Abstract

Background.

The aim of this study was to clarify the pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia (FD), a highly prevalent gastrointestinal syndrome, and its relationship with the better understood syndrome of gastroparesis.

Methods.

Adult patients with chronic upper gastrointestinal symptoms were followed prospectively for 48 weeks in multi-center registry studies. Patients were classified as gastroparesis if gastric emptying was delayed; if not, they were labeled as FD if they met Rome III criteria. Study analysis was conducted using ANCOVA and regression models.

Results.

Of 944 patients enrolled over a 12-year period, 720 (76%) were in the gastroparesis group and 224 (24%) in the FD group. Baseline clinical characteristics and severity of upper gastrointestinal symptoms were highly similar. 48-week clinical outcome was also similar but at this time 42% of patients with an initial diagnosis of gastroparesis were reclassified as FD based on gastric emptying results at this time point, conversely, 37% of FD patients were reclassified as gastroparesis. Change in either direction was not associated with any difference in symptom severity changes. Full thickness biopsies of the stomach showed loss of interstitial cells of Cajal and CD206+ macrophages in both groups compared to obese controls.

Conclusions.

A year after initial classification, patients with FD and gastroparesis, as seen in tertiary referral centers at least, are not distinguishable by clinical and pathological features or by assessment of gastric emptying. Gastric emptying results are labile and do not reliably capture the pathophysiology of clinical symptoms in either condition. FD and gastroparesis are unified by characteristic pathological features and should be considered as part of the same spectrum of truly “organic” gastric neuromuscular disorders.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier:

Keywords: gastroparesis, functional dyspepsia, chronic nausea, gastric emptying, enteric nervous system

Introduction

Chronic nausea and vomiting and, when associated with delayed gastric emptying for solids and with no structural cause of obstruction, is called gastroparesis. Functional dyspepsia (FD), which is a far more common syndrome, affecting up to 10% of the general population, has traditionally thought to be a distinct clinical entity but its pathogenesis is unknown. However, a significant number of these patients present with symptoms suggestive of gastroparesis (e.g. nausea, vomiting, early satiety and postprandial fullness) but are found to have normal gastric emptying. Apart from “functional dyspepsia”, this syndrome has also been described as “gastroparesis-like syndrome” or “chronic unexplained nausea and vomiting” (CUNV).1,2 We have previously shown that these patients are clinically indistinguishable from those with delayed gastric emptying or gastroparesis.2 The true nature of FD and its relationship if any, to gastroparesis is an important issue to resolve, given the lack of insight into the pathogenesis of FD, despite its high prevalence in the general population.3,4 Our aim in this study was therefore to understand this relationship using the largest cohort of such patients available, all of them carefully phenotyped by validated clinical and physiological measures and followed prospectively over time. The large multi-center Gastroparesis Registry (GpR, GpR2) studies, prospective cohort studies conducted by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK)-funded Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium (GPCRC), has provided the opportunity to study these patients in a more comprehensive, prospective and systematic manner (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00398801, NCT01696747).

The main questions we asked were: (1) What are the differences and similarities in the symptom profile and clinical course of gastroparesis and FD? (2) Does the diagnosis of gastroparesis or FD by gastric emptying testing remain consistent over time? (3) How do enteric neuropathological changes in gastroparesis and FD compare to each other?

Methods

Patient Population

The NIDDK-funded Gastroparesis Registry studies are prospective cohort studies to investigate the natural history, epidemiology, and clinical course of gastroparesis. Patients were considered for enrollment in the registry if they had symptoms suggestive of gastroparesis, with or without delay in emptying (which may not have been available at the time of screening). We recruited patients with both delayed and normal emptying, generally in an approximately 5:1 ratio, but until the cap was reached (which was generally at a time point that was close to the end of the study), all patients that satisfied the inclusion/exclusion criteria were invited to participate, regardless of gastric emptying status. A complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria for the registry is provided in Appendix 2. In this study, we excluded patients with a history of Nissen or other fundoplication.

For our study, we included 981 adult patients participating in two gastroparesis registries from February 2007 through March 2019 with either diabetic (type 1 or type 2) or idiopathic etiology and analyzed gastric emptying results, symptom profiles and other patient outcomes over follow-up during which patients received standard-of-care treatment by their physicians. The registries consisted of patients meeting specific entry criteria with symptoms of at least 12-weeks’ duration and no abnormality causing obstruction on upper endoscopy. Patients with rapid gastric emptying were excluded from this study. Blood glucose levels were tested prior to scintigraphy and diabetic patients with a level of >270 mg/dl were rescheduled and/or received insulin. Gastroparesis was defined as percent retention > 60% at 2-hours and/or > 10% at 4-hours on the gastric emptying test.1 Functional dyspepsia (FD) at baseline was defined as percent retention ≤ 60% at 2-hours and ≤ 10% at 4-hours and meeting the criteria for FD using Rome III classification.1 37 patients with normal emptying and symptoms of gastroparesis were excluded due to not being classified as Functional Dyspepsia (FD) by Rome III criteria, leaving a total of 944 patients for the final analysis. A diagnosis of idiopathic etiology was based on no previous gastric surgery, no history of diabetes and a normal A1c.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at each clinical site and for the Scientific Data Research Center (SDRC). All patients provided written informed consent for each registry study of participation. The investigation conforms with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All authors had access to the study data and also reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Assessments

A detailed description of the standardized assessments performed on patients is provided in Appendix 3. Patient-reported demographic data was collected at baseline and patient-reported medical histories using face-to-face interviews along with a physical exam were conducted at baseline and each follow-up visit. Additional assessments include the gastric emptying scintigraphy (GES) test, a meal based emptying test at baseline and by protocol for GpR2, at 48-weeks,1 upper gastrointestinal symptom scores using the Patient Assessment of Upper Gastrointestinal Disorders Symptom Severity Index (PAGI-SYM) questionnaire and the related Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI), Rome III classification system for functional gastrointestinal disorders and psychological measurements (PAGI-Quality of Life (PAGI-QOL–), the physical and mental components of the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form V2 (SF-36v2); Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). For at least 72-hours prior to scintigraphy, patients were instructed to not use opioids, prokinetics, anticholinergics, or cannabinoids.

Full thickness gastric body biopsies were obtained from 9 idiopathic gastroparesis, 9 FD patients (non-diabetic) undergoing implantation of a gastric electrical stimulator and from 9 controls without diabetes or gastroparesis symptoms undergoing obesity surgery. There were eight females and 1 male in each of the three subgroups. Tissue collection was done in standardized fashion with established protocols by the participating sites of the GpCRC and was processed and analyzed by the histology core at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. Appendix 3, section Gastric Pathology includes details for collection, staining, light microscopy and quantification of the histologic biomarkers.

Statistical Methods

Two-sample t-tests or ANOVA for continuous and Pearson’s chi-square tests for categorical characteristics were used to compare the FD and Gastroparesis (Gp) subgroups for differences in various characteristics at baseline, including demographic, anthropometric, symptom profiles, clinical evaluations, type of nutrition, and psychological and quality of life assessments. The 2 subgroups were also compared for 12 patient outcomes over 48-weeks of follow-up using ANCOVA of the continuous outcomes with adjustment for the baseline value of the outcome and a subgroup (FD or Gp) indicator. Changes in gastroparesis diagnosis (DX) over 48-weeks were assessed by classifying each patient by their baseline and 48-week gastric emptying test DX, then using a Fisher’s exact text to assess whether the diagnosis changes from baseline to 48-weeks are random. ANCOVA, adjusting for the baseline symptom value and an indicator of DX change (change or no change in DX) for each subgroup at baseline, was used to assess whether the changes in each symptom severity over 48-weeks were different by converter status: if FD at baseline, then symptom changes from baseline were compared between those remaining FD or those DX Gp at 48-weeks, and if Gp at baseline, symptom changes over 48-weeks were compared between those remaining Gp and those DX FD (normal emptying) at 48-weeks.

For comparison of the histology results per biomarker between the 3 subgroups (Controls, FD, Gp), P values were determined from a mixed multiple linear regression model regressing each patient’s biomarker counts on the 3-category subgroup, accounting for the repeated measures per patient and multiple comparisons, and pairwise-P values from pairwise comparisons of the marginal linear predictions of the margins.

All P’s are nominal and two-sided. 95% confidence intervals or standard deviations were provided in all tables except for the binary measures in Tables 1 and 3, so that the amount of variation per measure could be considered in result interpretation. Complete case-analysis was used in all tables. Additional details for the statistical methods are provided in Appendix 3.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics by functional dyspepsia (FD) and gastroparesis

| Gastric Emptying Test Status* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| FD | Gastroparesis | ||

|

|

|||

| Baseline characteristic | Mean (SD) or No. (Percent) (N=224) | Mean (SD) or No. (Percent) (N=720) | P * |

| Demographics/lifestyle: | |||

| Sex: female | 199 (89%) | 603 (84%) | .06 |

| Race: White | 200 (89%) | 640 (89%) | |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic | 22 (10%) | 83 (12%) | .48 |

| Age at baseline (yrs) | 42.8 (13.9) | 43.0 (13.5) | .80 |

| Age at baseline (> 50 yrs) | 64 (29%) | 208 (29%) | .93 |

| Smoked (ever regularly) | 71 (32%) | 225 (31%) | .90 |

| Education: College degree or higher | 79 (35%) | 235 (33%) | .47 |

| Income (≥ $50,000) | 119 (53%) | 357 (50%) | .33 |

| Symptom severity (Global and PAGI-SYM‡): | |||

| Global symptom severity (Investigator-rated): | |||

| Mild | 37 (17%) | 117 (16%) | .04 |

| Moderate | 150 (67%) | 423 (59%) | |

| Gastric failure | 37 (17%) | 175 (24%) | |

| Predominant symptom on presentation: ‡ | |||

| Nausea | 88 (39%) | 225 (31%) | .16 |

| Vomiting | 41 (18%) | 158 (22%) | |

| Abdominal pain | 40 (18%) | 140 (19%) | |

| Any other symptom | 55 (25%) | 197 (27%) | |

| GCSI total score | 3.0 (0.9) | 2.9 (1.1) | .49 |

| Nausea/vomiting subscale | 2.2 (1.3) | 2.4 (1.4) | .11 |

| Post-prandial fullness subscale | 3.6 (1.0) | 3.4 (1.2) | .004 |

| Bloating subscale | 3.2 (1.6) | 3.1 (1.6) | .43 |

| Abdominal pain moderate/severe‡ | 148 (67%) | 472 (66%) | .80 |

| Upper abdominal pain subscale | 3.0 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.5) | .92 |

| Upper abdominal pain severity score | 2.9 (1.5) | 3.0 (1.7) | .91 |

| Upper abdominal discomfort score | 3.1 (1.4) | 3.2 (1.6) | .93 |

| GERD subscale | 1.9 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.4) | .29 |

| Gastric Emptying Scintigraphy (GES): | |||

| % Retention at 2-hours | 33.0 (14.6) | 65.0 (18.0) | n/a |

| % Retention at 4-hours | 4.3 (3.0) | 32.2 (22.0) | n/a |

| Delayed emptying at 2-hours | 0 (0%) | 455 (63%) | n/a |

| Delayed emptying at 4-hours‡ | 0 (0%) | 673 (94%) | n/a |

| Clinical factors: | |||

| Etiology: | .008 | ||

| Idiopathic | 170 (76%) | 472 (66%) | |

| Diabetes Type 1 | 22 (10%) | 125 (17%) | |

| Diabetes Type 2 | 32 (14%) | 123 (17%) | |

| Body Mass Index (BMI): | |||

| Overweight or obese (BMI >25) | 117 (52%) | 406 (56%) | .27 |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 27.9 (8.7) | 27.4 (7.5) | .35 |

| Duration of symptoms at enrollment (years) | 6.1 (7.4) | 5.5 (6.8) | .28 |

| Acute onset of symptoms | 92 (41%) | 326 (45%) | .27 |

| Initial infectious prodrome | 45 (20%) | 135 (19%) | .66 |

| Inflammation‡ | 86 (38%) | 333 (46%) | .04 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 1.0 (1.8) | 1.9 (6.3) | .02 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 15.8 (15.6) | 19.7 (20.0) | .007 |

| HbAlc (%) | 6.0 (1.4) | 6.4 (1.8) | .01 |

| Treatment (current use at baseline): | |||

| Narcotics use | 78 (35%) | 278 (39%) | .31 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 150 (67%) | 541 (75%) | .02 |

| Prokinetics | 66 (29%) | 329 (46%) | <.001 |

| Antiemetics | 138 (62%) | 451 (63%) | .81 |

| Antidepressants | 116 (52%) | 347 (48%) | .35 |

| Anxiolytics | 45 (20%) | 163 (23%) | .42 |

| Pain modulators | 55 (25%) | 182 (25%) | .83 |

| On total parental nutrition (TPN) | 7 (3%) | 52 (7%) | .03 |

| Gastric electric stimulation device implantation | 17 (8%) | 44 (6%) | .43 |

| Psychological & QOL | |||

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score | 18.3 (11.5) | 18.5 (11.3) | .83 |

| Moderate to severe depression (BDI>20)‡ | 91 (41%) | 296 (41%) | .90 |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI): | |||

| State Anxiety score | 43.4 (13.4) | 44.2 (13.7) | .44 |

| Severe state anxiety (≥ 50)‡ | 73 (33%) | 252 (35%) | .51 |

| Trait Anxiety score | 43.0 (12.9) | 43.7 (12.6) | .47 |

| Severe trait anxiety (≥ 50)‡ | 69 (31%) | 237 (33%) | .56 |

| Quality of Life total score | 2.6 (1.1) | 2.6 (1.1) | .98 |

| PAGI-QOL‡ ≥ 3 | 80 (36%) | 265 (37%) | .85 |

| Overall Health Survey‡ (SF-36 v2) | |||

| Physical health component subscore | 33.8 (11.0) | 33.2 (10.6) | .53 |

| Mental health component subscore | 40.3 (12.2) | 38.9 (13.0) | .15 |

GpR and GpR2 patients with either idiopathic or diabetic etiology without rapid gastric emptying are included. 37 patients with normal emptying and symptoms of gastroparesis were excluded due to not being classified as Functional Dyspepsia (FD) by Rome III criteria (Total N=944).

Functional Dyspepsia (FD) defined as percent retention from a Gastric Emptying Test (GET) being ≤ 60% at 2-hours and ≤ 10% at 4-hours and meeting the criteria for FD using Rome III classification.

Gastroparesis defined as percent retention from a GET being > 60% at 2-hours and/or > 10% at 4-hours.

Percentages or averages for each characteristic determined from patients with non-missing data for that characteristic.

Of the 48 characteristics compared, 3 would be likely be significant (at alpha=.05) due to chance.

P value (2-sided) derived from either a t-test or ANOVA for continuous predictors, or Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical predictors. Bold font denotes a P <.05. n/a denotes not applicable.

PAGI-SYM scores report patient-rated severity of symptoms from 0 (none) to 5 (severe) in the past 2 weeks.

Predominant symptom at presentation (baseline visit) is the main reason for evaluation that the patient reported; it was categorized to report the 3 most frequent issues; the other category includes bloating, early satiety, post-prandial fullness, diarrhea, constipation, anorexia, GERD symptoms, poorly managed diabetes or glycemic control and a weight change (loss or gain).

Abdominal pain moderate/severe defined as either upper abdominal pain or discomfort PAGI-SYM symptom score ≥ 3

The 46 patients without delayed emptying at 4-hours (due to missing % retention data) were delayed emptying at 2-hours.

Inflammation defined as either CRP > 1.0 mg/dL or ESR > 20 mm/hr

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) > 20 indicates moderate or more severe depression.

STAI scores ≥ 50 indicate severe state or trait anxiety.

PAGI-QOL score increases with increased quality of life due to gastroparesis symptoms in past 2 weeks.

SF-36v2 score increases with increased general quality of life in the past 4 weeks.

Table 3.

Change in diagnosis of functional dyspepsia (FD) and gastroparesis (Gp) at baseline and 48-week follow-up based on solid gastric emptying (GE)

| Total Patients (N=249) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 48 Weeks | |||

| Baseline | Gp | FD | |

| Diagnosis | Gp (N=189) | 110 (58%) | 79 (42%) |

| Median at 4-hr GE | Median at 4-hr GE | Median at 4-hr GE | |

| Total patients | 24.0% [16.0, 40.0] | ||

| Gp to Gp | 25.5% [16.5, 42.0] | 23.0% [16.0,38.0] | |

| Gp to FD | 23.0% [14.7, 35.3] | 3.0% [1.9, 5.0] | |

| Diagnosis | FD (N=60) | 22 (37%) | 38 (63%) |

| Median at 4-hr GE | Median at 4-hr GE | Median at 4-hr GE | |

| Total patients | 5.0% [2.5, 8.0] | ||

| FD to FD | 6.0% [2.5, 8.0] | 3.0% [2.0, 5.1] | |

| FD to Gp | 5.0% [2.5, 8.0] | 14.6% [12.6, 21.0] | |

|

| |||

| % Diagnosis Changed | 41% [(79+22)/249] | ||

| % Unchanged | 59% [(110+38)/249] | ||

| P-value† | .005 | ||

Idiopathic (N=182) and diabetic patients (N=67) with baseline and 48-week gastric emptying scintigraphy (GES) test were included; 7 patients with normal emptying and symptoms of gastroparesis not classified as functional dyspepsia (FD) using Rome III were excluded; 34 patients in GpR1, 215 in GpR2.

Presented are the number (percent) of patients in each diagnosis category, and respective medians [IQR] values of each %-gastric retention at 4-hours distribution at baseline and 48-weeks. Gp to Gp: Patients diagnosed with gastroparesis at baseline and who remained in that category at 48-weeks; Gp to FD: Patients diagnosed with gastroparesis at baseline and who were classified as FD (normal emptying) at 48-weeks; FD to FD: Patients diagnosed with normal emptying and FD at baseline and who remained in that category at 48-weeks; FD to Gp: Patients diagnosed with FD at baseline and who were classified as gastroparesis at 48-weeks.

When analyzed separately by etiology subgroup, 75/182 (41%) of the idiopathic subgroup and 26/67 (39%) of the diabetic subgroup changed diagnosis between the baseline and 48-week GES test (P=.40), where P was determined from a logistic regression of the baseline GES diagnosis on the follow-up diagnosis, etiology subgroup, and an interaction term for etiology and follow-up GES diagnosis.

P tests the null hypothesis that the diagnosis changes from baseline to 48-weeks are random. P computed using Fisher’s exact test (2-sided). Bold font denotes a P <.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients with functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis are very similar.

Of a total of 944 patients enrolled over a 12-year period, 720 (76%) met criteria for gastroparesis on scintigraphy while 224 (24%) had normal emptying and met the criteria for FD (a detailed classification of the two groups by Rome III criteria is provided in Supplemental Table 1). The two groups were similar across a broad range of metrics, with only a few statistically significant differences of uncertain clinical significance (Table 1). There was a slightly higher proportion of patients in the idiopathic category (as compared with diabetic gastroparesis) in the group with normal emptying (76% vs. 66%; P=0.008); this was also reflected in the difference in HbA1c (6.0 vs. 6.4; P=.01). Patients with normal gastric emptying had milder overall severity by a physician-rated scale with 17% of patients with normal emptying classified as “gastric failure” (requiring enteral or parenteral nutrition) as compared with 24% of the gastroparesis group (P=.01); only 3% required total parenteral nutrition (as compared with 7% in the gastroparesis group; P=.03) The proportion of patients with general markers of inflammation (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate) was also lower in patients with normal gastric emptying (38% vs. 46%; P=.04) with lower mean values for these tests as well. As to be expected, prokinetic use was substantially higher in patients with delayed emptying (46% vs. 29%; P<0.001) while the use of proton pump inhibitors was slightly higher (75% vs. 67%; P=.02). Notably, psychological and quality metrics were equivalent in both groups. When analyzed separately, patients with gastroparesis and those who met Rome III criteria for FD were also similar to the FD (normal emptying) group at enrollment (Supplemental Table 2).

Change in global outcomes over the first 48 weeks in patients with functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis are also similar.

Data at 48-weeks of longitudinal follow-up were available in 130–159 patients (depending on the specified outcome) with FD and 449–456 patients with gastroparesis. Clinical improvement at 48-weeks, as previously defined by us (a decline of 1 or more in the total GCSI score)5, was seen in 27% and 26% of the FD and gastroparesis groups, respectively, and this did not vary with etiology (idiopathic or diabetic). 48-week GCSI scores, as described in Table 2, improved slightly in both groups by about 0.4 points, which did not meet the threshold for being considered clinically meaningful.

Table 2.

48-week changes from baseline in gastroparesis symptoms (GCSI), anthropometry, clinical factors, depression and quality of life in patients with gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia (FD)

| FD* (N=159) | Gastroparesis (Gp)* (N=456) | P‡ | Mean net change: FD-Gp | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome characteristics | Mean | Mean | 95% | Mean | Mean | 95% | FD vs | Mean Net Δ | Mean Net Δ | |

| Baseline | Δ† | C.I. | Baseline | Δ† | C.I. | Gp | ΔFD - ΔGp | C.I. | P§ | |

| Symptom Severity: | ||||||||||

| Patient-rated overall GCSI score (PAGI-SYM) | 3.1 | −0.40 | −0.57,−0.23 | 2.9 | −0.37 | −0.47,−0.27 | .88 | −.03 | −0.23,0.18 | .80 |

| Patient-rated improvement in GCSI of 1+ points from BL | n/a | 27% | 19, 35% | n/a | 26% | 22, 30% | .86 | 1% | −8%, 9% | .86 |

| Anthropometric: | ||||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.6 | 0.26 | −0.14,0.67 | 27.5 | 0.56 | 0.31,0.82 | .24 | −0.30 | −0.81,0.22 | .26 |

| Weight (kg) | 76.3 | 0.77 | −0.32,1.87 | 74.3 | 1.44 | 0.78,2.10 | .28 | −0.67 | −2.00,0.66 | .32 |

| Clinical factors¶: | ||||||||||

| Total hospitalizations (no.)** | 1.1 | −0.47 | −94,0.0001 | 2.1 | −0.91 | −1.26,−0.56 | .12 | −0.51 | −1.14,0.13 | .12 |

| On Total Parental Nutrition (%) | 2.8% | 2.1% | −1.6,5.8% | 7.2% | −2.8% | −5.4,− 03% | .54 | 4.9% | −0.5,10.2% | .07 |

| Psychological & Quality of Life | ||||||||||

| Depression (BDI) | 18.3 | 0.17 | −1.23,1.58 | 18.5 | −0.48 | −1.40,0.44 | .42 | 0.65 | −1.21,2.51 | .49 |

| State Anxiety total score | 43.3 | 1.03 | −0.94,2.99 | 44.0 | 0.27 | −−1.00,1.53 | .56 | 0.76 | −1.81,3.33 | .56 |

| Trait Anxiety total score | 43.1 | 1.16 | −0.43,2.75 | 43.6 | 0.21 | −0.78,1.20 | .34 | 0.95 | −1.07,2.98 | .36 |

| PAGI-QOL total score | 2.5 | 0.26 | 0.11,0.42 | 2.6 | 0.24 | 0.15,0.33 | .92 | 0.02 | −0.16,0.20 | .82 |

| SF-36v2 physical component | 33.3 | 1.51 | 0.09,2.93 | 33.5 | 1.11 | 0.27,1.95 | .54 | 0.41 | −1.33,2.14 | .64 |

| SF-36v2 mental component | 40.3 | 0.19 | −1.63,2.01 | 38.7 | 1.39 | 0.23,2.55 | .57 | −1.20 | −3.55,1.16 | .32 |

Total N determined by the value for the outcome being available at baseline and at 48 weeks; Total N varies between 449 and 456 for number of patients with gastroparesis; and for those with normal emptying and functional dyspepsia using Rome III (FD), between 130 and 159, and overall total patients between 579 and 615.

Gastroparesis (Gp) patients have delayed gastric emptying defined as delayed gastric emptying scintigraphy of > 60% at 2-hour or > 10% at 4-hour. FD patients have gastroparesis symptoms and normal gastric emptying. Patients with idiopathic or diabetic etiology and without rapid emptying were included.

Mean change of outcome (48 weeks – baseline) and 95% confidence interval (C.I.) for the mean change presented, as well as the mean change in the mean changes of each subgroup (mean change of outcome for FD – mean change of outcome for gastroparesis).

P values for continuous outcome characteristics determined using ANCOVA of each characteristic of change at 48-weeks from baseline in relation to delayed gastric retention indicator (FD vs Gastroparesis) with adjustment for the baseline value of the characteristic. P for 1+ point improvement in GCSI was determined from a generalized linear model (GLM) with binomial distribution. P for the total hospitalizations in past year determined from a zero-inflated negative binomial regression of total hospitalizations in relation to delay indicator with adjustment for the total hospitalizations in year prior to baseline. P value for TPN as a percent was derived from a Wald test to assess whether change in TPN use varied by delayed retention adjusting for the baseline. TPN use using ANCOVA with robust variance.

For continuous variables, mean net change defined as the difference of the mean change in outcome indicator (value at 48 weeks – at baseline) in patients with FD classification minus the mean change in outcome indicator in patients with gastroparesis; 95% confidence intervals (C.I.) for the net mean change between gastric retention groups computed from a t-test. For GCSI 1+ improvement, the difference, 95% C.I. and P determined using the 2-subgroup proportion test.

ED visits were not reported at baseline. The total number of ED visits from baseline to 48 weeks was: 1.71±4.13 for all patients, 1.38±3.41 for the FD patients, 1.81±4.33 for gastroparesis patients, P=12 (determined using a zero-inflated negative binomial regression with robust variance).

Total hospitalizations since baseline excluded enterra placement or removal.

The diagnosis of gastroparesis or functional dyspepsia based on gastric emptying is labile over time, can move in both directions and has no impact on change in symptoms.

Data from gastric scintigraphy performed approximately 48-weeks after enrollment in the study was available in 249 patients. Patients with a gastric emptying test at 48-weeks were very similar to those patients that did not have a gastric emptying test when compared on baseline characteristics using a logistic regression. The only difference evident was self-reported ethnicity (identifying as Hispanic/LatinX) was 70% less likely in those without a 48-week GES compared to those with a follow-up GES (P<.001) (Supplemental Table 4).

Overall 41% of this cohort could be categorically transferred from one group to the other after 48-weeks (Table 3). Of 189 patients with a diagnosis of gastroparesis at baseline, 79 (42%) had normal emptying at 48-weeks, thus no longer satisfying the definition of gastroparesis. Conversely, of the 60 patients with FD (normal gastric emptying at baseline), 22 (37%) showed delayed emptying at 48-weeks, thus qualifying for the diagnosis of gastroparesis. These findings hold true irrespective of etiology as 41% of the idiopathic and 39% of the diabetic population undergo a change in the diagnosis of FD or gastroparesis after 48 weeks (P<.40).

We also analyzed whether gastroparesis patients with milder delays in emptying were more likely to have normal emptying at 48-weeks and hence may represent “outliers” that were misclassified by scintigraphy. When classified according to severity of delay at baseline by four-hour retention as “mild” (>10%, n=169), “moderate” (>20%, n=104), “severe” (>35%, n=54), “very severe” (>50%, n=26)), the conversion rates to normal emptying at 48-weeks were 41%, 39%, 40% and 27%, respectively (P=.64).

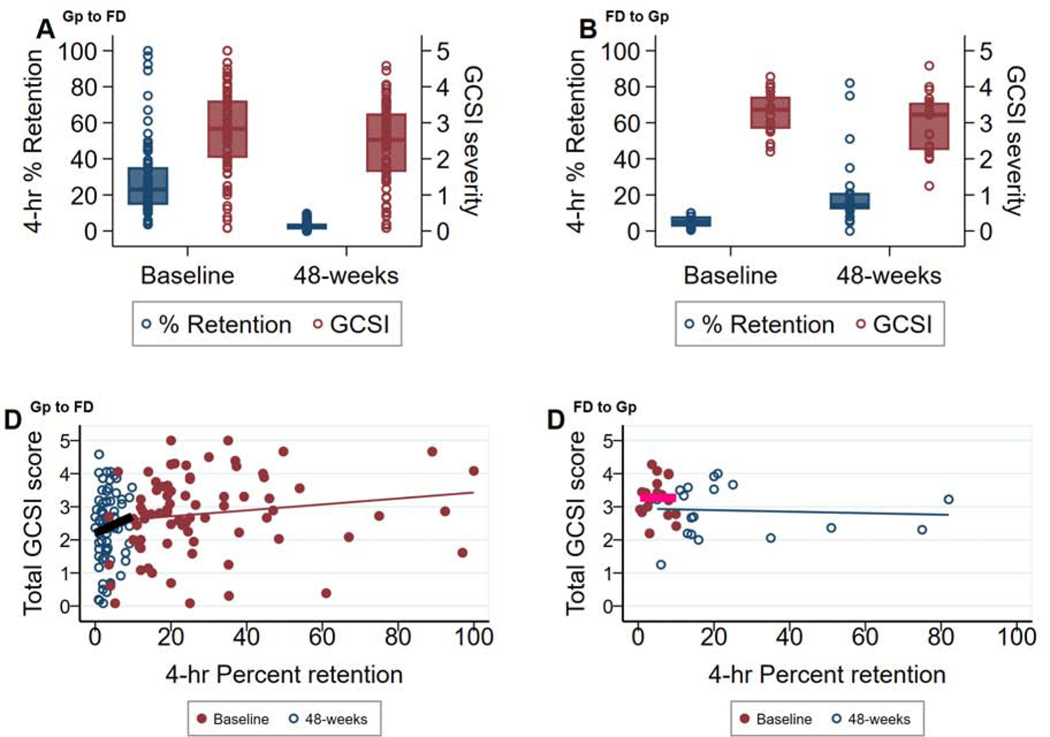

Further, analysis of symptom scores in these patients showed mild improvements after 48-weeks, consistent with those reported for the larger cohorts, regardless of whether gastric emptying had improved or worsened enough to change the initial diagnosis (Table 4). The correlation between gastric retention values and GCSI total scores at baseline and at 48-weeks (grouped according to initial GES diagnosis), along with the medians and range, are shown in Figure 1. Corresponding medians and range for GCSI subclusters are shown in Supplemental Figure S1. No significant correlations between emptying and symptom severity were seen at either time point and in either group, confirming previously published results from our group.2 These changes in diagnosis were not accompanied by any significant changes in HbA1c levels, medication use, TPN or electrical stimulator utilization (Table 5). Rome III classifications at baseline and at 48-weeks for these patients are provided ibn Supplemental Figure S2.

Table 4.

Changes in gastroparesis symptom scores by changes in gastric emptying diagnosis over 48-weeks of follow-up

| Functional Dyspepsia (FD) at Baseline* (N=60) | Gastroparesis (Gp) at Baseline* (N=189) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFD at 48-weeks (N=43) | Gp at 48-weeks (N=22) | P † | Gp at 48-weeks (N=110) | FD at 48-weeks (N=79) | P † | |

| Changes in PAGI-SYM symptom severity (0–5) scores at 48-weeks from baseline: | ||||||

| Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI)‡ | −0.2 (1.2) | −0.4 (0.6) | .82 | −0.3 (1.0) | −0.4 (1.1) | .21 |

| Nausea severity | 0.0 (1.3) | −0.2 (1.7) | .84 | −0.3 (1.5) | −0.7 (1.5) | .11 |

| Retching severity | 0.3 (1.6) | 0.2 (1.1) | .78 | −0.4 (1.6) | −0.5 (1.8) | .27 |

| Vomiting severity | 0.4 (1.6) | 0.2 (0.9) | .75 | −0.3 (1.8) | −0.5 (1.8) | .25 |

| Nausea subscale‡ | 0.2 (1.2) | 0.1 (0.8) | .70 | −0.4 (1.3) | −0.6 (1.4) | .13 |

| Feeling of stomach fullness severity | −0.3 (1.2) | −0.7 (1.1) | .45 | −0.3 (1.5) | −0.3 (1.7) | .70 |

| Inability to finish meal severity | −0.8 (1.7) | −0.9 (0.8) | .70 | −0.4 (1.6) | −0.5 (1.7) | .43 |

| Excessively full after meal severity | −0.4 (1.3) | −0.5 (1.0) | .78 | −0.3 (1.5) | −0.3 (1.6) | .65 |

| Loss of appetite severity | −0.8 (1.7) | −1.5 (1.2) | .32 | −0.3 (1.7) | −0.5 (1.7) | .45 |

| Post-prandial fullness subscale‡ | −0.6 (1.2) | −0.9 (0.7) | .43 | −0.3 (1.2) | −0.4 (1.3) | .48 |

| Visibly larger stomach severity | −0.2 (2.1) | 0.1 (1.1) | .86 | −0.2 (1.7) | −0.1 (1.5) | .58 |

| Bloating severity | −0.4 (1.7) | −0.5 (1.1) | .71 | −0.3 (1.5) | −0.3 (1.6) | .42 |

| Bloating subscale‡ | −0.3 (1.8) | −0.2 (.9) | .44 | −0.2 (1.5) | −0.2 (1.5) | .61 |

| Upper abdominal pain | −0.2 (1.5) | −0.9 (1.4) | .68 | −0.3 (1.7) | −0.5 (1.6) | .23 |

| Upper abdominal discomfort | −0.4 (1.4) | −0.7 (1.2) | .85 | −0.2 (1.7) | −0.6 (1.4) | .08 |

| Upper abdominal pain subscale‡ | −0.3 (1.3) | −0.8 (1.3) | .77 | −0.3 (1.6) | −0.6 (1.4) | .12 |

| GERD subscale‡ | −0.1 (0.9) | −0.2 (1.1) | .78 | −0.3 (1.1) | −0.5 (1.1) | .11 |

Data for symptom changes presented are means ± standard deviations. PAGI-SYM severity scores range from 0 to 5 indicating symptom severity of none to very severe over the past 2-weeks. Positive change in symptom severity at 48-weeks from baseline indicates worsening of the symptom and negative change indicates a decrease in severity.

Symptom changes were analyzed between converter status within 2 subgroups (FD or Gastroparesis (Gp) at baseline) using an ANCOVA regressing the change in symptom score on the subgroup indicator (change in DX at 48 weeks, or no change), adjusting for the baseline value of the symptom.

Definitions: Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index = (nausea subscale + postprandial fullness subscale + bloating subscale)/3 where:

Nausea subscale = (nausea + retching + vomiting)/3

Postprandial fullness/early satiety subscale = (stomach fullness + inability to finish meal + excessively full + loss of appetite)/4

Bloating subscale = (bloating + large stomach)/2

GERD subscale = (heartburn day + heartburn lying down + chest discomfort day + chest discomfort night + reflux day + reflux night + bitter taste)/7

Upper abdominal pain subscale = (upper abdominal pain + upper abdominal discomfort)/2

Figure 1:

79 patients with gastroparesis (Gp) and 22 patients with Gp symptoms, normal gastric retention and functional dyspepsia (FD) using the Rome III classification at enrollment are compared by 4-hour % gastric retention and severity of the total GCSI score (0–5) at baseline and at 48-weeks of follow-up. Boxplots and dot plot distributions of total GCSI (blue) and % gastric retention (maroon) are displayed. Each dot represents a patient’s values. (A): 79 patients with Gp at baseline had normal gastric retention at 48-weeks (Gp converters) and (B): 22 patients without delayed retention (FD) at baseline had delayed gastric emptying at 48-weeks (FD converters). Total GCSI remained similar at both time points. Scatterplots and fitted regression lines at baseline (maroon, pink regression line) and 48-weeks (blue) are displayed. (C) Gp converters: y=2.53 + 0.009*x, r=0.16 at baseline and y=2.20 + 0.05*x, r=0.13 at 48-weeks, and (D) FD converters: y=3.28 – 0.001*x, r=−0.01 at baseline and y=2.94 – 0.002*x, -r=.07, where y=GCSI score and x=% gastric retention.

Table 5.

Changes in HbA1c level and medication use by changes in gastric emptying diagnosis over 48-weeks of follow-up

| Functional Dyspepsia (FD) at Baseline (N=60) | Gastroparesis (Gp) at Baseline (N=189) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changes in HbA1c and Medication Use over 48-weeks of follow-up | FD at 48-weeks (N=38) | Gp at 48-weeks (N=22) | P | Gp at 48-weeks (N=110) | FD at 48-weeks (N=79) | P |

| HbA1c (%)‡ | 0.12 (0.83) | 0.60 (1.55) | .40 | 0.29 (1.25) | 0.18 (1.71) | .77 |

| Medication use over 48 weeks (%) | ||||||

| Narcotics use | 13.9% (54.3) | 22.7% (42.9) | .80 | 15.7% (43.6) | 11.0% (35.6) | .37 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | –2.8% (50.6) | –9.1% (52.6) | .74 | 2.8% (48.3) | –8.2% (46.4) | .12 |

| Prokinetics | –2.8% (56.0) | 0% (43.6) | .26 | 6.5% (49.8) | 5.5% (0.50) | .43 |

| Antiemetics | 2.8% (37.7) | 9.1% (29.4) | .62 | 11.1% (43.9) | 5.5% (46.8) | .20 |

| Antidepressants | –22.2% (54.0) | –9.1% (52.6) | .27 | –10.2% (51.0) | 0% (60.1) | .18 |

| Anxiolytics | 11.1% (57.5) | 13.6% (35.1) | .95 | 14.8% (47.0) | 15.1% (43.0) | .48 |

| Pain modulators | 5.6% (53.2) | 9.1% (61.0) | .95 | 9.3% (39.9) | 6.8% (25.4) | .40 |

| Cannabinoids | 0% (33.8) | 4.5% (21.3) | .46 | 2.8% (25.4) | 9.6% (29.6) | .22 |

| Treatment use over 48 weeks (%) | ||||||

| On total parental nutrition (TPN) | –2.8% (16.7) | –4.5% (21.3) | .33 | 0.9% (21.6) | –5.5% (28.3) | .54 |

| Gastric electric stimulation device implantation | 8.3% (43.9) | 4.5% (37.5 | .34 | 13.0% (41.2) | 9.6% (37.9) | .72 |

Data for changes in HbA1c and any medication use presented are mean changes ± standard deviations. Positive change in Hba1c value or medication use at 48-weeks from baseline indicates worsening of the HbA1c and increasing use of medications. Patients included in this analysis had paired (baseline and 48-week) gastric emptying tests and follow-up history case-reports.

Change in HbA1c was analyzed between converter status within 2 subgroups (FD or Gastroparesis (Gp) at baseline) with an ANCOVA, regressing HbA1c change on baseline HbA1c and converter subgroup. P values for medication and treatment use changes over follow-up as percents were derived from a Wald test to assess whether change in use varied by converter status adjusting for the baseline use by each subgroup using ANCOVA with robust variance.

HbA1c required at baseline for all patients and at follow-up for diabetics, and if available, for non-diabetics. For FD converters, N=9 and 11 patients with both values at fup, and for Gp converters, there were N=36 and N=21 patients with paired HbA1c values at follow-up.

There are 2 patients without paired GES and medication use data in the FD converter subgroup (N=36 and 22) and 8 patients without paired data for analysis in the Gp converter subgroup (N=108 and 73).

Functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis share the same characteristic neuropathology.

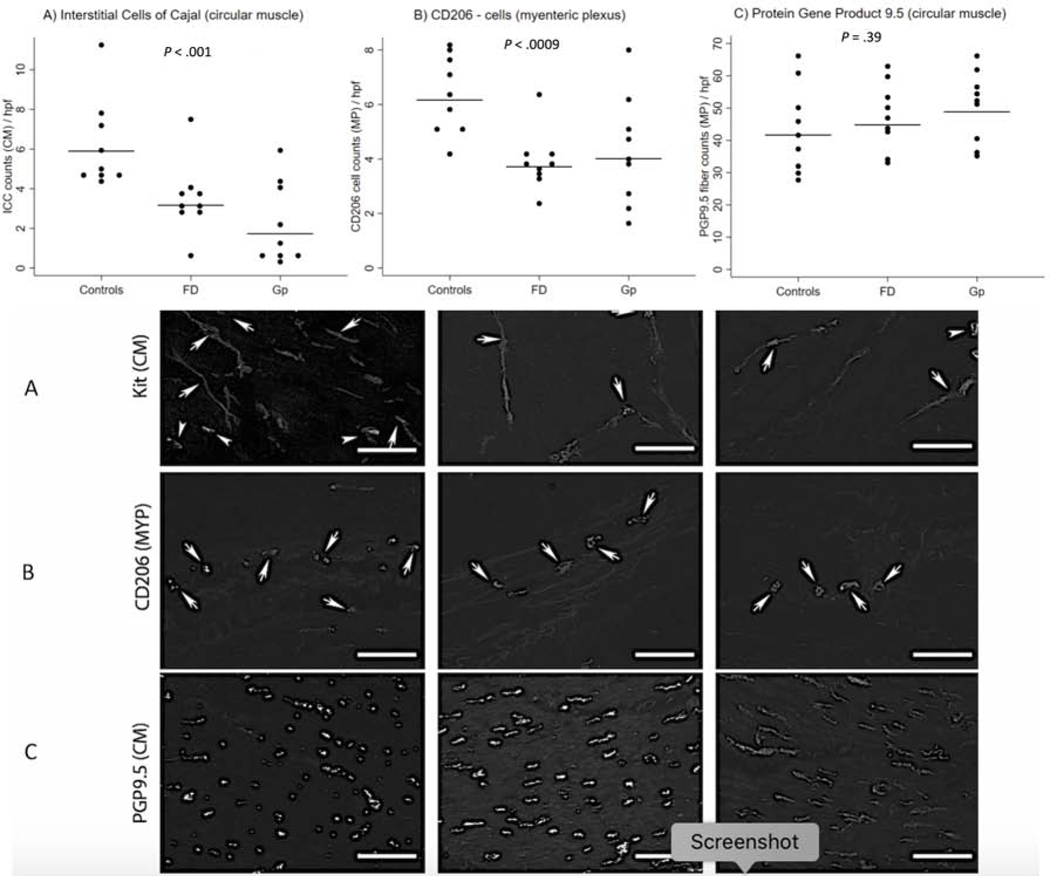

We have previously shown that the most prominent pathological changes in gastroparesis are a loss of interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) which set the electrical rhythm and transduce neuromuscular signals and reduced numbers of anti-inflammatory C206+ macrophages.6,7 Full-thickness gastric body biopsy specimens were surgically obtained in a subset of patients with FD and gastroparesis and compared to matched controls (n=9 each, all non-diabetic) for histological changes as previously described. The median retention at 4-hours (Q1,Q3) was 2.0% (1.0,4.0) and 24% (20.0,60.0) for the FD and gastroparesis groups, respectively. A detailed comparison of the baseline clinical and other characteristics for these 18 patients is described in Supplemental Table 3; as can be seen, the two groups were very similar. As compared with controls, a significant loss of interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) along with a decrease in myenteric plexus CD206 positive staining was seen in both patient subgroups (Figure 2). Protein Gene Product (PGP) 9.5 (a marker for neurons) counts/high power field were similar in all 3 groups as were a variety of other histological markers (Supplemental Table 6).

Figure 2:

Three histologic biomarkers were analyzed over 3 subgroups, each with 9 non-diabetic patients’ samples per group: Controls, functional dyspepsia (FD) and normal emptying and gastroparesis (Gp). The biomarkers were determined using stained stomach tissue slides, with multiple counts per circular field under high-powered focus (hpf) per patient. The number of counts per patient varied by the histological biomarker and patient. Each figure displays individual patient’s mean count (dots) and the adjusted mean count per subgroup (horizontal line). P (2-sided) determined using a mixed multiple linear regression model regressing each patient’s biomarker counts on the 3-category subgroup, accounting for the repeated measures per patient.

Top - figure: (A) Interstitial Cells of Cajal (expressing c-Kit) in circular muscle showing decreased cell count numbers in FD and gastroparesis in a linear trend from controls (P≤.0001), with no difference seen between the two syndromes (B) CD206 (myenteric plexus) positive macrophage counts showing decreased numbers in both FD and gastroparesis (P≤.0009), with no difference seen between the two syndromes (C) Neuronal counts (as measured by Protein Gene Product 9.5 (PGP9.5) staining) in circular muscle showed no difference between any of the three groups (P=.39).

Bottom - image: Images of histological changes in control patients and patients with functional dyspepsia (FD) and idiopathic gastroparesis. (A): c-Kit (circular muscle) showing decreased immunoreactivity in FD and idiopathic gastroparesis (arrows (horizontal lines) indicate interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) with slender bodies and 2–3 processes; arrowheads indicate mast cells with larger, rounded bodies and no processes. (B): CD206 staining of myenteric plexi showing decreased immunoreactivity in both FD and gastroparesis. (C): PGP9.5 staining for neurons. Images obtained at 20x magnification (scale=20 μm).

Discussion

In this study, we hypothesized that FD and gastroparesis may be part of the same clinicopathological spectrum of gastric neuromuscular dysfunction and that the classical biomarker, gastric emptying, may not be useful in separating these two disorders. We first performed a cross-sectional analysis of baseline characteristics of patients in the two groups (Table 1). Although some of the symptoms were of milder severity in the FD as compared with the gastroparesis group, these differences were minor and of equivocal clinical significance. We then examined changes in symptom severity and other outcomes after a year of follow-up (Table 2) and found no significant differences between the two groups, with only a minority of patients showing clinically important improvement, regardless of the initial diagnosis. Thus, these results show no significant or meaningful differences across multiple metrics, attesting to the clinical similarities of the two groups.

The striking clinical similarities amongst the two groups prompted us to reconsider the significance of an abnormal gastric emptying test in these patients, with the hypothesis that gastric emptying is not a reliable marker to distinguish them. We tested this by examining changes in gastric emptying over time and found that in a large number of patients (41% of the idiopathic and 39% of the diabetic population) gastric emptying testing would have reclassified the patients into the alternative group after a year. Smaller studies have suggested that gastric emptying remains on an average stable over prolonged periods of time in diabetic gastroparesis.8 In one of these, gastric emptying (not using currently accepted standardized methodology) was delayed at baseline in 8 of 13 patients, with 3 of these normalizing over a 25-year period without change in symptoms.9 Other investigators have also shown that over time many patients initially diagnosed with gastroparesis may normalize emptying over time.10 Our study shows that movement between the two groups can be in both directions: patients with normal emptying can exhibit delayed emptying when tested at a later time point and vice-versa. Further, gastroparesis patients across the spectrum of delay were similar in their frequency of conversion to FD and therefore this was not a phenomenon confined to those close to the cusp between delayed and normal emptying. Our findings indicate a significant lack of reproducibility of gastric emptying, either due to intrinsic limitations in the test methodology or because gastric emptying in a given patient may vary highly over time. A recent study examined the reproducibility of scintigraphic measurement of gastric emptying by repeating the test an average of 15 days later and showed significantly high coefficients of variation (COV): 2-hour, 4-hour and T1/2 of 23%, 20% and 20%, respectively.11 In 30% of the cohort of sixty patients that included both diabetic and idiopathic patients, the interpretation of gastric emptying as normal, rapid, or delayed was different between the two time points. These results, along with ours, provide strong support for the conclusions that gastric emptying is not a reliable method to discriminate between the two conditions.

Equally if not more importantly, symptom severity remained on average unchanged despite the change in gastric emptying status. The relationship between gastric emptying has remained a point of controversy in the literature with some investigators arguing that the discrepancy has been due to non-standardized assays and the fact that most studies have not measured symptoms at the same time as measuring gastric emptying.10,12 The results of our present study add a new and different kind of evidence to support our previous findings that symptom severity does not correlate with rates of gastric emptying, which is also in keeping with other reports in the literature, as discussed previously.

Recognizing that pathological changes in the target tissue is required to ultimately prove that the two conditions are indeed similar, we proceeded to examination of full-thickness gastric biopsies obtained from a subset of patients with FD and gastroparesis and compared them with matched controls. We have previously shown patients with gastroparesis exhibit loss of interstitial cells of Cajal or ICC (these cells are important for setting the electrical rhythm and neuromuscular coupling) accompanied by shift in the myenteric macrophage phenotype indicated by a reduction in the CD206-expressing population that normally play an anti-inflammatory role.6,7 Our findings confirmed our previous results in gastroparesis but more importantly, indicated the stomach of patients with FD had the same characteristic pathology i.e. loss of ICC and CD206-expressing macrophages. As previously shown by us in gastroparesis by itself, no overt loss of neurons was seen in the FD group either. Although a previous study had also shown loss of ICC in patients with FD,13 our results extend that to include the neuronal and macrophage population and the first to report a head-to-head comparison in the two patient groups.

These findings have significant impact because patients with gastroparesis and so-called functional disorders of the stomach represent a large component of clinical practice, affecting 10–30% of the population.14 These diagnoses are suspected in patients who present with chronic symptoms (typically exacerbated by a meal) including nausea, vomiting, early satiety/fullness, bloating and epigastric pain in the absence of any other condition that could account for them on routine clinical testing. Traditionally, these disorders have further been classified into one of two categories, based on the results of gastric emptying: gastroparesis (if emptying is delayed) and functional dyspepsia (if emptying is normal). Functional dyspepsia (FD) in turn, has two subtypes: post-prandial distress syndrome (PDS) and epigastric pain (EP) syndrome.

While these classifications have become enshrined with time, it has been apparent that this approach remains unsatisfactory for several reasons, even prior to the current report. First, there is almost complete overlap between the symptoms of gastroparesis and FD of the PDS type.2 Secondly, symptom severity correlates poorly, if at all, with delays in gastric emptying.10 Further, trials with drugs that simply accelerate gastric emptying (“prokinetic” drugs) have generally failed to improve symptoms,15 although a counter-argument has been made recently.16 Third, such a classification has led to a perspective that while gastroparesis is an “organic” disease, FD is not; this has led to significant consequences for patients with FD, who often feel stigmatized or dismissed as having a “psychosomatic disorder” (often loosely interchanged with the term “functional” by many physicians) despite symptoms that can be disabling. In this regard, it is important to note that there were no differences in psychological scores between the two groups at baseline or at 48-weeks. On the other hand, there is considerable evidence to support common pathophysiological mechanisms between the two conditions including impaired gastric accommodation and visceral hypersensitivity.10,17 This has led many experts to consider blurring the distinction between them; as an example, up to a third of European patients diagnosed as FD have delayed gastric emptying, albeit mild.10 Our results reinforce the concept that gastric emptying studies are of limited utility in patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of gastroparesis/functional dyspepsia. However, we realize that this is area of considerable controversy and corroborative studies by other investigators are encouraged to provide validation (or not) of this statement. At the same time, we would like to emphasize that we do believe that both gastroparesis and FD represent neuromuscular disorders of the stomach even if gastric emptying measurements do not capture the pathophysiology adequately. This also raises the question of the effectiveness of so-called “prokinetic” drugs; however, many of these drugs probably have effects on gastric motility beyond acceleration of gastric emptying and therefore may still have a therapeutic role.

This study has several limitations that can inform the interpretation of the results. First, the number of patients on whom full thickness biopsies were performed is small, given the invasive nature of this procedure. In the future, the adoption of endoscopic procedures to obtain such tissue may provide an opportunity for further validation of these findings. It should also be noted that these patients presented with predominant nausea or vomiting, which is a subset of the larger group presenting with upper gastrointestinal symptoms. A second potential criticism of this study is that the patient cohort may be skewed in its phenotype because of the tertiary referral nature of the clinical sites. Thus, it is possible that patients with FD seen at such centers represent a far more severe phenotype than usual. However, just as there may be many “FD” patients in the community with less severe symptoms, there may also proportionately as many patients with “gastroparesis” who have equally mild symptoms. There is therefore no a priori reason to think that these patients with less severe symptoms (with or without delayed gastric emptying) comprise a distinct syndrome, as opposed to occupying a different position on the same spectrum. Nevertheless, we acknowledge this potential bias which can only be settled by performing similar studies on patients that are more representative of those seen in the community. It should also be noted that our findings do not necessarily apply to other forms of secondary gastroparesis such as that seen after fundoplication or Parkinson’s Disease. Finally, we acknowledge that the new Rome IV criteria may have classified these patients differently (e.g., chronic idiopathic nausea, etc.) but regardless of the nomenclature, our results suggest that these patients share common clinical and pathological features with gastroparesis.

In conclusion, our results provide an important and unifying perspective on FD and gastroparesis. We have shown that patients initially classified as one or the other are not distinguishable by clinical features or by follow-up assessment of gastric emptying, which is labile and does not capture the pathophysiological basis of symptoms in these patients. Instead, both disorders are unified by characteristic pathological features, best summarized as a macrophage-driven “cajalopathy” of the stomach. Future improvements in diagnostic ability may reveal subtle differences between these two syndromes but for now it is reasonable to conclude that FD and gastroparesis are part of the same spectrum of pathological (“organic”) gastric neuromuscular dysfunction (GND) as has been previously suggested.18 This has profound implications for our diagnostic and therapeutic approach to these patients and for future directions of research in disease etiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, drug development and therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Ms. Annette Wagoner and Ms. Christine E. Yates, BS, MA for extensive technical support.

† The Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium (GpCRC) is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grants U01DK112193, U01DK112194, U01DK073983, U01DK073975, U01DK074035, U01DK074007, U01DK073974, U01DK073983, U24DK074008) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) (grants UL1TR000424, UL1TR000135).).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests in this study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Pankaj J. Pasricha, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD

Madhusudan Grover, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Katherine P. Yates, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD

Thomas L. Abell, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY

Cheryl E. Bernard, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

Kenneth L. Koch, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC

Richard W McCallum, Texas Tech University, El Paso, TX.

Irene Sarosiek, Texas Tech University, El Paso, TX.

Braden Kuo, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

Robert Bulat, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD.

Jiande Chen, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Robert Shulman, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX.

Linda Lee, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD.

James Tonascia, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD.

Laura A. Miriel, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD

Frank Hamilton, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD.

Gianrico Farrugia, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Henry P. Parkman, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA

References

- 1.Abell TL, Bernstein RK, Cutts T, et al. Treatment of gastroparesis: a multidisciplinary clinical review. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2006;18:263–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasricha PJ, Colvin R, Yates K, et al. Characteristics of patients with chronic unexplained nausea and vomiting and normal gastric emptying. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:567–76 e1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahadeva S, Goh KL. Epidemiology of functional dyspepsia: a global perspective. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:2661–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talley NJ, Holtmann G. Irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia: what can epidemiology tell us about etiology? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;12:633–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasricha PJ, Yates KP, Nguyen L, et al. Outcomes and Factors Associated With Reduced Symptoms in Patients With Gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1762–74 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grover M, Bernard CE, Pasricha PJ, et al. Clinical-histological associations in gastroparesis: results from the Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012;24:531–9, e249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grover M, Farrugia G, Lurken MS, et al. Cellular changes in diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis. Gastroenterology;140:1575–85 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones KL, Russo A, Berry MK, Stevens JE, Wishart JM, Horowitz M. A longitudinal study of gastric emptying and upper gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Med 2002;113:449–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang J, Russo A, Bound M, Rayner CK, Jones KL, Horowitz M. A 25-year longitudinal evaluation of gastric emptying in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012;35:2594–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stanghellini V, Tack J. Gastroparesis: separate entity or just a part of dyspepsia? Gut 2014;63:1972–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desai A, O’Connor M, Neja B, et al. Reproducibility of gastric emptying assessed with scintigraphy in patients with upper GI symptoms. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018;30:e13365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vijayvargiya P, Jameie-Oskooei S, Camilleri M, Chedid V, Erwin PJ, Murad MH. Association between delayed gastric emptying and upper gastrointestinal symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2019;68:804–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angeli TR, Cheng LK, Du P, et al. Loss of Interstitial Cells of Cajal and Patterns of Gastric Dysrhythmia in Patients With Chronic Unexplained Nausea and Vomiting. Gastroenterology 2015;149:56–66 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stanghellini V, Chan FK, Hasler WL, et al. Gastroduodenal Disorders. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1380–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janssen P, Harris MS, Jones M, et al. The relation between symptom improvement and gastric emptying in the treatment of diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1382–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vijayvargiya P, Camilleri M, Chedid V, Mandawat A, Erwin PJ, Murad MH. Effects of Promotility Agents on Gastric Emptying and Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1650–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tack J, Carbone F. Functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2017;33:446–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harer KN, Pasricha PJ. Chronic Unexplained Nausea and Vomiting or Gastric Neuromuscular Dysfunction (GND)? An Update on Nomenclature, Pathophysiology and Treatment, and Relationship to Gastroparesis. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2016;14:410–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.