Abstract

Background and objective

Little is known about the epidemiology and cost of bronchiectasis in Asia. This study describes the disease burden of bronchiectasis in Singapore.

Methods

A nationwide administrative dataset was used to identify hospitalisations with bronchiectasis as a diagnosis. Population statistics and medical encounter data were used to estimate the incidence, mortality, prevalence and direct medical costs associated with bronchiectasis requiring hospitalisation.

Results

There were 420 incident hospitalised bronchiectasis patients in 2017, giving an incidence rate of 10.6 per 100 000. Age-standardised incidence declined on average by 2.7% per year between 2007 and 2017. Incidence rates increased strongly with age in both men and women. Tuberculosis was a secondary diagnosis in 37.5% of incident hospitalisations in 2007, but has declined sharply since then. Patient survival was considerably lower in both men (5-year relative survival ratios (RSR) 0.63, 95% CI 0.59–0.66) and women (5-year RSR 0.75, 95% CI 0.72–0.78). The point prevalence of bronchiectasis was 147.1 per 100 000 in 2017, and increased sharply with age, with >1% of people aged ≥75 years having bronchiectasis. Total first-year costs among incident bronchiectasis patients in 2016 varied widely, with a mean±sd USD 7331±8863. Approximately 10% of the patients admitted in 2016 had total first-year costs of more than USD 14 380.

Conclusion

Bronchiectasis is common and imposes a substantial burden on healthcare costs and survival rates of patients in Singapore.

Short abstract

Bronchiectasis is common, with a prevalence >1% in older persons, and imposes a substantial burden on healthcare costs and survival rates of patients living with bronchiectasis in Singapore https://bit.ly/3iErV79

Introduction

Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis is characterised by permanent dilatation of the airways leading to persistent cough, sputum production, dyspnoea and recurrent exacerbations [1]. Epidemiological studies from the United States of America (USA) and Europe have highlighted the high prevalence and rate of hospitalisation of bronchiectasis, particularly among older people and women [2–5]. Few studies have been conducted in Asia. A national health survey in Korea reported that bronchiectasis was diagnosed in 0.8% of adults aged ≥40 years [6]. Studies in Asia suggest that post-tuberculosis (TB) is the commonest aetiology of bronchiectasis [7, 8].

In the USA, patients with bronchiectasis were associated with 2.0 additional hospital days per patient, 6.1 additional outpatient encounters and 27.2 additional days of antibiotic therapy in 2001. The healthcare cost per patient with bronchiectasis was USD 5681 higher than patients without [9]. In Germany, the healthcare cost for patients with bronchiectasis was a third higher than in matched controls, and antibiotic expenditures were nearly five times higher [10].

Singapore is an Asian city-state that has experienced rapid economic development in the past 60 years, accompanied by both epidemiologic and demographic transitions, resulting in an ageing population, low birth rate and relatively long life expectancies [11]. The major causes of disease burden are chronic noncommunicable conditions such as cancers, cardiovascular diseases and mental and neurological disorders [12]. The epidemiology of bronchiectasis in Singapore is unknown. In this article, we report the incidence, mortality and prevalence of bronchiectasis requiring hospitalisation in Singapore, as well as associated healthcare utilisation and costs.

Methods

Singapore has a mixed healthcare provision system with both private sector and public sector providers [13]. Overall, the public sector market share is ∼80% for hospital-based care, and 20% in primary care [13]. Healthcare in the public sector is heavily subsidised by the government. Subsidies are mean-tested in all healthcare settings, primarily using patient's per capita household income or individual monthly income, to ensure resources are better targeted at those who need them. Inpatient treatment at public acute hospitals receives ward subsidies of up to 80% [14]. At specialist outpatient clinics (SOCs) based in public hospitals and polyclinics providing subsidised primary care, subsidies are up to 70% for SOC services and 75% for medication. In primary care dominated by private players, the Community Health Assist Scheme enables Singaporeans from low- to middle-income families to receive subsidies for medical and/or dental care at accredited private general practitioner (GP) and dental clinics [15].

Study design

A Ministry of Health-hosted administrative database was used. This database contains de-identified individual-level hospitalisation records (containing demographic information, dates of admission and costs of hospitalisation, both before and after government subsidies, mortality information and primary and secondary discharge diagnoses coded using the ninth revision of the International Classification of Diseases, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM) for the years 1999–2011 and the tenth revision, Australian modification (ICD-10-AM) for the year 2012 and after) from all public and private acute hospitals for the years 1999–2017. The Ministry of Health conducts annual checks on the hospitalisation database to ensure its completeness. The database also contains records of visits at emergency departments, public SOCs and polyclinics as well as government-subsidised visits at private GP clinics. For these encounters, the diagnosis as well as the amount charged before and after government subsidies are available, except for SOC visits. To estimate public sector outpatient costs, we used a set of norm costs derived for the purposes of government subvention. All encounters were linked using anonymised patient identity numbers to give patient-level data. We considered the amount charged before subsidies as “costs”, and the amount post-subsidy as “bills”.

The period of analysis for this study is 2007–2017. Bronchiectasis was defined using ICD-9-CM 011.50–011.56 (tuberculous bronchiectasis), 494 (bronchiectasis) and 748.61 (congenital bronchiectasis), and ICD-10-AM J47 (bronchiectasis) and Q33.4 (congenital bronchiectasis). Incident hospitalised bronchiectasis for any year was defined as patients with a first admission for bronchiectasis as the primary diagnosis (i.e. without a prior admission for bronchiectasis as a primary cause). The prevalence of ever-hospitalised bronchiectasis was estimated as of 30 June 2017 by identifying all patients with a recorded inpatient hospitalisation of bronchiectasis as either the primary or secondary discharge diagnosis between 1 January 1999 and 30 June 2017, and removing those who died on or before 30 June 2017. We excluded patients who are not residents (Singapore citizen or Permanent Resident) of Singapore.

Analysis

Singapore's mid-year resident populations estimates from the Department of Statistics for 2007–2017 [16] were used, and age-standardisation was performed by the direct method using the 2017 population as the reference population.

Relative survival ratios (RSRs) [17] were derived using the Ederer II method [18] and from official life tables for Singapore stratified by sex, age and calendar year [19]. Survival was calculated from the date of first admission with bronchiectasis as a primary diagnosis to the date of death, or 31 December 2017, whichever came first. Poisson regression was used to model excess mortality associated with incident hospitalised bronchiectasis comparing two calendar periods of “first admission” 2012–2016 versus 2007–2011, adjusted for sex, age groups at incident hospitalisation and restricting the analysis to the first 5 years of follow-up.

Total inpatient and outpatient costs and patient bills were summed for a cost-of-illness analysis. All costs were adjusted to Singapore dollars (2017) using the general consumer price index in Singapore [20], and converted to US dollars at an exchange rate of USD 1=SGD 1.38 [21]. A societal perspective was adopted for this analysis.

All p-value and confidence intervals were set at a two-tailed statistical significance level of 0.05. Data analysis was performed using Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the National Healthcare Group domain-specific review board (reference 2018/00724).

Results

Incidence of hospitalised bronchiectasis

There were 420 incident hospitalised bronchiectasis patients in 2017, with an average annual growth rate of 1.6% per year between 2007 and 2017 (table 1). 54.0% of patients in 2017 were women, up from 45.3% in 2007, with a mean age of 70 years during the study period (2007–2017).

TABLE 1.

Incidence and profile of incident hospitalised bronchiectasis (as primary diagnosis), 2007–2017

| Year | CAGR 2017 versus 2007 (%) | |||||||||||

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | ||

| Total | 360 | 339 | 352 | 330 | 382 | 353 | 319 | 328 | 347 | 404 | 420 | 1.6 |

| Age-standardised incidence (per 100 000 persons) | 13.9 | 12.5 | 12.4 | 11.4 | 12.4 | 11.0 | 9.6 | 9.4 | 9.5 | 10.6 | 10.6 | −2.7 |

| Sex, % | ||||||||||||

| Female | 45.3 | 45.7 | 45.2 | 47.0 | 52.4 | 54.1 | 50.8 | 45.0 | 53.9 | 51.5 | 54.0 | |

| Male | 54.7 | 54.3 | 54.8 | 53.0 | 47.6 | 45.9 | 49.2 | 55.0 | 46.1 | 48.5 | 46.0 | |

| Age, years | 69.7±14.9 | 69.5±15.4 | 70.1±13.9 | 70.1±14.9 | 68.8±15.2 | 68.8±16.3 | 69.1±16.7 | 69.9±15.8 | 70.7±14.3 | 69.6±14.7 | 69.9±14.4 | |

| Age group, % | ||||||||||||

| <18 years | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.2 | |

| 18–39 years | 4.2 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.1 | |

| 40–64 years | 25.3 | 28.3 | 32.1 | 25.8 | 33.6 | 31.4 | 29.2 | 27.1 | 25.1 | 28.7 | 26.9 | |

| 65–74 years | 29.2 | 25.7 | 25.0 | 24.5 | 23.6 | 21.5 | 23.8 | 27.4 | 28.2 | 27.2 | 29.5 | |

| ≥75 years | 40.8 | 42.5 | 41.5 | 46.1 | 40.2 | 42.5 | 42.6 | 41.8 | 43.8 | 40.3 | 40.2 | |

| Ethnic group, % | ||||||||||||

| Chinese | 68.3 | 75.8 | 76.7 | 78.2 | 75.1 | 75.4 | 73.0 | 74.3 | 77.8 | 74.5 | 74.0 | |

| Malay | 18.9 | 15.9 | 14.2 | 10.3 | 13.1 | 13.0 | 15.7 | 14.1 | 12.4 | 13.1 | 15.2 | |

| Indian | 6.7 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 7.6 | 7.9 | 5.1 | 7.2 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 6.2 | |

| Others | 6.1 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 6.5 | 4.1 | 5.5 | 3.7 | 6.4 | 4.5 | |

Data are presented as n or mean±sd unless otherwise stated. Due to rounding, percentages may not add up precisely to 100%. CAGR: compound annual growth rate.

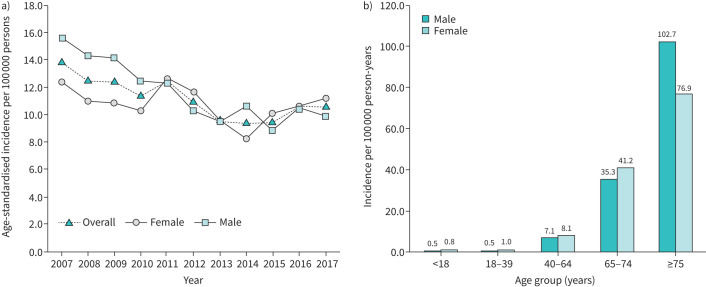

Age-standardised incidence has declined from 13.9 per 100 000 persons in 2007 to 10.6 per 100 000 persons in 2017 (an average decline of 2.7% per year). This decline was steeper among men (15.6 per 100 000 in 2007 to 9.9 per 100 000 in 2017, an average decline of 4.4% per year) than women (12.4 per 100 000 in 2007 to 11.2 per 100 000 in 2017, an average decline of 1.0% per year), and the age-standardised incidence rate of bronchiectasis in women was slightly higher than men in 2017. The incidence rate of bronchiectasis increased sharply with age for both men and women (figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

a) Age-standardised incidence of hospitalised bronchiectasis patients in Singapore by sex, 2007–2017; b) incidence of hospitalised bronchiectasis patients in Singapore by sex and age group, 2017.

Coexisting diagnoses

Most patients with incident hospitalisation-requiring bronchiectasis were admitted to public acute hospitals (average proportion of 95.9%). Of those admitted in 2017, the majority (86.4%) had at least one comorbidity. The most common comorbidity was hypertension (25.3%), followed by diabetes mellitus (23.1%) and hyperlipidaemia (19.3%). Chronic respiratory conditions such as COPD and asthma as comorbidities were relatively less common, and were diagnosed in 8.3% and 3.6%, respectively, of those admitted in 2017.

The prevalence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection as a comorbidity in the study population has declined during the period (37.5% in 2007 and 8.0% in 2017) (supplementary table S1).

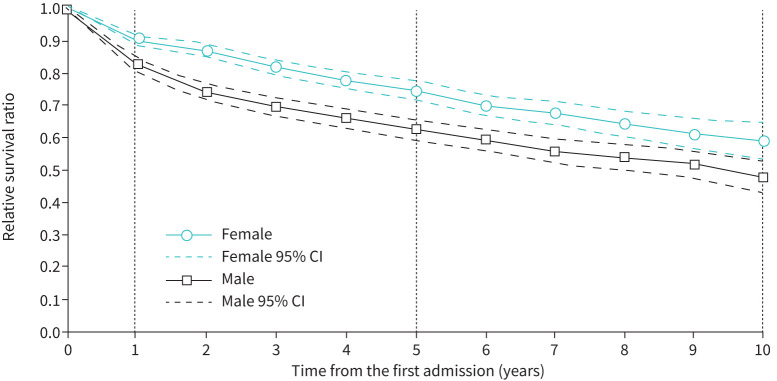

Relative survival and excess mortality

Of the 3934 incident hospitalised bronchiectasis patients from 2007 to 2017, 1628 (41.4%) had died by 31 December 2017. Relative survival of incident hospitalised bronchiectasis patients was lower than the expected survival of the Singapore population for both genders and all age-groups, except for females aged ≤18 years (supplementary figure S1). 1-, 5- and 10-year RSRs were 0.91 (95% CI 0.89–0.92), 0.75 (95% CI 0.72–0.78) and 0.59 (95% CI 0.54–0.65), respectively, for women, and 0.83 (95% CI 0.81–0.85), 0.63 (95% CI 0.59–0.66) and 0.48 (95% CI 0.43–0.53), respectively, for men, suggesting that female patients had better survival than male patients (figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative relative survival among incident hospitalised bronchiectasis patients in Singapore by sex and time from the first admission.

Excess mortality was seen especially in elderly males, and decreased with increasing number of years after a diagnosis of bronchiectasis. No difference in survival of patients first admitted in the recent period 2012–2016 compared to those admitted 2007–2011 was seen (excess mortality rate ratio 0.95, 95% CI 0.82–1.10) (table 2).

TABLE 2.

Excess mortality rate ratios

| Excess mortality rate ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Time since first admission, years | ||

| 1 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 2 | 0.53 (0.43–0.64) | <0.0001 |

| 3 | 0.46 (0.36–0.58) | <0.0001 |

| 4 | 0.37 (0.27–0.49) | <0.0001 |

| 5 | 0.34 (0.24–0.48) | <0.0001 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Male | 1.90 (1.63–2.22) | <0.0001 |

| Age of first admission, years | ||

| <18 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 18–39 | 1.44 (0.38–5.39) | 0.589 |

| 40–64 | 2.99 (0.95–9.43) | 0.006 |

| 65–74 | 4.52 (1.44–14.25) | 0.010 |

| ≥75 | 6.35 (2.02–19.96) | 0.002 |

| Year of first admission | ||

| 2007–2011 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 2012–2016 | 0.95 (0.82–1.10) | 0.499 |

Prevalence of ever-hospitalised bronchiectasis

3501 ever-hospitalised patients with bronchiectasis were alive as of 30 June 2017, giving a point prevalence of 88.3 per 100 000. There were more women (52.1%) than men, and the mean age was 71.2 years (table 3). When patients with bronchiectasis as a secondary diagnosis for any hospitalisation were included, the number of prevalent cases and point prevalence as of 30 June 2017 were 5835 and 147.1 per 100 000, respectively, with more men (51.5%) than women. The prevalence of patients with bronchiectasis as a hospital discharge diagnosis (whether primary or secondary) increases sharply with age, and was as high as 1738.6 per 100 000 and 1222.3 per 100 000 among men and women, respectively, aged ≥75 years (supplementary figure S2).

TABLE 3.

Prevalence and characteristics of surviving patients ever-hospitalised with bronchiectasis (as primary diagnosis versus all diagnoses of discharge), as of 30 June 2017

| Primary diagnosis | Prevalence, per 100 000 persons | Any diagnoses | Prevalence, per 100 000 persons | |

| Total | 3501 | 88.3 | 5835 | 147.1 |

| Sex, % | ||||

| Female | 52.1 | 90.2 | 48.5 | 140.0 |

| Male | 47.9 | 86.3 | 51.5 | 154.5 |

| Age group, % | ||||

| <18 years | 0.9 | 4.4 | 1.1 | 8.4 |

| 18–39 years | 2.5 | 7.2 | 2.7 | 12.8 |

| 40–64 years | 26.2 | 61.4 | 24.7 | 96.8 |

| 65–74 years | 24.9 | 269.0 | 24.1 | 434.1 |

| ≥75 years | 45.6 | 825.4 | 47.5 | 1433.0 |

| Ethnic group, % | ||||

| Chinese | 63.6 | 75.5 | 60.9 | 120.6 |

| Malay | 12.7 | 83.5 | 13.5 | 148.3 |

| Indian | 6.1 | 59.9 | 6.8 | 109.8 |

| Others | 17.6 | 481.2 | 18.8 | 858.5 |

| Age, years | 71.2±15.7 | 71.8±16.2 | ||

Data are presented as n or mean±sd unless otherwise stated. Due to rounding, percentages may not add up precisely to 100%.

Hospitalisation episodes for bronchiectasis

In 2017, there were a total of 1105 hospitalisation episodes with bronchiectasis as a primary diagnosis from 813 unique patients, with an average length of stay of 6.4 days per episode. Average length of stay was 1.7 days higher than hospitalised patients without bronchiectasis. Bronchiectasis hospitalisations accounted for 0.2% of total acute hospitalisations and 0.3% of total acute inpatient bed-days in 2017. These proportions were relatively stable throughout the study period (supplementary table S2).

Total inpatient costs and bills of bronchiectasis

Inpatient cost among patients with a discharge diagnosis of bronchiectasis were USD 5.3 million in 2017, an average increase of 7.0% per year, from USD 2.7 million in 2007 (supplementary table S2). There has been an average annual increase of 5.0% for inpatient cost per patient (USD 4032 in 2007 versus USD 6563 in 2017) and an increase of 6.6% for bill per patient (USD 1388 in 2007 versus USD 2634 in 2017).

Healthcare utilisation and total costs in the first year of follow-up

The total cost (both inpatient and outpatient) during the first year after an incident admission for bronchiectasis was USD 2.96 million in 2016 (n=404). The majority of the cost was for inpatient care (81.2%), followed by SOC (11.8%), emergency department (3.3%) and primary care (3.7%) attendance (table 4). The median number of visits at emergency departments, SOCs and primary care were one, four and one, respectively. However, patients at the 90th percentile had three emergency department visits, 13 SOC visits and 16 primary care visits. Likewise, total first-year cost varied widely: the average was USD 7331 among incident bronchiectasis patients in 2016, but with a standard deviation of USD 8863, and ∼10% had costs of more than USD 14 380. A unit increase in the number of comorbidities was significantly associated with a 7.6% increase in first-year total cost (95% CI 3.0–12.2%, p=0.001) after adjustment for gender and age at admission (results not shown).

TABLE 4.

Total first-year cost and healthcare utilisation incurred by incident hospitalised bronchiectasis patients admitted in 2016

| Total n (%) | Mean±sd | Median | 90th percentile | 95th percentile | |

| First-year costs, USD | |||||

| Number of bronchiectasis patients | 404 | ||||

| Hospitalisations (inclusive of the first admission) | 2 404 345 (81.2) | 5951±8799 | 3017 | 12 853 | 23 716 |

| ED visits | 96 785 (3.3) | 240±399 | 118 | 664 | 1058 |

| Specialist outpatient visits | 350 660 (11.8) | 868±922 | 589 | 1913 | 2502 |

| Primary care visits (polyclinics) | 70 140 (2.4) | 174±277 | 41 | 536 | 531 |

| Primary care visits (community health assistance scheme) | 39 723 (1.3) | 98±210 | 0 | 321 | 531 |

| Total | 2 961 654 (100.0) | 7331±8863 | 4479 | 14 381 | 25 024 |

| First-year utilisation | |||||

| Hospitalisations (inclusive of the first admission) | |||||

| Hospitalisations | 533 | 1.3±0.8 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Total length of stay, days | 3083 | 7.6±11.8 | 4 | 15 | 24 |

| ED visits | 515 | 1.3±2.0 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Specialist outpatient visits | 2383 | 5.9±6.3 | 4 | 13 | 17 |

| Primary care visits (polyclinics) | 1608 | 4.0±12.4 | 1 | 8 | 12 |

| Primary care visits (community health assistance scheme) | 978 | 2.4±5.1 | 0 | 8 | 12 |

ED: emergency department.

Total costs in 2017

Among prevalent and newly incident patients with bronchiectasis, the total direct medical costs were USD 9.55 million, amounting to 0.2% of all costs collected in the database in 2017. The majority of this cost was due to hospitalisation, representing 55.8% of direct medical costs, while primary care was 11.3%. The mean±sd cost per patient was USD 2476±6311. Median cost was USD 1014 and ∼10% had costs greater than USD 5414. Costs per patient were similarly greater in patients with higher numbers of comorbidities (supplementary table S3).

Discussion

The age-standardised incident hospitalisation for patients with bronchiectasis declined in Singapore during the 10-year period from 2007 to 2017. The potential explanations are the advancement in treatment and imaging could have reduced the need for hospitalisation [22, 23]. In Singapore, dedicated bronchiectasis clinics have been set up in most hospitals and doctors have better understanding on the management of bronchiectasis. Furthermore, there have been easy accessibility on investigations such as computed tomography of the thorax, allowing early diagnosis of the disease. In addition, home intravenous antibiotics services have been available in most of the hospitals. Secondly, improvement of outpatient services such as using a multidisciplinary approach in management could also have contributed to the reduction [24]. Lastly, improved accessibility to information such as international guidelines for diagnosis and treatment may have led to more appropriate and timely treatment for patients.

The average annual rate of age-standardised hospitalisation in Singapore was 30.4 per 100 000 population between 2007 and 2017. This is higher than published data from other countries, which range from 1.8 to 25.7 per 100 000 [25, 26]. A study conducted in Hong Kong reported a hospitalisation rate of 21.9 per 100 000 [26]. In this study, the rate of hospitalisation with bronchiectasis increased with age and were higher in older women. Our study also demonstrates that incidence rates of hospitalisation-requiring bronchiectasis in women are starting to exceed those in men.

Survival for patients with bronchiectasis requiring hospitalisation is considerably lower than that expected for the general Singapore population. Recent studies have shown that frequency of exacerbations, and in particularly three or more exacerbations per year, was associated with an increased risk of mortality among bronchiectasis patients [27, 28]. However, this could not be tested in our study as data on exacerbations are not available. Using bronchiectasis hospitalisations as a crude proxy for exacerbations, 5% of incident hospitalisations in 2016 had at least three bronchiectasis hospitalisations during the first year of admission, and the proportion hovered between 4% and 8% in the years 2007–2016.

The prevalence of ever-hospitalised bronchiectasis patients was estimated at 147.1 per 100 000 in 2017 in Singapore, with a prevalence of 1.4% in the population aged ≥75 years. International studies have reported much higher prevalence, especially in studies that were able to identify patients in primary care. For example, a study in Spain reported prevalence rates in Catalonia of 362 per 100 000 in a primary care database [29]. A study of the primary care database in the United Kingdom reported a prevalence of 379 per 100 000 in women and 281 per 100 000 in men in 2012 [30]. However, there is substantial variation in prevalence estimates. A German population-based study conducted in 2005–2011 suggested a prevalence of only 67 per 100 000 [5], while another study estimated a prevalence in the USA of 139 per 100 000 [4]. The prevalence estimates obtained in our study are best viewed as “floor estimates”, as we were unable to include patients with mild bronchiectasis who did not require hospitalisation during the 10-year period of study.

Of interest is the decline of TB as a secondary diagnosis among incident hospitalised bronchiectasis patients, which we see throughout the period of 2007–217. Bronchiectasis is a well-known sequela of TB. The incidence of TB was very high in Singapore in the 1960s, but declined to a nadir of 35 per 100 000 in 2007, and there has since been a plateau in the incidence [31]. Patients with incident TB were more likely to be male and older [32]. This long-term secular decline in TB may partly explain the reduction in TB as a secondary diagnosis over the 10-year period, and may also explain the sharper decline in incidence of bronchiectasis in men compared to women over the same period.

Our study estimated that the annual direct medical cost associated with bronchiectasis was USD 9.6 million in 2017. The mean total annual cost for patients with COPD has been estimated at USD 9.9 million between 2005 and 2009 [33]. Methodological differences between studies prevent direct comparisons of these costs.

The average annual cost was USD 7331 per patient, with a substantial variation in cost in 2017. 10% of patients admitted in 2016 had first-year costs above USD 14 380, a significant amount in Singapore where the median monthly household income from work is about USD 6508 in 2016 [34]. Our study shows that comorbidities was an important driver of costs in bronchiectasis.

Recent research has highlighted the significant cost burden of bronchiectasis. Weycker et al. [9] reported an incremental cost of USD 5681 in bronchiectasis patients compared to matched controls (1999–2001) and 56% of the incremental cost was attributed to inpatient admissions. Another study in the USA reported an increase of USD 2319 for bronchiectasis patients compared to controls [35]. A recent German study using statutory health insurance data reported that total direct expenditure per bronchiectasis patient was EUR 18 634, and 31% higher than matched controls. Of note, hospitalisation costs and antibiotics expenditures were substantially higher in bronchiectasis patients [10].

A key advantage of our study is the use of a comprehensive nationwide dataset giving unbiased estimates for incidence, prevalence, survival and costs. Some limitations were that patients with bronchiectasis who were not hospitalised were not included. We relied on administrative data to identify patients with bronchiectasis, and errors in coding could cause misclassification. Not all expenditures were included; we used norm costs to estimate public sector specialist outpatient costs, and we did not have costs associated with most private sector primary and specialist outpatient care encounters, nor nursing home and other long-term care and palliative care costs, medication and medical device costs that were not linked to a hospital admission.

In summary, we find that bronchiectasis is common and imposes a substantial burden on healthcare costs and survival of patients in Singapore.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00334-2021.SUPPLEMENT (295.7KB, pdf)

Footnotes

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Editorial comment in ERJ Open Res 2021; 7: 00507-2021 [https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00507-2021].

This article has supplementary material available from openres.ersjournals.com

Conflict of interest: H.P. Phua has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: W-Y. Lim has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: G. Ganesan has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J. Yoong has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: K.B. Tan has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J.A. Abisheganaden has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A.Y.H. Lim has nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Redondo M, Keyt H, Dhar R, et al. Global impact of bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis. Breathe 2016; 12: 222–235. doi: 10.1183/20734735.007516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seitz AE, Olivier KN, Steiner CA, et al. Trends and burden of bronchiectasis-associated hospitalizations in the United States, 1993–2006. Chest 2010; 138: 944–949. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford ES. Hospital discharges, readmissions, and ED visits for COPD or bronchiectasis among US adults: findings from the nationwide inpatient sample 2001–2012 and Nationwide Emergency Department Sample 2006–2011. Chest 2015; 147: 989–998. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weycker D, Hansen GL, Seifer FD. Prevalence and incidence of noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis among US adults in 2013. Chron Respir Dis 2017; 14: 377–384. doi: 10.1177/1479972317709649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ringshausen FC, de Roux A, Pletz MW, et al. Bronchiectasis-associated hospitalizations in Germany, 2005–2011: a population-based study of disease burden and trends. PLoS One 2013; 8: e71109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang B, Choi H, Lim JH, et al. The disease burden of bronchiectasis in comparison with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a national database study in Korea. Ann Transl Med 2019; 7: 770. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.11.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palwatwichai A, Chaoprasong C, Vattanathum A, et al. Clinical, laboratory findings and microbiologic characterization of bronchiectasis in Thai patients. Respirology 2002; 7: 63–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2002.00367.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhar R, Singh S, Talwar D, et al. Bronchiectasis in India: results from the European Multicentre Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration (EMBARC) and Respiratory Research Network of India Registry. Lancet Glob Health 2019; 7: e1269–e1279. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30327-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Oster G, et al. Prevalence and economic burden of bronchiectasis. Clin Pulm Med 2005; 12: 205–209. doi: 10.1097/01.cpm.0000171422.98696.ed [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diel R, Chalmers JD, Rabe KF, et al. Economic burden of bronchiectasis in Germany. Eur Respir J 2019; 53: 1802033. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02033-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministry of Health Singapore . Population and Vital Statistics. www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/singapore-health-facts/population-and-vital-statistics Date last accessed: 10 March 2021.

- 12.Ministry of Health Singapore . Disease Burden: Distribution of Disability-Adjusted Life Years by Broad Cause Group 2019. www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/singapore-health-facts/disease-burden Date last accessed: 10 March 2021.

- 13.Ministry of Health Singapore . Singapore's Healthcare System. www.moh.gov.sg/home/our-healthcare-system Date last accessed: 10 March 2021.

- 14.Ministry of Health Singapore . Subsidies for Services and Drugs at Public Healthcare Settings. www.moh.gov.sg/cost-financing/healthcare-schemes-subsidies/subsidies-for-services-and-drugs-at-public-healthcare-settings Date last accessed: 6 July 2021.

- 15.Ministry of Health Singapore . Community Health Assist Scheme. www.moh.gov.sg/cost-financing/healthcare-schemes-subsidies/community-health-assist-scheme. Date last accessed: 6 July 2021.

- 16.Department of Statistics Singapore . Population Trends, 2019 – Non-Geospatial Data: Time Series Data for Tables/Charts. www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/population/population-trends Date last accessed: 3 March 2020.

- 17.Dickman PW, Coviello E. Estimating and modeling relative survival. STATA J 2015; 15: 186–215. doi: 10.1177/1536867X1501500112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ederer F, Heise H. Instructions to IBM 650 Programmers in Processing Survival Computations. Methodological Note No. 10, End Results Evaluation Section. Bethesda, MD, National Cancer Institute, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Statistics Singapore . Complete Life Tables for Singapore Resident Population, 2017–2018: Life Tables and Life Expectancy Calculator from 2003. 2018. www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/population/complete-life-table Date last accessed: 3 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ministry of Trade and Industry – Department of Statistics . Consumer Price Index, Base Year 2014=100, Annual, 1961–2019. https://storage.data.gov.sg/consumer-price-index-annual/resources/consumer-price-index-base-year-2014-100-annual-2020-02-23T17-36-08Z.csv Date last accessed: 3 March 2020.

- 21.Monetary Authority of Singapore . Statistics, Exchange Rates. MAS, 2019. https://eservices.mas.gov.sg/Statistics/msb/ExchangeRates.aspx Date last accessed: 18 May 2020.

- 22.Chalmers JD, Aliberti S, Blasi F. Management of bronchiectasis in adults. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 1446–1462. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00119114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasteur MC, Bilton D, Hill AT, et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for non-CF bronchiectasis. Thorax 2010; 65: Suppl. 1, i1–i58. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.136119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan J, Ho S, Lee JYH, et al. Clinical outcomes in relation to care of a multidisciplinary non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis out-patient clinic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 201: A6278. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goeminne PC, Hernandez F, Diel R, et al. The economic burden of bronchiectasis – known and unknown: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med 2019; 19: 54. doi: 10.1186/s12890-019-0818-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan-Yeung M, Lai CKW, Chan K-S, et al. The burden of lung disease in Hong Kong: a report from the Hong Kong Thoracic Society. Respirology 2008; 13: Suppl. 4, S133–S165. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01394.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez-Garcia MÁ, Athanazio R, Gramblicka G, et al. Prognostic value of frequent exacerbations in bronchiectasis: the relationship with disease severity. Arch Bronconeumol 2019; 55: 81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chalmers JD, Aliberti S, Filonenko A, et al. Characterization of the ‘frequent exacerbator phenotype’ in bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 197: 1410–1420. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201711-2202OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monteagudo M, Rodríguez-Blanco T, Barrecheguren M, et al. Prevalence and incidence of bronchiectasis in Catalonia, Spain: a population-based study. Respir Med 2016; 121: 26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snell N, Gibson J, Jarrold I, et al. Epidemiology of bronchiectasis in the UK: findings from the British Lung Foundation's ‘Respiratory Health of the Nation’ project. Respir Med 2019; 158: 21–23. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wah W, Das S, Earnest A, et al. Time series analysis of demographic and temporal trends of tuberculosis in Singapore. BMC Public Health 2014; 14: 1121. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ministry of Health Singapore . Update on Tuberculosis Situation in Singapore. www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/update-on-tuberculosis-situation-in-singapore Date last accessed: 10 March 2021. Date last updated: 24 March 2019.

- 33.Teo WSK, Tan W-S, Chong W-F, et al. Economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respirology 2012; 17: 120–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02073.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Department of Statistics Singapore . Key Household Income Trends, 2016. www.singstat.gov.sg/-/media/files/publications/households/pp-s23.pdf Date last accessed: 17 March 2021.

- 35.Joish VN, Spilsbury-Cantalupo M, Operschall E, et al. Economic burden of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis in the first year after diagnosis from a US health plan perspective. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2013; 11: 299–304. doi: 10.1007/s40258-013-0027-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00334-2021.SUPPLEMENT (295.7KB, pdf)