Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this study was to gather information on the prevalence and risk factors for scar pain and sensibility disorders after breast cancer surgery, as only limited information of these complaints are available.

Material and Methods

A clinical cohort study using a non-validated questionnaire was conducted among women who presented to routine follow-up at the Breast Cancer Center Rostock, Germany. The subjects were informed that the subjective perception and sensation were in the foreground and that the questionnaire had to be filled out independently according to the current feeling.

Results

Overall 175 patients could be evaluated. The prevalence of scar pain was 30.8% after breast conserving therapy (BCT) and 34.5% after mastectomy. Following BCT 87.5%, respectively 81.8% of women after mastectomy were very satisfied or satisfied with the scarring. Sensory disorders were increased in the mastectomy group (p = 0.001). Scar pain after previous surgery was a risk factor to develop sensory disorders after BCT (p = 0.008) and mastectomy (p = 0.029). For patients receiving mastectomy, sensory disorders after previous breast surgeries increased the risk for sensory disorders (p = 0.029). Smoking was a risk factor for sensory disorders after mastectomy (p = 0.048). Multivariate analysis could not confirm any of the risk factors.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated a high satisfaction with scarring after breast surgery and a low level of scar pain. A lack of postoperative information, as well as a low level of actually performed scar care after surgery were observed. Increased focus should be on improved information on postoperative scare care.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Breast surgery, Scar, Scar pain, Sensory disorder, Prevention

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the leading cancer in women. The incidence varies across European countries, but the overall lifetime risk is about 1 in 8. Once BC is diagnosed, 4 different subtypes are of clinical relevance [1]. After having received the final histologic results, patients are informed about the multidisciplinary treatment decision. Independent of whether patients have an indication for neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy, surgery is still needed. Even when pathologic complete response (pCR) is achieved after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, breast surgery (BS) is required and recommended [2]. Up to today, further trials are needed to investigate whether surgery may be safely omitted in the future. Until then, BS remains necessary even after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and pCR. Taking into account that 50% of these patients describe persistent breast pain and inferior quality of life after lumpectomy, pain and scarring after BS is of relevance to patients [3]. Hypertrophic scars or keloid formation can occur after injuries, surgical interventions or spontaneously. These wound healing disorders lead to a functional, cosmetic and sensory disorder in the scar area. Pathophysiologically, there is a disbalance between synthesis and degradation of the extracellular matrix [4, 5]. Both surgical and conservative forms of therapy are of great importance. In addition to a high recurrence rate of 45–100%, surgical therapy of scars or keloids can lead to progressive scarring [6]. New data on scarring and sensory disorders after BS are hardly available. Previous studies did not assess the impact of surgical scars specifically [7, 8, 9]. The aim of this work was to identify the current prevalence as well as risk factors that led to the development of scar pain and/or sensory disorders after breast-conserving therapy (BCT) or mastectomy in BC patients. Another aim of this study was the question to what extent a postoperative information for scar prophylaxis was given and what its clinical consequences were.

Material and Methods

Between March and December 2015, patients were treated at the Breast Cancer Center Rostock, Germany, and recruited to participate in this cohort trial. The recruitment took place as part of the routine follow-up. All subjects had previously undergone BS at the time of the survey. After receiving written consent, the 5-page questionnaire was handed out and completed by the patient. The questionnaire was an unvalidated questionnaire that was designed by the first and second author based on the scientific question for this study. The questionnaire consisted of 34 items. To complete patient and tumor characteristics, data from the cancer registry of the Rostock University Women's Clinic was used. Inclusion criteria were female patients, BCT or mastectomy, unilateral BC, no metastasis. Exclusion criteria included male BC, any kind of primary or secondary reconstructive procedure or lipofilling, reduction mammoplasties, bilateral BC, patients with or after local recurrence. For statistical analysis, IBM SPSS® version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used. The data were evaluated using the χ2 test. Univariance as well as multivariance analyses were carried out. For the overall collective and the dependent binary variable pain, those variables were included in the multivariance analysis that showed a p ≤ 0.15 in the univariance analysis. The significance level of p ≤ 0.20 was determined for the dependent binary variable pain and for the respective operation groups BCT and mastectomy. A significance level of p = 0.05 and a CI of 95% were established for all statistical tests. p values with a p ≤ 0.05 were statistically significant.

Results

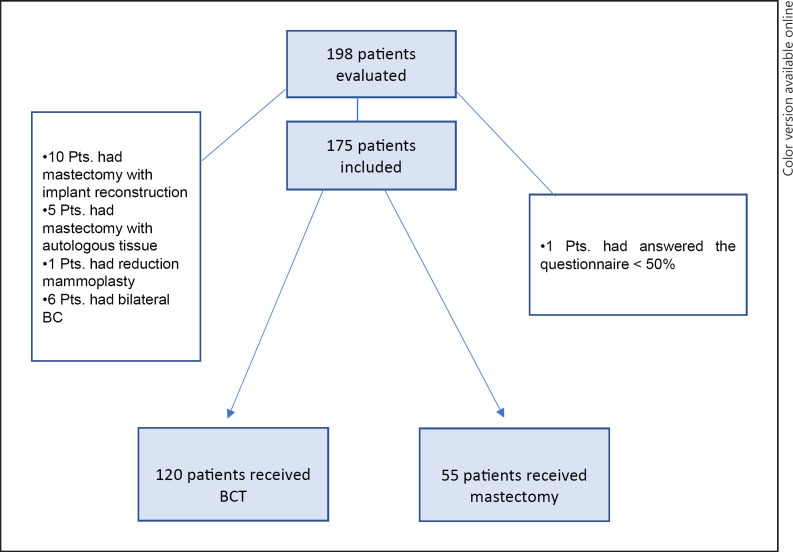

Of 198 patients, 175 could be included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). Mean age for the BCT group was 60.9 years (range 38–83 years, SD 10.5) and 64.4 years in the mastectomy group (range 27–86 years, SD 11.4; p = 0.054). Data on tumor size was available for 89 patients receiving BCT and for 45 patients receiving mastectomy. Patients undergoing mastectomy had significantly higher tumor size (p < 0.001). For nodal status, data were available for 97 patients in the BCT and for 45 patients in the mastectomy group. Patients undergoing mastectomy had increased nodal involvement (p < 0.001). Due to the advanced stage of patients receiving mastectomy, post-surgery radiation therapy was performed in 34 patients (77.3%). Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. No difference in developing breast pain was observed for BCT versus mastectomy (p = 0.625). Age did not influence the development of breast pain (p = 0.141). Sensory disorders were increased in the mastectomy group (p = 0.001). Univariate analysis revealed an increased risk for sensory disorders after mastectomy in smokers (p = 0.048) and for patients with pre-operations on the breast undergoing BCT (p = 0.039). Patients who experienced scar pain or sensory disorders after previous breast surgeries had an increased risk for developing scar pain (p = 0.026) or sensory disorders (p = 0.003) after BCT. Scar pain after previous BS was an additional risk factor to develop sensory disorders after BCT (p = 0.008). For patients receiving mastectomy, pain or sensory disorders after previous BS increased the risk for sensory disorders after mastectomy (p = 0.029, p = 0.004). Neither the expression of the estrogen nor the progesterone receptor were related to increased pain or sensory disorders after BCT or mastectomy. Data on the usage of anti-estrogen therapy could not be evaluated. Data on the HER2 status could not be evaluated. Neither graduation status, time period that had passed since BS, type of adjuvant radiation therapy or chemotherapy nor other risk factors did influence the development of breast pain or sensory disorders in the BCT or mastectomy group. All patients receiving chemotherapy had adjuvant treatment. Results of the univariate analysis are shown in Tables 2 and 3. None of the parameters included into the multivariate analysis yield statistically significant risk factors for developing pain or sensory disorders after BCT or mastectomy. The following parameters were included into the multivariate analysis for scar pain (whole collective): smoking (OR 3.999; 95% CI 0.880–18.166; p = 0.073), pain after previous surgery (OR 6.460; 95% CI 0.789–52.891; p = 0.082), obtaining information on postoperative scar care (OR 2.254; 95% CI 0.524–9.701; p = 0.275) and sensory disorders (OR 3.155; 95% CI 0.289–34.470; p = 0.346). The following parameters were included into the multivariate analysis for sensory disorders (whole collective): development of keloid during previous surgeries (OR 3.346; 95% CI 0.279–40.111; p = 0.341), wound infection (OR 0.388; 95% CI 0.198–66.160; p = 0.388), complications during previous surgeries (OR 0.309; 95% CI 0.017–5.748; p = 0.431) and pain during previous surgeries (OR 1.039; 95% CI 0.080–14.855; p = 0.949).

Fig. 1.

Consort flow diagram. Pts., patients; BC, breast cancer; BCT, breast-conserving therapy.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and evaluation of the questionnaire (overall patient cohort)

| Breast-conserving therapy |

Mastectomy | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean ± SD | 60.9±10.5 | 64.4±11.4 | 0.054a |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 27.4±5.4 | 27.2±5.6 | 0.869a |

| Time since surgery, n (%) | 0.201a | ||

| 0–6 months | 7 (5.8) | 5 (9.1) | |

| 7–12 months | 7 (5.8) | 7 (12.7) | |

| 13–24 months | 10 (8.4) | 7 (12.7) | |

| >24 months | 96 (80.0) | 36 (65.5) | 0.001b |

| Radiation therapy after surgeryc, n (%) |

|

||

| Yes | 96 (95.0) | 34 (77.3) | |

| No | 5 (5.0) | 10 (22.7) | 0.103b |

| How satisfied are you with the scarring?, n (%) |

|

||

| Very satisfied | 67 (55.8) | 21 (38.2) | |

| Satisfied | 38 (31.7) | 24 (43.6) | |

| Acceptable | 8 (6.7) | 8 (14.6) | |

| Not satisfied | 6 (5.0) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Not satisfied at all | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.8) | 0.625b |

| Do you have pain in the scar tissue?, n (%) |

|

||

| Yes | 37 (30.8) | 19 (34.5) | |

| No | 83 (69.2) | 36 (65.5) | 0.466b |

| How severe is the pain?, n (%) |

|

||

| No pain | 73 (60.8) | 33 (62.3) | |

| Little pain | 33 (27.5) | 11 (20.8) | |

| Medium pain | 13 (8.4) | 8 (15.0) | |

| Severe pain | 4 (3.3) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Very severe pain | 0 | 0 | 0.107b |

| Are you limited in your daily activity due to the pain?, n (%) |

|

||

| Yes | 12 (11.9) | 10 (22.2) | |

| No | 89 (88.1) | 35 (77.8) | 0.017b |

| Are you limited in your movements due to the scaring?, n (%) |

|

||

| Yes | 15 (12.6) | 15 (27.3) | |

| No | 104 (87.4) | 40 (72.7) | 0.266b |

| Did you experience pain relief over time after surgery?, n (%) |

|

||

| No pain | 18 (18.6) | 4 (8.7) | |

| Pain decreased | 61 (62.9) | 28 (60.9) | |

| Pain is the same | 13 (13.4) | 10 (21.7) | |

| Pain increased | 5 (5.1) | 4 (8.7) | 0.103b |

| Did the pain increase after radiation therapy?, n (%) |

|

||

| Yes | 14 (14.4) | 3 (7.5) | |

| No | 83 (85.6) | 37 (92.5) | 0.644b |

| If possible: would you undergo a medical procedure to reduce the pain, n (%) |

|

||

| Yes | 13 (17.6) | 6 (14.0) | |

| No | 61 (82.4) | 37 (86.0) | 0.393b |

| What kind of medical procedure would you prefer to reduce the pain?, n (%) |

|

||

| Surgery | 5 (7.5) | 6 (18.2) | |

| Radiation | 2 (3.0) | 0 | |

| Other | 7 (10.4) | 2 (6.1) | |

| I do not know | 52 (77.6) | 24 (72.7) | |

| None | 1 (1.5) | 1 (3.0) | 0.893b |

| Are you able to differentiate between pain and limited sensitivity?, n | (%) |

|

|

| Yes | 82 (72.5) | 38 (74.6) | |

| No | 22 (19.5) | 10 (19.5) | |

| No is the same | 9 (8.0) | 3 (5.9) | 0.085b |

| Do you experience sensitivity disorders in the scar tissue?, n (%) |

|

||

| Yes | 25 (22.5) | 19 (35.2) | |

| No | 86 (77.5) | 35 (64.8) | |

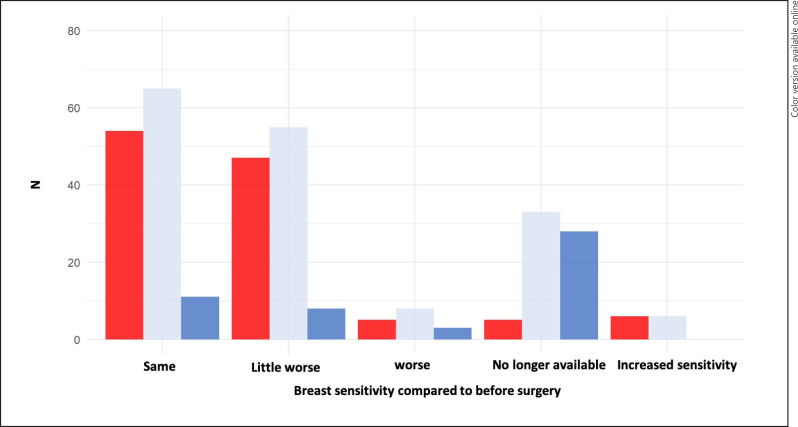

| How would you describe the sensitivity of breast compared to before surgery and radiation?, n (%) | <0.000b | ||

| The same | 54 (46.2) | 11 (22.0) | |

| Little worse | 47 (40.2) | 8 (16.0) | |

| Worse | 5 (4.3) | 3 (6.0) | |

| More sensitive | 6 (5.1) | 0 | |

| Not existing | 5 (4.2) | 28 (56.0) | 0.042b |

| Do you dislike the loss of sensitivity in daily life?, n (%) |

|

||

| Yes | 7 (9.1) | 11 (22.0) | |

| No | 70 (90.9) | 39 (78.0) | 0.719b |

| If possible, would you undergo a medical procedure to increase the sensitivity?, n (%) |

|

||

| Yes | 8 (10.7) | 4 (9.1) | |

| No | 67 (89.3) | 40 (90.9) | 0.021b |

| Did you receive information regarding skin care after surgery?, n (%) |

|

||

| Yes | 38 (52.1) | 23 (76.7) | |

| No | 35 (47.9) | 7 (23.3) | 0.865b |

| Did you perform skin care after surgery?, n (%) |

|

||

| Yes | 59 (76.6) | 25 (78.1) | |

| No | 18 (23.4) | 7 (21.9) | 0.252b |

| Marital status, n (%) |

|

||

| Single | 9 (11.4) | 5 (13.5) | |

| Married | 52 (65.8) | 21 (56.8) | |

| Divorced | 9 (11.4) | 2 (5.4) | |

| Widowed | 9 (11.4) | 9 (24.3) | 0.133b |

| Was chemotherapy performed after surgery, n (%) |

|

||

| Yes | 63 (58.9) | 37 (71.2) | |

| No | 44 (41.1) | 15 (28.8) | 0.938b |

| Smoking, n (%) |

|

||

| Yes | 15 (13.2) | 7 (12.7) | |

| No | 99 (86.8) | 48 (87.3) | 0.073b |

| Diabetes, n (%) |

|

||

| Yes | 10 (8.7) | 10 (18.2) | |

| No | 105 (91.3) | 45 (81.8) | 0.355b |

| Hypertension, n (%) |

|

||

| Yes | 53 (45.7) | 21 (38.2) | |

| No | 63 (54.3) | 34 (61.8) |

t test for independent samples;

Pearson-χ-Quadrat test;

In 1 patient with breast-conserving therapy and in 2 patients with mastectomy, no radiation therapy was performed; BMI, body mass index; in case numbers are not accounting for the full amount of patients described in the cohort: data were not available; percentage: off patients to be evaluated. SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of risk factors for developing breast pain or sensory disorders in patients undergoing breast-conserving therapy

| Risk factor | Risk to develop pain (n = 82) |

Risk to develop sensory disorder (n = 102) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Sensory disorders (after previous surgeries) | 5.172 | 1.212–22.065 | 0.026 | 13.000 | 2.422–69.778 | 0.003 |

| Scar pain (after previous surgeries) | 2.593 | 0.884–7.603 | 0.083 | 4.500 | 1.469–13.788 | 0.008 |

| Previous surgeries | 2.285 | 0.715–7.299 | 0.163 | 2.833 | 0.608–13.207 | 0.233 |

| Wound infection | 0.574 | 0.668–9.224 | 0.174 | 6.167 | 1.573–24.171 | 0.009 |

| Hypertension | 0.501 | 0.269–1.365 | 0.226 | 0.418 | 0.158–1.107 | 0.079 |

| Body mass index | 0.436 | 0.090–2113 | 0.303 | 1.163 | 0.377–6.909 | 0.519 |

| Problems associated with previous surgeries | 1.646 | 0.632–4.283 | 0.307 | 3.350 | 1.196–9.381 | 0.039 |

| Information about postoperative scar care | 1.726 | 0.553–5.384 | 0.347 | 0.524 | 0.153–1.799 | 0.305 |

| Performance of scar care | 1.705 | 0.433–6.716 | 0.446 | 1.250 | 0.307–5.093 | 0.756 |

| Smoking | 1.609 | 0.525–4.932 | 0.405 | 0.880 | 0.225–3.440 | 0.854 |

| Diabetes mellitus type II | 1.591 | 0.420–6.034 | 0.494 | 1.116 | 0.211–5.909 | 0.897 |

| Chemotherapy | 0.792 | 0.341–1.841 | 0.588 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Expression of ER receptor | 0.791 | 0.308–2.033 | 0.626 | 0.497 | 0.171–1.445 | 0.199 |

| Expression of PR receptor | 0.864 | 0.345–2.159 | 0.754 | 0.672 | 0.235–1.918 | 0.457 |

| Expression of Her2 receptor | 0.402 | 0.143–1.132 | 0.085 | 0.945 | 0.315–2.837 | 0.920 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ER, estrogen; PR, progesterone, Her2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of risk factors for developing breast pain or sensory disorders in patients undergoing mastectomy

| Risk factor | Risk to develop pain (n = 82) | Risk to develop sensory disorder (n = 102) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Sensory disorders (after previous surgeries) | 7.286 | 0.697–76.181 | 0.097 | 0.292 | 0.188–0.453 | 0.004 |

| Scar pain (after previous surgeries) | 0.300 | 0.196–0.458 | 0.300 | 0.306 | 0.201–0.467 | 0.029 |

| Previous surgeries | 0.750 | 0.482–10.328 | 0.305 | 2.125 | 0.395–11.437 | 0.380 |

| Wound infection | 1.378 | 0.208–9.142 | 0.740 | 1.208 | 0.182–8.002 | 0.844 |

| Hypertension | 0.917 | 0.291–2.889 | 0.882 | 0.692 | 0.213–2.264 | 0.541 |

| Body mass index | 1.250 | 0.189–8.268 | 0.817 | 1.476 | 0.221–9.842 | 0.687 |

| Problems associated with previous surgeries | 2.285 | 0.183–3.068 | 0.689 | 3.214 | 0.669–15.453 | 0.145 |

| Information about postoperative scar care | 1.923 | 0.307–12.053 | 0.485 | 0.400 | 0.071–2.246 | 0.298 |

| Performance of scar care | 1.964 | 0.318–12.124 | 0.467 | 5.538 | 0.579–52.955 | 0.137 |

| Smoking | 2.933 | 0.582–14.772 | 0.192 | 5.893 | 1.019–34.079 | 0.048 |

| Diabetes mellitus type II | 1.333 | 0.326–5.455 | 0.689 | 0.906 | 0.199–4.120 | 0.899 |

| Chemotherapy | 0.720 | 0.208–2.491 | 0.604 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Expression of ER receptor | 0.838 | 0.221–3.183 | 0.795 | 0.107 | 0.024–0.467 | 0.003 |

| Expression of PR receptor | 1.158 | 0.314–4.271 | 0.826 | 0.174 | 0.044–0.684 | 0.012 |

| Expression of Her2 receptor | 0.524 | 0.144–1.909 | 0.328 | 0.889 | 0.248–3.183 | 0.856 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ER, estrogen; PR, progesterone, Her2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

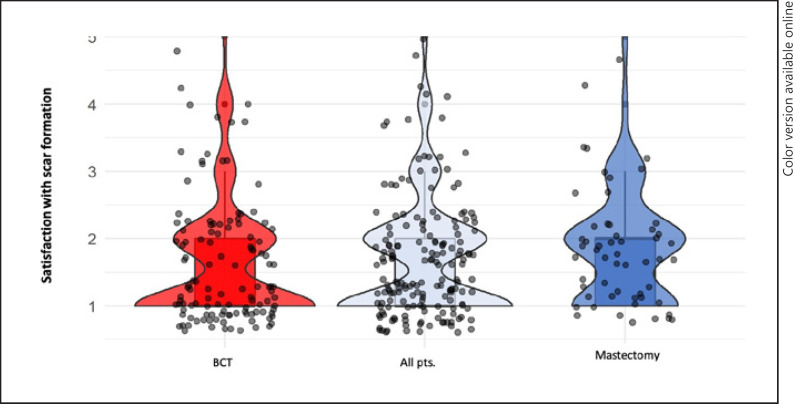

Scarring and Breast Pain

Among all patients, 88 (50.3%) were highly satisfied, 62 (35.4%) satisfied, 16 (9.1%) found the scarring acceptable, 7 (4.0%) were not satisfied and 2 patients (1.1%) were not at all satisfied. The prevalence of scar pain within the whole collective accounted to 32%. Looking at the 2 patient groups separately, the prevalence of scar pain was 30.8% in the BCT and 34.5% in the mastectomy group. Statistics showed a high significance between the pain symptoms and dissatisfaction with the scar (p < 0.001). No difference was observed between BCT or mastectomy scars (Fig. 2). Of the 175 patients, 144 patients (82.8%) denied restricted movement at all due to scar formation. Women with mastectomy were increasingly limited with regard to the restriction of arm movement due to scar formation (p = 0.017). The development of pain was significantly associated with restricted arm movement (p < 0.001). A high correlation between pain and movement restrictions was shown in the 2 surgical groups BET and mastectomy, (BET, p < 0.001; mastectomy, p = 0.002). Restriction in everyday life due to pain symptoms was observed for BCT and mastectomy patients (p < 0.001 and p = 0.001). Postoperative regression of the pain symptoms was recorded in 89 patients (62.2%) of the total group (n = 143). Of these, 23 patients (16.1%) reported constant pain symptoms. Postoperative progressive pain was reported in 9 patients (6.3%). Twenty-two patients (15.4%) showed no pain symptoms. No difference was observed for BCT versus mastectomy (p = 0.266). Radiation therapy did not influence pain symptoms in either group. Only 14% of patients with breast pain would consider a surgical or alternative procedure to reduce the pain.

Fig. 2.

Satisfaction with scaring after surgery. 1, very satisfied; 2, satisfied; 3, acceptable; 4, not satisfied; 5, not satisfied at all.

Scarring and Sensory Disorders

Overall, 44 patients (26.7%) were affected by a sensory disorder within the scar region. In the BCT group (n = 111), 25 patients (22.5%) had postoperative sensory restrictions, respectively 19 patients (35.2%) in the mastectomy group (n = 54; p = 0.084). A differentiation between pain and sensory disorder was possible for 120 (73.2%) patients. With regard to the complete breast, significantly more patients in the mastectomy group experienced a sensory loss overall (p < 0.001; Fig. 3). Patients with mastectomy and sensory disorder experienced significantly higher limitations in daily life (p < 0.05). Only 11.4% would undergo an additional procedure to improve sensitivity.

Fig. 3.

Breast sensitivity compared to before surgery.

Education to Care for or Avoid Scarring

Data whether advice on how to care for or avoid scarring was available for 103 patients. Educative scar prevention was performed in 61 patients (59.2%) but did not influence the development of scar pain and sensitivity disorders within the groups. Information whether postoperative scar care was individually performed or not was accessible for 109 patients. Of these, 84 (77.1%) performed scare care after surgery, but this did not improve scarring or sensory disorders in any of the 2 groups. Using multiple binary regression analysis, none of the univariate significant factors for the development of scarring of sensory disorders could be confirmed.

Discussion

This study gives further insight into the relevance of scare pain and sensitive disorders after breast cancer surgeries. We calculated a prevalence for scar pain for the whole collective of 32%. Looking at the 2 patient groups separately, the prevalence of scar pain was 30.8% in the BCT and 34.5% in the mastectomy group. Within our patient collective, no definitive modifiable risk factors could be identified. Nevertheless, it is of clinical importance that in all patients, regardless of BCT or mastectomy, a high satisfaction rate with the postoperative scar formation was observed. After BCT, 87.5% of women were very satisfied or satisfied with the scarring. The same applied for the mastectomy group, with a corresponding satisfaction rate of 81.8%. However, those patients with mastectomy and sensory disorder experienced significantly higher limitations in daily life. A Swedish study of 297 patients after BS showed a similar high satisfaction rate with the appearance of the scar in 81% of patients (median age 62 years, median follow-up of 16 months after surgery) [10]. From the surgical reports, we were not able to determine how much breast volume was resected during BCT and how much this might influence the appearance of the scar and the pain. However, Dahlbäck et al. [10] found that an estimated excision of ≥20% of preoperative breast volume was a risk factor for dissatisfaction with the scar and the overall aesthetic appearance. Age did not influence pain or sensitivity disorders within the scar and data in the literature are varying [11, 12]. Although our collective of patients with scar pain and sensitivity disorder, who describe limitations in daily living is small, a study by Hau et al. [13] found similar results. They showed a correlation between impairment of breast sensitivity and worse quality of life after BS. The Swedish study group evaluated factors associated with less satisfied patients regarding skin sensitivity. Risk factors were an excision of ≥20% of preoperative breast volume during BCT, a BMI of 25–30 kg/m2, axillary clearance and radiotherapy after surgery. Those factors could not be confirmed in our study. Just a minority of women in our study would choose to undertake a surgical procedure to decrease the scar pain. On the opposite, Gass et al. [14] showed that a majority of patients did not realize how uncomfortable their BC scars would make them feel after surgery. An Irish study of 312 patients after BS revealed that 66% of women thought postsurgical scars would be of importance [15]. This study could show that once patients experienced breast pain in the scar region, they were also dissatisfied with the scar. Only in 62.2% of patients with initial pain, a decrease in pain was observed over time. This leaves 37.8% of patients with persistent pain. In both groups, scar pain was associated with increased restrictions in the arm movement, impairing quality of life. Preventive measures to further decrease these postoperative limitations are of importance. This applies to the medical as well as to the patient side. The majority of our patients could not remember whether postoperative scar care was advised before discharge. Of those who could remember, in only 59.2% (n = 103) active scare care was recommended. There was no information about what kind of scar care was performed. Individual scar care, in a preventive fashion, can be performed by the patient themselves postoperatively. Different methods are available. Using silicone gel sheeting (SGS) is a commonly advertised occlusive dressing applied to reduce the risk of excessive scar formation. This is a semi-occlusive silicone gel sheet combined with a durable silicone membrane [16]. The mechanism of action remains unclear, but it is hypothesized to act via hydration and occlusion of the wound bed and by limiting skin stretching during wound healing [17]. A review of 9 studies found a significant difference between the SGS group and the placebo group (RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.49–0.99; p = 0.04) in preventing the risk of hypertrophic scars when applying SGS [18]. However, it has to be mentioned that most of the included studies had poor quality with high or uncertain risk of biases either in study design or in conduct. An alternative approach to reduce the scarring is the postoperative effect of tape fixation. Atkinson et al. [19] found that paper tape significantly decreased scar volume and is therefore likely to be an effective method for preventing of hypertrophic scarring through its ability to eliminate scar. All of our patients receive routinely tape fixation after BCT and mastectomy. This might explain the high satisfaction rates regarding scarring and sensory disorders. A preventive surgical approach to reduce scarring has been postulated when barbed sutures were used. However, a systemic review including 926 patients could not show a decrease in scarring when using barbed sutures for the closure of dermal layers [20]. Ita et al. [21] could significantly reduce the surgical wound length in BS at 6 weeks without compromising the cosmetic result using the accordion suturing technique. Care should be taken where the incision is made on the breast at the time of surgery. The correct placement of the scar with regard to the tumor location in the breast is of importance for minimizing minimize tissue damage as well as and long-term scarring. Additional information as to skin strain properties of the breast might help surgeons to better select incision location and direction. Surgical incisions performed in areas of high skin strain induces stretching of scars and increased healing times. This might increase incidence of scar repair. Sanchez et al. [22] performed a quantification of gravity-induced skin strain across the breast surface. Their findings showed that preference should be given to medial latitudinal locations for smaller breasted women and lateral latitudinal locations for larger breasted women to reduce tension on surgical incisions. Radiologic images have not been studied for any correlation of breast pain in the BCT group.

Strength and Limitations of the Study

It has been difficult to define surgical techniques more precisely since several surgeons were involved, each deciding how much mobilization was needed in the individual patient, especially in the BCT group. The survey was not validated and relied on self-reported medical questions; however, it addressed clinical meaningful questions, as this topic is poorly discussed in the literature. In the future, efforts should be performed to have long-term follow-up data and behavioral measures on scar care. The survey was conducted at one brief time without any relation to the surgical dates. Patients with poorer health might be underrepresented. The study was not designed to assess perioperative body image or psychological state, which might also influence the perception of the scar and sensitivity disorder. The extend of the axillary surgery could not be evaluated and might have influenced the data on arm mobility. The strengths of this study are the size of the study population providing a valuable patient perspective and achieved a sufficiently high rate of participation. The presented data are in line with a current meta-analysis including 177 studies [23].

Conclusion

This study could demonstrate a prevalence of scar pain of 30.8% after BCT and 34.5% after mastectomy. No relevant risk factors for the development of scar pain or sensory disorders could be identified. A lack of postoperative information about behavioral measures, as well as a low level of actually performed scar care after surgery was found. Information on postoperative scar or skin care was more frequently given in patients with mastectomy. However, patients in both groups neglected scar care after surgery in not inconsiderable numbers. Although we found a very high percentage of postoperative satisfaction with the scar and sensitivity of the breast (87.5% for BCT; 81.8% after mastectomy), increased focus should be on improved information on postoperative care.

Statement of Ethics

The work described has been carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans. It was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Rostock, Germany (A2020–0127). All patients had given their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

All financial support was handled by the authors themselves and the University Hospital Rostock. All authors disclose any financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence (bias) this work.

Author Contributions

M.D. idea, initiator, collection of data, writing, coordination. S.A. collection of data, writing, statistics. B.G. idea, writing. T.R. idea, writing, reviewing. S.H. writing, reviewing, coordination. A.S. collection of data, reviewing. J.S. collection of data, reviewing, statistics.

References

- 1.Voduc KD, Cheang MC, Tyldesley S, Gelmon K, Nielsen TO, Kennecke H. Breast cancer subtypes and the risk of local and regional relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Apr;28((10)):1684–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.9284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onkologie L. (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): S3-Leitlinie Früherkennung, Diagnose, Therapie und Nachsorge des Mammakarzinoms, Version 4.2, 2020 AWMF Registernummer: 032-045OL. http://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/mammakarzinom/ (abgerufen am: 22.042020) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gärtner R, Jensen MB, Nielsen J, Ewertz M, Kroman N, Kehlet H. Prevalence of and factors associated with persistent pain following breast cancer surgery. JAMA. 2009 Nov;302((18)):1985–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bran GM, Goessler UR, Hormann K, Riedel F, Sadick H. Keloids: current concepts of pathogenesis (review) Int J Mol Med. 2009 Sep;24((3)):283–93. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bran GM, Goessler UR, Schardt C, Hormann K, Riedel F, Sadick H. Effect of the abrogation of TGF-beta1 by antisense oligonucleotides on the expression of TGF-beta-isoforms and their receptors I and II in isolated fibroblasts from keloid scars. Int J Mol Med. 2010 Jun;25((6)):915–21. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berman B, Flores F. Recurrence rates of excised keloids treated with postoperative triamcinolone acetonide injections or interferon alfa-2b injections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997 Nov;37((5 Pt 1)):755–7. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pockaj BA, Degnim AC, Boughey JC, Gray RJ, McLaughlin SA, Dueck AC, et al. Quality of life after breast cancer surgery: what have we learned and where should we go next? J Surg Oncol. 2009 Jun;99((7)):447–55. doi: 10.1002/jso.21151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engel J, Kerr J, Schlesinger-Raab A, Sauer H, Hölzel D. Quality of life following breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy: results of a 5-year prospective study. Breast J. 2004 May-Jun;10((3)):223–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2004.21323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arndt V, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H. Quality of life over 5 years in women with breast cancer after breast-conserving therapy versus mastectomy: a population-based study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008 Dec;134((12)):1311–8. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0418-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahlbäck C, Manjer J, Rehn M, Ringberg A. Determinants for patient satisfaction regarding aesthetic outcome and skin sensitivity after breast-conserving surgery. World J Surg Oncol. 2016 Dec;14((1)):303. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-1053-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waljee JF, Hu ES, Newman LA, Alderman AK. Predictors of breast asymmetry after breast-conserving operation for breast cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2008 Feb;206((2)):274–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cetintaş SK, Ozkan L, Kurt M, Saran A, Taşdelen I, Tolunay S, et al. Factors influencing cosmetic results after breast conserving management (Turkish experience) Breast. 2002 Feb;11((1)):72–80. doi: 10.1054/brst.2001.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hau E, Browne L, Capp A, Delaney GP, Fox C, Kearsley JH, et al. The impact of breast cosmetic and functional outcomes on quality of life: long-term results from the St. George and Wollongong randomized breast boost trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013 May;139((1)):115–23. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2508-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gass J, Mitchell S, Hanna M. How do breast cancer surgery scars impact survivorship? Findings from a nationwide survey in the United States. BMC Cancer. 2019 Apr;19((1)):342. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5553-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joyce CW, Murphy S, Murphy S, Kelly JL, Morrison CM. Scar Wars: Preferences in Breast Surgery. Arch Plast Surg. 2015 Sep;42((5)):596–600. doi: 10.5999/aps.2015.42.5.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monstrey S, Middelkoop E, Vranckx JJ, Bassetto F, Ziegler UE, Meaume S, et al. Updated scar management practical guidelines: non-invasive and invasive measures. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014 Aug;67((8)):1017–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suetake T, Sasai S, Zhen YX, Ohi T, Tagami H. Functional analyses of the stratum corneum in scars. Sequential studies after injury and comparison among keloids, hypertrophic scars, and atrophic scars. Arch Dermatol. 1996 Dec;132((12)):1453–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu KC, Luan CW, Tsai YW. Review of Silicone Gel Sheeting and Silicone Gel for the Prevention of Hypertrophic Scars and Keloids. Wounds. 2017 May;29((5)):154–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkinson JA, McKenna KT, Barnett AG, McGrath DJ, Rudd M. A randomized, controlled trial to determine the efficacy of paper tape in preventing hypertrophic scar formation in surgical incisions that traverse Langer's skin tension lines. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005 Nov;116((6)):1648–56. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000187147.73963.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motosko CC, Zakhem GA, Saadeh PB, Hazen A. The Implications of Barbed Sutures on Scar Aesthetics: A Systematic Review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018 Aug;142((2)):337–43. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ita M, Koh K, Butt A, KaimKhani S, Kelly L, O'Sullivan MJ, et al. Evaluation of the effect of the accordion suturing technique on wound lengths in breast cancer surgery: a randomised clinical trial. Ir J Med Sci. 2018 Nov;187((4)):901–6. doi: 10.1007/s11845-018-1772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez A, Mills C, Haake S, Norris M, Scurr J. Quantification of gravity-induced skin strain across the breast surface. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2017 Dec;50:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang K, Yee C, Tam S, Drost L, Chan S, Zaki P, et al. Prevalence of pain in patients with breast cancer post-treatment: A systematic review. Breast. 2018 Dec;42:113–27. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2018.08.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]