Abstract

Background

Primary care is an important setting in which to treat tobacco addiction. However, the rates at which providers address smoking cessation and the success of that support vary. Strategies can be implemented to improve and increase the delivery of smoking cessation support (e.g. through provider training), and to increase the amount and breadth of support given to people who smoke (e.g. through additional counseling or tailored printed materials).

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of strategies intended to increase the success of smoking cessation interventions in primary care settings.

To assess whether any effect that these interventions have on smoking cessation may be due to increased implementation by healthcare providers.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialized Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, and trial registries to 10 September 2020.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster‐RCTs (cRCTs) carried out in primary care, including non‐pregnant adults. Studies investigated a strategy or strategies to improve the implementation or success of smoking cessation treatment in primary care. These strategies could include interventions designed to increase or enhance the quality of existing support, or smoking cessation interventions offered in addition to standard care (adjunctive interventions). Intervention strategies had to be tested in addition to and in comparison with standard care, or in addition to other active intervention strategies if the effect of an individual strategy could be isolated. Standard care typically incorporates physician‐delivered brief behavioral support, and an offer of smoking cessation medication, but differs across studies. Studies had to measure smoking abstinence at six months' follow‐up or longer.

Data collection and analysis

We followed standard Cochrane methods. Our primary outcome ‐ smoking abstinence ‐ was measured using the most rigorous intention‐to‐treat definition available. We also extracted outcome data for quit attempts, and the following markers of healthcare provider performance: asking about smoking status; advising on cessation; assessment of participant readiness to quit; assisting with cessation; arranging follow‐up for smoking participants. Where more than one study investigated the same strategy or set of strategies, and measured the same outcome, we conducted meta‐analyses using Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effects methods to generate pooled risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Main results

We included 81 RCTs and cRCTs, involving 112,159 participants. Fourteen were rated at low risk of bias, 44 at high risk, and the remainder at unclear risk.

We identified moderate‐certainty evidence, limited by inconsistency, that the provision of adjunctive counseling by a health professional other than the physician (RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.55; I2 = 44%; 22 studies, 18,150 participants), and provision of cost‐free medications (RR 1.36, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.76; I2 = 63%; 10 studies,7560 participants) increased smoking quit rates in primary care. There was also moderate‐certainty evidence, limited by risk of bias, that the addition of tailored print materials to standard smoking cessation treatment increased the number of people who had successfully stopped smoking at six months' follow‐up or more (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.59; I2 = 37%; 6 studies, 15,978 participants).

There was no clear evidence that providing participants who smoked with biomedical risk feedback increased their likelihood of quitting (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.41; I2 = 40%; 7 studies, 3491 participants), or that provider smoking cessation training (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.41; I2 = 66%; 7 studies, 13,685 participants) or provider incentives (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.34; I2 = 0%; 2 studies, 2454 participants) increased smoking abstinence rates. However, in assessing the former two strategies we judged the evidence to be of low certainty and in assessing the latter strategies it was of very low certainty. We downgraded the evidence due to imprecision, inconsistency and risk of bias across these comparisons. There was some indication that provider training increased the delivery of smoking cessation support, along with the provision of adjunctive counseling and cost‐free medications. However, our secondary outcomes were not measured consistently, and in many cases analyses were subject to substantial statistical heterogeneity, imprecision, or both, making it difficult to draw conclusions.

Thirty‐four studies investigated multicomponent interventions to improve smoking cessation rates. There was substantial variation in the combinations of strategies tested, and the resulting individual study effect estimates, precluding meta‐analyses in most cases. Meta‐analyses provided some evidence that adjunctive counseling combined with either cost‐free medications or provider training enhanced quit rates when compared with standard care alone. However, analyses were limited by small numbers of events, high statistical heterogeneity, and studies at high risk of bias. Analyses looking at the effects of combining provider training with flow sheets to aid physician decision‐making, and with outreach facilitation, found no clear evidence that these combinations increased quit rates; however, analyses were limited by imprecision, and there was some indication that these approaches did improve some forms of provider implementation.

Authors' conclusions

There is moderate‐certainty evidence that providing adjunctive counseling by an allied health professional, cost‐free smoking cessation medications, and tailored printed materials as part of smoking cessation support in primary care can increase the number of people who achieve smoking cessation. There is no clear evidence that providing participants with biomedical risk feedback, or primary care providers with training or incentives to provide smoking cessation support enhance quit rates. However, we rated this evidence as of low or very low certainty, and so conclusions are likely to change as further evidence becomes available. Most of the studies in this review evaluated smoking cessation interventions that had already been extensively tested in the general population. Further studies should assess strategies designed to optimize the delivery of those interventions already known to be effective within the primary care setting. Such studies should be cluster‐randomized to account for the implications of implementation in this particular setting. Due to substantial variation between studies in this review, identifying optimal characteristics of multicomponent interventions to improve the delivery of smoking cessation treatment was challenging. Future research could use component network meta‐analysis to investigate this further.

Plain language summary

Are there ways to improve stop‐smoking treatment in primary care to help more people to quit smoking?

What is stop‐smoking treatment in primary care?

Primary care, also known as family medicine or general practice, is where people go to see a health professional for mostly day‐to‐day health issues. It is one of the best places for people who smoke tobacco to get help to quit. When people visit primary care they may be asked if they smoke. If they do, they may then be helped to quit, typically through counseling and medications.

Why we did this Cochrane Review

Support to stop smoking in primary care is not always delivered well or consistently. Health providers may be unsure how best to deliver treatment, may have limited time to deliver it, or lack the resources needed. Ways to improve the delivery and success of stop‐smoking support in primary care have been suggested. Some of these are designed to make sure the treatment already available is delivered often and well, e.g. training providers on how best to help people quit, and some are designed to increase the support available for participants, e.g. providing additional counseling and printed materials. Our aim was to look at which of these approaches works best on their own or together.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that looked at ways to improve standard stop‐smoking support within primary care, and where the treatments people received were decided at random.

We wanted to find out:

‐ how many people were asked about their smoking and provided with advice and support;

‐ how many people tried to quit smoking; and

‐ how many people stopped smoking for at least six months.

We included evidence published to 10th September 2020.

What we found

We found 81 studies including 112,159 smokers in primary care patients. Studies looked at many ways to improve the delivery and success of stop‐smoking support in primary care. Some looked at just one strategy, and some looked at two or more in combination. More than one study looked at each of the following individual strategies: additional counseling; free medications; feedback to participants on markers of their individual health risk linked to smoking; printed materials tailored to participants; health provider training; and rewards to health providers for providing support.

Most studies took place in Europe (39 studies) and the USA (26 studies).

What are the results of our review?

More people probably stop smoking for at least six months when they are given additional counseling (22 studies, 18,150 people), free stop‐smoking medications (10 studies, 7560 people), or printed materials tailored to them (6 studies, 15,978 people), as part of stop‐smoking support in primary care. We are uncertain whether providing people with feedback on markers of their individual health risk, providing healthcare providers with training, or with rewards for providing stop‐smoking support, help more people to quit.

Thirty‐four studies looked at more than one strategy to improve stop‐smoking treatment in primary care. Combinations differed greatly across studies, with different levels of success, and it was not possible to draw conclusions on what worked best.

There was not enough information to help us clearly understand whether there were increases in the amount of stop‐smoking support provided or increases in the numbers of people making a quit attempt.

How reliable are these results?

For some of our results the data varied widely, for some there was not enough data, and in some cases there were quality issues with included studies.

We are moderately confident that people are more likely to quit smoking if someone in addition to the primary care doctor also provides stop‐smoking counseling, if free stop‐smoking medications are provided, or if printed materials tailored to the participant are provided as part of stop‐smoking support offered in primary care. However, results might change as further evidence becomes available.

We are less confident about the effectiveness of providing people with feedback on markers of their individual health risk, giving healthcare providers training on stop‐smoking treatments, or giving healthcare providers rewards for giving stop‐smoking support. These results are likely to change when more evidence becomes available.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Tobacco use is the leading cause of premature death worldwide (World Health Organization 2017). From a chronic illness perspective, people who smoke have a 50% to 70% greater chance of dying from stroke or coronary heart disease than people who do not, and 85% of cancers of the trachea, bronchus, and lung are directly attributable to tobacco use (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2014). Tobacco use is also a leading risk factor for other major causes of death, including 16 types of cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and lower respiratory tract infections (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2014; World Health Organization 2017).

There is overwhelming evidence to support both the health and economic benefits of smoking cessation. If a person smokes, supporting them with quitting is the single most effective intervention a clinician can provide to reduce the risk of premature disease, disability and death (Fiore 2008; Royal College of Physicians 2018; Tengs 1995). Quitting smoking reduces the excess risk of smoking‐related coronary heart disease by approximately 50% within one year, and to normal levels within five years (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2014). Smoking cessation is also considered to be among the most cost‐effective preventive interventions available to clinicians and health systems (Tengs 1995; Cromwell 1997; Roncker 2005; Franco 2007; Gaziano 2007; Royal College of Physicians 2018; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2020).

Description of the intervention

Primary care practice, also known as family medicine or general practice, has been identified as an important setting for intervening with tobacco users because of the large reach of primary care settings, the long‐term relationships with patients and their role in addressing disease prevention (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2020; World Health Organization 2020).

Evidence‐based guidelines for the delivery of tobacco treatment emphasize the important role of primary care clinicians in tobacco treatment delivery (Verbiest 2017). The World Health Organization (WHO) and other international authorities have called for smoking cessation to be integrated into primary health care globally, as it is seen as the most suitable health system 'environment' for providing advice and support on smoking cessation (Fiore 2008; World Health Organization 2008; World Health Organization 2020; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2020). Specifically, the combination of behavioral support and stop‐smoking pharmacotherapy have been shown to significantly enhance long‐term cessation rates; it follows that increasing the use of these evidence‐based treatments is an important target (Stead 2016). While models of delivery differ across international settings, clinical practice guidelines recommend that primary care providers support people who smoke with quitting by: asking them about their smoking status, providing advice on quitting to those identified as smoking, and supporting cessation by offering behavioral counseling and/or pharmaceutical treatment or both when smokers identify themselves as ready to quit (Verbiest 2017). See Secondary outcomes below for more information.

However, there is a well‐documented ‘practice gap’ in the rates at which smoking cessation is addressed by practitioners in clinical settings. International studies have documented that between 40% and 70% of people who smoke report having received cessation advice from their physician (Bartsch 2016; Papadakis 2014; Reid 2019; World Health Organization 2020). While practitioners tend to deliver advice to quit at moderate rates, studies have shown that the rates of providing specific assistance (i.e. behavioral counseling, printed self‐help materials, stop‐smoking medications, or follow‐up support) are much lower (Bartsch 2016; Papadakis 2014). When it is offered, the amount and breadth of assistance is also likely to differ considerably across practices, which may have an effect on rates of smoking cessation.

How the intervention might work

Several barriers to optimal cessation practice in primary care have been identified at the patient, provider, and practice levels (Martin‐Cantera 2020; Van Rossem 2015; Vogt 2005; Young 2001). Identified barriers include a lack of knowledge and skills among providers, provider attitudes and perceptions, lack of time and organizational supports, and a lack of patient motivation and other patient‐level factors. Interventions which address these barriers are expected to enhance rates of tobacco treatment delivery by primary care providers, increase the use of evidence‐based stop smoking treatment by patients, and subsequently lead to enhanced quit rates among patients identified in primary care (Van Rossem 2015; Martin‐Cantera 2020; Vogt 2005; Young 2001).

Strategies to improve the delivery of standard smoking cessation support in primary care could include the provision of provider training, real‐time counseling prompts, and provider performance feedback. These examples represent strategies that span practice‐ and provider‐implementation levels. Another way to boost smoking quit rates in primary care could be to incorporate additional intervention components alongside those already commonly delivered as part of standard care, e.g. provision of tailored print materials, adjunctive counseling provided by allied health professionals and providing people with specific feedback about their smoking‐related health risks. These strategies could be implemented either individually or as part of a multicomponent intervention (combining more than one strategy). While there is a lack of implementation knowledge to inform the design and delivery of tobacco treatment interventions in primary care practice, multicomponent interventions have previously been shown to be the most effective method for increasing both provider performance in the delivery of smoking cessation treatment and improving cessation rates among participants (Anderson 2004; Fiore 2008; Grimshaw 2001; Martin‐Cantera 2015; Papadakis 2010). They are designed to address several barriers to treatment delivery in a synergistic manner, acknowledging the need for more complex or sophisticated intervention models, or both, to bring about changes in healthcare practice and behavior.

Why it is important to do this review

Reflecting the challenges surrounding the effective implementation of smoking cessation treatment in primary care, much research has been carried out investigating how to improve both the implementation and success of these interventions. Some have focused on practice‐level interventions (such as electronic medical record prompts or outreach facilitation (Cummings 1989a; Verbiest 2014); some have focused on provider‐level interventions, such as provider training and incentives (Lennox 1998; Olano Espinosa 2013; Roski 2003), and some have focused on patient‐level interventions (over and above the standard advice delivered by primary care physicians; such as adjunctive counseling, cost‐free medications, biomedical feedback, and tailored printed materials; An 2006; Meyer 2008; Minué‐Lorenzo 2019; Ronaldson 2018). Others have tested a combination of these approaches in multicomponent interventions (e.g. Katz 2004; Twardella 2007; Unrod 2007). Bringing this evidence together allows us to summarize the research methodologies used and to synthesize the evidence in support of specific strategies, or the combination of strategies, that are effective in increasing rates of smoking cessation in the primary care setting. This can be used to inform both clinical practice and the implementation of health policy. Several published meta‐analyses have examined the effect of physician advice and other provider interventions on smoking cessation, but many of these reviews have not been specific to the primary care setting (Boyle 2014; Carson 2012; Clair 2019; Fiore 2008; Rice 2017; Stead 2013; Van den Brand 2017). These previous reviews have also focused on the effect of providing advice on smoking abstinence only; they have not examined improvements in provider performance in the delivery of evidence‐based smoking cessation treatments that may have ultimately led to any increase in effectiveness. Two published meta‐analyses have aimed to do this: Anderson 2004 reviewed the literature published up to 2001, and Papadakis 2010 published an update which examined the literature prior to 2009. Additionally, Martin‐Cantera 2015 narratively reviewed the literature examining multicomponent interventions in primary care, published up to 2014. This review provides an up‐to‐date synthesis of the literature in this field.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of strategies intended to increase the success of smoking cessation interventions in primary care settings.

To assess whether any effect that these interventions have on smoking cessation may be due to increased implementation by healthcare providers.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cluster‐RCTs (cRCTs).

Types of participants

Participants include adult primary healthcare patients. For the purposes of this review, we defined primary care as family medicine or general medical practice. We did not include public health or community interventions in our definition of primary care, nor did we assess interventions delivered in dental offices or pharmacies. We included trials which covered the whole practice population, as well as those which included specific subpopulations recruited from primary care settings (e.g. people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or people with diabetes). We did not include studies that solely addressed the behavior of pregnant women or adolescents, as they are addressed by other Cochrane Reviews (Chamberlain 2017; Claire 2020; Fanshawe 2017).

For our primary outcome, and most of our secondary outcomes, all participants were required to be people who used tobacco at study baseline. However, for our secondary outcome, 'Number of patients asked whether they smoke', participants could include the general population of primary care patients (i.e. both people who used tobacco and people who did not use tobacco at baseline).

Types of interventions

To be included in this review, studies must have investigated an intervention strategy or strategies designed to improve the implementation or success of smoking cessation treatment in primary care. The interventions under investigation in this review were therefore not standard smoking cessation support incorporating brief advice delivered by a primary care physician, or the standard provision of smoking cessation medications in primary care. Interventions of interest could include any strategy or strategies designed to increase or enhance the quality of the support offered, or an adjunctive smoking cessation intervention offered in addition to standard care. Interventions could be implemented at any level (i.e. practice, provider or participant) and the patient‐level components could be delivered by any health professional within a primary care practice setting. Examples of patient‐level interventions investigated in this review included adjunctive counseling delivered by a health professional other than the physician, cost‐free smoking cessation medications and the provision of tailored print materials. Examples of provider‐level interventions included provider training and provider incentives. Examples of practice‐level interventions were outreach facilitation and electronic medical record (EMR) prompts. The categorization of these interventions is subjective, and some interventions may fit equally well at more than one level. For example, we considered in detail whether cost‐free medications should be categorized as a patient‐level, practice‐level, or system‐level intervention (e.g. where medication costs are government‐subsidized), and decided that it could be categorized as all of these. We decided on patient‐level in this instance, as the participant is the beneficiary of the cost savings, which have the potential to increase medication use.

Valid intervention groups were tested as an adjunct to and in comparison with 'standard' smoking cessation support or 'usual care', in order to test the effect of the additional implementation strategy over and above standard care. Standard care is defined differently within and across different communities and studies; however, it typically involves brief behavioral support from the primary care physician, alongside an offer of smoking cessation medication. We also included studies with head‐to‐head comparisons of two or more active interventions, but only if it was possible to isolate the effects of a single strategy or component designed to enhance the delivery of tobacco cessation treatment in primary care.

We did not include studies which covered interventions to enhance tobacco treatment delivery as part of a multifactorial lifestyle intervention.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measure was smoking abstinence at long‐term follow‐up in participants who reported smoking at baseline. To be eligible for inclusion, studies had to measure smoking status at least six months from the start of the intervention. We excluded studies with abstinence measured at less than six months' follow‐up.

In trials with more than one measure of abstinence, we preferred the measure using the longest follow‐up and the strictest criteria, in line with the Russell Standard (West 2005). We used sustained or continuous abstinence over point prevalence abstinence, and biochemically‐validated abstinence, such as exhaled carbon monoxide (CO), over self‐report. We favored biochemically‐validated point prevalence abstinence over self‐reported continuous or prolonged abstinence. We considered participants lost to follow‐up to be still smoking, in line with the practice of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group.

We chose smoking abstinence as the primary outcome, as this is the most clinically relevant outcome; an increase in the number of people quitting is the ultimate goal of any attempt to increase the implementation of smoking cessation treatment.

Secondary outcomes

Our secondary outcomes are deemed to be process outcomes. We therefore did not include studies that only reported on our secondary outcomes and did not investigate our primary outcome.

-

Provider performance in tobacco treatment delivery (these outcomes were informed by the 5As; a sequence of actions proposed by US smoking cessation guidelines that can be applied in primary care settings; Fiore 2008)

Number of participants asked whether they smoke (the denominator for this also includes participants who were not smoking at baseline in studies that enrolled people who smoked and people that did not);

Number of participants identified as smoking who were advised to quit;

Number of participants identified as smoking whose readiness to quit was assessed;

Number of participants identified as smoking who were assisted to quit (further divided into general assistance, medications prescribed, quit date set, counseling provided, self‐help materials provided);

Number of participants identified as smoking who had follow‐up appointments arranged to address smoking.

Participant quit attempts, as defined by individual studies.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases to 10th September 2020:

Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register;

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

MEDLINE (via PubMed);

Embase.

The search strategy used the following keyword terms: ('smoking' or 'smoking cessation' or 'tobacco‐use cessation', or 'tobacco‐use‐disorder) AND ('primary health care' or 'physicians' or 'family practice' or 'general practice' or 'general practitioners' or 'physicians, family'). We used standard search strings, using the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomized controlled trials, as well as 'controlled trials' or 'evaluation studies'. We applied no restrictions by language or publication status. See Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 for the example PubMed and Specialized Register search strategies respectively.

Searching other resources

We searched the following trial registers: www.clinicaltrials.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registration Platform (WHO ICTRP), and reference lists of eligible studies. We also contacted study authors for unpublished results of completed studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

SP, GP and BH independently reviewed titles and abstracts of reports for possible inclusion. We reviewed the full text of any reports which could not be fully assessed using the title and abstract, along with any reports that appeared to be eligible based on the available information. Two review authors (from SP, GP and BH) then independently assessed all of the full‐text articles retrieved, and resolved discrepancies by discussion with a third review author (AP or NL), who acted as an arbiter. We then linked multiple reports of the same eligible study. We recorded all reports of studies excluded at the full‐text screening phase, together with the reason for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

One review author (from SP, GP, BH) extracted data on study characteristics of eligible studies. Two review authors (from SP, GP, BH) independently extracted data on outcomes, and categorized studies according to the type and level of intervention. We extracted the following information from each of the included studies:

lead author and year of publication;

country in which intervention was delivered;

methods of recruiting healthcare practices and participants within practices;

inclusion criteria, including subpopulations;

type of study design (RCT, cluster‐RCT);

target of intervention (participant, provider, practice);

data collection method (interview, telephone, mail survey);

characteristics of study participants (age, sex, comorbidities, readiness to quit);

duration of intervention (in weeks);

details of the intervention;

description of the comparator intervention;

outcomes measured, including definitions used and time point at which they were assessed (in weeks);

use of biochemical validation and participant response rate;

methods used to manage missing data;

for each outcome: number of participants in each arm; loss to follow‐up rate; number of events in each arm; intra‐class correlation coefficient (ICC) (cluster‐RCTs only);

study funding source;

authors' declarations of interest.

Methods for categorizing details of intervention

We categorized intervention strategies into three groups, based on the level at which they were designed to intervene (i.e. participant, provider, practice). We further categorized interventions as either a single or a multicomponent intervention. For the purposes of this review, we defined single‐component interventions as those which included only one intervention strategy. We defined multicomponent interventions as interventions which included two or more intervention strategies, at any level. We used a preliminary list of intervention strategies based on previous systematic reviews (Anderson 2004; Fiore 2008; Papadakis 2010) with further categories added as appropriate to describe other intervention modalities identified in the literature.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (from SP, GP, BH, NL) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies, using Cochrane's RoB1 (Higgins 2011).

We assessed the following domains:

sequence generation (as an indicator of selection bias)

allocation concealment (as an indicator of selection bias)

blinding of outcome assessors (as an indicator of detection bias)

incomplete outcome data (as an indicator of attrition bias)

We did not assess any indicators of performance bias, as all of the studies were assessing a behavioral strategy, and therefore it would have been impossible to blind research staff and participants.

We also assessed the following other sources of bias for c‐RCTs only:

recruitment bias due to recruitment of participants to clusters after allocation;

unbalanced baseline characteristics;

whether statistical adjustment had been made to the analysis to account for the potential correlation of effects within clusters.

Measures of treatment effect

For each study and outcome (smoking abstinence, physician performance outcomes, quit attempts) we calculated the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each relevant comparison investigated (intervention group versus control group). For smoking abstinence and quit attempts the denominators were the number of people randomized to each study arm, assuming that any participants lost to follow‐up were continuing to smoke or had not made a quit attempt. For the physician performance outcomes we carried out a complete case analysis where possible.

Unit of analysis issues

All analyses contain participant‐level data from both RCTs and c‐RCTs. We investigated the effect of adjusting for clustering in c‐RCTs by inflating the standard error of the log RR using the design effect calculated from the estimated ICC that was reported in the study. If no ICC was reported, we assumed a typical ICC value for smoking cessation trials, based on Baskerville 2001. See below (Sensitivity analysis) for more details.

Dealing with missing data

We recorded the proportions of participants lost to follow‐up in each relevant arm of included studies and used this information in our risk of bias assessments. Any participants with missing smoking or quit attempts data at follow‐up were deemed to have returned to active smoking or to have not made a quit attempt respectively, and were included in the denominator for calculating the risk ratio. We did not impute missing data for physician performance outcomes.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity within meta‐analyses and between subgroups using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). We considered an I2 value greater than 50% to indicate moderate to substantial heterogeneity. Where an I2 of greater than 75% was recorded for the pooled result of a meta‐analysis, and this remained unexplained by subgroup analyses, we judged whether it was appropriate to present the pooled estimate.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where analyses included 10 or more studies we generated funnel plots to investigate potential publication bias.

Data synthesis

We grouped studies by intervention type. Where there was more than one study testing an intervention type(s), and where appropriate, we performed meta‐analyses using Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effect models for each outcome. In studies that tested a single intervention component, we did not calculate a pooled estimate across intervention types for each level of intervention (e.g. participant, provider, practice) due to clinical heterogeneity. We were able to carry out meta‐analyses of our primary outcome for comparisons investigating the following singular intervention types:

Participant‐level:

adjunctive counseling

cost‐free medications

biomedical feedback (e.g. spirometry, CO monitoring)

tailored print materials

Provider‐level:

provider training

provider incentives

Some of the studies included in the analyses tested the intervention components above alongside standard care and also used standard care as the comparator, whereas other studies tested the intervention component as part of a multicomponent intervention with a comparator that received the same multicomponent intervention minus the intervention component of interest. These two types of studies were combined in the same meta‐analysis with subgrouping to investigate whether the study design had an impact on study findings.

We were also able to meta‐analyze the following multicomponent interventions versus standard care alone, where more than one study tested the same combination of components:

adjunctive counseling and cost‐free medications

adjunctive counseling and provider training

provider training and flow sheet

provider training and outreach facilitation

Again we carried out meta‐analyses using random‐effects Mantel‐Haenszel methods to calculate RRs and 95% CIs. Where it was not possible to conduct meta‐analyses, i.e. there was only one study investigating the comparison, we summarized studies narratively, calculating and presenting their individual RRs and 95% CIs.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We used subgroup analyses to investigate any differences in the effects observed between studies for the primary smoking abstinence outcome, where possible:

for all comparisons: studies that tested the intervention component(s) of interest alongside and in comparison with standard care only versus studies that tested the intervention component(s) of interest alongside and in comparison with other intervention component(s) of interest;

for all comparisons: participants with chronic disease versus those without chronic disease, e.g. diabetes, COPD;

for adjunctive counseling comparisons: provider type; intensity; mode;

for biomedical feedback: type of biomedical feedback, e.g. spirometry, CO monitoring;

for tailored print materials: theoretical basis of tailoring.

Sensitivity analysis

We used sensitivity analyses to examine the effects of excluding studies with the following characteristics for the primary smoking abstinence outcome:

studies deemed to be at high risk of bias (i.e. judged to be at high risk for at least one risk of bias domain);

individually randomized studies (as opposed to c‐RCTs). c‐RCTs provide the best evidence for the effects of the interventions tested when implemented in primary care, as they would be in the 'real world'.

We also carried out two sensitivity analyses adjusting for appropriate estimates of ICCs in those c‐RCTs that did not report controlling for the clustered nature of the design, or those in which the ICC was not reported. Separate sensitivity analyses used estimated ICCs of 0.01 and 0.05 respectively (Baskerville 2001).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used GRADEpro GDT to import data from Review Manager 5 in order to create summary of findings tables (GRADEpro GDT; Review Manager 2020) for comparisons investigating the following single intervention components:

adjunctive counseling;

cost‐free medications;

biomedical feedback;

tailored print materials;

provider training;

provider incentives.

A summary of the intervention effect for the primary smoking abstinence outcome was produced for each comparison, and we used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the body of evidence (Schünemann 2013), as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2021). We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for our primary outcome ‐ smoking abstinence, downgrading by one level for serious or by two levels for very serious limitations for each consideration.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

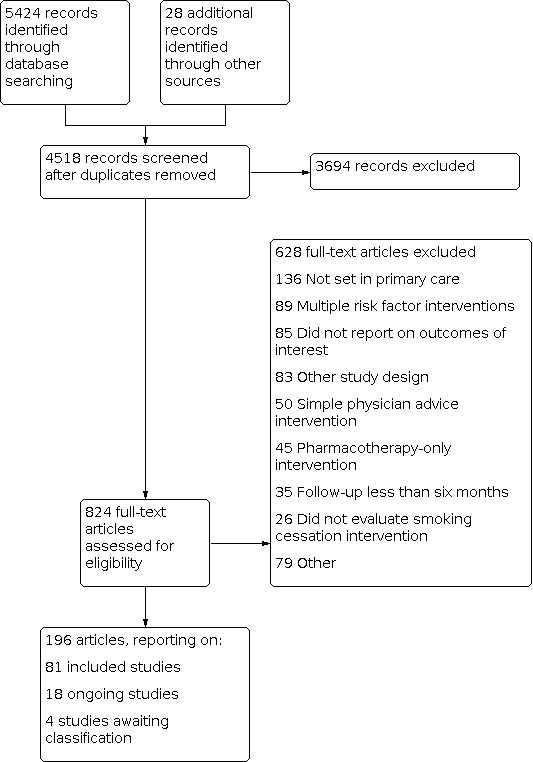

Our searches identified 4518 non‐duplicate records. We screened all records and retrieved the full‐text papers of 824 potentially relevant articles. After screening the full texts we included 81 studies (see Characteristics of included studies), and identified 18 ongoing studies (see Characteristics of ongoing studies) and four studies awaiting classification (Studies awaiting classification). Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow chart for this review.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Of the 81 included studies 43 were individually‐randomized RCTs, 37 were c‐RCTs, and one was a factorial trial. Thirty‐nine studies were conducted in Europe, 26 in the USA, seven in Australia, two each in South America, South Korea and Canada, and one each in China, Pakistan and Thailand. All studies were conducted in primary care settings.

Participants

The 81 included studies represented 112,159 participants. Individual study sample sizes ranged from 48 to 6856. For all but one of the outcomes, all participants were people who attended the practices as patients and smoked tobacco at study baseline. However, where studies measured the number of patients who were asked whether they smoked, participants contributing to the outcome included anyone attending the primary care practice. These non‐smoking participants are included in the total number of participants specified above, but very few studies assessed this outcome.

Five studies recruited from specific population groups; two of these specifically recruited participants with COPD, one recruited participants with diabetes and hypertension, another participants with diabetes only, and the final study recruited participants with a low or moderate household income. The average age of participants ranged from 33 to 64 across studies, and average cigarettes per day ranged from 14 to 26.

Interventions and comparators

We classified study arms according to whether they offered any interventions designed to improve the delivery or success of smoking cessation treatment, over and above standard care. Standard smoking cessation support typically involves brief advice from a physician with a potential offer of medication, and generic printed self‐help materials. Some study arms offered multiple additional components (multicomponent interventions), whereas others offered a single additional component. We classified these components as either patient‐level, provider‐level or practice‐level. Within these classifications we identified the intervention types listed in the table below (for more detailed definitions of the strategies listed see Appendix 3):

| PATIENT‐LEVEL | PROVIDER‐LEVEL | PRACTICE‐LEVEL |

| Adjunctive counseling (offered by a health professional other than the primary care physician, i.e. via a practice nurse, counselor, or smoking quitline) | Provider training | Modified vital sign stamp |

| Tailored printed materials | Provider performance audit and feedback | Treatment flow sheets/consult forms |

| Biomedical feedback (including CO monitoring, gene testing for lung cancer, spirometry and a combination of CO monitoring and spirometry) | Provider incentives | Electronic medical record (EMR) and decision support |

| Medication prompts | ‐ | Outreach facilitation |

| Patient incentives | ‐ | ‐ |

| SMS and Internet cessation programs | ‐ | ‐ |

| Information videos | ‐ | ‐ |

| Access to cost‐free medications (as opposed to medications with a fee, which would be considered standard care) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Proactive outreach | ‐ | ‐ |

Most of the included studies tested smoking cessation intervention components that were provided at the participant level, in addition to standard care (e.g. adjunctive behavioral support, tailored printed materials), rather than testing interventions that aimed to improve the implementation of an existing intervention (e.g. training health providers or EMR prompts), which were provided at the provider or practice level. The latter intervention types are highlighted in bold in the table above.

In order to be included in the review the intervention arm needed to include one or more of the components in the table above in addition to standard smoking cessation care, and in comparison with standard care, in order to isolate the effect of one or more intervention components designed to improve the delivery of smoking cessation treatment in primary care. Studies were also included if they compared an intervention made up of a number of the components above, plus standard care, with the same multicomponent intervention minus one of the components. Again this allowed us to isolate the effect of a single intervention component of interest.

Outcomes

In order to be included in the review, studies had to measure smoking abstinence at six‐month follow‐up or longer, so all 81 studies measured this primary outcome. Most studies had a longest follow‐up of 12 months (42 studies) and 30 studies had a follow‐up of six months. The maximum length of follow‐up was 24 months, measured by five studies. Most studies measured point prevalence abstinence (35 studies), 20 studies measured continuous abstinence and 17 studies measured abstinence that was sustained for a period of time between two time points e.g. between three and six months follow‐up. In nine cases the definition of abstinence used was unclear. Around half of the studies (42 studies) used biochemical validation, such as carbon monoxide monitoring or cotinine levels, to confirm smoking abstinence.

Twenty‐five of the 81 included studies reported on the number of quit attempts made by study participants split by study arm, and 21 of the studies reported on one of the provider performance outcomes in a way that allowed between‐group comparison.

Excluded studies

We list 155 studies excluded at full‐text stage, along with reasons for exclusion, in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Common reasons for exclusion were that studies were not conducted in a primary care setting, that participant care was focused on multiple risk factors as opposed to just smoking cessation, that follow‐up was less than six months and that the study investigated standard smoking cessation support, such as brief physician advice.

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, we judged 14 studies to be at low risk of bias, 23 to be at unclear risk, and the remaining 44 at high risk of bias.

Details of 'Risk of bias' judgments for each domain of each included study can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table. Figure 2 illustrates judgments for each included study.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

When judging sequence generation 10 of the included studies were judged to be at high risk of bias, 32 at unclear risk and 39 at low risk. When judging allocation concealment 12 studies were judged to be at high risk, 37 at unclear risk and 32 at low risk. As is common in many older trials, in many cases sequence generation and allocation concealment were not well described in study reports, hence the high numbers of unclear judgments. This does not necessarily mean that bias was present, but that we were unable to make a judgement based on the information available.

Blinding (detection bias)

When judging the quality of outcome assessment for the primary outcome (smoking abstinence), 23 studies were deemed to be at high risk of bias, seven studies were deemed to be at unclear risk and 51 studies at low risk. Those studies at high risk of bias did not biochemically confirm abstinence and the level of participant contact varied between arms. This means that misreporting of abstinence may have been higher in those study arms with higher contact levels due to social pressures.

Incomplete outcome data

Ten studies were judged to be at high risk of attrition bias, 21 studies were judged to be at unclear risk and 50 studies were judged to be at low risk. Studies at low risk had attrition rates of less than 50% overall and had a less than 20% difference in attrition rates between study arms. Studies in which this domain was judged to be unclear either did not report overall attrition, did not report attrition by study arm, or both.

Recruitment bias due to recruitment of participants to clusters after allocation (cluster‐RCTs only)

Of the 37 cRCTs, 32 were judged to be at low risk of bias for this domain, as participants were already patients at the primary care sites (clusters) before randomization of clusters took place. Five studies were deemed to be at unclear risk of bias.

Unbalanced baseline characteristics (cluster‐RCTs only)

Of the 37 cRCTs, five studies reported unbalanced baseline characteristics between study arms and were therefore deemed to be at high risk of bias. Twenty‐nine studies were judged to be at low risk of bias and three at unclear risk.

Statistical adjustment to account for potential correlation effects within clusters (cluster‐RCTs only)

Twenty‐nine of the 37 cRCTs were judged to be at low risk of bias for this domain, as they reported an attempt to test for, or control for the effects of clustering on the analysis. Two studies were judged to be at unclear risk of bias and six studies were deemed to be at high risk.

Other potential sources of bias

One study (Ronaldson 2018) was deemed to be at high risk of 'other' bias due to it using a wait‐list control design. It appeared that participants in the control group knew that they were on a waiting‐list, meaning they may have postponed their quit attempt until after the trial when they knew that they would receive treatment.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6

Summary of findings 1. Adjunctive counseling in addition to standard smoking cessation care in primary care.

| Adjunctive counseling in addition to standard smoking cessation care in primary care | ||||||

| Patient or population: people who attend primary care and smoke tobacco Setting: primary care (Australia, Europe, South Korea, United States) Intervention: adjunctive counseling plus standard or multicomponent smoking cessation support Comparison: standard or multicomponent smoking cessation support | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with adjunctive counseling | |||||

| Smoking abstinence at 6‐month follow‐up or more. All studies | Study population | RR 1.31 (1.10 to 1.55) | 18,150 (22 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | ‐ | |

| 7 per 100 | 9 per 100 (8 to 11) | |||||

| Smoking abstinence at 6‐month follow‐up or more. Subgroup comparator: standard care | Study population | RR 1.43 (1.15 to 1.78) | 12,852 (17 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEb | ‐ | |

| 4 per 100 | 6 per 100 (5 to 8) | |||||

| Smoking abstinence at 6‐month follow‐up or more. Subgroup comparator: multicomponent intervention | Study population | RR 1.04 (0.87 to 1.23) | 5298 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWc | ‐ | |

| 14 per 100 | 14 per 100 (12 to 17) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: Randomized controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to inconsistency. A subgroup analysis subgrouping by the nature of the comparator resulted in substantial subgroup differences (I2 = 80%). bDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. Removing the studies at high risk of bias shifted the confidence intervals so that they incorporated the potential for no benefit of adjunctive counseling. cDowngraded two levels due to imprecision. CI encompassed both potential benefit and harm.

Summary of findings 2. Cost‐free medications used in addition to standard care in primary care.

| Cost‐free medications used in addition to standard care in primary care | ||||||

| Patient or population: people who attend primary care and smoke tobacco Setting: primary care (Australia, Europe, Pakistan, United States) Intervention: cost‐free medications plus standard or multicomponent smoking cessation support Comparison: standard or multicomponent smoking cessation support | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with cost‐free medications | |||||

| Smoking abstinence at 6‐month follow‐up or more | Study population | RR 1.36 (1.05 to 1.76) | 7560 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa,b | ‐ | |

| 12 per 100 | 17 per 100 (13 to 22) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: Randomized controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to inconsistency. I2 = 63%. bThe funnel plot highlighted one outlier (the smallest study showed a large positive effect of the intervention). However, when this outlier was removed from the analysis the interpretation of the result remained consistent.

Summary of findings 3. Biomedical feedback in addition to standard smoking cessation treatment in primary care.

| Biomedical feedback in addition to standard smoking cessation treatment in primary care | ||||||

| Patient or population: people who attend primary care and smoke tobacco Setting: primary care (Europe, USA) Intervention: biomedical feedback plus standard smoking cessation support Comparison: standard smoking cessation support | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with biomedical feedback | |||||

| Smoking abstinence at 6‐month follow‐up or more | Study population | RR 1.07 (0.81 to 1.41) | 3491 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa | ‐ | |

| 10 per 100 | 11 per 100 (8 to 14) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: Randomized controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels due to imprecision. CI encompassed the potential for both benefit and harm.

Summary of findings 4. Tailored print materials in addition to standard smoking cessation treatment in primary care.

| Tailored print materials in addition to standard smoking cessation treatment in primary care | ||||||

| Patient or population: people who attend primary care and smoke tobacco Setting: primary care (Europe) Intervention: tailored print materials plus standard smoking cessation support Comparison: standard smoking cessation support | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with tailored print materials | |||||

| Smoking abstinence at 6‐month follow‐up or more | Study population | RR 1.29 (1.04 to 1.59) | 15,978 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | ‐ | |

| 3 per 100 | 4 per 100 (4 to 5) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. Removing the two studies judged to be at high risk of bias shifted the CI so that it incorporated the potential for no difference in cessation rates between intervention and comparator groups.

Summary of findings 5. Provider training in addition to standard smoking cessation treatment in primary care.

| Provider training in addition to standard smoking cessation treatment in primary care | ||||||

| Patient or population: people who attend primary care and smoke tobacco Setting: primary care (Argentina, Canada, Europe, USA) Intervention: provider training plus standard or multicomponent smoking cessation support Comparison: standard or multicomponent smoking cessation support | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with provider training | |||||

| Smoking abstinence at 6‐month follow‐up or more | Study population | RR 1.10 (0.85 to 1.41) | 13,685 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ‐ | |

| 5 per 100 | 6 per 100 (5 to 8) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: Randomized controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to inconsistency. I2 = 66%. bDowngraded one level due to imprecision. CI incorporated the potential for both benefit of the intervention and no difference between intervention and control (taking into account the anticipated absolute effects).

Summary of findings 6. Provider incentives in addition to standard smoking cessation treatment in primary care.

| Provider incentives in addition to standard smoking cessation treatment in primary care | ||||||

| Patient or population: people who attend primary care and smoke tobacco Setting: primary care (Germany, USA) Intervention: provider incentives plus standard or multicomponent smoking cessation support Comparison: standard or multicomponent smoking cessation support | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with provider incentives (provider‐level) | |||||

| Smoking abstinence at 6‐month follow‐up or more | Study population | RR 1.14 (0.97 to 1.34) | 2454 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b | ‐ | |

| 18 per 100 | 21 per 100 (17 to 24) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to risk of bias: both included studies were judged to be at high risk of bias. bDowngraded two levels due to imprecision: CIs incorporate the potential of both benefit and harm.

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6 for summaries of effect estimates and GRADE ratings. See: Supplementary file 1; Supplementary file 2 for the results of analyses controlling for the effects of clustering in both individual studies and meta‐analyses.

Studies were meta‐analyzed where there was more than one study providing data for an outcome for a comparison. The first three comparisons (adjunctive counseling, cost‐free medications, biomedical feedback) investigate patient‐level interventions intended to directly improve smoking quit rates, whereas the fourth and fifth comparisons investigate provider‐level interventions which are designed to boost provider implementation of smoking cessation support, in order to ultimately improve quit rates.

Adjunctive counseling (patient‐level strategy)

We found 22 studies that looked at the effect of adding counseling (delivered by an allied health professional rather than the primary care physician) to standard care or a multicomponent smoking cessation intervention. Pooling these studies provided evidence that additional counseling resulted in more favorable smoking quit rates (RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.55; I2 = 44%; 18,150 participants; Analysis 1.1). The interpretation of the result remained the same when 12 studies judged to be at high risk of bias were removed from the analysis, when 15 individually‐randomized studies were removed from the analysis, and when sensitivity analyses adjusting for clustering were carried out.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Adjunctive counseling (patient‐level), Outcome 1: Long‐term abstinence (subgrouped by single vs. multicomponent intervention type)

However, a subgroup analysis grouping the studies by whether counseling was provided as an adjunct to standard care alone or as an adjunct to an intervention that also included other strategies designed to improve smoking cessation treatment, found evidence of a subgroup difference (I2 = 80%). Where the counseling was used as an add‐on to standard care the RR was 1.43 (95% CI 1.15 to 1.78; I2 = 39%; 18 studies, 12,852 participants), suggesting a beneficial effect of counseling. However, where the counseling was added to standard care with other potential improvement strategies the RR for counseling was 1.04, with CIs suggesting that the addition of counseling could provide no benefit or could potentially enhance or decrease the quit rate (95% CI 0.87 to 1.23; I2 = 9%; 7 studies, 5298 participants). Further subgrouping by provider, mode of delivery and intensity of counseling did not provide evidence that the effect of adjunctive counseling was influenced by these factors (Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3; Analysis 1.4).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Adjunctive counseling (patient‐level), Outcome 2: Long‐term abstinence (subgrouped by provider)

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Adjunctive counseling (patient‐level), Outcome 3: Long‐term abstinence (subgrouped by mode)

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Adjunctive counseling (patient‐level), Outcome 4: Long‐term abstinence (subgrouped by intensity)

More than one of the included studies investigating the effects of adjunctive counseling measured each of the following process measures: advice rates; assistance rates; arrangement of follow‐up; quit attempts. The evidence was inconclusive on whether adjunctive counseling improved rates of smoking cessation advice, the provision of self‐help materials or counselling, or assistance to set a quit date (Analysis 1.5; Analysis 1.6); however, there was some evidence that adjunctive counseling may have a beneficial impact on the provision of smoking cessation medications (Analysis 1.6), and the number of people who made a quit attempt (Analysis 1.8). There was also some evidence, limited by imprecision, that adjunctive counseling may increase the arrangement of patient follow‐up by physicians (Analysis 1.7). When pooling the relevant data statistical heterogeneity was high (I2 = 83%), but we decided not to suppress the pooled effect estimate as all of the point estimates demonstrated a beneficial effect of adjunctive counseling.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Adjunctive counseling (patient‐level), Outcome 5: Advise rates

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Adjunctive counseling (patient‐level), Outcome 6: Assistance rates

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Adjunctive counseling (patient‐level), Outcome 8: Quit attempts

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Adjunctive counseling (patient‐level), Outcome 7: Arrange follow‐up support rates

Cost‐free medications (patient‐level strategy)

We pooled 10 RCTs looking at the effect of adding cost‐free medications to standard smoking cessation care or including cost‐free medications as part of a multicomponent smoking cessation intervention. There was evidence that providing cost‐free medication increased the number of people who successfully quit smoking (RR 1.36, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.76; I2 = 63%; 7560 participants; Analysis 2.1). Although moderate statistical heterogeneity was detected, subgrouping by whether cost‐free medications were added to standard care alone or were delivered as part of a multicomponent intervention did not result in a meaningful subgroup effect (I2 = 0%). We judged seven of the studies included in this analysis to be at high risk of bias, but a sensitivity analysis removing these did not result in a meaningful change to the result. Likewise, sensitivity analyses removing the five studies individually randomized and investigating the potential impact of clustering on the effect estimate did not result in meaningful changes to the result.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Cost‐free medications (patient‐level), Outcome 1: Long‐term abstinence (subgrouped by single vs. multicomponent intervention type)

Three of the studies that investigated cost‐free medications also investigated their effect on participant quit attempts. There was evidence that their provision resulted in a higher number of quit attempts made (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.43; 3 studies, 2669 participants; Analysis 2.2). Heterogeneity was substantial (I2 = 72%), but in all cases the study effect estimates favored the intervention arm.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Cost‐free medications (patient‐level), Outcome 2: Quit attempts

Biomedical feedback (patient‐level strategy)

We identified seven trials looking at the effects of adding biomedical feedback to smoking cessation treatment in primary care. Four of these studies investigated spirometry (Irizar Aramburu 2013; Parkes 2008; Ronaldson 2018; Segnan 1991), one study investigated CO monitoring (Jamrozik 1984), one study CO monitoring and spirometry (Sippel 1999), and one study looked at the effect of gene testing for lung cancer risk (Nichols 2017). We pooled the seven studies and subgrouped according to feedback type. There was no clear evidence of a beneficial effect of biomedical feedback on smoking cessation rates (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.41; I2 = 40%; 3491 participants; Analysis 3.1). The result was imprecise, with a CI encompassing the potential for both an increase and a decrease in quit rates. There was no evidence of a difference in effect depending on the type of biomedical feedback used (I2 = 0%), and a sensitivity analysis removing the three studies at high risk of bias did not change the interpretation of the results. None of the studies included in this meta‐analysis were cluster‐RCTs, so we did not conduct a sensitivity analysis removing individually‐randomized studies or adjusting for clustering.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Biomedical feedback (patient‐level), Outcome 1: Long‐term abstinence (subgrouped by type)

Tailored print materials (patient‐level strategy)

We pooled six studies assessing the addition of tailored printed materials to standard smoking cessation support, subgrouped based on the theoretical basis of the tailoring (Analysis 4.1). Two of the studies were based on the transtheoretical model, but four studies did not have a clear theoretical basis. Overall, there was evidence that providing participants with tailored printed materials increased their smoking cessation rates (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.59; I2 = 37%; 15,978 participants), and there was no evidence that the effect was moderated by the theoretical basis of the material. However, a sensitivity analysis removing two studies at high risk of bias resulted in increased imprecision, so that the resulting CIs encompassed the possibility of no effect of tailored printed materials on smoking cessation rates, as well as a potential positive impact (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.70). This analysis contained no c‐RCTs and therefore sensitivity analyses were not required to assess the potential effects of removing individually‐randomized studies or adjusting for clustering.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Tailored print materials (patient‐level), Outcome 1: Long‐term abstinence (subgrouped by theoretical basis)

Three of the studies that assessed the effects of tailored printed materials also looked at quit attempts as an outcome (Gilbert 2013; Gilbert 2017; Hoving 2010). The pooled effect estimates and 95% CIs incorporated the possibility that providing tailored printed materials led to no increase in attempts to quit smoking, as well as the possibility of an increase in quit attempts (RR 1.08, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.17; I2 = 17%; 11,122 participants; Analysis 4.2).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Tailored print materials (patient‐level), Outcome 2: Quit attempts

Provider training (provider‐level strategy)

Seven RCTs looked at the effects of adding provider smoking cessation training to other smoking cessation strategies or standard treatment. Pooling these studies resulted in an RR of 1.10 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.41; 13,685 participants; Analysis 5.1). There was no evidence of a clear benefit of provider training, but there was evidence of both substantial imprecision and moderate statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 66%). There was no evidence that the effect differed depending on whether provider training was offered in addition to and compared with standard care, or whether provider training was offered alongside other strategies to improve the delivery of smoking cessation and compared with those multicomponent interventions minus provider training (I2 = 0%). Sensitivity analyses removing two studies judged to be at high risk of bias and adjusting for the effect of clustering had no appreciable impact on the result or its interpretation. As none of the studies was individually randomized a sensitivity analysis removing this study type was not required.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Provider training (provider‐level), Outcome 1: Long‐term abstinence

A number of studies examined the effect of training on provider performance and participant quit attempts outcomes. Evidence from meta‐analyses suggested that provider training increased the amount that physicians asked participants whether they smoked tobacco, increased the number of people physicians advised about their smoking, and increased the amount of assistance given in the form of providing printed self‐help materials and providing counseling (Analysis 5.2; Analysis 5.3; Analysis 5.4). In some of these cases statistical heterogeneity was high, but point estimates always favored the intervention, and so we deemed it appropriate to present a pooled estimate. In four cases (aiding the participant in setting a quit date; provision of smoking cessation medication, participant quit attempts and the arrangement of follow‐up support), the point estimates favored provider training, but there was imprecision, so that the CIs incorporated the possibility of no effect of provider training, as well as a potential positive effect (Analysis 5.4; Analysis 5.5; Analysis 5.6).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Provider training (provider‐level), Outcome 2: Asking rates

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Provider training (provider‐level), Outcome 3: Advise rates

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Provider training (provider‐level), Outcome 4: Assistance rates

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Provider training (provider‐level), Outcome 5: Arrange follow‐up support rates

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Provider training (provider‐level), Outcome 6: Quit attempts

Provider incentives (provider‐level strategy)

Two studies looked at the effects of the addition of provider incentives to standard smoking cessation care or as part of a multicomponent smoking cessation intervention. When pooled these studies resulted in an RR of 1.14 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.34; I2 = 0%; 2454 participants; Analysis 6.1). There was imprecision, with CIs incorporating the potential for a reduction in quit rates as well as the potential for an increase, when provider incentives were implemented. Subgrouping by whether the intervention was provided alongside standard care alone or other delivery improvement strategies provided no evidence of effect moderation, and a sensitivity analysis adjusting for clustering did not affect our interpretation of the result. Neither of the studies was individually randomized and so a sensitivity analysis to remove this type of study was not required. However, we rated both studies at high risk of bias and so results should be interpreted with caution.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Provider incentives (provider‐level), Outcome 1: Long‐term abstinence

Other single strategies

In addition, to the studies described as part of the comparisons above, Supplementary file 3 narratively summarizes six additional included studies that investigated a single novel strategy. These strategies were reinforcement text messages (Cobos‐Campos 2016), proactive patient outreach by mailings and telephone (Fu 2014), a smoking cessation video (Lee 2016), an internet smoking cessation program (Pisinger 2010), tailored letters to participants and a provider desktop resource with treatment advice (Meyer 2012). There was also a randomized factorial trial which investigated a number of different strategies (Piper 2016).

Multi‐component interventions

Thirty‐four included studies compared the combination of two or more strategies to improve the delivery of smoking cessation treatment in primary care (multicomponent interventions) in addition to standard smoking cessation, in comparison with a control arm of standard care. These studies are summarized narratively in Supplementary file 4 with RRs and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Twenty‐seven (77%) of the multicomponent studies investigated patient‐level strategies, 25 (71%) provider‐level strategies, and 12 (34%) practice‐level strategies. Some studies incorporated strategies from all three levels, with a maximum of five different strategies used in some studies. Where more than one of these studies investigated the same combination of strategies we conducted meta‐analyses.

Three studies looked at the effect of adjunctive counseling and cost‐free medications (both patient‐level strategies designed to directly increase quit rates) on smoking abstinence rates. The pooled estimate suggested a benefit of providing these two intervention components in addition to standard support (RR 3.09, 95% CI 1.13 to 8.44; 1066 participants; Analysis 7.1). However, this result should be treated with caution, as we judged all of the studies to be at high risk of bias. There was also substantial statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 75%), but as the point estimates all indicated benefit we deemed it appropriate to present a pooled estimate. None of the three studies in this analysis was a cRCT and so sensitivity analyses removing individually‐randomized studies and adjusting for clustering were not necessary.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Adjunctive counseling + cost‐free meds versus standard care, Outcome 1: Long‐term abstinence