Abstract

Ten atypical European Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (Borrelia spp.) strains were genetically characterized, and the diversity was compared to that encountered among related Borrelia spp. from North America. Phylogenetic analyses of a limited region of the genome and of the whole genome extend existing knowledge about borrelial diversity reported earlier in Europe and the United States. Our results accord with the evidence that North American and European strains may have a common ancestry.

In Europe, five species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato have been delineated so far. Three of them are pathogenic for humans, i.e., B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, and B. afzelii, whereas the pathogenicity for humans of the two species B. valaisiana and B. lusitaniae remains uncertain (7). However, some strains isolated recently from Ixodes ricinus ticks in Germany (five strains) (10), Switzerland (four strains), and Russia (one strain) are atypical on the basis of their rrf-rrl spacer restriction patterns. Our aim was to further characterize these strains by methods involving either a limited region of the genome, specifically the rrf-rrl spacer and the rrs gene (4, 5), or the whole genome as determined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and arbitrarily primed PCR (AP-PCR) (1, 2). The observed genetic diversity was compared to that described for Borrelia spp. from North America (5).

When analyzing the polymorphism of the rrf-rrl spacer, we found that all atypical strains exhibited MseI patterns close to and DraI patterns quite distinct from those of B31T (Table 1). To further evaluate the polymorphism, the spacer regions of the atypical strains and of 10 additional European strains identified earlier as B. burgdorferi sensu stricto were sequenced (Table 1). Next, sequences available in databases were compared with the sequences determined in this study. The phylogenetic analyses of rrf-rrl spacer sequences conducted by neighbor joining and unpaired group mathematical averaging distance methods yielded similar results (data not shown). They revealed that the strains NE99 and NE271 belonged to B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, confirming previous results (3). The remaining European strains constituted separate clusters close to the North American strains CA13 and CA28 (5). Sequences obtained from strains NE581, NE49, and Ir-3519 had 100% identity and only one nucleotide difference with the sequence of the strain Z41493. However, sequences obtained from other German strains exhibited 16 nucleotide differences from the sequence of strain Z41493. The diversity deduced from rrf-rrl spacer sequences of Borrelia spp. contrasts with the considerable homogeneity of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto sequences noted before (5). Since the rrf-rrl spacer sequence was hitherto strictly correlated with the Borrelia species assignment (4, 5), our results suggest that some atypical European and North American strains might represent a new genomic group.

TABLE 1.

B. burgdorferi sensu lato European isolates evaluated in this study

| Strain | rrf-rrl spacer GenBank accession no. | rrs gene GenBank accession no.c | Source | Country of origin | MseI patterns (bp)b | DraI patterns (bp)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. burgdorferi sensu stricto | ||||||

| NE99 | AF090974a | NA | I. ricinus | Switzerland | 107, 52, 40, 29, 28 | 146, 53, 29, 28 |

| NE271 | AF090973a | NA | Sciurus vulgaris | Switzerland | 107, 52, 40, 29, 28 | 146, 53, 29, 28 |

| IP1 | AF090977a | NA | Human | France | 107, 52, 38, 29, 28 | 144, 53, 29, 28 |

| HII | AF090978a | NA | Human | Italy | 107, 52, 38, 29, 28 | 144, 53, 29, 28 |

| L5 | AF090979a | NA | Human | Austria | 107, 52, 38, 29, 28 | 144, 53, 29, 28 |

| DK7 | AF090975a | X85195 | Human | Denmark | 107, 52, 38, 29, 28 | 144, 53, 29, 28 |

| NE 56 | AF090981a | NA | I. ricinus | Switzerland | 107, 52, 38, 29, 28 | 144, 53, 29, 28 |

| 20006 | AF090982a | NA | I. ricinus | France | 107, 52, 38, 29, 28 | 144, 53, 29, 28 |

| Esp1 | AF090976a | NA | I. ricinus | Spain | 107, 52, 38, 29, 28 | 144, 53, 29, 28 |

| 35B808 | AF090980a | NA | I. ricinus | Germany | 107, 52, 38, 29, 28 | 144, 53, 29, 28 |

| 212 | L30121 | NA | I. ricinus | France | 107, 52, 38, 29, 28 | 144, 53, 29, 28 |

| Z51794 | Z77167 | NA | I. ricinus | Germany | 107, 52, 38, 29, 28 | 144, 53, 29, 28 |

| Z75892 | Z77166 | NA | I. ricinus | Germany | 107, 52, 38, 29, 28 | 144, 53, 29, 28 |

| MIL | AF090971a | NA | I. ricinus | Slovakia | 107, 52, 40, 29, 28 | 146, 53, 29, 28 |

| Z136 | AF090972a | NA | I. ricinus | Germany | 107, 52, 40, 29, 28 | 146, 53, 29, 28 |

| Borrelia spp. | ||||||

| NE49 | AF090984a | AJ224142a | I. ricinus | Switzerland | 107, 53, 38, 29, 26 | 144, 80, 29 |

| NE581 | AF090983a | NA | I. ricinus | Switzerland | 107, 53, 38, 29, 26 | 144, 80, 29 |

| Ir-3519 | AF090985a | NA | I. ricinus | Russia | 107, 53, 38, 29, 26 | 144, 80, 29 |

| Z41493 | Z77172 | AF091368a | I. ricinus | Germany | 107, 79, 38, 29 | 144, 80, 29 |

| Z41293 | Z77170 | AF091367a | I. ricinus | Germany | 107, 52, 38, 29, 29 | 144, 82, 29 |

| Z51094 | Z77171 | NA | I. ricinus | Germany | 107, 52, 38, 29, 29 | 144, 82, 29 |

| Z52794 | Z77169 | NA | I. ricinus | Germany | 107, 52, 38, 29, 29 | 144, 82, 29 |

| Z57394 | Z77168 | NA | I. ricinus | Germany | 107, 52, 38, 29, 29 | 144, 82, 29 |

Sequences determined in this study.

Exact sizes were deduced from rrf-rrl spacer sequences.

NA, not available.

The rrs sequence comparison yielded similarity values ranging from 99.5 to 99.7% for the three atypical European strains NE49, Z41293, and Z41493 and from 98.7 to 99.7% for these three strains and representatives of the three pathogenic species B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, and B. afzelii (data not shown). The phylogenetic analysis of the rrs gene sequence revealed that each atypical European strain clustered separately within a large cluster comprising B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and B. bissettii. The resolution power of rrs sequences was low when closely related organisms were analyzed (8). At the high level of rrs similarity values observed between Borrelia spp., DNA relatedness values can either be low or approach 100%. Although our phylogenetic results suggest that European strains constitute at least one new genomic group, these data are too inconclusive to definitively assign them to a separate group at this time.

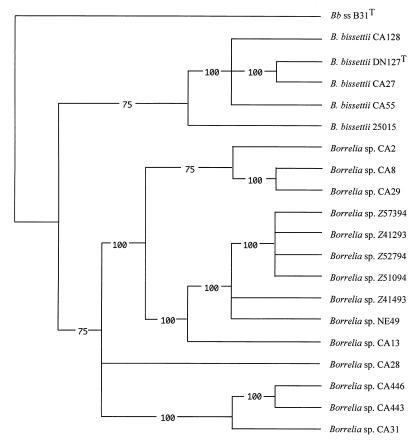

AP-PCR fingerprints were obtained from six Borrelia spp. strains from Europe and 14 Borrelia spp. strains from North America (5) using five primers (2). For each strain, 74 polymorphic characteristics yielded a data matrix that was used to draw phylogenetic trees. The results of the analysis by a parsimony method (Fig. 1) coincided with those inferred from distance analysis and confirmed the clustering deduced previously from rrf-rrl and rrs sequence analyses. Fingerprinting by AP-PCR provides taxonomic information which accords with species assignment based on DNA relatedness (6, 9). In the present study, the paucity of AP-PCR characteristics shared by strains reflects the high level of genetic divergence of Borrelia spp. As observed for Leptospira strains (6), fingerprints differed markedly between strains from different genomic groups. Except for European strains that shared many arbitrarily primed PCR markers, marked heterogeneity also was observed between strains within each genomic group. However, relationships observed with AP-PCR data are consistent with the sequencing data. Atypical European strains were closely related and constituted a single lineage, which suggests that they belong to the same genomic group, together with the North American strain CA13. Borrelia spp. strains isolated in North America exhibited greater diversity and were scattered on three main branches, whereas B. bissettii strains constituted a separate cluster.

FIG. 1.

The 50% majority-rule consensus of 32 trees obtained by maximum parsimony analysis. The tree was generated from the AP-PCR matrix and was solved by the heuristics method contained within the PAUP package.

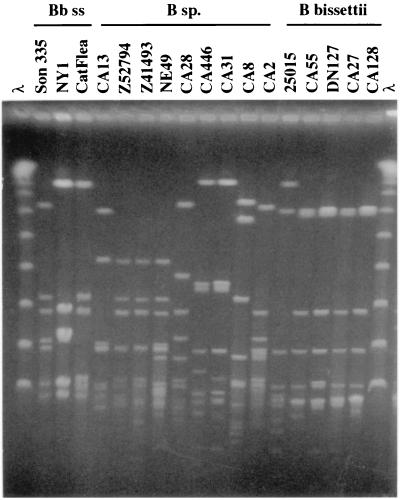

PFGE permitted the resolution of MluI and BssHII macrorestriction fragments of the strains into a large number of distinct types. MluI restriction profiles of B. burgdorferi sensu lato strains obtained with a pulse time ramped from 3 to 28 s for 30 h are shown in Fig. 2. Lambda concatemers (λ 48.5-kb ladder) were used as size markers. Ten MluI patterns were recorded among 15 atypical strains. Despite a high degree of polymorphism, all B. bissettii strains but the divergent strain 25015 shared a common MluI pattern. Strains CA446 and CA31 likewise shared a similar MluI pattern, as did the three European strains Z52794, Z41493, and NE49. Similar results were obtained after restriction by BssHII (data not shown), although the polymorphism was even larger, because 12 BssHII patterns were recorded among 15 strains.

FIG. 2.

MluI restriction profiles of B. burgdorferi sensu lato strains obtained with the BioRad apparatus with a pulse time ramped from 3 to 28 s for 30 h.

AP-PCR and PFGE showed about the same discriminatory power and produced comparable results. The existence of four robust clusters was constant irrespective of the method. One cluster comprised B. bissettii strains, the second comprised strains CA29 and CA8, the third comprised strains CA443, CA446, and CA31, and the last one comprised the European strains. As demonstrated recently for B. bissettii, each of the other three groups could constitute a new genomic species. Regardless of the method used, a greater diversity was observed among Borrelia spp. strains from North America, which suggests a longer evolution time, as compared to European strains. Some European strains genetically resembled Californian strains, however. Taken together, these observations suggest that Borrelia spp. analyzed in the present study may share a common ancestry.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. G. Schwan, R. N. Brown, and E. Korenberg for supplying some of the strains, O. Péter for his comments on strain NE49, L. Gern for critical reading of the manuscript, and E. Bellenger and N. Sertour for technical assistance.

We thank the Pasteur Institute for supporting this work. Part of this study was supported by grant AI22501 from the N.I.H. and C.D.C. Cooperative Agreement U50/CCU906594 to R.S.L. and grant 32-29964-90 from the Swiss National Science Foundation to P.F.H. N.M.R. was supported by the Commission of the European Communities (contract ERBFMBI CT96 0684).

REFERENCES

- 1.Belfaiza J, Postic D, Bellenger E, Baranton G, Saint Girons I. Genomic fingerprinting of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2873–2877. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2873-2877.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foretz M, Postic D, Baranton G. Phylogenetic analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto by arbitrarily primed PCR and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:11–18. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humair P-F, Péter O, Wallich R, Gern L. Strain variation of Lyme disease spirochetes isolated from I. ricinus ticks and rodents collected in two endemic areas in Switzerland. J Med Entomol. 1995;32:433–438. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/32.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Postic D, Assous M V, Grimont P A D, Baranton G. Diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato evidenced by restriction fragment length polymorphism of rrf (5S) rrl (23S) intergenic spacer amplicons. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:743–752. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-4-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Postic D, Ras N M, Lane R S, Hendson M, Baranton G. Expanded diversity among Californian Borrelia isolates and description of Borrelia bissettii sp. nov. (formerly Borrelia group DN127) J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3497–3504. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3497-3504.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ralph D, McClelland M, Welsh J, Baranton G, Perolat P. Leptospira species categorized by arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and by mapped restriction polymorphisms in PCR-amplified rRNA genes. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:973–981. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.973-981.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rijpkema S G T, Tazelaar D J, Molkenboer M J C H, Noordhoek G T, Plantinga G, Schouls L M, Schellekens J F P. Detection of Borrelia afzelii, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, Borrelia garinii and group VS116 by PCR in skin biopsies of patients with erythema migrans and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1997;3:109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stackebrandt E, Goebel B M. Taxonomic note: a place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:846–849. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welsh J, Pretzman C, Postic D, Saint Girons I, Baranton G, McClelland M. Genomic fingerprinting by arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction resolves Borrelia burgdorferi into three distinct phyletic groups. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:370–377. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-3-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wittenbrink M M, Reuter C, Manz M L, Krauss H. Primary culture of Borrelia burgdorferi from Ixodes ricinus ticks. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1996;285:20–28. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(96)80018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]