Abstract

Stroke is the fifth leading cause of death in the United States and is a leading cause of disability.1 Extracranial internal carotid artery stenosis is a major cause of ischemic stroke, as it is estimated to cause 8–15% of ischemic strokes.2,3 It is critical to improve our strategies for stroke prevention and treatment in order to reduce the burden of this disease. Here, we review approaches for the diagnosis and risk-stratification of carotid artery disease as well as interventional strategies for the prevention and treatment of strokes caused by carotid artery disease. Several critical questions in the field remain and are active areas of research. First, medical therapy has evolved significantly since early trials comparing medical therapy with interventional therapies, and patient outcomes while on contemporary medical therapy are unknown. Therefore, the benefit of revascularizing severe carotid artery disease in the current era of medical therapy is also unknown. Second, optimal management of patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis continues to be a topic of debate. Third, the role of imaging for further risk-stratification of patients using characteristics of carotid plaques continues to be explored. Fourth, an understanding of how the presence of silent infarcts on brain imaging impacts risk-stratification and selection of treatment strategies is needed. Finally, the optimal use of endovascular management strategies for carotid artery disease, including carotid artery stenting and transcarotid artery revascularization, is an active area of investigation.

Keywords: carotid artery stenosis, stroke, atherosclerosis, carotid endarterectomy, carotid artery stenting

Introduction

Stroke is the fifth leading cause of death in the United States (U.S.) and the second leading cause of death worldwide.1,4 Stroke causes significant disability and reduced quality of life, and is responsible for a large burden of healthcare expenditures. Extracranial carotid artery disease is a leading cause of stroke, causing 8–15% of ischemic strokes.2,3 There are high rates of recurrence for stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA) caused by carotid artery stenosis.5 It is essential that patients with carotid artery disease be treated with optimal medical therapy and appropriate revascularization strategies, when indicated, in order to prevent first-time and repeat strokes.

Carotid artery stenosis is typically diagnosed via four imaging modalities: invasive cerebral angiography, carotid duplex ultrasound (CDUS), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), and computed tomographic angiography (CTA). Though invasive cerebral angiography is the gold-standard for diagnosis, non-invasive imaging techniques are used more commonly to avoid the risk of complications. CDUS is recommended for the initial evaluation of suspected carotid artery stenosis.6 CDUS, MRA, and CTA have high sensitivities and specificities for severe carotid lesions (70–99%) with lower accuracy for moderate stenoses (50–69%).7

To make a sound decision regarding referral for revascularization of patients with moderate-to-severe carotid artery stenosis, a thorough assessment of a patient’s comorbidities and risk-factor profile must be made to ensure that the patient’s risk of future stroke outweighs his or her risk of procedural complications. Based on current guidelines,6,8,9 patients with severe symptomatic stenosis should be referred for carotid endarterectomy (CEA) if the peri-operative risk is less than 6% (Table 1). Patients with moderate symptomatic stenosis have a lower risk of recurrent stroke and, thus, CEA is recommended only if the peri-operative risk is less than 6%, and age, sex, and comorbidities are carefully considered.10 For asymptomatic patients, the benefit of revascularization is more controversial because these patients have a lower risk of stroke which makes it harder to achieve a net benefit of revascularization in this population. In addition, optimal medical therapy has improved significantly since early trials were performed (Table 2), potentially making it less likely to achieve a net benefit of revascularization in asymptomatic patients. In current guidelines, a perioperative risk of stroke or death less than 3% is generally recommended for asymptomatic patients being considered for revascularization (Table 1).8,9,11 Optimal medical therapy is recommended for all patients with carotid artery disease. Revascularization is not recommended for carotid lesions that are fully occluded or are less than 50% stenotic.12

Table 1.

Society Guidelines for performing CEA in patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic carotid stenosis.

| Asymptomatic | Symptomatic | |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS)8 |

|

|

| 2017 European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS)9 |

|

|

| 2005 American Academy of Neurology (ANA)32 |

|

|

| 2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS6 |

|

|

| 2014 American Heart Association (AHA)/American Stroke Association (ASA) |

|

Table 2.

Medical therapies used in early landmark trials compared with modern treatments. Medical therapy for carotid artery stenosis has improved significantly over time. From Lalla, R., Raghavan, P. & Chaturvedi, S. Trends and controversies in carotid artery stenosis treatment. F1000Research 9, (2020).

| Condition | Treatment in first-generation trials | Modern treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Antithrombotic therapy | Aspirin alone | Aspirin plus clopidogrel |

| Lipids | Little statin use | High-potency statins |

| Blood pressure | No specific target | Systolic blood pressure less than 130 mm Hg |

| Smoking cessation | No pharmacologic therapy | New pharmacologic treatments |

| Physical activity | No specific target | Benefits understood for regular physical activity (three or four sessions of aerobic exercise per week) |

| Diabetes | No specific medications for cardiovascular (CV) risk | Pharmacologic treatments that reduce CV risk, hemoglobin A1C target of less than 7 |

| High triglyceride levels | No specific treatment | Icosapent ethyl |

Carotid artery stenting (CAS) and transcarotid artery revascularization (TCAR) are alternative approaches to carotid artery revascularization. More data are required to determine optimal patient selection for CEA, CAS, and TCAR. In addition, further investigation is needed to determine patient outcomes when treated with contemporary medical therapy and whether the clinical impact of this therapy should change thresholds for referral for revascularization. The use of advanced imaging techniques may refine our ability to risk-stratify patients.

Epidemiology and Consequences of Extracranial Carotid Artery Disease

Approximately 795,000 people sustain a stroke each year in the U.S. and 1 out of 19 deaths in the U.S. in 2017 was caused by stroke. By 2030, 3.4 million additional adults over the age of 18 are predicted to have suffered a stroke – a 20.5% increase in prevalence from 2012.1 From 2014–2015 data, the direct medical cost of stroke in the U.S. was estimated to be $28 billion, and the combined direct and indirect cost was estimated to be $45.5 billion.1

Stroke causes significant disability and reduces quality of life. In a survey of patient preferences, a significant proportion of patients rated major stroke as being a worse outcome than death.13 Following a stroke, patients are at risk for short-term complications including seizures, venous thromboembolism, and infection; as well as long-term complications such as pain syndromes, depression, cognitive impairment, dementia, and falls. A meta-analysis reported that approximately one-third of all stroke survivors develop depression within the first year after stroke.14 In 2011, after hospitalization for stroke, 19% of Medicare patients required discharge to inpatient rehabilitation facilities, 25% required discharge to skilled nursing facilities, and 12% required home health care.1

There are significant regional, sex, and racial disparities in stroke prevalence and mortality. The median stroke prevalence in adults in the United States is 3% with the lowest prevalence in Wisconsin and the highest prevalence in Arkansas (1.9% and 4.5%, respectively). Arkansas is part of the “stroke belt,” a group of states with the highest stroke mortality in the U.S. which also includes: North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana.1

Women have a higher lifetime risk of stroke than men.1 The Framingham Heart Study identified a lifetime risk of stroke for women aged 55–75 of 1 in 5 and approximately 1 in 6 for men of the same age.15 Women have lower age-specific incidence rates of stroke than men at younger and middle-ages, but similar or higher rates in older age groups. More women than men die of stroke each year due to a greater life expectancy for women. For example, women accounted for 58% of stroke deaths in 2017 in the U.S.

People who are Black or Hispanic have a higher risk of stroke than White people. The age-adjusted incidence for first ischemic stroke was higher in Black (1.91/1000) and Hispanic individuals (1.49/1000) than in White individuals (0.88/1000). In 2017, non-Hispanic Black individuals had higher age-adjusted death rates from stroke than non-Hispanic (NH) White individuals.1 Mexican Americans were found to have a higher incidence of stroke compared with NH White people (crude 3-year cumulative incidence 16.8/1000 vs. 13.6/1000, respectively).

Extracranial internal carotid artery stenosis is a major cause of ischemic stroke. It is estimated to cause 8–15% of ischemic strokes or approximately 41,000 strokes per year in the U.S.2, 3 In addition, TIA and stroke caused by carotid artery stenosis is associated with a high rate of recurrence of stroke.5 Among those who have sustained an initial stroke, the risk of recurrent stroke is 25% within 5 years.12 In ultrasound studies, the prevalence of moderate-to-severe carotid stenosis in asymptomatic patients is estimated to be 4–8% among adults in the U.S.16,17 The incidence of carotid stenosis increases with age. For example, in one study, severe stenosis (greater than or equal to 70%) in men ranged from 0.1% for men under 50 years of age to 3.1% (1.7–5.3%) in men with age greater than or equal to 80 years of age. Similarly, among women, there was a prevalence of 0% for those less than 50 years of age and 0.9% (0.3–1.4%) for those with age greater than or equal to 80 years.18 Among Black individuals compared with White individuals, the risk ratio (RR) of extracranial atherosclerotic stroke was 3.18 (95% CI, 1.42–7.31) and among Hispanic individuals compared with White individuals, the RR was 1.71 (95% CI, 0.80–3.63).

Pathophysiology

Cerebral ischemia caused by carotid artery stenosis may occur via several mechanisms. First, carotid atherosclerosis may develop leading to a reduction in vessel lumen diameter. Atherosclerosis most frequently occurs in the internal carotid artery (ICA). It is typically most severe at the ostium of the ICA and bifurcation of the common carotid artery and often involves the posterior wall of the artery.19 Second, an atheroma may embolize, resulting in a distal infarct. Third, thrombus can develop on an atheroma, further narrowing the lumen of the vessel. Fourth, this thrombus may break off, leading to artery-to-artery embolic stroke. Fifth, an acute thrombotic occlusion may occur at the site of an atheroma. Sixth, a dissection of the vessel can occur.20

Diagnosis of Carotid Artery Stenosis

There are four primary imaging modalities used to identify carotid artery stenosis including invasive cerebral angiography, CDUS, MRA, and CTA.

Invasive cerebral angiography is the gold standard for evaluating carotid artery stenosis. The use of digital subtraction angiography (DSA) reduces the dose of contrast, allows for use of smaller catheters, and provides a higher quality image of the vasculature. Advantages of this method are that it provides information about several of the head and neck arteries, and evaluates collateral flow, atherosclerotic disease in adjacent arteries, and plaque morphology and severity.21 The primary disadvantage is that it is an invasive procedure with potential for complications. The risk of neurological complications is approximately 1%.22 For this reason, non-invasive testing has essentially replaced cerebral angiography as an initial evaluation of carotid stenosis.

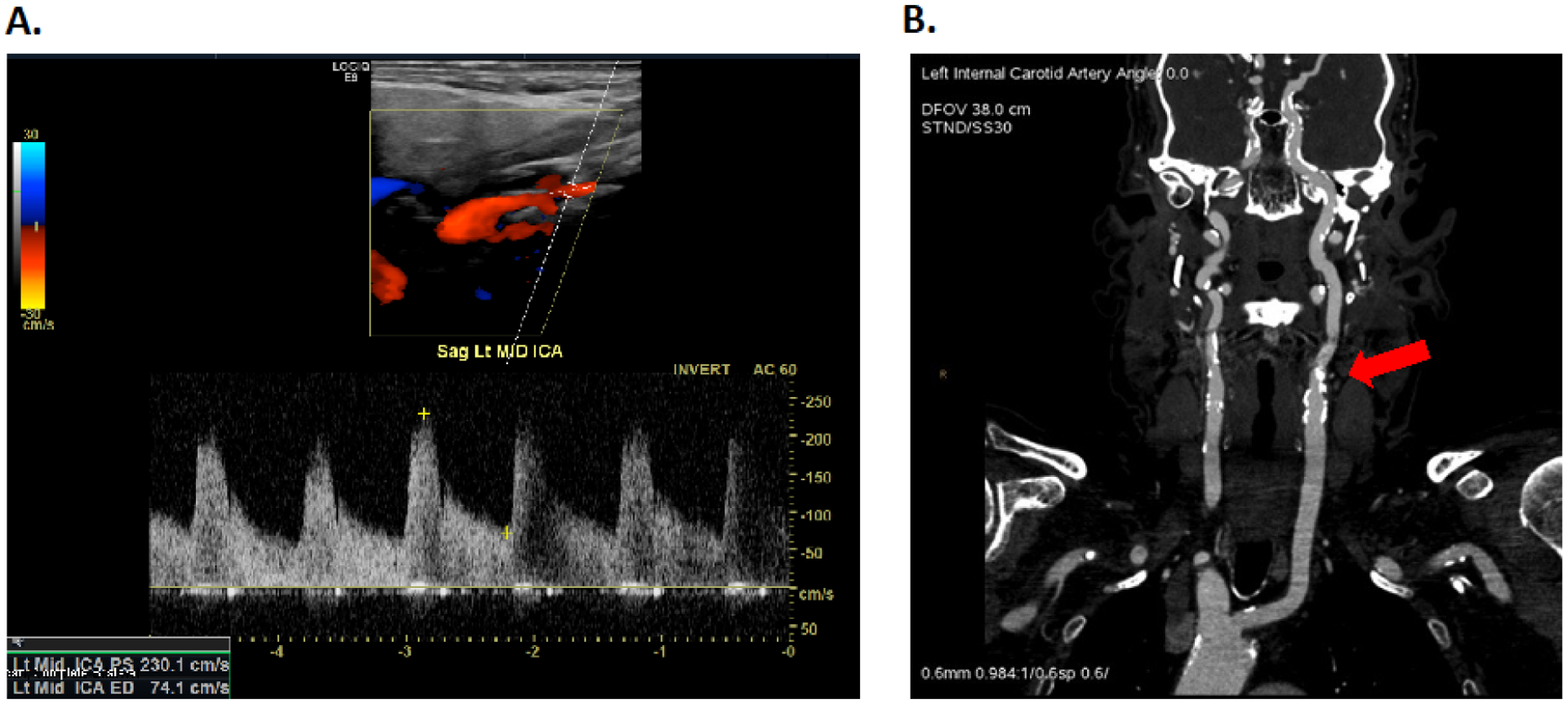

CDUS is recommended for the initial evaluation of a patient suspected to have carotid artery stenosis.6 It is a non-invasive, accurate, and inexpensive method of carotid imaging. CDUS uses grayscale and Doppler ultrasound to measure velocity of blood flow which is translated into severity of stenosis. The peak systolic velocity, end-diastolic velocity, spectral waveform analysis, and the ratio of the peak internal carotid artery to common carotid artery velocity (carotid index) are the standard parameters (Figure 1).23,24,25 More specifically, the landmark North American Symptomatic Carotid Enderterectomy Trial (NASCET) demonstrated the benefit of CEA in patients with severe carotid stenosis (greater than or equal to 70%).12 This study used criteria designed for conventional angiography which have now been extrapolated to CDUS. Based on NASCET criteria for CDUS, a peak systolic velocity of greater than 230 cm/sec or the presence of plaque filling greater than 50% of the diameter of the vessel lumen are the primary criteria used to represent a severely stenotic lesion.24

Figure 1. Carotid duplex ultrasound and computed tomography angiography of severe stenosis in the left internal carotid artery.

A. Carotid duplex ultrasound doppler image of the left internal carotid artery showing a peak systolic velocity of 230.1 cm/sec consistent with severe carotid artery stenosis. B. Computed tomography angiography image of the same lesion revealing approximately 80% stenosis in the left internal carotid artery.

CDUS has the ability to evaluate some important features of plaque morphology such as calcified and non-calcified plaques.21 One meta-analysis reported that CDUS has a sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 84% compared with cerebral angiography for the diagnosis of a 70–99% lesion.7 Importantly, the accuracy of CDUS depends on the experience of the technologist.26 Studies may be limited by calcific lesions, patient body habitus, high carotid bifurcation, vessel tortuosity, or the presence of a carotid stent.27 CDUS may overlook very narrow vessel lumens.21 The presence of a complete contralateral carotid occlusion may cause overestimation of an ipsilateral carotid stenosis due to increased flow through the ipsilateral vessel.28 New developments in CDUS technology such as contrast-enhanced ultrasound allow for a more detailed assessment of plaque morphology, but are not yet used in routine practice.21

MRA and CTA both provide high-resolution images of the carotid arteries. They can better determine severity of stenosis and also provide anatomical detail of the aortic arch, which is helpful when determining treatment strategies. Advantages of MRA are that it can obtain reliable information regarding vessel stenosis in the presence of extensive arterial calcification and it does not expose patients to radiation.21 In addition, time-of-flight (TOF)-MRA can be used in patients who are unable to receive gadolinium. One disadvantage of MRA is it may overestimate the degree of stenosis. Both TOF-MRA and contrast-enhanced MRA are accurate for high-grade stenoses, but may be less accurate for identifying moderate stenoses.29 CTA directly images the arterial lumen and provides an accurate assessment of vessel stenosis (Figure 1). It is particularly helpful for the identifications of complete occlusions. Significant calcification may impact the accuracy of CTA. Additional disadvantages are that iodinated contrast is generally contraindicated in patients with renal dysfunction and patients are exposed to radiation.21

Overall, CDUS, MRA, and CTA all have high sensitivities and specificities for diagnosing carotid lesions in the 70–99% range with lower accuracy for stenoses in the 50–69% range.7

Risk-Stratification of Patients with Carotid Artery Stenosis: who should undergo revascularization?

Risk stratification of patients with carotid artery disease is of critical importance. The primary criteria for risk-stratification include the degree of vessel stenosis, the presence of symptoms attributable to the lesion, and the co-morbid conditions and operative risk of the patient. The approach to some groups, such as those with severe carotid stenosis, symptoms attributable to the lesion, and low surgical risk, is straightforward and supported by evidence, whereas there is ongoing debate about the management of other groups. There are several evolving strategies for risk-stratifying patients: the use of advanced imaging techniques to assess plaque morphology, the use of transcranial Doppler to detect microemboli, and the presence of silent infarcts on brain imaging.

The presence of symptoms attributable to a carotid lesion is a marker of future or recurrent stroke risk. Symptomatic disease is defined as the occurrence of focal neurological deficits in the distribution of a carotid artery with a stenotic lesion. Nonspecific neurological symptoms including dizziness and lightheadedness are excluded from this definition. Of note, several major clinical trials and society guidelines define symptomatic as having experienced symptoms in the last 6 months, but designated patients as asymptomatic if they had no symptoms or had experienced symptoms prior to 6 months.30,31, 32, 6

All patients, regardless of symptom status and risk-factor profile, should be treated with optimal medical therapy which includes anti-platelet therapy, lipid-lowering therapy with an emphasis on high-intensity statins, and anti-hypertensive therapy (Table 2).33,8,6 Revascularization is not recommended for a complete carotid artery occlusion in any patient. Also, revascularization is not recommended for symptomatic or asymptomatic patients with mild stenosis less than 50%.12 The risk-stratification of patients with moderate and severe stenoses is more nuanced and is discussed below.

Management of symptomatic patients is more straightforward than that of asymptomatic patients as there is a clearer correlation between the degree of stenosis and risk of stroke or stroke recurrence. Furthermore, the risk of stroke and stroke recurrence is higher in this population, so the benefits of revascularization are realized more readily. Two large, prospective, multicenter RCTs compared CEA with medical therapy alone and established the benefit of CEA in patients with moderate and severe stenotic lesions. In the NASCET trial, medical therapy alone was compared with CEA with medical therapy in symptomatic patients with different degrees of carotid stenosis.12 All patients were treated with optimal medical therapy and were then randomized to CEA or no CEA. Optimal medical therapy included an anti-platelet agent as well as anti-hypertensive and lipid-lowering agents when indicated. In patients with 50–69% stenosis, CEA reduced the 5-year risk of death or stroke by 29%. Specifically, the 5-year risk of ipsilateral stroke for CEA vs medical therapy alone was 15.7% vs 22.2% (RR 0.71; 95% CI 0.48–0.93; p=0.045), with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 15. The risk of death or stroke at 30 days for CEA vs medical therapy was 33.2% vs 43.3% (RR 0.77; p=0.005) with a NNT of 10. Subgroups that experienced the greatest benefit of CEA included men and those with recent stroke, recent hemispheric symptoms, and those taking aspirin.

In patients with greater than or equal to 70% stenosis, there was an overwhelming benefit of CEA and the trial was stopped early. When patients had been followed for a mean of 18 months, patients who underwent CEA had a significantly lower risk of major stroke or death (8.0 vs. 19.1%) and a lower risk of ipsilateral stroke (9.0 vs. 26.0%). The NASCET trial excluded patients with a life expectancy less than 5 years, disabling stroke, non-atherosclerotic carotid disease, and a history of ipsilateral endarterectomy among other risk factors.

In the European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST), 3,024 patients with symptomatic carotid artery stenosis were treated with optimal medical therapy and randomized to CEA or non-operative management. CEA was found to significantly reduce the rate of major stroke or death compared to optimal medical care alone in the subgroup of patients with greater than or equal to 80% carotid stenosis (14.9% vs. 26.5%; p=0.001) with NNT of 9.31 When ECST measurement criteria were standardized to those used in NASCET, their findings were similar to those reported in NASCET.

Therefore, the current AHA/ASA guidelines recommend CEA for patients with symptomatic carotid artery stenosis in the last 6 months of severity 70–99% if the perioperative risk is less than 6% (Class 1A). CEA is recommended for patients with symptomatic carotid artery stenosis within the last 6 months of severity 50–69% if the perioperative risk is less than 6% and with consideration of patient-specific factors such age, sex, and comorbidities (Class 1B). When the degree of carotid stenosis is less then 50%, CEA and CAS are not recommended (IIIA) (Table 1).10 A better understanding of patient outcomes on modern medical therapy is needed (Table 2).

Patients who have carotid artery stenosis and are asymptomatic have a lower risk of developing stroke over time compared with those who have symptomatic carotid stenosis. Therefore, the threshold to perform revascularization is higher in these patients and there is ongoing debate about the existence of a net benefit of revascularization, particularly in light of significant improvements in medical therapy over time. Unlike patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis, the correlation between degree of stenosis and risk of stroke is less clear for asymptomatic patients.34 Therefore, the risks and benefits must be carefully weighed when making a recommendation for revascularization.

Early trials identified an advantage of revascularization in asymptomatic patients with carotid artery stenosis of 60–99%. In the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (ACAS), a prospective, randomized-control trial (RCT), 1662 patients with asymptomatic stenosis of 60% or greater were randomized to CEA or no CEA and all patients received aspirin 325 mg daily and medical risk factor management. Medical risk factor management consisted of discussions with patients regarding hypertension, diabetes, abnormal lipid levels, excessive alcohol consumption, and tobacco use. At a median follow-up of 2.7 years, the composite endpoint of ipsilateral stroke or any peri-operative stroke or death was 5.1% in the CEA arm and 11.0% in the medical management alone arm (p=0.004).34 The Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST-1) similarly found a significant reduction in 5- and 10-year stroke risk in asymptomatic patients younger than 75 with carotid stenosis greater than or equal to 60%.30 This trial reported a greater absolute risk reduction for men than for women. The ACST trial also demonstrated that the net benefit observed is delayed to approximately 2 years because of the peri-operative risks (myocardial infarction and stroke). Both the ACAS and ACST trials excluded patients deemed to be at high-risk for complications of CEA.

Since these trials were conducted in the 1980s and 1990s, medical therapy has evolved significantly, raising questions about whether a net benefit of revascularization still exists in asymptomatic patients with carotid artery stenosis. For example, the ACAS trial reported an annual stroke risk of 2–2.5% in their study cohort of patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis of 60–99%.34 In a more contemporary study published in 2007, the Second Manifestations of ARTerial disease (SMART) study reported that the risk of annual rate of stroke in asymptomatic patients with moderate to severe disease receiving optimal medical management was 1%.35 The ongoing CREST-2 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02089217), is randomizing patients with severe, asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis to optimal medical therapy alone, CEA, or CAS and will help shed light on the role of revascularization in asymptomatic patients.36

Overall, the management of patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis remains controversial and society recommendations differ (Table 1). The ASA/ACCF/AHA guidelines recommend the following criteria for selection of asymptomatic patients for revascularization: 1) Patient selection should be guided by an assessment of comorbid conditions, life expectancy, and other individual factors and should include a discussion of the risks and benefits of the procedure with an understanding of patient preferences (Class I; Level of Evidence: C). 2) It is reasonable to perform CEA in asymptomatic patients who have greater than 70% stenosis if the risk of perioperative stroke, MI, and death is low (Class IIa; Level of Evidence A). 3) In patients at high risk of complications for carotid revascularization by either CEA or CAS because of comorbidities, the effectiveness of revascularization versus medical therapy alone is not well-established (Class IIb; Level of Evidence: B).6 Given the delay in the realization of the net benefit due to peri-operative adverse events in the ACAS and ASCT trials,37 society guidelines recommend selecting patients with a life expectancy of greater than 3–5 years.9,8 In the ACST trial, there was a 3.1% perioperative complication rate. Thus, the combined peri-operative risk of stroke or death should be less than 3% for the surgeon and center, or risk in asymptomatic patients may exceed the overall benefit. The Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines recommend consideration of surgical intervention for patients with carotid stenosis greater than 60% if life expectancy is greater than 3 years and perioperative risk is less than 3%.8

Although there have not been RCTs performed to evaluate the net benefit of screening, the USPSTF recommends against routine screening for carotid disease in asymptomatic patients.38 The 2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA guidelines recommend consideration of screening in patients with multiple cardiovascular risk factors, a carotid bruit, or those with coronary artery disease (CAD) or peripheral artery disease (PAD).6 In a study of patients with clinical evidence of arterial diseases in vascular territories other than the carotid arteries, investigators found that the prevalence of asymptomatic carotid artery disease greater than 50% was greatest in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) and abdominal aortic aneurysm.39

There are several areas under investigation to improve risk-stratification of patients. First, there is no definitive recommendation for the triage of asymptomatic patients with ipsilateral stroke of unknown age identified on imaging. In one prospective study, 462 patients with asymptomatic stenosis between 60 and 99% were monitored every 6 months for up to eight years. Patients with ipsilateral stroke on their baseline CT scans had a significantly higher risk of subsequent stroke (3.6% rate of annual events versus 1.0%) at a median follow-up of 3.7 years.40

Second, as imaging technology evolves, non-invasive imaging techniques have been developed that can better characterize of plaque morphology. Features of plaque morphology that may indicate plaque vulnerability may be used to better risk-stratify patients. MRI can identify intraplaque hemorrhage, a lipid-rich necrotic core, plaque luminal surface ulceration, and intraplaque neovascularization – features which may be associated with a higher risk of stroke.41 CTA can identify the calcium composition of plaques. Plaques are more stable when at least 45% of their volume is made up of calcium.41 Ultrasound can identify several features thought to increase stroke risk. These include lipid-rich plaques detected based on their echolucency and the presence of calcium which appears as a hyperechoic plaque.41 A newer technique of contrast-enhanced US can identify plaque neovascularization. Transcranial Doppler ultrasound can detect microemboli, which are predictive of ischemic events in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with carotid artery stenosis.42 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET imaging, which can be paired with MRI, can identify plaque inflammation.41 More research is needed to understand the prognostic significant of these modalities and to incorporate them into clinical care.

Determining Modality of Revascularization

Once a patient has been selected to undergo revascularization, there are three primary options: carotid endarterectomy (CEA), carotid artery stenting (CAS), and transcarotid artery revascularization (TCAR). Patient comorbidities, operative risk, life expectancy, presence of symptoms, and anatomic factors should be considered when selecting an interventional strategy.

CAS is an endovascular procedure in which a stent is placed in a carotid artery, most commonly via a transfemoral approach. Several trials have compared outcomes of CAS with CEA, including the Stenting and Angioplasty with Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy (SAPPHIRE) trial and the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stent Trial (CREST). The CREST trial, a multi-center, randomized, unblinded trial, compared CAS to CEA in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients receiving optimal medical therapy.43 2,502 patients were randomized to either CAS or CEA. Results showed that CAS and CEA were similar in terms of the primary outcome of the composite of periprocedural stroke, MI, death, or ipsilateral stroke within 4 years of follow-up (periprocedurally: 0.7% vs. 0.3%; HR 2.25; 95% CI 0.69–7.30, p=0.18) (4-year follow-up: 10.2% vs. 12.6%; HR 1.12; 95% CI 0.83–1.51; p=0.45). In secondary analyses, the investigators found that there were more periprocedural strokes and strokes at 4 years with CAS for the secondary outcome of “any stroke” (periprocedurally: 4.1% vs. 2.3%, p=0.01; 4-years: 10.2% vs. 7.9%, p=0.03), but there was no difference in “major stroke” periprocedurally or at 4 years. There were fewer periprocedural MIs with CAS relative to CEA (1.1% vs. 2.3%, p=0.03), but no difference at 4 years. The subgroup analysis found that older patients (age greater than or equal to 70 years) had better outcomes with CEA.

The SAPPHIRE trial randomized patients at higher risk for CEA to either CEA or CAS with an embolic protection device.44 The primary endpoint was the cumulative incidence of a composite of death, stroke, or MI within 30 days or death or stroke between days 31 and 1 year. They reported that CAS with embolic-protection was not inferior to CEA in symptomatic patients with carotid artery stenosis greater than or equal to 50% or in asymptomatic patients with carotid artery stenosis of greater than or equal to 80% who had comorbid conditions that increased the risk of carotid endarterectomy.

Bonati et al. performed a meta-analysis of 16 trials (7572 patients) comparing outcomes for endovascular therapy, comprised primarily of CAS procedures, with CEA for the management of carotid artery stenosis.45 They found that endovascular treatment was associated with an increased risk of 30-day peri-procedural stroke or death compared with endarterectomy; however, in subgroup analyses, they found that this increase was only significant for patients with age greater than or equal to 70 and there was no difference in periprocedural stroke or death for patients with age less than 70. Overall, patient comorbidities, anatomic features, and age must be considered when determining whether a patient should undergo CEA or CAS (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patient characteristics to consider when referring patients for carotid revascularization via CEA or CAS. From Meschia, J. F., Klaas, J. P., Brown, R. D. & Brott, T. G. Evaluation and Management of Atherosclerotic Carotid Stenosis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 92, 1144–1157 (2017).

| Factor | Favors |

|---|---|

| Age >70 years | CEA |

| Recently symptomatic patient (<2 weeks) | CEA |

| Tortuous and/or heavily calcified vessels | CEA |

| Contralateral carotid occlusion | CAS |

| Restenosis after prior CEA | CAS |

| Previous neck surgery and/or radiation | CAS |

| Laryngeal nerve palsy | CAS |

| Periprocedural risk of: | |

| Myocardial infarction | CAS |

| Cranial nerve injury | CAS |

| Stroke | CEA |

| Death | CEA |

| Long-term risk of: | |

| Myocardial infarction | No difference |

| Stroke | No difference |

| Death | No difference |

TCAR is a recently developed technique for carotid artery stent placement. Access is obtained via an incision over the common carotid artery. Flow reversal is achieved which provides embolic protection. TCAR avoids potential pitfalls associated with CAS including severe PAD, challenging anatomy of the aortic arch, and a heavily calcified aorta. In a retrospective, observational study, 1182 TCAR patients were propensity matched with 10,797 CEA patients and outcomes were compared. There was no difference between TCAR and CEA in adjusted analyses of in-hospital outcomes including the combination of stroke/death/MI, stroke/death, or the individual outcomes.46

Conclusion

The management and prevention of strokes caused by carotid artery disease is distinct from other causes of stroke as there is a wide range of procedural interventions available to prevent first-time stroke and stroke recurrence. In all patients, optimal medical management is of paramount importance. Patients with carotid artery stenosis must undergo a thorough assessment of life expectancy, procedural risk, comorbidities, and anatomic features in order to be triaged to the appropriate modality of revascularization versus optimal medical therapy alone. When revascularization is considered, further considerations are needed to determine the best revascularization strategy: CEA, CAS, or TCAR. More research is needed to understand patient outcomes on contemporary medical therapy and the optimal risk-stratification of asymptomatic patients. The use of advanced imaging techniques may be able to further refine risk-stratification of these patients in the future.

Clinical Care Points.

Stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA) caused by carotid stenosis are associated with a high rate of recurrence of stroke.

Carotid duplex ultrasound is recommended for the initial evaluation of a patient suspected to have carotid artery stenosis.

All patients with carotid artery disease should be treated with optimal medical therapy.

Revascularization is not recommended for a complete carotid occlusion or for patients with less than 50% stenosis.

Patients with symptomatic stenosis of 70–99% should be referred for carotid endarterectomy if the peri-operative risk is less than 6%.

Patients with symptomatic stenosis of 50–69% have a lower risk of recurrent stroke and thus CEA is recommended for most patients if the peri-operative risk is less than 6% and age, sex, and comorbidities are carefully considered.

CEA should be considered for asymptomatic patients with carotid artery stenosis of 60–99% with a life expectancy greater than 3–5 years with peri-operative risk of stroke and death less than 3%.

When referring a patient for CEA versus carotid artery stenting or transcarotid artery revascularization, age, symptom status, and a variety of patient characteristics should be considered in order to triage patients to the most appropriate procedure.

CAS may be considered for symptomatic patients with 50–99% stenosis with perioperative risk of less than 6% who have been deemed high risk for CEA.

CAS may be considered for asymptomatic patients with 60–99% stenosis with perioperative risk of less than 3% and a life expectancy >5 years who have been deemed high risk for CEA and who have clinical or imaging characteristics associated with an increased risk of stroke.

Funding:

Dr. Secemsky is supported by NIH/NHLBI K23HL150290 and Harvard Medical School’s Shore Faculty Development Award.

Relationships with Industry:

ES: Consulting/Scientific Advisory Board: Abbott, Bayer, BD, Boston Scientific, Cook, CSI, Inari, Janssen, Medtronic, Philips, and Venture Medical.; Research Grants: AstraZeneca, BD, Boston Scientific, Cook, CSI, Laminate Medical, Medtronic, and Philips.

Abbreviations:

- ACAS

Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study

- ACST-1

Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial

- CAS

Carotid artery stenting

- CDUS

Carotid duplex ultrasound

- CEA

Carotid endarterectomy

- CTA

Computed tomographic angiography

- ECST

European Carotid Surgery Trial

- ICA

Internal carotid artery

- MRA

Magnetic resonance angiography

- NASCET

North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial

- NNT

Number needed to treat

- PAD

Peripheral artery disease

- SMART

Second Manifestations of ARTerial disease study

- TCAR

Transcarotid artery revascularization

- U.S

United States

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All other authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Virani SS et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 141, (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flaherty ML et al. Carotid artery stenosis as a cause of stroke. Neuroepidemiology 40, 36–41 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajat C et al. Incidence of aetiological subtypes of stroke in a multi-ethnic population based study: the South London Stroke Register. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 82, 527–533 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feigin VL et al. Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet Lond. Engl 383, 245–254 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marnane M et al. Stroke recurrence within the time window recommended for carotid endarterectomy. Neurology 77, 738–743 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brott Thomas G et al. 2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS Guideline on the Management of Patients With Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease: Executive Summary. Circulation 124, 489–532 (2011).21282505 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wardlaw JM et al. Non-invasive imaging compared with intra-arterial angiography in the diagnosis of symptomatic carotid stenosis: a meta-analysis. Lancet Lond. Engl 367, 1503–1512 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ricotta JJ et al. Updated Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines for management of extracranial carotid disease. J. Vasc. Surg 54, e1–31 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aboyans V et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): Document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteriesEndorsed by: the European Stroke Organization (ESO)The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur. Heart J 39, 763–816 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kernan WN et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 45, 2160–2236 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giannopoulos A et al. Mortality risk stratification in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Vasc. Investig. Ther 2, 25 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnett HJ et al. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N. Engl. J. Med 339, 1415–1425 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samsa GP et al. Utilities for major stroke: results from a survey of preferences among persons at increased risk for stroke. Am. Heart J 136, 703–713 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hackett ML & Pickles K Part I: frequency of depression after stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Stroke Off. J. Int. Stroke Soc 9, 1017–1025 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seshadri S et al. The lifetime risk of stroke: estimates from the Framingham Study. Stroke 37, 345–350 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suri MFK, Ezzeddine MA, Lakshminarayan K, Divani AA & Qureshi AI Validation of two different grading schemes to identify patients with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis in general population. J. Neuroimaging Off. J. Am. Soc. Neuroimaging 18, 142–147 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fine-Edelstein JS et al. Precursors of extracranial carotid atherosclerosis in the Framingham Study. Neurology 44, 1046–1050 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Weerd M et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis in the general population: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Stroke 41, 1294–1297 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad K Pathophysiology and Medical Treatment of Carotid Artery Stenosis. Int. J. Angiol. Off. Publ. Int. Coll. Angiol. Inc 24, 158–172 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez NR, Liebeskind DS, Dusick JR, Mayor F & Saver J Intracranial arterial stenoses: current viewpoints, novel approaches, and surgical perspectives. Neurosurg. Rev 36, 175–185 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adla T & Adlova R Multimodality Imaging of Carotid Stenosis. Int. J. Angiol. Off. Publ. Int. Coll. Angiol. Inc 24, 179–184 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heiserman JE et al. Neurologic complications of cerebral angiography. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol 15, 1401–1407; discussion 1408–1411 (1994). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carroll BA Carotid sonography. Radiology 178, 303–313 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grant EG et al. Carotid artery stenosis: gray-scale and Doppler US diagnosis--Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference. Radiology 229, 340–346 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huston J et al. Redefined duplex ultrasonographic criteria for diagnosis of carotid artery stenosis. Mayo Clin. Proc 75, 1133–1140 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Criswell BK, Langsfeld M, Tullis MJ & Marek J Evaluating institutional variability of duplex scanning in the detection of carotid artery stenosis. Am. J. Surg 176, 591–597 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ooi YC & Gonzalez NR Management of Extracranial Carotid Artery Disease. Cardiol. Clin 33, 1–35 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujitani RM, Mills JL, Wang LM & Taylor SM The effect of unilateral internal carotid arterial occlusion upon contralateral duplex study: criteria for accurate interpretation. J. Vasc. Surg 16, 459–467; discussion 467–468 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Debrey SM et al. Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance angiography for internal carotid artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 39, 2237–2248 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halliday A et al. 10-year stroke prevention after successful carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic stenosis (ACST-1): a multicentre randomised trial. The Lancet 376, 1074–1084 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST). Lancet Lond. Engl 351, 1379–1387 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaturvedi S et al. Carotid endarterectomy--an evidence-based review: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 65, 794–801 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aday AW & Beckman JA Medical Management of Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis 59, 585–590 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. JAMA 273, 1421–1428 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goessens Bertine MB, Visseren Frank LJ, Kappelle L. Jaap, Algra Ale, & van der Graaf Yolanda. Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis and the Risk of New Vascular Events in Patients With Manifest Arterial Disease. Stroke 38, 1470–1475 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04496544.

- 37.Halliday A et al. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond. Engl 363, 1491–1502 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LeFevre ML & Preventive US Services Task Force. Screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann. Intern. Med 161, 356–362 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goessens BMB et al. Screening for asymptomatic cardiovascular disease with noninvasive imaging in patients at high-risk and low-risk according to the European Guidelines on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: the SMART study. J. Vasc. Surg 43, 525–532 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kakkos SK et al. Silent embolic infarcts on computed tomography brain scans and risk of ipsilateral hemispheric events in patients with asymptomatic internal carotid artery stenosis. J. Vasc. Surg 49, 902–909 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lalla R, Raghavan P & Chaturvedi S Trends and controversies in carotid artery stenosis treatment. F1000Research 9, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Purkayastha S & Sorond F Transcranial Doppler Ultrasound: Technique and Application. Semin. Neurol 32, 411–420 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brott TG et al. Stenting versus Endarterectomy for Treatment of Carotid-Artery Stenosis. N. Engl. J. Med 363, 11–23 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yadav JS et al. Protected carotid-artery stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients. N. Engl. J. Med 351, 1493–1501 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bonati LH, Lyrer P, Ederle J, Featherstone R & Brown MM Percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty and stenting for carotid artery stenosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev CD000515 (2012) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000515.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schermerhorn ML et al. In-hospital outcomes of transcarotid artery revascularization and carotid endarterectomy in the Society for Vascular Surgery Vascular Quality Initiative. J. Vasc. Surg 71, 87–95 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meschia JF, Klaas JP, Brown RD & Brott TG Evaluation and Management of Atherosclerotic Carotid Stenosis. Mayo Clin. Proc 92, 1144–1157 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]