Abstract

Acellular cornea derived hydrogels provide significant advantages in preserving native corneal stromal keratocyte cells and endothelial cells. However, for clinical application, hydrogel physical properties need to be improved, and their role in corneal epithelial wound healing requires further investigation. In this study, an acellular porcine corneal stroma (APCS) hydrogel (APCS-gel) was successfully prepared from 20 mg/ml APCS, demonstrated optimal light transmittance and gelation kinetic properties and retained critical corneal ECM of collagens and growth factors. Compared with fibrin gel, the APCS-gel had a higher porosity ratio and faster nutrition diffusion with an accompanying improvement in the proliferation of primary rabbit corneal epithelial cells (RCECs) and stromal cells (RCSCs). These corneal cell types also displayed improved viability and cellular infiltration. Furthermore, the APCS-gel provides significant advantages in the preservation of RCECs stemness and enhancement of corneal wound healing in vitro and in vivo. After 7 days of culture, 3–4 layers of RCECs were formed on the APCS-gel in vitro, while only 1–2 layers were found on the fibrin gel. More corneal stem/progenitor cell phenotypes (K12-, p63+, ABCG2+) and proliferation phenotypes (Ki67+) were detected on the APCS-gel than fibrin gel. Using a corneal epithelial wound healing model, we also found faster reepithelization in corneas that received APCS-gel compared to fibrin gel. Additionally, our APCS-gel demonstrated better physical and biological properties when compared to Tisseel, a clinically used type of fibrin gel. In conclusion, our APCS-gel provided better corneal epithelial and stromal cell biocompatibility to fibrin gels and due to its transparency and faster gelation time could potentially be superior for clinical purposes.

Keywords: Corneal ECM, hydrogels, acellular porcine corneal stroma, cellular proliferation, corneal wound healing

1. Introduction

Loss of corneal function by either disease or injury is the fourth leading cause of blindness in the world [1]. Corneal diseases or injuries in which there is deep corneal stroma damage may result in corneal perforation and impaired vision [2]. While there are a number of treatments for these significant corneal stromal conditions, including corneal transplantation or amniotic membrane, each of these potential therapies has limitations.

Corneal transplantation is a highly invasive procedure requiring donor tissue and is the current primary treatment of many corneal diseases. However, corneal transplant success is limited by the possibility of rejection, and the rate of this corneal rejection is higher in many acute corneal ailments. Moreover, the availability of corneal donor tissue may be limited and globally there is not enough corneal tissue access [3]. One of the most common alternative treatments for cornea transplantation is the application of amniotic membranes (AM), which is usually sutured as a scaffold to cover the corneal wound and serve as a substrate for corneal epithelial cell regeneration [4]. However, as a semitransparent membrane, the AM may decrease vision temporarily before it is completely degraded or removed [5]. Furthermore, the sutures used for AM placing may cause further injury and induce complications such as neovascularization [6]. Finally, being a thin membrane, the AM is more difficult to manipulate and filling irregular cornea stromal wounds completely is challenging. These problems are especially exacerbated when immediate treatment is needed to prevent further complications in severe corneal trauma, infection, or inflammation. Some tissue adhesives, such as isobutyl cyanoacrylate or fibrin gel used in the clinic, could rapidly and temporarily fill the small irregular corneal wounds without suture requirement [6]. However, cyanoacrylate showed corneal cytotoxicity [7, 8] and fibrin gel, as a semitransparent biomaterial, may decrease corneal transparency and may potentially induce unwanted angiogenesis [9, 10]. Recently, a synthetic biomaterial, CLP-PEG-fibrinogen LiQD Cornea [11], which made by the short collagen-like peptide (CLP) conjugated to multifunctional polyethylene glycol (PEG) and mixed with fibrinogen, and could polymerized in situ after injection, demonstrated promising result as a corneal stromal substitution in rabbit cornea defect. However, biocompatibility experiments in the corneal cells are required to demonstrate their preclinical value.

With the improvement of decellularization methods, various extracellular matrix (ECM) hydrogels have been developed. They have the advantage of retaining similar components as the native cornea and could be injected and fill in the irregular wound when used in their soluble phase (sol). Under a physiological environment, such as pH, salt concentration, or human body temperature, these hydrogels become a non-soluble gel and undergo sol-gel transition. Moreover, the ECM hydrogels showed excellent cellular biocompatibility by mimicking native microenvironments [12]. Recently, several extracellular matrix hydrogels derived from numerous tissues have been widely applied in tissue repair in preclinical animal models [13–15]. Once such promising material is a porcine-derived myocardial ECM hydrogel, which has recently been used in a clinical trial for post-myocardial infarction patients. This hydrogel successfully facilitates cell proliferation and tissue recovery by supporting a myocardial-specific extracellular microenvironment [16]. Two corneal acellular derived hydrogels have also been developed and showed that cornea ECM hydrogel has significant advantages in preserving native corneal keratocyte phenotypes and improvement of the corneal keratocytes and endothelial cells proliferation [17, 18]. However, the low optical transmittance and/or slow kinetic gelation has limited their clinical application and further studies regarding biocompatibility with corneal epithelial cells are needed.

In our previous research, an acellular porcine corneal stroma (APCS) has been prepared as a scaffold that retains most corneal ECM, such as 91% of collagens and 80% of proteoglycans. This APCS also showed high light transmittance similar to the native cornea, and no cytotoxicity effects were observed [19]. Furthermore, it demonstrated significant advantages in the corneal stem cell marker expression, while demonstrating effects on the rapid regeneration of corneal epithelium [20–22]. In our current study, a corneal ECM hydrogel (APCS-gel) derived from the APCS was further developed by preserving the corneal ECM characteristics. Compared to the native porcine cornea (NPC), fibrin gel or Tisseel, the APCS-gel maintains high transparency and shows an improved kinetic gelation period. With further optimization this APCS-gel may have clinical utility for corneal diseases, and the more general approach used to make this hydrogel might be used in other tissues.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Female and male CD-1mice (aged 8–12 weeks and weighing 25–38g) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee from the University of Illinois-Chicago, in compliance with US NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, guidelines of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and the ARRIVE guidelines.

2.2. Cells preparation and culture

Primary rabbit corneal epithelial cells (RCECs) or rabbit corneal stromal keratocyte cells (RCSCs) were obtained from New Zealand white rabbits as previously reported [23, 24]. In short, rabbit corneal limbal tissue or rabbit corneal stromal explants of 1 mm2 were trephined and incubated in a 100 mm culture dish with corneal epithelial medium [24] or corneal stromal cell medium (DMEM medium containing 10% calf serum) [23] respectively. Both media also contain 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

2.3. APCS-gel preparation

APCS was prepared from the native porcine cornea (NPC), as described previously [19]. In short, NPC was freeze dried (Labconco, USA), powdered by a freezer-mill (SPEX, USA), and filtered through a 40-mesh screen. Comminuted acellular corneal stoma powder ranging from 10–30 mg was separately enzymatically digested in 8 mg/ml porcine pepsin (P7000, ≥250 unites/mg, Sigma) at 0.01N HCl with shaking for 48 h at 25 °C. The obtained APCS digest solutions were frozen until use. Gelation was induced by neutralizing the pH and salt concentration at 4°C followed by warming to 37 °C. In detail, pH neutralization was accomplished by adding one-tenth of the digest volume of 0.1 N NaOH, and the salt concentration was adjusted by one-ninth the volume of 10x PBS. After that, the neutralized digest (APCS-sol) was placed in a non-humidified incubator heated to 37 °C until the acellular porcine corneal stromal hydrogel (APCS-gel) was formed. As a control to compare the characteristics of the APCS-gels, fibrin gels were prepared with final concentrations of 7.4 mg/ml fibrinogen and 5.4 U/ml thrombin as previously reported [25, 26]. Additionally, a commercial fibrin gel, Tisseel (Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Deerfield, IL, USA) was also included which was produced by fibrinogen (67–106 mg/ml) and thrombin (400–625 IU/ml) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.4. Turbidimetric gelation kinetics

The gelation kinetics of 100 μl APCS-sol, fibrin gel or Tisseel in 96-well plates were evaluated turbidimetrically and all kinetic parameters derived were recorded for comparisons and samples were run in triplicate. APCS-sol at all concentrations were prepared on ice. For each concentration, 100 μl APCS-gel/well was added in triplicate in 96-well plates respectively. The 100 μl of fibrin gel or Tisseel was prepared in the well directly. After all samples were prepared, the plate was immediately read spectrophotometrically in a microplate reader (Synergy HT, Microplate Spectrophotometer, Biotek, USA) pre-heated to 37°C. Absorbance at 405 nm was measured every 2 min for 60 min and the kinetic curves were recorded. The results of lag time (tlag) were automatically defined by the plate reader. According to the kinetic curve as the intercept of the linear region of the gelation curve between 0% and 100% absorbance, the time to half gelation (t1/2) was calculated as previously reported and defined as the time to 50% absorbance [13].

2.5. Light transmittance

The transparency of the APCS-gel, fibrin gel, or Tisseel was evaluated by adding 100 μl of each solution per well in a flat bottom 96-well tissue culture plate. First, the pH and salt concentration of APCS-gel were neutralized to ensure a gel state, then it was added to the well. The fibrin gel or Tisseel was prepared directly in the well. After this the culture plate was incubated at 37 °C for one hour and the light absorbance at several different wavelengths ranging from 300 to 700 nm was measured by using a microplate reader (Synergy HT, Microplate Spectrophotometer, Biotek, USA). As an additional control, a 6 mm diameter native pig corneal (NPC) was pre-cut using a trephine, placed in a well and immersed into 100 μl PBS. By inverting the absorbance reading, the light transmittance was calculated. After the measurements, all the samples were imaged to obtain a visual representation of the difference in transparency.

2.6. Analysis of protein content by electrophoresis and mass spectrometry

The protein content of APCS-gel produced from different concentrations of APCS was assessed by SDS-PAGE. The protein concentration of all samples was measured first by BCA assay. Then 2.5 ug protein of each sample was run on a NuPAGE Novex Bis-Tris gel at 12% w/v in NuPAGE MOPS SDS running buffer (Invitrogen) by using rat tail collagen type I and pepsin as controls. The gels were stained with Coomassie blue staining solution for 2 hours and washed to destain the background before imaging. For mass spectrometry (MS) analysis, APCS and APCS-gel samples (n=2) were solubilized as previously reported [27]. The samples were run on a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive HF Hybrid Quadruple-Orbitrap mass spectrometer coupled with an Ultimate 3000 NanoLC system utilizing a UHPLC column (15cm × 75μm ID, Zorbax 300SB-C18, Agilent) at the Mass Spectrometry Core of University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). A 120 minute linear gradient (0–35% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) was used for separation of peptides, and the raw MS data were acquired in a data dependent mode, in which top 10 intense peaks of every full MS scan with charge state ≥ 2 were fragmented in HCD collision cell with normalized collision energy of 28%. Full MS scans were acquired in the mass analyzer over m/z 350 – 1800 range with resolution 30,000 (m/z 400). Preliminary processing of the raw data was performed by the UIC Research Informatics Core using OpenMS FeatureFinderIdentification tool. Raw files were converted into .mgf files using MSConvert (ProteoWizard). Database search was carried out using Mascot server version 2.6.2 (Matrix Science), with following parameters: mass tolerance 10 ppm for precursor ions and 100 mmu for fragment ions; two missed cleavages were allowed; fixed modification was carbamidomethylation of cysteine; and variable modifications were oxidized methionine, deamidation of asparagine, pyro-glutamic acid modification at N-terminal glutamine, and hydroxylation of lysine and proline. Only peptides with a Mascot score ≥25 and an isolation interference ≤30 were included in the data analysis. The count of peptide spectral matches (PSMs) and total intensity of extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) for all peptides detected for each sample, were calculated separately [28]. The PSM counts and EIC intensities were summarized for each protein with at least 2 detected peptides and annotated using a custom script. Annotations included both gene information, fetched via the Uniprot application programming interface, as well as Matrisome annotations [29]. All ECM proteins were categorized into six major groups: proteoglycans, glycoproteins, collagens, ECM regulators, ECM-affiliated proteins and secreted factors [30]. The annotated protein of each sample was recorded, and all proteins between APCS and APCS-gel were compared.

2.7. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The surface of APCS-gel, fibrin gel or Tisseel were examined by SEM. First, the APCS-gel, fibrin gel and Tisseel were fixed in cold Karnovsky’s Fixative liquid for 2 hours at 4°C, and then they were rinsed with ultraclean water. Samples were immersed in liquid nitrogen and placed quickly in a lyophilizer for 24 hours. Then, all samples were fixed for observation by carbon tape and metallized prior to observation. Three scanning electron micrographs of each sample (n=3) were obtained at magnification of both 1000 x and 5000 x. Each SEM image was analyzed according to our previous report [23]. In short, the contrast of each grayscale image was balanced using Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, CA), then each image was analyzed with the Image J (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) built-in function of “analyze particles” to calculate the pore area (A0). Then, the sum of the areas of the pores was divided by the total exposed sample area to obtain percent porosity [23, 31].

2.8. Assessment of permeability

The permeability analysis was performed for both APCS-gel, fibrin gel or Tisseel. APCS-gel, fibrin gel or Tisseel (100 μl) was added to a transwell with a barrier at the bottom, then inserted into a 24 well culture plate. Then, 200 μL of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 0.15% (w/v) phenol red was added to the transwell and 1ml of phenol red-free DMEM into the receiver plate. Then 100 μl DMEM was extracted from the receiver plate every 6–12 hours until 48 hours for analysis. The optical density of the extracts at each time point was measured to quantify the amount of phenol red by using a spectrophotometer (Synergy HT, Microplate Spectrophotometer, Biotek, USA) with an excitation wavelength of 558 nm and an emission of 570 nm. The incubation process was performed at 60% relative humidity and at 25°C.

2.9. Cell infiltration quantification of APCS-gel

The infiltration analysis was measured by seeding 105 RCSCs on the surface of the APCS-gel or fibrin gel. After 5 and 10 days in culture (n=3), cell infiltration quantification was measured on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained by gel sections. At each time point, APCS-gel, fibrin gel and Tisseel were fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, embedded in paraffin, then sectioned. Three fields (10 x) of gels cross sections spanning the entire gel surface were imaged, and the cell infiltration distance from the surface was quantified. Ten measurements of the maximum cell infiltration distance were taken at evenly spaced intervals across each image by using Image J software, and the values were averaged. The maximum infiltration distance was defined as the greatest distance cells migrated from the surface (mm) of each sample.

2.10. Cytotoxicity assay

To test the cytotoxic effects, the 1 ml of APCS-gel, fibrin gel or Tisseel was immersed in 10 ml corneal epithelial medium or corneal stromal cell medium. After 24 hours at 37 °C in the tissue culture incubator, APCS-gel, fibrin gel and Tisseel were removed respectively, and the remaining media were stored at 4 °C. For the cytotoxicity assay, primary RCECs (1×103) or RCSCs (1×103) were seeded into 96-well plates and cultured with these media that were incubated with hydrogels, fibrin or Tisseel [24, 32]. Each experiment was done in triplicate. After 1, 3, 5, and 7 days, the proliferation activity of the cells was quantitatively determined by MTT assay. The optical density (OD) of absorbance at 490 nm was measured by a microplate reader (Synergy HT, Microplate Spectrophotometer, Biotek, USA).

2.11. In vitro cell culture and viability

The effects of APCS-gel, fibrin gel or Tisseel on cellular viability was evaluated by seeding 105 RCECs or RCSCs on or within 100 μl of APCS-gel, fibrin gel or Tisseel respectively. All samples were allowed to reach the gel phase by incubating the preparation at 37 °C for 15 minutes. The RCECs or RCSCs were cultured in corneal epithelial medium or corneal stromal cell medium respectively. The media were changed every 3 days. After 7 days of culture, the cell viability on the surface or within APCS-gel, fibrin gel or Tisseel was determined by using the Live/Dead assay (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, the cell-seeded samples were stained by Calcein AM and ethidium homodimer-1 for 1h at 37°C. Then all samples were observed after the unbound dye was washed by PBS three times. The total or single live/dead cells area was measured by the built-in function of Image J analyze particles [13]. After the single live/dead cell area was averaged from ten measurement of live/dead cells, the ratio of the live/dead cells was calculated for both groups.

2.12. Evaluation of cellular proliferation and differentiation.

In these experiment, 105 RCECs cell suspension on corneal epithelial medium were seeded on the surface of 100 μl APCS-gel, fibrin gel or Tisseel, or culture wells using 96 tissue culture plate. The corneal epithelial medium was replaced with new media every other day as previously reported [24]. After 3 and 7 days, the RCECs proliferation capacity was determined by evaluating the increase of cellular DNA content, quantified by the CyQUANT Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) (n=3). Briefly, RCECs were lysed by the addition of the lysis buffer containing the green fluorescent dye, CyQUANT GR, which binds to nucleic acids. After incubation, the fluorescence levels were read on a fluorescent microplate reader with filters for 485 nm excitation and 538 nm emission, the results provide a value for the cellular DNA content [33]. In order to evaluate the cellular proliferation and differentiation phenotypes, samples of 7 days cultures were immunostained with corneal epithelial cells specific marker (K12), potential limbal stem cell marker (P63) and proliferation marker (Ki67) (n=3). The samples were fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, then embedded within OCT for cryosection. For immunofluorescence staining the antibodies and dilutions were K12 (1:100; Millipore), P63 (1:50, Millipore), and Ki67 (Abcam ab8191; 1:100). The secondary antibodies included Alexa Fluor 594 IgG (Invitrogen, A11012; 1:100) and Alexa Fluor 488 IgG (Invitrogen A11001; 1:10000). The images were obtained by using a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM 710 META; Carl Zeiss).

2.13. Corneal wound healing assays

The effect of APCS-gel, fibrin gel or Tisseel on the wound healing response of injured corneas was evaluated by using 12 weeks old CD1 mice (n=3) that were anesthetized by using a mix of ketamine/xylazine and subjected to a circular 2 mm region of central corneal epithelium debridement. Each mouse received the procedure only in the right eye, the corneal epithelium and basement were completely removed by using a sharp # 15 surgical blade. The procedure was performed under a surgical microscope (Carl-Zeiss S88, Oberkochen, Germany). Immediately after that, the wounded area received implantation of 1 μl of APCS-gel, fibrin gel, Tisseel or PBS that covered the entire debrided area. After 15 minutes of the gelation period, a tarsorrhaphy was performed to avoid the detachment of the gels. All corneas were monitored for signs of infection and inflammation. The corneal epithelium wound healing was evaluated by slit-lamp photography and the wound healing area was measured by Photoshop CS4 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA) [34].

2.14. Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS Statistics, IBM, Armonk, NY). All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and the significance of differences was evaluated by using ANOVA followed by post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was defined as P< 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. The physical properties of APCS-gel and fibrin gel

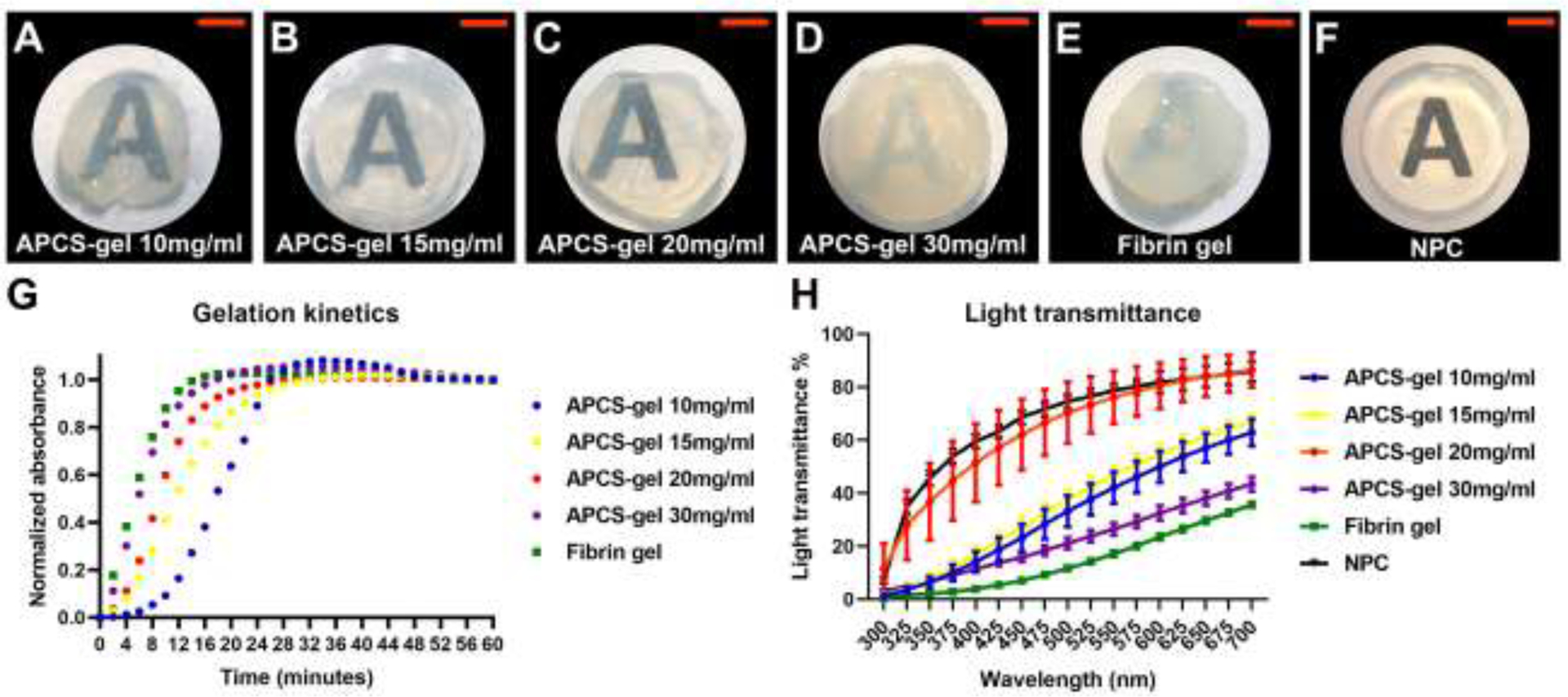

The soluble APCS-sol was successfully prepared from the APCS using the procedure described above. The APCS-sol maintained its liquid phase at 4°C and could be injected through an 18G syringe needle. When the APCS-sol was incubated at 37°C, it polymerized and underwent the sol-gel transition. After gelation, the resulting APCS-gel showed a rigid structure and defined edges, which could be handled or manipulated easily with forceps (Fig. 1A–D). The macroscopic analysis shows that all APCS-gel demonstrated higher light transparency than the fibrin gel (Figure 1E), and the APCS-gel prepared from 20 mg/ml APCS had the highest transparency (Fig. 1C), which was only surpassed by the native cornea (Fig. 1F). The turbidimetric gelation kinetics of APCS-gel and fibrin gel (Fig. 1G) were characterized spectrophotometrically at 37°C, by comparing a range of APCS concentrations and the gelation parameter quantified between tlag (the APCS-gel formation initiation) and t1/2 (half gelation). We observed that the turbidimetric gelation of APCS-gel was concentration-dependent. The tlag of sol-gel transition were decreased from 11.0 ± 0.5 minutes to 1.0 ± 0.2 minute and the t1/2 were decreased from 17.7 ± 0.2 minutes to 4.3 ± 0.3 minutes when the APCS concentrations were increased from 10 mg/ml to 30 mg/ml. Compared to the APCS-gel, the tlag and t1/2 was 0.2 ± 0.2 minutes and 3 ± 1 minutes for fibrin gel respectively (n=3, p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Macroscopic appearance, turbidimetric gelation kinetics and light transmittance of APCS-gel, and fibrin gel. The APCS-sol were prepared by using APCS powder at a concentration of 10 (A), 15 (B), 20 (C) or 30 (D) mg/ml respectively which were digested with pepsin followed by pH neutralization. For macroscopic analysis, 100 μl/well of each APCS-sol (A-D), and fibrin gel (E) were prepared in a 96 wells plate and incubated for 1h at 37°C. The characteristics of these gels were compared to a 6.0 mm diameter pre-cut native porcine cornea (F). APCS-gel of 20 mg/ml provided the best transparency for the hydrogels. The gelation kinetics (G) was determined by adding 100 μl/well of APCS-sol, or fibrin gel into a 37 °C pre-heated 96-well plate and incubated at 37°C to induce gelation. The absorbance at 405 nm was measured at 2 min intervals and normalized between 0 (the initial absorbance) and 1 (the maximum absorbance). The light transmittance data (H) showed that APCS-gel at 20mg/ml is lower than native porcine cornea but highest than all other hydrogel, or fibrin gel (n=3). Scale bars represent 4 mm.

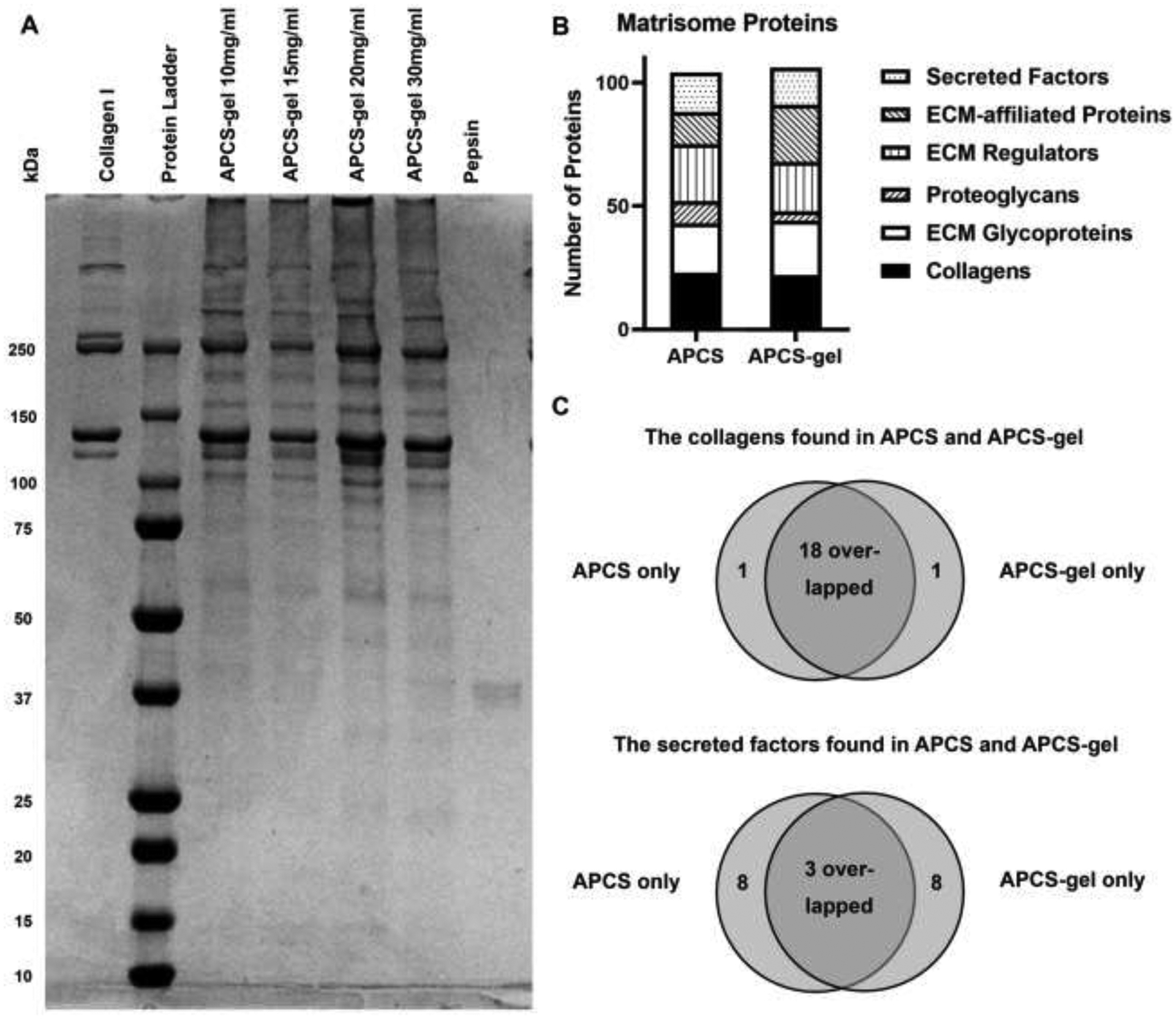

The light transmittance of APCS-gel was increased by using an APCS from 10 to 20 mg/ml concentration. However, when the APCS concentration was 30 mg/ml, the APCS-gel light transmittance was dramatically reduced. The highest light transmittance of APCS-gel was produced by 20 mg/ml APCS, its transparency properties was slightly lower than native cornea tissue, but it was higher than other APCS gels and fibrin gel (Fig. 1H, n=3, P<0.05). All APCS-gels showed protein bands of collagen I and pepsin, as well as other additional ECM bands. The highest density of protein bands was observed on the APCS-gel of 20 mg/ml, which suggest that this concentration retained the highest ECM content for the preparation of APCS-gel (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis of APCS-gel and characterization of matrisome proteins between APCS and APCS-gel by mass spectrometry. (A) Electrophoresis revealed all protein bands of APCS-gel prepared from APCS of different concentration. Compared to pure Collagen I, abundant high molecular weight proteins were presented within all the APCS-gel preparations, in which the APCS-gel prepared from 20 mg/ml APCS showed the highest protein bands density. Pepsin was used as a control to detect this protein used for the preparation of APCS-gel. (B) Similar inter-group proteomics variability between APCS and APCS-gel was found within most matrisome proteins. (C) 18 collagens and 3 secreted factors overlapped between the APCS and the APCS-gel except only one collagen and 8 secreted factors were identified exclusively in the APCS group or the APCS-gel group. Detailed list is shown in S1.

We also investigated the composition of the APCS and APCS-gel by mass spectrometry and analysis of the matrisome content (ECM) [30]. The total number of proteins identified were 104 and 106 for APCS and APCS-gel respectively. The proteomics results demonstrated low variability between APCS or APCS-gel (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the APCS and the APCS-gel shared the majority of collagens, including collagen I, collagen IV, and collagen V. Several critical secreted factors are also shared such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and bone morphogenetic protein (Fig. 2C; S1).

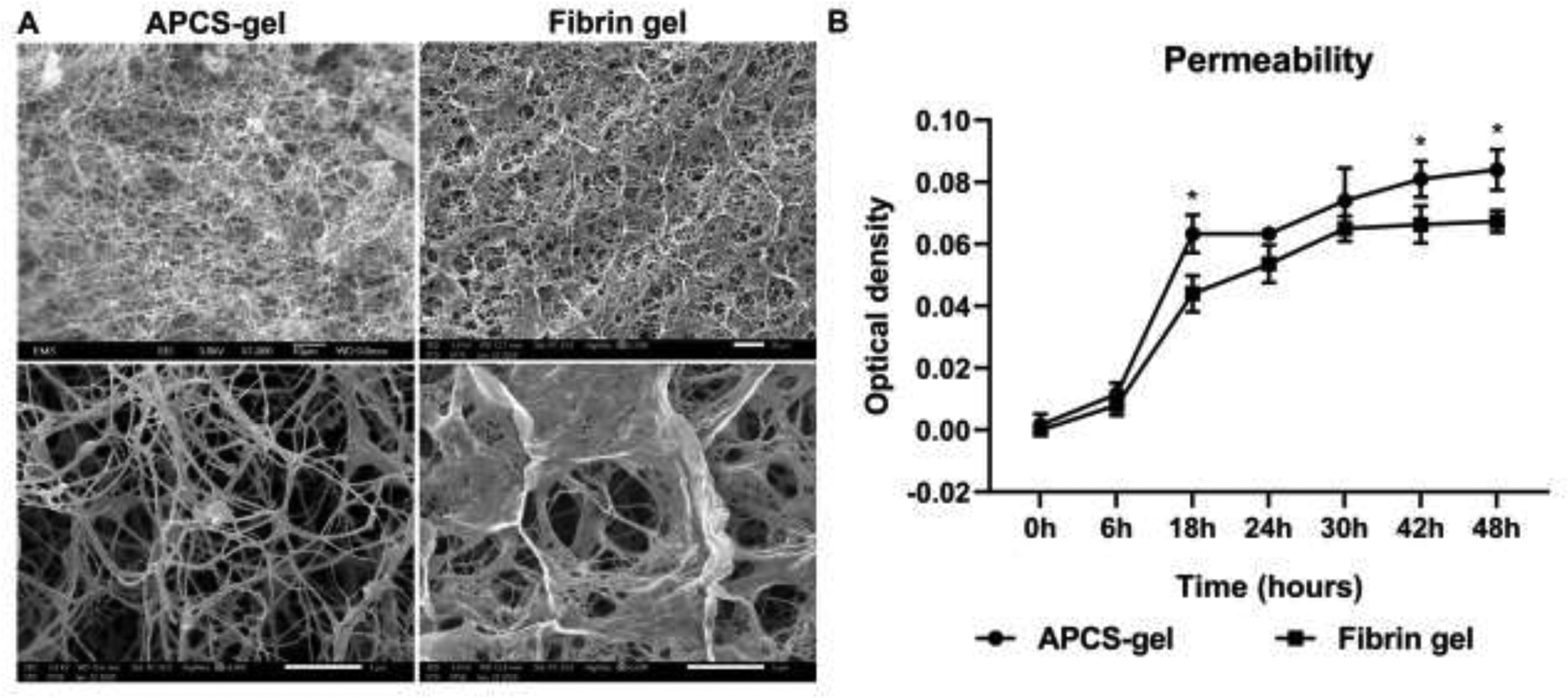

3.2. Evaluation of surface ultrastructure and permeability of APCS-gel and fibrin gel

The surface ultrastructure and permeability of hydrogels are important characteristics that impact the cellular microenvironment, supply of nutrition and removal of metabolic waste, all fundamental for cellular growth. The scanning electron microscopy and permeability assay were performed to determine these characteristics. The SEM of the APCS-gel surface showed qualitatively that it possessed larger pores and higher porosity than the fibrin gel (Fig. 3A). The porosity of APCS-gel was 63 ± 5 %, which is significantly higher than the fibrin gel of only 28 ± 4 % (p<0.05; n=3). Furthermore, APCS-gel showed significantly higher permeability compared to the fibrin gel during the 48 hours observation. The largest difference of 23 ± 7 % was observed after the first 18 hours of incubation, at which time the APCS-gel showed a higher permeability than the fibrin gel group (Fig. 3B, n=3, p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Scanning electron microscopy micrographs and the permeability assessment of APCS-gel and fibrin gel. The SEM micrograph (A) showed 1000 × (upper) and 5000 × images (lower) of APCS-gel (20 mg/ml APCS group) or fibrin gel respectively. The ultrastructure of APCS-gel demonstrated higher porosity (63 ± 5%) than the fibrin gel (28 ± 4%) (p<0.05; n=3). (B) The permeability assay showed that the APCS-gel had significantly higher permeability than the fibrin gel during 48 hours of observation (p< 0.05; n=3). Scale bars represent 10 μm (1000 ×) and 5 μm (5000 ×)

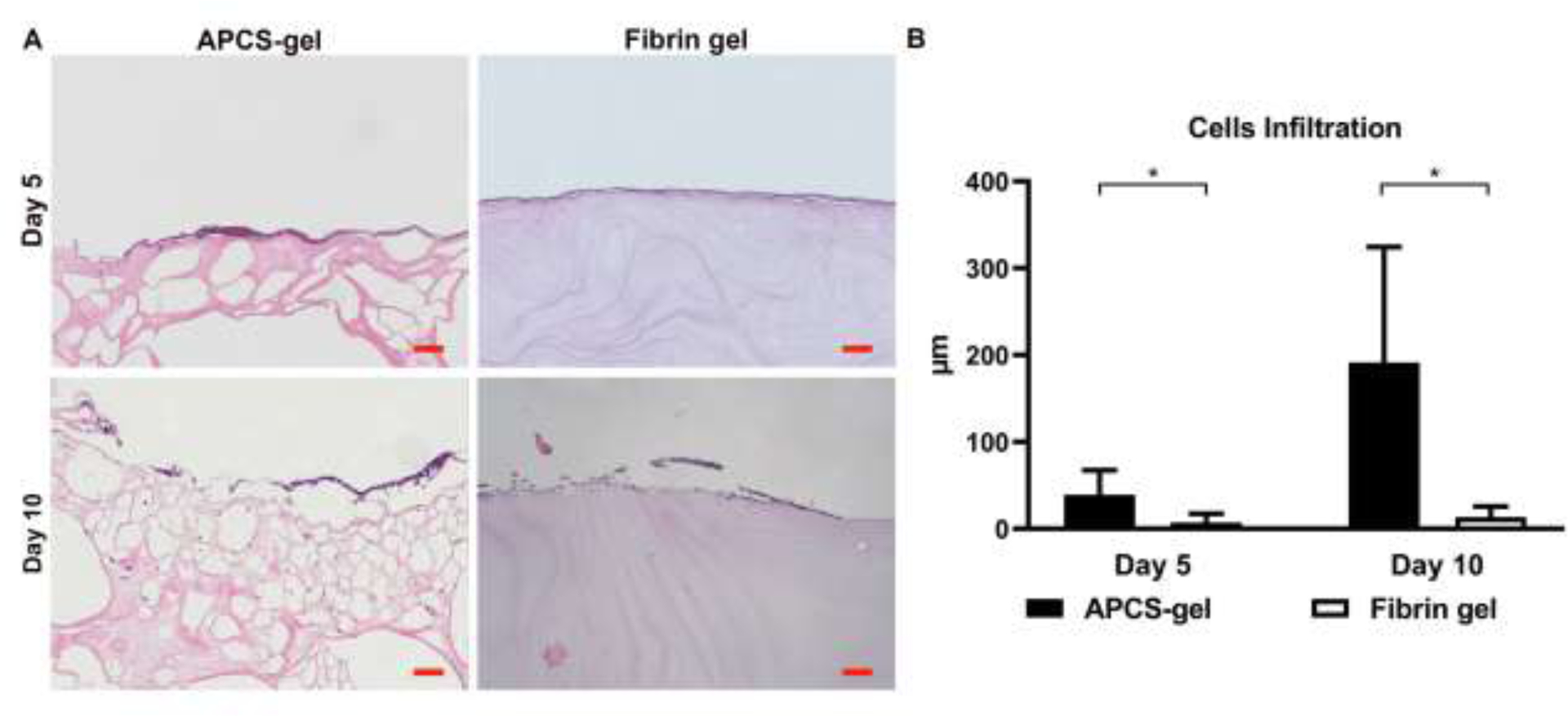

3.3. Quantification of cell infiltration on APCS-gel

Ideally a scaffold for corneal reconstruction should provide the physical properties of the corneal stroma for cellular implantation, proliferation and maintenance of its function. We evaluated whether RCSCs cultured on the surface of APCS-gel and fibrin gel were able to mobilize and infiltrate these gels. We analyzed the infiltration rates at 5- and 10-days post seeding. The results showed that RCSCs infiltration was higher in the APCS-gel than the fibrin gel (Fig. 4A). After 5 days of culture, the average cellular infiltration depth was 39 ± 28 μm in APCS-gel which is significantly deeper than the 7 ± 10 μm seen in fibrin gel. Moreover, after 10 days of culture, the average depth of APCS-gel group reached 191 ± 132 μm, which was significantly deeper than 13 ± 12 μm in the fibrin gel group (Fig. 4B, n=3, p<0.05).

Figure 4.

Cell infiltration of APCS-gel and fibrin gel. RCSCs were seeded and cultured on the surface of APCS-gel and fibrin gel. (A) After 5 and 10 days of culture, the distances of cell infiltration from the surface were quantified via histologic analysis of H&E stained cross-section. (B) The maximal distance of RCSCs infiltrated from the surface after 5 and 10 days of culture were 39 ± 28 μm and 192 ± 133 μm, which were significantly deeper than the fibrin gel group of 7 ± 10 μm and 13 ± 12 μm (n=3, p<0.05). Scale bars represent 100 μm.

3.4. APCS-gel Biocompatibility

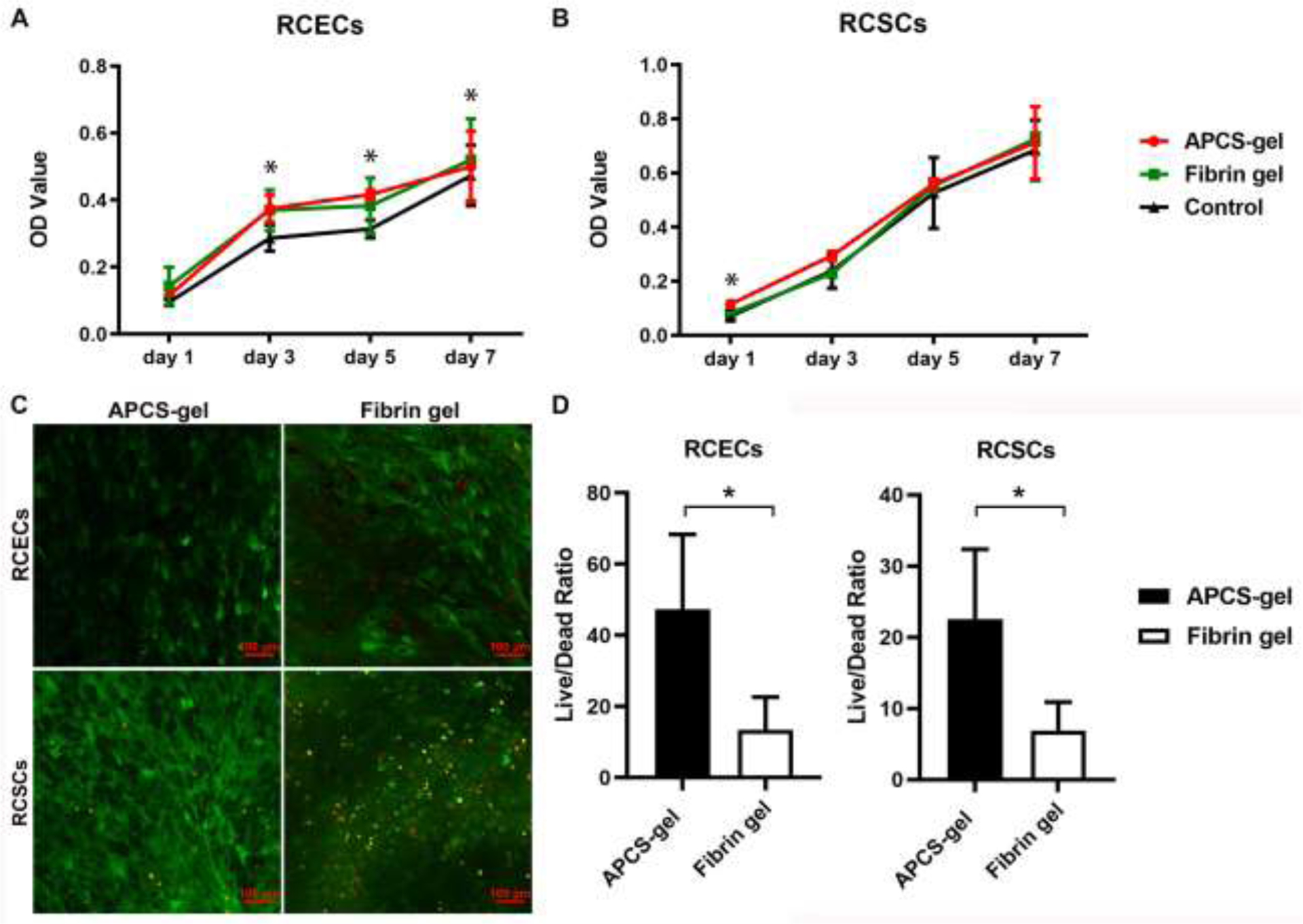

An important characteristic of a scaffold biomaterial for corneal reconstruction is to have cellular biocompatibility and no biotoxicity. To analyze the biocompatibility of APCS-gel, RCECs and RCSCs were cultured in medium extracts of APCS-gel and fibrin gel, and an MTT assay was performed up to 7 days in culture. Cells grown in normal culture media were used as a control. The MTT test results showed that there are no significant differences in the proliferation of RCECs and RCSCs between the APCS-gel and fibrin-gel (Fig. 5A). However, RCECs incubated with extract medium derived from APCS-gel and fibrin gel showed significant higher proliferation than the control group (Fig. 5B). The biocompatibility of RCECs and RCSCs cultured on APCS-gel and fibrin gel were also evaluated by live/dead assay. We found that the majority of RCECs or RCSCs cultured on or within the bulk of APCS-gel and fibrin gel were viable (green cytoplasm without red nuclei). However, after 7 days of culture, more viable RCECs or RCSCs were observed on the APCS-gel compared to the fibrin gel (Fig. 5C, S2, S3). Quantification of the cells also confirmed a higher ration of live/dead cells in APCS-gel versus the fibrin gel (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

The effect of APCS-gel and fibrin gel on the proliferation and viability of primary RCECs and RCSCs. The MTT results showed similar RCECs (A) and RCSCs (B) proliferation in extraction media of APCS-gel and fibrin gel. However, significantly higher proliferation was observed for RCEC in the APCS-gel or fibrin gel compared to cells seeded on normal media (control) (n=3, P < 0.05). (C) Live/Dead staining of the hydrogel surface for viable cells (green) and dead cell nuclei (red) imaged with confocal microscopy. RCECs and RCSCs were cultured on or within gels for 7 days before analysis. (D) The live/dead cells ratio of APCS-gel group for both cell types were significantly higher than the fibrin gel group (n=3, p<0.05). Scale bars represent 100 μm.

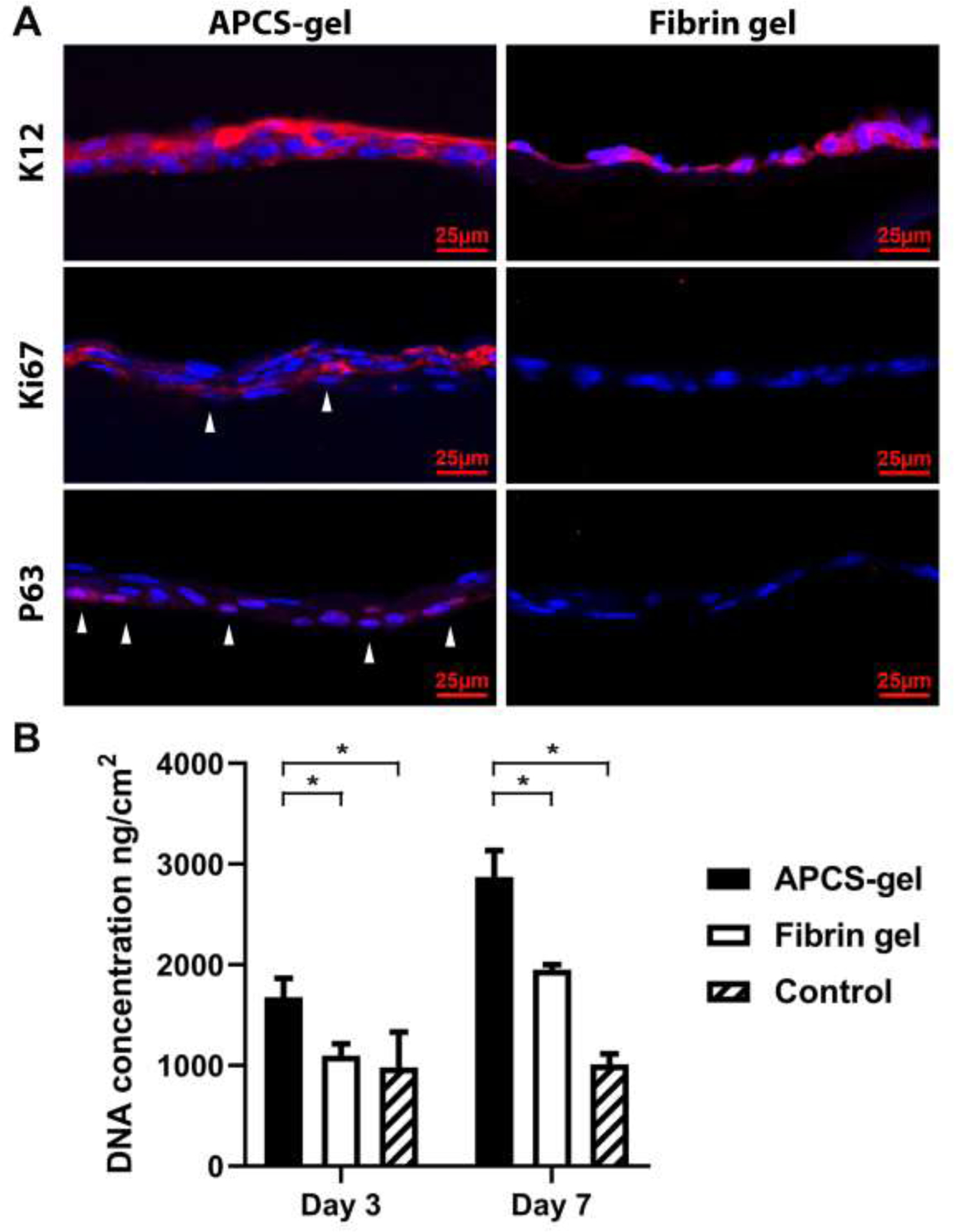

3.5. Evaluation of stem/progenitor cells phenotypes on the APCS-gel

Corneal epithelial stem/progenitor cells are essential to maintain cellular homeostasis. They are the precursor of epithelial cells and constitute a reservoir for physiological corneal epithelium replacement. Their presence in culture conditions or cornea reconstruction enhances the corneal epithelial cells healing. We evaluated the stemness and differentiation phenotypes of RCEC seeded on APCS-gel and fibrin gel. After 7 days of culture, 3–4 layers of epithelial cells were formed on APCS-gel. Staining of corneal epithelial cells for stem cell and differentiation markers, shows that stemness-like phenotypes (K12 negative, P63 positive: red) and the proliferation marker (Ki67 positive: red) were observed in the basal layers of RCECs on the APCS-gel. In comparison, only 1–2 layers of RCECs were observed on fibrin gel, in which only K12 positive (corneal epithelial cell differentiation marker) were present, and no presence of stem cells were found (Fig. 6A). The increased cellular proliferation of RCECs in the APCS-gel was also confirmed by measuring the total cellular DNA content. After 3 days of culture, the DNA content of RCECs on APCS-gel (1677 ± 187 ng/cm2) was significantly higher than the fibrin gel (1097 ± 119 ng/cm2) and control group (983 ± 347 ng/cm2). Moreover, after 7 days of culture, even the DNA content of fibrin gel (1952 ± 52 ng/cm2) was increased and higher than control (1012 ± 103 ng/cm2), the DNA content on APCS-gel (2872 ± 264 ng/cm2) was still significantly higher than the fibrin gel group (Fig. 6B, n=3, p<0.05).

Figure 6.

The APCS-gel maintained the stem/progenitor phenotypes and improved the corneal epithelial cells proliferative properties in vitro. (A) After 7 days of culture, 3–4 layers of RCECs were observed on the APCS-gel, compared to 1–2 layers of RCECs on fibrin gel. The potential limbal stem/progenitor phenotypes (K12 negative; P63 positive: red, white arrow) and proliferation marker (Ki67 positive: red, white arrow) were observed in the basal layers of the epithelium on the APCS-gel, while we found only K12 positive, (corneal epithelial differentiation marker) in the corneal epithelial cells on fibrin gel. (B) Higher proliferation of RCECs on APCS-gel was confirmed by analyzing the DNA content. After 3 and 7 days of culture, the DNA content of RCECs seeded on APCS-gel were 1677 ± 187 ng/cm2 and 2872 ± 264 ng/cm2 respectively, which were significantly higher than fibrin gel, as well as control group (n=3, p<0.05).

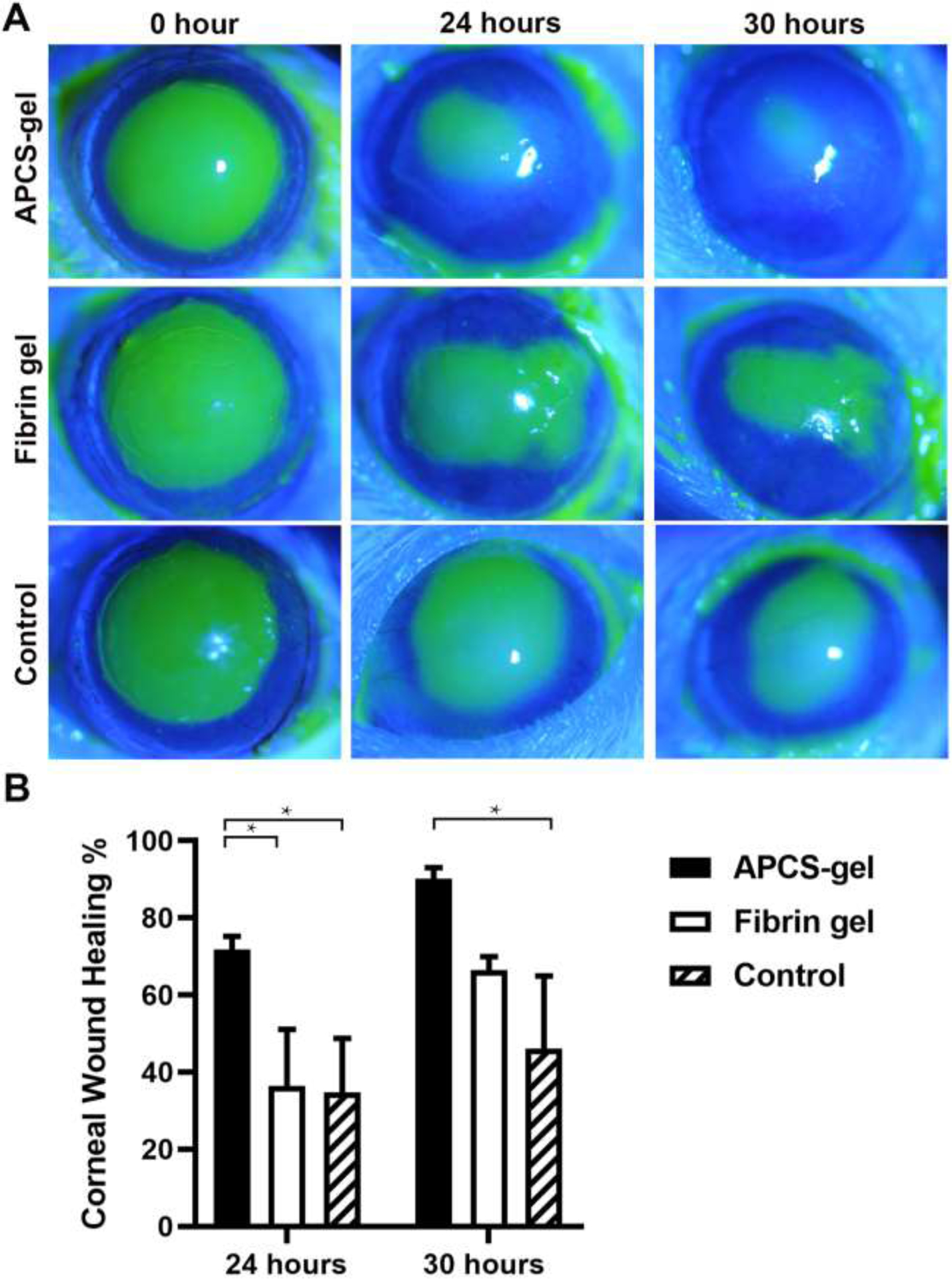

3.6. Effect of APCS-gel on corneal epithelium healing

We evaluated if our biocompatible APCS-gel could also support and enhance the growth of corneal epithelial cells in vivo. For this, the corneal epithelium debridement model in mice were performed, where a 2 mm central corneal epithelium was removed and then received treatment of APCS-gel or fibrin gel. A faster wound epithelium regeneration was observed in mice that received the APCS gel (Fig. 7A, S4). In this group, the wound healing area were 72 ± 3% after 24 hours and 90 ± 3% after 30 hours, while the wound healing area was reduced in the fibrin gel group with only 36 ± 15% and 66 ± 4% healing area. In addition, the wound healing area was 35 ± 14% and 46 ± 19% respectively in control group (Fig. 7B, n=3, p<0.05). Additionally, we evaluated the effect of the APCS on a corneal stroma penetrating injury (S5) and found that mice that received the APCS-gel had faster healing and recovery of the corneal shape and thickness, and they did not develop inflammation (S6).

Figure 7.

APCS-gel enhanced cornea epithelium wound healing in vivo. CD1 mice were subjected to 2 mm central corneal epithelium debridement and received either APCS-gel, fibrin gel or no treatment. The wound healing was evaluated by using slit-lamp and fluorescein staining. A faster corneal epithelium recovery was observed in the APCS-gel group. (A) After 24 and 30 hours, the wound healing were observed in APCS-gel, fibrin gel and control group. (B) The wound healing quantification showed that the APCS-gel group healed faster than the fibrin gel and control group (n=3, p<0.05).

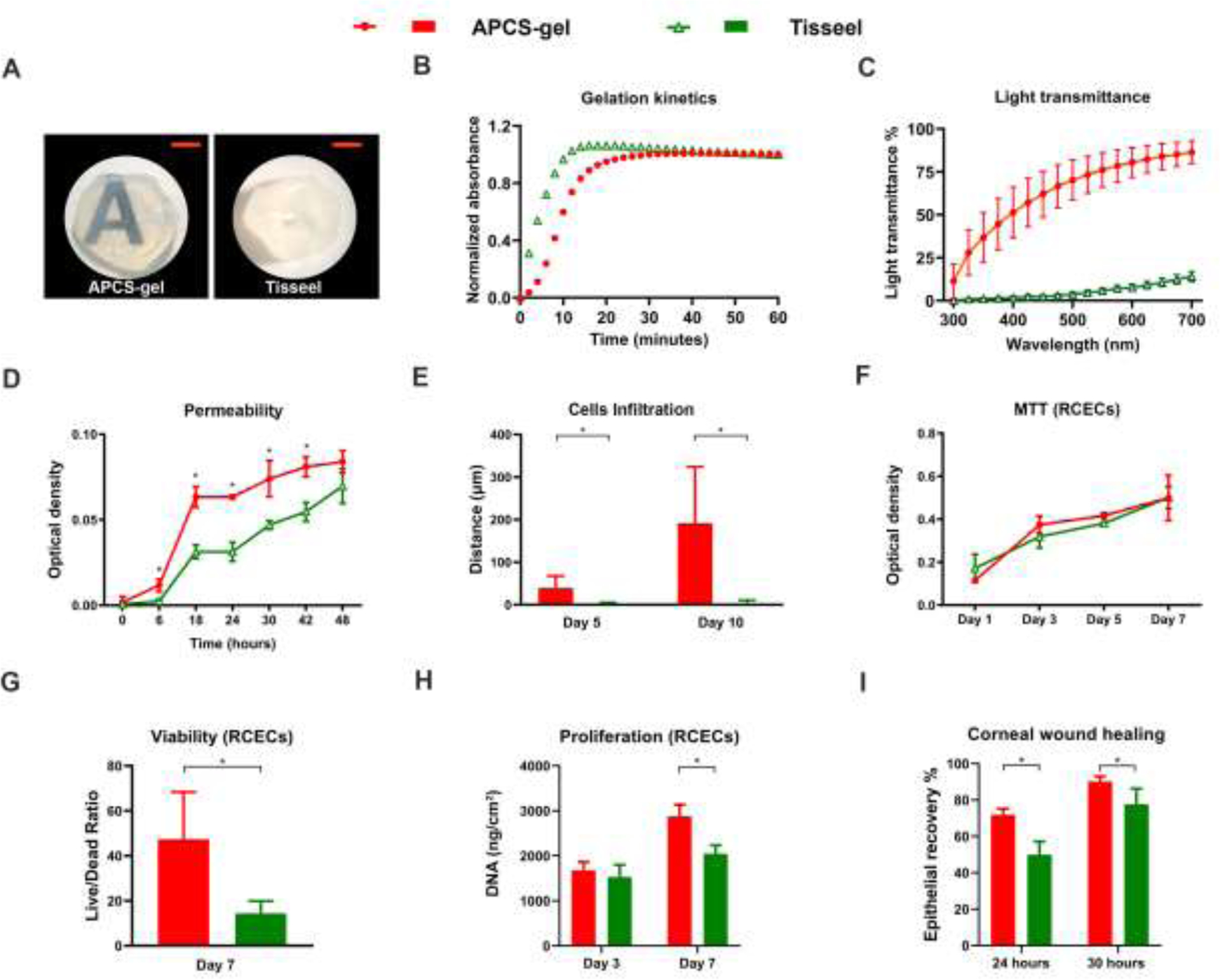

3.7. Comparative physical and biological properties of APCS-gel versus Tisseel

We performed a comparative analysis between our APCS-gel and a clinically use fibrin gel (Tisseel). For this we compared the APCS-gel prepared by using APCS powder at a concentration 20 mg/ml with Tisseel and evaluated their physical and biological properties. We found that the APCS-gel had better transparency and light transmittance than Tisseel (Fig. 8A, C). However, its gelation time was longer compared with Tisseel (Fig. 8B). In general, the APCS-gel had better biological properties than Tisseel. We found that the APCS-gel had significantly higher permeability than Tisseel during the 48 hours observation period, and the highest differentiation (45 ± 13 %) was observed after 18 hours (Fig. 8D). The average cellular infiltration depth of RCSCs in APCS-gel was significantly higher than Tisseel after 5 and 10 days of culture (Fig. 8E). However, the MTT biocompatibility assays, demonstrated similar results between APCS-gel and Tisseel for cultured RCECs (Fig. 8F) and RCSCs (S7A). When we analyzed the viability of the isolated corneal cells on both substrates, we found, a higher ratio of viable RCECs (Fig. 8G) and RCSCs (S7B) in APCS-gel than Tisseel after 7 days in culture. Furthermore, higher proliferation of RCECs were also found in APCS-gel than Tisseel, in which only 1–2 layers of RCECs were formed, and only differentiation but no proliferation phenotypes of RCEC were detected after 7 days of culture (S8). While the DNA concentration of RCECs on APCS-gels was similar to Tisseel after 3 days culture, it was significantly higher than Tisseel after 7 days in culture (Fig. 8H). Additionally, the in vivo corneal wound healing assay demonstrated faster corneal epithelial cells recovery in mice that received the APCS-gels compared to those treated with Tisseel (Fig. 8I). For all these experiments n=3, p<0.05.

Figure 8.

Physical and biological properties of APCS-gel compared with Tisseel. We performed a parallel analysis for the physical and biological properties of APCS-gel, prepared by using APCS powder at a concentration 20 mg/ml, versus a clinically used fibrin gel (Tisseel). (A) The macroscopic view of the APCS-gel demonstrated better transparency compared with Tisseel. (B) The turbidimetric gelation kinetics shows that Tisseel reached full gelation earlier than the APCS-gel. (C) However, the light transmittance of APCS-gel is higher than the Tisseel. (D) The permeability assay showed that the APCS-gel had significantly higher permeability than Tisseel during 48 hours of observation. (E) The maximal distance of RCSCs infiltration from the surface after 5 and 10 days of culture in APCS-gel were significantly deeper than the Tisseel. (F) The MTT results showed similar RCECs proliferation in extraction media derived from APCS-gel and Tisseel. The RCECs viability of APCS-gel was significantly higher than the Tisseel (G) and also significantly higher proliferation of RCECs was observed on APCS-gel versus Tisseel at day 7 by the evaluation of DNA concentration (H). Importantly, the in vivo corneal wound healing analysis showed that mice that received the APCS-gel healed faster than those treated with Tisseel (I). For all the experiments n=3, p<0.05. Scale bars represent 4 mm.

4. Discussion

We propose that ECM hydrogels which are applied in liquid form, but then transition to a more solid gel state may provide benefits due to their ability to fill irregular penetrating injuries immediately [35]. An ideal hydrogel for corneal reconstruction should also provide a microenvironment to improve cellular adhesion and proliferation, facilitate the recovery of their structural and trophic functions, as well as provides enough transparency to maintain visual acuity.

Previously, we have developed an APCS which retains most of the corneal ECM, including the main types of the collagens and glycosaminoglycans [19]. Our study demonstrated that the APCS contains a similar physical structure and retains the original microenvironment of the native corneal stroma. Other studies have also demonstrated that the APCS could provide great advantages for the reconstruction of corneal keratocytes and epithelium layers, and maintain corneal limbal epithelial cells stemness and proliferation [19, 20, 23, 32]. All these characteristics make APCS a potential candidate for corneal repair. However, in the setting of an irregular corneal defect, APCS size must be skillfully trimmed to a suitable size and shape for treatment. Moreover, APCS constructs require suturing, with the attendant difficulties which come with this technique. Finally, the irregular interface between APCS and the host cornea may also decrease vision.

Here we developed APCS-gel, a hydrogel derived from the ECM, which retains the similar components and characteristics of the solid APCS and native cornea. It can be kept as solution at 4 °C and quickly transitions to a hydrogel at 37 °C (average human body temperature). This is clinically important since the biomaterial as a solution can be used in surgical procedures and quickly reach a gel state that protects the integrity of the tissue and allows for native cells to adhere and grow. In order to accelerate the gelation time, as previous reported [13, 18], several high concentrations of APCS were used to optimize the hydrogel preparation. We found that the APCS-gel could be formed from APCS concentration of 10–30 mg/ml with improved turbidimetric gelation kinetics. Notably, the APCS-gel of 20 mg/ml showed faster gelation period [17, 18, 36] and better light transmittance [18] than previously reported hydrogels. Furthermore, it also enhanced the corneal stromal cell infiltration and epithelial cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo, which both were critical for the corneal regeneration. These two factors, proliferation and infiltration, to our knowledge, have not been simultaneously investigated in hydrogels derived from the decellularized cornea [17, 18, 36].

Previous work has demonstrated that ECM components would rapidly improve the hydrogel self-assembly period after the ECM monomeric was neutralized [37, 38]. During the decellularization procedure, the structure, protein or glycosaminoglycans of native tissue could be easily damaged by the chemical or physical decellularization methods; therefore, the native ECM component was decreased [39]. As we previously described, the APCS created by the application of phospholipase A2, only catalyzes the hydrolysis of the ester bond at the sn-2 position of cellular membrane glycerophospholipids without reacting with the corneal stromal proteins and proteoglycans. This process allowed for the majority of the corneal stroma ECM retained in APCS after the decellularization process [19, 21]. In this study, we investigated if the generated APCS-gel retained most of the corneal ECM and if this result in an improved gelation time. Our results suggest that the APCS-gel retains most corneal critical ECM components. Analysis by SDS-PAGE revealed many high molecular weight bands that appears to be rich in collagen I. Our finding that the densest bands were observed in the APCS-gel of 20 mg/ml may suggest that under or over proteolysis may have occurred at other concentrations. Further mass spectrometry analysis demonstrated that most of the proteins are overlapped between the APCS and APCS-gel group including the majority of collagen I, V, IV, and others core and associated matrisomal proteins. Our results also demonstrate that the APCS-gel produced from this APCS had a shortest gelation time than previous reports [17, 18] which suggest that native ECM components and quantity could significantly improve the hydrogel formation.

Transparency is another desired characteristic in the biomaterial development for clinical cornea application. The processing of our APCS-gel resulted in a homogeneous product where the polymerization of proteins and proteoglycans yield a hydrogel with high light transmittance. More than seven types of collagens and some specific corneal proteoglycans were included in the cornea ECM, which are critical for corneal transparency [40]. The ECM hydrogel showed distinct fibril networks and morphology compared with the purified collagen I hydrogel [41]. The retention of proteoglycans, the hydrogel formation condition, as well as the enzyme used, all contribute to the properties of ECM hydrogel [37]. With the adjustment of these factors during ECM hydrogel preparation, the thickness of fibrils or organization of fibril networks were modified. In our previously reported study, the light transmittance of APCS was not significantly different from the NPC, because the corneal stromal extracellular structure and most of the corneal ECM components were retained [19]. In this study, before the neutralization process, the APCS-sol which were derived from APCS, appeared with high light transmittance in its solution phase. However, after the sol-gel transition, the light transmittance of APCS-gels demonstrated a wide discrepancy. The highest light transmittance was observed in APCS-gel produced from 20 mg/ml APCS which was completely homogeneous and without visible particles. The light transmittance of this APCS-gel is similar to the NPC, and higher than all previously reported corneal ECM hydrogel [18], fibrin gels or Tisseel. Of interest, as APCS concentration decreased to 10–15 mg/ml, light transmittance decreased, as well. Reasons for this unexpected decrease in transparency may include the effect of critical micelle concentration and emulsification properties created by undigested material which could increase light scattering [42]. In conclusion, the high light transmittance of APCS-gel made from 20 mg/ml APCS highly suggests it a promising corneal biomaterial for further clinical investigation.

The recovery of corneal stromal keratocyte cells is critical for maintaining the precise physical cell stratification array and transparency after corneal injury [35]. Keratocyte growth in vitro and in vivo was hampered in our previously studied APCS because of the narrow space between corneal stromal fibers [21]. In the APCH-gel, a higher porosity ratio was observed by SEM compared with APCS, fibrin gel or Tisseel; and a higher permeability was also observed by assessment compared with fibrin gel or Tisseel. After 10 days of culture, it was demonstrated that the RCSCs significantly infiltrated the APCS-gel compared to fibrin gel or Tisseel. Additionally, the live/dead assay results also showed the RCSCs viability in APCS-gel was significantly higher than in fibrin gel or Tisseel. Both the high porosity and permeability of the APCS-gel may facilitate nutrition diffusion and metabolic waste removal which is critical for cell infiltration and distribution during the cornea reconstruction process [43]. The retention of the original native ECM in the hydrogel may be another possible reason for the maintenance of the keratocyte phenotype and improve its proliferation [44]. ECM proteins such as collagen IV, fibroblast growth factors, and bone morphogenetic protein which are shown in the mass spectrometry analysis of the APCS-gel, may improve cellular adhesion and growth. In general, our combined results demonstrated the advantage of APCS-gel for the proliferation of corneal stroma cells, which is essential for the reconstruction of stromal lamellar structure by using acellular biomaterial.

Another important aspect of a biomaterial design for clinical use, is promoting corneal epithelial cell proliferation. Reconstruction of a corneal injury not only requires recovery of corneal stroma architecture and function, but also the regeneration of the corneal epithelium, which could provide trophic and protective function. ECMs, in general, have shown critical roles in the promotion of cellular adhesion and proliferation by providing tissue-specific biochemical cues and microenvironment [45]. Several recent reports have shown that ECM hydrogels could provide a similar cellular microenvironment representative of the native tissue, thus enhancing regeneration of organs such as the myocardium, spinal cord, brain, tendon, and skeletal muscle [12, 37]. During APCS preparation, the native corneal epithelial basement proteins such as collagen IV, were retained after decellularization, which could support the limbal epithelial cell stemness and enhance proliferation [20, 21]. In this experiment, the APCS-gel was prepared from this acellular corneal ECM, and its functions were evaluated by the growth of epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo with the APCS-gel substrate. In vitro, after 7 days of culture, we found that 3–4 layers of RCECs were formed on APCS-gel compared to only 1–2 layers of RCECs on the fibrin gel and Tisseel. Additionally, more potential stem cell markers such as K12 negative, p63 positive and proliferation marker such as Ki67 positive were observed on RCECs seeded on the APCS-gel than fibril gel and Tisseel. These results were corroborated with the observations in vivo using a mouse model of corneal epithelial debridement. The re-epithelialization results confirmed that the corneal wound healing was accelerated upon the application of APCS-gel compared to the fibrin gel, Tisseel and control group. From these results, we hypothesized that the nanofibrils and network of APCS-gel could promote the maintenance of the limbal cells stemness and support corneal epithelial cell proliferation. During corneal wound healing, the nanostructure and stiffness of scaffolds also affect the maintenance of limbal cell stemness and proliferation [46, 47]. The APCS-gel contains similar components as APCS, is derived from native corneal ECM, which have similar natural stiffness, and is important for cellular stemness maintenance and produces minimal angiogenesis activities [20]. Instead, the fibrin gel which has been used for corneal epithelial cell reconstruction in the clinic, showed high stiffness properties which may decrease the corneal limbal cell stemness may decrease the transparency of the cornea [48].

There is still room for further optimization of the APCS-gel preparation. Sterilization techniques such as gamma radiation could be further applied to minimize the potential risk of transmissible diseases or unknown factors [45]. But its effect on the biomechanical properties and cellular behavior response needs to be further determined after the sterilization treatment. At this point, the APCS-gel strongly indicates its high potential for corneal epithelial cells regeneration and may be a better candidate for corneal wound repair than fibrin gel.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we generated an APCS-gel that retains critical characteristics of the native cornea. It has high light transmittance and rapid gelation kinetics for application in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, this hydrogel is highly suitable for corneal epithelial cell reconstruction by maintaining stemness and enhanced proliferation of ocular surface cells. Finally, the APCS-gel has better light transmittance and biocompatibility than clinically used fibrin gel. Given its biomaterial characteristics, APCS-gel may provide a promising therapeutic intervention for the treatment of corneal wounds and could reduce the need for corneal transplantation in the future.

Supplementary Material

Statement of significance:

Extracellular matrix (ECM) can be used to provide tissue specific physical microstructure and biochemical cues for tissue regeneration. Here, we produced an ECM hydrogel derived from acellular porcine cornea stroma (APCS-gel) that retained critical biological characteristics of the native tissue and provided significant transparency and fast gelation time. Our data demonstrated that the APCS-gel was superior to clinically used fibrin gel, as the APCS-gel showed high porosity and permeability, better corneal stromal keratocytes infiltration, increased cellular proliferation and retention of corneal epithelial cells stemness. The APCS-gel improved corneal wound healing in vitro and in vivo. This APCS-gel may have clinical utility for corneal diseases, and the more general approach used to make this hydrogel might be used in other tissues.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the NIH R01EY027912, P30EY001792 Core Grant for Vision Research, Illinois Society for the Prevention of Blindness G3127 and Research to Prevent Blindness Unrestricted Departmental Grant, and Falk Medical Research Trust Catalyst Awards Program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Hicks CR, Fitton JH, Chirila TV, Crawford GJ, Constable IJ, Keratoprostheses: advancing toward a true artificial cornea, Survey of ophthalmology 42(2) (1997) 175–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Krysik K, Dobrowolski D, Lyssek-Boron A, Jankowska-Szmul J, Wylegala EA, Differences in Surgical Management of Corneal Perforations, Measured over Six Years, Journal of ophthalmology 2017 (2017) 1582532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hos D, Matthaei M, Bock F, Maruyama K, Notara M, Clahsen T, Hou Y, Le VNH, Salabarria AC, Horstmann J, Bachmann BO, Cursiefen C, Immune reactions after modern lamellar (DALK, DSAEK, DMEK) versus conventional penetrating corneal transplantation, Progress in retinal and eye research 73 (2019) 100768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Vora GK, Haddadin R, Chodosh J, Management of corneal lacerations and perforations, International ophthalmology clinics 53(4) (2013) 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jirsova K, Jones GLA, Amniotic membrane in ophthalmology: properties, preparation, storage and indications for grafting-a review, Cell and tissue banking 18(2) (2017) 193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Solomon A, Meller D, Prabhasawat P, John T, Espana EM, Steuhl KP, Tseng SC, Amniotic membrane grafts for nontraumatic corneal perforations, descemetoceles, and deep ulcers, Ophthalmology 109(4) (2002) 694–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sharma A, Kaur R, Kumar S, Gupta P, Pandav S, Patnaik B, Gupta A, Fibrin glue versus N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate in corneal perforations, Ophthalmology 110(2) (2003) 291–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chen WL, Lin CT, Hsieh CY, Tu IH, Chen WY, Hu FR, Comparison of the bacteriostatic effects, corneal cytotoxicity, and the ability to seal corneal incisions among three different tissue adhesives, Cornea 26(10) (2007) 1228–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Takei A, Tashiro Y, Nakashima Y, Sueishi K, Effects of fibrin on the angiogenesis in vitro of bovine endothelial cells in collagen gel, In vitro cellular & developmental biology. Animal 31(6) (1995) 467–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dvorak HF, Harvey VS, Estrella P, Brown LF, McDonagh J, Dvorak AM, Fibrin containing gels induce angiogenesis. Implications for tumor stroma generation and wound healing, Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology 57(6) (1987) 673–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].McTiernan CD, Simpson FC, Haagdorens M, Samarawickrama C, Hunter D, Buznyk O, Fagerholm P, Ljunggren MK, Lewis P, Pintelon I, Olsen D, Edin E, Groleau M, Allan BD, Griffith M, LiQD Cornea: Pro-regeneration collagen mimetics as patches and alternatives to corneal transplantation, Sci Adv 6(25) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Spang MT, Christman KL, Extracellular matrix hydrogel therapies: In vivo applications and development, Acta biomaterialia 68 (2018) 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wolf MT, Daly KA, Brennan-Pierce EP, Johnson SA, Carruthers CA, D’Amore A, Nagarkar SP, Velankar SS, Badylak SF, A hydrogel derived from decellularized dermal extracellular matrix, Biomaterials 33(29) (2012) 7028–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Medberry CJ, Crapo PM, Siu BF, Carruthers CA, Wolf MT, Nagarkar SP, Agrawal V, Jones KE, Kelly J, Johnson SA, Velankar SS, Watkins SC, Modo M, Badylak SF, Hydrogels derived from central nervous system extracellular matrix, Biomaterials 34(4) (2013) 1033–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tukmachev D, Forostyak S, Koci Z, Zaviskova K, Vackova I, Vyborny K, Sandvig I, Sandvig A, Medberry CJ, Badylak SF, Sykova E, Kubinova S, Injectable Extracellular Matrix Hydrogels as Scaffolds for Spinal Cord Injury Repair, Tissue engineering. Part A 22(3–4) (2016) 306–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Seif-Naraghi SB, Singelyn JM, Salvatore MA, Osborn KG, Wang JJ, Sampat U, Kwan OL, Strachan GM, Wong J, Schup-Magoffin PJ, Braden RL, Bartels K, DeQuach JA, Preul M, Kinsey AM, DeMaria AN, Dib N, Christman KL, Safety and efficacy of an injectable extracellular matrix hydrogel for treating myocardial infarction, Science translational medicine 5(173) (2013) 173ra25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ahearne M, Lynch AP, Early Observation of Extracellular Matrix-Derived Hydrogels for Corneal Stroma Regeneration, Tissue engineering. Part C, Methods 21(10) (2015) 1059–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lu Y, Yao QK, Feng B, Yan CX, Zhu MY, Chen JZ, Fu W, Fu Y, Characterization of a Hydrogel Derived from Decellularized Corneal Extracellular Matrix, J Biomater Tiss Eng 5(12) (2015) 951–960. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wu Z, Zhou Y, Li N, Huang M, Duan H, Ge J, Xiang P, Wang Z, The use of phospholipase A(2) to prepare acellular porcine corneal stroma as a tissue engineering scaffold, Biomaterials 30(21) (2009) 3513–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Huang M, Li N, Wu Z, Wan P, Liang X, Zhang W, Wang X, Li C, Xiao J, Zhou Q, Liu Z, Wang Z, Using acellular porcine limbal stroma for rabbit limbal stem cell microenvironment reconstruction, Biomaterials 32(31) (2011) 7812–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wu Z, Zhou Q, Duan H, Wang X, Xiao J, Duan H, Li N, Li C, Wan P, Liu Y, Song Y, Zhou C, Huang Z, Wang Z, Reconstruction of auto-tissue-engineered lamellar cornea by dynamic culture for transplantation: a rabbit model, PloS one 9(4) (2014) e93012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhou Q, Liu Z, Wu Z, Wang X, Wang B, Li C, Liu Y, Li L, Wan P, Huang Z, Wang Z, Reconstruction of Highly Proliferative Auto-Tissue-Engineered Lamellar Cornea Enhanced by Embryonic Stem Cell, Tissue Eng Part C Methods (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Xiao J, Duan H, Liu Z, Wu Z, Lan Y, Zhang W, Li C, Chen F, Zhou Q, Wang X, Huang J, Wang Z, Construction of the recellularized corneal stroma using porous acellular corneal scaffold, Biomaterials 32(29) (2011) 6962–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhou Q, Liu Z, Wu Z, Wang X, Wang B, Li C, Liu Y, Li L, Wan P, Huang Z, Wang Z, Reconstruction of Highly Proliferative Auto-Tissue-Engineered Lamellar Cornea Enhanced by Embryonic Stem Cell, Tissue engineering. Part C, Methods 21(7) (2015) 639–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kim J, Rubin N, Huang Y, Tuan TL, Lien CL, In vitro culture of epicardial cells from adult zebrafish heart on a fibrin matrix, Nature protocols 7(2) (2012) 247–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Han B, Schwab IR, Madsen TK, Isseroff RR, A fibrin-based bioengineered ocular surface with human corneal epithelial stem cells, Cornea 21(5) (2002) 505–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Naba A, Clauser KR, Hynes RO, Enrichment of Extracellular Matrix Proteins from Tissues and Digestion into Peptides for Mass Spectrometry Analysis, Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE (101) (2015) e53057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Rost HL, Sachsenberg T, Aiche S, Bielow C, Weisser H, Aicheler F, Andreotti S, Ehrlich H-C, Gutenbrunner P, Kenar E, Liang X, Nahnsen S, Nilse L, Pfeuffer J, Rosenberger G, Rurik M, Schmitt U, Veit J, Walzer M, Wojnar D, Wolski WE, Schilling O, Choudhary JS, Malmstrom L, Aebersold R, Reinert K, Kohlbacher O, OpenMS: a flexible open-source software platform for mass spectrometry data analysis, Nature methods 13(9) (2016) 741–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Shao X, Taha IN, Clauser KR, Gao YT, Naba A, MatrisomeDB: the ECM-protein knowledge database, Nucleic Acids Res 48(D1) (2020) D1136–D1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Naba A, Clauser KR, Ding H, Whittaker CA, Carr SA, Hynes RO, The extracellular matrix: Tools and insights for the “omics” era, Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology 49 (2016) 10–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Spiller KL, Laurencin SJ, Charlton D, Maher SA, Lowman AM, Superporous hydrogels for cartilage repair: Evaluation of the morphological and mechanical properties, Acta biomaterialia 4(1) (2008) 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Liu Z, Zhou Q, Zhu J, Xiao J, Wan P, Zhou C, Huang Z, Qiang N, Zhang W, Wu Z, Quan D, Wang Z, Using genipin-crosslinked acellular porcine corneal stroma for cosmetic corneal lens implants, Biomaterials 33(30) (2012) 7336–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pereira HA, Ruan X, Gonzalez ML, Tsyshevskaya-Hoover I, Chodosh J, Modulation of corneal epithelial cell functions by the neutrophil-derived inflammatory mediator CAP37, Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 45(12) (2004) 4284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Guaiquil VH, Pan Z, Karagianni N, Fukuoka S, Alegre G, Rosenblatt MI, VEGF-B selectively regenerates injured peripheral neurons and restores sensory and trophic functions, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111(48) (2014) 17272–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chen Z, You JJ, Liu X, Cooper S, Hodge C, Sutton G, Crook JM, Wallace GG, Biomaterials for corneal bioengineering, Biomedical materials 13(3) (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wang F, Shi W, Li H, Wang H, Sun D, Zhao L, Yang L, Liu T, Zhou Q, Xie L, Decellularized porcine cornea-derived hydrogels for the regeneration of epithelium and stroma in focal corneal defects, The ocular surface 18(4) (2020) 748–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Saldin LT, Cramer MC, Velankar SS, White LJ, Badylak SF, Extracellular matrix hydrogels from decellularized tissues: Structure and function, Acta biomaterialia 49 (2017) 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wang RM, Christman KL, Decellularized myocardial matrix hydrogels: In basic research and preclinical studies, Advanced drug delivery reviews 96 (2016) 77–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gilpin A, Yang Y, Decellularization Strategies for Regenerative Medicine: From Processing Techniques to Applications, BioMed research international 2017 (2017) 9831534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Meek KM, Corneal collagen-its role in maintaining corneal shape and transparency, Biophysical reviews 1(2) (2009) 83–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Brightman AO, Rajwa BP, Sturgis JE, McCallister ME, Robinson JP, Voytik-Harbin SL, Time-lapse confocal reflection microscopy of collagen fibrillogenesis and extracellular matrix assembly in vitro, Biopolymers 54(3) (2000) 222–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rey M, Yang M, Lee L, Zhang Y, Sheff JG, Sensen CW, Mrazek H, Halada P, Man P, McCarville JL, Verdu EF, Schriemer DC, Addressing proteolytic efficiency in enzymatic degradation therapy for celiac disease, Scientific reports 6 (2016) 30980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Wei HJ, Liang HC, Lee MH, Huang YC, Chang Y, Sung HW, Construction of varying porous structures in acellular bovine pericardia as a tissue-engineering extracellular matrix, Biomaterials 26(14) (2005) 1905–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ahearne M, Lynch A, Extracellular matrix derived hydrogel for corneal tissue engineering, Acta ophthalmologica 91 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Song JJ, Ott HC, Organ engineering based on decellularized matrix scaffolds, Trends in molecular medicine 17(8) (2011) 424–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Gouveia RM, Lepert G, Gupta S, Mohan RR, Paterson C, Connon CJ, Assessment of corneal substrate biomechanics and its effect on epithelial stem cell maintenance and differentiation, Nature communications 10(1) (2019) 1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Madl CM, Heilshorn SC, Blau HM, Bioengineering strategies to accelerate stem cell therapeutics, Nature 557(7705) (2018) 335–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Heher P, Muhleder S, Mittermayr R, Redl H, Slezak P, Fibrin-based delivery strategies for acute and chronic wound healing, Advanced drug delivery reviews 129 (2018) 134–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.