (size = 59, standard deviation = 17.5, 30 males and 29 females). Using fisher's exact test for statistical analysis allows the groups in each cohort to be directly compared despite the discrepancy in sample size. Since the cohorts selected for analysis were pulled from the same months of the year and are similar in age and gender ratios it can be assumed that the patient samples have similar co-morbidities.

3.2. Pre-hospital emergency transport

After consultation from emergency services, 254 (8.12%) patients refused transportation in 2019 compared to 479 (18.35%) in 2020 (Table 1 ). This indicates a significant increase in the amount of refusals during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the year previous (p-value < 0.001, chi square test).

Table 1.

Refusal of emergency services.

| Transports | Refusals | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Pandemic (March 19th, 2019 and June 11th, 2019) | 2875 | 254 | p-value <0.001 |

| During Pandemic (March 19th, 2020 to June 11th 2020) | 2131 | 479 |

When comparing transportation times, no major difference was found for both MI and stroke alerts (Fig. 2 ). The MI alerts had a mean of 20.09 min in 2019 compared to a mean of 20.68 min in 2020 (95% CI (−3.897, 2.712), p-value = 0.7203). The stroke alerts had a mean of 21.78 min in 2019 compared to a mean of 20.59 min in 2020 (95% CI (−0.763, 3.140), p-value = 0.231).

Fig. 2.

Transportation times from patient contact to arrival at hospital.

3.3. Mortality

Of the patients presenting with an MI during the pandemic, 8 (22%) expired prior to discharge, compared to 2 (4%) patients pre-pandemic (Table 2 ). Therefore, patients who presented to the ED with a cardiac alert and a final diagnosis of myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic had a 3.60 times increased risk of mortality when compared to pre-pandemic samples (p-value 0.017, fisher's exact test). In the ischemic stroke cohort, during the pandemic 4 (6.79%) expired prior to discharge, compared to 11 (21.15%) of patients in the previous year (Table 2). The relative risk of 0.299 indicates a negative relationship (p-value 0.049, fisher exact test).

Table 2.

Incidence rates and relative risk for MI and ischemic stroke mortality.

| Survival to discharge | Expired | Relative risk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MI Pre-Pandemic (March 19th, 2019 and June 11th, 2019) | 47 | 2 | 3.60 |

| MI During Pandemic (March 19th, 2020 to June 11th 2020) | 29 | 8 | 95% CI (1.35, 44.18) |

| Ischemic Stroke Pre-Pandemic (March 19th, 2019 and June 11th, 2019) | 41 | 11 | 0.299 |

| Ischemic Stroke During Pandemic (March 19th, 2020 to June 11th 2020) | 55 | 4 | 95% CI (0.076, 0.958) |

3.4. Quantitative data for MI and ischemic stroke

In patients that survived to discharge, the 2019 sample had an average ejection fraction of 48.02% and the 2020 sample had an average ejection fraction of 49.33%. No significant difference was detected in measured ejection fraction (95% CI (−0.077, 0.050), p-value = 0.682, unequal variances t-test). Additionally, no significant difference was detected between door to EKG time or door to MI intervention time between the 2019 and 2020 data sets (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Ejection fraction, door to EKG time, and door to MI intervention time comparisons, modified rankin score, door to evaluation time, and time since LKWT comparisons.

The additional outcome studied of mRS was also found to have an average of 2.37 in 2019 and an average of 2.45 in 2020. This difference was found to be insignificant, with patients who survived to discharge having comparable mRS (95% CI (−0.786, 0.616), p-value = 0.8103, unequal variances t-test). The measures of Door to Evaluation Time and the calculation of Time Since LKWT were also found to not be significantly different (Fig. 3).

4. Discussion

Multiple studies have demonstrated significant changes in patient behavior as it pertains to seeking care. In general, individuals have avoided or delayed seeking both routine and emergency care during the COVID-19 pandemic [6]. Fig. 1 shows that the same is also true in this data set. The overall census of all patients presenting to the emergency department was lower in 2020 than in 2019. Additionally, the amount of MI patients that presented to the emergency department in 2020 was lower than in 2019. Despite the decrease in overall number of patients, more patients expired in 2020 from MIs. Ischemic processes in highly metabolically active tissues like the heart cause irreversible damage within minutes. Time to reperfusion therapy is the chief determinant of outcomes in MI patients. Fig. 2, Fig. 3 demonstrate that there was no significant difference in delivery of care to patients between 2019 and 2020 in all key timing metrics.

Any attributable difference in the treatment of MI would have had to occur due to changes in patient behavior prior to arrival of EMS or presentation to the emergency department. This is supported by the data from Table 1, with a significantly larger number of patients refusing emergency transport to the Centura hospitals. It is notable that there were no observed changes in delivery of care for MI or ischemic stroke patients between 2020 and 2019. These results support the hypothesis that prehospital delays in care in MI patients resulted in increased mortality, despite the standard of care being unchanged.

Unlike MI patients, ischemic stroke patients were not found to have an increased risk of mortality. The exact reason for the difference in mortality is complex and likely related to the significant collateral circulation in the brain. The discrepancy between mortalities poses an interesting question that will need to be further investigated.

Overall, it stands to reason that the increase in mortality in MI patients is related to prehospital refusals for transport and delays in seeking care. Exploration into the exact cause of this increase in mortality has major implications for both the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and potential future public health emergencies.

4.1. Future directions

While time from symptom onset to intervention is a major predictor of outcome, there are also other variables that could contribute to worse outcomes. It has been noted that chronic stress correlates with increased risk of cardiovascular events [8]. Studies have also shown higher levels self-reported stress during the pandemic, as well as increased symptoms of stress, such as alcohol consumption and substance abuse [9]. Exploring this potential influence on outcomes for patients has important implications for future pandemics or widespread crises.

5. Conclusion

Our investigation of transport and census data from emergency services demonstrates that patients were underutilizing transport services. Combined with census data from emergency departments in the same jurisdiction, there was a measurable change in patient behavior in during the studied time period.

Declarations of interest

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Christian Clodfelder: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Spencer Cooper: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Jeffrey Edwards: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Joshua Kraemer: Writing – original draft. Rebecca Ryznar: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Anthony LaPorta: Writing – review & editing. Mary Meyers: Data curation. Ryan Shelton: Data curation. Susan Chesnick: Data curation.

References

- 1.Kamps B., Hoffmann C. 2nd ed. Steinhauser Verlag; Hamburg, Germany: 2020. COVID reference; pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC COVID Data Tracker Centers for disease control and prevention. March 11, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#demographicsovertime Accessed March 13, 2021.

- 3.Wong L., Hawkins J., Langness S., Murrell K., Iris P., Sammann A. 2020. Where are all the patients? Addressing Covid-19 fear to encourage sick patients to seek emergency care | Catalyst non-issue content.https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0193. Accessed July 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC COVID-19 Response Team Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) - United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 27 Mar. 2020;69(12):343–346. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartnett K.P., Kite-Powell A., DeVies J., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits — United States, January1, 2019–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:699–704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czeisler M.É., Marynak K., Clarke K.E.N., et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19–related concerns — United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1250–1257. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger P., Ellis S., Holmes D., Granger C., Criger D., Betriu A., et al. Relationship between delay in performing direct coronary angioplasty and early clinical outcome in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1999;100(1) doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedersen L.R., Frestad D., Michelsen M.M., Mygind N.D., Rasmusen H., Suhrs H.E., et al. Risk factors for myocardial infarction in women and men: a review of the current literature. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(25):3835–3852. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160309115318. 26956230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czeisler M.É., Lane R.I., Petrosky E., Wiley J.F., Christensen A., Njai R., et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic – United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Aug 14;69(32):1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. 32790653 PMC7440121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]