Abstract

Obesity is a risk factor for the development of post-menopausal breast cancer. Breast white adipose tissue (WAT) inflammation, which is commonly found in women with excess body fat, is also associated with increased breast cancer risk. Both local and systemic effects are probably important for explaining the link between excess body fat, adipose inflammation and breast cancer. The first goal of this cross-sectional study of 196 women was to carry out transcriptome profiling to define the molecular changes that occur in the breast related to excess body fat and WAT inflammation. A second objective was to determine if commonly measured blood biomarkers of risk and prognosis reflect molecular changes in the breast. Breast WAT inflammation was assessed by immunohistochemistry. Bulk RNA-sequencing was carried out to assess gene expression in non-tumorous breast. Obesity and WAT inflammation were associated with a large number of differentially expressed genes and changes in multiple pathways linked to the development and progression of breast cancer. Altered pathways included inflammatory response, complement, KRAS signaling, tumor necrosis factor α signaling via NFkB, interleukin (IL)6-JAK-STAT3 signaling, epithelial mesenchymal transition, angiogenesis, interferon γ response and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling. Increased expression of several drug targets such as aromatase, TGF-β1, IDO-1 and PD-1 were observed. Levels of various blood biomarkers including high sensitivity C-reactive protein, IL6, leptin, adiponectin, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and insulin were altered and correlated with molecular changes in the breast. Collectively, this study helps to explain both the link between obesity and breast cancer and the utility of blood biomarkers for determining risk and prognosis.

Obesity and breast white adipose tissue inflammation are associated with changes in multiple pathways and processes linked to the pathogenesis of breast cancer. Blood biomarkers of breast cancer risk or progression correlate with molecular changes in the breast.

Introduction

The accumulation of excess adipose tissue is associated with an increased risk of post-menopausal hormone receptor-positive breast cancer (1–3). Obesity is also associated with an increased risk of breast cancer recurrence and reduced overall survival (4–6). Adipose tissue is biologically active secreting adipokines, cytokines and estrogens. In the obese, a variety of hormonal, metabolic and inflammatory changes occur that promote the pathogenesis of breast cancer (7,8).

A pathological hallmark of white adipose tissue (WAT) inflammation is the crown-like structure (CLS). CLSs are easily recognized in adipose tissue and reflect a dead or dying adipocyte surrounded by macrophages (9). Breast WAT inflammation, as defined by the presence of CLS, has been associated with both an increased risk of breast cancer and a worse clinical course in patients with breast cancer (10–12). Approximately, 90% of obese women have breast WAT inflammation (13). Importantly, breast WAT inflammation is also present in a smaller proportion of non-obese women including a subset with a normal body mass index (BMI) (14). Breast WAT inflammation is associated with inflamed adipose tissue at other sites such as abdominal subcutaneous fat (13). Both local and systemic effects are probably important in explaining the link between WAT inflammation and breast cancer. For example, breast WAT inflammation is associated with activation of nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) and elevated levels of aromatase, the rate-limiting enzyme for estrogen biosynthesis (15). Consistent with breast WAT inflammation being a sentinel for a diffuse low-grade inflammatory state in different fat depots, it is associated with changes in blood biomarkers that reflect both inflammation and altered metabolism (11). Elevated blood levels of high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), interleukin (IL)6, triglycerides and insulin have all been observed in women with breast WAT inflammation (11). Importantly, although blood biomarkers are used to assess the efficacy of interventions aimed at reducing the risk of breast cancer or preventing breast cancer recurrence in obese women, little is known about the molecular changes they reflect in the breast (16–18).

In this study, we had two main objectives. The first goal was to carry out transcriptome profiling on non-tumorous breast tissue to define the molecular changes that occur related to excess body fat and WAT inflammation. A second goal was to determine if commonly measured blood biomarkers reflect molecular changes in the breast that are believed to be important in the development or progression of breast cancer. Here we demonstrate that obesity and WAT inflammation are associated with a large number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and changes in multiple pathways linked to the pathogenesis of breast cancer. Moreover, we show that blood biomarkers previously linked to the pathogenesis of breast cancer correlate with numerous molecular changes in breast tissue.

Materials and methods

Study population and biospecimen collection

The Institutional Review Boards of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (IRB 10-040) and Weill Cornell Medicine (IRB 1004010984-01) approved the collection of non-tumorous breast tissue and blood under a biospecimen acquisition protocol. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations. In total, 196 patients underwent mastectomy to reduce the risk of breast cancer or for treatment of breast cancer. Clinical data (age, race and menopause status) were extracted from the electronic medical record by research staff and physicians (Supplementary Table S1, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Height and weight were recorded prior to surgery and used to calculate BMI. Standard definitions were used to categorize BMI as under- or normal weight (BMI < 25), overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9) or obese (BMI ≥ 30). Menopause status was described as either pre-menopausal or post-menopausal based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria (19). All data were reviewed for accuracy independently by research staff and a physician.

On the day of mastectomy, paraffin blocks and snap frozen samples were prepared from breast WAT not involved by tumor. If a tumor was present, samples were taken from an uninvolved quadrant of the breast. Frozen samples were stored in RNAlater (Ambion). On the day of surgery, a 30 ml fasting blood sample was obtained preoperatively. Centrifugation was used to separate blood into serum and plasma within 3 h of collection and stored at −80°C.

WAT inflammation

Histologic assessment was used to determine the presence or absence of breast WAT inflammation (11,13,15). White adipose inflammation was defined by the presence or absence of CLSs, which are composed of a dead or dying adipocyte surrounded by CD68-positive macrophages (9,20). Breast adipose tissue from the mastectomy specimen was formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded. Five formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded blocks were prepared and one section per formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded block (5 μm thick and ~2 cm in diameter) was generated such that five sections were stained for CD68, a macrophage marker (mouse monoclonal KP1 antibody; Dako; dilution 1:4000). Immunostained tissue sections were examined by the study pathologist (D.D.G.) using light microscopy to detect the presence or absence of CLS.

Blood assays

Plasma levels of glucose (BioAssay Systems), hsCRP, leptin, adiponectin, IL6 (R&D Systems) and insulin (Mercodia) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Serum levels of triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol were determined in the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center clinical chemistry lab.

Statistics

Patient clinicopathologic variables and blood biomarker data were summarized as median and range for continuous variables and counts and proportions for categorical variables. Expression levels of genes of interest and single-sample gene set enrichment analysis scores of gene sets of interest were summarized using box plots. Differences in continuous variables across study groups were evaluated using Kruskal–Wallis test. Dunn’s test was used for post hoc pairwise comparisons and P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Correlation between two continuous variables was evaluated using the Spearman’s method. Robust regression analyses were used to examine the association between the single-sample gene set enrichment analysis scores of gene sets of interest and menopausal status while controlling for BMI. All statistical analyses were carried out using the statistical computing software R. All P-values were two-sided when applicable and P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Methods for the computational analysis are included in the Supplementary materials, available at Carcinogenesis Online.

Results

Excess body fat and WAT inflammation are determinants of the transcriptome in the breast

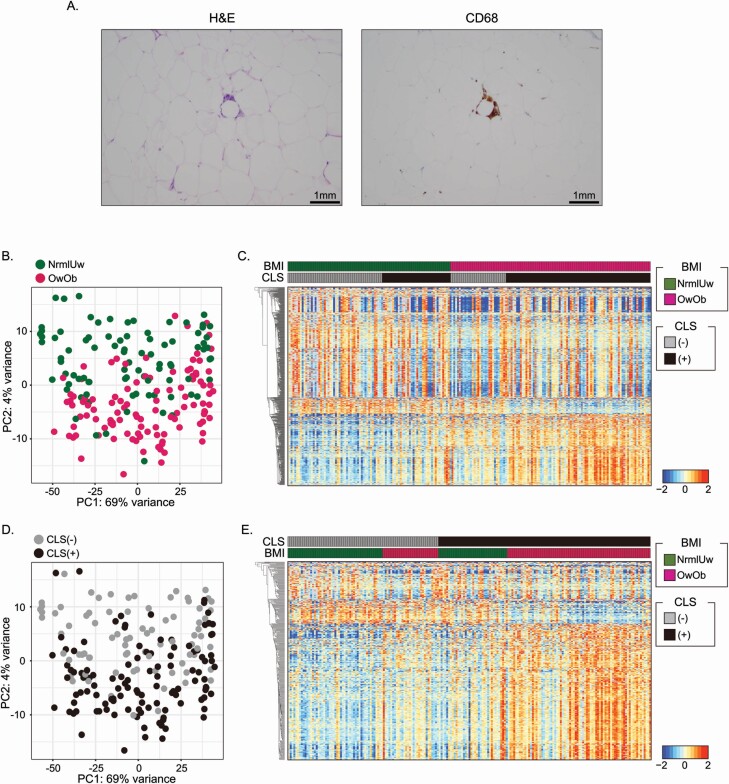

Breast tissue with RNA of suitable quality for analysis was available from 196 women. The inflammatory status of breast adipose tissue was determined by the presence or absence of CLS (Figure 1A). As shown in Supplementary Table S1, available at Carcinogenesis Online, the samples were divided into four groups based on BMI and CLS status to investigate the impact of excess body fat and WAT inflammation on the non-tumorous breast transcriptome: 51 of the women were NormalUnderweight (NrmlUw).CLS(−), 30 were OverweightObese (OwOb).CLS(−), 37 were NrmlUw.CLS(+) and 78 were OwOb.CLS(+). Breast tissue was obtained from women who either did or did not have tumors. When a tumor was present, to minimize the possibility of the tumor influencing the transcriptome of non-tumorous tissue, tissue was obtained from an uninvolved quadrant of the breast. This tissue was subjected to RNA-sequencing. As shown in Supplementary Figure S1A, available at Carcinogenesis Online, principal component analysis (PCA) of tissue from women with or without tumors indicated that there was a homogeneous distribution of cases. The box plots using PC1 and PC2 values also indicated that there was no significant difference in the transcriptome profiles of women with versus without tumor (Supplementary Figure S1B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). This result suggested that the presence of tumor did not have notable impact on the transcriptome in the tissue that was assessed. Next the effects of excess adipose tissue and WAT inflammation on the transcriptome were evaluated separately. The PCA indicated that OwOb cases were clearly separated from NrmlUw cases (Figure 1B). A total of 346 up-regulated and 650 down-regulated DEGs (P.adj < 0.05, |Log2 FoldChange| > 0.6) were found in OwOb individuals when compared with NrmlUw individuals using DESeq2 (Figure 1C and Supplementary Table S2, available at Carcinogenesis Online). To evaluate the effects of WAT inflammation, CLS(+) and CLS(−) cases were compared. The PCA plot also revealed a clear separation of the two groups (Figure 1D). A total of 337 up-regulated and 166 down-regulated DEGs (P.adj < 0.05 and (2) |Log2 FoldChange| > 0.6) were detected in CLS(+) versus CLS(−) cases (Figure 1E and Supplementary Table S3, available at Carcinogenesis Online). To determine the extent of overlap between the effects of excess body fat and WAT inflammation on gene expression, we compared up- and down-regulated genes (Supplementary Figure S2A and B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). The Venn diagram indicates that there was considerable overlap. However, there were numerous non-overlapping DEGs suggesting that excess adiposity and WAT inflammation are also associated with independent biological effects.

Figure 1.

Impact of obesity and inflammation on transcriptome of non-tumorous breast tissue. (A) Image of CLS. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; left) and anti-CD68 immunostaining (right) showing CLS of the breast. (B) PCA plot showing transcriptomic difference between Normal/Underweight (NrmlUw) individuals versus Overweight/Obese (OwOb) individuals. (C) Heatmap of DEGs based on BMI category. (D) PCA plot showing transcriptomic differences between CLS(+) and CLS(−) cases. (E) Heatmap of DEGs based on CLS status. In (B) and (D), PCA was plotted using 500 most variable genes from the whole transcriptome.

The post-menopausal state is associated with weight gain, breast WAT inflammation and an increased risk of breast cancer (13). Hence, we postulated that there would be overlap between the DEGs associated with excess body fat, WAT inflammation and menopause. First, we compared post-menopausal versus pre-menopausal cases to determine the number of DEGs. A total of 93 up-regulated and 208 down-regulated DEGs were detected (P.adj < 0.05 and (2) |Log2 FoldChange| > 0.6) (Supplementary Table S4, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Next, we evaluated potential overlap between changes in gene expression associated with excess body fat, WAT inflammation and menopause. In total, 67 of the up-regulated genes found in the post-menopausal versus pre-menopausal state overlapped with the effects of elevated BMI; 165 of the down-regulated genes found in the post-menopausal versus pre-menopausal state overlapped with the effects of elevated BMI (Supplementary Figure S2A and B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). In total, 68 of the up-regulated genes found in the post-menopausal versus pre-menopausal state overlapped with the effects of WAT inflammation; 49 of the down-regulated genes found in the post-menopausal versus pre-menopausal state overlapped with the effects of WAT inflammation (Supplementary Figure S2A and B, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Altered biological pathways and functions in association with excess body fat and WAT inflammation

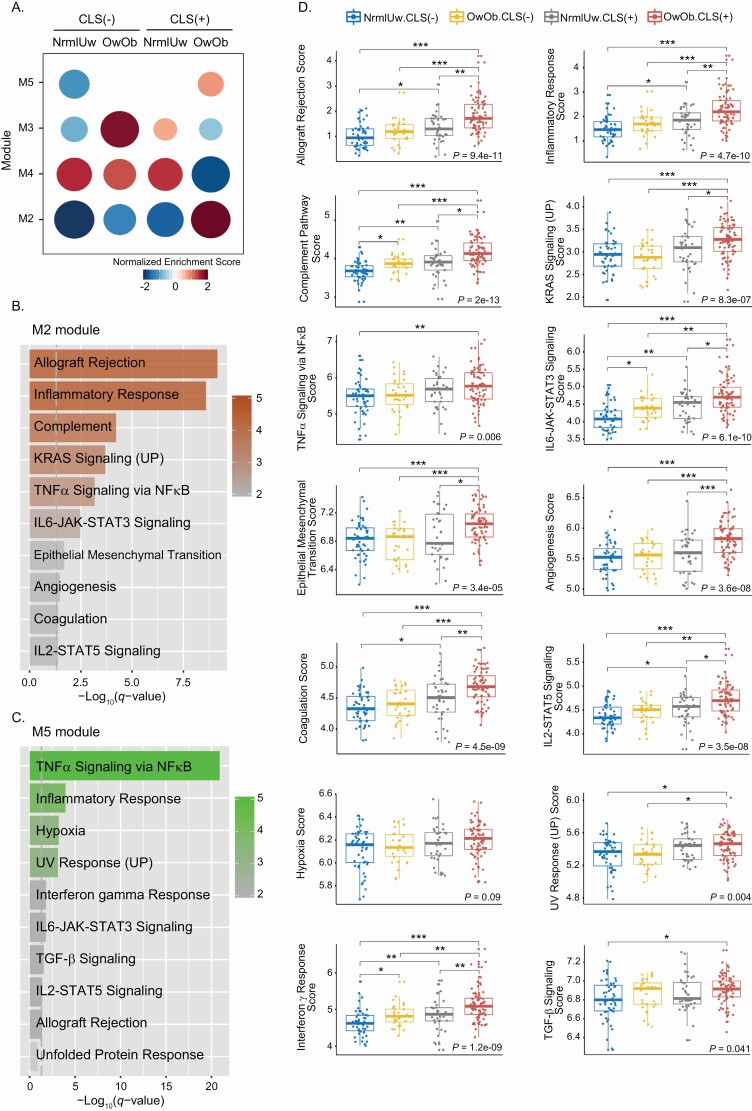

To determine whether excess body fat and WAT inflammation were associated with altered biological functions and pathways, modular gene co-expression analysis was utilized. Modules were created based on co-expressed genes within the four groups: NrmlUw.CLS(−), OwOb.CLS(−), NrmlUw.CLS(+) and OwOb.CLS(+). Co-expression gene modules are generated with genes whose expression is highly correlated using CEMiTool. The modules are then used to investigate the functional architecture of genes in association with sample phenotypes. In Figure 2A, module activities are shown in the enrichment plot across the four groups. M2 and M5 modules were up-regulated in the OwOb.CLS(+) group compared with the other three groups; the elevation was greater in M2 than M5. The genes that define all modules are listed in Supplementary Table S5, available at Carcinogenesis Online. In contrast to the M2 and M5 modules, the M3 module did not increase with obesity and WAT inflammation. M4 was down-regulated in the OwOb.CLS(+) group but pathway enrichment was not observed. Lastly, M1 did not show significant differences among the four groups and therefore was excluded from the analysis. The M2 and M5 modules were subjected to further analysis where we attempted to define which biological pathways were altered with excess body fat and WAT inflammation.

Figure 2.

Gene co-expression analysis of non-tumorous breast tissue from women varying in BMI and inflammation (CLS) status. (A) Up- or down-regulated modules were generated. Module activity is displayed as an enrichment plot. M2 and M5 modules show increased activity in the OwOb.CLS(+) group versus the other three groups. M4 shows decreased activity in the OwOb.CLS(+) group. (B) Pathway enrichment analysis of M2 module. Gray dotted line represents FDR q-value < 0.05. All enriched pathways are significant. (C) Pathway enrichment analysis of M5 module. Gray dotted line represents FDR q-value < 0.05. All pathways except for unfolded protein response are statistically significant. (D) Numerous pathways were altered with obesity and WAT inflammation. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to determine the difference among four groups. Dunn’s test was used for each pairwise comparison and significant differences are indicated. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Pathway enrichment analysis of the M2 and M5 modules indicated that expression of numerous pathways was increased in the OwOb.CLS(+) group compared with the other three groups. The pathways included allograft rejection (P = 9.4e-11), inflammatory response (P = 4.7e-10), complement (P = 2e-13), KRAS signaling (P = 8.3e-07), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α signaling via NF-κB (P = 0.006), IL6-JAK-STAT3 signaling (P = 6.1e-10), epithelial mesenchymal transition (P = 3.4e-05), angiogenesis (P = 3.6e-08), coagulation (P = 4.5e-09), IL2-STAT5 signaling (P = 3.5e-08), hypoxia (P = 0.09), UV response (P = 0.004), interferon γ response (P = 1.2e-09) and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling (P = 0.041) (Figure 2B–D). Because menopause is associated with excess body fat, WAT inflammation and related changes in gene expression, pathway enrichment analysis was performed (Supplementary Table S6, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Allograft rejection (P = 2.08e-08), inflammation response (P = 2.08e-08), TNFα signaling via NF-κB (P = 4.08e-07), complement (P = 1.17e-03), KRAS signaling (DN; P = 1.17e-03) and coagulation (P = 3.95e-03) pathways were enriched with up-regulated DEGs (Supplementary Table S6, available at Carcinogenesis Online). KRAS signaling (UP; P = 8.17e-05) and estrogen response (late; P = 6.0e-04) pathways were enriched with down-regulated DEGs. These findings are very similar to the pathway changes that were observed in samples from OwOb.CLS(+) versus the other three groups of women (Figure 2B–D), which fits with menopause being associated with both weight gain and breast white adipose inflammation.

To evaluate the relationship between excess body fat and breast WAT inflammation more closely, pathway scores based on single-sample gene set enrichment analysis were generated and compared for the four groups: NrmlUw.CLS(−), OwOb.CLS(−), NrmlUw.CLS(+) and OwOb.CLS(+). The highest scores for each pathway were observed for the OwOb.CLS(+) group (Figure 2D). As mentioned above, statistically significant differences were observed for all pathways with the exception of hypoxia score. Additionally, independent effects of excess body fat and WAT inflammation were found for multiple pathways. For example, if one focuses on the inflammatory response, the score was higher in the CLS(+) versus CLS(−) groups regardless of BMI. Furthermore, the inflammatory response score was higher in the those with an elevated BMI. This increase is observed when comparing the OwOb.CLS(+) group versus the NrmlUw.CLS(+) group. Similar inductive effects of excess body fat and WAT inflammation were observed for other pathways including allograft rejection, IL6-JAK-STAT3 signaling, IL2-STAT5 signaling and the interferon γ response. Because obesity is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer in the post-menopausal but not the pre-menopausal state, we next determined if the magnitude of increase in pathways in the M2 and M5 modules differed in post-menopausal versus pre-menopausal women. When controlling for BMI, 8 of 10 pathways in the M2 and M5 modules were increased in association with the post-menopausal versus pre-menopausal state in OwOb.CLS(+) women (Supplementary Table S7, available at Carcinogenesis Online). This suggests that the biological consequences associated with inflammation are greater following menopause, a result that is consistent with the known pro-inflammatory state of the post-menopausal state.

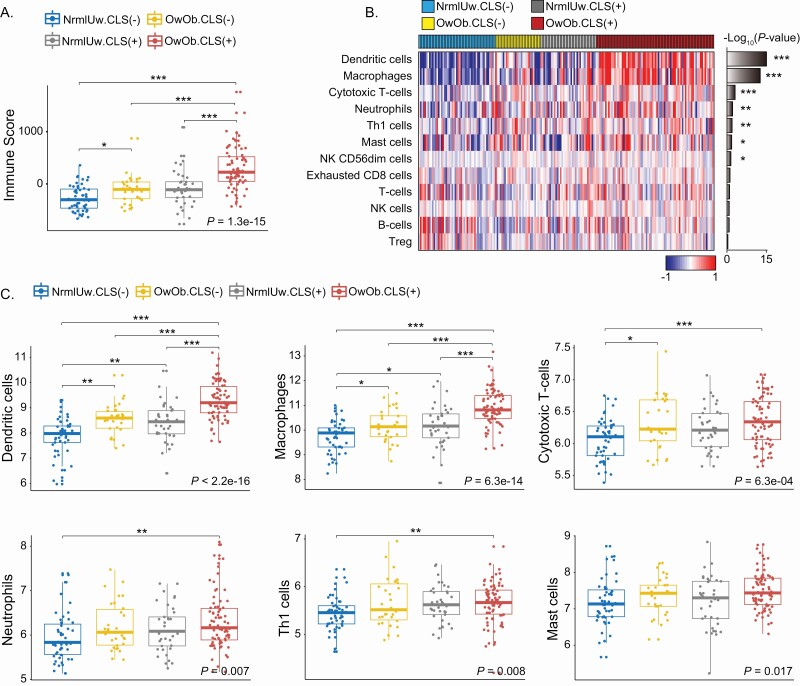

Immune cell infiltration profiling and evaluation of immune function-related genes

Because biological processes related to the immune system were increased in the OwOb.CLS(+) group versus the other three groups, we speculated that there were probably associated differences in the immune cell infiltrates. The overall immune cell change was investigated by monitoring the immune score using Estimate (Figure 3A). There was evidence of a significant increase in immune score in association with excess body fat and WAT inflammation. Next, a gene signature strategy was utilized to evaluate whether specific immune cell populations were altered in association with excess body fat and WAT inflammation. Consistent with macrophages being present in CLS, our analysis predicted a significant increase in macrophages in the OwOb.CLS(+) group (Figure 3B). Notably, excess body fat and WAT inflammation were also associated with increases in dendritic cells, cytotoxic T cells, neutrophils, Th1 cells and mast cells (Figure 3B). A more detailed description of differences in the immune cell populations based on the four groups is shown in Figure 3C. To validate these findings, a second computational method, i.e. xCell was used and most of the inferred immune cell changes were confirmed (Supplementary Figure S3, available at Carcinogenesis Online). More specifically, increased dendritic cells, macrophages, neutrophils and mast cells were predicted in the OwOb.CLS(+) group. Because of the importance of macrophages in both adipose and tumor biology, we next determined the effects of excess body fat and WAT inflammation on the expression of several genes (CCL2, CSF1R, IL6, C3, C3AR1 and C5AR1) that are important in macrophage biology (Supplementary Figure S4, available at Carcinogenesis Online). CCL2 is a chemokine produced by adipocytes that is important for monocytes to be recruited from blood into fat contributing to the formation of CLS (21,22). CSF1R is a receptor for colony stimulating factor 1, a cytokine that controls the production, differentiation and function of macrophages (23). IL6 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine produced by numerous cells in adipose tissue that can also influence adipose tissue macrophage accumulation (24). C3 is upstream of the anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a that bind to the C3a and C5a receptors. Activation of these receptors attracts inflammatory cells including monocytes into adipose tissue contributing to CLS formation (25). Consistent with the increased macrophage population found in breast tissue of women with excess body fat and WAT inflammation, levels of CCL2, CSF1R, IL6, C3, C3AR1 and C5AR1 were highest in OwOb.CLS(+) group (Supplementary Figure S4, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Figure 3.

Differences in immune cell populations in non-tumorous breast tissue from women who varied in BMI and white adipose inflammation status. (A) Immune score describes immune cell infiltration in non-tumorous breast tissue from four groups of women varying in BMI and inflammation (CLS) status. (B) Heatmap illustrating 12 different types of immune cells in non-tumorous breast tissue from four groups of women varying in BMI and inflammation (CLS) status. (C) Illustration of immune cell differences in non-tumorous breast tissue from four groups of women varying in BMI and inflammation status. For pairwise comparisons, Dunn’s test was used and significant differences are indicated. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

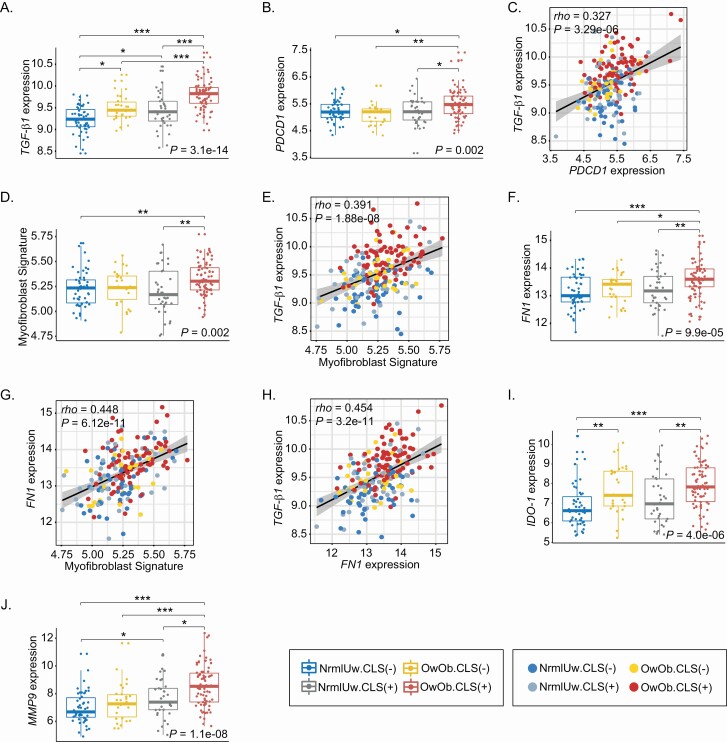

Obesity and breast WAT inflammation were also associated with increased TGF-β signaling (Figure 2C and D). Because TGF-β signaling has multiple protumorigenic and immunosuppressive effects, we compared TGF-β1 levels in the four groups. Levels of TGF-β1 were highest in the OwOb.CLS(+) group compared with the other three groups (Figure 4A). In fact, levels increased in association with both excess body fat and WAT inflammation. TGF-β1 is a known inducer of PDCD-1 (PD-1), the immune checkpoint (26). Like TGF-β1, levels of PDCD-1 were increased in the OwOb.CLS(+) group (Figure 4B) and correlated with TGF-β1 levels (Figure 4C). TGF-β can also stimulate the differentiation of adipose stromal cells into myofibroblasts leading, in turn, to an increase in extracellular matrix. Changes in extracellular matrix can have a variety of protumorigenic effects including altered mechanosignal transduction in tumor cells and suppression of local immune responses (27,28). Interestingly, the proportion of myofibroblasts was greatest in the OwOb.CLS(+) group and correlated with levels of TGF-β1 (Figure 4D and E). Myofibroblasts produce fibronectin, a component of the extracellular matrix. Levels of fibronectin were highest in the OwOb.CLS(+) group (Figure 4F) and correlated with both the proportion of myofibroblasts and TGF-β1 expression (Figure 4G and H). In addition to TGF-β1 and PDCD-1, IDO-1, which plays a critical role in the metabolism of tryptophan to kynurenine, an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist, is linked to immunosuppression (29). Like TGF-β1 and PDCD-1, levels of IDO-1 were highest in the OwOb.CLS(+) group (Figure 4I). Obesity is associated with remodeling of adipose tissue. In addition to increased production of extracellular matrix driven, in part, by activation of TGF-β signaling, there is probably increased turnover. To this end, we evaluated levels of MMP9, a matrix metalloproteinase that has been reported to be increased in association with obesity albeit we are not aware of previous studies of the breast (30). Here too, levels of MMP9 were highest in the OwOB.CLS(+) group (Figure 4J).

Figure 4.

Elevated BMI and breast white adipose inflammation are associated with increased expression of genes linked to immunosuppression. (A) Expression level of TGF-β1. (B) Expression level of PDCD1. (C) Correlation analysis of TGF-β1 and PDCD1. (D) Myofibroblast signature score. (E) Correlation analysis of TGF-β1 and myofibroblast signature score. (F) Expression level of FN1. (G) Correlation analysis of FN1 and myofibroblast signature score. (H) Correlation analysis of TGF-β1 and FN1. (I) Expression level of IDO-1. (J) Expression level of MMP9. For pairwise comparisons, Dunn’s test was used and significant differences are indicated. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Levels of aromatase, EGFL6 and the proportion of preadipocytes are elevated in association with excess body fat and WAT inflammation

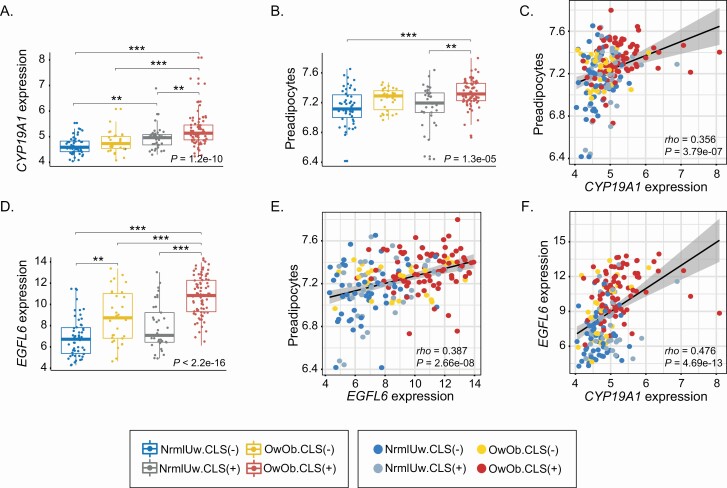

Because obesity is a risk factor for the development of estrogen-driven breast cancers in post-menopausal women, there is significant interest in the relationship between obesity, inflammation and aromatase, the rate-limiting enzyme for estrogen biosynthesis. Previously, we showed that aromatase levels are elevated in association with increased BMI and WAT inflammation but the underlying mechanism is incompletely understood (15). Levels of aromatase are markedly increased in preadipocytes compared with adipocytes raising the possibility that the elevation of aromatase is due, at least in part, to an increased population of preadipocytes (31). Consistent with prior evidence, the level of CYP19A1 that encodes aromatase was highest in the OwOb.CLS(+) group (Figure 5A). Based on its gene expression signature, the proportion of preadipocytes was estimated and found to be highest in the same group (Figure 5B). Levels of CYP19A1 expression and the proportion of preadipocytes correlated (Figure 5C) suggesting a possible causal relationship. An increase in the proportion of preadipocytes could reflect increased cell proliferation. EGFL6 has been reported to be increased in obesity, secreted by adipocytes and capable of stimulating the proliferation of preadipocytes (32). Given this background, we determined whether EGFL6 levels were affected by excess body fat and WAT inflammation. As shown in Figure 5D–F, levels of EGFL6 were highest in the OwOb.CLS(+) group and correlated with the proportion of both preadipocytes and levels of CYP19A1.

Figure 5.

Elevated BMI and white adipose inflammation are associated with an increased proportion of preadipocytes and elevated levels of CYP19A1 and EGFL6. Non-tumorous breast tissue from four groups of women varying in BMI and inflammation (CLS) status was analyzed. (A). Expression level of CYP19A1 (aromatase). (B) Proportion of preadipocytes. (C) Correlation analysis of CYP19A1 expression and proportion of preadipocytes. (D) Expression level of EGFL6. (E) Correlation analysis of EGFL6 expression and proportion of preadipocytes. (F) Correlation analysis of EGFL6 expression and expression level of CYP19A1. For pairwise comparisons, Dunn’s test was used and significant differences are indicated. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Blood biomarkers correlate with both gene expression and pathways that are altered in breast tissue in association with excess body fat and WAT inflammation

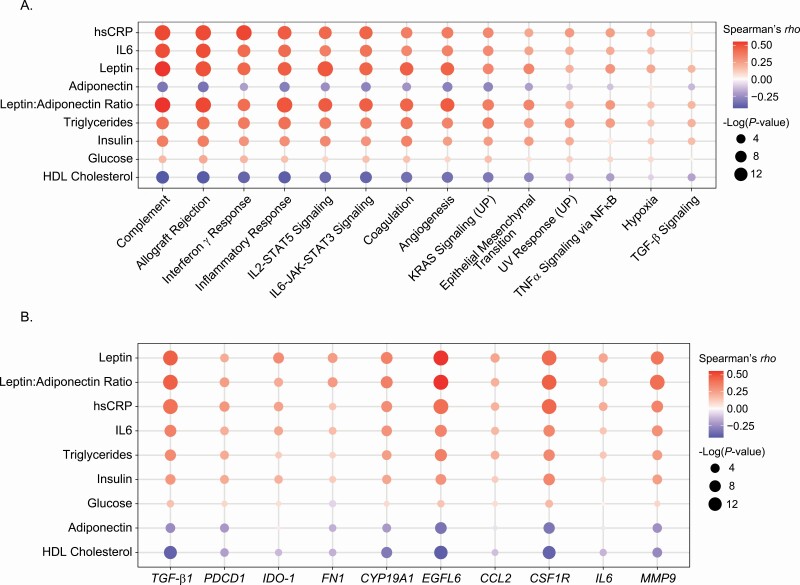

Blood biomarkers of inflammation (hsCRP, IL6), adiposity (leptin, adiponectin) and metabolism (insulin, glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol) were measured (Supplementary Table S8, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Levels of hsCRP, IL6, leptin and triglycerides increased in association with excess body fat and WAT inflammation (Ps < 0.001). In contrast, blood levels of adiponectin and HDL cholesterol were lowest in the group with excess body fat and WAT inflammation (Ps < 0.001). Although several of these blood biomarkers have been linked to the pathogenesis of breast cancer and are often measured in studies focused on the connection between obesity and breast cancer (33–35), very little is known about what they reflect in the breast itself. Because we showed that obesity and WAT inflammation were associated with changes in numerous hallmark pathways that are linked to cancer (Figure 2B and C), we next determined whether the commonly measured blood biomarkers correlated with the hallmark pathways. As shown in Figure 6A and Supplementary Table S9, available at Carcinogenesis Online, the blood biomarkers correlated either positively or negatively with multiple hallmark pathways including complement, epithelial mesenchymal transition, allograft rejection, inflammatory response, TNFα signaling via NF-κB, IL6-JAK-STAT3 signaling, IL2-STAT5 signaling, angiogenesis, hypoxia, Interferon γ response and TGF-β signaling. The direction and strengths of the correlations varied between levels of individual blood biomarkers and specific pathways. For example, levels of hsCRP, IL6, leptin, triglycerides, insulin and glucose positively correlated with the inflammatory response score (Supplementary Figure S5 and Supplementary Table S9, available at Carcinogenesis Online). In contrast, blood levels of adiponectin and HDL cholesterol negatively correlated with the inflammatory response score (Supplementary Figure S5 and Supplementary Table S9, available at Carcinogenesis Online). As mentioned, the degree of correlation also varied for different biomarkers. The fact that levels of biomarkers including hsCRP, IL6, leptin and triglycerides moderately correlated with the inflammatory response score in breast tissue, whereas only a weak correlation existed for glucose illustrates this point.

Figure 6.

Blood biomarkers correlate with biological pathways and gene expression in non-tumorous breast tissue. (A) Heatmap describing correlation between blood biomarker measurements and pathways that are altered in association with elevated BMI and adipose inflammation. (B) Heatmap illustrating correlation between blood biomarker measurements and the expression of individual genes.

We also determined whether blood biomarkers of inflammation and metabolism (hsCRP, IL6, leptin, adiponectin, triglycerides, insulin, glucose and HDL cholesterol) reflected the expression of individual genes linked to the pathogenesis of disease. Several of the proteins encoded by these genes are well-known drug targets. To this end, we focused our analyses on genes that were already demonstrated to be affected by excess body fat or WAT inflammation: TGF-β1, PDCD-1, IDO-1, FN1, CYP19A1, EGFL6, CCL2, CSF1R, IL6 and MMP9 (Figure 6B). Among these genes, levels of TGF-β1, EGFL6, CSF1R and MMP9 correlated most strongly with blood marker measurements (Figure 6B and Supplementary Table S10, available at Carcinogenesis Online). For each of these four genes, the strongest positive correlations were observed for leptin and hsCRP. Negative correlations were found for adiponectin such that there was a positive correlation for the leptin:adiponectin ratio. Notably, levels of CYP19A1, PDCD-1, IDO-1, FN1, CCL2 and IL6 also correlated with numerous blood biomarkers but less strongly than for TGF-β1, EGFL6, CSF1R and MMP9. As shown in Supplementary Table S10, available at Carcinogenesis Online, the majority of these correlations between blood biomarkers and the expression of specific genes in the breast were statistically significant.

Discussion

In this study, we found that both excess body fat and WAT inflammation were associated with altered expression of a large number of genes in breast tissue. Additionally, we found activation or increases in numerous pathways that have been linked to the development or progression of cancer including inflammatory response, complement, TGF-β, IL6 and TNFα signaling, epithelial mesenchymal transition and interferon γ response. Many of the same changes in gene expression and pathway alterations were found in the post-menopausal state consistent with menopause being associated with weight gain and WAT inflammation. Remarkably, blood biomarkers linked to the pathogenesis of breast cancer that change with obesity and WAT inflammation correlated with molecular changes in the breast.

These findings that help to explain the link between obesity and breast cancer need to be considered in the context of two previous studies that investigated the relationship between obesity and gene expression in the breast. Similar to our findings, a microarray study utilized tissue from 74 reduction mammoplasty specimens and demonstrated that obesity was associated with a large number of DEGs including enrichment for a pathway involving IL6, consistent with a pro-inflammatory state and increased macrophage content (36). Because women undergoing reduction mammoplasties are commonly pre-menopausal and often obese, this study only included samples from 16 normal BMI women most of whom were young, which was a limitation. In the second study, which focused exclusively on post-menopausal women, elevated BMI was not associated with a single DEG (37). This result is very different from our findings or the results of the study carried out using reduction mammoplasty specimens. Nonetheless, consistent with our findings, gene set enrichment analysis of one of the two cohorts (Polish Breast Cancer Study) that was analyzed indicated that higher BMI was associated with epithelial mesenchymal transition, TNFα signaling via NF-κB, TGF-β signaling, allograft rejection, complement and activated inflammation pathways including IL6 and interferon γ response. A significant limitation of this second study was the use of RNA isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples for microarray analysis. In contrast to these two prior studies, we carried out RNA-sequencing using frozen breast tissue from a large number of women varying in menopausal status who had either excess body fat (overweight, obese) or were normal sized. The fact that both prior studies suggested that obesity was associated with a pro-inflammatory state is consistent with our findings and important given the well-known link between chronic inflammation and the development and progression of cancer (38,39). The post-menopausal state is known to be associated with inflammation and an elevated risk of breast cancer in the obese (40). Consistent with these prior findings, we found that numerous pathways implicated in carcinogenesis were increased or activated in OwOb inflamed post-menopausal versus pre-menopausal women. These results fit with a reduction in levels of 17β-estradiol, which possesses anti-inflammatory effects or potentially the recently discovered pro-inflammatory effects of estrone, which is produced in the post-menopausal state (41). Because excess body fat was associated with a pro-inflammatory state, a deconvolution approach was utilized to estimate the immune cell profile in breast tissue. Interestingly, we found increased proportions of various cell types including dendritic cells, macrophages, neutrophils, cytotoxic T cells, Th1 cells and mast cells in the breast tissue of women who had excess body fat and evidence of WAT inflammation. The increase in macrophages was confirmed by immunohistochemical measurements of CD68, a macrophage marker. Changes in the immune cell infiltrate can potentially contribute to the development or progression of breast cancer and warrant further investigation.

In addition to potential changes in immune cells in the breast, obesity and WAT inflammation were associated with other immunologic effects. Activation of TGF-β signaling was found. TGF-β is known to have multiple immunosuppressive effects including induction of PDCD-1 (PD-1), an immune checkpoint (26). Although levels of TGF-β1 increase in association with obesity, to our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that levels of TGF-β1 are increased in the breast in association with excess body fat (42). It also is notable that levels of PDCD-1 increased in association with excess body fat and WAT inflammation. The fact that a correlation was found between TGF-β1 and PDCD-1 raises the possibility of causality. Further studies are warranted to determine the cellular sources of both TGF-β1 and PDCD-1. TGF-β1 stimulates the differentiation of preadipocytes into myofibroblasts that produce extracellular matrix components including fibronectin. Increases in extracellular matrix can block T cells from gaining entry into tumor tissue (28). Changes in matrix stiffness can also impact cell signaling (27). It is of interest, therefore, that we observed an increase in the proportion of myofibroblasts and fibronectin levels in the breast tissue of OwOb.CLS(+) women that correlated with TGF-β1 expression. IDO-1 is involved in the conversion of tryptophan to kynurenine, an agonist of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, that modifies T cell function (29). Although IDO-1 levels have been reported to be elevated in obesity (43), to our knowledge this is the first evidence of elevated expression in the human breast. Taken together, these findings suggest that women with breast cancer and excess body fat and WAT inflammation could potentially benefit from therapies targeting TGF-β1, PDCD-1 or IDO-1.

Elevated aromatase in association with excess body fat and WAT inflammation is believed to help explain the increased risk of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer in obese post-menopausal women (15). A variety of pro-inflammatory molecules stimulate CYP19A1 transcription (44,45). However, levels of aromatase are also known to be markedly increased in preadipocytes compared with adipocytes (31). Here we demonstrate that levels of CYP19A1 correlate with the proportion of preadipocytes raising the distinct possibility that the increased levels of CYP19A1 found in the context of excess body fat and WAT inflammation reflect the presence of more preadipocytes. An increased population of preadipocytes could occur due to increased proliferation, reduced differentiation to adipocytes or both. It is possible, for example, that elevated TGF-β and TNFα signaling that are both known to suppress the differentiation of preadipocytes into adipocytes contributed to the increased proportion of preadipocytes (46,47). Alternatively, EGFL6, a protein secreted by adipocytes and known to stimulate the proliferation of preadipocytes could be involved (32). To this end, we observed increased EGFL6 levels, which correlated with both the proportion of preadipocytes and CYP19A1 levels. Antibody-based therapies targeting EGFL6 possess anticancer activity and might be useful in the management of breast cancers arising in the obese (48).

Finally, blood biomarkers were evaluated. Blood biomarkers have been associated with both the risk of breast cancer and prognosis (34,35,49). Additionally, blood biomarkers are used to monitor the efficacy of interventions that aim to reduce the risk of breast cancer in the obese (16–18). A major gap in our knowledge is defining the relationship between blood biomarkers and molecular changes in the breast. Here we demonstrate for the first time that easily quantified blood biomarkers correlate with both multiple biological pathways that are altered in association with excess body fat and WAT inflammation and the expression of individual genes, e.g. TGF-β1 and CYP19A1 that are known drug targets. At a minimum, our data provide mechanistic insights into why blood biomarkers correlate with breast cancer risk and prognosis. Whether quantifying blood biomarkers can help inform therapeutic decisions warrants additional consideration. New technology has been developed that can quantify at least five thousand proteins in blood (50). Based on our findings with a limited number of blood biomarkers, it would be worthwhile to determine which other proteins correlate with molecular changes in the breast. Additionally, other types of blood biomarkers, e.g. lipids may inform on gene expression and should be evaluated. Perhaps a combination of blood biomarkers will be more powerful than any single biomarker in predicting alterations in specific genes or pathways linked to the pathogenesis of breast cancer. Certainly, our findings strengthen the rationale for future efforts to discover new blood biomarker panels that will inform on risk and prognosis.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CLS

crown-like structure

- DEG

differentially expressed gene

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- hsCRP

high sensitivity C-reactive protein

- IL

interleukin

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-kappaB

- PCA

principal component analysis

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- WAT

white adipose tissue

Funding

National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (U54CA210184-01 to A.J.D.); Breast Cancer Research Foundation (to N.M.I. and A.J.D.); ICONIIC seed grant (to A.J.D.); Botwinick-Wolfensohn Foundation (in memory of Mr and Mrs Benjamin Botwinick to A.J.D.); Myrna and Bernard Posner (to N.M.I.); Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748).

Conflict of Interest Statement: Dr Iyengar receives consulting fees from Novartis and Seattle Genetics. Dr Morrow receives consulting fees from Genomic Health.

Data availability

All RNA-sequencing data have been deposited at the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA), which is hosted by the EBI and the CRG, under accession number EGAS00001004665.

References

- 1. Huang, Z., et al. (1997) Dual effects of weight and weight gain on breast cancer risk. JAMA, 278, 1407–1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Renehan, A.G., et al. (2008) Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet, 371, 569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lauby-Secretan, B., et al. ; International Agency for Research on Cancer Handbook Working Group. (2016) Body fatness and cancer—viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N. Engl. J. Med., 375, 794–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Calle, E.E., et al. (2003) Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N. Engl. J. Med., 348, 1625–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ewertz, M., et al. (2011) Effect of obesity on prognosis after early-stage breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol., 29, 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sparano, J.A., et al. (2012) Obesity at diagnosis is associated with inferior outcomes in hormone receptor-positive operable breast cancer. Cancer, 118, 5937–5946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hursting, S.D., et al. (2012) Obesity, energy balance, and cancer: new opportunities for prevention. Cancer Prev. Res., 5, 1260–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang, X., et al. (2013) Postmenopausal plasma sex hormone levels and breast cancer risk over 20 years of follow-up. Breast Cancer Res. Treat., 137, 883–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cinti, S., et al. (2005) Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J. Lipid Res., 46, 2347–2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carter, J.M., et al. (2018) Macrophagic “Crown-like Structures” are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer in benign breast disease. Cancer Prev. Res., 11, 113–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iyengar, N.M., et al. (2016) Systemic correlates of white adipose tissue inflammation in early-stage breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res., 22, 2283–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koru-Sengul, T., et al. (2016) Breast cancers from black women exhibit higher numbers of immunosuppressive macrophages with proliferative activity and of crown-like structures associated with lower survival compared to non-black Latinas and Caucasians. Breast Cancer Res. Treat., 158, 113–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iyengar, N.M., et al. (2015) Menopause is a determinant of breast adipose inflammation. Cancer Prev. Res., 8, 349–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Iyengar, N.M., et al. (2017) Metabolic obesity, adipose inflammation and elevated breast aromatase in women with normal body mass index. Cancer Prev. Res, 10, 235–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morris, P.G., et al. (2011) Inflammation and increased aromatase expression occur in the breast tissue of obese women with breast cancer. Cancer Prev. Res, 4, 1021–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Campbell, P.T., et al. (2009) A yearlong exercise intervention decreases CRP among obese postmenopausal women. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc., 41, 1533–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alemán, J.O., et al. (2017) Effects of rapid weight loss on systemic and adipose tissue inflammation and metabolism in obese postmenopausal women. J. Endocr. Soc., 1, 625–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dieli-Conwright, C.M., et al. (2018) Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise on metabolic syndrome, sarcopenic obesity, and circulating biomarkers in overweight or obese survivors of breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol., 36, 875–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). (2014) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Version 3.2014: Breast Cancer 2014.. http://www.nccn.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haka, A.S., et al. (2016) Exocytosis of macrophage lysosomes leads to digestion of apoptotic adipocytes and foam cell formation. J. Lipid Res., 57, 980–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kanda, H., et al. (2006) MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J. Clin. Invest., 116, 1494–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kamei, N., et al. (2006) Overexpression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in adipose tissues causes macrophage recruitment and insulin resistance. J. Biol. Chem., 281, 26602–26614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hume, D.A., et al. (2012) Therapeutic applications of macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) and antagonists of CSF-1 receptor (CSF-1R) signaling. Blood, 119, 1810–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Han, M.S., et al. (2020) Regulation of adipose tissue inflammation by interleukin 6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 117, 2751–2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mamane, Y., et al. (2009) The C3a anaphylatoxin receptor is a key mediator of insulin resistance and functions by modulating adipose tissue macrophage infiltration and activation. Diabetes, 58, 2006–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Park, B.V., et al. (2016) TGFβ1-mediated SMAD3 enhances PD-1 expression on antigen-specific T cells in cancer. Cancer Discov., 6, 1366–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seo, B.R., et al. (2015) Obesity-dependent changes in interstitial ECM mechanics promote breast tumorigenesis. Sci. Transl. Med., 7, 301ra130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Salmon, H., et al. (2012) Matrix architecture defines the preferential localization and migration of T cells into the stroma of human lung tumors. J. Clin. Invest., 122, 899–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mbongue, J.C., et al. (2015) The role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in immune suppression and autoimmunity. Vaccines, 3, 703–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Unal, R., et al. (2010) Matrix metalloproteinase-9 is increased in obese subjects and decreases in response to pioglitazone. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 95, 2993–3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Clyne, C.D., et al. (2002) Liver receptor homologue-1 (LRH-1) regulates expression of aromatase in preadipocytes. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 20591–20597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oberauer, R., et al. (2010) EGFL6 is increasingly expressed in human obesity and promotes proliferation of adipose tissue-derived stromal vascular cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem., 343, 257–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goodwin, P.J., et al. (2002) Fasting insulin and outcome in early-stage breast cancer: results of a prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Oncol., 20, 42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Salgado, R., et al. (2003) Circulating interleukin-6 predicts survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer, 103, 642–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guo, L., et al. (2015) C-reactive protein and risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep., 5, 10508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sun, X., et al. (2012) Normal breast tissue of obese women is enriched for macrophage markers and macrophage-associated gene expression. Breast Cancer Res. Treat., 131, 1003–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Heng, Y.J., et al. (2019) Molecular mechanisms linking high body mass index to breast cancer etiology in post-menopausal breast tumor and tumor-adjacent tissues. Breast Cancer Res. Treat., 173, 667–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Coussens, L.M., et al. (2002) Inflammation and cancer. Nature, 420, 860–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mantovani, A., et al. (2008) Cancer-related inflammation. Nature, 454, 436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pfeilschifter, J., et al. (2002) Changes in proinflammatory cytokine activity after menopause. Endocr. Rev., 23, 90–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Qureshi, R., et al. (2020) The major pre- and postmenopausal estrogens play opposing roles in obesity-driven mammary inflammation and breast cancer development. Cell Metab., 31, 1154–1172.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Alessi, M.C., et al. (2000) Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, transforming growth factor-beta1, and BMI are closely associated in human adipose tissue during morbid obesity. Diabetes, 49, 1374–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Favennec, M., et al. (2015) The kynurenine pathway is activated in human obesity and shifted toward kynurenine monooxygenase activation. Obesity, 23, 2066–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhao, Y., et al. (1996) Estrogen biosynthesis proximal to a breast tumor is stimulated by PGE2 via cyclic AMP, leading to activation of promoter II of the CYP19 (aromatase) gene. Endocrinology, 137, 5739–5742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bulun, S.E., et al. (2005) Regulation of aromatase expression in estrogen-responsive breast and uterine disease: from bench to treatment. Pharmacol. Rev., 57, 359–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Choy, L., et al. (2003) Transforming growth factor-beta inhibits adipocyte differentiation by Smad3 interacting with CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) and repressing C/EBP transactivation function. J. Biol. Chem., 278, 9609–9619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cawthorn, W.P., et al. (2007) Tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibits adipogenesis via a beta-catenin/TCF4(TCF7L2)-dependent pathway. Cell Death Differ., 14, 1361–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. An, J., et al. (2019) EGFL6 promotes breast cancer by simultaneously enhancing cancer cell metastasis and stimulating tumor angiogenesis. Oncogene, 38, 2123–2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Goodwin, P.J., et al. (2012) Insulin- and obesity-related variables in early-stage breast cancer: correlations and time course of prognostic associations. J. Clin. Oncol., 30, 164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Williams, S.A., et al. (2019) Plasma protein patterns as comprehensive indicators of health. Nat. Med., 25, 1851–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All RNA-sequencing data have been deposited at the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA), which is hosted by the EBI and the CRG, under accession number EGAS00001004665.