Abstract

Transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis (ATTR-CA) is increasingly diagnosed owing to the emergence of noninvasive imaging and improved awareness. Clinical penetrance of pathogenic alleles is not complete and therefore there is a large cohort of asymptomatic transthyretin variant carriers. Screening strategies, monitoring, and treatment of subclinical ATTR-CA requires further study. Perhaps the most important translational triumph has been the development of effective therapies that have emerged from a biological understanding of ATTR-CA pathophysiology. These include recently proven strategies of transthyretin protein stabilization and silencing of transthyretin production. Data on neurohormonal blockade in ATTR-CA are limited, with the primary focus of medical therapy on judicious fluid management. Atrial fibrillation is common and requires anticoagulation owing to the propensity for thrombus formation. Although conduction disease and ventricular arrhythmias frequently occur, little is known regarding optimal management. Finally, aortic stenosis and ATTR-CA frequently coexist, and transcatheter valve replacement is the preferred treatment approach.

Key Words: amyloidosis, cardiomyopathy, heart failure

Abbreviations and Acronyms: 6MWT, 6-minute walk test; AF, atrial fibrillation; AL, light chain amyloid; AS, aortic stenosis; ASO, antisense oligonucleotide; ATTR-CA, transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis; ATTRv, variant transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis; ATTRwt, wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; DCCV, direct current cardioversion; HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; SAP, serum amyloid P component; siRNA, small interfering RNA; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement

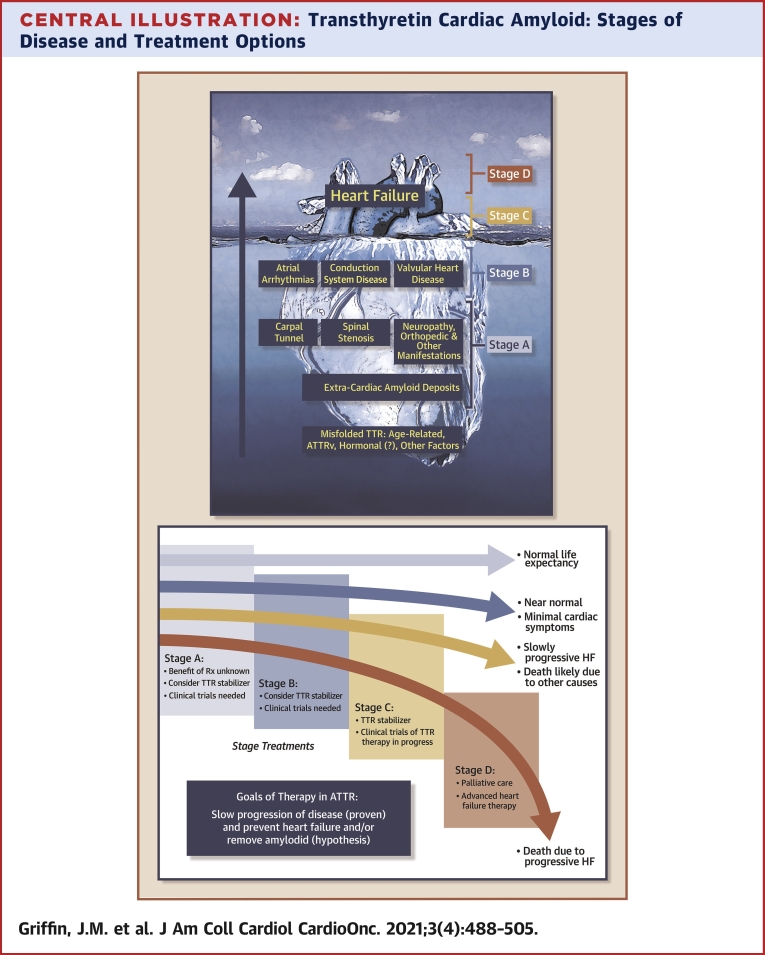

Central Illustration

Highlights

-

•

ATTR-CA is increasingly recognized owing to improved awareness and emergence of noninvasive diagnostic pathways.

-

•

Clinical penetrance of pathogenic alleles is incomplete, with limited data for screening or management of asymptomatic carriers.

-

•

Biological understanding of ATTR-CA pathology has led to effective targeted therapies of TTR stabilizers and silencers.

-

•

Potential future treatments include CRISPR, amyloid extraction/degradation, and inhibition of amyloid seeding.

Over the past decade, there has been a transformation in the field of transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis (ATTR-CA) with an increasing recognition that many ATTR-CA patients were previously undiagnosed and instead presumed to have hypertensive heart disease, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (1). Delays in diagnosis were nearly universal and, unfortunately, still persist today (2). However, with increased awareness of clinical clues, coupled with the ability to diagnose ATTR-CA without a biopsy (3) reports have demonstrated ATTR-CA in patients hospitalized with HFpEF (∼13%) (4), in patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) (∼16%) (5), and in up to 40% of high-risk populations, such as Afro-Caribbeans with heart failure and increased ventricular wall thickness (6). Thus, every cardiologist has encountered patients with ATTR-CA, whether recognized or unappreciated. Despite the use of cardiac bone scintigraphy increasing exponentially and multisocietal guidelines supporting the nonbiopsy diagnosis (7,8), there are important pitfalls to avoid. These include failing to assess for monoclonal proteins or the overreliance on planar imaging (9). However, the most important “translational triumph” has been the development of effective therapies that have emerged from a biological understanding of the underlying pathophysiology (10). These therapies have meaningful effects on the quality and quantity of affected individuals’ lives. This review focuses on the management of patients with ATTR-CA and the emerging treatment landscape (Central Illustration).

Central Illustration.

Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloid: Stages of Disease and Treatment Options

(Top) ATTR: scope of the problem. Large at-risk populations (stage A) and structural heart disease not yet identified as due to ATTR (stage B). Most patients in the current era are not diagnosed until the onset of overt heart failure (stages C and D). (Bottom) Goals of therapy in ATTR and the potential impact on natural history of ATTR-CA. ATTR = transthyretin amyloid; ATTRv = variant transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis; CA = cardiac amyloidosis; HF = heart failure.

Management of Heart Failure in ATTR-CA

ATTR-CA is classified according to the presence or absence of a mutation in the TTR gene (Table 1). Wild-type CA (ATTRwt; no mutation) occurs with aging, whereas variant CA (ATTRv; hereditary) occurs with the presence of a single amino acid substitution in the 127- amino acid chain. There are more than 130 known pathogenic TTR variants, named according to the site of amino acid substitution; p.V142I (legacy nomenclature V122I, which omits the 20-amino acid signal peptide), for example, refers to the substitution of valine for isoleucine at position 142 of the protein. This substitution renders the protein kinetically unstable and prone to dissociation and aggregation in the form of amyloid fibrils. ATTR-CA leads to a progressive restrictive physiology with reduced stroke volume, decreased compliance, and compromised cardiac output. Studies directly addressing the benefit of traditional heart failure (HF) medical therapy for ATTR-CA remain limited. In the absence of definitive data, expert consensus opinion and documents currently guide clinical practice (11,12).

Table 1.

Demographic, Genetic, Phenotypic Differences Among Main Types of ATTR-CA

| ATTRwt | ATTRv |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p.V142I (V122I) | p.T80A (T60A) | p.V50M (V30M) | ||

| Average age, y (range) | 80 (60-100) | 75 (55-90) | 67 (50-85) | 37 (18-85)a |

| Male, % | 85%-90% | 60%-70%b | 60%-70%b | 50%b |

| Race/ethnicity/country of origin | Predominantly White | Afro-Caribbean | Irish | Portuguese, Swedish, Japanese |

| Genetics | Nongenetic | Autosomal dominant | ||

| Phenotype | Predominantly cardiac; orthopedic manifestations: carpal tunnel syndrome, lumbar spinal stenosis, biceps tendon rupture | Mainly cardiac; autonomic dysfunction and peripheral neuropathy rare clinically | Mixed phenotype with both cardiac and neuropathic (peripheral and autonomic) | Mainly neuropathic phenotype but more cardiac involvement with advancing age (>50 y) and in nonendemic regions |

Depends on endemic vs nonendemic areas, early vs late age onset.

Age of disease penetrance is later in women than in men.

Loop diuretics are foundational for maintaining fluid balance in ATTR-CA, with a delicate balance between relieving congestion while maintaining adequate preload (11). The restrictive nature of ATTR-CA necessitates higher filling pressures to maintain cardiac output. As a result, these patients are prone to organ hypoperfusion with aggressive diuresis, most commonly in the form of acute kidney injury, such that close attention should be paid when managing volume. Furosemide is typically the first-line diuretic, but for those with inadequate response, torsemide or bumetanide offer greater potency and bioavailability. Aldosterone antagonists can be synergistic as adjunctive therapy for potassium sparing. For loop diuretic–refractory congestion, augmentation with thiazides enhances natriuresis. Outpatient administration of intravenous diuretics may be effective in ATTR-CA patients with suboptimal response to oral regimens. In a recent study of an ambulatory diuresis clinic in CA patients, intravenous diuretics were administered at 28% of clinic visits. No participants experienced symptomatic hypotension or severe kidney injury. Subsequent to establishing care at the diuresis clinic, there was a significant decrease in emergency department visits and inpatient admissions (13). We have previously shown a strong association between diuretic dose and mortality in an ATTR-CA cohort independent from other prognostic factors (14). The accelerating need for diuretics likely serves as a surrogate for disease progression.

While there is a lack of data regarding the use of outpatient pulmonary artery pressure monitoring specifically in ATTR-CA patients, the benefit for reducing HF hospitalizations in other cohorts is well established (15). A remote monitoring–guided strategy may be effective in ATTR-CA patients because of the heightened need for fluid balance within a narrow therapeutic window.

Expert consensus documents recommend against the use of standard HF therapies in ATTR-CA. While many ATTR-CA patients may have preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), a substantial portion will have reduced LVEF (16,17). There are no guideline-based recommendations for neurohormonal antagonists, and most recommendations are based on expert opinion. Pressure-volume relationships in ATTR-CA show abnormalities in passive ventricular filling and altered ventricular-vascular coupling that reduce the ability of the left ventricle to perform work (18). The resultant lower stroke volume index is associated with greater mortality (16). Thus, beta-blockers may be harmful by further reducing cardiac output in ATTR-CA patients who are heart rate dependent, owing to a relatively fixed low stroke volume (11,12). Given their unproven benefit and potential harm, de-escalation of beta-blockers should be considered in those with symptomatic hypotension and slow heart rates. Beta-blocker therapy may be required for rate control of atrial arrhythmias, but the lowest effective dose is recommended. Concerns with other HF therapies, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin receptor-blockers (ARB), and angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI), relate predominantly to risk for symptomatic hypotension. However, data concerning the use of these agents and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors are lacking in ATTR-CA. The use of standard HF therapy in ATTR-CA will evolve with more experience and diagnosis at earlier stages.

Postural hypotension can occur, especially in ATTRv with coexistent autonomic neuropathy (19). Pharmacologic treatment with midodrine or droxidopa and compression stockings may be helpful (20). Because concurrent neurologic and cardiac involvement may occur, we have a low threshold to refer ATTRv patients with any suspicion for neurologic involvement for formal assessment.

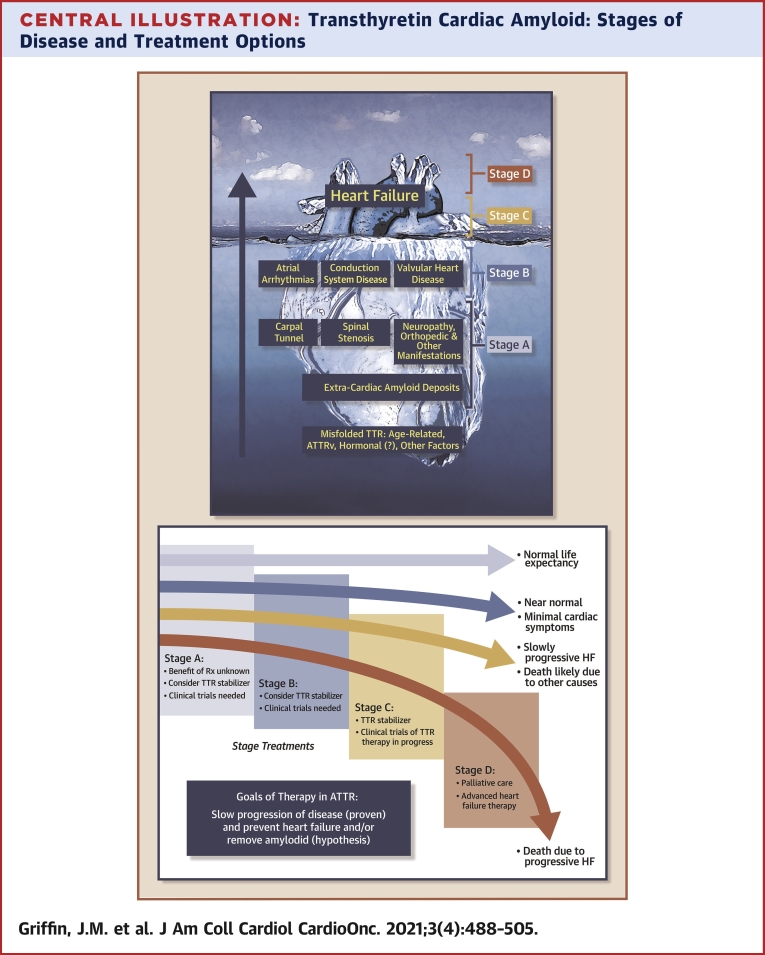

For ATTR-CA patients with progressive HF, studies have shown that symptoms may be driven by reduced myocardial reserve as estimated by means of semisupine exercise test (21) and echocardiography (22). Aligning with this concept that patients with advanced disease have lower stroke volume, the potential utility of inotropes may arise. In a single-center study from France, mortality was high in patients with cardiac amyloidosis admitted to the intensive care unit for cardiogenic shock, particularly in those receiving catecholamine infusions (23). However, this may represent treatment bias for those with end-stage disease rather than a causal relationship between inotropic support and mortality. Overall, there are insufficient data to guide the use of inotropes in ATTR-CA. The clinical progression and management strategies of ATTR-CA (including targeted therapies discussed below) are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Clinical Status and Treatment for ATTR-CA

Progression from preclinical to end-stage heart failure (HF) with progressive symptoms from dyspnea and arrhythmias to a low output state. ? = unknown benefit.

Management of arrhythmias associated with ATTR-CA

Arrhythmias in ATTR-CA span the spectrum from bradyarrhythmias to atrial and ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Most of the published literature contain data on combined cohorts of light chain amyloid (AL) and ATTR patients, making it difficult to ascertain specific details for ATTR-CA.

Atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most frequent sustained arrhythmia encountered in those with ATTR-CA. Reported prevalence is highly variable, ranging from 15% to 70% across all CA subtypes (24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29). AF is more common in ATTRwt than in AL-CA or ATTRv, with a prevalence as high as 70% reported in some series (26).

Owing to the high prevalence of AF, screening with long-term monitoring should be considered in ATTR-CA. The detection of AF modifies treatment because anticoagulation is essential owing to high prevalence of intracardiac thrombus. In a study of 58 CA patients (50% with ATTR-CA) referred for transesophageal echocardiography (TEE)–guided direct current cardioversion (DCCV) for atrial arrhythmias, 16 (28%) were cancelled of which 13 demonstrated intracardiac thrombus (7 ATTRwt), including 2 with AF after <48 hours and 4 with a therapeutic international normalized ratio at ≥3 weeks. In 21 ATTR-CA patients with TEE data, 65% showed spontaneous contrast on echocardiography and 33% had intracardiac thrombus (30). In a separate study of 100 ATTR-CA patients who underwent TEE before planned DCCV, left atrial appendage thrombus was seen in 30%, of whom 87% were on systemic anticoagulation. In addition, there was no association between the CHA2DS2-VASc risk score and presence of intracardiac thrombus (31). Based on these findings, the use of anticoagulation in all ATTR-CA patients with AF regardless of CHA2DS2-VASc risk score is recommended along with TEE-guided DCCV regardless of anticoagulation status.

There are insufficient data to inform whether vitamin K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants are preferred for oral anticoagulation. The role of left atrial appendage occlusion devices in ATTR-CA is unknown, but there is concern for potential device thrombosis given the known increased risk of intracardiac thrombus.

Rate control can be challenging in ATTR-CA because of a narrow range of heart rate to optimize hemodynamics given the likely presence of a low and relatively fixed stroke volume. Nevertheless, cautious beta-blocker use is reasonable for persistent AF. Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers should be avoided in CA (11,32) owing to concerns for amyloid fibril binding, negative inotropic effect, blunting of heart rate response, and risk of hypotension. When necessary, these agents should be started at low doses with frequent monitoring (26).

The role of digoxin in the management of CA remains controversial. Historically, there were concerns for digoxin binding with amyloid fibrils leading to increased risk for toxicity in AL (33). However, a contemporary, retrospective study evaluated digoxin use in 69 patients with cardiac amyloidosis, 42 of whom had ATTR-CA; digoxin-related toxicity or arrhythmias occurred in 15.9%, with no deaths attributed to digoxin toxicity (34). Thus, low-dose digoxin with close monitoring is a reasonable alternative for rate control, especially in patients prone to hypotension.

A rhythm control strategy may be considered, particularly for earlier stage disease. In a nonrandomized study of ATTRwt patients with AF, 32.3% received antiarrhythmic therapy and the remainder were managed with rate control. The most common antiarrhythmic agent was amiodarone. There was no difference in survival among patients treated with rate versus rhythm control (28). A recent study assessed outcomes in 265 patients with ATTR-CA and AF. In that cohort, 35% received antiarrhythmic medications, 45% underwent DCCV, and 5% underwent AF ablation. Rhythm control strategies appeared more effective when used earlier in the disease course. In addition, there was no difference in survival for ATTR-CA patients with or without AF (35).

TEE-guided DCCV may be considered in ATTR-CA patients with symptomatic AF. In a single-center study, success rates were similar between those with CA and control subjects. However, ventricular arrhythmias and bradyarrhythmias were more common in the CA group. The rates of arrhythmia recurrence during 1-year follow-up were similar for control subjects without CA (55%), patients with AL-cardiomyopathy (50%), and patients with ATTR-CA (49%) (30). In a separate study of 283 patients (52% ATTR-CA), 32% underwent DCCV with a 1-year recurrence rate of 71% in those with ATTR-CA (29). Thus, while immediate success rates in ATTR-CA are similar to other cohorts, the 1-year recurrence is high.

Published data regarding catheter ablation for AF in CA remains limited. A study of 24 patients with ATTR-CA who underwent AF ablation appeared matched 2:1 to ATTR-CA patients with AF treated medically. During a mean follow-up of 39 months, the overall recurrence rate of AF was 58%. Ablation appeared more effective in those with earlier-stage disease (36).

In our clinical experience, long-term maintenance of sinus rhythm is difficult in most patients with intermediate-late stage ATTR-CA, and recurrent atrial arrhythmias often herald more severe disease. Advances in treatment of ATTR-CA may lead to more success with rhythm control.

Bradyarrhythmia

Conduction disease is commonly encountered in ATTR-CA. Barbhaiya et al (37) performed electrophysiologic studies on 18 advanced CA patients (14 ATTRwt) and found that the His-ventricular (HV) interval was prolonged (>55 ms) in all CA patients, including in 6 patients with normal QRS duration (≤100 ms), which is consistent with extensive conduction disease. Thus, HV interval prolongation with normal QRS duration may be driven by widespread involvement of both left and right bundle branches in CA patients. In a single-center study in France, 100 patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy (ATTRv) underwent prophylactic pacemaker implantation after meeting criteria of HV interval >70 ms, HV interval >55 ms associated with a fascicular block, first-degree atrioventricular block, or a Wenckebach anterograde point ≤100 beats/min. During mean follow-up of 45 months, 25% developed second- or third-degree atrioventricular block (38) requiring permanent pacing. Whether this is applicable to ATTRv with predominant cardiac phenotype or ATTRwt has not been studied.

Standard indications for pacing are recommended in patients with ATTRwt, although some centers with endemic populations of ATTRv consider prophylactic pacing when conduction abnormalities are detected. For those that meet criteria for pacing, the use of biventricular pacing (cardiac resynchronization [CRT]) may be considered, but its benefits are uncertain. A retrospective cohort study of 78 patients with ATTR-CA found that patients with RV pacing burden >40% had more mitral regurgitation, lower LVEF, worsening New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, and greater mortality compared with those with RV pacing <40%. In the same study, CRT was associated with higher LVEF and NYHA functional class and lower mitral regurgitation severity (39). A follow-up study matched 30 ATTR-CA patients who underwent CRT implantation to 30 patients that did not receive CRT, including on NYHA functional class, LVEF, and ATTR-CA stage. CRT was associated with better HF symptoms, LVEF, and survival (40). CRT may be of benefit in ATTR-CA patients with an indication for pacing, particularly in those with a high pacing burden.

Ventricular arrhythmias

Ventricular arrhythmias, especially asymptomatic nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, are commonly detected in ATTR-CA. Sudden cardiac death in ATTR-CA is thought to be uncommon, especially compared with AL-CA, but prospective studies are lacking. Although a number of studies (including both AL- and ATTR-CA) have shown appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) use in CA patients, none have shown greater survival compared with CA patients without ICDs (26,41, 42, 43, 44, 45). The incidence of appropriate ICD use varied from 6% to 32%, although the duration of follow-up and composition of the cohort in each study was heterogeneous (26). Overall, the utility of primary-prevention ICDs in ATTR-CA remains controversial. The 2015 European Society of Cardiology guidelines state that there are insufficient data to provide recommendations for the use of ICDs for primary prevention in CA (46). The 2017 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines recommend individualized decision making for both primary and secondary prevention with ICDs in CA (47). Despite incremental data on ICDs in CA since publication of these guidelines (41,45), the benefit of ICDs in ATTR-CA remains unclear.

Valvular Heart Disease and ATTR-CA

Calcific aortic stenosis (AS) is common in older adults, with an incidence of ∼4% in individuals over 70 years of age (48). Therefore, it is not surprising that the dual pathology of ATTRwt and aortic stenosis frequently coexist. Approximately 15% of patients with AS undergoing TAVR have a nuclear cardiac scintigraphy study consistent with ATTR-CA (5,49, 50, 51, 52). Patients with concurrent severe AS and ATTR-CA tend to be older, are more frequently male, and exhibit the following echocardiographic features: increased interventricular septal wall thickness, low flow–low gradient AS, mildly reduced LVEF, and lower stroke volume index, with a history of carpal tunnel syndrome (5,51,53,54).

Emerging data suggest that TAVR is preferred to surgical AVR in patients with concomitant ATTR-CA and AS, observations which may be related to greater risk associated with ATTR-CA (55,56). Surgical and percutaneous data are limited in ATTR-CA, although several studies have demonstrated that TAVR has acceptable outcomes and should not be withheld for this patient population (5,49,57,58).

Studies suggest that aortic valve intervention is likely superior for preventing death compared with medical therapy, but data regarding reducing morbidity remain limited. A recent European multisite prospective study assessing 200 patients with severe AS (13% with CA) demonstrated no significant difference in mortality between lone AS and patients with dual phenotype over a median follow-up of 19 months. Compared with medical therapy, TAVR was associated with a significant survival benefit in both the total cohort and the ATTR-CA subgroup (58). Similar findings were demonstrated by Nitsche et al, who also found that TAVR was associated with better survival compared with medical therapy (5). It is worth noting, however, that there was a nearly 2-fold greater risk of mortality over a median follow-up of 1.7 years (24.5% vs 13.9%; P = 0.05) in patients with CA compared with severe AS alone, whether treated with TAVR or with medical therapy (5). CA was associated with greater risk for HF hospitalizations after the procedure (49). Whether emerging therapies for ATTR-CA can be leveraged to alter the natural history of disease in the setting of AVR is unknown and an area of significant interest.

Surgical and interventional data regarding mitral and tricuspid valve disease in CA are limited. A single-center study including ∼7,700 individuals undergoing isolated or combined mitral valve surgery from 2007 to 2016 detected amyloid in <1% of removed tissue (n = 15: 14 ATTRwt and 1 ATTRv) (59). A small single-center case series in patients with CA and moderate-to-severe or severe mitral regurgitation compared outcomes of percutaneous mitral valve repair (PMVR) versus conservative therapy. The PMVR arm included 4 ATTR and 1 AL patient and the conservative therapy arm included 2 ATTR and 5 AL patients. The study demonstrated the technical feasibility of percutaneous intervention in this complex cohort of carefully selected CA patients without any untoward effects on prognosis (60). Data concerning tricuspid intervention in ATTR-CA are lacking. Given the predominance of right heart dysfunction in ATTR-CA, the utility of intervention for tricuspid valve regurgitation is questionable because tricuspid regurgitation is frequently secondary to RV remodeling rather than a primary valve process (61).

Management of Carriers of Pathogenic TTR Alleles

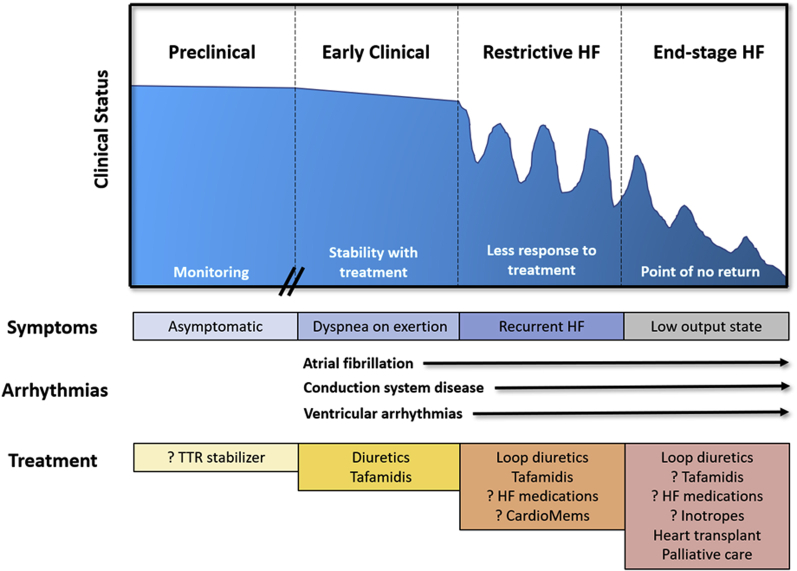

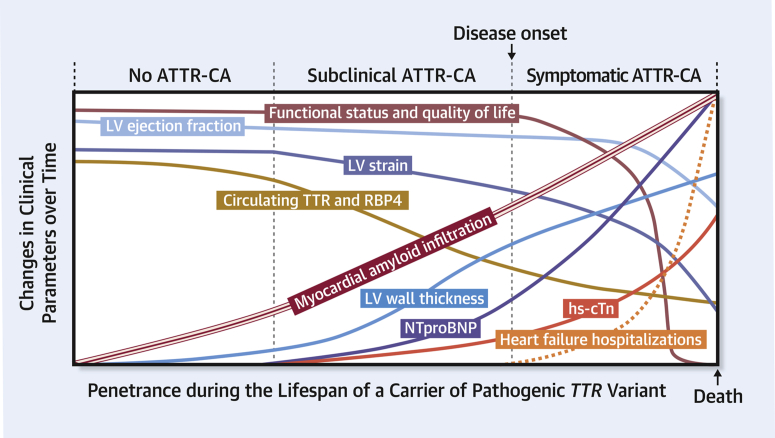

There is a critical unmet need to better understand the presymptomatic disease trajectory before the onset of clinical ATTR-CA. Unfortunately, there are no established imaging- or biomarker-based screening criteria to determine whether there is CA involvement in asymptomatic TTR mutation carriers. The proposed natural history of penetrance described here for carriers of pathogenic TTR alleles is shown in Figure 2. The p.V142I mutation is the most common cause of hereditary ATTR-CA worldwide (62). Estimates suggest that p.V142I ATTR-CA may constitute ∼23% of all ATTR-CA cases in the United States, and data from population-based cohort studies suggest that 3%-4% of individuals with African ancestry carry the p.V142I TTR variant (62, 63, 64). Therefore, given this variant’s relatively high prevalence in the general population (∼1.5 million carriers in the United States), observations from p.V142I TTR carriers enrolled in epidemiologic cohorts have provided clues for subclinical ATTR-CA phenotypes.

Figure 2.

Proposed Natural History of Penetrance in Carriers of Pathogenic TTR Variants

ATTR-CA = transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis; hs-cTn = high sensitivity cardiac troponin; LV = left ventricular; NTproBNP = N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; RBP4 = retinol-binding protein 4; TTR = transthyretin.

The clinical penetrance of pathogenic alleles is not 100%. Data from the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities) (n/N = 124/3,732) and the Cardiovascular Health Studies cohorts highlight that black p.V142I TTR carriers at a median age of 52 years (n/N = 124/3,732) are at ∼45% higher life-time risk of developing HF (pooled hazard ratio [HR]: 1.45; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.04-2.02) than race-matched noncarriers (median age: 53 years) (65). Clinical penetrance is age dependent, and HF commonly manifests after the 7th and 8th decades of life (63,66). However, it is very likely that carriers of pathogenic TTR variants manifest with subclinical forms of the disease at a much younger age. For example, a subset of the ARIC population had a detailed echocardiography assessment 22-26 years after enrollment (when participants were ∼70 years old). Compared with noncarriers (n = 1,187), p.V142I TTR carriers (n = 46) had greater posterior LV wall thickness, relative wall LV thickness, E/A ratio, E/e′, and abnormal global longitudinal strain (63). Only a minority of those p.V142I TTR carriers had a mean LV wall thickness >1.2 cm. The implications of this analysis from ARIC were 2-fold: 1) that p.V142I TTR carriers may manifest with subtle cardiac abnormalities; and 2) that echocardiography with strain-based imaging may be a useful tool to follow the development of ATTR-CA phenotypic penetrance over time.

Observations from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) cohort further support the presence of a subclinical ATTR-CA phenotype among p.V142I TTR carriers and extend observations from ARIC to carriers in midlife (67). At a mean age of 54 years (n = 24), p.V142I TTR carriers, compared with race-matched noncarriers (n = 648), had lower absolute LV systolic circumferential strain and greater LV mass indexed to body surface area (67).

A key limitation of these observations from ARIC and CARDIA is the lack of certainty that these subtle cardiac abnormalities observed in p.V142I TTR carriers by echocardiography were mediated by amyloid infiltration. There were no amyloid-specific diagnostic modalities, such as tissue biopsy, contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with parametric mapping, or bone scintigraphy, used in these protocols. Data supporting the use of technetium-based cardiac imaging for screening in carriers of abnormal TTR alleles are limited. In a single-center retrospective study of 40 patients undergoing technetium-99m pyrophosphate (PYP) imaging to evaluate for ATTR-CA, there were 12 asymptomatic carriers of pathogenic TTR variants (age: 51 ± 15 years) (68). Despite relatively low B-type natriuretic peptide levels (15 [interquartile range: 10-37] pg/mL) and normal interventricular septal thickness according to echocardiography (0.9 ± 0.3 cm), 10 of these asymptomatic carriers had myocardial uptake (Perugini scale 1, 2, or 3) and an average heart/contralateral lung ratio of 1.5 ± 0.4. Data from this study support the hypothesis that PYP scans can detect subclinical ATTR-CA. However, there were 2 important limitations of this study: 1) It is unclear if myocardial uptake was confirmed by single-photon emission computed tomography (69); and 2) the timing between imaging acquisition and radionuclide injection was not specified. Similar findings have been observed with the use of other bone radiotracers (70). However, the utility of bone scintigraphy to detect subclinical ATTR-CA remains in question. More information is warranted before justifying its use, and it remains unclear as to what degree of myocardial amyloid infiltration will translate to radionuclide uptake.

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging may be an attractive option to detect and quantify myocardial amyloid infiltration from subclinical ATTR-CA owing to its high-quality images and tissue characterization capabilities. Contrast-enhanced CMR imaging shows a characteristic diffuse or patchy pattern of subendocardial late gadolinium enhancement and may be detectable in a portion of carriers of pathogenic TTR variants in the absence of LV thickening. In addition, native T1 mapping and extracellular volume measurements provide incremental diagnostic information. Altogether, these 3 CMR techniques have acceptable diagnostic performance estimates (∼80%-93% sensitivity and specificity) to diagnose CA in individuals with a reasonable index of suspicion for the disease (71). However, their utility in diagnosing subclinical ATTR-CA has not been systematically studied. Whether ventricular or atrial strain and strain rates measured from cine CMR images using feature tracking software are helpful or not is unknown (72,73).

Common cardiac biomarkers associated with the development of HF in the general population, such as cardiac troponin (cTn) and N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), do not distinguish asymptomatic carriers of pathogenic TTR variants from noncarriers well (63). Although both biomarkers are elevated in clinical ATTR-CA and may increase over time (63,74), cTn and NT-proBNP may be in the normal range in asymptomatic carriers, with limited utility for identifying subclinical ATTR-CA.

Transthyretin-specific biomarkers, such as circulating TTR and retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4), may be more promising alternatives to cTn and NT-proBNP. Circulating TTR levels, for example, parallel TTR kinetic stability and are indicative of amyloidogenesis. In a small study, 47 p.V50M TTR carriers had plasma levels of TTR measured and compared with noncarriers (75). The p.V50M TTR carriers had significantly lower average TTR levels than noncarriers (16.8 vs 22.0 mg/dL; P = 0.005). Retinol-RBP4 complexes bind to TTR and stabilize the tetramer, preventing TTR disassembly and amyloidogenesis (76). However, whether circulating RBP4 provides incremental diagnostic insight to uncover subclinical ATTR-CA is unknown.

A portion of individuals with ATTR-CA will have comorbid amyloid polyneuropathy. As such, plasma neurofilament light chains (NfL), markers of neuroaxonal injury that can detect the onset of clinical neuropathy before the emergence of significant clinical disability, may be useful biomarkers. In a recent study (77), plasma NfL levels were higher in individuals with pathogenic TTR alleles compared with control subjects and correlated with the degree of clinical neuropathy impairment. Whether plasma NfL levels are a useful biomarker beyond detecting neuropathy to identify ATTR-CA development for individuals with a more predominant cardiac phenotype is unknown.

The status quo as it pertains to the timing of screening carriers for subclinical ATTR-CA is to establish the predicted age of onset of symptomatic disease, as recommended by a recent consensus task force composed of a group of TTR amyloid experts. That age is estimated from the typical age of onset for ATTR-CA and the age of onset from family members with ATTR-CA. Once determined, this task force recommended monitoring 10 years before this date (78). These recommendations may be more pertinent for age-similar siblings of a proband, who are at higher risk for developing ATTR-CA than children. However, many questions remain, and these recommendations need validation. Genetic testing has the capacity to identify TTR variant carriers in the prepenetrant phase with the potential to identify at-risk individuals. Such a strategy would have the capacity to mitigate undiagnosed ATTR-CA in p.V142I TTR carriers (79). Nevertheless, the follow-up diagnostic testing strategies and their frequencies to monitor subclinical disease progression need clarification (Table 2). Furthermore, whether contemporary ATTR-CA therapies are beneficial and cost-effective in treating subclinical ATTR- CA needs to be delineated.

Table 2.

Cardiac Modalities for Assessing Progression in ATTR Cardiomyopathy

| Testing Modality | Strengths | Weaknesses | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum biomarkers |

|

|

|

| Electrocardiography (ECG) |

|

|

|

| Holter monitoring |

|

||

| Echocardiography |

|

|

|

| Nuclear pyrophosphate (PYP) scan |

|

|

|

| Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging |

|

|

|

| Cardiac positron-emission tomography |

|

|

|

AL = light-chain amyloid; ATTR = transthyretin amyloid; ATTRv = variant transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis; ATTRwt = wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis; CA = cardiac amyloidosis; H/CL = heart/contralateral; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; TTR = transthyretin.

Treatment Strategies and Specific Disease-Modifying Therapeutics

There are currently 2 main therapeutic strategies that have shown to be effective for the treatment of ATTR-CA: 1) stabilizing the TTR protein by targeting the rate-limiting step of TTR degradation; and 2) silencing the production of TTR. In addition, there are several agents in the early stages of development, such as extractors/degraders, antiseeding therapies, and inhibitors of TTR aggregation.

Transthyretin stabilization

Diflunisal is a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agent with TTR stabilizing properties. It acts by binding to the T4-binding sites at the dimer-dimer interface on the transthyretin tetramer, thus preventing the rate-limiting dissociation of TTR and subsequent misfolding into amyloidogenic monomers and oligomers. Diflunisal is associated with adverse effects including gastrointestinal hemorrhage, renal dysfunction, fluid retention, and hypertension. However, given that the dose used for the treatment of ATTR-CA (250 mg twice daily) is lower than that recommended for antiinflammatory activity, it is often well tolerated. In a study of 130 patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy who were randomized to 250 mg diflunisal twice daily or placebo for 2 years, diflunisal reduced the rate of progression of polyneuropathy (neuropathy impairment score plus 7 increased by 8.7 vs 25.0 points for diflunisal vs placebo, respectively; P < 0.001) and preserved quality of life (80). Furthermore, it appears to have therapeutic benefit in slowing the progression of ATTR-CA in stable HF patients (81). Treatment with diflunisal should include regular monitoring of renal function and clinical evaluation for worsening HF symptoms and gastrointestinal bleeding.

Tafamidis (Vyndamax/Vyndaqel, Pfizer) is an orally bioavailable benzoxazole derivative that, similar to diflunisal, stabilizes the TTR tetramer by binding to the T4-binding sites but lacks nonsteroidal antiinflammatory activity. The ATTR-ACT (Safety and Efficacy of Tafamidis in Patients With Transthyretin Cardiomyopathy) trial was a randomized double-blind study that enrolled 441 subjects to 80 mg or 20 mg tafamidis or placebo daily (82). The trial demonstrated an absolute reduction of 13.4% in all-cause mortality in the pooled tafamidis cohort compared with placebo (29.5% vs 42.9%) and a 32% lower risk of cardiovascular hospitalizations for NYHA functional class I or II HF by 30 months. However, those with NYHA functional class III HF symptoms had higher rates of cardiovascular hospitalizations with tafamidis compared with placebo, reinforcing the necessity of early diagnosis and treatment. Secondary end points demonstrated a reduction of the decline in 6-minute walk test (6MWT) distance and a lower rate of decline in quality of life as assessed by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire. Subsequent analysis of the ATTR-ACT trial found that reduction in all-cause mortality was greater for 80 mg tafamidis than for the 20 mg dose, compared with placebo, without dose-related safety concerns, leading to it becoming the preferred dosing option (83). In May 2019, tafamidis became the first ATTR-CA therapy to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of ATTR-CA. It is available as tafamidis meglumine 20 mg capsules (dose 80 mg daily) and tafamidis 61 mg free acid capsules, the latter developed for patient convenience. These 2 formulations are bioequivalent though not substitutable on a per mg basis (84).

Acoramidis (AG10, Eidos Therapeutics) mimics the structural stabilizing properties of the TTR variant p.T139M. This highly stabilizing variant protects against the development of familial amyloid polyneuropathy in those heterozygous for the disease-causing p.V50M variant (85) by slowing the dissociation of TTR tetramers. The p.T139M mutation stabilizes the TTR tetramer by forming hydrogen bonds between neighboring serine residues at position 137 of each monomer and reduces the dissociation of TTR ∼40-fold compared with ATTRwt (86). The potency and selectivity of acoramidis appears to exceed that of tafamidis and diflunisal, as shown by Penchala et al (87): 1) Acoramidis binds more selectively to serum TTR than diflunisal, tafamidis, or TTR’s natural ligand, T4; 2) it appears to provide enhanced stabilization of TTR over tafamidis; and 3) in contrast to tafamidis, it kinetically stabilizes TTR tetramers of the variant p.V142I equally well as wild-type TTR. In a phase 2 study, there was near complete stabilization of TTR at peak and trough serum acoramidis levels (>90%) and a >50% increase in serum TTR levels at 28 days in those taking 800 mg acoramidis twice daily vs placebo (88). The Eidos AG10 study (ATTRIBUTE-CM) is a phase 3 trial with a planned enrollment of 510 subjects with ATTR-CA in a 2:1 ratio to 800 mg acoramidis or placebo twice daily for 30 months (NCT03860935). The co-primary end points are change in 6MWT distance at 12 months and all-cause mortality and frequency of cardiovascular-related hospitalizations over a 30-month period.

Silencing TTR production

Silencing of the TTR protein is facilitated by 2 treatments: 1) antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs); and 2) small interfering RNA molecules (siRNA). ASOs are single-stranded amphipathic molecules that are broadly distributed in the body after administration and bind to proteins in the serum, on the cell surface, and within cells. Within the nucleus of the target cell, the ASO binds to target mRNA and via the endonuclease, RNase H2, initiates mRNA degradation (89). siRNAs are double-stranded oligonucleotides containing sense and antisense strands, the former acting as a drug delivery device and the latter being the active moiety. They are polyanionic and hydrophilic and as such require formulation in lipid nanoparticles or conjugation to delivery systems for effective tissue delivery. Once within the cytoplasm, the antisense strand is loaded onto Ago2, creating a complex that then binds to the target mRNA to form the RNA-induced silencing complex with subsequent degradation of the mRNA (89). Given that the main function of TTR is to transport retinol, vitamin A supplementation must be taken by those receiving silencer therapy. However, serum levels of vitamin A in patients on silencer therapy do not reflect total body stores and should not be used to adjust the supplement dosage.

First-generation agents

Inotersen (Tegsedi, Akcea Therapeutics) is a 2′-O-methoxyethyl-modified phosphorothioate ASO. The 2′-phosphorothioate modification enhances nuclease resistance and protein binding, thus enhancing the potency and pharmacokinetic properties of inotersen (90). In the NEURO-TTR (Efficacy and Safety of Inotersen in Familial Amyloid Polyneuropathy) trial (NCT01737398), 300 mg inotersen once weekly via subcutaneous injection stabilized neuropathy and quality of life in patients with ATTRv with polyneuropathy with or without cardiac involvement (91). However, serious adverse events included glomerulonephritis in 3%, severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count <25 × 103/μL) in 3%, and 1 death due to intracranial hemorrhage. In the open-label extension (OLE) (NCT02175004), with enhanced monitoring, 29.4% of the inotersen-inotersen group and 46% (23/50) of the placebo-inotersen group experienced thrombocytopenia to <100 × 103/μL (92). There were no cases of platelet counts <25 × 103/μL or acute glomerulonephritis in the OLE. A single-center study of 33 patients with NYHA functional class I-III ATTR-CA treated with inotersen, showed improvement in mean LV mass on CMR imaging (−8.4%) and increase in exercise tolerance as measured by 6MWT (+20.2 m) at 2 years (93). Although inotersen remains commercially available, it is no longer being studied in clinical trials for ATTR-CA owing to the development of longer-acting ASOs with more favorable side-effect profiles.

Patisiran (Onpattro, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals) is an siRNA formulated as a lipid nanoparticle to facilitate hepatic uptake. The ALN-TTR02 (Study of an Investigational Drug, Patisiran), for the APOLLO (Treatment of Transthyretin [TTR]–Mediated Amyloidosis) phase 3 trial randomized 225 patients with ATTR familial amyloid polyneuropathies and NYHA functional class I-II 2:1 to receive patisiran (0.3 mg/kg every 3 weeks) or placebo (94). At 18 months, progression of neuropathy was halted or reversed in the patisiran group. Furthermore, in the predefined cardiac subpopulation (n = 126), defined as baseline LV wall thickness ≥13 mm and no history of hypertension or aortic valve disease, patisiran reduced mean LV wall thickness, decreased global longitudinal strain (−1.4%), and lowered NT-proBNP at 18 months (95). A post hoc analysis of APOLLO demonstrated a reduction of 46% in cardiac hospitalizations and all-cause mortality in those randomized to patisiran compared with placebo. Further evidence that patisiran may play a role in regression of ATTR cardiac amyloid burden was provided by Fontana et al (96). In that study of 16 patients with ATTRv who received patisiran with or without diflunisal, patisiran was associated with a reduction in extracellular volume on CMR by a mean difference of 6.2% at 12 months compared with untreated historical controls, although there was a considerable variation between subjects. The APOLLO-B (Study to Evaluate Patisiran in Participants With Transthyretin Amyloidosis With Cardiomyopathy; NCT03997383) is a phase 3 trial with a targeted enrollment of 300 patients with ATTR-CA (excluding NHYA functional class IV) randomized 1:1 to patisiran or placebo. The study consists of a 12-month double-blind placebo-controlled period, followed by a 12-month open-label period in which all participants will receive patisiran. The primary outcome is change from baseline at month 12 in the 6MWT. All study subjects must be premedicated with acetaminophen, dexamethasone, and H1- and H2-antagonists before infusion owing to the proinflammatory nature of the lipid nanoparticle delivery system.

Second-generation agents

Vutrisiran (ALN-TTRSCO2, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals) is a second-generation siRNA that, in contrast to patisiran, is conjugated to N-acetyl galactosamine (GalNAc). GalNAc has a high affinity for the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR), which is found in high concentrations on hepatocytes, thus targeting the liver for uptake. It is administered as a 25 mg subcutaneous injection every 3 months and, because there is no lipid nanoparticle in the formulation, premedication is not required. In a phase 1 study, vutrisiran caused a reduction in TTR levels of 83% at 6 weeks, which was sustained for 90 days (95). HELIOS-B (A Study to Evaluate Vutrisiran in Patients With Transthyretin Amyloidosis With Cardiomyopathy; NCT04153149) is a phase 3 clinical trial of ∼600 patients with NYHA functional class I-III ATTR-CA randomized 1:1 to vutrisiran or placebo. A subset of patients enrolled in this trial will be permitted to concurrently take the TTR stabilizer tafamidis. The study duration will be 30-36 months with a composite primary end point of all-cause mortality and recurrent cardiovascular events.

AKCEA-TTR-LRx (ION 682884, Akcea Therapeutics) is a ligand (conjugated to GalNAc)–conjugated ASO, targeted to the ASGPR on hepatocytes. Thus, ION-682884 has enhanced liver uptake over its predecessor, inotersen, with which it shares the same base sequence. Phase 1 studies (NCT03728634) demonstrated a 51-fold greater potency and 27-fold lower exposure at a dose of 45 mg monthly via subcutaneous injection, achieving an 85.7% mean reduction in plasma TTR levels without the problematic adverse effects of inotersen (97). Cardio-TTRansform (A Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of AKCEA-TTR-LRx in Participants With Transthyretin-Mediated Amyloid Cardiomyopathy; NCT04136171) is a phase 3 trial in which 750 patients with ATTR-CA will be randomized 1:1 to ION-682884 monthly or placebo every 4 weeks. The primary end point will be a composite of cardiovascular mortality and recurrent cardiovascular clinical events at 120 weeks, with frequent clinical monitoring.

Novel Approach to TTR Knockdown

CRISPR stands for clusters of regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, and Cas9 is CRISPR-associated protein 9. CRISPR-Cas9 is a gene-editing approach in which target DNA can be permanently modified or repaired. This technology consists of 2 components, a Cas9 protein that recognizes the target DNA and performs double-strand cleavage and a guide RNA that directs the Cas9 protein to a specific target DNA sequence. This process results in: 1) induction of the cell’s natural repair process to correct the mutation; and 2) deletion of the mutation- (nonhomologous end joining) or homology-directed repair via the RNA template provided. NTLA-2001 (Intellia Therapeutics, Cambridge, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals), an intravenous infusion, is being evaluated in a phase 1 study in patients with hereditary ATTR with polyneuropathy (NCT04601051). NTLA-2001 uses a lipid nanoparticle to deliver guide RNA and messenger RNA encoding the Cas9 protein with the aim of producing a single administration curative treatment for ATTR. Animal data demonstrated that a single dose of NTLA-2001 achieved >97% knockdown in mouse TTR protein at 12 months (98).

Amyloid Extraction/Degradation

PRX-004 (Prothena Biosciences) is an intravenous monoclonal antibody that binds to misfolded TTR amyloid but not to native circulating TTR, thus clearing amyloid deposits in the myocardium. In a phase 1 study of 21 patients with ATTRv (excluding NHYA functional class III-IV), PRX-004 was found to be safe and well tolerated without serious adverse events (NCT03336580) (99). In the 7 patients who received 9 months of therapy, there was improvement in global longitudinal strain of 1.2% from baseline.

NI006 (Neurimmune) is a recombinant IgG1 human monoclonal antibody that targets misfolded and aggregated forms of both ATTRwt and ATTRv. A first-in-human study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of NI006 in patients with ATTR-CA is currently enrolling (NCT04360434).

Serum amyloid P component (SAP) is a nonfibrillar plasma glycoprotein formed in the liver that binds to all amyloid fibril types. Based on this, SAP has become a target for clearance of amyloid deposits. Bodin et al demonstrated that the administration of IgG anti-SAP antibody in mice containing human SAP resulted in a complement dependent, phagocytic clearance of amyloid deposits (100). When administered following a small-molecule drug, (R)-1-[6-[(R)-2-carboxy-pyrrolidin-1-yl]-6-oxo-hexanoyl]pyrrolidine-2-carboxylic acid (CPHPC), that reduces circulating SAP by over 90%, anti-SAP antibody targets and clears residual amyloid deposits (100). A phase 1 study in which patients received CPHPC followed by IgG anti-SAP antibody showed a reduction in liver stiffness and decrease in renal amyloid load at 6 weeks; however, those with cardiac involvement were excluded (NCT01777243) (101). A phase 2 study of the anti-SAP antibody dezamizumab failed to show an improvement in cardiac amyloid burden in ATTR-CA (NCT03044353) and is no longer under investigation owing to the unfavorable risk-benefit profile.

Other Emerging Therapies

Amyloid seeding refers to the deposition of native transthyretin onto preformed amyloid fibrils in the organ and soft tissues. As such, despite the use of TTR stabilizing therapy, seeding of native tetramers may continue in the presence of significant amyloid burden. TabFH2 is a peptide inhibitor that caps the tips of the F and H beta-strands, the primary drivers of fibril aggregation (102), thereby inhibiting self-association and seeding. Although this remains an experimental therapy, it could play a role in the treatment of patients with significant cardiac amyloid burden, thus preventing further deposition.

Other Agents

Doxycycline has been found to disrupt TTR fibrils in transgenic mice, resulting in a reduction in amyloid associated markers such as SAP and matrix metalloproteinase 9. Ursodiol and its taurine conjugate, taursodeoxycholic acid, are effective in lowering nonfibrillar TTR and have been found to act synergistically with doxycycline. Several small studies of these agents in ATTR-CA have found no demonstrable benefit, and there is a high rate of discontinuation of therapy owing to gastrointestinal and dermatologic side-effects (103,104).

Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) is a catechin found in green tea that has been shown to inhibit fibril formation in ATTRv in nonhuman animal studies. In a single-center study of 19 patients with ATTR-CA who consumed 500-700 mg EGCG daily for 12 months, there was no progression of disease, as shown by a mean decrease in LV myocardial mass of 12.5% and an increase in mean mitral annular velocity of 9%, in 14 of those available for follow-up, suggestive of an inhibitory effect on progression of CA (105). Others have suggested similar but modest change in cardiac parameters, though notably all were single-arm small studies (106).

Curcumin appears to have neuroprotective effects in ATTR, acting as a TTR stabilizer at the T4-binding site. In mouse models with human TTR p.V50M, chronic administration of curcumin resulted in reduction of tetramer dissociation and inhibited aggregation of amyloid fibrils (107). Curcumin also appears to trigger disaggregation of amyloid fibrils and promote clearance (107). The short half-life and limited tolerability of curcumin at high doses make it unsuitable for therapeutic use; however, novel formulations with greater bioavailability are being developed.

Cost of Therapy

Although the emergence of ATTR-targeted therapies has resulted in significant improvement in morbidity and mortality, the cost of these novel agents must be taken into consideration (Table 3). The annual cost of tafamidis is $225,000/year, making it the most expensive cardiovascular drug on the market in the U.S. A cost-effectiveness analysis, showed that a 92.6% reduction of list price (to $16,563/year) would be required to make tafamidis cost-effective (108). This study also estimated that annual U.S. health care costs could increase by $32.3 billion if all those with ATTR-CA are treated with tafamidis (108). Unfortunately, the high cost of these novel agents creates a barrier to care and makes them inaccessible to many already disadvantaged patients (108,109).

Table 3.

Therapies for the Treatment of Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis

| Drug | Phase of Study | Mechanism | Dose/Route | Monitoring | Side effects | Efficacy/Primary Outcomes | Annual List Price |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stabilizers | |||||||

| Diflunisal | Phase 2/3 | Binds to T4-binding site | 250 mg oral twice daily | CBC and BMP every 3 mo | 1) Renal dysfunction; 2) Bleeding; 3) Hypertension; 4) Fluid retention | Safety and efficacy | $420 |

| Tafamidis meglumine (Vyndaqel); Tafamidis free acid (Vyndamax) |

Approved for ATTRwt and ATTRv | Benzoxazole derivative of NSAID, binds to T4-binding site on TTR | 80 mg (4 × 20 mg) oral daily (Vyndaqel); 61 mg oral daily (Vyndamax) |

No monitoring required | No known side-effects or interactions | Tafamidis superior to placebo: 1) lower all-cause mortality (29.5% vs 42.9%); NNT: 7.5; 2) lower CV-related hospitalizations; NNT: 4 | $225,000 |

| Acoramidis/AG10 | Phase 3 in ATTRwt and ATTRv (ATTRIBUTE-CM; NCT03860935) | Forms hydrogen bonds between neighboring serine residues at position 117 of each monomer, mimicking activity of Thr119Met | 800 mg oral twice daily | TBD | No known side-effects or interactions | 1) Change in 6MWT at 12 mo; 2) all-cause mortality and CV-related hospitalizations at 30 mo | TBD |

| Knockdown/silencing TTR | |||||||

| Inotersen (Tegsedi) | Phase 2 (NCT03702829); not being pursued for ATTR-CA | 2′-O-methoxyethyl-modified phosphorothioate antisense ASO, binds to target mRNA in liver and initiates mRNA degradation | 300 mg SC once weekly, plus 3,000 IU vitamin A daily | CBC, BMP, urinalysis every 2 wk | 1) 3% thrombocytopenia; 2) 3% glomerulonephritis; 3) Vitamin A deficiency |

Echocardiographic strain imaging compared with baseline at 6 mo | ∼$450,000 |

| Patisiran (Onpattro) | Phase 3 (APOLLO-B; NCT03997383) | siRNA, targets the 3′ untranslated region of TTR mRNA in the liver to form the RNA-induced silencing complex, initiating mRNA degradation | 0.3 mg/kg IV infusion every 3 wk (max dose 30 mg), plus 3,000 IU vitamin A daily; premedications for infusion: steroids IV, APAP, and H1- and H2-blockers | TBD | 1) Infusion reactions; 2) Vitamin A deficiency | Change in 6-MWT from baseline to 12 mo | ∼$450,000 |

| Vutrisiran | Phase 3 (HELIOS-B; NCT04153149) | siRNA conjugated to GalNAc, targets TTR mRNA in the nucleus and initiates degradation via RNaseH2 | 25 mg SC every 12 wk, Plus 3,000 IU vitamin A daily; no premedications required | TBD | Vitamin A deficiency | Composite outcome of all-cause mortality and recurrent CV hospitalizations at 30-36 mo | TBD |

| AKCEA-TTR-LRx/ION 682884 | Phase 3 (Cardio-TTRansform; NCT04136171) | ASO conjugated to GalNAc, same backbone as inotersen, similar mechanism of action, enhanced liver uptake, 51-fold greater potency, 27-fold lower exposure to drug than predecessor | 45 mg SC every 4 wk, plus 3,000 IU vitamin A daily; no premedications required | TBD | Vitamin A deficiency | Composite of CV mortality and frequency of CV clinical events at 120 wk | TBD |

| Emerging agents for degradation/extraction | |||||||

| PRX-004 | Phase 1 (NCT03336580) | Intravenous monoclonal antibody, clears amyloid deposits by binding to misfolded TTR, not to native TTR | IV every 28 d | n/a | n/a | Dose escalation study to determine safety, tolerability, PK, and PD | n/a |

| NI006 | Phase 1 (NCT04360434) | Recombinant IgG1 human monoclonal antibody, targets misfolded and aggregated form of TTR | IV every 28 d | n/a | n/a | Dose escalation study to determine safety, tolerability, PK, and PD | n/a |

| Anti-SAP monoclonal antibody and CPHPC (Dezamizumab) | Phase 2 (NCT03044353); failed to show improvement in cardiac amyloid burden | Synergism of CPHPC, which clears 90% of circulating SAP, and IgG anti-SAP antibody, which binds to SAP in amyloid deposits, initiating a complement-dependent phagocytic clearance of residual deposits | CPHPC IV daily for up to 3 d, then anti-SAP antibody IV on days 1 and 3, plus 60 mg CPHPC 3 times daily on days 1-11 | n/a | n/a | Safety and efficacy | n/a |

6MWT = 6-minute walk test; APAP = acetaminophen; ASO = antisense oligonucleotide; ATTRv = variant transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis; ATTRwt = wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis; BMP = basic metabolic panel; CBC = complete blood count; CPHPC = (R)-1-[6-[(R)-2-carboxy-pyrrolidin-1-yl]-6-oxo-hexanoyl]pyrrolidine-2-carboxylic acid; CV = cardiovascular; GalNAc = N-acetyl galactosamine; IV = intravenous; LFT = liver function test; NNT = number needed to treat; NSAID = nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; PD = pharmacodynamics; PK = pharmacokinetics; SAP = serum amyloid P component; SC = subcutaneous; siRNA = small interfering ribonucleic acid; TBD = to be determined.

Summary and Conclusions

ATTR-CA, previously thought to be a rare condition, has emerged as an important cause of atrial arrhythmias, conduction system disease, and HF. Rapidly expanding targeted therapies are now available and provide an opportunity to alter the natural history of this progressive disorder. In subsets of patients, such as ATTRv carriers or those diagnosed due to carpal tunnel syndrome, spinal stenosis, or other extracardiac manifestations, early identification and therapy may prevent the development of HF (Central Illustration).

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

Dr Grodin has received personal fees from Pfizer, Alnylam, and Eidos; and has received grant support from the Texas Health Resources Clinical Scholarship and Eidos. Dr Maurer has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health (R01HL139671-01, R21AG058348, and K24AG036778); has received consulting income from Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Intellia, EIdos, Prothena, Akcea, and Alnylam; and his institution has received clinical trial funding from Pfizer, Prothena, Eidos, and Alnylam. Dr Grogan has received research (clinical trial) grant support from Alnylam, Eidos, Pfizer, and Prothena; and has received consulting fees and honoraria paid to Mayo Clinic (no personal compensation) from Akcea, Alnylam, Eidos, Pfizer, and Prothena. Dr Cheng has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health (R21HL152149); and his institution has received clinical trial funding from Eidos and Ionis. Dr Rosenthal has received research (clinical trial) grant support from Akcea; and has received consulting fees from Pfizer. Dr Griffin has reported that he has no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Witteles R.M., Bokhari S., Damy T. Screening for transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy in everyday practice. J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2019;7:709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2019.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lousada I., Comenzo R.L., Landau H., Guthrie S., Merlini G. Light chain amyloidosis: patient experience survey from the Amyloidosis Research Consortium. Adv Ther. 2015;32:920–928. doi: 10.1007/s12325-015-0250-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillmore J.D., Maurer M.S., Falk R.H. Nonbiopsy diagnosis of cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Circulation. 2016;133:2404–2412. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez-Lopez E., Gallego-Delgado M., Guzzo-Merello G. Wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis as a cause of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2585–2594. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nitsche C., Scully P.R., Patel K.P. Prevalence and outcomes of concomitant aortic stenosis and cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akinboboye O., Shah K., Warner A.L. DISCOVERY: prevalence of transthyretin (TTR) mutations in a US-centric patient population suspected of having cardiac amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2020;27:223–230. doi: 10.1080/13506129.2020.1764928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorbala S., Ando Y., Bokhari S. ASNC/AHA/ASE/EANM/HFSA/ISA/SCMR/SNMMI expert consensus recommendations for multimodality imaging in cardiac amyloidosis: part 2 of 2—diagnostic criteria and appropriate utilization. J Nucl Cardiol. 2020;27:659–673. doi: 10.1007/s12350-019-01761-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorbala S., Ando Y., Bokhari S. ASNC/AHA/ASE/EANM/HFSA/ISA/SCMR/SNMMI expert consensus recommendations for multimodality imaging in cardiac amyloidosis: part 1 of 2—evidence base and standardized methods of imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019;26:2065–2123. doi: 10.1007/s12350-019-01760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanna M., Ruberg F.L., Maurer M.S. Cardiac scintigraphy with technetium-99m–labeled bone-seeking tracers for suspected amyloidosis: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2851–2862. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maurer M.S., Mann D.L. The tafamidis drug development program: a translational triumph. J Am Coll Cardiol Basic Trans Science. 2018;3:871–873. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kittleson M.M., Maurer M.S., Ambardekar A.V. Cardiac amyloidosis: evolving diagnosis and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e7–e22. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruberg F.L., Grogan M., Hanna M., Kelly J.W., Maurer M.S. Transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2872–2891. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaishnav J., Hubbard A., Chasler J.E. Management of heart failure in cardiac amyloidosis using an ambulatory diuresis clinic. Am Heart J. 2020;233:122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng R.K., Levy W.C., Vasbinder A. Diuretic dose and NYHA functional class are independent predictors of mortality in patients with transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol CardioOnc. 2020;2:414–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abraham W.T., Adamson P.B., Bourge R.C. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:658–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chacko L., Martone R., Bandera F. Echocardiographic phenotype and prognosis in transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1439–1447. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Lopez E., Gagliardi C., Dominguez F. Clinical characteristics of wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: disproving myths. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:1895–1904. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhuiyan T., Helmke S., Patel A.R. Pressure-volume relationships in patients with transthyretin (ATTR) cardiac amyloidosis secondary to V122I mutations and wild-type transthyretin: Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloid Study (TRACS) Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:121–128. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.910455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez-Duarte A., Barroso F., Mundayat R., Shapiro B. Blood pressure and orthostatic hypotension as measures of autonomic dysfunction in patients from the Transthyretin Amyloidosis Outcomes Survey (THAOS) Auton Neurosci. 2019;222:102590. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2019.102590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palma J.A., Gonzalez-Duarte A., Kaufmann H. Orthostatic hypotension in hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis: epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Clin Auton Res. 2019;29:33–44. doi: 10.1007/s10286-019-00623-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clemmensen T.S., Molgaard H., Sorensen J. Inotropic myocardial reserve deficiency is the predominant feature of exercise haemodynamics in cardiac amyloidosis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:1457–1465. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clemmensen T.S., Eiskjaer H., Molgaard H. Abnormal coronary flow velocity reserve and decreased myocardial contractile reserve are main factors in relation to physical exercise capacity in cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2018;31:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.d’Humieres T., Fard D., Damy T. Outcome of patients with cardiac amyloidosis admitted to an intensive care unit for acute heart failure. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;111:582–590. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng D., Edwards W.D., Oh J.K. Intracardiac thrombosis and embolism in patients with cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2007;116:2420–2426. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.697763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng D., Syed I.S., Martinez M. Intracardiac thrombosis and anticoagulation therapy in cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2009;119:2490–2497. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.785014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giancaterino S., Urey M.A., Darden D., Hsu J.C. Management of arrhythmias in cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol EP. 2020;6:351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Longhi S., Quarta C.C., Milandri A. Atrial fibrillation in amyloidotic cardiomyopathy: prevalence, incidence, risk factors and prognostic role. Amyloid. 2015;22:147–155. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2015.1028616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mints Y.Y., Doros G., Berk J.L., Connors L.H., Ruberg F.L. Features of atrial fibrillation in wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: a systematic review and clinical experience. ESC Heart Fail. 2018;5:772–779. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchis K., Cariou E., Colombat M. Atrial fibrillation and subtype of atrial fibrillation in cardiac amyloidosis: clinical and echocardiographic features, impact on mortality. Amyloid. 2019;26:128–138. doi: 10.1080/13506129.2019.1620724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Am E.A., Dispenzieri A., Melduni R.M. Direct current cardioversion of atrial arrhythmias in adults with cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:589–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donnellan E., Elshazly M.B., Vakamudi S. No association between CHA2DS2-VASc score and left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with transthyretin amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol EP. 2019;5:1473–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2019.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gertz M.A., Falk R.H., Skinner M., Cohen A.S., Kyle R.A. Worsening of congestive heart failure in amyloid heart disease treated by calcium channel–blocking agents. Am J Cardiol. 1985;55:1645. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90995-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubinow A., Skinner M., Cohen A.S. Digoxin sensitivity in amyloid cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1981;63:1285–1288. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.63.6.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donnelly J.P., Sperry B.W., Gabrovsek A. Digoxin use in cardiac amyloidosis. Am J Cardiol. 2020;133:134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Donnellan E., Wazni O.M., Hanna M. Atrial fibrillation in transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: predictors, prevalence, and efficacy of rhythm control strategies. J Am Coll Cardiol EP. 2020;6:1118–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2020.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donnellan E., Wazni O., Kanj M. Atrial fibrillation ablation in patients with transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Europace. 2020;22:259–264. doi: 10.1093/europace/euz314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barbhaiya C.R., Kumar S., Baldinger S.H. Electrophysiologic assessment of conduction abnormalities and atrial arrhythmias associated with amyloid cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Algalarrondo V., Dinanian S., Juin C. Prophylactic pacemaker implantation in familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1069–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Donnellan E., Wazni O.M., Saliba W.I. Cardiac devices in patients with transthyretin amyloidosis: impact on functional class, left ventricular function, mitral regurgitation, and mortality. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2019;30:2427–2432. doi: 10.1111/jce.14180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donnellan E., Wazni O.M., Hanna M., Kanj M., Saliba W.I., Jaber W.A. Cardiac resynchronization therapy for transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e017335. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim E.J., Holmes B.B., Huang S. Outcomes in patients with cardiac amyloidosis and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Europace. 2020;22:1216–1223. doi: 10.1093/europace/euaa094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin G., Dispenzieri A., Kyle R., Grogan M., Brady P.A. Implantable cardioverter defibrillators in patients with cardiac amyloidosis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2013;24:793–798. doi: 10.1111/jce.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varr B.C., Zarafshar S., Coakley T. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator placement in patients with cardiac amyloidosis. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamon D., Algalarrondo V., Gandjbakhch E. Outcome and incidence of appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in patients with cardiac amyloidosis. Int J Cardiol. 2016;222:562–568. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Donnellan E., Wazni O.M., Hanna M., Saliba W., Jaber W., Kanj M. Primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2020;43:1401–1403. doi: 10.1111/pace.14023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Priori S.G., Blomstrom-Lundqvist C., Mazzanti A. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: the Task Force for the Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC) Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2793–2867. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Khatib S.M., Stevenson W.G., Ackerman M.J. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:e91–e220. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Virani S.S., Alonso A., Benjamin E.J. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e139–e596. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenblum H., Masri A., Narotsky D.L. Unveiling outcomes in coexisting severe aortic stenosis and transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;23:250–258. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Treibel T.A., Fontana M., Gilbertson J.A. Occult transthyretin cardiac amyloid in severe calcific aortic stenosis: prevalence and prognosis in patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:e005066. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Castano A., Narotsky D.L., Hamid N. Unveiling transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis and its predictors among elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2879–2887. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scully P.R., Treibel T.A., Fontana M. Prevalence of cardiac amyloidosis in patients referred for transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:463–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cavalcante J.L., Rijal S., Abdelkarim I. Cardiac amyloidosis is prevalent in older patients with aortic stenosis and carries worse prognosis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2017;19:98. doi: 10.1186/s12968-017-0415-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Longhi S., Lorenzini M., Gagliardi C. Coexistence of degenerative aortic stenosis and wild-type transthyretin-related cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2016;9:325–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grogan M., Scott C.G., Kyle R.A. Natural History of Wild-Type Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis and Risk Stratification Using a Novel Staging System. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1014–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumar S.K., Gertz M.A., Dispenzieri A. Validation of Mayo Clinic staging system for light chain amyloidosis with high-sensitivity troponin. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:171–173. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.01398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nitsche C., Aschauer S., Kammerlander A.A. Light-chain and transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis in severe aortic stenosis: prevalence, screening possibilities, and outcome. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:1852–1862. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scully P.R., Patel K.P., Treibel T.A. Prevalence and outcome of dual aortic stenosis and cardiac amyloid pathology in patients referred for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2759–2767. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu B., Godoy Rivas C., Rodriguez E.R. Unrecognized cardiac amyloidosis at the time of mitral valve surgery: incidence and outcomes. Cardiology. 2019;142:253–258. doi: 10.1159/000499933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Volz M.J., Pleger S.T., Weber A. Initial experience with percutaneous mitral valve repair in patients with cardiac amyloidosis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020:e13473. doi: 10.1111/eci.13473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Giannini F., Colombo A. Percutaneous treatment of tricuspid valve in refractory right heart failure. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2019;21:B43–B47. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/suz031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maurer M.S., Hanna M., Grogan M. Genotype and phenotype of transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: THAOS (Transthyretin Amyloid Outcome Survey) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Quarta C.C., Buxbaum J.N., Shah A.M. The amyloidogenic V122I transthyretin variant in elderly black Americans. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:21–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jacobson D.R., Alexander A.A., Tagoe C., Buxbaum J.N. Prevalence of the amyloidogenic transthyretin (TTR) V122I allele in 14 333 African-Americans. Amyloid. 2015;22:171–174. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2015.1051219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Quarta C.C., Falk R.H., Solomon S.D. V122I transthyretin variant in elderly black Americans. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1769. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1503222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Buxbaum J., Jacobson D.R., Tagoe C. Transthyretin V122I in African Americans with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1724–1725. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sinha A., Zheng Y., Nannini D. Association of the V122I transthyretin amyloidosis genetic variant with cardiac structure and function in middle-aged black adults: Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;6:1–5. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.6623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haq M., Pawar S., Berk J.L., Miller E.J., Ruberg F.L. Can 99mTc-pyrophosphate aid in early detection of cardiac involvement in asymptomatic variant TTR amyloidosis? J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2017;10:713–714. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scully P.R., Morris E., Patel K.P. DPD quantification in cardiac amyloidosis: a novel imaging biomarker. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2020;13:1353–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Minutoli F., di Bella G., Mazzeo A. Serial scanning with 99mTc-3, 3-diphosphono-1, 2-propanodicarboxylic acid (99mTc-DPD) for early detection of cardiac amyloid deposition and prediction of clinical worsening in subjects carrying a transthyretin gene mutation. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019 Nov 18 doi: 10.1007/s12350-019-01950-2. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pan J.A., Kerwin M.J., Salerno M. Native T1 mapping, extracellular volume mapping, and late gadolinium enhancement in cardiac amyloidosis: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2020;13:1299–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tamarappoo B., Samuel T.J., Elboudwarej O. Left ventricular circumferential strain and coronary microvascular dysfunction: A report from the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation Coronary Vascular Dysfunction (WISE-CVD) project. Int J Cardiol. 2021;327:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zamani S.K., Samuel T.J., Wei J. Left atrial stiffness in women with ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease: novel insight from left atrial feature tracking. Clin Cardiol. 2020;43:986–992. doi: 10.1002/clc.23395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]