Abstract

Malaria cases have dramatically declined in China along the Myanmar border, attributed mainly to adoption of the 1-3-7 surveillance and response approach. No indigenous cases have been reported in China since 2017. Counties in the middle and southern part of the border area have a higher risk for malaria importation and reestablishment after elimination.

Keywords: malaria, vector-borne infections, China, Myanmar

In 2010, China issued the National Malaria Elimination Action Plan (2010–2020), with the goal of eliminating malaria nationwide by 2020 (1). Malaria cases in China subsequently decreased dramatically, and no indigenous cases have been reported since 2017 (2). In 2020, on the basis of successful subnational verification, China submitted an official request to the World Health Organization for certification of national malaria elimination, which requires a country to provide evidence that local malaria transmission has been fully interrupted, that zero indigenous human malaria cases have been reported for >3 consecutive years, and that an adequate program for preventing reestablishment of indigenous transmission is fully functional throughout the country (3). However, the China–Myanmar border of Yunnan Province has attracted considerable attention because of a substantial risk of reintroduction of malaria from bordering areas of Myanmar (4). This border region is extremely remote, has high rates of poverty, and is inhabited by local minority nationalities (5,6). A total of 18 counties in Yunnan Province share the 1,997-km border with the townships of Myanmar in which malaria is endemic; the border provides no natural barriers and poses a high risk for malaria reintroduction into China.

The Study

We extracted data on reported malaria cases and foci during 2013–2019 from the web-based China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention and comprised data from passive case detection, reactive case detection among foci residents and case co-travelers, and proactive case detection among at-risk populations. Indigenous cases were defined as cases in patients who contracted malaria by bites from Anopheles mosquitoes within China without direct link to transmission from an imported case, whereas imported cases were defined as cases in patients who had exposure history in any malaria-endemic areas abroad before the onset of illness (7,8). Plasmodium spp. were determined by microscopy or rapid diagnosis test and PCR (8). This study was an epidemiologic analysis of malaria along the China–Myanmar border to identify the risk for malaria reestablishment in the stage after elimination.

During 2013–2019, a total of 2,222 malaria cases were reported from the 18 border counties; 1 death occurred. Total cases fell from 465 in 2013 to 148 in 2019; indigenous cases dropped to zero by 2017, and the number of imported cases also declined (Table 1). This decrease was mainly attributed to the extensive adoption of the 1-3-7 approach to surveillance and response: case reporting within 1 day, investigation within 3 days, and focus investigation and response within 7 days. Case-patients ranged in age from 19 to 59 years, and men and outdoor workers were at considerably higher risk of contracting malaria (p<0.0001) (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of reported malaria cases in the 18 counties in China along the border with Myanmar, 2013–2019*.

| Characteristics |

No. cases by year |

|

No. cases by type |

Total cases |

p value† |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

Imported |

Indigenous |

||||

| Total cases |

465 |

392 |

478 |

312 |

263 |

164 |

148 |

|

2,130 |

92 |

|

|

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| M | 392 | 349 | 404 | 231 | 179 | 124 | 109 | 1,726 | 62 | 1,788 | 0.0012 | |

| F |

73 |

43 |

74 |

81 |

84 |

40 |

39 |

|

404 |

30 |

434 |

|

| Age group, y | ||||||||||||

| <5 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 41 | 5 | 46 | ||

| 5–18 | 42 | 20 | 36 | 35 | 37 | 19 | 7 | 176 | 20 | 196 | <0.0001 | |

| 19–59 | 415 | 357 | 423 | 253 | 202 | 127 | 132 | 1,850 | 59 | 1,909 | ||

|

>60 |

5 |

6 |

10 |

15 |

14 |

13 |

8 |

|

63 |

8 |

71 |

|

| Occupation‡ | ||||||||||||

| Outdoor worker | 371 | 323 | 323 | 235 | 160 | 95 | 85 | 1,536 | 56 | 1,592 | ||

| Indoor worker | 37 | 28 | 81 | 10 | 13 | 15 | 21 | 204 | 1 | 205 | <0.0001 | |

| Unclear | 50 | 35 | 51 | 56 | 84 | 53 | 42 | 348 | 23 | 371 | ||

| Missing |

7 |

6 |

23 |

11 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

|

42 |

12 |

54 |

|

| Plasmodium spp. | ||||||||||||

| P. vivax | 379 | 330 | 428 | 291 | 253 | 151 | 146 | 1,900 | 78 | 1,978 | ||

| P. falciparum | 80 | 60 | 48 | 21 | 10 | 9 | 2 | 217 | 13 | 230 | ||

| P. malariae | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0.4653 | |

| P. falciparum + P. vivax | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 7 | ||

|

P. falciparum + P. ovale

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

|

3 |

0 |

3 |

|

| Destination of oversea travel and species | ||||||||||||

| Myanmar | 2,056 | |||||||||||

| P. falciparum | 71 | 55 | 46 | 16 | 9 | 6 | 1 | 204 | NA | |||

| P. vivax | 321 | 294 | 399 | 283 | 246 | 150 | 146 | 1,839 | NA | |||

| Other species | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 13 | NA | |||

| Other countries | 74 | |||||||||||

| P. falciparum | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 13 | NA | |||

| P. vivax | 19 | 8 | 19 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 61 | NA | |||

*NA, not available. †The number of cases over years were compared by using a χ2 or Fisher exact test according to sample size (>5 or <5) by SAS software. ‡Outdoor workers are persons whose activity is mostly conducted outside, including architectural engineers, construction workers, farmers, fishermen, overseas migrant workers (expatriate Chinese nationals), open mine workers, sailors or truck drivers, field engineers, herdsmen, military or soldiers, etc. Indoor workers include businessmen, caterers, interpreters, medical staff, office workers, teachers, actors, flight attendants, babysitters, middlemen, cooks, diplomats, financial staff, journalists, underground mine workers, prisoners (although not a worker per se, prisoners were officially classified as an indoor worker since their time is spent indoors), researchers, waiters, etc. Unclear indicates those for whom risk exposure cannot clearly be estimated, including children, retirees, self-employed persons, students, unemployed persons, athletes, tourists, etc. Missing data were not included in the statistical analysis.

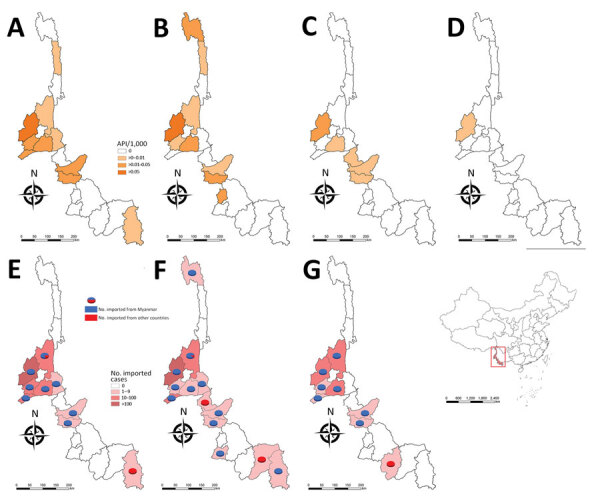

In 2013, malaria cases reported from the 18 border counties accounted for 80.6% of total cases in Yunnan Province; 89.9% (418/465) were imported cases. Indigenous cases (10.1%, 47/465) were distributed in 10 border counties (Figure 1). Yingjiang County reported 38.3% (18/47) of total indigenous cases, along with the highest annual parasite index of 0.058. Five counties displayed an annual parasite index range of 0.01–0.05 (Figure 1). The number of counties reporting indigenous cases decreased from 10 in 2013 to 1 in 2016 (Figure 1). The last indigenous P. falciparum case in China was in Cangyuan County in 2015 and the last indigenous P. vivax case in Yingjiang County in 2016. Most imported malaria cases were distributed in the middle part of the borderline, especially Yingjiang and Tengchong Counties (Figure 1); 96.5% (2,056/2,130) of total imported cases in the 18 border counties were from Myanmar (Table 1). During 2017–2019, a total of 97.7% (562/575) of imported cases and 98.5% (542/550) of P. vivax cases were from Myanmar (Table 1). The counties bordering areas of Myanmar, where rates of malaria were highest, displayed higher numbers of imported cases (9).

Figure 1.

API per 1,000 persons and numbers of imported cases by year in the 18 China counties along the border with Myanmar, 2013–2019. A) 2013 API, B) 2014 API, C) 2015 API, D) 2016 API; E) 2017 imported cases, F) 2018 imported cases, G) 2019 imported cases. Inset map shows location of China–Myanmar border area (rectangle). API, annual parasite index.

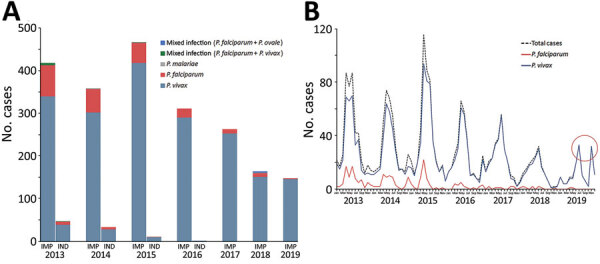

P. vivax was the predominant species. P. vivax cases accounted for 95.7% of total reported cases during 2017–2019, whereas the proportion of P. falciparum declined to 1.4% (Figure 2, panel A). Four cases of P. malariae and 10 cases of mixed infections were reported; no P. ovale cases were reported. A total of 43 relapsing cases (P. vivax cases that recurred 1 month later with neither evidence of an epidemiologic link to additional cases nor as a result of incomplete clearance of original asexual parasites) were reported during 2013–2019, which indicates the need for adherence to the full primaquine regimen and possible resistance to the drug for eliminating the hypnozoites.

Figure 2.

Malaria cases in the 18 counties in China along the border with Myanmar, 2013–2019. A) Proportions of Plasmodium species cases. B) Monthly reported malaria cases. Red circle highlights the double peaks identified in July and November 2019. IMP, imported; IND, indigenous.

The malaria transmission peak was from April to August; another slight peak occurred from December to the following January (Figure 2, panel B). This transmission coincided with the local natural environment and was strongly correlated with the abundance of Anopheles spp. mosquitoes. Of note, double peaks were identified in July and November 2019. The first peak was postponed, whereas the second peak shifted 1 month earlier. This change was primarily caused by migration in the local population. The temporal distribution pattern of P. vivax and P. falciparum was different (Figure 2, panel B) because P. falciparum cases were few and most were imported, mainly because of population movement and migration.

The median interval between onset of illness and diagnosis of malaria varied widely (range 2–10 days; Table 2), because the capability for diagnosis in some healthcare facilities was relatively low; training is needed to strengthen case detection and diagnosis capabilities. In addition, this range reflects the knowledge, attitudes, and practice gaps regarding malaria treatment-seeking of residents. The median interval between diagnosis and treatment was 0 days, except for in Ximeng County, which had a median interval of 0.5 days (Table 2). These rates indicate the capacity of hospital response was strong. The 1-3-7 approach was adopted nationally in China in early 2012 (10). During 2013–2019, all malaria cases were reported within 1 day, 95.6% of cases were investigated within 3 days, and in 8 of 18 counties 100% of cases were investigated within 3 days in all years studied. Longchuan, Gengma, and Yingjiang Centers for Disease Control and Prevention took >3 days to complete investigation of cases from remote areas. Malaria focus in China is defined as the circumscribed village or community with a reported case (11). During 2013–2019, a total of 97.9% (381/389) of foci were investigated and responded to within 7 days in 10 counties (Table 2). Depending on the nature of the focus and its state of transmission, the corresponding response actions were selected; these actions consisted of indoor residual spraying, reactive case detection, case treatment, and health education (7). No secondary cases have been reported because of the prompt and targeted interventions in all the foci.

Table 2. Characteristics of implementation of the 1-3-7 approach to malaria surveillance and response in 18 counties in China along the border with Myanmar, 2013–2019*.

| County |

No. reported cases |

Days from illness onset to diagnosis, median (IQR) |

Days from diagnosis to treatment, median (IQR) |

Case reported within 1 d, % |

Case investigated within 3 d, % |

Foci response within 7 d, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhenkang | 6 | 4.5 (4–7.3) | 0.0 (0–0.75) | 100.0 | 100.0 | – |

| Menghai | 3 | 10.0 (6–12) | 0.0 (0–0.5) | 100.0 | 100.0 | – |

| Lancang | 9 | 7.0 (3–11) | 0.0 (0) | 100.0 | 100.0 | – |

| Jinghong | 14 | 5.0 (3–6) | 0.0 (0) | 100.0 | 92.9 | – |

| Gengma | 29 | 3.0 (1–6) | 0.0 (0–1) | 100.0 | 82.8 | 100.0 (4/4) |

| Mengla | 30 | 2.0 (1–5) | 0.0 (0–1) | 100.0 | 93.3 | 100.0 (1/1) |

| Menglian | 20 | 3.5 (0–7.5) | 0.0 (0–2.25) | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 (1/1) |

| Lushui | 18 | 6.5 (3–10) | 0.0 (0) | 100.0 | 100.0 | – |

| Ximeng | 4 | 4.5 (3.8–6) | 0.5 (0–1) | 100.0 | 100.0 | – |

| Fugong | 11 | 4.0 (3–6.5) | 0.0 (0) | 100.0 | 100.0 | – |

| Cangyuan | 35 | 4.0 (2–7.5) | 0.0 (0) | 100.0 | 97.1 | – |

| Longchuan | 69 | 2.0 (1–4) | 0.0 (0–1) | 100.0 | 82.6 | 100.0 (20/20) |

| Longling | 75 | 3.0 (2–5) | 0.0 (0) | 100.0 | 98.7 | 85.7 (6/7) |

| Gongshan | 5 | 4.0 (1–5) | 0.0 (0–5) | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 (1/1) |

| Mangshi | 112 | 3.0 (1–4) | 0.0 (0–2) | 100.0 | 92.0 | 96.2 (25/26) |

| Tengchong | 525 | 2.0 (1–4) | 0.0 (0–2) | 100.0 | 95.6 | 98.0 (48/49) |

| Yingjiang | 895 | 2.0 (1–4) | 0.0 (0) | 100.0 | 88.4 | 98.5 (256/261) |

| Ruili | 362 | 2.5 (1–5) | 0.0 (0) | 100.0 | 97.2 | 100.0 (19/19) |

*IQR, interquartile range, –, no focus reported.

Conclusions

China has set a goal to eliminate malaria by 2020, and Myanmar has set a goal to eliminate malaria by 2030 (1,12). This study demonstrated that local malaria transmission has been interrupted in Yunnan Province at the China–Myanmar border, although the risk for malaria reintroduction still exists. The complex geographic conditions and large migrant population along the border, in addition to reservoirs of symptomatic and asymptomatic infection in neighboring Myanmar (13), are obstacles to consolidating achievements in malaria elimination (5,14). Another noteworthy factor is the coronavirus disease pandemic. Maintaining full engagement with malaria control is challenging given the simultaneous demands of the pandemic (15).

In summary, malaria elimination has been achieved in the counties in China along the border with Myanmar. However, continued strong surveillance, multisectoral collaboration, and cross-border cooperation are of high priority to reduce the risk for malaria reintroduction and sustain its elimination.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Malaria Elimination Program of China and the Fifth Round of Three-Year Public Health Action Plan of Shanghai (No. GWV-10.1-XK13).

The datasets used and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Biography

Dr. Huang is a molecular epidemiologist in the National Institute of Parasitic Diseases, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Her primary research interests are malaria epidemiology and antimalarial drug resistance.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Huang F, Zhang L, Tu H, Cui Y-W, Zhou S-S, Xia Z-G, et al. Epidemiologic analysis of efforts to achieve and sustain malaria elimination along the China–Myanmar border. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021 Nov [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2711.204428

References

- 1.The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. China malaria elimination action plan (2010–2020), 19 May 2010 [in Chinese]. 2010. [cited 2021 Apr 15]. http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2010-05/26/content_1614176.htm

- 2.Feng J, Zhang L, Huang F, Yin JH, Tu H, Xia ZG, et al. Ready for malaria elimination: zero indigenous case reported in the People’s Republic of China. Malar J. 2018;17:315. 10.1186/s12936-018-2444-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Preparing for certification of malaria elimination, 4 January 2021. [cited 2021 Apr 15]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240005624

- 4.Yang WZ, Zhou XN. New challenges of malaria elimination in China [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2016;50:289–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Dong JQ, Li JY, Zhang Y, Tian YH, Sun XY, et al. Effectiveness and impact of the cross-border healthcare model as implemented by non-governmental organizations: case study of the malaria control programs by health poverty action on the China-Myanmar border. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5:80. 10.1186/s40249-016-0175-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng J, Liu J, Feng X, Zhang L, Xiao H, Xia Z. Towards malaria elimination: monitoring and evaluation of the “1-3-7” approach at the China-Myanmar border. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95:806–10. 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Technical scheme of malaria elimination in China, 2 September 2011. [in Chinese] [cited 2021 Apr 15]. https://www.chinacdc.cn/did/crbzt/jscb/nj/njzyzl/lgjbfk/lgfkfa/201507/P020150715347374233381.pdf

- 8.National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Diagnostic criteria for malaria (WS 259–2015) [in Chinese]. 2015. Nov 16 [cited 2021 Apr 15]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/fzs/s7852d/201511/5a35d124469a4b69884c942c43ae3269.shtml

- 9.Huang F, Zhang L, Xue JB, Zhou HN, Thi A, Zhang J, et al. From control to elimination: a spatial-temporal analysis of malaria along the China-Myanmar border. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9:158. 10.1186/s40249-020-00777-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou SS, Zhang SS, Zhang L, Rietveld AE, Ramsay AR, Zachariah R, et al. China’s 1-3-7 surveillance and response strategy for malaria elimination: Is case reporting, investigation and foci response happening according to plan? Infect Dis Poverty. 2015;4:55. 10.1186/s40249-015-0089-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng J, Tu H, Zhang L, Zhang S, Jiang S, Xia Z, et al. Mapping transmission foci to eliminate malaria in the People’s Republic of China, 2010-2015: a retrospective analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:115. 10.1186/s12879-018-3018-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Malaria Control Program Myanmar. National plan for malaria elimination in Myanmar 2016–2030. 2017. [cited 2020 Apr 5]. https://apmen.org/sites/default/files/all_resources/National%20Strategic%20Plan_Myanmar_2016-2020.pdf.

- 13.Chen I, Clarke SE, Gosling R, Hamainza B, Killeen G, Magill A, et al. “Asymptomatic” malaria: a chronic and debilitating infection that should be treated. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1001942. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu X, Zhou G, Wang Y, Hu Y, Ruan Y, Fan Q, et al. Microgeographic heterogeneity of border malaria during elimination phase, Yunnan Province, China, 2011–2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1363–70. 10.3201/eid2208.150390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiodini J. COVID-19 and the impact on malaria. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;35:101758. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]