Abstract

In this paper, we describe our approach to individualizing messages to promote the health of middle-aged and older heterosexual, cisgender African American men. After arguing the importance of being population specific, we describe the process we use to increase the salience of health messages for this population by operationalizing the identity concepts of centrality and contextualization. We also present a measure of African American manhood and discuss how manhood is congruent with qualitative research that describes how African American men view their values, identities, goals, and aspirations in ways that can be utilized to create more meaningful and impactful messages to promote and maintain health behaviors. Our tailoring strategy uses an intersectional approach that considers how the centrality of racial identity and manhood and the salience of religiosity, spirituality, and role strains may help to increase the impact of health messages. We highlight the need to consider how the context of health behavior and the meaning ascribed to certain behaviors are gendered, not only from a man’s perspective, but also how his social networks, behavioral context, and the dynamic sociopolitical climate may consider gendered ideals in ways that shape behavior. We close by discussing the need to apply this approach to other populations of men, women, and those who are non-gender binary because this strategy builds from the population of interest and incorporates factors that they deem central and salient to their identities and behaviors. These factors are important to consider in interventions using health messages to pursue health equity.

Keywords: tailoring, manhood, African American manhood, men’s health, men’s health equity, behavioral interventions

Over the last 30 years, individual tailoring has been used in myriad studies to increase recipient attention and perceived message salience and to decrease processing effort, thereby outperforming generic or group targeted messages in promoting health behavior change (Hawkins et al., 2008; Latimer et al., 2010). Tailored messages are customized to each individual (Noar et al., 2009) using strategies and information intended to reach a specific person, based on characteristics that are unique to that person (Kreuter et al., 1999) because these strategies for individualizing messages increase the likelihood that people will view the message as relevant to them and consciously choose to make and sustain healthy behavior changes. Over the last decade, faculty and staff of the Center for Research on Men’s Health at Vanderbilt University have worked to achieve men’s health equity by developing and testing an approach to individually-tailor behavioral weight loss interventions for middle-aged and older African American men (Griffith & Jaeger, 2020).

We begin this paper by describing the theory, approach, and conceptual foundation of how we tailor text messages to African American men. After describing the epidemiologic reasons we focus on middle-aged African American men, we detail how we individualize messages and what is unique about our tailoring approach. Then we illustrate how we use African American Manhood to tailor messages to this population in ways that consider the heterogeneity among African American men.

We recognize that our empirically derived framework and messages are heteronormative and designed primarily for cisgender African American men who are middle-aged or older. We view the specificity of the identities that our messages speak to as a strength of our tailoring methodology because it allows us to increase the salience and perhaps the impact of our messages for our population. The scope and focus of our messages are shaped by the qualitative data collected in a midsized Midwestern city and a midsized Southeastern city. As a result, there are a range of masculinities and identities for which our framework, messages and interventions may not be ideal. Yet, to our knowledge, we are the first to demonstrate that it is possible to use an intersectional approach to tailor individual health messages for a specific group whose experiences are shaped by their race, ethnicity, age, and gender. This approach, therefore, could be used to develop messages for populations that would not resonate with our messages as currently designed. We conclude this paper with a discussion of the future of intersectional, identity-based tailoring and how it may be a useful strategy to continue to use a strengths-based approach that is consistent with notions of promoting minority health (Duran & Pérez-Stable, 2019a) and men’s health equity (Griffith, Bruce, et al., 2019).

Background of Tailoring Strategy

Our approach to tailoring is unique in that it combines evidence-based behavior-change goal algorithms to produce weight loss (Greaney et al., 2009) with tailoring to African American manhood (Griffith, Pennings, et al., 2019), but this paper focuses on the latter aspect of tailoring to the heterogeneity in manhood. The approach is an illustration of how tailoring can incorporate an intersectional approach that integrates age, race, ethnicity, and gender to increase the salience of health messages to a population for whom all of these factors are relevant to their identity and health behavior through the concept of African American manhood (Griffith, 2012; Griffith, 2016; Griffith, 2020). Next, we will describe our tailoring approach and explain why and how we locate the lived experience of our population of interest in messages to promote their health and well-being.

Theoretical Foundations

Our tailoring strategy combines Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) and self-efficacy (Bandura, 2004). A fundamental aspect of Self-Determination Theory, autonomous motivation is key because it is the primary factor that helps men overcome modifying factors that constrain opportunities and motivation to engage in healthier behaviors (Ryan & Deci, 2000). The autonomously motivated individuals not only see the importance of the behavior, but also connect change with their core values and beliefs. These individuals feel competent, are ready to take action and persist when faced with obstacles and have identified meaningful reasons for change (Ryan & Deci, 2000). In addition to autonomous motivation, the second key mediating mechanism is to increase self-efficacy, or the confidence one has in his ability to exert control over his own motivation, behavior, and social environment (Bandura, 2004). Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 2004) posits that self-efficacy affects health behavior directly and indirectly through its impact on goals, outcome expectations, and perceived facilitators and impediments. Thus, an important objective of health interventions is to increase the perceived ability to engage in healthier behavior despite environmental, social, and time pressures that may present barriers to healthy eating or physical activity. An intersectional approach that helps to capture the structural foundation of these factors and how they intersect in the lives of specific populations is critical to the process of developing messages for populations defined by the combination of age, race, gender, and other factors.

Intersectionality

Building on the work of Kimberlé Crenshaw and others (Bowleg, 2017b; Crenshaw, 1995), we use an intersectional approach as the foundation of our tailoring strategy. An intersectional approach suggests that socially defined and socially meaningful characteristics are inextricably intertwined and experienced simultaneously. Consideration of how the blending of identities and experiences creates a new understanding of these factors helps researchers understand the complex array of factors that affect men’s health and well-being (Griffith, 2012; Ragonese et al., 2019). Men’s health should consider how micro structures may relate to how men navigate the precarious, racialized, and class bound aspects of manhood (Griffith, 2015; Vandello & Bosson, 2013), and how macro-structures that may be related to the diverse and socially contingent nature of masculinities in their social and economic context (Griffith, 2018; Robertson et al., 2016). Intersectionality provides a systematic way to explore how sex and gender affect men’s health, yet these determinants of men’s health also rely on other identities, characteristics and categories for meaning as determinants of health (Gilbert et al., 2016; Griffith, 2012). More specifically, we use an intersectional approach to capture aspects of a Social Ecological Framework of health behavior that define and influence the social, economic, built, and natural environment (McLeroy et al., 1988).

Observable (e.g., skin color, eye shape), psychosocial (e.g., sexual orientation, racial identity, ethnic identity, social class, economic position), and cultural (e.g., religion, Meritocracy, American Creed, homophobia) characteristics beyond sex, are necessary preconditions for understanding men’s health and an intersectional approach provides a framework for considering these factors (Griffith, 2016). Intersectional approaches to men’s health offer a way to examine why sex does not have the same meaning and influence within and across all men’s lives or health outcomes (Griffith, 2012). Intersectional approaches help to highlight how dynamic cultural factors shape the norms, expectations, stressors, and practices in men’s lives. An intersectional approach offers an important lens through which we may fine-tune intervention strategies (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, 2016) and health communication. The health communication messaging strategy that we have developed and described below does not seek to help men change these environmental factors; rather our goal is to use health messages to increase motivation, self-efficacy, and other psychosocial factors that can help men overcome structural and environmental constraints and limitations (Bandura, 2004; Griffith & Jaeger, 2020).

Manhood

Manhood is a social status and aspirational identity that perpetually needs to be proven; it reflects the embodiment of virtuous characteristics and traits, performance of social roles, and the fulfillment of gendered expectations associated with being an adult male that need to be proven continually (Vandello et al., 2019). Men need not engage in all masculine behaviors to be considered a man, but the more masculine behaviors men enact the greater likelihood that he will be respected as a man. One of the most enduring qualities of manhood is not its contents— stereotypically male qualities, behaviors, preferences, or tendencies—but the constant anxiety of its precariousness (Griffith, 2015; Griffith et al., 2015; Vandello et al., 2019). Manhood includes men’s perceived ability to fulfill heteronormative social and cultural ideals and expectations beyond the achievement of age-related milestones or the presence of secondary sex characteristics (Griffith, 2015). A complex construct that is shaped by race/ethnicity, age, and other factors, manhood serves as a lens through which African American men, in particular, see and identify themselves and are recognized by others as men (Griffith, 2015; Griffith & Cornish, 2018). Dimensions and ideals of manhood that shape how African American men see themselves and are viewed by others are shaped by race and class (Griffith, 2015; Kimmel, 2006).

Manhood is relationally constructed and reflects interconnections between self, family, and others; it is defined and exists in comparison with expectations of younger males and ideals and expectations of women and womanhood (Griffith, 2015). Among African American men, Whitehead and colleagues found that manhood status that comes from engaging in risky behavior may be associated with efforts to build a strong reputation, and that aspects of anti-femininity may be associated with efforts to achieve a level of respectability pursued through economic success, educational attainment, and upward social class mobility (Whitehead, 1997). Aspects of hegemonic ideals of masculinity have been associated with ideals that Whitehead (1997) characterizes as reputational aspects of demonstrating or performing masculinity (e.g., avoiding medical help-seeking, alcohol use, sexual risk taking, reckless driving) and that are associated with poor health outcomes (Ragonese et al., 2019). Caballerismo – the ideal of being a gentleman and one who may be more family oriented – is consistent with Whitehead’s notion of the respectability aspect of masculinity (Whitehead, 1997). Conceptually, these strains and conflicts are rooted in the ideals of Caballerismo or the Victorian values that made one a virtuous member of a society who demonstrated character (e.g., self-control, honesty, thrift) (Summers, 2004).

Middle age

Middle age covers a large portion of an individual’s lifespan from approximately age 30 to 64 (Lachman, 2015), but chronological age may not be the best anchor for identifying middle age (Lachman, 2015). Because the boundaries are not solidly defined by numerical age, middle age may be better considered in terms of or the assumption of certain social roles and responsibilities, the timing of events, and life experience (Lachman, 2015). Evidence exists that stresses involving multiple role demands or financial pressures may cluster in or take a greater toll in middle age (Lachman, 2015). In middle age, men often construct their identities in relation to the physicality of their work, the level of income or status that their labor produces, or both because work defines their status in the masculine hierarchy (Evans et al., 2011). Consistent with this focus on work and financial provision in midlife, role strain and adaptation theory suggests that during their middle-adult years, men’s, particularly African American men’s, evaluations of how well they feel they are fulfilling the roles of provider, husband, father, employee, and community member become fundamental aspects of their identities and a major focus of this phase of life (Bowman, 1989).

For these reasons, we focused on men in this phase of life because middle age is when African American men’s efforts to fulfill the roles of provider, husband, father, and community member have been found to be key barriers to healthy eating and physical activity (Griffith, Gunter, & Allen, 2011; Griffith, Wooley, et al., 2013). African American men’s rates of physical activity tend to decline during middle age in part due to increasing responsibilities to fulfill social and cultural roles associated with work, family, and the community (Griffith et al., 2011). Particularly during this phase of life, men often define health by how they generally feel and whether they can complete activities of daily living (e.g., work, engage in sexual behavior) and function in roles (e.g. provider, father, spouse) that are important to them, their partners, and their families (Griffith, Ellis, et al., 2013).

Middle-aged African American Men’s Health

For more than 100 years the National Center for Health Statistics has documented that African American men in the US have had a shorter life expectancy than all other race by sex groups (National Center for Health Statistics, 2017). Last year, amid findings that life expectancy in the US declined three years in a row, Bilal and Diez-Roux attributed the national decline in life expectancy to non-Hispanic Black men, the only group whose mortality increased during that time (Bilal & Diez-Roux, 2018). African American men are the least likely race by gender group in the US to reach retirement age, and affluence, healthy lifestyles, and access to high-quality healthcare do not appear to be equally protective of these men when compared with other men or women (Gilbert et al., 2016).

Research on middle age has demonstrated for some time that disparities—particularly by race and sex—are greatest during middle age, and that is due primarily to the poor health and high mortality rates of middle-aged and older African American men (Griffith, Jaeger, et al., 2019; Satcher et al., 2005). Whereas chronic diseases are often viewed as primarily an issue for older adults, globally, almost half of chronic disease deaths occur in people under 70 years old, and 25% of chronic disease deaths occur in people under 60 years old (Griffith, Jaeger, et al., 2019; World Health Organization, 2018). Among racial/ethnic groups of men, African American men have the second highest rates of grade 2 obesity (BMI >=35) and the highest rates of grade 3 obesity (BMI>=40) (Flegal et al., 2010). Among African American men, those who are middle-aged (40–59 years old) have higher rates of obesity than African American men who are young adults (20–39 years old) or older adults (60 and older) (Flegal et al., 2010). Among men 40–59 years old with grade 3 obesity (BMI>=40), rates for African American men are 50% higher than their White counterparts (Flegal et al., 2010).

Tailoring to Middle-Aged African American Men

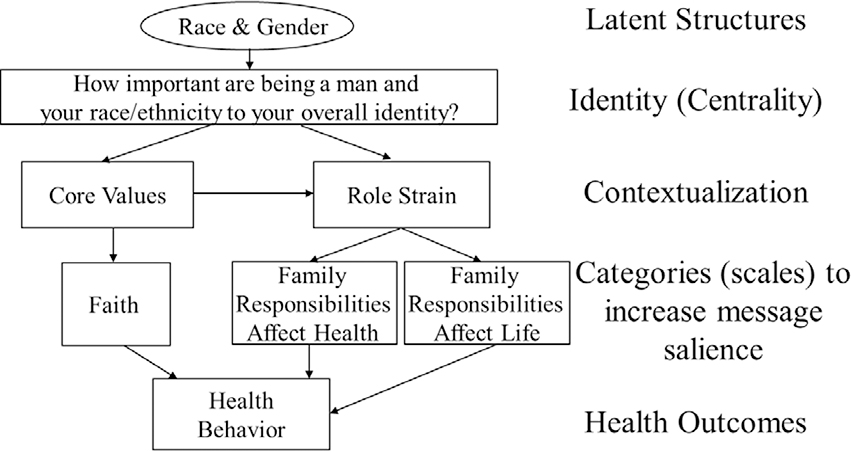

To increase the potential that messages will resonate with recipients, we use two levels of tailoring: one that focuses on the centrality of factors related to identity and a second that focuses on contextualizing messages to increasing their salience to men’s foundational principles and sources of chronic stress and psychological strain (see Figure 1). This approach builds on the work of Ken Resnicow and colleagues (Davis et al., 2010; Resnicow et al., 2009). Figure 1 builds from a model developed by LaVeist that helps researchers studying race and ethnicity to be more critical of the way they conceptualize, operationalize and utilize these terms in empirical research (La Veist, 1996). Griffith (2012) adapted this framework to highlight how race, ethnicity, gender, and age reflect pathways and determinants of men’s health. Griffith’s (2012) adaptation of the framework, is designed to move beyond identifying which social characteristics affect health to articulating why those factors affect health, and how they come together to influence a population’s health. Structural factors, and the physical features (e.g., skin color, hair texture, facial hair) that serve as indicators of them, trigger physiological and behavioral responses that affect health outcomes (Griffith, 2020). These responses are shaped by how core certain aspects of identity are to how one sees themselves and how salient the aspects of identity are to a particular situation or context.

Figure 1.

Framework for tailoring to African American manhood.

Tailoring based on the Centrality of Psychosocial Identity

Centrality is the extent to which one typically defines himself with regard to race or some other aspect of his identity (Sellers et al., 1998). It is a relatively stable construct that is not likely to change by situation, context, or event, and centrality represents the most important ways of seeing oneself. Based on our formative research using an intersectional approach (Griffith & Cornish, 2018), we asked men about the centrality or importance of being a man to their overall identity and the importance of being Black or African American to their overall identity. The questions ask, “On a scale of 0–10 with 0 being ‘not at all important’ and 10 being ‘very important’, how important is [manhood or race] to your overall identity?” For both questions, a response of 0–5 was categorized as ‘low’, and a response of 6–10 was categorized as ‘high’.

Tailoring based on the Contextualization of Core Values and the Strain of Social Roles

Although centrality is considered stable, salience is contextually dependent. Salience has been described as the mechanism through which all other identities operate and as the mediating process between the more stable characteristics of identity and the way individuals construe and behave in specific situations (Sellers et al., 1998). Sellers et al. (1998) argue that salience refers to the extent to which the stable aspect of identity (i.e., centrality) is relevant to one’s self-concept at a particular moment, in a particular situation, or in reference to a particular behavior. Salience is shaped by the context of the situation and one’s proclivity to define oneself, and one’s self-concept, in terms of that aspect of his identity.

Our formative research found that considering core values (i.e., religion and spirituality) and role strains (e.g., family responsibilities that affect health and family responsibilities that affect life) were important contextual factors that could be used to increase the salience of improving specific health behaviors for their lives and goals (see Figure 1). Griffith and Cornish (2018) found that religion and spirituality were fundamental to how middle-aged and older African American men defined manhood and their core values. African American men who were interviewed as part of the study described that their faith reshaped and redefined gendered roles (e.g., being a father) and helped them to find greater meaning and motivation to be better men through the integration of spirituality and manhood (Griffith & Cornish, 2018). Research has consistently shown that African Americans are more involved in religious practices and more consistently engage in prayer than White Americans (Gillum & Griffith, 2010). Even among African Americans who are not affiliated with a specific religious institution or those that do not attend services, prayer is often regarded as an important part of their lives (Gillum & Griffith, 2010).

In addition to the core value of faith (religiosity and spirituality), we focus on how men experience psychological strain from their perceived and actual ability to achieve life goals that may be associated with racialized and gendered social priorities (Bowman, 1989; Griffith et al., 2011). These psychological strains can be divided by how family roles, responsibilities, and priorities affect health (Family Responsibilities Affect Health – FRAH) and how these factors affect men’s lives more generally (Family Responsibilities Affect Life – FRAL). Role strains were critical factors that represented values and goals men perceived as most important to their identities and life goals (e.g., providing for their families, being a good spouse/partner). These values and goals were often more important to them and their loved ones than focusing on health behaviors like healthy eating and physical activity (Griffith et al., 2011; Griffith, Wooley, et al., 2013).

Operationalizing Centrality Using African American Manhood as an Example

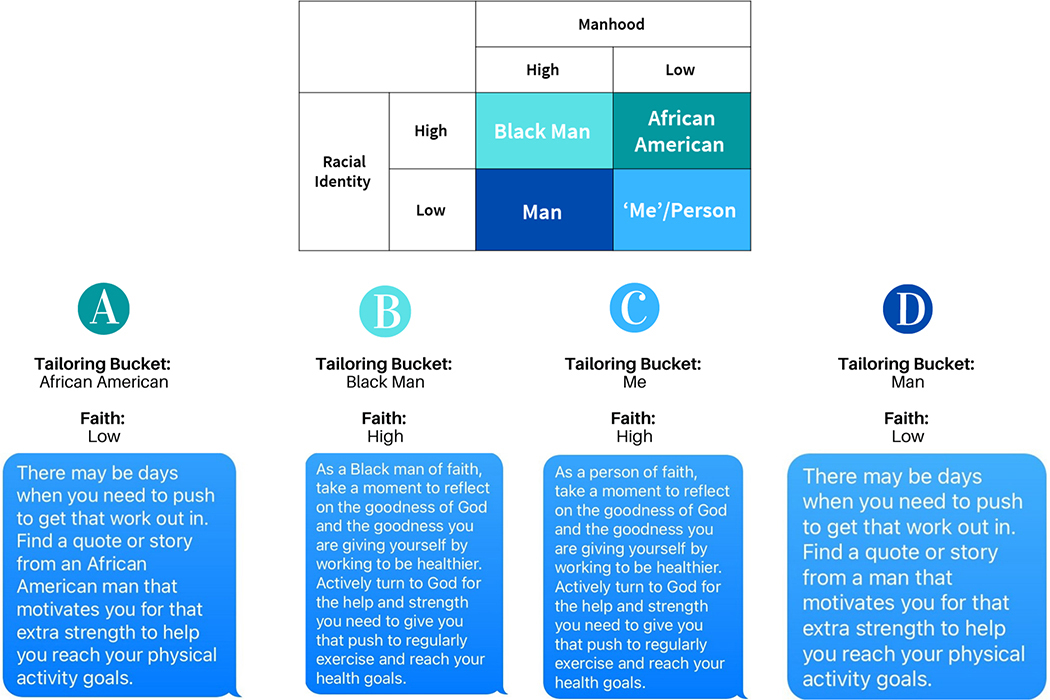

Combined responses from the two centrality items (manhood and race) resulted in a 2 × 2 table (Table 1) that determined the stem of each tailored message. The relationship between the constructs of interest and items on the centrality of identities reinforces the importance of utilizing an intersectional approach to understanding African American men’s identities. This is because African American men’s identities are an amalgamation of race and gender in a way that creates something distinct from racial or ethnic identity and gender identity alone (Bowleg et al., 2017; Griffith, 2012, 2015).

Table 1.

Centrality: Manhood and Racial Identity

| Manhood | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | ||

| Racial Identity | High | Black Man | African American |

| Low | Man | ‘Me’/Person | |

The four resulting categories, which we refer to as buckets, represent the first level of tailoring: Man, Black Man, African American, and Me or Person. These buckets provide a level of segmentation and heterogeneity in how African American men may consider how important race and manhood are to how they see themselves. For example, an individual who rated both manhood and race high would receive messages from the Black Man bucket. An individual who rated both manhood and race low would receive messages from the Me or Person bucket.

Operationalizing Salience Using African American Manhood as an Example

The variables within the second level of tailoring are designed to increase the salience of the messages to middle-aged and older African American men’s lives and health. The questions that make up each variable within both levels of tailoring are listed within Table 2. This level of tailoring is designed to tap into men’s core values and life goals in ways that will be memorable (Cooke-Jackson & Rubinsky, 2018) and in ways that tap into autonomous sources of motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Table 2.

Survey questions for each tailoring variable

| Variable | Source of Item | Survey questions for each variable | Tailoring Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Level of Tailoring: Racial & Gender Centrality | |||

| Manhood x Race: (Scale of 0=Not at all important to 10= Very important) |

Sellers et al. (1998) - Scoring instructions for the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI), Sellers –Multidimensional model of racial identity | • How important is being African American to your overall identity? • How important is being a man to your overall identity? |

High/Low score for each question places men into one of four ‘buckets’: • Black Man (High Manhood/High Race) • Man (High Manhood/Low Race) • African American (Low Manhood/High Race) • Me/Person (Low Manhood/Low Race) |

| Second level of Tailoring: Salience | |||

| Family Responsibilities Affect Health (FRAH): (Scale of 1= Strongly disagree to 5=Strongly agree) |

Gender Role Conflict Scale –Factor 4 –conflicts between work and family relations (O’Neil, Helms, Gable, David, & Wrightsman, 1986) and additional CRMH adapted items | • I feel torn between my family responsibilities and caring for my health. • My family responsibilities affect the amount of time I spend on my health. • Finding time to exercise is difficult for me because of family obligations. |

Sum of scale produces High (7–15)/Low (0–6) score for FRAH variable. |

| Family Responsibilities Affect Life (FRAL): (Scale of 1= Strongly disagree to 5=Strongly agree) |

Gender Role Conflict Scale –Factor 4 –conflicts between work and family relations (O’Neil et al., 1986) and additional CRMH adapted items | • My family responsibilities keep me from pursuing other leisure time physical activities (going on walks, playing sports with friends, etc.) • My family responsibilities often disrupt other parts of my life (health or leisure). • The stress I feel from a need to fulfill family responsibility affects/hurts my life. |

Sum of scale produces High (7–15)/Low (0–6) score for FRAL variable. |

| Faith: (Scale of 0=Never to 5=Many times a day) |

Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale –6 item version of the scale used in the Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiosity and Spirituality developed by selection of items from the Daily Spiritual Experiences scale (Underwood & Teresi, 2002) | • I feel God's presence • I feel strength and comfort in my religious or spiritual tradition • I feel deep inner peace and harmony • I desire to be closer to or in union with God • I am spiritually touched by the beauty of creation • I feel God's love for me, directly or through others |

Sum of scale produces High (25–30)/Low (0–24) score for Faith variable. |

Illustrating How We Tailor to African American Manhood

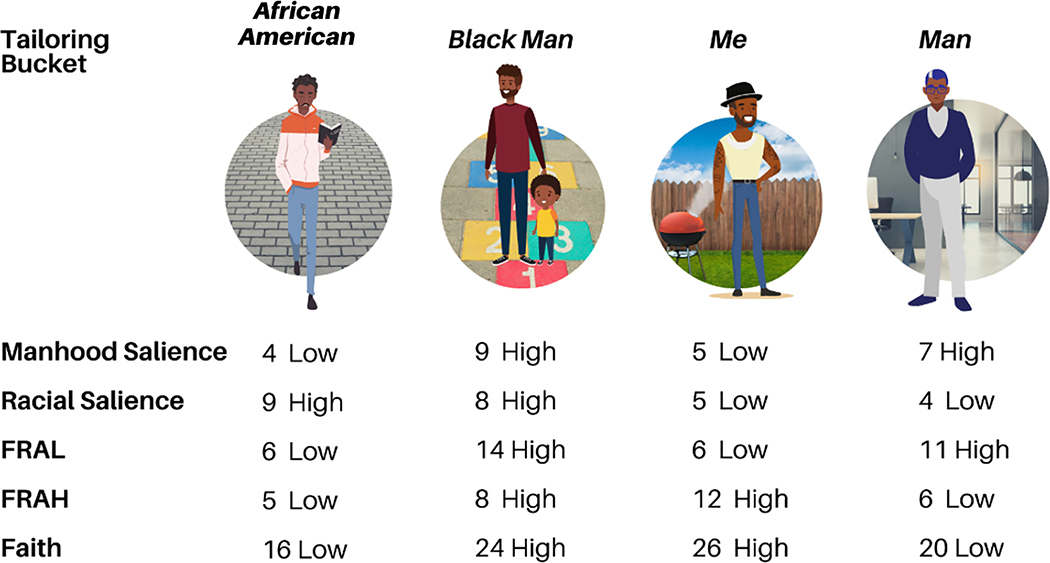

Let’s consider four illustrative examples of African American men (Figure 2). Each man is unique, and each has different goals, values, beliefs, and perceptions related to manhood. Differences in perceptions of manhood have an impact on individual, interpersonal, community, and societal factors that are dynamic and change over time (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). Societal-level factors like racism, gendered norms and values, social expectations of men across the lifespan (i.e., young adult vs. middle-aged vs. older adulthood) may further contextualize perceptions of manhood and health. In addition to those unique goals and values, each man also has distinctive demographic characteristics that shape and inform his interactions with others and frame his understanding and experiences related to health.

Figure 2.

Illustrative examples of how the tailoring framework would be applied to four African American men with different tailoring bucket and variable scores.

A is a single, 36-year-old man with no children living close to downtown, which allows him to bike to work. B is a married 41-year-old man and a father of two young children. His family recently moved further outside the city to be closer to the children’s school and activities. C is a married 53-year-old with three children, two of which are in college and one still living at home. He will soon be an ‘empty nester’ and is interested in re-discovering new hobbies and interests. D is a divorced 64-year-old man who has two grown children and three young grandchildren. He recently downsized to a home that requires less upkeep and is closer to his grandchildren. This group of men is heterogeneous, with individual experiences that are reflective of age intersecting with gendered perceptions and ideals, which are key factors that distinguish manhood from masculinity. As these men age, gain new experiences, reflect, improve, and navigate challenges, their perceptions of manhood change.

Additionally, each man in our illustration has different psychosocial priorities and faces different role strains, some of which are anchored in his phase of life, that shape how he actively engages in health promoting behavior (Bowman, 1989; Griffith et al., 2011). Young man A is not currently experiencing health difficulties. He is generally aware of things he can do to prevent later-in-life disease and he is mindful of a family history of breast cancer and aggressive prostate cancer. However, his own health and the impact it may have on his friends and family is not yet an immediate concern. He supports his friends’ attempts at healthier living, but considers his bike ride to and from work sufficient physical activity for the day. Young father, B, tries to set a healthy example for his family but struggles to make time for a regular workout regimen around busy schedules. Family is a priority right now, and often times other things, such as health, sleep, and self-care activities get pushed to the side. He and his wife are mindful of nutrition for the kids, but healthy meals for themselves can sometimes be a challenge when the easier option is a fast-food drive-thru or takeout from a restaurant. He is active at church and is trying to establish a social network of other dads in the congregation to help learn more about how to teach his children about faith. C is starting to experience symptoms of age-related conditions and has friends and family who are beginning to develop hypertension, type 2 diabetes and colon cancer. This has added some strain in that he worries more about his family and their overall health but does not feel that this affects other larger aspects of his life as a whole. Now that he has time, he dedicates himself to a fitness regimen and is more involved in the men’s ministry at his church. Retired grandfather, D, is experiencing symptoms of aging and age-related conditions. With changing family roles of being a grandfather, he feels that family time and strain plays more of an impact in his overall life and has little impact on his health. His doctor has prescribed a healthy diet and exercise regimen which he does his best to follow carefully. While each of these men have different experiences with health and health promoting behavior, they also have different motivations to strive to become healthier.

Each secondary tailoring variable from Table 2 received a high/low categorization option based on survey factor scoring and informed which message within an individual’s designated bucket he would receive. Each of our men represent a different tailoring bucket with individual scores for each tailoring variable that makes him unique (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Examples of sample messages for each man based on his unique bucket and tailoring variable scores.

The resulting messages incorporated key goals, values, and important traits and characteristics of the individuals, and utilized language used by men themselves. While the messages had a stronger focus on centrality, they began to focus on message salience for each individual man. Figure 3 presents sample messages for each man based on his unique bucket and tailoring variable scores. Subtle differences in how each message was framed sought to highlight the differences in centrality and the content of each message aimed to increase the salience of the message for health. In Figure 3, family responsibilities are highlighted for those who indicated that they felt strongly that family responsibilities affect their life, in addition to the differing message stem for each bucket. The addition of the mention of family increases the salience of the message by acknowledging that importance of the role that individual perceives he plays as a member of that family and often times as a man, and the head of the household.

Discussion

While there is a large body of research that has demonstrated the benefits of individually tailored health messages over messages that are not individualized (Kreuter et al., 1999; Noar et al., 2009), research considering the centrality and salience of identity-based factors remains limited. While there have been efforts to target and tailor health messages to African Americans (Davis et al., 2010; Kreuter et al., 1999; Resnicow et al., 2009), more research is needed to advance efforts to utilize individually-tailored health messages in minority health research. While tailoring to racial or ethnic identity has shown some benefits (Resnicow et al., 2009), using an intersectional approach is one of the next steps to embrace and advance if the goal is to improve minority health and to achieve health equity (Duran & Pérez-Stable, 2019a, 2019b).

In this paper, we argued for and sought to operationalize a strategy to utilize an intersectional approach to use health messages in a minority health intervention. We acknowledge that we have only scratched the surface of this approach and there are numerous other ways that the effectiveness of identity-based tailoring and using an intersectional approach may be used in pursuit of health equity. Additional formative research is needed to further identify candidate constructs that can be used in future health messages interventions with African American men, but hopefully our framework will be useful fodder for future efforts to improve the health of this and other populations.

We believe the focus on the centrality and salience of identity may be particularly important for other populations. As we illustrated with four examples of middle-aged or older African American men, there is considerable heterogeneity in a group that is often thought to be homogenous. Determining what aspects of identity and experience are most central to how people see themselves is an important foundational principle on which to build future intervention strategies (Davis et al., 2010). Building on the pioneering work of Ken Resnicow and colleagues (Davis et al., 2010; Resnicow et al., 2009), we believe our efforts to add to their approach by considering not only ethnic/racial identity but also gender is novel and consistent with the work on intersectionality in health equity research that has been led by Lisa Bowleg and others in recent years (Bauer & Scheim, 2019; Bowleg, 2017a, 2017b; Bowleg et al., 2017). We recognize that our approach only begins to touch on how men might see themselves and what might motivate them to engage in healthier behavior, but we also believe that we have outlined and advanced strategies and principles that may be a foundation for others.

One of the obvious next directions for this work would be to explore the centrality and salience of sexual orientation and non-binary gender identity for tailoring health messages (Fields et al., 2014; Ramos et al., 2019). Sexual and gender identity may be relevant aspects of identity centrality but perhaps less germane or salient to health behaviors like eating practices, physical activity, or sedentary behavior. Furthermore, it will be critical to consider how factors associated with sexual orientation and non-binary gender identity relate to the faith and role strain salience factors that are present in our current model. We recognize that sexual and gender identity are central and salient to men’s identities and health behaviors in ways that may intersect with, expand and fundamentally reimagine how we conceptualize and tailor to African American manhood (Griffith, Pennings, et al., 2019) and other identity-based constructs.

Conclusion

Individual tailoring of health messages may be a particularly important strategy for promoting minority health and achieving health equity, but this approach may be more effective if it incorporates an intersectional approach. Research on minority health and health equity should consider not only the factors that are most important in defining people’s sense of self and the factors that may be most relevant to the health behaviors of interest. Researchers should continue to systematically consider what factors are candidate tailoring variables while critically analyzing why those factors may be more or less important in promoting the health and well-being of specific populations.

Acknowledgements:

This paper has been supported in part by the American Cancer Society (RSG-15-223-01-CPPB) and NIIMHD (5U54MD010722-02).

References

- Bandura A (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior, 31(2), 143–164. 10.1177/1090198104263660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR, & Scheim AI (2019). Advancing quantitative intersectionality research methods: Intracategorical and intercategorical approaches to shared and differential constructs. Social Science & Medicine, 226, 260–262. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilal U, & Diez-Roux AV (2018). Troubling trends in health disparities. New England Journal of Medicine, 378(16), 1557–1558. 10.1056/NEJMc1800328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2017a). Intersectionality: An underutilized but essential theoretical framework for social psychology. In Gough B (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of critical social psychology (pp. 507–529). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2017b). Towards a critical health equity research stance: Why epistemology and methodology matter more than qualitative methods. Health Education & Behavior, 44(5), 677–684. 10.1177/1090198117728760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, del Río-González AM, Holt SL, Pérez C, Massie JS, Mandell JE, & Boone A, C. (2017). Intersectional epistemologies of ignorance: How behavioral and social science research shapes what we know, think we know, and don’t know about U.S. Black men’s sexualities. The Journal of Sex Research, 54(4–5), 577–603. 10.1080/00224499.2017.1295300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman PJ (1989). Research perspectives on Black men: Role strain and adaptation across the adult life cycle. In Jones RL (Ed.), Black adult development and aging (pp. 117–150). Cobb & Henry Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1994). Ecological models of human development. Reprinted in Gauvain M & Cole M (Eds.), Readings on the development of children, 2nd Ed. (pp.37–43). Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke-Jackson A, & Rubinsky V (2018). Deeply rooted in memories: Toward a comprehensive overview of 30 years of memorable message literature. Health Communication, 33(4), 409–422. 10.1080/10410236.2016.1278491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1995). Critical race theory: The key writings that formed the movement. The New Press: Distributed by W.W. Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Davis R, Alexander G, Calvi J, Wiese C, Greene S, Nowak M, Cross WE Jr., & Resnicow K (2010). A new audience segmentation tool for African Americans: The Black identity classification scale. Journal of Health Communication, 15(5), 532. 10.1080/10810730.2010.492563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran DG, & Pérez-Stable EJ (2019a). Novel approaches to advance minority health and health disparities research. American Journal of Public Health, 109(S1), S8–S10. 10.2105/ajph.2018.304931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran DG, & Pérez-Stable EJ (2019b). Science visioning to advance the next generation of health disparities research. American Journal of Public Health, 109(S1), S11–S13. 10.2105/ajph.2018.304944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis KR, Griffith DM, Allen JO, Thorpe RJ Jr, & Bruce MA (2015). “If you do nothing about stress, the next thing you know, you’re shattered”: Perspectives on African American men’s stress, coping and health from African American men and key women in their lives. Social Science & Medicine, 139, 107–114. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.06.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J, Frank B, Oliffe JL, & Gregory D (2011). Health, illness, men and masculinities (HIMM): A theoretical framework for understanding men and their health. Journal of Men’s Health, 8(1), 7–15. 10.1016/j.jomh.2010.09.227 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fields EL, Bogart LM, Smith KC, Malebranche DJ, Ellen J, & Schuster MA (2014). “I always felt I had to prove my manhood”: Homosexuality, masculinity, gender role strain, and HIV risk among young Black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 105(1), 122–131. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, & Curtin LR (2010). Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. Journal of the American Medical Association, 303(3), 235–241. 10.1001/jama.2009.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier MS, Williams GC, Sweet SN, & Patrick H (2009). Self-Determination theory: Process models for health behavior change. In DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, & Kegler M (Eds.), Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research: Strategies for improving public health (Vol. 2, pp. 157–183): Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert KL, Ray R, Siddiqi AA, Shetty S, Baker EA, Elder K, & Griffith DM (2016). Visible and invisible trends in African American men’s health: Pitfalls and promises for addressing racial, ethnic and gender health inequities. Annual Review of Public Health, 37, 219–311. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum F, & Griffith DM (2010). Prayer and spiritual practices for health reasons among American adults: The role of race and ethnicity. Journal of Religion and Health, 49(3), 283–295. 10.1007/s10943-009-9249-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaney M, Quintiliani L, Warner E, King D, Emmons K, Colditz G, Glasgow RE, & Bennett G (2009). Weight management among patients at community health centers: The “Be Fit, Be Well” study. Obesity and Weight Management, 5(5), 222–228. 10.1089/obe.2009.0507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM (2012). An intersectional approach to men’s health. Journal of Mens Health, 9(2), 106–112. 10.1016/j.jomh.2012.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM (2015). “I AM a Man”: Manhood, minority men’s health and health equity. Ethnicity and Disease, 25(3), 287–293. 10.18865/ed.25.3.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Bruce MA, Thorpe RJ Jr, & Metzl JM (2015). The interdependence of African American men’s definitions of manhood and health. Family and Community Health, 38(4), 284–296. 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM, Bruce MA, & Thorpe RJ Jr (2019). Introduction. In Griffith DM, Bruce MA & Thorpe RJ Jr (Eds.), Men’s health equity: A handbook (pp. 3–9). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM, & Cornish EK (2018). “What defines a man?”: Perspectives of African American men on the components and consequences of manhood. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 19(1), 78–88. 10.1037/men0000083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM, Ellis KR, & Allen JO (2013). An intersectional approach to social determinants of stress for African American men: Men’s and women’s perspectives. American Journal of Men’s Health, 7(4S), 16–27. 10.1177/1557988313480227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM, Gunter K, & Allen JO (2011). Male gender role strain as a barrier to African American men’s physical activity. Health Education & Behavior, 38(5), 482–491. 10.1177/1090198110383660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM, & Jaeger EC (2020). Chapter Nine - Mighty Men: A faith-based weight loss intervention to reduce cancer risk in African American men. In Ford ME, Esnaola NF, & Salley JD (Eds.), Advances in cancer research (Vol. 146, pp. 189–217): Academic Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM, Jaeger EC, Sherman LD, & Moore HJ (2019). Middle-Aged men’s health. In Griffith DM, Bruce MA & Thorpe RJ Jr (Eds.), Men’s health equity: A handbook. (pp. 72–85). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM, Pennings JS, Bruce MA, & Ayers GD (2019). Measuring the dimensions of African American Manhood: A factor analysis. In Griffith DM, Bruce MA & Thorpe RJ Jr (Eds.), Men’s health equity: A handbook (pp. 101–126). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM, Wooley A, & Allen JO (2013). “I’m ready to eat and grab whatever I can get.” Determinants and patterns of African American men’s eating practices. Health Promotion Practice, 14(2), 181–188. 10.1177/1524839912437789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins RP, Kreuter M, Resnicow K, Fishbein M, & Dijkstra A (2008). Understanding tailoring in communicating about health. Health Education Research, 23(3), 454. 10.1093/her/cyn004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel MS (2006). The masculine mystique. Manhood in America: A cultural history (pp. 173–191). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ, & Glassman B (1999). One size does not fit all: The case for tailoring print materials. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 21(4), 276. 10.1007/BF02895958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Veist TA (1996). Why we should continue to study race...but do a better job: aAn essay on race, racism and health. Ethnicity & Disease, 6(1–2), 21–29. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8882833/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME (2015). Mind the gap in the middle: A call to study midlife. Research in Human Development, 12(3–4), 327–334. 10.1080/15427609.2015.1068048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latimer AE, Brawley LR, & Bassett RL (2010). A systematic review of three approaches for constructing physical activity messages: What messages work and what improvements are needed? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 7(1), 36. 10.1186/1479-5868-7-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, & Glanz K (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351–377. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine. (2016). The Promises and Perils of Digital Strategies in Achieving Health Equity: Workshop Summary. The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics (US). (2017). Health, United States, 2016: With chartbook on long-term trends in health. Report No.: 2017–1232. [PubMed]

- Noar SM, Harrington NG, & Aldrich RS (2009). The role of message tailoring in the development of persuasive health communication messages. Annals of the International Communication Association, 33(1), 73–133. 10.1080/23808985.2009.11679085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil J, Helms B, Gable R, David L, & Wrightsman L (1986). Gender-role conflict scale: College men’s fear of femininity. Sex Roles, 14(5), 335–350. 10.1007/bf00287583 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ragonese C, Shand T, & Barker G (2019). Masculine norms and men’s health: Making the connections. Promundo-US. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos SR, Warren R, Shedlin M, Melkus G, Kershaw T, & Vorderstrasse A (2019). A framework for using ehealth interventions to overcome medical mistrust among sexual minority men of color living with chronic conditions. Behavioral Medicine, 45(2), 166–176. 10.1080/08964289.2019.1570074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Davis R, Zhang N, Strecher V, Tolsma D, Calvi J, Alexander G, Anderson J, Wiese P, & Cross WE Jr (2009). Tailoring a fruit and vegetable intervention on ethnic identity: Results of a randomized study. Health Psychology, 28(4), 394. 10.1037/a0015217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson S, Williams B, & Oliffe J (2016). The case for retaining a focus on “masculinities” in men’s health research. International Journal of Men’s Health, 15(1), 52–67. 10.3149/jmh.1501.52 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, & Deci EL (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satcher D, Fryer GE Jr., McCann J, Troutman A, Woolf SH, & Rust G (2005). What if we were equal? A comparison of the black-white mortality gap in 1960 and 2000. Health Affairs, 24(2), 459–464. 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers R, Smith M, Shelton N, Rowley S, & Chavous T (1998). Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2(1), 18–39. 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers MA (2004). Manliness and its discontents: The Black middle-class and the transformation of masculinity, 1900–1930. University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood LG, & Teresi JA (2002). The daily spiritual experience scale: Development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24(1), 22–33. 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandello JA, & Bosson JK (2013). Hard won and easily lost: A review and synthesis of theory and research on precarious manhood. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 14(2), 101–113. 10.1037/a0029826 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vandello JA, Bosson JK, & Lawler JR (2019). Precarious manhood and men’s health disparities. In Griffith DM, Bruce MA & Thorpe RJ Jr (Eds.), Men’s health equity: A handbook (pp. 27–41). Routledge [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead TL (1997). Urban low-income African American men, HIV/AIDS, and gender identity. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 11(4), 411–447. 10.1525/maq.1997.11.4.411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2018). Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-profiles-2018/en/.