ABSTRACT

Capsular polysaccharide (CPS) heterogeneity within carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CR-Kp) strain sequence type 258 (ST258) must be considered when developing CPS-based vaccines. Here, we sought to characterize CPS-specific antibody responses elicited by CR-Kp-infected patients. Plasma and bacterial isolates were collected from 33 hospital patients with positive CR-Kp cultures. Isolate capsules were typed by wzi sequencing. Reactivity and measures of efficacy of patient antibodies were studied against 3 prevalent CR-Kp CPS types (wzi29, wzi154, and wzi50). High IgG titers against wzi154 and wzi50 CPS were documented in 79% of infected patients. Patient-derived (PD) IgGs agglutinated CR-Kp and limited growth better than naive IgG and promoted phagocytosis of strains across the serotype isolated from their donors. Additionally, poly-IgG from wzi50 and wzi154 patients promoted phagocytosis of nonconcordant CR-Kp serotypes. Such effects were lost when poly-IgG was depleted of CPS-specific IgG. Additionally, mice infected with wzi50, wzi154, and wzi29 CR-Kp strains preopsonized with wzi50 patient-derived IgG exhibited lower lung CFU than controls. Depletion of wzi50 antibodies (Abs) reversed this effect in wzi50 and wzi154 infections, whereas wzi154 Ab depletion reduced poly-IgG efficacy against wzi29 CR-Kp. We are the first to report cross-reactive properties of CPS-specific Abs from CR-Kp patients through both in vitro and in vivo models.

IMPORTANCE Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae is a rapidly emerging public health threat that can cause fatal infections in up to 50% of affected patients. Due to its resistance to nearly all antimicrobials, development of alternate therapies like antibodies and vaccines is urgently needed. Capsular polysaccharides constitute important targets, as they are crucial for Klebsiella pneumoniae pathogenesis. Capsular polysaccharides are very diverse and, therefore, studying the host’s capsule-type specific antibodies is crucial to develop effective anti-CPS immunotherapies. In this study, we are the first to characterize humoral responses in infected patients against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae expressing different wzi capsule types. This study is the first to report the efficacy of cross-reactive properties of CPS-specific Abs in both in vitro and in vivo models.

KEYWORDS: carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, capsular polysaccharide, wzi capsule, patient-derived antibodies, CPS-specific antibodies, CPS-specific antibody, Klebsiella pneumoniae, carbapenem resistant, host-pathogen interactions, humoral immunity, patient-derived antibody, wzi typing

INTRODUCTION

Infections with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CR-Kp) are associated with high mortality rates (1). Thus, the World Health Organization (WHO) considers the development of novel therapeutics for CR-Kp a critical priority (2). A large prospective observational multicenter study demonstrated that the spread of CR-Kp in the United States is largely driven by the expansion of sequence type 258 (ST258) or related clonal lineages (clonal group 258 [CG258]) of CR-Kp. In that study, CG258 represented 74% of carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae isolates (3). The genome of ST258 strains is highly conserved, with two dominant subclades (clade 1 and clade 2) differing only by several hundred kilobases, and wzi gene-based capsular typing has shown the predominance of only a few capsular polysaccharide (CPS) subtypes (4–6). Specifically, clade 2 strains almost exclusively produce wzi154 CPS, whereas clade 1 strains chiefly produce wzi29 and wzi50 capsules, but can produce other capsular types as well (7, 8). Importantly, infection with wzi154/clade 2 strains has been associated with worse prognoses than infections by other strains (8–11).

The polysaccharide capsule of K. pneumoniae protects the pathogen from host cell-mediated killing and the bactericidal effect of serum, thus contributing to K. pneumoniae pathogenicity (12). Studies examining the efficacy of antibodies (Abs) directed against CR-Kp CPS have demonstrated their potency in human cells and animal models (13–17), and CPS vaccines have the potential to prevent or moderate the severity of CR-Kp infection in monkeys and decrease the prevalence and emergence of resistant strains (14, 18–20). However, it is unknown if natural antibody responses to K. pneumoniae rely on anticapsular responses. Given the heterogeneity of the CPS, it is important to understand whether diverse wzi CPS types are recognized differentially by the immune system during an infection. Furthermore, it is still unknown whether anti-CPS antibodies cross-react and cross-protect across clades that express CPS with different wzi types.

To understand whether vaccination with CPS constitutes a feasible strategy to elicit a protective immune response and mitigate CR-Kp emergence, we characterized the humoral response in a cohort of hospitalized patients infected or colonized with CR-Kp. We compared the Ab response elicited by different wzi capsule types (wzi29, wzi154, and wzi50) and assessed the protective opsonophagocytic efficacy of human anti-CPS polyclonal IgG against CR-Kp in vitro and in vivo. This study is the first to our knowledge to document anti-CPS humoral responses in patients infected with different CR-Kp strains that produce specific wzi-type CPS. Our data indicate for the first time a cross-reactive therapeutic potential of the wzi50 anti-CPS Abs. The implications of these findings for efforts to developing anticapsular therapeutics are discussed in this study.

(These data were presented in part at IDWeek 2019–IDSA, 2 to 6 October 2019, Washington, DC [21].)

RESULTS

Demographics and clinical variables.

We identified 36 patients who were hospitalized at Stony Brook University Hospital (SBUH) between 2017 and 2019 with bacterial cultures that grew CR-Kp. Plasma samples were obtained from 33, while 3 did not give consent. Of the 33 who consented, 23 met published criteria for “symptomatic infection with CR-Kp,” while 10 were classified as “asymptomatic infection or colonized with CR-Kp” (11). Both cohorts (infected and colonized with CR-Kp) were similar in age and gender distribution, but infected patients had a median length of stay (LOS) of 20.5 days (interquartile range [IQR] = 14 to 52.5 days; P < 0.0001), whereas colonized patients had a median LOS of 17 days (IQR = 8 to 33 days; P = 0.0003). Subsequently, the median time to first positive culture from the day of admission was longer for infected patients compared to colonized patients (7.5 versus 3 days, respectively). Capsular serotyping by wzi sequencing showed 12 isolates to be wzi154, 10 to be wzi29, 2 to be wzi50, and 9 to be of other wzi types (Table 1). wzi154, wzi29, and wzi50 were previously identified as the most common wzi types among ST258 isolates in the New York City area (7).

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Infected | Colonized |

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of consenting patients | 23 (69.7) | 10 (30.3) |

| Median age (yrs) | 70 (37 to 86 yrs) | 66.5 (23 to 88 yrs) |

| Gender (n) | ||

| Male | 13 | 7 |

| Female | 10 | 3 |

| Median (range) length of hospital stay (days) | 20.5 (5 to 262) | 17 (4 to 99) |

| Median no. (range) of hospital days blood culture was positive for CR-Kp | 7.5 (0 to 145) | 3 (0 to 80) |

| Source (n) of isolates | Urine (9), blood (4), respiratory (5), other (abdominal fluid [4], penial wound [1]) | Urine (7), blood (0), respiratory (2), other (rectal swab [1]) |

| wzi types (n) | ||

| wzi29 | 7 | 3 |

| wzi154 | 7 | 5 |

| Other | wzi26 (1), wzi101 (1), wzi50 (1), wzi60 (1), wzi96 (1), wzi173 (3), wzi355 (1) | wzi7 (1), wzi50 (1) |

Anti-CPS antibody responses in clinical patient samples.

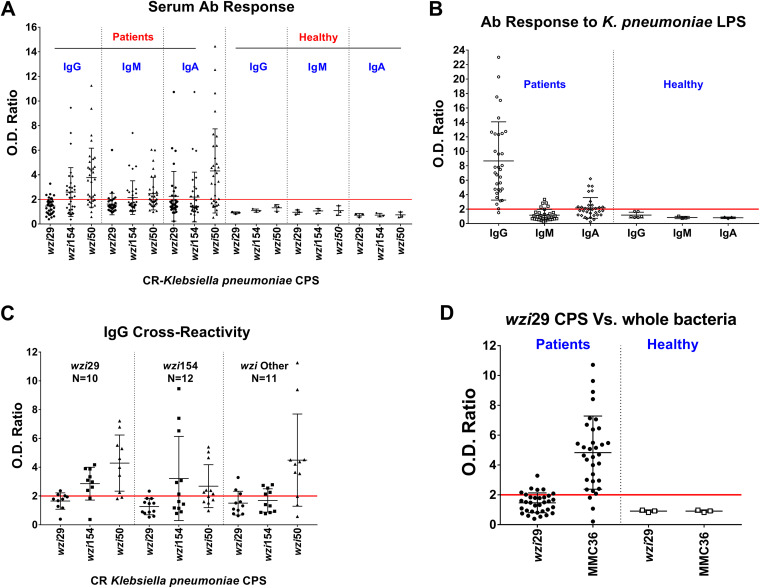

Patient Ab responses to wzi29, wzi54, and wzi50 CPS were measured by enzyme-limited immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and indicated the highest overall IgG responses to wzi50 CPS, followed by those to wzi154 CPS. We also observed minimal IgG response to wzi29 CPS and that 7 plasma samples lacked any CPS reactivity (Fig. 1A). IgM and IgA titers showed similar trends (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The magnitudes of IgG, IgM, and IgA responses against wzi29 and wzi154 were comparable regardless of the state of CR-Kp infection (“infected” versus “colonized”). In contrast, higher IgA titers against wzi50 CPS were only observed in symptomatic patients (Fig. S1). Plasma (n = 33) was also tested for anti-lipopolysaccharide (anti-LPS) Abs, which have also been observed to be protective (22). Both cohorts exhibited high IgG and low IgA and IgM reactivity against LPS in plasma (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Humoral responses to capsular polysaccharides (CPS) and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) isolated from carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae. (A) Humoral antibody (Ab) (IgG, IgM, and IgA) responses detected against wzi29, wzi154, and wzi50 CPS in carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CR-Kp)-infected patients versus healthy controls. (B) Presence of antibodies against K. pneumoniae LPS in all CR-Kp patients and healthy donors. (C) Antibodies of patients infected with wzi29 K. pneumoniae tested against all three CPS types. wzi154-infected patients’ antibodies tested against all three CPS. Antibodies from patients infected with other wzi-type CR-K. pneumoniae strains tested against all three CPSs. (D) Presence of antibodies against wzi29 whole bacteria in CR-Kp-infected patient plasma Abs versus healthy donors compared to purified wzi29 CPS. Each symbol represents one patient. Optical density (OD) ratio = OD CPS/OD bovine serum albumin (BSA). The fold change cutoff is set at y = 2 (red line); patients with the presence of anti-CPS Abs in the plasma had values of ≥2, whereas patients with undetectable level of anti-CPS Abs in plasma had values of <2. N = 33; each dot on the scatterplot represents an individual CR-Kp patient’s OD ratio, and the deviations in OD ratios are shown as standard deviations (SD).

Antibody responses in “infected” versus “colonized” carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CR-Kp) patients to capsular polysaccharides (CPS) isolated from CR-Kp strains. Humoral responses to CPS were independent of the patient’s clinical status. Optical density (OD) ratio = OD CPS/OD bovine serum albumin (BSA). The positive cutoff is set at y = 2 (red line); positive sera had values of ≥2, and negative sera had values of <2; N = 33; each dot on the scatter plot indicates an individual CR-Kp patient’s OD ratio, and the deviations in OD ratios are shown as standard deviations (SD). Download FIG S1, TIF file, 1.7 MB (1.7MB, tif) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Antibody responses to capsular polysaccharides (CPS) and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) isolated from carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae. IgM response (A) and IgA response (B) to wzi29, wzi154, and wzi50 CPS were compared in CR-Kp patients. OD ratio = OD CPS/OD BSA. The positive cutoff is set at y = 2 (red line); positive sera had values of ≥2, and negative serum had values of <2; each dot on the scatter plot indicates an individual CR-Kp patient’s OD ratio, and the deviations in OD ratios are shown as SD. Download FIG S2, TIF file, 1.4 MB (1.4MB, tif) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Importantly, no Ab reactivity with CPS or LPS was detected in the plasma of healthy individuals, thus suggesting Ab responses were elicited during the recent CR-Kp infection (Fig. 1A and B).

Knowing the wzi type of the CR-Kp strains infecting the patients permitted further subanalysis of Ab reactivity. Notably, no wzi29-specific IgG was detected in the plasma of patients infected with wzi29 CR-Kp (Fig. 1C), although those patients produced cross-reactive Abs that bound to wzi154 (50%) and wzi50 (88%) CPS (Fig. 1C). While 50% of patients infected with wzi154 CR-Kp mounted an Ab response to wzi154 CPS, 67% of those patients also exhibited cross-reactive IgG Abs to wzi50 CPS (Fig. 1C). Similarly, while 81% of patients infected with CR-Kp strains with other wzi CPS (including both wzi50-infected patients) produced IgGs that recognized wzi50 CPS, only low Ab titers binding wzi29 and wzi154 CPS were observed (Fig. 1C). No IgM reactivity to any CPS type were observed in patients infected with wzi29 CR-Kp (Fig. S2A), whereas few patients infected with CR-Kp strains with wzi29- and wzi154-type CPS had low IgA titers to wzi29-type CPS (Fig. S2B). Lack of any IgG response to wzi29-type CPS raised the concern that the immunogenic epitopes were destroyed during purification, and therefore ELISA was done with whole bacteria, which confirmed that most patients’ plasma bound to whole wzi29 MMC36 bacteria (Fig. 1D). Isotype subclass analysis showed that anti-CPS Abs included IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4 isotypes, whereas anti-LPS Abs were all IgG2 (Fig. S3).

IgG subclass (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4) responses to capsular polysaccharides (CPS) and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae-infected patients (N = 33). O.D. Ratio = (O.D. CPS/O.D. BSA). The positive serum had the value ≥2 and negative serum is <2; bars depict means and SD from three independent experiments, with wells performed in triplicate. Download FIG S3, TIF file, 0.9 MB (959.8KB, tif) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Cross-agglutination and serum killing of CR-Kp by patient-derived IgGs.

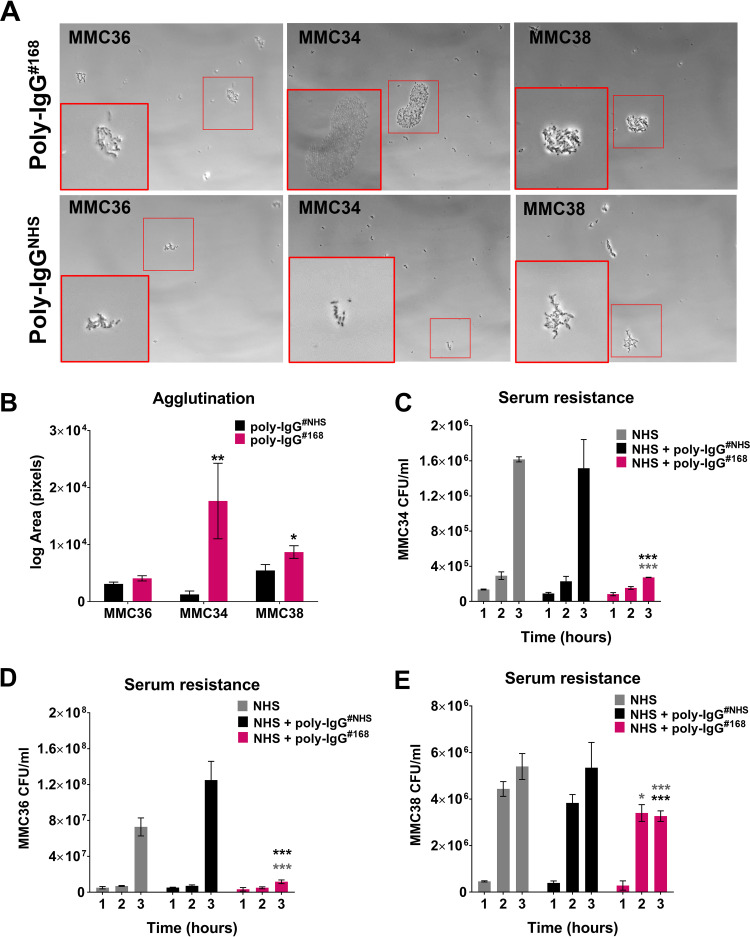

To further explore anticapsular antibody immunity against CR-Kp, we examined agglutination and serum resistance of bulk IgG purified from the plasma of a patient who possessed high anti-CPS titers (optical density [OD] > 0.6). First, we tested the ability of poly-IgG#168 (purified from a patient infected with wzi50-producing SBU168) to agglutinate CR-Kp strains with different CPS types (Fig. 2A and B). Our data showed that poly-IgG#168 agglutinated CR-Kp strains MMC34 (wzi154), MMC36 (wzi29), and MMC38 (wzi50) (Fig. 2A). The extent of agglutination (average area of agglutinated clumps) was quantified by ImageJ software and was found to be significant for strains MMC34 and MMC38 compared to bacteria treated with IgG derived from normal human serum (poly-IgGNHS) (unpaired t test, P = 0.0040) (Fig. 2B). Next, serum resistance or killing was evaluated over a 3-h incubation time. CR-Kp strains differ in their resistance to complement-mediated killing, whereby some strains can be killed, whereas for other strains only growth is inhibited (7). For the complement-sensitive strain MMC34, at 3 h poly-IgG#168 killed 75% of the bacteria (P < 0.0001) in 75% normal human serum compared to normal human serum (NHS) and poly-IgGNHS controls (Fig. 2C). Our data indicate that coincubation of poly-IgG#168 significantly impaired the growth of MMC36 in 75% NHS (Fig. 2D) compared to serum with nonspecific poly-IgGNHS (P < 0.0001). MMC38 treated with poly-IgGNHS had an overall 145% growth increase, whereas negligible growth was observed in MMC38 treated with poly-IgG#168 during the time interval of 2 and 3 h (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2E).

FIG 2.

Patient antibodies promote agglutination and decrease serum resistance. (A) wzi50 patient-derived (PD) IgGs promoted agglutination of wzi29 MMC36, wzi154 MMC34, and wzi50 MMC38 strains, which was visualized with phase-contrast microscopy at ×200 magnification. (B) Quantification of the area of agglutinated bacteria. wzi50 PD IgGs (poly-IgG#168) (C) mediated serum killing of wzi154 MMC34, (D) inhibited the growth of wzi29 MMC36, and (E) inhibited the growth of wzi50 MMC38 strains, with respect to CR-Kp strains treated with poly-IgG#NHS in 75% natural human serum (NHS). Bars depict means and SD from three independent experiments. Overall differences between treatment groups were determined to be significant by repeated-measures two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Tukey’s post hoc test, displayed in-graph. For all in-graph statistics, P values displayed in gray are comparisons to the NHS-only control group, whereas P values in black are comparisons to the poly-IgG#NHS treated group. P values are indicated as “ns” if >0.1, * if < 0.05, ** if <0.01, and *** if <0.001.

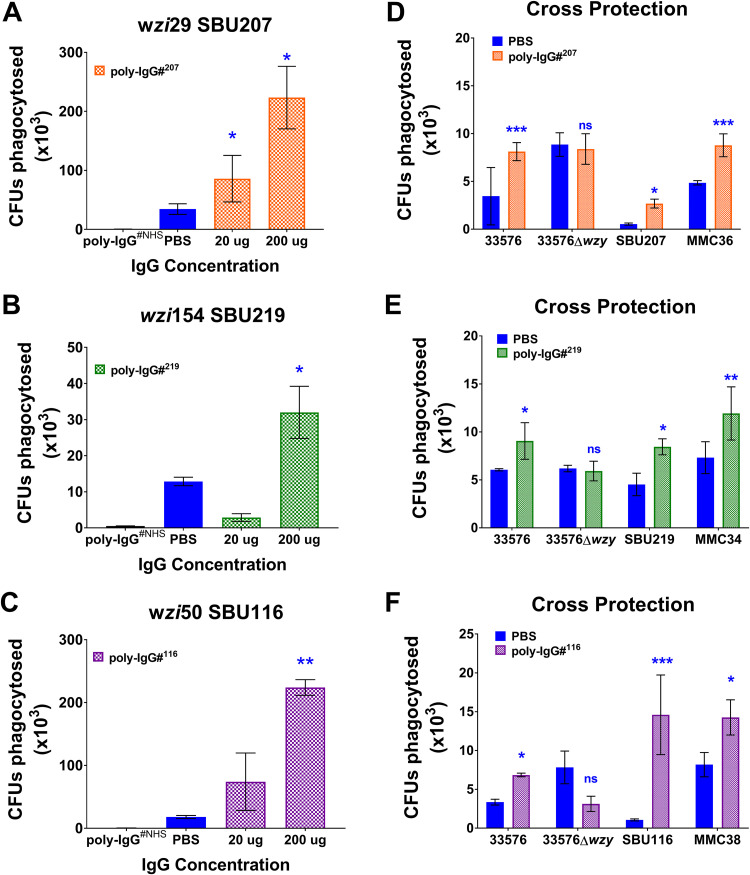

Opsonophagocytosis of clinical CR-Kp isolates by patient-derived poly-IgG.

A key attribute commonly associated with the efficacy of CPS-specific Ab-mediated immunity is opsonophagocytosis (23, 24). To assess the efficacy of different patient-derived (PD) poly-IgGs, we performed opsonophagocytosis experiments in J774 macrophages with Poly-IgG#207, poly-IgG#219, and poly-IgG#116 purified from patients infected with SBU219 (wzi154), SBU116 (wzi50), and SBU207 (wzi29). Opsonophagocytosis of respective CR-Kp clinical isolates was promoted in a dose-dependent matter by all 4 poly-IgGs compared to both poly-IgG#NHS and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) controls (Fig. 3A to C and Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Due to the limited quantity of poly-IgG#168, investigations were continued with poly-IgG#116, which was also derived from a patient infected with wzi50-producing CR-Kp. Poly-IgG#207 promoted opsonophagocytosis of two different wzi29 strains, SBU207 and MMC36 (Fig. 3D). In a similar fashion, poly-IgG#219 (Fig. 3E) and poly-IgG#116 (Fig. 3F) induced opsonophagocytic uptake of MMC34 and SBU219 (both wzi154); and MMC38 and SBU116 (both wzi50) strains, respectively. Interestingly, while poly-IgGs promoted phagocytosis of capsular strains, including that of 33576 (wzi154), it did not mediate phagocytosis of its acapsular 33576 Δwzy mutant (Fig. 3D to F). These data suggest that anti-CPS Abs in PD poly-IgGs convey opsonophagocytic efficacy and also indicate the presence of cross-reactive anti-CPS Abs.

FIG 3.

Coincubation with patient-derived IgGs induces opsonophagocytosis of clinical K. pneumoniae strains. PD IgGs isolated from patients 207 (wzi29), 219 (wzi154), and 116 (wzi50) induced opsonophagocytosis of patient-matched K. pneumoniae (A) SBU207 (wzi29), (B) SBU219 (wzi154), and (C) SBU116 (wzi50) strains, respectively. PD IgGs (D) poly-IgG#207, (E) poly-IgG#219, and (F) poly-IgG#116 broadly recognized and induced opsonophagocytosis of strains with similar wzi type and also cross-reacted with 33576 clade 2 K. pneumoniae capsular strain but did not mediate phagocytosis of the acapsular 33576 Δwzy mutant strain. Bars depict means and SD from three independent experiments, with wells performed in triplicate. poly-IgG#NHS and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) serve as the negative controls for the assay. Phagocytosed bacteria within macrophages were counted by plating lysed macrophages (log CFU phagocytosed) on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates. Overall differences between treatment groups were determined to be significant by repeated-measures two-way ANOVA using Tukey’s post hoc test, displayed in-graph. For all in-graph statistics, P values displayed in blue are comparisons to the PBS control. P values are replaced with ns if >0.1, * if < 0.05, ** if <0.01, and *** if <0.001.

PD-IgGs isolated from patient 168 (wzi50) induced opsonophagocytosis of patient-matched SBU168 strain. Bars depict means and SD from three independent experiments, with wells performed in triplicate. poly-IgG#NHS and PBS serve as the negative controls for the assay. Phagocytosed bacteria within macrophages were counted by plating lysed macrophages (log CFUs phagocytosed) on LB agar plates. Overall differences between treatment groups were determined to be significant by repeated-measures two-way ANOVA using Tukey's post-hoc test displayed in-graph. For all in-graph statistics, P values displayed in blue are comparisons to the PBS control. ** signifies P < 0.01. Download FIG S4, TIF file, 0.9 MB (937KB, tif) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

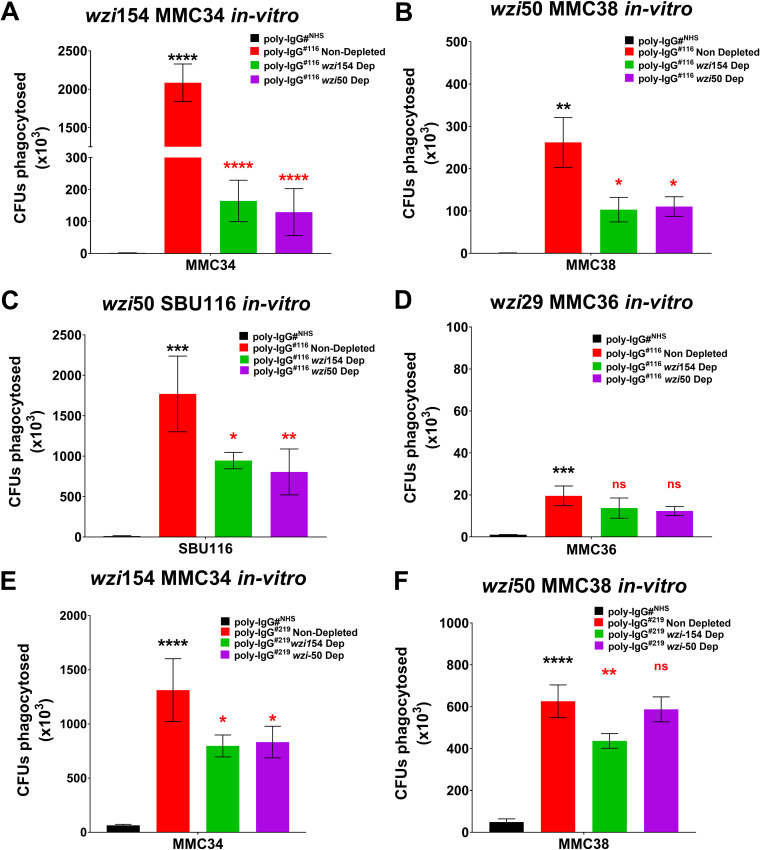

Relevance of anticapsular antibodies for opsonophagocytic efficacy.

To test if the protective Abs are anti-CPS, we depleted poly-IgG#116 and poly-IgG#219 of wzi154 and wzi50 CPS-specific Abs by coincubation with corresponding CPS-coated beads. Ab-mediated opsonophagocytosis of 4 CR-Kp strains producing distinct wzi types (wzi29, wzi154, and wzi50) was compared to that of nondepleted poly-IgG#116 and poly-IgG#NHS. Data confirmed significant augmented phagocytosis of all 4 CR-Kp strains (Fig. 4A to D) compared to poly-IgG#NHS. For MMC34, MMC38, and SBU116 phagocytosis was significantly lower when PD bulk IgGs were depleted with wzi154-CPS-coated beads (92%, 58%, and 44% loss in efficacy, respectively). Whereas, when 116 PD bulk IgGs were depleted with wzi50-CPS-coated beads, 94%, 59%, and 50% losses in efficacy were observed for MMC34, MMC38, and SBU116, respectively (Fig. 4A to C). Depletion of CPS-specific Abs from poly-IgG#116 did not affect opsonophagocytosis of the wzi29 MMC36 strain (Fig. 4D). Similar results were observed when wzi154-specific Abs were depleted from bulk poly-IgG#219, resulting in 40% and 30% loss in phagocytic efficacy for MMC34 and MMC38, respectively (Fig. 4E and F), whereas depletion of wzi50-specific Abs only affected the phagocytosis of MMC34 (36% loss) (Fig. 4E). Depletion of either anti-CPS Ab did not affect the phagocytosis of MMC36 (data not shown).

FIG 4.

Depletion of CPS-specific antibodies inhibits opsonophagocytosis of corresponding K. pneumoniae. The PD IgGs poly-IgG#116 and poly-IgG#219 provided cross-protection against all clade types (including clade 1 and clade 2). Depletion of wzi154 and wzi50 CPS-specific IgGs from poly-IgG#116 significantly inhibited opsonophagocytosis of (A) wzi154 MMC34, (B) corresponding wzi50 MMC38, and (C) patient-matched SBU116 strains, but (D) the effect on opsonophagocytosis of wzi29 MMC36 was negligible. Depletion of wzi154 and wzi50 CPS-specific IgGs from poly-IgG#219 significantly inhibited opsonophagocytosis of (E) the corresponding wzi154 MMC34 strain, whereas (F) depletion of wzi154 CPS only inhibited the opsonophagocytosis of wzi50 MMC38. Bars depict means and SD from three independent experiments, with wells performed in triplicate. poly-IgG#NHS serve as the negative controls for the assay. Phagocytosed bacteria within macrophages were counted by plating lysed macrophages (log CFU phagocytosed) on LB agar plates. Overall differences between treatment groups were determined to be significant by repeated-measures two-way ANOVA using Tukey’s post hoc test, displayed in-graph. For all in-graph statistics, P values displayed in black are comparisons to the poly-IgGNHS group, whereas P values in red compare nondepleted poly-IgGs with wzi154- and wzi50-depleted Abs. P values are replaced with ns if >0.1, * if <0.05, ** if <0.01, and *** if <0.001.

Reduced protective efficacy of depleted PD poly-IgG in a murine infection model.

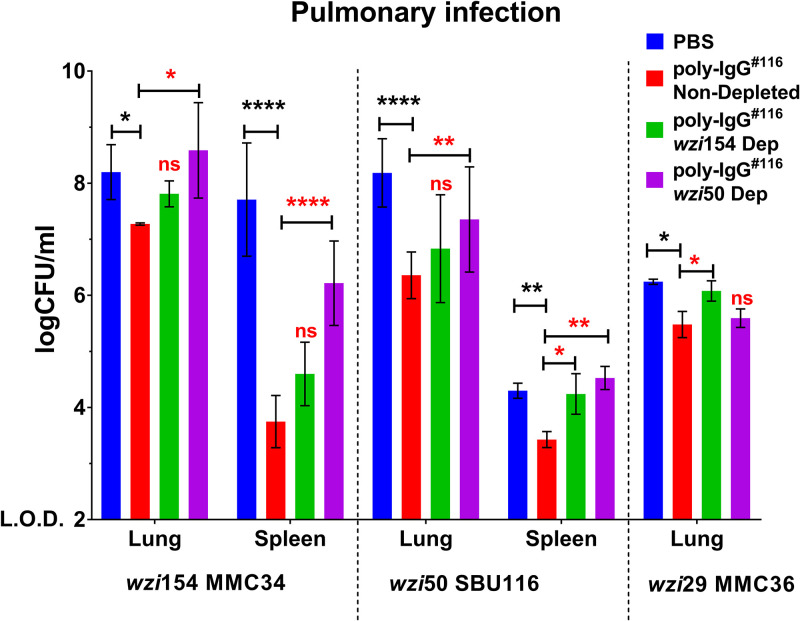

Last, we explored if cross-reactive Abs could protect mice from CR-Kp infection. We compared CFU in a mouse pulmonary model infected with different CR-Kp strains (MMC34, SBU116, and MMC36), preopsonized with either undepleted or depleted poly-IgG#116. Mice injected with poly-IgG#116-opsonized MMC34 exhibited a moderate 1-log10 reduction in bacterial lung burden, as well as a 4-log10 reduction in dissemination to the spleen. (Fig. 5). A 2-log10 and a 1-log10 reduction in lung and spleen CFU, respectively, were seen in mice infected with poly-IgG#116-opsonized SBU116. Depletion of wzi50-specific Abs resulted in 1-log10 higher CFU in both lung and spleen compared to undepleted treatment, whereas wzi154-specific Ab depletion only affected dissemination to the spleen compared to undepleted treatment (Fig. 5). A significant, albeit small, decrease in lung CFU was observed in mice infected with MMC36 preopsonized with poly-IgG#116, but no dissemination to the spleen was observed in either of the experimental groups. Furthermore, the bacterial burden in the lung was identical between the wzi154-depleted group and the PBS control (Fig. 5).

FIG 5.

Passive transfer of purified human polyclonal IgG from CR-Kp-infected subjects reduces K. pneumoniae bacterial burden in CR-Kp-infected mice, whereas specific CPS depletion (Dep) reverses the therapeutic effect. Bacterial burden in lungs and spleens of mice infected with a lethal inoculum of MMC34, SBU116, and MMC36 strains preopsonized with either CPS-specific depleted or nondepleted PD IgGs. For all studies, bars depict means, and SD for overall differences in CFU between treatment groups (n = 3 per group) were assessed for significance by two-way ANOVA with multiple-comparison correction and the limit of detection (LOD) set at y = 2. For all in-graph statistics, P values displayed in black are comparisons to the PBS group, whereas P values in red compare nondepleted poly-IgGs with wzi154- and wzi50-depleted Abs. P values are replaced with ns if >0.1, * if <0.05, ** if <0.01, and *** if <0.001.

DISCUSSION

Prior studies in mice and monkeys provide compelling evidence that CPS-specific Abs are effective against CR-Kp (15, 16, 19, 25). Several groups have developed vaccines that target CPS to prevent K. pneumoniae infection (16, 26–28). However, concerns regarding feasibility prevail because of the heterogeneity of the polysaccharide capsule (7). These data constitute the first analysis of the anti-CPS Ab response in CR-Kp-infected patients. Several important conclusions can be drawn from our data. First, most CR-Kp-infected patients mount a humoral response to the polysaccharide capsule, although it is more variable in its magnitude than Ab reactivity to LPS. Second, CPS-specific Abs cross-react with other capsule types. Third, protective Abs were specific to CPS. Last, poly-IgG from CR-Kp infected patients can protect CR-Kp-infected mice, and loss of efficacy is observed after depletion of CPS-specific Abs.

Our data represent an unbiased analysis of the Ab response in CR-Kp-infected patients, as the cohort included the majority of hospitalized patients diagnosed with CR-Kp infection during the studied time period. Although colonized patients were diagnosed earlier and spent less time in the hospital, there were no striking differences with respect to their CPS-specific Ab responses. Although the findings could indicate that the naturally evolving humoral response is not sufficient in eradicating these organisms, this observational study did not systematically assess if colonized patients ultimately cleared Klebsiella. Instead, we chose to further analyze the Ab response to the three most common wzi types of ST258 strains. The wzi154 CPS type is expressed by most clade 2 strains, wzi29 is the most prevalent CPS expressed by clade 1 strains, and wzi50 can be expressed by clade 1 as well as clade 2 strains (7, 8, 29). Interestingly, three of the seven patients who did not mount a CPS-specific Ab response were infected with less common wzi types (wzi173 and wzi7).

Despite the CPS variability in CR-Kp, plasma from many of the patients reacted to more than one CPS. This was not necessarily expected because the structure of wzi154 (MMC34) is distinct from other published K. pneumoniae CPS structures (30), and its sugar composition is also very different from that of wzi50 (7). Regardless, about half of the patients infected with wzi154 CR-Kp strains mounted high titers to wzi154 and wzi50 CPS. Interestingly, plasma derived from patients infected with wzi29 CR-Kp exhibited the most pronounced cross-reactivity with other wzi types, but no reactivity with wzi29 CPS. Although this result was consistent with published studies reporting failure of wzi29 CPS to elicit Abs in mice or rabbits (16, 17), it was not in accord with results from in vitro phagocytosis assays. They indicated opsonophagocytic efficacy of PD poly-IgG of wzi29 CR-Kp strains, whereas acapsular mutants were not phagocytosed, consistent with the presence of Abs specific for wzi29-type CPS. Although these results are not conclusive, a modified ELISA demonstrating Abs to whole wzi29 CR-Kp further supports the conclusion that wzi29-type CPS indeed elicits Abs. We hypothesize that critical CPS epitopes are destroyed during CPS purification, and better methods to purify CPS are needed. Cross-reactive Abs have been identified in the serum of volunteers vaccinated with CPS derived from different K. pneumoniae strains (31). Such cross-reactivity may be the result of cocktails of distinct Abs that bind to different antigens or, alternatively, some Abs could react with more than one CPS. Indeed, one study reported that 12% of human MAbs cloned from subjects vaccinated with 23-valent Pneumovax cross-reacted with two serotypes (32). Although our murine monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) exclusively bind to wzi154-type CPS, one could potentially clone hybridomas that produce cross-reactive Abs through modified vaccination protocols and altered screening procedures.

Importantly, healthy subjects did not exhibit Ab reactivity with Kp-derived CPS or LPS, indicating that these Ab reactivities are the result of infection and colonization with CR-Kp. Further studies will need to resolve if CPS-specific IgA is present in the colon. Interestingly, the dominance of a specific IgG subclass was not observed for CPS-specific Abs, whereas the LPS of Klebsiella elicited predominantly IgG2 response. Although one vaccine study in mice with CR-Kp oligosaccharides identified the murine subclass mIgG1 to be the most seroprevalent in those mice (33), human IgG2, which is similar to the analogous murine isotype (mIgG3), is the primary humoral response to T-independent antigens such as CPS. This IgG subclass preference was also observed in humans infected with Helicobacter pylori and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (34, 35).

Abs directed against the O polysaccharide are protective against wild-type Kp in lethal infection models (36, 37). Abs that bind to LPS have not only been shown to be opsonophagocytic but also cross-reactive (22). We do not believe that cross-contamination of CPS with LPS is responsible for the cross-reactivity in our patient plasma because highly sensitive tests were used to rule out LPS contamination during CPS purification, which was done according to standard protocols (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Furthermore, cross-reactivity was not observed with all patient plasma. Last, experiments with acapsular mutants, as well as studies with bulk plasma that was depleted of CPS-specific Abs, were performed to show the causal role of anti-CPS antibodies in opsonophagocytic efficacy and document their respective cross-reactivity. The first set of experiments demonstrate that bulk IgG promotes agglutination of two CR-Kp strains (wzi50 and wzi154) and enhances serum resistance in all three Klebsiella strains, which differ in agglutination and serum resistance (12, 16, 17). Ab-mediated complement deposition of C5b-9 and C3c has been shown to be critical for Ab activity (16). Enhancement of opsonophagocytic efficacy by two different high-titer IgG bulk fractions demonstrated that enhancement of phagocytic activity was mediated by CPS-specific Abs and lost after depletion. Again, cross-reactivity was observed for MMC34 (wzi154), as both depletion of wzi50 and of wzi154-specific Abs affected the phagocytic efficacy.

In vivo efficacy of poly-IgG#116 in a pulmonary infection model further supports our conclusion that infected patients generate a protective humoral immune response and that CPS-specific Abs are relevant Abs in both bulk IgG fractions. PD poly-IgG#116 lowered bacterial burden in the lung and dissemination to the spleen in mice infected with MMC34, MMC36, and MMC38, which expressed wzi154-, wzi29-, and wzi50-type CPS, respectively. Importantly, protective efficacy was reversed when CPS-specific Abs were depleted, underscoring their relevance. Regrettably, CR-Kp strains exhibit low virulence, and in vivo experiments continue to be a challenge in mice (16, 38) and even in cynomolgus macaques (19). Our laboratory is actively pursuing studies to investigate if anticapsular Abs can also be given prior to infection and prevent disseminated disease. One of the major limitations of the current animal model is that high inocula are required to measure the effect on dissemination. Historically, murine models have used more virulent Klebsiella strains, which require several log lower inocula to kill mice. Recent advances with a neutropenic murine model could potentially allow experiments with lower inocula (39).

In summary, despite marked capsular heterogeneity, our results demonstrate that infection with CR-Kp induces cross-reactive anti-CPS Abs. The finding that most (79%) elderly patients, irrespective of their state of infection, mounted an Ab response to at least one of the three CPS underscores the immunogenicity of CPS and indicates the feasibility of a CPS-based vaccine strategy that targets the elderly, who are also the most vulnerable. A limitation of the study was that the long-term persistence of IgG was not evaluated. However, limited uncontrolled data from healthy subjects who have IgG to Klebsiella CPS indicated that the humoral response persists for months. In contrast to S. pneumoniae, CR-Kp colonization is not yet widely spread in the community, and the majority of patients still become colonized through nosocomial exposure in diverse health care settings (40, 41). Recent advances with recombinant production of bioconjugate vaccines in glycoengineered Escherichia coli cells against the 2 K. pneumoniae serotypes, K1 and K2, could improve the generation of multivalent CPS-based vaccines (25). Our data indicate that vaccines with wzi154, wzi29, and wzi50 could potentially give broad coverage, which is preferable because, similarly to pneumococcal vaccines, non-vaccine CPS types could increase in prevalence after vaccine introduction (42, 43). In summary, our results encourage efforts to further develop CPS-based vaccines. Furthermore, these data suggest that certain CPS may elicit more cross-reactive Abs, but care has to be taken when purifying CPS to conserve immunogenic epitopes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

Animal study protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Stony Brook University (SBU; approval no. 628253). This study is in strict accordance with federal, state, local, and institutional guidelines that include the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the Animal Welfare Act, and the Public Health Service Policy on Human Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All surgery was performed under ketamine-and-xylazine anesthesia, and every effort was made to minimize suffering. Patients consented under institutional review board (IRB)- and SBU Human Subjects Committee-approved protocols (IRB no. 896845 and 851803). Healthy donors gave written informed consent for blood donation under IRB no. 718744.

Collection of plasma and CR-Kp from patients.

Patients admitted to Stony Brook University Hospital (SBUH) from 2017 to 2019, from whom CR-Kp was isolated, consented and their CR-Kp strains and plasma were collected and frozen at −80°C and −20°C, respectively. Patients were classified as being “colonized” or “infected” based on standard criteria described elsewhere (11).

CR-Kp strain isolation, wzi typing, and purification of capsular polysaccharide.

CR-Kp strains were identified by standardized methods according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), as well as revised CDC criteria (3), and wzi typed according to published protocols (5). For experiments, CR-Kp strains isolated from patients, as well as MMC36 (wzi29), MMC34 (wzi154), and MMC38 (wzi50) (7), were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and agar at 37°C (7).

The CPS of the three previously characterized strains was purified for ELISA and depletion studies based on a previously described protocol in Supplemental Methods S1 of Diago-Navarro et al. (15). Briefly, overnight cultures in 1 liter of LB broth were pelleted by centrifugation, washed with PBS, and resuspended to 5% (wt/vol) in distilled water. CPS was extracted by phenol-water in the aqueous phase and precipitated by adding 5 volumes of methanol plus 1% (vol/vol) of saturated solution of sodium acetate for 2 h at −20°C. After dissolving the pellet in water and dialyzing it against water, it was lyophilized. Proteins and nucleic acid contaminants were removed by digesting them with proteinase K (50 mg/ml) and nucleases (50 mg/ml of DNase I and RNase A) twice for 24 h. LPS was removed by ultracentrifugation (105,000 × g, 16 h, 4°C), and samples were freeze-dried. CPS was further extracted with phenol and was further purified by a size exclusion chromatography on an S-200 HR column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) with PBS. Fractions were collected, and the presence of polysaccharide was analyzed by the phenol-sulfuric acid method (15).

To ensure that the purified CPS samples were devoid of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), we performed a sodium deoxycholate (DOC)-PAGE analysis that can detect up to 0.5 ng endotoxin per ml of sample. DOC-PAGE analysis was done with both LPS (L4268; Sigma-Aldrich) and purified CPS samples (200 ng and 100 ng). LPS contamination was detected by silver nitrate staining (44). LPS was not detected in the gel for CPS samples (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Absence of LPS (<20 endotoxin units [EU]/ml endotoxin limit for polysaccharide vaccines [45]) in purified CPS was further confirmed by the standard Pierce LAL chromgenic endotoxin kit (Thermo Scientific), which is more sensitive and has a lower detection limit of 0.01 EU/ml (0.01 ng endotoxin per ml) (Fig. S5) (19).

Endotoxin levels in isolated CPS samples. Positive-control LPS (Sigma Aldrich) and isolated samples were analyzed by the sodium deoxycholate (DOC)-PAGE method. Aliquots (200 ng and 100 ng) of each sample were loaded on the gel, and endotoxin (LPS) contamination was visualized by silver nitrate staining. Standard curve of limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) assay and amount of endotoxin levels present in 200 ng of CPS samples purified from MMC34, MMC36, and MMC38 strains. Download FIG S5, PDF file, 0.1 MB (97.1KB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Detection of anti-CPS and anti-LPS antibodies in plasma by CPS or LPS ELISA.

ELISAs described previously (15) were employed to detect circulating CPS Abs in the plasma of patients. Plasma samples were added in 1:50 dilution (determined by titration, 1:25 to 1:150) for all ELISAs, and secondary anti-human IgG, IgM, IgA, and IgG subclass antibodies were used for detection. The presence of CPS-specific Abs was defined by an OD ratio value of ≥2 (OD ratio = optical density at 405 nm [OD405] CPS/OD405 bovine serum albumin [BSA]), where an OD ratio value of <2 was considered nonspecific. For detection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-specific Abs, a similar ELISA was done using K. pneumoniae LPS purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (L4268).

Bulk IgG isolation.

Bulk patient-derived poly-IgGs (PD IgGs) were purified from plasma of patients infected with SBU116, SBU168, SBU207, or SBU219 or normal human serum (NHS) (H4522; Millipore Sigma) by negative selection using Melon gel resin (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Bulk IgGs were quantified using the Human IgG ELISA development kit (Mabtech).

Bulk IgG serum resistance assay and rapid agglutination assay.

A human serum resistance assay was done with poly-IgG#168 (40 μg/ml) by modifying the protocol described in (46). Agglutination assays of MMC34, MMC36, and MMC38 strains were carried out with NHS-derived IgG (poly-IgGNHS) or with PD IgGs isolated from a patient infected with SBU168 (40 μg/ml) as described previously (15, 16). Briefly, 3 × 106 CR-Kp strains were incubated with poly-IgG#168 in 75% NHS at 37°C for 0-, 1-, 2-, and 3-h time intervals. At each interval, samples were diluted serially and plated on LB plates. The experiment was repeated thrice.

Agglutination assays of MMC34, MMC36, and MMC38 strains were carried out with NHS-derived IgG (poly-IgGNHS) or with PD IgGs isolated from a patient infected with SBU168 (40 μg/ml) as described previously (15, 16). Agglutination was captured in phase-contrast at a magnification of ×200 with a Zeiss deconvolution microscope, and images were analyzed with ImageJ software. The experiment was repeated thrice.

Whole-cell ELISA.

A whole-bacterium ELISA (25) was used to detect Abs to wzi29-type CPS-expressing MMC36. Briefly, half of the 96-well plates (48 wells) were coated with 8 × 108 CFU · ml−1 of wzi29 MMC36 strain in methanol for 24 h. After 24 h, the plate was blocked with 2% BSA, and a standard anti-CPS ELISA was performed. Presence of Abs in plasma was defined as an OD ratio value of ≥2, and plasma with an OD ratio value of <2 was considered to have no/negligible anti-MMC36 antibodies.

Biotinylation of capsular polysaccharides and depletion of CPS-specific IgGs.

CPS biotinylation was done by adapting a protocol described previously (47). Briefly, purified CPS was constituted in endotoxin-free water at 1 mg/ml concentration. Two hundred microliters of sodium periodate (100 mM) were added per 1 mg CPS, and the solution was incubated for 6 h. Then, 100 μl of 25% glycerol was added to react with excess sodium periodate, and the solution was left at room temperature in the dark for 2 h. After periodate cleanup, the reaction mixture was passed through two Bio-Gel P-2 minicolumns (catalog no. 1504114; Bio-Rad) by centrifugation (3,000 rpm, 2 min) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Biotin-hydrazide (SP-1100; Vector Laboratories) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 50 mg/ml. For labeling, 40 μl (2 mg) of this solution was mixed with 1 mM manganese dichloride per 1 ml of CPS solution and incubated overnight at room temperature. Modified polysaccharides were then passed through two Bio-Gel P-2 minicolumns and reduced with 1 mM sodium borohydride for 5 min at room temperature. The reduced polysaccharide was passed through two Bio-Gel P-2 minicolumns, and the level of biotinylation was detected with a Pierce biotin quantitation kit (catalog no. 28055; Thermo Scientific).

Pierce NeutrAvidin agarose beads (200 μl, catalog no. 29200; Thermo Fisher Scientific) were coated with 1 mg/ml biotinylated CPS at 4°C for 16 h. Coated beads were washed with 2 column volumes of PBS (pH 7.4) and then incubated with bulk PD IgGs at 4°C for 16 h. Beads were washed with 2 column length volumes (2 ml) of PBS (Corning), and the CPS-depleted pools were eluted with PBS for further use. Depletion was confirmed by CPS ELISA before use in further experiments.

Macrophage phagocytosis.

Macrophage cell line J774A.1 (ATCC) was used for macrophage phagocytosis assays with bulk PD poly-IgGs (40 μg/ml) using published protocols (15, 16). Briefly, 1 × 105/ml J774A.1 cells were incubated overnight in wells of cell culture-treated 96-well plates. The following day, 1 × 106 bacteria/ml were opsonized for 60 min in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 40 μg/ml of either poly-IgGs or control poly-IgGNHS, and 100 μl of this (multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 1) was added to each well of the washed macrophage plates. After 30 min of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, cells were washed three times with DMEM alone. Macrophages were then exposed to medium containing 100 μg/ml of polymyxin B for 30 min to kill off bacteria that were not phagocytosed and were present outside the cells. Cells were washed again five times, and wells were immediately lysed twice with water and dilution plated on LB plates. The number of CFU calculated from LB plates was divided by the number of estimated cells plated to give the number of CFU phagocytosed.

Poly-IgG#168, poly-IgG#116, poly-IgG#207, and poly-IgG#219 were used to study antibody-mediated opsonophagocytosis of CR-Kp strains (SBU168, SBU116, SBU207, SBU219, MMC34, MMC36, and MMC38) and of wzi154 CPS-expressing 33576 and the acapsular 33576 Δwzy mutant (13). Phagocytosis assay was additionally carried out with CPS-specific depleted PD IgGs (wzi50- and wzi154-depleted poly-IgGs) and poly-IgG#NHS (negative control). All conditions were performed in triplicates.

Pulmonary infection model in mice.

The pulmonary infection model study was done per a protocol described previously (15). Female C57BL/6 mice (6 to 8 weeks old) were used. CR-Kp strains (MMC36, MMC34, and SBU116; 2 × 108 CFU/ml) were incubated with PD poly-IgGs, CPS-specific depleted PD poly-IgGs, or PBS at 5 mg/ml for 1 h. A 50-μl volume of this inoculum, containing 107 CFU, was injected intratracheally. After 24 h, mice were euthanized, and lungs and spleens were processed for enumeration of bacteria in homogenized tissue and bacterial dissemination analysis.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical tests were performed with GraphPad Prism 6 for Windows. For multigroup comparisons of parametric data (e.g., phagocytosis and serum resistance assay), analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc analysis using Tukey’s, Sidak’s, or Dunnett’s comparison tests was used. For two-group comparisons of parametric data, paired t tests corrected for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Sidak method were performed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Liang Chen and Barry Kreiswirth for gifting us CR-Kp strains 33576 and 33576 Δwzy mutant carbapenem-susceptible ST258 K. pneumoniae strains (13). Additionally, we thank Somanon Bhattacharya for his assistance in editing the manuscript.

We report no financial conflicts of interest.

K.B., M.P.M, E.D.-N., and B.C.F. contributed equally to the ideation and development of the project. K.B. conducted all of the experiments, analyzed the data, and generated all of the manuscript figures. K.B., M.P.M., and B.C.F. contributed equally to writing and editing the manuscript. E.D.-N. contributed to patient plasma and clinical isolates collection, and wzi typing. M.P.M. helped K.B. in conducting animal experiments.

This study was funded using U.S. Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award 5I01 BX003741. B.C.F. is an attending at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs–Northport VA Medical Center, Northport, NY. M.P.M. is funded through F30 AI140611.

The contents of this study do not represent the views of the VA or the U.S. Government.

Contributor Information

Bettina C. Fries, Email: Bettina.Fries@stonybrookmedicine.edu.

David S. Perlin, Hackensack Meridian Health Center for Discovery and Innovation

REFERENCES

- 1.Xu L, Sun X, Ma X. 2017. Systematic review and meta-analysis of mortality of patients infected with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 16:18. doi: 10.1186/s12941-017-0191-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. 2019. WHO publishes global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/WHO-PPL-Short_Summary_25Feb-ET_NM_WHO.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Duin D, Arias CA, Komarow L, Chen L, Hanson BM, Weston G, Cober E, Garner OB, Jacob JT, Satlin MJ, Fries BC, Garcia-Diaz J, Doi Y, Dhar S, Kaye KS, Earley M, Hujer AM, Hujer KM, Domitrovic TN, Shropshire WC, Dinh A, Manca C, Luterbach CL, Wang M, Paterson DL, Banerjee R, Patel R, Evans S, Hill C, Arias R, Chambers HF, Fowler VG, Jr, Kreiswirth BN, Bonomo RA, Multi-Drug Resistant Organism Network Investigators . 2020. Molecular and clinical epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales in the USA (CRACKLE-2): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 20:731–741. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30755-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Follador R, Heinz E, Wyres KL, Ellington MJ, Kowarik M, Holt KE, Thomson NR. 2016. The diversity of Klebsiella pneumoniae surface polysaccharides. Microb Genom 2:e000073. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brisse S, Passet V, Haugaard AB, Babosan A, Kassis-Chikhani N, Struve C, Decre D. 2013. wzi gene sequencing, a rapid method for determination of capsular type for Klebsiella strains. J Clin Microbiol 51:4073–4078. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01924-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deleo FR, Chen L, Porcella SF, Martens CA, Kobayashi SD, Porter AR, Chavda KD, Jacobs MR, Mathema B, Olsen RJ, Bonomo RA, Musser JM, Kreiswirth BN. 2014. Molecular dissection of the evolution of carbapenem-resistant multilocus sequence type 258 Klebsiella pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:4988–4993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321364111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diago-Navarro E, Chen L, Passet V, Burack S, Ulacia-Hernando A, Kodiyanplakkal RP, Levi MH, Brisse S, Kreiswirth BN, Fries BC. 2014. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae exhibit variability in capsular polysaccharide and capsule associated virulence traits. J Infect Dis 210:803–813. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Satlin MJ, Chen L, Patel G, Gomez-Simmonds A, Weston G, Kim AC, Seo SK, Rosenthal ME, Sperber SJ, Jenkins SG, Hamula CL, Uhlemann AC, Levi MH, Fries BC, Tang YW, Juretschko S, Rojtman AD, Hong T, Mathema B, Jacobs MR, Walsh TJ, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2017. Multicenter clinical and molecular epidemiological analysis of bacteremia due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in the CRE epicenter of the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02349-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02349-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conte V, Monaco M, Giani T, D’Ancona F, Moro ML, Arena F, D'Andrea MM, Rossolini GM, Pantosti A, on behalf of the AR-ISS Study Group on Carbapenemase-Producing K. pneumoniae . 2016. Molecular epidemiology of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from invasive infections in Italy: increasing diversity with predominance of the ST512 clade II sublineage. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:3386–3391. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez-Simmonds A, Greenman M, Sullivan SB, Tanner JP, Sowash MG, Whittier S, Uhlemann AC. 2015. Population structure of Klebsiella pneumoniae causing bloodstream infections at a New York City tertiary care hospital: diversification of multidrug-resistant isolates. J Clin Microbiol 53:2060–2067. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03455-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Duin D, Perez F, Rudin SD, Cober E, Hanrahan J, Ziegler J, Webber R, Fox J, Mason P, Richter SS, Cline M, Hall GS, Kaye KS, Jacobs MR, Kalayjian RC, Salata RA, Segre JA, Conlan S, Evans S, Fowler VG, Jr, Bonomo RA. 2014. Surveillance of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: tracking molecular epidemiology and outcomes through a regional network. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:4035–4041. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02636-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeLeo FR, Kobayashi SD, Porter AR, Freedman B, Dorward DW, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN. 2017. Survival of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 258 in human blood. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02533-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02533-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi SD, Porter AR, Dorward DW, Brinkworth AJ, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, DeLeo FR. 2016. Phagocytosis and killing of carbapenem-resistant ST258 Klebsiella pneumoniae by human neutrophils. J Infect Dis 213:1615–1622. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jansen KU, Anderson AS. 2018. The role of vaccines in fighting antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Hum Vaccin Immunother 14:2142–2149. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1476814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diago-Navarro E, Calatayud-Baselga I, Sun D, Khairallah C, Mann I, Ulacia-Hernando A, Sheridan B, Shi M, Fries BC. 2017. Antibody-based immunotherapy to treat and prevent infection with hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin Vaccine Immunol 24:e00456-16. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00456-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diago-Navarro E, Motley MP, Ruiz-Perez G, Yu W, Austin J, Seco BMS, Xiao G, Chikhalya A, Seeberger PH, Fries BC. 2018. Novel, broadly reactive anticapsular antibodies against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae protect from infection. mBio 9:e00091-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00091-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi SD, Porter AR, Freedman B, Pandey R, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, DeLeo FR. 2018. Antibody-mediated killing of carbapenem-resistant ST258 Klebsiella pneumoniae by human neutrophils. mBio 9:e00297-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00297-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Opoku-Temeng C, Kobayashi SD, DeLeo FR. 2019. Klebsiella pneumoniae capsule polysaccharide as a target for therapeutics and vaccines. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 17:1360–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2019.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malachowa N, Kobayashi SD, Porter AR, Freedman B, Hanley PW, Lovaglio J, Saturday GA, Gardner DJ, Scott DP, Griffin A, Cordova K, Long D, Rosenke R, Sturdevant DE, Bruno D, Martens C, Kreiswirth BN, DeLeo FR. 2019. Vaccine protection against multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a nonhuman primate model of severe lower respiratory tract infection. mBio 10:e02994-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02994-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bloom DE, Black S, Salisbury D, Rappuoli R. 2018. Antimicrobial resistance and the role of vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:12868–12871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717157115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banerjee K, Motley M, Diago-Navarro E, Fries B. 2019. 405. Serum antibody responses against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in infected patients. Open Forum Infec Dis 6(Suppl 2):S206. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz360.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rollenske T, Szijarto V, Lukasiewicz J, Guachalla LM, Stojkovic K, Hartl K, Stulik L, Kocher S, Lasitschka F, Al-Saeedi M, Schroder-Braunstein J, von Frankenberg M, Gaebelein G, Hoffmann P, Klein S, Heeg K, Nagy E, Nagy G, Wardemann H. 2018. Cross-specificity of protective human antibodies against Klebsiella pneumoniae LPS O-antigen. Nat Immunol 19:617–624. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calzas C, Lemire P, Auray G, Gerdts V, Gottschalk M, Segura M. 2015. Antibody response specific to the capsular polysaccharide is impaired in Streptococcus suis serotype 2-infected animals. Infect Immun 83:441–453. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02427-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Wen Z, Pan X, Briles DE, He Y, Zhang JR. 2018. Novel immunoprotective proteins of Streptococcus pneumoniae identified by opsonophagocytosis killing screen. Infect Immun 86:e00423-18. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00423-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feldman MF, Mayer Bridwell AE, Scott NE, Vinogradov E, McKee SR, Chavez SM, Twentyman J, Stallings CL, Rosen DA, Harding CM. 2019. A promising bioconjugate vaccine against hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116:18655–18663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1907833116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell WN, Hendrix E, Cryz S, Jr, Cross AS. 1996. Immunogenicity of a 24-valent Klebsiella capsular polysaccharide vaccine and an eight-valent Pseudomonas O-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine administered to victims of acute trauma. Clin Infect Dis 23:179–181. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cryz SJ, Jr, Furer E, Germanier R. 1986. Immunization against fatal experimental Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumonia. Infect Immun 54:403–407. doi: 10.1128/IAI.54.2.403-407.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edelman K. 1994. Multiple pyogenic liver abscesses communicating with the biliary tree: treatment by endoscopic stenting and stone removal. Am J Gastroenterol 89:2070–2072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim D, Park BY, Choi MH, Yoon EJ, Lee H, Lee KJ, Park YS, Shin JH, Uh Y, Shin KS, Shin JH, Kim YA, Jeong SH. 2019. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence factors of Klebsiella pneumoniae affecting 30 day mortality in patients with bloodstream infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:190–199. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kubler-Kielb J, Vinogradov E, Ng WI, Maczynska B, Junka A, Bartoszewicz M, Zelazny A, Bennett J, Schneerson R. 2013. The capsular polysaccharide and lipopolysaccharide structures of two carbapenem resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae outbreak isolates. Carbohydr Res 369:6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lang AB, Bruderer U, Senyk G, Pitt TL, Larrick JW, Cryz SJ, Jr.. 1991. Human monoclonal antibodies specific for capsular polysaccharides of Klebsiella recognize clusters of multiple serotypes. J Immunol 146:3160–3164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith K, Muther JJ, Duke AL, McKee E, Zheng NY, Wilson PC, James JA. 2013. Fully human monoclonal antibodies from antibody secreting cells after vaccination with Pneumovax®23 are serotype specific and facilitate opsonophagocytosis. Immunobiology 218:745–754. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.08.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seeberger PH, Pereira CL, Khan N, Xiao G, Diago-Navarro E, Reppe K, Opitz B, Fries BC, Witzenrath M. 2017. A semi-synthetic glycoconjugate vaccine candidate for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 56:13973–13978. doi: 10.1002/anie.201700964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yokota S, Amano K, Hayashi S, Kubota T, Fujii N, Yokochi T. 1998. Human antibody response to Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide: presence of an immunodominant epitope in the polysaccharide chain of lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun 66:3006–3011. doi: 10.1128/IAI.66.6.3006-3011.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen T, Blanc C, Liu Y, Ishida E, Singer S, Xu J, Joe M, Jenny-Avital ER, Chan J, Lowary TL, Achkar JM. 2020. Capsular glycan recognition provides antibody-mediated immunity against tuberculosis. J Clin Invest 130:1808–1822. doi: 10.1172/JCI128459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clements A, Jenney AW, Farn JL, Brown LE, Deliyannis G, Hartland EL, Pearse MJ, Maloney MB, Wesselingh SL, Wijburg OL, Strugnell RA. 2008. Targeting subcapsular antigens for prevention of Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. Vaccine 26:5649–5653. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hegerle N, Choi M, Sinclair J, Amin MN, Ollivault-Shiflett M, Curtis B, Laufer RS, Shridhar S, Brammer J, Toapanta FR, Holder IA, Pasetti MF, Lees A, Tennant SM, Cross AS, Simon R. 2018. Development of a broad spectrum glycoconjugate vaccine to prevent wound and disseminated infections with Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One 13:e0203143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tzouvelekis LS, Miriagou V, Kotsakis SD, Spyridopoulou K, Athanasiou E, Karagouni E, Tzelepi E, Daikos GL. 2013. KPC-producing, multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 258 as a typical opportunistic pathogen. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5144–5146. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01052-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Motley MP, Diago-Navarro E, Banerjee K, Inzerillo S, Fries BC. 2020. The role of IgG subclass in antibody-mediated protection against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. mBio 11:e02059-20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02059-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Duin D, Paterson DL. 2016. Multidrug-resistant bacteria in the community: trends and lessons learned. Infect Dis Clin North Am 30:377–390. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin RM, Bachman MA. 2018. Colonization, infection, and the accessory genome of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 8:4. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hicks LA, Harrison LH, Flannery B, Hadler JL, Schaffner W, Craig AS, Jackson D, Thomas A, Beall B, Lynfield R, Reingold A, Farley MM, Whitney CG, Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Program of the Emerging Infections Program Network . 2007. Incidence of pneumococcal disease due to non-pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) serotypes in the United States during the era of widespread PCV7 vaccination, 1998–2004. J Infect Dis 196:1346–1354. doi: 10.1086/521626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singleton RJ, Hennessy TW, Bulkow LR, Hammitt LL, Zulz T, Hurlburt DA, Butler JC, Rudolph K, Parkinson A. 2007. Invasive pneumococcal disease caused by nonvaccine serotypes among Alaska Native children with high levels of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine coverage. JAMA 297:1784–1792. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.16.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Redwan EM. 2012. Simple, sensitive, and quick protocol to detect less than 1 ng of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Prep Biochem Biotechnol 42:171–182. doi: 10.1080/10826068.2011.586081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brito LA, Singh M. 2011. Acceptable levels of endotoxin in vaccine formulations during preclinical research. J Pharm Sci 100:34–37. doi: 10.1002/jps.22267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu MF, Yang CY, Lin TL, Wang JT, Yang FL, Wu SH, Hu BS, Chou TY, Tsai MD, Lin CH, Hsieh SL. 2009. Humoral immunity against capsule polysaccharide protects the host from magA+ Klebsiella pneumoniae-induced lethal disease by evading Toll-like receptor 4 signaling. Infect Immun 77:615–621. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00931-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diaz Romero J, Outschoorn I. 1993. Selective biotinylation of Neisseria meningitidis group B capsular polysaccharide and application in an improved ELISA for the detection of specific antibodies. J Immunol Methods 160:35–47. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90006-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Antibody responses in “infected” versus “colonized” carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CR-Kp) patients to capsular polysaccharides (CPS) isolated from CR-Kp strains. Humoral responses to CPS were independent of the patient’s clinical status. Optical density (OD) ratio = OD CPS/OD bovine serum albumin (BSA). The positive cutoff is set at y = 2 (red line); positive sera had values of ≥2, and negative sera had values of <2; N = 33; each dot on the scatter plot indicates an individual CR-Kp patient’s OD ratio, and the deviations in OD ratios are shown as standard deviations (SD). Download FIG S1, TIF file, 1.7 MB (1.7MB, tif) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Antibody responses to capsular polysaccharides (CPS) and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) isolated from carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae. IgM response (A) and IgA response (B) to wzi29, wzi154, and wzi50 CPS were compared in CR-Kp patients. OD ratio = OD CPS/OD BSA. The positive cutoff is set at y = 2 (red line); positive sera had values of ≥2, and negative serum had values of <2; each dot on the scatter plot indicates an individual CR-Kp patient’s OD ratio, and the deviations in OD ratios are shown as SD. Download FIG S2, TIF file, 1.4 MB (1.4MB, tif) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

IgG subclass (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4) responses to capsular polysaccharides (CPS) and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae-infected patients (N = 33). O.D. Ratio = (O.D. CPS/O.D. BSA). The positive serum had the value ≥2 and negative serum is <2; bars depict means and SD from three independent experiments, with wells performed in triplicate. Download FIG S3, TIF file, 0.9 MB (959.8KB, tif) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

PD-IgGs isolated from patient 168 (wzi50) induced opsonophagocytosis of patient-matched SBU168 strain. Bars depict means and SD from three independent experiments, with wells performed in triplicate. poly-IgG#NHS and PBS serve as the negative controls for the assay. Phagocytosed bacteria within macrophages were counted by plating lysed macrophages (log CFUs phagocytosed) on LB agar plates. Overall differences between treatment groups were determined to be significant by repeated-measures two-way ANOVA using Tukey's post-hoc test displayed in-graph. For all in-graph statistics, P values displayed in blue are comparisons to the PBS control. ** signifies P < 0.01. Download FIG S4, TIF file, 0.9 MB (937KB, tif) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Endotoxin levels in isolated CPS samples. Positive-control LPS (Sigma Aldrich) and isolated samples were analyzed by the sodium deoxycholate (DOC)-PAGE method. Aliquots (200 ng and 100 ng) of each sample were loaded on the gel, and endotoxin (LPS) contamination was visualized by silver nitrate staining. Standard curve of limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) assay and amount of endotoxin levels present in 200 ng of CPS samples purified from MMC34, MMC36, and MMC38 strains. Download FIG S5, PDF file, 0.1 MB (97.1KB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.