Abstract

Objective

Central nervous system involvement in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been increasingly reported. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the incidence of radiologically demonstrated neurologic complications and detailed neuroimaging findings associated with COVID-19.

Materials and Methods

A systematic literature search of MEDLINE/PubMed and EMBASE databases was performed up to September 17, 2020, and studies evaluating neuroimaging findings of COVID-19 using brain CT or MRI were included. Several cohort-based outcomes, including the proportion of patients with abnormal neuroimaging findings related to COVID-19 were evaluated. The proportion of patients showing specific neuroimaging findings was also assessed. Subgroup analyses were also conducted focusing on critically ill COVID-19 patients and results from studies that used MRI as the only imaging modality.

Results

A total of 1394 COVID-19 patients who underwent neuroimaging from 17 studies were included; among them, 3.4% of the patients demonstrated COVID-19-related neuroimaging findings. Olfactory bulb abnormalities were the most commonly observed (23.1%). The predominant cerebral neuroimaging finding was white matter abnormality (17.6%), followed by acute/subacute ischemic infarction (16.0%), and encephalopathy (13.0%). Significantly more critically ill patients had COVID-19-related neuroimaging findings than other patients (9.1% vs. 1.6%; p = 0.029). The type of imaging modality used did not significantly affect the proportion of COVID-19-related neuroimaging findings.

Conclusion

Abnormal neuroimaging findings were occasionally observed in COVID-19 patients. Olfactory bulb abnormalities were the most commonly observed finding. Critically ill patients showed abnormal neuroimaging findings more frequently than the other patient groups. White matter abnormalities, ischemic infarctions, and encephalopathies were the common cerebral neuroimaging findings.

Keywords: COVID-19, Neuroimaging, Computed tomography, Magnetic resonance imaging, Meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Following the widespread global outbreak of the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in December 2019 [1], the World Health Organization designated coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a global pandemic. COVID-19 has been shown to have multiorgan manifestations. Specifically, central nervous system (CNS) involvement has been increasingly reported. Although the exact pathophysiology remains controversial [2,3], neurologic complications can have a striking impact on patient management. Indeed, when ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke develops, patients should undergo dedicated treatment (similar to patients without COVID-19) as well as require treatment for infection control [4,5]. Management of encephalopathy associated with COVID-19 is also challenging, as patients with encephalopathy have a longer hospitalization period, worse functional impairment, and higher 30-day mortality rate [6].

Therefore, it is important for clinicians to identify the number of patients with neuroradiological manifestations during hospitalization and understand how these may appear. Many case studies have recently been published [7,8,9,10,11,12], which can be analyzed to better understand CNS involvement in COVID-19. Several relevant meta-analyses have recently been published, but most of the studies merely focused on clinical manifestations of COVID-19 (e.g., headache, smell disturbances, dizziness) [13,14,15,16,17]. One metaanalysis focused on neuroimaging findings of COVID-19 [18], but only four types of neuroimaging findings were evaluated (i.e., cerebral infarction, cerebral microhemorrhages, intracranial hemorrhage, and encephalitis/encephalopathy). In addition, the cohort-based outcomes of all COVID-19 patients, not just the neuroimaging cohort, were evaluated.

Herein, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the incidence of radiologically proven neurologic complications and detail the neuroimaging findings associated with COVID-19.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) [19].

Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

A literature search of the MEDLINE/PubMed and EMBASE databases was conducted using pertinent MeSH or Emtree terms with common keywords for relevant articles until September 17, 2020. The search terms were as follows: ((COVID-19) OR (coronavirus) OR (SARS-CoV-2) OR (2019-nCoV)) AND ((brain) OR (neuro) OR (neuroimaging) OR (neurologic*) OR (nervous system) OR (olfactory)) AND ((magnetic resonance imaging) OR (MR imaging) OR (MRI)). The search was not limited by language, human or animal studies, or publication dates.

After eliminating duplicates, the articles were screened based on their titles and abstracts. The full article texts were then assessed according to the following eligibility criteria: 1) population: patients with COVID-19; 2) index test: brain CT or MRI conducted during hospitalization or admission to the emergency department due to COVID-19; 3) comparator(s)/control: not applicable; 4) outcomes: neuroimaging findings associated with COVID-19; and 5) study design: not limited. We excluded studies that met any of the following criteria: 1) review; 2) case reports or case series including fewer than 10 patients; 3) guidelines; 4) letters without original data, editorials, reply, corrections, and comments; 5) animal studies; 6) study protocol; and 7) studies with partially overlapping patient cohorts (for studies with overlapping study populations, the study with the largest population was selected). The literature search and criteria application were conducted independently by two authors (with 3 and 7 years of experience in performing systematic reviews and meta-analyses, respectively). Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

A standardized extraction form prepared in Microsoft Excel was used to obtain the following information from the selected studies: 1) study characteristics: study location, institution, study period, and study design (prospective vs. retrospective; multicenter vs. single-center; consecutive enrollment); 2) patient characteristics: sample size, inclusion criteria for each study, number of patients who underwent neuroimaging, types of neuroimaging studies (CT and/or MRI), and proportion of critically ill patients; 3) cohort-based outcomes: number of all COVID-19 patients in each hospital cohort, number of patients with neurologic symptoms, number of patients with neuroimaging data, number of patients with any abnormal neuroimaging findings, and number of patients with neuroimaging findings related to COVID-19; and 4) detailed neuroimaging findings. Neuroimaging findings were considered not related to COVID-19 if they were likely chronic lesions, such as cavernoma, chronic infarcts, known white matter lesions from multiple sclerosis, white matter lesions of small vessel disease, and microbleeds associated with chronic infarction. The spectrum of abnormal neuroimaging findings was classified into several categories, including white matter abnormalities, gray matter abnormalities, encephalopathy (regardless of white/gray matter involvement), cerebral microbleeds, intracranial hemorrhage, olfactory bulb abnormality, cranial neuropathy other than olfactory nerves, and others. The quality of evidence in the included studies was independently assessed by two authors using the US National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment of Case Series Studies tool [20]. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

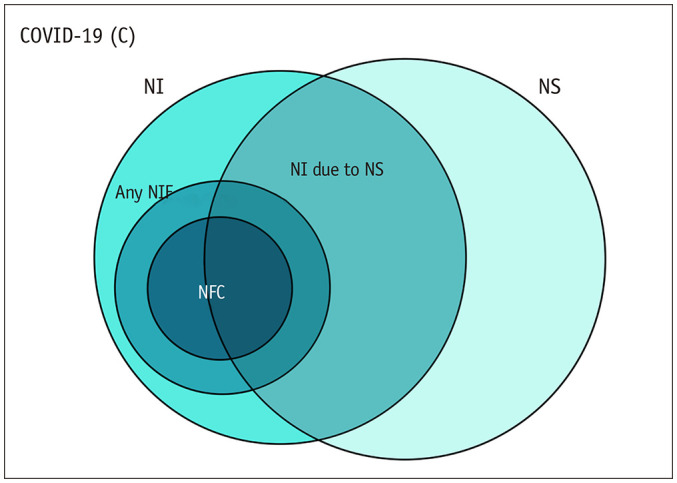

The cohort-based outcomes were as follows: 1) proportion of patients with neurologic symptoms among all COVID-19 patients; 2) proportion of patients who underwent neuroimaging examinations among patients with neurological symptoms; 3) proportion of patients underwent neuroimaging examinations among all patients; 4) proportion of patients with neuroimaging findings among patients underwent neuroimaging examinations; 5) proportion of patients with neuroimaging findings related to COVID-19 among patients underwent neuroimaging examinations; and 6) proportion of patients with neuroimaging findings related to COVID-19 among all patients (Fig. 1). The proportion of patients showing specific neuroimaging findings among patients who underwent neuroimaging examinations was also an outcome of interest. Meta-analytic pooling was performed based on the inverse variance method for calculating weights, and pooled estimates with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were determined using DerSimonian-Laird random-effects modeling. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using Q tests and I2 statistics, with I2 > 50% indicating the presence of heterogeneity [21,22,23]. Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots and Egger's test when the number of analyzed studies was 10 or more [24,25].

Fig. 1. Venn diagram illustrating the cohort-based outcomes used in this study.

1) proportion of patients with NS among all COVID-19 patients (NS/C); 2) proportion of patients with NI among patients with NI-NS; 3) proportion of patients who underwent NI among all patients assessed (NI/C); 4) proportion of patients with any NI findings among the patients who underwent NI (NF/NI); 5) proportion of patients with NFC among the patients who underwent NI (NFC/NI); 6) proportion of patients with NFC among all patients assessed (NFC/C). COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019, NF = NI findings, NFC = NF related to COVID-19, NI = neuroimaging, NS = neurologic symptoms

We conducted a subgroup analysis of critically ill COVID-19 patients. Patients were considered critically ill if they met any of the following criteria: 1) respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, 2) shock, or 3) combined failure of other organs requiring intensive care unit (ICU) monitoring [26]. A meta-regression analysis was performed to determine whether COVID-19 severity was a source of heterogeneity. In addition, a subgroup analysis including studies using only MRI as an imaging modality was performed. Two-sided tests were used, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed by one of the authors using R software (version 3.1.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing) with the “meta” and “metafor” packages.

RESULTS

Literature Search

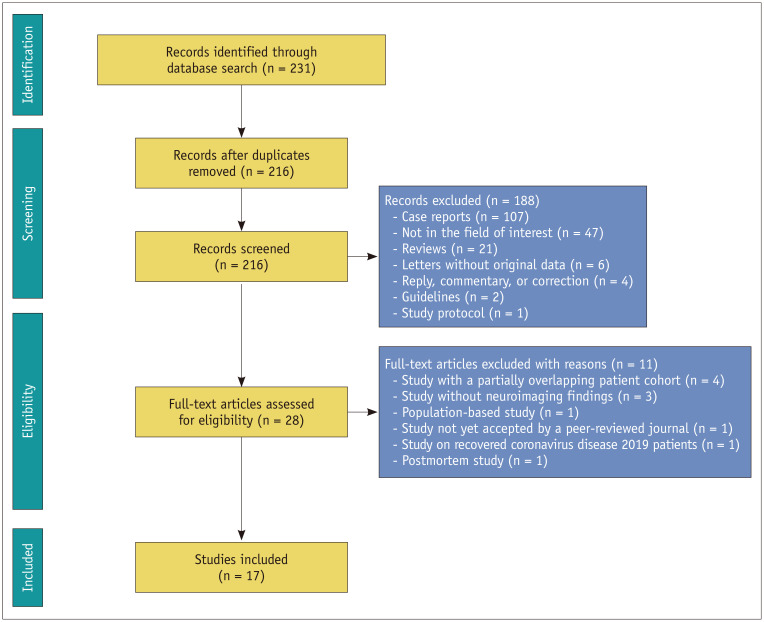

A flowchart of the publication selection process is presented in Figure 2. A total of 216 non-duplicate studies were identified. Of these, 188 articles were excluded after title and abstract review, and 11 studies were further excluded for the following reasons: 1) studies with partially overlapping patient cohorts (n = 4); 2) studies without neuroimaging findings (n = 3); 3) population-based study (n = 1); 4) study not yet accepted by a peer-reviewed journal (n = 1); 5) study on recovered COVID-19 patients (n = 1); and 6) postmortem study (n = 1). Consequently, the analysis included a total of 17 studies comprising 1394 COVID-19 patients who underwent brain CT/MRI during hospitalization or admission in the emergency department due to COVID-19 met the eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis.

Fig. 2. Flow chart depicting the study selection process.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

The detailed study and patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. All studies were conducted between February and June 2020 in the US [9,11,12,27,28,29,30,31] and Europe [7,8,10,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Except for the study by Eliezer et al. [34], all studies were retrospective. Three included studies focused on specific symptoms of the diseases, including olfactory function loss [34], acute ischemic stroke [29], and cerebrovascular disease (e.g., cerebral ischemia, intracerebral hemorrhage, and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome-like leukoencephalopathy) [35]. Seven studies analyzed only brain MRI findings [8,27,28,30,33,34,36], while the other 10 also analyzed CT findings [7,9,10,11,12,29,31,32,35,37]. Data on COVID-19 severity were available in eight studies [9,29,30,31,32,33,36,37]; of those, four included only critically ill COVID-19 patients who required ICU care [30,31,32,36]. The quality of these studies was good (n = 12) [7,8,9,11,12,28,29,32,33,34,35,37] or fair (n = 5) [10,27,30,31,36] (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of the 17 Included Studies.

| Study | Location | Study Period | Study Design | Patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective | Multicenter | Consecutive Enrollment | Inclusion Criteria | No. of Patients with Neuroimaging | Neuroimaging Studies | Critically Ill Patients (%) | |||

| Abenza-Abildúa et al. [32] | Spain | Jan. 1, 2020 to June 1, 2020 | No | No | Yes | COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU with neurologic symptoms | 30 | CT and/or MRI | 30/30 (100) |

| Agarwal et al. [27] | US | Mar. 1, 2020 to May 10, 2020 | No | No | Not reported | COVID-19 patients who underwent MRI | 115 | MRI | - |

| Chougar et al. [33] | France | Mar. 23, 2020 to May 7, 2020 | No | No | Yes | COVID-19 patients with neurologic symptoms referred for brain MRI | 73 | MRI | 35/73 (48) |

| Eliezer et al. [34] | France | Mar. 23, 2020 to Apr. 27, 2020 | Yes | No | Not reported | COVID-19 patients presenting with olfactory function loss | 20 | MRI | - |

| Freeman et al. [28] | US | Mar. 1, 2020 to June 18, 2020 | No | No | Yes | COVID-19 patients who underwent brain MRI | 59 | MRI | - |

| Grewal et al. [29] | US | Mar. 4, 2020 to May 9, 2020 | No | No | Yes | COVID-19 patients with acute ischemic stroke | 13 | CT and/or MRI | 8/13 (62) |

| Hernández-Fernández et al. [35] | Spain | Mar. 1, 2020 to Apr. 19, 2020 | No | No | Yes | COVID-19 patients with cerebrovascular disease | 23 | CT with/ without MRI | - |

| Kandemirli et al. [36] | Turkey | Mar. 1, 2020 to Apr. 18, 2020 | No | Yes | Not reported | COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU with neurologic symptoms referred for brain MRI | 27 | MRI | 27/27 (100) |

| Klironomos et al. [7] | Sweden | Mar. 2, 2020 to May 24, 2020 | No | No | Yes | COVID-19 patients who underwent neuroimaging | 185 | CT and/or MRI | - |

| Kremer et al. [8] | France | Mar. 16, 2020 to Apr. 9, 2020 | No | Yes | Not reported | COVID-19 patients with neurologic symptoms referred for brain MRI | 64 | MRI | - |

| Lin et al. [9] | US | Mar. 4, 2020 to May 9, 2020 | No | Yes | Yes | COVID-19 patients who underwent neuroimaging | 278 | CT and/or MRI | 92/278 (33) |

| Nawabi et al. [37] | Germany, Switzerland, France | Feb. 16, 2020 to May 19, 2020 | No | Yes | Yes | COVID-19 patients with intracranial hemorrhage | 18 | CT with/ without MRI | 15/18 (83) |

| Paterson et al. [10] | UK | Apr. 9, 2020 to May 15, 2020 | No | No | Not reported | COVID-19 patients with neurologic complications | 43 | CT and/or MRI | - |

| Radmanesh et al. [30] | US | Apr. 5, 2020 to Apr. 25, 2020 | No | No | Not reported | Critically ill COVID- patients with COVID-19-associated diffuse leukoencephalopathy and microhemorrhages | 27* | MRI | 27/27 (100) |

| Radmanesh et al. [11] | US | Mar. 1, 2020 to Mar. 31, 2020 | No | No | Yes | COVID-19 patients who underwent neuroimaging | 242 | CT and/or MRI | - |

| Scullen et al. [31] | US | Not reported † | No | No | Not reported | COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU with new-onset neurologic disease | 27 | CT and/or MRI | 27/27 (100) |

| Yoon et al. [12] | US | Mar. 3, 2020 to May 6, 2020 | No | No | Not reported | COVID-19 patients with acute neurologic symptoms referred for neuroimaging | 150 | CT and/or MRI | - |

*Although the authors finally included 11 patients who showed COVID-19-associated diffuse leukoencephalopathy and microhemorrhages, they reported neuroimaging findings of 27 patients who underwent brain MRI, †The authors included patients admitted to ICU on April 22, 2020. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019, ICU = intensive care unit

Neuroimaging Cohort

Four of the 17 included studies [31,32,33,36] (one study on all COVID-19 patients [33] and three studies on critically ill COVID-19 patients [31,32,36]) reported the proportion of patients with neurologic symptoms among all COVID-19 patients; the proportion of patients with neurologic symptoms ranged from 21.3–55.6%, with a meta-analytic pooled proportion of 32.4% (95% CI, 22.9–43.7%). Of those, neuroimaging studies were performed in 23.7–100% of patients (pooled proportion, 72.4% [95% CI, 36.0– 92.5%]), showing a high discrepancy across the studies.

Regardless of the presence of acute neurologic symptoms requiring neuroimaging, neuroimaging studies were performed in 2.1–55.6% of COVID-19 patients from each study population [7,9,11,12,27,28,31,32,33,36], with a meta-analytic pooled proportion of 9.7% (95% CI, 5.8–15.9%). No significant publication bias was observed (p = 0.820).

Among patients who underwent neuroimaging studies, 58.9–86.4% showed abnormal neuroimaging findings [27,28,31,32,33], with a meta-analytic pooled proportion of 73.6% (95% CI, 62.2–82.6%). After excluding neuroimaging findings possibly not related to COVID-19 or associated comorbidities, the pooled proportion decreased to 35.5% (95% CI, 24.4–48.3%). Consequently, 3.4% (95% CI, 1.4–8.2%) of all COVID-19 patients demonstrated abnormal neuroimaging findings related to COVID-19.

Abnormal Neuroimaging Findings

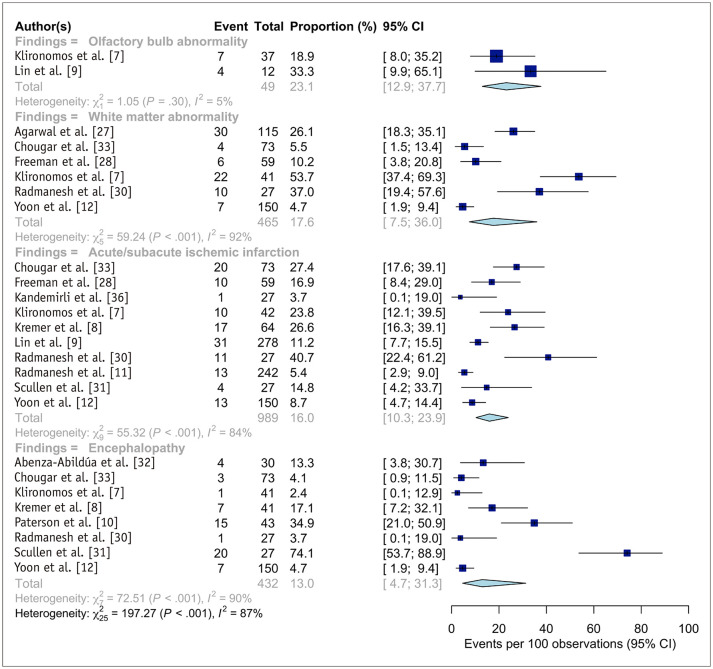

The abnormal neuroimaging findings of the included neuroimaging cohorts are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 3. Two studies reported the proportion of patients with olfactory bulb abnormalities [7,9], with these abnormalities showing the highest meta-analytic pooled proportion (23.1%; 95% CI, 12.9–37.7%). The most common cerebral neuroimaging finding was white matter abnormalities (17.6%; 95% CI, 7.5–36.0%), followed by acute/subacute ischemic infarction (16.0%; 95% CI, 10.3–23.9%), encephalopathy (13.0%; 95% CI, 4.7–31.3%), cerebral microbleeds (12.1%; 95% CI, 5.0–26.3%), and intracranial hemorrhage (7.8%; 95% CI, 3.7–16.0%). There was no significant publication bias in the pooled estimates of acute/subacute ischemic infarction (p = 0.725).

Table 2. Summary of Neuroimaging Findings in Patients with COVID-19.

| Neuroimaging Findings | Detailed Findings Included | No. of Studies | No. of Patients (%) | Meta-Analytic Proportion (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olfactory bulb abnormality | T2 hyperintensity in the olfactory bulbs/tracts | 2 | 11/49 (22) | 23.1 (12.9–37.7) | |

| White matter abnormality | White matter changes, leukoencephalopathy, multifocal enhancing white matter lesions, COVID-19-related disseminated leukoencephalopathy | 6 | 79/465 (17) | 17.6 (7.5–36.0)* | |

| Acute or subacute ischemic infarction | - | 10 | 130/989 (13) | 16.0 (10.3–23.9)* | |

| Encephalopathy (regardless of white/grey matter involvement) | COVID-19-associated encephalopathy, cytotoxic lesions of the corpus callosum, limbic encephalitis, acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy, miscellaneous encephalitis | 8 | 58/432 (13) | 13.0 (4.7–31.3)* | |

| Cerebral microbleeds | - | 8 | 107/983 (11) | 12.1 (5.0–26.3)* | |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | Intraparenchymal hemorrhage, subdural hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage | 6 | 47/766 (6) | 7.8 (3.7–16.0)* | |

| Others | Venous thrombosis, PRES, ADEM, seizure-related perfusion abnormalities, isolated perfusion abnormalities, metabolic abnormalities, leptomeningeal enhancement | 5 | 38/472 (8) | 7.4 (1.9–24.7)* | |

| Venous thrombosis | - | 2 | 3/57 (5) | 5.5 (1.8–15.6) | |

| PRES | - | 2 | 5/351 (1) | 1.6 (0.6–3.8) | |

| Grey matter abnormality | Abnormal basal ganglia signal, cortical T2 hyperintensity | 2 | 11/86 (13) | 10.2 (0.4–78.2) | |

| Cranial neuropathy other than olfactory nerves | T2 hyperintensity and/or enhancement in the optic (II), oculomotor (III), facial (VII), and vestibulocochlear nerves (VIII) | 3 | 6/371 (2) | 2.7 (0.6–11.5)* | |

We excluded neuroimaging findings not likely to be related to COVID-19, including cavernoma, chronic infarcts, known white matter lesions from multiple sclerosis, white matter lesions of small vessel disease, and microbleeds associated with chronic infarction. Neuroimaging findings were ordered from the top in the order of decreasing meta-analytic proportions. *The pooled proportion showed substantial heterogeneity (I2 > 50%). ADEM = acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, CI = confidence interval, COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019, PRES = posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome

Fig. 3. Forest plots representing the proportion of the patients with specific neuroimaging findings among the patients who underwent neuroimaging studies.

Pooled estimates with 95% CIs were determined using DerSimonian-Laird random-effects modeling. CI = confidence interval

Acute or subacute ischemic infarction was present in 168 patients in 13 studies [7,8,9,10,11,12,28,29,30,31,33,35,36]. Of those, data regarding Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification were available for 59 patients from three studies [9,29,35] The most common classification was cryptogenic (54%; 32/59), followed by cardioembolism (34%; 20/59), large artery atherosclerosis (5%; 3/59), other determined etiology (5%; 3/59), and small-vessel occlusion (2%; 1/59). Of the 79 patients with available infarction data, 35 (44%) had large vessel occlusion. Data on infarction territory were available for 24 patients from four studies [10,12,31,36]; the most common territory was the middle cerebral artery (46%; 11/24), followed by multiple territories (21%; 5/24), the posterior cerebral artery (17%; 4/24), the posterior-inferior cerebellar artery (8%; 2/24), and the watershed zone (8%; 2/24). Among the 30 patients for whom prognosis data were available, 14 (47%) showed favorable outcomes.

White matter abnormalities or encephalopathy were present in 120 patients from 11 studies [7,8,10,12,27,28,30,31,32,33,35]. Several characteristic forms were reported in 29 patients, including diffuse/disseminated leukoencephalopathy (n = 16), cytotoxic lesion of the corpus callosum (n = 5), acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy (n = 4), and limbic encephalitis (n = 4). Prognosis was only available in the study by Paterson et al. [10]. One patient with acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy initially underwent intravenous methylprednisolone, but her consciousness level decreased, and she subsequently underwent emergent craniectomy. She then received oral prednisolone 60 mg daily and 5 days of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and finally showed clinical improvement. Two patients with limbic encephalitis received IVIG and showed incomplete improvement.

Intracranial hemorrhage was present in 65 patients from seven studies [7,9,11,12,30,32,37]. Of those, data regarding the types of hemorrhage were available for 54 patients from six studies [7,9,12,30,32,37]. The most common type was intracerebral hemorrhage (44%; 24/54), followed by subarachnoid hemorrhage (35%; 19/54) and subdural hemorrhage (24%; 13/54) (some patients had multiple types of hemorrhage), with 13 patients showing an intraventricular extension of the hemorrhage.

Radiologic olfactory bulb abnormalities were present in 11 patients in two studies [7,9]. Lin et al. [9] reported an increased signal on postcontrast T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging in four of 12 patients, one of whom had documented anosmia. No abnormalities were reported along the olfactory cleft. Klironomos et al. [7] reported an increased signal on postcontrast T2 FLAIR images in seven of 37 patients (19%). The presence or absence of anosmia in these patients was not reported. Eliezer et al. [34] reported 20 COVID-19 patients with olfactory function loss, of whom 19 (95%) showed complete obstruction of the olfactory clefts on MRI. These findings were persistent at the 1-month follow-up in seven patients (35%), with a correlation between olfactory score and olfactory cleft obstruction. However, none of the patients showed olfactory bulb abnormalities.

Subgroup Analysis: Critically Ill Patients

The cohort-based results of subgroup analysis of critically ill patients, including four studies and 111 critically ill COVID-19 patients [30,31,32,36], are summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Compared to the other studies, the proportion of patients who underwent neuroimaging studies was significantly higher in studies on critically ill patients (22.7% vs. 6.8%; p = 0.027). In addition, the proportion of patients with abnormal neuroimaging findings related to COVID-19 among all patients evaluated in this study was significantly higher in critically ill patients (9.1% vs. 1.6%; p = 0.029). Other cohort-based outcomes did not show any significant differences.

The abnormal neuroimaging findings of critically ill patients are also summarized in Supplementary Table 2. Encephalopathy (22.2%) and acute or subacute ischemic infarction (17.2%) were the most common cerebral neuroimaging findings. The proportion of each neuroimaging finding in critically ill patients, including those with ischemic infarction, did not differ significantly.

Subgroup Analysis: MRI

The cohort-based results of subgroup analysis, including studies using only MRI as an imaging modality, are summarized in Supplementary Table 3.

The proportion of patients with abnormal neuroimaging findings related to COVID-19 among patients who underwent neuroimaging studies did not differ, whether only MRI was used or not (40.1% vs. 31.1%; p = 0.397). In contrast, the proportion of patients who underwent neuroimaging among the patients with neurological symptoms (37.1% vs. 98.3%; p < 0.001), the proportion of patients who underwent neuroimaging among all COVID-19 patients (3.4% vs. 18.5%; p < 0.001), and the proportion of patients with abnormal neuroimaging findings related to COVID-19 when the denominator was set to be all COVID-19 patients (0.9% vs. 8.4%; p = 0.002) was significantly lower when only MRI was used as an imaging modality. Regarding detailed neuroimaging findings, acute or subacute ischemic infarction was more frequently observed when only MRI was used as an imaging modality (24.4% vs. 11.0%; p = 0.011).

DISCUSSION

This meta-analysis of 17 studies reports that 9.7% of COVID-19 patients underwent neuroimaging studies and that 35.5% of them had neuroimaging findings associated with COVID-19. Consequently, 3.4% of COVID-19 patients undergoing neuroimaging demonstrated neuroimaging findings related to COVID-19. Olfactory bulb abnormality was the most common neuroimaging finding (23.1%). The predominant cerebral neuroimaging finding was white matter abnormality (17.6%), followed by acute/subacute ischemic infarction (16.0%), and encephalopathy (13.0%). Intracranial hemorrhage and cerebral microbleeds were observed in 7.8% and 12.1% of the patients, respectively. Critically ill patients underwent neuroimaging studies more frequently (22.7% vs. 6.8%; p = 0.027) and presented more frequent COVID-19-related neuroimaging findings when compared in all COVID-19 patients evaluated in this study (9.1% vs. 1.6%; p = 0.029). Although MRI was less frequently performed in COVID-19 patients (3.4% vs. 18.5%; p < 0.001), the proportion of patients with COVID-19-related abnormal neuroimaging findings was similar regardless of the imaging modality used.

Our results showed that COVID-19-related neuroimaging findings were more frequently observed in critically ill patients than the other patient groups. This finding may emphasize the role of neuroimaging in critically ill patients. Since neurologic deficits may be masked in critically ill patients due to decreased levels of consciousness, it may be necessary to actively perform neuroimaging studies in critically ill patients in whom neurologic complications are suspected.

In this study, there were no significant differences between the proportions of patients with ischemic infarction in studies that included only critically ill patients and other studies (17.2% vs. 15.1%; p = 0.617). This finding indicates that ischemic infarction may not occur due to the systemic inflammatory process accompanying acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and that it may be a consequence of the hypercoagulable state and thrombosis. Indeed, 44% of the patients with ischemic infarction in this study had large vessel occlusion, a proportion higher than that reported in the general population (24–46%) [38,39,40,41]. This observation has also been suggested in the existing literature; Kremer et al. [8] reported lower oxygen demand and ARDS in patients with ischemic infarction, while Beyrouti et al. [42] reported that all six patients with ischemic infarction in their study were in prothrombotic states and had large vessel occlusion. However, this evidence is insufficient to elucidate a causal relationship between ischemic infarction and hypercoagulability, and further investigation is required.

Another important neurological manifestation of COVID-19 is anosmia. Although the current meta-analysis included only two studies on anosmia, olfactory bulb abnormalities were relatively common, occurring in approximately 23.1% of patients who underwent neuroimaging. However, it remains controversial whether anosmia in COVID-19 occurs due to olfactory cleft congestion or direct olfactory nerve damage. SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to invade target cells through interactions between the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) protein and the S protein of the target cell [43,44]. SARS-CoV-2 may enter through the sustentacular cells of the olfactory epithelium (which express ACE2 receptors) [44], consequently causing structural changes in the olfactory bulb. However, among the 20 COVID-19 patients with anosmia investigated, Eliezer et al. [34] reported olfactory cleft obstruction in 95% of the cases but without any olfactory bulb abnormalities. Thus, it could be hypothesized that olfactory cleft obstruction occurs first, followed by the secondary involvement of the central olfactory pathway. However, further investigation is required to clarify this issue.

This study has several limitations. First, all studies, except one, were retrospective in their design, which confers a risk of selection bias. Second, the sample size was moderate and resulted in underpowered statistical analyses. Third, considerable between-study variability was observed in most of the study outcomes, which could have resulted from differences in cohort characteristics, regional spread of COVID-19, institutional policies, institutional neuroradiologists' perspectives, and neuroimaging study types and protocols. In particular, the proportion of patients among the COVID-19 patients who underwent neuroimaging was highly variable across the studies (23.7–100%). Although we performed a subgroup analysis of the studies that only used MRI, the substantial heterogeneity of our cohort could not be completely resolved. Fourth, the terms describing a specific neuroimaging finding (e.g., white matter change, leukoencephalopathy, COVID-19-related diffuse leukoencephalopathy) were heterogeneous across studies, complicating the meta-analytic pooling. Fifth, it is unclear how the authors concluded whether microbleeds were caused by COVID-19 or small vessel disease. Lastly, although we conducted the analysis after excluding chronic neuroimaging findings, it is difficult to guarantee that acute or subacute neuroimaging findings are directly associated with COVID-19. Nevertheless, our results may provide useful information for understanding the neuroimaging findings in COVID-19.

In conclusion, active neuroimaging studies are recommended in critically ill patients, considering the high proportion of patients presenting with neuroimaging findings related to COVID-19. The predominant cerebral neuroimaging finding was white matter abnormalities, followed by acute/subacute ischemic infarctions, and encephalopathies. Olfactory bulb abnormalities are also frequently observed in COVID-19 patients.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Chong Hyun Suh.

- Data curation: Pyeong Hwa Kim, Minjae Kim, Chong Hyun Suh.

- Formal analysis: Pyeong Hwa Kim, Chong Hyun Suh.

- Investigation: Pyeong Hwa Kim, Chong Hyun Suh.

- Methodology: Pyeong Hwa Kim, Chong Hyun Suh.

- Project administration: Pyeong Hwa Kim, Chong Hyun Suh.

- Resources: all authors.

- Software: Pyeong Hwa Kim, Chong Hyun Suh.

- Supervision: Chong Hyun Suh, Sang Joon Kim.

- Validation: Chong Hyun Suh.

- Visualization: Pyeong Hwa Kim.

- Writing—original draft: Pyeong Hwa Kim, Minjae Kim.

- Writing—review & editing: all authors.

Supplement

The Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2021.0127.

Quality Assessment of the 17 Included Studies

Results of Subgroup Analysis of Critically Ill Patients

Results of Subgroup Analysis Regarding Whether Only MRI Was Used as an Imaging Modality or Not

References

- 1.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zubair AS, McAlpine LS, Gardin T, Farhadian S, Kuruvilla DE, Spudich S. Neuropathogenesis and neurologic manifestations of the coronaviruses in the age of coronavirus disease 2019: a review. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1018–1027. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:683–690. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wira CR, Goyal M, Southerland AM, Sheth KN, McNair ND, Khosravani H, et al. Pandemic guidance for stroke centers aiding COVID-19 treatment teams. Stroke. 2020;51:2587–2592. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leira EC, Russman AN, Biller J, Brown DL, Bushnell CD, Caso V, et al. Preserving stroke care during the COVID-19 pandemic: potential issues and solutions. Neurology. 2020;95:124–133. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liotta EM, Batra A, Clark JR, Shlobin NA, Hoffman SC, Orban ZS, et al. Frequent neurologic manifestations and encephalopathy-associated morbidity in Covid-19 patients. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020;7:2221–2230. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klironomos S, Tzortzakakis A, Kits A, Öhberg C, Kollia E, Ahoromazdae A, et al. Nervous system involvement in coronavirus disease 2019: results from a retrospective consecutive neuroimaging cohort. Radiology. 2020;297:E324–E334. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kremer S, Lersy F, Anheim M, Merdji H, Schenck M, Oesterlé H, et al. Neurologic and neuroimaging findings in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective multicenter study. Neurology. 2020;95:e1868–e1882. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin E, Lantos JE, Strauss SB, Phillips CD, Campion TR, Jr, Navi BB, et al. Brain imaging of patients with COVID-19: findings at an academic institution during the height of the outbreak in New York City. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41:2001–2008. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paterson RW, Brown RL, Benjamin L, Nortley R, Wiethoff S, Bharucha T, et al. The emerging spectrum of COVID-19 neurology: clinical, radiological and laboratory findings. Brain. 2020;143:3104–3120. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radmanesh A, Raz E, Zan E, Derman A, Kaminetzky M. Brain imaging use and findings in COVID-19: a single academic center experience in the epicenter of disease in the United States. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41:1179–1183. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon BC, Buch K, Lang M, Applewhite BP, Li MD, Mehan WA, Jr, et al. Clinical and neuroimaging correlation in patients with COVID-19. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41:1791–1796. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Favas TT, Dev P, Chaurasia RN, Chakravarty K, Mishra R, Joshi D, et al. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of proportions. Neurol Sci. 2020;41:3437–3470. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04801-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collantes MEV, Espiritu AI, Sy MCC, Anlacan VMM, Jamora RDG. Neurological manifestations in COVID-19 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2021;48:66–76. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2020.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nazari S, Azari Jafari A, Mirmoeeni S, Sadeghian S, Heidari ME, Sadeghian S, et al. Central nervous system manifestations in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. 2021;11:e02025. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinzon RT, Wijaya VO, Buana RB, Al Jody A, Nunsio PN. Neurologic characteristics in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2020;11:565. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, Laurent S, Onur OA, Kleineberg NN, Fink GR, Schweitzer F, et al. A systematic review of neurological symptoms and complications of COVID-19. J Neurol. 2021;268:392–402. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10067-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi Y, Lee MK. Neuroimaging findings of brain MRI and CT in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2020;133:109393. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.109393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institutes of Health. Quality assessment tool for case series studies. Nhlbi.nih.gov Web site. [Accessed September 24, 2020]. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools.

- 21.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim KW, Lee J, Choi SH, Huh J, Park SH. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies evaluating diagnostic test accuracy: a practical review for clinical researchers-part II. Statistical methods of meta-analysis. Korean J Radiol. 2015;16:1175–1187. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2015.16.6.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee J, Kim KW, Choi SH, Huh J, Park SH. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies evaluating diagnostic test accuracy: a practical review for clinical researchers-part II. Statistical methods of meta-analysis. Korean J Radiol. 2015;16:1188–1196. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2015.16.6.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sterne JA, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic reviews in health care: investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323:101–105. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. Novel coronavirus pneumonia diagnosis and treatment plan (provisional 7th edition). Chinalawtranslate.com Web site. [Accessed March 22, 2021]. https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/en/coronavirus-treatment-plan-7/

- 27.Agarwal S, Jain R, Dogra S, Krieger P, Lewis A, Nguyen V, et al. Cerebral microbleeds and leukoencephalopathy in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Stroke. 2020;51:2649–2655. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freeman CW, Masur J, Hassankhani A, Wolf RL, Levine JM, Mohan S. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)-related disseminated leukoencephalopathy: a retrospective study of findings on brain MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:1046–1047. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grewal P, Pinna P, Hall JP, Dafer RM, Tavarez T, Pellack DR, et al. Acute ischemic stroke and COVID-19: experience from a comprehensive stroke center in Midwest US. Front Neurol. 2020;11:910. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radmanesh A, Derman A, Lui YW, Raz E, Loh JP, Hagiwara M, et al. COVID-19-associated diffuse leukoencephalopathy and microhemorrhages. Radiology. 2020;297:E223–E227. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scullen T, Keen J, Mathkour M, Dumont AS, Kahn L. Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19)-associated encephalopathies and cerebrovascular disease: the new Orleans experience. World Neurosurg. 2020;141:e437–e446. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abenza-Abildúa MJ, Ramírez-Prieto MT, Moreno-Zabaleta R, Arenas-Valls N, Salvador-Maya MA, Algarra-Lucas C, et al. Neurological complications in critical patients with COVID-19. Neurologia. 2020;35:621–627. doi: 10.1016/j.nrleng.2020.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chougar L, Shor N, Weiss N, Galanaud D, Leclercq D, Mathon B, et al. Retrospective observational study of brain MRI findings in patients with acute SARS-CoV-2 infection and neurologic manifestations. Radiology. 2020;297:E313–E323. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eliezer M, Hamel AL, Houdart E, Herman P, Housset J, Jourdaine C, et al. Loss of smell in patients with COVID-19: MRI data reveal a transient edema of the olfactory clefts. Neurology. 2020;95:e3145–e3152. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hernández-Fernández F, Sandoval Valencia H, Barbella-Aponte RA, Collado-Jiménez R, Ayo-Martín Ó, Barrena C, et al. Cerebrovascular disease in patients with COVID-19: neuroimaging, histological and clinical description. Brain. 2020;143:3089–3103. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kandemirli SG, Dogan L, Sarikaya ZT, Kara S, Akinci C, Kaya D, et al. Brain MRI findings in patients in the intensive care unit with COVID-19 infection. Radiology. 2020;297:E232–E235. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nawabi J, Morotti A, Wildgruber M, Boulouis G, Kraehling H, Schlunk F, et al. Clinical and imaging characteristics in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection and acute intracranial hemorrhage. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2543. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malhotra K, Gornbein J, Saver JL. Ischemic strokes due to large-vessel occlusions contribute disproportionately to stroke-related dependence and death: a review. Front Neurol. 2017;8:651. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dozois A, Hampton L, Kingston CW, Lambert G, Porcelli TJ, Sorenson D, et al. PLUMBER study (prevalence of large vessel occlusion strokes in Mecklenburg county emergency response) Stroke. 2017;48:3397–3399. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith WS, Lev MH, English JD, Camargo EC, Chou M, Johnston SC, et al. Significance of large vessel intracranial occlusion causing acute ischemic stroke and TIA. Stroke. 2009;40:3834–3840. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.561787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rennert RC, Wali AR, Steinberg JA, Santiago-Dieppa DR, Olson SE, Pannell JS, et al. Epidemiology, natural history, and clinical presentation of large vessel ischemic stroke. Neurosurgery. 2019;85:S4–S8. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyz042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beyrouti R, Adams ME, Benjamin L, Cohen H, Farmer SF, Goh YY, et al. Characteristics of ischaemic stroke associated with COVID-19. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91:889–891. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kremer S, Lersy F, de Sèze J, Ferré JC, Maamar A, Carsin-Nicol B, et al. Brain MRI findings in severe COVID-19: a retrospective observational study. Radiology. 2020;297:E242–E251. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bilinska K, Jakubowska P, Von Bartheld CS, Butowt R. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 entry proteins, ACE2 and TMPRSS2, in cells of the olfactory epithelium: identification of cell types and trends with age. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11:1555–1562. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Quality Assessment of the 17 Included Studies

Results of Subgroup Analysis of Critically Ill Patients

Results of Subgroup Analysis Regarding Whether Only MRI Was Used as an Imaging Modality or Not