Abstract

Background:

Despite national policy recommendations to enhance healthcare access for LGBT+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and those who do not identify as cisgender heterosexual) people, education on LGBT+ issues and needs is still lacking in health and social care curricula. Most of the available resources are focused on primary care, mental health, and sexual health, with little consideration to broader LGBT+ health issues and needs. The limited available educational programmes pertaining to LGBT+ individuals outside the context of sexual or mental health have mainly focused on cancer care or older adults.

Aim:

To support palliative care interdisciplinary teams to provide LGBT+ affirmative care for people receiving and needing palliative and end-of-life care.

Methods:

A 1½-h workshop was developed and evaluated using Kotter’s eight-step process for leading change. Across four hospices, 145 health and social professionals participated in the training. A quasi-experimental non-equivalent groups pre–post-test design was used to measure self-reported levels of knowledge, confidence, and comfort with issues, and needs and terminology related to LGBT+ and palliative care.

Results:

There was a significant increase in the reported levels of knowledge, confidence, and comfort with issues, needs, and terminology related to LGBT+ and palliative care after attending the training. Most participants reported that they would be interested in further training, that the training is useful for their practice, and that they would recommend it to colleagues.

Conclusion:

The project illustrates the importance of such programmes and recommends that such educational work is situated alongside wider cultural change to embed LGBT+-inclusive approaches within palliative and end-of-life care services.

Keywords: education, end of life, gender minorities, health equity, LGBTQ, palliative care, sexual minorities

Introduction

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and those who do not identify as cisgender heterosexual (LGBT+) individuals represent a significant underrepresented and underprivileged group, with distinct healthcare needs. 1 There is evidence that the prevalence of ongoing discrimination and marginalisation on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity directly affects the health and well-being of many LGBT+ people. 2 LGBT+ people report worse healthcare experiences 3 and poorer general health, 4 have a higher life-time risk for certain types of cancer,5 –7 are less likely to attend routine health screening, and are more likely to present with advanced illness compared with cisgender heterosexual people.1,8 Moreover, LGBT+ people are more likely to experience mental health problems and engage in risk behaviours, which are attributed to stress from stigma, discrimination, and marginalisation.9 –12 Stigma, discrimination, and marginalisation can have a significant impact on the person’s health and well-being, leading to minority stress. 13 The minority stress model illustrates the harmful impact of internalised homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia.14,15 The negative societal attitude towards an LGBT+ identity places the LGBT+ individual at an increased risk of experiencing poor psychosocial outcomes, including anxiety, depression, substance use disorder, and suicidality.11,16,17

Much of the literature indicates that LGBT+ people are less likely to access health and social care services especially when they are most vulnerable, 18 such as when needing palliative and end-of-life care.8,19,20 This is mainly associated with lack or biased understanding of LGBT+ distinct needs, overpowering heteronormative behaviours, discrimination, homophobia, and transphobia within the health services.8,20,21 Evidence suggests that some care professionals discriminate against patients based on their sexual orientation and gender identity. 22 This is supported by the findings of an international survey which illustrated that heterosexual healthcare providers implicitly favour heterosexual individuals on gay men and lesbian women. 23 Previous negative experiences with health services due to discrimination and stigmatisation result in delayed or no access to care and timely treatments,24,25 resulting in poorer health outcomes and worse healthcare experiences. 4 Furthermore, LGBT+ individuals expressed concerns related to bereavement, including but not limited to, unrecognised needs of the bereaved partner, lack of acknowledgement of the loss, and exclusion of the ‘family of choice’ from decisions and advance care plans. 26 Therefore, LGBT+ individuals are at a higher risk of experiencing disenfranchised grief 27 and suboptimal bereavement outcomes. 26

Despite national policy recommendations to enhance healthcare access and provision for LGBT+ people, 3 lack of awareness about the heteronormative practices that can exclude LGBT+ persons persist. 28 To promote an improved healthcare experience and person-centred care, it is crucial to have responsive and inclusive health services, led by knowledgeable and skilled healthcare professionals. Therefore, healthcare organisations and higher education providers have an important role in supporting the development of LGBT+-inclusive education programmes. Most of the available resources are focused on mental health and sexual health,29,30 with little consideration to the broader LGBT+ health issues and needs. While a wide range of educational resources are available for the workforce providing care for people with advanced illness, very few consider the specific needs of the LGBT+ population. The limited available educational programmes pertaining to LGBT+ individuals outside the context of sexual or mental health have mainly focused on cancer care21,31 or older adults. 18

Aim

The aim of the project was to support palliative care interdisciplinary teams to provide LGBT+ affirmative care for people receiving and needing palliative and end-of-life care:

Develop an education programme for health and social care professionals providing palliative and end-of-life care for LGBT+ people.

Evaluate the education programme based on self-reported knowledge of general LGBT+ issues and needs, knowledge of LGBT+ issues and needs specific to palliative and end-of-life care, confidence in providing palliative and end-of-life care for LGBT+ people, comfort with using terminology related to sexual and gender identities, usefulness of the training to practice, interest in further training, and whether participants would recommend the training to others.

Methods

Project development

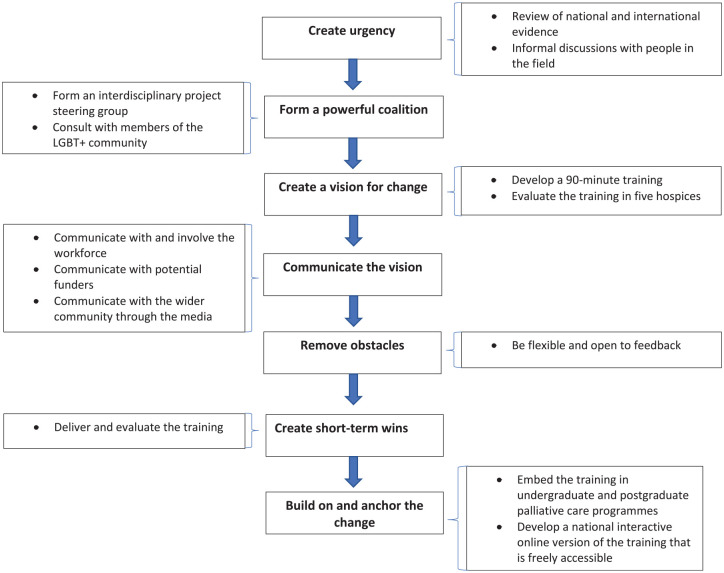

The project was developed using Kotter’s eight-step process for leading change, which provides the following roadmap to initiate, manage, and sustain change: create an urgency, form a powerful coalition, create a vision for change, remove obstacles, create short-term wins, and build and anchor the change (Figure 1). 32 The nexus of the project was based on the Care Quality Commission (CQC) report on inequalities in end-of-life care, 19 which led to informal discussions with stakeholders to create an urgency for change. The CQC’s thematic review of inequalities in end-of-life care demonstrated that service providers and commissioners do not have a good understanding of the different groups within the communities that they serve. The review also highlighted that many service commissioners believed that sexual orientation and gender identity have no impact on palliative and end-of life care service access and provision. In addition, there was limited evidence that service providers are engaging with the LGBT+ community and considering their specific needs. As a result, an interdisciplinary task group was formed to provide leadership and guide the development of the programme and implementation of the project. The task group consisted of people in key leadership positions in hospice and palliative care settings, members of the LGBT+ community, clinicians, service managers, commissioners, and academics.

Figure 1.

Developing the project using Kotter’s eight-step change model.

The project developed a 1½-h workshop which consisted of an informative presentation and interactive discussion. The content of the curriculum focused on terminology and definitions related to gender and sexual identities; general LGBT+ issues and needs; LGBT+ issues and needs relevant to palliative and end-of-life care; and approaches to providing LGBT+-affirmative care at individual and organisational levels. The format of the training was interactive and included the trailer of Gen Silent documentary, which follows the lives of older LGBT people in the Boston area. The programme was designed to meet the needs of health and social care professionals from diverse backgrounds, and to provide a basic level of knowledge and understanding of LGBT+ issues and needs in the context of living with advanced illness.

Project implementation

The delivery of the programme began in January 2017. Each workshop was delivered by one trainer and one facilitator. The workshop was delivered to and evaluated by 145 participants at four hospices across London and Essex, UK. The target population was health and social care professionals working with people living with advanced illness. The aim of the education programme was to increase health and social care professionals’ awareness about the specific issues and needs of LGBT+ people and their families and partners living with advanced illness. It was also aimed at providing participants with strategies for recognising barriers to inclusion and develop the skills required to provide LGBT+ -inclusive service using a palliative care approach.

Project evaluation

The project evaluation started in January 2017 and ended in July 2017. The project employed a quasi-experimental non-equivalent groups pre–post-test design. It measured the overall self-reported knowledge of general LGBT+ issues and needs, knowledge of LGBT+ issues and needs specific to palliative and end-of-life care, confidence in providing palliative and end-of-life care for LGBT+ people, and comfort with using terminology related to sexual and gender identities. Participants (N = 145) were asked if the training was useful for their practice, if they would recommend it to colleagues, and if they would be interested in further training on the topic. Participants completed self-report questionnaire before and after the training. Age was collected using five age groups (see Table 1). The distribution of the evaluation variables was compared over the different age groups, which identified that the main differences were between the oldest two groups against the younger three groups. Therefore, for the purposes of comparative analysis, age was re-coded into two groups, ‘18 to 49’ and ‘50 and over’. Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics v.26. The statistical tests used were appropriate to the data type, study design, distribution, and included descriptive statistics, chi-square, and Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test.

Table 1.

Clinical role and demographics.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| 145 | 100 | |

| Clinical role | ||

| Chaplain | 2 | 1.38 |

| Complementary therapist | 1 | 0.69 |

| Counsellor | 23 | 15.86 |

| Doctor | 10 | 6.90 |

| Healthcare assistant | 21 | 14.48 |

| Nurse | 57 | 39.31 |

| Occupational therapist | 4 | 2.76 |

| Others | 15 | 10.34 |

| Physiotherapist | 5 | 3.45 |

| Psychologist | 2 | 1.38 |

| Social worker | 5 | 3.45 |

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 8 | 5.52 |

| 30–39 | 15 | 10.34 |

| 40–49 | 45 | 31.03 |

| 50–59 | 64 | 44.14 |

| 60 and over | 13 | 8.97 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 9 | 6.21 |

| Female | 136 | 93.79 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Lesbian | 2 | 1.38 |

| Bisexual | 1 | 0.69 |

| Heterosexual | 141 | 97.24 |

| Pansexual | 1 | 0.69 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Black/Black British | 5 | 3.45 |

| Asian/Asian British | 3 | 2.07 |

| Caucasian/White British | 131 | 90.34 |

| Other | 6 | 4.14 |

Results

Table 1 summarises the demographic profile of participants. The cohort consisted of 145 participants, of which 136 (93.8%) reported their gender as female. The cohort included a range of clinical roles, with the most frequent being nurses (n = 57, 39.3%), followed by counsellors (n = 23, 15.8%) and healthcare assistants (n = 21, 14.5%). A total of 141 (97.2%) reported their sexual orientation as heterosexual, and 131 (90.3%) reported their ethnicity as Caucasian/White British.

Table 2 shows the comparison of the overall knowledge of general LGBT+ issues and needs and overall knowledge of LGBT+ issues and needs in palliative and end-of-life care, confidence in providing palliative and end-of-life care for LGBT+ people, and comfort with using terms related to sexual and gender identities before and after the training, using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. There was a significant increase in the reported overall knowledge of general LGBT+ issues and needs (Z = −9.135; p < 0.001, overall knowledge of LGBT+ issues and needs in palliative and end-of-life care (Z = −10.019; p < 0.001), confidence in providing palliative and end-of-life care for LGBT+ people (Z = −7.957; p < 0.001), and comfort with using terms related to gender and sexual identities (Z = −3.699; p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Knowledge, confidence, and comfort pre- and post-session.

| Pre-session | Post-session | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| 145 | 100.00 | 145 | 100.00 | ||

| Knowledge of general LGBT + issues and needs | |||||

| p < 0.001 | |||||

| Not knowledgeable | 48 | 33.10 | 1 | 0.69 | (Z = −9.135) |

| Somewhat knowledgeable | 84 | 57.93 | 73 | 50.34 | |

| Knowledgeable | 13 | 8.97 | 71 | 48.97 | |

| Knowledge of LGBT+ issues and needs in palliative and end-of-life care | |||||

| p < 0.001 | |||||

| Not knowledgeable | 81 | 55.86 | 2 | 1.38 | (Z = −10.019) |

| Somewhat knowledgeable | 60 | 41.38 | 71 | 48.97 | |

| Knowledgeable | 4 | 2.76 | 72 | 49.66 | |

| Confidence in providing palliative and end-of-life care for LGBT+ people | |||||

| p < 0.001 | |||||

| Not confident | 48 | 33.1 | 5 | 3.45 | (Z = −7.957) |

| Somewhat confident | 62 | 42.8 | 56 | 38.62 | |

| Confident | 35 | 24.1 | 84 | 57.93 | |

| Comfort with using terms related to sexual/gender identity | |||||

| p < 0.001 | |||||

| Not comfortable | 8 | 5.52 | 1 | 0.69 | (Z = −3.699) |

| Somewhat comfortable | 30 | 20.69 | 20 | 13.79 | |

| Comfortable | 107 | 73.79 | 124 | 85.52 | |

LGBT+: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and those who do not identify as cisgender heterosexual.

The reported levels of knowledge, confidence, and comfort were compared by age groups. To avoid sample size issues, age was collapsed into two categories, ‘18 to 49’ and ‘50 and over’. These were analysed in two ways. First, reported ratings before and after the training were directly compared within each age group. Second, a comparison between the two age groups before the training was made and the same comparison was made after the training. The results of the first comparative analysis by age can be seen in Table 3, which shows that the levels of knowledge, confidence, and comfort significantly improved post-training within all age groups. The second comparative method by age showed that the overall knowledge of LGBT+ issues and needs in palliative and end-of-life care was significantly higher before the training in the age group ‘50 and over’ than the younger age group (χ2 = 7.364, df = 2, p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Knowledge, confidence, and comfort pre- and post-session within age groups ‘18 to 49’ and ‘50 and over’.

| Age in two groups | p value | Age in two groups | p value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-session | Post-session | Pre-session | Post-session | |||||||

| 18–49 | 18–49 | 50 and over | 50 and over | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Knowledge of general LGBT+ issues and needs | ||||||||||

| Not knowledgeable | 27 | 39.7% | 0 | 0.0% | p < 0.001 | 21 | 27.3% | 1 | 1.3% | p < 0.001 |

| Somewhat knowledgeable | 33 | 48.5% | 32 | 47.1% | 51 | 66.2% | 41 | 53.2% | ||

| Knowledgeable | 8 | 11.8% | 36 | 52.9% | 5 | 6.5% | 35 | 45.5% | ||

| Knowledge of LGBT+ issues and needs in palliative and end-of-life care | ||||||||||

| Not knowledgeable | 46 | 67.6% | 0 | 0.0% | p < 0.001 | 35 | 45.5% | 2 | 2.6% | p < 0.001 |

| Somewhat knowledgeable | 21 | 30.9% | 33 | 48.5% | 39 | 50.6% | 38 | 49.4% | ||

| Knowledgeable | 1 | 1.5% | 35 | 51.5% | 3 | 3.9% | 37 | 48.1% | ||

| Confidence in providing palliative and end-of-life care for LGBT+ people | ||||||||||

| Not confident | 26 | 38.2% | 3 | 4.4% | p < 0.001 | 22 | 28.6% | 2 | 2.6% | p < 0.001 |

| Somewhat confident | 27 | 39.7% | 26 | 38.2% | 35 | 45.5% | 30 | 39.0% | ||

| Confident | 15 | 22.1% | 39 | 57.4% | 20 | 26.0% | 45 | 58.4% | ||

| Comfort with using terms related to sexual/gender identity | ||||||||||

| Not comfortable | 3 | 4.4% | 0 | 0.0% | p < 0.005 | 5 | 6.5% | 1 | 1.3% | p < 0.05 |

| Somewhat comfortable | 19 | 27.9% | 12 | 17.6% | 11 | 14.3% | 8 | 10.4% | ||

| Comfortable | 46 | 67.6% | 56 | 82.4% | 61 | 79.2% | 68 | 88.3% | ||

LGBT+: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and those who do not identify as cisgender heterosexual.

Table 4 shows that most participants rated the overall quality of the training as ‘excellent’ (n = 115, 79.3%), reported that the training was useful for their practice (n = 143, 99.3%), and that they would be interested in further training (n = 138, 95.1%). All participants reported that they would recommend this training to others.

Table 4.

Quality and usefulness of the training, interest in the training, and recommending the training to others.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| 145 | 100 | |

| Overall quality of the training | ||

| Excellent | 115 | 79.31 |

| Good | 28 | 19.31 |

| Poor | 0 | 0.00 |

| Usefulness of the training to own practice | ||

| Yes | 143 | 99.31 |

| No | 1 | 0.69 |

| Interest in further training | ||

| No | 6 | 4.14 |

| Yes | 138 | 95.17 |

| Recommend the training to others | ||

| Yes | 145 | 100.00 |

| No | 0 | 0.00 |

Discussion

While there are commonalities between LGBT+ and cisgender heterosexual individuals in relation to their needs being met by palliative and end-of-life care, as identified above, there are additional barriers facing LGBT+ people and evidence that the care that LGBT+ people receive is suboptimal. This may be due to LGBT+ people fearing disclosure of key aspects of their identity which may negatively impact their care. Much of the literature indicates an association between positive psychosocial adjustment and a person being able to disclose their sexual identity.33,34 As a result, individuals who choose to hide their sexual identity due to fear from discrimination may not have the same potential for positive psychosocial functioning compared with those who do not face similar challenges. 35 Suboptimal care may also be due to healthcare providers assuming heterosexuality, negative attitudes, and behaviour towards people who are identified or perceived as being LGBT+. Awareness of and addressing these potential barriers are largely dependent on the knowledge and attitudes of healthcare professionals, hence the importance of training to facilitate high-quality provision of care for LGBT+ people in need of palliative and end-of-life care. The care of the dying is said to be a good indicator of the care for all sick and vulnerable people. 36 It is a crucial time to deliver good-quality care to enable LGBT+ people to live and die in comfort and with dignity because, to paraphrase Dame Cicely Saunders (recognised as the founder of the modern hospice movement), how someone dies remains a lasting memory for the individual’s friends, family, and the teams involved in their care.37 All individuals should be afforded care, compassion, and dignity through life and at the end of life. Addressing the distinctly complex and multiple needs of LGBT+ people hold the potential to develop non-discriminatory services that will benefit all.

To our knowledge, this project developed the first education programme for health and social care professionals in the United Kingdom, focusing on palliative and end-of-life care for people with diverse sexual orientations and gender identities. A crucial component in the development of this programme was the direct involvement of members of the LGBT+ community as active contributors to the development of the curriculum and implementation of the project. As such, values, needs, and preferences of people from diverse sexual orientations and gender identities were represented to inform the planning, development, and implementation of the project; with the intended goal of developing a curriculum that will support health and social care professionals to provide an LGBT+-affirmative palliative and end-of-life care.

The findings demonstrate that there is a need for mainstream palliative and end-of-life care education programmes to include topics related to people with diverse sexual orientations and gender identities. Although the results demonstrate that participants were more knowledgeable, confident, and comfortable with issues, needs, and terminology related to LGBT+ and palliative care after the training, the majority expressed a desire for further training and that they would recommend the education programme to colleagues. As a result, and to build on and anchor the change, an online interactive version of the training was developed for the national e-learning programme, End of Life Care for All (e-ELCA), which is freely accessible by all health and social care professionals working in the National Health Service and hospices across England. In addition, the training became embedded as a core element in the interdisciplinary undergraduate and postgraduate programmes in palliative and end-of-life care at London South Bank University.

Westwood and Knocker 38 highlight some limitations to this type of training. They argue that there are still wider issues to be addressed, such as organisational issues within the workplaces of healthcare professionals and socio-cultural systematic disadvantage. 38 Furthermore, it is challenging to fully address the diversity among and between LGBT+ individuals in a short educational programme. The small sample size and the lack of diversity among participants, where the majority identified as White cisgender heterosexual females, limits the generalisability of the findings. The evaluation of the project consisted of a single-item measure, and it was beyond the scope of the project to assess the impact of the training on practice. Further research evaluating the training using reliable and valid measures and exploring the effectiveness of such training programmes on practice is needed. Nevertheless, our results indicate that this project is a positive example of partnership working between stakeholders to enhance care of LGBT+ people with advanced illness. It has been presented in a national report as a case study of best practice. 39 In addition, this project provides an example of how such initiatives can be adapted and replicated in different contexts and countries to achieve a wider impact. For example, the curriculum was adapted to the Lebanese context and piloted in Lebanon as part of the Lebanese Medical Association for Sexual Health’s annual LGBT+ Health Week. The results of the pilot were positive, and a key finding was the desire for further training and to learn more. 40

Conclusion

The project provides an example of how partnership working between different stakeholders can help respond to a real need within the health services to positively impact the care provided to marginalised populations. It shows how such initiatives can be adapted and replicated in different contexts to achieve a wider impact. Our findings demonstrate that participants developed a better awareness of the additional issues that may face their LGBT+ patients and feel better equipped with the skills, knowledge, and tools to discuss personalised care and help LGBT+ people make informed choices in a palliative and end-of-life care context. This illustrates the importance of such programmes and recommends that such educational work needs to be situated alongside wider cultural change to embed LGBT+-inclusive approaches within palliative and end-of-life care services.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients who inform their work, and Saint Francis Hospice and members of the task force who supported the project.

Footnotes

Author contributions: C.C. conceived the idea, designed and implemented the project, and conducted data collection. K.G. led on statistical analysis with guidance from C.C. and K.A. C.C., K.G., and K.A. drafted the initial manuscript and C.C. contributed to the final version of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the School of Health and Social Care School Ethics Panel, London South Bank University, London, UK (HSCSEP/16/11). All participants provided written informed consent.

ORCID iD: Claude Chidiac  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9769-8449

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9769-8449

Contributor Information

Claude Chidiac, Department of Palliative Care, Homerton University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London E9 6SR, UK.

Kate Grayson, Statistics By Design, Blackwater, UK.

Kathryn Almack, School of Health and Social Work, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, UK.

References

- 1. Cochran SD, Björkenstam C, Mays VM. Sexual orientation and all-cause mortality among US adults aged 18 to 59 years, 2001-2011. Am J Public Health 2016; 106: 918–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Almack K. Dying, death and bereavement. In: Goldberg A. (ed.) The SAGE encyclopedia of LGBTQ studies. New York: SAGE, 2016, pp. 342–347. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Government Equalities Office. LGBT Action Plan: improving the lives of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/721367/GEO-LGBT-Action-Plan.pdf (2018, accessed 15 February 2021).

- 4. Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Burkhart Q, et al. Sexual minorities in England have poorer health and worse health care experiences: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med 2015; 30: 9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cochran SD, Mays VM. Risk of breast cancer mortality among women cohabiting with same sex partners: findings from the National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2003. J Womens Health 2012; 21: 528–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boehmer U, Ozonoff A, Miao X. An ecological analysis of colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: differences by sexual orientation. BMC Cancer 2011; 11: 400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boehmer U, Ozonoff A, Miao X. An ecological approach to examine lung cancer disparities due to sexual orientation. Public Health 2012; 126: 605–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bristowe K, Hodson M, Wee B, et al. Recommendations to reduce inequalities for LGBT people facing advanced illness: ACCESSCare national qualitative interview study. Palliat Med 2018; 32: 23–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mayer KH, Bradford JB, Makadon HJ, et al. Sexual and gender minority health: what we know and what needs to be done. Am J Public Health 2008; 98: 989–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick WB, et al. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction 2009; 104: 1333–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McCann E, Sharek D. Mental health needs of people who identify as transgender: a review of the literature. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2016; 30: 280–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McCann E, Brown MJ. The mental health needs and concerns of older people who identify as LGBTQ+: a narrative review of the international evidence. J Adv Nurs 2019; 75: 3390–3403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Meyer IH. Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers 2015; 2: 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- 14. McCann E, Brown M. The inclusion of LGBT+ health issues within undergraduate healthcare education and professional training programmes: a systematic review. Nurse Educ Today 2018; 64: 204–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the minority stress model. Prof Psychol Res Pract 2012; 43: 460–467. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bariola E, Lyons A, Leonard W, et al. Demographic and psychosocial factors associated with psychological distress and resilience among transgender individuals. Am J Public Health 2015; 105: 2108–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chidiac C, Connolly M. Considering the impact of stigma on lesbian, gay and bisexual people receiving palliative and end-of-life care. Int J Palliat Nurs 2016; 22: 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gendron T, Maddux S, Krinsky L, et al. Cultural competence training for healthcare professionals working with LGBT older adults. Educ Gerontol 2013; 39: 454–463. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Care Quality Commission. A different ending: addressing inequalities in end of life care. Good practice case studies, 2016, https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20160505%20CQC_EOLC_GoodPractice_FINAL_2.pdf

- 20. Harding R, Epiphaniou E, Chidgey-Clark J. Needs, experiences, and preferences of sexual minorities for end-of-life care and palliative care: a systematic review. J Palliat Med 2012; 15: 602–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reygan FCG, D’Alton P. A pilot training programme for health and social care professionals providing oncological and palliative care to lesbian, gay and bisexual patients in Ireland. Psychooncology 2013; 22: 1050–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Röndahl G, Innala S, Carlsson M. Nursing staff and nursing students’ attitudes towards HIV-infected and homosexual HIV-infected patients in Sweden and the wish to refrain from nursing. J Adv Nurs 2003; 41: 454–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sabin JA, Riskind RG, Nosek BA. Health care providers’ implicit and explicit attitudes toward lesbian women and gay men. Am J Public Health 2015; 105: 1831–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dahlhamer JM, Galinsky AM, Joestl SS, et al. Barriers to health care among adults identifying as sexual minorities: a US national study. Am J Public Health 2016; 106: 1116–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sinding C, Barnoff L, Grassau P. Homophobia and heterosexism in cancer care: the experiences of lesbians. Can J Nurs Res 2004; 36: 170–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bristowe K, Marshall S, Harding R. The bereavement experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or trans* people who have lost a partner: a systematic review, thematic synthesis and modelling of the literature. Palliat Med 2016; 30: 730–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McNutt B, Yakushko O. Disenfranchised grief among lesbian and gay bereaved individuals. J LGBT Issues Couns 2013; 7: 87–116. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Care Quality Commission. A different ending: addressing inequalities in end of life care, https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20160505CQC_EOLC_2016_OVERVIEW_FINAL2.pdf (2016, accessed 21 January 2021).

- 29. National Health Service. Sexual health for gay and bisexual men. NHS, https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/sexual-health/sexual-health-for-gay-and-bisexual-men/ (2019, accessed 16 February 2021).

- 30. National Health Service. Help for mental health problems if you’re LGBT, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/stress-anxiety-depression/mental-health-issues-if-you-are-gay-lesbian-or-bisexual/ (2020, accessed 16 February 2021).

- 31. National LGBT Cancer Network. Cultural competency training, https://cancer-network.org/cultural-competency-training/ (accessed 16 February 2021).

- 32. Kotter JP. Leading change: why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review, January 2007, pp. 92–107. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Riggle EDB, Rostosky SS, Danner F. LGB identity and eudaimonic well-being in midlife. J Homosex 2009; 56: 786–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Different patterns of sexual identity development over time: implications for the psychological adjustment of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. J Sex Res 2011; 48: 3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Muraco A. Aging and sexual orientation: a 25-year review of the literature. Res Aging 2010; 32: 372–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Department of Health. End of life care strategy: promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/136431/End_of_life_strategy.pdf (2008, accessed 27 February 2021).

- 37. Saunders C. Pain and impending death. In: Wall PD and Melzak R (eds) Textbook of pain. Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingstone, 1989, pp. 624–631.

- 38. Westwood SL, Knocker S. One-day training courses on LGBT* awareness: are they the answer? In: Westwood S, Price E. (eds) Lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans* individuals living with dementia: concepts, practice and rights. London: Routledge, 2016, pp. 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hospice UK. Care committed to me: delivering high quality, personalised palliative and end of life care for Gypsies and Travellers, LGBT people and people experiencing homelessness, https://www.hospiceuk.org/docs/default-source/Policy-and-Campaigns/briefings-and-consultations-documents-and-files/care_committed_to_me_web.pdf?sfvrsn=0 (2018, accessed 27 February 2021).

- 40. Chidiac C. First steps: health and social care professionals beginning to address the palliative and end of life care needs of people with diverse gender identities and sexual orientations in Lebanon. Sexualities. Epub ahead of print 15 June 2020. DOI: 10.1177/1363460720932380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]