Abstract

Epilepsy animal models indicate pronounced changes in the expression and rearrangement of GABAA receptor subunits in the hippocampus and in para-hippocampal areas, including widespread downregulation of the subunits α5 and δ, and upregulation of α4, subunits that mediate tonic inhibition of GABA. In this case–control study, we investigated changes in the expression of subunits α4, α5 and δ in hippocampal specimens of drug resistant temporal lobe epilepsy patients who underwent epilepsy surgery. Using in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry and α5-specific receptor autoradiography, we characterized expression of the receptor subunits in specimens from patients with and without Ammon’s horn sclerosis compared to post-mortem controls. Expression of the α5-subunit was abundant throughout all subfields of the hippocampus, including the dentate gyrus, sectors CA1 and CA3, the subiculum and pre- and parasubiculum. Significant but weaker expression was detected for subunits α4 and δ notably in the granule cell/molecular layer of control specimens, but was faint in the other parts of the hippocampus. Expression of all three subunits was similarly altered in sclerotic and non-sclerotic specimens. Respective mRNA levels were increased by about 50–80% in the granule cell layer compared with post-mortem controls. Subunit α5 mRNA levels and immunoreactivities were also increased in the sector CA3 and in the subiculum. Autoradiography for α5-containing receptors using [3H]L-655,708 as ligand showed significantly increased binding in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus in non-sclerotic specimens. Increased expression of the α5 and δ subunits is in contrast to the previously observed downregulation of these subunits in different epilepsy models, whereas increased expression of α4 in temporal lobe epilepsy patients is consistent with that in the rodent models. Our findings indicate increased tonic inhibition likely representing an endogenous anticonvulsive mechanism in temporal lobe epilepsy.

Keywords: GABAA receptor subunits; [3H]L-655,708; alpha-5 subunit; hippocampus; dentate gyrus

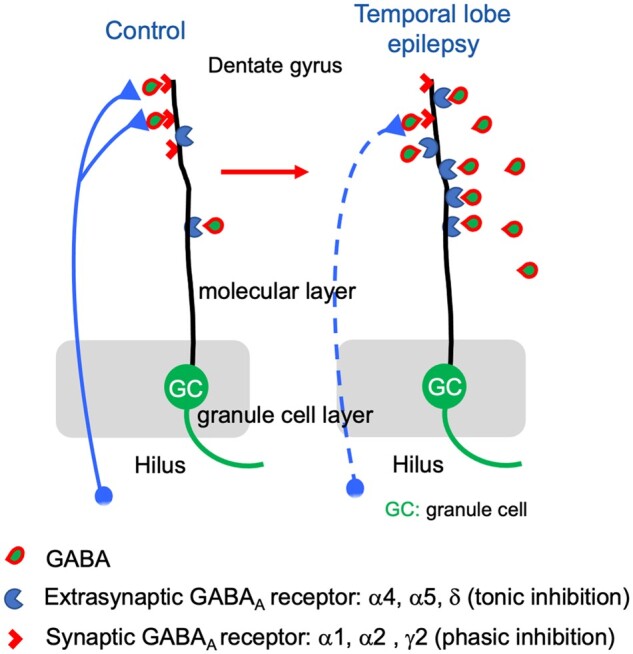

GABAA receptors containing α4, α5 and/or δ subunits receptors are located extrasynaptically and mediate volume transmission with tonic inhibition. Sperk et al. show markedly increased expression of these subunits in the hippocampus of temporal lobe epilepsy patients indicating sustained tonic inhibition as a possible endogenous anticonvulsive mechanism.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the primary inhibitory transmitter in the mammalian brain. It acts through two different classes of receptors, GABAA and GABAB receptors. Whereas GABAB receptors are metabotropic receptors, GABAA receptors represent hyperpolarizing chloride channels. GABAA receptors are assembled in a pentameric structure. Quite a large number of different possible subunit proteins (α1-6, β1-3, γ1-3, δ, ε, θ) can mutually participate in the assembly of the pentameric receptor. Although in theory a huge number of different subunit combinations would be possible, the actual number of different receptors is not as extensive since their constitution follows certain rules. In general, GABAA receptors contain two α-subunits (α1-6), two β- (β1 to β3) and either one γ2- (less frequently γ1) or one δ-subunit (rarely an ε or θ-subunit). This subunit composition crucially determines the physiological and pharmacological properties of the individual GABAA receptor subtypes.1,2 GABA binds to the interface between the respective α- and β-subunits. Benzodiazepines and the hypnotic substance zolpidem are positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors containing two α-subunits (either α1, α2, α3 or α5), two β- together with one γ-subunit (not δ). Potent endogenous modulators of GABAA receptors are neurosteroids, which act as positive allosteric modulators at the δ-subunit of the receptor.3

In the rodent dentate gyrus, the δ-subunit often assembles with α4 or α5 subunits.4–6 In the rat, these receptors are either extra- or peri-synaptically located and mediate tonic inhibition, in contrast to α1-, α2- and γ2-containing receptors that are positioned within the synapse and mediate phasic inhibition.6–9 Related to the extended distance of diffusion of GABA, extra-synaptic receptors containing the δ-subunit exert a higher affinity to GABA than γ2-subunit containing receptors.

Malfunctioning of GABA-ergic transmission can facilitate epileptic seizures. Thus, autoantibodies to the GABA-synthesizing enzyme glutamate decarboxylase in humans, knock out of the gene in mice,10–12 and mutations of the α1, β3 or γ2 subunits of the GABAA receptors are causatively associated with epilepsies.13 Furthermore, GABAA receptor antagonists like pentylenetetrazol, bicuculline or picrotoxin are potent convulsive drugs, whereas GABAA receptor agonists like benzodiazepines and barbiturates are anticonvulsive.14

Significant changes in the expression and assembly of individual GABAA receptor subunits are seen in animal models of epilepsy. Presumably due to the strongly enhanced GABA release and related internalization, subunits α2, α3, α5, β1, β3 and γ2 become significantly downregulated in granule cells of the dentate gyrus during or subsequent to a SE e.g. induced by injection of kainic acid, but significantly recover already after a few days.15,16 This may be the cause for the resistance to anticonvulsive treatment with benzodiazepines seen in some patients enduring a status epilepticus (SE).17 During the acute SE, also levels of δ-subunit mRNA and immunoreactivity (IR) significantly decline. These decreases, however, often persist for several months and are seen virtually in all epilepsy models.15,16,18–21 Also, α5 mRNA levels and IR were significantly decreased throughout all subfields of the hippocampus, including sectors CA1 and CA3, the subiculum, layers II and V/VI of the entorhinal cortex, and the perirhinal cortex in the same models.18,19,22 Downregulation of the δ-subunit is contrasted by marked and lasting increases in γ2 (after the acute SE).16,19,22,23 Also, an expression of subunit α4 is markedly increased in the granule cell layer after a SE induced by kainic acid, trimethyltin or sustained electrical stimulation, as well as after electrical kindling in the hippocampus.15,16,18–20,24 Six weeks after a pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus, also increased subunit α3-IR was seen in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus25 and in the same experiments α5-IR was increased in the granule cell but not in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus. And, after unilateral intrahippocampal injection of kainic acid, Bouilleret et al.26 observed increases in subunits α1, α3, α5 and γ2 IR in the dispersed granule cell/molecular layer compared to the contralateral area. This may indicate that the changes are not driven by seizures but related to granule cell dispersion.

Since δ- and α5-subunit containing receptors mediate tonic inhibition by GABA, it was suggested that the loss in these receptors may also reflect a loss in tonic inhibition in epileptic animals.21,22 A subsequent detailed study using immunogold labelling combined with whole cell electrophysiology by the same group, however, demonstrated that subunit γ2-IR is partially translocated from the centre of the synapse to a more perisynaptic area of granule cell dendrites. Thus, in epileptic mice, γ2-containing receptors may not only mediate phasic inhibition at the synapse centre but may also partially compensate for the loss in δ-subunits at perisynaptic sites and participate in tonic inhibition.27

Using human tissue, Shumate et al.28 more than 20 years ago demonstrated that the potency of GABA to stimulate GABAA receptors was considerably higher in granule cells of temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) patients than in epileptic rats or their controls and that their sensitivity to zinc was increased both in TLE patients and epileptic rats.28 These findings strongly indicated increased expression of GABAA receptors in granule cells of TLE patients. The authors also suggested a possible shift from α1 containing receptors to receptors containing other α-subunits with a higher sensitivity to zinc than α1.28

In contrast to rodents, there are only limited studies on changes in individual GABAA receptor subunits in human epilepsies. In hippocampal tissue obtained at surgery from drug-resistant TLE patients changes in the expression of different subunits have been investigated by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization and were compared with post-mortem tissue. In addition to changes associated with Ammon’s horn sclerosis, Loup et al.29 found increased expression of subunits α1, α2, β2/3 and γ2 in the granule cell layer of patients with hippocampal sclerosis, but interestingly not in patients without hippocampal sclerosis, and we observed pronounced increases in the expression of α3 and of all three β-subunits in patients with and without hippocampal sclerosis. Stefanitis et al.30 recently presented a detailed immunohistochemical study, investigating subunits α1, α2, α3, α5, β2/3 and γ2 in seven nuclei of the amygdala and in the entorhinal cortex of patients with and without hippocampal sclerosis. They observed decreased expression for all these subunits in all nuclei investigated except for subunit γ2. The study revealed an increased number of γ2-positive dendrites in most amygdaloid nuclei, although labelling of the neuropil was often reduced.

In our present study, we focussed on the dentate gyrus of TLE patients with and without Ammon’s horn sclerosis and investigated possible changes in the expression of subunits α4, α5 and δ, subunits that in the rat mediate tonic inhibition of GABA. We collected hippocampal specimens from TLE patients at the epilepsy centres in Vienna and Innsbruck, conducted in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry and α5-specific receptor autoradiography for these subunits, and compared the results with those obtained in post-mortem tissue.

Materials and methods

Patients

Hippocampal tissues were obtained at surgery from drug resistant TLE patients. Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Boards of the Medical Faculties of the Universities of Vienna and Innsbruck according to the Helsinki Declaration, and informed consent was obtained from all patients providing specimens. Presurgical evaluation of TLE patients included detailed clinical examinations, prolonged video-electroencephalographic (video EEG) monitoring with scalp and sphenoidal electrodes and neuropsychological tests.31–33 Neuroimaging studies included high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and interictal single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) with [99mTc]hexamethyl-propyleneamine-oxim (HMPAO). In patients with normal MRI scans or divergent findings from these non-invasive studies, invasive electrophysiological recordings from chronically indwelling subdural grid electrodes were obtained. Based on an accurate localization of the seizure onset zone derived from these investigations, patients were referred to selective amygdalohippocampectomy, anteromedial temporal lobe resection or en bloc temporal lobe resection.

Surgical specimens were examined by routine pathology and were grouped into those with hippocampal sclerosis (n = 51) or without sclerosis (n = 22). Tissue with hippocampal sclerosis originated from patients with selectively damaged hippocampus as assessed by MRI and confirmed by the presence of distinct hippocampal sclerosis at the neuropathological examination. In these patients, seizures presumably arose from the medial temporal region. Patients without obvious Ammon's horn sclerosis were defined as ‘non sclerotic’. The mean age of patients with Ammon’s horn sclerosis was 38.4 ± 1.36 (range 17–61) years that of patients without sclerosis was 36.1 ± 2.86 (range 22–55) years. The mean duration of epilepsy was 22.9 ± 1.80 years (range 1–54) and 12.2 ± 1.85 (range 1–28) years in patients with and without hippocampal sclerosis, respectively. All patients were taking antiepileptic drugs in mono- or polytherapy. The majority of patients received a combination of two drugs (72.2%); 19.4% were on monotherapy and 8.3% of the patients were treated with three or four anticonvulsive drugs. The most frequent antiepileptic drugs applied were carbamazepine (45% of all drugs used), lamotrigine (10%), valproate (23%), clobazam (9.5%) and oxcarbazepine (7.2%). In Table 1, we show the distribution of age, gender, duration of epilepsy for patients included in the individual histochemical studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of specimens used for the individual histochemical approaches

| TLE patients | Number |

Age |

Duration of epilepsy |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | F | M | Mean ± SEM | (Range) | Mean ± SEM | (Range) | |

| In situ hybridization | |||||||

| TLE, lesional | 29 | 11 | 18 | 36.2 ± 1.92 | (17–56) | 24.1 ± 2.31 | (1–46) |

| TLE, non-lesional | 13 | 5 | 8 | 34.4 ± 4.03 | (4–53) | 13.8 ± 2.33 | (1–28) |

| Receptor autoradiography | |||||||

| TLE, lesional | 17 | 7 | 10 | 36.4 ± 2.93 | (17–56) | 21.1 ± 3.30 | (1–46) |

| TLE, non-lesional | 6 | 2 | 4 | 38.0 ± 5.72 | (8–53) | 16.2 ± 3.11 | (9–28) |

| Immunohistochemistry | |||||||

| TLE, lesional | 24 | 14 | 10 | 41.1 ± 1.94 | (23–61) | 23.8 ± 2.87 | (1–54) |

|

TLE, non-lesional |

3 |

2 |

1 |

38.3 ± 8.76 |

(22–52) |

11 ± 6.23 |

(1–23) |

| Post-mortem controls |

Number |

Age |

Post-mortem time |

||||

|

N |

F |

M |

Mean + SEM |

(Range) |

Mean + SEM |

(Range) |

|

| In situ hybridization | 28 | 9 | 19 | 49.9 ± 2.7 | (24–95) | 14.8 ± 1.15 | (5–24) |

| Receptor autoradiography | 23 | 7 | 16 | 51.4 ± 2.80 | (33–95) | 14.8 ± 1.26 | (5–24) |

| Immunohistochemistry | 12 | 1 | 11 | 54.7 ± 5.20 | (28–95) | 12.4 ± 0.97 | (8–20) |

| Post-mortem, died during SE | 4 | 3 | 1 | 72.0 ± 8.46 | (55–88) | 10.6 ± 1.48 | (6.5–13) |

F, female; M, male; N, total number of sample. Note that some specimens were used for in situ hybridization, receptor autoradiography and immunohistochemistry.

Post-mortem controls

For controls, 31 hippocampi were obtained at routine autopsy post-mortem from patients without known history of neurological or psychiatric disease. Each brain was studied by a neuropathologist to confirm the absence of a brain lesion. The mean age at autopsy was 48.9 ± 2.24 years (range 24–76) and the mean post-mortem time prior to fixation of the specimen was 13.2 h ± 01.00 h (range 5–24 h) (see Table 1 for specifications in individual experiments). Causes of death were pneumonia, lung cancer, pharynx cancer, larynx cancer, breast cancer, liver cancer, liver cirrhosis, melanoma, pulmonary embolism, cardiovascular arrest, leukaemia or renal failure. In addition, we obtained post-mortem hippocampal tissues from four patients without history of epilepsy that had died during or after a SE (mean age: 72.0; range: 55–85 years; the SE was associated with cardiac arrest, theophylline intoxication, lung edoema, lymphoma). These specimens were included for comparing effects of an acute SE with those of chronic epilepsy with recurrent seizures.

Sample preparation

Surgical specimens were rinsed in 50 mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at 4°C, photographed for documentation and sectioned perpendicularly to the hippocampal axis into 5 mm thick blocks. Those obtained from the hippocampal body (middle segment) were included in the study. At autopsy, the whole hippocampus was removed from the brain, placed in ice cold PBS and sectioned in the same way as surgical tissue in a cold room. Tissue blocks were either processed for immunocytochemistry or in situ hybridization by fixation in paraformaldehyde (PFA) or by immediate snap freezing, respectively. Some specimens were split for processing them in both ways. For immunohistochemistry, tissue blocks were immediately immersed in 4% PFA/PBS for 4–5 days followed by stepwise immersion in sucrose (concentrations ranging from 5% to 20%) over 2 days. Specimens fixed by this procedure and unfixed brain samples selected for in situ hybridization were immersed in −70°C cold isopentane for 3 min and then put in a freezer at −70°C. After allowing the isopentane to evaporate for 24 h, tissue samples were sealed in vials and kept at −70°C. Prior to immunohistochemistry, The PFA-fixed specimens were cut in a Zeiss Microtome (Microm HM500 OM Cryostat; Carl Zeiss, Vienna, Austria), 40 µm thick sections were collected and kept in PBS/0.1% sodium azide at 5°C for up to 2 weeks. For in situ hybridization, 20 µm thick sections were cut and mounted immediately on poly-lysine coated slides (Menzel-Gläser, Braunschweig, Germany) and stored at −20°C.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as described previously.16,32 We used the following oligo-DNA probes that were complementary to selected DNA sequences of the human prepro-mRNAs: for subunit α4 the oligo-DNA probe was complementary to bases 6086–6129 (gene bank accession number NM_001204266.2, CCAACATCAACAACTCTCACTTCCCTGCATTCACCCTTACCTCC, 44 bases), that for subunit α5 to bases 462–508 (gene bank accession number: XM_017022056.1, CGAAGTCTGTTGTCGTAGCCATCCAAGAGCCCATCCAAGATCCTGGT, 47 bases), that for the δ-subunit was complementary to bases 3740–3742 (gene bank accession number: XM_011541194.3; CCCACCTCCTCCCACGCTCTGATCCCGATCCTGCAGAGC, 39 bases) and for β-actin we used an oligonucleotide complementary to bases 1464–1501 (gene bank accession number: NM_001101.5; GGC AAG GGA CTT CCT GTA ACA ACG CAT CTC ATA TTT GG, 38 bases) of the respective prepro-mRNA sequences.

The probes were custom synthesized (Microsynth, Balgach, Switzerland) and labelled on their 3′ end with [35S]α-thio-deoxyadenosine 5′ triphosphate (1300 Ci/mmol; New England Nuclear, Wilmington, Germany) by reaction with terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) as described in detail previously.16,32 For in situ hybridization of β-actin mRNA, we used [α-33P]deoxyadenosine 5′ triphosphate (3000 Ci/mmol; SCF-203H; Hartmann Analytic, Braunschweig, Germany) applying the same procedure for DNA labelling.

Frozen sections from controls (n = 29), sclerotic (n = 29) and non-sclerotic (n = 14) specimens, and specimens from non-epilepsy patients who died after a SE (n = 4) were rapidly immersed into ice cold 2% PFA, PBS for 10 min, rinsed in PBS, transferred to 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 M triethylamine hydrochloride for 10 min (room temperature), dehydrated by ethanol series and delipidated with chloroform. They were then hybridized in 50 µl hybridization buffer, containing about 50 fmol (0.8–1 × 106 cpm) labelled oligonucleotide probe at 42°C for 18 h. The hybridization buffer consisted of 50% formamide, 4 × SSC (1 × SSC is 150 mM NaCl, 15 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.2), 500 µg/ml salmon sperm DNA, 250 µg/ml yeast tRNA, 1 × Denhardt's solution (0.02% ficoll, 0.02% polyvinylpyrolidone and 0.02% bovine serum albumin), 10% dextran sulphate, and 20 mM dithiothreitol (all from Sigma, Munich, Germany). At the end of the incubation, we rinsed the slides twice in 1 × SSC, 50% formamide (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). They were then washed four times in 50% formamide in 1 × SSC (42°C, 15 min) and briefly rinsed in 1 × SSC followed by water. We then dipped the sections in 70% ethanol, dried them and exposed them to BioMax MR films (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK), for 7–14 days and then developed the films with a Kodak D19 developer. The sections were then counter stained with cresyl violet, dehydrated, cleared in butyl acetate and cover slipped with Eukitt (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Control experiments were performed using the respective sense probes.

Receptor autoradiography

We used the α5-specific inverse GABAA agonist [3H]L-655,708 as ligand for specifically labelling α5-containing GABAA receptors in our specimens34 and examined the same slice-mounted tissue sections (20 µm, kept at −20°C) as used for in situ hybridization (n = 24 controls, 19 with and eight without hippocampal sclerosis, two post-mortem with SE). We washed the sections four times in fresh ice-cold 10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4 (Tris/EDTA) buffer for 30 min and then incubated them in Tris/EDTA containing 2 nM methoxyl [3H]L-655,708 (Amersham. Buckinghamshire, Great Britain, catalog number: 708N) and 10 µM zolpidem (Tocris, catalog number: 0655) to inhibit low affinity binding to other α-subunit containing receptors at 4°C for 2 h. Non-specific binding was assessed by incubating the sections with the same solution containing 10 µM flunitrazepam. Labelled sections were rinsed twice in Tris/EDTA for one min, dipped in distilled water, dried in cold air and then exposed together with [14C] micro-scales (Amersham International, Amersham, UK) to Hyperfilm-B (RMN 9 Bmax 1562545) films (Amersham International, Amersham, UK) for 10 weeks. The films were developed with Kodak D-19 developer (16%) for 1 min, briefly rinsed in water and subsequently fixed for three min. The films were then digitalized using a Canon 9000 Mark II scanner.

Immunohistochemistry

Antibodies

The antibodies were originally raised to fusion proteins derived from DNA constructs of the maltose binding protein gene with specific rat sequences of α4- and δ-subunits and transcribed in Escherichiacoli, and to an α5-subunit specific peptide coupled to keyhole-limpet haemocyanin.35 They were first characterized in the rat brain35 and then further characterized in the monkey brain by using synthetic peptides corresponding to human/macaque sequences of α5 and δ subunits for displacing antibody binding.36

We performed incubations on 40 µm free-floating sections obtained from PFA-fixed hippocampal specimens from TLE specimens with hippocampal sclerosis and from post-mortem controls. The sections were first incubated in 0.6% H2O2, 20% methanol in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffered saline pH 7.2 (TBS) for 20 min to reduce endogenous peroxidase activity and then treated with target retrieval solution (pH 6.0 and pH 10; Dako, Vienna, Austria, 70°C, 20 min). We then incubated the sections in 10% normal goat serum (GIBCO #16210-072, obtained through Fisher Scientific, Vienna, Austria) in TBS/0.2% Triton X100 and 0.1% sodium azide for 90 min and subsequently with the respective primary antiserum at dilutions of 1:100 (α4 and α5) or 1:200 (δ) at 4°C for 48–72 h. The sections were then processed by the Vectastain ABC standard procedure using 1:200 dilutions of Vectastain PK4001 goat biotinylated anti-rabbit antibody (Vector Laboratories Cat# PK-4001, obtained through Szabo-Scandic, Vienna, Austria). Incubations with the biotinylated secondary antibodies and subsequent incubations with the ABC reagent (a mixture of avidin–biotin–horseradish peroxidase complex; 1:100) were done at room temperature for 60 min. The resulting complex was labelled by reacting the peroxidase with 0.05% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma, Munich, Germany) and 0.005% H2O2 (30%, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in TBS for 4 min. After each incubation step (except pre-incubation with 10% blocking serum), three 5 min washes with TBS were included. All buffers and antibody dilutions, except those for washing after target retrieval solution and peroxidase treatment, and the reaction with diaminobenzidine, contained 0.2% Triton X-100. We included normal horse or goat serum (10%) in all antibody-containing buffers. The sections were finally mounted on glass slides, air-dried, dehydrated, and cover-slipped (VWR International, Vienna, Austria). No labelling was observed when the primary antisera were omitted. For light microscopy a Zeiss Axiscope 5 microscope equipped with an Axiocam 105 digital camera (Carl Zeiss, Vienna, Austria) was used. Digital images were obtained by a Openlab 5.5.0 Imaging Software, Improvision, Coventry, UK.

Nissl stains were performed as described previously.37

Densitometric analyses

Analysis of mRNA expression, receptor binding, immunohistochemistry and of Nissl stains

Autoradiographic films were digitized and opened in NIH ImageJ (version 1.46; U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, ML, USA; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). In situ hybridization signals for subunit α4 and δ mRNAs, and that of Nissl stains were quantified in the granule cell layer and those for α5 mRNA in sectors CA1 and CA3 and in the subiculum (in addition to the granule cell layer). Evaluation of α5-specific receptor binding was done in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus using films from [3H]L-655,708 receptor autoradiographs. For evaluating the dentate granule cell layer, line selections (20 pixels width) were drawn perpendicular to the layer of interest and a density profile plot (grey values) was created using the function ‘Analyze—Plot profile’. All other areas including the molecular layer for evaluating α5-specific receptor autoradiographs were evaluated in the same way using circular selections. For evaluating immunohistochemical labelling digitalized immunohistochemical images were used and circular selections of the dentate molecular layer were quantified. Background measures were done adjacent to the brain section. Values for relative optical densities (RODs) were calculated from grey values according to the following formula: ROD = log[256/(255—gray value)]. In the dentate gyrus, ROD values were obtained from two to three different measures obtained at a distance of about one-third of the entire granule cell/molecular layer blade to its borders and from its middle part. In the other hippocampal subfields measures were taken randomly at sites with equal distance from each other and the borders of the area. Background ROD values were obtained at the site of the respective section with lowest densities. ROD values were averaged and the background ROD value was subtracted.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as of % controls (mean ± SEM). Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 5.0a for Macintosh (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and Microsoft Excel data analysis software. Gaussian distribution was assessed for all groups by the d’Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test using the GraphPad Software. When two groups were compared an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was applied depending whether a Gaussian distribution was observed, assuming P < 0.05 as statistically significant. When more than two groups were compared, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was done. The alpha level was set at P < 0.05 for multiple comparisons and a Dunnett’s multiple comparison post hoc test was performed for determining between-group differences among multiple sets of data and controls. F-values and degrees of freedom (df) are presented. For assessing correlations between age and ROD values and post-mortem times (PMT) and RODs, the Pearson correlation factor (r) and respective P-values were determined using the GraphPad Software.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Characteristics of epilepsy specimens

Table 1 shows a summary of the clinical data of the patients included in the different histochemical procedures. In agreement with our previous studies.31,32 and those of many others,38,39 we observed in most cases with Ammon’s horn sclerosis pronounced cell losses in the hilus of the dentate gyrus, sectors CA1 and CA3, accompanied by less severe in the granule cell layer, sector CA2 and in the subiculum. Owing to the surgical procedure, only small parts of the CA1 sector were preserved in most TLE tissue specimens. In nineteen patients with hippocampal sclerosis dispersion of granule cells was observed.40 In these patients, the granule cell layer was broader than in other TLE patients or controls. In four of these specimens, it was bilaminar. None of the post-mortem controls or non-sclerotic specimens showed comparable dispersions of granule cells. We assessed cell losses in the granule cell layer by determining ROD values of the granule cell layer of Nissl-stained sections and observed reductions by 45.6 ± 3.50% (n = 16; P < 0.0001 in ANOVA with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison test) and 14.3 ± 8.89% (n = 8, not significant) in specimens with and without Ammon’s horn sclerosis, respectively. These estimates were in striking agreement with previously performed cell counts in our TLE specimens revealing losses in granule cells by 55 ± 2.0% and 10 ± 4.1% in sclerotic and non-sclerotic specimens, respectively.37

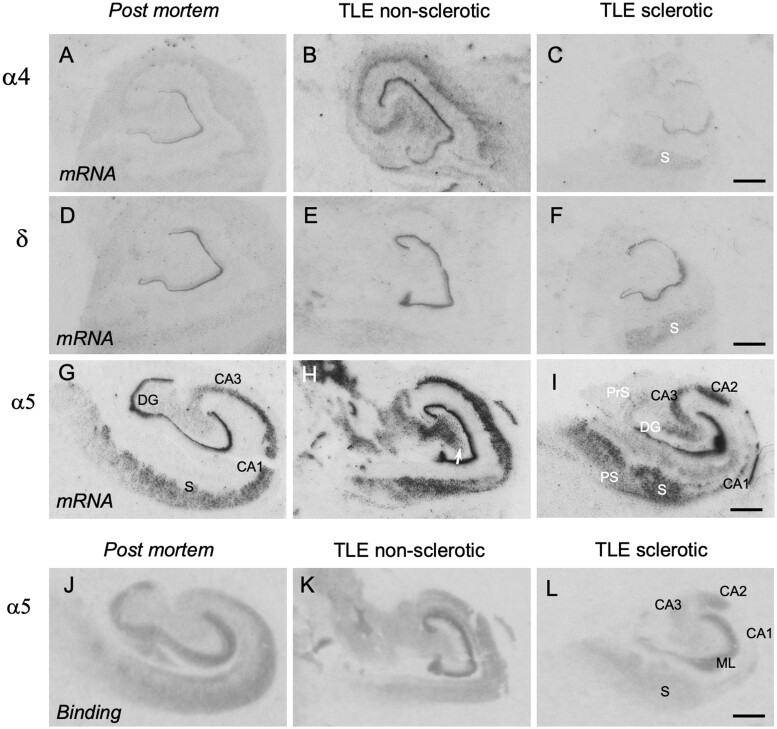

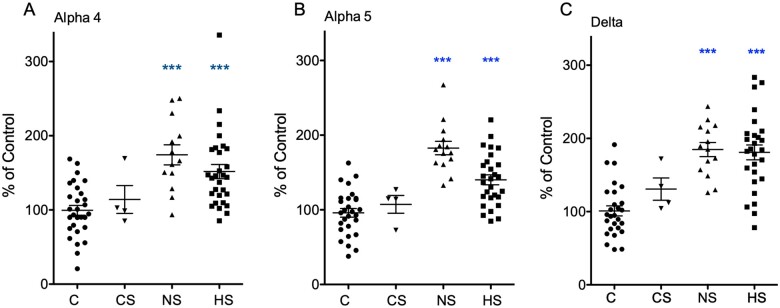

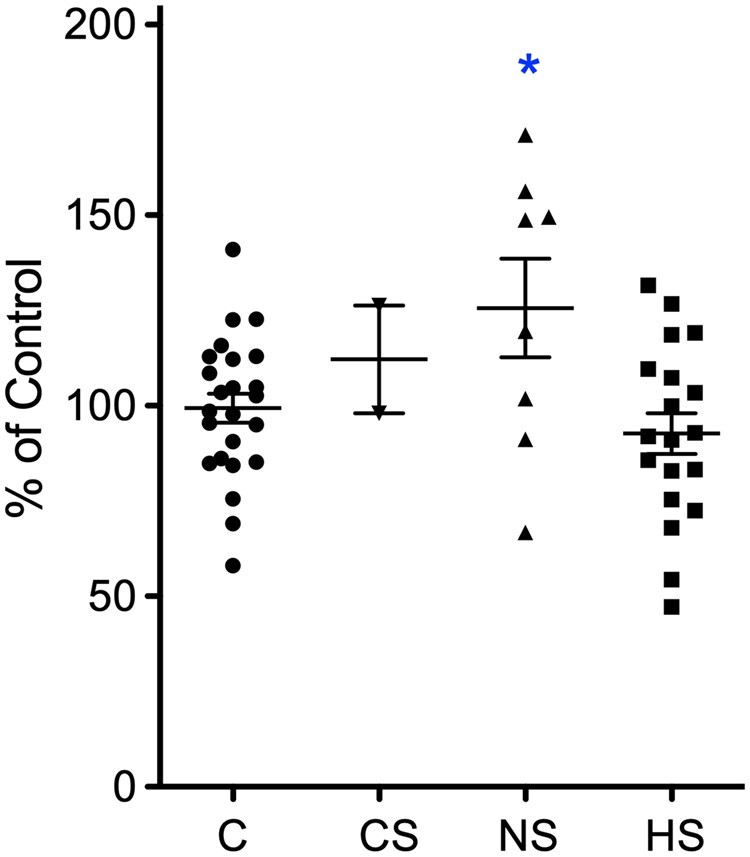

In situ hybridization of GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs

Figure 1 shows photomicrographs from autoradiograms after in situ hybridization for subunits α4, α5 and δ. Quantitative assessments for the granule cell layer are shown in Fig. 2, and in Table 2 data on α5 mRNA expression in other subfields of the hippocampus. In post-mortem controls, we observed weak signals for α4, and δ-subunit mRNAs (Fig. 1A and D), but considerably stronger and significantly more abundant ones for α5 (Fig. 1G). All three subunits were unambiguously expressed in the dentate granule cell layer. Signals for α4 and δ were faint in the pyramidal cell layers and in the subiculum. In contrast, besides the dentate granule cells there was high expression of α5 mRNA in the pyramidal cell layers of CA1 to CA3, in the subiculum and in the pre- and parasubiculum (Fig. 1G). One-way ANOVA revealed statistically significant differences in the expression of all three subunit mRNAs in TLE patients compared with post-mortem controls: α4, F(2,68) = 15.9094, P = 2.148E-06; α5, F(2,69) = 33.8106, P = 5.82E-11; δ, F(2,65) = 28.6391, P = 1.205E-9. Using the Dunnett’s post hoc analysis, there were statistically significant increases in mRNA expression both in patients with (mean % of control ± SEM): α4: 151.7 ± 9.55 (n = 29); α5: 140.1 ± 6.65 (n = 28) and δ: 180.9 ± 10.10 (n = 27); P < 0.001 for all three subunit mRNAs) and without Ammon’s horn sclerosis (mean % of control ± SEM): α4: 174.3 ± 13.54 (n = 13); α5: 182.7 ± 8.98 (n = 14) and δ: 184.8 ± 9.62 (n = 14); P < 0.001 for all three subunit mRNAs compared with post-mortem controls (n = 29, 30 and 27 for α4, α5 and δ, respectively) (Fig. 2). Subunit mRNAs were not significantly altered in specimens obtained from patients who died after or during a SE (mean % of control ± SEM: α4: 85.1 ± 18.83; α5: 107.3 ± 11.89 and δ: 130.8 ± 15.28; n = 4, P < 0.05 for all three subunit mRNAs).

Figure 1.

GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs and α5 receptor autoradiography in TLE patients. Autoradiograms after in situ hybridization subunit α4 (A, B), δ (D, E) and α5 (G, H) mRNAs and receptor autoradiography for α5-containing receptors (J, K). Shown are images of the hippocampus of autopsy controls and for non-sclerotic and sclerotic TLE specimens as indicated on top of the figure. Note the pronounced expression of α5 mRNA throughout all hippocampal subfields. It correlates well with the receptor autoradiography using the α5-specific ligand [3H]L-655,708. DG, dentate gyrus (granule cell layer); PrS, presubiculum; PS, parasubiculum; S, subiculum. Scale bars in C, F, I and L for all images: 200 µm.

Figure 2.

Change GABAA receptor subunit mRNA levels in TLE patients. Shown is a quantitative assessment of in situ hybridization data for α4 (A), α5 (B) and δ (C) mRNAs in the granule cell layer of C, post-mortem controls; CS, post-mortem specimens of patients that died after status epilepticus; NS, non-sclerotic specimens; and HS, specimens with hippocampal sclerosis. The data show ROD values and are presented as % of mean ROD of controls. Statistical significance (one-way ANOVA, with Dunnett’s multiple comparison post hoc test): ***P < 0.001.

Table 2.

Changes in subunit α5 mRNA expression in subfields of the hippocampus of TLE patients without Ammon’s horn sclerosis

| Control |

TLE |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ROD (% of control ± SEM) | |||

| Granule cells | 100.0 ± 5.69 (30) | 187.3 ± 9.20 (14) | P = 3.68 10−8 |

| CA3 | 100.0 ± 11.55 (9) | 186.6 ± 33.31 (9) | P = 0.025 |

| CA1 | 100.0 ± 9.46 (9) | 190.2 ± 22.16 (9) | P = 0.007 |

| Subiculum | 100.0 ± 11.46 (9) | 170.7 ± 18.45 (9) | P = 0.005 |

Due to the variable neurodegeneration in specimens with Ammon’s horn sclerosis only non-sclerotic samples were used for the analysis of hippocampal subfields. The data show ROD values expressed as mean of controls ± SEM. Autoradiographs obtained after in situ hybridization of the respective mRNAs were done by ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). For statistical analysis, the two-tailed Student's t-test was applied.

In addition to the enhanced expression in the granule cell layer, α5 mRNA levels were markedly increased throughout all subfields of the hippocampus in non-sclerotic specimens (Figs 1H and 2B, Table 2), including sectors CA1 to CA3 and the subiculum. In specimens with Ammon’s horn sclerosis, markedly increased expression of the α5 subunit in the granule cell layer and in the subiculum was observed. The increase in α5 subunit was weaker in sector CA3 and the pre- and parasubiculum in sclerotic than in non-sclerotic specimens and, due to extensive neurodegeneration, absent in sector CA1 (Fig. 1I). Faint labelling, presumably of interneurons was observed in the hilus of the dentate gyrus of controls (Fig. 1G). This labelling was significantly enhanced in the non-sclerotic samples, and virtually absent in the sclerotic specimens, presumably reflecting the degeneration of hilar interneurons (Fig. 1H and I).

We also investigated β-actin mRNA as a housekeeping gene. β-actin mRNA was expressed throughout the pyramidal layers CA1 to CA3 of the hippocampus including the subiculum and parasubiculum and was somewhat less prominent in the granule cell layer and the hilus of the dentate gyrus (Supplementary Fig. 1). This distribution was consistent with that observed by Ohnuma et al.41 in brains of Schizophrenia patients. In patients with hippocampal sclerosis less mRNA expression was observed throughout the hippocampus and, due to neurodegeneration, was virtually absent in sector CA1. Expression of β-actin mRNA was, however, unchanged in non-sclerotic specimens compared with controls (Supplementary Fig. 1).

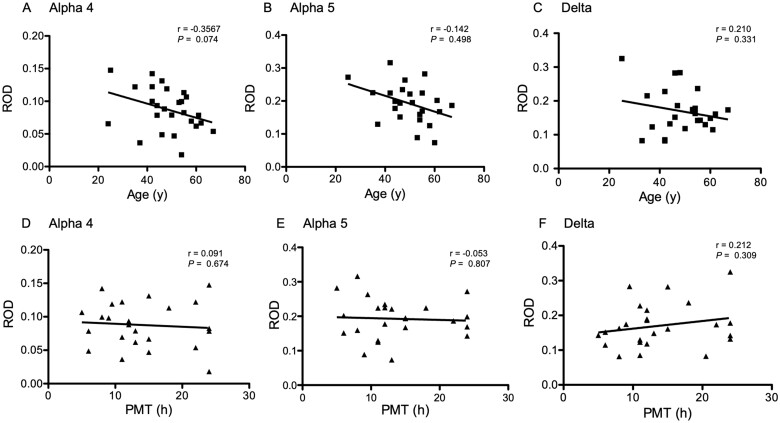

Analysis of correlation of in situ hybridization data with age and post-mortem time of control specimens

The mean age of the controls at death (48.6 ± 2.17; n = 30) was significantly (P < 0.0001) higher than the mean age of the patients at surgery (34.8 ± 1.61; n = 41). To investigate a possible bias by the higher age and also of potential degradation of mRNAs during prolonged PMT of our control specimens, we investigated for possible correlations between the patients’ age at death and measured ROD values, and of the mean time between death and dissection with RODs. These data are shown in Fig. 3. Whereas there was no correlation between PMT and ROD values obtained in in situ hybridization autoradiographs (Fig. 3D and E; Pearson’s correlation r = 0.03 to 0.21 for the different subunit mRNAs), we observed a statistically non-significant tendency (P-values 0.31 to 0.67) for correlations between the detected mRNA levels of all three GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the granule cell layer and the patients’ age at death (Fig. 3A–C; Pearson’s correlation r = 0.14–0.36). To further assess the possible dependence of the in situ hybridization signals and the age at death, we re-evaluated our analysis of mRNA levels in hippocampal samples after excluding autopsy samples obtained above an age of 49. The mean age of the resulting group of controls was 39.13 ± 1.94 years (n = 16). Also when compared to this adjusted control group (n = 13–16), the mRNA levels of all three receptor subunits were still significantly higher in TLE specimens (α4: P = 6.41E-04, df = 2,52; α5: 3.36E-07, df = 2,52; δ: 1.32E-04, df = 2,50): sclerotic specimens (mean % of control ± SEM, n = 27–29): α4: 145.1 ± 9.13, P < 0.05 (Dunnett’s posthoc test), α5: 136.6 ± 8.59, P < 0.01 and δ: 156.9 ± 12.19%, P < 0.05, as well as in non-sclerotic specimens (mean % of control ± SEM, n = 13–14): α4: 166.7 ± 12.94, P < 0.01 (Dunnett’s posthoc test), α5: 179.5 ± 8.38, P < 0.001 and δ: 163.8 ± 9.01, P < 0.01. This analysis indicates that neither PMT nor the age of controls significantly influenced the outcome of subunit mRNA levels.

Figure 3.

Correlation of age and post-mortem times with mRNA levels in autopsy controls. (A–C) Correlation of age, (D–F) correlation of PMT with mRNA levels in autopsy controls. Shown are ROD values obtained in receptor autoradiographs. Note that mRNA levels of all three subunits show a tendency for a correlation with age, which, however was statistically not significant (see Pearson’s correlation coefficients r, and P-values). There was no correlation of mRNA levels with PMT.

Subunit α5-specific receptor autoradiography

To characterize expression of the α5-subunit containing receptors, we performed receptor autoradiographs for the α5-specific inverse agonist GABAA agonist [3H]L-655,708 (Figs 1J and K and 4). In post-mortem controls, specific labelling was observed in the molecular layer of dentate gyrus, throughout the pyramidal layer and in the subicular complex (Fig. 1J). This distribution correlated well with the distribution observed by in situ hybridization and by immunohistochemistry. Using one-way ANOVA for evaluating ROD values in the molecular layer, a statistically significant difference between [3H]L-655,708 binding in controls, and sclerotic and non-sclerotic TLE specimens was seen [F(2,48) = 5.5176, P = 0.0069]. Using Dunnett’s post hoc analysis, there were statistically significant increases in the binding in the molecular layer of non-sclerotic specimens (mean 125.6 ± 12.39% of control, P < 0.05) but (presumably due to loss of granule cells) not in the sclerotic TLE samples (mean 92.7 ± 5.35% of control) (Figs 1K and 4).

Figure 4.

Change in α5-specific receptor binding TLE patients. Shown is a quantitative assessment of receptor autoradiographs of the granule cell layer using the α5-specific ligand [3H]L-655,708. C, post-mortem controls; CS, post-mortem specimens of patients that died after SE; NS, non-sclerotic specimens; and HS, specimens with hippocampal sclerosis. The data points represent ROD values and are presented as % of mean ROD of controls. Statistical significance (one-way ANOVA, with Dunnett’s multiple comparison post hoc test): *P < 0.05.

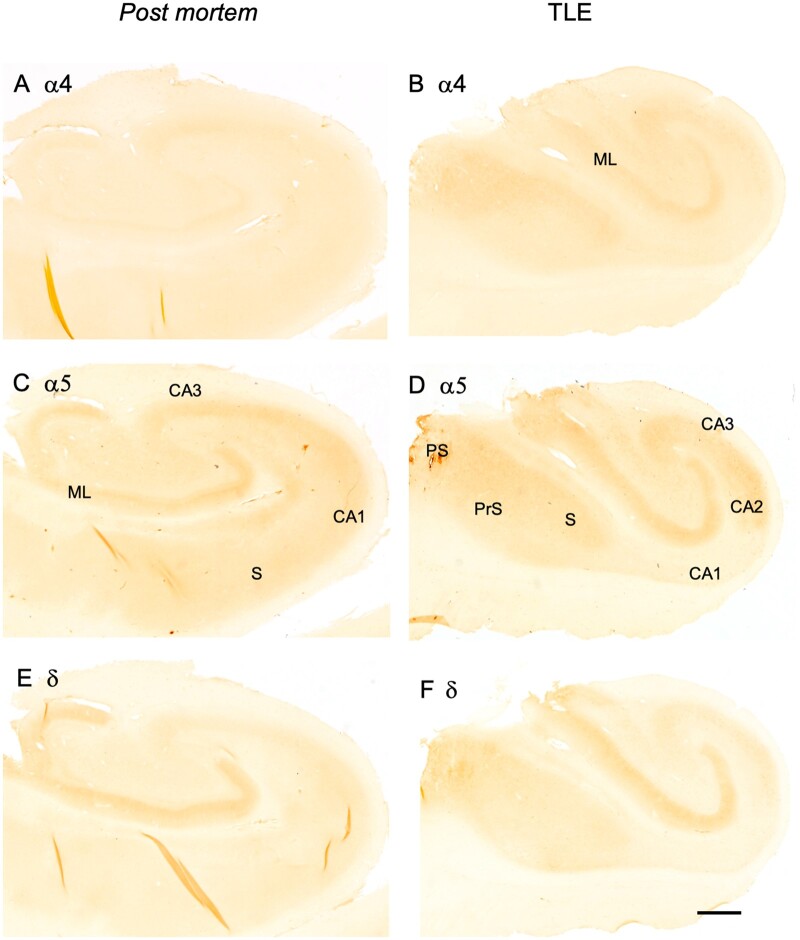

Immunohistochemistry

In post-mortem controls, α4-IR was faint or not detectable throughout the hippocampus (Fig. 5A). In the sclerotic TLE specimen, we detected α4-IR in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus, in sector CA3, in the subiculum and parasubiculum (Fig. 5B). Consistent with our observation in the brains of macaques,36 α5-IR seemed to be considerably more abundant than that for α4 and δ. It was strong in the dentate molecular layer, sector CA3 and weaker in sector CA1 and in the subiculum (Fig. 5C). In the hippocampus from TLE patients with sclerosis, we observed rather strong α5-IR in the dentate molecular layer, in sector CA3, in the subiculum and in the pre- and parasubiculum (Fig. 5D). In contrast, subunit δ-IR was only detectable in the molecular layer of post-mortem controls. In the tissues from TLE patients (with hippocampal sclerosis), δ-IR was enhanced in the subicular complex (subiculum and presubiculum), in addition to faint labelling in sectors CA3 and CA2 (Fig. 5F). Using the ImageJ program, we observed statistically significant increase in ROD values in the dentate molecular layer of TLE patients with Ammons’ horn sclerosis compared to post-mortem controls for all three subunit IR [as % of controls ± SEM (n): α4, control 100.0 ± 18.28 (8), TLE 189.1 ± 14.82 (8), P = 0.0023, df = 14; α5, control 99.9 ± 7.40 (18), TLE 135.6 ± 4.81 (24), P = 0.00034, df = 40] and δ control 100.0 ± 8.51 (13), 148.1 ± 5.35 (16), P < 0.0001, df = 27. Data followed a Gaussian distribution in all groups except for controls of δ subunit.

Figure 5.

Change in GABAA receptor subunit immunoreactivities in TLE patients without Ammon’s horn sclerosis. Immunoreactivities for subunits α4 (A, B), α5 (C, D) and δ (E, F) are shown for post-mortem controls (A, C, E) and patients without Ammon’s horn sclerosis (B, D, F). RODs of immunoreactivities were quantified in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus of sclerotic specimens using the NIH ImageJ program. Significant increases were observed for all three subunit IR, as % of controls ± SEM (n): α4, control 100.0 ± 18.28 (8), TLE 189.1 ± 14.82 (8), P = 0.0023, df = 14; α5, control 99.9 ± 7.40 (18), TLE 135.6 ± 4.81 (24), P = 0.00034, df = 40) and δ control 100.0 ± 8.51 (13), 148.1 ± 5.35 (16), P < 0.0001, df = 21. Data followed a Gaussian distribution in all groups except for controls of δ subunit. Scale bar in F for all images: 250 µm.

Discussion

This study revealed three major results:

1. The expression of GABAA receptor subunit α5 is highly abundant in the granule cell and molecular layers of the dentate gyrus. Whereas in the rat it is mainly restricted to the hippocampal sectors CA1 and CA3, the subiculum and entorhinal cortex,18,35 we observed in humans also high concentrations of the subunit in granule cell/molecular layer of the dentate gyrus. Since the α5 subunit mediates tonic inhibition, this may have important functional consequences on the dentate gyrus that is gating excitatory input from the entorhinal cortex.

2. In contrast to a profound downregulation of subunits α5 and δ in most hippocampal and para-hippocampal areas in rodent models of TLE, we observed profound upregulation of both subunits in the dentate granule cell layer and for α5 also throughout the hippocampal formation of TLE patients. Consistent with the data from rodent epilepsy models, expression of the α4-subunit was also increased in the dentate gyrus of TLE patients.

3. In post-mortem specimens from patients who died after a SE, we observed no changes in the expression of α4 and α5 subunits, in spite of a modest (statistically not significant) increase in expression of δ (Fig. 2). Although the sample of these patients was small, the observation indicates that upregulation of GABAA receptor subunits may require more sustained and recurrent stimulation by epileptic seizures.

Our data are based on in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry and receptor autoradiography (for subunit α5), thus characterizing the expression of the receptor subunits on mRNA and protein level. The regional distribution of the subunits and changes in their expression are consistent for all three methods. In situ hybridization with radiolabeled oligonucleotide probes allows quantitative assessment of the signal. A draw-back of our histochemical studies may, however, be instability of mRNAs and proteins especially in the autopsy specimens often originating from older patients than the TLE specimens and by possible degradation of mRNA during the time between death and dissection of the brains. We therefore tested our in situ hybridization data for these variables. Although we observed statistically not-significant, age-dependent decreases in mRNAs levels of all three subunits, we detected no statistically significant (negative) correlation between PMT and in situ hybridization signals. Furthermore, we re-examined our data set after excluding post-mortem controls with age of 50 years and higher. This evaluation confirmed our results revealing also significantly increased expression of all three mRNAs in TLE patients when compared to controls of equal age.

Our data, however, could be also confounded by variable cell losses in TLE patients. Thus, in sclerotic TLE specimens about 46% were lost, whereas cell loss was minimal in non-sclerotic specimens (about 16%). We decided not to correct our mRNA data for these cell losses, since they would (perhaps artificially) further exaggerate the observed increases in subunit expression. On the other hand, the failure of a significant increase in [3H]L-655,708 binding in the dentate molecular layer of sclerotic specimens could be due to the loss in granule cells in these sections.

Furthermore, molecular parameters associated with neurotransmission are often increased in their expression and may lead to the apprehension that recurrent seizures cause general unspecific overexpression of these components. Thus, opposite to respective animal models, in human TLE most GABAA and GABAB receptor subunits become upregulated. On the other hand, expression of subunit α1 is decreased both in animal models and in human TLE.29 Also expression of some neuropeptides is not uniformly increased. For example, neuropeptide Y expression is not significantly altered in granule cells/mossy fibres of TLE patients although it is prominently upregulated in respective TLE animal models.42 Furthermore, immunoreactivities of the neuropeptides secretoneurin and chromogranin A are not significantly altered while levels of chromogranin B and dynorphin are drastically increased in granule cells/mossy fibres of TLE patients.31,43 Therefore, in spite of the fact that epilepsy may put a high unspecific drive upon the expression GABAA receptor subunits, this expression is to some extent also diverse. And, concomitant overexpression of different GABAA receptor subunits may also be purposive for establishing formation of functioning receptors. Furthermore, expression of β-actin mRNA was not increased in TLE specimens compared to controls.

The histochemical data on the increased expression of the α5-subunit in TLE patients is in striking accordance with a recent elegant PET study by.44 The authors investigated the uptake of [11C]Ro15-4513, a partial inverse benzodiazepine agonist for α5 subunit-containing GABAA receptors in MRI-negative (non-lesional) TLE patients and non-epilepsy controls. [11C]Ro15-4513 binds to α1-, α2-, α3- and to α5-containing receptors. Using voxel-by-voxel bandpass spectral analyses, they were able to separate slow and high frequency signals (VS and VF, respectively). These signals differentiate between α1-, α2-, α3-subunit-containing receptors (VF) and α5-containing receptors (VS).45 Strikingly, the α5-selective component of the signal was increased in the hippocampus, temporal lobe, anterior cingulate gyri and the piriform cortex (area tempestas) of TLE patients, whereas VF:VS ratios corresponding to α1-, α2- and α3-containing receptors were reduced compared to those in healthy controls, suggesting a possible downregulation of receptors containing the respective α-subunits. The later finding corresponds to the previously observed loss in [11C]flumazenil binding (presumably preferring α1, α2, α3 opposed to α5 containing receptors) close to the seizure focus which correlated with increased ictal activity.46,47 Taken together, these data indicate a loss in subunits α1, α2 or α3 in the seizure focus, whereas receptors containing α5 are upregulated. McGinnity et al.44 therefore interpreted their data as a shift from α1-, α2- or α3- to α5-containing receptors.

Besides overexpression of α5-subunits in the hippocampus of TLE patients, there is also previous evidence for similar changes in the expression of subunits α4 and δ in brains of epilepsy patients. Thus, Joshi et al.48 recently investigated subunit α4 expression in cortical tissue obtained at surgery from children with focal cortical dysplasia II, tuberous sclerosis or ganglioglioma associated epilepsies and performed voltage-clamp measurements in xenopus oocytes injected with membranes obtained from these cortical samples. Using Western blotting, the authors observed increased expression of the α4-subunit (interestingly colocalizing with γ2) compared to post-mortem controls. Potentiation of GABA-evoked currents by the neurosteroid allopregnanolol was, however, reduced. On the other hand, they found significant potentiation of GABA currents by the imidazobenzodiazepine Ro15-4513, which acts on α4βδ containing receptors in membranes obtained from patients but not of controls, again supporting the expression of α4/δ-containing receptors in the cortex of epilepsy patients. These findings are in perfect agreement with earlier findings by Scimemi et al.49 reporting a tonic current that is modulated by neurosteroids in granule cells of TLE patients and thus likely mediated by α4/δ containing receptors.

It is interesting to note that, in contrast to rodents, in the epileptic human brain, also α5 and δ are upregulated besides α4. Increased expression of subunits α4, α5 and δ mediating tonic inhibition goes in hand with upregulation of β-subunits, α2 and γ2, but not α1 or α3 in the granule cell/molecular layer of the dentate gyrus.29,32 This opens the possibility, that in addition to an almost general overexpression of receptor subunits, also partial reorganization of GABAA receptors to functioning receptors may take place in granule cells, constituting of receptors containing α4 and/or α5, one of the major β-subunits β2 or β3 and δ or γ2. All these possible combinations can facilitate tonic inhibition. In spite of the fact that some interneurons are lost in TLE, both animal and human studies show compensatory increases in GABA-ergic transmission in surviving interneurons.50–54 GABA even released from distant sites then can act upon high affinity GABAA receptors responding already at low GABA concentrations with tonic inhibition.55 On the other hand, GABAA receptors mediating phasic inhibition (containing α1, α2, βx and γ2) by GABA released within the synapse may in part become deprived from their presynaptic innervation due to loss of interneurons.

It is worth to emphasize that the PET study by McGinnity et al.44 and our histochemical data demonstrate an abundant expression of α5-containing GABAA receptors in the human hippocampus including the dentate gyrus. In rodents, α5-containing GABAA receptors, although abundant on dendrites of pyramidal neurons of hippocampal sector CA3, the subiculum and the entorhinal cortex, are expressed only at low concentrations in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus.18,36,37 In rodents stimulation of α5-containing receptors in sector CA1 impairs the performance in hippocampus-dependent learning and memory tests56,57 and the reverse α5-specific GABAA agonist PWZ-029 improves the performance of rats in the object recognition test.58 In their PET study, McGinnity et al.44 showed a negative correlation between α5-selective binding and the performance in a cognitive test battery also in human controls and MRI negative TLE patients.44 Interestingly, the α5-selective PET signal VS was, however, negatively correlated with interictal intervals reflecting an association of increased [11C]Ro15-4513 uptake with decreased seizure activity and points to a possible anticonvulsive action mediated by α5-containing receptors. Respective receptors located on granule cell dendrites could importantly contribute to such a mechanism. GABAA receptors overexpressing the α5-subunit on granule cell dendrites may substantially contribute to such an anticonvulsive action. α5-receptor agonists may therefore specifically augment tonic inhibition by GABA on granule cell receptors. A clinical use of such compounds, however, may be obstructed by possible negative effects on cognition mediated by α5-containing receptors in CA1 and CA3.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our present study demonstrates that α5-containing GABAA receptors, in contrast to the rat, are highly expressed also in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus and that their expression is significantly upregulated throughout the hippocampus in (lesional and non-lesional) TLE patients. We also show increased expression of α4 and δ in the dentate gyrus, which coincides with increased expression of all three β-subunits,32 ultimately allowing the assembly of α5βδ or α4βδ receptors, or of receptors containing γ2 instead of δ. Extra-synaptic GABAA receptors (containing α4, α5 and/or δ) exert high affinity to their transmitter and therefore can respond well to volume transmission.4,6,8,9 They may sense even low concentrations of GABA spilled-over during seizures, from even distant sites and support tonic inhibition at the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus and in other parts of the hippocampal formation. Increased expression of GABAA subunits mediating tonic inhibition, thus, may be part of an endogenous anticonvulsive mechanism contributing to inhibition or cessation of acute seizures.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain Communications online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Karoline Fuchs and Werner Sieghart, Brain Research Center, Medical University Vienna for supplying the antibodies for the GABAA receptor subunits and Anne Bukovac for characterization in the monkey and human brain.

Funding

The work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (Projects P 19464, P 26680).

Competing interest

The authors report no competing interests.

Glossary

- AS=

Ammon’s horn sclerosis

- NS=

non-sclerotic

- SE=

status epilepticus

- TLE=

temporal lobe epilepsy

References

- 1. Chuang SH, Reddy DS.. Genetic and molecular regulation of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in the brain: Therapeutic insights for epilepsy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2018;364(2):180–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Olsen RW. GABAA receptor: Positive and negative allosteric modulators. Neuropharmacology. 2018;136(Pt A):10–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ferando I, Mody I.. GABAA receptor modulation by neurosteroids in models of temporal lobe epilepsies. Epilepsia. 2012;53 (Suppl 9):89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chandra D, Jia F, Liang J, et al. GABAA receptor alpha 4 subunits mediate extrasynaptic inhibition in thalamus and dentate gyrus and the action of gaboxadol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(41):15230–15235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Farrant M, Nusser Z.. Variations on an inhibitory theme: Phasic and tonic activation of GABAA receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(3):215–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Glykys J, Mody I.. Activation of GABAA receptors: Views from outside the synaptic cleft. Neuron. 2007;56(5):763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brickley SG, Mody I.. Extrasynaptic GABAA receptors: Their function in the CNS and implications for disease. Neuron. 2012;73(1):23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Glykys J, Mann EO, Mody I.. Which GABAA receptor subunits are necessary for tonic inhibition in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2008;28(6):1421–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Scimemi A, Semyanov A, Sperk G, Kullmann DM, Walker MC.. Multiple and plastic receptors mediate tonic GABAA receptor currents in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2005;25(43):10016–10024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kash SF, Johnson RS, Tecott LH, et al. Epilepsy in mice deficient in the 65-kDa isoform of glutamic acid decarboxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(25):14060–14065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuehn JC, Meschede C, Helmstaedter C, et al. Adult-onset temporal lobe epilepsy suspicious for autoimmune pathogenesis: Autoantibody prevalence and clinical correlates. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0241289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Manto MU, Laute MA, Aguera M, Rogemond V, Pandolfo M, Honnorat J.. Effects of anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies associated with neurological diseases. Ann Neurol. 2007;61(6):544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Macdonald RL, Kang JQ, Gallagher MJ.. Mutations in GABAA receptor subunits associated with genetic epilepsies. J Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 11):1861–1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Treiman DM. GABAergic mechanisms in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2001;42 (Suppl 3):8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schwarzer C, Tsunashima K, Wanzenböck C, Fuchs K, Sieghart W, Sperk G.. GABAA receptor subunits in the rat hippocampus II: Altered distribution in kainic acid-induced temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience. 1997;80(4):1001–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tsunashima K, Schwarzer C, Kirchmair E, Sieghart W, Sperk G.. GABAA receptor subunits in the rat hippocampus III: Altered messenger RNA expression in kainic acid-induced epilepsy. Neuroscience. 1997;80(4):1019–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Naylor DE, Liu H, Wasterlain CG.. Trafficking of GABAA receptors, loss of inhibition, and a mechanism for pharmacoresistance in status epilepticus. J Neurosci. 2005;25(34):7724–7733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Drexel M, Kirchmair E, Sperk G.. Changes in the expression of GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in parahippocampal areas after kainic acid induced seizures. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:142- [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nishimura T, Schwarzer C, Furtinger S, Imai H, Kato N, Sperk G.. Changes in the GABA-ergic system induced by trimethyltin application in the rat. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;97(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nishimura T, Schwarzer C, Gasser E, Kato N, Vezzani A, Sperk G.. Altered expression of GABAA and GABAB receptor subunit mRNAs in the hippocampus after kindling and electrically induced status epilepticus. Neuroscience. 2005;134(2):691–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peng Z, Huang CS, Stell BM, Mody I, Houser CR.. Altered expression of the delta subunit of the GABAA receptor in a mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2004;24(39):8629–8639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Houser CR, Esclapez M.. Downregulation of the alpha5 subunit of the GABAA receptor in the pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Hippocampus. 2003;13(5):633–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rice A, Rafiq A, Shapiro SM, Jakoi ER, Coulter DA, DeLorenzo RJ.. Long-lasting reduction of inhibitory function and gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor subunit mRNA expression in a model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(18):9665–9669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brooks-Kayal AR, Shumate MD, Jin H, Rikhter TY, Coulter DA.. Selective changes in single cell GABAA receptor subunit expression and function in temporal lobe epilepsy. Nat Med. 1998;4(10):1166–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fritschy JM, Kiener T, Bouilleret V, Loup F.. GABAergic neurons and GABAA receptors in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurochem Int. 1999;34(5):435–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bouilleret V, Loup F, Kiener T, Marescaux C, Fritschy JM.. Early loss of interneurons and delayed subunit-specific changes in GABAA receptor expression in a mouse model of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Hippocampus. 2000;10(3):305–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang N, Wei W, Mody I, Houser CR.. Altered localization of GABAA receptor subunits on dentate granule cell dendrites influences tonic and phasic inhibition in a mouse model of epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2007;27(28):7520–7531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shumate MD, Lin DD, Gibbs JW, Holloway KL, Coulter DA.. GABAA receptor function in epileptic human dentate granule cells: Comparison to epileptic and control rat. Epilepsy Res. 1998;32(1-2):114–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Loup F, Wieser HG, Yonekawa Y, Aguzzi A, Fritschy JM.. Selective alterations in GABAA receptor subtypes in human temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2000;20(14):5401–5419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stefanits H, Milenkovic I, Mahr N, et al. Alterations in GABAA receptor subunit expression in the amygdala and entorhinal cortex in human temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2019;78(11):1022–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pirker S, Czech T, Baumgartner C, et al. Chromogranins as markers of altered hippocampal circuitry in temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2001;50(2):216–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pirker S, Schwarzer C, Czech T, et al. Increased expression of GABAA receptor beta-subunits in the hippocampus of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62(8):820–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sperk G, Wieselthaler-Hölzl A, Pirker S, et al. Glutamate decarboxylase 67 is expressed in hippocampal mossy fibers of temporal lobe epilepsy patients. Hippocampus. 2012;22(3):590–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sur C, Fresu L, Howell O, McKernan RM, Atack JR.. Autoradiographic localization of alpha5 subunit-containing GABAA receptors in rat brain. Brain Res. 1999;822(1-2):265–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sperk G, Schwarzer C, Tsunashima K, Fuchs K, Sieghart W.. GABAA receptor subunits in the rat hippocampus I: Immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits. Neuroscience. 1997;80(4):987–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sperk G, Kirchmair E, Bakker J, Sieghart W, Drexel M, Kondova I.. Immunohistochemical distribution of 10 GABAA receptor subunits in the forebrain of the rhesus monkey Macaca mulatta. J Comp Neurol. 2020;528(15):2551–2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pirker S, Schwarzer C, Wieselthaler A, Sieghart W, Sperk G.. GABAA receptors: Immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 2000;101(4):815–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Blümcke I, Thom M, Aronica E, et al. International consensus classification of hippocampal sclerosis in temporal lobe epilepsy: A task force report from the ILAE commission on diagnostic methods. Epilepsia. 2013;54(7):1315–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mathern GW, Babb TL, Pretorius JK, Leite JP.. Reactive synaptogenesis and neuron densities for neuropeptide Y, somatostatin, and glutamate decarboxylase immunoreactivity in the epileptogenic human fascia dentata. J Neurosci. 1995;15(5 Pt 2):3990–4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Houser CR. Granule cell dispersion in the dentate gyrus of humans with temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Res. 1990;535(2):195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ohnuma T, Tessler S, Arai H, Faull RL, McKenna PJ, Emson PC.. Gene expression of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 and excitatory amino acid transporter 2 in the schizophrenic hippocampus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;85(1-2):24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Furtinger S, Pirker S, Czech T, Baumgartner C, Sperk G.. Increased expression of gamma-aminobutyric acid type B receptors in the hippocampus of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurosci Lett. 2003;352(2):141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Houser CR, Miyashiro JE, Swartz BE, Walsh GO, Rich JR, Delgado-Escueta AV.. Altered patterns of dynorphin immunoreactivity suggest mossy fiber reorganization in human hippocampal epilepsy. J Neurosci. 1990;10(1):267–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McGinnity CJ, Riaño Barros DA, Hinz R, et al. Αlpha 5 subunit-containing GABAA receptors in temporal lobe epilepsy with normal MRI. Brain Commun. 2021;3(1):fcaa190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Myers JF, Comley RA, Gunn RN.. Quantification of [11C]Ro15-4513 GABAA α5 specific binding and regional selectivity in humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37(6):2137–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Laufs H, Richardson MP, Salek-Haddadi A, et al. Converging PET and fMRI evidence for a common area involved in human focal epilepsies. Neurology. 2011;77(9):904–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Savic I, Svanborg E, Thorell JO.. Cortical benzodiazepine receptor changes are related to frequency of partial seizures: A positron emission tomography study. Epilepsia. 1996;37(3):236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Joshi S, Roden WH, Kapur J, Jansen LA.. Reduced neurosteroid potentiation of GABA. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020;7(4):527–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Scimemi A, Andersson A, Heeroma JH, et al. Tonic GABAA receptor-mediated currents in human brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24(4):1157–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Babb TL, Pretorius JK, Kupfer WR, Crandall PH.. Glutamate decarboxylase-immunoreactive neurons are preserved in human epileptic hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1989;9(7):2562–2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Esclapez M, Houser CR.. Up-regulation of GAD65 and GAD67 in remaining hippocampal GABA neurons in a model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Comp Neurol. 1999;412(3):488–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Feldblum S, Ackermann RF, Tobin AJ.. Long-term increase of glutamate decarboxylase mRNA in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuron. 1990;5(3):361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Marksteiner J, Sperk G.. Concomitant increase of somatostatin, neuropeptide Y and glutamate decarboxylase in the frontal cortex of rats with decreased seizure threshold. Neuroscience. 1988;26(2):379–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Najlerahim A, Williams SF, Pearson RC, Jefferys JG.. Increased expression of GAD mRNA during the chronic epileptic syndrome due to intrahippocampal tetanus toxin. Exp Brain Res. 1992;90(2):332–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pavlov I, Walker MC.. Tonic GABAA receptor-mediated signalling in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuropharmacology. 2013;69:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Collinson N, Kuenzi FM, Jarolimek W, et al. Enhanced learning and memory and altered GABAergic synaptic transmission in mice lacking the alpha 5 subunit of the GABAA receptor. J Neurosci. 2002;22(13):5572–5580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Crestani F, Keist R, Fritschy JM, et al. Trace fear conditioning involves hippocampal alpha5 GABAA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(13):8980–8985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Milić M, Timić T, Joksimović S, et al. PWZ-029, an inverse agonist selective for α5 GABAA receptors, improves object recognition, but not water-maze memory in normal and scopolamine-treated rats. Behav Brain Res. 2013;241:206–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.