Abstract

Cordyheptapeptide A is a lipophilic cyclic peptide from the prized Cordyceps fungal genus that shows potent cytotoxicity in multiple cancer cell lines. To better understand the bioactivity and physicochemical properties of cordyheptapeptide A with the ultimate goal of identifying its cellular target, we developed a solid phase synthesis of this multiply N-methylated cyclic heptapeptide which enabled rapid access to both side chain- and backbone-modified derivatives. Removal of one of the backbone amide N-methyl (N-Me) groups maintained bioactivity, while membrane permeability was also preserved due to the formation of a new intramolecular hydrogen bond in low dielectric solvent. Based on its cytotoxicity profile in the NCI-60 cell line panel, as well as its phenotype in a microscopy-based cytological assay, we hypothesized that cordyheptapeptide was acting on cells as a protein synthesis inhibitor. Further studies revealed the molecular target of cordyheptapeptide A to be the eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1A (eEF1A), a target shared by other lipophilic cyclic peptide natural products. This work offers a strategy to study and improve cyclic peptide natural products while highlighting the ability of these lipophilic compounds to effectively inhibit intracellular disease targets.

Introduction:

Macrocycles have long been pursued for their rich structural diversity and continue to provide a bountiful source of bioactive scaffolds.1-3 Significant work has gone into understanding and improving both the biochemical and physiochemical properties of macrocycles with a recent emphasis on their uses as therapeutics.4, 5 Many cyclic peptide natural products are highly active in mammalian cells, prompting studies by our group and others into the factors that govern cell permeability in these large, non-“drug-like” molecules.6-9 In the course of our investigations into the relationship between molecular size and cell permeability,7, 8 we synthesized and investigated the properties of cordyheptapeptide A (1) (Figure 1). Originally isolated from Cordyceps, a fungal genus widely valued for its pharmaceutical potential,10 the cordyheptapeptide family, including cordyheptapeptide B (2) and C, are reported to show toxicity toward bacteria, fungi, as well as a variety of cancer cell lines.11-13 While a crystal structure11 of 1 and its solution-phase total synthesis have been reported,13 its biological target(s) and mechanism of action have remained unknown.

Figure 1.

Compound structures a) chemical structure of cordyheptapeptide A (1). b) Effect of 1 on cell proliferation in HCT 116 cells after 72 h. Error bars are one SD. N =3

During an image-based screening effort on a variety of natural and synthetic cyclic peptides, we identified an interesting and potent phenotypic activity of 1 in HeLa cells. This observation prompted us to develop an efficient solid-phase synthesis approach to 1 and several derivatives, enabling the investigation of structure-activity and structure-permeability relationships in the cordyheptapeptide family. Here we demonstrate, using NMR coupled with molecular dynamics simulations, that small modifications to the backbone can drastically affect both the permeability and bioactivity of this cyclic peptide. Additionally, by combining two high-content screening assays, we have identified the cellular target of cordyheptapeptide A as the translation elongation factor eEF1A.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION:

Improved total synthesis

The solution-phase total synthesis of cordyheptapeptide A (1, Figure 1A) has been reported previously.13 We developed a total synthesis for 1 using solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS), allowing for rapid, automated linear synthesis using Fmoc chemistry, N-methylated amino acid monomers, and in-sequence, on-resin N-methylation14 (Supplementary Scheme 1). This higher-throughput synthesis was essential for generating a library of compounds to investigate structure-activity and structure-permeability relationships.

Bioactivity optimization

Since its isolation in 2006, 1 and its derivatives have shown cytotoxicity in a variety of cancer cell lines, with IC50 values in the mid- to low-μM range.11 We confirmed literature results for 1 in HCT 116 cells (IC50 = 0.2 μM, Figure 1B, Supplementary Figure 1). The reported IC50 of cordyheptapeptide B (2, NMeTyr6NMePhe) is similar to 1, but is often less potent.11-13 Our cell proliferation results also showed 2 to be less active than 1 (IC50 = 1.1 μM, Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of potency and properties between cordyheptapeptides A and B and synthetic derivatives. The compounds are compared by ALogP, IC50, PAMPA permeability, and aqueous solubility. The features are colored on a log scale ranging from white (weakest potency, poorest permeability/solubility) to dark (highest potency, best permeability/solubility). The IC50 of a compound was determined by 72-h cell proliferation in HCT 116 cells. (See Supplementary Table 1 for IC50 95% confidence intervals)

| Compound | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ALogP IC50 (μM) | Pe x 10−6 (cm/s) |

Solubility (μM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe | MeTyr | Ile | 4.2 | 0.2 | 1.2* | 4 | |

| 2 | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe | MePhe | Ile | 4.5 | 1.1 | 2.3* | 2 | |

| Alanine Scan | VK03 (3) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe | MeTyr | Ala | 2.9 | >75 | 0.2* | 10 |

| VK04 (4) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe | MeAla | Ile | 2.9 | >75 | 5.9* | 16 | |

| VK05 (5) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Ala | MeTyr | Ile | 2.7 | >75 | 1.2* | 17 | |

| VK06 (6) | Leu | MeDPhe | Ala | Sar | Phe | MeTyr | Ile | 3.9 | >75 | 2.5* | -- | |

| VK07 (7) | Leu | MeDPhe | MeAla | Sar | Phe | MeTyr | Ile | 4.1 | >75 | 7.8* | 37 | |

| VK08 (8) | Leu | MeDAla | Pro | Sar | Phe | MeTyr | Ile | 2.7 | >75 | 1.3* | n.d. | |

| VK09 (9) | Ala | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe | MeTyr | Ile | 3 | >75 | 2.2 | 9 | |

| N-methyl Scan | VK10 (10) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe | Tyr | Ile | 4 | 8 | 1.6 | 25 |

| VK11 (11) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Gly | Phe | MeTyr | Ile | 4 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 7 | |

| VK12 (12) | Leu | DPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe | MeTyr | Ile | 4 | 28+ | 0.7 | 37 | |

| VK13 (13) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe | Phe | Ile | 4.3 | >75 | 1.7 | 14 | |

| VK14 (14) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Gly | Phe | MePhe | Ile | 4.3 | 19 | 0.9 | 2 | |

| VK15 (15) | Leu | DPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe | MePhe | Ile | 4.3 | >75 | 3.9 | 23 | |

| VK16 (16) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe | MeTyr | MeAla | 4.4 | 38 | 6.7 | 56 | |

| Halogen and Heterocyclic Substitutions | VK19 (19) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe(2-F) | MeTyr | Ile | 4.4 | 1.3 | 2.5 | -- |

| VK20 (20) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe(3-Cl) | MeTyr | Ile | 4.9 | 52 | 1 | 3 | |

| VK21 (21) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe(4-Cl) | MeTyr | Ile | 4.9 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 0.3 | |

| VK22 (22) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe(4-F) | MeTyr | Ile | 4.4 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 8 | |

| VK23 (23) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Ala(β-2-fur) | MeTyr | Ile | 3.3 | >75 | 3.4 | 58 | |

| VK24 (24) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Ala(β-3-pyr) | MeTyr | Ile | 3.1 | >75 | n.d. | 516 | |

| VK25 (25) | Leu | MeDPhe(4-Cl) | Pro | Sar | Phe | MeTyr | Ile | 4.9 | 28+ | 1 | 0.5 | |

| VK26 (26) | Leu | MeDPhe(4-F) | Pro | Sar | Phe | MeTyr | Ile | 4.4 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 4 | |

| VK27 (27) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Gly | Phe(2-F) | MeTyr | Ile | 4.2 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 156 | |

| VK28 (28) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Gly | Phe(3-Cl) | MeTyr | Ile | 4.7 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 0.8 | |

| VK29 (29) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Gly | Phe(4-Cl) | MeTyr | Ile | 4.7 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.9 | |

| VK30 (30) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Gly | Phe(4-F) | MeTyr | Ile | 4.2 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 2 | |

| VK32 (32) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Gly | Ala(β-3-pvr) | MeTyr | Ile | 2.9 | >75 | n.d. | 5 | |

| VK33 (33) | Leu | MeDPhe(4-Cl) | Pro | Gly | Phe | MeTyr | Ile | 4.7 | 19+ | 0.8 | 0.8 | |

| VK34 (34) | Leu | MeDPhe(4-F) | Pro | Gly | Phe | MeTyr | Ile | 4.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 10 | |

| VK35 (35) | Leu | MeDPhe(4-F) | Pro | Gly | Phe(4-F) | MeTyr | Ile | 4.4 | 22 | 0.7 | 19 | |

| Other | VK36 (36) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe | MeTyr(OAc) | Ile | 4.2 | 3.3 | 0.4 | 5 |

| VK40 (40) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Gly | Phe(4-F) | MePhe | Ile | 4.5 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 23 | |

| VK41 (41) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | β-Ala | Phe(4-F) | MeTyr | Ile | 4.3 | 28 | 2.7 | 3 | |

| VK42 (42) | Leu | MeDPhe | Pro | Sar | Phe | MeTyr | Nva | 4.4 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 18 | |

= data reported in Naylor et al. (2018)7

= none detected

= indicated no measurement was taken

= estimated

Using the modularity of our new cordyheptapeptide synthesis, we generated structural variants aimed at probing structure-permeability and structure-activity relationships (SAR). Though 1 and 2 differ by only one hydroxyl, with a Tyr vs. Phe, respectively, at position 6, 1 is 5.5-fold more potent than 2 in terms of their antiproliferative activity in HCT 116 cells (Table 1). To further investigate this SAR and potentially improve the bioactivity of 1, we generated a series of derivatives by varying each of its seven residues (Table 1).

An alanine scan of 1 revealed that all side chains are critical to its antiproliferative activity (3 – 9, IC50 > 75 μM, Table 1, Supplementary Figure 1) and suggested that that each residue is essential to target engagement, secondary structure, or cellular permeability. Since there are a wide variety of commercially available, non-proteinogenic L-Phe and D-Phe derivatives, we synthesized a small SAR series based on variations at D-Phe2 and Phe5. All compounds from this initial SAR series (19 – 26) were less potent than 1, ranging from moderately active (IC50 = 1 μM) to inactive (IC50 > 75 μM) (Table 1, Supplementary Figure 1).

Since these initial SAR studies yielded no compounds with improved potency over the parent natural product, and because 1 showed only modest permeability (Pe = 1.2 x 10−6 cm/s) and relatively low aqueous solubility (3.9 μM) (Table 1), we considered whether potency could be improved by increasing the compound’s physicochemical properties. As backbone N-methylation causes a complex interplay of both local and global effects on permeability and bioactivity,15-18 we synthesized a variety of backbone N-Me variants of 1. Removal of any individual N-Me from 1 led to a decrease in potency, although the severity of this loss varied. Sar4 (11) was most tolerant of N-Me removal (IC50 = 0.5 μM), followed by Tyr6 (10, IC50 = 8 μM), and then D-Phe2 (12, IC50 = 28 μM). However, whereas removal of the N-Me at D-Phe2 also diminished permeability significantly, N-Me removal at Tyr6 did not affect permeability. Interestingly, while removal of the N-Me at Sar4 (11) also had no impact on permeability, this substitution saw only a 2.5-fold loss in potency (IC50 = 0.5 μM). We hypothesized that introducing amino acids with more conformational freedom, for example, substituting Pro3 for a MeAla, might allow for an alternative conformation with higher permeability. Indeed, the substitution of Pro3 for MeAla (7), which does not substantially change the calculated lipophilicity of the compound, resulted in a significant increase in permeability from 1.2 x 10−6 cm/s to 7.8 x 10−6 cm/s. This suggests that the Pro-containing natural product has a more restricted conformational landscape, thereby limiting access to nonpolar conformations in the membrane's low dielectric. Similarly, substituting Sar4 for a the more flexible β-alanine (41) slightly improved permeability (2.7 x 10−6 cm/s) over 1. Though both the Pro3MeAla and Sar4β-alanine were more permeable, these modifications also eliminated antiproliferative activity in HCT 116 cells.

Since the Sar4Gly substitution had no deleterious effect on permeability and showed only a modest decrease in potency (11, IC50 = 0.5 μM), we reasoned that the resulting increase in backbone flexibility could yield an SAR series with more opportunity for side chain optimization than the more rigid, natural backbone afforded. Thus, for 27 – 35 we substituted Sar4 with Gly4, making the same substitutions at positions 2 and 5 as described for 19 – 26 (Table 1). Notably, except for the compounds that remained inactive in both sets, the Gly4-substituted compounds were overall more active than their Sar4 counterparts, with a 3- to 260-fold improvement in IC50 (Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Table 3). Considering that the Gly compounds had similar solubilities and similar or slightly lower permeabilities compared to their Sar-containing matched pairs, the improved bioactivity may be derived from increased access to conformations that interact favorably with the target. Furthermore, 30 (Phe5Phe[4-F] and Sar4Gly) was equipotent to 1 and had comparable permeability and solubility. Applying the same modifications in 30 to cordyheptapeptide B (2) yielded an equipotent compound that had 10-fold higher solubility (40). Given that amide cis-trans isomerism in Pro and N-Me residues can dramatically change a cyclic peptide's overall conformation, the preservation (and in some cases, enhancement) of biological potency in the Gly4 series compared to their Sar4 congeners suggests that in its bioactive, target-bound state, the amide bond at Sar4 in 1 is in the trans configuration.

Molecular dynamics simulations

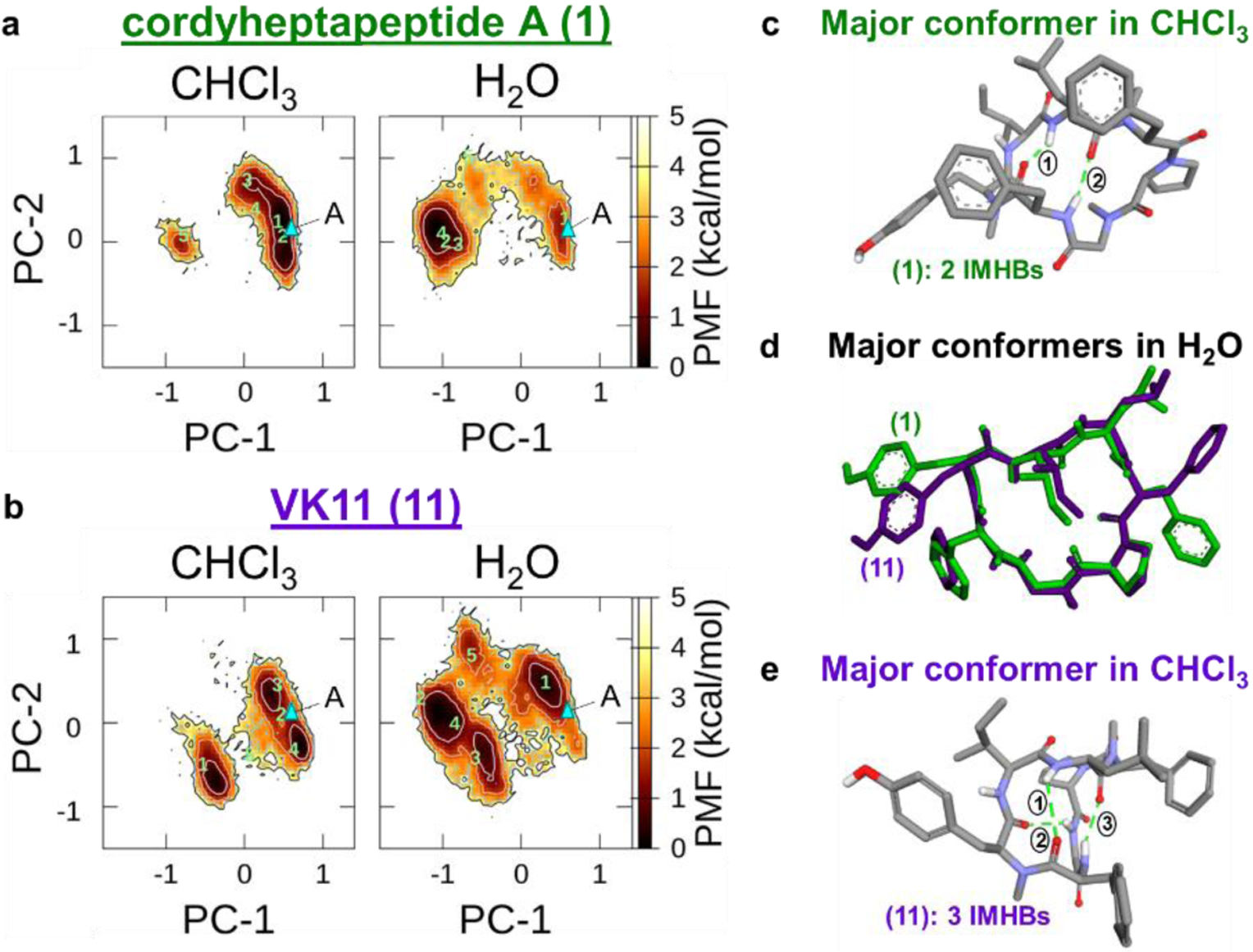

To explore the hypothesis that conformational flexibility and/or cis-tran isomerism at Sar4 impacts properties as well as the observed SAR in this series, we studied the conformations of 1 (Sar4) and 11 (Gly4) in low- and high-dielectric media using multicanonical molecular dynamics (McMD) simulations. McMD19-21 randomly samples a potential energy space, thereby overcoming large energy barriers such as cis-trans isomerization of Pro and N-methylated amino acids. The MD-derived free energy landscapes of 1 and 11 showed that 11 populates a wider variety of conformational states and is more flexible (2-fold in chloroform and 4-fold in water) compared to the parent natural product, 1 (Figure 2A-B, Supplementary Table 4). For example, in membrane-like chloroform, 1 adopted one major conformer with two intramolecular hydrogen bonds (IMHBs) for 47% of the MD simulation (Supplementary Figure 3A). On the other hand, the more flexible 11 had two major conformers each with three IMHBs for a combined total of 68% (Supplementary Figure 3B). Importantly, the newly exposed NH at position 4 participated in this new third IMHB in 11. This suggests that 11 can access multiple conformation in which the additional HBD is not solvent exposed, providing an explanation as to why removal of this N-Me did not cause a significant loss in permeability. Additionally, based on an average from 5,000 conformers, 1 and 11 have broadly comparable polar surface areas (PSA) in chloroform (159 ± 11 Å2 and 164 ± 18 Å2, respectively), supporting the conclusion that the Gly -NH is shielded from solvent. NMR temperature coefficient experiments in chloroform also showed significant changes in the chemical shift of this newly exposed amide NH suggesting a conformational change and increased access to multiple conformations (Supplementary Figures 4-5). Also consistent with the similar biological activities among the two series, the amide dihedral between Gly4 and Phe5 (11) was trans over the entire McMD trajectory in both water and chloroform. The corresponding dihedral in 1 (Sar4-Phe5) was also in the trans geometry in all of the snapshots in water and in 81% of the chloroform conformers.

Figure 2.

Molecular dynamics results comparing cordyheptapeptide A (1) and 11 a – b) Principal component (PC) analysis of free energy landscapes in chloroform (CHCl3) and water (H2O) for a) 1 and b) 11. The triangle in cyan labeled with “A” denotes the mirror-imaged X-ray structure (CCDC 287376). Green numbers within each plot indicate representative structures in each solvent. c) Major MD simulated conformer of 1 in chloroform. d) Overlay of the major conformer in water for 1 (in green) and 11 (in purple). e) Major MD simulated conformer of 11 in chloroform.

While 11 is more flexible in a hydrophobic environment and has access to greater conformational space, the major McMD-derived conformers of 11 and 1 are similar in water, with an average backbone RMSD of 0.5 Å (Figure 2D). Though these conformations do not necessarily reflect the target-bound state for either compound, the similarities of the major conformers for the two compounds suggest that the more flexible 11 could still interact with the same target binding site as 1. Increased scaffold flexibility within the Gly series likely accounts for the generally increased potency compared to Sar matched pairs (Table 1, Supplementary Table 3) as the more flexible Gly scaffolds may be capable of accessing conformations with improved binding interactions.

To corroborate our MD results and the compared number of HBDs between 1 and 11, we used a lipophilic permeability efficiency (LPE) metric. LPE is a metric devised previously by our group that uses an experimentale decadiene-water partition coefficient (LogDdec/w) to assess passive permeability, normalized to the bulk calculated lipophilicity metric ALogP.7 Each solvent-exposed HBD in low-dielectric media is expected to reduce LPE by 1.5 – 2 units. For example, compounds 1 and 2 differ in only one hydroxyl HBD (Tyr6 vs. Phe6, respectively), causing an LPE drop of 1.4 (LPE 1 = 2.3, LPE 2 = 3.7). A similar LPE difference of 1.9 is observed between 11 and 14 for the same exposed Tyr (LPE 11 = 2.0, LPE 14 = 3.9). However, the small LPE differences between 1 and 11 (LPE = 2.3 and 2.0, respectively) and between 2 and 14 (LPE = 3.7 and 3.9, respectively) reinforce the MD prediction that the new NH at position four is not exposed but is hidden within an IMHB, masking its polarity in the low dielectric of the membrane (Supplementary Figure 3, Supplementary Table 2).

NCI COMPARE and Cytological Profiling

The pattern of cytotoxicity for the cordyheptapeptides has been well established, but its target and mechanism of action (MOA) have remained obscure. To investigate the MOA of 1, we obtained an independent phenotypic profile of 1 using the NCI60 human tumor cell line assay from the Developmental Therapeutics Program at the National Cancer Institute and its associated analysis algorithm, COMPARE.22, 23 The NCI60 assay has commonly been used to identify mechanisms of action.24 Compounds with highly correlated COMPARE signatures are suggested to have similar mechanisms of action. The NCI60 activity profile of 1 correlated most highly with that of 1 was phyllanthoside, a known eukaryotic protein synthesis inhibitor that binds directly to the 80S ribosome and blocks translation elongation.25, 26 Other compounds with similar, albeit lower, COMPARE correlations to 1 included microtubule poisons, DNA intercalators, and other eukaryotic protein synthesis inhibitors (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

COMPARE results and cytological profiling dendrogram fingerprint a) Top ten compounds with known MOA25, 27-36 from COMPARE analysis ordered by COMPARE correlation to 1 b) Cytological profiling results of 1 compared to DMSO controls, normalized with features represented on a scale from −1 (blue, below DMSO control) to +1 (yellow, above DMSO control) with black indicating no difference between compound and DMSO for that feature.

To augment the COMPARE data, we turned to another "guilt-by-association" approach based on quantifiable cytological phenotypes derived from fluorescence microscopy images. This method, called cytological profiling (CP), uses automated fluorescence microscopy and unbiased image analysis to correlate the cordyheptapeptide phenotype with that of compounds from a reference library of known drugs.37, 38 Briefly, HeLa cells were incubated with the compound of interest for 18 h and then stained with fluorescent probes for DNA (Hoechst), S-phase (EdU), and mitotic cells (anti-phospho-histone H3), actin (phalloidin), and tubulin (anti-tubulin mAb). Computational analysis of the combined images yielded 254 cytological features, normalized to DMSO controls, to provide a fingerprint for each compound (Figure 3B). Similar to COMPARE, compounds with a similar mechanism of action have similar fingerprints and cluster together. Our reference library contained 25 compounds with MOAs including protein synthesis inhibitors, DNA synthesis modulators, cell cycle modulators, and microtubule poisons (see Supplementary Figure 8 for full list) at three concentrations (50 μM, 10 μM, and 2 μM). Across all three concentrations, compound 1 clustered most closely to a variety of eukaryotic protein synthesis inhibitors, including bouvardin, phyllanthoside, cycloheximide, didemnin B, ternatin, anisomycin, and ansatrienin A (Figure 3B). Moreover, 1 was further distinguished from the microtubule poisons and DNA synthesis inhibitors, which clustered more closely to 5, a much less active cordyheptapeptide derivative (Figure 3B, Supplementary Figure 8-9). These corroborating results pointed toward protein synthesis inhibition as a likely MOA of 1.

The fluorescent microscopy images from CP also allowed us to directly eliminate the microtubule cytoskeleton as the relevant MOA of cordyheptapeptide. The COMPARE results for 1 showed a correlation with three microtubule poisons that are known to cause mitotic arrest (vinorelbine, vinblastine, and paclitaxel).39-41 In contrast, 1 caused a decrease in the percentage of mitotic cells compared to a DMSO control as measured by the anti-phospho-histone H3 mitotic marker (Supplementary Figure 6A-B), providing strong evidence that 1 does not act as a classic microtubule-modulating antimitotic drug. Furthermore, the tubulin images of cells incubated with 1 were largely similar to those of cells treated with DMSO (Supplementary Figure 6C-D). This lack of aberrant tubulin staining argues against a mechanism similar to microtubule poisoning.

NCI60 results from specific cell lines also allowed us to eliminate poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibition as a potential mechanism of action. PARP inhibitors like olaparib have been shown to be synthetically lethal with BRCA1-negative breast cancer cell lines.42 However, the NCI60 dose-response assay showed 1 to have similar IC50s in both BRCA1 positive and negative breast cancer cell lines (Supplementary Figure 7). Therefore, the NCI60 COMPARE data do not support PARP inhibition as an MOA for 1. The fingerprint of 1 was also distinguished from the PARP inhibitor olaparib in the CP clustering. Thus, the combination of CP and COMPARE allowed us to eliminate both the microtubules and PARP as potential targets.

Protein synthesis and DNA synthesis

Protein synthesis was measured using the bioorthogonal noncanonical amino acid tagging (BONCAT) method, a fluorescent microscopy-based, radiation-free alternative to the classic 35S-methionine incorporation assay.43, 44 A 24-h treatment with compound 1 caused a dose-dependent decrease in protein synthesis as measured by BONCAT in HeLa cells (IC50 = 0.1 μM, Figure 4A-C), consistent with the clustering of 1 with known translation inhibitors in both the NCI60 and cytological profiling assays.

Figure 4.

Effects of cordyheptapeptide A on protein synthesis and DNA synthesis a – b) Representative images of HeLa cells stained for the following features: nuclei (Hoechst, blue), protein synthesis (BONCAT, green) after a 24-h incubation with a) DMSO orb) 100 nM 1. c) Effect of 1 on normalized cell average BONCAT intensity in HeLa cells. d – e) Representative images of HeLa cells stained for the following features: nuclei (Hoechst, blue), and S-phase cells (EdU, yellow) d) DMSO or e) 0.6 μM 1. f) Effect of 1 on normalized EdU intensity in HeLa cells. Scale bars: 211 μm. Error bars are one SD.

Compound 1 also induced phenotypic changes in cellular DNA content by fluorescence microscopy. Similar to BONCAT, the rate of DNA synthesis is measured by treating cells with a 1-h pulse of ethynyl-deoxyuridine (EdU), which is incorporated into DNA during S-phase and can subsequently be quantified by reaction with rhodamine-azide using Cu(I)-catalysis. Overall, 1 caused both a dose-dependent increase in the percentage of EdU-positive cells and a decrease in the average EdU intensity in the EdU-positive cells after a 24 h treatment in HeLa cells (IC50 = 0.2 μM, Figure 4D-F). This suggests a decrease in the rate of DNA synthesis, resulting in a build-up in the number of cells in S-phase.

Inhibition of protein synthesis has been shown to cause a decrease in the rate of DNA synthesis,25 which could account for our observation that, in addition to its effect on protein synthesis, 1 caused a significant decrease in the rate of DNA synthesis as measured by EdU uptake. However, to confirm that the effect on DNA synthesis was secondary to its effect on protein synthesis, we performed the BONCAT assay after a 3-h treatment with 1. Even at this shorter time point, 1 inhibited protein synthesis and had a more potent effect on protein synthesis than DNA synthesis. This result suggests that 1 likely acts as a direct protein synthesis inhibitor, which, in turn, has a secondary effect on DNA synthesis, consistent with both CP and NCI60 results (Figure 3B).

Intracellular target of 1 is eEF1A:

Based on the prominent inhibition of protein synthesis, we postulated that the target could be eEF1A, the 50-kDa protein elongation factor that is involved in the recruitment of aminoacyl-tRNA to the A-site of the 80S ribosome. The protein eEF1A is essential for protein synthesis in eukaryotes, and it is inhibited by several structurally unrelated and cytotoxic cyclic peptide natural products including didemnin B and ternatin (including its more potent analog ternatin-4). In their confirmation of eEF1A as the cellular target of ternatin and its improved variant ternatin-4, Carelli et al. showed that a point mutation in eEF1A (A399V) confers complete resistance.45 A variety of structurally unrelated eEF1A inhibitors are also inactive against this mutant cell line.45 While 1 caused a dose-dependent reduction in wildtype HCT 116 cell proliferation (IC50 ~ 0.2 μM), this effect was dramatically reduced in the A399V eEF1A mutant cells by more than 20-fold (IC50 ~ 7 μM, Figure 5). This genetic evidence strongly suggests that eEF1A is the direct intracellular target of cordyheptapeptide A.

Figure 5. Target identification.

eEF1A WT HCT 116 cells and eEF1A A399V HCT 116 cells were incubated with 1 for 72 hours. Cell proliferation was measured with and Alamar blue assay. Error bars are one SD.

Overexpression of eEF1A is associated with several cancer types and has been recently identified as a potential drug target in the development of SARS-CoV-2 anti-viral therapeutics.46, 47 Cordyheptapeptide A is another macrocyclic natural product shown to target eEF1A and inhibit protein synthesis. This list of structurally diverse natural products includes ternatin,45 didemnin B,48 plitidepsin,49 nannocystin A,50 and ansatrienin B.45 While there are major differences in their overall structures, the above compounds are all large, hydrophobic molecules. Our study adds to the mounting evidence that successful inhibition of this target requires a large, “beyond-Rule-of-5” (bRo5) molecule. The high potencies of these compounds support the continuation of work to investigate the design and synthesis of natural product-like drug molecules dominated by hydrophobic- and aromatic-rich side chains.17, 51, 52 Additional investigation of these compounds could lead to a better understanding of the binding mechanisms of eEF1A and allow for faster MOA identification of novel natural products that fit into this class of protein synthesis inhibitors.

The synthetic and natural cordyheptapeptides in this study showed weak to moderate passive permeability coefficients in PAMPA ranging from 0.2 x 10−6 cm/s to 7.8 x 10−6 cm/s. The seven compounds with sub-micromolar cellular activities, including the parent natural product 1, were not among the most permeable in this study, with Pe values ranging from 0.9 x 10−6 to 1.3 x 10−6 cm/s. Many of the backbone modifying substitutions in this series led to enhanced permeability, including the substitution of Pro with Ala (6) or MeAla (7), removal of a backbone N-Me (15), or substitution of an α- with a β-amino acid (41). The impact of these substitutions on permeability is perhaps not surprising given the established sensitivity of passive permeability to backbone conformation. Unfortunately, each of these substitutions caused a dramatic decrease in cellular potency, highlighting the difficulty of optimizing permeability in cyclic peptide scaffolds without abrogating biochemical efficacy.53, 54

Changing the N-methylation pattern of the cyclic peptide backbone can also dramatically modulate its bioactivity.53, 54 This is most evident when the removal of the N-Me at position four was combined with halogenating a Phe (19 – 26 vs. 27 – 34) in which the Gly compounds (27 – 34) are active than the Sar derivatives despite generally having similar permeabilities and solubilities as their Sar-containing counterparts (19 – 26). The more flexible Gly derivatives could allow for conformations yielding increased access to favorable halogen-to-target binding. Alternatively, it is also possible that this increased bioactivity is derived from a new intermolecular hydrogen bond between the newly exposed -NH at position four and the protein target, eEF1A. This hypothesis is supported by recent reviews which have suggested that cyclic peptide backbone amides are responsible for a significant a significant portion of target binding.55

This study highlights the interwoven nature of macrocycle bioactivity and physicochemical properties, and a strategy to optimize these properties simultaneously via classical synthetic techniques such as alanine, N-Me, and isostere scanning. In particular, a demethylation at position a yielded new scaffolds (27, 28, and 30) with maintained potency and permeability relative to cordyheptapeptide A (1), and a two-fold increase in bioactivity for another (40) relative to cordyheptapeptide B (2). Furthermore, this modification, in conjunction with a fluorine substitution, improved the activity of 2 to nearly that of 1, the more active natural product. Consequently, modifications to the N-methylation pattern of a cyclic peptide scaffold offer effective strategies to improve the potency and oral bioavailability of bRo5 molecules in addition to the inclusion of more exotic, “druglike” side chains. This work improves our understanding of the physicochemical properties of cyclic peptide natural products. Additionally, it confirms that lipophilic macrocycles are capable of inhibiting intracellular proteins responsible for cellular growth, motivating further investigation of cyclic peptides as modulators of other protein targets once thought to be “undruggable”.

METHODS:

General:

Commercially available chemicals were used without further modification unless otherwise specified. Reagents and solvents were purchased from Fisher Scientific. HATU was purchased from Combi-Blocks or Chem-Impex. Amino acids were purchased from Combi-Blocks, Chem-Impex, Sigma-Aldrich, or Oakwood unless otherwise stated. Piperidine and 1,9-decadiene were purchased from Spectrum Chemical and TCI Chemicals, respectively. Polystyrene 2-chlorotrityl resin was purchased from Rapp-Polymere (H10033). Antibodies were purchased from Thermo Scientific and Sigma Aldrich. LCMS compound purity analysis was performed on a Thermo Scientific Ultimate 3000 UPLC system with a Thermo Scientific OrbiTrap VelosPro mass spectrometer. This system used a Thermo Hypersil GOLD C18 (30 mm x 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm particle size) column eluting in water/acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Advance III HD 500 MHz 5 mm BBO Smart Probe in CDCl3.

Cell Culture:

Unless otherwise noted cell culture was performed using Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Corning 10013CVMP) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Corning 35-015-CV) and penicillin (100 U/mL)/streptomycin (100 μg/mL) (Gibco, ThermoFisher Scientific 15070063). Cells were maintained with phosphate-buffer saline (PBS) (Gibco 14190235) and a solution of 0.25% trypsin with 2.21 mM EDTA (Corning 25-053-CI). All cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. For mutant cell line proliferation used in target ID, HCT116 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and HCT116-417 (mutant) cells were maintained in McCoy’s 5A media (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Axenia Biologix, Dixon, CA), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 ug/mL streptomycin (Gibco).

Cell proliferation:

Adherent HCT 116 cells were plated at a density of 1,200 cells/well at 30 μL per well in a 384-well plate (Greiner Bio-One 781090) or at a density of 2,500 cells/well at 100 μL per well in a 96-well plate (Greiner Bio-One 07000166) and allowed to adhere overnight. The following day, compounds were added using a PerkinElmer Janus MDT pinning robot from a 384-well DMSO compound stock plate or pipetted from a 100x 96-well stock plate giving a range of concentrations in the assay plate from 4.5 nM to 75 μM in 1:2 dilutions for 384-well plate and 1:dilutions for the 96-well plate. The cells were incubated for 72 hours at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Resazurin stock solution (sodium salt, in PBS) was added using an Finstruments Multidrop 384 automatic dispenser for a final resazurin concentration of 0.1 mg/mL per well. The cells were for an additional 90 minutes at 37 °C and 5% CO2, after which a Perkin Elmer EnVision plate reader (2103 Multilabel Reader) was used to quantify fluorescence. Cell proliferation fluorescence was normalized to the average fluorescence of control cells incubated with DMSO in each assay plate. This assay was performed in biological and technical triplicate (n = 3) taken from distinct samples. IC50 values were calculated with GraphPad Prism (v 8.4.1) except for compounds 12, 25, and 33 which were estimated graphically.

Cytological profiling (CP):

Cytological profiling (CP)37, 56 was performed following the procedure described in Schulze et al38 with the following modifications. Adherent HeLa cells were plated at a density of 3,600 cells/well at 100 μL per well in a 384-well plate and allowed to adhere overnight. The following day, compounds were added using a PerkinElmer Janus MDT pinning robot from a compound stock plate giving a range of concentration in the 384-well plate (Greiner Bio-One 781090) from 4.5 nM to 75 μM. The cells were incubated with compound for 18 hours at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Prior to fixing and staining, cells were incubated with 20 μM EdU57 in DMEM for 45 minutes at 37 °C. Cells were fixed in a 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 minutes at room temperature. Cells were washed three times with a BioTek automatic plate washer. Next, to permeabilize the cell membrane, cells were incubated in PBS with 0.5% Triton X for 10 minutes followed by another set of three washes on the plate washer. To prepare cells for antibody treatment, they were blocked with a solution of 2% BSA in PBS for 20 minutes at room temperature then washed again. Click chemistry was performed by adding a master mix of click reagents to the cells (4mM CuSO4, 2mg/mL sodium ascorbate, and 0.1 mM rhodamine azide in 100 mM Tris buffer pH 7.4). This master mix was made just before adding it to the cells which were then incubated for one hour at room temperature in the dark. The cells were washed, and the appropriate primary antibodies (rabbit anti-phospho histone-H3 (9H12L10, ThermoFisher Scientific 701258) or FITC-anti-tubulin (Sigma Aldrich F2043)) were added in PBS with 2% BSA and incubated at 4 °C for 18 hours. The following day, the cells were washed with PBS to remove excess primary antibody. Then the secondary antibody (chicken anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647, ThermoFisher scientific A-21443) was added along with rhodamine-phalloidin and Hoechst 33342 (Anaspec Inc 83218) stain in PBS with 2% BSA. The cells were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. Cells were washed with PBS on the automatic plate washer. After which, the plates were imaged using an ImageXpressMicro XLS epifluorescent microscope (Molecular Devices). The resulting images were analyzed using MetaXpress (v. 6.2.1.704, Molecular Devices) and built-in multi-wave cell scoring. These values were converted to feature scores and clustered and analyzed using Cytoscape (v 3.7.0, Pearson absolute correlation, maximum linkage). (n = 1)

Bioorthogonal Non-canonical Amino Acid Tagging (BONCAT) Assay:

Adherent HeLa cells were plated at a density of 10,000 cells in 100 μL DMEM per well in 96-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight. Compounds were added as DMSO stocks dissolved in DMEM in 1:3 dilutions in concentrations from 34 nM to 75 μM for 1 and 9 nM to 22 μM for didemnin B, a positive control. DMSO was used as a negative control.

For the 24 hr time point, cells were incubated with compounds for 24 hours in DMEM at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The media was removed and replaced with 100 μL of media without methionine (“DMEM –Met”) (Thermo Fisher catalog #21013024, with added 1mM sodium pyruvate, 0.584 g/L glutamine, penicillin (100 U/mL)/streptomycin (100 μg/mL)) was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 1 hr at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After this, 10 μL of 1 mM L-homopropargylglycine (L-HPG) in DMEM -Met was added to each well. Again, the plates were incubated for 1 hour 37 °C and 5% CO2. For the 3 hr time point, cells were incubated with compound for 1.5 hours in “DMEM –Met” at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After this, 10 μL of 1 mM of L-HPG in DMEM -Met was added to each well and incubated for another 1.5 hours 37 °C and 5% CO2. This assay was performed in technical triplicate (n = 3) taken from distinct samples.

For both time points, cells were fixed in a 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 minutes at room temperature. Cells were washed three times with a BioTek automatic plate washer. Next, to permeabilize the cell membrane, cells were incubated in PBS with 0.5% Triton X for 10 minutes followed by another set of three washes on the plate washer. To prepare cells for antibody treatment, they were blocked with a solution of 2% BSA in PBS for 20 minutes at room temperature then washed again. Click chemistry was performed by adding a master mix of click reagents to the cells (4mM CuSO4, 2mg/mL sodium ascorbate, and 0.1 mM rhodamine azide in 100 mM Tris buffer pH 7.4). This master mix was made just before adding it to the cells which were then incubated for one hour at room temperature in the dark, then washed. After which, Hoechst was added in PBS with 2% BSA. Cells were incubated for 20 minutes in the dark at room temperature, and then washed. After which, the plates were imaged using an ImageXpressMicro XLS epifluorescent microscope (Molecular Devices). The resulting images were analyzed using MetaXpress (v. 6.2.1.704, Moleular Devices) and built-in multi-wave cell scoring.

NCI COMPARE Analysis:

Testing was performed by the Developmental Therapeutics Program, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute (http://dtp.cancer.gov). Cordyheptapeptide A (NSC number: S812201) was sent to the Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP) at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to be analyzed in their human tumor cell line assay. Details of this assay protocol can be found in related publications on the DTP website.22,23,58 Briefly, 59 human tumor cell lines were screened against 1 and analyzed for total growth inhibition (TGI), GI50 (concentration of 1 that causes 50% of growth inhibition), and LC50 (concentration of 1 at which half of the cells are killed). Using the NCI60 COMPARE algorithm, the GI50 of 1 in these cell lines was compared to the GI50 of the DTP’s list of “Standard Agents” using the following parameters: minimum correlation (0.2), count results to return (50), minimum count common cell lines (40), and minimum standard deviation (0.05).23,25The compounds were rank ordered by correlation from highest to lowest. If duplicate reference compounds were in the top 50 results, the average correlation is reported. The top 10 compounds are reported here with their COMPARE correlation value to 1 and a brief description of their mechanism of action. GI50 was chosen for follow-up studies because 1 was more highly correlated to other compounds from the “Standard Agent” set by this metric than either TGI or LC50.

Cell proliferation in mutant eEF1a cell line:

HCT116 or HCT116-417 cells were briefly trypsinized and repeatedly pipetted to produce a homogenous cell suspension. 2,500 cells were seeded in 100 uL complete growth media per well in 96-well clear-bottom plates. After allowing cells to grow/adhere overnight, cells were treated with 25 uL/well 5x drug stocks (0.1% DMSO final) and incubated for 72 hours. AlamarBlue (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) was used to assess cell viability per the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 12.5 uL alamarBlue reagent was added to each well, and plates were incubated at 37°C. Fluorescence intensity was measured every 30 min to determine the linear range for each assay (Ex 545 nm, Em 590 nm, SPARK, Tecan Austria GmbH, Austria). Proliferation curves were generated by first normalizing fluorescence intensity in each well to the DMSO-treated plate average. Normalized fluorescence intensity was plotted in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA), and IC50 values were calculated from nonlinear regression curves. The reported IC50 values represent the average of at least three independent determinations (n = 3, ±SD).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

We thank C. Townsend for his Python code. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (NSF DGE 1339067 to V.G.K.), Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program Postdoctoral Fellowship (28FT-0014 to H.-Y. W.), the National Institute of General Medicine Studies of the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01GM13113 to R.S.L), and E. Lilly and Co. (Lilly Innovation Fellowship Award to M.R.N.). The UCSC Chemical Screening Center was supported by S10 RR022455. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation or the National Institutes of Health. Testing was performed by the Developmental Therapeutics Program, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute. More information on this can be found on the Program’s website: http://dtp.cancer.gov.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- ACN

acetonitrile

- BONCAT

Bioorthogonal Non-canonical Amino Acid Tagging

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- COMU

(1-Cyano-2-ethoxy-2-oxoethylidenaminooxy)dimethylamino-morpholino-carbenium hexafluorophosphate

- CP

cytological profiling

- DBU

1,8-Diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DIAD

diisopropyl azodicarboxylate

- DIPEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- DMEM

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DTP

Development Therapeutics Program (at the National Cancer Institute)

- EdU

5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine

- eEF1A

eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1-alpha

- EtOH

ethanol

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- Fmoc

fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl protecting group

- GI50

concentration at which a compound causes 50% of growth inhibition

- HATU

1-[Bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxide hexafluorophosphate

- HFIP

hexafluoroisopropanol

- LC50

concentration of compound at which half of the cells are killed (lethal dose)

- L-HPG

L-homopropargylglycine

- LogD(dec/w)

shake-flask partition coefficient between 1,9-decadiene and water

- LPE

lipophilic permeability efficiency

- MD

molecular dynamics

- MOE

molecular operating environment

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- PAMPA

parallel artificial membrane permeability assay

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- SPPS

solid-phase peptide synthesis

- TES

triethyl silane

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TGI

total growth inhibition

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- TIC

total ion chromatogram

- Xaa

unspecified amino acid

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT:

Authors declare no competing financial interests.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE:

This material is available free of charge via the Internet. Supporting information contains: Additional methods for solid-phase peptide synthesis and physicochemical assays, solid-phase synthesis scheme, supporting figures and tables, and LCMS and NMR compound characterization data.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Bockus AT; McEwen CM; Lokey RS, Form and Function in Cyclic Peptide Natural Products: A Pharmacokinetic Perspective. Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2013, 13 (7), 821–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zorzi A; Deyle K; Heinis C, Cyclic Peptide Therapeutics: Past, Present and Future. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2017, 38, 24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pye CR; Bertin MJ; Lokey RS; Gerwick WH; Linington RG, Retrospective Analysis of Natural Products Provides Insights for Future Discovery Trends. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2017, 114 (22), 5601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marsault E; Peterson ML, Macrocycles Are Great Cycles: Applications, Opportunities, and Challenges of Synthetic Macrocycles in Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54 (7), 1961–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Driggers EM; Hale SP; Lee J; Terrett NK, The Exploration of Macrocycles for Drug Discovery - an Underexploited Structural Class. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 7, 608–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitty A; Zhong M; Viarengo L; Beglov D; Hall DR; Vajda S, Quantifying the Chameleonic Properties of Macrocycles and Other High-Molecular-Weight Drugs. Drug Discov. Today 2016, 21 (5), 712–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naylor MR; Ly AM; Handford MJ; Ramos DP; Pye CR; Furukawa A; Klein VG; Noland RP; Edmondson Q; Turmon AC; Hewitt WM; Schwochert J; Townsend CE; Kelly CN; Blanco M-J; Lokey RS, Lipophilic Permeability Efficiency Reconciles the Opposing Roles of Lipophilicity in Membrane Permeability and Aqueous Solubility. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61 (24), 11169–11182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pye CR; Hewitt WM; Schwochert J; Haddad TD; Townsend CE; Etienne L; Lao Y; Limberakis C; Furukawa A; Mathiowetz AM; Price DA; Liras S; Lokey RS, Nonclassical Size Dependence of Permeation Defines Bounds for Passive Adsorption of Large Drug Molecules. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60 (5), 1665–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Over B; Matsson P; Tyrchan C; Artursson P; Doak BC; Foley MA; Hilgendorf C; Johnston SE; Lee MD; Lewis RJ; McCarren P; Muncipinto G; Norinder U; Perry MWD; Duvall JR; Kihlberg J, Structural and Conformational Determinants of Macrocycle Cell Permeability. Nat Chem. Biol 2016, 12 (12), 1065–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olatunji OJ; Tang J; Tola A; Auberon F; Oluwaniyi O; Ouyang Z, The Genus Cordyceps: An Extensive Review of Its Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology. Fitoterapia 2018, 129, 293–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rukachaisirikul V; Chantaruk S; Tansakul C; Saithong S; Chaicharernwimonkoon L; Pakawatchai C; Isaka M; Intereya K, A Cyclopeptide from the Insect Pathogenic Fungus Cordyceps Sp. Bcc 1788. J. Nat. Prod 2006, 69 (2), 305–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isaka M; Srisanoh U; Lartpornmatulee N; Boonruangprapa T, Es-242 Derivatives and Cycloheptapeptides from Cordyceps Sp. Strains Bcc 16173 and Bcc 16176. J. Nat. Prod 2007, 70 (10), 1601–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar S; Dahiya R; Khokra SL; Mourya R; Chennupati SV; Maharaj S, Total Synthesis and Pharmacological Investigation of Cordyheptapeptide A. Molecules 2017, 22 (6), 682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner RA; Hauksson NE; Gipe JH; Lokey RS, Selective, on-Resin N-Methylation of Peptide N-Trifluoroacetamides. Org. Lett 2013, 15 (19), 5012–5015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furukawa A; Townsend CE; Schwochert J; Pye CR; Bednarek MA; Lokey RS, Passive Membrane Permeability in Cyclic Peptomer Scaffolds Is Robust to Extensive Variation in Side Chain Functionality and Backbone Geometry. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59 (20), 9503–9512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck JG; Chatterjee J; Laufer B; Kiran MU; Frank AO; Neubauer S; Ovadia O; Greenberg S; Gilon C; Hoffman A; Kessler H, Intestinal Permeability of Cyclic Peptides: Common Key Backbone Motifs Identified. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134 (29), 12125–12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwochert J; Lao Y; Pye CR; Naylor MR; Desai PV; Gonzalez Valcarcel IC; Barrett JA; Sawada G; Blanco M-J; Lokey RS, Stereochemistry Balances Cell Permeability and Solubility in the Naturally Derived Phepropeptin Cyclic Peptides. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2016, 7 (8), 757–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang CK; Craik DJ, Cyclic Peptide Oral Bioavailability: Lessons from the Past. Pept. Sci 2016, 106 (6), 901–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakajima N; Nakamura H; Kidera A, Multicanonical Ensemble Generated by Molecular Dynamics Simulation for Enhanced Conformational Sampling of Peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101 (5), 817–824. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higo J; Umezawa K; Nakamura H, A Virtual-System Coupled Multicanonical Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Principles and Applications to Free-Energy Landscape of Protein–Protein Interaction with an All-Atom Model in Explicit Solvent. J. Chem. Phys 2013, 138 (18), 184106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ono S; Naylor MR; Townsend CE; Okumura C; Okada O; Lokey RS, Conformation and Permeability: Cyclic Hexapeptide Diastereomers. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2019, 59 (6), 2952–2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monks A; Scudiero D; Skehan P; Shoemaker R; Paull K; Vistica D; Hose C; Langley J; Cronise P; Vaigro-Wolff A; Gray-Goodrich M; Campbell H; Mayo J; Boyd M, Feasibility of a High-Flux Anticancer Drug Screen Using a Diverse Panel of Cultured Human Tumor Cell Lines. JNCI, J. Natl. Cancer Inst 1991, 83 (11), 757–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paull KD; Shoemaker RH; Hodes L; Monks A; Scudiero DA; Rubinstein L; Plowman J; Boyd MR, Display and Analysis of Patterns of Differential Activity of Drugs against Human Tumor Cell Lines: Development of Mean Graph and Compare Algorithm. JNCI, J. Natl. Cancer Inst 1989, 81 (14), 1088–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bai RL; Paull KD; Herald CL; Malspeis L; Pettit GR; Hamel E, Halichondrin B and Homohalichondrin B, Marine Natural Products Binding in the Vinca Domain of Tubulin. Discovery of Tubulin-Based Mechanism of Action by Analysis of Differential Cytotoxicity Data. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1991, 266 (24), 15882–15889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan J; Khan SN; Harvey I; Merrick W; Pelletier J, Eukaryotic Protein Synthesis Inhibitors Identified by Comparison of Cytotoxicity Profiles. RNA 2004, 10, 528–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garreau de Loubresse N; Prokhorova I; Holtkamp W; Rodnina MV; Yusupova G; Yusupov M, Structural Basis for the Inhibition of the Eukaryotic Ribosome. Nature 2014, 513 (7519), 517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gregory RK; Smith IE, Vinorelbine - a Clinical Review. Br. J. Cancer 2000, 82, 1907–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowden GT; Roberts R; Alberts DS; Peng Y.-m.; Garcia D, Comparative Molecular Pharmacology in Leukemic L1210 Cells of the Anthracene Anticancer Drugs Mitoxantrone and Bisantrene. Cancer Res. 1985, 45, 4915–4920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamiyama M, Mechanism of Action of Chromomycin A3: Iii . On the Binding of Chromomycin A3 with DNA and Physicochemical Properties of the Complex 1. The Journal of Biochemistry 1968, 63, 566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaziro Y; Kamiyama M, Mechanism of Action of Chromomycin a 3: Ii Inhibition of Rna Polymerase Reaction. The Journal of Biochemistry 1967, 62, 424–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sobell HM, Actinomycin and DNA Transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 1985, 82, 5328–5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liaoo L-I; Kuochan SM; Horwitz SB, Mode of Action of the Antitumor Compound Bruceantin, an Inhibitor of Protein Synthesis. Molecular Pharmocology 1976, 12, 167–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jordan MA; Thrower D; Wilson L, Mechanism of Inhibition of Cell Proliferation by Vinca Alkaloids. Cancer Res. 1991, 51, 2212–2222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li LH; Timmins LG; Wallace TL; Krueger WC; D PM; Im WB, Mechanism of Action of Didemnin B, a Depsipeptide from the Sea. Cancer Lett. 1984, 23, 279–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schiff PB; Fant J; Horwitz SB, Promotion of Microtubule Assembly in Vitro by Taxol. Nature 1979, 277, 665–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waring MJ; Wakelin LPG, Echinomycin: A Bifunctional Intercalating Antibiotic. Nature 1974, 252, 653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young DW; Bender A; Hoyt J; McWhinnie E; Chirn G-W; Tao CY; Tallarico JA; Labow M; Jenkins JL; Mitchison TJ; Feng Y, Integrating High-Content Screening and Ligand-Target Prediction to Identify Mechanism of Action. Nat. Chem. Biol 2008, 4 (1), 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schulze Christopher J.; Bray Walter M.; Woerhmann Marcos H.; Stuart J; Lokey RS; Linington Roger G., “Function-First” Lead Discovery: Mode of Action Profiling of Natural Product Libraries Using Image-Based Screening. Chem. Biol 2013, 20 (2), 285–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matson DR; Stukenberg PT, Spindle Poisons and Cell Fate: A Tale of Two Pathways. Molecular interventions 2011, 11 (2), 141–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mukhtar E; Adhami VM; Mukhtar H, Targeting Microtubules by Natural Agents for Cancer Therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther 2014, 13 (2), 275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.González-Cid M; Larripa I; Slavutsky I, Vinorelbine: Cell Cycle Kinetics and Differential Sensitivity of Human Lymphocyte Subpopulations1the Authors Are Members of the Research Career of Conicet (National Research Council).1. Toxicology Letters 1997, 93 (2), 171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arun B; Akar U; Gutierrez-Barrera AM; Hortobagyi GN; Ozpolat B, The Parp Inhibitor Azd2281 (Olaparib) Induces Autophagy/Mitophagy in Brca1 and Brca2 Mutant Breast Cancer Cells. Int. J. Oncol 2015, 47, 262–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dieterich DC; Link AJ; Graumann J; Tirrell DA; Schuman EM, Selective Identification of Newly Synthesized Proteins in Mammalian Cells Using Bioorthogonal Noncanonical Amino Acid Tagging (Boncat). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2006, 103 (25), 9482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dieterich DC; Hodas JJL; Gouzer G; Shadrin IY; Ngo JT; Triller A; Tirrell DA; Schuman EM, In Situ Visualization and Dynamics of Newly Synthesized Proteins in Rat Hippocampal Neurons. Nat. Neurosci 2010, 13 (7), 897–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carelli JD; Sethofer SG; Smith GA; Miller HR; Simard JL; Merrick WC; Jain RK; Ross NT; Taunton J, Ternatin and Improved Synthetic Variants Kill Cancer Cells by Targeting the Elongation Factor-1a Ternary Complex. eLife 2015, 4, e10222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blanch A; Robinson F; Watson IR; Cheng LS; Irwin MS, Eukaryotic Translation Elongation Factor 1-Alpha 1 Inhibits P53 and P73 Dependent Apoptosis and Chemotherapy Sensitivity. PLOS ONE 2013, 8 (6), e66436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White KM; Rosales R; Yildiz S; Kehrer T; Miorin L; Moreno E; Jangra S; Uccellini MB; Rathnasinghe R; Coughlan L; Martinez-Romero C; Batra J; Rojc A; Bouhaddou M; Fabius JM; Obernier K; Dejosez M; Guillén MJ; Losada A; Avilés P; Schotsaert M; Zwaka T; Vignuzzi M; Shokat KM; Krogan NJ; García-Sastre A, Plitidepsin Has Potent Preclinical Efficacy against Sars-Cov-2 by Targeting the Host Protein Eef1a. Science 2021, eabf4058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marco E; Martín-Santamaría S; Cuevas C; Gago F, Structural Basis for the Binding of Didemnins to Human Elongation Factor Eef1a and Rationale for the Potent Antitumor Activity of These Marine Natural Products. J. Med. Chem 2004, 47 (18), 4439–4452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leisch M; Egle A; Greil R, Plitidepsin: A Potential New Treatment for Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Future Oncology 2018, 15 (2), 109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krastel P; Roggo S; Schirle M; Ross NT; Perruccio F; Aspesi P Jr; Aust T; Buntin K; Estoppey D; Liechty B; Mapa F; Memmert K; Miller H; Pan X; Riedl R; Thibaut C; Thomas J; Wagner T; Weber E; Xie X; Schmitt EK; Hoepfner D, Nannocystin A: An Elongation Factor 1 Inhibitor from Myxobacteria with Differential Anti-Cancer Properties. Angew. Chem 2015, 54 (35), 10149–10154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dalsgaard PW; Larsen TO; Christophersen C, Bioactive Cyclic Peptides from the Psychrotolerant Fungus Penicillium Algidum. The Journal of Antibiotics 2005, 58 (2), 141–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naylor MR; Bockus AT; Blanco MJ; Lokey RS, Cyclic Peptide Natural Products Chart the Frontier of Oral Bioavailability in the Pursuit of Undruggable Targets. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2017, 38, 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ovadia O; Greenberg S; Laufer B; Gilon C; Hoffman A; Kessler H, Improvement of Drug-Like Properties of Peptides: The Somatostatin Paradigm. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2010, 5 (7), 655–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Todorovic A; Holder JR; Scott JW; Haskell-Luevano C, Synthesis and Activity of the Melanocortin Xaa-D-Phe-Arg-Trp-Nh Tetrapeptides with Amide Bond Modifications. J Pept Res 2004, 63 (3), 270–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Villar EA; Beglov D; Chennamadhavuni S; Porco JA Jr.; Kozakov D; Vajda S; Whitty A, How Proteins Bind Macrocycles. Nat. Chem. Biol 2014, 10 (9), 723–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Perlman ZE; Slack MD; Feng Y; Mitchison TJ; Wu LF; Altschuler SJ, Multidimensional Drug Profiling by Automated Microscopy. Science 2004, 306 (5699), 1194–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chehrehasa F; Meedeniya ACB; Dwyer P; Abrahamsen G; Mackay-Sim A, Edu, a New Thymidine Analogue for Labelling Proliferating Cells in the Nervous System. J. Neurosci. Methods 2009, 177 (1), 122–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bates SE; Fojo AT; Weinstein JN; Myers TG; Alvarez M; Pauli KD; Chabner BA, Molecular Targets in the National Cancer Institute Drug Screen. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol 1995, 121 (9), 495–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.