Key Points

Question

Is influenza or other infection associated with Parkinson disease?

Findings

In this case-control study of all Danish citizens with Parkinson disease between 2000 and 2016, unlike most other infections, influenza was associated with Parkinson disease more than 10 years after infection.

Meaning

Influenza infection may increase the long-term risk of developing Parkinson disease.

This case-control study examines whether prior influenza and other infections are associated with Parkinson disease more than 10 years after infection using data from 1977 to 2016 from the Danish National Patient Registry.

Abstract

Importance

Influenza has been associated with the risk of developing Parkinson disease, but the association is controversial.

Objective

To examine whether prior influenza and other infections are associated with Parkinson disease more than 10 years after infection.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This case-control study used data from 1977 to 2016 from the Danish National Patient Registry. All individuals with Parkinson disease, excluding those with drug-induced parkinsonism, were included and matched to 5 population controls on sex, age, and date of Parkinson diagnosis. Data were analyzed from December 2019 to September 2021.

Exposures

Infections were ascertained between 1977 and 2016 and categorized by time from infection to Parkinson disease diagnosis. To increase specificity of influenza diagnoses, influenza exposure was restricted to months of peak influenza activity.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Parkinson disease diagnoses were identified between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2016. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were calculated by conditional logistic regression overall and stratified by time between infection and Parkinson disease (5 years or less, more than 5 to 10 years, more than 10 years).

Results

Of 61 626 included individuals, 23 826 (38.7%) were female, and 53 202 (86.3%) were older than 60 years. A total of 10 271 individuals with Parkinson disease and 51 355 controls were identified. Influenza diagnosed at any time during a calendar year was associated with Parkinson disease more than 10 years later (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.11-2.71). When influenza exposure was restricted to months of highest influenza activity, an elevated OR with a wider confidence interval was found (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.80-2.89). There was no evidence of an association with any type of infection more than 10 years prior to Parkinson disease (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.98-1.10). Several specific infections yielded increased odds of Parkinson disease within 5 years of infection, but results were null when exposure occurred more than 10 years prior.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this case-control study, influenza was associated with diagnoses of Parkinson disease more than 10 years after infection. These observational data suggest a link between influenza and Parkinson disease but do not demonstrate causality. While other infections were associated with Parkinson disease diagnoses soon after infection, null associations after more than 10 years suggest these shorter-term associations are not causal.

Introduction

Parkinson disease (PD)—characterized by cardinal features of bradykinesia, rest tremor, and rigidity1 — is the second most common neurodegenerative disease. Incidence and prevalence estimates vary depending on source, age, and case definitions.2,3,4 In Denmark, incidence has been estimated at 23 per 100 000 person-years,5 while a systematic literature review of European studies reported an incidence range from 5 to 346 per 100 000.6 In the US, a study that estimated incidence over 30 years reported a rate of 17 per 100 000 person-years for men and women combined.7 The pathological cascade preceding neurological symptoms is hypothesized to span 10 to 20 years or longer.8 While most PD cases are idiopathic, others are linked to known genetic variants3 or to suspected lifestyle factors and environmental exposures.2,3

A potential infectious etiology has been considered, with some reporting evidence of an association between certain infections and PD.9,10 Whether influenza is associated with PD or parkinsonism has been debated for decades.11,12 An epidemic of postencephalitic parkinsonism in 1916 to 1930, near and after the 1918 influenza pandemic, has been examined as potentially due to influenza.13,14,15 Research has been conducted broadly on the topic of influenza and PD and parkinsonism, with the suggestion that infections may play an etiological role for some cases.16,17

We conducted a large-scale case-control study drawing on population-based data prospectively collected over more than 35 years in Denmark. Our primary analysis focused on influenza infection, given the historic, long-held concerns about postencephalitic parkinsonism. Given the long preclinical period that precedes the appearance of cardinal motor signs of PD,8 we hypothesized that influenza infection would be associated with an increased risk of PD more than 10 years after infection. Because influenza infection was based on diagnosis codes and not on laboratory-confirmed infection, we increased the specificity of the influenza exposure definition by limiting exposure only to people with diagnosed influenza during times of peak influenza activity. Our secondary aim was to examine whether the hypothesized association between influenza and PD risk was specific for influenza or applied more broadly to a range of other infection types.

Methods

We conducted this population-based, registry-linked, case-control study in Denmark, where there is universal tax-supported health care, including free access to hospital care.18 All residents are assigned a unique personal identification number, registered in the Danish Civil Registration System, which permits unambiguous individual-level linkage among all Danish registries.19 This study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. Informed consent was not required for this study.

Study Population

We included all residents of Denmark from the national health care databases and identified all patients who received an incident PD diagnosis at a somatic treatment facility from January 1, 2000, through December 31, 2016.18 These patients were identified from the Danish National Patient Registry, which has recorded all diagnoses and procedures associated with inpatient hospitalizations in Denmark since 1977 and all hospital-based outpatient clinic visits since 1995.20 Individuals with PD were included if they had a diagnosis of interest in 2000 through 2016, with no prior PD diagnosis back to 1977. Diagnoses were coded according to International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision (ICD-8) codes from 1977 to 1993 (PD, code 342) and ICD-10 codes since 1994 (PD, code G20). We excluded all individuals with PD younger than 35 years because early-onset PD is rare and pathogenetic mechanisms might differ. We also excluded individuals who had a diagnosis code for drug-induced secondary parkinsonism in their registry history (ICD-10 codes G21.1, G21.11, G21.19) as well as those with a history of use of a medication associated with parkinsonism as captured in the Danish National Health Service Prescription Database back to 200421 (eAppendix 1 in the Supplement). We used the Danish Civil Registration System to assemble a control group of individuals without a PD diagnosis or secondary parkinsonism; they were matched 5 to 1 with individuals with PD on age and sex. Controls were alive on the PD diagnosis date of their matched counterparts, and each control was assigned an index date that was the date of the PD diagnosis. Age was identified on index date. Matching was done without replacement.

Influenza and Other Infections

We defined infection as any incident inpatient admission or outpatient hospital clinic contact associated with a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of infection. For the primary analysis for influenza, we applied 2 different exposure definitions, each examined separately (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement). First, in our primary analysis, individuals were considered exposed if they had a diagnosis code of interest at any time during a given calendar year. Second, in a sensitivity analysis, we defined influenza exposure based on documentation of an influenza diagnosis code only when influenza was clearly circulating (ie, during peaks in influenza activity). This approach would likely increase the positive predictive value of an influenza diagnosis at the expense of missing influenza cases during interpeak periods.

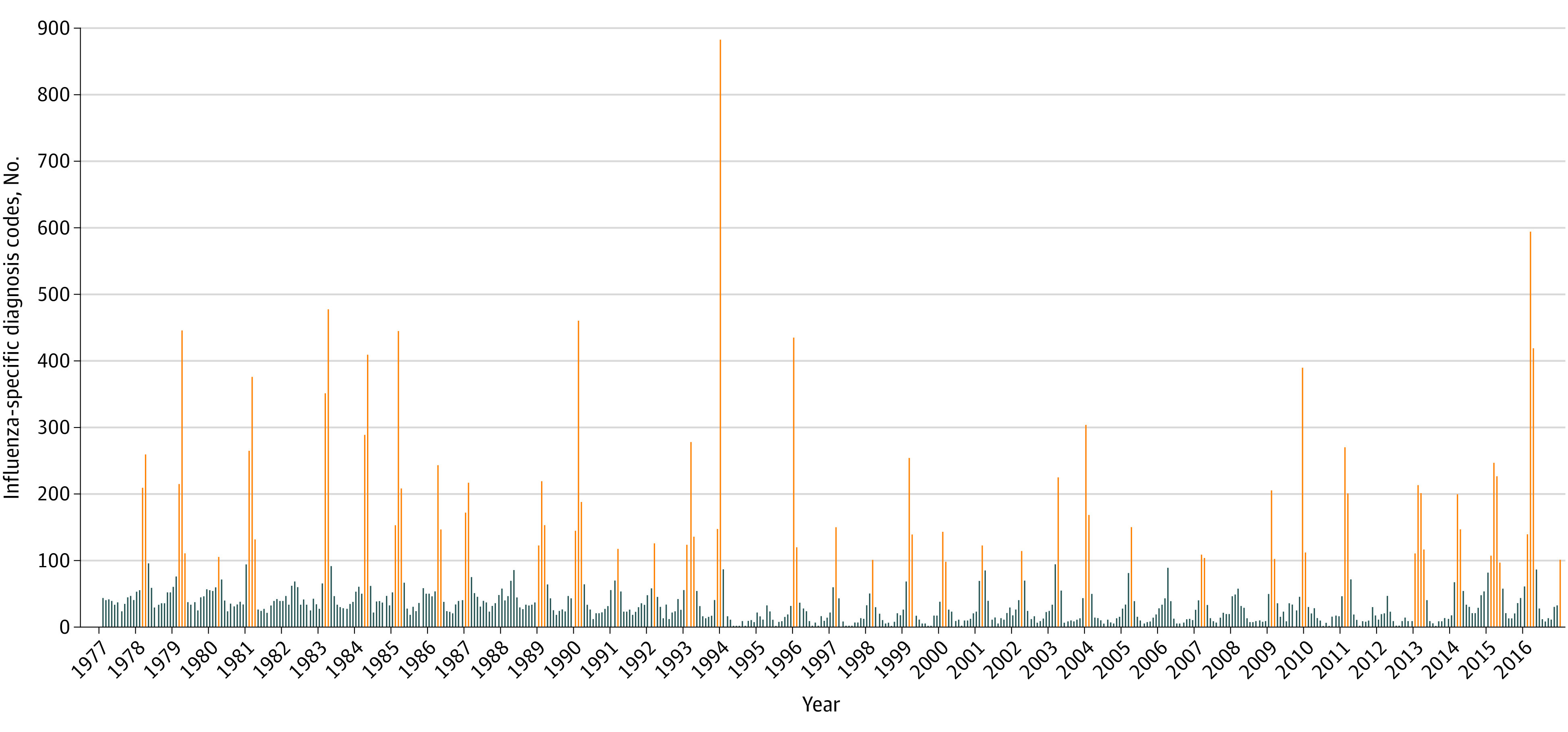

We calculated and plotted the number of influenza diagnoses by month-year on graphs using data from inpatient and outpatient hospital clinics in the Danish National Patient Registry from 1977 through 2016. We calculated the median number of diagnoses per month (32 diagnoses per month) and identified peaks as those months with more than 3-fold the median (more than 96 diagnoses per month). See eAppendix 3 in the Supplement for the month-year ranges that were used and Figure 1 for the time series data for influenza diagnoses. If an individual had multiple valid exposures of influenza, only the first was counted.

Figure 1. Counts of Influenza-Related Diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry by Year, 1977 to 2016.

Counts of influenza-specific diagnosis codes from 1977 to 2016. Each bar represents a month. Orange indicates months of increased influenza activity, and blue indicates months when influenza activity was not increased. Diagnosis codes can be found in eAppendix 2 in the Supplement.

For the secondary analysis, we explored a range of specific infections and more general infection types (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement). Each infection type was assessed independently, using the incident occurrence of each infection type. As a sensitivity analysis, we also examined the association between infection and PD, limited to individuals with PD and controls with only 1 diagnosed antecedent infection. We did not consider peak seasonal trends for these secondary analyses.

Statistical Analysis

We characterized individuals with PD and controls by age, sex, and select comorbid conditions. We used conditional logistic regression to compare individuals with PD with controls with respect to infections, calculating crude odds ratios (ORs) with associated 95% CIs. Given the anticipated small number of exposed cases, we approached confounder adjustment parsimoniously. We adjusted for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, Crohn disease, and ulcerative colitis given their associations with PD, infection, or smoking.2,22 We also adjusted for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema, and lung cancer, proxies for smoking, which is associated with decreased risk of PD.23,24 Analyses were stratified by time since infection (5 years or less, more than 5 to 10 years, and more than 10 years; influenza analyses were further stratified by 10 to 15 years and more than 15 years), with the prespecified exposure of interest occurring more than 10 years before a first-time diagnosis of PD.

The statistical significance threshold was set at P < .05, and all P values were 1-tailed. We used Wald χ2 test statistic for the hypothesis test that the regression coefficient is zero. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

There were 12 324 individuals with an incident inpatient or outpatient hospital-based diagnosis of PD from January 2000 and through December 2016; we excluded 2053 with evidence of drug-induced secondary parkinsonism. There were 10 271 individuals with PD in the study population, of whom 3971 (38.7%) were female and 8867 (86.3%) were older than 60 years at diagnosis; the mean (SD) age was 71.4 (10.6) years. These were matched to 51 355 controls. Table 1 shows the characteristics at the time of diagnosis or index date. As expected,25 slightly fewer individuals with PD had COPD or emphysema (665 [6.5%]) compared with controls (3965 [7.7%]), while the distribution of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, and lung cancer were similar between the 2 groups.

Table 1. Characteristics of Individuals With Parkinson Disease (PD) and Matched Controls in Denmark, January 2000 to December 2016.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals with PD (n = 10 271) | Controls (n = 51 355) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 6300 (61.3) | 31 500 (61.3) |

| Female | 3971 (38.7) | 19 855 (38.7) |

| Age, y | ||

| ≤40 | 49 (0.5) | 245 (0.5) |

| 41-50 | 323 (3.1) | 1615 (3.1) |

| 51-60 | 1032 (10.0) | 5160 (10.0) |

| 61-70 | 2561 (24.9) | 12 805 (24.9) |

| 71-80 | 3872 (37.7) | 19 360 (37.7) |

| ≥81 | 2434 (23.7) | 12 170 (23.7) |

| PD diagnosis or index date | ||

| 2000-2007 | 4647 (45.2) | 23 235 (45.2) |

| 2008-2016 | 5624 (54.8) | 28 120 (54.8) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 2132 (20.8) | 10 680 (20.8) |

| Diabetes | 664 (6.5) | 3381 (6.6) |

| Crohn disease | 27 (0.3) | 133 (0.3) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 108 (1.1) | 379 (0.7) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or emphysema | 665 (6.5) | 3965 (7.7) |

| Lung cancer | 31 (0.3) | 280 (0.5) |

Influenza Analyses

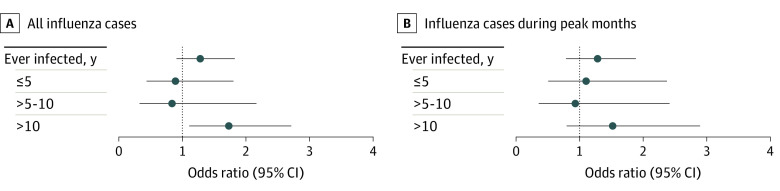

Table 2 and Figure 2 show the results for the 2 influenza exposure definitions. When we identified influenza-specific codes at any calendar time more than 10 years prior to PD, we observed an increased OR (1.73; 95% CI, 1.11-2.71) in the fully adjusted analysis. We further stratified the more than 10-year time interval into more than 10 to 15 years and more than 15 years from infection to PD diagnosis and found a higher OR with the more time from infection (more than 10 to 15 years: OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.54-3.27; more than 15 years: OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.14-3.19). In our sensitivity analysis for influenza, when we restricted exposure to the months when influenza activity was highest, the OR was somewhat lower and the confidence interval was wider because of fewer exposed individuals (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.80-2.89).

Table 2. Association of Influenza With Parkinson Disease (PD) by Time Since Infection Among Individuals With PD Identified in Denmark, January 2000 to December 2016.

| Measure | No. | OR (95% CI) | P value for adjusted model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with PD | Controls | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | ||

| Influenza-specific codes during any calendar time | |||||

| Unexposed | 10 231 | 51 196 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Ever infected prior to PD | 40 | 159 | 1.26 (0.89-1.78) | 1.28 (0.91-1.82) | .16 |

| ≤5 y | <10 | 52 | 0.87 (0.43-1.76) | 0.89 (0.44-1.80) | .74 |

| >5-10 y | <10 | 31 | 0.81 (0.31-2.07) | 0.84 (0.33-2.16) | .72 |

| >10 y | 26 | 76 | 1.71 (1.10-2.67) | 1.73 (1.11-2.71) | .02 |

| >10-15 yb | 6 | 23 | 1.30 (0.53-3.20) | 1.33 (0.54-3.27) | .53 |

| >15 yb | 20 | 53 | 1.89 (1.13-3.16) | 1.91 (1.14-3.19) | .01 |

| Influenza-specific codes during peak influenza activity | |||||

| Unexposed | 10 246 | 51 249 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Ever infected prior to PD | 25 | 106 | 1.18 (0.76-1.82) | 1.22 (0.79-1.88) | .38 |

| ≤5 y | 8 | 37 | 1.08 (0.50-2.32) | 1.10 (0.51-2.37) | .81 |

| >5-10 y | 5 | 28 | 0.89 (0.34-2.31) | 0.93 (0.36-2.41) | .88 |

| >10 yc | 12 | 41 | 1.46 (0.77-2.78) | 1.52 (0.80-2.89) | .21 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

Adjusted models are adjusted for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, lung cancer, Crohn disease, and ulcerative colitis.

Individuals in these categories are included in the more than 10 years category.

Stratified results for more than 10 to 15 years and more than 15 years are not shown because numbers and results are suppressed for cells where small counts would enable calculation of numbers less than 5.

Figure 2. Odds Ratios of the Association of Influenza With Parkinson Disease by Time Since Infection Among Individuals With Parkinson Disease Identified in Denmark, January 2000 to December 2016.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs for the primary analysis and sensitivity analyses for influenza. A, For the primary analysis, we identified prior influenza at any time during a calendar year. B, For the sensitivity analysis, we identified prior influenza only during peaks of influenza activity.

Secondary Analyses

Overall, 3229 individuals with PD (31.4%) and 15 461 controls (30.1%) had a prior diagnosis of an infection, corresponding to an adjusted OR of 1.09 (95% CI, 1.04-1.14) (Table 3). For any type of infection, the overall result suggested a small association. When we looked by time since first infection, we found a larger OR within 5 years (OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.18-1.36) and an attenuated result when we looked among those with at least 10 years since infection (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.98-1.10). For the sensitivity analysis where we examined the association between infection and PD among those with only 1 infection diagnosis prior to PD, we found nearly identical results (Table 3).

Table 3. Association of Infections With Parkinson Disease (PD) by Time Since Infection Among Patients With Parkinson Identified in Denmark, January 2000 to December 2016.

| Measure | No. | OR (95% CI)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with PD | Controls | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Any infection (includes people with >1 diagnosed infection type) | ||||

| Unexposed (no history of an infection) | 7042 | 35 894 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 3229 | 15 461 | 1.07 (1.02-1.12) | 1.09 (1.04-1.14) |

| ≤5 y | 1051 | 4362 | 1.23 (1.15-1.32) | 1.27 (1.18-1.36) |

| >5-10 y | 560 | 2990 | 0.96 (0.87-1.05) | 0.98 (0.89-1.08) |

| >10 y | 1618 | 8109 | 1.02 (0.96-1.08) | 1.04 (0.98-1.10) |

| Only 1 diagnosed infection (excludes people with multiple infection types) | ||||

| Unexposed (no history of an infection) | 7042 | 35 894 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 1710 | 8121 | 1.08 (1.02-1.14) | 1.09 (1.03-1.16) |

| ≤5 y | 616 | 2494 | 1.27 (1.16-1.40) | 1.30 (1.18-1.43) |

| >5-10 y | 284 | 1528 | 0.94 (0.82-1.07) | 0.96 (0.84-1.09) |

| >10 y | 810 | 4099 | 1.01 (0.93-1.10) | 1.02 (0.94-1.11) |

| Pneumoniab | ||||

| Unexposed | 9466 | 47 519 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 805 | 3836 | 1.05 (0.97-1.14) | 1.12 (1.03-1.21) |

| ≤5 y | 450 | 1919 | 1.18 (1.06-1.31) | 1.25 (1.12-1.39) |

| >5-10 y | 154 | 881 | 0.88 (0.74-1.05) | 0.94 (0.79-1.12) |

| >10 y | 201 | 1036 | 0.97 (0.84-1.14) | 1.02 (0.88-1.19) |

| Gastrointestinal infection | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 024 | 50 309 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 247 | 1046 | 1.19 (1.03-1.37) | 1.19 (1.04-1.38) |

| ≤5 y | 106 | 388 | 1.37 (1.11-1.70) | 1.38 (1.11-1.72) |

| >5-10 y | 51 | 228 | 1.12 (0.83-1.53) | 1.13 (0.83-1.54) |

| >10 y | 90 | 430 | 1.05 (0.84-1.32) | 1.06 (0.84-1.33) |

| Miscellaneous bacterial infections | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 180 | 50 949 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 91 | 406 | 1.12 (0.89-1.41) | 1.13 (0.90-1.42) |

| ≤5 y | 54 | 193 | 1.40 (1.03-1.90) | 1.42 (1.05-1.92) |

| >5-10 y | 20 | 94 | 1.06 (0.66-1.72) | 1.07 (0.66-1.73) |

| >10 y | 17 | 119 | 0.72 (0.43-1.19) | 0.72 (0.43-1.20) |

| Septicemia | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 069 | 50 651 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 202 | 704 | 1.45 (1.24-1.70) | 1.47 (1.26-1.73) |

| ≤5 y | 148 | 447 | 1.68 (1.39-2.02) | 1.71 (1.42-2.07) |

| >5-10 y | 38 | 155 | 1.23 (0.87-1.76) | 1.25 (0.88-1.79) |

| >10 y | 16 | 102 | 0.79 (0.47-1.34) | 0.80 (0.47-1.36) |

| Herpes simplex or zoster | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 226 | 51 095 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 45 | 260 | 0.86 (0.63-1.19) | 0.88 (0.64-1.20) |

| ≤5 y | 19 | 88 | 1.08 (0.66-1.77) | 1.08 (0.66-1.78) |

| >5-10 y | 6 | 53 | 0.57 (0.24-1.32) | 0.58 (0.25-1.35) |

| >10 y | 20 | 119 | 0.84 (0.52-1.35) | 0.85 (0.53-1.37) |

| Viral hepatitisc,d | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 244 | 51 219 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 27 | 136 | 0.99 (0.66-1.50) | 0.99 (0.66-1.50) |

| ≤5 y | 6 | 28 | 1.07 (0.44-2.58) | 1.07 (0.44-2.58) |

| >5-10 y | 9 | 27 | 1.67 (0.78-3.54) | 1.66 (0.78-3.54) |

| >10 y | 12 | 81 | 0.74 (0.40-1.36) | 0.74 (0.41-1.36) |

| Miscellaneous viral infections | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 200 | 51 018 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 71 | 337 | 1.05 (0.82-1.36) | 1.07 (0.83-1.38) |

| ≤5 y | 18 | 86 | 1.05 (0.63-1.74) | 1.08 (0.65-1.80) |

| >5-10 y | 18 | 66 | 1.36 (0.81-2.30) | 1.38 (0.82-2.32) |

| >10 y | 35 | 185 | 0.95 (0.66-1.36) | 0.96 (0.67-1.37) |

| Candidiasis | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 201 | 51 091 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 70 | 264 | 1.33 (1.02-1.73) | 1.36 (1.05-1.78) |

| ≤5 y | 34 | 107 | 1.59 (1.08-2.34) | 1.63 (1.11-2.39) |

| >5-10 y | 13 | 63 | 1.03 (0.57-1.88) | 1.05 (0.58-1.91) |

| >10 y | 23 | 94 | 1.23 (0.78-1.93) | 1.27 (0.81-2.01) |

| Other infections or sequelae | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 004 | 50 219 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 267 | 1136 | 1.18 (1.03-1.35) | 1.19 (1.04-1.36) |

| ≤5 y | 92 | 338 | 1.37 (1.08-1.72) | 1.38 (1.09-1.74) |

| >5-10 y | 62 | 240 | 1.30 (0.98-1.72) | 1.31 (0.99-1.73) |

| >10 y | 113 | 558 | 1.02 (0.83-1.25) | 1.02 (0.83-1.25) |

| Central nervous system infections (except meningococcal disease) | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 229 | 51 110 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 42 | 245 | 0.86 (0.62-1.19) | 0.87 (0.62-1.20) |

| ≤5 y | 12 | 57 | 1.05 (0.56-1.96) | 1.04 (0.56-1.94) |

| >5-10 y | 12 | 55 | 1.09 (0.58-2.04) | 1.11 (0.60-2.08) |

| >10 y | 18 | 133 | 0.68 (0.41-1.11) | 0.69 (0.42-1.12) |

| Heart infections | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 231 | 51 140 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 40 | 215 | 0.93 (0.66-1.30) | 0.94 (0.67-1.33) |

| ≤5 y | 11 | 55 | 1.00 (0.52-1.91) | 1.01 (0.53-1.93) |

| >5-10 y | 6 | 40 | 0.75 (0.32-1.77) | 0.76 (0.32-1.80) |

| >10 y | 23 | 120 | 0.96 (0.61-1.50) | 0.97 (0.62-1.52) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 123 | 50 506 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 148 | 849 | 0.87 (0.73-1.04) | 0.88 (0.74-1.05) |

| ≤5 y | 26 | 155 | 0.84 (0.55-1.27) | 0.84 (0.56-1.28) |

| >5-10 y | 19 | 136 | 0.70 (0.43-1.13) | 0.70 (0.43-1.13) |

| >10 y | 103 | 558 | 0.92 (0.75-1.14) | 0.93 (0.75-1.15) |

| Lower respiratory tract infection other than pneumonia | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 134 | 50 507 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 137 | 848 | 0.80 (0.67-0.97) | 0.89 (0.74-1.08) |

| ≤5 y | 74 | 435 | 0.85 (0.66-1.09) | 0.95 (0.73-1.22) |

| >5-10 y | 24 | 186 | 0.64 (0.42-0.98) | 0.72 (0.47-1.10) |

| >10 y | 39 | 227 | 0.86 (0.61-1.20) | 0.93 (0.66-1.31) |

| Intra-abdominal infections | ||||

| Unexposed | 9648 | 48 258 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 623 | 3097 | 1.01 (0.92-1.10) | 1.01 (0.92-1.10) |

| ≤5 y | 115 | 648 | 0.89 (0.73-1.08) | 0.90 (0.73-1.10) |

| >5-10 y | 105 | 540 | 0.97 (0.79-1.20) | 0.98 (0.79-1.20) |

| >10 y | 403 | 1909 | 1.06 (0.95-1.18) | 1.05 (0.94-1.17) |

| Skin and subcutaneous infections | ||||

| Unexposed | 9816 | 48 837 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 455 | 2518 | 0.90 (0.81-1.00) | 0.91 (0.82-1.00) |

| ≤5 y | 122 | 668 | 0.91 (0.75-1.10) | 0.91 (0.75-1.11) |

| >5-10 y | 74 | 488 | 0.75 (0.59-0.96) | 0.76 (0.60-0.98) |

| >10 y | 259 | 1362 | 0.95 (0.83-1.08) | 0.95 (0.83-1.09) |

| Septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, or myositis | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 232 | 51 110 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 39 | 245 | 0.79 (0.57-1.12) | 0.80 (0.57-1.12) |

| ≤5 y | 11 | 71 | 0.77 (0.41-1.46) | 0.78 (0.41-1.47) |

| >5-10 y | 6 | 64 | 0.47 (0.20-1.08) | 0.47 (0.20-1.08) |

| >10 y | 22 | 110 | 1.00 (0.63-1.58) | 1.00 (0.63-1.58) |

| Urinary tract infections | ||||

| Unexposed | 9472 | 48 394 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 799 | 2961 | 1.40 (1.28-1.52) | 1.42 (1.30-1.54) |

| ≤5 y | 474 | 1492 | 1.65 (1.48-1.83) | 1.68 (1.50-1.87) |

| >5-10 y | 145 | 678 | 1.11 (0.93-1.33) | 1.13 (0.94-1.35) |

| >10 y | 180 | 791 | 1.17 (1.00-1.38) | 1.19 (1.01-1.40) |

| Male genital infections | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 140 | 50 786 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 131 | 569 | 1.15 (0.95-1.40) | 1.16 (0.96-1.41) |

| ≤5 y | 45 | 150 | 1.50 (1.08-2.09) | 1.52 (1.09-2.13) |

| >5-10 y | 22 | 117 | 0.95 (0.60-1.49) | 0.95 (0.60-1.50) |

| >10 y | 64 | 302 | 1.06 (0.81-1.39) | 1.06 (0.81-1.40) |

| Female pelvic infections | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 125 | 50 619 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 146 | 736 | 0.99 (0.83-1.19) | 1.00 (0.84-1.20) |

| ≤5 y | 16 | 56 | 1.43 (0.82-2.49) | 1.43 (0.82-2.49) |

| >5-10 y | 14 | 66 | 1.06 (0.59-1.88) | 1.07 (0.60-1.91) |

| >10 y | 116 | 614 | 0.94 (0.77-1.16) | 0.95 (0.78-1.17) |

| Infectious complications of procedures or catheters | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 135 | 50 571 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 136 | 784 | 0.87 (0.72-1.04) | 0.87 (0.72-1.04) |

| ≤5 y | 37 | 288 | 0.64 (0.45-0.90) | 0.64 (0.45-0.90) |

| >5-10 y | 33 | 170 | 0.97 (0.67-1.41) | 0.98 (0.67-1.42) |

| >10 y | 66 | 326 | 1.01 (0.77-1.32) | 1.01 (0.77-1.32) |

| Tuberculosisd | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 252 | 51 257 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 19 | 98 | 0.97 (0.59-1.59) | 0.99 (0.61-1.63) |

| >10 y | NR | NR | 1.17 (0.67-2.06) | 1.21 (0.69-2.12) |

| Obstetrical infectionsd | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 240 | 51 201 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 31 | 154 | 1.01 (0.68-1.49) | 1.01 (0.68-1.50) |

| >10 y | NR | NR | 1.03 (0.69-1.54) | 1.03 (0.69-1.55) |

| Parasitic infectionsd | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 232 | 51 153 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 39 | 202 | 0.97 (0.68-1.36) | 0.97 (0.69-1.37) |

| >10 y | 30 | 167 | 0.90 (0.61-1.33) | 0.91 (0.61-1.34) |

| Sexually transmitted diseasesd | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 240 | 51 168 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 31 | 187 | 0.83 (0.56-1.21) | 0.83 (0.57-1.22) |

| >10 y | NR | NR | 0.88 (0.58-1.36) | 0.90 (0.58-1.38) |

| Meningococcal diseased | ||||

| Unexposed | 10 264 | 51 327 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ever infected | 7 | 28 | 1.25 (0.54-2.89) | 1.28 (0.56-2.96) |

Abbreviations: NR, not reported; OR, odds ratio.

Infections prior to PD diagnosis/index were assessed. The model adjusts for cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, and diabetes.

Pneumonia exposure does not include influenza-specific pneumonia codes.

Viral hepatitis includes unspecified and specific virus types. Given the small numbers and lack of type-specific International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision codes, we examined an overall viral hepatitis category. The number of exposed individuals with PD and controls with hepatitis B virus–specific or hepatitis C virus–specific ICD-10 codes at the time of first viral hepatitis were 136 and 27, respectively (codes: B16.0, B16.1, B16.2, B16.9, B17.0, B17.10, B17.11, B18.0, B18.1, B18.2, B19.10, B19.11, B19.20, B19.21).

Infections without results for each time period are those with numbers too small to calculate estimates or whose results cannot be reported because of small cells. Numbers are suppressed for cells where small counts would enable calculation of numbers.

Several specific infections showed no evidence of an association when the infection was at least 10 years prior (null or near-null results) but an increased OR when time since infection was less than 5 years between infection and PD diagnosis (Table 3): pneumonia, gastrointestinal infection, miscellaneous bacterial infections, septicemia, and male genital infections. Only urinary tract infections had a small increased OR for PD more than 10 years after infection (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.01-1.40). For several infection types, confidence intervals were wide when restricted to at least 10 years between infection and PD diagnosis or case numbers were too small to report results.

Discussion

In this population-based study of infections and subsequent PD, our results showed an association between influenza and PD. The odds of PD were elevated by more than 70% for PD occurring more than 10 years after influenza infection; it was approximately 90% for PD occurring more than 15 years after influenza. In the more than 10 to 15–year stratum, we observed a reduced point estimate and nonsignificant confidence interval that could be because of exposure misclassification or because the risk of PD is primarily associated with infections more than 15 years prior. The point estimate was also elevated when PD was greater than 10 years after influenza in our sensitivity analysis when we used a more restricted definition of influenza, although the confidence interval was wide owing to a decrease in the number of exposed individuals. Here, we only counted those who met the exposure definition during a time of peak influenza activity. For the other infection types, while several infections appeared to be associated with PD within 5 years of infection (eg, gastrointestinal infection, septicemia, male genital infections), most associations appeared to be null after more than 10 years from infection. Aside from influenza, urinary tract infections were the only infection type with an increased odds of PD more than 10 years after infection.

Because of a long preclinical phase spanning a decade or more before the appearance of cardinal motor signs of PD,8 we hypothesized that influenza infection would be associated with an increased risk of PD more than 10 years after infection. Such an association would support the contention of a possible causal link, but observational data reported here cannot prove causality. On the other hand, shorter-term associations between infection—or other potential risk factors—and PD would raise concern about the direction of causation.

Some patients with prodromal PD—for example, those with rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder—already exhibit a burden of nonmotor symptoms similar to that of patients with diagnosed PD, including marked dysautonomia.26 Thus, it seems probable that some patients with prodromal PD may be at increased risk of infection27,28 during the several years before the emergence of cardinal motor features. Apart from influenza, only urinary tract infection had an increased odds for PD more than 10 years later (increase of 19% [OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.01-1.40] for urinary tract infection compared with increase of 73% [OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.11-2.71] for influenza). It is possible that urinary tract infections might be a very early manifestation of PD rather than a causative factor. Urinary tract infections and neurogenic bladder are a particularly significant source of morbidity among patients with PD,29,30,31 and autonomic dysfunction, predisposing to urinary tract infection, often appears during the prodromal phase.26,32

Nevertheless, we cannot dismiss the possibility that urinary tract infection is also a risk factor for PD. Moreover, it is possible that the prodromal phase in some patients with PD may be shorter than 10 years, so we cannot completely discount a causal role for other infections within 5 years of diagnosed PD. Speculatively, some infections might accelerate or unmask prodromal PD during the early follow-up period.

Concerning our influenza results, increased susceptibility to respiratory infections among those with PD is believed to be mainly related to motor disability, and subclinical motor manifestations do not develop more than 10 years before a PD diagnosis.8,33 Thus, a potentially causal relationship seems more probable here. Moreover, neither pneumonia nor upper or lower respiratory tract infection more than 10 years before PD diagnosis was associated with PD risk.

Other studies have examined whether infections are associated with PD, with one hypothesized mechanism of action being central nervous system inflammation as a consequence of systemic infection.17,34 Two studies have shown that appendectomy is associated with an increased risk of subsequent PD, perhaps owing to the preceding inflammatory state of appendicitis,35,36 but others have not found an association.37 Research results are sparse and mixed as to whether specific infections increase risk of PD, with Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis C virus infections emerging as particularly relevant.38,39,40 Case counts were too low for H pylori in our data to examine this association independently, and the confidence intervals were too wide to interpret any association between viral hepatitis and PD.

Since the 1918 influenza pandemic, there has been sustained interest in the association between influenza, encephalitis lethargica, and postencephalitic parkinsonism.11,41 Recently, a group using the United Kingdom General Practice Research Database reported an association between recent influenza infection and PD symptoms but not with developing idiopathic PD.42 A small case-control study in Canada found an association between severe influenza more than 10 years prior and PD, although the medical history was obtained via self-report.43 Similarly, a small case-control study in Serbia found large ORs for several hospital-diagnosed infections, identified via self-report, including influenza.44 Several older studies examined in utero influenza exposure, with conflicting results.45,46 Findings from a 2016 Swedish study47 suggest early-life exposures, including influenza activity in the year of birth, are not associated with PD, and a 2007 Canadian study48 also did not find evidence of birth during influenza pandemic years to be associated with PD. One hypothesis is that the role of influenza on PD risk, if any, may be specific to the circulating virus strain.17 As others have noted as well, the potential for SARS-CoV-2 to have neurologic sequelae is unknown but is an obvious concern.49

Strengths and Limitations

A main strength of our study is that it is a population-based study in a single country, where it is likely that coding practices are applied consistently over decades. Given Denmark’s national health system, variations in health care access and practice are less of a concern than in most countries. We carefully considered the timing between infection and PD, and we looked at multiple time frames between infection and PD diagnosis.

Our study has limitations. Since influenza infections, like other infections we studied, are not laboratory confirmed in the Danish National Patient Registry, exposure misclassification is a concern. Previous data have documented 66% of patients with hospital-diagnosed influenza in the Danish National Patient Registry had a positive influenza test in the Danish Microbiology Database, which contains nationwide information on polymerase chain reaction and antigen tests for influenza virus.50 We aimed to increase the likelihood of the influenza definition to represent true infection by identifying diagnoses only during periods when influenza appeared to be circulating based on seasonal trends. With this restrictive exposure definition, the point estimate for influenza more than 10 years prior to PD was less precise but still elevated.

Despite conducting our study with national registry data over a long time period, some specific infections had small numbers in the analyses, limiting our ability to interpret results for some infections, such as H pylori or hepatitis C. We only studied more severe, medically attended infections diagnosed in a hospital or hospital-associated outpatient clinic, an aspect of the study design that provides more specificity in exposure capture but less sensitivity. Diagnoses in this setting are likely to occur in patients who are more severely symptomatic, and our findings may generalize to more severe symptomatic infection rather than infections with milder symptoms. It is likely for this reason that we identified small numbers of cases or controls with viral hepatitis, for example.

Additionally, residual confounding from smoking is a potential problem. Smoking is associated not only with increased risk of infection and with increased influenza severity but also with decreased risk of PD. We did not have access to data on smoking history, but we adjusted for several proxies (COPD, emphysema, and lung cancer). Any residual confounding from increased smoking among influenza-exposed people would probably have decreased the association with PD and thus would not change our conclusions of a positive association between influenza and PD. In addition, family history of PD is unmeasurable in these data, and it is possible that risk vulnerability might differ on different genetic backgrounds.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study provides evidence of an association between influenza and PD more than 10 years later. The ability to examine carefully the timing of infection and incident PD strengthens inferences regarding a possible causal association between influenza and PD. We did not find similar associations for pneumonia, other respiratory tract infections, or most other infections, and our findings for influenza are strengthened by the specificity of this association.

eAppendix 1. Medications associated with parkinsonism for exclusion criteria.

eAppendix 2. Diagnosis codes used to identify exposures of interest.

eAppendix 3. Month-year ranges used for influenza exposure definitions derived from data from the Danish National Patient Registry.

References

- 1.Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M, et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30(12):1591-1601. doi: 10.1002/mds.26424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wirdefeldt K, Adami HO, Cole P, Trichopoulos D, Mandel J. Epidemiology and etiology of Parkinson’s disease: a review of the evidence. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26(suppl 1):S1-S58. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9581-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tysnes OB, Storstein A. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2017;124(8):901-905. doi: 10.1007/s00702-017-1686-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pringsheim T, Jette N, Frolkis A, Steeves TD. The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2014;29(13):1583-1590. doi: 10.1002/mds.25945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vestergaard SV, Rasmussen TB, Stallknecht S, et al. Occurrence, mortality and cost of brain disorders in Denmark: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e037564. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Campenhausen S, Bornschein B, Wick R, et al. Prevalence and incidence of Parkinson’s disease in Europe. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15(4):473-490. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savica R, Grossardt BR, Bower JH, Ahlskog JE, Rocca WA. Time trends in the incidence of Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(8):981-989. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savica R, Rocca WA, Ahlskog JE. When does Parkinson disease start? Arch Neurol. 2010;67(7):798-801. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Limphaibool N, Iwanowski P, Holstad MJV, Kobylarek D, Kozubski W. Infectious etiologies of parkinsonism: pathomechanisms and clinical implications. Front Neurol. 2019;10:652. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsen LK, Dowd E, McKernan DP. A role for viral infections in Parkinson’s etiology? Neuronal Signal. 2018;2(2):NS20170166. doi: 10.1042/NS20170166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore G. Influenza and Parkinson’s disease. Public Health Rep. 1977;92(1):79-80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henry J, Smeyne RJ, Jang H, Miller B, Okun MS. Parkinsonism and neurological manifestations of influenza throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16(9):566-571. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poskanzer DC, Schwab RS. Cohort analysis of Parkinson’s syndrome: evidence for a single etiology related to subclinical infection about 1920. J Chronic Dis. 1963;16(9):961-973. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(63)90098-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dourmashkin RR. What caused the 1918-30 epidemic of encephalitis lethargica? J R Soc Med. 1997;90(9):515-520. doi: 10.1177/014107689709000916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bond M, Bechter K, Müller N, Tebartz van Elst L, Meier U-C. A role for pathogen risk factors and autoimmunity in encephalitis lethargica? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;109:110276. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estupinan D, Nathoo S, Okun MS. The demise of Poskanzer and Schwab’s influenza theory on the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2013;2013:167843. doi: 10.1155/2013/167843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smeyne RJ, Noyce AJ, Byrne M, Savica R, Marras C. Infection and risk of Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2021;11(1):31-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Adelborg K, et al. The Danish health care system and epidemiological research: from health care contacts to database records. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:563-591. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S179083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(8):541-549. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449-490. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johannesdottir SA, Horváth-Puhó E, Ehrenstein V, Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. Existing data sources for clinical epidemiology: the Danish National Database of Reimbursed Prescriptions. Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:303-313. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S37587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee H-S, Lobbestael E, Vermeire S, Sabino J, Cleynen I. Inflammatory bowel disease and Parkinson’s disease: common pathophysiological links. Gut. 2021;70(2):408-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobs BM, Belete D, Bestwick J, et al. Parkinson’s disease determinants, prediction and gene-environment interactions in the UK Biobank. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(10):1046-1054. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, Li W, Liu G, Shen X, Tang Y. Association between cigarette smoking and Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;61(3):510-516. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ritz B, Ascherio A, Checkoway H, et al. Pooled analysis of tobacco use and risk of Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(7):990-997. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.7.990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferini-Strambi L, Oertel W, Dauvilliers Y, et al. Autonomic symptoms in idiopathic REM behavior disorder: a multicentre case-control study. J Neurol. 2014;261(6):1112-1118. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7317-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su CM, Kung CT, Chen FC, et al. Manifestations and outcomes of patients with Parkinson’s disease and serious infection in the emergency department. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:6014896. doi: 10.1155/2018/6014896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerlach OH, Winogrodzka A, Weber WE. Clinical problems in the hospitalized Parkinson’s disease patient: systematic review. Mov Disord. 2011;26(2):197-208. doi: 10.1002/mds.23449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ginsberg D. The epidemiology and pathophysiology of neurogenic bladder. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(10)(suppl):s191-s196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rogers MA, Fries BE, Kaufman SR, Mody L, McMahon LF Jr, Saint S. Mobility and other predictors of hospitalization for urinary tract infection: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-8-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahajan A, Balakrishnan P, Patel A, et al. Epidemiology of inpatient stay in Parkinson’s disease in the United States: insights from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;31:162-165. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez-Ramirez D, Velazquez-Avila ES, Almaraz-Espinoza A, et al. Lower urinary tract and gastrointestinal dysfunction are common in early Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2020;2020:1694547. doi: 10.1155/2020/1694547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fereshtehnejad S-M, Yao C, Pelletier A, Montplaisir JY, Gagnon J-F, Postuma RB. Evolution of prodromal Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies: a prospective study. Brain. 2019;142(7):2051-2067. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu B, Gao HM, Hong JS. Parkinson’s disease and exposure to infectious agents and pesticides and the occurrence of brain injuries: role of neuroinflammation. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111(8):1065-1073. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marras C, Lang AE, Austin PC, Lau C, Urbach DR. Appendectomy in mid and later life and risk of Parkinson’s disease: a population-based study. Mov Disord. 2016;31(8):1243-1247. doi: 10.1002/mds.26670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Svensson E, Horváth-Puhó E, Stokholm MG, Sørensen HT, Henderson VW, Borghammer P. Appendectomy and risk of Parkinson’s disease: a nationwide cohort study with more than 10 years of follow-up. Mov Disord. 2016;31(12):1918-1922. doi: 10.1002/mds.26761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishizuka M, Shibuya N, Takagi K, et al. Appendectomy does not increase the risk of future emergence of Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Am Surg. Published online January 30, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang H, Liu X, Tan C, et al. Bacterial, viral, and fungal infection-related risk of Parkinson’s disease: meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. Brain Behav. 2020;10(3):e01549. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng L, Shen L, Ji HF. Impact of infection on risk of Parkinson’s disease: a quantitative assessment of case-control and cohort studies. J Neurovirol. 2019;25(2):221-228. doi: 10.1007/s13365-018-0707-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wijarnpreecha K, Chesdachai S, Jaruvongvanich V, Ungprasert P. Hepatitis C virus infection and risk of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30(1):9-13. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maurizi CP. Influenza caused epidemic encephalitis (encephalitis lethargica): the circumstantial evidence and a challenge to the nonbelievers. Med Hypotheses. 2010;74(5):798-801. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toovey S, Jick SS, Meier CR. Parkinson’s disease or Parkinson symptoms following seasonal influenza. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2011;5(5):328-333. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00232.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harris MA, Tsui JK, Marion SA, Shen H, Teschke K. Association of Parkinson’s disease with infections and occupational exposure to possible vectors. Mov Disord. 2012;27(9):1111-1117. doi: 10.1002/mds.25077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vlajinac H, Dzoljic E, Maksimovic J, Marinkovic J, Sipetic S, Kostic V. Infections as a risk factor for Parkinson’s disease: a case-control study. Int J Neurosci. 2013;123(5):329-332. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2012.760560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mattock C, Marmot M, Stern G. Could Parkinson’s disease follow intra-uterine influenza?: a speculative hypothesis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51(6):753-756. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.6.753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ebmeier KP, Calder SA, Besson JA. Psychiatric aspects of Parkinson’s disease. BMJ. 1989;299(6700):683. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6700.683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu B, Chen H, Fang F, Tillander A, Wirdefeldt K. Early-life factors and risk of Parkinson’s disease: a register-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Postuma RB, Wolfson C, Rajput A, et al. Is there seasonal variation in risk of Parkinson’s disease? Mov Disord. 2007;22(8):1097-1101. doi: 10.1002/mds.21272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Troyer EA, Kohn JN, Hong S. Are we facing a crashing wave of neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19? neuropsychiatric symptoms and potential immunologic mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:34-39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christiansen CF, Heide-Jørgensen U, Rasmussen TB, et al. Renin-angiotensin system blockers and adverse outcomes of influenza and pneumonia: a Danish cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(19):e017297. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Medications associated with parkinsonism for exclusion criteria.

eAppendix 2. Diagnosis codes used to identify exposures of interest.

eAppendix 3. Month-year ranges used for influenza exposure definitions derived from data from the Danish National Patient Registry.