Abstract

The integrity of lysosomes is of vital importance to survival of tumor cells. We demonstrated that LW-218, a synthetic flavonoid, induced rapid lysosomal enlargement accompanied with lysosomal membrane permeabilization in hematological malignancy. LW-218-induced lysosomal damage and lysosome-dependent cell death were mediated by cathepsin D, as the lysosomal damage and cell apoptosis could be suppressed by depletion of cathepsin D or lysosome alkalization agents, which can alter the activity of cathepsins. Lysophagy, was initiated for cell self-rescue after LW-218 treatment and correlated with calcium release and nuclei translocation of transcription factor EB. LW-218 treatment enhanced the expression of autophagy-related genes which could be inhibited by intracellular calcium chelator. Sustained exposure to LW-218 exhausted the lysosomal capacity so as to repress the normal autophagy. LW-218-induced enlargement and damage of lysosomes were triggered by abnormal cholesterol deposition on lysosome membrane which caused by interaction between LW-218 and NPC intracellular cholesterol transporter 1. Moreover, LW-218 inhibited the leukemia cell growth in vivo. Thus, the necessary impact of integral lysosomal function in cell rescue and death were illustrated.

Keywords: LW-218, Lysosomal damage, Lysophagy, Lysosomal membrane permeabilization, Lysosome-dependent cell death, Cholesterol, Cathepsin D, Hematological malignancies

Abbreviations: AO, acridine orange; ATG, autophagy related; BAF A1, bafilomycin A1; BID, BH3-interacting domain death agonist; CaN, calcineurin; CCK8, Cell Counting Kit; CsA, cyclosporine A; CTSB, cathepsin B; CTSD, cathepsin D; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride; DCFH-DA, 2,7-dichlorodi-hydrofluorescein diacetate; Dex, dexamethasone; EGTA, ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid; FBS, fetal bovine serum; K48, lysine 48; K63, lysine 63; LAMPs, lysosomal-associated membrane proteins; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; LCD, lysosome-dependent cell death; LMP, lysosome membrane permeabilization; NH4Cl, ammonium chloride; NPC, Niemann-Pick type disease C; NPC1, NPC intracellular cholesterol transporter 1; OD, optical density; P62/SQSTM1, sequestosome 1; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; RAB7A, RAS-related protein RAB-7a; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RT-qPCR, real time quantitative PCR; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; TFEB, transcription factor EB; TRPML1, transient receptor potential mucolipin 1

Graphical abstract

LW-218-induced cholesterol accumulation on lysosomes via NPC1 binding can elicit lysosomal damage followed by lysophagy and lysosome-dependent cell death in hematological malignancies cells.

1. Introduction

Lysosomes are ubiquitous organelles that constitute the primary degradative compartments of the cell. They receive their substrates through endocytosis, phagocytosis or autophagy. It is recognized that lysosomes play an important role in cell death and the integrity of lysosomes is of vital importance to survival of cells1, 2, 3. Tumor cells rely more on hyperactive lysosomal function to proliferate, metabolize, and adapt to stressful environments, as tumor progression is associated with apparent changes in lysosomal volume, composition and cellular distribution3,4. Lysosomes have become potent targets for cancer therapy due to the devastating effects of lysosomal dysfunction on tumor cells4,5. The lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) has been an effective therapeutic strategy as shown to initiate a cell death pathway, cancer cells usually exhibit weaker lysosomal membranes compared to noncancerous cells, they can be selectively sensitized to cell death6, 7, 8. The release of lysosomal contents, such as cathepsins, into cytosol and trigger cell death in a caspases-dependent or -independent pathway7. The acidic environment in lysosomes (pH 4.5–5.0) is required for lysosomal hydrolases activity and it is maintained by vacuolar-type adenosine triphosphatases. Cysteine and aspartic cathepsins function are active and stable at an acidic environment, and participate in LMP progression to a certain extent9,10.

Many factors contribute to LMP, including reactive oxygen species (ROS), lysosomal membrane lipid composition, proteases, P53, and B cell lymphoma-2 family proteins10. Among them, lipids overloading has been reported to promote lysosomal dysfunction and trigger cell death via LMP. LMP can be induced by high-fat feeding and fatty acid exposure, leading to the release and activation of the lysosomal protease11. Lipids include fatty acids, sphingolipids, sterols and phospholipids, and their contents and distribution undergo dynamic regulation. A prominent and relatively well-studied example is cholesterol, an essential constituent in mammalian cell membranes, which has unique biophysical properties to regulate membrane structure and property12. Lysosomes play as a regulator in maintaining cholesterol homeostasis, and stability and function of lysosomes is controlled by cholesterol10, 11, 12, 13. Free cholesterol is highly insoluble and cannot diffuse within the aqueous environment of the lysosomal lumen and impairs lysosomal function11,12. Previous researches have provided ample proofs to link lysosomal cholesterol accumulation with cell death, which is associated with lysosomal destabilization, dysfunction, membrane permeabilization, autophagy blockage, and even mitochondria damage14, 15, 16, 17.

Cholesterol is enriched in the plasma membrane and membranes of early endocytic organelles but not in the lysosome. Endocytic system participates in sorting and delivery of cholesterol, and most of the cholesterol normally leaves the endosome membrane in endocytic pathway before entering lysosomes13,18. Therefore, it requires the concerted action of two proteins known as NPC intracellular cholesterol transporter 1 (NPC1) and NPC2, which appear to be crucial for moving cholesterol out of the late endosomes. Intraluminal NPC2 binds cholesterol and delivers it to membrane protein NPC1, which is then transferred to the endoplasmic reticulum18. The blockage of NPC1/2 promotes addition of cholesterol to lysosomes, enlarges the lysosomes and triggers lysosomal failure. Overexpression of NPC1 or NPC2 reduced cholesterol accumulation14,19,20. Abnormal lysosome cholesterol accumulation induces leakage of lysosomal contents, leading to cell apoptosis21.

Various studies have shown ways to eliminate leukemia cells by interfering lysosomes, which due to sensitivity of leukemia cells to lysosomal disruption3,4,22. Here, we discovered that LW-218, a new derivative of wogonin, could interfere the cholesterol trafficking and then induce lysosome damage in hematological malignancy cells. The damaged lysosomes were cleared by macroautophagy (lysophagy). We also found the expression of autophagy-related and lysosomal biogenesis genes was associated with calcium–calcineurin (CaN)–transcription factor EB (TFEB) axis. However, sustained lysosomal damage blocked the autophagy flux eventually, and leakage of contents from damaged lysosomes resulted in cell death. We illustrated the necessary impact of integral lysosomal function in cell rescue and death.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture and reagents

Human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell lines (Jurkat and MOLT-4), T cell lymphoma cell lines (HuT 102 and HuT 78), acute myeloid leukemia cell line (THP-1), and human embryonic kidney cells (293T) were purchased from Cell Bank of Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry & Cell Biology (Shanghai, China). Primary leukemia cells from newly diagnosed leukemia patients (the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors were collected using lymphocyte–monocyte separation medium (Jingmei, Nanjing, China). A signed informed consent was obtained from each patient and donors. The suspended cell lines and primary leukemia cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (GIBCO, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and 293T cells were cultured in DMEM medium (GIBCO). The mediums were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, GIBCO), 100 U/mL of benzylpenicillin (Lukang, Jining, China) and 100 U/mL of streptomycin (Lukang) in a humidified environment with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. LW-218 was synthesized and provided by Prof. Zhiyu Li in our laboratory. Bafilomycin A1 (BAF A1; KGATGR007) and Lysotracker RED (KGMP006) were purchased from KeyGen Biotech (Nanjing, China), ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) was purchased from HUSHI (Shanghai, China), necrostatin-1 (HY-15760), acridine orange (AO; HY-101879) and MG-132 (HY-13259) were purchased from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA), Z-VAD-fmk (CSN15936), chloroquine (CSN11173), BAPTA-AM (CSN10377), cyclosporine A (CsA; CSN19509), FK-506 (CSN15684), 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (CSN23287), ML282 (CSN25306), and rapamycin (CSN16385) were purchased from CSNpharm (Chicago, USA), dexamethasone (Dex) sodium phosphate injection was purchased from Cisen (Jining, China), lysosensor GREEN (40767ES50) and Cell Counting Kit (CCK8, 40203ES60) was purchased from YEASEN Biotech (Shanghai, China), antifade mounting medium (P0126), antifade mounting medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI; P0131), 2,7-dichlorodi-hydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA; S0033S) and Flou3-AM (S1056) was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Nanjing, China), ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA; 324626) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies: active caspase 3 (A11021), caspase 3 (A2156), caspase 9 (A0281), caspase 8 (A0215), β-actin (AC026), BH3-interacting domain death agonist (BID; A0210), cathepsin B (CTSB; A19005), lysosomal-associated membrane proteins 2 (LAMP2; A1961), microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3; A17424), lysine 48 (K48)-linkage (A18163), lysine 63 (K63)-linkage (A18164), sequestosome 1 (P62/SQSTM1; A19700), lamin A/C (A19524) and galectin-3 (A13506; ABclonal Technology, Wuhan, China), lysosomal-associated membrane proteins 1 (LAMP1; 15665, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), cathepsin D (CTSD; ab75852) and TFEB (ab267351; Abcam, UK), RAS-related protein RAB-7a (RAB7A; 55469-1-AP), ubiquitin (10201-2-AP) and LC3 (14600-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Chicago, IL, USA), ubiquitin (sc-271289; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA). Alexa Fluor 488 (A-11008 and A-11001) and Alexa Fluor 594 (R37117 and A-11032; ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), Andy Fluor™ 405M goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) (L103A) antibody (ABP Biosciences, Wuhan, China).

All experiments using human samples were approved by the Review Board of China Pharmaceutical University and Affiliated DrumTower Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School, and all donors were provided informed consent. Ethics number of animal experiments: 2020-09-010; ethics number of clinical patient cells: 2020-325-01.

2.2. Cell apoptosis

The cells were collected and labeled with Annexin V and PI according to the protocols of Annexin V/PI Cell Apoptosis Detection Kit (A211-02; Vazyme biotec, Nanjing, China)23. The fluorescence was detected by Becton–Dickinson FACS Calibur flow cytometry (NJ, USA) and the data analysis was performed by Flowjo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

2.3. Mitochondrial membrane potential assay

The cells after treatment were harvested and processed with JC-1 (C2006; Beyotime Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instruction23. Then, processed cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

2.4. ROS levels detection

The cells after treatment were harvested and stained with DCFH-DA (10 μmol/L, diluted in serum-free medium; S0033S, Beyotime Biotechnology). The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. Then cells were washed by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 3 times. Finally, the cells were resuspended in PBS and detected by flow cytometry.

2.5. Western blot

Whole cell lysates were extracted from cells after treatment by RIPA buffer (89901, ThermoFisher). For nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction, the proteins were extracted using the extraction buffers (KGP150, KeyGen Biotech). The concentration of protein was determined by BCA Protein Assay Kit (23227, ThermoFisher). Equal amounts of lysate protein were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose filter membrane followed by Western blot. Immunodetection was performed using an enhanced chemiluminescence ECL system (36222ES60, YEASEN). The binding affinity of LW-218 and drug targets was detected by Amersham Imager 600 (General Electric Company, Schenectady, NY, USA)24. The blots are representative of multiple independent experiments.

2.6. CCK8 assay

15 μL CCK8 solution (40203ES60, YEASEN) was added to each well, and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C after PBMCs, leukemia cell lines and primary cells seeded in 96-well plates were treated with LW-218 for 24 h. Cells treated with equivalent amounts of dimethyl sulfoxide (D2650, Sigma–Aldrich) were used as negative control. Absorbance was read at 450 nm with a SynergyTM HT multi-mode reader (Bio-Tek, Winoosky, VT, USA). The average value of the optical density (OD) of five wells was used to determine cell viability according to Eq. (1):

| (1) |

50% inhibiting concentration values were taken as the concentration that caused 50% inhibition of cell viability and were calculated by the logit method.

2.7. Lysotracker RED and lysosensor GREEN staining

The cells stained with 0.5 μmol/L lysotracker RED (KGMP006, KeyGen Biotech) for 45 min in cell culture medium at 37 °C were analyzed the lysosomal mass. And for analyzing the lysosomal acidic levels, the cells stained with 1 μmol/L lysosensor GREEN (40767ES50, YEASEN) for 20 min in cell culture medium at 37 °C. After washed by PBS, the processed cells were suspended and analyzed by flow cytometry or detected by fluorescence microscope.

2.8. Calcium levels detection

The cytoplasmic calcium levels were determined by fluorescence probe Fluo3-AM. After treatment, the cells were incubated with 1 μmol/L Fluo-3-AM in PBS at 37 °C for 40 min, washed and suspended by PBS. The cells were analyzed by flow cytometry at 488 nm.

2.9. Xenografts assay

For in vivo experiments, LW-218 was prepared as intraperitoneal injection administration formulation by Dr. Xue Ke from College of Pharmacy, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing, China. Female NOD/SCID mice (5 weeks, 16–20 g, Slaccas Shanghai Laboratory Animal Co., Shanghai, China) were sublethally irradiated (1.5 Gy). Jurkat cells were suspended in a 2:1 in serum-free RPMI-1640 medium with a Matrigel basement membrane matrix (Sigma–Aldrich, E1270). Cells (5 × 106 counts) were inoculated in the right legs of mice. After tumor inoculation for 10 days, the mice were assigned into four treatment groups (4 mice per group). LW-218 (7.5 and 10 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection for every second day for three weeks), Dex (5 mg/kg, successive daily intraperitoneal injection for 5 days/week for three weeks) was administered, respectively. The tumor diameters were measured and tumor volume (mm3) was calculated as Eq. (2):

| (2) |

Tumor tissues were sectioned and subjected to immunofluorescence to detect the distribution and expression of targeted proteins.

2.10. Transfections and RNA interference

Transfections were achieved using LipoMAX (32011; SUDGEN Biotech, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Cells were transfected with 3 μL LipoMAX and 3 μg plasmids encoding galectin-3-mcherry (#85662), LC3-GFP (#11546) and LC3-GFP-mcherry (#123235, Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA) in 500 μL serum-free medium. After 72 h incubation, the transfection mixture was removed and replaced with fresh complete medium. For RNA interference by lentiviral vectors, autophagy related 7 (ATG7) short hairpin RNA (shRNA), transient receptor potential mucolipin 1 (TRPML1) shRNA, CTSD shRNA, CTSB shRNA constructs and a negative control construct created in the same vector system (pLKO.1) were purchased from Corues Biotechnology. Before transfection, 293T cells were plated in 12-well dishes. Cells were co-transfected with shRNA constructs (10 μg) together with Lentiviral Mix (10 μL) and HG Transgene™ Reagent (60 μL) according to the manufacturer's instructions of Lentiviral Packaging Kit (YEASEN, 41102ES20) for 48 h. Viral stocks were harvested from the culture medium and filtered to remove non-adherent 293T cells. To select for the Jurkat cells that were stably expressing shRNA constructs, cells were incubated in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FBS and 2 μg/mL of puromycin for 48 h after lentivirus infection. After selection cells, stably infected pooled clones were harvested for use.

2.11. Real time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis

For RNA isolation and RT-qPCR25, total RNA was extracted using RNA Isolater Total RNA Extraction Reagent (R401-01, Vazyme biotec). One microgram of total RNA was used to transcribe the first strand cDNA with HiScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (R312-01, Vazyme biotec), and RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Q131-02, Vazyme biotec) and specific PCR primers (5′–3′; GENEWIZ, Suzhou, China):

ATG5 (F: TCAGCCACTGCAGAGGTGTTT; R: GGCTGCAGATGGACAGTTGCA);

ATG12 (F: CAGTTTACCATCACTGCCAAAA; R: ACAAAGAAGTGGGCAGTAGAGC);

GAPDH (F: AGCCACATCGCTCAGACAC; R: GCCCAATACGACCAAATCC);

ULK1 (F: ACGACTTCCAGGAAATGGCTA; R: GGAAGAGCCTGATGGTGTCCT);

LC3 (F: GAACGATACAAGGGTGAGAAGC; R: TACACCTCTGAGATTGGTGTGG);

P62 (F: GAGAGTGTGGCAGCTGCCCT; R: GGCAGCTTCCTTCAGCCCTG);

CTSB (F: TTAGCGCTCTCACTTCCACTACC; R: TGCTTGCTACCTTCCTCTGGTTA);

CTSD (F: GCCAGGACCCTGTGTCG; R: GCACGTTGTTGACGGAGATG);

TFEB (F: GCGGCAGAAGAAAGACAATC; R: CTGCATCCTCCGGATGTAAT);

ATG7 (F: GGAGATTCAACCAGAGACC; R: GCACAAGCCCAAGAGAGG);

TRPML1 (F: GCGCCTATGACACCATCAA; R: TATCCTGGACTGCTCGAT);

Beclin-1 (F: TGTCACCATCCAGGAACTC; R: CTGTTGGCACTTTCTGTGG).

2.12. Immunofluorescence

Cells were collected and washed by PBS for 2 times and smeared on the cover glass. Then the cells were fixed in ice-cold methanol for 15 min and permeabilized in 0.15% Triton X-100 (X100-500 ML, Sigma–Aldrich) for 20 min. After blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (A3858-100G, Sigma–Aldrich) for 1 h in room temperature, the cells were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubated with Alexa Fluor secondary antibody for 1 h and DAPI. The cells were observed with a confocal laser scanning microscope (Fluoview FV1000, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

2.13. AO staining

After stained with 5 μmol/L AO solution in culture medium for 15 min before collecting, the cells were washed by PBS for 2 times and smeared on the cover glass, after which observed with a confocal laser scanning microscope.

2.14. Filipin staining

After treatment, the cells were collected and washed by PBS for 2 times and smear on the cover glass, and then fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, washed by PBS and incubated with 1.5 mg/mL glycine for 10 min. The cells were rinsed with PBS and incubated with 50 μg/mL Filipin III (B6034, APExBIO Technology, TX, USA) containing 10% FBS for 2 h at room temperature in the dark, followed by observed with a confocal laser scanning microscope.

2.15. Indirect flow cytometry assay

After treated and washed by PBS for 2 times, the cells were fixed by 75% ethanol at 4 °C for 2 h and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min. The cells were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, and then was labeled by the secondary antibody with fluorescent dye. The fluorescence was detected by Becton–Dickinson FACS Calibur flow cytometry.

2.16. Docking analysis

The structural model of NPC1 (PDB ID, 3GKI) and NPC2 (PDB ID, 1NEP) were used to determine the interactions with LW-218, and the results were analyzed using AutoDock software (the Scripps Research Institute, USA).

2.17. Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) from at least three independent experiments performed in a parallel manner. Statistical analysis of multiple group comparisons was performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by the Bonferroni post-hoc test. Comparisons between two groups were analyzed using two-tailed Student's t-tests. A P value < 0.05 was considered as significant.

3. Results

3.1. Lysosome alkalizing agents attenuate LW-218-induced cell apoptosis

The T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell lines (Jurkat and MOLT-4), T cell lymphoma cell lines (HuT 102 and HuT 78) and acute myeloid leukemia cell line (THP-1) were used to determine the cytotoxicity of LW-218. Cell apoptosis was induced in Jurkat and THP-1 cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). BAF A1 and NH4Cl are lysosome alkalizing agents that can cause the lysosomal alkalinization26, which reversed LW-218-induced apoptosis (Fig. 1B and C and Supporting Information Fig. S1A and S1B) and LW-218-reduced mitochondria membrane potential (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, LW-218-induced apoptosis correlated with increased ROS levels (Fig. 1E) and the activation of caspases, including caspases 3, 9, and 8 (Fig. 1F–H and Fig. S1C–S1F), as well as the cleavage of BID (tBID, activation form of BID) (Fig. S1G). Pan-caspase inhibitor (Z-VAD-fmk) led to about 20% reduction in LW-218-induced apoptosis (Fig. 1I and Fig. S1H), which was not affected by necroptosis inhibitor (Fig. S1I). To a certain extent, it indicated that caspases-dependent pathway was involved in LW-218-induced apoptosis, which relied on the acidification of lysosome, and could be reversed by the alkalinization of lysosome.

Figure 1.

Bafilomycin A1 (BAF A1) and ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) reverse LW-218-induced apoptosis in leukemia and lymphoma cells. (A) Apoptosis cells (%) were determined in Jurkat and THP-1 cells treated with 8 μmol/L of LW-218 for different time periods. (B) Apoptosis cells (%) were determined in Jurkat cells cotreated with LW-218 and BAF A1 (7.5 nmol/L) for 12 h. (C) Apoptosis cells (%) were determined in Jurkat cotreated with LW-218 and NH4Cl (10 mmol/L) for 12 h. All of apoptosis cells (%) detection were detected by Annexin V/PI staining and flow cytometry (apoptosis cells are positive for Annexin V). (D) The Jurkat cells were cotreated with LW-218 and BAF A1 (7.5 nmol/L) or NH4Cl (10 mmol/L) for 12 h. The membrane potentials of mitochondria (ΔΨm) were determined by JC-1 assay and flow cytometry. (E) The Jurkat cells were treated with LW-218 for 6 h and the reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels were determined by 2,7-dichloro-dihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) and flow cytometry. (F)–(H) The Jurkat cells were treated with LW-218 and BAF A1 (7.5 nmol/L) for 12 h. The expression of caspase 3, caspase 8, and caspase 9 were detected by Western blot. β-Actin was used as loading control. (I) The Jurkat cells were cotreated with LW-218 and Z-VAD-fmk (10 μmol/L; pre-treated for 1 h) for 12 h. The apoptosis cells (%) were determined by Annexin V/PI staining. (J) and (K) Average tumor weight (J) and average tumor volume (K) in control mice, mice treated with LW-218 (7.5 and 10 mg/kg) or dexamethasone (Dex, 5 mg/kg). Data are mean ± SEM for ≥3 independent experiments; P values are shown on the graph.

We also examined the in vivo effects of LW-218 on a NOD/SCID mice xenograft model. The mice were inoculated subcutaneously with Jurkat cells and received LW-218 (7.5 and 10 mg/kg) and Dex (5 mg/kg). Compared to untreated controls, LW-218 led to a significant reduction in tumor growth with slight effect on body weight (Fig. 1J and K and Supporting Information Fig. S2A). LW-218 and Dex treatment caused a marked increase of active caspase 3, indicative of apoptosis (Fig. S2B). Our in vitro findings of apoptosis induction by LW-218 also were replicated in primary cells (Fig. S2C). Compared with leukemia cells lines, there were a discrepancy between primary leukemia cell samples in apoptosis effects of LW-218. In addition, we confirmed that the cytotoxicity of LW-218 was more apparently on hematological malignancies cells (including cell lines and primary cells) than normal cells (PBMCs, Fig. S2D and S2E), indicating selective cytotoxicity of LW-218 on cancer cells. Collectively, these data suggest antitumor effects of LW-218 in vitro and in vivo.

3.2. LW-218 induces rapid lysosomes damage and LMP

Due to the reversion effects of lysosome alkalizing agents on LW-218-induced apoptosis, we evaluated the effects of LW-218 on lysosomes. First, lysotracker RED staining was used to detect the alteration of lysosomal morphology after LW-218 treatment, and the abnormal enlargement of lysosomes was observed at a short time (0.5 h, Fig. 2A). Galectin-3, which distributed throughout the cytoplasm and nuclei, is recruited to injured lysosomes and forms galectin-3 puncta27. The lysosomes were damaged in cells treated with LW-218, as visualized by the formation of galectin-3 puncta at 1 h (Fig. 2B), and this effect was proved in vivo (Supporting Information Fig. S3A). We also observed the LW-218-induced formation of galectin-3 puncta could be reversed by BAF A1 (Fig. 2B), indicating that LW-218-induced lysosomal damage relied on the acidic environment of lysosomes.

Figure 2.

Cathepsins involve in LW-218-induced lysosomal damage and cell apoptosis. (A) The Jurkat cells treated with 8 μmol/L LW-218 for 0–8 h were labeled with lysotracker RED and determined by flow cytometry (right) and fluorescence microscope (left). The area ratio of lysosomes/cells was analyzed. (B) The Jurkat and THP-1 cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding mCherry-galectin-3 and were treated with LW-218 and BAF A1 (7.5 nmol/L) for 1 h. The galectin-3 puncta determined by fluorescence microscopy, and galectin-3 puncta-positive cells ratio was calculated (total cells in each group >100). (C) The Jurkat cells treated with 8 μmol/L LW-218 for 0–8 h were stained with lysosensor GREEN and determined by flow cytometry. (D) The Jurkat cells treated with 8 μmol/L LW-218 for 0–8 h were stained with Fluo3-AM, the cytosolic calcium levels were determined by flow cytometry. (E) The Jurkat cells were cotreated with LW-218 and BAF A1 (7.5 nmol/L) for 4 h. The immunofluorescence analysis performed with anti-cathepsin B (CTSB) antibody (green), anti-lysosomal-associated membrane proteins 1 (LAMP1) antibody (red; lysosome). (F) The Jurkat cells cotreated with LW-218 and BAF A1 for 2 or 12 h, and the cytosolic calcium levels were determined. (G) The Jurkat cells were treated with 8 μmol/L LW-218 for 0–8 h. The immunofluorescence analysis performed with anti-CTSB antibody (green), and the CTSB puncta-positive cells ratio was calculated (total cells in each group >100). (H) The Jurkat cells stably-transfected with a CTSB or CTSD short hairpin RNA (shRNA) were treated with LW-218 for 8 h, and the apoptosis cells (%) were determined by Annexin V/PI staining and flow cytometry. (I) and (J) The CTSB or cathepsin D (CTSD) shRNA-expressing and control cells (Jurkat) were transfected with a plasmid encoding galectin-3-mcherry, and then treated with LW-218 for 0, 15, 45, and 100 min. The galectin-3 puncta determined by fluorescence microscopy, and galectin-3 puncta-positive cells ratio (I) and galectin-3 puncta counts/per cell (J) was calculated (total cells in each group >100). Data are mean ± SEM for ≥3 independent experiments; P values are shown on the graph.

Lysosomes are acidic organelles with a high intravesicular calcium concentration and over fifty hydrolases, which release from the lysosomal lumen when LMP occurs7,9,28. To assess whether LW-218 treatment leads to LMP, we determined the acidic levels of lysosomes, cytosolic calcium levels and cathepsins redistribution. The reduction of acidification (Fig. 2C and Fig. S3B), enhancement of cytoplasmic calcium levels (Fig. 2D and Fig. S3C), and the cytosolic-localization of CTSB (Fig. 2E) demonstrated that LW-218 treatment led to LMP. Besides, the inhibition of BAF A1 on leakage of CTSB (Fig. 2E) and cytosolic calcium levels (12 h, Fig. 2F) indicated BAF A1 blocked LW-218-induced LMP following lysosomal damage. However, BAF A1 was unable to suppress cytosolic calcium levels at 2 h (Fig. 2F), suggesting that a potential mechanism of calcium releasing was LMP, but not the only one. Therefore, in order to determine the timing of LMP, the immunofluorescence assay of CTSB in different periods was performed. As shown in Fig. 2G, LMP occurred at 2 h after LW-218 treatment, and the same result was also proved by AO staining (Fig. S3D). It illustrated that the slight increase of calcium during 0–2 h wasn't mediated by LMP, and couldn't be inhibited by BAF A1, suggesting the possibility of channel-mediated calcium release.

Previous studies had confirmed the importance of leakage cathepsins in lysosome-dependent cell death7, we determined whether the cathepsins were involved in LW-218-induced apoptosis through transfecting cells with CTSB or CTSD by shRNA (Fig. S3E–S3F). Knockdown of CTSD by shRNA eliminated LW-218-induced apoptosis (Fig. 2H), cells with damaged lysosomes (Fig. 2I) and galectin-3 puncta counts significantly (Fig. 2J), but not lysosomal enlargement (Fig. S3G). We also found that BAF A1 inhibited the expression of active form of CTSD (Fig. S3H). These results suggested that CTSD, whose function relied on acidic environment, was required in LW-218-induced lysosomal damage and subsequent cell apoptosis.

3.3. Clearance of damaged lysosomes is dependent on autophagy

LMP is the consequence of the lysosomal membrane rupture and affects cellular homeostasis7. Damaged lysosomes are shown to be cleared by selective macroautophagy (herein referred to autophagy), as a cytoplasmic quality control mechanism, which can mediate the engulfment of injured lysosomes with autophagosomes and fusion into intact lysosomes for degradation27,29. Therefore, we suspected that injured lysosomes induced by LW-218 could be eliminated to maintain the cellular stabilization. The lysosome-associated membrane proteins (LAMPs) are the essential composition of the lysosome membrane. LAMP1/2 accounts for about 50% of all proteins in the lysosome membrane and sustains its integrity30. The reduction of LAMP2 after treatment with LW-218 reflects the decreasing amounts of lysosomes indirectly (Fig. 3A and Supporting Information Fig. S4A). Key elements of cellular degradation process involve the specific sensing of the damage followed by extensive modification of the lysosomes with ubiquitin to mark them for clearance27,31. As shown in Fig. 3B and Fig. S4B, the co-localization of ubiquitin and LAMP1/2 after LW-218 treatment indicated that lysosomes were ubiquitinated. We had proven that BAF A1 blocked LW-218-induced LMP. Although BAF A1 induced ubiquitin puncta slightly due to its lysosomal degradation inhibition, BAF A1 was able to inhibit LW-218-inducedlysosomal ubiquitylation significantly (Fig. 3B), suggesting BAF A1 decreased the lysosomal ubiquitylation due to its ability to restrain lysosome damage, instead of inhibiting the ability of lysosomal degradation. The results that BAF A1 could inhibit decrease of LAMP1/2 protein by LW-218 treatment also suggested the protective effects of BAF A1 in LW-218-induced lysosomal damage and LMP (Fig. 3C and Fig. S4C and S4D).

Figure 3.

Damaged lysosomes are ubiquitinated and cleared via autophagy pathway. (A) The Jurkat cells were treated with LW-218 (8 μmol/L) for 0–12 h and expression of LAMP2 were determined by Western blot. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis performed with anti-ubiquitin (red) antibody and anti-LAMP1 antibody (blue) in Jurkat cells (N.C, autophagy related 7 (ATG7) shRNA, and BAF A1 group) after treatment with LW-218 for 12 h. (C) The Jurkat and THP-1 cells were cotreated with LW-218 and BAF A1 for 12 h. The expression levels of LAMP2 were determined by Western blot. (D) The Jurkat cells stably-transfected with an ATG7 shRNA were treated with LW-218. The expression of LAMP2 was determined by Western blot, in which above β-actin was used as loading controls. (E) Immunofluorescence analysis performed with anti-microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3B (LC3B) antibody (green) in Jurkat cells transfected with a plasmid encoding mCherry-galectin-3 after treatment with LW-218, BAF A1 (7.5 nmol/L) and chloroquine (50 μmol/L) for 1 h or 6 h. (F) Immunofluorescence analysis performed with anti-LAMP1 antibody (blue) and anti-ubiquitin antibody (green) in Jurkat cells transfected with a plasmid encoding mCherry-galectin-3 after treatment with LW-218 for 6 h. (G) The Jurkat cells transfected with a plasmid encoding mCherry-galectin-3 were treated with LW-218 (6 μmol/L) for 1 h. After LW-218 washout (withdrawal group) or sustained action (sustain group), the positive for galectin-3 puncta cells ratio were calculated (total cells in each group >100). (H) The Jurkat cells stably-transfected with an ATG7 shRNA were transfected with a plasmid encoding mCherry-galectin-3. The N.C. cells and ATG7 shRNA cells were treated with LW-218 for 2 h and then washout. The positive for galectin-3 puncta were determined by fluorescence microscopy at 12 h after washed, and galectin-3 puncta-positive cells ratio was calculated (total cells in each group >100). Data are mean ± SEM for ≥3 independent experiments; P values are shown on the graph.

In order to investigate whether autophagy degradation pathway was involved in lysosome clearance, we inhibited autophagic vesicles formation by ATG7 shRNA transfection (Fig. S4E). ATG7 shRNA had no effect on lysosomal ubiquitylation (Fig. 3B). After LW-218 treatment, the cellular ubiquitylation levels was increased (Fig. S4F) and the degradation of LAMP2 was inhibited (Fig. 3D), indicating that clearance of lysosomes could be inhibited by blocking autophagy degradation using ATG7 shRNA. Furthermore, immunofluorescence assay showed that LC3 was recruited to galectin-3 puncta (Fig. 3E), and the damaged lysosomes labeled with galectin-3 were ubiquitinated (Fig. 3F). It suggests that autophagy was selective to LW-218-induced lysosome damage. Moreover, the drug withdrawal test was also performed to determine the dynamics of autophagy-dependent elimination of damaged lysosomes. Cells were exposed to LW-218 for 1 h, and then cultured in the absence of LW-218 for an additional 24 h. 2 h after removing LW-218, compared with sustain group, the galectin-3 puncta positive cell counts in withdrawal group were decreased significantly (Fig. 3G). However, in the cells transfected with ATG7 shRNA, the clearance of damaged lysosomes was inhibited after removing LW-218 (Fig. 3H and Fig. S4G). The above results indicate that the clearance of damaged lysosomes depended on autophagy pathway.

Besides, we detected different types of ubiquitin chains on damaged lysosomes. K63-linked chains recruit autophagy receptors, whereas the K48-linked chains are commonly associated with proteasome degradation31. Except for K63-linked chains, we observed LW-218-induced K48-ubiquitinated substrates of lysosomes (Fig. S4H–S4J). The phenomenon would not rule out the possibility of EndoLysosomal Damage Response complex was involved in LW-218-induced lysophagy, and the K48-linked chains might mediate the proteasome degradation of lysosomal substrates27.

3.4. Calcium mediated autophagy-related genes expression during lysophagy

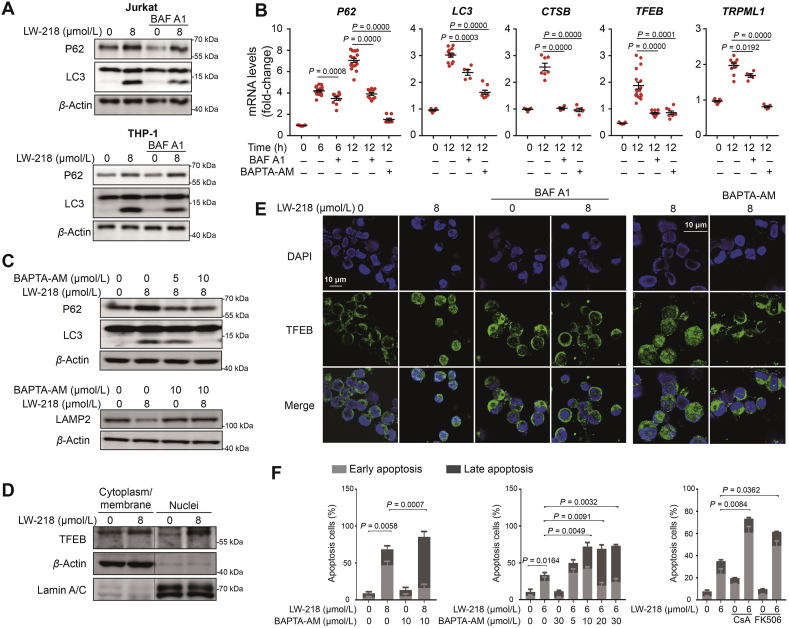

We explored the molecular mechanism in LW-218-mediated autophagy. LW-218 treatment led to accumulation of LC3II (Supporting Information Fig. S5A) and increase transcription of autophagy-related genes (Fig. S5B). LW-218-induced autophagy could be inhibited by BAF A1 (Fig. 4A and B and Fig. S5C). Previous studies have shown that calcium plays a crucial role in the regulation of transcription factors and regulates autophagy32,33, and LW-218 promoted the increase of cytosolic calcium levels (Fig. 2D). Thus, we assessed whether released of calcium from lysosomes can mediated the initiation of LW-218-induced autophagy. As shown in Fig. 4B, C and Fig. S5D, the transcription of autophagy-related genes, LC3II accumulation, P62 expression and LAMP2 degradation could be inhibited by intracellular calcium chelator BAPTA-AM, suggesting that calcium controlled the LW-218-induced autophagy. Besides, the use of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (endoplasmic reticulum calcium channel IP3R1 inhibitor) and EGTA (extracellular calcium chelator) excluded the effect of endoplasmic reticulum and extracellular calcium (Fig. S5E). It has been reported that TRPML1-mediated lysosomal calcium signaling regulates autophagy via CaN and TFEB32,33. We first demonstrated the nuclear translocation of TFEB after LW-218 treatment, which could be inhibited by BAF A1, BAPTA-AM and CaN inhibitors (CsA and FK-506, Fig. 4D, E and Fig. S5F–S5G). Consistent with a role of TRPML1 in lysosomal calcium release, the silencing of TRPML1 reduced the cytoplasmic calcium levels at 2 h (Fig. S5H), when calcium release without LMP (Fig. 2F). These results indicate that LW-218-induced autophagy-related genes expression might be mediated by calcium–CaN–TFEB signaling.

Figure 4.

LW-218 promotes autophagy-related gene expression via calcium–CaN–TFEB axis. (A) The Jurkat and THP-1 cells were cotreated with LW-218 and BAF A1 (7.5 nmol/L) for 12 h and the expression of LC3 and sequestosome 1 (P62/SQSTM1) were determined by Western blot. β-Actin was used as loading control. (B) The Jurkat cells were cotreated with LW-218 (8 μmol/L) and BAF A1 (7.5 nmol/L) or BAPTA-AM (10 μmol/L) for 6 h or 12 h. The inhibitors were pre-treated for 1 h. The total RNAs were extracted and messenger RNA levels were detected by real time quantitative PCR. Data are mean ± SEM for ≥3 independent experiments; P values are shown on the graph. (C) The Jurkat cells were cotreated with LW-218 and BAPTA-AM (5 or 10 μmol/L) for 12 h, and the expression of P62, LC3 and LAMP2 were determined by Western blot. β-Actin was used as loading control. (D) The Jurkat cells were treated with LW-218 for 12 h. The levels of transcription factor EB (TFEB) in cytoplasm/membrane and nuclei fractions were determined by Western blot. β-Actin and lamin A/C were used as cytoplasm/membrane and nuclei loading control, respectively. (E) Immunofluorescence analysis performed with anti-TFEB antibody (green) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI, blue) in Jurkat cells. The cells were cotreated with LW-218 and BAF A1 (7.5 nmol/L) or BAPTA-AM (10 μmol/L) for 12 h. The inhibitors were pre-treated for 1 h. (F) The Jurkat cells were cotreated with LW-218 and BAPTA-AM (10 μmol/L) or cotreated with LW-218 and CaN inhibitors for 12 h. The apoptosis cells were determined by Annexin V/PI staining and flow cytometry (apoptosis cells are positive for Annexin V). Data are mean ± SEM for ≥3 independent experiments; P values are shown on the graph.

Clearance of damaged organelles by autophagy protects cells survival31. LW-218-induced lysophagy protected the cells from damage of dysfunctional lysosomes. Therefore, apoptosis was accelerated when lysophagy was inhibited by BAPTA-AM or CaN inhibitors (Fig. 4F). It further illustrated that CaN and calcium were involved in autophagy regulation and the clearance of damaged lysosomes through autophagy was transient self-salvage of cells.

3.5. Persistent lysosomal damage inhibited the autophagy flux

Lysosomal degradation is the late-stage of autophagy26. We further confirmed that LW-218-induced lysosomal damage inhibited autophagic flux. As shown in Fig. 5A, in the cells transfected with LC3-GFP-mCherry, LW-218 increased the LC3-mcherry puncta during 45 min–2 h. LW-218 decreased the expression of P62 during 0–4 h in Jurkat cells and 0–2 h in THP-1 cells, respectively (Fig. 5B and Supporting Information Fig. S6A). These results indicate the normal degradation of autophagy. However, after treatment with LW-218 for 6 h in Jurkat cells, or for 4 h in THP-1 cells, the expression of P62, LC3I started to increase, and the pronounced LC3II accumulation indicated the cellular retention of autophagic vesicles (Fig. 5B and Fig. S6A). Exposing to LW-218, LC3 puncta displayed yellow overlay increased in a time-dependently manner (0–8 h, Fig. 5A). It suggests that persistent LW-218 treatment inhibited autophagy flux. Ubiquitinated proteins also showed a trend of decreasing and then increasing, proving the degradative substrates accumulation (Fig. 5C and Fig. S6B). And the autophagosomes-lysosomes fusion blockage occurred over time (Fig. S6C–S6E). We observed non-colocalization of LC3 and galectin-3 at timepoint of 12 h, also indicating large amount of autophagosomes accumulation due to lysosomal damage and degradative capacity failure (Fig. 5D). The autophagy inhibition was proved in tumor tissue. Accumulation of LC3 puncta and colocalization of LC3 and P62 were detected in LW-218-treated group, while it was not observed in Dex-treated group (Fig. S6F). It can be concluded that the degradation of substrates linked with P62 and LC3 was inhibited after LW-218 treatment. In addition, in the presence of BAF A1, LW-218-induced apoptosis still increased during 24–72 h, with the marked LC3II expression (Fig. S6G and S6H). These results show that LW-218-induced damaged lysosomes underwent autophagy degradation until autophagy inhibition occurred due to exhausted lysosomal degradative capacity.

Figure 5.

Lysosomal damage blocks the autophagy flux. (A) The Jurkat cells transfected with a plasmid encoding LC3-GFP-mCherry were treated with 8 μmol/L LW-218 for different time periods. The cells also treated with BAF A1 (7.5 nmol/L) and rapamycin (250 nmol/L). The colocalization of LC3-GFP and LC3-mCherry were detected by immunofluorescence. (B) The Jurkat and THP-1 cells were treated with 8 μmol/L of LW-218 for 0–12 h. The expressions of LC3 and P62 were determined by Western blot. (C) The Jurkat cells were cotreated with 8 μmol/L LW-218 and MG-132 (15 μmol/L, pre-treated for 1 h) for different time periods and the expression of ubiquitin were determined by Western blot. β-Actin was used as loading control. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis performed with anti-LC3B antibody (red) and galectin-3 (green) in Jurkat cells. The cells were with LW-218 for 12 h.

3.6. LW-218 induces lysosomal cholesterol accumulation via interacting with NPC1 proteins

BAF A1 can inhibit LW-218-induced lysosomal damage and apoptosis. However, LW-218 induced lysosomal enlargement regardless of the presence or absence of BAF A1 (Fig. 6A, arrows). Previous studies have confirmed that lysosomal cholesterol accumulation can enlarge the volume of organelles, and lysosomal cholesterol contents may play an important role in the maintenance of lysosomal membrane stability and cell death10,13,14. Sensitivity to lysosome-dependent cell death is directly regulated by lysosomal cholesterol content2. Atorvastatin, an inhibitor of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibits the synthesis of cholesterol, could delay the enlargement of lysosomes induced by LW-218 (Fig. 6B). Filipin staining also demonstrated the lysosomal cholesterol accumulation (Fig. 6C and Supporting Information Fig. S7A).

Figure 6.

LW-218 induces lysosomal cholesterol accumulation. (A) and (B) The Jurkat cells were cotreated with LW-218 (8 μmol/L) and BAF A1 (7.5 nmol/L, pre-treated for 1 h) or atorvastatin (10 μmol/L, pre-treated for 6 h) for 0–12 h, and labeled with lysotracker RED. The fluorescence intensity was determined by flow cytometry. (C) Immunofluorescence analysis performed with filipin (blue) and LAMP1 (red) in Jurkat cells treated with LW-218 for 6 h. (D) The Jurkat cells were stained with lysotracker RED and determined by flow cytometry after cotreated with LW-218 and ML282 (5 μmol/L, pre-treated for 2 h) for 2 and 12 h. (E) and (F) The Jurkat cells transfected with a plasmid encoding galectin-3-mCherry were cotreated with LW-218 (8 μmol/L) and atorvastatin (10 μmol/L, pre-treated for 6 h) or ML282 (5 μmol/L). The cells were determined by fluorescence microscopy. The galectin-3 puncta-positive cells ratio (E) and galectin-3 puncta counts/per cell (F) were calculated (total cells in each group >100). Data are mean ± SEM for ≥3 independent experiments; P values are shown on the graph.

And then, we inhibited the fusion of late endosomes and lysosomes by using ML282, an inhibitor of RAB7A, which reduced the enlargement of lysosomes (Fig. 6D). However, atorvastatin and ML282 couldn't reverse LW-218-induced apoptosis (Fig. S7B and S7C), only delayed the lysosomal damage temporarily (Fig. 6E), as well as the damage degree (Fig. 6F). We hypothesized that the lysosomal damage occurred only when lysosomal cholesterol accumulation exceeded the threshold of membrane stabilization. Reducing cholesterol synthesis or transport could delay, but not prevent, cholesterol accumulation to this threshold.

According to the cellular thermal shift assay results that NPC1 was more stable than NPC2 after LW-218 treatment (Fig. 7A), and binding of LW-218 and NPC1 (Fig. 7B–E) shown by molecular docking examination, we confirmed that LW-218-induced cholesterol accumulation on lysosomal membrane might result from the inhibition of NPC1, instead of NPC2. The binding scores of NPC1 and NPC2 were 73.329 and 41.384, respectively. And the binding free energy of LW-218 with NPC1 or NPC2 were −8.429 and −3.698 kcal/mol. Molecular docking also indicated that LW-218 forms an electrostatic bond with Tyr192 residue, which locates in N-terminal domain (NTD), a domain accepts the handoff of cholesterol from the soluble protein NPC234. These results above indicate that LW-218-induced lysosomal cholesterol accumulation was mediated by NPC1 inhibition.

Figure 7.

The interaction between LW-218 and NPC intracellular cholesterol transporter 1 (NPC1) protein. (A) The Jurkat cells were treatment with dimethyl sulfoxide or 8 μmol/L LW-218 for 6 h, and the cells were collected and divided equally into 9 tubes, respectively. After incubated in different temperature in a gradient style, the cells underwent freezing and thawing cycles in liquid nitrogen for three times. After protein denaturation, NPC1 and NPC2 were determined by Western blot. β-Actin was used as loading control, and protein qualification were analyzed by gray scale. Data are mean ± SEM for ≥3 independent experiments; P values are shown on the graph. (B)–(E) Molecule docking examination of LW-218 and NPC1 (PDB ID: 3GKI) or NPC2 (PDB ID 1NEP) protein. NPC1 binding mode (B) and 2D interaction map of LW-218 (C). NPC2 binding mode (D) and 2D interaction map of LW-218 (E).

4. Discussion

Therapeutic targeting to lysosomes as a novel anticancer strategy. It has been under extensive investigation due to the reliance of cancer cells on lysosomes. Tumor cells rely more on over-active lysosomal function35, 36, 37, present modifications on lysosomes, and exhibit weaker lysosomal membranes as compared to noncancerous cells, making them more vulnerable to lysosomal dysregulation4,6,38. Lysosome-dependent cell death (LCD) is a cell death pathway characterized by lysosomal destabilization, and LMP is an effective therapeutic strategy, as LMP have shown that this form of cell death is not just a “suicide bags”. LMP is an effective way to kill many different cancer cell types39. Targeting lysosomes therefore has great therapeutic potential in cancer, because it not only triggers apoptotic and lysosomal cell death pathways but also inhibits cytoprotective autophagy6. The lysosome also has been found to contribute to chemotherapy resistance in cancer40,41. Lysosomes play an important role in cancer drug resistance by sequestering cancer drugs in their acidic environment, resulting in a bluntness of the drugs' effects42. Therefore, the lysosome could be considered an Achilles’ heel of cancer cells. Development of a new agent of targeting lysosomes for the treatment of cancer has an important clinical significance. Various agents targeting lysosomes, either alone or in combination with other chemotherapy agents have shown significant anti-tumor effects. For example, in leukemia, lysosomal dysfunction has been an effective strategy to against leukemia and leukemia stem cells without significant toxicity in normal cells4,43. Lysosomotropic agent siramesine eliminates chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells selectively by altering metabolism of sphingolipid44. Mefloquine has the cytotoxicity effects on chronic myelocytic leukemia cells via lysosomal-lipid damage3.

In this study, we demonstrated LW-218, a new flavonoid compound, targeted lysosomes and induced LCD for eliminating hematological malignancy cells (Fig. 8). In vitro experiments, LW-218 induced cell apoptosis significantly in cell lines and primary cells. In vivo study, LW-218 inhibited tumor growth in a Jurkat mouse xenografts model. For mechanisms, LW-218 suppressed the endocytic cholesterol trafficking by inhibiting the NPC1, and then induced undischarged cholesterol deposited on lysosomal membrane. The lipotoxicity elicited CTSD-mediated lysosomal-associated reaction, including lysosomal damage, subsequent LMP and LCD. These effects could be inhibited by BAF A1 due to the dependency of CTSD on acidic environment of lysosomes9. However, the inhibition of BAF A1 on LW-218-induced apoptosis was also temporary. LW-218-induced apoptosis could be still detected during 24–72 h in the presence of BAF A1 (Fig. S6G and S6H). We speculated that the apoptosis resulted from cholesterol deposition, or the overload accumulation of autophagic vesicles. In the process of LW-218 treatment, lysophagy was triggered to maintain the cellular homeostasis by dysfunctional lysosomes clearance. TRPML1-released calcium might mediate TFEB nuclear translocation and expression of autophagy- and lysosome biogenesis-related genes. Previous studies have indicated that sphingomyelins, a class of membrane lipids, inhibit TRPML1 and block release of calcium45. The cholesterol/sphingomyelins trafficking defects induce lipid accumulation and Niemann-Pick type C (NPC) disease45,46. However, in this diseases, cholesterol accumulation is believed to appear first, as a result of defective function of the NPC1 or NPC2 proteins, and the cholesterol/sphingomyelin ratio is much higher47. We hypothesized that rapid cholesterol accumulation interferes with the sphingomyelin's normal function of inhibiting TRPML1, and resulted in TRPML1 channel activation.

Figure 8.

The proposed mechanism of LW-218-induced lysosomal damage, lysophagy and apoptosis.

NPC1 is required for cholesterol export in endocytic system and lysosomes. Its mutation is always associated with cholesterol accumulation disease46. Previous studies have confirmed the overexpression of NPC1 has a positive significance on NPC disease treatment20. However, consistent with our findings, we provided new insight into the anti-cancer effects of cholesterol mediated by inhibiting NPC1, which might be a novel target for cancer therapy. This is facilitated by the characteristic of poor cholesterol in lysosomal membrane, leading to sensitivity to abnormal cholesterol accumulation13. Based on the reliance of cancer cells on lysosomes, it is possible to target lysosomes by inhibiting NPC1 for tumor treatment. Although there are several NPC1 inhibitors, such as U18666A, itraconazole and leelamine, research of anticancer effects of these inhibitors on hematological malignancies are rare48. Thus, the results of LW-218 made it possible for NPC1 inhibitors as novel anticancer drugs.

It is promising to find new agent candidates that can specifically target tumor cell lysosomes in a safe, effective and anti-resistant manner49, and LW-218 showed low-toxicity effects on normal cells. However, the damage of drugs targeting the lysosomes to normal cells cannot be ruled out, and it is also cytotoxic to normal cells by these agents with improper concentration. Therefore, it is necessary to select the appropriate concentration for killing tumor cells without damaging normal cells. Of course, it is not enough to kill cancer cells by just relying on the destructive effects on lysosomes of LW-218. By interfering with lysosomes to block protective autophagy, chemotherapeutic resistance can be reduced. Therefore, combination of LW-218 with chemotherapy may be a safe and effective strategy for cancer treatment.

5. Conclusions

We demonstrated the dynamics and mechanism of LW-218-induced lysosomal damage, clearance and LCD, as well as inhibition of NPC1 as a novel strategy for cancer treatment. Based on the research above of LW-218, we also emphasized the necessary impact of integral lysosomal function in cell rescue and death.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the Nation Natural Science Foundation of China (81873046, 81830105, 81903647, 81503096, and 81673461), the Drug Innovation Major Project (2017ZX09301014, 2018ZX09711001-003-007, and 2017ZX09101003-005-023, China), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu province (BK20190560 and BE2018711, China), Nanjing Medical Science and Technology Development Project (YKK17074 and YKK19064, China), Research and Innovation Project for College Graduates of Jiangsu Province (KYCX18_0803, China), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2018M642373) and “Double First-Class” University project (CPU 2018GF11 and CPU2018GF05, China).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2021.02.004.

Contributor Information

Qinglong Guo, Email: anticancer_drug@163.com.

Hui Hui, Email: moyehh@163.com.

Author contributions

Po Hu and Hui Li designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. Wenzhuo Sun and Xiaoxuan Yu performed research and analyzed data. Yingjie Qing performed research. Zhanyu Wang collected data and performed statistical analysis. Hongzheng Wang and Mengyuan Zhu collected and analyzed data. Prof. Jingyan Xu provided the blood samples, and Prof. Qinglong Guo and Prof. Hui Hui conceptualized the project and directed the experimental design and data analysis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Yu F., Chen Z., Wang B., Jin Z., Hou Y., Ma S. The role of lysosome in cell death regulation. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:1427–1436. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4516-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appelqvist H., Sandin L., Bjornstrom K., Saftig P., Garner B., Ollinger K. Sensitivity to lysosome-dependent cell death is directly regulated by lysosomal cholesterol content. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lam Yi H., Than H., Sng C., Cheong M.A., Chuah C., Xiang W. Lysosome inhibition by mefloquine preferentially enhances the cytotoxic effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in blast phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Transl Oncol. 2019;12:1221–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sukhai M.A., Prabha S., Hurren R., Rutledge A.C., Lee A.Y., Sriskanthadevan S. Lysosomal disruption preferentially targets acute myeloid leukemia cells and progenitors. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:315–328. doi: 10.1172/JCI64180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gyparaki M.T., Papavassiliou A.G. Lysosome: the cell's ‘suicidal bag’ as a promising cancer target. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:239–241. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piao S., Amaravadi R.K. Targeting the lysosome in cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1371:45–54. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boya P., Kroemer G. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization in cell death. Oncogene. 2008;27:6434–6451. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Postovit L., Widmann C., Huang P., Gibson S.B. Harnessing oxidative stress as an innovative target for cancer therapy. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:6135739. doi: 10.1155/2018/6135739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Repnik U., Stoka V., Turk V., Turk B. Lysosomes and lysosomal cathepsins in cell death. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1824:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson A.C., Appelqvist H., Nilsson C., Kagedal K., Roberg K., Ollinger K. Regulation of apoptosis-associated lysosomal membrane permeabilization. Apoptosis. 2010;15:527–540. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0452-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaishy B., Abel E.D. Lipids, lysosomes, and autophagy. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:1619–1635. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R067520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thelen A.M., Zoncu R. Emerging roles for the lysosome in lipid metabolism. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27:833–850. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikonen E. Cellular cholesterol trafficking and compartmentalization. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:125–138. doi: 10.1038/nrm2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Sanz P., Orgaz L., Bueno-Gil G., Espadas I., Rodriguez-Traver E., Kulisevsky J. N370S-GBA1 mutation causes lysosomal cholesterol accumulation in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2017;32:1409–1422. doi: 10.1002/mds.27119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuzu O.F., Gowda R., Sharma A., Robertson G.P. Leelamine mediates cancer cell death through inhibition of intracellular cholesterol transport. Mol Cancer Therapeut. 2014;13:1690–1703. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baulies A., Ribas V., Nunez S., Torres S., Alarcon-Vila C., Martinez L. Lysosomal cholesterol accumulation sensitizes to acetaminophen hepatotoxicity by impairing mitophagy. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18017. doi: 10.1038/srep18017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barbero-Camps E., Roca-Agujetas V., Bartolessis I., de Dios C., Fernandez-Checa J.C., Mari M. Cholesterol impairs autophagy-mediated clearance of amyloid beta while promoting its secretion. Autophagy. 2018;14:1129–1154. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1438807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langemeyer L., Frohlich F., Ungermann C. Rab GTPase function in endosome and lysosome biogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:957–970. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei J., Zhang Y.Y., Luo J., Wang J.Q., Zhou Y.X., Miao H.H. The GARP complex is involved in intracellular cholesterol transport via targeting NPC2 to lysosomes. Cell Rep. 2017;19:2823–2835. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Millard E.E., Srivastava K., Traub L.M., Schaffer J.E., Ory D.S. Niemann-pick type C1 (NPC1) overexpression alters cellular cholesterol homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38445–38451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendrikx T., Walenbergh S.M., Hofker M.H., Shiri-Sverdlov R. Lysosomal cholesterol accumulation: driver on the road to inflammation during atherosclerosis and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Obes Rev. 2014;15:424–433. doi: 10.1111/obr.12159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barth B.M., Wang W., Toran P.T., Fox T.E., Annageldiyev C., Ondrasik R.M. Sphingolipid metabolism determines the therapeutic efficacy of nanoliposomal ceramide in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 2019;3:2598–2603. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018021295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang L., Yuan Y., Fu C., Xu X., Zhou J., Wang S. LZ-106, a novel analog of enoxacin, inducing apoptosis via activation of ROS-dependent DNA damage response in NSCLCs. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;95:155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez Molina D., Jafari R., Ignatushchenko M., Seki T., Larsson E.A., Dan C. Monitoring drug target engagement in cells and tissues using the cellular thermal shift assay. Science. 2013;341:84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1233606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang L., He Z., Yao J., Tan R., Zhu Y., Li Z. Corrigendum to "Regulation of AMPK-related glycolipid metabolism imbalances redox homeostasis and inhibits anchorage independent growth in human breast cancer cells" [Redox Biol. 17 (2018) 180-191] Redox Biol. 2020;28 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klionsky D.J., Abdalla F.C., Abeliovich H., Abraham R.T., Acevedo-Arozena A., Adeli K. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:445–544. doi: 10.4161/auto.19496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papadopoulos C., Kirchner P., Bug M., Grum D., Koerver L., Schulze N. VCP/p97 cooperates with YOD1, UBXD1 and PLAA to drive clearance of ruptured lysosomes by autophagy. EMBO J. 2017;36:135–150. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lloyd-Evans E., Platt F.M. Lysosomal Ca2+ homeostasis: role in pathogenesis of lysosomal storage diseases. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jia J., Bissa B., Brecht L., Allers L., Choi S.W., Gu Y. AMPK, a regulator of metabolism and autophagy, is activated by lysosomal damage via a novel galectin-directed ubiquitin signal transduction system. Mol Cell. 2020;77:951–969.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eskelinen E.L. Roles of LAMP-1 and LAMP-2 in lysosome biogenesis and autophagy. Mol Aspect Med. 2006;27:495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papadopoulos C., Meyer H. Detection and clearance of damaged lysosomes by the endo-lysosomal damage response and lysophagy. Curr Biol. 2017;27:R1330–R1341. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medina D.L., Ballabio A. Lysosomal calcium regulates autophagy. Autophagy. 2015;11:970–971. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1047130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medina D.L., Di Paola S., Peluso I., Armani A., De Stefani D., Venditti R. Lysosomal calcium signalling regulates autophagy through calcineurin and TFEB. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:288–299. doi: 10.1038/ncb3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu F., Liang Q., Abi-Mosleh L., Das A., de Brabander J.K., Goldstein J.L. Identification of NPC1 as the target of U18666A, an inhibitor of lysosomal cholesterol export and Ebola infection. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.12177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perera R.M., Stoykova S., Nicolay B.N., Ross K.N., Fitamant J., Boukhali M. Transcriptional control of autophagy-lysosome function drives pancreatic cancer metabolism. Nature. 2015;524:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nature14587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosesson Y., Mills G.B., Yarden Y. Derailed endocytosis: an emerging feature of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:835–850. doi: 10.1038/nrc2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haigler H.T., McKanna J.A., Cohen S. Rapid stimulation of pinocytosis in human carcinoma cells A-431 by epidermal growth factor. J Cell Biol. 1979;83:82–90. doi: 10.1083/jcb.83.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gomez-Sintes R., Ledesma M.D., Boya P. Lysosomal cell death mechanisms in aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;32:150–168. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dielschneider R.F., Henson E.S., Gibson S.B. Lysosomes as oxidative targets for cancer therapy. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:3749157. doi: 10.1155/2017/3749157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang X., Wang J., Li X., Wang D. Lysosomes contribute to radioresistance in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018;439:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dielschneider R.F., Eisenstat H., Mi S., Curtis J.M., Xiao W., Johnston J.B. Lysosomotropic agents selectively target chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells due to altered sphingolipid metabolism. Leukemia. 2016;30:1290–1300. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gotink K.J., Broxterman H.J., Labots M., de Haas R.R., Dekker H., Honeywell R.J. Lysosomal sequestration of sunitinib: a novel mechanism of drug resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7337–7346. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baquero P., Dawson A., Mukhopadhyay A., Kuntz E.M., Mitchell R., Olivares O. Targeting quiescent leukemic stem cells using second generation autophagy inhibitors. Leukemia. 2019;33:981–994. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0252-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Das S., Dielschneider R., Chanas-LaRue A., Johnston J.B., Gibson S.B. Antimalarial drugs trigger lysosome-mediated cell death in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells. Leuk Res. 2018;70:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen D., Wang X., Li X., Zhang X., Yao Z., Dibble S. Lipid storage disorders block lysosomal trafficking by inhibiting a TRP channel and lysosomal calcium release. Nat Commun. 2012;3:731. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lloyd-Evans E., Platt F.M. Lipids on trial: the search for the offending metabolite in Niemann-Pick type C disease. Traffic. 2010;11:419–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vanier M.T. Complex lipid trafficking in Niemann-Pick disease type C. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015;38:187–199. doi: 10.1007/s10545-014-9794-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trinh M.N., Lu F., Li X., Das A., Liang Q., de Brabander J.K. Triazoles inhibit cholesterol export from lysosomes by binding to NPC1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:89–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619571114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Domagala A., Fidyt K., Bobrowicz M., Stachura J., Szczygiel K., Firczuk M. Typical and atypical inducers of lysosomal cell death: a promising anticancer strategy. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:2256. doi: 10.3390/ijms19082256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.