Abstract

BACKGROUND

Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder. It disrupts the patient’s life and work, increases the risk of various health issues, and often requires long-term intervention. The financial burden and inconvenience of treatments discourage patients from complying with them, leading to chronic insomnia.

AIM

To investigate the long-term home-practice effects of mindful breathing combined with a sleep-inducing exercise as adjunctive insomnia therapy.

METHODS

A quasi-experimental design was used in the present work, in which the patients with insomnia were included and grouped based on hospital admission: 40 patients admitted between January and April 2020 were assigned to the control group, and 40 patients admitted between May and August 2020 were assigned to the treatment group. The control group received routine pharmacological and physical therapies, while the treatment group received instruction in mindful breathing and a sleep-inducing exercise in addition to the routine therapies. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale, and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) were utilized to assess sleep-quality improvement in the patient groups before the intervention and at 1 wk, 1 mo, and 3 mo postintervention.

RESULTS

The PSQI, GAD-7, and ISI scores before the intervention and at 1 wk postintervention were not significantly different between the groups. However, compared with the control group, the treatment group exhibited significant improvements in sleep quality, daytime functioning, negative emotions, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, anxiety level, and insomnia severity at 1 and 3 mo postintervention (P < 0.05). The results showed that mindful breathing combined with the sleep-inducing exercise significantly improved the long-term effectiveness of insomnia treatment. At 3 mo, the PSQI scores for the treatment vs the control group were as follows: Sleep quality 0.98 ± 0.48 vs 1.60 ± 0.63, sleep latency 1.98 ± 0.53 vs 2.80 ± 0.41, sleep duration 1.53 ± 0.60 vs 2.70 ± 0.56, sleep efficiency 2.35 ± 0.58 vs 1.63 ± 0.49, sleep disturbance 1.68 ± 0.53 vs 2.35 ± 0.53, hypnotic medication 0.53 ± 0.64 vs 0.93 ± 0.80, and daytime dysfunction 1.43 ± 0.50 vs 2.48 ± 0.51 (all P < 0.05). The GAD-7 scores were 2.75 ± 1.50 vs 7.15 ± 2.28, and the ISI scores were 8.68 ± 2.26 vs 3.38 ± 1.76 for the treatment vs the control group, respectively (all P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION

These simple, cost-effective, and easy-to-implement practices used in clinical or home settings could have profound significance for long-term insomnia treatment and merit wide adoption in clinical practice.

Keywords: Mindful breathing, Sleep-inducing exercise, Insomnia, Treatment effectiveness, Psychotherapy

Core Tip: The adjunctive therapies of mindful breathing and a sleep-inducing exercise could improve the outcome of patients with insomnia by providing a simple, cost-effective, and easy-to-implement method that can be used both clinically and long-term in a home setting. The findings indicated that compared with the control group, the group that performed mindful breathing and a sleep-inducing exercise in conjunction with routine pharmacological and physical therapies exhibited significant improvements in sleep quality, daytime functioning, negative emotions, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, anxiety level, and insomnia severity at 1 and 3 mo after the intervention (P < 0.05).

INTRODUCTION

Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder[1]. An epidemiological study revealed that 45.4% of survey respondents in China experienced varying degrees of insomnia in the previous month. Chronic insomnia disrupts an individual’s life and work and increases the risk of various health issues. It is often accompanied by symptoms such as daytime sleepiness, fatigue, dizziness, and attention problems[2] that reduce patients’ work efficiency and alertness, increasing the probability of car, home, or work accidents[3] and often leading to substantial damage. Moreover, both primary and secondary insomnia pose a threat to patients’ health. Insomnia cases are increasing annually owing to the accelerating pace of life[4], and as the public becomes more aware of its prevalence and dangers, its rational treatment is being increasingly recognized. In recent years, insomnia treatment approaches have primarily included pharmacological and nonpharmacological (psychological, cognitive-behavioral) therapies[5-7]. Pakpour’s group proposed a cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) app-based intervention and demonstrated that patients with insomnia showed improved sleep hygiene behaviors, enhanced sleep quality, and less insomnia severity after receiving CBT-I[8,9]. Insomnia often requires long-term intervention, and thus, the financial burden and inconvenience of both approaches discourage patients from complying, leading to chronic insomnia. Mindfulness is a well-researched psychological practice and can be an effective nonpharmacological intervention. For example, the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions enables the reduction of anxiety and depression[10,11]. More importantly, its stability and effectiveness have also been demonstrated in many studies on insomnia[12]. In this study, we employed a quasi-experimental design to investigate the effects of mindful breathing combined with a sleep-inducing exercise as adjunctive therapies for patients with insomnia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Baseline characteristics

Patients with insomnia admitted to the Sleep Medical Center of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University between January and August 2020 were included in the study. The patients with insomnia were grouped based on the time of admission: 40 patients admitted between January and April 2020 were assigned to the control group, which was composed of 13 males and 27 females with a mean age of 51.3 ± 10.2 years, and 40 patients admitted between May and August 2020 were assigned to the treatment group, which consisted of 15 males and 25 females, with a mean age of 52.4 ± 11.5 years. The groups were comparable in baseline characteristics with no significant differences, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics of insomnia patients in the treatment group and control group

|

Characteristic

|

Treatment, n = 40

|

Control, n = 40

|

| Age in yr, mean ± SD | 52.4 ± 11.5 | 51.3 ± 10.2 |

| Male sex, n/total n (%) | 13/40 (32.5) | 15/40 (37.5) |

| Married, n/total n (%) | 37/40 (92.5) | 38/40 (95) |

| University graduate, n/total n (%) | 32/40 (80) | 34/40 (85) |

SD: Standard deviation.

Inclusion criteria

All the included patients met the criteria stipulated in the guidelines for diagnosing and treating insomnia disorders in China[13]. All patients signed an informed consent form and were willing to be followed-up for 3 mo after discharge.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were patients with (1) communication disorders who could not receive both interventions; (2) severe cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases and other serious comorbidities that rendered them unable to perform self-care; (3) unresolved psychological conflicts due to major life events; (4) diseases of the head, neck, limbs, or joints; and (5) the lack of ability to perform the required mindful breathing and sleep-inducing exercise.

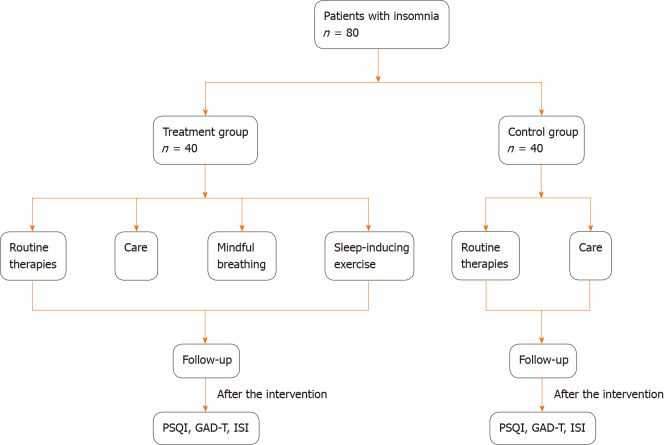

Specific implementation methods

The flowchart of the study design is shown in Figure 1. The control group received routine therapies and care, while the treatment group performed mindful breathing and a sleep-inducing exercise in addition to the routine therapies and care. Mindful breathing is a psychological intervention based on the principle of maintaining a constant attitude of nonjudgment, effortlessness, calmness, self-care, self-trust, and acceptance while observing the breath[14]. The guided mindful breathing practice was performed daily, overseen by a nurse who played an audio recording of the instructions in the treatment-group patient’s ward for 30 min prior to bedtime. During the intervention, the patients adopted a comfortable position, either sitting or lying down. Throughout the audio guidance, the patients were prompted to become aware of their breathing. They were instructed to keep their minds free from distractions and focus on their breathing sounds, rhythm, movements, and patterns. They concentrated on sensing all aspects of their breathing, focusing their attention on the entire breathing process, including the inward and outward motion of the abdomen caused by breathing. The sleep-inducing exercise was developed by Professor Sun Wei of the Peking University Sixth Hospital, Beijing, China, based on Daoist health-preserving foundation exercises (Zhu Ji Gong) with modifications. It involves twisting the trunk (the region of the body below the head and above the waist) to stimulate the conception and governing vessels. During the exercise, the patient’s mind is focused on rotating his or her trunk, thus reducing distracting thoughts and allowing the mind to attain “a state of inner stillness,” leading to relaxation and concentration.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study design. PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index.

The exercise was implemented and followed-up by a team comprising a psychotherapist and six polysomnographic nurses. The psychotherapist was responsible for the formulation, final decision-making aspects of the study, and the patients’ psychological counseling before and after the intervention. This procedure was followed to ensure that the patients fully understood the purpose and significance of the interventions, thereby increasing their commitment to cooperate and perform them earnestly. The six professionally trained nurses were responsible for conducting the patients’ daily practice. One of the nurses was responsible for following up with patients after they were discharged. During the hospitalization period, the patients were guided daily by the nurses to perform the sleep-inducing exercise once in the afternoon and mindful breathing for 30 min before going to bed. A “WeChat” group was set up to follow-up with the patients after their discharge. They were reminded daily to practice the two interventions at the specified time as instructed and reported from their homes daily via “WeChat.” The follow-up period ended when the patients had practiced for 3 mo. Both groups had complete follow-up information.

Assessment

Follow-up interviews were performed via telephone at 1 wk, 1 mo, and 3 mo after the intervention, and the information collected was used to calculate the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale, and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) values. The overall sleep quality of the patient groups was subsequently assessed based on the data collected. The PSQI consists of 18 items across seven components, and each component is given a score of 0-3. The PSQI global score is calculated from the sum of all components' scores and ranges from 0 to 21, where a higher score indicates poorer sleep quality, and it assesses components such as sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, and daytime dysfunction. The GAD-7 scale classifies anxiety into four categories — none, mild, moderate, and severe — based on the total score; higher total scores indicate increasingly severe anxiety. The ISI comprises seven questions, and the results are classified as “no clinically significant insomnia,” “subthreshold insomnia,” “clinical insomnia (moderate severity),” and “clinical insomnia (severe).” A higher total score indicates more severe insomnia.

Statistical analyses

The data analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0 statistical software (Chicago, IL, United States). The numeric data were expressed as χ2 ± S, and t-tests were performed. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Patient group PSQI score comparison before and after intervention

Both patient groups were similarly treated once with hypnotic medication within 1 wk of admission. The PSQI scores before the intervention and at 1 wk after the intervention were not significantly different between the two groups. After 1 mo of intervention, the PSQI score for the hypnotic medication was not significantly different between the groups; however, the other components exhibited significant differences (P < 0.05). After 3 mo of intervention, the PSQI scores for sleep quality, latency, duration, and efficiency to daytime dysfunction were significantly different between the groups (P < 0.05) (Tables 2-5).

Table 2.

Patient group Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index score comparison before intervention

|

Group

|

Sleep quality

|

Sleep latency

|

Sleep duration

|

Sleep efficiency

|

Sleep disturbance

|

Hypnotic medication

|

Daytime dysfunction

|

| Treatment group, n = 40 | 2.83 ± 0.39 | 2.93 ± 0.42 | 2.93 ± 0.27 | 2.80 ± 0.41 | 2.70 ± 0.46 | 1.08 ± 0.83 | 2.53 ± 0.64 |

| Control group, n = 40 | 2.70 ± 0.46 | 2.90 ± 0.30 | 2.93 ± 0.27 | 2.75 ± 0.44 | 2.73 ± 0.45 | 1.23 ± 1.00 | 2.63 ± 0.54 |

| t | -1.311 | -0.391 | 0.000 | -0.530 | 0.244 | 0.731 | 0.755 |

| P value | 0.194 | 0.697 | 1.000 | 0.598 | 0.808 | 0.467 | 0.452 |

Table 5.

Patient group Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index score comparison 3 mo after intervention

|

Group

|

Sleep quality

|

Sleep latency

|

Sleep duration

|

Sleep efficiency

|

Sleep disturbance

|

Hypnotic medication use

|

Daytime dysfunction

|

| Treatment group, n = 40 | 0.98 ± 0.48 | 1.98 ± 0.53 | 1.53 ± 0.60 | 2.35 ± 0.58 | 1.68 ± 0.53 | 0.53 ± 0.64 | 1.43 ± 0.50 |

| Control group, n = 40 | 1.60 ± 0.63 | 2.80 ± 0.41 | 2.70 ± 0.56 | 1.63 ± 0.49 | 2.35 ± 0.53 | 0.93 ± 0.80 | 2.48 ± 0.51 |

| t | 4.980 | 7.817 | 9.037 | -6.040 | 5.700 | 2.475 | 9.332 |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Table 3.

Patient group Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index score comparison 1 wk after intervention

|

Group

|

Sleep quality

|

Sleep latency

|

Sleep duration

|

Sleep efficiency

|

Sleep disturbance

|

Daytime dysfunction

|

| Treatment group, n = 40 | 0.98 ± 0.36 | 2.55 ± 0.50 | 1.60 ± 0.63 | 1.75 ± 0.54 | 1.70 ± 0.56 | 1.63 ± 0.54 |

| Control group, n = 40 | 1.05 ± 0.50 | 2.68 ± 0.47 | 1.60 ± 0.59 | 1.83 ± 0.45 | 1.70 ± 0.52 | 1.70 ± 0.46 |

| t | 0.769 | 0.391 | 0.000 | 0.675 | 0.000 | 0.666 |

| P value | 0.445 | 0.697 | 1.000 | 0.502 | 1.000 | 0.507 |

Table 4.

Patient group Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index score comparison 1 mo after intervention

|

Group

|

Sleep quality

|

Sleep latency

|

Sleep duration

|

Sleep efficiency

|

Sleep disturbance

|

Hypnotic medication use

|

Daytime dysfunction

|

| Treatment group, n = 40 | 0.95 ± 0.32 | 2.20 ± 0.41 | 1.48 ± 0.64 | 2.25 ± 0.59 | 1.50 ± 0.56 | 2.70 ± 0.79 | 1.55 ± 0.60 |

| Control group, n = 40 | 1.28 ± 0.51 | 2.73 ± 0.45 | 2.40 ± 0.63 | 1.68 ± 0.47 | 2.39 ± 0.49 | 2.60 ± 0.84 | 2.38 ± 0.54 |

| t | 3.446 | 5.469 | 6.502 | -4.812 | 7.475 | -0.548 | 6.481 |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Patient group GAD-7 score comparison

The GAD-7 scores before the intervention and at 1 wk after the intervention were not significantly different between the groups. However, at 1 and 3 mo after the intervention, the differences were significant (P < 0.05) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Patient group Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale total score comparison before and after interventions

|

Group

|

Before intervention

|

After intervention

|

||

|

1 wk

|

1 mo

|

3 mo

|

||

| Treatment group, n = 40 | 12.20 ± 4.07 | 5.60 ± 1.87 | 3.38 ± 1.68 | 2.75 ± 1.50 |

| Control group, n = 40 | 11.18 ± 1.97 | 4.98 ± 1.75 | 6.05 ± 1.80 | 7.15 ± 2.28 |

| t | -1.431 | -1.547 | 6.888 | 10.195 |

| P value | 0.156 | 0.126 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Patient group ISI score comparison

The ISI scores before and 1 wk after the intervention were not significantly different between the groups. However, at 1 and 3 mo after the intervention, the differences were significant (P < 0.05) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Patient group Insomnia Severity Index score comparison before and after interventions

|

Group

|

Before intervention

|

After intervention

|

||

|

1 wk

|

1 mo

|

3 mo

|

||

| Treatment group, n = 40 | 22.13 ± 3.30 | 10.63 ± 1.96 | 5.75 ± 1.28 | 8.68 ± 2.26 |

| Control group, n = 40 | 21.38 ± 2.88 | 11.95 ± 1.05 | 7.40 ± 2.45 | 3.38 ± 1.76 |

| t | -1.083 | -0.974 | 3.781 | -11.699 |

| P value | 0.282 | 0.333 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

DISCUSSION

Mindful breathing and sleep-inducing exercises are economical, long-term adjunctive therapies that patients can practice after leaving the hospital. The current insomnia treatments include psychological, pharmacological, and physical therapies as well as treatment with traditional Chinese medicine. The psychological therapy procedures primarily include sleep hygiene education and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Although cognitive-behavioral therapy is considered the preferred treatment option in the field[15], it requires equipment and technical support, and individuals who can benefit from online education are limited. The cost of the therapy is also an obstacle for certain groups[16,17]. Clinical observations have proven[18,19] the short-term efficacy of pharmacological treatments for insomnia; however, their long-term use can be associated with potential risks, such as adverse drug reactions and addiction. Physical therapy includes transcranial magnetic stimulation, auditory stimulation, phototherapy, and biofeedback therapy; however, data from large-sample studies to support their efficacies are lacking. In addition, these procedures require patients to be in the hospital; thus, the inconvenience and financial requirements are limitations for patients considering therapy[20]. The use of traditional Chinese medicine to treat insomnia has a long-standing history; however, its current use is limited by the individualized approach of modern medicine, and its effectiveness cannot be demonstrated by using modern evidence-based methods. Therefore, the development of adjunctive therapy and care approaches is needed in clinical practice to overcome obstacles to the nonpharmacological treatment of insomnia[21]. The emergence of mindful breathing and sleep-inducing exercises could address this need.

The principles of mindful breathing and sleep-inducing exercises focus on enhancing body awareness and inducing changes in emotions and self-concept. The principle of mindful breathing involves attention to breathing, body regulation, body awareness, and emotion regulation and leads to self-concept changes. By being aware of the present moment, one’s perception of sleep can be changed, thereby allowing the search for solutions with a peaceful mind[22]. Hofmann and Gómez[23] demonstrated the positive outcomes of mindful breathing on the anxiety and depression experienced by patients with insomnia. The present study incorporated a sleep-inducing exercise to achieve better sleep quality, sleep efficiency, and other long-term clinical effects. Sleep-inducing exercises are simple to perform, effective, economical, and practical; they can clear the meridians, modulate body functions, calm the mind, and improve concentration. A considerable amount of exercise can be performed by twisting various parts of the body, promoting blood circulation, and simultaneously fulfilling the daily activity requirement, thereby enhancing physical fitness[24]. Patients with insomnia often experience negative emotions, such as depression and anxiety, which can be relieved by an appropriate amount of daytime exercise.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we found that the combination of mindful breathing and a sleep-inducing exercise are useful as adjunctive therapies in the long-term treatment of patients with insomnia. The PSQI, GAD-7, and ISI are internationally recognized instruments for assessing sleep quality, anxiety status, and insomnia severity, respectively[25]. Our results showed that 1 wk of intervention with routine pharmacological and physical intervention therapies administered to patients with insomnia during the hospitalization period did not significantly affect the treatment group. Thus, the effectiveness of the two practices was not demonstrated within that short time frame. However, compared with those in the control group, patients in the treatment group exhibited significant improvements in sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep efficiency, sleep duration, daytime functioning, anxiety level, and insomnia severity at 1 and 3 mo after the intervention. The enhancement of sleep quality can be attributed to the mindful breathing and sleep-inducing exercise during home practice. Moreover, hypnotic medication efficacy improved after 3 mo of intervention. The results indicated that mindful breathing combined with the sleep-inducing exercise significantly improved the long-term effectiveness of insomnia treatment. Patients can continue to perform both practices as adjunctive therapies autonomously after being discharged from the hospital. These practices improve their ability to focus on themselves by acquiring and mastering a self-care option to treat their insomnia, in addition to reducing the use of medical resources. Thus, these practices merit long-term commitment and wide adoption in clinical settings.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder. It disrupts the patient’s life and work, increases the risk of various health issues, and often requires long-term intervention. The financial burden and inconvenience discourage patients from complying with the treatments, leading to chronic insomnia.

Research motivation

Mindfulness is a well-researched psychological practice and can be an effective nonpharmacological intervention, and its stability and effectiveness have been demonstrated in many studies about the insomnia. Herein, we employed a use a quasi-experimental design to investigate the effects of mindful breathing combined with a sleep-inducing exercise as adjunctive therapies for patients with insomnia.

Research objectives

To investigate the effects of mindful breathing combined with sleep-inducing exercises in patients with insomnia.

Research methods

In this work, the control group received routine therapies and care, while the treatment group was intervened with mindful breathing and a sleep-inducing exercise in addition to the routine therapies and care. The guided mindful breathing practice was performed daily, overseen by a nurse who played an audio recording of the guiding instructions in the treatment-group patient’s ward for 30 min prior to bedtime. Follow-up interviews were performed via telephone at 1 wk, 1 mo, and 3 mo after the intervention, and the information collected was used to complete the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale, and Insomnia Severity Index.

Research results

Our results showed that 1 wk of intervention with the routine pharmacological and physical intervention therapies administered to the patients with insomnia during the hospitalization period did not significantly affect the treatment group. Thus, the effectiveness of the two practices was not demonstrated within that short time-frame. However, compared with the control group, patients in the treatment group exhibited significant improvements in sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep efficiency, sleep duration, daytime functioning, anxiety level, and insomnia severity at 1 and 3 mo of the intervention.

Research conclusions

We found that the combination of mindful breathing and a sleep-inducing exercise are useful as adjunctive therapies in the long-term treatment of patients with insomnia.

Research perspectives

The future research aims at how to enhance the effect of mindful breathing and a sleep-inducing exercise on the treatment of insomnia.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University (approval No 2019PS582K).

Clinical trial registration statement: The study is registered at Chinese Clinical Trial Registry. The registration identification number is: ChiCTR2100049927 and URL for the registry is: https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.aspx?proj=131839.

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: No relevant conflicts of interest.

CONSORT 2010 statement: The authors have read the CONSORT 2010 statement, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CONSORT 2010 statement.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: April 21, 2021

First decision: June 24, 2021

Article in press: August 23, 2021

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lin CY S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li X

Contributor Information

Hui Su, Sleep Medicine Center, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110004, Liaoning Province, China.

Li Xiao, Sleep Medicine Center, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110004, Liaoning Province, China.

Yue Ren, Sleep Medicine Center, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110004, Liaoning Province, China.

Hui Xie, Sleep Medicine Center, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110004, Liaoning Province, China.

Xiang-Hong Sun, Sleep Medicine Center, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110004, Liaoning Province, China. 750019113@qq.com.

Data sharing statement

Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author at sunxh@sj-hospital.org.

References

- 1.Merrigan JM, Buysse DJ, Bird JC, Livingston EH. JAMA patient page. Insomnia. JAMA. 2013;309:733. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung KF, Yeung WF, Ho FY, Yung KP, Yu YM, Kwok CW. Cross-cultural and comparative epidemiology of insomnia: the Diagnostic and statistical manual (DSM), International classification of diseases (ICD) and International classification of sleep disorders (ICSD) Sleep Med. 2015;16:477–482. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Léger D, Bayon V, Ohayon MM, Philip P, Ement P, Metlaine A, Chennaoui M, Faraut B. Insomnia and accidents: cross-sectional study (EQUINOX) on sleep-related home, work and car accidents in 5293 subjects with insomnia from 10 countries. J Sleep Res. 2014;23:143–152. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jha MK, Minhajuddin A, South C, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH. Worsening Anxiety, Irritability, Insomnia, or Panic Predicts Poorer Antidepressant Treatment Outcomes: Clinical Utility and Validation of the Concise Associated Symptom Tracking (CAST) Scale. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;21:325–332. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyx097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, Neubauer DN, Heald JL. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:307–349. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnedt JT, Cuddihy L, Swanson LM, Pickett S, Aikens J, Chervin RD. Randomized controlled trial of telephone-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia. Sleep. 2013;36:353–362. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pillai V, Roth T, Roehrs T, Moss K, Peterson EL, Drake CL. Effectiveness of Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists in the Treatment of Insomnia: An Examination of Response and Remission Rates. Sleep. 2017;40 doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajabi Majd N, Broström A, Ulander M, Lin CY, Griffiths MD, Imani V, Ahorsu DK, Ohayon MM, Pakpour AH. Efficacy of a Theory-Based Cognitive Behavioral Technique App-Based Intervention for Patients With Insomnia: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e15841. doi: 10.2196/15841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin CY, Strong C, Scott AJ, Broström A, Pakpour AH, Webb TL. A cluster randomized controlled trial of a theory-based sleep hygiene intervention for adolescents. Sleep. 2018;41 doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanck P, Perleth S, Heidenreich T, Kröger P, Ditzen B, Bents H, Mander J. Effects of mindfulness exercises as stand-alone intervention on symptoms of anxiety and depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2018;102:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bamber MD, Morpeth E. Effects of Mindfulness Meditation on College Student Anxiety: a Meta-Analysis. Mindfulness. 2019;10:203–214. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim HG. Effects and mechanisms of a mindfulness-based intervention on insomnia. Yeungnam Univ J Med. 2021 doi: 10.12701/yujm.2020.00850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sleep Disorders Group of Neurology Branch of Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Insomnia in Chinese Adults. Zhonghua Shengjingke Zazhi . 2012;7 [Google Scholar]

- 14.McConville J, McAleer R, Hahne A. Mindfulness Training for Health Profession Students-The Effect of Mindfulness Training on Psychological Well-Being, Learning and Clinical Performance of Health Professional Students: A Systematic Review of Randomized and Non-randomized Controlled Trials. Explore (NY) 2017;13:26–45. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaczkurkin AN, Foa EB. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: an update on the empirical evidence. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17:337–346. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.3/akaczkurkin. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martires J, Zeidler M. The value of mindfulness meditation in the treatment of insomnia. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2015;21:547–552. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher A, Bellon M, Lawn S, Lennon S, Sohlberg M. Family-directed approach to brain injury (FAB) model: a preliminary framework to guide family-directed intervention for individuals with brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41:854–860. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1407966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu R, Bao J, Zhang C, Deng J, Long C. Comparison of sleep condition and sleep-related psychological activity after cognitive-behavior and pharmacological therapy for chronic insomnia. Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75:220–228. doi: 10.1159/000092892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kay-Stacey M, Attarian H. Advances in the management of chronic insomnia. BMJ. 2016;354:i2123. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han F, Tang XD, Zhang B. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia in China. Natl Med J China. 2017;97:1844–1856. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin R, Wang X, Lv Y, Xu G, Yang C, Guo Y, Li X. The efficacy and safety of auricular point combined with moxibustion for insomnia: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e22107. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000022107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang Y, Kang X, Feng X, Zhao D, Song D, Li P. Conditional effects of mindfulness on sleep quality among clinical nurses: the moderating roles of extraversion and neuroticism. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24:481–492. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2018.1492731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofmann SG, Gómez AF. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Anxiety and Depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40:739–749. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu F, Shen C, Yao L, Li Z. Acupoint Massage for Managing Cognitive Alterations in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2018;24:532–540. doi: 10.1089/acm.2017.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scarpa M, Pinto E, Saadeh LM, Parotto M, Da Roit A, Pizzolato E, Alfieri R, Cagol M, Saraceni E, Baratto F, Castoro C. Sleep disturbances and quality of life in postoperative management after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:156. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author at sunxh@sj-hospital.org.