Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has negatively affected the mental health of the general population. However, less is known about its impact on vulnerable populations, such as veterans with pre-existing psychiatric conditions. Data were analyzed from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study, which surveyed a nationally representative cohort of U.S. veterans. Pre-pandemic and 1-year peri-pandemic risk and protective factors associated with suicidal ideation (SI) were examined in veterans with pre-existing psychiatric conditions. 19.2% of veterans screened positive for SI peri-pandemic. Relative to veterans without SI, they had lower income, were more likely to have been infected with COVID-19, reported greater COVID-19-related financial and social restriction stress, and increases in psychiatric symptoms and loneliness during the pandemic. A multivariable analysis revealed that older age, greater pre-pandemic psychiatric symptom severity, past-year SI, lifetime suicide attempt, psychosocial difficulties, COVID-19 infection, and past-year increase in psychiatric symptom severity were linked to peri-pandemic SI, while pre-pandemic higher income and purpose in life were protective. Among veterans who were infected with COVID-19, those aged 45 or older and who reported lower purpose in life were more likely to endorse SI. Monitoring for suicide risk and worsening psychiatric symptoms in older veterans who have been infected with COVID-19 may be important. Interventions that enhance purpose in life may help protect against SI in this population.

Keywords: Suicide, Depression, PTSD, Substance use disorder, COVID-19

1. Introduction

Suicide has been a serious public health issue even prior to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, increasing 36.5% from 10.4 to 14.2 per 100,000 persons between 2000 and 2018 (Hedegaard et al., 2018; CDC Injury Prevention and Control, 2020). During the same period, veterans have shown a higher (48.6%) increase in suicide rate and 27.5 deaths by suicide per 100,000 persons in 2018 (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2020). In 2018, veterans comprised 7.1% of the U.S. population (Vespa, 2020) while accounting for 13.8% of all deaths by suicide (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2020). Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed people's lives dramatically, with increased social isolation, economic recession, and sense of powerlessness (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2020; Reger et al., 2020). Preliminary reports show a substantial increase in prevalence of depression and anxiety in the general public during the pandemic (Ettman et al., 2020; Czeisler et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2020a; Wathelet et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020), and it has been suggested that this may be accompanied by a possible increase in deaths by suicides (Reger et al., 2020; Gunnel et al., 2020; Sher, 2020).

Extant literature suggests that the incidence of suicide increased in the US during the 1918-19 influenza pandemic (Wasserman, 1992). During the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Hong Kong, the rate of suicide increased by 13.9% compared to the previous year (HKJC Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention, 2020), and the most significant increase was found among older adults (Yip et al., 2010). Preliminary reports on rates of overall suicide deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic show relatively stable rates in higher income countries (John et al., 2020).

Veterans may be uniquely vulnerable to negative mental health effects of the pandemic such as suicidality due to their older age (Wiechers et al., 2015), previous trauma exposures (Marini et al., 2020), and higher pre-pandemic prevalence of physical (e.g. disability, traumatic brain injury [TBI], medical comorbidities) and psychiatric risk factors (e.g. adverse childhood experiences [ACEs]) and conditions (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], substance use disorder [SUD]) relative to the general population (Wiechers et al., 2015; Villa et al., 2003; Dohrenwend et al., 2006; Pietrzak et al., 2014; Williamson et al., 2018). Another potentially vulnerable population for suicide during the pandemic are older adults who are more likely than younger adults to have underlying physical illnesses and functional impairments, which may be exacerbated by stressors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., difficulties accessing health care, social distancing measures), and may contribute to late-life suicide (Yip et al., 2010; Sheffler et al., 2020). However, preliminary large surveys of the general population conducted during the pandemic show the opposite, with older adults actually being less affected by psychiatric issues compared to other age groups (Vahia et al., 2020). Thus, whether older age is protective or a risk of worse mental health during the pandemic remains to be elucidated.

In addition, individuals with pre-existing psychiatric disorders have been identified as a subpopulation that may be at particularly increased risk for suicide during the pandemic (Yao et al., 2020). In a multinational study of individuals with pre-existing psychiatric disorders, self-reported worsening of psychiatric symptoms was endorsed by two-thirds of those surveyed, and in an independent clinical investigation of over 300 psychiatric patients in the US, over 50% required clinical interventions such as dose adjustment or prescription of new medication (Gobbi et al., 2020; Hamada and Fan, 2020). Potential contributors to worsening psychiatric symptoms in this population include social isolation, disruption of mental health services, increased stress, anxiety and fear, and greater reliance on use of substances (Yao et al., 2020; Hamada and Fan, 2020).

Numerous previous studies have identified risk factors for suicidal behavior. According to the American Association of Suicidology (AAS), these risk factors may be categorized into permanent/non-modifiable (e.g. demographics, previous suicidal behavior, history of trauma), predisposing (e.g. psychiatric and/or medical conditions, TBI), and acute (e.g. substance use, psychological pain, psychosocial stressors) (American association of suicidology, 2018). However, protective factors such as purpose in life, resilience, optimism, gratitude, community integration, and social support, which have been linked to lower likelihood of suicidality (Straus et al., 2019, Mclean et al., 2008; Mcclatchey et al., 2019), have received less attention in the suicide literature.

To date, extant research on mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic is limited in a number of ways. First, nearly all published studies have used cross-sectional or retrospective surveys carried out after the start of the pandemic, and are thus prone to selection bias (Pierce et al., 2020b). Second, scarce research has examined how pre-pandemic factors relate to mental health factors such as SI during the pandemic. Hence, little is known about the longitudinal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicidal behavior (Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2020). Third, most research has focused on general population samples, and no known study has investigated the mental health impact of the pandemic in veterans. Consequently, it is unclear whether observed results apply to groups at higher risk for suicide, such as veterans or those with pre-existing psychiatric conditions. Fourth, although some studies have reported increased prevalence of SI in those infected with COVID-19 (Mazza et al., 2020), it is unknown to what extent COVID-related stressors may influence SI risk in those with pre-existing psychiatric conditions. Fifth, possible interactions between COVID-19 infection and age and protective factors on SI risk have not yet been examined. It is thus crucial to identify the risk and protective factors, including both COVID-related and non-related factors, in individuals at high-risk of suicide, such as veterans with pre-existing psychiatric disorders, as such data can help inform targeted, effective, and timely suicide prevention strategies (Gunnel et al., 2020).

To address the aforementioned gaps in knowledge, we analyzed data from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study (NHRVS; Fogle et al., 2020) to examine pre-pandemic, COVID-related, and changes in risk and protective factors associated with peri-pandemic SI. We additionally evaluated interactions between COVID-19 infection and age, and significant protective factors, in predicting SI in this population. Based on the theoretical framework put forth by the AAS and extant literature on suicide (American association of suicidology, 2018), we had the opportunity to examine a comprehensive range of risk and protective factors.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

Data were drawn from the NHRVS, a nationally representative prospective survey of U.S. military veterans two timepoints one year apart. A total of 4069 veterans completed the Wave 1 (median completion date: 11/21/2019) survey prior to the first documented COVID-19 cases in the US and 3078 (75.6%) completed a 1-year follow-up Wave 2 (median completion date: 11/14/2020) survey. Wave 1 survey will be referred to “pre-pandemic survey” and Wave 2 survey will be referred to “peri-pandemic survey.” Details of the study, including the recruitment protocol, has been described previously (Fogle et al., 2020). Briefly, the NHRVS sample was drawn from KnowledgePanel®, a survey research panel of more than 50,000 U.S. households maintained by Ipsos, a survey research firm. To ensure generalizability of the results to the US veteran population, poststratification weights were computed based on the demographic distribution of veterans in the US Census Current Population Survey. In the current study, a total of 661 veterans (23.8% of peri-pandemic sample) screened positive for major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), PTSD, and/or SUD at the pre-pandemic assessment. We focused on this subsample based on previous research suggesting that individuals with pre-existing psychiatric conditions are at higher risk of mental health problems during the pandemic (Yao et al., 2020). The study protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Subcommitee of the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, and all participants provided informed consent.

2.2. Measures

Suicidal ideation. Peri-pandemic SI was assessed using two items adapted from the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., 2001), which asked participants to report SI during the prior two weeks. A positive screen for current SI was indicated by a response of “several days,” “more than half the days,” or “nearly every day” to at least one of the following questions: “How often have you been bothered by thoughts that you might be better off dead?” and “How often have you been bothered by thoughts of hurting yourself in some way?”

Sociodemographic characteristics. Information on pre-pandemic age, gender, race, education, marital status, income, employment, and combat veteran status was assessed.

Risk factors (pre-pandemic).Table 1 presents a detailed description of measures used to assess psychiatric symptoms/diagnoses, cumulative trauma burden, ACEs, suicidality (lifetime suicide attempt, past-year SI, and likelihood of suicide attempt in following year), psychosocial difficulties, loneliness, and physical characteristics.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and potential risk and protective factors examined in relation to suicidal ideation in high risk U.S. veterans.

|

Sociodemographic characteristics |

Age (continuous), gender (dichotomous: male vs female), race (dichotomous: white vs non-white), education (dichotomous: college graduate or higher vs up to high school diploma), marital status (dichotomous: married/living with partner vs unmarried), income (dichotomous: $60,000 or more vs less than $60,000), employment (dichotomous: working vs retired), and combat status (dichotomous: no combat exposure vs combat) |

| Risk factors | |

| Psychiatric symptoms | |

| Current psychiatric symptom severity | MDD symptoms – participant responses on the two depressive symptoms of the PHQ-4 occurring in the past two weeks (Ω = 0.87); a score ≥ 3 was indicative of a positive screen for MDD (Kroenke et al., 2009); PTSD symptoms-assessed with the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (Ω = 0.98); a score ≥ 33 was indicative of a positive screen for PTSD (Weathers et al., 2013b); GAD symptoms – participant responses on the two generalized anxiety items of the PHQ-4 occurring in the past two weeks ((Ω = 0.84); a score ≥ 3 was indicative of a positive screen for GAD (Kroenke et al., 2009). |

| Alcohol use problem severity | Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) total score (Ω = 0.85); a score ≥ 8 was indicative of a positive screen for AUD (Bohn et al., 1995). |

| Non-prescription drug use days in past year | Screen for Drug Use question: How many days in the past year have you used non-prescription drugs?; a response of ≥ 7 days on this question is indicative of a positive screen for DUD; if the response to this question is 6 or fewer days, a response of ≥ 2 days to the question “How many days in the past 12 months have you used drugs more than you meant to?” is indicative of a positive screen for DUD. |

| Cumulative trauma burden | Count of potentially traumatic events on the Life Events Checklist for DSM-5. (Weathers et al., 2013a). |

| Adverse childhood experiences | Score on Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (Felitti et al., 1998). |

| Suicide variables | |

| Lifetime suicide attempt | “Have you ever tried to kill yourself?” |

| Past-year suicidal ideation | Positive endorsement of question 2 of the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R): “How often have you thought about killing yourself in the past year?”(Osman et al., 2001) |

| Likelihood of suicide attempt in next year | Endorsement of “Likely,” “Rather Likely,” or “Very Likely” on question 4 of the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R): “How likely is it that you will attempt suicide someday?” |

| Psychosocial difficulties | Score on the Brief Inventory of Psychosocial Functioning (Marx et al., 2019). |

| Loneliness | Score on 3-item measure adapted from the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Hughes et al., 2004); Ω = 0.86. |

| Physical health characteristics | |

| Concussion/TBI | Report of healthcare professional-diagnosed concussion or traumatic brain injury. |

| Number of medical conditions | Sum of number of medical conditions endorsed in response to question: “Has a doctor or healthcare professional ever told you that you have any of the following medical conditions?” (e.g., arthritis, cancer, diabetes, heart disease, asthma, kidney disease). Range: 0–24 conditions. |

| ADL disability | Any disability in activities of daily living. The following question was asked: “At the present time, do you need help from another person to do the following?” (e.g., bathe; walk around your home or apartment; get in and out of chair). Endorsement of any of these activities was indicative of having a disability with an activity of daily living.(Hardy and Gill, 2004) |

| IADL disability | Any disability in instrumental activities of daily living. The following question was asked: “At the present time, do you need help from another person to do the following?” (e.g., pay bills or manage money; prepare bills; get dressed). Endorsement of any of these activities was indicative of having a disability with an instrumental activity of daily living (Hardy and Gill, 2004). |

| Protective factors | |

| Engagement in mental health treatment | Positive endorsement of current treatment with psychotropic medication and/or psychotherapy or counseling: “Are you currently taking prescription medication for a psychiatric or emotional problem?” Are you currently receiving psychotherapy or counseling for a psychiatric or emotional problem? |

| Perceived social support | Score on 5-item version of the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale (Sherbourne and Stewart, 1991;, Amstadter et al., 2011); Ω = 0.89. |

| Resilience | Score on Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-10 (Campbell-Sills and Stein, 2007); Ω = 0. 92. |

| Purpose in life | Score on Purpose in Life Test-Short Form (Schulenberg et al., 2010); Ω = 0.90. |

| Dispositional optimism | Score on single-item measure of optimism from Life Orientation Test-Revised (Scheier et al., 1994); “In uncertain times, I usually expect the best”; (rating 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). |

| Dispositional gratitude | Score on single-item measure of gratitude from Gratitude Questionnaire (McCullough et al., 2002); “I have so much in life to be thankful for”; (rating 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). |

| Curiosity/exploration | Score on single-item measure of curiosity/exploration from Curiosity and Exploration Inventory-II (Kashdan et al., 2009); “I frequently find myself looking for new opportunities to grow as a person (e.g., information, people, resources”); (rating 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). |

| Community integration | Perceived level of community integration: “I feel well integrated in my community (e.g., regularly participate in community activities); ” (rating 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). |

| Change variables (from pre-pandemic to peri-pandemic) | Changes in household income, psychiatric symptom severity, alcohol use problem severity, days of non-prescription drug use days in past year, psychosocial difficulties, loneliness, social support, and protective psychosocial characteristics |

| COVID-19 variables (peri-pandemic) | Hours consuming COVID-related media; |

| COVID infection status (self, or household/non-household member) using a questionnaire developed by the National Center for PTSD. | |

| COVID-related worries (Ω = 0.91), social restriction stress, financial stress, relationship difficulties, and social engagement were assessed based on the Coronavirus Health Impact Survey (NIMH Intramural Research Program, 2020). COVID-related worries (e.g., “In the past month, how worried have you been about being infected with coronavirus?”); COVID-social restriction stress (e.g., “How stressful have these changes in social contacts been for you?”); COVID-related financial hardship (e.g., “In the past month, to what degree have changes related to the pandemic created financial problems for you or your family?”); COVID-related relationship difficulties (e.g., “Has the quality of the relationships between you and members of your family changed?”); and COVID-related social engagement (e.g., “In the past month, how many people, from outside of your household, have you had an in-person conversation with?”). | |

| COVID-related PTSD symptoms were assessed using the 4-item PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (Geier et al., 2020) (score range = 0–16; Ω = 0.77; sample item: “Thinking about the Coronavirus/COVID-19 pandemic, please indicate how much you have been bothered by repeated, disturbing, and unwanted memories of the pandemic”); a score ≥ 5 is indicative of a positive screen for PTSD. | |

| Sum of traumas since baseline were assessed using a total count of past-year potentially traumatic events on the LEC-5 (Weathers et al., 2013a) | |

AUD = alcohol use disorder, ADL = activities of daily living, COVID = coronavirus disease, DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, DUD = drug use disorder, GAD = generalized anxiety disorder, IADL = instrumental activities of daily living, MDD = major depressive disorder, PHQ = patient health questionnaire, PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder, SUD = substance sue disorder, TBI = traumatic brain injury.

Protective factors (pre-pandemic).Table 1 presents a description of potential protective factors of SI, which included engagement in mental health treatment, social support, resilience, purpose in life, dispositional optimism and gratitude, curiosity/exploration, and community integration.

COVID-related variables. COVID-19 infection status of veterans, household members, and non-household members and hours spent consuming COVID-related media were assessed at peri-pandemic using a questionnaire developed by the National Center for PTSD. Questions from the Coronavirus Health Impact Survey (National Institute of Mental Health Intramural Research Program Mood Spectrum Collaboration and Child Mind Institute of the NYS Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, 2020) were used to assess COVID-related worries and concerns, and social engagement.

A 4-item version of the PTSD Checklist (Geier et al., 2020) for DSM-5 was used to assess COVID-related PTSD symptoms. Lastly, sum of traumas were assessed by summing the number of past-year potentially traumatic events on the Life Event Checklist for DSM-5 (Weathers et al., 2013a, Weathers et al., 2013b).

Change variables. Differences in scores (peri-pandemic – pre-pandemic) were computed for measures of household income, psychiatric symptom severity, alcohol use problem severity, days of non-prescription drug use days in past year, psychosocial difficulties, loneliness, social support, resilience, purpose in life, dispositional optimism and gratitude, curiosity, and community integration.

2.3. Statistical analysis

First, we compared sociodemographic, trauma exposure, and psychosocial characteristics of veterans with and without peri-pandemic SI using chi-square and independent-samples t-tests. Second, we conducted a multivariable binary logistic regression analysis with a data-driven estimation method (backward Wald) to identify independent pre-pandemic, peri-pandemic, and changes in risk and protective factors that were associated with peri-pandemic SI; we employed a liberal approach to variable selection by entering variables associated with peri-pandemic SI at the p < 0.10 level in bivariate analyses into this analysis. We then incorporated into the model interactions of COVID-19 infection-by-age and COVID-19 infection-by-purpose in life, which was the sole significant pre-pandemic protective factor associated with peri-pandemic SI.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics of participants with vs without SI

The final sample included 661 veterans who completed both pre- and peri-pandemic surveys of the NHRVS and screened positive for pre-pandemic MDD, GAD, PTSD, and/or SUD. The average age of participants was 55.2 years (SD = 15.4: range 23–92); the majority were male (86.8%), and Caucasian (75.1%), and 40.3% were combat veterans. The majority of the sample screened positive for 1 (n = 444; 64.4%), 2 (n = 136; 19.4%), or 3 (n = 56; 10.7%) disorders, with an additional 21 (5.1%) and 3 (0.4%) screening positive for 4 or 5 disorders, respectively.

Table 2 displays pre-pandemic characteristics of veterans with and without peri-pandemic SI. Overall, 19.2% of veterans (n = 127) screened positive for peri-pandemic SI and 80.8% (n = 534) did not screen positive for SI. Compared to veterans without peri-pandemic SI, those with SI were younger and were less likely to have a household income greater than $60,000; they also reported more ACEs, higher psychiatric symptom severity, were more likely to have ever attempted suicide and to report past-year SI, and reported a higher likelihood of suicide attempt in the following year. They also scored higher on measures of psychosocial difficulties and loneliness, and lower on measures of social support, resilience, purpose in life, dispositional optimism and gratitude, curiosity, and community integration.

Table 2.

Characteristics of high-risk veterans with and without peri-pandemic suicidal ideation.

| No Suicidal Ideation |

Suicidal Ideation |

Test of difference |

p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 534 (80.8%) |

N = 127 (19.2%) |

|||

| Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

|||

| or |

or |

|||

| N (weighted %) | N (weighted %) | |||

| Pre-pandemic variables | ||||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Age | 58.3 (14.9) | 54.0 (13.8) | 3.01 | 0.003 |

| Male gender | 449 (89.7%) | 111 (91.9%) | 0.6 | 0.44 |

| White race/ethnicity | 428 (77.7%) | 95 (75.7%) | 0.23 | 0.63 |

| College graduate or higher education | 215 (31.6%) | 42 (27.2%) | 0.99 | 0.32 |

| Married/partnered | 353 (68.0%) | 87 (68.4%) | 0.01 | 0.93 |

| Household income $60K or higher | 313 (58.4%) | 56 (39.7%) | 15.49 | <.001 |

| Worked/retired | 486 (88.3%) | 108 (82.2%) | 3.61 | 0.057 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Combat veteran | 184 (38.6%) | 60 (47.1%) | 3.24 | 0.072 |

| Adverse childhood experiences | 2.1 (2.3) | 2.9 (2.5) | 3.33 | 0.001 |

| Total traumas | 11.6 (10.2) | 11.6 (9.3) | 0.02 | 0.99 |

| Psychiatric symptom severity | 0.6 (1.3) | 1.7 (1.5) | 8.01 | <.001 |

| Alcohol use problem severity | 6.8 (6.8) | 7.6 (8.7) | 1.14 | 0.25 |

| Non-prescription drug use days in past year | 60.9 (120.8) | 50.0 (112.7) | 0.93 | 0.35 |

| Lifetime suicide attempt | 30 (6.1%) | 24 (18.4%) | 21.3 | <.001 |

| Past-year suicidal ideation | 82 (16.4%) | 74 (58.5%) | 104.67 | <.001 |

| Likelihood of suicide attempt in next year | 80 (14.0%) | 64 (45.6%) | 68.44 | <.001 |

| Number of medical conditions | 3.3 (2.3) | 3.8 (2.4) | 1.89 | 0.059 |

| Concussion/TBI | 45 (11.0%) | 23 (17.0%) | 3.71 | 0.054 |

| Any ADL and/or IADL disability | 97 (21.0%) | 48 (30.4%) | 5.43 | 0.02 |

| Psychosocial difficulties | 16.5 (17.3) | 33.3 (24.5) | 9.31 | <.001 |

| Loneliness | 5.3 (2.0) | 6.8 (1.9) | 8.28 | <.001 |

| Protective factors | ||||

| Currently engaged in mental health treatment | 115 (22.0%) | 54 (41.2%) | 21.22 | <.001 |

| Social support | 17.5 (5.4) | 14.2 (5.2) | 6.35 | <.001 |

| Perceived resilience | 37.7 (7.1) | 31.7 (8.3) | 8.5 | <.001 |

| Purpose in life | 19.9 (5.1) | 14.5 (5.9) | 10.84 | <.001 |

| Dispositional optimism | 4.6 (1.6) | 3.6 (1.8) | 6.51 | <.001 |

| Dispositional gratitude | 6.0 (1.2) | 4.8 (1.7) | 9.54 | <.001 |

| Curiosity | 4.8 (1.5) | 3.8 (1.7) | 7.14 | <.001 |

| Community integration | 3.5 (1.7) | 2.7 (1.6) | 4.61 | <.001 |

| Peri-pandemic variables | ||||

| Hours consume COVID-related media per week | 1.9 (2.8) | 1.9 (2.4) | 0 | 0.99 |

| Infected with COVID-19 | 56 (9.8%) | 21 (17.9%) | 7.12 | 0.008 |

| Household member infected with COVID-19 | 42 (9.0%) | 17 (14.2%) | 3.29 | 0.07 |

| Non-household member infected with COVID-19 | 256 (45.8%) | 68 (50.7%) | 1.08 | 0.3 |

| Positive screen for COVID-related PTSD | 104 (19.8%) | 42 (26.5%) | 2.94 | 0.086 |

| COVID-related worries | 0.2 (1.1) | 0.1 (1.0) | 1 | 0.32 |

| COVID-related social restriction stress | 0.2 (1.1) | 0.5 (1.3) | 2.16 | 0.031 |

| COVID-related financial stress | 0.1 (1.2) | 0.9 (1.5) | 5.8 | <.001 |

| COVID-related worsening relationships | 0.0 (1.1) | 0.1 (1.2) | 1.42 | 0.16 |

| Social engagement during pandemic | 0.0 (1.0) | −0.1 (0.9) | 1.59 | 0.11 |

| Sum of traumas over past year | 1.5 (2.5) | 1.8 (2.1) | 1.24 | 0.22 |

| Currently engaged in mental health treatment | 118 (23.6%) | 69 (55.1%) | 52.61 | <.001 |

| Change variables (from pre- to peri-pandemic) | ||||

| Change in household income | 0.0 (2.1) | 0.4 (2.4) | 1.7 | 0.12 |

| Change in psychiatric symptom severity | −0.6 (1.1) | −0.1 (1.1) | 3.47 | 0.001 |

| Change in alcohol use problem severity | −1.0 (4.1) | −0.8 (4.7) | 0.57 | 0.57 |

| Change in days of non-prescription drug use in past year | 1.6 (95.0) | 4.5 (54.7) | 0.32 | 0.75 |

| Change in psychosocial difficulties | 1.1 (15.8) | 7.0 (22.2) | 1.42 | 0.16 |

| Change in loneliness | −0.3 (1.4) | 0.1 (1.4) | 3.06 | 0.002 |

| Change in social support | 0.3 (4.9) | 0.1 (4.4) | 0.58 | 0.56 |

| Change in perceived resilience | −0.4 (6.1) | 0.3 (6.1) | 1.19 | 0.23 |

| Change in purpose in life | 0.2 (3.9) | 0.0 (4.8) | 0.67 | 0.51 |

| Change in dispositional optimism | 0.1 (1.4) | −0.1 (1.3) | 1.53 | 0.13 |

| Change in dispositional gratitude | 0.0 (1.4) | 0.1 (1.9) | 0.51 | 0.61 |

| Change in curiosity | −0.1 (1.3) | 0.0 (1.6) | 1.01 | 0.31 |

| Change in community integration | 0.0 (1.5) | −0.1 (1.8) | 0.56 | 0.58 |

ADL = activities of daily living, COVID = corona virus disease, IADL = instrumental activities of daily living, PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder, SD = standard deviation, TBI = traumatic brain injury.

With respect to COVID-related variables, veterans with peri-pandemic SI were more likely than those without SI to have been infected with COVID-19, and scored higher on measures of COVID-related social restriction and financial stress. They also reported greater increases in symptom severity and loneliness over the follow-up period.

3.2. Risk factors and protective factors for peri-pandemic SI

Table 3 shows variables included in the final multivariable regression model predicting peri-pandemic SI. Among pre-pandemic variables, greater age, psychiatric symptom severity, past-year SI, lifetime suicide attempt, and psychosocial difficulties were associated with peri-pandemic SI, while household income of $60,000 or higher and purpose in life were negatively associated with SI. COVID-19 infection and increase in psychiatric symptom severity from pre-to peri-pandemic were also associated with peri-pandemic SI. A sensitivity analysis that additionally incorporated a count of pre-pandemic positive screens for MDD, GAD, PTSD, and SUD into this analysis indicated that it was unrelated to peri-pandemic SI (p = 0.29).

Table 3.

Results of multivariable logistic regression analysis of variables associated with peri-pandemic current suicidal ideation.

| Nagelkerke R2 = 0.55 | Wald | P | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-pandemic variables | ||||

| Age | 9.38 | 0.002 | 1.05 | 1.02-1.08 |

| Household income $60,000 or higher | 7.35 | 0.007 | 0.38 | 0.19-0.76 |

| Psychiatric symptom severity | 8.44 | 0.004 | 1.86 | 1.22-2.83 |

| Past-year suicidal ideation | 26.47 | <.001 | 7.95 | 3.61-17.51 |

| Lifetime suicide attempt | 4.01 | 0.045 | 2.80 | 1.02–7.65 |

| Psychosocial difficulties | 11.69 | 0.001 | 1.04 | 1.02-1.06 |

| Purpose in life | 7.98 | 0.005 | 0.88 | 0.81-0.96 |

| Peri-pandemic variables | ||||

| Infected with COVID-19 | 7.88 | 0.005 | 3.43 | 1.45-8.12 |

| Change variables | ||||

| Increase in psychiatric symptoms severity | 51.29 | <.001 | 4.63 | 3.04–7.04 |

CI = confidence interval, COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019, OR = odds ratio.

Interaction effects between COVID-19 infection and age and protective factors on peri-pandemic SI.

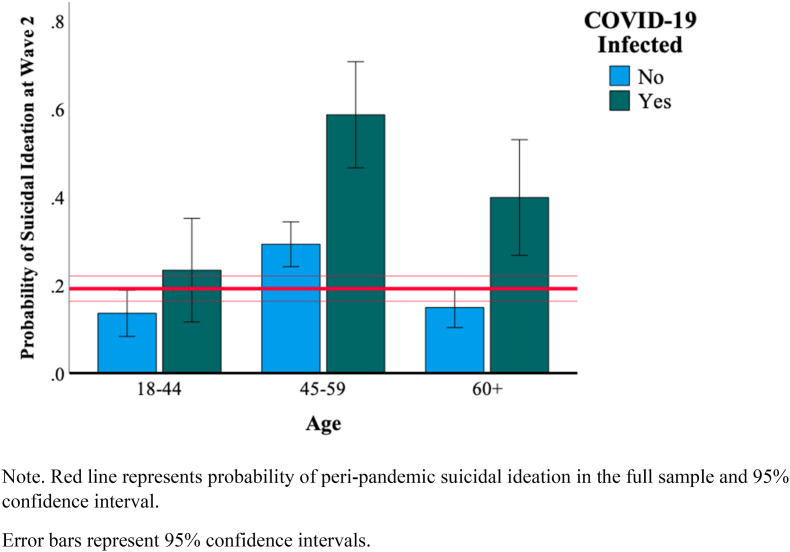

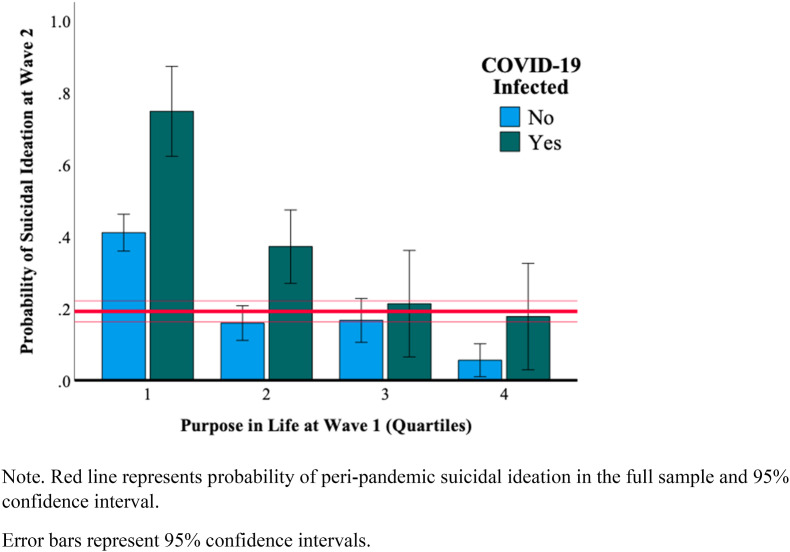

Significant interactions were observed for age x COVID-19 infection (Wald χ 2 = 9.84, p = 0.002) and purpose in life x COVID-19 infection (Wald χ 2 = 15.29, p < 0.001). Fig. 1, Fig. 2 illustrate these interactions, which showed the highest probability of peri-pandemic SI among veterans 45–59 and 60+ year-olds who were infected with COVID-19 over the study period; and who were with the lowest quartile of pre-pandemic purpose in life.

Fig. 1.

Interaction of age x COVID-19 infection in predicting peri-pandemic suicidal ideation

Note. Red line represents probability of peri-pandemic suicidal ideation in the full sample and 95% confidence interval.

Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 2.

Interaction of pre-pandemic purpose in life and COVID-19 infection in predicting peri-pandemic suicidal ideation

Note. Red line represents probability of peri-pandemic suicidal ideation in the full sample and 95% confidence interval.

Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine longitudinal risk and protective factors of SI during the COVID-19 pandemic in a nationally representative sample of veterans with pre-existing psychiatric conditions. Variables were selected based on the framework of the AAS and prior research on factors that may help mitigate risk of suicide. Results revealed that pre-pandemic older age, greater psychiatric symptom severity and psychosocial difficulties, past-year SI, lifetime suicide attempt, increase in past-year psychiatric symptom severity and COVID-19 infection were independent risk factors for peri-pandemic SI, whereas pre-pandemic greater purpose in life and higher household income were protective.

Previous surveys of individuals infected with COVID-19 reported high prevalence of mental disorders, including depression (Ma et al., 2020), anxiety (Paz et al., 2020), and PTSD (Mazza et al., 2020). For example, in a study on 402 adult survivors of COVID-19 (mean age 58), 28% met the diagnostic threshold for PTSD, 31% for depression, and 42% for anxiety at one month follow-up after hospital treatment (Mazza et al., 2020). In our study, COVID-19 infection was an independent risk factor of peri-pandemic SI for veterans with pre-existing psychiatric conditions, affecting 17.9% of those with peri-pandemic SI relative to 9.8% of those without SI.

COVID-related stressors such as economic stress and social isolation due to pandemic restrictions have been suggested as possible risk factors of suicidal behavior during the pandemic (Reger et al., 2020; Banerjee et al., 2021; Gunnel et al., 2020). In our study, veterans with peri-pandemic SI reported worse COVID-related financial and social restriction stressors compared to those without SI. This finding is consistent with the Conservation of Resources Theory, which suggests that a loss of resources may lead to traumatic stress (Hobfoll, 1991), as well as studies showing that economic distress during the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected people's mental health (Codagnone et al., 2020). While COVID-related stressors were not significant when considered in the context of other factors, pre-pandemic lower household income was a significant risk factor for peri-pandemic SI. This finding is consistent with a nationally representative study of U.S. adults in which financial strain, including lower household income, was linked to an increased likelihood of suicide attempt (Elbogen et al., 2020). Veterans with lower pre-pandemic income may have had less access to services, less savings to endure economic hardship, and/or greater anxiety related to the future, which in turn contributed to SI risk.

It has also been proposed that COVID-related worries and media consumption may exacerbate mental health burden (Su et al., 2021; Gunnel et al., 2020; Bendau et al., 2020). In our study, COVID-related media consumption did not differ between those with and without peri-pandemic SI, suggesting that frequency of media consumption may be unrelated to SI in veterans with pre-existing psychiatric conditions. While veterans with peri-pandemic SI were on average younger than those without SI, older age was associated with increased risk of SI when considered in the context of other risk and protective factors, thus underscoring the importance of assessing suicide risk in older veterans with pre-existing psychiatric conditions. Further, veterans aged 45–59 and 60 and older who were infected with COVID-19 were at highest risk of peri-pandemic SI, with 58.7% and 39.9% of these groups endorsing SI, respectively, compared to 23.4% of veterans aged 18–44. It is well known that older adults are more likely to suffer from a more severe illness course and sequelae of COVID-19 infection (Shahid et al., 2020). Thus, one possible interpretation of this interaction is that older veterans with pre-existing psychiatric conditions who were infected with COVID-19 may have experienced more severe psychological distress and/or negative mood symptoms given heightened worries associated with higher mortality risk related to COVID-19 in older individuals. It is also noteworthy that greater pre-pandemic psychiatric symptom severity and psychosocial difficulties, and aggravation of psychiatric symptoms over the past year were associated with increased risk of peri-pandemic SI. The finding that an increase in psychiatric symptom severity during the pandemic was linked to peri-pandemic SI above and beyond baseline levels of distress is consistent with studies in the general population, which have similarly observed increases in psychological distress during the pandemic (Czeisler et al., 2020; Ettman et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2020a). Collectively, these findings underscore the importance of continued monitoring and intervention for worsening psychiatric symptoms in both high-risk individuals and the general population at large.

Greater pre-pandemic purpose in life protected against peri-pandemic SI, even after accounting for a broad range of other risk and protective factors. Further, purpose in life interacted with COVID-19 infection, with three-quarters of veterans in the lowest quartile of pre-pandemic purpose in life who were infected with COVID-19 endorsing peri-pandemic SI relative to 17.7% of veterans in the highest quartile of purpose in life who were infected with COVID-19. This finding extends prior work linking lack of meaning in life or feeling needed by others with suicide risk (Ozawa-de Silva, 2020; Van orden et al., 2010; Heisel and Flett, 2014), including high-risk veterans (Straus et al., 2019) to suggest that high-risk veterans with low purpose in life who were infected with COVID-19 may be at particularly elevated risk for suicide. Higher purpose in life, which has been linked to more effective regulation of the stress response (Van reekum et al., 2007; Ishida and Okada, 2006), may help promote engagement in adaptive coping strategies, such as soliciting social support or engaging in physical exercise to help manage distress and suicidality (Van reekum et al., 2007; Ishida and Okada, 2006; Hooker and Masters, 2014).

Based on these findings, clinical interventions designed to foster purpose in life may help mitigate suicide risk in veterans with pre-existing psychiatric conditions. Several evidence-based clinical interventions have been developed to enhance and promote purpose in life, including acceptance and commitment therapy (Hayes et al., 2006), logotherapy (Marshall and Marshall, 2012), reminiscence interventions (Pinquart and Forstmeier, 2012), and dignity therapy (Chochinov et al., 2006). Another therapeutic avenue may be religiosity/spirituality, which is strongly associated with purpose in life (Koenig et al., 2014). Utilizing evidence-based interventions and maximizing the current capacity of chaplain care through innovative methods such as remote group meetings and virtual appointments to those with mental illnesses may serve as a tailored suicide prevention approach.

This study has several limitations. First, we used screening instruments to assess psychiatric symptoms and SI; further research using structured clinical interviews is needed to replicate the results reported herein. Secondly, while nationally representative, our sample was comprised entirely of U.S. military veterans, who are predominantly older, and white, which makes it difficult to generalize results to non-veteran populations. However, it is also worth noting that this study is the first to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on SI in veterans, who are at heightened suicide risk. Third, due to the low prevalence of peri-pandemic suicide attempts within the past year (n = 5, 0.9%), we utilized current SI as a surrogate measure of potential suicide risk.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the coincidental timing of our initial and follow-up surveys has provided a unique opportunity to examine nationally representative data on a broad range of risk and protective factors for peri-pandemic SI that may be targeted in suicide prevention efforts in veterans with pre-existing psychiatric conditions. Based on our findings, those who were infected with COVID-19 and aged 45 or older or who reported lower purpose in life may be at the highest risk of suicide, and may deserve close clinical attention and monitoring. Given the urgency and time sensitivity of the mental health crisis during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the results underscore the importance of efforts to mitigate psychiatric/psychosocial and financial distress, and enhance purpose in life in veterans with pre-existing psychiatric conditions. Further research is needed to replicate and extend these results to other high-risk populations; identify mechanisms leading to increased suicidality during the pandemic; and evaluate the efficacy of interventions targeting evidence-based risk and protective factors, including both negative (e.g., psychiatric symptoms, psychosocial difficulties) and salutogenic (e.g., purpose in life) factors, in mitigating suicide risk in veterans and other populations at heightened risk for suicide.

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors have any competing interests.

Funding

The National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study is supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

Role of the funder/sponsor

The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author statement

Peter J. Na assisted with the study design and conceptualization, and writing of the paper. Melanie L. Hill, Brandon Nichter, and Sonya B. Norman collaborated in the writing and editing of the manuscript. Jack Tsai and Steven M. Southwick assisted in the study design and editing of the manuscript. Robert H. Pietrzak designed the study, analyzed the data, and collaborated in the writing and editing of the manuscript.

References

- American association of suicidology Risk factors for suicide and suicidal behaviors. 2018. https://deploymentpsych.org/system/files/member_resource/4-AAS%20Risk%20Factors%20for%20Suicide%20and%20Suicidal%20Behaviors_handout.pdf [Online]. Available: Accessed Jan 18th 2021.

- Amstadter A.B., Begle A.M., Cisler J.M., Hernandez M.A., Muzzy W., Acierno R. Prevalence and correlates of poor self-rated health in the United States: the national elder mistreatment study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2011;18:615–623. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ca7ef2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee D., Kosagisharaf J.R., Rao T.S.S. ‘The dual pandemic’ of suicide and COVID-19: a biopsychosocial narrative of risks and prevention. Psychiatr. Res. 2021;295:113577. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendau A., Petzold M.B., Pyrkosch L., Maricic L.M., Betzler F., Rogoll J., Gross J., Ströhle A., Plag J. Associations between COVID-19 related media consumption and symptoms of anxiety, depression and COVID-19 related fear in the general population in Germany. Eur. Arch. Psychiatr. Clin. Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1007/2Fs00406-020-01171-6. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn M.J., Babor T.F., Kranzler H.R. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1995;56:423–432. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-sills L., Stein M.B. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J. Trauma Stress. 2007;20:1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC injury prevention & control WISQARS-web-based injury statistics query and reporting system. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html [Online]. Available: Accessed Dec 21st 2020.

- Chochinov H., Hack T., Hassard T., Kristjanson L.J., Mcclement S., Harlos M. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;23:5520–5525. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codagnone C., Bogliacino F., Gomez C., Charris R., Montealegre F., Liva G., Lupianez-villanueva F., Folkvord F., Veltri G.A. Assessing concerns for the economic consequence of the COVID-19 response and mental health problems associated with economic vulnerability and negative economic shock in Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. PloS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler M., Lane R.I., Petrosky E., Wiley J.F., Christensen A., Njai R., Weaver M.D., Robbins R., Facer-childs E.R., Barger L.K., Czeisler C.A., Howard M.E., Rajaratnam S.M.W. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020;69:1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend B., Turner J.B., Turse N.A., Adams B.G., Koenen K.C., Marshall R. The psychological risks of Vietnam for U.S. veterans: a revisit with new data and methods. Science. 2006;313:979–982. doi: 10.1126/science.1128944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen E., Lanier M., Montgomery A.E., Strickland S., Wagner H.R., Tsai J. Financial strain and suicide attempts in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2020;189:1266–1274. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwaa146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettman C., Abdalla S.M., Cohen G.H., Sampson L., Vivier P.M., Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti V.J., Anda R.F., Nordenberg D., Williamson D.F., Spitz A.M., Edwards V., Koss M.P., Marks J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogle B., Tsai J., Mota N., Harpaz-rotem I., Krystal J., Southwick S.M., Pietrzak R.H. The national health and resilience in veterans study: a narrative review and future directions. Front. Psychiatr. 2020;11:538218. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.538218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geier T., Hunt J.C., Hanson J.L., Heyrman K., Larsen S.E., Brael K.J., Deroon-cassini T.A. Validation of abbreviated four- and eight-item versions of the PTSD checklist for DSM-5 in a traumatically injured sample. J. Trauma Stress. 2020;33:218–226. doi: 10.1002/jts.22478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbi S., Plomecka M.B., Ashraf Z., Radziński P., Neckels R., Lazzeri S., Dedić A., Bakalović A., Hrustić L., Skórko B., Haghi S.K., Rodriguez-pinto L., Alp A.B., Jabeen H., Waller V., Shibli D., Behnam M.A., Arshad A.H., Barańczuk-turska Z., Haq Z., Qureshi S.U., Jawaid A. Worsening of preexisting psychiatric conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatr. 2020;11:581426. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.581426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnel D., Appleby L., Arensman E., Hawton K., John A., Kapur N., O’connor R.C., Pirkis J., The covid-19 suicide prevention research collaboration Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:468–471. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada K., Fan X. The impact of COVID-19 on individuals living with serious mental illness. Schizophr. Res. 2020;222:3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy S.E., Gill T.M. Recovery from disability among community-dwelling older persons. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2004;291:1596–1602. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S., Luoma J.B., Bond F.K., Masuda A., Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006;44:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H., Curtin S.C., Warner M.W. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2018. Suicide Rates in the United States Continues to Increase. NCHS Data Brief, No 309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisel M., Flett G. Springer; New York, NY: 2014. Do Meaning in Life and Purpose in Life Protect against Suicidal Ideation Among Community-Residing Older Adults? [Google Scholar]

- Hkjc centre for suicide research and prevention Statistics: death & rate. 2020. https://csrp.hku.hk/statistics/ [Online]. Available: Accessed Jan 12th 2021.

- Hobfoll S. Traumatic stress: a theory based on rapid loss of resources. Anxiety. Res. 1991;4:187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Hooker S., Masters K. Purpose in life is associated with physical activity measured by accelerometer. J. Health Psychol. 2014;19:3–15. doi: 10.1177/1359105314542822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M.E., Waite L.J., Hawkley L.C., Cacioppo J.T. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res. Aging. 2004;26:655–672. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida R., Okada M. Effects of a firm purpose in life on anxiety and sympathetic nervous activity caused by emotional stress: assessment by psycho-physiological method. Stress and Health. Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress. 2006;22:275–281. [Google Scholar]

- John A., Pirkis J., Gunnel D., Appleby L., Morrissey J. Trends in suicide during the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;371:m4352. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan T.B., Gallagher M.W., Silvia P.J., Winterstein B.P., Breen W.E., Terhar D., Steger M.F. The curiosity and exploration inventory-II: development, factor structure, and psychometrics. J. Res. Pers. 2009;43:987–998. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig H., Berk L.S., Daher N.S., Pearce M.J., Bellinger D.L., Robins C.J., Nelson B., Shaw S.F., Cohen H.J., King M.B. Religious involvement is associated with greater purpose, optimism, generosity and gratitude in persons with major depression and chronic medical illness. J. Psychosom. Res. 2014;77:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B., LöWe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.-F., Li W., Deng H.-B., Wang L., Wang Y., Wang P.-H., Bo H.-X., Cao J., Wang Y., Zhu L.-Y., Yang Y., Cheung T., Ng C.H., Wu X., Xiang Y.-T. Prevalence of depression and its association with quality of life in clinically stable patients with COVID-19. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;275:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini C., Kaiser A.P., Smith B.N., Fiori K.L. Aging veterans' mental health and well-being in the context of COVID-19: the importance of social ties during physical distancing. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:S217–S219. doi: 10.1037/tra0000736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall M., Marshall E. 2012. Logotherapy Revisited: Review of the Tenets of Viktor E. Frankl's Logotherapy. Ottawa, Edward Marshall. [Google Scholar]

- Marx B.P., Schnurr P.P., Lunney C., Weathers F.W., Bovin M.J., Keane T.M. The brief inventory of psychosocial functioning (B-ipf) [Measurement instrument] 2019 https://www.ptsd.va.gov Available from. [Google Scholar]

- Mazza M., De lorenzo R., Conte C., Poletti S., Vai B., Bollettini I., Melloni E.M.T., Furlan R., Ciceri F., Rovere-querini P., Covid-19 biob outpatient clinic study group & benedetti, f. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;89:594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcclatchey K., Murray J., Chouliara Z., Rowat A. Protective factors of suicide and suicidal behavior relevant to emergency health care settings: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of post-2007 reviews. Arch. Suicide Res. 2019;23:411–427. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2018.1480983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccullough M.E., Emmons R.A., Tsang J. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002;82:112–127. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclean J., Maxwell M., Platt S., Harris F.M., Jepson R. Health and Community Care, Scottish Government Social Research. Scottish Government; 2008. Risk and Protective Factors for Suicide and Suicidal Behaviour: a Literature Review. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute Of Mental Health Intramural Research Program Mood Spectrum Collaboration & Child Mind Institute Of The Nys Nathan S. Kline Institute For Psychiatric Research The CoRonavIruS health impact survey (CRISIS) 2020. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/dr2/CRISIS_Adult_Self-Report_Baseline_Current_Form_V0.3.pdf [Online]. Available: Accessed Jan 11th 2021.

- Niederkrotenthaler T., Gunnel D., Arensman E., Pirkis J., Appleby L., Hawton K., John A., Kapur N., Khan M., O’connor R.C., Platt S., The international covid-19 suicide prevention research collaboration Suicide research, prevention, and COVID-19: towards a global response and the establishment of an international research collaboration. Crisis. 2020;41 doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A., Bagge C.L., Gutierrez P.M., Konick L.C., Kooper B.A., Barrios F.X. The suicidal behaviors questionnaire revised (SBQ-R): validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment. 2001;8:443–454. doi: 10.1177/107319110100800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa-de silva C. In the eyes of others: loneliness and relational meaning in life among Japanese college students. Transl. Psychiatry. 2020;57:623–634. doi: 10.1177/1363461519899757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz C., Mascialino G., Adana-díaz L., Rodriguez-lorenzana A., Simbana-rivera K., Gomez-barreno L., Troya M., Paez M.I., Cardenas J., Gerstner R.M., Ortiz-prado E. Anxiety and depression in patients with confirmed and suspected COVID‐19 in Ecuador. Psychiatr. Clin. Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1111/pcn.13106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce M., Hope H., Ford T., Hatch S., Hotopf M., John A., Kontopantelis E., Webb R., Wessely S., Mcmanu S., Abel K.M. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:883–892. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce M., Mcmanus S., Jessop C., John A., Hotopf M., Ford T., Hatch S., Wessely S., Abel K.M. Says who? The significance of sampling in mental health surveys during COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7:567–568. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30237-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak R., Tsai J., Kirwin P.D., Southwick S.M. Successful aging among older veterans in the United States. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2014;22:551–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M., Forstmeier S. Effects of reminiscence interventions on psychosocial outcomes: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment. Health. 2012;16:541–558. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.651434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger M., Stanley I.H., Joiner T.E. Suicide mortality and corona virus disease 2019 - a perfect storm? JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:1093–1094. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier M.F., Carver C.S., Bridges M.W. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a re-evaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg S.E., Schnetzer L.W., Buchanan E.M. The purpose in life test-short form: development and psychometric support. J. Happiness Stud. 2010;20:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid Z., Kalayanamitra R., Mcclafferty B., Kepko D., Ramgobin D., Patel R., Aggarwal C., Vunnam R., Sahu N., Bhatt D., Jones K., Golamari R., Jain R. COVID-19 and older adults: what we know. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020;68:926–929. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffler J., Joiner T., Sachs-ericsson N. The interpersonal and psychological impacts of COVID-19 on risk for late-life suicide. Gerontol. 2020 doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa103. gnaa123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM: Int. J. Med. 2020;113:707–712. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne C.D., Stewart A.L. The MOS social support survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus E., Norman S.B., Tripp J.C., Pitts M., Pietrzak R.H. Purpose in life and conscientiousness protect against the development of suicidal ideation in U.S. military veterans with PTSD and MDD: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Chronic Stress. 2019;3 doi: 10.1177/2470547019872172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z., Mcdonnell D., Wen J., Kozak M., Abbas J., Šegalo S., Li X., Ahmad J., Cheshmehzangi A., Cai Y., Yang L., Xiang Y.-T. Mental health consequences of COVID-19 media coverage: the need for effective crisis communication practices. Glob. Health. 2021;17:4. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00654-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department Of Veterans Affairs Office Of Mental Health And Suicide Prevention National veteran suicide prevention annual report. 2020. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2020/2020_National_Veteran_Suicide_Prevention_Annual_Report_508.pdf [Online]. Available: Accessed Jan 7th 2021.

- Vahia I., Jeste D.V., Reynolds C.F. Older adults and the mental health effects of COVID-19. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;324:2253–2254. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van orden K., Witte T.K., Cukrowicz K.C., Braithwaite S., Selby E.A., Joiner T.E. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol. Rev. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van reekum C., Urry H.L., Johnstone T., Thurow M.E., Frye C.J., Jackson C.A., Schaefer H.S., Alexander A.L., Davidson R.J. Individual differences in amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex activity are associated with evaluation speed and psychological well-being. J. Cognit. Neurosci. 2007;19:237–248. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vespa J. American Community Survey Reports. U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2020. Those Who Served: America's Veterans from World War II to the War on Terror. [Google Scholar]

- Villa V., Harada N.D., Washington D., Damron-rodriguez J. The health and functional status of U.S. veterans aged 65+: implications for VA health programs serving an elderly, diverse veteran population. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2003;18:108–116. doi: 10.1177/106286060301800304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman I. The impact of epidemic, war, prohibition and media on suicide: United States, 1910-1920. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 1992;22:240–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wathelet M., Duhem S., Vaiva G., Baubet T., Habran E., Veerapa E., Debien C., Molenda S., Horn M., Grandgenevre P., Notredame C.-E., D’hondt F. Factors associated with mental health disorders among university students in France confined during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F., Litz B., Keane T., Palmieri P., Marx B., Scnurr P. The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) 2013. http://www.ptsd.va.gov [Online]. Available: Scale available at: from the National Center for PTSD at. Accessed March 1st, 2021.

- Weathers F., Blake D.D., Schnurr P.P., Kaloupek D.G., Marx B.P., Keane T.M. The life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5) 2013. www.ptsd.va.gov Instrument available from the National Center for PTSD at. [Online]. [Accessed March 1st, 2021]

- Wiechers I., Karel M.J., Hoff R., Karlin B.E. Growing use of mental and general health care services among older veterans with mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2015;66:1242–1244. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson V., Stevelink S.A.M., Greenberg K., Greenberg N. Prevalence of mental health disorders in elderly US military veterans: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2018;26:534–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H., Chen J.H., Xu Y.F. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e21. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30090-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip P., Cheung Y.T., Chau P.H., Law Y.W. The impact of epidemic outbreak: the cause of several acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and suicide among older adults in Hong Kong. Crisis. 2010;31:86–92. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Zhang D., Fang J., Wan Y., Tao F., Sun Y. Assessment of mental health of Chinese primary school students before and after school closing and opening during the covid-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]