Abstract

Sotos syndrome, characterized by cerebral gigantism with neurologic disorders, is an overgrowth syndrome caused by mutations of the NSD1 gene, with an estimated prevalence of 1:10,000-1:50,000. We herein describe the first case of Sotos syndrome complicated by acute coronary syndrome, for which emergency coronary artery bypass grafting was performed. (Level of Difficulty: Intermediate.)

Key Words: acute coronary syndrome, coronary aneurysm, coronary artery bypass grafting, coronary artery disease, Sotos syndrome

Abbreviations and Acronyms: AV, atrioventricular; CT, computed tomography; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LITA, left internal thoracic artery; LMT, left main trunk; OM, obtuse marginal branch; PA, pulmonary artery; PDA, posterior descending artery; RCA, right coronary artery; RITA, right internal thoracic artery

Central Illustration

A 41-year-old man with Sotos syndrome, who had been dependent on hemodialysis for 2 years, experienced persistent severe hypotension during hemodialysis. A 12-lead electrocardiogram revealed ST-segment depression in multiple leads (ie, V3-V6, II, III, and aVF) and ST-segment elevations in V1 and aVR ≥1 mm (Figure 1). He was then referred to the authors’ center because there were findings suggestive of acute coronary syndrome.

Learning Objectives

-

•

To recognize that Sotos syndrome, an overgrowth phenomenon caused by the pathogenic variants of NSD1, can develop severe coronary artery disease in adulthood, requiring surgical revascularization.

-

•

To promote the immediate diagnosis of coronary artery disease and to highlight the importance of early screening in adults with Sotos syndrome.

Figure 1.

A 12-Lead Electrocardiogram on Admission

A 12-lead electrocardiogram revealing ST-segment depression in V3 to V6, II, III, and aVF, and ST-segment elevations in V1 and aVR ≥1 mm.

Medical History

During childhood, the patient had a large and long head, with a circumferential diameter of 61 cm, and showed signs of impaired intelligence (ie, delay in language development). A diagnosis of Sotos syndrome was made when he was 2 years old (Figure 2A). He underwent surgery for vesicoureteral reflux when he was 4 years old. However, his renal function began to deteriorate several years later. Since then, he had been treated for chronic renal failure by a primary pediatrician. Two years before this presentation, he became dependent on hemodialysis. His physical appearance was characterized by scoliosis (Figure 2B), spider-like fingers (Figure 2C), tall stature, and macrocephaly (Figure 2D), which were all consistent with Sotos syndrome.

Figure 2.

Appearance of This Patient in Childhood and Adulthood

(A) Large, long head of patient, with a high bossed forehead, (B) scoliosis, (C) spider-like fingers, (D) tall stature, and macrocephaly, all of which are consistent with typical features of Sotos syndrome.

Differential Diagnosis

Based on the clinical symptoms and electrocardiographic findings, the differential diagnosis included angina, acute myocardial infarction, and acute aortic dissection.

Investigations

On physical examination, the patient showed impaired intelligence, a height of 173 cm, and a weight of 48.6 kg. Electrocardiography revealed sinus tachycardia, with a heart rate of 150 beats/min and a systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg. Coronary angiography revealed an intact right coronary artery system (Figure 3A, Video 1A) and significant stenosis in the proximal part of the left main trunk, accompanied by coronary aneurysm at the distal left main trunk (Figure 3B, Video 1B). Intra-aortic balloon pumping was promptly initiated. Echocardiography revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 30% and moderate mitral regurgitation caused by left ventricular remodeling. Three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) revealed severe calcification in the left coronary artery system and significant stenosis in the obtuse marginal branch (Figures 3C and 3D).

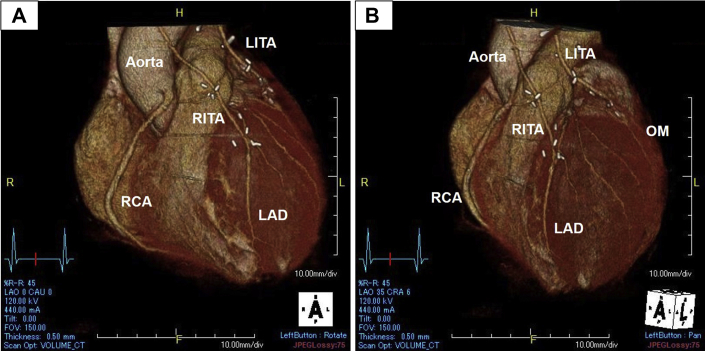

Figure 3.

Coronary Angiography and 3-Dimensional CT on Admission

Coronary angiographic views showing (A) intact right coronary artery system and (B) significant stenosis in the proximal part of the left main trunk (LMT) (white arrow) and a coronary aneurysm at the distal part of the LMT (asterisk). (C and D) Three-dimensional computed tomographic views showing severe calcification of the left coronary artery system (red arrows) and stenosis in the obtuse margin branch. AV = atrioventricular; CT = computed tomography; LAD = left anterior descending artery; OM = obtuse marginal branch; PA = pulmonary artery; PDA = posterior descending artery.

Management

The patient was transferred to the surgical theater. Emergency on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting was performed through a median sternotomy, designed from the right internal thoracic artery to the left anterior descending artery, and the left internal thoracic artery to the obtuse marginal branch.

Discussion

Sotos syndrome is an overgrowth phenomenon caused by pathogenic variants of the NSD1 gene. It is characterized by tall stature and/or macrocephaly, distinctive facial features, and nonprogressive neurologic disorder(s) with intellectual disability (1, 2, 3). This syndrome affects male and female individuals equally and occurs in all ethnic groups, with an estimated prevalence of 1:10,000-1:50,000 (2).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of Sotos syndrome associated with severe coronary artery disease requiring emergency coronary artery bypass grafting. There may be several explanations as to why the patient described in this report had not received a diagnosis of coronary artery disease before experiencing an acute coronary syndrome. First, although cardiac involvement among Sotos syndrome patients is not rare, its most common feature is structural heart defects (ie, a patent ductus arteriosus or atrial septal defect), which are usually diagnosed in childhood. Moreover, no previous reports have described a concomitant coronary artery disease with Sotos syndrome (4). Second, the patient stayed at home, and his physical activity was not strenuous enough to induce angina symptoms. This may have diverted physicians from the presence of coronary artery disease. It is also worthwhile to note that no signs of atherosclerosis were found in the vascular system throughout the body except for coronary arteries (data not shown)

The knowledge and experience gained from this case are valuable. Sotos syndrome was first described in 1964, and patients whose conditions were diagnosed during childhood are expected to reach adulthood (1). This case report highlights the importance of coronary artery disease screening in adults with Sotos syndrome, even in younger patients. The diagnosis of coronary artery disease should not be delayed because it becomes more difficult to detect and manage owing to the intellectual disability intrinsically associated with Sotos syndrome. This uncommon case of Sotos syndrome associated with acute coronary events can help clinicians establish the diagnosis and respond more appropriately.

Follow-Up

Postoperative 3-dimensional CT revealed patent bypass grafts (Figures 4A and 4B). The patient required extensive volume management and heart failure medication after the surgery, because he presented with moderate MR secondary to left ventricular remodeling at the time of coronary artery bypass grafting. However, the patient was discharged on postoperative day 47 without serious complications.

Figure 4.

Postoperative 3-Dimensional CT

Postoperative 3-dimensional computed tomographic views showing (A and B) patency in bypass grafts. LITA = left internal thoracic artery; RCA = right coronary artery; RITA = right internal thoracic artery; other abbreviations as in Figure 3.

Conclusions

We presented the first case of Sotos syndrome complicated by acute coronary syndrome, for which emergency coronary artery bypass grafting was performed. This case report highlights the importance of coronary artery disease screening in adults with Sotos syndrome, even in younger patients.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For supplemental videos, please see the online version of this paper.

Contributor Information

Takashi Murakami, Email: takasuii.murakami430@gmail.com.

Yoshiki Sawa, Email: sawa-p@surg1.med.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Appendix

Supplemental Video 1ACoronary angiography showing (A) intact right coronary artery system and (B) significant stenosis in the proximal part of the left main trunk (LMT) and a coronary aneurysm at the distal part of the LMT.

Coronary angiography showing (A) intact right coronary artery system and (B) significant stenosis in the proximal part of the left main trunk (LMT) and a coronary aneurysm at the distal part of the LMT.

References

- 1.Sotos J.F., Dodge P.R., Muirhead D., Crawford J.D., Talbot N.B. Cerebral gigantism in childhood: a syndrome of excessively rapid growth with acromegalic features and a non-progressive neurologic disorder. N Engl J Med. 1964;271:109–116. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196407162710301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cole T.R.P., Hughes H.E. Sotos syndrome: a study of the diagnostic criteria and natural history. J Med Genet. 1994;31:20–32. doi: 10.1136/jmg.31.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aoki N., Oikawa A., Sakai T. Serial neuroimaging studies in Sotos syndrome (cerebral gigantism syndrome) Neurol Res. 1998;20:149–152. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1998.11740498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaneko H., Tsukahara M., Tachibana H., Kurashige H., Kuwano A., Kajii T. Congenital heart defects in Sotos sequence. Am J Med Genet. 1987;26:569–576. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320260310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Video 1ACoronary angiography showing (A) intact right coronary artery system and (B) significant stenosis in the proximal part of the left main trunk (LMT) and a coronary aneurysm at the distal part of the LMT.

Coronary angiography showing (A) intact right coronary artery system and (B) significant stenosis in the proximal part of the left main trunk (LMT) and a coronary aneurysm at the distal part of the LMT.