The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has been at the forefront in leading the transition from traditional fee-for-service payment to payment that is value-based. CMS defines value-based care as ‘paying for health care services in a manner that directly links performance to cost, quality, and the patient’s experience of care.’1 Value-based care emphasizes improving patient’s quality of life, increasing adherence to care plans, and integrating and coordinating care more effectively. More recently, CMS has responded to the complexity of Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) reporting by developing MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) as a revised framework. MVPs will identify an aligned set of specific cost measures, quality measures, and improvement activities that are important to the clinical practice of the clinician being evaluated, along with a foundational layer of measures that applies across all MVPs. This layer will include promoting interoperability measures (certified EHR technology use), and administrative claims-based quality measures focused on population health. In addition to better assessing the value of care, the design of MVPs better aligns with alternative payment models (APMs) to facilitate clinicians transitioning to such programs. For emergency clinicians, an emergency medicine-specific MVP will seek to bring value-based care to emergency care through specialty-specific quality measures. The current evolution of CMS payment systems will have enormous impact on emergency medicine, so it is important that emergency clinicians remain actively involved in the process. To that end, this article proposes several areas of opportunity for the development and inclusion of metrics particularly relevant to emergency clinicians.

Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS)

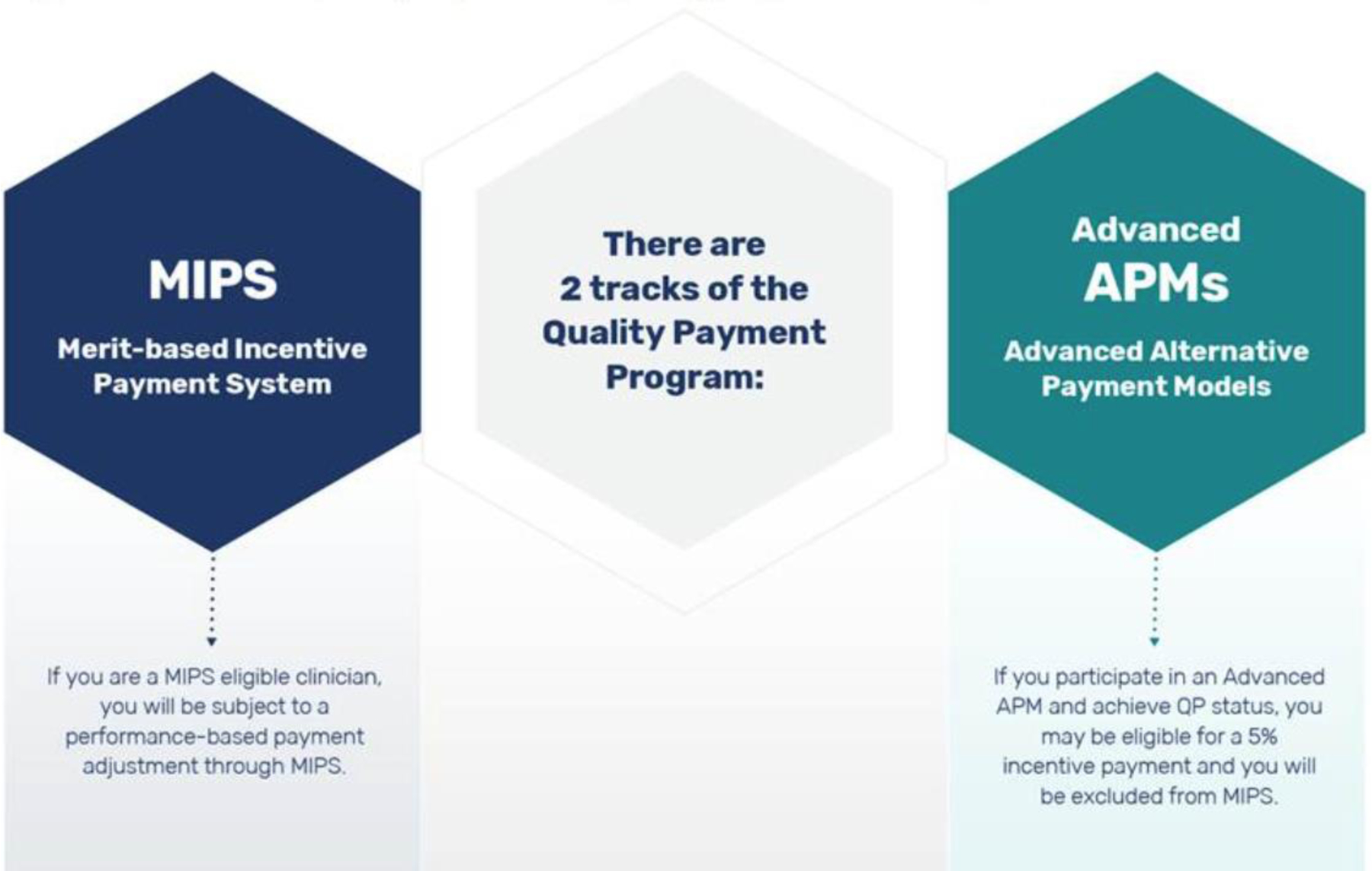

Enacted by Congress in 2015, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) created the Quality Payment Program (QPP), a new clinician payment program overseen by CMS advancing the transition to value-based care.2 Clinicians have two tracks to choose from in the QPP, Advanced APMs or MIPS (Figure 1), and factors such as practice size, specialty, location, or patient population may influence this choice. APMs are payment approaches that provide incentives to clinicians for delivering high-quality, high-value care. Advanced APMs are a subset of APMs that are value-based payment models meeting minimum requirements for the use of electronic health record technology, payment based on quality measurement performance, and the level of financial risk placed on clinicians. MIPS was designed to tie clinician payments to quality care, drive improvement in health outcomes, and reduce the cost of care. Of the two tracks, most emergency clinicians participate in the MIPS track of QPP. MIPS includes four performance categories: quality, cost, improvement activities, and promoting interoperability (Figure 2). An overall weighted composite score is generated and translated to an upward, downward, or neutral payment adjustment for the reporting individual clinician or group. Performance in 2020 will impact payments in calendar year 2022, with adjustments ranging between −9 and a positive adjustment that is determined each year in accordance with a statutory formula.3

Figure 1.

Transition to value-based care components through the Quality Payment Program within MACRA

Abbreviations: APMs, alternative payment models; MACRA, Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act; MIPS, Merit-based Incentive Payment System; QP, qualifying participant

Figure 2.

2021 Traditional MIPS performance categories and weights

Abbreviations: MIPS, Merit-based Incentive Payment System

MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs)

In the current structure of MIPS, CMS received feedback from stakeholders that reporting requirements are confusing and there is complexity and burden when reporting measures and activities.4 The quality measures included in MIPS, while numerous, were included to account for diverse clinician practices, and allowed choice and flexibility for clinicians in reporting quality metrics. In the 2020 Proposed Rule for the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS),5 CMS identified MVPs as a new framework to align reporting of quality metrics with cost metrics, to further incentive value-based care. Since its proposal, CMS has received feedback and worked closely with clinicians, patients, specialty societies, and other stakeholders to collaborate on MVP development. This new framework for the program is intended to reduce quality measure reporting requirements, moving away from siloed activities and towards a set of cost and quality measures clinically related to one another. In an example proposed by CMS, all clinicians, regardless of specialty, would also report on foundational measures related to promoting interoperability, while allowing quality, improvement activity, and cost measures to vary by specialty.2

Within a specialty- or condition-specific MVP, clinicians would then report on fewer quality measures. CMS would calculate cost and population health measures, related to the MVP a clinician chooses. Overall, the new MVP framework aims to simplify the MIPS program, help clinicians prioritize quality care, and further align reporting to other value-based models including APMs.4 Given the concerns noted by clinicians with the implementation of MVPs during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, CMS plans a phased-in implementation to start in the 2022 performance year.

The Current State of Emergency Medicine Measures

The transition to MVPs for emergency clinicians will require a concerted effort by involved parties to identify current measures and develop new measures that are applicable, feasible, reliable, and able to be calculated at the individual clinical or group level. There are currently 219 measures within the quality performance category, with only 12 relating specifically to the practice of emergency medicine. CMS has identified quality measures in emergency medicine as a significant gap area and need for further measure development.2,6 The majority of the measures are identified as process measures,7 or what action a clinician performs. Outcome measures assess the effect of the health service or intervention on the health of patients. To date, the focus of quality measurement development has been on developing process measures for specific conditions, such as ordering of lactate for an emergency department patient presenting with sepsis, instead of a focus on outcome measures in the ED setting.8 Aside from the measurement gaps in quality, additional gaps in cost measures for episodic care have been identified, particularly given difficulties in measure development and accurately attributing clinicians to patients’ outcomes and costs.9,10 With measure limitations present regarding quality and cost, measurement gaps can be anticipated in the development of emergency medicine-specific MVPs.

Emergency Medicine MVP Priorities

Designed to address measurement gaps and reduce burden, the Meaningful Measures 2.0 initiative launched by CMS in 2017 has identified high priority areas for future measure consideration, including the use of aligned measures that advance innovative payment structures, accelerate the transition to fully electronic measures, and improve the collection and integration of the patient voice using patient reported outcome measures (PROMs).11

With those priorities identified by the Meaningful Measures 2.0 initiative and believed to be central to quality improvement, two key areas to be considered for future emergency medicine-specific MVP development for measure development include care coordination and PROMs. Identifying and developing quality measures that address care coordination have, to date, proven to be difficult in the ED setting due to overall lack of incentives to spend time coordinating care.12 As evidence, a 2017 National Quality Forum (NQF) technical report on care coordination in emergency and unscheduled care, the report identified few measures targeting patients discharged from the ED.13 Conversely, CMS has developed readmission measures that promote high value care coordination upon hospital discharge. Emergency medicine-specific MVP development efforts may benefit from consulting existing care coordination measures and measure concepts to adapt communication, care transitions, or follow-up measures to the ED setting.

Second, there has been increasing emphasis on the importance of clinically meaningful PROMs for patients receiving acute unscheduled care.14,15 PROMs report on the perception of the care received uniquely from the patient’s perspective, focusing on the outcome as symptoms or health-related quality of life after a health care encounter or intervention.16–18 For example, CMS has developed PROMs for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) alongside related quality and cost measures.2 However, most PROMs are developed for settings outside of the ED and thus have limited applicability in measuring the quality of acute unscheduled care.19

Using PROMs within an emergency medicine-specific MVP to assess this population’s post-ED symptoms, functional status, and health-related quality of life may prove beneficial if linked to the acute unscheduled care episode, such as in the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Acute Unscheduled Care Model (AUCM), an emergency medicine-specific advanced APM. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services noted its interest in exploring how the concepts in AUCM could be incorporated into other APMs that the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation is developing.20 At the intersection of care coordination and patient experience, the AUCM focuses on optimizing disposition decisions for Medicare beneficiaries cared for by emergency clinicians.21,22 The alignment of the AUCM with an emergency medicine-specific MVP may benefit from the inclusion of PROMs in addition to proposed measure concepts assessing the percentage of cases with an unscheduled ED revisit, hospitalization, or death within 30 days.22

Aside from quality measures, the development and validation of episodic cost measures, the second necessary component to an emergency medicine-focused MVP, is often seen as the rate limiting factor in value-based care pathways.9 Thus far, MIPS has evaluated clinician cost using global cost measures and episode-based cost measures for specific conditions including acute care costs for common inpatient conditions such as pneumonia and COPD, and procedures such as STEMI with percutaneous coronary intervention and screening colonoscopy.2 Currently there are no emergency medicine-specific cost measures. The prioritization of developing episodic cost measures for an emergency medicine-specific MVP is integral to identifying high value care and rewarding clinicians for the delivery of care that avoids high-cost testing and hospital admissions.

CMS is asking for input from outside stakeholders to identify areas of opportunity and MVP concepts. Specifically, ACEP has convened an MVP Task Force including experts on MIPS, quality measurement, and value-based care. As a part of this process, relevant ACEP sections and committees were surveyed to provide input on available quality measures to be considered for an emergency medicine-specific MVP.23 Continued involvement of emergency clinicians will be essential within the MVP development and refinement process, as the process is iterative, including public comment before an MVP is finalized with proposed regulation.23

Conclusion

Innovations in value-based care will require stakeholders to play an integral role in the defining and development of quality and cost measures that are meaningful to their clinical practice. For emergency medicine, it is critical for emergency clinicians and leaders to be actively involved and lead in this area, as the health care system strives to deliver on better outcomes for patients through value-based care. A significant opportunity is present now for emergency clinicians to participate in the development of emergency medicine-specific MVPs.

Grant/Financial Support:

Dr. Gettel is supported by the Yale National Clinician Scholars Program and by CTSA Grant Number TL1 TR00864 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Venkatesh has been supported by the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation grant KL2 TR000140 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science of the NIH and currently receives support from the American Board of Emergency Medicine National Academy of Medicine Anniversary Fellowship. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation or approval of the manuscript. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Health and Human Services or its components.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:

Dr. Venkatesh receives support from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for the development of hospital and healthcare quality measures and rating systems.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Meetings:

This work has not been presented at a meeting.

References:

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Value Based Care. Available at: https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/nursing/meetings/2018/nacnep-sept2018-CMS-Value-Based-Care.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2020.

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality Payment Program. Available at: https://qpp.cms.gov/about/qpp-overview. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- 3.American College of Emergency Physicians. Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Available at: https://www.acep.org/administration/quality/mips/. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs). Available at: https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/mips-value-pathways. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Physician Fee Schedule. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched. Accessed August 9, 2020.

- 6.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2020. Annual Call for Quality Measures Fact Sheet. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2020-mips-call-quality-measure-overview-fact-sheet.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- 7.Donabedian A The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuur JD, Hsia RY, Burstin H, et al. Quality measurement in the emergency department: past and future. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(12):2129–2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liao JM, Miller SC, Navathe AS. To succeed, MIPS value pathways need more episodic cost measures. Health Affairs Blog, November 14, 2019. DOI: 10.1377/hblog20191107.686469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiler JL, Beck D, Asplin BR, et al. Episodes of care: is emergency medicine ready? Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(5):351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Meaningful Measures 2.0: Moving from measure reduction to modernization. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/meaningful-measures-20-moving-measure-reduction-modernization. Accessed March 28, 2021.

- 12.Katz EB, Carrier ER, Umscheid CA, et al. Comparative effectiveness of care coordination interventions in the emergency department: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(1):12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Quality Forum. Care Coordination Measures: 2016–2017 Technical Report. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samuels-Kalow ME, Rhodes KV, Henien M, et al. Development of a patient-centered outcome measure for emergency department asthma patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(5):511–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meisel ZF, Carr BG, Conway PH. From comparative effectiveness research to patient-centered outcomes research: integrating emergency care goals, methods, and priorities. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(3):309–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaillancourt S, Seaton MB, Schull MJ, et al. Patients’ perspectives on outcomes of care after discharge from the emergency department: a qualitative study. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(5):648–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Quality Forum. Patient Reported Outcomes (PROs) in Performance Measurement. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothman ML, Beltran P, Cappelleri JC, et al. Patient-reported outcomes: conceptual issues. Value Health. 2007;10 Suppl 2:S66–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institutes Health. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Available at: https://commonfund.nih.gov/promis/tools. Accessed August 9, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.The Secretary of Health and Human Services. Comments and recommendations of the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee (PTAC). Available at: https://downloads.cms.gov/files/ptac-hhssecresponse-sep18-dec18.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- 21.Baehr A, Nedza S, Bettinger J, et al. Enhancing appropriate admissions: an advanced alternative payment model for emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(5):612–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American College of Emergency Physicians. Empowering emergency medicine through the Acute Unscheduled Care Model. Available at: https://www.acep.org/globalassets/new-pdfs/advocacy/the-aucm-framework-issue-brief_1.29.201.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2020.

- 23.Davis J Paving the way towards value-based care: ACEP submits an MIPS Value Pathway (MVP) proposal to CMS. Available at: https://www.acep.org/federal-advocacy/federal-advocacy-overview/regs--eggs/regs--eggs-articles/regs---eggs---february-25-2021/. Accessed March 1, 2021.