Abstract

Stressful life events (SLEs) are strongly associated with the emergence of adolescent anxiety and depression, but the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood, especially at the within-person level. We investigated how adolescent social communication (i.e., frequency of calls and texts) following SLEs relates to changes in internalizing symptoms in a multi-timescale intensive year-long study (N=30; n=355 monthly observations; n=~5,000 experience-sampling observations). Within-person increases in SLEs were associated with receiving more calls than usual at both monthly- and momentary-levels, and making more calls at the monthly-level. Increased calls were prospectively associated with worsening internalizing symptoms at the monthly-level only, suggesting that SLEs rapidly influences phone communication patterns, but these communication changes may have a more protracted, cumulative influence on internalizing symptoms. Finally, increased incoming calls prospectively mediated the association between SLEs and anxiety at the monthly-level. We identify adolescent social communication fluctuations as a potential mechanism conferring risk for stress-related internalizing psychopathology.

Keywords: Stress, Phone Communication, Depression, Anxiety, Longitudinal

The prevalence of anxiety and depression disorders increases dramatically across adolescence. Adolescence is characterized by elevated risk for first onset of anxiety or depression (Hankin et al., 1998; Kessler et al., 2005; Paus et al., 2008). The onset of internalizing disorders during adolescence is associated with heightened risk for comorbid disorders, greater functional impairment, and a more severe and disabling course (Fombonne et al., 2001a, 2001b; Pine et al., 1998). Understanding the mechanisms that contribute to this heightened risk for anxiety and depression during adolescence may help to identify targets for early interventions.

Exposure to stressful life events (SLEs) is a well-established risk factor for anxiety and depression (Hammen, 1991, 2005; Kendler et al., 1999; Mazure, 1998; McEwen, 2003; McLaughlin et al., 2012), and adolescence is a time of particular vulnerability following exposure to SLEs. The coupling between stress exposure and negative affect and psychopathology is elevated among adolescents relative to children and adults (Espejo et al., 2007; Grant et al., 2003; Grant, Compas, Thurm, McMahon, & Gipson, 2004; Larson & Ham, 1993; Monroe, Rohde, Seeley, & Lewinsohn, 1999). Stressors that are severe (e.g., childhood trauma; McLaughlin et al., 2012) or chronic (Chaby et al., 2015) are particularly likely to lead to the emergence of anxiety and depression; however, even daily hassles and normative stressors (e.g., peer conflict, the break-up of a romantic relationship) are associated with subsequent increases in anxiety and depression symptoms in adolescents (Hammen, 2005; Jenness et al., 2019; M. Monroe et al., 1999). Although much of this research has utilized cross-sectional designs that examine between-person variables, longitudinal studies have also demonstrated associations of SLEs with subsequent changes in anxiety and depression at the within-person level (Cole et al., 2006; Ge et al., 2001; Hankin, 2008). For example, recent work from our group found that within-person deviations in exposure to stress (i.e., increases relative to one’s own average level of stress exposure) predicted subsequent increases in depression symptoms several months later in adolescents (Jenness et al., 2019). However, the mechanisms underlying this tight temporal coupling of stress with anxiety and depression symptoms remain poorly understood. Greater understanding of these mechanisms is essential to identifying and intervening on processes that confer risk for stress-related psychopathology during adolescence. In the current study, we use an intensive longitudinal design to examine the role of social communication as a potential mechanism linking dynamic fluctuations in SLEs with anxiety and depression symptoms during adolescence.

Adolescents experience dramatic changes in the complexity of their social experiences (Nelson et al., 2005). Compared to children, adolescents spend more time with peers than family (Barnes, Hoffman, Welte, Farrell, & Dintcheff, 2007; Larson, 2001), have less stability in peer relationships (Cairns et al., 1995), and place greater importance on peer relationships (Brown, 1990). The need for social belonging is a fundamental human drive (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), and a lack of social support is associated with elevated risk for many negative outcomes, including anxiety and depression (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2003; Coppersmith et al., 2019; Weeks et al., 1980). This is especially true during adolescence (Somerville, 2013); adolescents exhibit heightened emotional and physiological responses to peer evaluation relative to children or adults (Rodman et al., 2017; Sebastian et al., 2010; Silk et al., 2012; Somerville et al., 2013; Stroud et al., 2009) and social rejection is strongly associated with anxiety and depression symptoms during this period (Prinstein & Aikins, 2004; Williams, 2007).

Given the importance of social relationships and their relation to anxiety and depression during adolescence, it is possible that changes in social behaviors could serve as a mechanism linking SLEs with internalizing psychopathology. Prior work shows that adolescents are more likely to seek social support from peers and parents during times of heightened perceived stress through both traditional (e.g., face-to-face communication; Galaif, Sussman, Chou, & Wills, 2003) and digital means (e.g., online communication; Frison & Eggermont, 2015; Oh, Lauckner, Boehmer, Fewins-Bliss, & Li, 2013). However, the downstream implications of seeking support through digital means are not clear, and existing evidence on whether this type of social engagement is helpful is mixed.

Decades of research have demonstrated that social support mitigates risk for internalizing problems following exposure to stressors (Cohen, 2004; Cohen & Wills, 1985; Herman-Stahl & Petersen, 1996), suggesting that support-seeking behaviors are an adaptive coping response during periods of stress. Indeed, studies have shown that support-seeking behaviors following SLEs are associated with fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression (Clarke, 2006). Adolescents who endorsed seeking out parental and peer social support following SLEs had enhanced life and relationship satisfaction (Saha et al., 2014), and fewer depression symptoms over time (Murberg & Bru, 2005). Additionally, the quality of parental and peer relationships, including the ability to utilize these relationships for support, is a protective factor associated with lower depression symptoms (Coppersmith et al., 2019; Prinstein et al., 2000), particularly following exposure to stress during adolescence (Alto et al., 2018). Thus, social engagement, even through digital means, following SLEs could be associated with reduced subsequent depression and anxiety symptoms.

Social communication through mobile devices (e.g., phone calls and text messaging) has become one of the most important modes of peer communication among adolescents (Lenhart et al., 2010), and prior work finds mixed results concerning its impact on psychological well-being. While some previous work has suggested that frequency of phone communication, even at high intensities, is associated with lower levels of loneliness, stronger relational bonds, increased perceived social support, and fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression (George et al., 2018; Padilla-Walker et al., 2012), others have found that high levels of phone communication may be maladaptive, suggesting this dramatic shift in social communication has rapidly changed the landscape of adolescent social life in ways that may not be fully realized (Murdock, 2013). Indeed, studies have found either no relationship between frequency of phone communication and social closeness among adolescents and young adults (Roser et al., 2016; Thomée et al., 2011) or that sending more texts was actually associated with less fulfilling relationships and conversations (Angster et al., 2010). In addition, high volumes of digital communication have been associated with worse wellbeing and daily functioning (Lister-Landman et al., 2017; Sánchez-Martínez & Otero, 2008), including greater symptoms of depression and anxiety (Coyne et al., 2018, 2019; Redmayne et al., 2013; Roser et al., 2016; Thomée et al., 2011). In fact, one study showed that interpersonal stressors were more strongly associated with emotional distress in young adults who engaged in high levels of texting (Murdock, 2013). Of note, the relationships between phone communication and psychological wellbeing have been examined at a various timescales – with some examining how reported frequency of phone communication relates to wellbeing within the same day (George et al., 2018), and others examining these relationships over the course of months or years (Padilla-Walker et al., 2012; Thomée et al., 2011) – and this may contribute to inconsistent findings. In addition, previous work has suggested that while fluctuations in internalizing symptoms occur on the order of weeks to months (Hammen, 2005; S. M. Monroe & Reid, 2008), the tight coupling between stress and negative affect occurs on a more granular scale (i.e., hours to days) (Larson & Ham, 1993; Sliwinski et al., 2009; Stawski et al., 2008; Zawadzki et al., 2019). Thus, extant evidence is mixed as to the psychological consequences of phone communication intensity, and a greater focus on the impact of within-person fluctuations in frequency of social communication following stress examined at multiple timescales could clarify these relationships.

In addition, the vast majority of previous work examining adolescent communication on mobile devices and internalizing problems is based on subjective estimates of phone use, which are subject to inaccuracies and biases inherent in self-reported behaviors (Aydin et al., 2011; Inyang et al., 2009). More recent work has leveraged technological advancements in passively measuring objective phone behaviors via smart-phones (Sequeira et al., 2019; Torous et al., 2016). While some studies examining individual differences in screen time or social media use find no or minimal effects on wellbeing (Orben & Przybylski, 2019a, 2019b), others using within-person approaches have found links between phone behavior (e.g., screen time and frequency of phone communication) and reported stress levels (Sano et al., 2018), personality characteristics (e.g., extraversion; Harari et al., 2019), and anxiety and depression symptoms (Saeb et al., 2015) using this approach. We extend this work by examining how fluctuations in objectively measured phone communication following SLEs relate to anxiety and depression in an intensive longitudinal design.

In the current study, we aimed to determine whether changes in social communication during periods of high exposure to stressors are a potential candidate mechanism through which SLEs might influence internalizing psychopathology during adolescence. We examined anxiety and depression separately, as they represent distinct subcomponents of internalizing symptoms that may relate to social communication in different ways. For example, it may be the case that anxiety is activating and related to hypervigilant monitoring of social communication, whereas depression is related to withdrawal from social communication. We also employed a combination of both monthly and momentary levels of assessment in order to examine these associations at different timescales. At the monthly level, we examined whether within-person fluctuations in exposure to SLEs were associated with subsequent changes in the frequency of phone communication. In addition, we evaluated whether these fluctuations in the frequency of phone communication were associated with subsequent changes in anxiety and depression symptoms. Finally, we assess whether fluctuations in the frequency of phone communication were a mechanism linking SLEs with anxiety and depression at the within-person level. To examine these associations at a more granular level, we used experience sampling methods (EMA) to assess how associations between perceived stress, phone communication, and reported depressed and anxious affect unfold over the course of a day.

Methods

All code and data are posted to Open Science Framework and can be accessed at https://osf.io/nhfsc/.

Participants

Our sample was designed to examine associations of SLEs, frequency of phone communication, and internalizing symptoms at the within-person level. A sample of 30 female adolescents aged 15–17 participated in a year-long longitudinal study that included 12 in-lab assessments conducted each month (n = 355 monthly assessments) and a total of 12 weeks of ecological momentary assessments (EMA) spread across four waves of three-week periods in which participants reported on stress and affect three times daily (n = nearly 5,000 EMA assessments, see Table 1). Participants were recruited from schools, libraries, public transportation, and other public spaces in the general community in Seattle, WA between April 2016 and April 2018. Inclusion criteria included female sex, aged 15–17 years, possession of a smart phone with a data plan, and English fluency.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and ICCs for each dependent variable

| Dependent variable | N | n | M | SD | Range | Possible Range | ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress | |||||||

| Monthly Level | |||||||

| Stressful Life Events | 30 | 356 | 2.50 | 3.33 | 0 – 19 | N/A | 0.246 |

| Chronic Stress | 30 | 356 | 4.22 | 1.87 | 0 – 8 | 0 – 8 | 0.697 |

| Momentary Level | |||||||

| EMA Stress - Morning | 30 | 1414 | 3.22 | 1.85 | 1 – 7 | 1 – 7 | 0.493 |

| EMA Stress - Afternoon | 30 | 1727 | 3.11 | 1.81 | 1 – 7 | 1 – 7 | 0.454 |

| EMA Stress - Night | 30 | 1740 | 3.07 | 1.84 | 1 – 7 | 1 – 7 | 0.438 |

| Social Behaviors | |||||||

| Monthly Level | |||||||

| Outgoing Calls (per day) | 28 | 294 | 2.15 | 2.21 | 0.05 – 16.68 | N/A | 0.555 |

| Incoming Calls (per day) | 28 | 294 | 1.54 | 1.92 | 0 – 19.6 | N/A | 0.621 |

| Outgoing Texts (per day) | 26 | 268 | 33.04 | 38.18 | 0.11 – 220.59 | N/A | 0.774 |

| Incoming Texts (per day) | 26 | 275 | 39.22 | 42.07 | 0.44 – 245.85 | N/A | 0.724 |

| Momentary Level | |||||||

| Outgoing Calls - Morning | 28 | 3986 | 0.78 | 1.41 | 0 – 22 | N/A | 0.055 |

| Outgoing Calls - Afternoon | 28 | 5266 | 1.41 | 2.04 | 0 – 19 | N/A | 0.108 |

| Outgoing Calls - Night | 28 | 5131 | 1.58 | 2.49 | 0 – 34 | N/A | 0.125 |

| Incoming Calls - Morning | 28 | 3986 | 0.60 | 1.08 | 0 – 27 | N/A | 0.068 |

| Incoming Calls - Afternoon | 28 | 5266 | 0.93 | 1.38 | 0 – 22 | N/A | 0.114 |

| Incoming Calls - Night | 28 | 5131 | 1.11 | 2.29 | 0 – 75 | N/A | 0.126 |

| Outgoing Texts - Morning | 26 | 6267 | 8.89 | 16.27 | 0 – 210 | N/A | 0.388 |

| Outgoing Texts - Afternoon | 26 | 6789 | 11.48 | 17.67 | 0 – 173 | N/A | 0.355 |

| Outgoing Texts - Night | 26 | 6724 | 17.38 | 28.22 | 0 – 308 | N/A | 0.335 |

| Incoming Texts - Morning | 26 | 6267 | 10.84 | 19.90 | 0 – 704 | N/A | 0.258 |

| Incoming Texts - Afternoon | 26 | 6789 | 14.01 | 21.08 | 0 – 407 | N/A | 0.270 |

| Incoming Texts - Night | 26 | 6724 | 21.10 | 32.61 | 0 – 312 | N/A | 0.292 |

| Clinical Symptoms | |||||||

| Monthly Level | |||||||

| Generalized Anxiety (GAD-7) | 30 | 355 | 5.11 | 3.83 | 0 – 14 | 0 – 21 | 0.613 |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 30 | 355 | 5.41 | 4.06 | 0 – 17 | 0 – 27 | 0.630 |

| Momentary Level | |||||||

| EMA Depressed - Morning | 30 | 1418 | 2.18 | 1.59 | 1 – 7 | 1 – 7 | 0.444 |

| EMA Depressed - Afternoon | 30 | 1730 | 2.07 | 1.53 | 1 – 7 | 1 – 7 | 0.371 |

| EMA Depressed - Night | 30 | 1747 | 2.06 | 1.53 | 1 – 7 | 1 – 7 | 0.387 |

| EMA Anxious - Morning | 30 | 1419 | 3.17 | 1.77 | 1 – 7 | 1 – 7 | 0.492 |

| EMA Anxious - Afternoon | 30 | 1732 | 3.07 | 1.80 | 1 – 7 | 1 – 7 | 0.485 |

| EMA Anxious - Night | 30 | 1750 | 2.95 | 1.80 | 1 – 7 | 1 – 7 | 0.462 |

Note: N = number of subjects, n = number of observations, M = mean, SD = standard deviation, ICC = intra-class correlation

We focused on adolescent females in this age range given higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms among adolescent females than males (e.g., Hankin et al., 1998; Lewinsohn et al., 1995), as well as more problematic phone use (Roser et al., 2016). Social communication via mobile phones also appears to peak around this age (Coyne et al., 2018). Our study was well-powered to examine within-person associations between SLEs, frequency of phone communication, and symptoms of anxiety and depression over time, with sufficient power (>80%) to detect small within-person effects (as small as ß = 0.11). See Supplemental Materials and Figure S4 for more information on the simulated power analysis approach.

Participants were excluded based on the following criteria: IQ < 80, active substance dependence, psychosis, presence of pervasive developmental disorders (e.g., autism), MRI ineligibility (e.g. metal implants), psychotropic medication use, active safety concerns, and inability to commit to the year-long study procedure. A total of 18 participants (60%) had experienced a lifetime mood or anxiety disorder assessed at the first monthly visit, and 12 participants (40%) met criteria for an internalizing disorder during the year they participated in the study, assessed at the final monthly visit. Mood and anxiety disorder were assessed using the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS; Kaufman et al., 1997). Twenty-two participants identified as White (73%), 4 as Asian (13%), 2 as Black (7%), and 2 as mixed race (7%). Participants’ income-to-needs ratios were computed based on their parents’ report of total combined household income and household size. Four participants were in families with income below the poverty line (i.e., income-to-needs ratio below 1; 13%), 12 participants between 1–3 (30%), and 13 participants between 3–10 (33%). One participant did not provide income information. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington. Written informed consent was obtained from legal guardians and adolescents provided written assent. Participants were paid increasing amounts of money for each monthly visit, for a total of $905 in possible earnings (Table S1).

Procedures

Monthly-level assessments of stressful life events and internalizing symptoms were administered at each of the 12 monthly visits. This intensive longitudinal design resulted in a total of 360 possible monthly-level observations of stressful life events and symptoms over the study period, with participants attending 355 out of 360 study visits (98.6% completion rate).

Momentary-level assessments measured perceptions of stress, depressed affect, and anxious affect and were collected via smartphone (through the MetricWire app; www.metricwire.com). Momentary-level assessments of perceived stress and affect were collected three times a day, during the morning, afternoon, and evening, for three weeks at four separate times across the year-long study (i.e., a total of 12 weeks of moment-level assessments across four waves). Participants were counterbalanced to receive the first wave either in the first or second month of the study, and subsequent waves occurred during a random month within each quarter of the rest of the year-long study (i.e., approximately every 3 months). Adopting a multi-wave approach to experience sampling aimed to provide broad coverage of participants’ momentary experiences without overburdening them. During experience-sampling periods, participants received three prompts each day in the morning (7:00AM), afternoon (12:00PM), and evening (5:00PM) to complete a short survey about how they felt in that moment. Participants were able to delay surveys for up to 2 hours if they were unable to complete them immediately. Participants responded to nearly 5,000 prompts for each item of perceived stress, depressed affect, and anxious affect (see Table 1).

Unfortunately, a number of issues in the MetricWire (versions 3.1.0 – 3.5.1) tool made it impossible to compute the exact proportion of moment-level assessments that participants completed. Specifically, the software did not consistently record when prompts were sent to participants, making it impossible to know whether a prompt was ignored by the respondent or not actually sent. Although these issues have been resolved in newer versions of the tool, they had not yet been addressed in the version that was available at the time we started the study. While we cannot compute the exact response rate for momentary-level assessments, we can estimate that if all planned prompts had reached participants, they would have a received a maximum of 7,560 prompts. Thus, at the very least, participants completed more than 65% of all possible prompts, despite these technical issues, which is a rate that is at or above standard for this sampling approach (van Roekel et al., 2019).

Assessments

Exposure to Stress.

Monthly-level assessment.

SLEs occurring in the past month were assessed at each study visit using the UCLA Life Stress Interview (Hammen, 1988), a semi-structured interview designed to objectively measure the impact of life events. The interview uses a contextual threat approach for assessing both chronic stress (e.g., ongoing conflict in the home, long-term medical issues) as well as acute life events or episodic stressors (e.g., failing a test, break-up of a romantic relationship). The interview has been extensively validated, adapted for use in adolescents, and considered to be the gold standard for assessing SLEs (Daley et al., 1997; Hammen, 1991). Structured prompts are used to query numerous domains of the child’s life (i.e., peers, parents, household/extended family, neighborhood, school, academic, health, finance, and discrimination). Each episodic stressor is probed to determine timing, duration, severity, and coping resources available. Research personnel objectively coded the severity of each experience for a child of that age and sex on a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (none) to 5 (extremely severe), including half-points. These values were transformed to an integer scale from 0–8 for analyses. Following prior work, a total episodic stress score was computed by taking the sum of the severity scores of all reported events, which reflects both the number and severity of episodic stressors (Hammen et al., 2000), hereafter referred to SLEs. If the participant did not report any SLEs, they received a score of zero for that month. The interview was administered at each monthly visit to assess SLEs occurring since the previous visit. See Table 1 and Figure S1. Though analyses focus on the effect of all types of SLEs on social communication and psychopathology, we provide supplemental analyses examining the effect of interpersonal SLEs and chronic stress on these outcomes reported in Supplemental Materials (Tables S2 and S10).

Momentary-level assessment.

When prompted by the MetricWire app, participants responded to questions assessing stress in the current moment. In each prompt, stress was defined for participants in the statement: “Stress is a situation where a person feels upset because of something that happened unexpectedly or when they are unable to control important things in their life.” Participants then responded to the question “do you feel this kind of stress right now?” on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very stressed).

Internalizing psychopathology.

Monthly-level assessment.

Generalized anxiety symptoms were measured at each study visit with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale, which assesses anxiety symptoms occurring in the last 2 weeks. Seven items are scored on a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. The GAD-7 has good reliability and validity (Spitzer et al., 2006) and demonstrated good internal consistency across all time points in the current study (α=.80−.90; Table 1, Figure S2).

Depression symptoms were measured at each study visit with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scale, which assesses depression symptoms occurring in the last 2 weeks. Nine items are scored on a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. The PHQ-9 has good reliability and validity (Kroenke et al., 2001) and good internal consistency across all time points in the current study (α=.76−.90; Table 1, Figure S2).

Momentary-level assessment.

At each MetricWire prompt, participants also rated their current feelings of depression and anxiety by responding to the questions “how depressed do you feel right now?” and “how anxious do you feel right now?” on 7-point scales (1 = not at all, 7 = very depressed/anxious). Depression and anxiety were not defined for participants, allowing this measure to capture idiosyncratic conceptualizations of these states.

Phone communication.

Continuous, passive monitoring of phone communication occurred on mobile devices throughout the study period using an app (i.e., iMazing for iPhone and SMS Call & Log Backup for Android) that downloaded incoming and outgoing phone call and text message logs. Phone call and text activity since the previous visit were downloaded each month. All identifying information was immediately removed from these logs using a custom script. We quantified the number and length of incoming and outgoing communications. At the monthly level of analysis, summaries of calls and texts were aggregated per month and converted into daily averages of phone and text communication to account for differences in the lag time between monthly visits across participants (Table 1, Figure S3). Secondary analyses examining duration of calls and text messages are included in Supplementary Materials. At the momentary level of analysis, summaries of calls and texts were aggregated over morning (7:00AM–12:00PM), afternoon (12:00PM–5:00PM), or evening (5:00PM–12:00AM) epochs of the day to parallel the timing of experience sampling surveys.

Statistical Analysis

Overall, analyses focused on evaluating the role that fluctuations in the frequency of social communication might play as a mechanism linking experiences of stress with internalizing symptoms. To do so, we estimated models designed to disaggregate between-person and within-person effects over the course of the year. First, we evaluated these within-person effects at the monthly level while controlling for between-person effects for the following associations: 1) SLEs and internalizing symptoms; 2) SLEs and frequency of social communication (i.e., number of phone calls and text messages); 3) frequency of social communication and internalizing symptoms. Finally, we performed a mediation analysis to evaluate whether fluctuations in the frequency of social communication might serve as a mechanism prospectively linking SLEs with internalizing symptoms. We undertook additional analyses examining these prospective relationships at the momentary-level by examining whether reported stress earlier in the day predicted changes in phone communication later in the day, and whether these fluctuations in phone communication were associated with subsequent depressed or anxious affect.

All regression and mediation analyses were carried out in a Bayesian framework, due to its flexibility in computing models with varied specifications, including a within-person mediation analysis, and intuitive interpretation of the 95% highest posterior density (HPD) credible interval (CR), which signifies a 95% probability of the true population parameter being within the interval. We conducted Bayesian hierarchical linear models with unit of time (i.e., study month or day) nested within subject, with a random intercept allowed to vary across subjects. All models included study month (for monthly-level analyses) or day (for momentary-level analyses) and school status (i.e., months or days dummy coded for in school vs. out of school for summer or weekends) as nuisance covariates. Models were estimated in R 3.5.2 (R Core Team, 2019) using the Stan language (Stan Development Team, 2018) and the brms (Bürkner, 2017) and sjstats packages (Lüdecke, 2019). Weakly informative priors specifying a Gaussian distribution (M=0, SD=10) were used to represent our diffuse prior knowledge of the fixed and random effects (see Supplemental Materials for more information about model specification and Table S3 for complementary analyses). For each parameter, we sampled from 4 stationary Markov chains that approximated the posterior distribution using the Monte Carlo No U-Turn Sampler (Hoffman & Gelman, 2014). Each Markov chain comprised 15,000 sampling iterations, including a burn-in period of 2,500 iterations, which were discarded. Convergence of the 4 chains to a single stationary distribution was assessed via the Gelman-Rubin convergence statistic (Gelman & Rubin, 1992). Highest posterior density 95% CR for all parameters were then calculated from these samples and carried forward for inference, wherein CR that did not contain zero were considered statistically significant.

To dissociate between- and within-person effects of predictors of interest in monthly-level analyses, we used within-individual centering (i.e., centering each participant’s observations at the monthly level around their person-specific mean across the year-long study period) and between-subject centering at the year level (i.e., centering each participant’s mean level for the entire study period relative to the overall mean for the entire sample). Both within and between person terms were included in all models at the same time. This approach orthogonalizes variation in a given predictor into between- and within-person variability (Enders & Tofighi, 2007), accounting for the dependent nature of the data both over time and within-subject, while controlling for trait-level characteristics of each predictor. When assessing within-person effects at the monthly level, we computed both concurrent and lagged-analysis models to assess for prospective relationships.

In momentary-level analyses, a slightly different approach was taken to constrain analyses to relationships within-day, examining associations from morning to afternoon and afternoon to evening, but not evening to the following morning. In addition, given the structure of the school day, it is possible that these relationships differ across the span of a day. Thus, we first examined the association of morning predictors (i.e., stress, frequency of phone communication) on afternoon outcomes (i.e., frequency of phone communication, depressed and anxious affect), controlling for between-person effects (i.e., the average trait-level of the predictor across the year) and morning level of outcome. The same procedure was repeated for afternoon predictors on evening outcomes. At the momentary level, within-person effects were computed for lagged-analyses only, given the inherently staggered nature of experience sampling surveys and aggregated phone communication values.

Multi-level within person mediation models were estimated when significant associations were found between the predictor and the putative mediator, and between the mediator and outcome. Mediation models were computed with predictor, mediator, and outcomes all measured at the within-person level (i.e., a Level 1-1-1 mediation), by combining coefficients from two separate Bayesian hierarchical models using the same approach described above for the regression models. The first model, from predictor to mediator, yielded an estimate of the coefficient for the proximal indirect path (a), while the second model, with the dependent variable regressed on the predictor and mediator, yielded coefficients for the distal indirect path (b) and the direct path (c’). Coefficients from the a and b paths were multiplied to calculate the indirect effect and this in turn was divided by the total effect (indirect + c’) to quantify the proportion of variance mediated. Highest posterior density 95% CR were then calculated from these samples for the indirect effect and proportion of variance mediated and used to determine statistical significance. Only relationships at the monthly-level satisfied the requirements to compute a mediation model, thus mediation model analyses were restricted to monthly-level relationships. All code and data are posted to Open Science Framework and can be accessed at https://osf.io/3amdg.

Results

SLEs and Internalizing Symptoms

When examining relationships at the monthly level, Bayesian hierarchical models revealed significant associations between SLEs and internalizing symptoms (Table 2). Within-person fluctuations in SLEs were significantly associated with increases in anxiety symptoms in the same month, but not the following month. Meanwhile, increases in SLEs were not concurrently associated with depression symptoms in the same month, but predicted worsening depression symptoms the following month (Figure 1, A–B).

Table 2.

Bayesian hierarchical model outcomes at monthly and momentary levels

| Monthly Level | Within-person effects (concurrent) | Within-person effects (lagged) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | B | SE | 95% CR | B | SE | 95% CR |

| Stressful Life Events predicting | ||||||

| Generalized Anxiety (GAD-7) | 0.133 | 0.045 | [0.047, 0.221] | 0.027 | 0.049 | [−0.069,0.121] |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 0.088 | 0.048 | [−0.001,0.186] | 0.129 | 0.051 | [0.028, 0.227] |

| Stressful Life Events predicting | ||||||

| Outgoing Calls | 0.142 | 0.031 | [0.080, 0.201] | 0.105 | 0.031 | [0.040, 0.164] |

| Incoming Calls | 0.077 | 0.025 | [0.024, 0.122] | 0.069 | 0.026 | [0.016, 0.119] |

| Outgoing Texts | 0.257 | 0.410 | [−0.546, 1.038] | 0.031 | 0.427 | [−0.789, 0.874] |

| Incoming Texts | 0.473 | 0.489 | [−0.502, 1.415] | 0.261 | 0.492 | [−0.725, 1.205] |

| Outgoing Calls predicting | ||||||

| Generalized Anxiety (GAD-7) | 0.238 | 0.096 | [0.048, 0.427] | 0.150 | 0.098 | [−0.044, 0.341] |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 0.228 | 0.101 | [0.034, 0.425] | 0.099 | 0.102 | [−0.101,0.300] |

| Incoming Calls predicting | ||||||

| Generalized Anxiety (GAD-7) | 0.293 | 0.118 | [0.055, 0.520] | 0.452 | 0.126 | [0.198, 0.696] |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 0.244 | 0.122 | [−0.002, 0.483] | 0.204 | 0.132 | [−0.062, 0.464] |

| Outgoing Texts predicting | ||||||

| Generalized Anxiety (GAD-7) | 0.013 | 0.008 | [−0.004, 0.029] | 0.012 | 0.010 | [−0.007, 0.032] |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 0.013 | 0.009 | [−0.003, 0.031] | 0.002 | 0.010 | [−0.017,0.021] |

| Incoming Texts predicting | ||||||

| Generalized Anxiety (GAD-7) | 0.010 | 0.007 | [−0.003, 0.023] | 0.008 | 0.008 | [−0.007, 0.024] |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 0.015 | 0.007 | [0.001, 0.029] | 0.005 | 0.008 | [−0.011,0.019] |

| Momentary Level | Morning → afternoon (lagged) | Afternoon → evening (lagged) | ||||

| Model | B | SE | 95% CR | B | SE | 95% CR |

| EMA Stress predicting | ||||||

| EMA Anxiety | 0.135 | 0.032 | [0.073, 0.195] | 0.159 | 0.029 | [0.100, 0.215] |

| EMA Depression | 0.048 | 0.024 | [0.003, 0.100] | 0.063 | 0.025 | [0.015, 0.111] |

| EMA Stress predicting | ||||||

| Outgoing Calls | −0.002 | 0.036 | [−0.074, 0.066] | 0.003 | 0.031 | [−0.055, 0.065] |

| Incoming Calls | 0.047 | 0.022 | [0.005, 0.087] | 0.007 | 0.048 | [−0.081,0.100] |

| Outgoing Texts | −0.181 | 0.344 | [−0.870, 0.467] | −0.274 | 0.450 | [−1.214,0.573] |

| Incoming Texts | −0.185 | 0.393 | [−0.980, 0.559] | −0.304 | 0.506 | [−1.258,0.672] |

| Outgoing Calls predicting | ||||||

| EMA Anxiety | 0.067 | 0.044 | [−0.017,0.160] | −0.018 | 0.024 | [−0.065, 0.027] |

| EMA Depression | 0.027 | 0.035 | [−0.046, 0.096] | 0.008 | 0.019 | [−0.029, 0.043] |

| Incoming Calls predicting | ||||||

| EMA Anxiety | 0.026 | 0.054 | [−0.076,0.135] | −0.043 | 0.040 | [−0.122,0.034] |

| EMA Depression | −0.040 | 0.043 | [−0.120,0.042] | −0.061 | 0.033 | [−0.127,0.002] |

| Outgoing Texts predicting | ||||||

| EMA Anxiety | 0.002 | 0.004 | [−0.005, 0.008] | 0.000 | 0.003 | [−0.005, 0.006] |

| EMA Depression | 0.001 | 0.003 | [−0.005, 0.006] | 0.002 | 0.002 | [−0.003, 0.006] |

| Incoming Texts predicting | ||||||

| EMA Anxiety | 0.002 | 0.003 | [−0.005, 0.008] | 0.002 | 0.003 | [−0.003, 0.007] |

| EMA Depression | 0.002 | 0.003 | [−0.004, 0.007] | 0.001 | 0.002 | [−0.003, 0.005] |

Note: Statistics reflect outcome of within-person effects. B = unstandardized coefficient; SE = standard error of coefficient; CR = 95% credible interval (15,000 samples); Bold denotes significant effect.

Figure 1.

Relationships between SLEs, phone communication and internalizing symptoms at the monthly level. A. Within-person fluctuations in SLEs were positively associated with concurrent symptoms of anxiety (A) and subsequent symptoms of depression the following month (B). Within-person fluctuations in SLEs were positively associated with number of outgoing (C) and incoming phone calls (D) during the same month. A-D: X-axis reflects within-person mean-centered SLEs, and y-axis reflects raw sum score of anxiety (A) and depression (B) or daily average of outgoing (C) and incoming phone calls (D). Within-person fluctuations in number of outgoing calls were positively associated with symptoms of anxiety (E) and depression (F) during the same month, while fluctuations in number of incoming calls were positively associated with symptoms of anxiety during the same month and the following month (G). Fluctuations in number of incoming texts were positively associated with symptoms of depression during the same month (H). E-H: X-axis reflects within-person mean-centered daily averages of phone communication, and y-axis reflects raw sum scores of anxiety and depression symptoms. Black line with shading indicates estimated effect from Bayesian hierarchical model with 95% CR (15,000 samples).

At the momentary level, within-person fluctuations in reports of morning stress significantly predicted depressed and anxious affect in the afternoon, while controlling for between-person differences in perceived stress and morning levels of depressed and anxious affect. The same pattern was found when examining the association of afternoon perceived stress with evening depressed and anxious affect (Table 2).

SLEs and Phone Communication

At the monthly level, SLEs were consistently associated with the frequency of phone call behaviors (Table 2). Within-person increases in SLEs were associated with making and receiving more phone calls than normal during the same month, and these relationships extended into the following month (Figure 1, C–D). SLEs were not associated with frequency of sending or receiving text messages, neither concurrently nor in the following month.

When examining these relationships at the momentary level, reports of greater morning stress than usual predicted an increase in incoming calls in the afternoon, while controlling for between-person levels of perceived stress and incoming calls in the morning. This relationship was not significant when examining afternoon stress to evening incoming calls. Momentary stress did not significantly predict changes in frequency of outgoing calls or texts (Table 2).

Phone Communication and Internalizing Symptoms

At the monthly level, within-person fluctuations in the frequency of phone communication were also related to changes in internalizing symptoms (Table 2). When adolescents made more phone calls than usual, they reported experiencing greater symptoms of anxiety and depression during the same month. When adolescents received more phone calls than normal, they reported more symptoms of anxiety during the same month and the following month. Finally, adolescents that received more text messages than normal reported an increase in depression symptoms during the same month, but not the following month (Figure 1, E–H).

When examining these relationships at the momentary level, frequency of phone communication earlier in the day was not associated with depressed or anxious affect later in the day (Table 2).

Social Behaviors as a Mediator of Stress and Internalizing Symptoms

When examining the relationships between SLEs, frequency of phone communication, and internalizing symptoms at the within-person level, significant associations across each arm of the indirect path (i.e., SLEs to phone communication; phone communication to internalizing symptoms) emerged at the monthly-level only. Below, we report the median estimate (to account for skew) of the indirect effect and proportion mediated with 95% CR. See Table S4 in the Supplement for full statistical results of all mediation models tested.

We determined whether within-person fluctuations in the frequency of phone communication mediated the relationship between stress and internalizing symptoms during the same month (concurrent mediation). We found that fluctuations in number of outgoing calls significantly mediated the within-person relationship between SLEs and depression during the same month, accounting for 42.68% of the total effect of this relationship (Figure 2A). By contrast, neither fluctuations in number of outgoing nor incoming calls mediated the within-person relationship between SLEs and anxiety symptoms in the same month (Table S4).

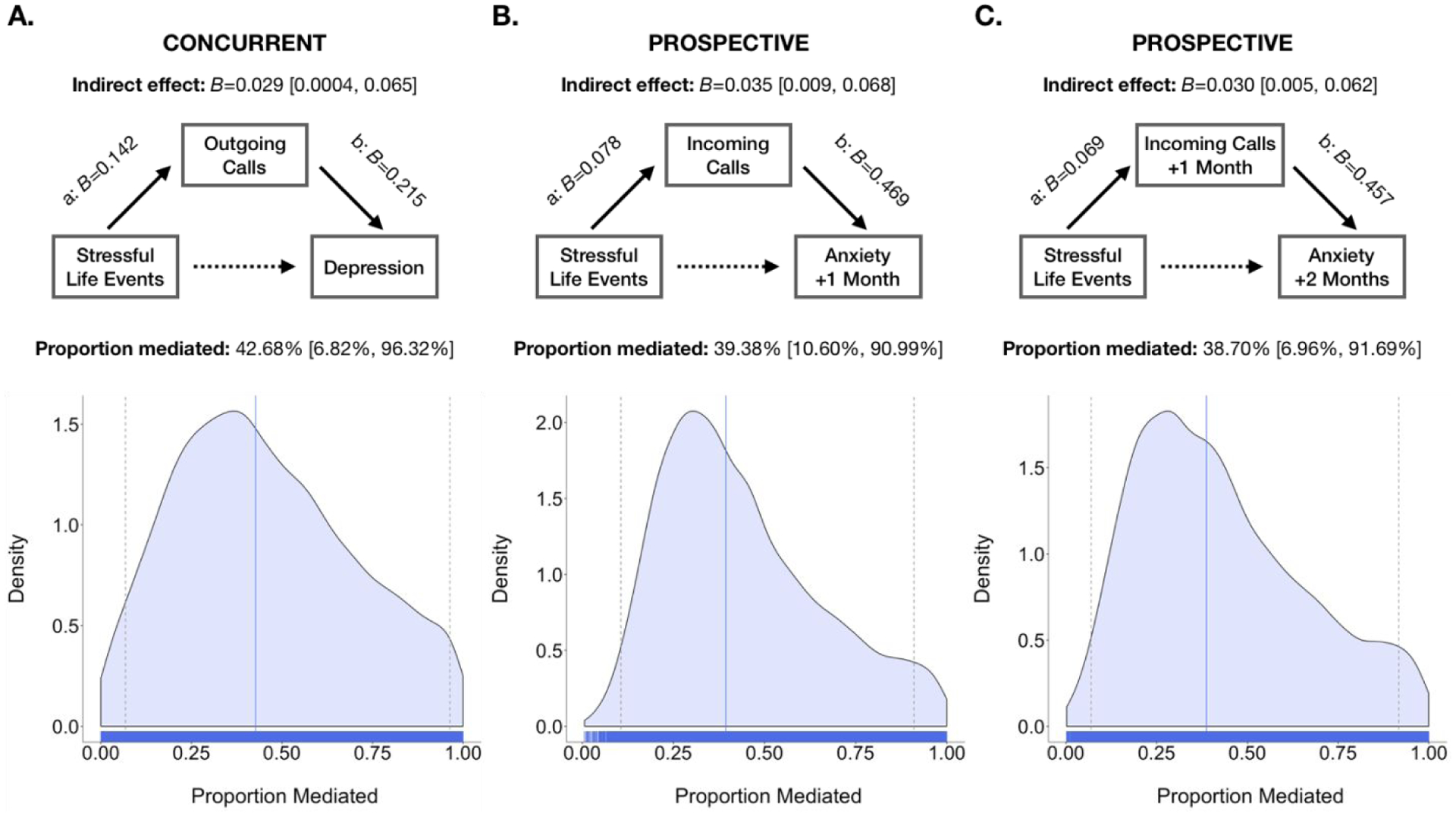

Figure 2.

Within person fluctuations in number of phone call mediates the relationship between changes in stress and depression and anxiety symptoms. Changes in number of outgoing phone calls mediated the relationship between SLEs and concurrent symptoms of depression (A). Within-person fluctuations in number of incoming phone calls mediated the relationships between stressful live events and subsequent symptoms of anxiety (B) and previous SLEs and subsequent symptoms of anxiety (C). Figures show Bayesian mediation model results and 95% HPD CR displayed in brackets (15,000 samples). Density and rug plots display the posterior density of the estimated proportion mediated (blue line indicates median estimate; gray dashed lines indicate 95% CR).

Next, we examined whether within-person fluctuations in the frequency of phone communication mediated the prospective association between within-person deviations in stress and changes in internalizing symptoms the following month (prospective mediation). Fluctuations in number of incoming calls significantly mediated the relationship between changes in SLEs and subsequent anxiety symptoms the following month, accounting for 39.38% of the total effect of this relationship (Figure 2B). When also lagging the relationship between stress and incoming calls, we found that the number of incoming calls significantly mediated 38.70% of the total effect of the relationship between previous month’s SLEs and the following month’s changes in anxiety symptoms (Figure 2C). This prospective association suggests that there may be a sequential relationship to these factors, wherein stress may stir up an influx of phone communication that may drive worsening anxiety symptoms. While the current study cannot speak to the exact nature of this influx in phone calls, secondary analyses aimed at understanding its correlates suggest that within-person fluctuations in co-rumination may play a role in these outcomes (Supplemental Materials, Table S5).

Discussion

Understanding the mechanisms that explain how SLEs foment internalizing symptoms during adolescence is crucial for early intervention and prevention efforts. Given the dramatic shifts in social experiences that occur during adolescence, we examined social communication as a potential mechanism linking stressors to internalizing psychopathology in adolescent females by objectively characterizing the frequency of phone calls and text messaging. Examination of these relationships at multiple timescales in an intensive longitudinal design positioned us to isolate within-person fluctuations to determine how these associations unfolded dynamically over time. This approach revealed robust associations between within-person fluctuations in SLEs and frequency of phone communication. Specifically, when adolescents experienced more stressors than was typical for them, they made and received more phone calls during the same month and the following month. The relationship between perceived stress and subsequent changes in incoming calls was also observed at the momentary-level. These changes in social communication were related to fluctuations in internalizing symptoms, but not momentary affect, such that months characterized by greater frequency of phone and text communication than usual were associated with within-person increases in both current and future anxiety or depression symptoms. Finally, mediation analyses showed that increases in incoming phone calls accounted for a significant proportion of the prospective within-person relationship between stress and subsequent anxiety symptoms the following month.

Given that evidence linking psychological wellbeing and phone communication is mixed (George et al., 2018; Murdock, 2013; Padilla-Walker et al., 2012; Roser et al., 2016), we sought to clarify this relationship using an intensive longitudinal design that capitalizes on the ability to passively collect actual frequency of phone communication. This approach afforded the ability to examine the sequential unfolding of the relationships between stressors, phone communication, and internalizing symptoms at multiple timescales over a year, while using multi-modal approaches of gathering data to reduce shared variance in measurement (i.e., standardized interview, passive digital monitoring, and subjective report). With these advancements, we provide evidence suggesting that within-person fluctuations in SLEs are associated with changes in the frequency of phone communication that, in turn, are associated with anxiety and depression symptoms concurrently and prospectively. In contrast, the duration of calls and length of text messages were not significantly related to stressors or psychopathology, with the exception of outgoing call length, whereby a weak, positive relationship was related to concurrent symptoms of depression. Thus, frequency of communication remains the metric of social communication that is associated with psychopathology following stress. Greater research is needed to identify the mechanisms through which stressors relate specifically to the frequency of social communication; these could include increases in rumination and worry (e.g., Michl et al., 2013), reassurance seeking (Joiner et al., 1999), and desire for social support that occur following stressful life events. Contrary to the notion that enhanced social engagement would universally buffer adolescents from the harmful effects of stress, these findings highlight the potential negative consequences of certain forms of social communication during adolescence, particularly during periods characterized by greater levels of stress.

The consequences of social engagement may depend on both the nature of support-seeking behavior and whether it is met with a supportive response (Frison & Eggermont, 2015). A variety of social responses to stress can be maladaptive, including reassurance-seeking and corumination. Reassurance-seeking involves repeatedly soliciting confirmation of positive standing from others, that over time can lead to a deterioration of relationships and worsening of internalizing symptoms (Joiner et al., 1999; Potthoff et al., 1995; Prinstein et al., 2005). Corumination is characterized as dwelling on problems in conversation with others; although this tendency strengthens social bonds, it also predicts worsening symptoms of anxiety and depression in adolescents (Rose, 2002; Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2012). In addition, while not measurable in this study, the extent to which support-seeking behaviors are actually met with an empathic response can mitigate or increase risk for stress-related internalizing symptoms (Frison & Eggermont, 2015). Thus, certain kinds of social engagement following stressors could exacerbate risk for subsequent psychopathology.

When characterizing monthly within-person fluctuations in SLEs, social communication, and symptoms of anxiety and depression over the course of a year, we replicate prior findings by demonstrating that within-person fluctuations in exposure to stress—measured using a gold-standard interview-based approach—were concurrently and prospectively associated with changes in internalizing symptoms (Jenness et al., 2019). We extend this literature by showing this relationship on both the monthly and momentary level of assessment, and reaffirm that these deleterious effects of stress on mental health motivate additional research on the mechanisms underlying this connection.

We also found that when adolescents experienced more SLEs than was normal for them, they engaged in more phone calls during the same month and the following month, a pattern that also emerged at the momentary-level for incoming calls, suggesting a rapid coupling between stress and phone communication. A similar pattern was found for interpersonal stressors and phone communication, wherein greater interpersonal stress was associated with higher frequency of phone call, but not text message communication. Chronic stress was also similarly positively related to number of phone calls; however, chronic stress was also associated with reduced frequency of incoming text messages during the same month (Table S2). This dissociation may be explained by the different relational purposes of phone calls and text messages serve. While adolescents typically reserve conversations with parents and discussions about major life events for phone conversations (Madell & Muncer, 2007), text messaging among adolescents is used to maintain and reinforce existing bonds with close friends (Blair et al., 2015; Bryant et al., 2006). It is possible that during times of more severe or ongoing stress, adolescents pull for more substantive social support by way of phone calls, while reducing engagement in text messages that serve a relational maintenance function and reflect more superficial communication.

In order to evaluate whether these responses to stress were adaptive or maladaptive, we examined how fluctuations in the frequency of social communication related to symptoms of anxiety or depression. While not associated with momentary affect at a more granular time scale, analyses at the monthly level show that making more phone calls than was usual was associated with increased symptoms of anxiety and depression during the same month, and greater incoming calls than usual was both concurrently and prospectively associated with worsening anxiety the following month. Moreover, receiving more phone calls following exposure to stressors accounted for a significant proportion of the prospective relationship between within-person increases in SLEs and subsequent anxiety symptoms. The longitudinal nature of these data allow us to draw inferences about the directionality of these relationships (Maxwell & Cole, 2007), which suggest that an influx of phone calls following SLEs may drive subsequent worsening symptoms of anxiety. The dissociation in findings based on time-scale may clarify the temporal dynamics of how phone communication impacts well-being over time. Specifically, while within-day changes in phone communication were not significantly associated with depressed or anxious affect, the associations of increased phone communication on depression and anxiety symptoms may arise more gradually with an accumulation of increased communication, given than a time frame of weeks to months is more relevant to symptom development and disorder onset (Hammen, 2005; Kendler et al., 1999). This general pattern extends previous work showing that young adults that are high-volume texters demonstrated stronger coupling between stress and internalizing symptoms (Murdock, 2013), by using a within-subjects mediation design in adolescents rather than a cross-sectional moderation design. Together, these findings suggest that within-person fluctuations in the frequency of social communication may be a potential mechanism linking stressors with internalizing symptoms. These findings may point to high intensity phone communication relative to one’s baseline as indicative of a marker of risk for psychopathology following exposure to stress.

Although increases in both making and receiving calls was associated with SLEs and concurrent anxiety and depression symptoms, only increases in the number of incoming calls was prospectively linked to worsening of anxiety the following month. This pattern was not observed for outgoing calls, which raises some interesting possible explanations. The influx in incoming calls could reflect a response from maladaptive social behaviors following stress. While unlikely to be explained by reassurance-seeking behavior, which can erode relationships and result in less social engagement from others (Potthoff et al., 1995), co-rumination is one potential explanation for this pattern. To test this possibility, we examined whether within-person fluctuations in self-reported co-rumination was associated with SLEs, phone communication, or internalizing psychopathology (see Supplemental Materials and Table S5). We found that within-person increases in reported co-rumination were associated with greater frequency of incoming phone calls that same month and, consistent with prior work (Rose, 2002), worsening internalizing symptoms in the same month and the following month. While not associated with SLEs, co-rumination may be a contributing factor that could help explain why increases in incoming phone calls following stress led to worsening symptoms of anxiety. Tracking of social communication, captured here by frequency of phone calls and text messages, could represent a stress-related marker of clinical risk that reflects complex social and psychological factors, that may include co-ruminative behaviors. Another possible explanation for the particularly strong link between incoming calls and subsequent anxiety is that the calls themselves involve stressful interpersonal interactions, such as conflict with peers, bullying, or increased monitoring from parents. While the current study was not designed to examine these questions, future work should attempt to determine whether phone communication is with parents or peers and, taking a step further, introduce content analysis (e.g., from text messages) to extract the nature of the communication. While informative, we have restricted our analyses to frequency of communication, as content analysis pushes the boundaries of ethics and protection of privacy (Jacobson et al., 2020).

Taken together, these findings suggest that social behaviors, such as frequency of phone communication, is a marker of risk for psychopathology following stress, and may serve as a mechanism linking the two. However, the current research should be considered in light of its limitations. The interpretation of changes in the frequency of social communication is limited in that it is unknown whether communication is with a peer or parent, and this relationship type influences communication method and support seeking behavior (Blair et al., 2015; Bryant et al., 2006; Madell & Muncer, 2007). Moreover, perceived social support from parents as compared to peers during adolescence could differentially impact risk for depression (Stice et al., 2004). Future work should identify whether the social communication driving the link between stress and psychopathology is primarily explained by communication with peers or parents. Additionally, the scope of social communication here is limited to frequency of phone calls and text messages, though communication may also be taking place in person or via other social media platforms popular among adolescents, such as WhatsApp, SnapChat, and Instagram. Future work should aim to isolate the unique contribution of phone communication to the current finings, as compared to changes in general phone usage (e.g., screen time) or general sociability (e.g., face-to-face communication). Furthermore, as discussed, the current analyses are limited to a sample of thirty adolescent females, which limits the generalizability of the current study. While the sample size is restricted due to the intensive longitudinal nature of the study design, the sample includes community members that are representative for a wide range of socioeconomic status and risk for psychopathology (see Methods). The focus on females was chosen by design to reduce interindividual variability and capitalize on a group that is at particularly high risk for problematic phone use and internalizing problems (Hankin et al., 1998; Lewinsohn et al., 1995; Roser et al., 2016). However, future work should aim to generalize these findings to a larger sample including males and investigate any gender-specific effects. Finally, analytical approaches used in the current work should be leveraged to identify intervention points based on how frequency of social communication can confer risk or resilience to psychopathology following stress (Nahum-Shani et al., 2018).

The current research suggests that increases in social communication using mobile devices relative to adolescents’ average usage could portend negative consequences for adolescents. These findings do not necessarily suggest that adolescents should not communicate with others following stressful events, but rather it may be important to consider the nature of that communication. In addition to the intense and constant attunement to potential communication and the accompanying anxiety associated with phone separation (Skierkowski & Wood, 2012), some electronic communication may lead to more opportunities for stress (Weinstein & Selman, 2016), including greater potential for misunderstanding (Coyne et al., 2011) or embolden more negative treatment or bullying (Jones et al., 2013). Furthermore, some cell phone users exhibit compulsive behaviors termed ‘problematic cell phone use’ (Billieux, 2012), which can lead to dysfunction (e.g., not completing expected demands), stress and symptoms of anxiety and depression in both adolescents and adults (Coyne et al., 2018, 2019; Lister-Landman et al., 2017; Murdock, 2013; Redmayne et al., 2013; Roser et al., 2016; Thomée et al., 2011). Thus, it is important to closely examine social behaviors in the form of phone communication as a mechanism through which SLEs might contribute to internalizing problems in adolescents. Whether these findings extend to other domains of functioning, like relationship quality, risk behaviors, and substance use, is an important goal for future research.

Conclusion

Although SLEs are a known risk factor for symptoms of depression and anxiety, the mechanisms underlying this tight temporal coupling remain poorly understood. Here, we used an intensive longitudinal design and leveraged digital phenotyping methods to understand how dynamic changes in social behaviors following exposure to SLEs relate to the emergence of internalizing symptoms at multiple timescales. We find that within-person fluctuations in the frequency of social communication statistically explain the prospective link between stressful life events and anxiety symptoms. This work provides evidence for one pathway by which stressors can lead to worsening of internalizing symptoms and identifies frequency of social communication as a social process that confers risk for psychopathology following exposure to SLEs. Identifying mechanisms of risk using smartphone technology will allow for future innovation in how, when, and with whom to intervene and mitigate risk for stress-related psychopathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R56-119194) to KAM, a One Mind Institute Rising Star Award to KAM, a Jacobs Foundation Early Career Research Fellowship to KAM.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alto M, Handley E, Rogosch F, Cicchetti D, & Toth S (2018). Maternal relationship quality and peer social acceptance as mediators between child maltreatment and adolescent depressive symptoms: Gender differences. Journal of Adolescence, 63, 19–28. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angster A, Frank M, & Lester D (2010). An Exploratory Study of Students’ Use of Cell Phones, Texting, and Social Networking Sites. Psychological Reports, 107(2), 402–404. 10.2466/17.PR0.107.5.402-404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin D, Feychting M, Schüz J, Andersen TV, Poulsen AH, Prochazka M, Klæboe L, Kuehni CE, Tynes T, & Röösli M (2011). Predictors and overestimation of recalled mobile phone use among children and adolescents. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology, 107(3), 356–361. 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2011.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Hoffman JH, Welte JW, Farrell MP, & Dintcheff BA (2007). Adolescents’ time use: Effects on substance use, delinquency and sexual activity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(5), 697–710. 10.1007/s10964-006-9075-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, & Leary MR (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billieux J (2012). Problematic Use of the Mobile Phone: A Literature Review and a Pathways Model. Current Psychiatry Reviews, 8(4), 299–307. 10.2174/157340012803520522 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blair BL, Fletcher AC, & Gaskin ER (2015). Cell Phone Decision Making: Adolescents’ Perceptions of How and Why They Make the Choice to Text or Call. Youth & Society, 47(3), 395–411. 10.1177/0044118X13499594 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB (1990). Peer groups and peer cultures. In Feldman SS & Elliott GR (Eds.), At the threshold: The developing adolescent (pp. 171–196). Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant JA, Sanders-Jackson A, & Smallwood AMK (2006). IMing, Text Messaging, and Adolescent Social Networks. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(2), 577–592. 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00028.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bürkner P-C (2017). brms: An R Package for Bayesian Multilevel Models Using Stan. Journal of Statistical Software, 80(1). 10.18637/jss.v080.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, & Hawkley LC (2003). Social Isolation and Health, with an Emphasis on Underlying Mechanisms. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 46(3), S39–S52. 10.1353/pbm.2003.0063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Leung M-C, Buchanan L, & Cairns BD (1995). Friendships and Social Networks in Childhood and Adolescence: Fluidity, Reliability, and Interrelations. Child Development, 66(5), 1330–1345. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00938.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaby LE, Cavigelli SA, Hirrlinger AM, Caruso MJ, & Braithwaite VA (2015). Chronic unpredictable stress during adolescence causes long-term anxiety. Behavioural Brain Research, 278, 492–495. 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AT (2006). Coping with Interpersonal Stress and Psychosocial Health Among Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(1), 10–23. 10.1007/s10964-005-9001-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S (2004). Social Relationships and Health. American Psychologist, 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Wills TA (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus J, & Paul G (2006). Stress exposure and stress generation in child and adolescent depression: A latent trait-state-error approach to longitudinal analyses. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(1), 40–51. 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppersmith DDL, Kleiman EM, Glenn CR, Millner AJ, & Nock MK (2019). The dynamics of social support among suicide attempters: A smartphone-based daily diary study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 120, 103348. 10.1016/j.brat.2018.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne SM, Padilla-Walker LM, & Holmgren HG (2018). A Six-Year Longitudinal Study of Texting Trajectories During Adolescence. Child Development, 89(1), 58–65. 10.1111/cdev.12823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne SM, Stockdale L, & Summers K (2019). Problematic cell phone use, depression, anxiety, and self-regulation: Evidence from a three year longitudinal study from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Computers in Human Behavior, 96, 78–84. 10.1016/j.chb.2019.02.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daley SE, Hammen C, Burge D, Davila J, Paley B, Lindberg N, & Herzberg DS (1997). Predictors of the generation of episodic stress: A longitudinal study of late adolescent women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 10.1037/0021-843X.106.2.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, & Tofighi D (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12(2), 121–138. 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espejo EP, Hammen CL, Connolly NP, Brennan PA, Najman JM, & Bor W (2007). Stress Sensitization and Adolescent Depressive Severity as a Function of Childhood Adversity: A Link to Anxiety Disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35(2), 287–299. 10.1007/s10802-006-9090-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E, Wostear G, Cooper V, Harrington R, & Rutter M (2001a). The Maudsley long-term follow-up of child and adolescent depression: 1. Psychiatric outcomes in adulthood. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 179(3), 210–217. 10.1192/bjp.179.3.210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E, Wostear G, Cooper V, Harrington R, & Rutter M (2001b). The Maudsley long-term follow-up of child and adolescent depression: 2. Suicidality, criminality and social dysfunction in adulthood. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 179(3), 218–223. 10.1192/bjp.179.3.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frison E, & Eggermont S (2015). The impact of daily stress on adolescents’ depressed mood: The role of social support seeking through Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 44, 315–325. 10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galaif ER, Sussman S, Chou C-P, & Wills TA (2003). Longitudinal Relations Among Depression, Stress, and Coping in High Risk Youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32(4), 243–258. 10.1023/A:1023028809718 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, & Elder GH Jr. (2001). Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology, 37(3), 404–417. 10.1037/0012-1649.37.3.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, & Rubin DB (1992). Inference from Iterative Simulation Using Multiple Sequences. Statistical Science, 7(4), 457–472. 10.1214/ss/1177011136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George MJ, Russell MA, Piontak JR, & Odgers CL (2018). Concurrent and Subsequent Associations Between Daily Digital Technology Use and High-Risk Adolescents’ Mental Health Symptoms. Child Development, 89(1), 78–88. 10.1111/cdev.12819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Stuhlmacher AF, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, & Halpert JA (2003). Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 447–466. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, & Gipson PY (2004). Stressors and Child and Adolescent Psychopathology: Measurement Issues and Prospective Effects. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 33(2), 412–425. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C (1988). Self-cognitions, stressful events, and the prediction of depression in children of depressed mothers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 10.1007/BF00913805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C (1991). Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 555–561. 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C (2005). Stress and Depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 293–319. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Henry R, & Daley SE (2000). Depression and sensitization to stressors among young women as a function of childhood adversity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 782–787. 10.1037//0022-006X.68.5.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL (2008). Rumination and Depression in Adolescence: Investigating Symptom Specificity in a Multiwave Prospective Study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(4), 701–713. 10.1080/15374410802359627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, & Angell KE (1998). Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(1), 128–140. 10.1037/0021-843X.107.1.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harari GM, Müller SR, Stachl C, Wang R, Wang W, Bühner M, Rentfrow PJ, Campbell AT, & Gosling SD (2019). Sensing sociability: Individual differences in young adults’ conversation, calling, texting, and app use behaviors in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 10.1037/pspp0000245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Stahl M, & Petersen AC (1996). The protective role of coping and social resources for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 25(6), 733–753. 10.1007/BF01537451 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman MD, & Gelman A (2014). The No-U-Turn Sampler: Adaptively Setting Path Lengths in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Inyang I, Benke G, Morrissey J, McKenzie R, & Abramson M (2009). How well do adolescents recall use of mobile telephones? Results of a validation study. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9(1), 36. 10.1186/1471-2288-9-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NC, Bentley KH, Walton A, Wang SB, Fortgang RG, Millner AJ, Coombs G, Rodman AM, & Coppersmith DDL (2020). Ethical Dilemmas Posed by Mobile Health and Machine Learning within Research in Psychiatry. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenness JL, Peverill M, King KM, Hankin BL, & McLaughlin KA (2019). Dynamic associations between stressful life events and adolescent internalizing psychopathology in a multiwave longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(6), 596–609. 10.1037/abn0000450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Katz J, & Lew A (1999). Harbingers of Depressotypic Reassurance Seeking: Negative Life Events, Increased Anxiety, and Decreased Self-Esteem. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(5), 632–639. 10.1177/0146167299025005008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LM, Mitchell KJ, & Finkelhor D (2013). Online harassment in context: Trends from three Youth Internet Safety Surveys (2000, 2005, 2010). Psychology of Violence, 3(1), 53–69. 10.1037/a0030309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, & Ryan N (1997). Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial Reliability and Validity Data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(7), 980–988. 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, & Prescott CA (1999). Causal Relationship Between Stressful Life Events and the Onset of Major Depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(6), 837–841. 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, & Walters EE (2005). Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JBW (2001). The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R (2001). How U.S. Children and Adolescents Spend Time: What It Does (and Doesn’t) Tell Us About Their Development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(5), 160–164. 10.1111/1467-8721.00139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, & Ham M (1993). Stress and “storm and stress” in early adolescence: The relationship of negative events with dysphoric affect. Developmental Psychology, 29(1), 130–140. 10.1037/0012-1649.29.1.130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A, Ling R, Campbell S, & Purcell K (2010). Teens and Mobile Phones: Text Messaging Explodes as Teens Embrace It as the Centerpiece of Their Communication Strategies with Friends. Pew Internet & American Life Project. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED525059 [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Gotlib IH, & Seeley JR (1995). Adolescent Psychopathology: IV. Specificity of Psychosocial Risk Factors for Depression and Substance Abuse in Older Adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(9), 1221–1229. 10.1097/00004583-199509000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister-Landman KM, Domoff SE, & Dubow EF (2017). The role of compulsive texting in adolescents’ academic functioning. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 6(4), 311–325. 10.1037/ppm0000100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lüdecke D (2019). sjstats: Statistical Functions for Regression Models (0.17.6) [Computer software]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sjstats

- Madell DE, & Muncer SJ (2007). Control over Social Interactions: An Important Reason for Young People’s Use of the Internet and Mobile Phones for Communication? CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10(1), 137–140. 10.1089/cpb.2006.9980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, & Cole DA (2007). Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 23–44. 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazure CM (1998). Life Stressors as Risk Factors in Depression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5(3), 291–313. 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00151.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS (2003). Mood disorders and allostatic load. Biological Psychiatry, 54(3), 200–207. 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00177-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Kessler RC (2012). Childhood Adversities and First Onset of Psychiatric Disorders in a National Sample of US Adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(11), 1151–1160. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michl LC, McLaughlin KA, Shepherd K, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (2013). Rumination as a mechanism linking stressful life events to symptoms of depression and anxiety: Longitudinal evidence in early adolescents and adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(2), 339–352. 10.1037/a0031994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe M, Rohde P, Seeley JR, & Lewinsohn PM (1999). Life Events and Depression in Adolescence: Relationship Loss as a Prospective Risk Factor for First Onset of Major Depressive Disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(4), 606–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, & Reid MW (2008). Gene-Environment Interactions in Depression Research: Genetic Polymorphisms and Life-Stress Polyprocedures. Psychological Science, 19(10), 947–956. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02181.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murberg TA, & Bru E (2005). The role of coping styles as predictors of depressive symptoms among adolescents: A prospective study. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 46(4), 385–393. 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2005.00469.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdock KK (2013). Texting while stressed: Implications for students’ burnout, sleep, and well-being. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(4), 207–221. 10.1037/ppm0000012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nahum-Shani I, Smith SN, Spring BJ, Collins LM, Witkiewitz K, Tewari A, & Murphy SA (2018). Just-in-Time Adaptive Interventions (JITAIs) in Mobile Health: Key Components and Design Principles for Ongoing Health Behavior Support. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 52(6), 446–462. 10.1007/s12160-016-9830-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EE, Leibenluft E, McClure EB, & Pine DS (2005). The social re-orientation of adolescence: A neuroscience perspective on the process and its relation to psychopathology. Psychological Medicine, 35(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh HJ, Lauckner C, Boehmer J, Fewins-Bliss R, & Li K (2013). Facebooking for health: An examination into the solicitation and effects of health-related social support on social networking sites. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(5), 2072–2080. 10.1016/j.chb.2013.04.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orben A, & Przybylski AK (2019a). The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(2), 173–182. 10.1038/s41562-018-0506-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orben A, & Przybylski AK (2019b). Screens, Teens, and Psychological Well-Being: Evidence From Three Time-Use-Diary Studies. Psychological Science, 30(5), 682–696. 10.1177/0956797619830329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Walker LM, Coyne SM, & Fraser AM (2012). Getting a High-Speed Family Connection: Associations Between Family Media Use and Family Connection. Family Relations, 61(3), 426–440. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00710.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Keshavan M, & Giedd JN (2008). Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(12), 947–957. 10.1038/nrn2513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]