Abstract

Eukaryotic genomes contain potentially unstable sequences whose rearrangement threatens genome structure and function. Here we show that certain mutant alleles of the nucleotide excision repair (NER)/TFIIH helicase genes RAD3 and SSL2 (RAD25) confer synthetic lethality and destabilize the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome by increasing both short-sequence recombination and Ty1 retrotransposition. The rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutations do not markedly alter Ty1 RNA or protein levels or target site specificity. However, these mutations cause an increase in the physical stability of broken DNA molecules and unincorporated Ty1 cDNA, which leads to higher levels of short-sequence recombination and Ty1 retrotransposition. Our results link components of the core NER/TFIIH complex with genome stability, homologous recombination, and host defense against Ty1 retrotransposition via a mechanism that involves DNA degradation.

Genome instability can result from DNA alterations caused by the environment, normal metabolism, or mobile genetic element activity. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, homologous recombination is an important mechanism for repairing DNA damage (27). However, recombination between dispersed, repetitive sequences can result in deleterious genome rearrangements (55). The requirement of a high degree of DNA homology for recombination to occur is one mechanism by which these rearrangements are minimized in yeast (55). This mechanism is under the control of mismatch repair and mutation avoidance genes in yeast (38, 53). Another way to reduce genome rearrangements is to selectively restrict recombination between short repeats, which are abundant in eukaryotic genomes (12). In yeast repeats of fewer than 250 to 300 bp recombine less well per unit length than do longer sequences (3, 35) while sequences that have less than 30 bp of homology are unable to undergo homologous recombination (43). Little is known about the genes and pathways that prevent recombination between short, 30- to 300-bp sequences, which is referred to as short-sequence recombination (SSR). However, increased SSR in rad3-G595R and SSL1-T242I mutants is linked to a defect in exonucleolytic processing of broken DNA molecules (2, 3, 42).

Ty1 elements belong to a widely disseminated class of mobile genetic elements called long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons that are structurally and functionally related to retroviruses (9, 16, 28). The transpositional replication of Ty1 elements is very similar to that of retroviruses; however, Ty1 is not infectious. Ty1 elements are transcribed from LTR to LTR to form a genome-length transcript that is used as a template for reverse transcription and translation. Ty1 elements contain two partially overlapping genes: TYA1 (gag), which encodes the structural proteins of the virus-like particle (VLP), and TYB1 (pol), which encodes the protease, integrase (IN), and reverse transcriptase (RT). Linear Ty1 cDNA is synthesized by reverse transcription within VLPs located in the cytoplasm. A preintegration complex containing at least IN and Ty1 cDNA must transit the nuclear membrane to access a genomic target (37, 46). Ty1 IN catalyzes the integration of this cDNA into new genomic sites. Ty1 cDNA can also recombine with endogenous elements (44), especially when IN-mediated integration is blocked (61). However, cDNA recombination requires the recombination and repair gene RAD52, whereas transpositional integration does not.

Minimizing the level of Ty1 retrotransposition is particularly important for maintaining genome stability because these elements are competent for transposition and their RNA transcripts accumulate to an exceptionally high level (9, 16, 28). Ty1 element insertion can mutate essentially any yeast gene and can also initiate genome rearrangements by homologous recombination. However, mature Ty1 proteins and VLPs are present at low levels, and the rate of Ty1 transposition is 10−5 to 10−7 per element per cell division. Several steps in the process of Ty1 retrotransposition are modulated by host genes, including those required for transcription of the element (75), programmed +1 frameshifting to express TYB1 (25), protein stability and VLP maturation (14), and target site specificity (6, 19). Recently, the accumulation of unincorporated Ty1 cDNA has been identified as a key stage of retrotransposition that is inhibited by several genes involved in DNA repair and recombination (40, 57).

Rad3 and Ssl2 (Rad25) are DNA helicases with opposite polarities; Rad3 has 5′-3′ helicase activity, and Ssl2 has 3′-5′ activity (31, 66, 67). Both proteins are components of the conserved core of the nucleotide excision repair (NER) and RNA polymerase II transcription initiation factor TFIIH complexes (21, 52). Mutations in the human homologs of RAD3 and SSL2 (XPD and XPB, respectively) can cause the diseases xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), Cockayne's syndrome, and trichothiodystrophy (TTD), which feature impaired DNA repair and transcription and genome instability (11). The specificity of the core NER/TFIIH complex is determined by additional components of S. cerevisiae, such as Cc11 and Kin28 or Rad1, Rad2, Rad4, Rad10, and Rad14, which are required for transcription or NER, respectively (32, 66, 69). Many rad3 and ssl2 mutations confer a broad array of phenotypes, including temperature-sensitive (TS) growth (3, 29, 31, 40, 48, 56), UV sensitivity (29, 54, 58, 64, 73), elevated mutation and recombination rates (45, 64), and translational suppression (29). The existence of alleles that confer some but not other phenotypes suggests that RAD3 and SSL2 have multiple functions. However, the functional relatedness of RAD3 and SSL2 has not been defined.

We previously isolated rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutants by using markedly different experimental rationales. The rad3-G595R mutant was isolated on the basis of its elevated level of SSR (3). Interestingly, physical studies indicate that degradation of both the 5′ and 3′ strands of a broken DNA molecule is slower in this mutant. ssl2-rtt, which increases the level of global Ty1 transposition (40), was isolated by using an element tagged with the his3-AI retrotransposition indicator gene (18). The ssl2-rtt mutation does not alter Ty1 expression or target site preferences. Cells containing rad3-G595R or ssl2-rtt are TS and weakly UV sensitive and have normal levels of mitotic recombination (40, 42). Ty1 cDNA recombination also appears to be unaffected by the ssl2-rtt mutation. Most importantly, the level of Ty1 cDNA increases in the ssl2-rtt mutant; this is strikingly similar to the increased stability of broken DNA observed with rad3-G595R. In addition, certain rad3 mutations increase Ty1 transposition. Here, we connect SSR and Ty1 retrotransposition by showing that the TFIIH subunit mutations rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt stimulate both processes through similar mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetic techniques, media, and strains.

Yeast genetic techniques and media were used as described by Sherman et al. (62) and by Guthrie and Fink (30). Strains in this study were derived from JC297 (MATα ura3-167 his3-Δ200 trp1-hisG Ty1-270his3-AI Ty-588neo Ty-146[tyb::lacZ]) (14), GRF167 (MATα his3-Δ200 ura3-167) (8), and W303-1A (MATa can1 leu2-3,112 his3-11,15 trp1-1 ura3-1 ade2-1) (71). BLY154 and BLY157 are isogenic rad3-G595R derivatives of the RAD3 strains JC297 and GRF167, respectively, and were constructed by two-step gene transplacement using pLAY182 (3). DG1869 (MATa::URA3 ade2-101 his3-Δ200 ura3-167 ssl2-rtt Ty1-270his3-AI Ty-588neo Ty-146[tyb::lacZ]) is a closely related derivative of JC358 that contains ssl2-rtt (14, 40). BLY200 and BLY202 were constructed by disrupting the RAD52 gene in strains JC297 and BLY154, respectively, with a 5.5-kb PvuII fragment from plasmid pBDG542, using the universal gene blaster technique of Alani et al. (1). Successful rad52 disruptions were identified by increased sensitivity of organisms to 0.025% methyl methanesulfonate and verified by Southern analysis. Strains DG789 and DG1741 were described previously (18, 40). The isogenic W303-1A derivatives W961-5A (MATa ade2-1 can1-100 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1), ABX81-6A (MATa ade2-1 can1-100 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 rad3-G595R), ABT151 (MAT::LEU2 ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 [pLAY97, pGHOT]), and ABT152 (MAT::LEU2 ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 rad3-G595R [pLAY97, pGHOT]) were described previously (42). Strains ABX267-18C (MATa ade2-1 can1-100 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 ssl2-rtt) and DG1730 were derived from W961-5A and JC297, respectively, by a two-step gene transplacement using plasmid pBDG824 (40). Additional crosses between ABX267-18C and isogenic strains and transformation with plasmids pLAY97 (49) and pGHOT (51) gave rise to strain ABT261 (MAT::LEU2 ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 ssl2-rtt [pLAY97, pGHOT]).

Plasmids.

Plasmids were constructed by standard procedures (60). Vectors pRS406, pRS414, and pRS416 were provided by R. Sikorski (63), and pGHOT (51) was provided by J. Nickoloff and F. Heffron. Plasmid pGTy1-H3his3-AI was described by Curcio and Garfinkel (18); pCL58, pBDG202, pBDG824, and pOY1 were described by Lee et al. (40); pLAY182 was described by Bailis et al. (3); and pLAY97 and pLAY144 were described by Bailis and Maines (2) and Negritto et al. (49). Plasmid pBL4 was constructed by subcloning a 3,592-bp SalI-KpnI fragment containing RAD3 from p1772 (provided by T. Donahue) into the URA3-based centromere plasmid pRS416. Plasmid pBDG542 was constructed by subcloning the URA3::hisG universal gene blaster fragment (1) into a BglII site present in the RAD52 coding sequence present on pUC12-RAD52 (provided by D. Schild). pTy1made2-AI contains a complete Ty1 element tagged with the retrotransposition indicator gene ade2-AI (20) that is present on a URA3-based 2μ shuttle vector and was provided by M. J. Curcio.

DNA fragment insertion.

The plasmid pLAY144 (2), containing the HIS3 gene on a 1.3-kb genomic fragment disrupted by the insertion of a 1.2-kb fragment containing the URA3 gene, was digested with restriction endonucleases to generate DNA fragments with various lengths of HIS3 sequences flanking URA3. The lengths of the HIS3 flanking sequences were 445 bp (182 bp of 5′ flanking sequence plus 263 bp of 3′ flanking sequence), 254 bp (79 bp of 5′ flanking sequence plus 175 bp of 3′ flanking sequence), or 127 bp (91 bp of 5′ flanking sequence plus 36 bp of 3′ flanking sequence). Gel-purified fragments were introduced into strains W961-5A (wild type), ABX81-6A (rad3-G595R), and ABX267-18C (ssl2-rtt) by electroporation. After 5 to 7 days of incubation at 30°C, Ura+ colonies were counted and screened for the ability to grow without histidine to determine whether the DNA fragments had integrated into and disrupted the HIS3 locus (Ura+ His−) or gene converted the ura3-1 marker at the URA3 locus (Ura+ His+). Southern analysis of over 100 Ura+ recombinants showed that the DNA fragments either integrated at HIS3 or converted the ura3-1 marker at the URA3 locus (A. M. Bailis, unpublished results). The percentage of insertion of the DNA fragment into the HIS3 locus, versus gene conversion at the URA3 locus, was determined by dividing the number of His− transformants by the total number of His+ and His− transformants. Because the Ura+ transformants are all the result of either DNA fragment insertion at the HIS3 locus or insertion or gene conversion at the URA3 locus, each transformant was treated as the result of a single trial. Statistical differences between insertion percentages were assessed by performing contingency chi-square analysis on the numbers of Ura+ His+ and Ura+ His− transformants obtained with a given DNA fragment. The mean efficiency of transformation with each fragment, normalized against the efficiency of transformation with an intact centromere plasmid (pRS414), for a minimum of five trials was determined for each strain (L. Bi and A. M. Bailis, unpublished results). We chose not to use these numbers for comparisons because the plating efficiencies varied significantly from trial to trial, which could lead to large variations in the apparent transformation efficiencies. This variability prevented us from making determinations of statistical significance between strains. Insertion percentages, however, were highly reproducible and differed by less than 1% between trials (L. Bi and A. M. Bailis, unpublished results).

Stability of HO endonuclease-digested plasmid.

Stationary-phase cultures grown from single colonies of strains ABT151 (wild type), ABT152 (rad3-G595R), and ABT261 (ssl2-rtt) were used to inoculate 500-ml volumes of synthetic complete (SC) medium lacking uracil and tryptophan (SC − Ura − Trp containing 3% glycerol and 3% lactate), which selected for the plasmids pLAY97 and pGHOT and neither induced nor repressed the galactose-inducible GAL::HO fusion gene on pGHOT. Cultures were grown to a density of 5 × 106 cells/ml at 30°C before a 50-ml aliquot was removed and the cells therein were pelleted and then frozen at −80°C. Fifty milliliters of a 20% galactose solution was then added to the culture to induce HO expression, which resulted in cutting of a unique HO recognition site on pLAY97. After a 30-min incubation at 30°C, cells were counted and another aliquot was removed and processed as described above. The remaining cells were filtered through sterile 0.4-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose filters and resuspended in fresh, prewarmed SC − Trp medium containing 2% glucose. Uracil was provided because pLAY97 is cleaved in more than 50% of the cells exposed to galactose and fewer than 1% of the broken plasmids rejoin (2). Glucose was provided to repress GAL::HO gene expression. HO endonuclease activity is essentially absent 30 min after GAL::HO gene expression is repressed (50). Cells were counted and aliquots were removed and processed at regular intervals as described above. Total DNA prepared from the frozen pellets was digested with NcoI and analyzed by Southern hybridization with a 32P-labeled Bluescript plasmid, which is the backbone of pLAY97. The hybridization patterns were visualized and quantitated by phosphorimaging (Molecular Dynamics). The stability of HO-digested DNA was determined by comparing the levels of the 1.3- and 3.4-kb NcoI- and HO-digested fragments with that of the NcoI-digested 4.7-kb fragment. Signals were not heavily influenced by the outgrowth of cells in which pLAY97 remained undigested because all cells required at least 4 h to double in density (3; A. M. Bailis, unpublished results) while the broken-plasmid signal was reduced at least fourfold (see Results). Note that while the levels of HO digestion differed by as much as threefold, the half-lives of the broken plasmids were more consistent, differing by less than 22%. Decay of HO-digested DNA was plotted as the log of the percentage of HO-digested DNA remaining versus time. The half-lives of the HO-digested DNA fragments were the means of three separate determinations ± standard deviations. Lines were generated by least-squares analysis.

Ty1 transposition.

Qualitative and quantitative estimates of spontaneous Ty1his3-AI transposition were determined as described previously (18, 40). The rate of occurrence of spontaneous Ty1-induced mutations at the CAN1 locus was determined as described by Lee et al. (40). The positions of Ty1 insertions at CAN1 were determined by PCR analysis as described by Rinckel and Garfinkel (59). Detection of spontaneous Ty1 transposition events upstream of glycine tRNA genes was performed essentially as described previously (40), except that hot start PCR (Perkin-Elmer) was used to amplify the insertions and Southern analysis with a 32P-labeled Ty1 LTR probe was used to detect the transposition events. Statistical significance was determined by chi-square analysis.

Northern blot analysis.

Yeast strains were grown at 20°C in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium to mid- to late log phase. Total RNA was isolated, separated on a 1% agarose gel, and blotted to a nitrocellulose filter (Schleicher & Schuell) as described by Lee and Culbertson (39). DNA probes were made by randomly primed DNA synthesis (Pharmacia) or 5′-end labeling by the use of T4 polynucleotide kinase (United States Biochemical). A 3.6-kb PvuII fragment from pOY1 was used to make the Ty1 probe. The Ty1-270his3-AI probe was made from a 0.5-kb PstI fragment containing his3-AI sequences from pOY1. Isoleucine pre-tRNA and tryptophan pre-tRNA probes were prepared by 5′-end labeling of their respective 45- and 32-nucleotide introns as described previously (56). Both pre-tRNA hybridization probes were hybridized with the same filter after the Ty1 probes were removed. Hybridization and washing conditions were as described by Lee and Culbertson (39), and hybridization signals were quantitated by phosphorimaging.

Western analysis.

Total-protein extracts were prepared from cells grown to mid- to late log phase at 20°C, and Western analysis was performed as described by Lee et al. (40). Immunodetection was performed by the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) technique as described by the supplier (Amersham). ECL signals were quantitated by laser densitometry (Pharmacia-LKB).

Detection and stability of Ty1 cDNA.

Detection of unincorporated Ty1 cDNA was performed as described by Lee et al. (40). To determine the stability of Ty1 cDNA, yeast strains were inoculated into 80 ml of YPD broth and grown to mid- to late log phase at 20°C. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in 80 ml of fresh YPD broth. Phosphonoformic acid (PFA [Foscarnate; Sigma Chemical Co.]) was added to the cultures at a final concentration (200 μg/ml) that almost completely inhibited Ty1 transposition but did not affect cell growth (B.-S. Lee and D. J. Garfinkel, unpublished results). Ten milliliters of cell culture was immediately pelleted and stored at −80°C. Ten-milliliter aliquots were removed from the remaining cultures after 30, 60, 120, 240, and 360 min of incubation in YPD at 20°C. Aliquots removed at each time point were quickly pelleted and stored at −80°C. Total DNA was extracted from each cell pellet, digested with PvuII, and analyzed by Southern hybridization followed by phosphorimaging as described previously (40). Decay of Ty1 cDNA was plotted as the log of the percentage of Ty1 cDNA remaining relative to the level of Ty1 cDNA at time zero versus time. The half-lives of Ty1 cDNA were similar in two separate Southern analyses. Lines were generated by least-squares fit analysis.

RESULTS

rad3-G595R and ssl2(rad25)-rtt mutations are synthetically lethal.

Because of the phenotypic similarities between rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutants and the complex genetic interactions observed with TFIIH subunit mutants, we determined the phenotype of a rad3-G595R ssl2-rtt double mutant. These mutations cause TS growth at 37°C and are unlinked; therefore, we attempted to construct the double mutant by crossing strains BLY154 (rad3-G595R) and DG1869 (ssl2-rtt) followed by tetrad analysis. The segregation pattern of the TS phenotype clearly suggests that the rad3-G595R ssl2-rtt double mutant is nonviable. In 66 tetrads, 49 segregated at 1 nonviable:2 TS:1 non-TS spores (tetratype), 8 segregated at 2 nonviable:2 non-TS spores (nonparental ditype), and 9 segregated 4 TS:0 non-TS spores (parental ditype). Representative tetratype, nonparental ditype, and parental ditype tetrads were allele tested by complementation with rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt tester strains to verify their genotypes. In no case did we recover a rad3-G595R ssl2-rtt double mutant. The synthetic lethality of rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutations was also allele specific, as demonstrated by the normal segregation of the highly UV-sensitive rad25-799am and rad3-2 mutations (B.-S. Lee and D. J. Garfinkel, unpublished results). These results suggest that RAD3 and SSL2 may have overlapping functions in the cell.

The ssl2-rtt mutation increases SSR.

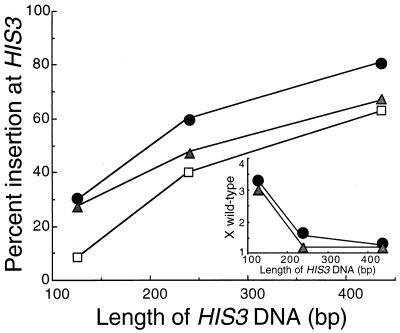

We compared the levels of insertion of linear DNA fragments containing the URA3 gene flanked by different amounts of HIS3 sequence in isogenic wild-type (W961-5A), rad3-G595R (ABX81-6A), and ssl2-rtt (ABX267-18C) mutants cells containing the ura3-1 allele and the wild-type HIS3 gene (Fig. 1). Targeted homologous recombination of the linear fragment at the HIS3 locus results in Ura+ His− cells, whereas gene conversion of the ura3-1 allele results in Ura+ His+ cells. This assay was chosen because it is topologically similar to retrotransposition in that it involves an interaction between the ends of a physically discrete DNA molecule and a genomic target. The ssl2-rtt and rad3-G595R mutations increased SSR to equivalent levels (P = 0.64) when the inserting DNA fragment contained 127 bp of sequence homologous to HIS3. However, ssl2-rtt caused an intermediate level of insertion with a fragment that had 254 bp of HIS3 homology (P = 0.0001) and did not increase the level of insertion with a fragment that had 445 bp of HIS homology (P = 0.0001).

FIG. 1.

DNA fragment insertion into the genomes of wild-type and rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutant cells. DNA fragments with different lengths of HIS3 sequence flanking the URA3 gene were obtained by endonuclease digestion of pLAY144 (2, 42) and used to transform His+ Ura− wild-type (W961-5A) (open squares), rad3-G595R (ABX81-6A) (closed circles), and ssl2-rtt (ABX267-18C) (cross-hatched triangles) yeast cells by electroporation. Ura+ transformants were counted and then tested for the ability to grow in the absence of histidine to determine whether the DNA fragments had inserted into the HIS3 locus (Ura+ His−) or gene converted the ura3-1 marker at the URA3 locus (Ura+ His+). Insertion into the HIS3 locus was determined by dividing the number of His− transformants by the total number of Ura+ transformants. (Inset) Fold differences (X-fold; wild-type) between percentages of integration events at the HIS3 locus in wild-type, rad3-G595R, and ssl2-rtt mutants versus length of HIS3 homology.

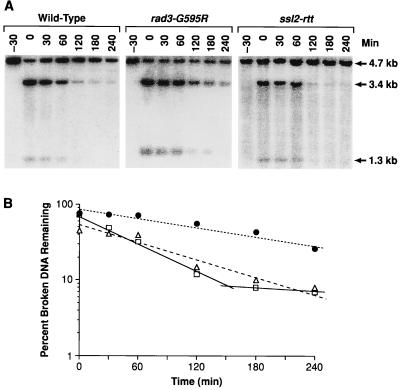

The ssl2-rtt mutation increases the stability of broken DNA molecules.

The rad3-G595R allele confers a marked increase in the stability of DNA molecules that have been broken in vivo by digestion with the HO endonuclease (2, 3, 42). This assay is a reliable indicator of the capacity of the cell to repair genomic double-strand breaks and to rescue naked DNA fragments by SSR (2, 3, 42). Therefore, we determined whether ssl2-rtt affected the stability of broken DNA molecules by measuring the decay rates of a single-copy plasmid digested by HO in isogenic wild-type (ABT151), rad3-G595R (ABT152), and ssl2-rtt (ABT261) strains (Fig. 2A). As observed for the rad3-G595R mutant, the abundance of HO-digested plasmid DNA changed little in the ssl2-rtt mutant during the 60 min that followed HO expression, while a significant loss of DNA was observed in the wild-type strain during the 30 min that followed HO expression. PhosphorImager analysis (Fig. 2B) revealed that ssl2-rtt cells had a half-life for broken DNA (85 ± 6 min) that was intermediate between those of the wild type (46 ± 2 min) and the rad3-G595R mutant (160 ± 30 min), which is in agreement with the levels of SSR in these cells.

FIG. 2.

Stability of a single-copy plasmid linearized in vivo by the HO endonuclease. (A) Southern analysis of plasmid DNA linearized in vivo. DNA was prepared from wild-type (ABT151), rad3-G595R (ABT152), and ssl2-rtt (ABT261) yeast strains containing the plasmids pLAY97 and pGHOT either before a 30-min induction of HO endonuclease expression (−30 min) or after HO endonuclease expression was shut off (0 to 240 min). The fragments of pLAY97 digested by NcoI endonuclease digestion (4.7 kb) and by NcoI and HO endonuclease digestion (3.4- and 1.3-kb fragments) are described in the text. The stability of the HO-cleaved plasmid DNA over time was indicated by changes in the intensity of the 3.4- and 1.3-kb fragments relative to that of the 4.7-kb fragment, as shown by Southern analysis using a 32P-labeled plasmid backbone probe. The shading that appears in some lanes of the photograph is an artifact of the phosphorimage reproduction process and does not reflect the level of hybridized probe, which is not significantly above background. (B) Decay of linearized plasmid DNA. The kinetics of the loss of pLAY97 sequences from isogenic wild-type (open squares, solid line), rad3-G595R (closed circles, dotted line), and ssl2-rtt (gray triangles, dashed line) strains over time was determined by dividing the sum of the 3.4- and 1.3-kb fragment signals by the sum of the 3.4-, 1.3, and 4.7-kb fragment signals, as determined by phosphorimaging. The resulting values were plotted as the log of the percentage of HO-digested DNA (broken DNA) remaining versus time.

The rad3-G595R mutation increases Ty1 retrotransposition.

To detect spontaneous Ty1 transposition events (Table 1), we monitored the rate of formation of His+ colonies by using a chromosomal Ty1 element marked with the his3-AI retrotransposition indicator gene in isogenic wild-type (JC297), rad3-G595R (BLY154), rad3-G595R rad52-hisG (BLY202), rad52-hisG (BLY200), and ssl2-rtt (DG1730) strains. Like ssl2-rtt, the rad3-G595R mutation markedly increased the rate of formation of Ty1his3-AI-mediated His+ colonies. Next we determined whether rad3-G595R stimulated both Ty1 cDNA recombination and transposition or just Ty1 transposition by monitoring Ty1his3-AI movement in a rad3-G595R rad52-hisG double mutant. The His+ colony formation rate increased 62-fold in the rad3-G595R rad52-hisG double mutant and was slightly less than the rate in the rad3-G595R single mutant (P = 0.05). These results suggest that rad3-G595R increases Ty1 retrotransposition and also causes a modest increase in cDNA recombination. As was observed in previous studies (15, 40, 57), Ty1 transposition increased in a rad52 null mutant. We also compared the rate of Ty1his3-AI transposition in isogenic wild-type (JC297), rad3-G595R (BLY154), and ssl2-rtt (DG1730) strains in a separate experiment to determine whether these mutations affected Ty1 transposition differently. Interestingly, the rad3-G595R mutation stimulated the rate of His+ colony formation about threefold more than did ssl2-rtt, a result in accord with their effects on the stability of broken DNA molecules.

TABLE 1.

Transposition of Ty1his3-AI elements

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Transposition ratea (106) | Fold increase in transposition (mutant/wild type)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| JC297 | RAD3 RAD52 | 0.04 | 1 |

| BLY200 | RAD3 rad52-hisG | 0.62 | 16 |

| BLY154 | rad3-G595R RAD52 | 4.12 | 103 |

| BLY202 | rad3-G595R rad52-hisG | 2.47 | 62 |

| JC297 | RAD3 SSL2 | 0.12 | 1 |

| DG1730 | RAD3 ssl2-rtt | 7.25 | 60 |

| BLY154 | rad3-G595R SSL2 | 20.70 | 172 |

Rate of His+ colony formation was determined by the method of Drake (23).

Mutant transposition rate divided by the wild-type rate.

The rad3-G595R mutation increases Ty1 retrotransposition at specific target loci.

To examine whether the rad3-G595R mutation increased Ty1 transposition at specific target loci, we compared the efficiencies and target site preferences of Ty1 insertions at the CAN1 (Table 2) and glycine tRNA (Fig. 3) loci in isogenic wild-type and rad3-G595R mutant strains. Although Ty2 element insertions might also be detected in these assays, Ty1 insertions predominate because endogenous Ty2 elements transpose at a much lower rate than Ty1 (M. J. Curcio, B.-S. Lee, and D. J. Garfinkel, unpublished results). CAN1, which encodes an arginine permease, has been extensively analyzed as a target for Ty1 and Ty2 insertions by Southern blot, PCR, and DNA sequencing analyses (59, 74). Loss of CAN1 function causes resistance to the toxic arginine analog canavanine. The rate of canavanine resistance increased about 5.7-fold in the rad3-G595R (BLY154) mutant (Table 2). We analyzed 32 independent can1 mutant derivatives of both wild-type and rad3-G595R mutant strains by PCR for insertions within a 2.3-kb region spanning the CAN1 locus, as described previously (59). The fraction of spontaneous Ty1-induced mutations increased about 13-fold in the rad3-G595R mutant, from 6.2% (2 of 32) to about 80% (26 of 32). Therefore, the rate of Ty1 transposition into the CAN1 locus increased 75-fold in the rad3-G595R mutant. Ty1 transposition also completely accounted for the pronounced mutator phenotype observed at CAN1 in the rad3-G595R mutant, since the rate of non-Ty1-induced mutagenic events remained the same in the wild-type (4.7 × 10−8) and rad3-G595R mutant (5.2 × 10−8) strains.

TABLE 2.

Ty1 insertional mutagenesis of CAN1

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Mutation ratea (108) | Ty1 fractionb | Estimated transposition ratec (108) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JC297 | RAD3 | 4.9 | 2/32 | 0.3 |

| BLY154 | rad3-G595R | 27.6 | 26/32 | 22.4 |

Rate of canavanine resistance per cell per generation was determined by the method of Drake (23).

Thirty-two independent can1 mutants were examined by PCR to determine whether a 2.3-kb region spanning the CAN1 gene contained a Ty1 insertion.

Product of mutation rate and Ty1 fraction.

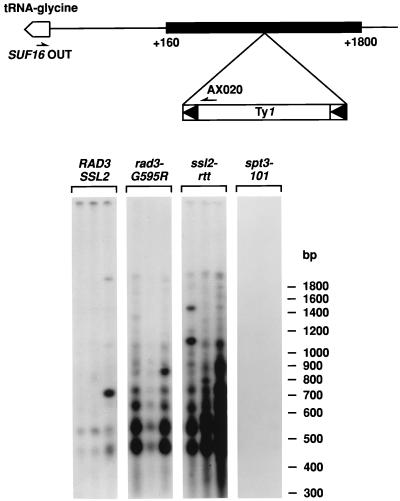

FIG. 3.

Spontaneous Ty1 transposition events upstream of glycine tRNA genes. A schematic representation of a typical glycine tRNA gene is at the top. The tRNA gene and its direction of transcription are indicated by the open arrow. Ty1 insertions are detected between 160 and 1,800 bp upstream of one or more of the 16 glycine tRNA genes dispersed in the yeast genome. Oligonucleotide primers used for PCR, designated SUF16OUT and AX020, are homologous to glycine tRNA genes and to Ty1 and Ty2 elements, respectively. Below are the patterns of Ty1 insertions upstream of the glycine tRNA genes from isogenic RAD3 SSL2 wild-type (GRF167), rad3-G595R (BLY157), ssl2-rtt (DG1722), and spt3-101 (DG789) strains. PCR products from three independent colonies were analyzed by Southern hybridization with a 32P-labeled LTR probe.

While the rate of transposition into the CAN1 locus increased in the rad3-G595R mutant, the positions of the insertions did not change. The approximate map positions of the Ty1 insertions in the rad3-G595R mutant were determined by PCR. About 54% (14 of 26) of the transpositions occurred in the 300-bp CAN1 promoter region, and approximately 46% (12 of 26) occurred elsewhere in CAN1, which is in accordance with the target site specificity observed in RAD3 cells in previous studies (59, 74).

Genomic regions upstream of tRNA genes are preferred targets for Ty1 transposition (19, 22, 34). We have developed a PCR assay to monitor insertions of unmarked Ty1 (and Ty2) elements at genomic regions upstream of the 16 dispersed glycine tRNA genes in mitotically grown cells (40). To determine whether the rad3-G595R mutation influenced Ty1 insertion events in these regions, RAD3 SSL2 wild-type (GRF167), ssl2-rtt (DG1722), rad3-G595R (BLY157), and spt3-101 (DG789) strains were grown on YPD plates for 7 days at 20°C and three independent colonies from each strain were inoculated into individual YPD liquid cultures. After 2 days of incubation at 20°C, total genomic DNA from each culture was analyzed by PCR, using one oligonucleotide primer that is specific for Ty1 and Ty2 elements (AX020) and a second oligonucleotide primer from the SUF16 glycine tRNA gene (SUF16OUT). The same amount of total genomic DNA was used in each reaction, and all DNA samples were PCR competent, as demonstrated by control reactions with oligonucleotide primers specific for the TRP1 gene and the SUF16 region on chromosome III (B.-S. Lee and D. J. Garfinkel, unpublished results). The PCR products amplified by using SUF16OUT and AX020 were analyzed by Southern blot hybridization with a 32P-labeled Ty1 LTR probe (Fig. 3).

Like ssl2-rtt, the rad3-G595R mutation markedly stimulated Ty1 transposition at tRNA targets, as is evident when the intense insertion pattern displayed by these mutants was compared with the pattern of the wild-type strain (Fig. 3). However, extended exposures of the filter showed that the insertion patterns in the wild-type, rad3-G595R, and ssl2-rtt strains were similar (B.-S. Lee and D. J. Garfinkel, unpublished results), again suggesting that the Ty1 target site specificity remained the same. The unusually intense bands evident for some of the wild-type and mutant cultures suggested that a Ty1 insertion occurred early in cell growth, creating a “jackpot” event. An isogenic spt3-101 mutant strain (DG789) in which Ty1 transcription (76) and retrotransposition (10) are severely reduced served as a negative control.

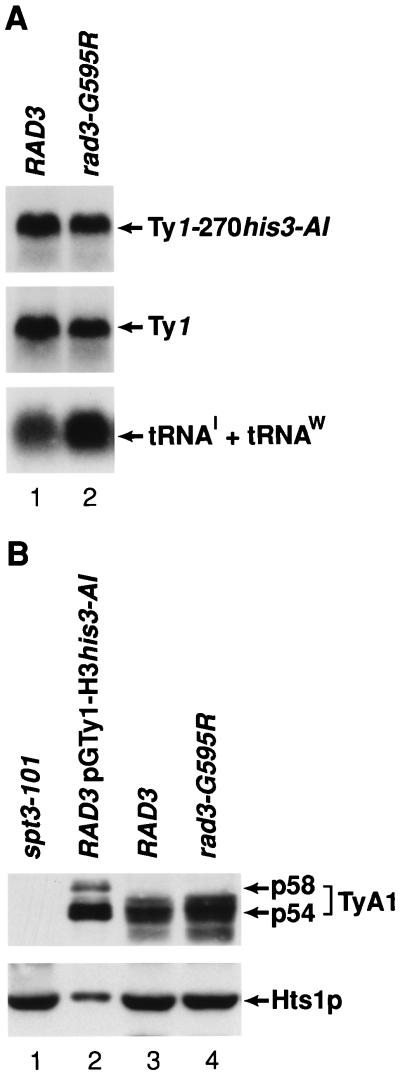

RAD3 inhibits Ty1 transposition at a posttranslational level.

To determine if the rad3-G595R mutation increases Ty1 retrotransposition by affecting the level of Ty1 or Ty1his3-AI transcripts (Fig. 4A), Northern blot analysis was performed with total RNA prepared from isogenic RAD3 wild-type (JC297) and rad3-G595R (BLY154) mutant strains. The level of the Ty1 transcripts was normalized to the level of isoleucine (tRNAI) and tryptophan (tRNAW) tRNAs, because the accumulation of tRNAI and tRNAW, which are synthesized by RNA polymerase III, is not affected in TFIIH mutants (40, 56). The levels of Ty1 and Ty1-270his3-AI transcripts in the rad3-G595R mutant decreased about twofold compared to those of the wild-type strain, as determined by PhosphorImager analysis of the filters.

FIG. 4.

Ty1 expression in RAD3 wild-type and rad3-G595R mutant cells. (A) Northern blot analysis of RAD3 wild-type (JC297) and rad3-G595R (BLY154) mutant strains. Ten-microgram quantities of total RNA from isogenic RAD3 (lane 1) and rad3-G595R (lane 2) strains were analyzed by Northern hybridization. 32P-labeled DNA probes specific for his3-AI and Ty1 were used to detect Ty1-270his3-AI (top panel) and Ty1 (middle panel) transcripts, respectively. In the bottom panel, 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probes specific for the isoleucine (tRNAI) and tryptophan (tRNAW) tRNA introns were used to detect isoleucine and tryptophan pre-tRNAs. (B) Levels of endogenous TyA1 proteins in RAD3 wild-type and rad3-G595R mutant strains. Total-protein extracts were prepared from strains DG789 (spt3-101) (lane 1), galactose-induced strain DG1741 (RAD3 wild type containing pGTy1-H3his3-AI) (lane 2), JC297 (RAD3) (lane 3), and BLY154 (rad3-G595R) (lane 4) and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–7.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. About 10 μg of protein was analyzed per lane in lanes 1, 3, and 4; about 0.6 μg of protein was analyzed in lane 2 because of the large amount of TyA1 proteins produced as a result of pGTy1 expression. After transfer to an Immobilon-P membrane, TyA1 proteins p58 and p54 and Hts1p were incubated with either VLP or Hts1p polyclonal antiserum. The band beneath p54-TyA1 in lanes 3 and 4 probably contains degraded TyA1 proteins, which are more prevalent in endogenous Ty1 protein extracts (17). Immunodetection was performed by ECL.

The RAD3 wild-type and rad3-G595R mutant strains were also subjected to Western blot analysis to determine whether the rad3-G595R mutation increased Ty1 transposition by altering the levels of endogenous TyA1 proteins p54 and p58 (Fig. 4B). Increasing the level of the mature p54-TyA1 protein along with that of mature TyB1 proteins is associated with a high level of Ty1 transposition (17, 36, 77). An immunoblot was prepared with total cellular protein extracted from a wild-type strain (DG1741) containing a pGTy1-H3 expression plasmid (pGTy1-H3his3-AI), a spt3-101 mutant strain (DG789), and isogenic RAD3 wild-type (JC297) and rad3-G595R (BLY154) mutant strains. The resulting filter was incubated with a polyclonal antiserum against Ty1 VLPs to detect p58-TyA1 and p54-TyA1 and then with a polyclonal antiserum against Hts1p, which is the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial histidyl-tRNA synthetase. The level of Hts1p was determined with the same filter used to detect TyA1 proteins, except that the antibodies bound to TyA1 proteins were removed prior to the addition of the Hts1 antiserum. The amounts of endogenous p58-TyA1 and p54-TyA1 present in RAD3 wild-type and rad3-G595R mutant strains were about the same when normalized to the level of Hts1p. Exposure of the filter for various time periods showed that the endogenous p54-TyA1 and p58-TyA1 proteins were also about the same size as the TyA1 proteins of cells expressing a pGTy1 plasmid (B.-S. Lee and D. J. Garfinkel, unpublished results). As expected, TyA1 proteins were not detected in the spt3-101 mutant.

The rad3-G595R mutation increases the accumulation of Ty1 cDNA.

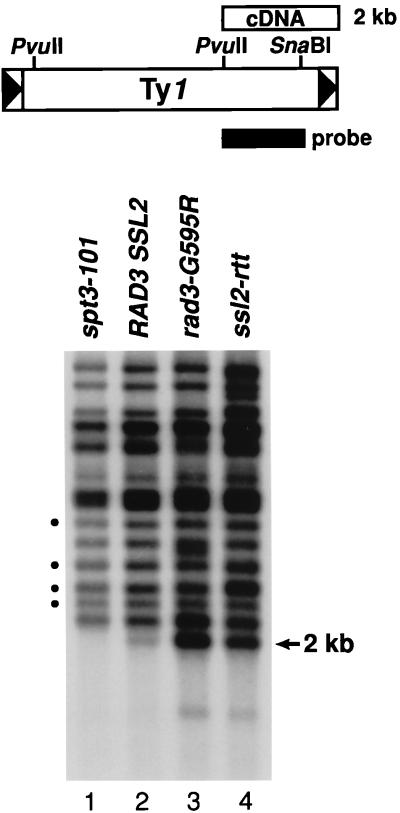

We determined the level of unincorporated Ty1 cDNA by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 5) with total DNA from RAD3 SSL2 wild-type (GRF167), rad3-G595R (BLY157), ssl2-rtt (DG1722), and spt3-101 (DG789) strains. Digestion of total DNA with PvuII generated a 2-kb fragment containing sequences from a conserved internal PvuII restriction site in Ty1 (nucleotide 3944) to the end of the linear unincorporated cDNA (nucleotide 5918), which appeared as a distinct Ty1 fragment (40). A 32P-labeled probe spanning part of this region of Ty1 was hybridized with the resulting filter, and the 2-kb Ty1 cDNA fragment was quantitated by phosphorimaging. A convenient internal control is provided by the PvuII fragments that contain preexisting Ty1 sequences joined to genomic DNA. In addition, an isogenic spt3-101 mutant (DG789) was included in the analysis because this mutant should contain very little Ty1 cDNA. When the level of Ty1 cDNA was estimated relative to the levels of several conserved Ty1-genomic DNA junction fragments, a sevenfold increase in Ty1 cDNA in the rad3-G595R mutant and a fivefold increase in the ssl2-rtt mutant were evident. The level of Ty1 cDNA detected in wild-type strains was somewhat variable (40) and, therefore, could affect the relative increase of Ty1 cDNA observed in the mutants. However, the level of Ty1 cDNA present in the rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutants always increased by the same degree when normalized to the levels of the internal Ty1-genomic DNA junction fragments. We could not detect any Ty1 cDNA in the spt3-101 mutant.

FIG. 5.

Levels of Ty1 cDNA in rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutants. The 2-kb segment of Ty1 cDNA detected by Southern blot analysis of total yeast DNA digested with PvuII is shown schematically at the top of the figure. A Ty1 element is depicted along with PvuII (nucleotide positions 475 and 3944) and SnaBI (position 5461) restriction sites (7). The solid bar represents the 1.5-kb PvuII-SnaBI restriction fragment used as a 32P-labeled hybridization probe to detect unincorporated Ty1 cDNA. Total DNA was prepared after isogenic strains DG789 (spt3-101) (lane 1), GRF167 (RAD3 SSL2 [wild type]) (lane 2), BLY157 (rad3-G595R) (lane 3), and DG1722 (ssl2-rtt) (lane 4) were grown to mid- to late log phase at 20°C; it was then digested with PvuII and subjected to Southern analysis. The positions of the 2.0-kb Ty1 cDNA and four conserved junction fragments (circles) used for normalization are shown on the sides.

Ty1 cDNA stability increases in the rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutants.

We next measured the decay rates of unincorporated Ty1 cDNA after blocking reverse transcription with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RT inhibitor PFA (Foscarnate) (5) to determine whether the rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutations affected cDNA stability (Fig. 6). We initially found that PFA at a concentration of 200 μg/ml largely inhibited Ty1ade2-AI transposition in isogenic SSL2 and ssl2-rtt strains without affecting cell growth (B.-S. Lee and D. J. Garfinkel, unpublished results). Ty1 cDNA was undetectable in the rad3-G595R (BLY157), ssl2-rtt (DG1722), and wild-type RAD3 SSL2 (GRF167) strains when cells were grown in the presence of PFA for about 48 h (Fig. 6A). As expected, the spt3-101 mutant also contained an undetectable amount of Ty1 cDNA. Decay rates of Ty1 cDNA were measured in isogenic RAD3 SSL2 wild-type (GRF167), rad3-G595R (BLY157), and ssl2-rtt (DG1722) strains after addition of PFA to mid-log-phase cells and withdrawal of aliquots of cells at various times for Southern blot analysis and phosphorimaging (Fig. 6A). The half-lives of Ty1 cDNA in the rad3-G595R (>600 min) and ssl2-rtt (>300 min) mutants were increased at least six- and threefold, respectively, compared with that of the wild-type strain (110 min) (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Stability of Ty1 cDNA in ssl2-rtt and rad3-G595R mutants. (A) Southern blot analysis of Ty1 cDNA from isogenic strains that were treated with the RT inhibitor PFA. DNA was prepared from strain DG789 (spt3-101) (lane 1), which was not treated with PFA, and strains GRF167 (RAD3 SSL2 wild type) (lane 2), DG1722 (ssl2-rtt) (lane 3), and BLY157 (rad3-G595R) (lane 4), which were grown in the presence of PFA (200 μg/ml) for about 48 h. The resulting DNA samples were digested with PvuII and analyzed by Southern blot hybridization with a 32P-labeled probe from the Ty1 RT coding region (40). Decay rates of Ty1 cDNA were determined for the RAD3 SSL2 wild-type strain (lanes 5 to 10), the ssl2-rtt mutant (lanes 11 to 16), and the rad3-G595R mutant (lanes 17 to 22), which were treated with PFA for various periods of time and then processed for Southern blot analysis described as in Materials and Methods and in the legend to Fig. 5. An aliquot of cells was withdrawn from each culture at the time of PFA addition (0 min) (lanes 5, 11, and 17) and at 30 min (lanes 6, 12, and 18), 60 min (lanes 7, 13, and 19), 120 min (lanes 8, 14, and 20), 240 min (lanes 9, 15, and 21), and 360 min (lanes 10, 16, and 22) after PFA addition. The level of unincorporated Ty1 cDNA in each culture was monitored by determining the amount of a 2.0-kb fragment generated by PvuII digestion. Four conserved Ty1-chromosomal DNA junction fragments (circles) were used for normalization of the Ty1 cDNA level. (B) Ty1 cDNA decay curves were plotted on a log scale as the percentage of Ty1 cDNA remaining relative to the level of Ty1 cDNA at time zero versus elapsed time. All Ty1 cDNA hybridization signals were normalized to that of the four conserved Ty1-chromosomal DNA junction fragments shown in panel A. The kinetics of Ty1 cDNA decay for the wild-type (closed circles, solid line), ssl2-rtt (open circles, dashed line), and rad3-G595R (closed squares, dotted line) strains are shown.

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that Rad3 and Ssl2 inhibit SSR and Ty1 retrotransposition by similar mechanisms. The most compelling evidence connecting these processes is the increased stability of free DNA ends and unincorporated Ty1 cDNA in both rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutants. Increasing the stability of linear DNA leads to significantly higher levels of SSR and Ty1 retrotransposition. Stabilizing free DNA ends may give the recombinational machinery enough time to process the shorter homologous sequences for recombination before these sequences are removed by degradation (2, 3, 42). In the case of Ty1, the accumulation of unincorporated Ty1 cDNA appears to be a major rate-limiting step in the process of retrotransposition in vitro (24) and in vivo (14, 40, 57).

An important implication of our work is that the core NER/TFIIH complex plays a critical role in restricting SSR and Ty1 retrotransposition. The core complex has DNA binding and bidirectional DNA helicase activities and contains several proteins, including Tfb1, Tfb2, Tfb3, Tfb4, Ssl1, and the Rad3 helicase (26, 27). The Ssl2 helicase may be more loosely associated with the core complex (66, 69), although a direct interaction between Rad3 and Ssl2 has been reported (4). Ssl1 also interacts directly with Rad3, but not with Ssl2. Interestingly, the human homolog of Ssl1, p44, has been shown to stimulate the helicase activity of XPD/Rad3 (13). In addition, RAD3 and SSL1 interact to inhibit SSR and Ty1 retrotransposition (42; B.-S. Lee and D. J. Garfinkel, unpublished results). Because the core NER/TFIIH complex can be part of several different assemblies in the cell (21, 52, 69), identification of additional genes responsible for preventing both SSR and Ty1 retrotransposition will determine whether the entire core complex is involved as well as whether there is an independent protein assemblage dedicated to inhibiting SSR and Ty1 retrotransposition. Furthermore, our results suggest that the core NER/TFIIH complex may interact with all free DNA ends produced in the cell.

Here we show that the rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutations increase DNA fragment insertion to comparable levels when the sequence lengths are below the threshold required for efficient homologous recombination. As the length of homology increases, ssl2-rtt does not increase SSR as much as rad3-G595R does. The ssl2-rtt mutation almost doubles the half-life of HO-digested plasmid DNA in vivo but again is less potent than rad3-G595R. These results suggest that both rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt increase SSR; however, these mutations may have different effects on the control of recombination between longer sequences. It will be interesting to determine whether these mutations also differentially affect SSR between repeated sequences integrated in the genome.

The process of Ty1 element retrotransposition involves both cytoplasmic and nuclear phases; therefore, it is important to determine the step at which a cellular product acts to modulate retrotransposition. Like ssl2-rtt (40), the rad3-G595R mutation does not alter the level of TyA1 proteins p54 and p58 or Ty1 target site specificity either at CAN1 or upstream of glycine tRNAs. The levels of genomic Ty1 and Ty1his3-AI transcripts decrease about twofold in a rad3-G595R mutant, which is comparable to the decreases observed for SAM1 and URA3 transcripts in previous work (42). Together these results suggest that rad3-G595R stimulates Ty1 transposition posttranslationally, completely consistent with its role in modulating the level of Ty1 cDNA. In addition, the rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutations (40) as well as mutations in DNA repair and recombination genes of the RAD52 epistasis group (57) are similar in that all increase Ty1 transposition without markedly altering Ty1 gene expression or target site selectivity. Conversely, mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase gene FUS3 stimulate Ty1 transposition by increasing the stability of TyA1 and TyB1 proteins (14), and genes that affect chromatin, such as RAD6 (41), HIR3, and CAC3 (33), enhance Ty1 transposition by relaxing target site specificity within genes transcribed by RNA polymerase II.

We have shown that the rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutations increase the steady-state level of Ty1 cDNA more than fivefold. Lee et al. suggested that Rad3 and Ssl2 prevent the accumulation of Ty1 cDNA by either inhibiting reverse transcription or degrading unincorporated cDNA after reverse transcription (40). To distinguish between these distinctly different mechanisms, we have measured the decay rates of Ty1 cDNA in rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutants after inhibiting Ty1 reverse transcription with the RT inhibitor PFA. Our results show that Ty1 cDNA stability is affected by Rad3 and Ssl2, because the half-life of Ty1 cDNA significantly increases in the rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutants. The level of Ty1 RT activity is also unaffected by ssl2-rtt (B.-S. Lee and D. J. Garfinkel, unpublished results), which suggests that reverse transcription is not inhibited by a Rad3- and Ssl2-dependent process. Furthermore, both Ty1his3-AI transposition and the steady-state level and half-life of Ty1 cDNA increase more in the rad3-G595R mutant than in the ssl2-rtt mutant, which is consistent with the results obtained with the SSR assay and HO-digested plasmid DNA. Together these results reinforce the idea that Rad3 and Ssl2 influence the stability of DNA with free ends via similar mechanisms.

We present the following models to explain how the Rad3- and Ssl2-dependent assembly directly maintains genome stability, based on the characterization of the rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutants. We have assumed that several different DNA processing pathways compete for free DNA ends or Ty1 cDNA, because these types of molecules are highly reactive in S. cerevisiae (53). The rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutations may also alter the helicase activity of the relevant complex (3, 40) since the mutations are located either within or near well-conserved motifs involved in nucleotide binding or in coupling hydrolysis to helicase activity (65, 72). However, genetic data have shown that the rad3-20 mutation, which changes a codon in the ATP binding domain required for helicase activity and NER (48, 67), confers a wild-type level of SSR (2) and Ty1 transposition (B.-S. Lee and D. J. Garfinkel, unpublished results). Together these results suggest that the helicase activity of Rad3 is required for NER but may not be directly involved in preventing SSR and Ty1 transposition. Instead, Rad3 may play an important structural role through its interactions with Ssl1 and the Ssl2 helicase (4, 42) that may alter the function of the core NER/TFIIH complex. The synthetic lethality reported here for the rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutations also suggests that Rad3 and Ssl2 might play compensatory roles within the complex.

In one model, the free DNA ends are recognized by factors that recruit or are already part of the relevant Rad3-Ssl2 assembly. This process may facilitate the action of the Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 complex, which is required for free-DNA-end processing during repair of DNA double-strand breaks (53). The helicase activity of the assembly promotes unwinding of the DNA and subsequent attack by cellular nucleases, which result in the degradation of DNA at or near the free DNA end. The results described here and in previous work (2, 3, 42) suggest that the level of free-DNA-end degradation observed in wild-type cells is sufficient to inhibit recombination between sequences shorter than 300 bp. Alternatively, the helicase activity of the Rad3- and Ssl2-dependent assemblage may dissolve the unstable heteroduplexes formed when short homologous sequences interact. This might involve the bidirectional helicase activities of the complex, because Rad51-catalyzed heteroduplex formation can proceed 3′ to 5′ (68) or 5′ to 3′ (47).

Ty1 retrotransposition presents additional complexities because genomic Ty1 elements are highly homologous to the 5.9-kb unincorporated Ty1 cDNA, and IN-mediated integration should be a major pathway competing for Ty1 cDNA utilization in addition to pathways leading to Rad3- and Ssl2-dependent DNA degradation and homologous recombination. We propose that when the Ty1 preintegration complex enters the nucleus, most of the Ty1 cDNA undergoes Rad3- and Ssl2-dependent DNA degradation in a fashion similar to that proposed to occur during SSR. The fact that rad3-G595R or ssl2-rtt increases Ty1his3-AI transposition more than 60-fold suggests that transpositional integration does not compete very well with the Rad3-Ssl2 degradative pathway for Ty1 cDNA. Epistasis analysis of a rad52 null mutation suggests that most of the Ty1his3-AI-mediated His+ colony formation events occurring in the rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutants are de novo Ty1 retrotranspositions and do not result exclusively from cDNA recombination. These results suggest that IN-mediated integration may be preferred over cDNA recombination when the Rad3-Ssl2 degradative pathway is blocked. However, the observation that Ty1his3-AI transposition increases in a rad52 mutant suggests that some Ty1 cDNA enters the recombinational repair pathway (15, 40, 57).

Neither of our models rules out the formal possibility that the altered levels of SSR and Ty1 retrotransposition observed in the rad3-G595R and ssl2-rtt mutants result from defective transcription of critical control genes. However, previous results suggest that the changes in transcription in the rad3-G595R mutant cannot account for the increased levels of SSR (42). In addition, suppressor analysis suggests that the effect of ssl2-rtt on transcription and retrotransposition can be genetically separated (B.-S. Lee and D. J. Garfinkel, unpublished results).

Although we suggest that the mechanisms for the degradation of free DNA ends and Ty1 cDNA are similar, there are functional differences between Rad3 and Ssl2 that may influence DNA degradation. For example, the observation that the helicase activity of Rad3 is dispensable for viability (67) whereas the Ssl2 helicase activity is not (54) demonstrates that Rad3 and Ssl2 have distinct functions. Additional RAD3 and SSL2 alleles that affect SSR and Ty1 retrotransposition differently may also be identified. Other features of Rad3- and Ssl2-dependent degradation should become evident as more genes that participate in this process are identified. In this regard, it will be interesting to identify the nucleases that act in conjunction with Rad3 and Ssl2 to degrade DNA. One attractive set of candidates includes several genes related to the RAD2 nuclease, which might recognize the structures produced by a DNA helicase (21).

In this work, we have connected SSR and Ty1 retrotransposition at the molecular level. It has not escaped our attention that the human diseases XP, Cockayne's syndrome, and TTD are caused by mutations in the XPD (RAD3) and XPB (SSL2) genes. In particular, several XPD alleles that cause XP or TTD and the rad3-G595R mutation are located in the same conserved region of XPD/RAD3 (70). One intriguing speculation is that SSR or retroelement movement contributes to the complex pathology of these diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments of G. Manthey and M. C. Negritto. We also thank M. J. Curcio, J. Nickoloff, and F. Heffron for plasmids and R. Malone for yeast strains. This research was sponsored in part by the National Cancer Institute, Department of Health and Human Services. L.B. and A.M.B. are funded by Public Health Service grants GM57484 and CA33572.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alani E, Cao L, Kleckner N. A method for gene disruption that allows repeated use of URA3 selection in the construction of multiply disrupted yeast strains. Genetics. 1987;116:541–545. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.541.test. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailis A M, Maines S. Nucleotide excision repair gene function in short-sequence recombination. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2136–2140. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2136-2140.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailis A M, Maines S, Negritto M T. The essential helicase gene RAD3 suppresses short-sequence recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3998–4008. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.3998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardwell L, Bardwell A J, Feaver W J, Svejstrup J Q, Kornberg R D, Friedberg E C. Yeast RAD3 protein binds directly to both SSL2 and SSL1 proteins: implications for the structure and function of transcription/repair factor b. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3926–3930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergdahl S, Jacobsson B, Moberg L, Sonnerborg A. Pronounced anti-HIV-1 activity of foscarnet in patients without cytomegalovirus infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;18:51–53. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199805010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boeke J D, Devine S E. Yeast retrotransposons: finding a nice quiet neighborhood. Cell. 1998;93:1087–1089. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boeke J D, Eichinger D, Castrillon D, Fink G R. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome contains functional and nonfunctional copies of transposon Ty1. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:1432–1442. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.4.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boeke J D, Garfinkel D J, Styles C A, Fink G R. Ty elements transpose through an RNA intermediate. Cell. 1985;40:491–500. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boeke J D, Sandmeyer S B. Yeast transposable elements. In: Pringle J R, Jones E W, Broach J R, editors. The molecular and cellular biology of the yeast Saccharomyces: genome dynamics, protein synthesis, and energetics. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1991. pp. 193–261. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boeke J D, Styles C A, Fink G R. Saccharomyces cerevisiae SPT3 gene is required for transposition and transpositional recombination of chromosomal Ty elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:3575–3581. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.11.3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bootsma D, Kraemer K H, Cleaver J, Hoeijmakers J H J. Nucleotide excision repair syndromes: xeroderma pigmentosum, Cockayne syndrome, and trichothiodystrophy. In: Scriver C R, Beaudet A L, Sly W S, Valle D, editors. The metabolic basis of inherited disease. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill; 1997. pp. 245–274. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Britten R J, Kohne D E. Repeated sequences in DNA. Hundreds of thousands of copies of DNA sequences have been incorporated into the genomes of higher organisms. Science. 1968;161:529–540. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3841.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coin F, Marinoni J C, Egly J M. Mutations in XPD helicase prevent its interaction and regulation by p44, another subunit of TFIIH, resulting in xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) and trichothiodystrophy (TTD) phenotypes. Pathol Biol. 1998;46:679–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conte D, Jr, Barber E, Banerjee M, Garfinkel D J, Curcio M J. Posttranslational regulation of Ty1 retrotransposition by mitogen-activated protein kinase Fus3. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2502–2513. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curcio M J, Garfinkel D J. Heterogeneous functional Ty1 elements are abundant in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Genetics. 1994;136:1245–1259. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.4.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curcio M J, Garfinkel D J. New lines of host defense: inhibition of Ty1 retrotransposition by Fus3p and NER/TFIIH. Trends Genet. 1999;15:43–45. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curcio M J, Garfinkel D J. Posttranslational control of Ty1 retrotransposition occurs at the level of protein processing. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2813–2825. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.6.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curcio M J, Garfinkel D J. Single-step selection for Ty1 element retrotransposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:936–940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curcio M J, Morse R H. Tying together integration and chromatin. Trends Genet. 1996;12:436–438. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)30107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalgaard J Z, Banerjee M, Curcio M J. A novel Ty1-mediated fragmentation method for native and artificial yeast chromosomes reveals that the mouse steel gene is a hotspot for Ty1 integration. Genetics. 1996;143:673–683. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.2.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Laat W L, Jaspers N G J, Hoeijmakers J H J. Molecular mechanism of nucleotide excision repair. Genes Dev. 1999;13:768–785. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devine S E, Boeke J D. Integration of the yeast retrotransposon Ty1 is targeted to regions upstream of genes transcribed by RNA polymerase III. Genes Dev. 1996;10:620–633. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.5.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drake J W. The molecular basis of mutation. San Francisco, Calif: Holden-Day; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eichinger D J, Boeke J D. A specific terminal structure is required for Ty1 transposition. Genes Dev. 1990;4:324–330. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farabaugh P J. Post-transcriptional regulation of transposition by Ty retrotransposons of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10361–10364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feaver W J, Henry N L, Wang Z, Wu X, Svejstrup J Q, Bushnell D A, Friedberg E C, Kornberg R D. Genes for Tfb2, Tfb3, and Tfb4 subunits of yeast transcription/repair factor IIH. Homology to human cyclin-dependent kinase activating kinase and IIH subunits. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19319–19327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedberg E C, Bardwell A J, Bardwell L, Feaver W J, Kornberg R D, Svejstrup J Q, Tomkinson A E, Wang Z. Nucleotide excision repair in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: its relationship to specialized mitotic recombination and RNA polymerase II basal transcription. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1995;347:63–68. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1995.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garfinkel D J. Retroelements in microorganisms. In: Levy J A, editor. The Retroviridae. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1992. pp. 107–158. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gulyas K D, Donahue T F. SSL2, a suppressor of a stem-loop mutation in the HIS4 leader, encodes the yeast homolog of human ERCC-3. Cell. 1992;69:1031–1042. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90621-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guthrie C, Fink G R. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. Vol. 194. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guzder S N, Sung P, Bailly V, Prakash L, Prakash S. RAD25 is a DNA helicase required for DNA repair and RNA polymerase II transcription. Nature. 1994;369:578–581. doi: 10.1038/369578a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guzder S N, Sung P, Prakash L, Prakash S. Nucleotide excision repair in yeast is mediated by sequential assembly of repair factors and not by a preassembled repairosome. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8903–8910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang H, Hong J Y, Burck C L, Liebman S W. Host genes that affect the target-site distribution of the yeast retrotransposon Ty1. Genetics. 1999;151:1393–1407. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji H, Moore D P, Blomberg M A, Braiterman L T, Voytas D F, Natsoulis G, Boeke J D. Hotspots for unselected Ty1 transposition events on yeast chromosome III are near tRNA genes and LTR sequences. Cell. 1993;73:1007–1018. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jinks-Robertson S, Michelitch M, Ramcharan S. Substrate length requirements for efficient mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3937–3950. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawakami K, Pande S, Faiola B, Moore D P, Boeke J D, Farabaugh P J, Strathern J N, Nakamura Y, Garfinkel D J. A rare tRNA-Arg (CCU) that regulates Ty1 element ribosomal frameshifting is essential for Ty1 retrotransposition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1993;135:309–320. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.2.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kenna M A, Brachmann C B, Devine S E, Boeke J D. Invading the yeast nucleus: a nuclear localization signal at the C terminus of Ty1 integrase is required for transposition in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1115–1124. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolodner R D, Marsischky G T. Eukaryotic DNA mismatch repair. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)80013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee B-S, Culbertson M R. Identification of an additional gene required for eukaryotic nonsense mRNA turnover. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10354–10358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee B-S, Lichtenstein C P, Faiola B, Rinckel L A, Wysock W, Curcio M J, Garfinkel D J. Posttranslational inhibition of Ty1 retrotransposition by nucleotide excision repair/transcription factor TFIIH subunits Ssl2p and Rad3p. Genetics. 1998;148:1743–1761. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.4.1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liebman S W, Newnam G. A ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, RAD6, affects the distribution of Ty1 retrotransposon integration positions. Genetics. 1993;133:499–508. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.3.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maines S, Negritto M C, Wu X, Manthey G M, Bailis A M. Novel mutations in the RAD3 and SSL1 genes perturb genome stability by stimulating recombination between short repeats in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1998;150:963–976. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.3.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manivasakam P, Weber S C, McElver J, Schiestl R H. Micro-homology mediated PCR targeting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2799–2800. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.14.2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Melamed C, Nevo Y, Kupiec M. Involvement of cDNA in homologous recombination between Ty elements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1613–1620. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.4.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Montelone B A, Hoekstra M F, Malone R E. Spontaneous mitotic recombination in yeast: the hyper-recombinational rem1 mutations are alleles of the RAD3 gene. Genetics. 1988;119:289–301. doi: 10.1093/genetics/119.2.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moore S P, Rinckel L A, Garfinkel D J. A Ty1 integrase nuclear localization signal required for retrotransposition. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1105–1114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Namsaraev E, Berg P. Characterization of strand exchange activity of yeast Rad51 protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5359–5368. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naumovski L, Friedberg E C. Analysis of the essential and excision repair functions of the RAD3 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by mutagenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:1218–1227. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.4.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Negritto M T, Wu X, Kuo T, Chu S, Bailis A M. Influence of DNA sequence identity on efficiency of targeted gene replacement. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:278–286. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nickoloff J A, Hoekstra M F. Double-strand break and recombinational repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Nickoloff J A, Hoekstra M F, editors. DNA damage and repair, vol. 1. DNA repair in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Totowa, N.J: Human Press Inc.; 1998. pp. 335–362. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nickoloff J A, Chen E Y, Heffron F. A 24-base-pair DNA sequence from the MAT locus stimulates intergenic recombination in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7831–7835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.20.7831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orphanides G, Lagrange T, Reinberg D. The general transcription factors of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2657–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pâques F, Haber J E. Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:349–404. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.349-404.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park E, Guzder S N, Koken M H, Jaspers-Dekker I, Weeda G, Hoeijmakers J H, Prakash S, Prakash L. RAD25 (SSL2), the yeast homolog of the human xeroderma pigmentosum group B DNA repair gene, is essential for viability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11416–11420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petes T D, Hill C W. Recombination between repeated sequences in microorganisms. Annu Rev Genet. 1988;22:147–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.001051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qiu H, Park E, Prakash L, Prakash S. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA repair gene RAD25 is required for transcription by RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2161–2171. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rattray A J, Shafer B K, Garfinkel D J. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA recombination and repair functions in the RAD52 epistasis group inhibit Ty1 transposition. Genetics. 1999;154:543–556. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.2.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reynolds R J, Love J D, Friedberg E C. Molecular mechanisms of pyrimidine dimer excision in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: excision of dimers in cell extracts. J Bacteriol. 1981;147:705–708. doi: 10.1128/jb.147.2.705-708.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rinckel L A, Garfinkel D J. Influences of histone stoichiometry on the target site preference of retrotransposons Ty1 and Ty2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1996;142:761–776. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.3.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sharon G, Burkett T J, Garfinkel D J. Efficient homologous recombination of Ty1 element cDNA when integration is blocked. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6540–6551. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.6540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sherman F, Fink G R, Hicks J B. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sikorski R S, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Song J M, Montelone B A, Siede W, Friedberg E C. Effects of multiple yeast rad3 mutant alleles on UV sensitivity, mutability, and mitotic recombination. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6620–6630. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6620-6630.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Subramanya H S, Bird L E, Brannigan J A, Wigley D B. Crystal structure of a DExx box DNA helicase. Nature. 1996;384:379–383. doi: 10.1038/384379a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sung P, Guzder S N, Prakash L, Prakash S. Reconstitution of TFIIH and requirement of its DNA helicase subunits, Rad3 and Rad25, in the incision step of nucleotide excision repair. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10821–10826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sung P, Higgins D, Prakash L, Prakash S. Mutation of lysine-48 to arginine in the yeast RAD3 protein abolishes its ATPase and DNA helicase activities but not the ability to bind ATP. EMBO J. 1988;7:3263–3269. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sung P, Robberson D L. DNA strand exchange mediated by a RAD51-ssDNA nucleoprotein filament with polarity opposite to that of RecA. Cell. 1995;82:453–461. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90434-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Svejstrup J Q, Wang Z, Feaver W J, Wu X, Bushnell D A, Donahue T F, Friedberg E C, Kornberg R D. Different forms of TFIIH for transcription and DNA repair: holo-TFIIH and a nucleotide excision repairosome. Cell. 1995;80:21–28. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90447-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Taylor E M, Broughton B C, Botta E, Stefanini M, Sarasin A, Jaspers N G, Fawcett H, Harcourt S A, Arlett C F, Lehmann A R. Xeroderma pigmentosum and trichothiodystrophy are associated with different mutations in the XPD (ERCC2) repair/transcription gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8658–8663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thomas B J, Rothstein R. The genetic control of direct-repeat recombination in Saccharomyces: the effect of rad52 and rad1 on mitotic recombination at GAL10, a transcriptionally regulated gene. Genetics. 1989;123:725–738. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.4.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Walker J E, Saraste M, Runswick M J, Gay N J. Distantly related sequences in the alpha- and beta-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wilcox D R, Prakash L. Incision and postincision steps of pyrimidine dimer removal in excision-defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1981;148:618–623. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.2.618-623.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wilke C M, Heidler S H, Brown N, Liebman S W. Analysis of yeast retrotransposon Ty insertions at the CAN1 locus. Genetics. 1989;123:655–665. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.4.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Winston F. Analysis of SPT genes: a genetic approach toward analysis of TFIID, histones, and other transcription factors in yeast. In: Yamamoto K R, McKnight S L, editors. Transcriptional regulation. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. pp. 1271–1294. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Winston F, Durbin K J, Fink G R. The SPT3 gene is required for normal transcription of Ty elements in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1984;39:675–682. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90474-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Youngren S D, Boeke J D, Sanders N J, Garfinkel D J. Functional organization of the retrotransposon Ty from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Ty protease is required for transposition. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:1421–1431. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.4.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]