Abstract

BACKGROUND AND AIMS:

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) provide an important tool for the generation of patient-derived cells, including hepatocyte-like cells, by developmental cues through an endoderm intermediate. However, most iPSC lines fail to differentiate into endoderm, with induction resulting in apoptosis.

APPROACH AND RESULTS:

To address this issue, we built upon published methods to develop an improved protocol. We discovered that doxycycline dramatically enhances the efficiency of iPSCs to endoderm differentiation by inhibiting apoptosis and promoting proliferation through the protein kinase B pathway. We tested this protocol in >70 iPSC lines, 90% of which consistently formed complete sheets of endoderm. Endoderm generated by our method achieves similar transcriptomic profiles, expression of endoderm protein markers, and the ability to be further differentiated to downstream lineages.

CONCLUSIONS:

Furthermore, this method achieves a 4-fold increase in endoderm cell number and will accelerate studies of human diseases in vitro and facilitate the expansion of iPSC-derived cells for transplantation studies.

Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived hepatocytes (iPSC-Heps) have potential to be the most useful individual human-specific cell line to recapitulate not only our variable differences in single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) gene expression, but also as a potential way to model our individual increased or decreased susceptibility to disease. iPSC-Heps effectively model SNP-based interhuman genetic differences, including cytochrome P450 2D6 type I and type II metabolic phenotypes.(1) More important, unlike hepatoma tumor lines, iPSC-Heps function as postmitotically differentiated cells without significant proliferation, but with the added benefit of true high-level hepatic functioning. Unlike primary human hepatocytes, we can readily expand iPSCs to differentiate into any number of hepatocytes and can genetically modify them in forward genetic screening. Given the promise of iPSC-Heps, their Achilles heel has been the tremendous clonal variability encountered during efforts to differentiate them into hepatocytes that could be related to epigenetic or genetic alterations.(2) Although embryonic stem cell lines show greater reliability in differentiation, different iPSC lines, even if derived from a single patient with optimized protocols, often succumb to massive cellular death during induction to endoderm.(3,4) IPSCs that survive beyond endoderm go on to successfully produce hepatocytes or other cell types.

In the published literature and in practice, research groups often use only several highly selected subclones of pluripotent cells for all of their studies, because many lines lack efficient induction of endoderm. In order to usefully characterize and compare patient-derived iPSC lines from multiple patients using high-content screens, it is critical to consistently make true endoderm in complete monolayer sheets. We therefore explored the ability to achieve a more-efficient induction of endoderm.

Differentiation of stem cells into mature human cells often progresses through a step-wise natural progression similar to embryogenesis into ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm. Of these, for unknown reasons, production of endoderm appears to be particularly challenging in vitro and perhaps this is why spontaneous mature teratomas in vivo often contain more ectodermal and mesendodermal tissues than endoderm.(5) Yet if the promise of iPSCs is to produce mature cell lines from any patient or healthy person, this issue must be overcome. Induction of human iPSCs to endoderm through activin A often results in significant cellular death. High-dose activin A induces the NODAL pathway, driving multiple downstream pathways important in endoderm induction, including mothers against decapentaplegic homolog (SMAD) 2 and 3.(6,7) Unfortunately, there are also multiple downstream pathways activated by activin A driving cellular apoptosis, including SH2 (Src homology 2)-containing inositol 5’-phosphatase-1, death-associated protein kinase (DAPK), and TGF-β-inducible early gene (downstream of SMAD signaling), and inhibition of protein kinase B (AKT) pathways (through inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase).(8–10) Because these apoptotic pathways provoke a significant loss of cells, successful induction is dependent on the health of the cell lines, plating density, media balance, and surface environment—making differentiation to endoderm extremely challenging.(11) Even under optimal conditions, most iPSC lines undergo total cellular death at the endoderm induction stage within the first 2–3 days.(3) Our hypothesis was that there must be an efficient way to circumvent apoptosis and induce any cell line to efficiently form endoderm.

We therefore set out to test endoderm induction by genetic methods. In the process, we discovered that the use of doxycycline (Dox) as a medium additive significantly enhanced survival and expansion at the endoderm stage and thus improves the differentiation of iPSCs from multiple donors and different reprograming conditions into sheets of endoderm cells. Our results also illustrate no significant differences in gene expression or phenotype between iPSC-Heps generated with or without doxycycline. Dox appears to stimulate AKT phosphorylation, supporting survival. This protocol also induces a proliferative wave at the end of the endoderm induction stage.

Materials and Methods

CELL CULTURE OF iPSCs

The media conditions to maintain human iPSCs have all been described.(12) Details can be found in the Supporting Information.

LENTIVIRAL CONSTRUCTS AND PROTOCOL

Lentiviral constructs CS-TRE-c-MYC-PRE-Ubc-tTA-I2G-RESS-GFP (MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor; cMYC) and CS-TRE-BCL-XL-PRE-Ubc-tTA-I2G-RESS-GFP (B-cell lymphoma-extra large; BCL-XL) were generous gifts from the Eto laboratory and were transduced as reported.(13)

INDUCTION OF HEPATIC DEFINITIVE ENDODERM (DAYS 0–7)

Cells were induced by recombinant human activin A (100 ng/mL; catalog #120-14E; PeproTech, Cranbury, NJ) for 7 days at 20% oxygen, with 5% C02. On the day before differentiation (day 0), cells were replated on Matrigel-coated plates in the presence of 2 μM of Dox and 10 μM of Y-27632. On day 1 of induction, 2% knockout serum replacement (KSR; catalog #10828028; Gibco, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA), CHIR-99021 (3 mM; catalog #S2924; Selleckchem, Houston, TX), PI-103 (50 nM; catalog #S1038; Selleckchem), recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4; 10 ng/mL; catalog #120-05ET PeproTech), and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2; 20 ng/mL; catalog #100-18B; PeproTech) were added to the media. On day 2, 1% KSR, PI-103 (50 nM), BMP4 (10 ng/mL), and FGF2 (20 ng/mL), and on day 3, 0.2% KSR and PI-103 (50 nM), were added to the media. Dox hyclate (catalog #446061000; Acros Organics, Thermo Fisher) was added throughout definitive endoderm induction at various doses, as described in text, with a standard dose being 2 μM.

DIFFERENTIATION TO PANCREATIC PROGENITORS

Pluripotent HUES8 human embryonic stem cells were seeded at a density of 1e6 cells/mL in mTeSR-1 (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC) into a 30-mL biott (ReproCell, Beltsville, MD) on a magnetic stir plate (Chemglass Dura-Mag, Boston, MA) at a rotation rate of 60 rpm in 37°C, 5% CO2, and 100% humidity. Differentiation was initiated 72 hours later and taken through pancreatic progenitor stage 4 with the growth factors described in Pagliuca et al.(14) The experimental biott also included Dox (2μM) in both stage 1 feeds. Media formulations and details are provided in the Supporting Information (supplemental methods).

RNA ISOLATION, REAL-TIME PCR ANALYSIS, AND RNA-SEQUENCING

Total RNA was isolated by the Qiagen RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) or Zymo Direct-zol RNA kits (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized by qScript cDNA SuperMix (Quantabio, Beverly, MA). Quantitative real-time PCR (qrtPCR) was performed using FastStart Universal SYBR Green (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed by BGI (Boston, MA). Poly-A RNA was selected using oligo-dT magnetic beads, followed by N6 random priming. On average, 27,642,407 raw reads were obtained and mapped per sample. Raw reads were subjected to quality control. Clean reads were analyzed by Gene Ontology analysis, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway enrichment, and cluster analysis. RNA-seq data were deposited and are available at ArrayExpress (accession number: E-MTAB-8821).

Moon Bio ANTIBODY ARRAY

To analyze protein levels and specific phosphorylation, the Phospho Explorer Antibody Array was performed. iPSC line 7192 was induced with and without Dox 2 μM for 6 days. Extracts were made using Complete Lysis-M EDTA-Free Lysis buffer (Roche, South San Francisco, CA) with phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (#5870; Cell Signaling). Antibody Array was performed, scanned, and analyzed by Full Moon Biosystems (i.e., Moon Bio, Sunnyvale, CA).

IMAGING AND QUANTIFICATION OF CONFLUENCY AND CELL NUMBERS

Cell confluency was measured by using software on the BioTek Cytation5 imaging reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). Specifically, quantification of cell confluency was performed with the Gen5 Image Prime 3.08 automated “cell confluence” feature using fine-tuned Autofocus and a known target identification feature (BioTek).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Experiments were run in at least triplicate for each condition. Statistical significance was represented as SD and was determined using the Student t test or ANOVA analysis, as appropriate (GraphPad Prism; GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

STUDY APPROVAL

All studies using human stem cell materials were carried out under approval by University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board (IRB) study approval 10-04393. Per the IRB, informed consent in writing was obtained from each patient and the study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the institutional review committee.

Results

INDUCTION OF MULTIPLE iPSC LINES FROM DIFFERENT PATIENTS USING DEFINED MEDIA

With our interest in characterizing multiple different iPSC-Heps, we tested multiple published protocols and found significant differentiation variability and cellular death during endoderm induction.(15–18) We next tested combining different protocols to see whether we could achieve better differentiation across multiple independent cell lines. Addition of CHIR99021 in the first 24 hours improved the number of cells in multiple different cell lines.(19) Addition of FGF2 and BMP4 for the first 48 hours sometimes helped endoderm induction.(19) We chose to retain these factors because it led to improvement in some lines.(20) Based on our earlier experience with induction in serum-free media,(16,21) we omitted serum in many early experiments. However, with very fragile lines, we ultimately added KSR and found that addition of small amounts of KSR in the first 72 hours improved survival. In order to counteract the insulin present in KSR, we added the small molecule, PI-103. This combined protocol (Supporting Fig. S1A) worked for approximately one fourth of our cell lines, but still showed stochastic cell death and inconsistency and did not allow us to differentiate numerous important patient-derived iPSCs.

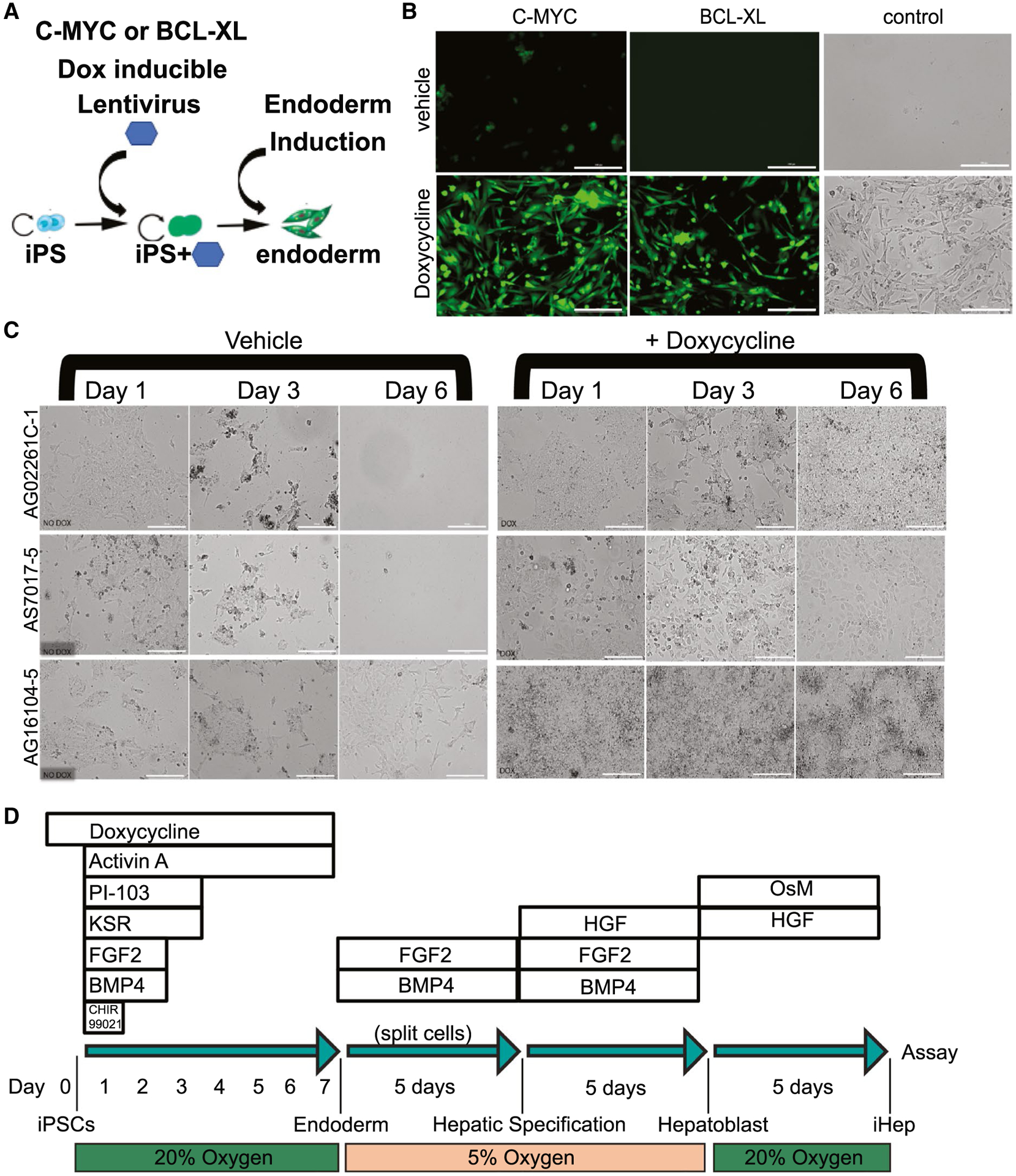

Dox RESCUES ENDODERM INDUCTION INDEPENDENT OF TRANSGENES

We explored artificially activating proliferation while inhibiting apoptosis, to short-circuit cell death and force endoderm induction in our cell lines. We were inspired by Hirose et al., who were able to improve erythroblast differentiation through induction of BCL-XL and cMYC (to inhibit apoptosis and activate cellular proliferation, respectively) for the improved production of erythrocytes from iPSCs.(13) We tested a similar strategy for our induction of endoderm. We chose poorly differentiating iPSC lines (AG02261C-1, AS7017-5, and AG16104-5; Fig. 1) and infected them with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged lentivirus expressing Dox-On BCL-XL or Dox-On cMYC (Fig. 1A,B). We isolated clonal GFP-positive iPSC subclones by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and expanded pure populations of these iPSCs containing integrated BCL-XL or cMYC. Next, we tested endoderm induction, by providing Dox inducing BCL-XL or cMYC (Fig. 1B). Turning on BCL-XL or cMYC immediately rescued these inductions from cellular death. Using this system, we were able to differentiate three poorly differentiating cell lines when either cMYC or BCL-XL was induced by Dox (Fig. 1B). BCL-XL and cMYC inductions were confirmed by quantitative PCR, and generation of endoderm was confirmed by immunohistochemical staining (Supporting Fig. S1B,D).

FIG. 1.

Dox rescues induction to endoderm. (A) Schematic of C-MYC or BCL-XL Dox-inducible transduction and establishment of iPSC lines that were then able to efficiently form definitive endoderm. (B) Immunofluorescence and bright-field images showing induction of definitive endoderm from iPSCs after 6 days using the protocol shown in Supporting Fig. S1A, with and without Dox in iPSCs with established Dox-inducible C-MYC, BCL-XL, or control (no viral transduction) in cell line AS7017-5 (scale bar = 100 μM). Control experiments without a virus rescued the induction of cell line AS7017-5 (n = 2). (C) Bright-field images from three inefficient iPSC lines induced with or without the addition of Dox (no additional transgenes); scale bar = 100 μM (n = 3). (D) Schematic for optimal induction of iPSCs into definitive endoderm (days 0–7) and then to iPSC-Heps. Protocol also referred to as ML1. Abbreviations: HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; iHep, induced hepatocytes; OsM, oncostatin M.

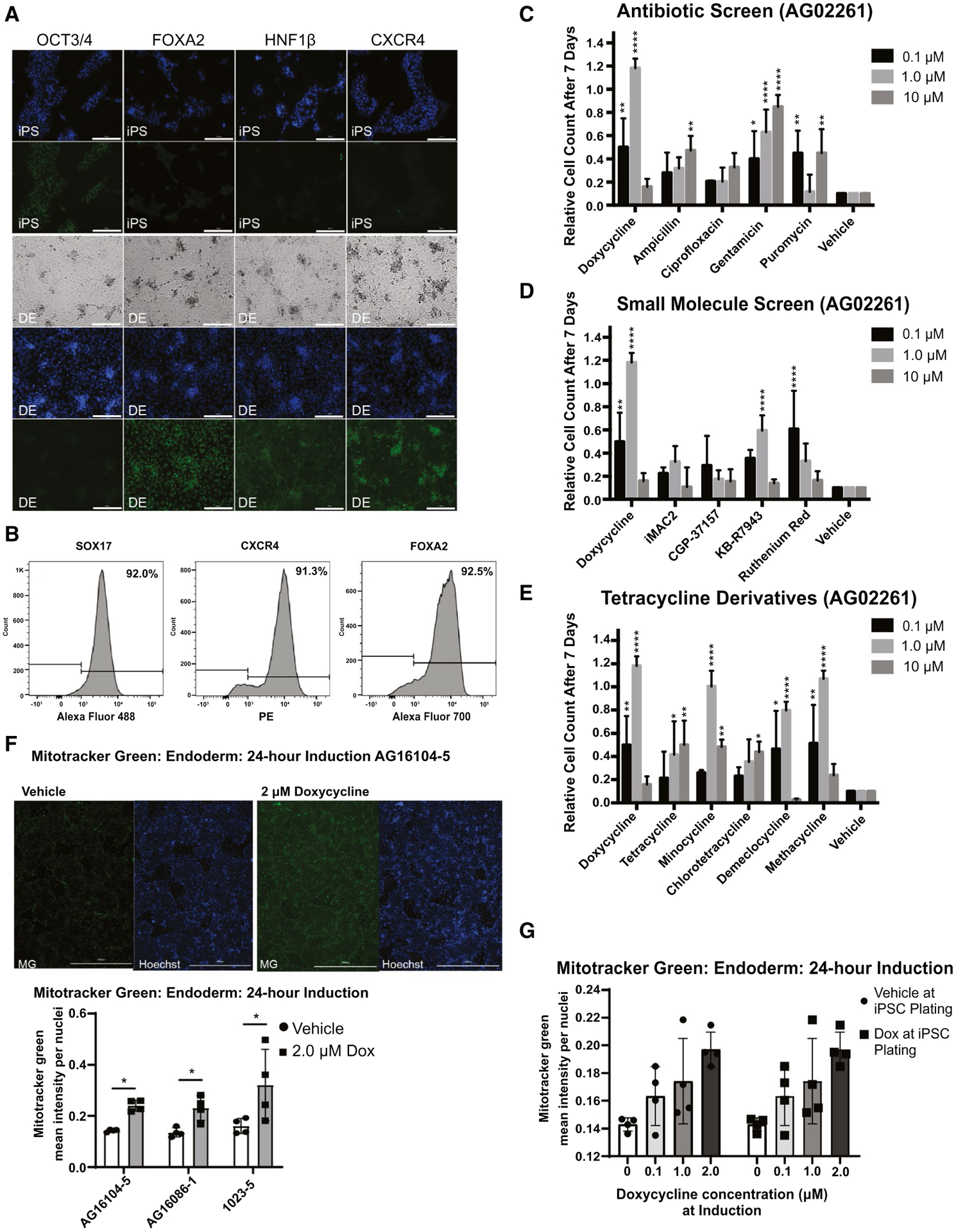

Surprisingly, we noted that control iPSC lines not transduced with lentivirus but treated with Dox also survived induction to iPSC-derived endoderm (Fig. 1B). We confirmed this result using multiple independent poorly differentiating cell lines (Fig. 1C). With this discovery, we abandoned the use of lentivirally transduced iPSCs and focused on characterizing the effects of Dox on iPSC-derived endoderm. To further analyze the ability of Dox to induce endoderm, we titrated iPSC seeding density versus Dox doses on five different lines with variable inducibility (Supporting Fig. S1C). At even the lowest doses of Dox, there was an immediate improvement and most were able to induce to confluency and avoid cell death. Addition of even small concentrations of Dox (0.1–2.0 μM) across a variety of plated cell densities improved many of the iPSCs tested for endoderm induction and even permitted the formation of complete monolayers in many lines in the 96-well format. Because Dox is an antibiotic and is known to inhibit mitochondrial translation, we tested other antibiotic classes, including ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, gentamycin, and puromycin. Compared to Dox, only gentamycin showed a similar statistically significant ability to enhance the survival of cells during induction to endoderm, albeit with altered kinetics at equivalent doses (Fig. 2C and Supporting Fig. S4B). Because there were reports of both Dox and gentamycin affecting mitochondrial calcium channels,(22,23) we tested inhibitors CGP-37157, KB-R7943, and ruthenium red that could inhibit mitochondrial sodium and/or calcium exchanger as well as uptake and release from mitochondria. We also tested inhibitor of mitochondrial apoptosis-induced channel 2. These compounds were not nearly as effective as Dox in two separate lines tested (Fig. 2D and Supporting Fig. S4B).

FIG. 2.

Dox-enhanced endoderm and testing of additional compounds. (A) Immunofluorescence and bright-field images showing induction of iPSC line 1023-5 to definitive endoderm (DE) with Hoechst 33342 nuclear staining in blue and antibody staining for OCT3/4 (POU Class 5 homeobox 1), FOXA2, HNF1β (HNF1 homeobox B), and CXCR4 with Alexa Fluor 488 secondary (green) antibody. Bright-field microscopy shows complete monolayer (scale bar = 200 μM). (B) FACS analysis was used to determine the percentage of SOX17, CXCR4, and FOXA2 expression during in iPSC-derived endoderm (n = 3 technical replicates for two independent cell lines: iPSC 1023-5 and AG12107c, data shown are for cell line iPSC 1023-5, representative experiment; AG12107c data are shown in SupportingFig. S2C). (C) Compound screen for iPSC induction to endoderm using other antibiotics affecting the mitochondria compared to Dox as additives to the protocol. Compounds were added instead of Dox to protocol ML1. Whereas most antibiotics failed to have the same magnitude of an effect, surprisingly gentamycin had a decent dose response. The number of cells is shown measured 7 days after induction compared to the plating density at day 0 (n = 3 technical replicates for each independent cell line). (D) Compound screen for iPSC induction to endoderm using small molecules affecting the mitochondria compared to Dox as additives to the protocol. Compounds were added instead of Dox to protocol ML1. KB-R7943 and ruthenium red showed responses at specific doses in one cell line shown here (AG02261), but not another cell line (AS7192) in Supporting Fig. S4B. The number of cells is shown measured 7 days after induction compared to the plating density at day 0 (n = 3 technical replicates for each independent cell line). (E) Comparison of tetracycline derivatives in iPSC line AG02261. Dox was compared to tetracycline derivatives in its ability to rescue endoderm induction. Minocycline and methacycline showed a similar ability to rescue endoderm at the 1-μM concentration with toxicity at the 10-μM concentration. Demeclocycline showed a similar trend. The number of cells is shown measured 7 days after induction compared to the plating density at day 0 (n = 3 technical replicates for each independent cell line). (F) Mitotracker Green analysis of 24-hour induced endoderm including immunofluorescence (scale bar = 1,000 μM) for representative line AG16104-5 and quantifications for three cell lines (n = 4 technical replicates for each cell line). (G) Mitotracker Green analysis of 24-hour induced endoderm with low-dose titration of Dox in line 1023-5 (n = 4 technical replicates for one cell line). Data analyzed by Student t test or two-way ANOVA and presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Abbreviation: OCT, octamer binding transcription factor.

We also tested tetracycline derivatives for their ability to rescue induction to endoderm and found that, compared to Dox, only minocycline, demeclocycline, and methacycline showed similar trends in two different cell lines. The parent compound, tetracycline, and derivative, chlorotetracycline, did not appear to work as effectively (Fig. 2E and Supporting Fig. S4A).

We next tested the effects of Dox on iPSC growth and found that it was able to improve daily growth kinetics in nearly all lines tested (Supporting Fig. S2A). A dose-response study demonstrated a beneficial effect of Dox up to 3 μM, but eventual toxicity at higher levels (Fig. 4B and Supporting Fig. S2B). We validated induction of iPSCs to endoderm in our protocol by direct immunohistochemical staining for markers of endoderm, including forkhead box A2 (FOXA2), hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 beta (HNF1β), and C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4; Fig. 2A), and by flow cytometry analysis that showed 92% SRY-box transcription factor 17 (SOX17), 91% CXCR4, and 93% FOXA2 expression as typical results (Fig. 2B and Supporting Fig. S2C). Our protocol, for convenience designated ML1 (Fig. 1D), showed an efficient induction of endoderm. More important, the ML1 protocol allowed induction of complete monolayers of endoderm from nearly all iPSC lines tested, even those that failed other protocols recommended for poorly differentiating iPSCs.(15,17)

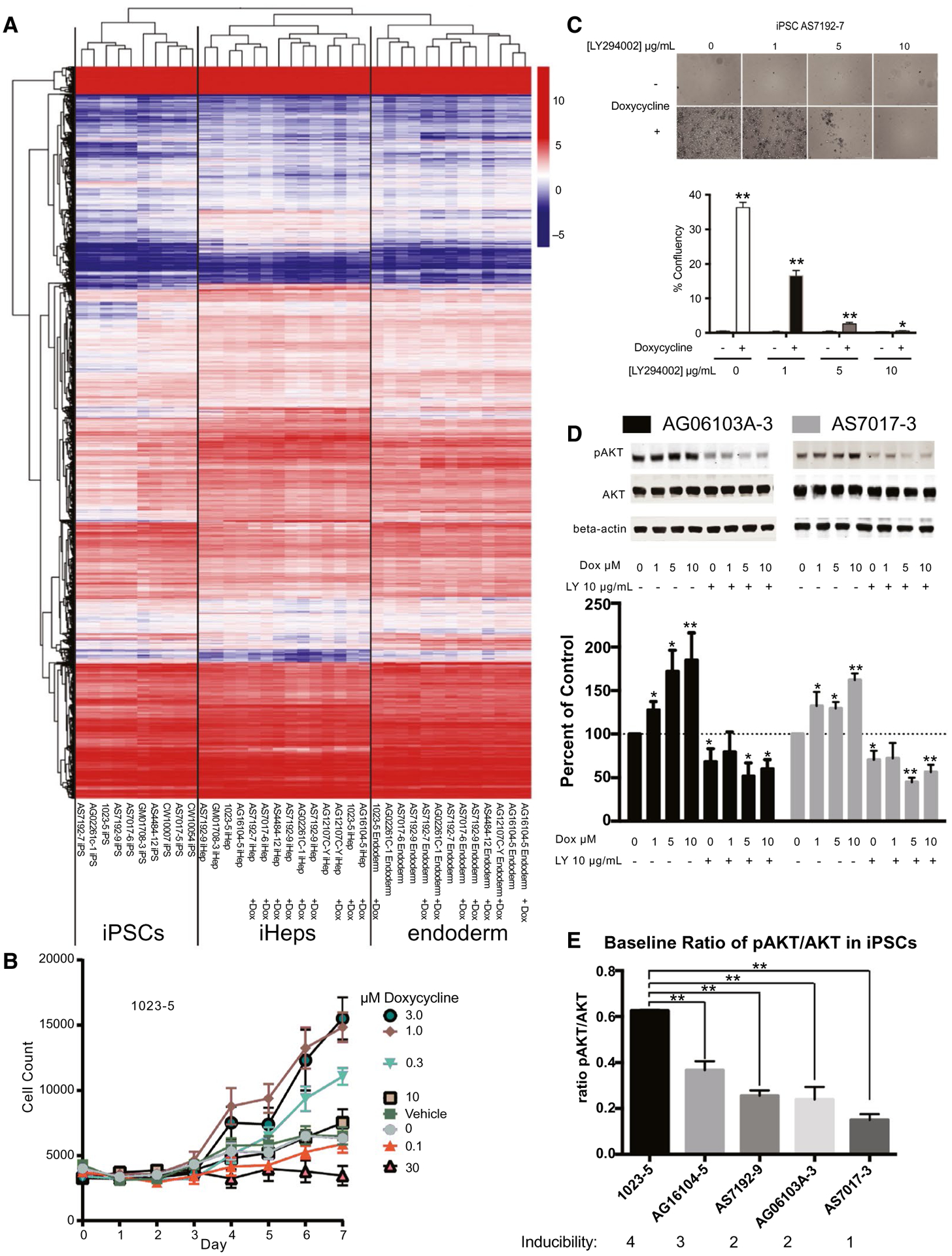

FIG. 4.

Mechanism of Dox effects on definitive endoderm induction. (A) RNA-seq of iPSC, definitive endoderm, and final iPSC-Heps cluster appropriately after unbiased hierarchical clustering analysis with and without Dox-enhanced differentiation during the endoderm phase. (B) Titration of Dox showed that there was an optimal level of Dox and a toxic level (n = 3 biological replicates in three different cell lines, cell line 1023-5 shown here, and additional titrations shown in Supporting Fig. S2B). (C) Dox-enhanced definitive endoderm induction can be inhibited by LY294002 in a dose-dependent manner (iPSC line AS7192-7; n = 4 technical replicates in three different cell lines). (D) Escalating doses of Dox cause increased P-AKT/AKT ratio. LY294002-inhibited P-AKT levels are not reversible by increasing doses of Dox (iPSC lines AG06103A-3 and AS7017-3 shown; n = 3 technical replicates in three different cell lines). Western blottings quantified with the Odyssey LiCor imaging system. (E) Preexisting baseline ratio levels of P-AKT/AKT in individual iPSC lines correlate with the ability to induce these lines to definitive endoderm (n = 3 technical replicates for each cell line). Data were analyzed by Student t test versus control and error bars represent 95% CI, presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

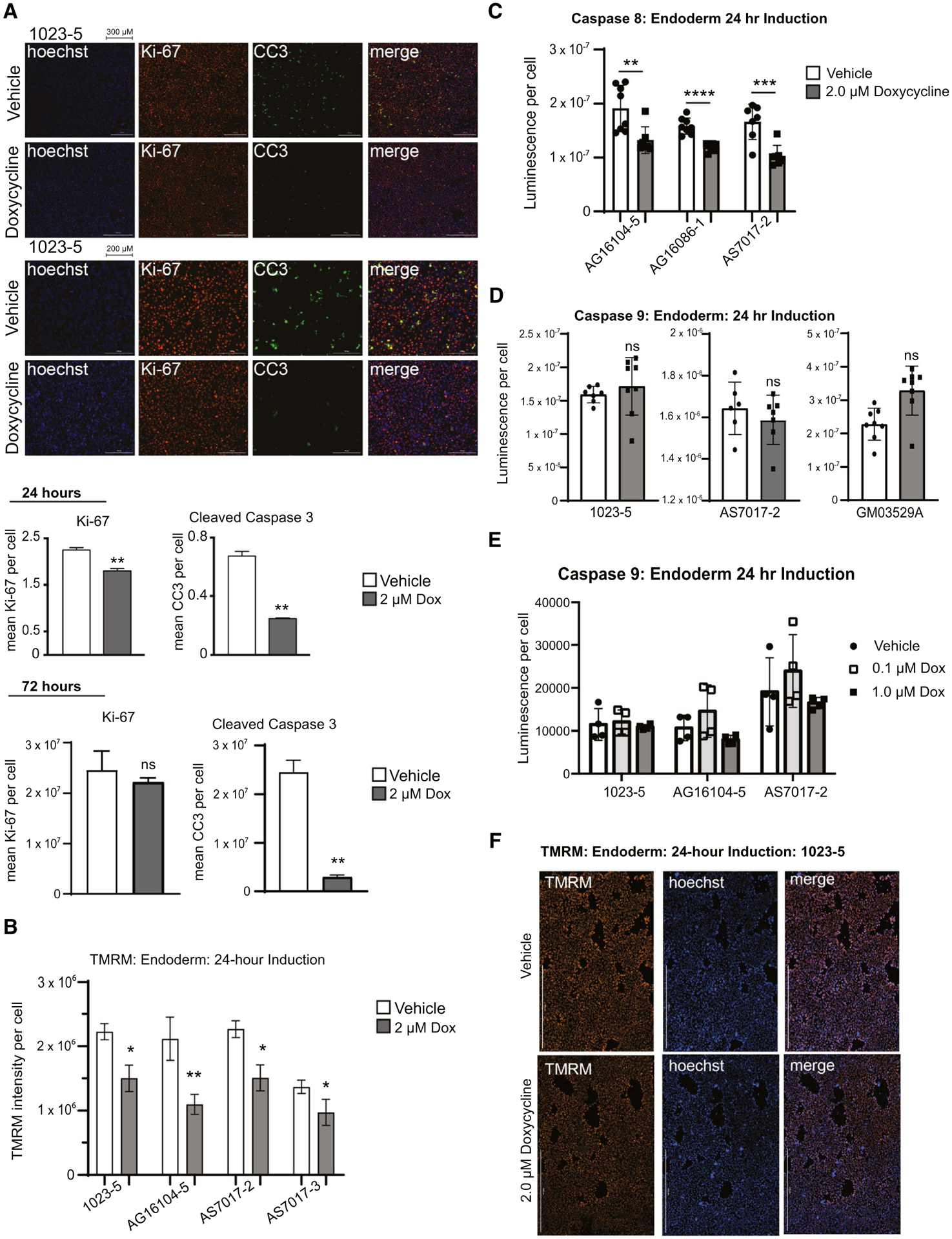

EARLY REDUCTION OF CLEAVED CASPASE 3 CLEAVAGE

As a first step to understand the mechanism by which Dox was affecting induction of iPSCs to endoderm, we explored whether Dox was affecting cell proliferation, cell death, or both. We induced endoderm using protocol ML1 for 24 hours and then fixed and stained cells for cleaved caspase 3 (CC3) and the proliferation marker, Ki-67. After quantification, we noted both significant Ki-67 staining and CC3 staining, as expected (Fig. 3A and Supporting Fig. S3A). In the presence of Dox, during this early induction time point, we noted a >50% decrease in CC3 staining with only a very slight decrease in overall Ki-67 levels over four different cell-line experiments. At 72 hours, there was no difference in Ki-67 levels, and with Dox treatment, CC3 staining was extensively reduced. We concluded that this early reduction in apoptosis leads to sustained proliferation, leading to successful induction. We further found that unlike older protocols, using ML1, we could passage and split cells between endoderm and hepatic specification up to 4-fold and they would grow into complete monolayers, achieving a valuable expansion (Fig. 1D). To better characterize whether the extrinsic or intrinsic apoptosis pathways could be involved, we performed assays for caspase 8 or caspase 9 activation (Fig. 3C,D and E). Low-dose Dox appeared to inhibit the caspase 8 pathway, whereas there was no significant change in the caspase 9 pathway.

FIG. 3.

Dox reduces apoptosis and increases mitochondrial mass. (A) Immunofluorescence of iPSC line 1023-5 on day 2 of induction for Hoechst 33342, Ki-67, CC3, and combined showed greatly decreased CC3 staining in the presence of Dox. At this early time point (day 2), there was a slight but significant decrease in Ki-67. First two rows are 10× with the scale bar at 300 μm and bottom two rows 20× with a 200-μm scale bar. Quantification is shown at 24 and 72 hours (n = 3 different cell lines with three technical replicates each). (B) TMRM staining of iPSCs after 24-hour induction shows decreased membrane polarization in four induced donor lines at 2 μM of Dox (n = 4 technical replicates for four different cell lines each). (C) Assay for caspase 8 staining in endoderm after 24 hours shows decreased caspase 8 activation in three donor lines (n = 8 technical replicates for each). (D) Assay for caspase 9 staining in endoderm after 24 hours shows no statistical difference in caspase 9 activation at 2 μM of Dox (n = 8 technical replicates for each of three different cell lines). (E) Assay for caspase 9 levels for endoderm at 24-hour induction at low-dose titrated levels of Dox across three cell lines (n = 4 technical replicates). (F) Immunofluorescence of iPSC line 1023-5 for TMRM staining at 24 hours from quantification in Fig. 3B. Scale bar at 1,000 μm (n = 4 technical replicates in four different cell lines). Data were analyzed by Student t test or two-way ANOVA and presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

INTERROGATION OF MECHANISM REVEALS MULTIPLE PATHWAY INTERACTIONS

Given its function as an antibiotic, early studies of Dox identified it as a mitochondrial translational inhibitor.(24) However, newer studies have shown additional functions. For example, in some tumor lines, Dox can alter numerous metabolic genes,(25,26) with even long-term epigenetic modifications noted in T cells.(27)

We hypothesized that TGFβ induction through activin A limits cell division and, under certain cellular scenarios, activates the apoptotic machinery. We speculated that perhaps Dox, by inhibiting mitochondrial function, was interfering with the mitochondrial apoptosis machinery to fully engage. Therefore, to characterize mitochondria, we performed Mitotracker staining with and without doxycycline on iPSCs induced to endoderm (Fig. 2F,G and Supporting Fig. S3B). Treatment of induced cells with low-dose Dox showed increased MitoTracker Green staining, consistent with an increase of mitochondrial mass. Low-dose Dox therefore does not affect mitochondria in induced iPSCs in the same way that it does at higher doses in cancer stem cells.(28,29) To compare the effects of Dox, ruthenium red, KB-R7843, and gentamycin on mitochondrial mass, we also repeated the experiment and found that all compounds showed similar effects on mitochondrial mass in endoderm at low doses (Supporting Fig. S3C,D). To validate that the addition of these compounds still formed endoderm, we confirmed staining for FOXA2 (Supporting Fig. S3E). To further evaluate mitochondrial polarization, we treated cells with vehicle or Dox, followed by staining for the mitochondrial membrane potential–dependent dye, tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM).(30) Treatment of cells with low-dose (2 μM) Dox for 24 hours showed a significant decrease in TMRM staining (Fig. 3B,F).

We further sought to delineate the pathways that were leading to increased apoptosis during the endoderm inductive phase. Induction of endoderm by high-dose activin A drives NODAL pathways by binding activin A receptors 1 and 2, thus driving the phosphorylation of SMAD2 and 3.(31) The phospho-SMAD2/3 complex recruits SMAD4 and enters the nucleus to activate transcription of multiple downstream targets.(31) There are several published mechanisms for activated SMAD2/3/4 connection to the apoptotic pathway. First, TGFβ is known to induce apoptosis through SMAD-mediated DAPK expression.(32) Second, TGFβ receptor (activin A–activated) is also directly connected to a SMAD4 mitochondrial translocation and cyctochrome c oxidase subunit II interaction.(33) These findings might explain the apoptotic propensity of iPSCs in certain cell lines.

In order to more definitively identify mechanisms involved, we attempted to induce and differentiate eight iPSCs with and without Dox in pairs. Of the eight iPSCs without Dox, we were able to generate sufficient endoderm from five lines, and sufficient iPSC-Heps in four samples, to extract quality RNA (Supporting Fig. S5A). In contrast, using Dox, we easily generated enough endoderm and iPSC-Heps for RNA-seq from all eight samples. We performed RNA-seq with the samples that passed quality-control tests. After blinded clustering of gene expression analysis, we noted that all endoderm, iPSC-Heps, and iPSCs clustered appropriately in our heatmap without bias for treatment with or without Dox (Fig. 4A).

Up-regulated and down-regulated RNA pathways in endoderm are shown in Supporting Table S1. We found that 205 genes were significantly down-regulated and 47 up-regulated (adjusted P value of 0.05) when cells were treated with Dox. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis revealed cellular growth and proliferation as well as cell death and survival as within top molecular and cellular functions during induction to endoderm. However, these pathways appeared largely balanced without clear targets that were overwhelmingly favored. Notably, levels of caspase 3 were minimally, but significantly, reduced. In addition, inhibition of matrix metalloproteases (MMPs), a known target of Dox, was a top canonical pathway. The connection between MMPs and apoptosis has been explored(34); however, only tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 4 inhibition would be consistent with decreased apoptosis in this data set.

To further explore affected protein pathways, including regulatory protein modifications such as protein phosphorylation, we performed a quantitative antibody array (Moon Bio) on protein extracts from a 6-day induced iPSC-endoderm line with and without Dox (Supporting Table S2). Increased phosphorylation was noted after Dox exposure in protein pathways driving proliferation and cell survival, including ELK-1 Ser383, ACK1 Tyr284, DOK-2 Tyr299, MEF2C Ser396, and HER2 Tyr1221/Tyr1222.(35–39) Phosphorylation of ACK1 Tyr284 has been shown to lead to increased AKT phosphorylation,(35) and we did note increased phospho-AKT (P-AKT) within the antibody screen. In addition, we also noted that protein 14-3-3 zeta showed a 1.6-fold up-regulation in Dox-treated endoderm. 14-3-3 zeta promotes overall cell survival by sequestering BCL2-associated X, apoptosis regulator and BCL2-associated agonist of cell death in the cytoplasm.(40) Overall, this total combination of changes significantly favors survival and proliferation of endoderm.

Therefore, to confirm that AKT was indeed hyper-phosphorylated in the presence of Dox, we used four iPSCs and performed a Dox dose-response experiment. Treatment of iPSCs during induction of endoderm showed protection from cell death as we previously showed, which was entirely reversible with increasing doses of LY294002 (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, induction at 1, 5, and 10 μM of Dox in short-term experiments showed dose-dependent increases in P-AKT levels entirely reversible with LY294002 (Fig. 4D). Clearly, Dox treatment at this early time point can indeed increase P-AKT levels. To demonstrate that there was a balance of enhanced growth and differentiation versus toxicity between a low dose (<10 μM) and high dose (>10 μM) of Dox, we titrated Dox in three separate cell lines (Fig. 4B and Supporting Fig. S2B).

We next set out to answer why different iPSCs show differential sensitivity to activin A–induced cell death. AKT directly interacts with unphosphorylated SMAD3 through a mechanism independent of AKT kinase activity.(41) By sequestering unphosphorylated AKT, the complex can default into apoptosis.(41) Therefore, preexisting levels of P-AKT could determine the efficiency of induction. In order to characterize whether such levels could be leading to the noted differences between cell lines, we characterized the inducibility of cell lines as excellent (four stars), average (three stars), and poorly inducible cell lines (two and one stars). We then compared preexisting levels of P-AKT/AKT in these iPSCs (Fig. 4E). Indeed, excellent inducers showed baseline P-AKT/AKT ratios of >0.3, supporting the idea that some cell lines have higher preexisting P-AKT/AKT levels.

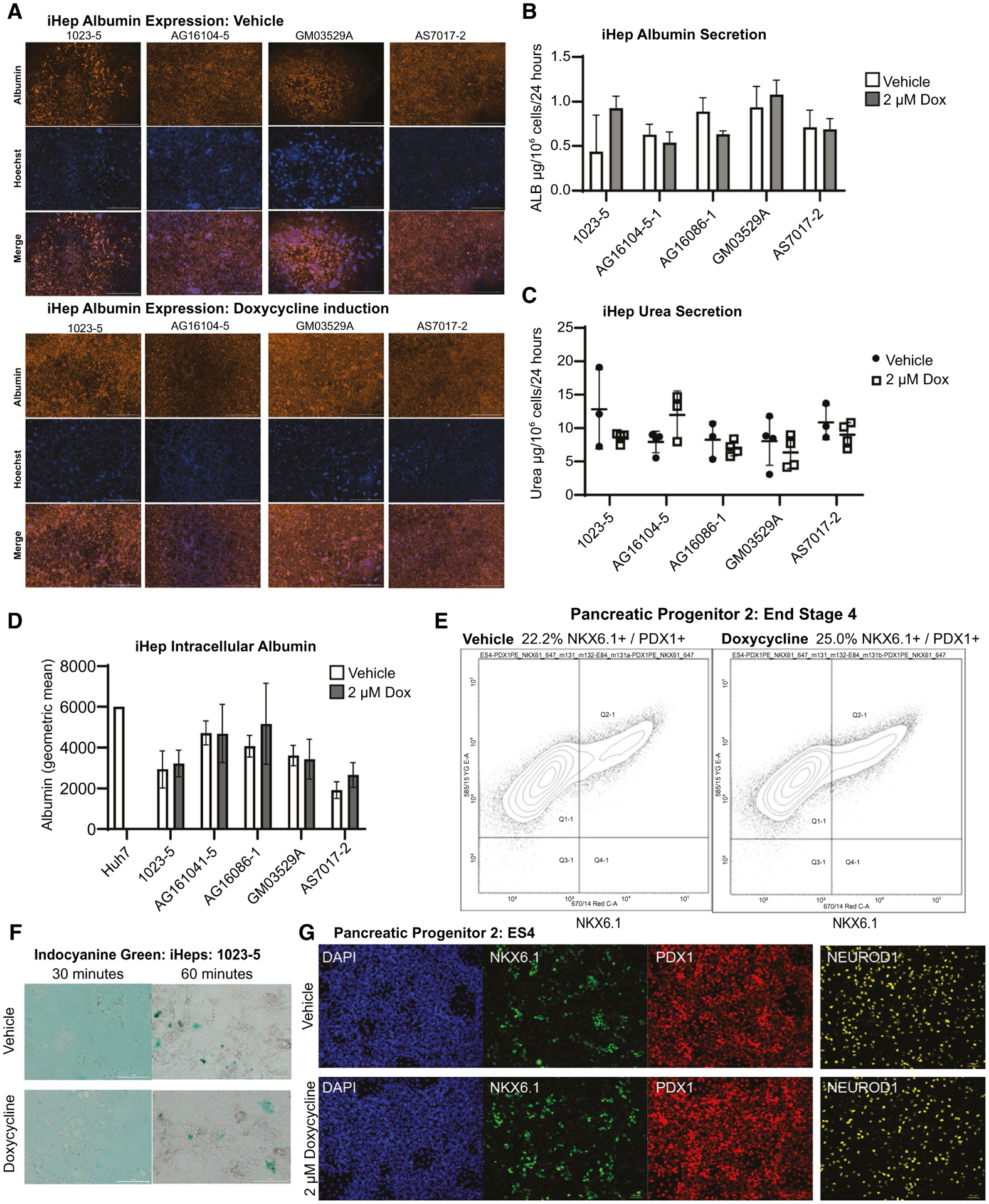

ENHANCED ENDODERM INDUCTION DOES NOT ALTER THE FINAL HEPATOCYTE MATURITY

We wanted to confirm whether Dox treatment during endoderm induction affected final iPSC-derived hepatocyte differentiation. To characterize this, first using RNA-seq data on iPSC-Heps (Fig. 4A), we did not observe any statistically significant divergence in iPSC-Hep gene expression. Next, we extensively analyzed phenotypic parameters of iPSC-Heps. Quantitatively, addition of Dox did not affect overall albumin expression by direct immunohistochemistry, but did enhance formation of monolayers (Fig. 5A). We also performed flow cytometry analysis and quantified iHep intracellular albumin, which also showed no statistical difference within single iPSC donors (Fig. 5D). There was no difference in iHep albumin or urea secretion (Fig. 5B,C). iHeps from both protocols showed similar Cardiogreen uptake and secretion (Fig. 5F and Supporting Fig. S4C). Finally, we tested cytochrome P450 3A4 activity, which also showed no changes within donors (Supporting Fig. S4D).

FIG. 5.

Dox-supplemented endoderm hepatocyte and pancreatic phenotypes. (A) Immunofluorescence of iPSC-derived hepatocytes (iHep) lines 1023-5, AG16104-5, GM03529A, and AS7017-2 at the end of differentiation for albumin, Hoechst 33342, and merged. iHeps produced with Dox supplementation during endoderm induction showed more consistent formation of complete sheets of cells. All rows are 20× imaging with stitching feature, with a 2,000-μm scale bar (n = 2 technical replicates in four different cell lines). (B) Quantification of iHep albumin secretion into media at the end of differentiation measured at μg per 106 cells per 24 hours. No significant changes were noted in the five cell lines differentiated with and without Dox exposure during endoderm induction (n = 4 technical replicates for each cell line). (C) Assay for iHep urea at the end of differentiation measured at mg/dL/106 cells per 24 hours. No significant changes were noted in the five cell lines differentiated with and without Dox exposure during endoderm induction (n = 4 technical replicates for each cell line). (D) Quantification of iHep intracellular albumin at the end of differentiation by flow cytometry shows no significant differences in five cell lines differentiated with and without Dox exposure during endoderm induction. As a control, Huh7 cells were also tested using vehicle condition. The geometric mean of albumin concentration is shown (n = 3 technical replicates for each cell line). (E) Quantification of differentiation of pancreatic progenitor 2 cells at the end of stage 4. NKX6.1 (NK6 homeobox 1)-positive and PDX1 (pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1)-positive cells quantified by flow cytometry after differentiation with and without Dox exposure during endoderm induction. Though there was no significant difference, there was a slight trend for increased NKX6.1/PDX1–positive cells in Dox-treated cells (n = 4 technical replicates). (F) Qualitative assessment of Indocyanine Green (Cardiogreen) uptake (at 30 minutes) and secretion (at 60 minutes) by iHeps. Representative cell line 1023-5 shown here and additional experiments shown in Supporting Fig. S4C (n = 1 technical replicate). (G) Immunofluorescence of stem-cell–derived pancreatic progenitor cells at stage 4 stained for antibodies for NKX6.1, PDX1, NEUROD1 (neuronal differentiation 1), and DAPI with and without Dox exposure during the endoderm differentiation stage. Imaging was performed at 20× with a 200-μm scale bar shown (n = 1 technical replicates). Data were analyzed by Student t test versus control and presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Abbreviations: ALB, albumin; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

ADDITION OF Y-27632 PLUS Dox CAN ENHANCE SOME CELL LINES

To determine the minimum medium additives in our differentiation protocol, we performed a systematic elimination experiment. In order to achieve efficient differentiation in most of our lines, we found that all of our additives were required (Supporting Fig. S5D). In our extensive attempt to differentiate numerous iPSCs, we did note rare cell lines that continued to undergo significant apoptosis. Realizing that apoptosis can be driven by additional pathways, such as the RHO kinase pathway,(42) we tested the addition of Y-27632. By itself, Y-27632 did not rescue resistant lines. Because both Y-27632 and Dox are considered to work on different pathways, we tried adding Dox and Y-27632 together to poorly differentiating cell lines (Supporting Fig. S5G). Using this modified protocol, we were able to then differentiate 42 iPSCs from Supporting Table S3 and an additional 28 iPSC lines from the Maher lab to fully confluent wells for downstream analysis. In addition, given Dox’s previously reported role in aiding iPSC growth,(43) we also found that addition of Dox with Y-27632 helped improve iPSC survival during single-cell FACS sorting (Supporting Fig. S5B).

Endoderm is also an intermediate toward pancreatic lineage differentiation. To confirm that Dox as an additive could be used in pancreatic β-cell differentiation, we performed staged differentiation to endoderm and pancreatic progenitors (Fig. 5E,G and Supporting Fig. S5C,E,F). Although differences were not significant, there was some hint from NKX6.1 staining that Dox improves pancreatic differentiation. Indeed, we were able to confirm that the use of Dox does not lead to any decrement in the ability of induced endoderm to differentiate to yet another downstream derivative (pancreatic endoderm).

Discussion

Differentiation of iPSCs to hepatocytes has long been a challenging process. Because of activin A–induced apoptosis, iPSC induction to endoderm is often unreliable; this causes frustrating expenditures of time and resources and, in many cases, prevents the completion of experiments with patient-derived cells. Dox seems to play a dual role in the case of helping endoderm induction. During the early phase, it appears to inhibit apoptosis as shown by decreased CC3. By allowing cells to survive this initial wave of activin A–induced toxicity during the first 2 days, over the following days AKT phosphorylation drives cell survival. By days 9–11, splitting cells results in up to a 4-fold increase in cell number. During the first several days of induction, the slightly reduced Ki-67 levels during the first several days could be a function of balanced Dox inhibition of mitochondrial energy production and is probably overcome by increased mitochondrial content, as shown by Mitotracker staining.

Dox was developed from Terramycin, a naturally occurring antibiotic isolated from the actinomycete, Streptomyces rimosus, in 1950.(44) Interestingly, although the derivative antibiotics, Dox, minocycline, and methacycline, were able to effectively rescue induction, the parent compound, tetracycline, was not. Some published protocols routinely use antibiotics in differentiation protocols, likely to prevent infection, but their use can obviously affect differentiation by modulating survival of cells.

Maintenance of pluripotency in iPSCs is generally a metabolic process, and studies have tried to show that during successful endoderm induction, there is a switch from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation.(45,46) However, Dox is known to inhibit mitochondrial function and therefore reduce oxidative phosphorylation. Inhibition of mitochondrial metabolism and successful induction of endoderm are contrary to the notion that endoderm induction requires an oxidative metabolic switch. Similarly, it was previously reported that deletion of cMYC leads to spontaneous primitive endoderm differentiation from iPSCs.(47) cMYC is thought to regulate some of the metabolic switching between glycolysis and oxidative metabolism; however, newer work confirms that differentiation to endoderm does not appear to be affected by MYC reexpression or change of the metabolic switch.(48) Our results confirm that induced cMYC expression is entirely compatible with endoderm induction. Clearly, there is still much to learn about the induction of endoderm.

The mechanism of Dox enhancing endoderm induction by P-AKT is also supported by pathways highlighted by our RNA-seq. For example, we noted that the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway that induces apoptosis was also affected by down-regulation of caveolin 1,(49) and that furthermore CAV1 can also interact with the TGFβ receptor influencing SMAD2 phosphorylation.(50) We also noted that gentamicin rescued endoderm induction in our limited screens and though we tried to find a common mechanism with doxycycline, possibly related to mitochondrial calcium channels, we were not able to confirm this.

It is important to underline that, in our endoderm studies and in limited studies in HeLa cells, low-dose Dox appears to show decreased extrinsic apoptosis.(51) These experiments highlight that additional studies are necessary to identify the precise target proteins modulated by Dox. It is also important to stress that enhancement of endoderm induction works best with Dox present in the days preceding induction with activin A, as noted in the protocol. This protocol has revitalized our entire differentiation pipeline and allowed our lab to perform experiments that were previously out of reach. With the addition of Dox, differentiation of iPSC-Heps is possible from any patient and almost any line. We look forward to additional modifications to the protocol enabling complete maturation of iPSC-Heps to fully mature hepatocytes from each of the zonal areas of the liver lobe.

Here, we show that Dox is an effective and compatible compound for the induction of iPSCs to endoderm that significantly enhances survival of endoderm. Because endoderm is also a precursor to other tissues, such as pancreatic β cells and intestinal epithelial cells, this protocol has significant implications for improved differentiation of iPSCs to any endoderm-derived tissue. This has significant implications for cellular therapy, but also highlights the importance to understand Dox effects on cellular metabolism and alternative pathways when used in models of gene regulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment:

This study was supported, in part, by NIH Grant K08DK098270 to A.N.M., the SFSU CIRM Bridges 2.0 (SFSUCIRMEDUC2-08391) to C.P., the UCSF Pathology Department and UCSF Liver Center (P30 DK026743), NIH grant R01DK118421 to J.B.S, and NIH grant R21DK118380 to J.J.M.

Abbreviations:

- AKT

protein kinase B

- BCL-XL

B-cell lymphoma-extra large

- BMP4

bone morphogenetic protein 4

- CC3

cleaved caspase 3

- cMYC

MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor

- CXCR4

C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4

- Dox

doxycycline

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- FGF2

fibroblast growth factor 2

- FOXA2

forkhead box A2

- HNF1β

hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 beta

- iPSCs

induced pluripotent stem cells

- iPSC-Heps

iPSC-derived hepatocytes

- KSR

knockout serum replacement

- P-AKT

phospho-AKT

- RNA-seq

RNA-sequencing

- SMAD

mothers against decapentaplegic homolog

- SOX17

SRY-box transcription factor 17

- TMRM

tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Mattis consults for HepaTx and Ambys. Dr. Maher consults for BioMarin.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.31898/suppinfo.

REFERENCES

- 1).Takayama K, Morisaki Y, Kuno S, Nagamoto Y, Harada K, Furukawa N, et al. Prediction of interindividual differences in hepatic functions and drug sensitivity by using human iPS-derived hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:16772–16777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Pournasr B, Duncan SA. Modeling inborn errors of hepatic metabolism using induced pluripotent stem cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017;37:1994–1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Wang H, Luo X, Yao L, Lehman DM, Wang P. Improvement of cell survival during human pluripotent stem cell definitive endoderm differentiation. Stem Cells Dev 2015;24:2536–2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Shinohara M, Choi H, Ibuki M, Yabe SG, Okochi H, Miyajima A, et al. Endodermal differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells using simple dialysis culture system in suspension culture. Regen Ther 2019;12:14–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Sahin H, Abdullazade S, Sanci M. Mature cystic teratoma of the ovary: a cutting edge overview on imaging features. Insights Imaging 2017;8:227–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Brown S, Teo A, Pauklin S, Hannan N, Cho CH, Lim B, et al. Activin/Nodal signaling controls divergent transcriptional networks in human embryonic stem cells and in endoderm progenitors. Stem Cells 2011;29:1176–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Liu YE, Festing M, Thompson JC, Hester M, Rankin S, El-Hodiri HM, et al. Smad2 and Smad3 coordinately regulate cranio-facial and endodermal development. Dev Biol 2004;270:411–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Charlier E, Condé C, Zhang J, Deneubourg L, Di Valentin E, Rahmouni S, et al. SHIP-1 inhibits CD95/APO-1/Fas-induced apoptosis in primary T lymphocytes and T leukemic cells by promoting CD95 glycosylation independently of its phosphatase activity. Leukemia 2010;24:821–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Wang WJ, Kuo JC, Yao CC, Chen RH. DAP-kinase induces apoptosis by suppressing integrin activity and disrupting matrix survival signals. J Cell Biol 2002;159:169–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Zhao M, Mishra L, Deng CX. The role of TGF-beta/SMAD4 signaling in cancer. Int J Biol Sci 2018;14:111–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Cai J, DeLaForest A, Fisher J, Urick A, Wagner T, Twaroski K, et al. Protocol for directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells toward a hepatocyte fate. In: StemBook. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Stem Cell Institute; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Ludwig TE, Bergendahl V, Levenstein ME, Yu J, Probasco MD, Thomson JA. Feeder-independent culture of human embryonic stem cells. Nat Methods 2006;3:637–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Hirose SI, Takayama N, Nakamura S, Nagasawa K, Ochi K, Hirata S, et al. Immortalization of erythroblasts by c-MYC and BCL-XL enables large-scale erythrocyte production from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Reports 2013;1:499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Pagliuca FW, Millman JR, Gürtler M, Segel M, Van Dervort A, Ryu JH, et al. Generation of functional human pancreatic β cells in vitro. Cell 2014;159:428–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Si-Tayeb K, Noto FK, Nagaoka M, Li J, Battle MA, Duris C, et al. Highly efficient generation of human hepatocyte-like cells from induced pluripotent stem cells. Hepatology 2010;51: 297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Ma X, Duan Y, Tschudy-Seney B, Roll G, Behbahan IS, Ahuja TP, et al. Highly efficient differentiation of functional hepatocytes from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Transl Med 2013;2:409–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Ang LT, Tan AKY, Autio MI, Goh SH, Choo SH, Lee KL, et al. A roadmap for human liver differentiation from pluripotent stem cells. Cell Rep 2018;22:2190–2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Gao Y, Zhang X, Zhang L, Cen J, Ni X, Liao X, et al. Distinct gene expression and epigenetic signatures in hepatocyte-like cells produced by different strategies from the same donor. Stem Cell Reports 2017;9:1813–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Rashid ST, Corbineau S, Hannan N, Marciniak SJ, Miranda E, Alexander G, et al. Modeling inherited metabolic disorders of the liver using human induced pluripotent stem cells. J Clin Invest 2010;120:3127–3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Xu X, Browning VL, Odorico JS. Activin, BMP and FGF pathways cooperate to promote endoderm and pancreatic lineage cell differentiation from human embryonic stem cells. Mech Dev 2011;128:412–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).McLean AB, D’Amour KA, Jones KL, Krishnamoorthy M, Kulik MJ, Reynolds DM, et al. Activin A efficiently specifies definitive endoderm from human embryonic stem cells only when phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling is suppressed. Stem Cells 2007;25:29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Schwartz J, Holmuhamedov E, Zhang X, Lovelace GL, Smith CD, Lemasters JJ. Minocycline and doxycycline, but not other tetracycline-derived compounds, protect liver cells from chemical hypoxia and ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibition of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2013;273:172–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Sastrasinh M, Weinberg JM, Humes HD. The effect of gentamicin on calcium uptake by renal mitochondria. Life Sci 1982;30:2309–2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Chatzispyrou IA, Held NM, Mouchiroud L, Auwerx J, Houtkooper RH. Tetracycline antibiotics impair mitochondrial function and its experimental use confounds research. Cancer Res 2015;75:4446–4449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Lamb R, Ozsvari B, Lisanti CL, Tanowitz HB, Howell A, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, et al. Antibiotics that target mitochondria effectively eradicate cancer stem cells, across multiple tumor types: treating cancer like an infectious disease. Oncotarget 2015;6:4569–4584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Ahler E, Sullivan WJ, Cass A, Braas D, York AG, Bensinger SJ, et al. Doxycycline alters metabolism and proliferation of human cell lines. PLoS One 2013;8:e64561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Becker E, Bengs S, Aluri S, Opitz L, Atrott K, Stanzel C, et al. Doxycycline, metronidazole and isotretinoin: do they modify microRNA/mRNA expression profiles and function in murine T-cells? Sci Rep 2016;6:37082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Zhong W, Chen S, Qin Y, Zhang H, Wang H, Meng J, et al. Doxycycline inhibits breast cancer EMT and metastasis through PAR-1/NF-kappaB/miR-17/E-cadherin pathway. Oncotarget 2017;8:104855–104866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Yang B, Lu Y, Zhang AI, Zhou A, Zhang L, Zhang L, et al. Doxycycline induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation and invasion of human cervical carcinoma stem cells. PLoS One 2015;10:e0129138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Dijk SN, Protasoni M, Elpidorou M, Kroon AM, Taanman JW. Mitochondria as target to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis of cancer cells: the effects of doxycycline and gemcitabine. Sci Rep 2020;10:4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Yu JS, Ramasamy TS, Murphy N, Holt MK, Czapiewski R, Wei SK, et al. PI3K/mTORC2 regulates TGF-beta/Activin signalling by modulating Smad2/3 activity via linker phosphorylation. Nat Commun 2015;6:7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Jang CW, Chen CH, Chen CC, Chen JY, Su YH, Chen RH. TGF-beta induces apoptosis through Smad-mediated expression of DAP-kinase. Nat Cell Biol 2002;4:51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Pang L, Qiu T, Cao X, Wan M. Apoptotic role of TGF-beta mediated by Smad4 mitochondria translocation and cytochrome c oxidase subunit II interaction. Exp Cell Res 2011;317:1608–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Mannello F, Luchetti F, Falcieri E, Papa S. Multiple roles of matrix metalloproteinases during apoptosis. Apoptosis 2005;10:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Zhao X, Lv C, Chen S, Zhi F. A role for the non-receptor tyrosine kinase ACK1 in TNF-alpha-mediated apoptosis and proliferation in human intestinal epithelial caco-2 cells. Cell Biol Int 2018;42:1097–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Lavaur J, Bernard F, Trifilieff P, Pascoli V, Kappes V, Pages C, et al. A TAT-DEF-Elk-1 peptide regulates the cytonuclear trafficking of Elk-1 and controls cytoskeleton dynamics. J Neurosci 2007;27:14448–14458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Shinohara H, Inoue A, Toyama-Sorimachi N, Nagai Y, Yasuda T, Suzuki H, et al. Dok-1 and Dok-2 are negative regulators of lipopolysaccharide-induced signaling. J Exp Med 2005;201:333–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Pon JR, Marra MA. MEF2 transcription factors: developmental regulators and emerging cancer genes. Oncotarget 2016;7:2297–2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39).Frogne T, Laenkholm AV, Lyng MB, Henriksen KL, Lykkesfeldt AE. Determination of HER2 phosphorylation at tyrosine 1221/1222 improves prediction of poor survival for breast cancer patients with hormone receptor-positive tumors. Breast Cancer Res 2009;11:R11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Shimada T, Fournier AE, Yamagata K. Neuroprotective function of 14-3-3 proteins in neurodegeneration. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:564534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41).Conery AR, Cao Y, Thompson EA, Townsend CM Jr., Ko TC, Luo K. Akt interacts directly with Smad3 to regulate the sensitivity to TGF-beta induced apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol 2004;6:366–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42).Shi J, Wei L. Rho kinase in the regulation of cell death and survival. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2007;55:61–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43).Chang MY, Rhee YH, Yi SH, Lee SJ, Kim RK, Kim H, et al. Doxycycline enhances survival and self-renewal of human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Reports 2014;3:353–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44).Finlay AC, Hobby GL, P’an SY, Regna PP, Routien JB, Seeley DB, et al. Terramycin, a new antibiotic. Science 1950;111:85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45).Gu W, Gaeta X, Sahakyan A, Chan A, Hong C, Kim R, et al. Glycolytic metabolism plays a functional role in regulating human pluripotent stem cell state. Cell Stem Cell 2016;19:476–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46).Moussaieff A, Rouleau M, Kitsberg D, Cohen M, Levy G, Barasch D, et al. Glycolysis-mediated changes in acetyl-CoA and histone acetylation control the early differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Cell Metab 2015;21:392–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47).Smith KN, Singh AM, Dalton S. Myc represses primitive endoderm differentiation in pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2010;7:343–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48).Cliff TS, Wu T, Boward BR, Yin A, Yin H, Glushka JN, et al. MYC controls human pluripotent stem cell fate decisions through regulation of metabolic flux. Cell Stem Cell 2017;21:502–516.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49).Liu J, Lee P, Galbiati F, Kitsis RN, Lisanti MP. Caveolin-1 expression sensitizes fibroblastic and epithelial cells to apoptotic stimulation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2001;280:C823–C835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50).Razani B, Zhang XL, Bitzer M, von Gersdorff G, Bottinger EP, Lisanti MP. Caveolin-1 regulates transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta/SMAD signaling through an interaction with the TGF-beta type I receptor. J Biol Chem 2001;276:6727–6738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51).Yoon JM, Koppula S, Huh SJ, Hur SJ, Kim CG. Low concentrations of doxycycline attenuates FasL-induced apoptosis in HeLa cells. Biol Res 2015;48:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.